Interview of Harwood Graves

| Interviewee: | Harwood Graves |

| Interviewer: | Michelle A. Francis |

| Date of Interview: | May 17, 1983 |

| Location of Interview: | Robbins, N.C. |

Michelle A. Francis:

Testing, testing. Today is May 17, 1983. Now, you go ahead and say it again.

Harwood Graves:

Michelle, I was borned and raised in Randolph County and what started me into, gettin' my interest in pottery, my father's farm, there was large deposits of clay, and all of the potters that was in business at that time would come there and pick up their clay to haul back to their shops and turn into stoneware, whatever they were usin'. I'm sure I, the first account I ever saw of pottery-makin' was Old Man J.B. Cole when I was very young, he put on a display of pottery-makin' at the county fair in Asheboro.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you remember when this was?

Harwood Graves:

This was long about 1920, 1918 or '20, somewhere along in there. And at that time he was about the only potter that was left to run. All the rest of 'em had about closed down.

Michelle A. Francis:

How come?

Harwood Graves:

Well, from the fact that they just couldn't sell their ware because the plastics and stuff was comin' on in and it was more available for the, uh, the tin ware was more available and they just didn't have as much a demand for it. But, the potters that were left, a few of 'em, one that was within a half a mile of this place here, he was a moonshiner. And he made, he made his jugs and stone jugs primarily for puttin' his product in. And it was hauled then by the local people around to the different places where it was distributed. And, anything now, I started, uh, my brother Clyde and I, when we were just kids, we fixed up a place down there and made us a pottery wheel and started workin' the clay just for fun. And, as we grew older, uh, and got out of school, we went to work at the J.B. Cole Pottery and worked there until about 1935 or '6, somewhere along there. And then we set up a shop of our own. We made the stuff primarily for the stores and a line of planters and different types of flower pots and etcetera, etcetera. So, at that time, uh, that World War II came on, and I had to get into some kind of work for the government, and so I went in the machine shops and worked there durin' the war.

(Tape stops, then starts)

Harwood Graves:

After World War II I came back and we started our pottery operation again. At that time there was uh, the Gilmore Plant and Bulb Company that was situated in, uh, Julian. Was importin' bulbs from Holland and they needed planters to put these bulbs in. So they came over to me and wanted me to make wooden planters out of little trees with the bark on 'em. Well, the trees was so hard to find, so I worked out a way to make the planters that had the simulated bark and everything, out of clay. And, consequently, we for about two or three or four years there, we made these planters by the millions. Well, probably not millions but, a lot of 'em and we shipped 'em from Seagrove. We supplied . Kress, Eagle's, and Woolworth's for, for, uh, planters primarily for plantin' the bulbs in.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were they, did you turn 'em?

Harwood Graves:

No, we did this on a press.

Michelle A. Francis:

On a press?

Harwood Graves:

I made the molds that would, uh, put in a press and we could take, we could make probably a thousand a day.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my!

Harwood Graves:

And we'd stack 'em in the kiln just like stove wood or cord wood and fire 'em that way.

Michelle A. Francis:

What color glazes did you use on 'em?

Harwood Graves:

Well, we didn't glaze these. We have glazed 'em, but we didn't glaze these. We fired 'em very severely and would dip 'em in a colored wax which made 'em, oh, perfectly waterproof. They could set the planters anywhere and they, they . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

A wax?

Harwood Graves:

Melted wax. We'd dip 'em in the melted wax. And we could color the wax different colors.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. You did that after they'd been fired?

Harwood Graves:

That's right. After they'd been fired. So, then we, we made these on and the Gilmores set up a pottery of their own down 705 close to where the potters are. Fact, the business that, was at Joe Owens' place. Joe was still makin' pottery at the same place, but the company didn't last long. They went. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was this company? This was the Gilmore. . .?

Harwood Graves:

The Glenn Art, Glenn Art Pottery. And they were tryin' to produce it in a big production, and it just, they didn't do, they just didn't do too well with it. Fact of the matter is they lost a pretty good investment, I imagine.

Michelle A. Francis:

What was your connection with them?

Harwood Graves:

My connection with the Glenn Art Pottery was after I'd quit sellin' them the uh, the planters, I furnished them uh, the first planters that they burned, fired in their kilns. And at the Glenn Art Pottery I didn't have any connection with them other than uh, maybe work on their machines or do somethin' like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay, so you just sort of provided them with the mold?

Harwood Graves:

That's right.

Michelle A. Francis:

To get them in business?

Harwood Graves:

That's right.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay. Were they doin' other things besides that planter? .

Harwood Graves:

They were makin' other things like churns and vases and different things. And they even made hand-made brick.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was turnin' for 'em?

Harwood Graves:

Joe Owens and uh, there was two or three at that time. I don't remember the others. Joe and probably his brother Charlie. And the old kilns are still down there to be seen.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is this about 18--I mean 1940? '49?

Harwood Graves:

That was about, this along about 1946, '7, and '8. After, it was after the war.

Michelle A. Francis:

After the war. Right after the war.

Harwood Graves:

Then the company, McSwains bought the place and they still own the property. They're from down about Southern Pines. And they haven't developed the thing any further. The property is just a'sittin' there idle.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is Joe running it then?

Harwood Graves:

Joe is makin', back at his little shop where he was, he didn't, he's not usin' the facilities of the big shop.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay.

Harwood Graves:

Fact of the business, most of it was fallen down. But then after, after that, Mrs. Graves got, she was postmaster at Seagrove, and I couldn't get anybody to help uh, make pottery much over here, so I went with General Electric. And I stayed with General Electric until I retired about eight or ten years ago. I was intended goin' back in the pottery-makin', but I never did, never did get to it. But, the start with the whole thing, my brother and I worked at the Cole's, J.B. Cole's Pottery. He, about the time that Jugtown, that the Busbees came over it, and organized Jugtown, Mr. Cole, as I said before, was still 'bout the only potter that was left in business at this time.

Michelle A. Francis:

What was he turning? Or what was he turning out?

Harwood Graves:

He was turnin' out lead glazes. He was makin' ornamental jugs at that time. And usin' lead, lead oxides for the glaze, and there was more or less a rebirth in the art ware. This, the stoneware, the original pottery, had gone out. There was no one makin' that [unintelligible]. So, the art ware started boomin'. Well, Mr. Cole then got hooked up with a company in New York that was a'manufacturin' lamps and so they used his, he made the designs. They, they, would design what they wanted made in the way of lamp bases, bring it down, and Mr. Cole would supply that. He had about four, four or five people a'turnin' for him at that time. And they was turnin' out some huge quantities of pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

This is, what, around the 1930s?

Harwood Graves:

Uh, it was 1932, somewhere, '3, along in there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was turnin' for him?

Harwood Graves:

Well, my brother Philmore and his son, Waymon that's still there, his son-in-law Bascome King, and Jack Kiser, uh, he was one of the turners. And then there was a fella that uh, was from over in the Tennessee pottery country came over and turned the big huge vases. And, that business a'flourished for about five or six, four or five years. And somethin' happened that either they didn't uh, they didn't have the designs that were sellin' or somethin', and had produced a lot more of that than they were sellin'. So the company in New York eventually went out of business. But in the meantime, it had boosted Mr. Cole's capacity to where he could turn out, and at that time he was gettin' a demand for his demand--pottery was increasin' in demand. So, consequently, that, J.B. Cole's Pottery was about the largest around here and still, still is, far as I know.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were you doing for Mr. Cole?

Harwood Graves:

Well, Mr. Cole had me down there more or less as, uh, I wouldn't say a handyman, but whatever took place, and any time there was anything that came up that was odd in shape that they wanted makin', there's always somebody there comin' in that would have an idea to make somethin' that was different, that you couldn't throw on a wheel or somethin' like that. So, I would make the molds and do the work for that.

Michelle A. Francis:

So he was doin' some pressed?

Harwood Graves:

Oh yes. No, not pressed. Now he got an order for eight huge jars that was a'goin' down to a customer in Miami, Florida. They were four feet high and about two and a half, three feet across. And so I made those for him. We had to do that with the old rope and form trick like they, they've done for hundreds of years, you know. By plasterin' it on and keep turnin' it and finishin' like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Explain that to me a little bit.

Harwood Graves:

Well, what you do, you. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

What do you start out with?

Harwood Graves:

. . .you got to have, you make a frame, just the size of the inside of that and you, that frame has to be collapsible so that you can take it apart.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

Well then, you set it up on a wheel that you can turn by hand as you build the, build the pottery. And what you do then is you wind the rope entirely around this frame up there,. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

A rope of clay?

Harwood Graves:

Nope.

Michelle A. Francis:

No?

Harwood Graves:

A rope, just a rope.

Michelle A. Francis:

A rope rope.

Harwood Graves:

Wind it around there until the top and then you plaster your clay onto the rope, because the rope and the frame would support the clay as you build it on up more or less like a, like a mason does his work.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

So what we did, we built these on up and we could turn it and we can smooth it up so it looked just like it was

turned by hand or thrown on a wheel. And then we'd let that set. Whenever we got that done, I had the key that I could take one of the pieces of frame out, take it up through the top of the jar, and then it was just supported by the rope. Let it set about another day till it dried a little more, then unwind your rope and you had your vase there just like it was.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's pretty ingenious.

Harwood Graves:

Well, that's about the only way you can do it. But that's about all, let's see, that I've, uh. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he have trouble firing a big piece like that?

Harwood Graves:

Yes, he did. But we, we made this out of a type of clay, we would mix a mixture of uh, sawdust and beat-up clay that would keep it from crackin'. It couldn't shrink. And the biggest part of it was gettin' it through the door into the kiln. TNT: Was he usin' a groundhog kiln at that time?

Harwood Graves:

No. No, at this time it was walk-in kiln, more or less like what we got now.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

But the, the, when he left the groundhog kiln, the man from over in Tennessee, I's tellin' you about a fella, Douderick, he's the one that came over and showed him how to build a big out, walk-in kiln.

Michelle A. Francis:

What was his name again?

Harwood Graves:

Doudery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Daughtery?

Harwood Graves:

Dardy.

Michelle A. Francis:

Dardy?

Harwood Graves:

Dardy, Dardy, that's what it was.

Michelle A. Francis:

Dardy. That's interesting. Did he glaze these big pieces that you did?

Harwood Graves:

Mm-hum. Yeah. They had to be fired.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you do the work? I mean, I know you figured out how to make 'em, but did you put the clay and everything on it?

Harwood Graves:

Yes, I did. I had to do all that. Far as I know,

that's uh, those old frames are still down there, I don't know. I'm not sure.

Michelle A. Francis:

What else, kind of projects did you work on while you were there?

Harwood Graves:

Oh, I don't know. Along about that time, uh, the gold minin' started in over at Black Ankle, and Mr. Cole and my brother got the gold fever and so, I had to work with that some.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they go gold minin'?

Harwood Graves:

Shut it off now. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

You gonna introduce your brother?

Harwood Graves:

I'll introduce him.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay.

Harwood Graves:

Michelle, this is my brother, Clyde. He worked with us in the pottery when we were growin' up and he, uh, can tell you more about pottery-makin' than I probably can. Because he was through it all from diggin' up the clay in the woods and Clyde you can tell her about the time that you go over and take a, I don't know whether we should tell that about takin' a case of beer, you know.

Clyde Graves:

No. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, tell me. Tell me, please tell me.

Harwood Graves:

That time Clyde took a case of beer and a case of.

Clyde Graves:

I wouldn't think of tellin'.

Harwood Graves:

Oh, go ahead and tell.

Clyde Graves:

We used to go to the clay, what we call "clay ponds", deposits of clay, and sometimes we'd have to remove five or six feet of overburden and get maybe six inches of clay that would be suitable for makin' pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is "overburden" just. . .?

Clyde Graves:

It's all the top of it.

Michelle A. Francis:

All the top part?

Clyde Graves:

The topsoil and the other clays that wasn't suitable for makin' pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Clyde Graves:

And sometimes only get six or eight inches of the clay.

Michelle A. Francis:

For all that work.

Clyde Graves:

And, ever who had been there before, he'd dig under it you know, and then somebody later, sooner or later would have to go remove all the overburden. And it seemed like it's always our time to do that when we wanted to get it. (Laughter) And it took a little case of beer once in a while to do that.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter)

Harwood Graves:

Beer'd just come back in and,. . .

Clyde Graves:

Three-point-two.

Harwood Graves:

Yeah. That's all it took. Beer then didn't cost but about, oh ten cent a can or bottle.

Michelle A. Francis:

When was this?

Clyde Graves:

Or 15. Back in the '30s.

Harwood Graves:

It was always fun, though Clyde, to go off after a load of clay because they didn't expect you back until night. Now if you got too smart, you might have to go get another load. But, you know, whenever we went out, you's on your own. And a lot of times you might get stuck up and have to walk back. I've done that, too. But there's a lot of hard work in that. It's not done that way anymore. Go ahead Clyde if you think of anything else. Tell about Rance Steed.

Clyde Graves:

Well, there's one black man that was a potter that, uh, I don't know has received enough publication for a man of his caliber. His name is Rance Steed.

Michelle A. Francis:

Rant?

Clyde Graves:

Rance.

Harwood Graves:

Rance.

Clyde Graves:

R-A-, Ransom I guess, Rance Steed.

Michelle A. Francis:

Rance.

Clyde Graves:

And he turned pottery for a lot of the potters. And, who all was it that, Harwood that he turned for?

Harwood Graves:

Journeyman. Well, he had turned for the Chriscos, well 'bout all of the potteries.

Clyde Graves:

The Owenses, too.

Harwood Graves:

Yeah. And he could turn, he could pull up a stone jug that would hold five gallons and that, that, if his clay was good, it wouldn't be a quarter of an inch thick. And you've got to be an accomplished potter to take and turn that kind of a decent pot. You can look at somebody turning a piece of pottery and you can tell how, how good they are by how thick they leave the piece. Now a amateur can get up most anything, but it'll be thick. But whenever it comes down to the delicate like Nell turns, that just less than a quarter of an inch thick. Or Virginia down there at the pottery now. You don't find those, too many.

Clyde Graves:

Did Rance make those 5-gallon syrup jugs that we've got?

Harwood Graves:

Right, right.

Clyde Graves:

He turned those. We have some in the family that, uh, my father furnished the clay to Ruff Cole, wasn't it, Harwood?

Harwood Graves:

Yeah, Ruff, he, Rance was turning for Ruff in then.

Clyde Graves:

For Ruffin Cole and he made us a whole bunch of syrup jugs to hold the sauger molasses in, or the syrup. And they were mostly 5-gallon, and I know he put two handles on 'em--one opposite the other one. I guess the one knocked off, you 'd still have one handle. But a lot of 'em had two handles. And those provided the containers for us for our whole lifetime. We still have some of 'em.

Michelle A. Francis:

Still have some in the family. Well then, he was turning when?

Harwood Graves:

Oh, that was what, about 1915, '17, '18, along in there. '20s, '21.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay. And what age man was he then?

Harwood Graves:

Oh, I imagine he was around, in his forties, fifties at that time. He also, you know, was a moonshiner, too there you know. He was, uh, about all the potters were, had the connections with the moonshiners. I's telling her about, uh, that's what got us interested in pottery, was the coming there to get the clay. We got that and stayed with it. You remember we made the little clay grinder out of an old sausage mill. And set us up a little shop down there.

Clyde Graves:

Had us a kick wheel and turning pottery.

Harwood Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

You were just little boys then, right? Kids?

Harwood Graves:

Yeah.

Clyde Graves:

Had an old crankshaft made out of a buggy axle, you remember?

Harwood Graves:

Where did we get the things, from somewhere?

Clyde Graves:

I found it somewhere. But, now where was Rance buried, Harwood? Do you have any idea where he would be?

Harwood Graves:

I don't know. I know where his, uh, grandson lives over here behind the ridge.

Clyde Graves:

Somebody ought to look up and give that old black man more credit than he's been given.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who did you he learn from?

Clyde Graves:

I don't know. Probably worked for some pottery.

Harwood Graves:

That was the profession back then. But, and Nell's father you know, before he started makin' pottery to sell, for himself, he was a journeyman potter. He was turnin' for different people. Most of the people that had potteries, they weren't, they weren't the people who make the to pottery to sell. They'd hire somebody to come there and do it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, did Rance Steed ever have his own pottery?

Harwood Graves:

Not that I know of.

Clyde Graves:

Well, he worked some for, uh, John Yow, too, uh, you know, Canary's step-mother's husband. And there's a piece of pottery up there at the Seagrove Museum that's donated that he made. But I don't whether he got credit for it or not. But, J.M. Yow.

Harwood Graves:

Well, he probably wasn't, only the pottery owner at that.

Clyde Graves:

No, no. He was just workin' for the, I mean black man was workin' for Yow.

Harwood Graves:

I know. I know.

Clyde Graves:

He'd just go wherever who wanted him to make them pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

So Yow was another one of the potters?

Clyde Graves:

Yeah, of a short duration.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

There was potteries at, just about all over the country. Over here at Erect, now the Teagues had potteries, the Suggs had potteries, and you can still find pieces of that throughout.

Clyde Graves:

The Cravens, the Macons, all of 'em.

Harwood Graves:

Yeah. And the. . .

Clyde Graves:

I ran across a piece of J.B. Craven's brother. What was that name, Harwood? You know, I gave it to Bascome.

Harwood Graves:

I don't know.

Clyde Graves:

. His initials are R.S.C.

Harwood Graves:

That name's Dorris, Dorris Craven.

Clyde Graves:

Well, it was his, it was his brother or his uncle, wanted the other and I gave it for a loan of piece of Bascom Craven's. I found it in Virginia.

Michelle A. Francis:

In Virginia?

Clyde Graves:

Mm-hum. So they got around with that pottery. Hell, they'd take off and be gone for a month or two.

Michelle A. Francis:

Sold it in wagons, didn't they?

Clyde Graves:

Yeah. Take a wagon load off and trade it for anything (Laughter) imaginable.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were you tellin' me yesterday about they'd go into a town?

Harwood Graves:

Oh yeah. A lot of times they'd, mostly they worked out down South. I don't know why, but there's no clay down there and I imagine there's a, was a bigger demand for it and they'd go, they'd go in a town and open up the wagons. And they'd start sellin' pottery; tradin' it like Clyde said for one thing and another. And then, once in a while they'd hit a town that had an ordinance that was against, uh, sellin' stuff on the street without a license. So what they'd do, they'd come out there and you could get 'em or run 'em off or sometimes they'd slip out of a night. And I remember hearin' Lyndow Yow, tell about Lyndow Yow. They's a'goin' to come back to get the money and he had 'em to pile the fodder and stuff on him and had the colored driver, you know, to high-tail it out of town as soon as they turned back. So, when he got out of town, he was safe. But, uh, I don't know but still I expect that's all the truth that there is to that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Tell me a little bit more about, you said you went to the fair and saw. . .

Harwood Graves:

Oh, you remember the fair, Clyde, at Asheboro whenever Old .Man Craven. . .?

Clyde Graves:

Oh yeah. Old man Jason and Waymon was turnin', yeah.

Harwood Graves:

That was the first pottery turnin' I'd ever seen. And he was a relatively young man, had to been then.

Michelle A. Francis:

You said this was like 19--?

Harwood Graves:

I'd say about 1921-2, somewhere along in there.

Clyde Graves:

The fairground was up, where the. . .

Harwood Graves:

Where those old mobile homes are now, somewhere in that area up there.

Clyde Graves:

It was about where the uh, Guilford Dairy thing is.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were they just doin' it for a demonstration?

Clyde Graves:

Yeah. Old man Jason and Waymon had the wheel a'turnin'.

Harwood Graves:

Well, I told her at that time he was about the only one left that was even makin' pottery.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah.

Harwood Graves:

And I don't know what, I don't know where he got the idea for the glaze. Anyway, he learned that before, before Busbee came around, you know.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah.

Harwood Graves:

What started it, though, they uh, they were usin' the lead glaze to put the glaze on the inside of the pie dishes and they found out that by mixin' the green--well it was a green oxide of some kind--mix that with the, with the red lead, and you'd get a red. The red lead by itself would only make about an orange color. And whenever they added the green oxide to that lead, why, it came up with a red.

Michelle A. Francis:

It gave 'em that bright red?

Harwood Graves:

With a red. Looked like some of the red that's on that, although that's not a lead oxide.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

But at about the time that Busbee came over here Mr. Cole was a'makin' lead glaze pottery. He hadn't done much,

there wasn't much sale for it, but Mr. Busbee and his wife came over and started the Jug town Pottery, and they, they was the one that sparked the, the rebirth of art ware in this country.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was there a pottery already there in the Jugtown, where Jugtown is?

Clyde Graves:

No.

Harwood Graves:

Not where the Jugtown Pottery is. They was right there at it all around it, so they. . .

Clyde Graves:

Right in the middle of the Owenses and the uh, Teagues and the Coles down there. We seen the, you know, the pottery go down to nothin' you know, when glaze or aluminum ware came around, there was no use for a heavy crock to put milk in.

Harwood Graves:

That's what I told her, why they faded out. They just couldn't uh, no demand for it. So when you have no demand, the only thing they could sell maybe would be some flower pots, milk crocks, you know, there was still a lot of people used the spring runs to put their milk in. But I remember Mr. Busbee comin' down to Mr. Cole's. He tried to organize what was the potters was a'workin' then. They started back a'doin' some glazin' with the leads and he came up there and the potters, you'll still find that, potters are pretty uh, cagey with their glazes. They, if they get a glaze or get somethin' that's a little unusual, they try to keep that from their competitors or from friends. Never have been a close, organized bunch, so far as a guild or anything like that. So, Mr. Busbee, he got a kind of cold shoulder from all the potters that was in existence at the time. Because he was an outsider, but, they eventually owed Busbee a tremendous debt because he fired the whole thing up and got the interest up scattered all over the country. First thing you know, they're sellin' pottery just like watermelons. I remember, you know, up there at the gap, Clyde, we had a stand out there and no trouble.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah.

Harwood Graves:

And durin' the Depression, by golly, to sell uh, maybe $200 worth of pottery in a weekend.

Clyde Graves:

All up and down the Chimney Rock Valley and all through places of tourists, even in the midst of Depression, pottery sold.

Harwood Graves:

And what took the place of the wagons a'goin' out, they, these places like uh, Bat Cave, Chimney Rock, and any place where tourists was a'goin' to, they set up shops and there where the customers. And Mr. Cole would, uh, we'd haul pottery from Maine to Miami and it was a tremendous business at that time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you put it, have your own trucks that went out?

Harwood Graves:

Yeah. He had his own trucks.

Clyde Graves:

I went on a truck to New York City back in the uh, late '20s. An open 2-ton truck, Bill Graves and myself, we went and delivered the pottery, a load of pottery packed in straw, right in the, Manhattan, New York. What was the address?

Harwood Graves:

I don't know if I. . .

Clyde Graves:

Uneka Pottery.

Harwood Graves:

52nd, up on 52nd Street.

Clyde Graves:

The Empire State Building wasn't finished. We went down and went up as high as you go, 40 stories, is up in the Empire. State Building.

Michelle A. Francis:

That was somethin' wasn't it?

Clyde Graves:

Some trip, I'm tellin' you. We drove a truck up there and back.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you do it all in one day, or would you stay over?

Clyde Graves:

We started in the afternoon and drove all night and uh,. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

You never stopped?

Clyde Graves:

Never stopped. Picked up a hitch hiker in Philadelphia. He said he knowed all the main drags, he'd been to Miami for the bus down there. And picked him up and he drove the truck through the Holland Tunnel on into New York and helped us unload the pottery and he lived out in Long Island somewhere and Bill Graves, my cousin, let him take his truck home with him. We'd never seen the guy before.

Michelle A. Francis:

And you just let him have the truck?

Clyde Graves:

Let him take his truck home with him and he's gonna come back the next day and pick us up and take us back through the tunnel and get us started home. And of course we hadn't slept in two nights so we got us a hotel room. And I think it was three dollars and a half apiece we had to pay for the hotel room. And uh, we went to bed. And he was supposed to be there at nine o'clock the next mornin'. But we both overslept and at ten o'clock we got a call on the phone, he was downstairs. I was glad we overslept because we would a'thought he'd absconded with the truck (Laughter).

Michelle A. Francis:

You'd had the police out (Laughter) lookin' for him.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah, but that was one thing that turned out all right. He saw us through the tunnel and we gave him enough of a fare to get back into the city.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you deliver it to a. . . (Tape stops, then starts)

Clyde Graves:

. . .the truckload of pottery was packed in straw, a whole big batch of, you know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who were you delivering it to? Was it a department store?

Clyde Graves:

The Uneka Pottery, it's in New York.

Harwood Graves:

This was the company that I told you about that had uh, given Mr. Cole the [unintelligible] you know, of makin' lamps up there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay.

Clyde Graves:

What was his name, Harwood?

Harwood Graves:

They were all, I can't think of it, oh, Christy, Christy, was one of 'em.

Clyde Graves:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

But I want to tell you, just while I'm thinkin' about it, tell you about this time Dorothy's father and I went over to Asheville, Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee with a load of pottery. Mr. Cole was a great guy and he was one of the fellas that just didn't like to ask anybody for a debt. And he had a customer over there, I believe it was this side of Knoxville, Tennessee, that was the best customer he ever had. But sometimes he'd get behind two or three hundred dollars and, uh so, you never can tell when you're gonna lose that last account. So, we had a order of pottery and Mr. Cole says, "I don't know whether I'll ever get a cent out of him or not." But we went on over there and on the way, it was about 15 or 20 miles before we got there, I could see Mr. Cole worryin' about gonna have to ask him for that uh, account. And he said, "If you see a beer joint anywhwere, stop." And we stopped and got us a beer and by the time we got over there he was pretty well fortified and ready to ask the man that he had to pay up or we didn't unload pottery. The man came out of the shop and said, "Mr. Cole, I'm so happy to see you. I's just f ixin' to mail this check to ya." Handed it to him and Mr. Cole went and did all that worryin' for nothin'.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) I bet he was relieved.

Harwood Graves:

Michelle, I believe this pretty well covers what I know about it. It's a lot of fun back then, but Mr. Cole was a character, one in a million. He had a long corkscrew mustache.

Clyde Graves:

And about six feet tall.

Harwood Graves:

He was about six-feet-six tall.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, he was a big man.

Harwood Graves:

And I remember we took a load of pottery up to The Three Mountaineers in Asheville, you know. Everybody get into the pottery selling business.

Clyde Graves:

We took a load, several loads to Miami, Florida.

Harwood Graves:

Oh yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

That was a long trip.

Harwood Graves:

That was Rondale. Rondale down there.

Clyde Graves:

[unintelligible] Rondale. Biscayne Boulevard.

Harwood Graves:

I remember I forgot to tell this part you about our pottery makin'. We were the only white people that made uh, Indian arrows and tommyhawks and stuff like that and sold 'em to the Indians.

Michelle A. Francis:

You sold 'em to Indians?

Harwood Graves:

I had a press over there that would press out a tommyhawk just perfect, you know. And also we made the clay pipes with the Indian head motif on it. And, then the arrow heads and spear heads. So, we went over loaded up a load of all kind of pottery and went over to Cherokee. Well, the one thing about the shops in Cherokee, I guess it's about the same now, if you sold one, you'd sell every one of 'em. Because none of those shops want to be caught with something, uh, don't have something the others got.

Michelle A. Francis:

The others don't have. Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

So, we sold those tommyhawks and they'd put 'em on the big handles for 'em over there and tie some feathers on 'em. And we sold tommyhawks to the Indians.

Michelle A. Francis:

When was this?

Harwood Graves:

That was in about 19', uh, that was before World War I. II I mean. I don't remember. David was, David was a baby.

Clyde Graves:

It was in the uh,. . .

Harwood Graves:

Sharon was a baby, '30s I guess.

Clyde Graves:

No, it was later than that. It was before Alice went to work, I mean pottery, in the post office. I guess it was in the fifties.

Harwood Graves:

Oh, no. After the war.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah, yeah. It was after the war.

Michelle A. Francis:

So this is when you started up your pottery again?

Clyde Graves:

That's right. When we started up again.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Clyde Graves:

You know how he got this mold? Cuttin' down little walnut trees. Made it from that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is that what you made it from?

Harwood Graves:

Poured the bark, poured the mold against the, that's the exact impression.

Clyde Graves:

So, it's gonna be like a tree.

Harwood Graves:

Press it into the soft clay, you're [unintelligible].

Clyde Graves:

It was a hickory, or walnut tree wasn't it, Harwood?

Harwood Graves:

I think it was.

Clyde Graves:

Just think about if that'd been a big tree.

Michelle A. Francis:

I know. It looks sort of like a walnut tree that I got at home, the bark does. It has that kind of configuration on it.

Clyde Graves:

Well Michelle, there's potteries everywhere. Everybody's got 'em a pottery now.

Michelle A. Francis:

I know.

Harwood Graves:

There's more now than ever.

Clyde Graves:

And they're doin' a dang good job of it. Some of 'em are doin' a real good job.

Michelle A. Francis:

What did you do for Mr. Cole? Did you work for Mr. Cole some?

Clyde Graves:

Well I really worked for my brother, Phil and Nell made the, worked the clay up, you know. Made, called makin' balls. And weighed it out you know, worked it up, worked

the air out of it. You've seen 'em do it, and weigh it out.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh yeah.

Clyde Graves:

And that's what I did.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's what you did?

Clyde Graves:

And later I worked in the shipping department and things 1ike that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

Our brother Phil was the only one of us that was an accomplished potter, I mean, thrower. And he, they always had the sayin' that you had to be born, that you had to had that gift. And Phil was about the least gifted in those kinds of things as any of us, but he was the best accomplished potter that Old Man Jase's Pottery's had.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

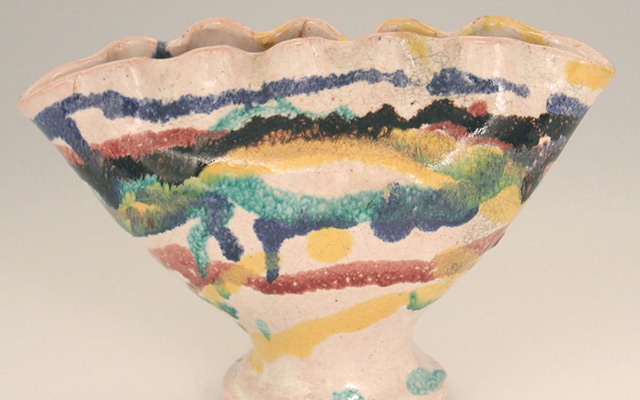

Now here's what they're makin' now. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

Tell me a little bit about the early stoneware pieces that you said you liked. They quit makin' stoneware, didn't they?

Clyde Graves:

Yeah. There was a period of 10 or 15 years I guess, probably more than that, that there was very little stoneware.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did they quit makin' it, do you remember? Or it may have been before you were born.

Clyde Graves:

Well you're talkin' demand. The demand ran out for it because they didn't want the heavy utensils made out of clay if you could do it with the glass or porcelain or something else. And I have no idea, it finally petered out, you know.

Harwood Graves:

It petered out in the '20s, late '20s.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well then, the art pottery is made out of, um, earthenware.

Harwood Graves:

'Bout the same kind of clay.

Clyde Graves:

It didn't take as good a clay, uh, the type of clay, it wasn't as good a clay.

Harwood Graves:

No, they didn't fire, and they didn't fire the art ware, only just enough to melt the, the lead glaze, which

didn't take much, 'bout 1800 degrees. And to vitrify like this here, you got to go up to about 22-300 22-2300.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Harwood Graves:

So, they could use, uh, fire a cooler clay than what they did with the stoneware.

Clyde Graves:

Instead of gettin' four inches you might get three feet, or somethin'.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh-huh. You could do more with it.

Clyde Graves:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

More flexible. Okay. I wanted to ask you, Mr. Harwood what your birth date was?

Harwood Graves:

Oh, 9/27, 19'9.

Michelle A. Francis:

And yours?

Clyde Graves:

September 17, 1912. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Thank you.

(End Tape)