[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

The

Reminiscences

of

Vice Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt

U. S. Navy (Retired)

U. S. Naval Institute

Annapolis, Maryland

1975

DECLARATION OF TRUST

The undersigned does hereby appoint and designate as his (her) Trustee herein, the Secretary-Treasurer and Publisher of the United States Naval Institute to perform and discharge the following duties, powers, and privileges in connection with the possession and use of a certain taped interview between the undersigned and the Oral History Department of the United States Naval Institute.

1. Classification of Transcript. .

( )a. If classified OPEN, the transcript(s) may be read or the recording(s) audited by the qualified personnel upon presentation of proper credentials, as determined by the Secretary-Treasurer of the U. S. Naval Institute.

( )b. If classified PERMISSION REQUIRED TO CITE OR QUOTE, the user will be required to obtain permission in writing from the interviewee prior to quoting or citing from either the transcript(s) or the recording(s).

( )c. If classified PERMISSION REQUIRED, permission must be obtained in writing from the interviewee before the transcribed interview(s) can be examined or the tape recording(s) audited.

( )d. If classified CLOSED, the transcribed interview(s) and the tape recording(s) will be sealed until a time specified by the interviewee. This may be until the death of the interviewee or for any specified number of years. It is expressly understood that in giving this authorization, I am in no way precluded from placing such restrictions as I may desire upon use of the interview at any time during my lifetime, nor does this authorization in any way affect my rights to the copyright of my literary expressions that may be contained in the interview.

Witness my hand and seal this 2 nd day of April 1975

I hereby accept and consent to the foregoing Declaration of Trust and the powers therein conferred upon me as Trustee:

PREFACE

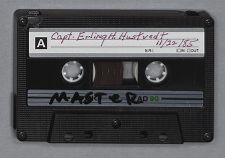

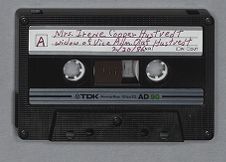

This volume contains the transcript of ten taped inter-

views with Vice Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt, U. S. Navy (Ret.). The interviews were conducted by John T. Mason, Jr. for the Oral History Office of the U. S. Naval Institute and were held in the home of Admiral Hustvedt on Ordway Street in Washington, D. C. They cover a period ranging from November 29, 1973 to June 11, 1974.

Admiral Hustvedt has made minor corrections in the transcript and it has been re-typed, but essentially it remains as spoken by him on tape.

A subject index has been added for convenience. A copy of an earlier interview given by the Admiral to several representatives of the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution has been included in the appendix.

Admiral Hustvedt's career was concerned with Naval Ordnance over a long span with several tours of duty as head of the Experimental Section in the Bureau of Ordnance (dating back as far as 1919) and with another as Production Chief of the Naval Gun Factory (1930). In addition, the Admiral had considerable experience in Battleships dating from World War I. His final tour of duty was in Command of Battleship Division 7 with the Fast Carrier Task Force in the Pacific (World War II).

John T. Mason, Jr.

Director of Oral History

U. S. Naval Institute

May, 1975

Interview No. 1 with Vice Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt, U.S. Navy

(Retired)

Place: His residence in Washington, D.C. Date: Thursday morning, 29 November 1973 Subject: Biography

By: John T. Mason, Jr.

Q: Admiral, I've heard so very much about you from various people. You're almost a legendary figure, you know. I'm delighted, therefore, that you will give us a series of interviews covering your very significant naval career. In as much as this is a biography, a talking biography if you will, I wonder if you'd begin in the traditional way by telling me where you were born, when you were born, and some-thing about your background?

Adm. H.: I'd be glad to. I was born in Chicago, Illinois, in June of 1886. So far as personal background is concerned, my forebears were all Norwegians. They were pioneers in the Middle West. My paternal grandparents came to this country as very young people. My grandmother, I think, at the age of six or seven, and my grandfather at the age of nineteen, both in the early 1840s. They were in Wisconsin - I'm not

Hustvedt #1 - 2

sure whether Wisconsin was a state or territory at that time. They were in Wisconsin in the early 1840s. I think Wisconsin was just about becoming a state at that time. Gold had not yet been discovered in California.

Q: So they stopped there?

Adm. H.: Well, they were too young to be thinking of gold, I think. At any rate, they two, my father's parents, were both born in Telemark in Norway. Incidentally, Telemark is known for being the birthplace of skiing, perhaps, and it may be of interest to remark that a first cousin of my father who was born in Telemark became a ski-jump champion in Norway, and his life and career more or less connected with skiing from then on. He was a member of Amundsen's South Pole expedition. He was the ski expert, and Amundsen in his book on the South Pole discovery recounts that on the last day's trek, when he knew that the immediate vicinity of the pole would be reached that day, put Olaf Bjaaland, his skier, into the lead, so that putatively you might say that Olaf Bjaaland, my father's first cousin, was the first man at the South Pole. Well, that goes back into connections rather far.

Q: What did the family do in Wisconsin? Was it dairying and that sort of thing?

Adm. H.: No. In those days, in Wisconsin, of course, they

were immigrants who came to the United States to acquire land, and that's what they did. They acquired land. My mother's parents came from Norway a little later than that and also acquired land in that same part of Wisconsin. By a curious coincidence, you might say, although my mother and father were born on farms about four miles apart in Wisconsin they never met until my father was in college in Iowa. My mother's brother was a teacher at the college. I think that's a curious set of circumstances.

Q: They weren't quite as mobile as we are!

Adm. H.: No, I should say not. And, incidentally, referring to the mobility of those early days, when my father went from southern Wisconsin to northeastern Iowa to go to college, he went by rail as far as Prairie du Chin, Wisconsin, where there was as yet no bridge. So he went with a small group of lads from his own neighborhood and, after being ferried across the Mississippi at Prairie du Chien, they were able to hire a farmer with a wagon on the other side who hauled their baggage the rest of the way, which was forty-odd miles to Decorah, Iowa, where the college was located.

Q: What college is that Ada. H.: Luther College. And the prospective students trudged alongside the wagon forty miles from Prairie du Chien to Decorah, while their baggage rode.

Hustvedt #1 - 4

Q: I think they were a little more rugged than we are!

Adm. H.: Yes, well, those were pioneer days, of course. I think the remarkable thing is, Admiral, that they sought a college education. Was this a tradition in the family?

Adm. H.: I have no doubt that it was a tradition to seek a good education, but as far as I know, there were no university graduates on either side. I have mentioned my father's first cousin Bjaaland, who was the ski expert and afterwards became a manufacturer of skis in Oslo, but there was a tradition of education behind those people. In Norwegian literature there is a big name that is probably very little known in this country. This country knows a great deal about Ibsen and Bjornson and various others, but the name of Vinje not very well known in the United States. But Vinje was a big literary figure in the Norway of his time, and his family were neighbors in Telemark of my grandfather's family. I'm not sure whether there was a family connection or not, but they came from the same immediate neighborhood. So people there were very literate, although they didn't perhaps get to a university, very many of them. Back in the early days of the nineteenth century I don't suppose there were many from that area who actually went to colleges. But in this country they were quick to establish their institutions, including a college. This institution that I'm speaking of in Decorah, Iowa, was a college established in

Hustvedt #1 - 51

1861, although those were troubled times. They established a college there which flourishes to this day, and it has a very high reputation, incidentally.

Q: Yes. So your father went there to college and prepared himself for what kind of a career?

Adm. H.: For the ministry, actually. That was the principal purpose of that college. Not to serve as a theological seminary but to serve as an institution for the education of young men in the classics. The course that was established there - and it was a one-course institution for a great many years - was highly classical. I can remember, for instance, that when I went from Luther College to the Naval Academy we were engaged in reading the Medea of Euripides, when I left school, and we were engaged in studying the French Revolution. We had finished our mathematics and our physics and, at the time I went to the Naval Academy, I had studied in three modern languages and two dead languages. English, of course, was my mother tongue, Norwegian by inheritance. I didn't regard myself as particularly expert in Norwegian, but I had had all of my religious instruction in Norwegian. We had courses at the college in Norwegian literature. At the college I studied German for four years, including my preparatory department rears. I studied Latin for four years, Greek. for three years.

Q: So you were reading Medea in Greek?

Hustvedt # 1 - 6

Adm. H.: Oh, yes. Yes, indeed. That's the last Greek that I remember from that Course. Of course, we had begun more or less with Xenophon, then the Odyssey and the Iliad. I think every second year student of Greek probably deals with Homer, after he’s learned to read it a bit. But the Medea was the last thing that I can remember in Greek. Latin, I think we were in Virgil. But you don't want all of this

Q: It's very interesting as a background. I should imagine there were very few young men going to the Naval Academy with this kind of a background?

Adm. H.: Oh, I daresay that there were very, very few.

Q: Did your father then become an active clergyman?

Adm. H.: Yes. He was a pioneer clergyman in South Dakota, in the neighborhood of Yankton, and later on in Iowa, at Northwood. He was forced to leave active ministry shortly before I was born on account of a throat affliction that made it very hard for him to preach. But during the rest of his life he was still connected with the church organizations their national treasurer, as head of a church normal school, and as editor of church publications. He was in that sort of church activity all of his active life.

Q: This was the Norwegian Lutheran Church?

Adm. H.: This was what is now known as the American Lutheran

Hustvedt #1 - 7

Church. It was then known as the, Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church because they, ,I suppose naturally, clung to their Norwegian connection for quite a long time, but the Norwegian tag no longer is used. It's now the American Lutheran Church.

Q: I suppose the facility with the Norwegian language has been lost, too, in many of the families?

Adm. H.: Oh, yes. The Norwegian language was used in the church services for years. At the time I was a youngster living at home, English had been introduced in the church, but the principal service - the Sunday forenoon service - was still conducted in Norwegian. Other services were conducted in English and, of course, now the Norwegian has disappeared. I can’t put a time tag on that, but it disappeared during my lifetime.

Q: So you grew up in this atmosphere, a very scholarly background, and a religious one?

Adm. H.: I think it's fair to say that, yes.

Q: What were your intentions in going to Luther College? Did you plan to go into the ministry, too?

Adm. H.: No. I rather definitely planned not to, but I had not fixed my intentions on anything definite. I was still pretty young, of course. I was between eighteen and nineteen when I went to the Academy, but I was fairly well settled that

Hustvedt #1 - 8

I was not going into the ministry.

Q: Was your father unhappy at this prospect?

Adm. H.: At my not going into the ministry? No. No, r think he realized that his calling was not necessarily the calling of his sons - he had four sons, and the eldest did go into the ministry, incidentally. But the eldest left the ministry and went into teaching. He became a teacher of English, as I remember, at the University of Illinois, then the University of Minnesota, and finally the University of California at Los Angeles. He was a part of the original faculty at UCLA and was a full professor at UCLA at the time of his retirement. Incidentally, he became a very highly respected authority on ballad literature because he was able to read Norwegian, he was able to read Danish, if you will, Swedish, Finnish, any of the Scandinavian languages, to say nothing of German. He wrote a couple of books on the topic of ballad literature in all of those northern languages.

Adm. H.: He became, I think, of his time possibly the foremost authority in this country on ballad literature in the Germanic languages. Professor Child of Harvard, I think, was preeminent in that field during his time and my brother studied with him, incidentally. That was digression, wasn't it?

Hustvedt #1 - 9

Q: Yes, but I wanted to ask how you arrived at the idea that you wanted to go to the Naval Academy?

Adm. H.: That was accidental. An uncle of mine was a member of the faculty at Luther College during most of his adult life, and he had been nominated as the for Congress from our home district in the campaign of 1892.

Q: This was Wisconsin?

Adm. H.: No, Decorah, Iowa, Luther College. That's where I grew up. I didn't grow up in Wisconsin, I grew up in Decorah, Iowa, where my father had been sent to college.

Q: And where your uncle was on the staff.

Adm. H.: And my uncle was a member of the faculty for a great many years. While he was a member of the faculty he was nominated by the Democrats for Congress in the campaign of 1892. Well, the campaign of 1892 was one in which the Democrats won, but in the Fourth District of Iowa my uncle lost.

Q: That was the Cleveland campaign?

Adm. H.: That was Cleveland, and presumably as a reward for having put up a good fight he was appointed consul general to Rotterdam by President Cleveland. lie served as such in

Hustvedt #1 - 10

Rotterdam during the Cleveland administration, but when McKinley came in in 1896 there was a change in the office of consul general at Rotterdam and my uncle came back to Luther College. That uncle was my mother's brother. His name was Reque well, Professor Reque was in town one day in spring when he ran across the local congressman, whose name was Haugen, and that name has gone down in history, more or less.

Q: Gilbert Haugen?

Adm. H.: Gilbert N. Haugen.

Q: Yes, I knew him.

Adm. H.: Did you? From Northwood, Iowa. Where did you know him, here in Washington? Yes, Haugen appointed me to the Academy.

Q: Oh, he did, really?

Adm. H.: Yes, it came about in this way. My uncle, L. S. Reque, was in town one day and ran across Congressman Haugen on the street in Decorah, Iowa, where I grew up and went to college and all that. They knew each, other and they stopped and talked and, as they parted, Mr. Haugen said, "Incidentally, Reque, I'm looking for candidates for the Naval Academy. You have a son that's about the right age, haven't your Well, as they discussed it, they found that my cousin was not of the right age because he was just about to turn twenty, but

Hustvedt #1 - 11

my uncle said, "I have a nephew here who might be right for you." So that's the way I was appointed to the Naval Academy!

Q: How did your parents react to this?

Adm. H.: They liked it.

Q: Of course, Norwegians are seafaring people.

Adm. H.: The idea was new to my parents and new to me, but it was perfectly agreeable all around.

Q: So you took the examination and came?

Adm. H.: I took the examination as an alternate and didn’t make the grade, but Mr. Haugen gave me a similar appointment as an alternate in the spring of 1905, and I passed. The principal appointee did not pass, so I wound up at the Naval Academy. Sort of a long shot!

Q: How interesting. Tell me about your impressions of the Academy and the life there.

Adm. H.: Well, I was somewhat prepared for it because, although I had not given it any thought as being something in my life, at the time this alternate appointment came out of the blue, I had developed a very strong interest in the Navy, as most of my contemporaries did on account of the campaigns of 1898.In those days, boys, at least in my area, in my town, there were boys who collected pictures of warships the way people collect stamps. I had a warship collection when I was twelve

Hustvedt #1 - 12

years old, during the Spanish. War, and I wasn't the only one in my neighborhood or in my school. It was a fad. So going to the Naval Academy appealed to me when it was put up

Q: Did you find the intellectual life at the Academy somewhat different from Luther College?

Adm. H.: The courses of study, of course, were far different. I had rather an inadequate background in math, because in shifting from a public high school to the Luther College prep department, I missed a certain amount of algebra, because the college boys went a little faster in algebra in the prep department than we did in the high school. So when I became a prep at Luther I was ready for the final year of the prep department but there was a gap in my math in the algebra section. Well, that plagued me a little, but I got over it. Of course, at the Naval Academy our algebra consisted of about an initial month of polishing in plebe class and we went on to other things.

Q: But other than that, in other things your training at Luther College was very helpful to you, I would imagine, was it not?

Adm. H.: Oh., yes. As a consequence of that training and I suppose as a consequence of my own interests - I'd like to get this absolutely correct - I think that I stood one in

Hustvedt #1 - 13

English in my class as a plebe every month but one. That was a direct consequence of my classical education at Luther and my own interest in reading. With regard to the courses at the Naval Academy otherwise, if you're interested in my reactions -

Q: Yes.

Adm. H.: I naturally found that I was handicapped to a certain degree by the gaps in my math, but that was left behind as soon as the first review of algebra was completed and we went on to other courses in mathematics. I possibly suffered in my appreciation of mathematics on account of the gap all the way through, because I never stood high in maths during my first couple of years at the Academy when we had mathematics as a subject per se. Geometry and trigonometry gave me no trouble. I had had them at Luther and understood them pretty well, but I suppose I would be obliged to say that my aptitude for math was not of the highest. That's about the best characterization that I can put on it. On the other hand, my preparation in the classics led more or less naturally to my standing very high in English and French.

Q: French was the required language?

Adm. H.: Well, I'd never had French in college but I presume my study of languages at Luther., including the reading of

Hustvedt #1 - 14

German, of Latin, of Greek, all contributed. I had a little handicap in math, I think, but no handicap elsewhere.

Q: I imagine you had one great asset in that you knew how to study?

Adm. H.: Yes, I think I did. I think I knew how to make use of my study periods.

Q: How did you react to the drills and the routine and the regimentation of life?

Adm. H.: The regimentation didn't bother me in the least. I was accustomed not to regimentation but to orders in my youth.

Q: And discipline?

Adm. H.: Discipline, yes. I think I pretty well knew how to study. I know that I was ready and willing to conform to regulations. They didn't irk me in the least.

Q: Were there summer cruises in those days?

Adm. H.: Oh, yes.

Q: Tell me about them.

Adm. H.: Let me tell you about my first cruise. My first cruise was in the brig Boxer - a hermaphrodite brig actually. The Boxer was a little ship that had been built for the Navy

Hustvedt #1 - 15

primarily for training purposes and I think in that respect she was rather an innovation because midshipmen, prior to the advent of the Boxer, I think had gotten their training so far as sail is concerned in the small boats at the Naval Academy and in the Hartford, which. was a full rigger. But during my plebe summer the Boxer became available for the first time and the new fourth class was taken to sea on Chesapeake Bay in four sections, and taken to sea for a week at a time. On the Boxer we were really trained as far as the time permitted in being sailormen because our drills were entirely connected with making sail, shortening sail, furling, and that sort of thing, and we were at it more or less all day long for the week we were out. We learned during that week what it meant to swing a hammock, we learned what it meant to have a ration of water because we were given one stroke of the hand pump in our little tin basins for our toilet in the morning, apart from that we got no fresh water except what we could drink at the scuttle butt. I have sometimes joked since about my introduction to the sea in that in the space of a month I went from the farm to being captain of the foretop learning how to handle the reef. oaring. I was actually captain of the foretop during .my week. in the Boxer. I suppose perhaps I looked a little huskier than some of my classmates! I was a well-grown boy of nineteen at that time.

Q: How large was your class?

Hustvedt #1 - 16

Adm. H.: We graduated 173. I can remember that figure. I think the number that were credited with entering in my class was something like 245, but I remember distinctly that 173 were graduated.

Q: So you had one week's cruise at least for your plebe summer?

Adm. H.: Yes.

Q: And the rest of the summer was spent - ?

Adm. H.: The rest of the summer was right there at the Academy. The cruise didn't take us any farther to sea than to Solomons! I remember that we went that far, and I think Solomons was the one place where we had anything that approached liberty. It wasn't a liberty it was just a chance to stretch our legs ashore for an afternoon.

Q: Tell me about the following cruises, the much more elaborate cruises.

Adm. H.: Well, my first real cruise was what we used to call youngster cruise, which came between plebe and youngster years, and that was you might say a humdinger for the time, because for the first time in quite a while, I believe, we saw some foreign ports. I was assigned for that cruise to the Des Moines, which was a so-called protected cruiser of that era.

Hustvedt #1 - 17

Q: "Protected cruiser," what does that indicate?

Adm. H.: That means she had a certain amount of armor here and there. The captain of the Des Moines at that time was Captain Halsey, Bill Halsey's father, who was highly respected by all of us, apart from the fact that he was our skipper. The executive officer was named Cooper. I could practically give you the roster of officers there, but I might miss one or more so I think I'd better let that lie. The highlight of that cruise was that we sailed from Annapolis directly for Funchal, Madeira, and that was the first approach to a foreign cruise that midshipmen had in some years, I believe.

Q: What a delightful port to chooses!

Adm. H.: Yes, Funchal is a wonderful place. Have you been there?

Q: Yes.

Adm. H.: Funchal was my first foreign port. I was there again on a cruise in the Bergensfjord three or four years ago and I found Funchal unchanged in some respects but very greatly changed in others. When we were there as midshipmen, the ship was constantly surrounded by small shore boats in which there were small boys who were constantly shouting 'heave I dive, heave I dive, heave five cents in the water, small bay my brother he dive." We had them all day long -"heave I dive!"

Hustvedt #1 - 18

I needn't describe Funchal. Of course, Funchal is exotic even now.

Q. Where else did you go?

Adm. H.: Our next port was Horta in the Azores. have you been to Horta?

Q: I've been to the Azores but not to aorta.

Adm. H.: Horta is not frequently visited, I think, but it was interesting. I remember getting ashore there once and taking a longish. walk, seeing what the countryside looked like. Of course, Horta was a very small place in those days. Interesting, of course, at aorta was the fact that from there could see Pico, the volcanic island of the Azores. It was a piece of our landscape there at aorta because Pico was very distinctly in sight from Horta. Oh, incidentally, I think I have not mentioned that between Chesapeake Bay and Funchal we had heavy weather practically all the way, and I mean heavy. Nearly all the midshipmen were out of commission. I can remember one supper when the midshipmen's mess had gotten down to the point of swinging one table. The tables in those days were hung from the hammock billets, and they swung. Swinging one table and putting food on the table and letting the midshipmen grab what they could as it swung, and I think there were not more than half a dozen of us at the meal at that particular time.

Hustvedt #1 - 19

Q: I take it then, that you neglected the coaling of the skip?

Adm. H.: Coaling, of course, we. participated in. We participated in it during all our summer cruises- I happened to be assigned to the lookout detail during the first week of that cruise, and the lookout detail - I think it was a watch in four - but the lookout actually made his way to the crow's nest on the foremast and that's where he stood his lookout watch. I think that I was the only one on that lookout detail that wasn't actively seasick at some time or other. So my introduction to going to sea was pretty rugged there in the Des Moines and convinced me that I need never worry about being seasick.

Q: Did it help convince you that you really wanted to be a sailor?

Adm. H.: Well, it helped to convince me that seasickness was never going to be one of the handicaps!.

Q: This cruise didn't take you to the continent of Europe?

Adm. H.: No, not at all, and I don't remember any particular grousing about it, but I do remember my own feeling of appointment that we. should have crossed the Atlantic and merely seen Funchal and aorta, because you're almost across the Atlantic when you get to Madeira and the Azores, as you

Hustvedt #1 - 20

know.

Q: Yes, but this was Columbus's route, wasn't it?

Adm. H.: Almost. I would say almost the reverse of Columbus. From the Azores we came back to the coast of Maine, Bar Harbor. I don't think we went to Bath on that cruise. We went to Bar Harbor, which of course is very interesting, and I think from Bar Harbor to Boston. At Boston on a Sunday I saw my first big league baseball game, and one of my recollections of Boston at that time was seeing one of the first large electric advertising signs I'd ever seen and it advertised Buick! Automobiles weren't very numerous in those days.

Q: No.

Adm. H.: Then, from Boston we went to Newport and New London and then went on back to Chesapeake Bay and our home port of Annapolis.

Q: Were you required to do any formal studying while you were on the cruiser?

Adm. H.: No.

Q: You didn't have any of the professors with you?

Adm. H.: I'm sure we did not on the Des Moines on my youngster cruise. We did on the Olympia on my first class cruise.

Hustvedt #1 - 21

My class didn't take a second class cruise I think the reason for that was that the Navy Department was finding it difficult to scrape up suitable ships at that time. That was the year of the Exposition at Hampton Roads and a good deal of what the Navy had available that summer in addition to the active fleet I think went into Exposition matters.

Q: So what did you do with your summer?

Adm. H.: Well, the new second class was divided into two sections that summer, and one section went on leave while the other section stayed at the Academy and more or less participated in the indoctrination of the new plebe class, in addition to having our own exercises. So we had two months' leave that summer and two months at the Academy, in two different sections.

Q: Did you go home on your leave? Did you go back to Chicago?

Adm. H.: Yes, I went home to Decorah , Iowa on that leave and also on the other, what we used to call September leave, I guess the still do. I think I haven't mentioned that my plebe summer I became one of what was known as the typhoid squad. Have you ever heard of that typhoid epidemic?

Q: No. Tell me about that.

Adm. H.: Well, that was the summer of 1905 and, as I remember

Hustvedt #1 - 22

it, the typhoid began in late July and I was one of the plebes who were taken with it about the middle of August. I was in the sick bay for about a month and then sent on leave for about a month to recuperate. The upper classmen, # think, were given an extra week of September leave on account of that typhoid epidemic, and I myself got back to the Academy about the middle of October. In the meantime had missed half the summer of instruction in French and I think about a month or more of instruction in mechanical didn't know how to fill a right line pen when I came back from that leave, and my classmates already had month or more of mechanical drawing under their belts. The consequence of that was that I was almost unsatisfactory in mechanical drawing for several months.

Q: Were many of the boys afflicted with typhoid?

Adm. H.: Not more than, I would say, somewhere in between six and ten. I remember that there were one or two - two I think, who on account of their timing or on account of the severity of their cases missed so much of the academic year that they were forthwith turned back into the next class, told to go home and come back next June. Luckily I escaped

Q: Was there a typhoid carrier there, or how did it originate?

Adm. H.: My own guess is that it originated through our having

Hustvedt #1 - 23

swimming lessons off the Santee wharf after we had qualified in the little indoor pool. Swimming was on the schedule as a regular drill and after a plebe qualified in the little pool he joined the swimmers and he swam off the Santee wharf. That was a summer of typhoid epidemics pretty well around the country, at least in the East. I remember there was a very serious one at Jamestown, New York, that summer, and there were various places where typhoid was rampant in that summer of 1905.Incidentally, there was a certain amount of typhoid the following summer and several cases at the Academy, including one of the Japanese midshipmen, who died in the summer of 1906.

Q: Tell me about the first class cruise, the Olympia.

Adm. H.: It was entirely what we used to call a crab cruise. In other words, up the East Coast and back down again. I don’t remember thoroughly in just what order we took our ports during that first class cruise, but New London, of course, was always one of the summer cruise stops.

Q: That was to visit the submarine base?

Adm. H.: Not primarily in those days. The submarine base at New London was actually a later development than that. I'm not even certain that we had submarines based in New London in those days. Some of the early submarines were based in Annapolis. My memory is a little hazy there, but I do not

Hustvedt #1 - 24

remember a submarine base at New London in the summer of 1908.That summer cruise I don't think included Bar Harbor but it included Bath, Maine, where we took part in some kind of centennial celebration. I don't remember whether it was a bicentennial or more, probably not more than a bicentennial. We visited shipyards. We visited the shipyard at Fall River, as I remember, and of course the Bath Iron Works was going fairly strong at that time. We spent a considerable time in the bays at the east end of Long Island, Gardiner's Bay and that area

Q: What would be the purpose of that?

Adm. H.: An exercise area where we could man the boats, row, and sail, and so on. I remember that that summer of 1908 was the first one that I can remember when motorboats began to proliferate.

Q: In Long Island Sound or where?

Adm. H.: No, not in Long Island Sound, in the ports like New London, for instance, and Bath.

Q: After this cruise, the last cruise, had you pretty much. decided what direction you were going to take in the Navy?

Adm. H.: Well, of course, I presumed that I was headed for being a line officer. I hadn't developed any strong inclination or special aptitude toward engineering. Of course, at that time,

Hustvedt #1 - 25

the old Engineer Corps in the Navy was fading out and, as midshipmen, we didn't necessarily look forward to a choice between line duty and engineering duty. We were all going to be line officers, as far as we knew. Some might develop special aptitudes as engineers. Of course, in our summer cruises when we were on ships with engineering plants we stood engineering watches in our turn.

Q: What about ordnance, did that interest you?

Adm. H.: Not as a specialty. I afterwards had a postgraduate course in ordnance, but that was in later years.

Q: Tell me about your first assignment, then. Were you commissioned immediately upon graduation?

Adm. H.: We were the last class that served a full two years as passed midshipmen and, as a consequence, I think it's fair to say that we have rather suffered ever since in promotion, relatively. And in the matter of promotions, I think it's rather an irony that it even extended to the wartime promotions that came along in World War II.

Q: Oh, really. They were affected by that?

Adm. H.: Well, in this respect, that World War II brought about a flood of promotions, naturally. My class was the last class to undergo a selection process prior to World War II. As a matter of fact, I was the last individual to be

Hustvedt #1 - 26

selected for flag rank up to World War II, I was the last one.

Q: That's an interesting point.

Adm. H.: I was selected in the summer of 1941 and I was the last one on the list.

Q: when you graduated you went on the West Virginia as your first assignment. Tell me about that.

Adm. H.: The West Virginia was one of the class of armored cruisers that was built around the turn of the century. There were about a dozen of them built, and they were regarded as capital ships and were named after states. The West Virginia was one of them. She was the flagship of, I think it was called, the-Second Division of the Armored Cruiser Squadron, which was doing duty in the Pacific at the time I was graduated. On the West Virginia my first duty was as assistant navigator, and during the first year that I was aboard and while I was assistant navigator we made a cruise from the West Coast to the Orient, which of course was a very interesting thing for us. We spent about a month in Hawaii on the way, not in port because we did a certain amount of exercise at sea during that month. One very interesting feature of that cruise the Orient was that after we left Hawaii our first stop, which was a refueling stop, was in the Admiralty Islands, The

Hustvedt #1 - 27

Admiralty Islands in those days were just one remove from savagery. The anchorage that we used was in Narles Harbor, which is a very fine harbor several miles off the north coast of the main Admiralty island and is a harbor that was used during World War II as one of the steppingstones in moving from the Solomons on up through the Marianas and Carolinas, the Marshalls, and all of those island.. groups. The base at Naries Harbor was used during that advance and certainly was far different then from what it was when I first visited there in 1909.In 1909 the only inhabitants other than savages in that immediate vicinity, as far as I know, were a German trader who had a small establishment where he dealt with the natives largely for coconuts, I think. The natives, the men, dressed with only a g-string plus armlets, anklets, but they were pipe-smokers and carried their tobacco or whatever it was they smoked in gourds, stuck their pipes when they were not in use through their armlets, and were thoroughly savage. I was detailed as a member of a survey party. Each of the ships sent out a boat to run a boat survey there in Naries Harbor, which is a considerable expanse of water with a number of islands in it

Q: Was this for the Hydrographic Office?

Adm. H.: Yes, that was for the purpose of developing the area

Hustvedt #1 - 28

more than the issued charts of that time because the issued charts of that time were rather sketchy down in that part of the world.

Q: So you may have contributed to the Navy's effort in World War II at that particular moment?

Adm. H.: As it so happened, when I left the fleet out in the Pacific in 1944 with orders to Washington for assignment to another command, my route led through. Naries Harbor in the Admiralty Islands. I actually left the ship almost up in the Marianas area - the name of the particular atoll escapes me now- and I went by plane from there to Pearl Harbor byway of the Admiralties and I landed by plane in the Admiralties and was held there over a Sunday. I got in there on Saturday and was held over Sunday and left on Monday morning. During the Sunday I was asked whether I would like to go with a boat that was visiting one of the temporary outfits ashore, which happened to be a radio outfit, on one of the islets. Well, I accepted that with great pleasure I found that I was visiting the islet where, during my Midshipman days, we had made a boat survey of Naries Harbor, the very islet where we had stopped to anchor and have our luncheon during those boat survey days. So I was landed almost exactly on the place where I had landed in 1909, but the appearance of the natives was a, little different. They had become a little bit civilized in the close to forty years.

Hustvedt #1 - 29

Everything else was just as it had been forty years before. Incidentally, when we first started on that boat survey, the boat that 1 was in, which of course was the boat from my ship the West Virginia, cruised along the shore of one of the islets there looking for a place that would serve as an anchorage, which we found, but before we got to it we had attracted a flock of native man who came down to the shore as close as they could get to us. We were easing along at, I suppose, somewhere around 6 or 8, maybe 10, knots, looking, and all of a sudden this group of natives let go with a flock of spears: It was only a gesture, but it didn't look very inviting at the time. Their range, I think, was about halfway out to our boat, so it was only a gesture of some sort. But after we landed in the little inlet that we used as a base from there on, the natives swam out, came out in their little boats, and gathered around at a respectful distance. Of course, we couldn't communicate with them, except by signs. We chose to anchor there for our luncheon and a consider-able part of our luncheon was a big can of corned beef that had to be opened with a key. It was a big can and the key was about that long. Well, when we departed we left whatever there was in the way of scraps, including the can and the key and the rest of it. When we anchored there for our luncheon the next day, one of the first of the natives we caught sight of had taken the skewer out of his nose and was

Hustvedt #1 - 30

wearing that corned beef key through his nose! I suppose he was the dandy of the neighborhood, with an iron spike in his nose instead of a wooden one! Well, we're straying.

Q: Did the Navy maintain units of the fleet in the Far East in those days? Or were these just voyages out?

Adm. H.: Yes, there was an Asiatic Pacific Fleet in those days, but doubt whether they ever got down to the Admiralty Islands. That’s a far cry from Manila or Hong Kong or Shanghai or Yokohama. Well, we went on from the Admiralty Islands to Manila and were in the Philippines for several weeks. I remember one circumstance of our stay there at Manila. We saw ship depart from Manila for the West Coast that was carrying the first load of duty-free Philippine cigars to the U.S., and that was quite an occasion. It made a great deal of difference, I believe, to the economy of the Philippine’s actually, to be able to ship cigars to the States without paying duty on them. I remember seeing that. A good part of our stay in the Philippines was at Olongapo, Subic Bay, where we based for docking in the old floating dry dock. Dewey, which was based at Olongopo in those days, and we also get ready for and fired a long-range battle practice there. From the Philippines the fleet broke up pairs - there were eight of us armored cruisers, they

Hustvedt #1 - 31

broke up into pairs for visiting ports. The ship that I was on the West Virginia of that day, went to Hong Kong. The West and Pennsylvania were paired, as I remember it, and we went to Kong Kong.

Q: To show the flag?

Adm. H.: Yes, and to give liberty, I suppose, after having been out of civilization for a month or so. We were in Hong Kong I think for about ten days, maybe two weeks. These are a couple of things I remember about Hong Kong in addition to the things that any tourist visitor will see in Hong Kong. One was the fact that there was a pair of German cruisers there at the time we were there and they were the Scharnhorst and the Gaeisenau.

Q: Oh, really, of that day!

Adm. H.: Of that day. We exchanged visits of courtesy with the Germans. Of course, the topsiders had their official exchange of calls, but I remember that we had a wardroom calling committee that called on the Germans and they came and called on us. Those were days when even the junior officers had a wine mess, you know. Another thing that was a landmark to me in Hong Kong was that I had an opportunity to visit Canton, to take a night boat up the river, spend a day in Canton, and take the

Hustvedt #1 - 32

night boat back. Canton in those days was a very interesting experience, of course. Well we moved on from Hong Kong to Nagasaki, incidentally encountering the tail end of a typhoon on the way with very heavy weather. I don't remember any-thing very special about that passage to Nagasaki, except that I do remember during the heavy weather relieving my immediate predecessor as junior officer of the deck, who was Richmond K. Turner, afterwards known in the South Pacific as “Terrible Turner"! You're familiar with Terrible Turner and Howling Mad Smith, of course?

Q: OH, yes. Kelly Turner.

Adm. H.: Kelly Turner. I relieved Kelly Turner on the bridge on an afternoon that I remember very distinctly in that heavy weather.

Q: I'd like to ask you about weather forecasting in the fleet in those days?

Adm. H.: I don't remember any such. thing as a fleet meteorologist or a fleet forecasting group of any kind, and, of course, radio communication was just in its infancy at that time. We had radio in the armored cruisers, but I don't remember that there was any system of weather forecasting or communicating weather forecasts by radio in those days.

Q: So you weren't forewarned about the typhoon, were you?

Hustvedt #1 - 33

You just came upon it?

Adm. H.: As far as I know. Of course, we had whatever knowledge of weather we had acquired in the law of storms, but we had nothing like radio forecasts, I'm quite sure. I think radio was too much in its infancy at that time to have developed a network of radio forecasts. Radio was pretty new in 1909. I think I can remember that even the roentgen ray became known in the early 1890s, at least it came to my consciousness in the early 90s. I had never heard of such a thing as an x ray until I was, perhaps, 10years old. Roentgen had been making his experiments and discoveries possibly before the 90s but I think the x ray came to popular attention actually about the mid90s, and radio communication later than that.

Q: Was the West Virginia joining units of the fleet out there? Did we have an admiral out there in the Far East?

Adm. H.: In the armored cruisers of that day we had two admirals. There were two divisions. I can't recall for certain, but I think not - I don't think there was a commander-in-chief, Pacific Fleet, at that time. I think there was commander-in-chief, Asiatic, but I don't think there was a commander-in-chief, Pacific Fleet.

Q: Had you gone out, then, to join the Asiatic Fleet?

Adm. H: No, we. we’re making a swing. I think you might

Hustvedt #1 - 34

say we were probably showing the flag in the Orient because we visited Manila as a fleet, we were at Olongopo as a fleet. Then we broke up into pairs, which would be four pairs. One pair, the one I was in, went to Hong Kong, Nagasaki, Tokyo Bay, Yokohama for Tokyo. One went to Shanghai. I've forgotten exactly where the Christmas holidays came in. I think they found us all in Tokyo Bay, but in the meantime ships in pairs had visited different ports in the China-Japan area. Hong Kong, of course, was very much an international port in those days, more so than Nagasaki. Nagasaki was, of course, a much-used port of call but not nearly as inter-national in those days as Hong Kong or Shanghai. In Tokyo Bay, Yokohama, we were able to run up to Tokyo by rail for a day's visit.

Q: How were you received by the Japanese Navy?

Adm. H.: I don't remember anything much in the way of communication. I suppose there must have been official calls. I don't recall anything about that stop in Yokohama, except that there was a football game at one of the lovely parks in Yokohama between teams from the West Virginia and Pennsylvania. I don't remember whether that was a New Year's. Day game or something of that sort. I think it possibly was on New Year's Day. Incidentally, the Pennsylvania won that game I think6 to 0 over the West Virginia team, which was coached by me.

Hustvedt #1 - 35

As you can imagine, there hadn't been much time for any organization of practice during our visits to the Admiralty Islands and the Philippines, and so on and so forth. This football game was pulled off more for the purpose of just having a game because I think the only practices that we could get in were during our stay of ten days or so in Nagasaki.

Q: How important were athletics to the fleet units at that time?

Adm. H.: There was a great deal of interest in athletics, particularly in boat racing and the fleet baseball encounters in-the Pacific Fleet of that time. They really were of great interest to the men in the crews. The baseball games used to attract crowds, mostly of the ships' personnel, of course, the two ships that were engaged. Well, we were at Yokohama for Christmas and visited Tokyo , and then we headed back home. We stopped in Hawaii just long enough to refuel, as I remember it, probably not more than four or five days, and then on back home on the West Coast.

Q: Let me ask what were the facilities in the Hawaiian Islands at that time?

Adm. H: There was a coaling station. There was a naval station. in Hawaii at that time. The facilities didn't amount

Hustvedt #1 - 36

to very much. There was access to a marine railway and there was coal. I don't suppose that oil was really a factor because none of us burned oil. Pearl Harbor had not been developed.

Q: Were there any repair facilities?

Adm. H.: Well, as I say, there was a marine railway that I think in those days could accommodate a destroyer. The iron works I think must have been keeping a certain amount of capacity for repairing ships because they had a great many steamships coming in to Honolulu in those days. Pearl Harbor, at that time, was undeveloped. Back on the West Coast we went about our usual business. Of course, we were in those days having a schedule of target practices, both short range and long range, and night. One of the notable events that some of us took part in as witnesses - the West Virginia, to which I was attached, and the Pennsylvania, plus I think other ships of the armored cruiser squadron, though I can't recall how many, were in San Francisco Harbor when Eugene Ely made the first landing of an airplane aboard a ship. I needn't go into describing that because that has been covered very fully here and there, but the West Virginia was anchored within 500 yards of the Pennsylvania, on which the landing took place, so, of course, we on the West Virginia in effect had grandstand seats for that event. I won't attempt to describe it. As I say, it's

Hustvedt #1 - 37

well known, the techniques that were used for arresting, the runway, but I don't remember seeing it mentioned, or, at least, stressed is that when Ely took off from the Pennsylvania on that day his wheels, his landing gear, almost touched the water before he was airborne. It was a very, very close thing, his getting off for his return flight instead of splashing.

Q: What about the landing itself, that must have been a hair-raiser, too?

Adm. H.: It was done so quickly. He came in from a field south of San Francisco, flying at about 1,000 or 1,200 feet, and he went on up over the ships of the fleet that were anchored near the San Francisco landing and on up to the neighborhood of Goat Island, where he turned around and came back down. During that return he was losing altitude and he came down past the ships again until he was at a fairly low altitude off south San Francisco, somewhere in the Hunter's Point area perhaps, when he turned and came up fairly low and approached his landing. All I can say is that he made what we're all accustomed to seeing as a normal loss of altitude and the touch-down, except that he touched down on the platform, and of course the crude arresting gear did what was hoped for and stopped him before he hit anything except the deck. But taking off he had an awfully short run in the space of the distance between the mother cruiser's

Hustvedt #1 - 38

mainmast and her stern. That's a run of certainly not more than a couple of hundred feet. And his drop-off at the deck I suppose was of the order of 15 feet or so, and his wheels almost touched the water before he was up to speed enough, to be really airborne. It was a very thrilling thing to see.

Q: Did aviation at that point intrigue you?

Adm. H.: Not actively, no. I've never had any particular pull toward aviation. I have taken the controls of a plane, a dual-control plane, a few times on flights between here and Dahlgren, Virginia, flights when I was going down to Dahlgren in connection with ordnance tests when I was with the Bureau of Ordnance. I sometimes went down by plane and the plane would normally be a two-seater seaplane supplied by Naval Air Station, Anacostia. On one of those flights after I'd been with that particular pilot back and forth to Dahlgren several times, he took off from Anacostia one time and went up to about 1,000 feet, leveled off, and about the time he passed Mount Vernon he gave me a nudge and he took both hands off the controls. Well, I'd been around often enough to know what he meant by that so r took over the controls and I flew the plane, roughly from Mount Vernon down to Dahlgren. He took over as we approached Dahlgren and landed the plane - it was a seaplane - and the proving ground people had a boat out there to fetch us

Hustvedt #1 - 39

ashore and no sooner had we stepped ashore than one of the officers attached to the proving ground said to us, "Who was at the controls when you came around Mathias Point? “I said, proudly; I was." He said, "I knew. it."!

Q: An amateur up there! Well, going back to the West Virginia, your tour brought you back to San Francisco Bay, and then what?

Adm. H.: That landing on the Pennsylvania by Eugene Ely was within a matter of weeks after we got back to the West Coast and the next thing I can remember particularly about maydays in the armored cruiser squadron on the West Coast was the fact that I was still attached when my examinations for ensign came up in the spring of 1911. I'm a passed midshipman all this time, you understand. But before those examinations came up the armored cruisers of the Pacific Fleet were ordered to base on San Diego. That was because of the fact that the Revolution in Mexico was still going on at a lively pace and there were revolutionaries as close to us as the city of Tijuana. As a matter of fact, during the period that we were based on San Diego there was a battle of sorts at Tijuana between government forces and insurgents and we happened to be aware in the fleet that we had certain men who had become absent without leave, some of them perhaps even become deserters, technically, who had joined the insurgents down in Tijuana.

Hustvedt #1 - 40

Well, an engagement of sorts took place at Tijuana that spring and the government forces took possession of Tijuana and they also took some prisoners, and an arrangement was made for officers from individual units of the fleet to go down there in a group at an appointed time to see whether any of these prisoners could be identified as being over leave from ships of the fleet. I was designated to represent the West Virginia in that little expedition because I knew the crew pretty well, having by that time been on the ship nearly two years and having done a great deal of duty as junior officer of the deck and officer of the deck and checked in liberty parties and so on. So I knew the ship's crew pretty well. There were somewhere around600 of them. So I was sent down to pick out the West Virginia's share of the prisoner crop, which I did.

Q: Had they gone as adventurers, or what?

Adm. H.: Oh, yes. Something to get a kick out of. But one of them, as it so happened, and he's the only one I remember as an individual, was a bosuns mate, first class, who was known throughout the fleet because he was the well-known coxswain of the West Virginia's race boat crew and was a character. He was an old-timer and he was a first class bosuns mate, I think only because he had a tendency to get into trouble and therefore couldn't hang on to the rating of chief - he would have been a chief otherwise, I think.

Hustvedt #1 - 41

Anyhow, he was a first class bosuns mate and he was a Scandinavian. I don't know whether he was a Norwegian or a Dane, or even possibly a Swede, because his name was Huitfeldt. That could be a name from any of the Scandinavian countries, but it's more likely to be a Danish name I think than anything else. Anyhow, he was known throughout the fleet, but he wasn’t known as Huitfeldt, he was known as Vasco da Gama. That's the kind of character he was.

Q: Were these men incarcerated when you got them back?

Adm. H.: Oh, they were given courts martial and given punishment, probably loss of pay, and so forth.

Hustvedt #2 - 42

Interview No. 2 with Vice. Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt, U.S. Navy(Retired)Place: His residence in Washington, D.C. Date: Thursday afternoon, 6 December 1973 Subject: Biography By: John T. Mason, Jr.

Q: Last time, we got you back to the United States. Do you want to take up the story from that point, Sir?

Adm. H.: I believe I spoke before about the business of spending some months basing on Coronado and having recovered some of our deserters who had taken part in the Mexican revolution, didn't I?

Q: Yes, you did.

Adm. H.: Well, that takes us up to the time when I, together with my classmates, were taking our examinations for promotion to ensign. We were the last class to serve two full years as passed midshipmen.

Q: Was that a valid system, do you think?

Hustvedt #2 - 43

Adm. H.: I don't suppose that it actually did us any particular harm because we performed the duties that ensigns performed afterwards, we were in the junior officers' mess, as the ensigns were afterwards, and I believe that after that on major ships ensigns were quite accustomed to standing watches as junior officers, junior officer of the deck and junior officer of the watch, in the engine room, and that sort of thing. I don't think that the status of passed midshipmen was far different from the status of ensigns in later years of comparable experience. Of course, I can't say that with absolute authority, never having been an ensign under those conditions. I had the experience of two years at sea after graduation before I became an ensign. But so fares my later observation is concerned I think as passed midshipmen we performed practically the same type of duty that ensigns of comparable length of service did later on, but we didn't have the rank and we didn't have the pay.

Q: And that is terribly important! That was just an aside. So, what was your next duty?

Adm. H.: My next duty after leaving the West Virginia was that I was ordered to the old cruiser Raleigh, which was a unit of the then Pacific Reserve Fleet. The Raleigh was a veteran of the Battle of Manila Bay, incidentally, and, of course, when I went to her in 1912 the Battle of Manila Bay was only fourteen years prior to that, so she wasn't so much- '

Hustvedt #2 - 44

of a superannuated veteran as you might suppose. That lasted with me for about six months, and it was a very quiet sort of thing because for most of the time we were moored in the harbor at Bremerton and we got under way only one time that can remember - we got under way and proceeded to Seattle and took part in a civic annual celebration of those days which was known as the Potlatch. I think they have Potlatches to this day in Seattle. In connection with that movement to Seattle we also went up the sound as far as Bellingham and stayed in Bellingham a few days before returning to Bremerton. In the late summer of that year, 1912, I was ordered to postgraduate instruction in ordnance.

Q: May I ask you a question first about the Raleigh? You say she was a part of the Reserve Fleet. Did they maintain full crew on her as a reserve ship?

Adm. H.: No, she had a reduced crew and she had only five officers on board. The commanding officer was a senior lieutenant, there were two ensigns, and two warrant officers, one bosuns and one machinist. That was the entire complement Of officers, and the crew was a skeleton crew.

Q: But sufficient to take her down to -Adm. H: Oh., sufficient to get her under steam and to navigate her from Bremerton to Seattle and up to Bellingham and back again.

Hustvedt #2 - 45

Q: Did the Navy have the practice of mothballing ships in those days

Adm. H.: I think not, in the same sense that they mothball them nowadays. I think they were pretty well either in commission or in reduced commission, which was the category with our ships of the Pacific Reserve Fleet, or out of commission. I don't think we used the term "mothballing" at all.

Q: It was a kind of a limbo state that they were in - the Raleigh was in a limbo state?

Adm. H.: Not exactly because she was sufficiently manned and capable of getting under way. She was in reduced commission, you might say. I wouldn't call it "limbo" because she was able to operate and did operate to that extent during the six months I was on board.

Q: Yes. So you went to PG school?

Adm. H.: Yes. From there I went to postgraduate school as an ordnance student. My first assignment was to a one-year course largely in organic chemistry at George Washington University. This was supposed to be, for me, an introduction to becoming an "expert" in explosives, particularly in smokeless powders, but also in other explosives. I was at the George Washington University for a year

Hustvedt #2 - 46

and I was studying principally organic chemistry with a great deal of laboratory work.

Q: With the intention of getting a degree?

Adm. H.: Well, the degree was incidental to my year of postgraduate study there.

Q: I take it that the Navy at that point did not have a postgraduate school in Annapolis?

Adm. H.: The postgraduate school in Annapolis was just starting. Possibly you might say that it was in its first year. I think that so far as the ordnance postgraduates of that year were concerned, Fitzhugh Green and I were the only ones that were assigned to study in a civilian university. That's my recollection, but the postgraduate school at Annapolis had been started and it was based in the old Marine barracks across College Creek.

Q: Were there other ordnance men over there?

Adm. H.: The other ordnance men, as I recall it, were at Annapolis. I don't think any of them were assigned to study at a civilian college, other than Fitzhugh. Green and myself.

Q: How did that happen?

Adm. H.: I wouldn't be able to explain it. I. suppose they considered that the engineering postgraduates could be

Hustvedt #2 - 47

instructed at the Naval Academy. I know that in later years engineering postgraduate students were sent to universities or civilian colleges, but I don't think that had begun during the year that Fitzhugh Green and I were studying at George Washington. If it were so, I don't remember which of my classmates were assigned to colleges as students of engineering.

Q: As an ordnance man studying at George Washington University, you were also based at the Bureau of Ordnance?

Adm. H.: I was technically attached to the Bureau of Ordnance, yes.

Q: Did you have to report in there all the time?

Adm. H.: I didn't have to report regularly to the Bureau of Ordnance, no. I reported to the Chief of the Bureau when first arrived in Washington for that duty, but after that I had no schedule of checking in at the Bureau of Ordnance.

Q: What was the caliber of the courses at George Washington?

Adm. H.: The courses that I was taking were under the Department of Chemistry, of course, and the head of the Department of Chemistry at that time was probably the foremost authority in the country, of the time, in the chemistry of explosives. He was Dr. Charles E. Monroe, who was not only the head of the Chemistry Department at George Washington University but I think was a Vice President of the

Hustvedt #2 - 48

University, or had acme collateral duty of that kind. I think I'm safe in saying that Dr. Monroe at that time was the Number One expert in the country in the chemistry of explosives. That's why we were there.

Q: Yes. Did you select this area to pursue?

Adm. H.: No. I was assigned to that area. I had no special talent for chemistry. There were the two of us assigned, as I mentioned a few minutes ago. Fitzhugh Green later on and about the time we finished our courses at George Washington was ordered, I think through his own efforts, to duty with the North Polar Region Expedition that was starting, I think in 1913, under Donald McMillan.

Q: Well, Admiral, you spent two years in study at this point, did you not?

Adm. H.: Yes, but the second year was spent in studying on my own, so to speak, the operations of various industrial set-ups. First of all, after finishing my academic year at George Washington University, I was sent to the naval proving ground and powder factory at Indian Head, Maryland. Of course, that tied in directly with my having studied chemistry, particularly as related to explosives. The powder factory at Indian Head was the next natural stopping point. At Indian Head 1 had experience, not instruction because I was on my own practically, but opportunity to observe the

Hustvedt #2 - 49

manufacture of powder and also the operation of the proving ground itself, which at that time was located at Indian Head, Maryland, now at Dahlgren, Virginia. I was at Indian Head from June until the following April, with a small interlude of about a month when I relieved the naval inspector of ordnance at the Washington Steel and Ordnance Company while he was given a month's leave. After Indian Head I was sent to Pittsburg under the Naval Inspector of Ordnance at the Carnegie Steel Company, but I was there not so much to go into the manufacture of steel but spent most of my time at the Experimental Station of the Bureau of Mines, which was and I believe is located in Pittsburgh, and there, of course, I was primarily attached to the section of the Bureau of Mines' station which related to explosives used in mining. After that period in Pittsburgh I moved on - oh, incidentally, while I was attached to the office in Pittsburgh took my examination for promotion to lieutenant, junior grade. Prom Pittsburgh I moved to the Philadelphia area where I was attached to the office of the inspector of ordnance at the Midvale Steel Company. Again, I was not concerned so much with the steel-making as I was concerned with the operations of the Army's Frankford Arsenal, which had to do with small-arms explosives.

Q: This was what came later to be known as a Cook's Tour you

Hustvedt #2 - 50

were taking!

Adm. H.: While I was at Midvale I received my orders to sea, approximately upon completion of two years ashore, and was ordered to the USS Utah.

Q: Let me ask you a question about that tour of industry. Coming, as it did, on top of your year of intensive study at the University, this was in a sense implementation of what you learned in theory?

Adm. H.: Yes, I think it was intended to be, particularly of course the tour at the powder factory at Indian Headend also the tour connected with the Frankford Arsenal, where the Army was dealing with explosives to a certain degree. Also while I was at Pittsburgh I performed inspections for the inspector at the Simple Company in Sewickley, which was manufacturing fuses and related equipment for the Navy at that time.

Q: So indeed this was a very valuable educational process you had

Adm. H.: Yes, I was supposed to have a look at the application of explosives where they were manufactured or where they were applied to ordnance weapons.

Q: In retrospect, would you say that this was a great assistance to you in future years in your career?

Hustvedt #2 - 51

Adm. H.: I would say that my study and observation and experience during those postgraduate years were of use to me in familiarizing me with the explosive and pyrotechnic elements that the Navy uses - smokeless powder, pyrotechnics, primer materials, smoke-producing materials, and that sort of thing. Quite a wide range when one considers all the various facilities to which I was attached during that second year when I was not having formal education of University lectures and study. Does that answer the question?

Q: I think so, yes. Now, you were about to tell me you had been assigned to the Utah.

Adm. H.: Yes, I was ordered to the Utah and there I became a turret officer, a division officer with a turret and its crew. I don't know that there was anything really out of the ordinary about my cruise in the Utah. My experience was pretty much that of any ensign aboard a battleship, I think.

Q: War had broken out in Europe by that time?

Adm. H.: The war broke out in Europe about a month before I went to the Utah

Q: Did it have repercussions immediately in the fleet?

Adm. H.: I would not say that anything of that kind

Hustvedt #2 - 52

impressed itself upon me. Of course, I was not in the fleet at the time the war broke in Europe, which was in August. I joined the Utah rather late in September, as I remember it, so there was no immediately observable repercussion in the fleet.

Q: Did you find any concern, any feeling that we might get involved in this conflict?

Adm. H.: I don't think I did in 1914, no. I don't think the country did in 1914.

Q: No, but military people sometimes are more sensitive to these things than others.

Adm. H.: Yes, but I'm afraid that as a young officer attached to a battleship and with family responsibilities because I had been married for two and a half years at the time World War I came on, I don't think we really forecast during the early years of 1914 and 1915 that we would be involved in Europe. I doubt that it occurred to us right away.

Q: The Utah operated in the Atlantic?

Adm. H.: The Utah operated entirely in the. Atlantic during the years that I was in her, yes. During my couple of years in the Utah I was transferred from command of a turret division to a function which at that time was, I believe, new to the fleet, that of assistant fire-control

Hustvedt #2 - 53

officer which, in effect, was assistant gunnery officer. Practice of having an assistant fire-control officer in a batt: ship I think was instituted somewhere about 1915 or 1916,and that's what I became in the Utah, assistant fire-control officer.

Q: The need for this function had become apparent?

Adm. H.: Yes. I think that was largely a result of the development that was taking place in what we call fire control. We were learning a certain amount of what the British were learning through their experience in the war in Europe beginning in 1914. By 1915 or 1916 we had learned to look upon gunnery, fleet gunnery, not only through the experience of our own service in prior years but also, in some degree, through the wartime experience of the British. Of course, that's a long story. The way it affected me was to switch me from a turret and division officer to that of assistant fire-control officer.

Q: I take it, then, the British were sharing some of their knowledge with us?

Adm. H.: Oh, yes. I couldn't say definitely, having been quite a young officer at that time, just what the extent of that sharing was nor what the channels were or the mechanics of sharing, but there is no doubt that we became acquainted with the developments in fire control and gunnery as a whole

Hustvedt #2 - 54

through the. British experience of those years prior to our own entry

Q: This new assignment must have added to your knowledge?

Adm. H.: Yes. Gunnery and fire control were very live topics in our fleet at that time. It was around that period that Admiral Sims made his presence felt, as we all know, in the improvement of naval gunnery. Gunnery was a very live topic in our fleet, there's no question about that, and to some extent, as I said, I think we shared the experience of the British even before we got into the war, just through what channels I wouldn't attempt to say because at the time I didn't know too much about it, being a relatively junior officer. I was a lieutenant practically through World War I.I was detached from the Utah in 1916 and ordered to the staff of the Division Commander, who was then Rear Admiral A. F. Fechteler.

Q: The father of William Fechteler?

Adm. H.: The father of Bill Fechteler, yes. I was ordered to his staff as flag secretary.

Q: He was battleships, too?

Adm. H.: Yes, he was the division commander of the division that I was in at the time in the Utah. The flagship at that

Hustvedt #2 - 55

time was the. Florida but within a matter of weeks almost through a relative movement of organization Admiral Fechteler transferred his flag to the New York, which_ was in another division and, of course, was a more modern ship than the Utah. I was with Admiral Fechteler in the New York at the time we began to be closer and closer to a break with Germany. At the time of the break with Germany I was still serving on Admiral Fechteler's staff and was just approaching my promotion to lieutenant commander.

Q: What was it like to serve as his flag secretary?

Adm. H.: Well, service as flag secretary is an education in the administration of the fleet. As flag secretary, it was my responsibility practically to prepare most of the correspondence related to official matters, schedules, et cetera. Of course, the Admiral indicated to me what he wanted but it was up to me to compose and phrase most of the correspondence and eventually present it to the Admiral for his signature, if he cared to sign it as was, or for amendment.

Q: All this done in longhand, too?

Adm. H.: Mostly, although I had two yeomen on my office staff who could take dictation, so a good bit of it was dictated. Some was in longhand before it was typed. Of course we had mimeographs in those days and methods of

Hustvedt #2 - 56

duplication but the text of important letters was often done in longhand by the Admiral himself or by me as flag secretary. Some of it was dictated. The Admiral used to dictate on occasion. I dictated on occasion. So it was some of this and some of that.

Q: A transitional time, wasn't it?

Adm. H.: I went to that duty in the spring of 1916 and in the spring of 1917 the war came on, and very shortly after that there was a shift in commands in the fleet. Admiral Fechteler was overdue for shore duty, as I remember it, and went to command at Norfolk. He was relieved by Rear-Admiral Thomas S. Rodgers, who was already a division commander in the fleet but by a certain amount of reorganization Admiral Rodgers came to be the division commander for whom I worked.

Q: And shortly thereafter you went to England, didn't you?

Adm. H.: No, it wasn't shortly exactly. I went with Admiral Rodgers I think in the early spring of 1917. I was with him from then on until late in 1918. I was still With Admiral Rodgers in 1918 when his division was sent overseas to join up with U.S. Naval Forces in Europe operating in conjunction with. the Grand Fleet but not in company with the Grand Fleet. The Grand Fleet was based at Scapa, as it had been throughout the war. Battleship Division Seven with, a somewhat reinforced division of destroyers was based on

Hustvedt #2 - 57

Bantry Bay in Ireland.

Q: What were the particular duties of Division Seven?

Adm. H.: I think Division Seven was based on Bantry Bay as a counter to a possible sortie of German battle cruisers to raid our transport lanes. That's about as concisely as I can express my idea of what we were doing. Of course, Bantry Bay was within easy distance of the lanes that were used in ferrying our troops and materials to Europe, to the Western Front. I recall that one time while we were there at Bantry Bay there was an alert of some kind which sent us out from Bantry Bay to meet with a troop convoy. Nothing out of the ordinary resulted from that. We picked up the convoying pretty thick weather and escorted them to somewhere within the English Channel before we turned them over to local escort. That was the only time that we actually sortied from Bantry Bay in a war movement.

Q: The German submarine menace was particularly great in the North Atlantic at that point, was it not?

Adm. H.: Oh, yes. This was in the late summer and early fall of 1918. The submarines were very active and, of course, I presume that there was also always a chance that the Germans might spring loose one of their battle cruisers to raid the transport lanes in the Atlantic. I think that was in the

Hustvedt #2 - 58

background of the thinking too at that time, and that was the reason that we had this division of battleships at Bantry Bay, perhaps more to act as a counter to the battle cruiser menace than anything else. It was not primarily as a counter to the submarines because a battleship is a poor agent to hunt down submarines.

Q: Yes, indeed.

Adm. H.: We were still there when the armistice came on. Incidentally, there are two things that I probably should mention there. During that time at Bantry Bay, in the early fall, late September, as I remember it, a deputation, for want of a better word, was sent from Admiral Rodgers' command to visit the American command operating with the British Grand Fleet out of Scapa. That was a sort of liaison visit so that Admiral Rodgers! command at Bantry Bay would be a little better informed about how things were done in the Grand Fleet with which he might join up at any time. That deputation consisted of Commander Ford Todd, then the executive officer of the Utah, of Gardner Cakey, who was the gunnery officer of the Oklahoma, of W. W. Wilson, who was the gunnery officer of the Nevada, and myself, who was still flag secretary to the admiral in command. We proceeded by rail from Bantry Bay to Dublin, then across to Holy head, in Wales, then by rail on to Crewe, where we waited for a night train to Edinburgh. We joined the Grand

Hustvedt #2 - 59

Fleet just a day or so before the Fleet sortied from the Firth of Forth for one of its sweeps in the North. Sea. Of course, the British battleships and our own battleship division there under Admiral Rodman were the last units to sortie from the Firth of Forth to form up outside and that led to our having a grandstand seat for the sortie. That was a most impressive sight, never to be forgotten. We were at sea for three days or so and we made no landfalls, but I understood that we had come within ten miles or so of the southwest coast of Norway during that sweep. At the conclusion of the sweep the entire fleet wound up at Scapa Flow, in the Orkneys.

Q: That was a sortie, was it also a kind of a baiting operation, hoping that the German ships could be enticed out?

Adm. H.: We had that general understanding, that the Grand Fleet made an occasional sortie and sweep of that sort in the North Sea, largely in the hope that the Germans might be enticed. We understood that that was the case, yes.

Q: And you were disappointed!

Adm. H.: Yea! Well, we certainly had no such eventuality. But the weather, as r remember it, was somewhat thick during Practically all of that particular sweep, but it was a very interesting thing, of course, to actually be at sea in the

Hustvedt #2 - 60