[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

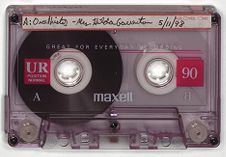

INTERVIEW WITH MRS. IDLDA GARRENTON May 11,1998

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop

Transcribed by: Stacy Wiggins Rideout and Leah Janee Foushee

25 Total pages

Copyright 1998 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any other information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: It's May 11, 1998. My name is Ruth Moskop, and I am here to interview Mrs. Hilda Mather Garrenton. We are at Cypress Glen Retirement Community in Greenville, North Carolina. The purpose of this interview is to learn how Mrs. Garren ton has experienced health care through her experiences as a child in Philadelphia and in her adult life in eastern North Caro1ina where she was the wife of Doctor Connell George Garrenton of Bethel. Good afternoon, Mrs. Garrenton.

HG: Good afternoon.

RM: Do I have your permission to record our conversation?

HG: You do.

RM: Wonderful! Could we start with you telling us when you were born and where?

HG: I was born in New York City March the fourteenth, 1913. Evidently, about two years later my father and mother moved down to Philadelphia and, an interesting thing about being born in New York City... years later when Dr. Garrenton and I wanted to go abroad, and we had to have some verification that I was born in this country, New York was not keeping vital statistics, but North Carolina was. (1:27, Part 1)

RM: My goodness!

HG: We couldn't get over it. So what they did, they found someone who knew that I had been around here at least twelve years. Mr. Lewis over there in the courthouse...

RM: Thank goodness for Mr. Lewis!

HG: Yeah...but we could have gotten practically anybody, you know, just to certify that that was true. Dad had several different type jobs until he settled on working for the Gray instrument company. It had been the Old Queen Company, but they sold it to Mr. Gray and he ran it for quite a while until World War One broke out. Being a Quaker, he would not take any contracts that had to do with ...

RM: The military. (2:27, Part 1)

HG: Military. And so they lost one thing after another. And it got to the point where my dad wanted to buy it. This is what he wanted to spend his life doing. He had a brother that he always would characterize in this way: everything that Moms Mather touches turns to gold. So Uncle Moms showed Dad how to finance all this and he, of course, got it paid for with Morris's help. He helped with the RCA Victor people across the Delaware River over in Camden, New Jersey. And with television, first of all radio, though, doing a lot of the mathematical work. He was a genius in this line.

RM: This is your dad... (3:28, Part 1)

HG: My dad, yes. He went to what was Drexel Institute when he first came down to Philadelphia. Institutes were similar in many respects to our, uh, Pitt Tech, technical schools. Now it is a university, so they couldn't believe that he could do what he could do and one professor accused him of cheating. He said alright put me in a room by myself and give me a test and you just sit up there at your desk and I won't take any notes or anything except the questions and he got a hundred on that.

RM: That showed them...

HG: urn-hum...

RM: Now did he actually build instruments, then, ... design instruments?

HG: Yes...

RM: The Gray instrument company?

HG: Yeah, the Gray Instrument Company. He had a lens grinder there with precision instruments. You have to have some magnification and such. One of the things I remember him talking about was the Palo mar observatory in California. He had figured out the lenses, how they were to be ground for his lens grinder, and they took them out there. They used them for quite a while. But they never get rid of anything like this. They find another use for it, maybe in the same territory. I remember one night he brought a man into the house and told me to set another place at the table. We had lost Mother by that time. And so I did. The man was very nice, and I enjoyed talking to him. I had made beef stew there that day... (5:20, Part 1)

RM: Serves a plenty...

HG: ...Mashed potatoes and string beans and apple pie, and the man relished it. Eventually after talking to Daddy for a while, he left. My dad looked at me and said, "You didn't know who that was did ya?"... I said, "No, I didn't." He said, "That was Admiral Byrd."

RM: Good gracious...

HG: And said I'm going to build some instruments for him to take to the South Pole.

RM: How exciting.

HG: (laughing) What's he want to go down there with all that ice for? And snow and everything. Dad said, "Well, it would probably mean millions of dollars if we can find oil or minerals or something"... whatever they would discover...

RM: Well, that was certainly an important exploration that he assisted with. Your dad, his instruments were right there with Byrd.

HG: Yeah, so there you have it. (6:25, Part 1)

RM: What era would that have been?

HG: Ummm, that's in the 20s and 30s I think. I'll have to look up when Admiral Byrd went down there. It just never registered with me as being anything important. I didn't go around bragging about it to my friends or anything. Later on I did say something about it once in a while...

RM: I understand.

HG: (laughing) Yeah!

RM: It takes a while for something like that to sink in, doesn't it?

HG: It does, especially a child who has no idea what her daddy is doing except, ... I could understand sometimes ... after I did understand why he was a little bit short with the children when he got home. This is such meticulous work. I would go in to some of the areas where they were working on an instrument and it was dust, dust, dust all the time and I said "Why?" They said, "Well someday we're going to put somebody on the moon and a speck of dust in here could make the difference between getting them there because it would gradually keep pushing the instrument or plane off course." (7:43, Part 1)

RM: Fascinating.

HG: And now we can automatical1y clean the air. We didn't have all that then.

RM: They were dusting all the time in the labs

HG: Yeah.

RM: Well, how old were you, do you think, when you were fixing supper? When did you lose your mother?

HG: When I was eleven.

RM: Eleven years old.

HG: We had housekeepers for a while, but Dad came home one day and this particular housekeeper we had had locked one of my brothers up in the closet all day, because she thought he was too sassy. And, uh, when dad got home, she said, "Mr. Mather, you have just got to do something and punish that boy for the way he acted." Dad heard her out then he said, "He's been punished enough." He said,"... and you go upstairs and pack your bags- you don't work here anymore." And so she did, and then two or three days later he sat the four children down and talked to us and said, "Let's try it on our own." And he had charts made out for each one of us with little jobs and everything and the boys were to watch the girls and the girls to watch the boys. And when he wasn't home, we couldn't have other children in the house. When he got home, then we could have company and we could have mixed company over the weekend when he wasn't working. But... (9:23, Part 1)

RM: I need your daddy to make charts for me at my house! Well tell me now... tell us the story of how you met Connell Garrenton.

HG: Well, we had moved up to, Johnson Street in Philadelphia up in the Germantown, Chestnut Hill area. And went to the Second Baptist Church - a large beautiful church and, urn, I had a Girl Scout Troop. Several of the girls got along in their various badge accomplishment work and they got to senior first aid. I wasn't certified to pass them. I was talking to my father about it, and I said if I can get an intern or a registered nurse and he or she come and pass the girls, they'll accept that. Dad said, "I have a young intern in the Bible class. I'll bring him home Sunday." So he did....And I looked at Connell, and I said, "How do you do?" and he said, "How do you do?" Then he went and followed my dad up into the living room. Then when we had everything ready in the dining room, he sat down and nothing crossed his face at all, but later on when we got married he said promise me we will never have leg of lamb or fresh garden peas anymore. I found out, being from the South, he didn't like lamb. (laughing) But you wouldn't have had any idea that. ..he didn't like to eat it, because he would do it just the same. It was every other Sunday, poor soul. It was two years. After the first introduction that Sunday, he called me up the following Tuesday and he said, "Can you swim?" I said, "Yes, I can swim a little." He said, "Well, I can't, and I was wondering if you'd teach me?" I said, "Well, I'll do the best I can." So we went down to the YMCA. It was Ladies Night, Wednesday night, when he came out with his lifesaver trunks on with Senior First Aid lifesaver, you know (laughing).

RM: Oh my goodness! (12:07, Part 1)

HG: I wouldn't get in the water! (laughing) But he coaxed me in there and we went on. He said, "Come on, just edge in carefully." I said," I will not- I am going up here and dive in." And so I did, and we got along fine after that. He went on more hikes with me with those girls. And then other things...

RM: He hiked with you and the Girl Scouts?

HG: Yeah, with my Girl Scouts. They were crazy about him. I couldn't do anything. I just walked along. I enjoyed him so much. He seemed to know so much. I was always asking questions. My mother and father, particularly my mother, had a time answering. For instance, you teach all children that Jesus loves me. I said, "How do I know? I've never seen Jesus except pictures." I said, "How do you know?" That was another time my mother said, "Go out in the yard and play a while." (13:19, Part 1)

RM: Probing questions...

HG: And you sing a song, Rock A Bye Baby and the bough breaking and everything� why would you do that to a baby?

RM: For a lullaby, of all things.

HG: Yes! That was another time I got sent in the yard! But, it just gradually worked out to the place where probably, we would probably get married. He never asked me outright, and I never said anything about that. But we got to talking about what date. His mother and father had been married on June the 30th so we decided that's when we'd get married, the same day. I had met his mother and father. In fact, his father had come up from North Carolina to see who this was he was thinking of marrying.

RM: Good for him.

HG: And, so, you know, really and truly... it was about the halfway mark between the North and the South beginning to heal after the war. His mother had gone South to North Carolina right after. She had a hard time. It's understandable when you think of humanity and several points of view which, but...I thoroughly enjoyed coming except the few little things people were saying. When I'd go down the street people would say "Hey!" and I thought what have I done now? (14:56, Part 1)

RM: That was new to me in North Carolina as well. I grew up in Texas but it was still new to me.

HG: New to you, .... No matter where you go, you're going to run into it. ..my family is scattered over the whole United States and part of England, too.

RM: Tell me now, you married Dr. Garrenton in 1935?

HG: Urn-hum...

RM: And he had...he had completed a course or was working on a course in military field service...medical field service?

HG: Medical field service.

RM: Which he finished in '36, and then, I guess he was appointed, was it in the Army, he was in the reserves or something until1940. And then in 1942 he was called again to go to South Carolina? Did you have to stay in Bethel at that point? (15:58, Part 1)

HG: Most of the time I did. Until he found quarters for us to stay in.

RM: I see.

HG: Mmm-hm.

RM: And then you went down. But he wasn't there for long.

HG: No, they had given all the new medical students and nurses at that time shots for tuberculosis, and one of his best friends died. They all understood that it might be fatal with some of them. And it seemed like the very healthiest of them were the ones that went. Connell was never much of an athlete, but he did develop "swelling of the lymph glands"... they would call it. And, so he was dismissed eventually because they couldn't send him under service.

RM: That may well have been a blessing in disguise. (17:01, Part 1)

HG: That's right. It may have been. But he came back and the hospital in Tarboro bought a small x-ray machine and you could use x-ray to help shrink these glands. He was over there, and they said, "Garrenton, get up here on the table. You're going to be the guinea pig!" And so Dr. Hooks, I remember, was the doctor who administered the treatments, and they gradually shrank.

RM: In Tarboro.

HG: Mm-hmm. Edgecombe General. You're getting ready to...I think the medical school wants to buy that place, I'm not sure but they were dickering about it and so...

RM: When did he have the shot for tuberculosis? In medical school? Up in Philadelphia?

HG: Yes, it was in the medical school up in Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania. See, they were all going out on their internship work and everything. (18:10, Part 1)

RM: And they thought it would help protect them.

HG: ...Build a resistance, because tuberculosis was really a raging type of disease, and now it's corning back. We don't eliminate these, what do you call them, germs?

RM: Yeah, rarely.

HG: They go and they start building protective devices. You probably know a great deal more about that than I do. But, when they come back...

RM: The smallpox story is a happy one, though.

HG: Yes, it is. And you just think of the countries, particularly in Africa, that were wiped out by that type of thing.

RM: There were some little vials of the smallpox vaccination in Dr. Garrenton's medicines and an envelope from the Health Department. Did he work with the Health Department? Did he sort of rotate through the Health Department?

HG: Well the Health Department would come out and ask different doctors to do...

RM: Administer... (19:13, Part 1)

HG: Through this particular area or something. So...

RM: I see. We were talking about that at home, the elimination of smal pox, and my daughter couldn't believe it. It is...it is a very incredible story. One of the very first true successes of the World Health Organization, I guess.

HG: And then the elimination of polio for a long time. I had polio.

RM: Tell us about that.

HG: I was five years old and Philadelphia had its worst epidemic. That was 1918. When Dad was helping Mama put the four children to bed, he lifted me out of the tub and I couldn't stand up. So they took me down to the Philadelphia orthopedic hospital, and the doctors there wanted to break my legs and put them in braces and Mother said, "No I've got to go home and talk to my husband about this." And he had...we had as the family doctor, Dr. Ambler. Dad went down and talked to him. The Sister Kenny method, I think, had just come out. I'm not very clear about all this ... massage and exercise. The orthopedist was a Doctor Porter, I think. Every time I wanted a new pair of shoes I had to go have my feet measured, and I had to have special shoes. I wore high-laced shoes until I was 14 years old, supporting all the time. (21:00, Part 1)

RM: You told us the story about how you had to walk ...

HG: Walk...Mama drew those chalk lines...kitchen floor...and my arms and legs...you know, back and forth she was holding me under the armpits and then she'd reach down and throw a leg, and I was told, "You'll have to walk the rest of your life." And I have found that even since I've been here this leg gives me trouble all the time. And Sarah Haigwood here (at Cypress Glen) is the physical therapist and she's helping me enormously.

RM: I'm glad.

HG: And, so...

RM: What did you do in order to sneak a pair of high heels? I understand you had to...

HG: I saved some pennies and nickels- didn't get any more than a nickel to go to Sunday school with and they didn't get on for several Sundays! And I bought a pair of shoes with little tiny Cuban heels, as we called them then, and slipped them in the house in a brown paper bag and went into the restroom at church and changed my shoes. And some busy body made it her business to tell my father and when we got home he picked me up in his lap and he said, "Now, you understand I spent a lot of money on your legs and everything", and I said, "Yes." He said "Suppose you and your mother go in and talk to Dr. Porter tomorrow and see if you can't wear these without high laces and wear these low heel shoes on Sundays alone." Well, Dr Porter said, "Yes, she can do that, and gradually ease her into just plain Buster Brown oxfords." (23:05, Part 1)

RM: Hallelujah!

HG: Yeah, hallelujah. So we just worked it in that way. Well, I ran and I skated and ice skate and roller-skate...everything! I was determined I was not going to be...I was going to walk!

RM: You're a success story.

HG: So...

RM: For sure. Well, why don't we jump forward in your history a little bit and remember how it was when you came to Bethel. You lived with Connell's parents there.

HG: I lived with his mother. His father had died couple of years before. And his mother wanted to move out of the house and go across the street into a small red brick house and I just couldn't imagine putting somebody out of their home, that they...see, his mother and father had built this house. And Mother Bell and I, we got along famously. A girl couldn't have had a better mother-in-law. She loved to sew, knit, crochet, anything. And Connell right along with her. He wanted anything anybody was doing. If he could try and make something out of it he would do it. Not that he developed a great love for any of those although when I undertook to do the Needler's group, the church area in North Carolina, Methodist Church, he did some of those. He said 'It relaxes me to come home and do this needlepoint'. (24:54, Part 1)

RM: Stitching...

HG: Stitching. She liked music, she liked reading and we both did and we could sit and talk and discuss books. And went to concerts and things together.

RM: Marvelous. You had a good companion.

HG: I had a good companion.

RM: And so did she.

HG: And it eased her a whole lot because she loved her husband just as I did her son. So I remember one night Connell was out on a call. It was about three o'clock in the morning, and I heard her get up. When the back door opened, he had parked the car you know, she said, "Connell, is that you?", and he says, "Yes, Mother." You can go to bed now." Next morning I asked her, "Why in the world didn't you go to bed?" She said, "You wait 'til you have children." But she was a wonderful woman. (26:04, Part 1)

RM: How long was she with you there, in that white house?

HG: About three years. And she had an artery in her stomach, an area burst...

RM: Ruptured...

HG: Ruptured. She was a bleeder, as they used to call it.

RM: A hemophiliac? She...

HG: They just said she was a bleeder. I didn't know what that meant but I did notice she would go to the dentist and her face would tum black and blue. So, it soon cleared up. A very outspoken woman, tool She didn't hold anything back! But she tried to be kind with it all the time. But when once in a while when they went too far, they got back what they were sending. She gave it right back.

RM: I can imagine! Can we step back a generation to the James Garrenton generation? That would have been Cecil's daddy and mother. Was his mother Amanda? (27:10, Part 1)

HG: Yeah. Amanda Bray, B-R-A-Y.

RM: And you had some interesting stories about how James found his patients.

HG: Mmm-hmm. I understand that they say they lived very close to the inland waterway, all that crowd down there, up around Currictuck on the Virginia...just above there...you know...just a few miles before you got to the border. If a patient needed the doctor, very few telephones or anything of that type then, they just put a stick outside with a white rag tied on it and he knew to stop there.

RM: Along the banks...

HG: Along the banks. And if it was back in the territory somewhere and if he hadn't been there before, somebody was standing there beside that urn ...

RM: Flag... (28:08, Part 1)

HG: Flag. Or close by anyway, waiting in a horse and cart or something, you know, and took the doctor back that way.

RM: Back into the patient who needed him.

HG: And he was a man...he didn't like high fluffy biscuits! His wife could make the most wonderful biscuits and he would (smacks hands together) m3.ke em flat! That's the kind he was reared on and he so he wanted his biscuits that way.

RM: Flat.

HG: Flat.

RM: Unleavened.

HG: Unleavened. And uh...l'm not sure where he went to school. I know his dad went to the University of Richmond and graduated from there.

RM: Now which Dad was that?

HG: Connell's dad.

RM: Connell's dad, Cecil.

HG: Yeah, Cecil. But Cecil wanted Connell to go up to University of Pennsylvania or somewhere. Actually, it was, they were gonna send five from the class there at Wake Forest two year medical school and he was supposed to go to Johns Hopkins but he had a ...his mother had a niece whom the Garrenton family had helped a great deal so she said, "I'll room and board Connell to help pay you back." So that would mean the Garrentons wouldn't have to pay for him ... (29:46, Part 1)

RM: Room and board.

HG: Room and board. And the University of Pennsylvania was very close to Johns Hopkins.

RM: Virginia, wasn't it? University of Virginia? Is where Cecil went to school?

HG: Uh ...yeah ...umm-hum.

RM: Then he went to University of Pennsylvania, and while he was on the orthopedic

and neurology ward in Pennsylvania, that's where he met Isabelle?

HG: That's where he met Isabelle.

RM: And how did...Cecil had to do something special for his mother, didn't he, to go to school to earn his money?

HG: Yeah, he had to fish and when he got a barrel full, she gave him three dollars. Can you imagine? But that's...they had to do all kinds of things to make some money...many, many things.

RM: What did she do? Amanda...what did Amanda do with the fish? Do you know? Would she sell them again? (30:47, Part 1)

HG: I think they ran a general store, and I think they would salt them down or something and sell 'em that way.

RM: I wonder where their store was?

HG: That I don't know.

RM: Possibly in Currituck County somewhere.

HG: Probably so. I know Connell had ... an uncle, Uncle Cull, C-U-L-L. Last name was Kinsay, I think, K-I-N-S-A-Y. And, he when he married, he married Amanda Bray, no, not Amanda, it was somebody else. And urn, they ran a general store. So...hard for me. I didn't see them more than once or twice before they started dying out.

RM: I can imagine. Cause that was a couple of generations back. Well, tell us, what do you remember of the clinic, or Dr. Garrenton's office? I guess it was Cecil Garrenton's office originally. (32:02, Part 2)

HG: Yeah ...

RM: That was built behind the house there on Washington Street.

HG: Yeah ...

RM: There's a picture here of it. It looks like a brick building with some siding on it.

HG: Yes, it was. This is the type of clay that was found around Bethel And it was yellow ...

RM: Oh, yellow clay, then.

HG: Yellow clay...

RM: It looks like brick to me and it's...

HG: And they made bricks out of it.

RM: Oh, I see.

HG: And they built the clinic out of it. They were great believers in helping one another. And if you were in the brick building...manufacturing...people would use those bricks. After all they would have to pay somebody to bring them in and the train only, I think, at one time, didn't go through Bethel but once or twice a week.

RM: You mention transportation.... Connie said that she remembers people arriving at the little clinic, this first clinic with carts, drawn by mules. (33:08, Part 1)

HG: By mules, um-humm. See, they would park out here, (points to the road in front of the clinic on the photo)... along there. And the children just thought it was wonderful ...

RM: It must have been.

HG: I didn't know about them going out there petting those mules. But Connell said most of the time the mules are pretty gentle. They wouldn't bring them into town if they were fractious, I guess, or something. These are pecan trees. There were three on that side, this went on down the side of the house and one...two...two in the side yard that goes along on this other side here.

RM: Pecan trees are wonderful. Tell us some more about the building. It looks like there are two stories here in the clinic.

HG: The upper story is where the doctor had his offices and everything and where the patients, the white patients, sat. The black ones came down and went up a brick path, which incidentally... a patient of Connell's later on paid him back by building a brick sidewalk, pretty red brick, this was. There were some steps that went down... three or four... and there was a doorway down there. That's where the black people went and had their waiting room down there. When Dr. Garrenton oftentimes wanted to treat them, they would come up the steps and come into the area where he would treat the patients. (34:52, Part 1)

RM: So the treatment room was upstairs.

HG: Upstairs. See, this is the white waiting room up here, and then this window's over there. And there's a set of steps. I remember one dear little old lady coming down those steps and when she came in next week, Connell said, "Well, how did the medicine do that I gave you?" And she said, "I ain't took a drop of it," and he said, "Why not?" and she said, "When I got out of that door I dropped it and busted it open." He said, "Why didn't you come back in?" and she said, "I was ashamed of myself!"

RM: Bless her heart. Had she gotten better in spite of it?

HG: No! She said, "I ain't no better."...And no wonder why. You know, back in those days, people had to be so careful and we were so ashamed if we made mistakes and such. Today it is so much easier to admit that we all do this at times. (35:55, Part 1)

RM: That little office, it looks like there's a waiting room then, upstairs and the treatment room. And then the doctor's office, is that the way you remember the...?

HG: Well, see, the waiting room is right through most of this and directly behind that, divided in half is part of the office and then behind that is where he had his little laboratory with the microscope and all that kind of ...and where he could make tests and all ... back of where you went and sat down and talked to the doctor or he put you up on the table and examined you and such. It was quite an efficient little set up.

RM: I'll bet it was. What about medicine? He had some medicine he dispensed directly from the office there?

HG: Urnrn-hurn. But there was a good drug store in town. Every time they wanted a new medication, if they felt like they might want to give this to a number of people, they would ask the druggist to stock it. And that's the way the druggist made his living. The doctor made his by ...what he diagnosed and everything and that's the way we did it. (37:15, Part 1)

RM: I understand there was a lady pharmacist in Bethel for a while. Do you remember that?

HG: No, she died before I carne. Now I will probably think of her name after you leave. But it won't come back.

RM: The pharmacy that's there in Bethel now... we stopped there briefly and the pharmacist told us that the pharmacy was on the side of the railroad tracks that were closest to your horne for a while and then it moved across the street.

HG: Across the street. They built that down there and urn...Bob Bowers and Frank Hemingway. Frank Hemingway's father was a doctor in Bethel for a while, too. And the boy went off...in fact, he had three sons. One became a surgeon, one became a preacher and the other one became a pharmacist. (38:29, Part 1)

RM: A pharmacist there in Bethel. That's wonderful.

HG: But the surgeon had to give up surgery because he was allergic to anything you had to use to wash your hands. He had a severe allergy to it he just couldn't do it. The boy who became a preacher, I remember he died, but I don't remember what of. Frank we used to call Bootsie. I can remember Bootsie when he was about that high.

RM: A little boy.

HG: A little boy. And to think he's there now as a pharmacist with grown children. One of my daughters taught him in high school. Then he went off and worked over here in one of the pharmacies, some pharmaceutical drugstore...

RM: What do you remember about the relationship then in 1950, when you all built a new clinic? How did you figure into that? (39:31, Part 2)

HG: How did I figure into it? My dad had died, and he left me some money. My mother had died and she left me some money ... and it amounted, together, I kept it and kept it invested, and I eventually ended up with about $14,000, which was a good amount. They would...the bank would extend us some more money plus the fact we owned our own house and that was security for them. Dr. Jordan was able to borrow some money. And I let them have it at seven per cent interest, and they paid me. It came out that the better way. They passed laws in North Carolina that a wife was entitled to her own money, but the better thing to do was to combine it. And I saw that but Connell had been reared you know where the wife had some and the husband had some, and if the wife died, the husband got everything. If the husband died, the wife only got part. And some way or another it could be evened up if you had a combined bank account. And it took the lawyer talking to him to agree to put everything in both of our names. What he was trying to do was to protect me and the children as much as possible. We were always able to borrow money anytime we needed it...and we got it built... (41:45, Part 1)

RM: Did they share the plans with you? Sounds like you were the primary financier of this operation. Did they let you have a say?

HG: Well, they let me look at them and everything but the only thing I would have changed...We hired an architect from over here to look around, you know, and look at how the clinic would work...the only thing that Dr. Jordan didn't want, he didn't want any place where the help could go back and have a cigarette or something...

RM: Oh - he wanted them to stay on the job.

HG: Yeah! I said, "Now wait a minute Dan, I worked and there's just times when you just have to sit down for a little while."

RM: He didn't want them to have a break room.

HG: No! And I said "Besides that, you're going to want to change clothes once in a while you're doing deliveries and everything back here, you're going to get spattered a little."

RM: Good foresight. (42:46, Part 1)

HG: That was the only thing I could see that needed to be changed but I didn't know what would be required. Wasn't I stupid not to take more interest? But it didn't interest me. All of that technical stuff ...

RM: They probably had it under control!

HG: I just trusted my husband and Dan had good ideas too. Well, it grew and grew and we found we needed another partner. This was at the end of World War II or shortly after that...or maybe later than that, I don't remember.

RM: It would have been in the fifties...

HG: Yeah...

RM: Dan came after World War IT. Dr. Jordan must have been the first partner.

HG: Yeah, he was. And then Bill Moody came. He had been a bomber pilot. And you know, I found in talking...that eventually Dan and Bill died of what we call medically induced ulcers of the stomach. Dan was worried so that his mother's husband, his father, had died and they had lost the farm and everything. Bill worried that his mother was dying of cancer and he said, "I hated to have to bomb towns and see those little children that I was killing." Having a doctor's personality it must have been hell to realize this. Boy, was he bright! I think he was the son Connell would have liked to have. He always called my husband his mentor. (44:42, Part 1)

RM: Is that right?

HG: Um-hmm. See Dan was too near Connell's age.

RM: Did doctors specialize at the clinic, doing different things?

HG: Well, Connell more or less specialized in heart trouble. He had some special training and he came back and taught- what ... ten or twelve doctors we had here in the whole county- Pitt County - and showed then how to take an electrocardiograph and how to read it. They got that done. And they used to call him that fool who was trying to eliminate tuberculosis! Over in Wilson, the School for the Deaf, used to be the sanatorium and so he would send people over there until they got their tuberculosis under control And Dan liked to do deliveries. Bill would take whatever came down the pipe� he loved a challenge! (45:53, Part 1)

RM: That's good.

HG: It was a good set up for a long time.

RM: I understand there were lots of babies delivered in that clinic.

HG: There really were! They liked it- they got a lot of personal attention. Also it was a lot cheaper. You can't run a hospital as cheaply as you can one of those small clinics� there's just no way you can. So they just enjoyed doing that. Connell had relatively small hands. He said that often came in handy not to have a great big hand...

RM: Surgeon's hands.

HG: If his father hadn't gotten sick and died, Connell would have gone on to be a surgeon. In fact, when he was trying, as a young man, to decide what he wanted to do he could have been an engineer as well as a doctor... (46:59, Part 1)

RM: We stopped briefly to turn the tape over. Mrs. Garrenton, you were telling us about how your husband would have been a surgeon had his daddy not died.

HG: Kidney trouble ran in the Garrenton side of the family. They all died around fifty or sixty years of age...several of them. Seemed to be a hereditary type of thing. I told all of our daughters about it when they were going to have children. Of course, one girl couldn't have any children. She'd had to be sterilized. Now do you want me to tell about...

RM: Yeah, tell us about Dr. Connell Garrenton's graduation.

HG: Oh yeah. The Dean of the Medical School University of Pennsylvania at graduation opened his speech with, "Ladies and gentlemen, everything you have learned with the exception of anatomy is now out of date". I can just imagine that they were shocked. He briefly explained something about the sulfa drugs and antibiotics, neuro-surgical techniques, several different kinds of instruments that were coming out that would aid in so many things that they had to do ... and new studies. That was the birth of psychiatry and psychology. At first it was not required and then soon it began to be... (1:51, Part 2)

RM: As a field of study in medical school ...

HG: Medical school, um-hmm. But some things we lost ... began losing with the development over the years of study. Such were home visits. When people began to buy automobiles and our roads began developing better, it was better to come into the hospital or to the doctor's office, and he could do a much better service for you.

RM: Where he had his instruments.

HG: Where he had everything. And truck lines began coming in here, planes began to develop, railroads...there were no such thing as a plane when I first came!

RM: When Connell first practiced medicine in the office behind the house there, he had to go out to deliver babies, didn't he? (3:00, Part 2)

HG: Yes.

RM: How was he contacted at that point?

HG: Well, they would come in on a mule and cart. We did have telephones then and they would go...and if they didn't have one, they knew a neighbor that would help them do it. Or if they couldn't get in, maybe the husband was the only one there with his wife; he would go tell a neighbor. The neighbor would come in and tell him that Mrs. So-and-so was "that way" and needed the doctor.

RM: "That way"!

HG: "That way"! And I didn't know what they were talking about right at first. Just "my wife's that way". And went and told Connell one day and I said "What is it when a woman's that way"? And he said it meant she was going to have a baby!

RM: Was this before your first child was born?

HG: Yes. And urn, income was increasing around here. They began raising something besides tobacco. They did have...did raise some Irish potatoes and there was a cucumber season for a while. And then when they found out they could begin to raise other things, they called them (surga?) beans, but they were soybeans, really. And they found it was...they even had markets abroad where they could sell because they were a wonderful source of protein and such. (4:30, Part 2)

RM: When do you think that happened, the diversification of the farming back then?

HG: Now that I don't know- I mean I think you might have to go to the agricultural department!

RM: ...for that one!

HG: Um-hrnm.

RM: But you saw it happening while you were there?

HG: I did. I saw better schooling corning in and I think part of that was due to television and radio plus the fact that the better income, they were able to send their children to universities or colleges with.

RM: Your kids grew up and went to public school there in Bethel I guess?

HG: Before mine ever finished going to school there, every teacher we had had her Master's...he or she had their Master's degrees.

RM: How wonderful!

HG: They went from a group that would brag, "I made it without so much schooling", to one that saw, "I missed a whole lot, too." (5:33, Part 2)

RM: You know, I just remembered about Cecil Garrenton. Among our papers, is a teacher's certificate for first grade! Did you know that about him? Connell's daddy had a first grade teacher's certificate!

HG: Is that right?

RM: So not only could he catch fish for a living and practice medicine, he could have taught first grade!

HG: Oh my land! He'd a made a good one too! But these are some things that I saw happening...or saw ...some changes in the position of women in medicine too. More of them began going to school...to med school. Another interesting little thing was the advent of these various sprays that would kill insects that farmers had to fight all the time. The one that's more or less outlawed today is DDT. Connell got some of that. Going out to some of these houses where you had to deliver babies...I was always scared to death, and so was his mother, about her husband bringing bed bugs home. And they made it a point never to sit down in an upholstered chair. It was a wooden chair, but he was delivering a woman, waiting for her to, you know, deliver the baby one night and he noticed when he pulled the sheet back there would be a train of little black bugs going across. So he got this can of DDT out and sprayed it. And he called to her husband and said 'Look!' and he said 'Doc! You used magic!' He called the neighbors... (7:26, Part 2)

RM: To see the insect spray...

HG: And they wanted to know where you got that stuff and thought could they use it on their crops and such.

RM: That's a remarkable story.

HG: And I think ... women the world over, although it's not accepted the world over, were glad that the sex of the child is dependent upon the husband and not her! But some of them, they just won't ... But you know, have you ever noticed that maybe we broach and start talking about a change that will affect probably all of us and that's just introduced not broadened or anything but quietly behind the scenes it is. Then twenty years later they bring it out, and they don't much have trouble getting people to accept it. It takes a long time for a new idea to develop. (8:32, Part 2)

RM: That's true.

HG: And then there was no such thing as Medicare or Medicaid. Blue Cross was around for a long time. But we didn't have much of anything else to help us.

RM: The health insurance. I understand that many patients paid for their medical care with food.

HG: Food. It was a long time before I could get Connell Garrenton to eat a piece of cold cake. See, over the weekends, maybe they'd get four or five cakes and you couldn't say anything. The people were trying. Pies and cakes. I remember one dear little black woman, this was after Connell's dad had died and she said 'I knew that we owed this doctor bill'. It was a Sunday and she rang the back doorbell and Mother Belle went and answered it, Mother Belle knew who she was. She had a tiny little ham, dried up; you could have used it for a brick. But she gave it to Mother Belle and she said ''This is the last one I have" ... and Mother Belle looked at her- it was a cold, rainy Sunday- she said, "I couldn't help -I went to the closet and got out a nice heavy, warm sweater and gave it to that woman" because she didn't have warm enough on. Mother Belle was constantly helping somebody! I would do what I could but they didn't need as much when I came, as they had needed so many times before. Plus the fact I hadn't been in it that long to even notice a whole lot of it. (10:25, Part 2)

RM: I bet you felt better, though, when the new clinic was built and Connell didn't have to go far to deliver babies. They could come to him.

HG: And you know we were having these tornadoes around here just last week or so.I remember one night- it wasn't a tornado- we were having a hurricane that day and they called Connell to come look after this girl: 'She's not but thirteen years old and she's that way Doc and we got her in the house and we got her tied down'. Connell went out there and they had pushed two ladder back chairs together you know to make some kind of a cot and had a pillow under her head. But they had all left her when they thought he would arrive and then he could sit and wait until she delivered the baby. He said 'Ifelt so sorry for that child but they didn't want her messing up the bed'.

RM: Well, do you mind? Could we turn to the personal side of your life as the wife of Dr. Garrenton? You had mentioned that he told you right at the beginning of the relationship that medicine would come first. How was that for you? (11:47, Part 2)

HG: Frankly, it didn't sink in right at first. I hadn't experienced anything like this. The more I thought about it ... when the first thing came up, he just looked at me, and I said, "Go ahead". Gradually after that I had to explain to the children that daddy had to go. Of course, once in a while you could be disappointed, and it wasn't that hard, really. I had always been able to entertain myself with something. And he made up so many times later and took me places. Been to England, all over Europe, been to England three times, and I took some classes at the Royal School of Needlework.

RM: What a treat! (13:00, Part 2)

HG: Then we went all over...England, France, Germany, and Italy. Italy was the country I felt so sorry for. During the war they had a time, it was awful...He was so interesting to be around, constantly learning. He would be surprised when I came up with an idea, "I didn't have any idea you could think like that! You rascal." He was teasing me...

RM: Teasing you when he took the time to listen...

HG: Yeah ...

RM: I understand he was interested in all sorts of things...

HG: Constantly! In fact there was only one electrician in Bethel when they first put electricity in the town...Joe...1 can't think of the last name but he would call my husband, "The Pest!" Because Connell followed him around. He wanted to know what he was doing and why he was doing this ... that curiosity never left him. Very interesting people that are like that- somebody who just 'Oh don't bother me about that', you know ...their attitude... (14:34, Part 2)

RM: I understand that he liked gadgets. Connie wrote that he had a Minox. spy camera and what else did she say? A calculator, a miniature calculator, and some other things she said in the drawer.

HG: Everything like that that came out he had to find out how it worked and if possible he wanted one. I told him one time when he wanted me to have every kind of gadget in the kitchen. I said "Connell, there's corning a time when all these children are going to all be gone...." He always had help for me. I bleed under the skin very easily and when my first two girls were three and four years old...not that old, maybe two and three...that's when little girls wore sun-suits with ruffles on the bottom and I ironed ruffles. Thirty-two sun-suits I ironed that day and when I got up my arms were black and blue up to here. He said, "You don't do anymore ironing." So he got me a black woman, she could iron beautifully. But we...we had a lot of them. We worked bills out that way. He took very good care of me. (16:05, Part 2)

RM: There's a cabinet behind you on the wall that has a trumpet in it and a ukulele. It's a beautiful glass fronted cabinet with red velvet behind it. Tell me about those instruments.

HG: Well, he played the trumpet. Six. years through Wake Forest he went through pre� med and two years of medical school through Wake Forest, and he played it in high school in Bethel. So practically all his life- when he got big enough to blow, his father bought him this very nice trumpet. He could always play a ukulele. and there's a flute in there and a little...

RM: There's a piccolo...!

HG: Yeah. a piccolo...

RM: It's not a piccolo it's a wooden flute a little black wooden flute. A very special one. (17:08, Part 2)

HG: He could always do something like that.

RM: Did he sing as well?

HG: He could but he had a terrible voice. I was the one that could sing. If I couldn't get it in the choir...see, I'm not a first soprano, I'm a mezzo. Lots of times to fit in I'd have to read it. It was hard for me to get it and he'd just reach over and sing it in my ear. He'd do everybody- the bass, the tenor...every bit of it ...

RM: He could hum the melody line, he could read the melody line, but his projection, he couldn't really make the sounds himself but he could hand it over to somebody else. Isn't that wonderful!

HG: He could do it. He lays that to the fact that they used to have clinics or days when all the children who needed their tonsils out they'd set it up and all these kids their mothers would bring them and they'd...the doctors and nurses would do this wholesale, you might say. (18:20, Part 2)

RM: In Bethel?

HG: In Bethel.

RM: They had their "tonsil days."

HG: Tonsil day. And he said they said they did too much to him. His mother said Connell had a very good voice till they got through with him.

RM: Oh, I see - he was the patient when they took the tonsils.

HG: He was the patient. He was one of the children this time, not the doctor doing the work. Although they did do some of these after I came even.

RM: I understand another thing he got to do was sew people up after fights.

HG: You know. Saturday night would come and I'd almost hate to see it. Because they got into more fights and at that time, the main instrument they would use would be an ice pick. A lot of those had to go to the hospital because it's just a little tiny mark on the outside but they're bleeding underneath. (19:24, Part 2)

RM: Puncture wound.

HG: The ones he sewed up were done with a razor. They used to carry razors somewhere on their body and use these. They'd get drunk and somebody would say something and start something going.

RM: Out came the blades.

HG: ... And we had a few gunshot wounds, ...but we didn't have the problem with drugs. We had some drug addicts. They would come through and if they knew the doctor had his license to dispense drugs, then they would try to make up stories, you know, that they had lost their prescription and such as this. Well, the FBI had notified the local druggist and the doctors in town. It wasn't that widespread the way it is today. We could pretty well keep it under control but once in a while one got loose. (20:32, Part 2)

RM: The FBI would notify the doctors and pharmacists of known abusers?

HG: Um-hmm. Of course we had one or two that the government had given them permission so they could combat the pain of whatever disease they had that was painful all the time and this was the only thing that relieved it. Those poor souls, ... they had to go into hiding almost because the addicts would get after them.

RM: For their drugs.

HG: Somebody would let it leak, you know, from the government that they were on the permissive list. Or it got out...maybe some member of the family told it or some other soul...

RM: I know you've had a very interesting life and contributed a lot yourself to the health care there in Bethel. (21:31, Part 2)

HG: Well, I tried. Actually, I've been very, very blessed. When I hear some of the stories... these poor people around here, you know. You can't pick the paper up today but what it isn't full of stuff going on. I don't know how people combat...

RM: Connie said...she wrote in her letter that she felt she had a really blissful childhood because you didn't ever have to lock the doors of your big house. The windows were open at night, and if somebody came to the window it was because they needed the doctor.

HG: I remember one night waking up, and I heard somebody downstairs. I went to the head of the stairway and I said, "Who's that down there?" "It's Shine Rollins, Mrs. Garrenton." He was one of the village idiots, you know. I said, "Shine, what are you doing in Dr. Garrenton's house?" He said, "Well, I ain't never been in here and I'm just looking around. I ain't going to do nothing." I put on my bathrobe and just sat up at the top of the stair steps. I didn't know if he might slip a little bit. (22:44, Part 2)

RM: Or hurt himself or who knows?

HG: I eventually went to the phone upstairs, and I called Walter Gray. His son is Bradley Gray the realtor who sold our house at Bethel for me, and told him what was going on. He said, "I'll get him Mrs. Garrenton, he does this all the time!"

RM: You helped each other out a lot, didn't you, in that little town?

HG: Yeah, people would do that. If you needed something and you didn't have enough, needed an onion, you know, you knew where you could go get it or another egg or something. That was just wonderful. Loan one another clothes.I remember when one woman was going off to a meeting she came and asked me if she could use my stole, mink stole, I had at that time. Why I ever bought that thing, it's too hot for anything like that around here! But everybody had one so Connell bought me one. (23:51, Part 2)

RM: Well, he was a remarkable person, I know.

HG: He really and truly was.

RM: Took good care of his family and the people in the community, too.

HG: That's right. And we took good care of him as far as we could.

RM: When did he have a stroke? In the early eighties?

HG: He died in '85. The last five years were kind of bad. Dr. Fleming and Dr. Schuppen over here took care of him most of the time and I'd bring him over.

RM: He had closed the clinic down in '75. The Bethel clinic...He sent the patients...the maternity patients to the hospital here in Greenville after that time, didn't he? Is that what...?

HG: Well, both Dr. Jordan and Dr. Moody...Dr. Jordan came over here and Dr. Tucker examined him with his ulcers and everything and told him he had to give up general practice. People don't realize that general practice is very stressful- you are constantly changing. Dan just didn't adapt very well, and you don't really know what it's about till you actually have to get out and have to do it. Dr. Moody, he himself resigned because be said, "I find that I'm trying...I'm trying awfully hard to stay away from morphine, but I slip a dose every once in a while and I am liable to make a serious mistake". So he signed himself...the letters were there at the house. I kept them. He went to Butner where they take care of a lot of people like that. So, of course, they kept everything...he admitted what he was doing. I loved Bill Moody. Really good fella. I loved Dan too. Dan would get mad at me, because I wouldn't fall for him like the women in Bethel did! (26:20, Part 2)

RM: Well, you had your man!

HG: I said I've got a perfectly good man! You go get your own girl. And in fact he had one. Her sister is here now. Malene Irons? She and Fred have both come into Cypress Glen within the past week or so.

RM: I'm going to be interviewing them soon. Now tell me between Malene and Dan Jordan ...Malene's sister?

HG: It was Malene's sister, Ruth; I think...Grant was her name. * That was their name, you know before they got married. Her sister would not marry Dan because she got tuberculosis. She said that wasn't right to marry somebody and saddle them with that. And Dan had always wanted children and she said, "I can't give you any children." It broke his heart...

RM: What a sad story.

HG: ...and hers, too. But, urn, Malene...

RM: She was acting very responsibly, though. (27:24, Part 2)

HG: Yes, I think so.

RM: That was something else in the old days that people took care of.

HG: So she...and he told me, "Well, you married Connell after he had tuberculosis..." and I said, "Dan, it was a different type."

RM: Besides, he didn't have to bear the babies. That makes a difference.

HG: Makes a difference, yes.

RM: So Dr. Garrenton practiced by himself, then?

HG: For quite a while, yes. And after they both left, he was there by himself. But this medical school and everything was just growing by leaps and bounds. And so a good bit of it was being taken care of elsewhere.

RM: It came just in time for him, didn't it?

HG: Just for him, and it all worked out all right. Towards the very last he had no idea who anybody was. He would look at me, and I knew. I'd say, "Connell. This is Hilda." Just like that. (28:35, Part 2)

RM: Good to see ...

HG: He'd go to bed completely dressed, and I'd have to go up there and undress him. Take a shower in the bathroom wouldn't pull the curtain or shut the door. Water everywhere! And I just couldn't fuss. I thought to myself, "There's my life going down the tubes."

RM: Well, it was a mighty good one I know, though. You had a special man.

HG: I wish my kids could have all had him. My oldest girl, Connie's got a good fellow. She broke him in, I think. He came from a family, the Hackneys, the Hackney body building. You see the Coca-Cola truck with a Hackney body on the back, that's who that family was.

RM: Connie's husband. Would you like me stop the tape now? I think we have had a wonderful interview.

HG: Alright. I wish you would...

RM: Thank you so much.

HG: Well, you're welcome. I hope you got what you wanted.

RM: You gave us all sorts of wonderful information. Thank you.

HG: Well, you're welcome! (29:47, Part 2)

Malene Grant Irons' sister's first name was "Isa". (Ruth Moskop)