[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Ruth Mann

Narrator

Barbara Cartwright

Interviewer

April 8, 2004

Beaufort County, North Carolina

Ruth Mann - RM

Barbara Cartwright - BC

BC: My name is Barbara Cartwright. I'm doing an interview for the oral history project at East Carolina University and I am interviewing Ruth Mann. First off, tell me about when you were born, your mother and daddy, things about your family.

RM: Well, I'm the ninth child of eleven. I had seven brothers and three sisters. I was born in 1938 in Pantego. Born blessed. Didn't realize it until I was much older, but I was really blessed. My parents were both educators but by the time I guess I was five or six my dad no longer taught. My dad farmed. They had land. Then we moved to Virginia during [World War II] and my dad worked in the Navy yard and my mother taught and went back to school. She told us of the experience of travelling back and forth from Elizabeth City to Virginia, where we lived-it was during the war-and she looked so much like a Japanese they arrested her, because she was making this routine trip and they just noticed that every day this woman is making this trip, and every day this woman has this bag. She was keeping her certification renewed for North Carolina because she knew that as soon as the war was over we were going to move back to North Carolina. So that just amazed me, when she told me about that.(1:57, Part 1)

But we did move to Virginia when I was four. I went to kindergarten-because in Virginia they had kindergarten during those days-and I went to first grade. When I came back to North Carolina I was in fourth grade, and of course schools were segregated. We went to a building called the Hall. It had a potbellied heater and all those kinds of things. One teacher taught fourth grade, fifth grade, and sixth grade. The other teacher taught seventh grade and eighth grade. Then we got to go to the brick building, Beaufort County High School, when you got to ninth grade.

BC: Where was this building?

RM: In Pantego.

BC: Okay. (2:53, Part 1)

RM: Right in Pantego, not far from the now unused Beaufort County Elementary School. I laugh a lot about my youth now. [Laughs] I realize that my mother was truly happy when I graduated high school. I was very different. All of us were very different, and we were allowed to be different, but certain things were expected that maybe aren't today. Got my high school education at Beaufort County High School. Got married right out of high school but had a four-year scholarship to A&T State University. I graduated valedictorian of my class. There was only like twenty-six of us in the class. So after being married five years I had to go to school or lose the scholarship, so I went back to school.

BC: So you had been married five years and then you went to school.

RM: And then I went back to school, yes.

BC: So you commuted? (4:13, Part 1)

RM: Well, I commuted-this is the strangest thing-from New York to A&T State University in Greensboro.

BC: You'll have to explain that to me.

RM: Okay. [Laughs] My husband was not thinking about leaving New York. There were no jobs available and segregation was still rampant. So he says, "I'll tell you what we can do. I'll keep the children-my mother is here-and you can go and decide what you really want to do at A&T. If you want to go to school we'll just make arrangements that every two weeks I'll visit you, then the other two weeks you can visit me." We did that. Of course I took a lot of classes at A&T. I took more classes than I was supposed to take, but I got special permission because I was married and my goal was simply to finish school. So instead of four years it took me about three years to do what it would have taken four years to do. So when I got my degree in industrial math I went back to New York and worked on Wall Street for about sixteen years. (5:39, Part 1)

BC: I didn't know that.

RM: Yes, I worked on Wall Street for sixteen years with the Continental Insurance Company. The subsidiary that I worked for was Marine Office of America. They called it MOAC [pronounced mo-ack]. So that was a good experience as well.

BC: So you had some of your children already when you went to school.

RM: I had three of my children when I went to school.

BC: Goodness.

RM: I had three of my children.

BC: And Luther took care of them.

RM: Luther and his mother took care of those children.

BC: So he was from New York? (6:09, Part 1)

RM: No, no, no. My husband is from Pantego.

BC: But his mother moved when he moved.

RM: When her husband passed. Her husband passed when Luther was in tenth grade. They were called sharecrop farmers, so in the winters it was very difficult to do any kind of work, so all of her children had moved to New York. So she moved to New York also and that's what she did; she took care of the children, not just my children but her other children's children as well.

BC: So you worked there sixteen years.

RM: Sixteen years.

BC: And you had four children in the end, right? (6:57, Part 1)

RM: I had four children in the end, and by the time my children were. I loved working on Wall Street but I didn't like city life. You can take the country out of the country, put it in the city, but it's still country. [Laughter] So, for me, it was a struggle to live in the city. I stayed simply because my husband preferred it. Until my kids got to be-my oldest child got to be-thirteen, graduated from the elementary school going to high school, and the city was not, by that time in 1972, as it was in 1956. It was a big change. So I said to my husband right out of the blue. My husband was a store manager for Nedick's and they rotated shifts, so my son had gone on the train to pick up the key from the store for my husband. They thought that was fun, to be able to do that. It made them feel big. He came back and somebody had taken his watch from him, and that just did it for me. I told my husband, "I'm out of here. I'm going to take the kids. We're gone. I can't deal with this. It's time for him now." I kept my children just like little boys. I kept them like prisoners. (8:29, Part 1)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: I truly did. They weren't allowed to go anywhere without either their father or me, I mean nowhere, and they were at the age: "Mommy, we want to go to the park, and we don't want you there with us," that kind of thing. So I told him, I says, "Now, I'm not going to tell you [that] you have to come. I'll always be your wife, but my children and I are gone." He says, "Are you nuts? If you're going I'm going too." So that was good. Away we moved. I just says, "I can't take it." So I called my dad. I says, "I'm coming home." He says, "Okay. What are you going to do about living?" I says, "Well, what do they have down there?" He says, "Got some trailers now." I says, "We'll live in a trailer." So we bought a single-wide trailer, pulled it on my dad's property, my dad had it all hooked up, and in three months we were out of New York. (9:29, Part 1)

BC: That was in '72.

RM: That was in 1972. So got to North Carolina, because my only concern was the children. I didn't think about work. [Laughter] Didn't think about earning a living. My husband was just blessed. We had some relatives that worked at Weyerhaeuser, and during those days if you knew somebody who knew somebody they just took you in. So he went and filled out an application on one day. We moved here on the 14th, I think it was, of July. On the 17th of July he went to work for Weyerhaeuser. Then I went and I interviewed with National Spinning because I did payroll on Wall Street.

BC: I worked in National Spinning at that time.

RM: Did you?

BC: Yes. (10:20, Part 1)

RM: In the interview I took that test, their test, and they called me as soon as I got home: "This is one of the highest scores we've ever had." Then they told me what they were going to pay me. I says, "No. I'm not driving to Washington for that. I know you're joking." I says, "No way." So I says, "I'll look somewhere else," so I just stayed home for a few weeks. Then I got a call one day from National Spinning and they said, "Well, what will you work for?" and I told them what I would work for, and they says, "Come in. You can start tomorrow."

BC: And that was in '72?

RM: That was in 1972. I went to payroll.

BC: I was there in 1972, I believe.

RM: Bless your heart. I went to payroll and I felt so bad, because the girl that was teaching me, that was actually training me on the job, made half of what I was making and she was training me on the job. (11:18, Part 1)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: So I worked there from September until November. I didn't like the hours. The thing that we had to do was to. During payroll time you had to work to 10:00 or 11:00 at night, and I'm driving from Pantego too, and my dad had a fit and my husband had a fit. I says, "Well, I don't have a teaching certification. There's nothing else to do here." So my mother says, "Well, why don't you go over to East Carolina and see if they've got any more of those fellowships they were giving out." So I took off one day from National Spinning and did that, and of course East Carolina is totally segregated. They only had a few blacks; it was totally segregated. Beautiful country school. I went in that day and they says, "If you're willing to teach we'll give you a fellowship." I says, "Well, we're used to living on a lot more than what we're having to live on now." They says, "Well, we'll show you where you can borrow money from College Foundation for you, not for school but for you, and see how that works, and you don't have to pay any school because we're going to give you a fellowship." (12:33, Part 1)

Back then they were on quarters, so in December I left National Spinning and I went to East Carolina, attended there for nine months, and got a teaching certification. By then this is 1974, and I started teaching in 1974.

BC: And you started teaching at Pantego?

RM: No, I taught at Belhaven Elementary School. I had a choice. I did my student teaching at Bath. Mr. Wallace was principal. In Belhaven George [unclear 13:12] was principal. Mr. Wallace offered me a job right away. He says, "I've got a job for you if you want it." But Belhaven's four miles from Pantego and Bath is like seventeen miles from Pantego. I've got four children at home. (13:28, Part 1)

BC: [Laughs] And they're going to be going-.

RM: They're going to Pantego to school, so I think I need to be as close as I can, so I chose Belhaven. So I've been teaching between Belhaven-and that was the strangest thing. Couldn't afford a vacation during those days. You couldn't afford vacation. So my vacation was to go to A&T to work on my master's. [Laughter] So I went away. I wouldn't go to East Carolina. The reason I wouldn't go to East Carolina, because it was too close to home. I had to come home every night.

BC: [Laughs]

RM: So I said to my husband, "I need to work on my master's." He says, "That's fine." He says, "We'll make it. That's fine." I says, "But I want to go to A&T." [He said,] "You want to go to A&T? But you can't come home every night." I says, "No, it's too far, but Mama's right next door, she and Daddy. [Laughs] They can help you with the children. The children are big boys now." (14:28, Part 1)

So that was my vacation. I went for three summers to A&T and I went to one quarter at night at East Carolina. So that third summer I finished my master's, and that summer. Let me see. I had an opportunity to go to Bath again. Lois Chenault. I'll love her forever and ever. I student taught under her and I got an A in my student teaching, which I expected to do, but she just made me think I was the best teacher ever. She just filled my head with all kinds of things, how great I was. [Laughter] She really did. She was excellent.

So I taught in Belhaven for about fifteen years. My teaching degree has been very enjoyable. (15:34, Part 1)

BC: Well during that time, though, when was it that Pantego and Belhaven consolidated?

RM: Okay, Pantego and Belhaven consolidated the last year that my youngest child was in high school, his last year in high school. So I'm thinking that was '88 or '87, something like that.

BC: Probably. But you were at the elementary school. (16:03, Part 1)

[End of recording]

RM: It did affect me because when they closed the high school in Pantego they made John A. Wilkinson a junior high school. I taught sixth grade. So I left the elementary school and went to the junior high school and I taught there for two years. By that time. That's when this school opened. That summer, the second year that I was there, I went to Meredith College for a three-week science workshop, and Ethel Matthews, who was the supervisor for our county, tried to get up with me all summer. I was at Meredith College. (1:06, Part 2)

When I got back to Pantego my husband said, "I wouldn't even tell you while you were away because I didn't want you aggravated about who's trying to call you from the central office. I didn't want you upset about anything so I wouldn't even tell you, but Ethel Matthews has been trying to get up with you."

So right away I called her and she said, "I need you to come in. I want you to go over to the high school," but she lied to me. She said to me, "All you have to teach is math, ninth grade math." I says, "Oh, that's not a bad deal." I says, "And high school is a lot easier." You felt so compelled that every child would learn, and those little ones, they don't know any better. You got to make them do it. High school, well, they're bigger. They can share some of the responsibility. (1:58, Part 2)

BC: You would think. [Laughs]

RM: Yes, you would think. So I came over to Northside. First of all, didn't have a classroom. Had to roam.

BC: I remember that.

RM: You remember that?

BC: Yes, I do.

RM: From room to room. Second of all, had to teach science, and math, and English; taught all three of those in that first year, and I said to Dr. Phillips, "If you don't have a room next year, fine. I can wash windows. I don't have to teach." So they evacuated Coach Proctor from his room [Laughs] and gave me Coach. Then I felt bad. (2:41, Part 2)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: I felt so bad. I says, "I can wash windows. I can do whatever it is I need to do to earn a living, I don't have to teach, but I'm not running up and down the hall and going to everybody's classroom feeling that I didn't leave something right." Even though some of them were great-they wanted you to use whatever you saw that you needed and you didn't have to put it back-like Sandra McCann. I felt very comfortable in her room, didn't worry about it, but some of the teachers I worried about moving the eraser: Did I put it back? [Laughter]

BC: I could probably name those people.

RM: I don't want to name those. [Laughter] But anyway, that's where I got to the point that I don't know whether I really am going to teach forever or not. But I did. It worked out, through all of the principals that have been at Northside. (3:34, Part 2)

Retired. Made a mistake because I didn't have my ducks in a row, meaning I thought you could really enjoy just sitting home and getting up when you want to. It'll drive you to drink if you don't have something else to do.

BC: [Laughs]

RM: .after you've worked all of your life, you know, all of your adult life. You'll start drinking. [Laughs] So I'm thankful that I didn't drink, because I might have been driven to it. But preferably the next time I retire I'll be prepared to retire mentally, mentally prepared to retire.

[Break in recording]

BC: We were studying about the Greensboro sit-ins and-.

RM: I was a part of that.

BC: Well, then I certainly want to hear about that. (4:30, Part 2)

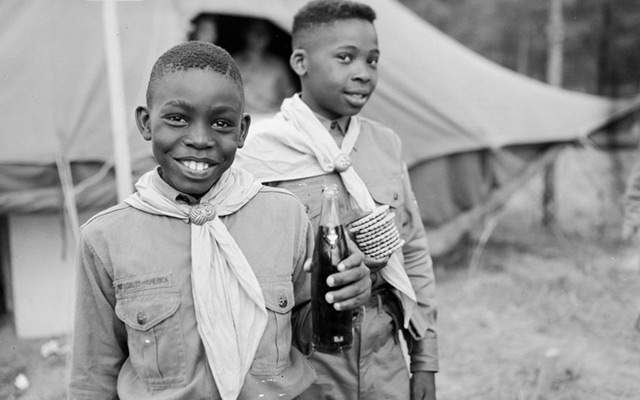

RM: When I returned to college it was 1960, and Jesse Jackson was president of the student government. Met Martin Luther King, because he would visit the black universities, and in political science he was the spokesperson to that class, or something, and we were all involved in it. But [in] downtown Greensboro there was a place called S&W [Cafeteria]. We also had the Greensboro Woman's College there that was white. On Sundays they had the best food at that S&W, so the kids from the Greensboro Woman's College would go in and purchase the food for us and bring it out to us and we would take it back to campus because we weren't allowed to go in.

So during this time the sit-in started in Greensboro. Rose's Department Store, at that time it was called Rose's five-and-dime store. You could go in to Rose's and buy whatever you wanted, because we used to go downtown to buy our toiletries and things and we'd go to Rose's, and you could buy food from the counter but you couldn't sit down. (6:15, Part 2)

So Jesse Jackson and all of those political science students. I was not in political science, but all of the kids came together because we had vespers. Every Wednesday and every Sunday you went to church. It was mandatory that you went. So we would gather together and they would talk about it, and Martin Luther King came down, and Jesse Jackson says, "We're going to be a part of this." And the kids from the Woman's College said, "It's not fair that you guys can't come in and sit and eat." So we boycotted S&W, the kids from all of the colleges and the tech schools around boycotted, and that last Sunday, I'll never forget it, so many people had been arrested in Greensboro from the boycott that all the jails were filled. So there was an old polio hospital-and this is exam time, now-old polio hospital. It was so many students from all of the colleges-black, white, everybody-so many of the community people involved. It was like ten thousand people that were locked up. I was among the group and, guess what? My parents saw me on TV. By that time we had a TV; got a TV in 1949. We had television. They saw me being marched on the bus. (7:54, Part 2)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: They had a hissy. [Laughs] But we were locked up and taken to the old polio hospital. Now, Rose's and the movie theater, after about a week of boycotting, said this is okay. We'll let you in. You can sit down. But S&W closed its doors before they would allow us to come in.

BC: Now the sit-in that gets all the attention is the one at Woolworth's.

RM: At Woolworth's, the five-and-dimes. Yes.

BC: Was that when you were there too?

RM: That's when I was there. That's when I was there, yes, ma'am.

BC: I was telling the kids in my class because, you know, they're all twenty and I'm not, and I was telling them that in Washington I'm almost sure that they just shut the counter down.

RM: Yeah, they did. They did that in-.

BC: They just took it out. (8:48, Part 2)

RM: And no longer would serve.

BC: I think they did in a lot of places.

RM: In a lot of places they did.

BC: That's how they took care of that situation.

RM: That's right. Just took it out and no more serving food. But S&W closed its doors, because that's all they did was serve food. You know, that was a restaurant, and it was cheap. For a dollar those kids would bring us out big bags of food, I mean good home-cooked food.

BC: Right.

RM: So they closed their doors and, like you say, Woolworth's-or Rose's, as we called it.

BC: Well they had both.

RM: They had both, but this was Rose's and Woolworth. I was not at Woolworth. I was in the Rose's thing, but they both stopped serving food. (9:29, Part 2)

BC: Right.

RM: They didn't have a snack bar anymore.

BC: The one in Washington didn't. I remember that.

RM: All of them did that, I believe, if I'm not mistaken.

BC: I think I was vaguely aware of that, but just vaguely.

RM: I was a part of that and now, that I look back, I just say: I knew Martin Luther King. I met Martin Luther King. This was before they had the Washington, D.C. sit-ins and all of that. But when that Washington, D.C. stuff started and all I says, "Oh, it's no big deal. I've marched with Martin Luther King before." [Laughs] "Jesse Jackson? Oh, I was in school with Jesse Jackson, even though I'm older than he," I would say, because when I went back to school I was older that those who were there.

BC: He's not far behind you, I don't think. (10:18, Part 2)

RM: No, he's not. If I'm not mistaken he's sixty-two or sixty-three now, because he was like president of the student government and I had been there two or three years, getting ready to finish up that part of the third year that I was there.

BC: Right.

RM: So, yes. I was a part of that. [Laughs]

BC: That's exciting. Let's talk a little bit about the schools. You were already teaching when they integrated the schools here?

RM: I was grown when they integrated schools in Beaufort County, in North Carolina, when integration actually took place physically, after the law. It was four years or so after they-.

BC: Well, I think it was about '67, '68 actually before-. (11:07, Part 2)

RM: Before they totally integrated. I was out of schools, had not returned to North Carolina. My mother was teaching and my younger brother was still in high school. So during that time I lived in Pantego even though I lived in New York. There wasn't a holiday that came that I was not home. There was not a long weekend, there was not. Any little thing would make me come home, anything. I owned stock in Trailways Bus. [Laughter] Me and my babies, we owned stock in Trailways Bus. (11:40, Part 2)

But my mother taught at the Beaufort County High School and that year they chose. The year that they were going to integrate they chose two teachers-the year before they integrated-two teachers to go to the white school and two white teachers to go to the black school, and they chose my mother, who was Annie Farrow, and they chose Emma Lovett, who was a young black teacher. In the beginning, of course, the people said, "Well, they chose Miss Farrow." Miss Farrow, who was my mother, was very different. She was very, very fair-skinned, and they said, "Well, they chose her. I understand she's an excellent teacher but she's real fair-skinned too." But when they chose Emma then they made that not so, that they chose her because [of her skin color]-because Emma was very dark-skinned but gorgeous to look at, very young, beautiful teacher, and she taught home economics. (12:49, Part 2)

The two white teachers, I understand, that they sent over to the elementary school were those people who had lived in Pantego all of their lives who knew the people in Pantego, both black and white. So I think it made for a very smooth transition. After the fact, you know, when Alton Boomer, who was a little black boy in our community, was the first black student that was sent over to the high school, and the KKK went up and shot in his dad's house. His dad was a minister. But the beautiful thing my dad related to us was that all of the men of Pantego went up that lane to-they call it the Canal Bank, to where Rev. Boomer lived, both black and white men, to show that we're united with this and you cannot... We won't sit by. You won't do this in Pantego. So not only did they find out who it was, but they were punished because of what they did at the time that it was done, and nobody was hurt in that process. (14:03, Part 2)

BC: Except the little boy, probably.

RM: The little boy, he was Alton, and Alton Boomer today just retired from Weyerhaeuser and once in a while he reminisces about it. But he's all right. He's better because of it. So, it was a-.

BC: It was a time, as they say.

RM: It was a time. It was a time. But, you know, we were blessed in Pantego, and I tell people all the time and they look at me like: You didn't come from Pantego. But yes, I did. We were blessed, and I didn't realize how blessed I was. I wasn't raised with prejudices, and people tell me it's because your parents were educators and you didn't have to work, but I did work. I enjoyed working in the fields. I mean, I truly went out to work because I wanted to do it, the only one of my siblings, of the girls, that did it. A couple of the boys did it because we liked having our own money. But we just didn't feel the prejudices because we were sheltered from them. Then in the community, the lawyer, Toppin, his daughter Jane, it was like we were just friends anyway. We would walk to the post office together and when she got her license-she was a year or so older than us-she would pick us up and we'd drive to the post office together. My dad and one of the neighbors would exchange vegetables. My dad grew like the colored butter beans and collards. The neighbor grew like lettuce, radishes, sweet corn. So they exchanged. (15:55, Part 2)

[End of recording]

I didn't feel the prejudices. I didn't ever think about why we didn't go to the grocery store. My dad always went to the grocery store. My mother didn't go to the grocery store. I never thought about it. But my dad didn't allow us to go because he didn't want us to feel the prejudice. So I never understood. I said my mother never goes to the grocery store. My mother never, you know, does certain things. We just didn't do them. The only place we went was to the clothing store, and that was to Hoyt's in Washington and to the Virginia Shop in Belhaven. That's where my mother took us. But we never. And we went to the movies. We had a movie in Belhaven. The blacks were upstairs. I thought nothing of it because I thought that was the best place to be. (0:54, Part 3)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: I never thought about it. We went to the bakery in Belhaven and we just went to the first door, which was always-didn't realize it had "Colored" on the door. But it was the closest door when you left the movies, so we just went in there, and they had the same things on both sides of the counter. They had the same pies, the same honeybuns, the same everything, and I paid no attention to it. But my dad was always right there to pick us up. You go in, you get what you want, and you come back to the truck.

BC: So he was protecting you.

RM: He was protecting us from feeling the prejudices, so I didn't feel the prejudices.

BC: Well the kids in that class don't believe that I didn't. I never realized that something wrong was going on. (1:48, Part 3)

RM: No, because-.

BC: I was insulated from it too, in a way, you know.

RM: Yes, you were, and this is what parents did.

BC: I guess, you know, that was just the way it was.

RM: Just the way it was.

BC: .in my world.

RM: Yes. Now, in Pantego during that time, on the street you come in by [unclear 02:07] now, it was the Russ family, then it was Hazel Harrell, who was black, then it was the Griffin family, then across the street was a white family. It has always been mixed and I never thought anything about it.

BC: My husband's neighborhood was like that. (2:30, Part 3)

RM: We walked down to the post office and there was a little family down there, the Harris family, that were blatantly prejudiced, but by this time we're thirteen, fourteen years old; didn't bother us at all because we beat her up.

BC: [Laughs]

RM: The white kids and the black ones together, we'd beat she and her brother up, throw them over in the yard, and keep on going. We did, and I mean we just didn't think anything of it because Jane was white, Jane's sister was white, the Ratcliffes were white, and we didn't think anything. Pat Johnson's children were white. So we just beat her up. When she'd say bad things we just beat her up and push her over in her yard. [Laughter] So, you know, you were sheltered. Now, when my husband tells the story he tells a whole different story. (3:20, Part 3)

BC: What does he tell?

RM: Well, see, his parents were sharecroppers.

BC: Right.

RM: They moved from place to place. They realized you couldn't go into this store, or if you took the bus you had to go into this side of the station. We never took the bus. My dad always drove us. They had to walk for miles. We lived right next door to the school so it wasn't a big thing for us. We thought nothing about going to school. It was next door. He had to walk about two miles to get to school, so he tells a whole different story. But I was not.and I don't think he was raised with prejudices, like taught prejudices. His prejudices came from living, from experiences, but not being taught in his home. So it makes a difference. (4:22, Part 3)

BC: Yes, it does.

RM: It makes a difference when your beliefs or your thoughts or your feelings come from having lived it than from somebody teaching it to you.

BC: Absolutely.

RM: That's a whole different story.

BC: So when they were going to build this big old school over here, I know in my part of the county.

RM: They didn't want it.

BC: .they didn't want it.

RM: They didn't want it in Pantego either.

BC: Well, I had never really heard anybody from Pantego talk about it. (4:59, Part 3)

RM: They came and snowballed the community. A group of people came and at that time Frank Ambrose was principal of the school, and they snowballed some of the people through him to making it acceptable. You see, for us in Pantego, growing up we were never allowed to go to Belhaven. The only thing we went to Belhaven for was the movies and the bakery, shop at the Virginia Shop, but you could not hang in Belhaven. Morals and values were totally different, so we were taught as kids. Okay? So we couldn't hang in Belhaven.(5:40, Part 3)

Years ago, before integration, there had been an act to integrate the two black schools. The parents of Pantego rented buses and went to Raleigh and said before their children went to Belhaven to school they would close the school and home school their children. This was before integration. This was after Beaufort County High School had been erected-through the people in Pantego, not because of the state. The state said: We will help you once you get your building up and we see what you're doing. That's why the town of Pantego gave that building to the Beaufort County High School alumni, because the black people had actually built that building. (6:34, Part 3)

But, no, the integration. Prior to that the people of Pantego said: My children will not go to Belhaven. My children will not associate with the children in Belhaven. You see, there are all kinds of prejudices, not just because of the color of your skin but because of values and morals. Our people in Pantego, our parents, perceived that the people of Belhaven's morals and values were totally different than ours, so that's why the schools never were integrated or consolidated with the blacks in Belhaven and Pantego. So when the consolidation of this school came it was still like that is totally, utterly unacceptable. The only thing, we couldn't fight it because we didn't have any kids in Pantego. (7:25, Part 3)

BC: That is very interesting.

RM: Yes. No, we didn't want any consolidation.

BC: That was the same thing being said in Bath.

RM: Yes. See, my youngest son, who went to. Would not even go to his. I do not have a graduation picture of my youngest son except for those snapshots that they take. The proof? That is the only picture I have. He would not take pictures. He would not buy a class ring.

BC: Because he was in that first class.

RM: He was in that first class. Nor would he go to the prom or anything else affiliated with [the school.] He did play basketball. He would not play football. He played basketball only because he felt he had to something. He was sick of being in the house. (8:13, Part 3)

BC: [Laughs] Well, my son felt very much the same way coming here.

RM: Yes. He just hated it. So that was a wool pullover for the people.

BC: Well when the Pantego and Belhaven schools were combined that happened like a week before school started?

RM: That's right.

BC: Is that right?

RM: That's right. It was like: "We haven't decided, we haven't decided," and then-boom. "We've decided." Didn't give you a chance to fight it.

BC: No.

RM: This was the strategy. Every day people would go to the Pantego High School and say, "Frank, what's going on?" [and he would say,] "Nothing. It's fine. Nothing. Nothing."

BC: Okay, yes. I know where you're coming from. Tell me about your church.

RM: Oh, God. It's just a blessing from on high.

BC: I saved the best for last. (9:14, Part 3)

RM: It's just a blessing from on high. In fact, we're going. I will be in school again on the 17th of May because we're going to Harrisonburg, Virginia and participate in a celebration with the Mennonite group that came to rebuild our church. We're going on Saturday, we're going to stay Sunday, and we won't leave until Monday to come back. Only God could do what has been done. And you know what I tell people? I says, you know, in the early days, in the early Bible days, after Jesus came and he performed miracles to prove just who he was and what he was able to do, today we've got those same kind of people, nonbelievers, so again he says, "Let me show you what I can do," because there is no way that Weeping Mary Church would be built today or any day with forty members, half of them much older than I. Two thirds of them don't work but live on Social Security. There is no way a church that's valued at $325,000 would be erected one year after it burned. There is no way. I tell you, when I look at it I just simply say it's glory to God, because without Him there would be. And see, God uses all of his people, and He brings you together one way or another. I never knew there were black Mennonites. I know this sounds ignorant to some people. (11:08, Part 3)

BC: Well, I wouldn't have. I didn't know until you just said it.

RM: I would not have known. I said to Bernard. Bernard Martin and Joan Martin, they came down and they scrutinized us, because they said there's so much lying and cheating and making believe going on, and when that group came down and they decided that they were going to help Weeping Mary Church-they were going to furnish all of the labor for us-we had eighty thousand dollars in cash from the insurance. That's all we had. Of course with the contributors, like people from Northside and all [over] Eastern North Carolina, people from New York, people from Georgia heard about this and money just came in. So we ended up with maybe a hundred twenty-five, hundred thirty thousand dollars in cash money. We're still like twenty thousand dollars in debt, but that's all, for furniture and. Everything that we owe is about twenty thousand dollars. (12:14, Part 3)

BC: That is a miracle. [Laughs]

RM: Nobody but God. Nobody. So it was a blessing. People looked at it when that church burned, a hundred thirty-two years of history, and they says, "Oh, my God." I was going, "Thank you, Jesus." Do you know we went out there every month just to patch up and to light heaters and pray that that [unclear 12:40] wood that was there wouldn't catch on fire with us in it, and that the bell wouldn't fall from inside on us. [Laughs] You know, those kinds of things. So I says, "God, thank you," and people looked at me: "Why would you be thanking God for this?" Because He's going to show up. He's going to show you. (12:59, Part 3)

Everybody just knew that was the end of Weeping Mary. People even said, "Why don't you just take the insurance, divide it among the membership, and go on and join." I says, "That's ludicrous." Weeping Mary has a hundred and thirty-two years of history. It's just beginning. Just beginning. My coming back to work has not only been a blessing for me but it's been a blessing for my church, because I contribute one third of my salary to my church, and as long as I work I will do that until that twenty thousand dollars is paid off. Not only that, I got a check in my pocket right now from one of my coworkers, who was not able to give me anything at the time of the burning of the church but God blessed her and she got some unexpected money and she shared that money with me.

BC: I'm going to cry. (13:58, Part 3)

RM: I know, because that's what I'm feeling. That was Peggy Elliott, gave me a check this morning for my church. This shows you that God is one God. He's a God of all of us. There is not a church in this area that has not contributed to our church, either monetarily or otherwise, not one church in this whole area, not one. That says something for where we live.

BC: Oh, yes.

RM: It really does. It says something for where we live.

BC: It does. I said I saved the best for last, but I do want to ask you one more thing. You've been doing this a long time.

RM: Yes. [Laughs]

BC: And things have changed. We all know that.

RM: Oh, gosh. Yes.

BC: So if you.I mean, just say a little bit, because I know we both need to go home, [Laughs] but tell me a little bit about. I guess what I'm looking for is some hope. (15:06, Part 3)

RM: Well, I'm going to tell you what. I've found that children. I don't care about all the change. When I look at the children today, yes; there's a lot of differences. But there are a lot of things that are the same. Children love structure. Children want to be disciplined, and I know that from children who have come back and said to me, "You taught me in fifth grade and you just opened our heads and poured stuff in it."

BC: [Laughs]

RM: I've had other children who said, "Miss Mann, thank you." One of the fellows who was our heating and air. Pamlico Heating and Air, the young man who owns the business, I taught. You know what he said to me when he saw me? He says, "I would not be doing this had it not been for you." I about flipped out. The plumber said to me. I didn't realize I had taught him. He says, "You taught me in fifth grade and sixth grade. Look what your beating my hands made me do." (16:25, Part 3)

BC: [Laughs]

RM: I'm saying this to say, today, the children at Northside-half of them I don't teach-show me the most respect, and anybody who knows me knows that you don't get away. I don't care who it is. If you're wrong, you're wrong, and I will discipline you. But I think they know that I care about them. So I think children need that structure, they need to be disciplined, but they need to know that you truly care. Yes, they're different. They're very different.

BC: [Laughs]

RM: But when you let them know that I've been there, I'm not so old that I don't remember, and there are certain things you can't get over, and I think they-.

BC: You didn't come in on the turnip truck.

RM: No. (17:25, Part 3)

[End of recording]