[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL IDSTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. ANDREW BEST October 28, 1998 Inteviewer: Ruth Moskop Trancribed by: Sabrina Coburn 22 Total pages Copyight 1999 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No parts of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: All right. Good morning. It's October 28, 1998. I'm in the office of Dr. Andrew A. Best at 401 Moyewood Drive, in Greenville, North Carolina. My name is Ruth Moskop. I'm from the Health Sciences Library at East Carolina University, and I'm here to talk with Dr. Best. Dr. Best, your life has been interesting in many ways. You are a native of eastern North Carolina, who grew up nurtured by a rich heritage and a strong set of values. You served our country in World War II, studied medicine, and returned, to set up pactice in Greenville, North Carolina, in 1954. Since that time, you have made many important contributions to this community, not only in the field of health care, but in human relations and education, as well Because your personal history is an intrical part of the history of health care in eastern North Carolina, we plan to record interviews with you that will focus on a number of aspects of your life. Today, we would like to begin this series of interviews with a discussion of the minority contribution to the foundation of te medical school at East Carolina University, and we're especially interested in learning about your role in the evolution of the School of Medicine. Do I have your permission to record this interview? (01:31)

AB: Yes, you do.

RM: Thank you. The first thing I wanted to ask was that you tell us a little bit about your perspective on the early history of the East Carolina University School of Medicine. This would have been during the late 1960s, as it evolved from a one-year and then to a two year program.

AB: My perspective has been one of need, and in my opinion, there was never any question as to the need for a training...a medical training facility institution. To me, it was somewhat of a step attitude as we accepted a one-year or a two-year program. Always in the back of the minds of those who had faith and who were promoting the institution, it was always a four-year medical school. But based on what we could get at that moment, we did operte for a time on a two-year basis. Now, Dr. Jenkins really was the public advocate. He was the President of the University and after the Board of Governors was formed ...all Presidents of the Institutions became Chancellors. He was an early advocate of this medial school I believe it was in 1961, an organization, the North Carolina Council on Healh and Citizenship, was formed for the expressed purpose of interacting with the peope in education, trying to make the problems of integration easier, and trying to get equality of education to all of these poor students who had not previously had many opportunities from the standpoint of low funding in the minority schools. From hand-me down books to no equipment in the science laboratories; maybe a science laboratory, where chemistry was being taught with one Bunsen burner. (04:10)

RM: Oh, my goodness.

AB: You know, that was the scenario.

RM: Sure.

AB: And in order to try to upgrade the level of performance, especially of the minority students, this organization, the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship, was organized and chartered in October of 1960. Every year when we had our annual meeting, Dr. Jenkins was on our board and in our group of planners for a public program. We brought in a number of the officials in the political arena to be a part of our public programs and I believe it was in '61 or '2 that the mayor marked for the kick-off of this public meeting, which they always have in October. I agreed with Dr. Jenkins that there was a need for a medical school and I committed this young organization to that concept and that we would do everything possible to help to bring that into a reality. Further alon in the conversation, I probably can give you a little more background on what this organization, the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship, affectionately known as NCJCHC for short, was doing in terms of fostering education and trying to be a vehicle for promoting human relations at the same time. (06:23)

RM: Sure. As a community physician, what special thoughts did you have about a medical school at East Carolina University?

AB: Well, I thought that there was a great need for the training of more doctors. Some of the model institutions and some of the experts supposedly did not recognize it and they were saying that there were enough doctors. It was predicted that the doctors would be going around with nothing to do... (07:04)

RM: I remember that.

AB: Yeah, nothing to do and they would have no jobs because the profession would be glutted, and I tried to point out that number one, there was a real shortage of doctors, more acute in the rural areas, because most of the doctors who came out of school, because of the social opportunities for intermingling and satisfaction of wives, sweethearts, family, and what not, would migrate or settle into the larger areas, more industrial areas, and...

RM: Excuse me, Dr. Best. Are you talking particularly about black physicians or all physcians?

AB: Well, all physicians. I'm talking about all physicians. (07:58)

RM: So, there are more social and economic advantages to practicing in a big city.

AB: In the bigger cities, the industrial areas where they have an industrial payroll rather than the rural or the farming areas. Now, according to my experience and my observation there was a shortage, but the shortage was far more acute. You could multiply that shortage by fifteen to twenty times at the black level. There was a lot there involved in the attitude between black and white. If you look at it now and compare it with what we knew then, you wouldn't think it was true. When I came to Greenville, the white doctors who saw minority patients...they couldn't sit in the waiting room. Now some-few doctors had two waiting rooms. Other doctors, well all of the minority patients, would just have to sit in some hallway going from one place to another, between the lavatory and aybe the doctor's main office, sit on the bench and the doctor would see all of the whit patients first and then see the minority patients, the black patients. And all of those things were running in my mind. The greatest thought was here is a situation that needs some attention, it needs changing, it needs improving and this is what I committed myself to try to do by words and deeds. When I came to set up practice, I opened my doors and I let it be known that I was here to serve the public; all colors, kinds and creeds and from day one, I had one waiting room. The first building was kind of small, one waiting room, and all of the people who sought my services came and sat in the same waiting room. I assumed there was a psychology among the white physicians to think that their white clientele would resent sitting in the same waiting room with a black or minority person, and I think that my action demonstrated to the fact that people who seek services would not react negatively. They were seeking services together and they were sitting...they would be together. So, this was...it was a very quiet fight. I didn't go out and make a lot of public demonstrations about it, but we sought to demonstrate by my policies and my activities that this was something that could happen and would happen. (11:18)

RM: Well, tell me, I understand that you were a member of the Board of Trustees at North Caroina A&T University.

AB: Yes.

RM: And how did that come about?

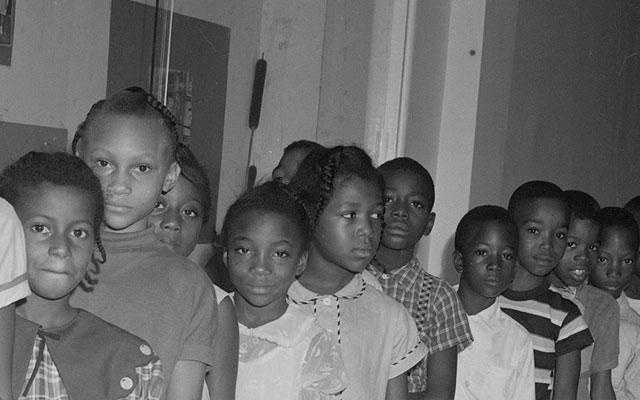

AB: Well, I was appointed to that board. My dates were from October 8, 1963 to June 30, 1971 when I left A&T to become a member of the Board of Governors. My involvement in promoting education really became known statewide. This organization which we found, the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship, involved the idea of an enrichment type of program realizing that the black kid needed more than he or she was getting from the school system. My answer to that was to have to develop and havea program which we call Correlative Education, meaning that we correlated all of the mportance of all of the subject matter all across the curriculum whether we're talking about math, whatever applies, we try some. We supposedly were concerned with infections diseases, communicable diseases, at which, I think we did a good job, but a partof that effort was to get across some sex education. Now we could not, at that time, openly talk about teaching sex education, but there was a unit in that whole course, which ran fourteen weeks. We'd always start in February and would go fourteen weeks and end up in April. This course, meeting weekly every Wednesday night, would have meetings in te gym to lecture to about an average of three hundred and fifty students from all over eastrn North Carolina, from as far west as Goldsboro, and from as far east as Elizabeth City (14:07)

RM: That's marvelous. Those lectures were packed.

AB: Yeah, yeah.

RM: I want to hear about some more of those in another chapter...

AB: Yeah, ok.

RM: ...of our interviews, but right now. I think what you're telling me is that as a result of your educational activism at a local level ...

AB: Right, at a local level.

RM: ...you had attracted the attention of people who were looking...

AB: People in the state who were looking for board members. This is exactly right.

RM: Ok.

AB: And, as I recall, my appointment was a governor's appointment by Governor Terry Sanford. I think maybe some of the other people at A&T probably requested the governor to appoint me to come and sit. Now, along that time, one of the things that got the presidents of the black universities to know me was the fact that I ran a program or semiar for teachers in conjunction with East Carolina University, and Dr. Fuller, who was n the area of counseling and guidance in those days, he and I worked together to do a seminar for teachers. I would do the health education part. Dr. Fuller would do the guidance and counseling part. (15:32)

RM: Fascinating. Was this at East Carolina University?

AB: No. We met over on campus at C&Epps High School. Dr. Fuller came over, but it was under auspices. It was a co-op agreement, as informal as it may have been, by the guidnce department at East Carolina and me personally through this organization, North Caroina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship and...

RM: You accomplished a great deal. (16:05)

AB: So, we were preparing teachers then to go out and duplicate the lectures and the efforts that I was putting forth on each Wednesday night, to do so in their own respective...

RM: In their own classrooms.

AB: ...classrooms. So, and then beyond that, there was some federal money that was coming in. We could recommend that each university or college have a certain amount of money that it could go for scholarships. With my providence, guidance, and recommendations to the various schools that those kids that I saw in classes on Wednesday evenings chose to apply to, I was very instrumental in helping them get some scholarship assistance at all of the major black universities. So, my name became very well known as a promoter of education, helping to get scholarships and all this kind of thing. That kind of a repuation, I'm sure, was the reason that they got me tapped to be on the Board at North Caroina A&T. (17:24)

RM: Now, how did your membership on the Board of A&T help you to promote the interests of developing a medical school at East Carolina University?

AB: Well, really it was two parts of what might end up being the same thing. At A&T, we were concerned with student problems and students who were more active after, especially after the Civil Rights Act of '64 and the sit-ins started in Greensboro. Eazel Blair, who was a student at A&T, a fellow named Richardson McNeal... and those four guys did those lunch kind of sit-ins. A&T had a student body that was very active in the aren of civil rights, and so we trustees had our hands full trying to give guidance to those students who were pressing for change. Well, that was just one part of it, but really, on a local level, I was active, trying to promote East Carolina Med School, locally even before I went on the Board of A&T... (18:52)

RM: Board of Trustees.

AB: ...Board of Trustees, and working with Dr. Monroe and what not. We promoted that and after I got on the Board of Governors then, the promotion of the medical school really came to surface and it was the front runner of activities, as far as education was concerned.

RM: Kept your attention.

AB: Yeah. Yeah.

RM: You've mentioned the Board of Governors because you were a trustee on the Board at North Carolina A&T, you were then in a position to be appointed to the Board of Governors?

AB: Yeah. See, when Governor Val Scott got to the General Assembly, the creation of a Board of Governors was to act as an overall umbrella for all of the campuses. Incidentally all of them would become universities, as a part of the overall Universities of North Carolina, but before that, there was a span in there where we had regional universities. East Carolina, Dr. Jenkins was a promoter of the regional concept. That's before '71 when the Board of Governors became a mechanism for controlling higher education and of course, the regional university concept was led by Dr. Jenkins, and it was fueled by his invitation, his concept of getting all of the black universities: A&T, Fayetteville State, North Carolina Central, Winston-Salem State and have them declared regional universities. So that went on there maybe four or five years-might have been six-as a forerunner to the Bob Scott University of North Carolina concept where we set up the Board of Governors to be the agency-the way they did it in their decision to form, to get this University of North Carolina concept working. One of the concepts to get board members was to go to each university, based on the size, and give each university the opportunity to name one or two of the proposed members, based on the size. Since they were trying to stagger their terms, they-each university-got a designation of maybe a two-year term and eight-year term, or a one-year term and a seven-year term. (21:57)

RM: The idea was eight-year terms, but they would be staggered.

AB: They would be staggered and so there was a number who came in at one-year term and be right up for reappointment. The re-appointments came, for most part, from the Senate and he House of Representatives. When it came to those re-appointments and I'm not sure. I don't remember. Maybe the governor had the chance to appoint in those re appointments, and I drew a one-year term. One of my fellow trustees, Howard Barnhill, who was a Greenville native, he and I sat down and said "now who's going to take the one-year and who's going to take the four-year?" and I said, "Well Howard, you take the four-year, I'll take the one-year because I'm going to get tired of this stuff sooner and I got people, practice of medicine..." (23:08)

RM: To take care.

AB: Yeah, to take care of and I may not be able to give the time that's necessary. So we, in a friendly sort of way, took the-I took the one-year term and he took the four-year term and oth of us were on the Board of Governors. And in that same group that was a thirty two member board, and we all stood together on whatever issue that came up. You know how the groups do, they have a little caucus. We had a little caucus. On the health question, as it came to the attention of the Board of Governors, being on the Jordan Subcommittee for Health Education and what not-in fact, I was the only physician on the oard of Governors. The other six of the seven relied on my judgement and my leadrship, and said, "Well, you're the doctor."

RM: You got health care done.

AB: Whatever you say, that's what we're going to do. So we stood. That's just another observation of how and why we stood together on the issue of another medical school for the state. (24:42)

RM: Well, now tell me, when that issue of another medical school came up, I understand that a special subcommittee was formed.

AB: Yeah. That's the Jordan subcommittee and Williams mentioned in his history, The Jordn Subcommittee on Medical Education, and it had five members of which I was one.

RM: What happened after they considered and the vote actually came up as to whether or not to found another medical school?

AB: Well, in this Jordan Subcommittee, there was a split. There were two for and two against and we were deadlocked. And after many weeks or months of discussion, it was obvious that nobody, the two who were pro and the two who were con, was going to change.

RM: They were going to stay that way.

AB: That's right. The pros were represented by me and a fellow named Reginald McCoy, who was from a trustee at ECU. We were the pros and the names of the cons; it's in the Williams history.(26:06)

RM: Good. We can find that out.

AB: They were set in their ways, too. There was only one thing to be done. The chairperson, which was Robert, the Honorable Robert Johnson.

RM: Jordan?

AB: Jordan.

RM: Robert Jordan.

AB: Robert Jordan would have to vote to break the tie, but looking back over it, I'm sure that Bob Jordan did not want to break the tie, for he had some political aspirations to become governor one day and he didn't want to get polemic...

RM: Polemic.

AB: The politician in him did not want to make him take the responsibility for making the decision. So, in consultation with President Friday-now President Friday is a great politician in his own right-he suggested that we-he's an arbiter and very good umpire, too-create this Blue Ribbon Commission of distinguished medical educators, and we set up our guidelines. We would take two of those members from the old, original schools and then we would take two from the newer schools. Now, the University of Kansas had a si-year program where they would take a high school student directly and train him for six ears and he-was expected to come out with a MD degree or close to it, and they had some, those newer medical schools, had some very innovative and creative programs. So, we were going to get two from those newer kinds of medical schools and then I spoke up and said well, you can't forget us minorities, so there should be a minority on that Blue Ribbon Commission. So, everybody agreed to that and so I was asked to contact some of my minority acquaintances and friends across the nation and the National Medical Association, in which I was very active. So, they could decide who to invite to that Blue Ribbon Commission from the minority prospect. Ok, I called Dr. Lawdill, who was President of Meharry to either to tell me if he was interested himself or if he could give me smebody. He told me, said well, I don't think I would be interested, and he pointed out how busy he was trying to run Meharry Medical College and so forth, and I knew that to be true. So, he asked me to consider Dr. Paul Cornelle from Howard University. I said ok. I knew Dr. Cornelle and I knew on my own, Dr. Eddie Cross, who was heavily involved in this innovative program out in Kansas City. So, since he said he wasn't interested, I recommended Dr. Eddie Cross. Choice number one; Dr. Cornelle; choice number two and so it went on to that. We began to go through reading CVs and act as a committee deciding who to invite, who would be the first choice and recognizing that some of the people might not be able to take the time off. Each position we had at least two people that we agreed that either one of which we could invite. So, suddenly at one meeting, Dr. Elam's name was added to the group and I said to myself, "Well, this a little bit strange because Efam's long time acquaintance and friend had told me..." (30:58)

RM: He'd rather not.

AB: "...he'd rather not." He wasn't interested in serving and I wondered why, but I didn't question it. I figured that it was like a game of chess. Dr. Friday checkmated me because he asked me-he said "Andrew, we got three distinguished people. Would you have any problems with either one of them?" I said "No, all of them are distinguished medical educators," and I was satisfied. I didn't have any disagreement with Dr. Elam being invited to be among the group. Still first choice: Eddie Cross, second choice: Paul Cornelle, third choice... I hadn't, because we were asked to write our first, second, and maybe in some instances third choices of my choice. But, when we finally got to the meeting where we were going to make those final cut-offs, Dr. Elam's name was on the first of the list and then Dr. Cornelle and Dr. Cross were down on the bottom of the list. I don't know why that was and yet I had already said either one was all right, so I was checkmated. So, I didn't raise any fuss about it. When the meeting in the first board assembled in Chapel Hill convened, I was real pleased with Dr. Elam because he was askig and raising the same questions about rural health care and doctors for the rural areas, and encouraged to serve the rural area and primary care. You know, he was right on time, right on cue, and I saw him a month later at the meeting in New York, and I asked him "Hey, how you guys doing?" and he started hedging a little bit. I said hum, there was something, something... (33:18)

RM: Something I don't know about.

AB: Something is rotten in Denmark, yeah. Something I don't know about and I didn't raise any real issue with him, but later on when the group made its final recommendation, it recommended, in effect, that there was no need for another medical school in North Carolina.

RM: That was the decision of the Blue Ribbon Committee.

AB: That was the decision on the Blue Ribbon Commission, we called it a commission, and...

RM: Cited no need.

AB: No need, no need. That brings us up to when we debated whether to adopt that report from the Blue Ribbon Commission or whether to reject it. That was a real, what you call, it was not say a fiery meeting, but there was a lot of heated debate on both sides.

RM: A lot of emotion. (34:24)

AB: Yeah, a very emotional meeting on the part of the Board of Governors.

RM: Before we get to that emotional Board of Governors meeting, do you want to tell me how you found out how Dr. Elam ended up on the Blue Ribbon Commission?

AB: Well, it took me two years. It took me two years and I found out. See, one of our negative people, Dr. William Anlyan, who was at Duke, he was one of the most nay on the nay sayers. Dr. Anlyan was a widely known physician on foundations and one of those people who gave out big money. And I found out...

RM: What was his name again, Dr....?

AB: Dr. William Anlyan.

RM: All right.

AB: His name is in that book there.

RM: Great.

AB: He had been responsible for getting Meharry some mega bucks from one of these foundations and it all came clear to me then that Dr. Friday knew of Dr. Anlyan's help in Meharry. (35:44)

RM: It was not a meager sum either, was it?

AB: No, no, no. It was mega bucks. Maybe a million, million and a half-dollars.

RM: That was a lot of money.

AB: Lot of money and well I give Dr. Friday-he's a very astute individual and administrative, very astute. He's just a smart guy. He wanted to get his points over and to reach his goals. He didn't leave many stones unturned. He didn't leave things to chance because one of his, I don't know what his philosophy was, but the way he organized and the way he operated...he operated on a theory of things left to chance; chances are they're going to go wrong. So, he left very little to chance. He did his homeork and I know in my mind that he had figured out that he in view of the fact-Dr. Anlyan was from Kinston. He and Dr. Bill Friday were very, very close friends and allies. Dr. Friday, at that moment, was very much against the whole idea, and I'm as sure as I am lving that it was an effort or a planned operation to rope Dr. Anlyan-I mean Dr. Elam in to keep him from raising other points of view. (37:41)

RM: It looks like Dr. Anlyan tried at the beginning to convince other people. He made his statement, but it had no effect, so then he was sort of forced to.

AB: Well, I think there was some pressure brought against Dr. Elam. Now, when I say pressure, and they had some great pressure points. Here is Dr. Anlyan, who is against the idea. Dr. Anlyan had been a huge benefactor at Meharry by the source of the mega buck, in the millions of dollars. So, the easiest thing in the world would be then for Dr. Elam to at least agree or not come up and declare open warfare on those people who are going the other direction.(38:44)

RM: Sure.

AB: Yeah. See, so, I don't blame him because they had him roped in. This is my judgement of the situation and it was almost should have been expected...

RM: Yes.

AB: ...that he would go that way. So, now whether he was against that resolution at heart, but just didn't voice it, I don't know. I never talked to him about it, and I've seen him many times, but I never questioned his decision because that was a unanimous position that BlueRibbon Commission took, and he was one of them. Now, whatever debates went on behid closed doors, we all came out, all five, just like the people come out of a jury room. Everybody comes out, and says, "Well, we agree to the death penalty."(39:49)

RM: Goodness, but then what happened to that death penalty? It was heated; there was a very emotional...

AB: There was a very emotional discussion and ...

RM: At the Board of Governors.

AB: ...at the Board of Governors. When it came my tum to speak, I spoke for the rejection of this report, this Blue Ribbon Commission's report, and very quietly, but very sincerely, I told the board, "Ladies and gentlemen, if we adopt this report, some of you will probably think that this subject will be dead forever and buried. That's why I like to remind you that some two thousand years ago, Christ was crucified, he was buried, but he rose again, and this question of health care and medical service to the people in Cowpen, and Bear Grass, and Calico, and Pigfoot Junction, and all of those rural areas is going to rise and rise and rise and keep rising, until somebody hears their call or hears their cry. It will keep, it'll continue rise and if we, of this board fail to act appropriately at this time, it will only take the question from the academic arena, where I think it belongs, and put it over in te political arena where it doesn't necessarily belong. But the politicians are going to act, they're going to hear and heed those calls from Chetlinswitch and all those remote places," and I got so far as to predict that within our time, there will be another degree granting medical school in North Carolina. The politicians will do what we academicians apparently refused to do and sat down. (42:27)

RM: That was your Easter speech.

AB: That was my Easter speech. Yes, yes, that's right, Easter speech and it came true and it hovered on Scott-Senator Bob Scott's uncle, Uncle Ralph Scott was very close to Dr. Jenkins, and he had some people, some influence with the Speaker of the House, Mr. Ramsey.

RM: Well, go back a little bit. Now, tell us about, so the, excuse me, the Board of Governors went ahead and voted...

AB: Yeah, the Board of Governors voted to adopt that report, eighteen to fourteen. There were seven black members who stood solidly for its rejection.

RM: In other words, in favor of another degree granting school. (43:21)

AB: Yeah. Yeah. To do that, we would have to reject the recommendation from that Blue Ribbon Commission and we seven blacks stood firmly and seven white joined us, so that sort of closeness of the vote, Dr. Jenkins went forward to initiate some efforts to get some legilation introduced in the General Assembly. He was successful in getting Uncle Ralph Scott to do it for them, in the Senate and the Speaker of the House, Ramsey, to do it on the House, and so the legislature went to the General Assembly. It was introduced and referred to a committee. On that reference committee were five people; there was one black, now Justice Henry Frye. He was Representative Henry Frye from Greensboro at that time. That reference committee was split down the middle and each side was wooing Representative Frye to come to that side and one representative said "You're from Greensboro. Your constituents don't want this thing. They don't believe in it" and Representative Frye said, "Well I have some concerns." "So, what are your concerns?" "I'm concerned about the recruitment and training of minorities," and the pros seized upon it and said "Anything that you want to go into this legislation, just write it down, and we will put it in" and I have somewhere in my files, a copy of some little scrap of paper program that he had sent me a photocopy of what his note was that he wanted in this legislation, and they put it in and reported it, and his vote got that legislation out of committee where it could be acted out on the floor. (45:42)

RM: On the floor.

AB: So, that was just another stone in that the minority contribution was real and significant.

RM: Very significant.

AB: Yes, very significant. (45:55) End of Side 1

RM: Because the committee was deadlocked... All right, I had to turn over the tape, Dr. Best. You ere telling us about how strong President Friday's opposition was to the legislation.

AB: Yes. He brought the whole Board of Governors over to lobby against the passage of this legislation, but when it was all said and done and the legislation passed, as I would suggest, my respect and admiration for President Friday went out, right on up through outer space, because his worry was if we got to have it, we might as well make it a good one. He started working as hard to help make it successful as he had fought against the idea. I have thought about it, and I've asked myself the question, "why did it flip flop?" I honestly believe that President Friday, being an acute student of history himself, and had an internal bum in his eye to always be identified or history to record him as being identified with something successful. He wasn't about to let this opportunity pass and have history record him as fighting a project that was successful-that became successful in spite of him, rather than because of him. So, that is, I think, a great compliment and a great credit to Mr. Friday. It was action and I admire him for it, no matter what, but I suspect that the cause or the motivation behind it was that he just did not want to be recorded in history as being negative to something that would be successful. Incientally-this is to my knowledge-this is the only medical school with a legislative mandate to the recruitment and training of minorities and, as far as I know, since its creation, the school has been in compliance with that particular mandate and all credit is give to this administration of the medical school. In this operation, I think it's done a wonderful job and deserves credit for it. (03:10)

RM: There's another part of the mission too, to train physicians who have practiced primary...

AB: Primary care. The emphasis on this medical school is the production of primary care physcians and my observations have been that since the medical school has been on the scen, we have had more people, more physicians going to the rural areas and helping to solve the problem of health care to the rural areas. Of course, there are some other factors toimpact it now: the formation of these HMOs and all of these health maintenance orgaizations. That's a story all by itself, but, and I think that the HMO approach is not going to be the last work in health care. It was supposedly promoted as a cost saving venture, but what has happened, they hired a CEO, that is a Chief Executive Officer, to run the organization and pay him mega bucks, you know, anywhere, 150,000-200,000, 500,000 a year, and... (04:48)

RM: That's big bucks all right.

AB: Big bucks, big bucks, and it's not money that is going where it ought to go-to help the struggling doctors and many of the doctors who are in practice, who are giving the most are struggling to make ends meet, financially. But the public attitude always is "the doctor is rich, he's rich. He makes a whole bunch of money and he's charging, and stuff." Most of the doctors who are going to give service for the sake of service, you know, they are struggling just like everybody else. (05:38)

RM: Dr. Best, you mentioned about how strongly President Friday lobbied against the founding of a new four-year medical school. There must have been a lot of lobbying going on for the medical school, in order to get it through Congress.

AB: Yes. Through the House and the General Assembly, yes it surely was. Now, there was a lot of lobbying done. I did a lot. Personally I knew several representatives from Johnson and Oxen Dine and from down around Lumberton and several other people, who were in the General Assembly. I took off and went to Raleigh and stayed the day to ask my friends, of course I appreciated it with phone calls and contacts. Then I asked each one of the people whom I knew in the General Assembly, who agreed with us, to please use all of teir acquaintances and friends where they had some influence to go along with us. So, it was really an effective piece of lobbying. It greatly affected the outcome, because we got the legislation passed. (07:01)

RM: Tell me also, now you're term on the Board of Governors ended up being the one-year term.

AB: One-year term.

RM: And then, you were appointed to the Board of Trustees at East Carolina University.

AB: Right.

RM: How did you feel about that?

AB: Well, as I mentioned earlier Howard Barnhill and I had a one-year term and four-term and by a decision between the two of us, I took the one-year and he took the four-year. At the end of the year, I kind of expected to be reappointed, but it didn't work out that way. Thatwas a political appointment where I should be reappointed by the Senate and my undestanding was that there were some efforts to cause my name not to be approved in a renomination effort because of my position on the East Carolina Medical School question and... (08:21)

RM: They wanted to clear you out of the Board of Governors, in other words.

AB: Yeah, yeah. To me, that was called punishment for my strong efforts and my strong unwavering position. Well, as it turned out, a friend of mine, who is Judge Earl Britt, was an attorney then from Lumberton. He was on the Board of Governors and he was Chairman of the Trustee Committee to appoint trustees to the various organizations or institutions under the umbrella to be sure that all of these boards were integrated. See, prior to that, all these various institutions were not integrated. Not only the integrated boards, but the boards of the predominately black universities. We always had whites on our Boards of Trustees, but there were no blacks on the boards of the major institutions. One of Judge Britt's Board of Governor's members-Earl Britt was Chairman of that Boar of Trustee, placement of trustees-was to get all of these boards integrated, and he called me aside and lamented the fact that I was not reappointed and he said, to the effect, that he thought that I was one of the most effective members of the whole board. It was just unthinkable that I wouldn't be reappointed, so I shook it off and I said "Well, you know, it's not all that bad and I'm not too much concerned." He asked me, "Where do you ant to go?" He said "Now, I have requests for your services. A&T wants you bad, University of North Carolina at Wilmington wants you, Elizabeth City wants you, and East Carolina wants you." (10:42)

RM: You were in demand.

AB: So, I said well, send me to East Carolina. Without hesitation at all, I said send me to East Carolina. I had personal reasons for wanting to come to East Carolina. One, I thought I would be in a better position to continue to fight to make this a good viable institution and f course, at that time, the General Assembly that we talked about had my past and it would put me in a better position to fight for it as a member of ... (11:25)

RM: To fight for the medical school.

AB: To fight for the medical school as a member of East Carolina's Trustee Board and the second, I guess, more personal was that through the years I had been very close to Dr. Jenkins. We were very good friends and we belonged to Mutual Admiration Society. I admired him, he admired me and we had confidence in each other, so I thought that it was only a good tum of faith that I would break the barrier on the Board of Trustees at East Carolina.

RM: Break the color barrier.

AB: Huh?

RM: Break the color barrier.

AB: Yeah, break the color barrier. Well, I said that's faith, but since I had done so much work, you know, in this whole arena, in getting a lot of things done in partnership with Dr. Jenkins, it seemed to be... (12:27)

RM: Fitting.

AB: Very fitting and rewarding that I would be the first, so I came to East Carolina on this Board of Trustees and Judge Britt had the option from his position as Chairman of the Board to give out some three-year terms or four-year terms. My first time was four years and I was reappointed for another four years. So that gave me the maximum legal limit of eight years on the Board at East Carolina.

RM: It's a good stint of service. (13:10)

AB: Yeah. A good stint of service and after I had been off a year, there were several people who asked me if I was interested in coming back. I said "No, I think I've paid my dues and done my work," and so I said I have to tum my attention now to other things to pursue, but it was a very good experience.

RM: What did you say to those board members? Here you were the first black member ever on the board and Dr. Jenkins asked each of the board members to introduce him or herself. What did you tell them?

AB: My statement to the board that I am Andrew Best and I want everyone to know that I am a trustee of this university. I'm not a black trustee, I'm not a Negro trustee, I'm not a colored trustee, but I'm a trustee, period. My focus will be to do the very best I can for the nterest of what's going to be good for most of the students, and that will be my goal and my guide, and I just want you to know that. So, I was off and running, and sometimes in very subtle ways, I carried out that mission of being known for having a reputation of being interested in issues for my color, and I was very active in my own assessment. After I had been there for four years, my assessment of my performance was in trms of influence and respect. That I enjoyed, probably next to the Chairman of the Board. We had very good chairmen during my stint, Rodney Jones from Raleigh, and Troy Pate from Goldsboro, and I didn't always speak, but anytime I spoke, I was heard.(15:32)

RM: People listened.

AB: People listened. What did they say about E. F. Hutton? When E. F. Hutton speaks...

RM: In this case, it was when Andy Best speaks, people listen.

AB: People listen. This is the assessment.

RM: Well, they respected you for being knowledgeable and fair, and for your good judgement.

AB: That's right. That's exactly right. (16:00)

RM: Well, Dr. Best, I think we've talked a lot here about your role in the founding of the medical school. There were a few other ways in which you contributed to the development of the medical school. I understand you enjoyed your role as a strategist and through your membership in other organizations-I'm trying to remember the name-the Old North Medical Society...

AB: The Old North State Medical Society, yeah.

RM: The Old North State Medical Society. How did you interact with that group?

AB: Well, in June of '72 on the issue of whether or not was very much in the news. I entered the resolution at the annual meeting of the Old North State, requesting that we adopt or support the concept of another degree granting medical school within the state of North Carolina. When I submitted the resolution, it was one of my counterparts who made the accession, "Oh, here we go again. Best is only being a little Sir Echo to Leo Jenkins" and that's when it raised my eye. I don't usually let my eye be raised. (17:34)

RM: But your feathers were ruffled.

AB: My feathers were ruffled. At that particular time, I said, "Let me tell you something." Technically and parlimentarily, I was out of order because the Chair was in charge, and this doctor's remark was blatant and out of context, so I matched him with being just as much out of order. I said, "Let me tell you something. I don't need you or Leo Jenkins or anybody else to speak for me. I speak for three people; that is me, myself, and I, and I think I'm capable of doing that." (18:18)

RM: And you did.

AB: Yeah.

RM: And what happened to that resolution?

AB: That resolution was referred to a committee, and...

RM: That happens a lot.

AB: Yeah and the chair of that committee, who was a good, knowledgeable friend of mine, Dr. Johnson from Durham, invited me to come and sit with the committee, and somebody wanted to question my presence, and Dr. Johnson said I was there by his invitation and he uttered one of those little words that starts with a d. (19:03)

RM: Oh my goodness.

AB: He introduced the resolution and said that if I need his comments, he's willing to make then and so, that was the end of that wedding piece and that resolution passed without comment. There were a few little editorial things that needed doing that were added. What happened was the secretary of that committee was charged with putting in the editorial comments and what not. So, after the meeting adjourned, he came over to me and asked, "Are you going to be busy this evening?" It was in the evening, about five or six o'clock. I said, "No, I'm going up to the room." He said, "You heard those editorial comments. Would you take this on up there and put them in for me and prepare it for my signature?" Our typing was done by a secretarial pool and I put those comments in and early the next morning, I took it down to the secretarial pool, got the resolution typed up in its proper format for the secretary to sign, and delivered it to him. We met at breakfast about 7:30. I gave him the six or seven copies of the resolution, so he signed them all, and we went back. (20:42)

RM: That secretarial pool was up early.

AB: Yeah, yeah. But it was my resolution and I felt real good about doing the secretary a favor, so as long as we were reaching success, that's all we were concerned about.

RM: That was the important part.

AB: Yes. That was the important part.

RM: Maybe we could get a copy of that resolution to put in the file.

AB: I don't remember seeing... It was the property of Illinois State University.

RM: They'll know where to go and get it. They must have a copy still.

AB: They might, but I could, it was a very simple resolution, as I recall, and it calls that we need another medical school, and my judgment and so, and so... We resolve that we go on record as supporting... (21:43)

RM: Endorsing the...

AB: Yeah. Endorsing another. I don't know who would have those records now.

RM: We'll work on that later.

AB: Okay.

RM: We'll work on it later.

AB: And, if not, I can draft you a resolution that will tell the sense of what happened and so, it should suffice. (22:07)

RM: Okay. Let's see, now we are as far as the medical school having been legislated here. Let's jump up a bit. In the early development of the School of Medicine, you mentioned to me that you enjoyed your role as a strategist and you compared your role as that of a particular football player. Do you remember that?

AB: Yeah. Well, you see Ed Monroe and I-Dr. Edwin Monroe and I spent a lot of time, like every Monday morning, we'd meet right here at this office. I moved to this place in '68. He'd come by and have a cup of coffee or something, and we would go over what had happened the previous week and what ought to be said and what ought to be done. After I go on the Board of Governors, I would hear things that were very critical of Ed that I woul never even tell him. He heard enough and he would get fired up. In one instance, Ed would share things with me if he'd write a letter, write a response to something. He said now, tell me what you think of this and one this particular morning, Ed really had had his feathers ruffled and he said what do you think of this. I read it and I said Ed, this lettr is so hot, it would self-destruct before it ever got from here to Wilson, on its way to Chapel Hill. So, I kind of toned it down for him and he went on. But, Ed and I worked together very, very well He respected my opinions and I could give him some thoughts and ideas, and in most cases, when Dr. Jenkins came out with a public statement, it was a position that Ed and I had prepared for him. See, that's why I say that Dr. Jenkins was the pokesman, but Ed and I were really the strategists, the primary strategists and, of coure, Dr. Wooles. Wally Wooles came into the triangle, to the strategists. There were others, but by large in those early days, they called Ed and I the East Carolina University twins. (25:00)

RM: Is that right?

AB: So, that's what some of the folks dubbed us as the twin promoters.

RM: You mentioned that you thought of yourself as a guard on a football team.

AB: Yeah. You see, I likened that to the fact that the quarterback or the ball carrier gets the Monday morning raise for having made the touchdown, so that's Dr. Jenkins' department. Those guards and tacklers down in the trenches, who opened the holes while the ball carriers go through, they're seldom mentioned and that's a part of the game, and Ed and I understood that. I think, I notice here recently this year that they named this AHEC Building after Ed Monroe, and it was recognition to my mind-it was long overdue, because my judgment is if there hadn't been an Ed Monroe, there wouldn't have been a medical school. His presence was just that valuable. I can put that in the same category with say, if it had not been for contributions of the minority people on the Board of Governors, and if they had not been strategically placed in the General Assembly when they came out of the Reference Committee, there would have been no medical school. See, those two periods in the development of the school I think deserve some kind of highlighting. In that period, the minorities stood unflinching at the Board of Governors level, and Henry Frye happened to be in the right place at the right time to unlock the doorso the legislation could get out. (26:57)

RM: With his key words.

AB: Yeah.

RM: So, that people can understand.

AB: Yeah. That's right.

RM: Consolidated the effort, I think.

AB: Yeah. And Henry deserves a great deal of credit, because if you can picture the scenario where we pros had lost in the Board of Governors. The cons were in charge and we went to get a second motion. We went from the academic arena to the political arena to get legislation passed and had we failed that. Henry Frye was really the angel that got that legislation out so it could be debated, and that permitted all of our lobbying to come into play. Otherwise, there would have been no bill on the floor to be lobbied. (28:07)

RM: It's wonderful to see how the pieces of the puzzle fit together.

AB: Fit together. Sure, sure, sure.

RM: And all of the little nooks and crannies that have been overlooked are just now being recorded because your willingness to grant us this interview.

AB: And I see, incidentally now it is true that the Old North State and the Academy of Finely Physcians were the only two groups of organized medicine to support the concept of another degree grant school Everything else was a rave against us. This North Carolina Medical Society, hospital at Chapel Hill, Duke, Bowman Gray, and all of the heavy hitters were on the other side of the fence. (28:55)

RM: Why do you think that? Do you think that it was the unfamiliarity with the area? Why do you think they felt so strongly against it?

AB: I think that historically that everything east of Raleigh, with special emphasis on east of I- 95 going through there, has been the stepchild of the state for eons and ages and the people in the west kind of resented Dr. Jenkins for crying out loud for so long to show that the east was being neglected. He, a three-year, was accusing the westerners of exactly what they were guilty of and they didn't want to hear it. That's one of the motivating things why this artist drew that picture, you know, High in the Sky. He and Leo Jenkins down there holding the string of a kite that's high in the sky. They couldn't even conceive the possibilities. Now the medical school's presence, in my judgement, is the best thing that has happened to eastern North Carolina in the last one hundred years. Look at all of the development that's going on around. Now we have the medical school and the people are coming here to work with the medical school and various specialties and supporting specialists. The people at the hospital are far less important that the people who are spread out in these industries around here to live because they are doing some work in the supporting industries. See, this school and the hospital are not within themselves an island, you know. (31:08)

RM: I understand.

AB: But, the supporting industries that it draws around. I don't care if its transportation or whatever, hotel industry... All of these things are development. Now, look what's happened over in the stadium, where they've added on, so we can accommodate about forty-seven thousand people a ball game. Well, that kind of a factor with a football team, where you go, people got to stay somewhere. It is the hotels. What else you got? They get ungry, they've got to eat, the restaurant facilities, and all of these things. Now really, about the only place we're short right now is and they're fighting that battle. We need to get some better air transportation. (32:08)

RM: Into Greenville.

AB: Into Greenville. We need to get some better air transportation and they're having some little hang-ups about where we're going to extend the runway, but I think probably that ten housand foot runway they're getting ready to build at the jetport over in Kinston, will be of some benefit to us, in this area, too. So, all of those pieces of the puzzle fit.

RM: So, you see, the medical school is an important factor in the economic growth of eastern Nort Carolina.

AB: Sure, sure. When I say it's the best thing that's happened it eastern North Carolina in the last one hundred years, I'm including of all those advantages. (33:05)

RM: All of those factors.

AB: All of those factors; housing development. Look around here at all the housing developments and communities where there are condos going up everywhere.

RM: They surely are.

AB: And you say, where are the people going to come from to fill up all these things, but somehow or another, they're filling up.

RM: What about the level of healthcare? Have you seen a difference in that? You mentioned earlier the rural communities are being better served.

AB: Better served and the presence of a tertiary hospital here is important. For example, there was a person with a head injury in Elizabeth City some years ago. They tried to take that person by ambulance to Duke, even before the days of the helicopter carriers, and eight out of ten cases, the patient would die before you ever got to Duke or to Chapel Hill. But the presence of a tertiary hospital where we have neurosurgeons, we have heart surgeons, we have the capability to do it all, and if there's a special case-like a burn case, where you send them to the burn center-this hospital is thoroughly capable of doing stabilizing care to the patient, where they can get them out on a helicopter or whatever. So, all of those factors really are important and would not be here if it were not for the presence of the medical school and its affiliated hospital. (34:57)

RM: Let me ask you this. Have you experienced the joy of someone you've taken care of as a child or someone who's family you've helped provided healthcare for going up and attending East Carolina University School of Medicine?

AB: Yeah. There were the Jones' twins from Kinston that came through here, and they're now out successfully practicing on their own, and there are some others, too.

RM: Did they stay in eastern North Carolina?

AB: No. The Jones' kids opened up in Virginia, but they are in primary care and there have been others that I have had some personal contact with, even to the point of rotating through my office as an apprenticeship. That's always a pleasure to see, aspiring young people to come through. I love that. That is consoling to me and tells me that all of my efforts have not gone in vain. (36:13)

RM: I know that must be a great joy, having them come through.

AB: Yeah. You realize the dream.

RM: It gives you new life.

AB: That is exactly right It gives me hope and energy to go on, keep moving.

RM: Well, Dr. Best, I think we've covered our outline.

AB: Yeah. And, I see, you've got in there some follow-up care I know somewhere. On one of these pages, you've got the housing authority.

RM: That's in a different. .. (37:00)

AB: That's in a different...

RM: ...interview. We can plan to do that.

AB: Okay, okay. Because now that is something that really...

RM: Is a chapter of its own.

AB: ...is a chapter of its own.

RM: We'll schedule an appointment to record that part of the story.

AB: Okay. Well, whenever you come back, whenever you want to, we'll get into that, too.

RM: Thank-you.

AB: Yes, indeed.

RM: There you go.

AB: It's been a real pleasure and we'll get back to the interview again as soon as time permits.

RM: Thank-you, Dr. Best.

AB: Okay. (37:35)