[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Carl Long

Narrator

Jerrold D. Hopfengardner

Interviewer

March 10, 2014

East Carolina University

Greenville, North Carolina

Carl Long - CL

Jerrold D. Hopfengardner - JH

JH: This oral interview with Mr. Carl Long is being conducted in Rare Book Room, Special Collections, East Carolina University, March 10, 2014, by Jerry Hopfengardner.

Welcome, Carl.

CL: Thanks for having me, Jerry.

JH: You indicate in your book, A Game of [Faith], you were born in Rock Hill, South Carolina, May 9, 1935. Please describe your early childhood days. Give us the names of your parents and your brothers and sisters. (0:45, Part 1)

CL: My mother and father, William Moselle Long, married to Ella Long. I had two brothers older than me by the name of William Henry Long and Bobby Earl Long. My father was a big man, a very big man, a businessman. He was a bootlegger. That's how we made our living, back far as I can remember. But he owned a restaurant. We said a "caf?." That's what they called them back during that time. Everybody would go to this caf?, especially on the weekends. That's when my father would cook fish sandwiches, hotdogs, hamburgers, and they'd drink beer and dance. They had a good time, back far as I can remember. (2:00, Part 1)

Coming up in Rock Hill I wanted to play baseball, but getting back before going to baseball I went to school at West End Elementary School. After leaving there, West End Elementary School, I went to Emmett Scott High School. [After that] I went to Friendship Junior College, and from that I'm going to tell you how I got there. I'd been playing softball with the kids; every day playing softball. When the bell rings I got mad because I had to stop playing. That's how much I liked the game. In the evenings we played. When night come and we had to quit I got mad again because I didn't want to quit. But, during that, my father made the boys go in the cotton fields and pick cotton. I never picked over fifty pounds of cotton in my life. I'd go out there and pick cotton, pick cotton, and I never could pick as much as my other brothers could because they were good at it and I was not and I just didn't like cotton. (3:56, Part 1)

I got a chance to play baseball. We didn't have a baseball. What we did, there [04:11 traction] for cars going up and down the street. We didn't have a bat. I'd go down there in the woods and cut a limb off the tree and put it around my grandmother's wash pot, made a bat out of it. Then we would throw rocks in the street. We pitched rocks to each other: three strikes, you're out. My brothers, they couldn't get me out. I had to strike out on purpose so they wouldn't quit on me. But I had a good life coming up.(4:46, Part 1)

JH: What did you do with your brothers and sister?

CL: What happened, see, I left at an early age to go up to play baseball, but we were fun kids. We'd go to church, and all the time we just had a good life. We took care of each other. Mother, she worked hard doing laundry work, and she could sing like a bird. Sometimes we'll get together and start singing hymns some, [05:28 sitting down by the bed on the quilts]. One day I got up enough nerve to sing one of those songs myself, "Swing low, sweet chariot, coming to carry me home." I started that song and I've been singing that song ever since. (5:45, Part 1)

But I used to go up to the Knothole Gang. There was a Giants farm team and I was in the Knothole Gang. Go to the ballpark and they'll let you in free. Ball hit up in the stands: Guy by the name of Dusty Rhodes said, "Throw me the ball, kid," and I got that ball and throwed it to him, and I fired it to him. He looked stunned when I throwed that ball to him, I throwed it to him so hard. He said, "Son, can you throw that ball like that again?" I told him, "Yes, sir." He throwed the ball up to me. I throwed it right back to him, fired it to him. [Sound effect of speeding ball] He said, "Can you hit?" I said, "I believe I can." He said, "Come on. I want you to come out here tomorrow. I want you to hit a few." I said, "Sir, I cannot, because a black can't play for a white." He said, "I want you to come out here tomorrow." He said, "I want you to hit a few." (7:15, Part 1)

I was out there: first pitch, he threw it to me. [Sound effect of speeding ball] Out of the ballpark. He says, "Sign him up! Sign him up!" He says, "Son, you're good. You're good. You hit the ball good, you throw. Can you catch?" I said, "Yes, sir." I went out there and they hit me some fly balls and I went back there and caught it and fired it to home plate. They had the guys, all the players, standing there looking at me doing that. (8:00, Part 1)

So, what he did, he talked to Buck O'Neil. Buck O'Neil called John William Parker, told [him], "Look, you got a kid down there by the name of Carl Long in your hometown. I'm going to try to see if I can get him to play." John went and talked to my daddy, and my Daddy said, "No, Carl's not going anywhere. He can't go off and play ball with you. He's going to have to stay home and get his education." John told him, said, "Bill, he can [go to school] and go off and play ball during the summer. I'll make sure he'll be back on time to finish school." So my father decided to let me go. (9:05, Part 1)

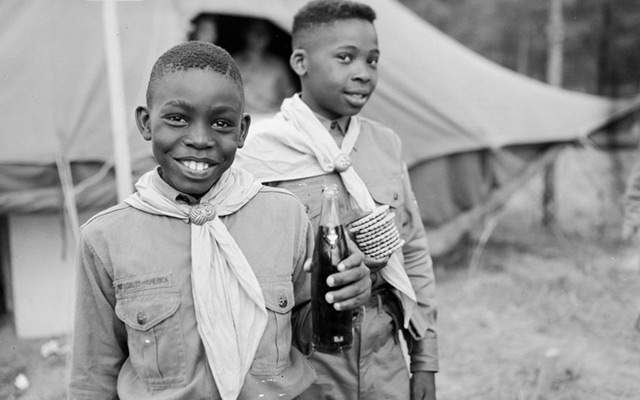

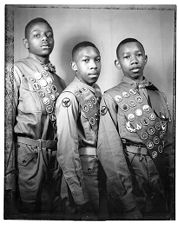

I went off to play with the Philadelphia Stars, the Nashville Stars-they were the Philadelphia Stars and they left Philadelphia and went to Nashville and become the Nashville Stars-1951. Oscar Charleston was the manager, one of the greatest center fielders that ever lived. Oscar says, "Son, by looking at you, you seem to be a good ball player." He said, "You can run, you can throw," he said, "But you're going to become a better hitter than what you are now," which I did. But I was playing with these guys, some of the greatest ball players that I've ever seen in my life. (10:03, Part 1)

JH: Who were some of these players you idolized at that time?

CL: Jackie Robinson was one. Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Hank Thompson,

[Harry] "Suitcase" Simpson, Luke Easter, [Orestes] "Minnie" Mi?oso, Roy Campanella, Jim "Mudcat" Grant. [unclear 10:37]. I don't know if you know him or not. He played with the Atlanta Braves. It wasn't the Atlanta Braves then, it was the Boston Braves. Hank Aaron, Satchel Paige, [Thomas] "Pee Wee" Butts, [Wesley] "Doc" Dennis, Henry Kimbro, Ed Steele. I'm calling some names that you've never heard before. These guys. Brooks. These guys were. Otha Bailey. (11:11, Part 1)

Pee Wee Butts was my roommate. He made me go to bed at night. At a certain time I had to be in the bed. He said, "I'm going to make sure you do the right thing." He wouldn't let me. I wanted a beer and he said, "No, don't get it. Don't get him no beer." He said, "Get him a Pepsi-Cola." Pepsi-Cola, hotdogs, Vienna sausage, bologna, cinnamon buns, Nabs-.

JH: What were your biggest surprises when you signed with the Negro League? (12:00, Part 1)

CL: What happened, they told me, said, "Look, I'm going to give you a hundred and fifty dollars a month to sign." I said, "What?" He said, "I'm going to give you a hundred and fifty dollars to sign the contract." I said, "You're going to pay me for playing baseball?" He said, "Yeah," and he said, "Is there any more down there like that, where you come from?" He said, "Yeah, we're going to pay you for playing baseball." They gave me a dollar and a half a day to eat on and a hundred and fifty dollars a month, but I would have played baseball for nothing, just to get out of the cotton fields down there in South Carolina. (12:49, Part 1)

Went off to play baseball with these guys; it was something else. After the ballgame was over they'd sit back. They let me sit in there. They'd be drinking and I couldn't drink. They wouldn't let me drink nothing. They talked about the game and they said, "Hey, what about that curveball I throwed you? You almost fell on your head." That's what they talked about, talked about the game. Both teams-that played against each other?-sat down. They said, "Well tomorrow, I'm going to knock you down." (13:33, Part 1)

That's when Oscar Charleston come in there and taught me how to roll with the pitches. [He said,] "Don't be scared of the ball. You can get out of the way. If it comes across that plate, you hit it." That's how I learned how to hit. It took me two months to learn how to hit, but I could hit it whenever I hit the ball. I learned how to hit. Hank Aaron was coming up there in '52-that's when they had him come up-hitting that ball everywhere, all over the place. Willie Mays used to come home and want to take center field away from me, and that wasn't happening. He said, "It used to be yours. It's mine now." Buck was just like a little child, just like me. Loved to play. But the places that we went were something. It was awesome. (14:48, Part 1)

JH: Talk a little bit about segregation.

CL: Oh, yes. Some of the places we went, the sheriff used to come down there and tell us, "We want you niggers out of there before the sun go down." We played and we got out of there. Riding down through Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama and places we used to see blacks hanging from the limb of a tree. But I got used to it because of my father. My father told me a long time ago when I was running home. I was riding a bicycle and white boys got after me, tried to catch me, couldn't catch me. The bicycle wasn't going fast enough. I jumped off the bicycle and start pushing it [Laughs] and went off and left. That's how fast I was. (15:51, Part 1)

But I told my daddy, I said, "Dad, white boys running me home, calling me this and calling me that, all kind of 'niggers'." He said, "What's your name, boy?" I said, "My name is Carl Long." He said, "Let that be a lesson. They wasn't talking to you." So that's how I learned how to. When somebody calls me a name, I know. It didn't bother me. It bothered some of the ball players that I played with and against, and I used to tell them the same thing, what my father had told me. (16:38, Part 1)

But the cotton fields down there in Mississippi, down in the Delta, all you could see is white cotton, all over the place, and there'd be a ballpark sitting out there. They had a hotel in Greenwood, Mississippi, a hotel we did stay in. A black man owned that hotel just for ball players, [near] Jackson, Mississippi. It was just a little crossroads in the town and all the rest of it was just cotton, cotton, cotton. I don't know how they found that place out there, but it was a nice place.

JH: How were living conditions when you were on the road?

CL: We stayed in the bus most of the time.

JH: You slept in the bus?(17:42, Part 1)

CL: Slept in the bus, ate in the bus. We couldn't go to a restaurant. Whites owned all the restaurants. We could go. Sometimes they would give us some food out the back door. But a lot of times they wouldn't even serve us at all. We stopped at a grocery store. We invented the take-out. Negro Leaguers invented the take-out. Go in there, get a bag full of cinnamon buns, Pepsi-Colas. They wouldn't even sell us Coca-Colas back then. We had to drink Pepsi-Colas and RCs. [Laughs] Nabs, Vienna sausages, pork-n-beans; that's what we ate. Used to get it and put it in a bag, put it in the bus up overhead, and some nights we'd be riding down the road, you'd hear that bag rattling and look around, "Hey, man! That's my bag!" [and you'd hear], "Shut up!" [Laughs] and he'd go up there and get what he wanted.(19:15, Part 1)

JH: You talked about how it was not uncommon to play three games in one day in different cities.

CL: Oh, yes. Those towns that we played in, little towns, played two ballgames during the day and one ballgame at night in three different towns. Sometimes, riding down the road, we'd see a wheel rolling down there by us. One of the wheels had come off the bus. [Laughs]

But, we played at Nashville, Sulphur Dell. I remember my first homerun I hit. I was playing in Sulphur Dell. That was my first homerun. I hit it hard and I looked at that ball, and he said, "Run! Run!" [unclear 20:20] said, "Run! Run!" and I run, and the ball hit the lights up there and fell on the outside of the ballpark. [Laughs] (20:30, Part 1)

But it taught you something. The Negro League taught you how to play the game. Those guys said, "I'm going to knock you down, young fella," and I said, "You can't hurt me." I always remembered what Oscar Charleston told me. He said, "You watch the ball. Keep your eye on the ball. The ball coming at you, you get out of the way of it." He said, "The ball goes over the plate, you be ready to jump on it." He said, "[unclear 21:12] the next pitch is going to be outside, the middle of the plate, outside." He said, "You be ready for it," and I did. I learned how to hit that way. (21:28, Part 1)

JH: When you were playing in the Negro Leagues at a typical game, was it more comfortable playing as a black man in a Negro league than later in one of the minor leagues where you were one of the few blacks?

CL: Well, what happened, playing with the Negro League you didn't have to prove nothing to nobody. Playing in the white league I had to be three times better than a white person because. It's not that I was showing off; I just wanted to be better. I just wanted to let them know that I could play the game, which I did. I did. I tried to do everything right. They didn't know my speed. They didn't know my speed that well. When I got on base I was going to steal. I was going to steal second, and I was good at it.(22:35, Part 1)

But, playing up in Canada my first year, I hit twenty homeruns. They said, "Son, where'd you learn how to play ball like that?" I said, "I played in the Negro League." And they'd say, "Oh." I know what it means when they said, "Oh," because the ball players that were coming out of the Negro League and going into the minors had to be three times better. Playing up there in Canada, I had a great year. Branch Rickey come up there. The guy throwed me a change-up. I had hit a ball foul out of the ballpark on a fast ball. He ended up throwing that change-up and I was off stride and I hit that ball out of the ballpark. [Laughs] Branch Rickey said, "You hit the ball out of the ballpark on a fast ball [unclear 23:38] [He] throwed you that doggone change-up and you was off stride and you just dropped your wrist on that ball," [Laughs] and that ball went way out of that ballpark.

JH: Talk a little bit about being signed by the Pirates organization. Who came after you? Who scouted you? Who signed you?(24:05, Part 1)

CL: Branch Rickey [was the] chief scout. [unclear 24:11] In 1956 I made the all-star team in Memphis, Tennessee. Come out there. I don't know what they paid me to sign that contract. [unclear 24:33] was so grateful. He was the owner of the team.

JH: After you signed, Saint-Jean's was your first stop.

CL: Saint-Jean's was my first stop.

JH: Okay. Who were some of the outstanding Pittsburgh players when you signed? I'm sure you had heard of some of them. Who were they? (25:00, Part 1)

CL: There was [unclear 25:03] R.C. [Stevens], and then [unclear 25:14] Stewart. He couldn't field worth a darn but he could hit. Every time he hit a homerun I'd get knocked down. [unclear 25:30] knock me down, but I got up. I knowed I was going to take second base. But I got even. They taught me how to get back at these guys. The Negro League taught me this. They said, "They knock you down, lay down a bunt. Make sure the pitcher covers and you run up his back," and I did that a couple of times. Although, if they wanted to fight, I never did fight back. [unclear 26:02] fighting back. That's a black ball player.

JH: How was the game different in the Negro League versus minor league baseball? Was it played differently? (26:26, Part 1)

CL: It was played differently. In the Negro League we went out there and we had fun. Everything was just fun to us. And we played the game so well, so well. We played the game like it was supposed to have been played. But in the minor league we played a little different, a little slower, a whole lot slower. I was used to playing fast, loose, having a lot of fun, hitting the ball, seeing how far, and running the bases. We were doing all the right things in the Negro League. In the Negro League we had so many more people going to the ballpark to watch the Negro League ballplayers than when we played in the minors. It was a pretty good crowd but not like it was in the Negro League. (27:27, Part 1)

JH: Who were some of your buddies when you were playing minor league ball?

CL: Roberto Clemente, Bob Skinner, Bob Beall, Elroy Face, Dick Stuart, Al Jackson, a guy by the name of Benny, Jim [unclear 28:02], Leon Hirsch. I played against a whole lot of major league ballplayers too, a whole bunch of major league ballplayers. After the season we used to get together and barnstorm all over the country, and that's how I learned how to hit major league pitching so well. I wanted to prove to them that I could hit major league. If you played in the Negro League you [unclear 28:46] pitch.

JH: We talked today about player development being important in the minor leagues. That's really why they're there. Was that same emphasis there in the Negro League?

CL: Oh, yes. Now, what we did, we used to play the white teams. We lost some but won more than we lost. We used to play the minor league teams different places. We'd put on a show [unclear 29:24] everywhere we went. More people than I've seen in my life, fifty-one thousand people, 1951 in Kansas City, Missouri. I'd never seen so many people in all my life. They told us, said, "You got to." I went out there and saw all those people, peeped out of the dugout and saw all those people out there, ducked my head back in the dugout, and I told them, I said, "Look, you're going to have to play against them people out there. You might as well go on out there," [Laughs] and I did. (29:58, Part 1)

But the only thing I can tell you, the Negro League was something that you never have seen before. It was a good experience for me because the things that I did, I can see it right now, the places that we went, playing ball in the cotton fields, playing ball in the mine in West Virginia. We'd go over there and play a factory team in West Virginia. They come and tell us, said, "Look, you done scored enough runs now. Slow it down. We want to get out of here tonight." [Laughs] We had to strike out on purpose sometimes so we wouldn't get so many runs.

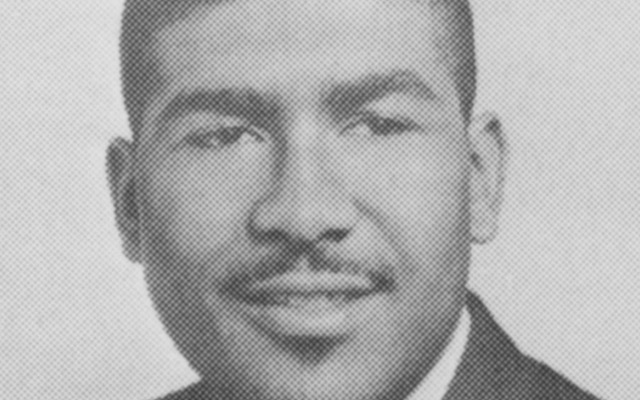

JH: Talk a little bit about when you and Frank Washington broke the color barrier in Kinston.(31:07, Part 1)

CL: Well see, what happened, we left spring training, or I left spring training. Frank caught a plane and went to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, picked up his car. I got on the bus and come up with the white team. I was the only black on the team. They brought me up, right there on Queen Street there in Kinston, told me, "You stay on the bus." All the white players got off the bus and went into the motel. That's where they were staying. They said, "We got another place for you to stay." They wouldn't let me stay at the same motel. (32:00, Part 1)

They took me down to Mark [unclear 32:01] home. I stayed there [unclear 32:04] going back there at 10:00 that morning. He said, "We're going to practice." [unclear 32:13] He said, "We're going to practice at 2:00."

We got there; I went out to the outfield, checking the outfield out. The first thing I did was check the field, see how close it was, judging my distance. [unclear 32:35] I was taught that in the Negro League, taught me. [unclear 32:46] hitter, I know exactly where to play in. Scratch hitter, I know how close I can get in, take a base hit away from the scratch hitters, see, the guys that hit line drives and singles. I played in real shallow. (33:05, Part 1)

I was out there shagging fly balls. Everybody had hit. Jack called me, said, "Hey, Carl! Come on in here and hit one." The first time they throw the pitch I hit it out of the ballpark and I took off running. He said, "Where you going?" I said, "I can get out of here, Jack. I can get it out of here." He said, "Get on back up there and hit some more," and I start hitting that ball [unclear 33:39] [Sound effect of speeding ball] Some out of them went out of the ballpark and some up against the wall. People were up there just clapping their hands, there in Kinston, and I said, "I believe I'm going to have a good year."

JH: Was that 1956, Carl?

CL: Yes, 1956.(34:00, Part 1)

JH: Tell us about your banner year: 111 runs batted in; .291 batting average; eighteen home runs.

CL: Well, I had a whole lot of help, pushing me, pushing me. One week I'd lead the team. The next week Curt Flood would lead the team. The next week Leon Wagner would lead the team. One week Willie McCovey.

We all stayed at the same. The black ballplayers stayed at Mark [unclear 34:37] home, the white players stayed in the motel. We used to get together, go eat after the ballgame and get together at the motel, and talk about things we should've did. Curt got hit in the head twice, and he wouldn't get out. He said, "He couldn't throw hard enough to hurt me." I said, "Curt, you're going to have to learn how to duck, man." [Laughs] I said, "They throw at me all the time." He said, "Yeah, they talk about throwing at you." I said, "They can't hurt me, Curt. I ain't going to let them hurt me. They hit me, I'm going to take it." I said, "I'm going to prove to them that I can take it." Curt said, "Well, I'm going to do the same thing." (35:35, Part 1)

Jack Paepke, my manager, decided to pitch for Kinston, and he said, "I'm going to knock him down." I said, "Skipper, why knock him down?" [He said,] "He's digging in." I said, "Okay." He hit Curt upside the head; Curt went to first base, stole second, and stole third. [Laughter] He'd have loved to go home. He'd have loved to go home. [Laughs] [unclear 36:08] When he came up the next time, Paepke throwed at him again, hit him upside the head. [Laughs] I told him, "Man, can't you duck? Can't you get out of the way of the ball?" I said, "Don't dig in. Don't never dig in." I said, "Let it hit you, not upside the head." I said, [unclear 36:36]

Curt Flood was good. He was good and he was fast too. He and I, and Wagner, we all made the all-star team. This guy from Alabama, redhead, white, throwed at Wagoner the first time he saw him-the first time that day he saw him in the all-star game-throwed at him and hit him right in the back. Wagner said, "I'll get him. I'll get him." When Wagner come up the next time he hit that ball downtown [Laughter] and walked around the bases pointing at him. I said, "You're doing the right thing now. You know he's going to throw at you next time you come up. Just hang loose, that's all."(37:42, Part 1)

But playing, everywhere I went, everywhere I went I was hitting that ball. I was hitting that ball. Played in Greensboro one night; old man sitting back behind the dugout. He had a white shirt on, tobacco juice running down both sides of his cheeks down on that shirt. I come to bat. He said, "Hit that coon upside the head!" I hit the ball out of the ballpark, first pitch. Come to bat the second time. [He said,] "Nigger, you got lucky that time. You got lucky. This one's going [to knock you] off your feet. He's going to hit you off your feet this time." [Sound effect of speeding ball] Out of the ballpark. Old man said, "You got lucky twice." Double. The next time, single. I drove in six runs that night. Little old white lady come down there and told that man, she said, "Why don't you leave those colored boys alone?" She said, "Every time you open your mouth they hit the ball out of the ballpark." We come back on a Sunday-this was on Saturday night when we did all the damage-[and he was sitting there], clean shirt, didn't even open his mouth, and I went oh-for-four. [Laughter]

JH: Wonderful story. Speaking of stories, did you see the Jackie Robinson movie, "42"?

CL: I go to all the movies and talk to the kids.

JH: I guess my first question would be how accurate is that movie?(38:55, Part 1)

CL: A lot things are true. Jackie had a hard time, just like we had a hard time. When Jackie was in the majors was when he had the hard time. They gave him a fit up there in the majors. But he could handle it. He was taught well. He had experienced that in the Negro League. Jackie was a quiet man. He wouldn't go out and party. But Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe. Don Newcombe drank everything, Campanella too, and they used to bring their wives along with them. They were something else. His wife, Ruth, she was something else. She was quite a lady. She drank more than Campanella did.

JH: What former ballplayers are your friends today? I'm sure you have a long list.(41:06, Part 1)

CL: Monte Irvin [unclear 41:12] The ones that are still living. Jim "Mudcat" Grant, Al Jackson, [unclear 41:26], [Trotman] "Trot" Nixon. Dock Ellis, he died a couple years ago, but Dock [41:43 used to worry about me] all the time. Irvin Castille. Otha Bailey, he just died. Just only have three ballplayers-Jim Zapp, Don Wilkinson, and Irvin Castille-the only three ballplayers still living that I played with.

JH: Let's shift gears a little bit, Carl, and talk about life in Kinston and being the. What got you into law enforcement?

CL: Well, I come home, and I wanted to find me a job. I got a job driving a block truck, just for my family. I was the breadwinner although my wife, she was working. But I wanted a job and I got a job driving a block truck. (43:09, Part 1)

The sheriff come to me, said, "I've talked to a whole lot of people around here. I need a black deputy." I knew I didn't want to become no deputy. He says, "It's a clean job. All you do is serve papers." I said, "Man, I don't know nothing about the law." He said, "I'll teach you." He said, [unclear 43:42] He said, "If you don't like it, I'll make sure you get your job back, the one you got now."

Went there; he put me through school. [unclear 44:01] North Carolina [unclear 44:04] Went to a whole lot of small academies. Wilson Academy. I went to Jacksonville. I went to Morehead. I come to East Carolina, studying the law. I went there and I fell in love with it. I was the first black that ever arrested a white person. They had [black police officers] but they couldn't arrest a white person. The sheriff said, "You arrest anybody that break the law. I don't care what color they are." He said, "You're the law." He said, "If the chief over there break the law [unclear 45:09] you arrest him [unclear 45:11]."

He give me that whatchacallit [unclear 45:18] and I helped a whole lot of people that didn't know nothing about the law, helped a whole lot of people, telling them about the law. [unclear 45:32] I helped them, and word got around. Cases I start solving for the police department, people used to tell me everything, everything that went down. They found out I was a fair person. (45:58, Part 1)

Then the chief of police over there said, "Look, we want you over here." He said, "You got benefits," and they didn't have benefits over at the county. He said, "You'd be making more money." He said, "We want you to become a city detective," and I become the first black city detective. (46:35, Part 1)

[End tape, side one]

JH: This is the second side of tape number one, interview with Carl Long. You were the first commercial bus driver in Kinston.

CL: Yes.

JH: Talk a little bit about where your travels took you and some experiences.

CL: I was the first black deputy sheriff there in Kinston, the first black baseball player there in Kinston, the first black bus driver in Kinston, and the first black city detective. After the sheriff got me to become a deputy sheriff I helped a whole lot of people that knew nothing about the law, helped them understand the law. That's when I went to the police department and become a city detective, knocking cases in the head right and left. Helped a whole lot of people. I was the first black that arrested a white person. (1:22, Part 2)

[unclear 01:25] Clerk of Superior Court. I went there and talked to him and told him, I said, "Man, I'm going to have to leave the sheriff's department." He said, "Why?" I said, "Because I'm not making no money." He said, "Can you drive a bus?" The Clerk of Superior Court owned the bus station there in Kinston, told me to go to New Bern, [and said], "Tell him I sent you down there." He sent me down there, in uniform. I go down there, told [unclear 02:07], "Zeke Creech says give me a job." (2:15, Part 2)

The first day he said, "Can you drive the bus now?" I said, "I don't know how to drive no bus." He said, "I'll teach you." I knew how to drive a truck. He said, "It's just like driving a truck. Watch your distance." Sent me to Raleigh. Went through Kinston, Goldsboro, Smithfield, and Raleigh and turned around and come back. [unclear 02:43] passengers, bus full of people. There was people all over the place. Come on back. The next day, [02:58 I like it.] 8:00 in the morning. 12:00 you're off. Go to Raleigh, turn around, come back. I fell in love with that; made a whole lot more money. (3:18, Part 2)

Then they said, "If you really want to make some money, stretch out. Take charters all over the country." Now, I know the road. I know the road map and finding the place where I'm supposed to go to. A lot of places I had just to ask somebody. Towns I went into-I had been to a whole lot of those towns before-just looking for a safe place and asked somebody. Started making a whole lot of money, whole lot of money. Tripled my salary that I was making with the police department and the sheriff's department. Went to California. Come back and they give me a thousand dollar tip. Every time we'd go up and take a tour, we'd go off some place and [I would get] a five or six hundred dollar tip. I'd take that money and set it aside. You know, the salary they were paying me, they paid me good money. (4:44)Part 2

JH: Wonderful. Let's back up a few years and talk about how you met Ella and then about your children, Carl.

CL: Okay. I was playing in Kinston in the Carolina League. They wanted me to come out to a school, and I went out to this school [and they introduced me]. He said, "Carl Long here plays with the Kinston Eagles." Everybody looked: "That's the one plays with the Kinston Eagles?" Because I had been hitting that ball. [Laughs] I'd been hitting that ball. I looked through the window and saw Ella sitting over there, pretty little girl, and I said, "I'm going to marry that girl right there." I did. After the season we got married. (5:56, Part 2)

That was the end of the year, 1956. The next year I went to Mexico City. That's when my son was born. Couldn't hardly wait to. I told her, I said, "I'm coming back to the states. You won't have to come to Mexico City. I'm going to Beaumont, Texas. Bring my son down there." She got on the bus and come down there, and I'm looking for my son, and she ain't. She saw me and she come out there where I was and give somebody else the baby. I'm looking around saying, "Where's my son?" [She said,] "I gave him to somebody to hold." I said, "No, you don't!" I got on that bus and I said, "Where's my son?" The lady that had him was holding him back there. That's the first time I ever saw my son, and I told everybody down there in Beaumont, "This is my son. This is my son." (7:19, Part 2)

I come on back to Kinston and the next year I went to spring training and couldn't throw a lick. Had to give it up. Me and my wife carried my son to Detroit. [I was going] up there to get a job. My brother worked for the Ford Motor Company. I put in an application; they never did call me. I put in an application with the fire department and it come through. I was working at this gas station there making pretty good money. When the fire department called and told me I said, "No, I'm going to stay right here." It's not too far from the house and you got to go way downtown in Detroit [and here] I'm about four blocks from the house, making good money. (8:23, Part 2)

Ella, she was kind of sick. She never did see the ground while she was there in Detroit, so much snow. She was homesick. I said, "What you want to do, honey?" She said, "I want to go home and see Mama." She was an only child. I carried her on back home to Kinston. I said, "Well, I can stay down there." (8:58, Part 2)

We stayed down there and my son grew up and become one of the greatest ball players that played in Kinston; made all-state. After making all-state, majored in electrical engineering. He said, "Daddy, I got a scholarship to go to all these major colleges but I want to go to engineer school." Pat Dye tried to get him to come here to East Carolina, but East Carolina was not an engineer school. Norm Sloan. He went to N.C. State, made the basketball team; the only player on the team that made the Dean's List. Majored in electrical engineering. Played two years of basketball at North Carolina State then said, "Daddy, would you mind if I get off the basketball team?" I said, "Son, it's your life. You do what you got to do." He said, "Daddy, I want to turn my life over to God." I said, "Well, now." (10:21, Part 2)

He stayed at N.C. State, got his bachelor's and master's degrees; left there and went to the University of Kentucky. Three years later, landed a church in Memphis, Tennessee, four thousand members. The membership grew from four thousand to eight thousand five hundred three years later. He said, "Daddy, they're going to send me to the main office in Indianapolis, Indiana." He left and went to Indiana. Three years later he called me and said, "Hey, Daddy." I said, "Yes, son?" He said, "I'm coming home." I said, "To what, son?" I says, "There's nothing there for you. [unclear 11:14] home state." He said, "I got forty churches to oversee in the state of South Carolina." I said, "What?" [He said,] "I'm going to oversee forty churches in the state of South Carolina." He said, "I want you to come down there and talk to all those kids for me." He said, "Don't worry. We're going to pay you to come." So, I go to all of his churches all over the state of South Carolina to talk to the kids, sharing with them, telling them what I'm telling you now. But, great son. (12:00, Part 2)

JH: I can see why you're very proud of him. Talk about your other children a little bit.

CL: Okay. My daughter, oldest daughter, she graduated from Kinston High. She went to college at A&T. Come home after graduating and she landed a job at [unclear 12:25] Training School. Then she got married; then bought a house. She never did live long enough to move in that house. (12:45, Part 2)

My baby girl, she become a nurse, Cynthia. You've met her. That's my baby. She's quite a girl. After my oldest daughter passed away, Cynthia gave birth to a little girl just like my daughter that passed away, identical, just like her. She is a school teacher at Northeast in Kinston. My grandson, he'd cut a hog in a minute. Do you know what I mean by cutting a hog? He went to the Navy and got slick. Now he's looking for a job. I got to find him a job somewhere. But he's all right. Smart. But I tell him, I say, "Don't try to get slick with Granddaddy. You listen to me." (13:55, Part 2)

My daughter and my grandkids, I just got a great family, especially my wife. She keeps me going because I like to go. I looked at her this morning and told her, I said, "Honey, I'm getting too old for this here now." [Laughter]

JH: Well Cynthia is the one who hooked up the two of us, Carl.

CL: Yes, I know.

JH: I'm very appreciative of her efforts to introduce us even though I've never met her; fine young woman.

CL: That's my baby.

JH: Carl, I have one last question. How would you like to be remembered? (14:45, Part 2)

CL: Oh, just. I'd just like it to be remembered that I wanted to play baseball and I got a chance to play baseball and learn from helping somebody. I've been helping people all my life. My daddy told me, said, "If you can help somebody in life there's no point in messing with it." He said, "Help somebody, because you have had a whole lot of help in the past," which I did. [unclear 15:23] I have had a whole lot of help and I don't mind giving back. Although the President of the United States had me up there and talked to me and told me, "I got your back, Carl." He said, "I heard about you." I told him, "Mr. President, I got your back." A week later I received a letter from him. He said, "Carl, see, I told you I got your back." [Laughter] I told him, I said, "Now I ain't going to never come back up there, as cold as it was when inauguration time come around. I almost froze standing out there, and you got out there in your overcoat and walking down there, as cold as it was." I said, "I ain't never been that cold in all my life." (16:23, Part 2)

JH: Well, Carl, in reading your book, A Game of Life, it's apparent to me-.

CL: A Game of Faith.

JH: A Game of Faith. Excuse me. Thank you. It's apparent that you're more interested and you talk more about life and living than you do about baseball.

CL: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. If it hadn't been for baseball no telling what I'd be at today. Baseball taught me about life. Baseball did everything for me, took me all over the country, Canada, South America, Puerto Rico, Mexico City, just everywhere. Baseball is one of the finest games I ever played. I tried to play football, and I was good at football. I tried to play basketball and I never did like it. But my son was great. My son would get out there and say, "Daddy, you can't handle me," and I couldn't handle him. He was so good, and he's smart. Every time he'd shoot a basket: "That's for you, Daddy," [Laughs] just like he was toying with me, playing with me. I was doing the best I could but I just couldn't beat him in basketball.(18:15, Part 2)

JH: Carl, thank you again for sharing your life with us. It's a privilege to know you, believe me.

CL: Thank you, Jerry.

JH: Thank you.

CL: This was some kind of fun. (18:27, Part 2)