[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

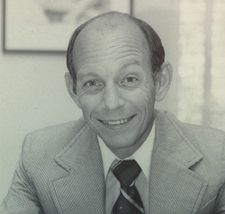

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (0:00)

Dr Monroe, I certainly appreciate you coming to see us today. It's delightful to be back in the campus. Thank you. Well, you know you're always welcome here. In fact, I I see you every day I come to school in the foyer of our school we have this may matrix of individuals who were here when the school started, and you're actually considered number two on that list. It seems that number one, at least, as portrayed on that portrait, is Chancellor Leah Jenkins and I really wanted to at least have an opportunity to find out at a personal level more about what happened at the beginning of our school.

Edwin W. Monroe (0:54)

I became aware of what was happening on campus at East Carolina, which was then East Carolina College, and of the leader, Leo Jenkins, because he made a couple of speeches about what East Carolina was going to try to do in the future in order to grow and be of more service to the state. And I was impressed with his Gall, so to speak, for announcing what he intended to try to get done, and also impressed with the amount of editorial opposition from Raleigh and points west to his aspirations for this for this area and for the school. And then I and all the doctors in Greenville became aware of the fact that the shortage of health manpower was getting critical year by year, and nobody seemed to be more aware of it than we, who were trying to deliver health care. And the upshot of that is that we tried to recruit more doctors here to practice. I got an associate, the leading surgeon in town got an associate, the pediatrician got an associate, but that was about it for us. There just was no trickle from the manpower base up in the Piedmont for doctors to trickle on down to eastern North Carolina, the ones who were here were dying off. So that led to my interest in trying to do something about it, and from there, it's a long, hard story.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (3:09)

Now, from what I understand, Chancellor Jenkins wasn't convinced early on that this was that a medical school and the ability to create doctors and programs in eastern North Carolina was, was the responsibility of the ECTC at that time, from what I hear, that was he had to be convinced that this was necessary. And I believe one earnest Ferguson from Plymouth was the one who actually convinced him that this was important.

Edwin W. Monroe (3:42)

One of the people that convinced him true and tall, heavy set, very busy family doctor, did a little bit of everything over in Plymouth. He went to a meeting at Duke on he was an alumnus from Duke, went to a meeting in the medical school and came back down east, but very impressed with the fact that Duke was more and more interested in international affairs in medicine and national affairs in medicine than what was happening in North Carolina. So he decided to go tell Leo that what East Carolina needed to do is do something about manpower. Yes, at that point, the nursing school was already established about 1960 and Leo was impressed enough with the good that had the potential to do that he agreed to push ahead and explain. Explore the idea of trying to do something about getting more doctors here from an academic approach.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (5:07)

Yes, now we're sitting on what is now called the Health Sciences Campus, and we came over from the Brody School of Medicine to be to the Locust library to have this conversation this morning, and right next door is the School of Allied Health, the School of Nursing and the College of Dental Medicine. Was all of this envisioned at that time.

Edwin W. Monroe (5:35)

It was envisioned in the sense of a figment of one's imagination. It was not envisioned as an accomplished dream to work toward, and one of those was what is now the School of Allied Health and Sciences, producing manpower in physical therapy, occupational therapy, vocational rehabilitation, counseling, medical technology, environmental health, those kinds of programs that were much needed for the graduates they produced, and those kinds of programs that could be started without the furor and funding fights that accompanied the idea of a medical school.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (6:31)

So two things. First of all, I understand you were the first vice chancellor for health sciences on our campus, and you were also the first dean of the School of Allied Health, yes.

Edwin W. Monroe (6:44)

I started as director of the community in Life Sciences Institute, which became then the School of Allied Health, yes, and Dean of that and I had a secretary, and that was it. And it grew, yes, year by year, legislative session by legislative session, and on the Qt, a good friend of mine who's now dead, was the Provost of the University, and he was working on strengthening the basic sciences on campus, chemistry, biology, physics, particularly, bringing in more faculty, recruiting people who were interested in things other than science, education for public schools. And he and I quietly put together a plan to start a medical school, cautiously, step by step, starting with a two year program in the basic medical sciences, which we didn't refer to as a medical school, because we knew what image that stimulated in all the opposition around the state, and we were able to get that through the legislature With the help of then Governor Bob Scott, who helped us get the initial funding to plan what he recognized would be a medical school, but we called it basic medical sciences.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (8:34)

So it is clear that it required a tremendous amount of political finesse to even create the agenda for developing the medical school

Edwin W. Monroe (8:44)

True, it also required the very ardent support of people across eastern North Carolina and indeed people in smaller communities around the state, not the big cities, and also required the total commitment of legislators from this region. So how was that support developed? How Yes, piece by piece, starting out with the first appropriation of $375,000 to plan and develop a two year curriculum in the basic medical sciences,

Edwin W. Monroe (9:39)

we were lucky. The governor supported it. He was chairman of the Board of Higher Education, and at that point, was also chairman of the UNC Board of Governor because of his position as governor and the legislature. I wasn't really as a body organized in opposition. The support was organized by the legislative representatives from around here, all of whom are dead. Now,

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (10:20)

Can you tell me you were clearly recruited, then from a private practice 12 years into the university environment? Yes, tell me about the transition and then your role

Edwin W. Monroe (10:34)

Well, my wife thought I was crazy at first,

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (10:37)

But don't, our wives always think we're crazy.

Edwin W. Monroe (10:42)

But first thing to do was to develop the Allied Health School, and we did have a modest operating budget to do that. Two years later, we got $1,300,000 to build a building for it, which is still on campus, but health sciences does not occupy it now, sitting there and planning a curriculum in programs like physical therapy and occupational therapy and related health fields other than nursing, they did their own thing, and it was lucky that Bob Williams, who was my friend on campus, was able to advise me and look over My shoulder as I put together the paper required to get those programs underway and then recruit the people to head them up. Yes, and vice chancellor, no, I wasn't, not until 1972 so since I started in 68

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (12:02)

It appears that at times this conversation across the state became really quite difficult and and Did you sense that your professional career was ever being challenged?

Edwin W. Monroe (12:17)

Professional career? No career in academic environment? Yes, definitely, but I wasn't worried too much about that, because I could always go back to being a practitioner.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (12:36)

Isn't that true even today, with us in the business, in the profession? So was, was Chancellor Jenkins any more threatened than you were, or both of you were, even in the crucible Much, much every day,

Edwin W. Monroe (12:50)

My impression was that he felt very threatened when the state reorganized higher education, and what we now know as the UNC system was put together, and the President of the three campus, part of that chapel, Hill, NC State, Raleigh, Unc, Greensboro, Bill Friday, let it be known when he took over the responsibility of expanding the system that if any of his chancellors were showing any interest in Raleigh and were a presence In the Legislative Building, then he would frown very heavily upon that

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (13:43)

That was a shot across the bow. And

Edwin W. Monroe (13:47)

Leo was getting close to retirement age, which was compulsory then at age 65 and he was concerned that he might be forced into retirement early. At the same time, he wanted to move ahead so he would still make speeches, but he would carefully avoid the appearance of being in Raleigh lobbying, and it fell upon me and Wally wools, whom I had recruited to head the two year program to move in and try to pick up on the lobbying part of it. So we made frequent trips to Raleigh during legislative sessions, and at one point I spent a week up there, sleeping in a motel and wishing Like hell I was at home.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (14:47)

Well, you know, there's still some controversy about when school actually started and I was in the middle of this fray of discussion more recently, when we had some of our alum. From the first class come to Greenville, and they're just as staunchly supportive of the school, even though they were in a two year program as all the other classes subsequent to that,

Edwin W. Monroe (15:09)

I know.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (15:12)

So when did our school actually start? In your opinion? Was it 7274 when did it actually start?

Edwin W. Monroe (15:19)

The first one year students enrolled in the fall of 72 and it operated as a one year program for three years. Then there was a hide as of no student for two years, and 77 the first class for four years, enrolled I see and graduated in 81 yes, the first two year, first three years of one year programs moved on to Chapel Hill in groups of 20, of It per year, and graduated four years later, three years later, without any problems whatsoever. In fact, several of them led the classes.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (16:08)

So it seems that they were really well prepared here in Greenville, North Carolina,

Edwin W. Monroe (16:14)

Intensively prepared in small, small group of 20. Yes, you know, it's almost one yes,

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (16:23)

You'd be proud to say that the same culture persists today. Our medical school class is 80 strong, and we're very proud that we got all the way from that number that started now that we have 80 students, but they still behave like a family and our faculty are intimately involved with every single medical student in part of their career preparation. I

Edwin W. Monroe (16:45)

Think that's great. Yes, I missed it when I was in school.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (16:50)

Well, you obviously came from a larger school.

Edwin W. Monroe (16:54)

Well, I graduated from a larger school, University of Pennsylvania, but I was there because I went to Chapel Hill the first two years when it was a two year school, yes, and I had to transfer somewhere. And back then, the Dean of that two year school told each student where he was allowed to transfer. And if you were not in the top third of the class, then you would go to places like Wake Forest, Duke, Virginia, Richmond. If you were in the top third of the class, you went places like Yale, Harvard, Cleveland, Western Reserve in Cleveland, Penn, those kind of places, yes, and it was. It was an astonishing adjustment to move from two year program at Chapel Hill with 50 students per year to a place like Penn for the last two years, with 150 students in your class, and you didn't know any of them because they'd been together for two years. Here we go.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (18:11)

Let me talk a little bit about the mission of our medical school. Folks from across the country come to Greenville, North Carolina, and are astonished that we've been able to maintain that mission for almost 40 years. And I paraphrase to a degree, but we were placed with a with an order from our legislative partners to create primary care doctors for eastern North Carolina. We are also to recruit and retain underrepresented minorities. And the third piece was to change the health outcomes, which were devastating in eastern North Carolina. If I was a sane man in those years, I would say, forget it. That's crazy. Nobody has ever created primary care doctors to live in a rural environment successfully, especially if they're not able to make a living. So how are you going to do that? Number two, underrepresented minorities at that time were really African Americans, who are all matriculating through a public school system. And Mr. Legislator, you want us to make them into doctors, you said, and the most devastating problems in medicine, we're the 51st state in eastern North Hannah, and you want our young medical school to change that outcome, y'all got to be crazy. There's no way we could do that.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (19:47)

So how were How was this received? Were folks that ambitious? Early on, How was that received in the state?

Edwin W. Monroe (19:59)

It was. Received by the general population and by the majority of the primary care doctors in the state as not only a mission, but an objective that had to be accomplished no matter what you had to move ahead religious organizations, civic clubs, they were all stimulated to get involved in the propaganda fight I'd call it, and there's no way you could avoid it if you were going to take the money you had to live up to Your promise. Yes, at least, that's the way we felt. And I had watched Duke get started. I had a brother that graduated from Duke Medical School. I had watched Chapel Hill become a four year school. Participated in the opening of the hospital up there as a first year resident in medicine. Stayed there three years, then came down here and I watched what happened to Chapel Hill over the next few years, they lost track of their mission state supported but they had to be hit over the head to start a Department of Family Medicine. The pediatricians they were producing, by and large, became sub specialty pediatricians. And Lord knows, the same thing happened in internal medicine. So I knew we could not forget what we were supposed to be about.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (21:47)

Well, 40 years later, perhaps more than 40 years later, as you remind me that it started in 72 we have not forgotten, and we're still number one in the nation for making primary care doctors, family doctors, percentage wise. And we have this remarkable statistic of keeping people in the state of North Carolina. So we benchmark with the very best in the in the nation, right here from Greenville, North Carolina, on the banks of the mighty Tar River. That's great. Can you tell me, then, in reflection, where you thought in your career was, was the highlight of your career? What was the highlight of your career, in in in this engagement?

Edwin W. Monroe (22:40)

Well, it's going to sound peculiar, but I guess the one moment that stands out is Bill Friday was coming down during his last years at the helm of the university system to give a talk at the 50th anniversary of Pitt County Memorial Hospital, right across the way over there, now violent Medical Center, whatever violent means, and I had the privilege or the penalty of driving him from a meeting on campus out here to the hospital to give his speech after lunch that day on the way out here, he said, Ed, you know You should be proud of all this. I was wrong, and I'm glad to admit it, I thought this development as best I could. And I really think that I was wrong, and that, to me, represented a turning point that I thought was remarkable. So it seems that

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (24:08)

President Bill Friday clearly was man enough to recognize that he had made a mistake in not being as supportive of the development of the medical school in eastern Northland as he should have, and he was able to say that to you, one of the early proponents for our school.

Edwin W. Monroe (24:27)

He did say it to me. And after lunch, when he made his speech, he made reference to the fact that he admits now that he should have been more supportive.

Paul [Last Name Not Provided] (24:39)

Excellent. Again. I wanted to thank you for coming to see us today. And for me, this is a blessing to be able to have a conversation with you today.

Edwin W. Monroe (24:49)

Thank you, Paul. Thank you very much. You're doing a great job. Keep it up. You're kind.

[End Of Video]