[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. ANDREW BEST March 31, 1999 Interviewer: Ruth Moskop Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn 15 Total Pages Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: It's March 31, 1999. I'm Ruth Moskop and I am here with Dr. Andrew A. Best in his office and we are about to record another oral history interview. Dr. Best, do I have your permission to record this interview?

AB: Yes, you do.

RM: Wonderful. We left off last time talking about your Wednesday night classes that attracted students all over Eastern North Carolina and you called them Correlative Education Classes. Do you want to tell us a little bit more about that? What kinds of students came? Where did they come from? What were your lesson plans like? (0:36)

AB: This story started out with an interest and concern for a report that came out from the Bureau of Vital Statistics pointing out the high rate of illegitimacy in Pitt County. This was a great concern to the minority citizens because this high rate of illegitimacy was primarily among young minority females. There were many reasons for it and one of my great sayings in the response to that when the question would come up, "Well, why is it that the minority females are having these babies illegitimately or by unmarried mothers." It was thought that the young white females were just as guilty of sexual immorality or sexual activity. My personal response to that question was rooted and grounded in education which included moral values and moral teachings and all of the things that went along with it and I created a little phrase 'they don't know' and because they don't...'they don't care'; and because the poverty-stricken scenario for minority families, mostly, 'they don't have.' Where as, in the white counterparts, it was felt that the education level was higher and different. The so-called shame of illegitimate babies was also felt. Since the level was a bit higher in the segmented population where the educational level was higher and where the priority values were higher, I related this decline or this lower ebb of values and family values or moral values to poverty. Poverty translated into lack of education, lack of values, and lack of knowledge. Well, looking at and attacking that problem, it started out with the problem of illegitimacy. That was the focal point. That was the igniting factor that we started in all of the panorama of things which I felt affected the entire situation. So, with that idea, I developed through the medium. I felt that if we went through the medium of education, that we would let these minority young girls know that on this sex angle, there were such things as birth control. At the time, the use of the condom on the male was acceptable, and of course, we did not try to de-emphasize or underestimate the value of self-control or sexual abstinence. We were not going out preaching that you can have promiscuity and sex with no inhibitions at all. We were always up front that if you feel that you have to do it, if you are so emotionally overwhelmed that it's going to happen, there are certain protective measures that you can do. After the condom, they developed the pill, birth control pill. We never had context of any of this. I never preached abortion as an answer to unprotected sex. (6:18)

RM: Let me ask you this. What years are we talking about when you had the idea to start the ...?

AB: We're talking about the late '50s, '57 and '58. Even before the Terry Sanford era now, so now we're talking...

RM: How long did you teach these classes? How long were you active?

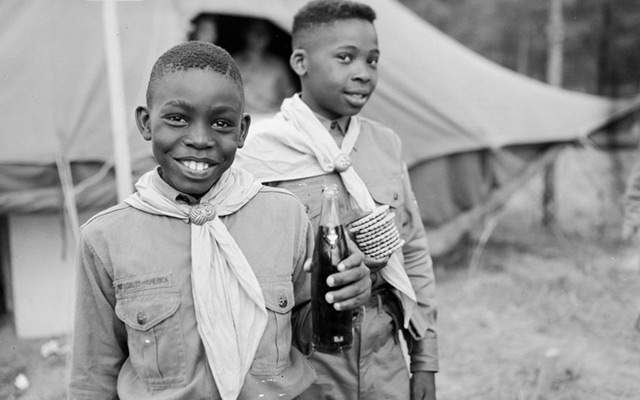

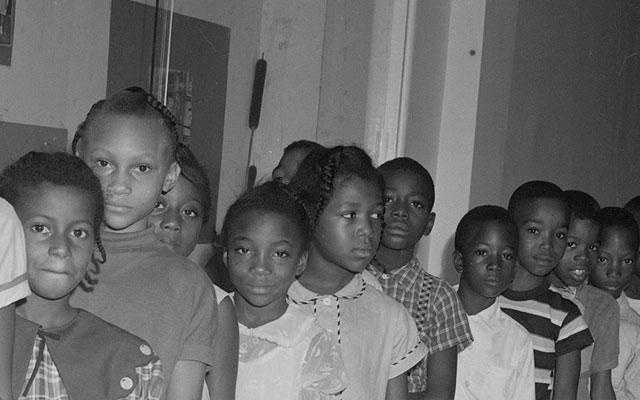

AB: The classes started at one school, Epps High School over here, one year probably in '57. In '58, we branched out to all of the high schools or union schools in the county. The union schools in Pitt County went grades one through twelve. They had primary and everything in the same school. That's why they were named union schools, but later on we got them subdivided to the high schools and then the middle schools and then the primary and then the kindergartens and all of that stratification. But, that stratification was not there in those early days in 1957. I spoke to the lady, Mrs. Ellen Carroll, who was the Assistant Superintendent of the City Schools. At that time the City Schools and the County Schools were divided. It's only been in more recent years that they merged, where those two boards merged. With Mrs. Ellen Carroll, who was I called a very sagacious or farsighted lady and I discussed the problem starting out that I was concerned about illegitimacy. You know it was really unpopular to mention the word sex in schools or sex associated with education. That is why in our development of a plan to solve the problem, we came up with what we felt to be the value of education. Having decided that, how are we going to do it? That was the next question to be answered. Since it was sinful to talk about sex in schools, I came up and Mrs. Carroll agreed with me with the plan to talk about contagious diseases or communicable diseases, that was the focus and that was right along with the promotion of health. Health is my field. It is my forte. With that entree, it was accepted and in developing this educational program with a focus on communicable diseases, once we got one foot in the door, we were able to expand and do a lot of things. Out of that effort was born the whole concept of correlative education. Now where did that fit in? Right along with all of these things, we recognized that minority schools had limited equipment. It was not equipped compared to the white schools. There were many other things. What little equipment they had were hand-me-downs. Textbooks were hand-me-downs, books that had been worn out and tom out at the white schools. So, facing all of that, my concept was that we move towards the business of integration. We had started talking about integration in the early '60s. By that time, my efforts had been heard about and I had gotten requests from the black principals and actually from Epps High School, the school here in Greenville to the entire county. Then, the black principals in the surrounding counties; Beaufort, Jones, Craven, Wayne, Edgecombe and as far down as Pasquetac and Elizabeth City. I had some folk down there. At the same time, my program grew through the efforts that I was able to generate from a cooperative venture between A&T and East Carolina University. I had a seminar for teachers that would prepare the teachers in the same area of health promotion, contagious diseases, and above all sneak in the unit of sex education. The subject of guidance counseling came into view. Dr. Fuller over at East Carolina was the head of the guidance department and when we developed the seminar for teachers, he taught guidance and I taught pure health. As we approached integration, my view was that the black child needed far more than what he was getting in his segregated setting. As we sent those children from segregation to integration, they needed more than they had. This is where correlative education came in. As we developed our programs and our formats and our outlines, going beyond a pure format of contagious diseases, we began to emphasize what I call every subject in the curriculum. The value of using good English, the value of knowing your math; that was what is the difference in having a decimal point one place wrong to the left or one or two places wrong to the right? It's a difference in ten dollars and a hundred dollars or whether you are supposed to have a hundred dollars, your decimal point is one place back to the left, you only have ten dollars. It was things like that and I emphasized correct spelling, correct use of grammar; where your verbs and subjects had to correlate. With this particular attitude and focus in teaching, I'd have those 350 students that I saw every Wednesday night to pass in written work for the next time. I graded every one of those papers myself, every one. I was very hard on a misspelled word or the misuse of a verb and sometimes the kids would come back and I would have my little red circle drawn around it. "But that is only minor." "Yeah. It's just as minor as you being paid ten dollars where you should have been paid a hundred dollars." That was my sermon constantly. That's where the correlative education came in. Now beyond that in correlative education, I tried to teach the children some mechanics of understanding versus the act of trying to memorize everything. See, if you understand it and you're asked a question whether it be on the SAT or whatever, you can be able to put a something together. I emphasized two words, I said, "When you approach a subject or when you approach anything, you think about two things; that's structure and function. How is it made? How does it work? If you understand those two factors on any issue or anything, you can come up with some sensible answers or some sensible explanation." Now this other thing that I tried to teach the children-and I told you about Bernadette Gray, she was one of the kids-was a little what I call educational gimmickry. That is, if you have a series of things that you want to remember, you can develop a little gimmick, a little word to say. For example, I asked whose pictures were on the monetary bills from one dollar to a thousand dollars. I said, "You're supposed to know if you spend money, you look, and you ought to know whose picture is on there." My way of remembering say one dollar, five dollars, ten dollars, twenty dollars, fifty dollars, and a hundred dollars. H you can say Wash Line's Ham Jack. Grant is Frank. Wash Line's Ham Jack period. Grant is Frank. That's two sentences. (17:15)

RM: Grant is...

AB: Wash Line's Ham Jack. Grant is Frank. Washington, Lincoln, Hamilton on the ten, Jackson on the twenty, Grant on the fifty, Franklin on the hundred. Just two sentences. Wash Line's Ham Jack. Grant is Frank.

RM: It's a good mnemonic device.

AB: Yeah. I called it educational gimmickry. It was a gimmick that would help them to remember the things that they might need to remember and you could apply all over the board. That was our core of correlative education, which as I say was an expanded thing from pure health sciences to contagious diseases and then we got in some widespread education. Now, another thing we did, I preached a sermon of health as being defined as physical, mental, and moral soundness, a state of well being; freedom from disease. See, in the average teaching concept, health was considered all physical. See the whole problem of mental health had not come widely known, recognized, or taught. Then, there was a feeling that a person could be strong physically, could be strong mentally, but have no moral sense of values and the person is still short. I used to say so many times that Hell stands on a tripod: physical, mental, and moral. I got my students believing in that and to make them further understand, now if we say health maybe the finest physical mental and moral soundness, a state of well-being, freedom from the disease. What is a disease? A disease is any deviation from the normal state of health. That's where I could tell them, "H you walk out that door and you fall down and you break a bone, that is a disease." Because the concept previous to my teaching so often was that the only thing they considered a disease was really an infectious process, and it's not so. We got through to the kids with such philosophical statements and correct statements to broaden their horizons and that's where we came in with this sexual education. Then in 1960, we were coming of age. In North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship was formed to be a vehicle for the expansion or the execution of programs on a much broader basis. We envisioned Eastern North Carolina, and wherever the leads would take us, we had the framework to do it. The reason we chose North Carolina Joint Council on what? (21:19)

RM: Health and Citizenship.

AB: Health and Citizenship. In citizenship, we got into the area of what we called good citizenship. That included those moral values and dependability. To do this, education was our key. So scholarship became a promotion, a fundamental part of what we were trying to do.

RM: So your correlative education classes sort of duck-tailed into the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship?

AB: Yeah. The Joint Council was a formal organization, which was designed specifically to promote these concepts through educational promotions, that's through scholarships, as well as whatever else we could devise to promote that concept.

RM: Who all was involved in organizing the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship? (22:31)

AB: Even though it was my dream and I was the so-called leader or the CEO, I had a group of educational minded people. There were some high school principals who came aboard in Lenoir, Pitt, Edgecombe, Greene, even up in Johnston County. There's a principal up there that I had known a long time, a Mr. W. R. Collins. I had a board of people and when we got ready to apply for a charter, we had those officers who were mainly high school or union school principals. Of course, there were other folk, too. It was mainly people who had been acquainted with our program, with our project, with our work. They came in to be members and supporters.

RM: I understand that there was also a sex education program, although it couldn't be called sex education in the white schools. Was that at the same time?

AB: I don't have any knowledge of that. I don't have any knowledge of that at all in the white schools. I know that in the schools where I was working in those days, the sex education was not even mentioned in our prospectus. Our prospectus only mentioned communicable diseases.

RM: I understand. (24:30)

AB: And a promotion of pure health. It was known that we supported health and its tripod concept.

RM: Sure.

AB: Physical, mental, and moral.

RM: You mentioned to me off the tape that in the late 50s, there was an organization organized ca11ed The Pitt County Interracial Committee. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

AB: Yes. The Pitt County Interracial Committee was the result of the meeting of ten whites and ten blacks. The formation of this group was spurred by an Episcopalian minister named Richard Ottoway. We affectionately called him Dick Ottoway. He came to me, and we discussed the racial atmosphere and what we thought was right and wrong. The discriminatory things were that when Dick and I would be traveling together, the only way I could get something to eat would be for him to go in and bring it out, or I would have to go to the back door or back window somewhere and have a take-out. We couldn't go into X or Y restaurant and sit down. So, it was those kinds of conversations and concerns, Dick and I thought the group should give special attention to, with special reference to the problem of segregation. It might be helpful in terms of making some progress without violence. So, we agreed that by invitation, we would form this group, The Pitt County Interracial Committee. We had ten whites and ten blacks. Of course, we met every month, once per month and we agreed that we would be in times of some crises. We might have to call a meeting, and we would meet in between times. The meeting was open and people who just came in to visit with us could make comments on certain concerns that should come up. Even though they were not an official member of the group, the meeting was open for their comments and their participation in the dialogue. After several months, the church called Dick to go somewhere else. Dick was the first chairperson. We had chairman, vice-chairman, secretary, treasurer and a whole bunch of officers. Dick was the first chairperson. I was seated to the chairmanship after Dick left as his vice-chair. My feeling was that I needed a white person for the vice-chair because we tried to keep those offices or places of responsibility staffed with both white and black. One of our constant and very productive members was a fellow named Ed Walldrop. Ed worked for Walldrop, Wagner Lincoln Mercury and even in his senior age, he's still with the Lincoln Mercury over here when they moved out on Greenvil1e Boulevard. Ed became the vice-chairman and I was the chairman. We worked very, very closely together in terms of having an input in community affairs. One of our first projects was trying to get public accommodations integrated. It took some months of dialogue, diplomacy, and all that kind of stuff. Our first approach to the merchants and the people, we had a five and dime, MacMillian's, down on Evans Street. They had a lunch counter and there were other people. At that time, Rose was here, and it had a lunch counter, but the lunch counters, as it was all over the country, were reserved to serving whites. The only way a black could get served was if he went and called for a sandwich, stood at the cash register where they would bring it to him, and they let him take it out. We had dialogue with all of the people here and some of the merchants that had drug stores and lunch counter said, "Well, okay. If we can get everybody to agree that on a certain date we all will drop the barriers, then we'll do so." But, nobody wanted to bell the cat so to speak. Nobody wanted to bell the cat. All of the rats and the mice in the woods had a great mass meeting and everybody thought the cat ought to be belled. So, when the cat comes around, the bell tingling would be a warning. But then, when the credit came down to who would bell the cat, nobody wanted to bell the cat. Nobody was brave enough. This was the way we approached and finally, we got all of the businesses and the people to agree. For example, the drug store that was on the Courthouse Square right across from the Courthouse, down on Evans Street, this gentleman had said that he would die and go to torment, of course he used that four letter word meaning torment, starting with a H... (31:20)

RM: I gotcha.

AB: Yeah...before he would serve anyone of them, talking about a minority. But finally, with pressures from the various other folks, he decided he would give it a try. What the Interracial Committee then did was to set up teams which we called barrier breaking teams or something of that form, where we had two people who would go in and call for service on that certain morning and the way we did it, we put the names of the businesses in a hat and each person would reach in and draw names. My partner was Mr. D. D. Garrett, who was a local activist and realtor here in Greenville. Whichever one of us drew the name, it was Biggs Drug Store. I said, "Oh Lordy. Have mercy." But, we went on with the police department, and we had all of the protection. They had police all over town, a couple of police standing by. (32:35)

RM: Was this on the day, the appointed day?

AB: On the appointed day.

RM: Do you remember what day that was?

AB: I don't remember. I probably could go back somewhere and then I can find out exactly.

RM: What season of the year it would have been?

AB: Yeah. It was in the spring.

RM: New beginnings. That's a good time.

AB: That's right, new beginnings. We tried to...We didn't hit all of the businesses and the restaurants that first day, but we agreed that sometime during that week...I think it was probably either a Monday or a Wednesday that when it got started. Then all of that week we would go to another place that had not visited for service.

RM: You had to eat out a lot that week. (33:20)

AB: Yeah. D. D. and I ending up going down to the Courthouse Square and I went in. There was an anecdote that one of our...

RM: Wait a minute. Is D. D. black or white?

AB: Black. He was black. Well, we had some...But the thing about it, we had some of our white counterparts who went, but these segregation-breaking teams were primarily black because our white counterpart would have been served anyway.

RM: Did it occur to you go in black and white pairs?

AB: Well, it might have been. There were a few instances where we had some whites. The main thing was to get a black person to go in.

RM: To sit at the counter?(34:17)

AB: Yeah. To ask for service. As we went in, we had our seat, and we could tell the waitresses by-passed us two or three times. Finally, they came over and wanted to know, "Can we help you?" We went on and said, "Let me see the menu." We went on and ordered. The anecdote about D. D. was that he asked for a glass of milk and his hand was shaking so bad that when he looked around and started drinking it, it was a milkshake. That was not true. That was anecdotal. But, that went off without a hitch, no violence. As we proceeded during the following week where we had not been served, I was very pleasantly pleased that it went off.

RM: Did other people begin to follow suit?

AB: Yeah. Yeah. After the barrier was broken, then gradually other people began to follow suit. (35:21)

RM: How did you publicize the day when it would happen?

AB: We didn't go public. We preferred not to go public. That was a quiet understanding between the businesses including the hotels and the motels. Now prior to this, the Holiday Inn was getting ready to open. This is just another instance. I left the office one day. It was advertised that they were going to open say roughly in about a week. I sought the person around who looked like he might be the manager, and I approached him. I said, "I'm Dr. Best. I need to speak with the manager." He said, "I'm he." I said, "I was really wanted to have some conversation with you to see if you would consider opening up this institution on an integrated basis." His answer to me unequivocal and quick, "Over my dead body." So, my answer to him was, "Sir, you better die very soon, because integration is coming whether you like it or not. Whether I disagree with it or whether you disagree, integration is coming. My view is that we would benefit from doing it voluntarily. This is my view. I think we could avoid a lot of problems if we do it voluntarily." I even went so far to say that, "Look at me. This black is permanent. It won't rub off. It won't rub off at all." So, his answer was, "No." So, I turned and left. But, in our negotiations all of the businesses or public accommodations including restaurants and motels, we got them all to agree that on a certain day, they were going to open the doors and they did. Indeed they did and indeed it went off without a hitch and without any violence at all. That's what we were after. We knew that the integration process in the schools was on track. The barriers had not been broken, but it was on track. This is the Interracial Committee's doing, prior to the Good Neighbor Council by Terry Sanford.

RM: Let me turn this tape over...

AB: Okay.(38:29)

RM: ...and then we'll talk about Good Neighbor Council. Alright. Now we're up to 1961 when Governor Terry Sanford started the Good Neighbor Council.

AB: The Good Neighbor Council. Well, Terry Sanford was elected governor in 1960 after a bit of fight against a staunch segregationist. His name escapes me. I'll think of it after a while. Terry was concerned about human welfare. Now, he was really what I call a person concerned about human welfare. He was sagacious enough to understand some of the dynamics of segregation and the ways certain people would treat it. He took the approach that education, the expansion of understanding through education and through personal contacts would be helpful and be in order. So, with this in the background, he created the Good Neighbor Council in the early term. He was inaugurated in January. It might have been in March or April or somewhere in early '61 that he created the Good Neighbor Council by Executive Order. To get it off the ground, he invited black citizens with whom he had contacts or confidence in, or who had some history of concern for race relationships all across the state. It was roughly about maybe 25 or 30 of us who answered his invitation to the mansion on this particular morning for breakfast. He told us that he had created the group by Executive Order and by invitation he asked many of us to serve on this Good Neighbor Council of which it was composed of black and white citizens.

RM: From all over the state? (2:39)

AB: All over the state. I was one of the people direct from Eastern North Carolina. I remember one of my good friends, W. R. Collins, who was a high school principal, was there. John Wheeler from Durham was there. There were others whose names I don't remember. One of these days I'll probably get the Executive Director of the present Human Relations to dig back in the files to get those names for me. At any rate, that was a statewide effort to ease the problems that we could foresee with integration and that would be created by integration with racial clashing. So, that gave me an opportunity to display some leadership beyond a local basis. So, that started out and of course, my local efforts through the Interracial Committee continued here in Greenville and Pitt County. Every time that we could make some contribution toward easing a situation that might become tense along interracial lines, we did it. You will see the article, "Our Thing," when you get a chance. That was an effort that primarily was sponsored by and supported by the Interracial Committee to help solve the problems of integration or integrating the schools. (4:45)

RM: This is an article in the Greenville Daily Reflector newspaper from May...No, I'm sorry, it's from October 31st, Halloween of 19...I can't tell. It's Friday. It says October. It almost looks like. It couldn't have been '69. It must be 1960. It was 1969?

AB: Yeah.

RM: All right.

AB: But now, you remember the Joint Council came in as an organizational vehicle. But, everything we did in the Joint Council, in this fashion, was supported by the Interracial Committee. We got the sponsors of the Pitt County Interracial Committee, the Pitt County Good Neighbor Council, the Good Neighbor Council City of Greenville, because we had two at the time, the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship, and the County Chamber of Commerce, and Merchant Association of Greenville, the Good Neighbor Council of Ayden, and... you see... (6:16)

RM: You're still working on public accommodations here, aren't you? You started in 1960ish when you...

AB: Well, this whole thing here is a contribution or aim toward easing the pains and misunderstanding of school integration.

RM: Of school integration?

AB: School integration.

RM: Okay. Our thing is on school integration.

AB: Is on school integration, but I'm trying to let you know that this is just evidence of the activity the Joint Council aided and abetted by the Interracial Committee.

RM: And the Good Neighbor Council.

AB: The one that I sponsored, the Pitt County Interracial Committee. It took a lot of doing to get that many people to understand and agree with this concept.

RM: To agree to publish their names. (7:15)

AB: Yeah. Of course, you are looking at the author of the article, but then my job was to sell the concept contained in this article to those other sponsors and supporters.

RM: Right. I understand.

AB: See that's a whole lot of legwork now, a lot of phone calls. So, you can see that all of these little pieces fit just like a jigsaw puzzle in terms of the whole concept. Then, in the area of human relations, going from education to human relations where this Pitt County Interracial Committee-then we had a Good Neighbor Council, a local Good Neighbor Council formed, and after Terry Sanford went out of office-see at that time the governor could only serve one term, four years. After Terry Sanford went out of office and Dan Moore was elected, there was some great concern as to whether Dan Moore would continue the Good Neighbor Council by renewing the Executive Order or whether he would let it die. Luckily, serving on the Good Neighbor Council at that time was this fellow, Dave Coltraine that I mentioned. Dave had worked on some other project with then Governor Moore, and he had a lot of influence on him. So what Mr. Coltraine did was to...I was on the state Good Neighbor Council as you know. (9:11)

RM: I have down here that you that you were the Chair of the Eastern Division.

AB: Eastern Division. That was with the work of Dave Coltraine. He divided the state in the Eastern Division and the Western Division. That was Dave Coltraine's organizational structure. He made me Chairman of the Eastern Division. Some guy from Winston-Salem was the Chair of the Western Division. All of the agents, the field workers east of Raleigh reported to me.

RM: That's a big job.(9:51)

AB: Yeah. And then they would go in and troubleshoot wherever our local county or city Good Neighbor Council Chair would call for help. We got the problems, we foresee problems, we have heard that we are going to have a demonstrational problem. Those field workers from the Good Neighbor Council in Raleigh, both of my field workers, the main ones actually lived in Rocky Mount and one lived in Kinston. They would always coordinate what the problem was, where they were being called, and they passed the information on to me. So, that went along, but after Sanford left office and Dan Moore carne in, Coltraine was still the Chair and then he started some efforts to have the whole human relations business recognized by Legislative Mandate as one of the official Legislative Councils of the state. He was able to, by his good office and good friendship with the governor, got it through. Then, the order of the Good Neighbor Councils became Human Relations Councils by Legislative Mandate of the whole state. That followed in order and for us to do that, Dave Coltraine worked with me. I'm sure he worked with other people, but he and I worked together several times. He was a little heavy and he flew a little cub plane. He would jump on his little cub plane and fly from Raleigh to Greenville. I would pick him up over there at the airport and bring him here. We would sit in here and we hammered out the language for the Human Relations Councils and the theory and the application was that once we got a State Human Relations Council, we would ask every local Legislative body; city or county to set up local Human Relations Council. The way it finally worked out was that the main Human Relations Councils on a local level would be formed actually on the County Seat of that county. So, that's where we are now and I would say that in North Carolina, that the Good Neighbor Council followed by the Human Relations Council from a state level did a whole lot to prevent us or to save us the violence that a lot of other areas suffered. Of course, you know that the county and city movements started in Greensboro at the lunch counters for A&T students, February 1, 1960. Then the sit-in movements spread all over the country, especially within the South and Southeast. (13:31)

RM: Before we go on to the sit-in movements from A&T there, I just wanted to make sure, was the Human Relations Council, the Good Neighbor Council, has that been integrated from the beginning?

AB: Yeah. That was integrated from the beginning when it was an integrated group that Terry Sanford called to the mansion to kick off the Good Neighbor Council as we knew it.

RM: All right. Tell us a little bit. Do you have more energy here?

AB: Go ahead.

RM: All right. What happened there at the lunch counter in Greensboro? What did you hear about it? (14:15)

AB: It was in the newspapers all over the country, on the radio and television. I was back here practicing medicine. I was not then on the Board of Trustees at A&T. Naturally, I was interested in the whole movement toward integration and good human relations. It was big news that these four young men, immaculately dressed, went and stayed at this lunch counter in Greensboro. I believe it was a Woolworth. Anyway, one of the five and dime stores. They sat and just wouldn't leave. They created all of that fury, and they just stayed until they were served. That kicked off the whole thing.

RM: How long did they sit there? Do you remember? (15:25)

AB: Oh, I read the accounts of it, but I don't exactly remember. My memory tells me it was the better part of a day, or it might have been more than one day before they were served, and they finally got it worked out.

RM: Well they didn't have their Interracial Committee going in Greensboro I guess.

AB: Well I tell you, demonstrations and...

RM: It was actually the Joint Council on Health and Citizenship that had the movement here in Greenville.

AB: Well actually, working in conjunction with the Pitt Interracial Committee and also the Good Neighbor Council following the Pitt Interracial Committee... I was the leadership on the Pitt Interracial Committee and whatever I did that was good, I would call in to my Joint Council followers and said, "Look, are you going to help us out? Are you going follow?" So, it was an easy thing for me being the leader of both groups. (16:34)

RM: Good communication. But at A&T, they didn't have an Andy Best, so the young men took it upon themselves...

AB: They deserve a place in history for the bravery and the determination that we are going to end this because the fight against segregation was brewing all over the country. Of course, it was led by Dr. Martin Luther King and all of his efforts down there and his meeting at the bridge with Bull Carly. And the racial atmosphere all the way across the country was very unstable, very volatile, and very dangerous. (17:30)

RM: So, you were not yet on the Board of Trustees at that time, but soon you were.

AB: Yes, in '63, I was nominated by the governor to sit on the Board of Trustee at A&T.

RM: And you did that until when?

AB: Until '72, actually when I came off the board to go to join the Board of Governors.

RM: I understand that you sort of counseled young students who were involved in Civil Rights movements at that time.

AB: Yeah. That was an ongoing thing.

RM: My notes say here something about coed dorms and noncompulsory class attendance. (18:19)

AB: Yeah. As a member of the Board at A&T, things were moving and there were a lot of student unrest and some of the students at A&T wanted noncompulsory class attendance patterned after the University of Chicago. I was on the board and I was one of the promoters of what I called student responsibilities. Let's promote student responsibility. Leave them on their own and if they care and are able to be in college, he ought to be responsible enough to do his work. I likened it to my own experiences as student at A&T where nobody had to tell me what time I had to get up to do my studying and nobody had to tell me what time I had to get up to make that job that I worked on a farm as a work student. See A&T ran a farm at that time. I worked for the poultry man and the pork producer. Of course, I put in some time at the college dairy milking cows. Anyway, I was an advocate of it and we passed it; the Board of Trustees, a noncompulsory class attendance, meaning that the student, as long as he did the work whether he went to class or not, the professor could not say, "Well, he did not attend class but X number of days," and flunk him on that basis. He'd pass as long as he did the rest of the work and made the class when the test was given. This young man, who was from New Bern, called me two days before the final Trustee Board meeting before commencement. We usually had a board meeting just before commencement. He called me and was saying that Dr. Thorpe had flunked him and how devastating it was. I said, "Well, okay. I'll be in Greensboro in the next couple days." When I got there, I found out what had happened. He had been to class just one day and the day that he went, the professor was putting a test on the board, so he left. He hadn't passed any of his exams. I said, "Well, the professor didn't flunk you. You flunked yourself. You failed yourself." That was an episode that I had to deal directly with a student. I preached him a sermon. I said, "Now, you made me look bad. I stuck my neck out to go along with giving you all responsibility and when you failed your responsibility and fail miserably, what does that say about me? It says that I must have either been drunk or crazy, or maybe both." We took care of him. He had had a scholarship to go out Midwest somewhere to do some special work. It so happened that North Carolina Central in Durham had a summer program that was designed for such cases where a student at this university at that level needed some make-up work. So, we got him in on that program. It turned out okay. (22:15)

RM: You saved the day, it sounds like.

AB: Yeah. It turned out okay. Which was a lot of comfort. Some headaches, some heartaches, and some hard work, and some telephone calls where I would call a friend of mine up in Durham and say, "Hey look, I got a problem. This student is so and so, blah, blah, blah." He'd say, "Well, give me the story and let me see what I can do to help you." It's contacts like this-that's another thing that I try to get instilled in students' minds that there's great value in knowing people who are in various places, but above all having your conduct so that those people not only know you but they respect you and that they have some feelings for you. I said, "Now, that's the key. You want a person who is in position to say yes or no. You want that person to have your interest at heart and to believe that if he gives you an opportunity that you're going to make good of. Otherwise, who will stick his neck out." (23:31)

RM: Makes good sense. You were a guardian angel for many students.

AB: All for the students.

RM: Well, Dr. Best I think we've talked enough about this today.

AB: Okay.

RM: So, we'll end our session?

AB: All right. All right.

RM: There are a few little odds and ends we want to talk about in one more session, I think.

AB: Okay. And we may need to embellish as they say public housing.

RM: All right. Public housing, we'll talk about that next time, too.

AB: Okay.

RM: Thank-you.

AB: All right. Well, thank-you. It's been, I think a very good session, a very nice session.

RM: We covered a lot.

AB: Yeah. We covered a lot. Okay. All right. (24:14)

15