[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. ANDREW BEST April 28, 1999 Inteviewer: Ruth Moskop Trancribed by: Sabrina Coburn 12 Total Pages Copyight 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: Today is April28, 1999. My name is Ruth Moskop and I'm here in Dr. Andrew Best's office on Moyewood Drive in Greenville, North Carolina. Dr. Best, do I have your permission to record our interview?

AB: Yes, you do.

RM: Thank you so much.

AB: You're quite welcome.

RM: This is one in a long series of interviews that we've had. Every one of them I've enjoyed so much and there's an aspect of life that you've been wanting to talk to us about since the beginning. One of the things you said to me is that, "One cannot separate me from my religion."

AB: True.

RM: Can you expand on that a little bit; explain that and tell us what you mean by that. (0:47)

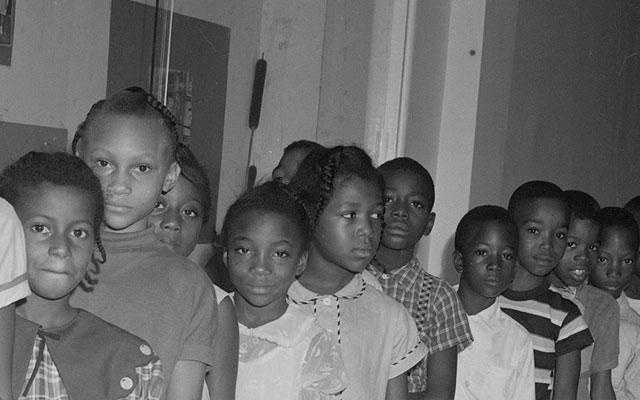

AB: I mean that I, as a personality, am deeply rooted in a religious fate or religious belifs. Those roots, I am sure, emanated from--came from seeds planted by the attiudes, training, and discipline of my parents. Of course, being a country boy and growing up in a neighborhood where all adult neighborhood leaders were, shall I say, mentors and supervisors of all of the neighbor children. That old expression we say, "It takes a village to raise a child" was certainly born out in the country neighborhood up in Lenoir County. The neighborhood was called Jericho on this side of Kinston, between Kinston and Greenville. Well, Jericho was predominately a black neighborhood where, following slavery, there was some black folk who became owners of a certain acreage of land in the area and all of Jericho is an area roughly about maybe three miles by five miles going along a stream, which was called the Jericho branch. That's how the neighborhood got its name. (3:13)

RM: The Jericho branch of which river?

AB: The Jericho branch. It was a stream and it emptied into Contentnea Creek. It was a little small stream, which actually emptied into the Neuse River down near the Fort Bonnell area, Sandhill. It was predominately a minority neighbor and maybe one or two whites lived on the fringes, but basically it was a minority neighborhood. As I was born and reared, I'm from a family of ten. There were six irls and four boys. I am boy number three in the family of boys and I am child number eight in the overall family of ten. Now, my father and my mother were very religious people. My father worked with youth and the Sunday school. We had a church in the neighborhood, which was AME Zion Church, and it was founded in 1902. So, from anything that I can remember, the church was there as a neighborhood institution. My father was the superintendent of the Sunday school for many, many years and after he passed on, my older brother-brother number two out of the four boys-became superintendent of the Sunday school. His tour of duty ran for more than fifty years. Well, I say that to give you a background that would shape some of my own beliefs and philosophies. There are a number of things from time to time that my father would stress that really mirrored his beliefs. One of his favorite biblical sayings was, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." He was very strict on enforcing that even within the family from brothers and sisters to our associations with the neighborhood kids and the Sunday school kids. On Sunday mornings, he didn't ask if you're going to Sunday school, he would remind you, "Hurry up, finish your bath, get ready. You're going to Sunday school. Sunday school is at 9:00." He believed in being on time. In his administration, you stayed in Sunday school for one hour. If there were two people there, he opened the Sunday school sesson and at the end of the hour, he was closing it just like in the later days, whatver you're doing just like on radio broadcasts, on television broadcast, when the old clock on the wall says that it is 11:00, you stop all of those 10:00 and 10:30 classes and programs and statements which were in progress. I joined church probably around 16 years of age and I grew up in a church with that sort of philosophy of living and letting live, which was one of my father's famous statements of activity and behavior in the community. Live and let live. I want to be just as kind to you as I want you to be kind to me. Now, it doesn't say as you have been to me. This is a case in point. There was a neighbor who-both of them, my father and this neighbor-were farming some rented land owned by a large landowner who was white, and this neighbor really got upset with my father, which was over nothing. He kind of was fussing and my father was just listening and when he got through fussing, he just turned and went on his way and didn't even try to rebuttal anything. Later on that afternoon, the neighbor had a problem with his wagon and it had broken down, the wheel went bad or something of that nature. Anyway, he came to my father and asked, "Brother Best, would you let me ue your wagon?" My father said, "Yeah. Go ahead." Even though he had fussd and had fumed in the morning over some little item that to my father, and to me as a young youngster, didn't even make sense. When he came back and needed a favor, my father went right along and turned his head just as if nothing had happened. He always would use incidents like that to say to the children, "Don't let somebody who does a bad deed be the initiation or be the spot that makes you do a bad deed." Now on Sunday mornings, as a child, there were two things that you knew would happen. At the breakfast table, all of the children gathered around the breakfast table and everybody would engage in the Lord's Prayer. We would say the prayer through and dad would nod his head to whichever one he chose to say the grace. We would say a very familiar grace, "Lord, make us true and thankful for what we are about to receive for the nourishment of our body. For Christ sake. Amen." With that kind of upbringing and spinning out from actually the home, there was my mother's oldest sister, who was a community leader, Aunt Sarah. Aunt Sarah could do just as much with any one of those 50 or 75 children in the neighborhood of all ages and their mothers and their fathers. The children were taught that you must obey and respect another adult person, period. For example, if mother would get the news thatAunt Sarah had been disobeyed, which was something of a rarity, Aunt Sarah had he authority to go ahead and give you the whooping that you deserved or she would just call my mother, who was named Cassie. She would say, "Cassie will give you the whooping. You are her child." Now if Aunt Sarah elected to give you a little spanking, you still got another one when you got home. This was the discipline that flowed as a neighborhood commodity and I'm sure that it was good, because it kept a lot of the children doing the right thing, developing the right attitudes. Now back to the church. As a community institution after joining church, coming up through Sunday school and joining the church, I joined the choir to make out the number. I never tried to advertise my ability to sing, and I used to say very often to people, "Now don't worry about my bad singing. I'm singng for me and not for you. I sing for the joy that I get out of singing." So, all of tose things kind of showcased what my attitude was, more or less in growing up. (13:27)

RM: At what age did you join the choir?

AB: I joined the choir probably about 17 or 18.

RM: That was an adult occupation, the choir?

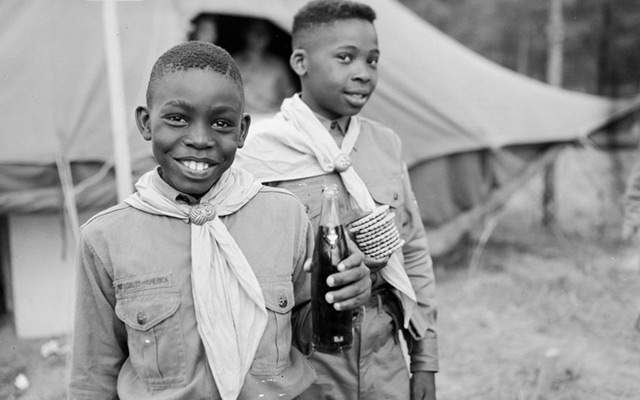

AB: Well, the first choir was organized kind of by my older brother, who had been studying some organ music. He had gotten to where he could play the various hymns. Nothing like a Duke Ellington on the instrument, but he could play the tunes. They played by notes and so that you could take the songbook and set it up on the piano or the organ and it was written. You could go through and get the tune and perform the selection. That first organ was what we called a windjammer. It was an organ that you had to pedal with your feet to have the bellows sending the air through so that the notes would have sound. It was a real great experience for the neighborhood kids who were under my older brother's tutelage, so far as the music was concerned. Now in growing up, say in the church, then from Sunday school to church, the 4H Club, which was a club with the farm kids out on the farm. The 4H thing, "I pledged my head to clearer thning. In my heart, to greater living. My hand's the greatest service in my community, my home, and my state." This was the traditional4H pledge. There was a black...Well, at that time the extension service was segregated. They had a black agent or what they called a colored agent and then they had a white agent for the whites. This gentleman, Mr. Peter Fuller, was a very kind gentleman, very knowledgeable, had a great way with kids, deep sense of humor, and he was no nonsense when it came to participation in community programs. You could always laugh or feel free, but when it came down to work and the actualities...In other words, we play hard and then we work hard. That used to be one of Mr. Fuller's expressions. That was still molding me as a person and as an individual. Well, from that point as I went to school...See, the neighborhood school in the country was an elementary school. I may have eluded in other interviews... (16:56)

RM: You did tell us about the schools.

AB: ...recorded where this church served for three years in the fifth, sixth, and seventh grades. I went to school in the neighborhood church.

RM: How many families would you say were in that Jericho neighborhood?

AB: Oh, in that neighborhood, there were at least maybe fifteen families, at least fifteen families. It might have been a few more and some of the families were large families with a lot of children just like my mother and father had. Others had small amounts. The average family in that context had at least 7 to 10 to 12 children in those families where we grew up.

RM: Do you remember how ...Was it common ...All ten children grew to adulthood in your family, didn't they?

AB: Say what now?

RM: Did all of your siblings reach adulthood?

AB: Oh, yeah.

RM: Was that the usual situation? (18:00)

AB: Yeah. That was the usual situation. See, now my oldest sister and my oldest brother, as I said I was child number eight in that family, and of course, my oldest sister married and went away to the north to Albany, New York. At 18, my oldest brother went north looking for employment and lived with my oldest sister for a while until he could get established. The family always had the attitude that promoted that we help each other and that we defend each other. We promoted each other and that was a very, very good thing. Now reaching a little further and getting to the heart of my own religious beliefs, I've always believed, even in high school and my relationships with people, the 4H Club kids or what not-I've alas believed in doing unto others as my father said, as I would want them to do unto me. I always had the aspect of fairness and flexibility as a part of me. Flexible enough to adapt to whatever it needed. If I had to sacrifice something to do you a favor if you were in need and this kind of thing. As I began to grow, I had a kind of deep feeling that this philosophy paid off and was very satisfying to me and it kept me from becoming bitter when I thought I had suffered an injustice. Like we talked about with the white kids saying, "There goes a nigger, a niger." While they were riding on the bus and I would get insulted because of my color. It never made me become bitter within itself. Of course, my belief in a Supreme Being was enhanced by a number of things which happened to me. Evenfrom high school, where my dad died in the summer in June between my junir and senior years in high school. My dad died when I was a late teenager at that time. A great deal of weight and responsibility fell on me and brother numbr two to safeguard the entrance of the family. Mother and other sisters who werethere...There were two children in the family below, child nine and child ten, who were too young to fend for themselves. A lot fell on us and we were very fortunate with some very hard, difficult work, but I have a belief that getting through those hard times had something to do with the man upstairs who was looking out for us and our faith. There's an old proverb, which says, "God helps him who helps himself." That was one of the French proverbs. Beyond all of that, I had the feeling that the Lord looks after fools and children and so, in other words, there is a Supreme Being and some other things that happen. In other words, the hard work and the difficulties that I had and I stayed out of school. After finishing high school, I was out of school for four years before I could recover enough to get myself together to even go to college. (22:51)

RM: The work that you did, was it there on the farm?

AB: On the farm and I did some public work like at the saw mills, which was very hard work and in the tobacco factories and what we call being hired out between what we did on the farm to have some cash income coming in. Then, as I went on from there to go into the service and this really brought home some things when I went off to the war. See, when I went off to the war, one of the first things that I felt had some divine intervention, was in Officer's Candidate School, where a sprained ankle and knee laid me up for a couple of weeks. In that fast moving pace of training in Officer's Candidate School, you can't afford to miss but so much before you are totally out of it. When an intensified 17 week period of training to become an officer and you miss two weeks...Well in my case, according to the protocol, they didn't kick me out, but they did what they call recycle me because coming out of the infirmary and getting ready to go back into training, the idea was well, you missed too much. So, we recycle. In that recycling, the material level was familiar and it made it much easier in that first five weeks. See, you put in five weeks, and then I get hurt, get laid up, and come back out of recycle... (25:08)

RM: Basically started you again.

AB: Yeah. Started again. Started again from day one in another class. Now, if you look at in one way, I just hate to have to go through all of that rigorous stuff all over again, but then what bought home some of my people and some of my acquaintances who were in that original class, went on through and the news...They got sent overseas. The news got back that some of those boys got chewed up by the Nazi war machine and were dead. I said, "There must have been some divine intervention here to save me from that kind of thing." (26:00)

RM: I guess the divine intervention caused you to hurt your knee and foot then.

AB: Yeah. Yeah. The hurting of the knee and foot was a blessing in disguise because I, too, could have been chewed up with some of the people of my acquaintance. Then in the war itself, I mentioned the incident with Captain Price and this discrimination thing, but fighting a war as an infantry soldier, there were many brushes with death, one of which is very vivid. My soldiers and I were up front dug in our holes and we learned to recognize a missile going out that was fired from one of our mortars or one of our guys back in the back, going out towards the enemy and one coming in. You could tell the difference. This missile... (27:07)

RM: By the sound of it?

AB: Yeah. By the sound of it and by the echo and the re-echo as it is going through the air. It's kind of like if you hear a jet plane, you know that there is a plane up there, but then when you look, if you look where you think the sound is coming from you'll miss it. If you look way down ahead, then you'll see it because it's going actually faster than sound. Anyway on this particular evening, the missile came crashing in and it landed right near where my platoon and I were, maybe about as close as from here to back there in the kitchen. In many instances, we had learned that the Germans would send those missiles in with a time-delay fuse. It might lie there ten minutes to half an hour and then suddenly explode and wipe everything within a certain radius. We were just waiting for that missile to explode, because it came in and plowed into the. In ten minutes, it hadn't exploded, twenty minutes, it hadn't exploded, half an hour, it hadn't exploded. We clled up the ammo experts. We called them ammunition experts and they discovered that the missile was a dud. It had a faulty fuse and it didn't explode. So, I said, and started shaking my head, "This is divine intervention." Other instances like that made me have a great respect for spirituality and for divine intervention and then there was another part of it, Ruth, and that is what do I enjoy? Is this my philosophical concept, my belief in the divine being? Is it a farce with me, something pseudo or false, or is there actual joy and comfort to me, in a comfort, in a satisfaction? That's where it all is. It is responsible for something that in my feeble efforts at poetry when people ask me about my respct for my roots. I'm thinking about the discipline at home, the going to schol in the old church building, and all of those things coming in to make me, to mold me into what I am. I often say in public utterances that I don't care where I've been or where the future goes. I'll always say with pride that I'm from Jericho. You see, that within itself works against people who leave and disown their beginnings as humble as they may be. I have seen it where people from let us say Comfort...Comfort is a very small community village in Jones County, not too far from Trenton, and this young man who would come to Kinston and stay with one of the relatives to go to school...See we didn't have buses and transportation for coming to school. People asked him where he was from. He said "Oh, I'm from Kinston." He didn't say, "Well, I'm from Comfort. I'm from downin the country." They denied their roots for some reason that I could never understand and those same folk might leave Kinston or North Carolina and leave the country and go to spend one summer in New York or Washington, DC or something. People would say, "Where are you from?" "Oh, I'm from New York." They even take a different kind of accent. We down here say "tomatoes", they say "tomatoes", "potatoes", "potatoes". Boston becomes "Boston". To me, people are being totally unrealistic. I don't understand that escape mechanism to try to escape one's beginnings no matter how humble they may be. (33:15)

RM: How does it work? Let's see, up through high school and after high school, you were very closely attached to the Jericho community and then you went away to college in Greensboro, and how did you take...?

AB: See then I went away after Greensboro, I went to the Army. I stayed gone for three and a half years, and that set up the interview with one of my professors where I came back from the service all frustrated and disgusted and all of that kind of thing. I had decided that I wasn't going to medical school, but after talking with him, I got back on the right track. But, I still maintained my relationship with the Jericho community and doing what I could in contributions there. (34:07)

RM: What did you do on Sundays when you were away from Jericho?

AB: Well, while I was in Greensboro, I attended church services there. See, my religious upbringing, I didn't go to college to forget about my religious upbringing. In college, even at A&T, I was a member of the Sunday school, I was the Assistant Superintendent of the Sunday school on the campus. All of that was maintained and even when I went to Meharry with the fast pace of the rigors of being a medical student, I still managed to keep in touch by going to one of the neighborhood churches and sometimes they would have religious services right across the street from the black university. I would go over there for Sunday schol and for church services, and we maintained our religious upbringing. Then as I got into the field of medicine and came back, one of the attracting features for me coming back to North Carolina was that my mother was living and she was stil here. (35:32)

RM: I see.

AB: So, instead of getting started and going to Kinston, my hometown, the county seat of the county where I born...instead of going there where the segregation of the hospital was a factor. The hospital was owned by a group of doctors. Then I cameto Greenville where the staff was open in the first place and I could be near enough to attend to some of the things like my mother and of course in 1972, a rebuilding campaign was launched for my church and...

RM: Your church in Jericho?

AB: In Jericho, where I maintained my membership and being a member, I was a member of the trustee board and I became Chairman of the Board. I was the really the architect of record in that rebuilding process. Of course, I had a young miniter who was the draftsman who would do the drawings for my approval after givig him the information that he needed like the dimensions of the building, what we're going to put here or there or what we need to include. I was the architect and fundraiser number one to try to get that $750,000 to complete that edifice. I was successful in that role of Chairman of Trustee Board of my church, which I still am. I don't know how much longer. (37:20)

RM: Is that building still standing?

AB: Yeah. The rebuilt building is very nice edifice. It's a brick church that we rebuilt in 1972 and we laid the cornerstone and had a dedication ceremony in July of '74. Purposefully, I delayed the cornerstoning and dedication while we were actually building up our financial reserve. So with the combination of those efforts, in July, we had a week of dedication. It was tied right into fundraising, which was an itentional thing. We raised enough money that we went on and paid off a 15- year mortgage, paid it off in 2 years, 11 months, and 17 days.

RM: Isn't that marvelous?

AB: Yes.

RM: What happened to the old church building, the one that served as a school? (38:29)

AB: Well, the old church building at first when it was first established was just a four cornered building, just one room, four comers. As the years past, we added on what we call a T that served for the pulpit and choir stand and of course, we had a foyer out in front, which we call a belfry. As we got ready to clear the space out for the new church, we took the belfry off, we took the T off, and we left the original square building, which was the sanctuary. We moved over on the lot and rebuilt it and remodeled it. It still stands there and with Bishop Shaw, we named it The Memorial Fellowship Hall and it still stands there on the property and serves as a community building as an extension to the dining room for whatever purpose. All of that is tied in with my religious contributions, my religious philosophy, and the community has really benefited from the handiwork. (39:56)

RM: Well, tell me some more about your current religious affiliations. You're still a member of the Jericho Church.

AB: Jericho AME Zion Church.

RM: But your official ties have broaden considerably.

AB: Yeah.

RM: Your official titles. You have all sorts of responsibilities in that church.

AB: Well you see, from the community we have... My church belongs to Wilson district, which is 22 churches headed by a presiding elder. I'm a member of the so-called Cape Fear Conference. Now our presiding bishop has four conferences in his Episcopal district. The eastern North Carolina Episcopal district has four confrences; the Alby Long Conference, the North Carolina Conference, the Cape Fear, and the Central North Carolina Conference. Well, I belong to the Cape Fear Conference and being an advocate and a very active churchman for the last...This is the 27th year that I have served as President of the Layman's CounciL See, by large the membership in Methodist churches, you have your ministry, all of the ministers and then all of the other members belong to what we call the laity. The laity in the Cape Fear Conference is headed by a friend of yours, named Andrew Best. (41:41)

RM: All right. Well, that keeps you busy going to meetings throughout the year.

AB: Oh, yes. Throughout the year.

RM: And you still attend church regularly on Sundays.

AB: Oh, yes.

RM: Do you do church service and Sunday school?

AB: Here lately, I haven't. My medical professional responsibilities has kind of kept me from being the Sunday school student that I would love to be and that I used to be. Every now and then, see our Sunday school goes from 9:45 until about 10:45, which we get out of the way for the 11:00 service. As often as I can, I will go early so I can get in on the tail end of Sunday school the day that I'm going to church. It kind of works out. I haven't lost all of my Sunday school upbringing and interests. (42:45)

RM: Is it an opportunity for you to be with your family and lifelong friends when you go on Sundays?

AB: In some instances, on the level of dealing with the young people, the kids and the young adults, to give them some of the benefits of my own experiences. I think that is one of the major benefits of my trying to go and trying to be there, to give them an opportunity to see history or to see life in action, rather than what they read in the books. (43:21)

RM: Well that's certainly a good reason to go. It sounds like the adults and the children intermix quite a bit at Sunday school.

AB: Right, right. They do at Sunday school.

RM: On a daily basis, how is your spirituality reflected? It guides your actions and do you set aside special times during the day to contemplate or meditate or say prayers?

AB: Well ...

RM: Or is your life a constant prayer?

AB: Life is not a constant prayer. Of course, part of our religious ritual, pause for prayer in the evening before retiring and the first thing when you get up in the morning, is say a prayer. That's a part of the religious ritual that I've been trained and brought up with and it is still a part of me. Still a part of me. (44:19)

RM: Does it extend to healthcare situations? Do you ever find yourself saying a prayer?

AB: Oh, yes. Ever since, I've been in practice...I'm glad you asked me that question.

RM: May I turn the tape over?

AB: Okay.

RM: All right. We're ready to go. Ever since you've been in practice...

AB: Ever since I've been in practice, I try to emphasize to all of my patients that I see myself as God's hands and eyes and ears here on Earth. I tell them that I am God's extension, Earthly extension, if you please. I can do nothing alone and whatever good that I can do is an act, which is mediated from God. I'm very serious about that. It happened last week. Even though I had referred a lady to the vascular surgeons...We ended up, she has an above knee amputation. The first thing when I went by to see her and to see how she was doing, as I got ready to leave, I paused to pray with her. I saw a lady who is about six years post stroke. I made a house call on her up in the Winterville area, last Friday. Of course, she is a lady who when she was active was an administrator. She appreciated so much that I paused, as I was getting ready to leave, to pray. I gus some of my people will call me the "praying doctor". That's all right, too. That's a part of me and that's a part of something that I enjoy doing and something that I am sincere about. I am very sincere and very serious. (46:37)

RM: Have you in the course of your practice found it important to... Well, what situations have you found it important to remind your patients that you are an instrument of God?

AB: Well...

RM: Is it critical times?

AB: To me, it satisfies an outlet of what I believe. That's the first thing. Then, in dealing with people who are of a religious background themselves, they appreciate it. Then far beyond that, I have in some instances dealt with people whos belief was not as mine, but as they would begin to recover, I've had people tellme that, "Doc, I didn't understand what you were you saying when you were talking, but now I understand it and the Lord has blessed me." I said, "Well, he's blessing you all the time in spite of you." It can make it a little joke or jovial or something like that. I said, "As bad as you are the Lord ought to frown his face and just go ahead and sweep you away, but he's good to you in spite of yourself." I would make it a little light. It goes back to a basic belief. (48:06)

RM: When you were educating, teaching the students about how to take care of themselves in so many different ways, how did your spirituality figure in there?

AB: Well, very often when they understood me as a person who was trying to promote a philosophy of being right, a person who is committed to doing right-- with all of these other things following that gave me an opportunity and believe me, I used it, to express the value of rightness and having a right philosophy and having a right behavior. From time to time, when it came to understanding things so far as mental health is concerned, your mental outlook has to do with whether you can accept reality or whether you imprison yourself by griping and bitching over everything that comes along, being good or bad. See, if you get caught up in a mental frame of mind that there's somebody against me and everything in the world is wrong, nobody is right on this earth except me. I am imprisoning myself and really sentencing myself to a disastrous type of existence. Who can be happy with that kind of a mental attitude? (50:00)

RM: Isolated.

AB: Yeah. You can't do it. So, it has its value. It can help one to weather the storm of adversity.

RM: For you, there's no separation then between what is right and your spirituality.

AB: No, no.

RM: Your morality goes hand in hand with your spirituality.

AB: Yeah. It goes hand in hand. This is exactly true.

RM: Well Dr. Best, thank you so much.

AB: You're quite welcome.

RM: I'm sure that the insight into your values and attitudes and spirituality will help other people understand.

AB: I hope that it helps them understand the person Andrew.

RM: I think it will. Thank you.

AB: You're quite welcome. (50:48)