[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION

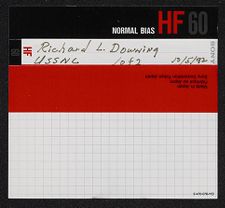

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW # 24.048

USS NORTH CAROLINA Battleship Collection

Richard L. Downing

World War II

October 5, 1992

Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon

[If you will, in the way of background, tell us a bit about where you came from originally, your early experiences and what led you to the Naval Academy.]

Well, I am from St. Paul, Minnesota. My brother preceded me in the class of 1935 in the Naval Academy. I had a cousin in the class of 1924, by the name of William Mitchele (?). Just the heritage, I guess, induced me to continue. They had successful careers. We knew a congressman well, which helped back in those days for getting appointments. I got the appointment to the Naval Academy and entered. That is the basic background of how I happened to go to the Academy.

[So you came directly out of high school to the Academy, without going through the prep school route.]

I went to a prep school in Minneapolis, run by a gentleman by the name of Kraffy. I went there for three months. I then, of course, took the examinations in the winter time of 1934. I entered in 1935 and graduated in 1939.

[What about your experiences at the Naval Academy? Was it pretty much what you expected? Tell us something about that.]

I would say it is pretty much what I expected. My brother had given me a good background of that. Plebe year was not so happy entrance into the Academy.

[Why? In what way?]

Just having to answer to all the commands and presets. Whatever was demanded of one from the upper classmen. Then you became almost a slave to a particular first classman who was assigned to you. Little things like having to walk square corners and the yes sir and no sir. Just getting into the military part of it, I guess.

[If you had a first classman that you were responsible to, sometimes they could protect you from some of the harassment.]

I had a good one, I can't deny that. It is just getting over the civilian attitude of being able to be your own boss into having to be subservient, you might say, to anybody else in the way of an upper classman. Sometimes the youngsters, the second year men, were the most difficult people on the plebes. They had just emerged from that serfdom, you might say, and were more inclined to harass you. As you say, the first classman, if you had a good one, he would tend to protect you.

[The second year men wanted some revenge for what they went through.]

Then you got into graduating from plebe year and you go on a summer cruise and that is quite an experience. Three ports that we put into--England, France and Sweden. Learning to live again, you might say. Although you are still a pretty junior guy because you haven't quite graduated. We wore a seaman outfit of course, and scrubbing decks and getting into the basic way of the Navy. Youngster year is always said to be the most difficult scholastically. You grind through that pretty much. It is a grind, it was a grind then and I am sure it is now. Then you get to live a little better, it is called second class summer when you stay at the Academy and you learn various Naval and ordinance duties there. You go on a second class cruise, which was limited in those days, to the immediate area. You go aboard a destroyer, a destroyer escort or whatever in the immediate area of the States. In the second class year, the third year at the Academy, got to be rather pleasant actually. The worst of the academics, you have gotten into the routine. You can kind of cope with it and all. Of course came the first class year cruise when you graduated from the third year. You became a first classman. That was really a pretty good life, actually. A lot more freedom and you knew the routine pretty well. You are reasonable intelligent, the academics weren't too difficult. A delightful cruise. The cruise between second class year and first class year in the summer time, and again we visited ports. This time we were in France, England and Germany. They were delightful. On first class year, which was a very pleasant period actually, you have become adjusted entirely to the military by that time and graduation and that was it.

[What did you think of the academic methods they used for teaching?]

I think, if I could have a criticism of it, I would say it was too much of a memory. Not enough of using your thinking. For instance, you would be given certain pages to read, then you would be given daily tests on those pages. It is largely how capable you were of remembering. This was in electrical and steam engineering, mathematics and such. How capable you were of memorizing and being able to repeat or recite what you had learned. The only thinking course was an English course, that had you writing things.

[Probably taught by civilian rather than by and officer, wasn't it?]

Half and half I would say. Of course, seamanship, ordinance and gunnery, would be by officers. English, of course, would be civilian.

[That is what I mean.]

Oh, I am sorry, that is true. I had a couple of gentlemen from the University of Virginia, professors, graduates and they were very good. Yes. That was my favorite course, as a matter of fact. You had public speaking and other things that were more attuned to using your mind, you might say. By and large, it was a good course for preparation for what you had to do. Seamanship, ordinance, and especially engineering, which became my specialty later on in the service.

[Can you recall any particular incidence either regarding the academics or your social life, or the harassment as a plebe that come to mind?]

Well, of course, I recall harassment of cutting square corners, walking down the middle of the passageways or the corridors. Passageways, as I recall, having to go up the center of the step and cutting square corners. The constant sitting on the edge of your seat at the mess hall. If you did something improper, having to push out the chair and sit on infinity, as it was called. Constant asking of questions by first classmen. If they were difficult at all, and you couldn't answer it, you were told to push your chair out Mr. Downing. Kind of a harassment continuing in that direction. On occasion, especially as you got towards the end of plebe year, towards June week that first year, there was the potential of having your rear end beaten and such. More dramatic types of harassment or physical types of harassment.

[Did you do much sailing on the Chesapeake for relaxation?]

Yes. We could do that. We had star boats and half raters as they were called. You were able to use those any afternoon of your choice, although the better boats were for the upper classmen. Yes, that was some relief from it. There was the glorious Saturday afternoon, when you could go out into the town of Annapolis and go to the Circle Theater, the one movie theater in town so you would be escaped from the academy for about four or five hours of a Saturday afternoon. Youngster year it became Saturday and Sunday. Second class year, Saturday, Sunday, and Wednesday afternoons. First class year, every afternoon you could go out if you wanted to. That is kind of the graduation of it. Harassment of the mind, as much as anything, to belittle you. To make you a plebe. To make notre to the great phrase in the Navy was, "In order to give orders, you must be able to take odors." That was their reason for doing all this.

[Do you remember a class mate of yours by the name of H.A. I Sugg, known as "Si" Sugg? Howard A.I. Sugg.]

Vaguely, yes. He wasn't in my battalion. There were four battalions, I was in the second battalion. If it happened to be the same battalion, you knew these guys pretty well. Other battalions, you weren't in their same classes and such and you had to have some cross reference of athletics that would have you knowing them. I remember the name.

[After he retired, joined the faculty at EC, and is now retired. He is a good friend of mine. Strong supporter of the Manuscript Collection.]

What service was he in after he went, destroyer?

I think it was destroyer primarily, if I remember correctly. I do think he was fourth "bat" as we say, I was second battalion. I think he was a second battalion. I really didn't know him too well.

[He wound up with some eye problems which, I think, washed him out before he graduated. Of course, when the war came they were happy to have him back.]

My roommate was that way too. He was from Tennessee. He graduated and got a bad back, but during the war he was back in. They were happy to have him.

[That is what happened to Si. What about athletics or anything of this nature?]

I did intramural athletics. I was an all-star touch football man. Nothing in the way of team athletics or that for the academy.

[When you graduated in the Spring of 1939, what assignment did you get?]

The USS BROOKLYN, which was a relatively late year light cruiser. I went into engineering and was in the propulsion department. Because of my engineering background and I made my best marks in Engineering, I guess, so I was assigned that duty on the BROOKLYN.

[Where was it stationed?]

In Long Beach. We made, I think in the time, I was only on her for a short time, for three months. We made a cruise to San Francisco and back to Long Beach. Then the call came for officers to man the four stack destroyers, which were just getting active then. They needed that type of ship. War was moving on the horizons, shall we say. This was in October of 1939, so I was transferred to a four stack destroyer. The USS SANDS-255, DD-225. There was really quite an experience, because there was just four officers of us. These were six that had been decommissioned in 1918 or 1919 and all their stores and the items aboard the ship that were useable, were put into one locker. I was the first one assigned to the SANDS had to go back and dig all of that stuff out and set it up and such. It was quite an experience to see the old navy, you might say.

[They had been moth balled for fifteen years?]

Oh, yes. From 1921 to 1939. Almost 20 years.

[What kind of physical condition were they in?]

Not too good. They had been in lots of red lead. Lots of anti-corrosive paint applied to them. Each one had a history of it. The one I had, the executive officer is a suicide case and they still have the bullet hole in the head of head door. It was little experiences in each case, which you go back into the log and see these things that were recited. On board the SANDS, we called her the "Traveling SANDS" because we got commissioned in Long Beach and then traveled down into the canal and were kind of showing the flag in essence in the Caribbean for a year or so. At that time, the Germans had merchant men that they disguised as merchant men, but were actually fighting craft. They would attack at that time, ships of the British and the French. We were assigned to search these. That was our mission at that time. On the SANDS, we went up the coast, visiting various ports, Norfolk, Boston, and out into the North Atlantic. Anyway, I was on that was on that ship for about 12 months, until I was assigned to the NORTH CAROLINA.

[With the SANDS, did they refurbish her before you took command? They replaced obsolete equipment with new equipment and repainted.]

As best they could, yes. Being one of the earlier people, if our locker didn't have it, we would somehow go to somebody else's locker in the ships that were commissioned later and make sure that we had what we wanted.

[They didn't outfit her with new guns or more modern guns or I suppose in 1939, they were using pretty much the same guns that had been used.]

Five-inch guns. Same guns. We had target practice, but we never had any severe encounters, as I say, we are mostly showing the flag in the Caribbean, then chasing German merchantmen, disguised merchantmen whom we never caught up with actually.

[That would have made an interesting experience if you had come across one of them.]

Yes. I can't remember whether any of our division, whether our fellow destroyer people did or not. I don't remember that part. I know that was our mission.

[Was the SAND pretty sea worthy?]

Oh, yes. We had no problems there. There was some rough seas in the North Atlantic, obviously as part of our duty. It was kind of interesting pre-war. We would go into port and in Bar Harbor, Maine or where ever we would happen to put up, we would be entertained by the so called society folks and such. The pre-war Navy, you have got to realize, was a very delightful area to live in, socially speaking, because you were put in, entertained by the political figures and such. Being potential defenders and such. It was good service.

[Come fall of 1940, you were.]

I was transferred in January or February of 1941 onto the NORTH CAROLINA and went to Brooklyn where we were put up at the St. George Hotel, which was delightful. Gathering cruel must have been in the Navy Shipyard in New York.

[The crew members were aboard the SEATTLE, sleeping and eating.]

They did the officers up right. They put us up at the St. George Hotel. Marvelous indoor pool, we had in the basement. We had that until commissioning then we made little shakedown cruises on the NORTH CAROLINA after that. You know more about the history of that, I guess, where we went and such. Out into the Atlantic, I am sure, to Norfolk, I believe was one of our ports destination. I can recall after having put to see in the NORTH CAROLINA, we went to Portland, Maine. What a difficulty harbor that was to get into. Twisting, turning, excellent navigation by whoever the navigator was at that time.

[While you were up there, you had some picket boats to check for submarines.]

Yes, right.

[During the outfitting process, when you were still at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, exactly what did the officers do? What was your rank at the time?]

I was an ensign at the time.

[What was your duty?]

Actually to come aboard and check the progress of the ship and break yourself into what you would be doing. In my case, I was the engine propulsion aft at four of the boiler rooms and engine rooms. An engine propulsion aft is one ensign and propulsion forward was another. The electrical room, I haven't been aboard the ship. I think they call it the electrical room was another officer. I was started off at propulsion aft. Remember the chief engineer was a gentleman Lieutenant Commander Dole [Doyle?]. Very savvy guy. As a matter of fact, they called him Savvy Dole [Doyle?]. Is he written up?

[I have heard them talk about him.]

He would kind of give us help in identifying what our jobs and duties would be- supervising construction and finishing up of the ship in that area. You have got to realize that everything had to be pretty darn sealed and such, because what goes through these pipes is 600 degree steam, super heated steam. Any little leaks in steam, you just can't feel and put your finger on it because it just burns and scalds immediately. It has to be supervised very carefully that all this work was being completed properly. I supposed that would be a kind of inspection each day. You get a report each day. You get orders of the day in the morning and you do what you have to do during the day. Familiarize with your crew and station and such and then go back to the hotel. So it was pretty nice duty.

[Of course, there is plenty of night life in New York for a young officer?]

Yes. That was not difficult at all. The subway was right in from of the basement of the lower level of the St. George over to New York. That was delightful. It was a happy period. I really had the all expense paid tour from the Navy. That cruiser, BROOKLYN, the four-stack destroyer, SANDS, touring all those areas and such. Cruising all those areas. The NORTH CAROLINA commissioned in New York. As you say, the proximity to New York, Broadway, and all the other glamorous parts. Of course, on to the submarine service. I have pleasant memories of the Navy all the way around.

[How long were you on the NORTH CAROLINA?]

Two and a half years. I was on attached to it in January or February of 1941 and I left it in July of 1943.

[You were in the engineering department the entire time that you were on it?]

The entire time. I moved up to the electrical officer in my later stages, but I never got top side.

[After the shakedown cruises, what are your recollections? Of course, the NORTH CAROLINA went to the Pacific.]

Squeezing through the Panama Canal. I can remember that. It just barely got through the width of it there. You could reach out and see the passage. I always admired the pilot who was able to get us through there. I think we cruised directly to the New Maya in the South Pacific. I don't think we stopped at either Long Beach or Hawaii. I think we moved on and I believe your records will show that better than mine. Many days at sea of just standing your watch and off watch, and then again on watch. Of course, drills that you would perform. I wasn't involved much with gunnery, obviously. There are the drills and the usual sea routine. Mostly a matter of just getting there.

[This is probably something I should know, but I have never asked this question before I don't believe. Did the officers meet regularly for conferences, planning sessions, information sessions, or did you just, day after day, go about the assigned duties?]

I don't recall any planning sessions. I do not recall that. You of course, had your assigned place in the ward room for eating purposes and you had breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I think in that time being, it was done on an individual basis. I don't recall any. We had our orders of the day again. We would have a meeting every morning. You might say a formation. But that was just an individual division. I don't recall any executive session. Realize I was an ensign. I was possibly a part of the overall planning.

[You answered to Maxwell?]

Well, Dole. Maxwell, yes, I certainly do remember. Was Dole [Doyle?] a part of it or am I thinking of another ship?

[Dole (Doyle?) was in engineering department. I am not sure of the chair of command.]

Certainly Commander W. S. Maxwell. He was just a great guy. I saw his picture as a matter of fact there. I believe he was a Polish immigrant.

[He worked his way up through the ranks.]

He worked his way up through the ranks, became a lieutenant commander, and was chief engineer. He started off as assistant to Dole [Doyle?], I believe, I am pretty sure that it true.

[Captain Hustvedt left you early on after the shakedown. Captain Badger assumed command of the ship and was probably commander most of the time you were aboard, wasn't he?]

Probably so. Captain Fort came aboard, too. I was on there a long time, two and a half years. I went through quite a few papers?

[We had Admiral Fort's papers.]

Commander Shepard was a fine gentleman, too. He was the original executive officer. Andrew Shepard. He was a fine gentlemen and an excellent executive officer. Hustvedt was kind of a typical officer to me. He would be kind of dignified, formal, had a beautiful daughter, whom I never got that close to. A very attractive lady.

[I know his sons, I know Earl Hustvedt very well. I don't know the daughter. Mrs. Hustvedt just died within the past four or five years. In fact, I did a short interview with her.]

I was just looking over the officers. Lieutenant Commander Thackrey was an excellent gunnery officer.

[Joe Stryker was one who was very popular.]

Joe Stryker was very good too. Was he the exec?

[Yes.]

Oh, yes. He was a great guy. I forget, what did he do later on? Did he go into submarines, did he? But yes, he was a very fine gentleman.

[How about T. J. Van Metre, do you remember him?]

I remember the name, but I can't remember much about him. I saw his name there. What was his position?

[Talk to us a bit about your experiences in the Pacific, your recollections?]

The first part of it, I think we went directly to Noumea. We were operating in and out of there. This must have been early on, directly after the war had started. Incidentally, an interesting point, what we were doing at Pearl Harbor, you see. The NORTH CAROLINA was in the Naval Shipyard in New York. I was in the Paramount Theater watching Frank Sinatra. That was my initiation into World War II. After that of course, we went through the canal to Noumea, based in Noumea. We had many weeks there, I recall. Operating in and out, which of course is far south of the activity up in Guadalcanal way to the north in Abordees (?). Then we eventually got out into it. Operating farther north as the Japs came farther south. Our first big action I believe was the Eastern Solomons. Up to that time, we had just been cruising back and forth, kind of waiting for something to happen. The carriers and destroyers, other parts of the Navy, I believe, were farther north into it. We were not involved until this battle of the Eastern Solomon's. At that time, I was in the engine room, an E Officer (electrical officer). It always interests me, any kind of emergency you weren't prepared for in the electrical office. You didn't have enough generators on and you had to phase these in at the same time the turrets were springing into activity tremendous drains and drags on electricity. You were trying somehow to phase in more generators and keep it all up. Sometimes it would not happen. KAPOOM! You would lose all your power. You would have to start all over again. So that being an electrical officer in emergency action was quite a post to be at--quite a station. For the crew certainly.

[You could hear the Japanese were coming, you said.]

Right. I guess the first experience we knew we were in trouble. That is going back to the torpedoing. The battle of Eastern Solomons is different from the days in the torpedoing. Let's get through the Eastern Solomons. I don't remember whether that was before the torpedoing. It had to be before the torpedoing because I was down below decks and I didn't hear or see any of the action. We were just doing full power on full twists and turns to avoid the air craft coming in. I think we got off rather lightly in that.

[You were talking about building up your electrical current, what happened if you lost your current in the midst of an attack like that?]

By that time, we would have enough generators on board. Initially, if it were an emergency situation and everybody manning their stations and starting to exercise the equipment, then there would be a tremendous drag upon the electrical and we would have that danger. No. Once we got everything on board, and all the generators cut in, we didn't have any problem with enough electricity. It was a challenge getting everything all set up.

[That wouldn't affect the movement of the ship itself, would it? That would just affect the guns and the radar and what have you as far as your fighting capabilities.]

Right. As far as the engine room was concerned, we had the enunciators that would give us full speed ahead or two-thirds speed. That was the only direction we had from the bridge. So we really weren't involved that much. Just the only concern that if they were torpedo planes or whatever; that we were pretty vulnerable down there. Again with the six hundred degree steam that could let loose at any time and any rupturing of the steam lines.

[You were involved in the shelling of Guadalcanal, were you not during that time?]

It's possible, I don't recall that. I vividly recall the torpedoing where I was sitting up, having revisited my state room up there. It was a quiet Sunday afternoon or whatever afternoon, and we had just finished censuring mail and we were back up. I guess we had gotten mail somehow or another from a visiting ship. I was back up playing bridge. All of a sudden, without any warning. . . the staterooms up forward were very close to where the torpedo hit between number one and two turrets there. The biggest loudest damn bang I have ever heard shuddering back. . .

[So you were not at general quarters when that happened at all?]

No. Three startled pairs of eyes are all that I can recall, playing bridge, you see. The whole table got up. It was tremendous. Unfortunately, we had the damage control team up there and I think fifteen or twenty of them were entombed in there, with all the water tight doors were closed. They were checking the compartments for soundness and such. That is just about where the torpedo hit. They were entombed from all the time that we started back from where we were hit to Pearl Harbor. That was very sober cruise.

[Was there any panic?]

Was there any panic? I think everybody ran for their quarters. Their general quarters station. I remember Bud Lancoupe (?), my class of 1941 very good friend was the assistant officer of the deck up there. He said, "Just absolutely amazing, looking over at the HORNET and seeing this great black cloud of smoke." Obviously something was happening over there. He wasn't even sure it was hit, it might just have been a fire on board. Then all of a sudden, whatever on the bow, just off the port bow, I guess it was, this wake appeared and before they knew it.even if you turned the wheel to try to avoid it, the NORTH CAROLINA responded so slowly, it would take you a full minute to get any kind of a response at all. They were just kind of sitting ducks. Those two incidents, the excitement of the battles of the Eastern Solomons and the torpedoing were the most exciting experiences aboard the CAROLINA for me.

[Talk a little bit about Eastern Solomons campaign. This was your first real initiation to fire hostile fire. What were your feelings during that?]

I would say, concern. I wasn't in the active forces firing. If you were probably manning the guns you were doing a job, doing what you had to do. When you are down below decks, and you were merely responding to commands from the bridge and checking all of your stations to make sure that the gauges were reading properly and such. It was an item of suspense, of concern, not knowing what the hell was really going on.

[I think I would rather be where I could see.]

I think so, under those conditions any way. That is about all I can tell you in the action end of the NORTH CAROLINA. I can remember ninety days at sea, without pulling into port. It was just boredom, cruising back and forth. Standing your watch and that was about it.

[How did that impact on morale?]

It caused me to personally volunteer for the submarine service or the underwater demolition. Both of them came through. I took the submarine service. I think it encouraged people to want to do something. If you are out there fighting a war, let's go ahead and do it. Let's get on something that is going to be more active. It's just the boredom of it all is what caught up with me.

[You were looking for action?]

Well, yes. As long as I was going to be doing it. My brother was killed on the BARTON on the destroyer part, that gave me a little more incentive to get more action. Other people, I guess you just take it in stride. That is what it is. But we got back to Pearl Harbor. It was three marvelous months in Pearl Harbor undergoing overhaul. That is where some the ninety days at sea.

[Where did you spend your time during that ninety days?]

Well, Hawaiian, and what is that big hotel next to it? Obviously it was a ship under overhaul, it wasn't much to do. Again, we would gather in the morning for orders and sometimes you would even come back to the ship. You would have liberty for two or three days. Mainly again supervising the rebuilding of the ship, getting it ship shape. If wasn't that much to do. Three glorious months in Pearl Harbor.

[Pearl Harbor, I am sure they have done an amazing amount of work and all, I would think you still see the impact of December 7, 1941.]

You certainly could. The ship that is still there, the ARIZONA.

[A question came up this morning that I had never heard mentioned before. The enlisted men that I was talking with had no knowledge at all of it. You had a relatively small number of black about the NORTH CAROLINA.]

Yes, usually in the mess.

[The officers, of course, were the only ones that came in contact with them entirely. Can you give me a little insight into that?]

I don't know whether they stayed with the crew.

[The crew member said they had no contact with them at all. They were only in the officers' mess.]

There must have been a special quarters for them up near the wardroom. Yes. They were the ones that did the serving of the mess and such.

[How many were there aboard?]

How many officers were there to serve. The number of officers was around 100. There must have been twenty or so, a couple of dozen. Incidentally, the same thing in the submarine, we had black mess attendants.

[Why were they brought aboard for mess attendants, when there were many other duties? I know this is still a time of segregation and the military at that time were very precise and I would have thought that there would have been other duties other than waiting tables that even in a segregated society they would been assigned to.]

Not so.

[What happened when the ship went to general quarters, did they have a battle station, or did they just remain in the gallery?]

I don't recall them having a battle station. It might have been ammunition passers, probably were, but I don't recall. Again they wouldn't be in the so called black gang, so I wouldn't know that. I should know it.

[I was talking to two members of the engineering force this morning, and neither one of them had any knowledge at all, other than that there were black men on board.]

I didn't know that they weren't quartered in the regular quarters, I guess there must have been a special section assigned to them.

In the commissioning, the PRINCE OF WALES, I can recall, and Phil Spitalny and his All-Girl Band played on the fantail. The commissioning ceremony was really pretty high class. I used to have the duty as boarding officer in the shipyard harbor, which meant that if we had visiting ships then I would put my sword and my official gear on and go over and board a British Ship or a French Ship or whatever ship pulled in. I would call on the Captain and being that we were the senior ship in port and present to him hospitality and tell them about the Harbor and such. I can recall that they served liquor aboard those and we would have maybe a gin or gin and water, that was their drink. Whereas it might be rather formal going aboard, by the time I had a couple of gin and waters, we became fast buddies. I remember being boarding officer was a rather good assignment, in other words. In the North Atlantic, it was rough. We were in the North Atlantic and it was very rough there, I have a question. Was there a senior officer lost, is there any record of that? A rear admiral that was lost.

[That was from the WASHINGTON, that is what I've always been told, that it was a Captain lost from the WASHINGTON.]

I wasn't sure.

[Do you have any specific recollections of that because I have asked that question of many people who served on the WASHINGTON and they didn't have it?]

The calm, the Hebrides, and all our cruising around Noumea, and the Hebrides, and such, there was never any storms out there. It was always great cruising. You can imagine being aboard the ship on the foxhole in those rough seas, fetching and rolling. One was inclined to get ever so little bit sick. I remember checking the shaft, too. We had to go way back in the after balls of the area there when were at high speed. This is part of the engineering duties. How rather extremely loud and not terrifying and hearing these crunch, crunch and you had to check that area for leaks or whatever. It was always a kind of interesting assignment.

[How many decks down was that back into the?]

Five. How many decks does the CAROLINA have? It was right at four or five decks probably. I guess that is about it to my recollections there.

[Did any of the other officers on board with you that you had particular recollections of either good or bad?]

Well of course, Maxwell, he was a great guy. I enjoyed him, very personable, and knowledgeable individual. Bud Lancoupe (?) was a good friend of mine. He was the assistant officer of the deck up there when it was torpedoed. We used to go ashore regularly. As a matter of fact, he and I were always the first one when we pulled in at some interesting place, like as I recall, Fiji, Bud was first at the gangway with his golf clubs practically. All I can recall is that Bud was a very good friend of mine. Another fellow was Monell, who is listed as the assistant navigator here.

Just an interesting note, this is a personal not, he was called Bunny Monell. His folks were very wealthy people--Monell Metal--and he was the son and the wealth heir apparent. He was made assistant navigator because he had navigated his mother's yacht. He was very knowledgeable in navigation and that is how he got the job as assistant navigator on the NORTH CAROLINA was because he had so effectively and efficiently been navigator on his mother's yacht.

[I thought most yachtsmen wound up in DEs rather than in battleships.]

That was old Bunny Monell. He was a good friend, of course, my roommate.

[I've yet to find a navy man who didn't have a few good sea stories, particular anecdotes that have remained strong them over the years. Whether they were events that happened on shore or on ship or otherwise that they. . .]

I can't relay any to you. They were all just dates with nurses or softball experiences. Nothing really penetratingly different from any other stories. I am afraid I can't help you too much on that.

[When you left the NORTH CAROLINA in July of 1943, you said that after you decided that you were interested in more action, where was the NORTH CAROLINA when your orders came through for sub school?]

I recollect Pearl Harbor. I think she was back in Pearl Harbor or was she was in Pearl Harbor. Your records don't show where she was at certain. It could have been in the South Pacific. I recollect flying from there to the Gilberts to Hawaii and back to the States, so it could have been an advance base, too. It probably was an advance base.

[Where did you go into training for subs, at Groton, Connecticut?]

A.R. Wright (?) Sub School in New London. I was there for three months and then back out to Perth, Western Australia, and assigned to the USS HADDO SS-255. I started off two war patrols as the gunnery officer, and the last three as executive officer.

[You were gunnery officer?]

Yes, first two patrols. Execs the last three patrols. The first three under Chester Nimitz, Jr. We had a pretty good record. We had sixty thousand tonnage ships.

[Describe some of your patrols that you went on from out of Perth. I take it that the station was there in Perth and you were running patrols out there in the South Pacific from there.]

Well, we had many interesting experiences, of course. I remember one in particular, this was one of the last patrols we had. We had a sound seeking torpedo which is the first of its kind. We had gone in and made an attack. Quite successful we had sunk a number of ships and swung around and fired all our torpedoes except this sound seeking one. We were making our usual "Get the hell out of there escape" from things. This was in the days when we were in shallow water. We were attacking close to shore and the submarine never likes to get close to shore because you submerge and you get the hell kicked out of you by anything attacking you. Well, it was foggy at that time. We were leaving the shore where we had done this damage to the ships. Maybe three or four various kinds, merchant. We were going, you might say, east. This was in the East China Sea, just off Korea. We were going in one direction and all of a sudden out of the fog came this patrol craft close aboard and he passed right by us and then came around and started to swing chasing us, of course. It was foggy, all he could see was his mass. And I am sure all he could see was our mass.

[You hadn't tried to torpedo him or anything?]

No, we hadn't. But the radar showed it closing from 2100 yards, 2000, or 1900. We could not drive because we were too shallow, so we fired this target-seeking torpedo which would home on the enemy's screws. We fired this last torpedo we had and waited about a minute or two and all of a sudden a great explosion, an orange flame up in the side. We sunk this patrol boat. But had he been able to close on us, we were in trouble because we didn't have that good of a surface protections, guns and such.

[How large a patrol boat was it?]

I think it was proved to be 1200 tons, a good sized one that could have really raked us over and given us hell. That is just one of many incidents.

[What were the submarine duties in contrast to a battleship's duties? Was there much adjustment?]

Psychologically, I guess, because you were constantly having something happen to you or either getting attacked by air craft or making attacks yourself and being deaf charged and just the general pain and agony of it, I guess. I can remember we were stationed in Perth. We would go back after every patrol and that is way far south. We got ourselves all reconditioned after twenty three days of reconditioning. And rest camp and such and then start back up North again for I would say 4000 miles or such up off the Philippines. I was just thinking how can they go back into this thing again. Once you got into it, the day to day routine was a just a matter of survival. You were after those guys and they were after you and you did the best you, could.

[With the submarine, there is very little capabilities for defending yourself. It is either attack of flee, isn't it?]

Of course, in those days, you were fleeing submerged at 2 or 3 knots, 3 miles an hour, 4 or 5 miles per hour was your top speed, but you couldn't go too fast because your batteries would go out. You could not evade too much successfully under water. So you took a pounding sometimes.

[What is your recollection of the first time you were depth charged?]

I have a very good recollection of that because we were the first ones to use magnetic torpedoes. Which is where you wouldn't fire at the ship you would fire under the ship. The magnetism of the torpedo would be attracted by the ship's hull and it would explode. Chester Nimitz helped develop this. So ought we do but load them up on our first patrol. My first patrol with him. We had a perfect setup, a tanker with one escort, daylight, and made our attack with three torpedoes. Absolutely nothing happened. Just a great. . . all it did was stir up the wake and later on it dove and exploded of its own when it hit the bottom. We didn't really hear much of that. All that did was to occasion a great attack by depth charge attack by convoying ship. But that was my first attack and just the excitement of shooting it and thinking here we had a certain target and the darn things didn't work. Subsequently, we deactivated all those magnetic torpedoes and just had them on detonation of the exploder alone. Then they worked and we had a successful patrol. That was my first attack. The missing of this perfectly set up target, the subsequent depth charging and just the fear to some extent.

[Did you wonder whether you were going to get out of that alive?]

Absolutely.

[Depth chargers coming down around you?]

Depth chargers coming down around you, for sure. That happened a lot.

[This was not part of the problem that was earlier in the war where you had faulty detonators?]

No. They were going too deep. The torpedoes were going too deep. This was a faulty detonator in the sense that it was magnetically operated, but it was only used by a few boats because Chester Nimitz helped develop it and he was the first to use it. It was subsequently determined to be inoperative and went back to the old fly contact. When you hit the bow, to throw the ship it wouldn't detonate. But there are many stories.

[Early in the war they had a lot of trouble with duds?]

Yes. There are many other stories on the submarine end of it. There is one where Nimitz was the skipper in this case. We were making an attack, submerged attack, and all of a sudden, the convoying destroyer saw our sun reflection of the periscope and he came after us and the target closed from fifteen hundred to a thousand, we saw you weren't going to evade it. We had to fire at this, what they called the down the throat, he is coming right at you like that, we fired a spread of three torpedoes, fortunately we headed for the bow, knocked the bow off, and then we had no more torpedoes, as I recall. So we hung around until the end--we fired all our torpedoes--until the end of the day and this ship was sitting there helpless. It eventually got a tug to tow it back into a harbor and we surfaced that night and rendezvous with the. . . there is more to the story than that. . . we did have one torpedo left in the stern. We made an about face, 180 degree turn and fired this one torpedo. We should have knocked that ship off, you see. It just had the bow knocked off already. Only one torpedo left in the stern and somehow we missed it. We had not figured on it backing down apparently. It was backing down so the input of the speed was incorrect and we missed it in front of it and the bow. Anyway, we surfaced that night and got together, we were the wolfpack. Sam Dealey. Did you ever hear of that name, a very famous skipper? Chester told Sam that we had, side by side at night, the two boats, and that we had this destroyer with the bow shot off. It had been towed into the harbor. Sam Dealey went in the next day and that was the last I ever heard of the HARDER. They attacked the destroyer, but they in turn were attacked and so that was the end of the HARDER. So that was one of the tragic stories of submarine life. It was a tough life, I would say.

[When you did fire your torpedoes at that one ship that was coming at you, they did not have other escort vessels that come out and depth charge you?]

No. They didn't. It was just a single destroyer. He must have been returning from something or other and we saw him and closed in on them, but he saw the reflection on the periscope and came over. We attacked him and knocked his bow off and did not sink him completely. Tried to sink him with our last torpedo and did not do it. That was the tragic thing of it all.

[The submarine service is in some respects, kind of elite society among Navy officers, was it not?]

I was say so, yes. And the crew too, to a certain extent I would say. As a matter of fact, I just went to a reunion of our HADDO group in Indianapolis. They had the sub vets convention there in Indianapolis, over Labor Day. Twenty-one of us got together from various patrols that we made. A couple of days there reliving memories and such. That was great.

[You remained with the HADDO for the remainder of the war?]

No. I got off. After her, I made patrols fifth through ninth and then she made one more patrol and I got off then and I was transferred as prospective commanding officer to a ship and the war ended before I was assigned a boat, submarine, a boat. I was there at the ceremonies on the MISSOURI, I can recall.

[What were you attached to at the time?]

At a submarine tender, the Prodeous, I believe. Subsequently, I was put in charge of the ammunition depot, demilitarizing some of that. Like they had a lot of one and two man subs, two and three man subs that were beached. It was a matter of going up and unscrewing exploders.

[Was that here stateside?]

That was in Japan. That was in Hiroshima, the port, I believe. I was in charge of that part of the subbase there, the submarine base in Hiroshima. For demilitarizing the Japanese submarines.

[Think about your recollections of going ashore in Japan here at the end of the war, being assigned to the port of Hiroshima. The city had just been destroyed by the atomic bomb. Do you have any particular recollections?]

Absolutely fantastic. For some reason or another, I got a jeep and I decided, just by myself to do sightseeing. I traveled between Hiroshima and Yokohama, and everything was burned. It had been absolutely decimated. Yokohama, all you would see would be a bathtub, for instance, left on a whole city block. Darned if I wasn't able to cruise around in my little jeep, an American officer in uniform, not the least bit attacked or ugly words sent to me. I did my sightseeing in one day and went back to the station and that was it. I was amazed at how they accepted the American forces then. They were completely overwhelmed, completely subjugated. There was no resistance whatsoever. That was quite an experience.

[Nothing much left of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was it?]

No. Very little. It was Yokosuka, I think was the place, not Hiroshima. That is where they dropped the bomb. It was Yokosuka, that was the naval port, which is about thirty miles from Yokohama. I think I got into Tokyo, too. Sight see in Tokyo to a degree. That was pretty well, but Yokohama was definitely the decimated one.

[Did you find the Japanese people to be very cooperative during this period?]

Yes, absolutely. As a matter of fact they were manning their boats and taking torpedoes out to sea and dumping them or giving them the deep six of whatever was required to deactivate the base. Ammunition and destroying of that, and unscrewing the exploders, although most of them were deactivated--two and three man subs, but you had to go down inside and make sure that the exploders were unscrewed.

[You had Japanese personnel doing that?]

Or ourselves. One or the other. We started it off, then we got them to do it. A touchy little job.

[No accidents, though.]

No accidents. No fortunately.

[How long did this last?]

A couple of months, I suppose. Then the fruties (?) went back to the States and I was detached and sent to Bureau of Ordinance for a year and a half. Then I resigned and I was one of the first officers out of the Navy, actually, in my class.

[Did you leave in 1947?]

Yes, 1947.

[Decided that you just didn't want to make a career of it?]

Yes, I thought I had seen all of the Navy, I wanted to have. I thought I would try civilian life and I had a good friend who was an officer of a company. So I went into sales engineering of that company and stayed in that industry--the die casting industry--for my civilian career.

[And they didn't call you back for Korea?]

No. I resigned actually.

[I thought they could still tap you.]

Well, they said, either I stayed in the reserve until the Korean thing and they said, either get active or get out. I said, "Okay, I guess I will get out." So I resigned my commission. I was a commander by that time.

[That was going to be my next question. What was your rank at that time?]

I ended up as a commander.

[You received a number of decorations during the war. I take it that was from submarine duty. Comment on the engagements they represented.]

Two silver stars and a bronze star, as for the patrols. We got a letter of commendation from the Navy and Marine Corp, some special ship board award or two.

[You got a citation of some type, I think.]

Yes, personally, I got two silver stars and a bronze star.

[They were for the patrols rather than from a particular engagement you were involved in.]

Three silver stars, actually. They were for the patrols, right. The successful patrols. We had five war patrols and one of them was unsuccessful. Because we didn't see any ships. Every time we would go after, they would radio us what the position of convoys, they had broken the Japs code and the Japs were very faithful about reporting where they were going to be, latitude and longitude, certain days and evening and such. We would go over there and sure enough they would right through there at night. They didn't have radar or any way of knowing you were there. Make your attack and it was great. But on that fourth patrol, we did not, every time we would start to go to one of these positions some other sub would beat us or something happened that we weren't able to encounter any enemy ships. So we put in seventy five days at sea without having an attack.

[Didn't you have zones that you worked in so that the subs wouldn't cross each other?]

Oh, heavens yes. We were assigned certain zones. There were wolfpacks--two or three of you would be in a particular battle zone in the latter stage of the war. That is how the HARDER and the HADDO happened to be together, as I was mentioning there. They went after the ship that we weren't able to finish off. By the way that was a very brave action by Dealey, because that was very shallow water, and he couldn't dive much. It was in a shallow bay that this ship went. He didn't have to do that. This guy, Dealey, he was the one who sank five destroyers in one patrol there. He got a congressional medal of honor. Going in there was almost fool-hearty, but he did. He was just one of those guys, hell-bent for anything.

[What were they hit by?]

Surface ships, depth chargers.

[Other that had come in.]

Yes, to help the destroyer. See they were pretty close to Manila. So it didn't take too much.

[You moved from one zone to another, did you not, at different patrols, because you were talking about operating in the South China Sea at some time, and at another time you were up off Japan.]

In our earlier patrols with Nimitz we were off Manila. With Commander Frank Lynch, Captain Lynch, we were in the South China Seas between Korea and China. We had pretty good success there, very good success, as a matter of fact, under him. It just depended upon the luck of the draw. There are always little interesting things like one time we made our attack, sunk maybe one or two ships. We were being depth charged. All of a sudden, all the depth charging stopped. We were kind of breathing a sigh of relief. Everybody went, the officers to the ward room, crew to their stations and normal quarters. All of a sudden, we heard a great scrapping at the bow, all the way down the side of the ship. This was a mine cable. Had we drawn that cable down, we were submerged, that mine would have clunked against the boat and gone we would have been. We had gotten into a mine field. We did a quick 180 turn and got the hell out of there. These things go on all the time on a submarine. You don't have to be sunk by depth charges, you can get into mine fields. There were some uncharted areas there for you. Exciting life. But that is far from the NORTH CAROLINA, so let me not bore you with my battle stories.

[For the purpose of the people here at the USS NORTH CAROLINA, they are interested in the NORTH CAROLINA. I am interested in all of the Naval History. I had a motive in keeping you on the subs because it is something we are interested in for our purposes.]

That was an exciting life on the submarines. The men became so together, there is much togetherness.

[I would think so in such confined quarters as you have on a submarine.]

[How did you know when you were free from a depth charging? When it was safest.]

Well, the pinging would cease. Usually they were after you with their sonar equipment. The pinging would be more distant.

[They didn't ever just stop and sit still on the surface and wait to see you?]

Yes, they would do that sometimes. Yes. Then you would wait until evening if you were submerged. You would cautiously come to the surface. You had radar again. The great beauty of the submarine was that we had radar and they did not. They couldn't even intercept what you were sending until the end of the war. Towards the end of the war, they had the ability to find out when you were sending your radar message out and then you just did it in little spurts.

[So they couldn't track it?]

In the first part of the war they didn't have that, so you had the great glory of being able to surface at night, and get up ahead of them, track them, the convoys whatever, and they were zigzagging and such. That was okay; you would stay outside of them with your radar and you get nicely ahead of them. Hope you hit them in the right zig and go in at them, still with your radar. It may be a couple of thousand yards away, unleash your torpedoes. The chances are, they wouldn't even see you. They might if you got in by the time you made your turn and such but by that time, you fired your torpedoes and you are out of it. Moonlight night they might see you, but usually on a half dark night. . .

[You were just up a periscope level or above, you were pretty well obscured at night.]

You were on the surface at night. They would see your bow wave and maybe more--they would see you--coming in. By the time you had fired your torpedo and hit something, they were pretty terrified of everything. A little panic on their side, too. They weren't too much alert to where you were. So 1944 was a glorious year for submarines. Then in 1945, I guess, late 1945, they got where they could intercept. They knew you were there. I think they even got radar toward the end. So it became pretty tough in the later stages of the war against military craft.

[Having had the experience of being on a battleship that was hit by a torpedo, once you got on the submarine, it gave you a better perspective of your foe, did it not?]

Yes, it sure did. There was always that time speaking of starting up from Perth and sinking at the heart thinking what you were getting back into. You might be submerged on patrol. All of a sudden, we are having the eternal game of bridge or whatever you were playing. All of a sudden, there would be the message shouted down, come down from the control room, "Pinging heard. Thirty degrees pinging heard." You knew damn well you were getting into it again. You were getting into the convoy and its submerge attack and such. Again a little excitement that would precede an attack like that. The emotions of men at sea under going into attack and at attack like that. The emotions of men at sea under going into attack and at attack are really something else. You never know how a guy is going to react. We used to have a guy, our ship's cook. He would get just terrified, but he was a marvelous cook. We would keep him on patrol after patrol. He had no battle station because he was just absolutely terrified _?_ on a head phone. He was such a good cook that we retained him despite he was not worth a damn on any battle station. Of course, as exec, I was responsible for transferring a third of the crew after every patrol. So I was the guy in charge of who was going to come aboard and who was not.

[But you were thinking of dinner.]

I'd say, "Pickens, do you think we should? How about it?"

He'd say, "Yes. I think I could take it for one more patrol." Oh, dear. Great experiences.

[Do you have any other thoughts from the submarine or from the battleship duty?]

I could tell the submarine, but that would take a little separate hour, so I would just as soon not pursue that very much. I can't think of anything at the moment that would be that. . . well, there are many stories there, but I think I had just as soon go further into that.

[The stories are always an important part from the historical perspective, because the one way we look at it is that the ships logs and what have you are available at the national archives to tell where the ships were and the actions they were in. It is the personal accounts and the memories of the people who were aboard that are so important in fleshing out the actual official record.]

There is one more experience and this is one that didn't go off. On this unsuccessful patrol, the skipper got a little desperate here. We got to get some ships sighted. We have to do something. We have been out here sixty days and we only have a few over fifteen more days. I think we ended up by eating sea rations on the way back here on the return. He said, "Let's put a couple of you guys on shore, one of these tropical isles and you can go up to the top of the peak of the isle and you can be a lookout for it. You can see ships. We just on the service, we can't see ships so well. Who would like to volunteer?" Nobody much except the second officer, I felt I should and the third officer. So together we volunteered to do that. We set ashore one morning in our little rubber boat, being attacked by birds and such and got to the shore of this tropical isle and climbed up and God the experiences, fighting tarantulas. We got to one point where if we had gone a little further, there was a great cleft and about two hundred feet down, we would have plunged straight down. Anyway, finally got to the top of this tropical isle. We were there for a day and a half or two days, we saw nothing but sand pans and such. We finally came back and gave up on that mission. The skipper was actually given a reprimand for doing that. For endangering the life of a couple of officers for what they thought was a fruitless mission. I can see his point. He had a good point. It just didn't work out. As a novel approach.

[If he had spotted a convoy. . .]

A novel approach to it. Theoretically, we had all the messages sent about where convoys were and such. There were odd ships going here and there just like that destroyer we came across. So it could have happened. I see this friend of mine, the third officer. I saw him up at this reunion and he was reminding me that he was the guy ahead of me. I was pushing him leader. I was the second officer, I was supposed to be the leader. I was saying, "Al, go up there and do this." He said, "Yes, you did a great job of leadership. You were pushing me all the way up there."

[Any other thoughts?]

I don't really have any concrete thoughts at the moment. I hadn't thought enough about the submarine, I guess if I did I could come up with a few more there, but that is about it, I guess.