| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #171 | |

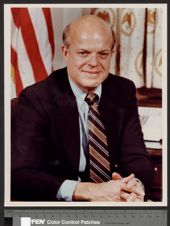

| Professor John P. East | |

| October 1, 1979 | |

| Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Dr. East is a political science professor from East Carolina University. Dr. East has been active in the Republican Party, candidate for Congress and for Secretary of State and is presently National Republican Committeeman from North Carolina.

John P. East:

My interest in politics would go back to high school, when my principal subject interest was history, politics related matters. I always did well in those courses, liked them. My interest simply began, I think, there. My mother always had a great interest in politics and followed them carefully, my father less so. My mother's father and brother had been mayor of the town they lived in in Illinois, a small town in down state Illinois. So, I suppose perhaps from that side of the family, there might have been a little inherited interest in politics. It began to come out in terms of my interest in high school studies. In college, I majored in Political Science and minored in History and my interest continued to grow. I first voted in 1952, supported Eisenhower and I suppose at that time I became interested in the Republican Party.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you in high school and college?

John P. East:

I was in high school in the state of Illinois--Springfield, Illinois--and in Bloomington, Illinois. Those were my high school years, so I was born and reared in Illinois with considerable time spent in Indiana and Michigan. I was a mid-westerner

primarily in terms of being born and reared in that general area. The time I spent in college--I graduated from Earlham College, which is a Quaker college in Richmond, Indiana. I continued my interest there as a major in Political Science, following politics, attended mock political conventions. I remember the first one I attended was in 1952 and I attended the Republican mock convention between Eisenhower and Taft. I was an Eisenhower supporter.

I graduated from college in 1953 and went into the Marine Corps, so I had a bit of a break there. I contracted polio when I was in the Marine Corps., which put me in the hospital for a year. When I got out of the hospital, I went to law school and graduated from law school at the University of Illinois in 1959. I went to Florida, wanted to get into a milder climate, passed the bar exam, practiced law for a year in the state of Florida. I was generally just not that happy with law practice. I went to the University of Florida and got my MA and Ph.D. in Political Science and came here to East Carolina in 1964. My political activities in Florida were then very minor, because I was doing law practice for one year and spent a lot of time just getting started and then, of course, graduate school, that limited my time for any active work.

I came here to East Carolina in the summer of 1964. The Goldwater Campaign was going on. I was, by then, very strongly Republican. I was a strong supporter of Goldwater. I worked on his campaign here, having been here just a few months, of course. I came in July. I became acquainted with a young man, Bill Dansey, who was very active in working on the Goldwater Campaign. In 1965, when the incumbent congressman in this area--Democrat--died, Herbert Bonner, this opened up that contest in special election, which is a very heavily Democratic area. Bill Dansey and some other

people came to me and asked if I would consider running. That sounded interesting and exciting. So, I ran for Congress in special election in February of 1966. I ran, ultimately, against Walter Jones, the Democrat who won the election. We did extremely well, about 40% of the vote, which is extremely well in terms of an historical record. We ran then again in the general election in November of 1966 and I had about the same percentage of votes, but we lost. Of course, by then, Jones had been in from February to November. I remained active in the local party and the state party. In 1968, the Republican candidate for governor, Jim Gardner, asked if I would be the Republican candidate for Secretary of State, against Thad Eure. Gardner ended up running against Bob Scott. Gardner ran a very strong race and ended up with about forty-eight percent of the vote. I got forty-four percent of the vote in 1968 against Thad Eure. That race was nowhere near the heavy commitment of time and resources that we had put into the congressional race. We were basically putting the name on the ballot and I went around a lot with Gardner to affairs, but it was not an organized or highly funded campaign in any sense of the word.

In 1968, I also was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Miami. I was a Reagan supporter then, as opposed to Nixon, and, interestingly, the North Carolina delegation, made up of twenty-six delegates, we gave sixteen of our votes to Reagan as opposed to Nixon. The balance, that is the remaining ten, went to Nixon with one going to Rockefeller. North Carolina, that year, was the only state outside of California which gave the majority of its votes to Reagan, outside of California, the only state that gave the majority of its votes to Ronald Reagan outside of California was North Carolina. Of course, Reagan lost the nomination, Nixon got it. Then in the general election in November, as I said, Gardner lost and I lost. I remained active in the party all along, the

local party and the state party. In 1972, Gardner attempted to get back into politics, ran against Jim Holshouser and lost in a very close second primary. That tended to end Jim Gardner's career in state politics. I strongly supported him. Jim Holshouser ended up being the Republican nominee for Governor and Jesse Helms ended up winning the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate. I supported Holshouser and voted for him. I was not active in his campaign, somewhat coming out of the earlier divisions. I was not as active as I certainly would have been in the Gardner campaign. I was a very strong supporter of Helms. Helms won and Holshouser won, which of course was a great shot in the arm for the Republican Party and I, again, continued active in it.

In 1976, when the Republican National Convention was beginning to take form in terms of delegate selection, I was still a supporter of Reagan and of course, his strength was growing at that time. President Ford was in office. Senator Helms was for Reagan. I had written Senator Helms, of course, I knew him. I told him that we were early in the game that if he decided to go with Reagan, I certainly was going to go with him and I thought it would be a good idea. Tom Ellis, his chief campaign advisor was very strong for Reagan, so we began to get some very strong divisions in the party then, the Helms/Reagan people v. the Holshouser/Ford people. That was a very fascinating, but a very divisive period in party history in North Carolina. Reagan had not won any primaries until he got to North Carolina and it looked like his campaign would maybe flounder here, if he couldn't win against Ford. It turned out that Reagan won this primary in North Carolina, against Ford. It was the first one that Reagan had won and it tended to turn that campaign around. In other words, it put new life in it. Helms' stature grew because of that. Holshouser's suffered a bit, because it was Helms, the Senator v.

Holshouser, the Governor. That primary was in May of 1976. Shortly thereafter, Senator Helms asked me if I would be interested in considering being Republican National Committeeman for North Carolina. I told him that I would be very flattered to do that, because they were interested in supporting me if I would do it. So, at the state convention that year, we not only picked delegates to the National convention and I was picked as a delegate and the Helms people had, of course, organized very strongly to ensure maximum delegate strength. I was picked as an at-large delegate and I also then I was elected at the Republican state convention as Republican National Committeeman for North Carolina.

After that convention was over, Tom Ellis, who is Jesse Helms's main political manager and political confidant, he called and asked if I would serve on the platform committee. I told him that I would be happy to. He said he thought it was essential that I go to work drawing up major planks for that platform. I told him that I thought that undoubtedly the Reagan people would be doing that, wouldn't they? He said, “No, we know they're not going to make any platform fights. I think it's a mistake and I think we ought to do something about it.” I said, “I agree with you,” so I spent a good part of the summer, prior to the convention, well a couple of weeks, working pretty steadily, day and evening, drawing up major platform planks that we thought ought to go into the platform. We went out to Kansas City, met early in the game with a number of other people from around the country that Ellis had organized. He shared our concern and I went over these platform planks with these people. We distributed copies, got their interest and consent. We then, of course, were assigned to various sub-committees on the platform committee. The platform committee was meeting a week before the convention itself. There was a

lot of national publicity at that time, centering around the platform committee, because of the strong contest between the Reagan supporters and the Ford supporters. This was really the preliminary skirmish to see who had the most strength and also, quite candidly, we were attempting to show the weaknesses in Ford's policies, domestic and foreign. We had mixed successes with it, one difficulty being, of course, that the Republican National Committee, which organizes the Convention is under control of the incumbent president. So, it meant, that on every committee, and also in terms of the platform committee chairman, who was Governor Robert Ray of Iowa, that the Ford forces enjoyed an advantage to begin with, in terms of predominance, in terms of being able to initiate proposals. We won some and we lost some and we ended up with a platform that was generally, in retrospect, by the media and others, considered a very strong Reagan platform. That is, it had rather strong conservative overtones to it in terms of domestic and foreign policy. Probably the most fascinating thing coming out of the convention aside from the very close race between Reagan and Ford, in terms of what I could see, Tom Ellis and Jesse Helms played a very crucial role in that convention. They are both very strong-willed, dedicated men.

Ellis is one of the most hard-driven men that I know. He is a very dedicated man. He is always looking for new opportunities and pushing hard. Ellis became very much disenchanted with the Reagan people when Schweiker was picked as the nominee. That was done without consulting with Senator Helms and with Tom Ellis. They both felt that they were wronged on that, because both the men had been early out supporters of Reagan. They had turned his campaign around in North Carolina. They were not consulted on the Schweiker move at all. They were simply told about it as a fiat

accompli, which greatly chagrined them, not surprisingly. They never quite have forgotten that, which to some degree would account at the present time--that is now, 1979--for Senator Helms taking a rather detached view in terms of the Republican National Convention coming up in 1980. Tom Ellis is rather candid that he felt, in retrospect, that he got in too soon and he has learned that there are advantages of waiting and seeing what the candidates do, what their positions are, and what they're going to do in regards to vice-presidential choices. That caused an estrangement at Kansas City and since then, between the Helms/Ellis campaign organization--the Congressional Club, as it is called in North Carolina--and the National Reagan forces . . . very strong antagonisms there, that one must appreciate and they are strong and deep. Tom Ellis has never made any bones about his dislike, for example, for John Sears who headed the Reagan campaign then and is one of his top campaign advisors at this point.

My interest then in politics goes back a long ways and has grown rather slowly with fits and starts. I would say right now that it has been about as interesting as it can be and maybe it will get more interesting since there is a very excellent chance that I will be the Republican candidate for Senate in 1980 against Robert Morgan and I will be doing that at the great urging of Senator Helms and of Tom Ellis, which would clearly give the opportunity, I think, for a very competitive and a very exciting campaign.

Donald R. Lennon:

Personally, aren't Helms and Morgan good friends?

John P. East:

This won't go out, will it? It's between me and thee?

Donald R. Lennon:

I can either turn this off or . . . These oral history interviews aren't publicized. What we do is to transcribe them and put them in typescript form and then the individual can edit out anything he wants to edit out or restrict anything for a period of time.

John P. East:

Well, as you can appreciate, at this point where you're right on the crest of current politics, I could be more confidential with you a year from now.

Donald R. Lennon:

This will not be released until you're ready for it to be released.

John P. East:

That way we can be candid and you can protect my confidence.

Donald R. Lennon:

In fact, we won't even transcribe these for some time.

John P. East:

It is true; Senator Helms and Robert Morgan were and are close. In 1974, for example, Senator Helms did not even campaign for the Republican candidate for the Senate, William Stevens, who was the son-in-law of J. E. Broyhill, a former National Committeeman. Though, Senator Helms would say, “I was never asked to do it.” William Stevens was very closely identified with the Holshouser faction, needless to say, and Holshouser did travel around and campaign for him. Senator Helms, at that time when asked if he was involved, he said that he looked upon both of them as good friends and really felt that he could not or ought not to be directly involved in it. That did disgruntle some more traditional Republicans, particularly from the west. They thought that Helms had not been as supportive and helpful as he might have been. In 1978 when Senator Helms ran for re-election, it is true Robert Morgan did not go out of his way to campaign for John Ingram, the Democratic candidate. It is true that the public impression has grown, and understandably so, that Morgan and Helms are very close personal friends and, to a degree, political friends and therefore, each is not going to do anything of any consequence to undercut the other.

So, that brings us to this interesting phase in the political situation. I don't profess to speak for Senator Helms. Obviously, he can speak for himself. I can only go on the basis of brief conversations that he and I have had and meetings we have been to and the

interest of Tom Ellis in this campaign. Senator Helms is extremely positive on my running and the endorsement will be there and support will be there. One might speculate, I suppose, in terms of the historical record, why the change? Of course, Senator Helms would be the best one to answer those questions. I could give some thoughts I have on it. Senator Helms has been in the Senate, a strong supporter of certain key items, for example, the Panama Canal Treaty. On a number of these very key items, Robert Morgan has gone the other way or, as the Helms people might see it, undercut him. I suspect the Panama Canal issue was the crucial one, because that was a very close vote.

Donald R. Lennon:

A very emotional one.

John P. East:

A very emotional one. I think it is important to recall that Helms and Ellis are both men who got into politics, as they would see it, from a very principled conservative position and, of course, one makes concession to political realities to a point. Their feeling is, I suspect--I cannot say this categorically, I'm only talking as an advisor and one that is getting a feel for the situation--they feel that Robert Morgan has forfeited because of his stand on a number of crucial issues, such as the Panama Canal, has forfeited the tacit support that he, in the past, has gotten from Senator Helms. This is not to say that Senator Helms will be out running a very negative campaign against Robert Morgan. That would not be done. He wouldn't do it and nor, frankly, would it be politically wise to do it. I think what is new and novel this time is that his endorsement will be there and the support of the Congressional Club will be solid and substantial. I think this would definitely up the odds and the change the complexion of the potential campaign in 1980 as regards to what it was say in 1974. So, on your question, Helms and Morgan being

friends, I can clearly discern that the political friendship has eroded. I'm not saying the personal friendship has, but it's clear the political friendship is eroded, to the point that it should substantially alter the nature of this campaign in 1980.

Donald R. Lennon:

It is obvious, of course, in recent years, that Morgan has taken more liberal stances, quite a deviation from his 1960-1964 Beverly Lake period.

John P. East:

Excellent point. I wouldn't bring in this little bit, only to show the changing attitudes on Ellis. Ellis is a former Democrat and so are Helms and both were very strong Lake supporters, and as you are aware, I. Beverly Lake, Jr., is contemplating very seriously and definitely will change parties and run as the Republican candidate for the Senate. This is a part of that tradition, too, the unhappiness with the Lake people--the former Lake people, I. Beverly Lake, Sr., supporters--with Senator Morgan, who was the campaign manager for I. Beverly Lake, Sr., subsequently disavowed that or put himself at arms' length from it and that was the beginning of the erosion, the estrangement. Then recent events as you are rightly suggesting have simply accelerated the pace.

Donald R. Lennon:

To go back to the early part of your interview to your background in Illinois, as you have said from the Goldwater period on, you have been with the conservative branch of the Republican party and, if memory serves me right, there is a fairly strong liberal branch of the Republican party in Illinois is there not and other parts of the country? Growing up as a Republican was your conservatism a result of the Goldwater period or were your roots in the Republican Party in Illinois of a conservative nature?

John P. East:

Well, my roots in the Republican party of Illinois would really be nominal, because I was born and reared there, by reared, that is, I went through high school and I went away to college in Indiana. Then, I would, of course, come back home to visit. I

really was never active as a Republican in the Republican party of Illinois. I did not become politically active in a party until I came to North Carolina. I had been an Eisenhower supporter as opposed to a Taft supporter, which might have suggested a earlier period of a greater identity with the more moderate wing, as it might be called, as opposed to the conservative outlet. My objection to Taft at the time, I thought he was rather isolationist in his attitudes in the Marshall Plan and on NATO. I thought he was rather naive about Soviet intentions in Europe and represented too much of the old isolationist spirit of the Republican Party. I didn't share that and I looked upon Eisenhower as someone who more closely understood the international implications of the Soviet challenge in the Post-World War II period. I think that, more than anything else, accounts for my difference at that time.

I did have two teachers at Earlham, one had been a former president, who was a conservative Republican, was a Harvard Law graduate and former president of the institution. He was a man I came greatly to admire, because of his political principles, which were conservative. Though interestingly, he was a Taft supporter and I ended up supporting Eisenhower. I greatly admired him. His politics were conservative. This was at the time Bill Buckley was getting started, God and Man at Yale--I remember reading that in college--and this professor thought a great deal of Buckley. I think things began to grow from that very formative period in college and there, of course, could have been other contributing factors, but it would not relate at all to any party activities in Illinois. So, we could separate those things.

The Republican Party of Indiana at that time, which I really was more familiar with--this was the period of Capehart and Jenner, which was obviously more

conservative. I repeat, I was not active there, although one time I did hear Bill Jenner make a speech at a rally. I remember him holding up what he called a Truman dollar, which had shrunk to pretty small proportions. I remember that as a little folklore of Indiana politics at that time. It was in Florida and increasingly when Goldwater got the nomination, that I--it was not really a dramatic thing, I was just moving that way--I became much more enamored with the conservative leadership in the party via the Reagans, the Goldwaters, as opposed to what one might call a more moderate or central or liberal wing to the party. I suspect in my case, it's perhaps a more philosophical kind of thing than a purely pragmatic one.

I have, though, as a matter of political involvement and activity, always managed to have good relationships with the other elements. That's been true of North Carolina. I've always had cordial relationships with the Ford people and the Holshouser people. On the National Committee, I've developed some very good close personal friendships there, but no question about it, I am known as a Reagan-type conservative associated with Helms and I'm not troubled with that or embarrassed with it. I am very happy and comfortable with it and it has simply grown that way over a period of time and maybe goes back primarily to my college years with this professor and my interest in Buckley, which has grown since then.

Donald R. Lennon:

Running for office in North Carolina, both for Congress and for Secretary of State, and being involved almost continuously with the campaigns even when you're not a candidate, in a state such as North Carolina where the Republican party has only tasted victory on scattered occasions, is it not somewhat frustrating to work against the odds?

John P. East:

It is. It is. I think it comes back to a person who is more consciously conservative in his approach to politics, foreign and domestic, and a feeling that to work within the Democratic Party, to support its candidates for president or any other office, vis-á-vis the Republican, just is philosophically unacceptable. To that extent, you tend to define yourself out of the Democratic Party and in this state and its impact on the national politics. So, that leaves you in the more fragile position in the minority party, the Republican Party. It does hurt. Though, I suppose, one might look at it this way, if we were in the Democratic Party and attempted to run as more definitive conservatives, we probably couldn't survive Democratic primaries in terms of the general composition. Statewide races would be very difficult and even more localized races might be difficult. As we would view it, that is, we of a more conservative stride in the Republican Party would view it, we're driven by the circumstances of events in the Republican Party. The victories are fewer, but they're sweeter, as we would see it at any rate. The Reagan primary victory is a great accomplishment. The Helms victory in 1972 and 1978 is a great accomplishment. Helms has a great impact and an increasing impact in the Republican Party and on the national scene generally. These are the comforts that we have and perhaps we take solace in the idea that we are maintaining our principles intact and that is basic and fundamental in politics and we haven't sacrificed in terms of momentary gain. I agree that there's always a peril there of getting a little overly self-righteous. It's true with myself and many who would be of my stripe, that we like to think, at least, that the principles come first, the party victories come second. We would like to put both together, but we're willing to settle for fewer victories in order to keep the principles intact.

Donald R. Lennon:

I noticed that you spoke of the Helms victory in 1972 and 1978 as being sweet solace. You didn't mention the Holshouser victory in '72.

John P. East:

I would certainly include that, no question about it. What made me perhaps more emphasize the Helms is the conservative matter. No question about it, I was delighted with his victory and I see Jim Holshouser frequently and talk with him and we have a very cordial relationship. I think he would say of all of the strong Gardner inner group, he had the best relationship with me as opposed to any of the others. I will say this, I have never quite agreed with the conventional political wisdom in this state that there were strong philosophical differences in the Republican Party in the state. Jim Holshouser is very basically a conservative man if you're talking about fiscal conservatism. He certainly is no softy in foreign policy or in defense. I think sometimes the alleged differences between the so-called moderate and conservative wing, is more imagined than real. For example, if you look upon James Broyhill and the Broyhill family as being a part of the so-called moderate wing, James Broyhill has a very high conservative voting record and his father has been a very conservative man. The differences, I repeat, are more imagined than real on a philosophical scale of rating. Yes, I was greatly pleased with Jim Holshouser's victory.

Donald R. Lennon:

Speaking of fiscal conservatism, if you go back and look at most of the Democrats who held office, held office of Governor, for example, prior to 1960, their conservatism would be just about the parallel of any Republican candidates brought forward, would it not?

John P. East:

I think you're right. I think what probably is the lode star, the north star of conservative Republicans, what really gets us in our trenches is national politics. We

appreciate that often state politics between two given candidates on state issues for the General Assembly, for example, or even for governor, the differences might not be all that substantial. But, we get our ire up on national politics and get frustrated with the tendency of Democratic governors and Democratic senators to constantly have to either avoid or apologize for national political figures such as Carter or McGovern or Ted Kennedy or whatever it might be. We feel that so much is at stake at the national level, that at least, though we have a rather minority status here, of course, needless to say, we do have some impact upon the national scene, either at national conventions or now and then getting a senator or a governor or a congressman. Again, that's good pay for what we're getting. The national scene, I think, is as crucial to conservative Republicans as anything is. They're deeply disenchanted with the National Democratic Party, whether it's a Carter or the potential of a Kennedy. This drives them ever deeper into the Republican fold on the theory that the Republican candidate for president is invariably superior, though maybe not their ideal choice, is invariably superior to the Democratic alternative.

Donald R. Lennon:

Here in North Carolina, would you feel that the Helms victories in 1972 and 1978, as strong as they were, reflects an electorate that is more conservative than the party they're a part of?

John P. East:

Perhaps you're suggesting that it is the conservative Democrats who are voting for Jesse Helms. It could be. There is no question about it that Helms has put together a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats. Whether that combination ends up producing a party more conservative than it would otherwise be, I'm not quite sure in that I find that the center of gravity in the Republican Party in this state, by any reasonable

definition of the word, is conservative. Some of its critics might think it is reactionary. As I would understand the terms, I would not say that. It is conservative if by conservative, you mean fiscal conservatism, disenchantment with big government growth, taxation, inflation, spending, the usual things we think of as riling conservatives.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was primarily thinking in terms of registered Democrats voting for Helms because of his conservatism, that the electorate is more conservative than the Democratic Party that they're registered with.

John P. East:

I think so. The electorate of North Carolina, on a scale of rating, is more conservative than the Democratic Party.

Donald R. Lennon:

In other words, if these people were actually with the party they were voting with, the Republican Party would probably be the dominant party.

John P. East:

We like to think that is so. We may, because it sounds good to us, like to believe that's so. I think American party activists always like to believe that the majority of the people would be with them, if they knew what the score was. The problem is, they don't know what the score is, so we must go out and tell them. I think there is validity in that. We work at an enormous disadvantage as everyone would know from that standpoint of the historical record, going back to the Civil War. We'd like to feel that if we didn't have that historical legacy to bear, we would be the majority party and that we are moving that way ever so slowly. But, for example, the proposed change of I. Beverly Lake, Jr., would be a symbol, maybe one of the most dramatic ones we've had of late, of that transition. Helms did it, but then Helms was not holding public office and did not have the political stature that say an I. Beverly Lake, Jr., would have. I think it is moving that way, but it's slow.

Donald R. Lennon:

Don't you have several major political families and here, I think, in terms of the Broughton family and the Smith family, two of the old line of conservative Democratic families that appeared to be closely tied with the Republican Party.

John P. East:

Yes, and interesting to note on that score that the widows and the grandchildren of those families, had campaign ads for Jesse Helms in 1978.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I was thinking in terms of and these have always been considered traditional Democratic.

John P. East:

Absolutely, and so Republicans look upon all of this as auspicious movement in their direction. It never goes quite as fast as we would like, but the trend seems to be there, ebbing and flowing. We do feel that Watergate set us back heavily. That put everything into a deep freeze, whereas prior to Watergate, there was that rather strong movement our way. Maybe it was not as strong as we thought it was or would like for it to have been. We felt it was going our way and Watergate put it on the shelf for the time being.

Donald R. Lennon:

I take it from what you said about the 1968 campaign that you were never a strong Nixon supporter during any period of his career.

John P. East:

I supported Nixon without any doubt in that election. I supported him very strongly. Also, I would note as a related point, in 1976, though I was a supporter of Reagan at the convention, I came home and was asked by the Ford people to be a co-chairman for the Ford campaign, which I was. So, I have been, to that extent, I suppose you might call it, a party loyalist. I did support Ford and had no trouble doing so in 1976 and I did support Nixon in 1972. But, it's true that my first choice was Reagan both times.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm going to get things out of sequence from what I wanted to ask, but I've been jumping back and forth anyway. Speaking of Reagan since you've commented on him several times, you mentioned the fact that there was a breach between the Reagan forces and the Helms forces in 1976, is that going to hold over to 1980?

John P. East:

It's so difficult to answer now, because so many things can happen between now and next summer. On the basis of what we know now, the first of October 1979, I suspect that eventually, with the current crop of candidates and the relative strength they're showing, if that holds up, Reagan should get the nomination. There certainly would not be any problem that Senator Helms would support him and support him very strongly and wholeheartedly. I think that what will not occur is the tremendous effort in the North Carolina primary unless the Reagan forces make a very concerted and successful effort to get Senator Helms and his organization to back them. To this point, I do not see evidence of that. I do understand that all of the presidential candidates have approached Senator Helms, because he does have a strong national following. They've approached him and, courted him, I guess might be the right word, but to this point, he has not made any commitments. All of this could change by May of next year, where he could become more active in a primary. Or, it might be that he would not become involved then, but would take a more active role conceivably at the National Convention, which is going to be held in Detroit.

Donald R. Lennon:

You don't think that Reagan's age is a factor?

John P. East:

Age is the single biggest problem Ronald Reagan has. The next question is, can he overcome it; is he overcoming it? I think so. I heard him speak last May at the Republican state convention and had the pleasure of sitting at the table with him and

Reagan, in operation, overcomes that barrier. He strikes me as a youthful, vigorous, healthy, fifty-six or fifty-seven, which is a good age. Reagan has the vigor and the strength of a man ten years his junior. But, it still remains as an issue.

Donald R. Lennon:

The pressure of the office at this point in time is such that . . . .

John P. East:

It could be. I think it could be translated into possibly an issue against him. For a moment, I wouldn't say it is not a problem and could not turn out to be a political issue. It's his single biggest weakness. I do think to this point, he is overcoming it. Whether he can continue to do that in primaries in the future or in the general election, is a question mark.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looking back to Jim Gardner's involvement in politics, in his campaign for Congress and then for governor, Gardner, more or less, came out of nowhere politically, did he not? He was a successful business man and if I remember correctly, ran against a long standing and very prominent, very popular Congressman the first time around. He was unsuccessful in his bid and came back two years later and succeeded in a fashion that no one within either party had been able to do against Harold Cooley. Cooley had been in office for fifteen or twenty years by that time. Any thoughts or comments on that particular period of the campaign--you were in North Carolina then for both of those elections--as to Gardner's style or campaign techniques? How did he manage to pull that off?

John P. East:

I think anyone who had close contacts with Jim Gardner, and I had extensive contacts with him then and I still know him as a good close personal friend and see him quite frequently. Jim Gardner, in my judgment, was one of the most talented campaigners and speakers that I have known in my political activities. He had great

drive, a handsome man, a likeable man, had charisma in the very best sense of the word, and was an outstanding speaker. He was an outstanding stump speaker. I think what he managed to do was to take those things and coupled with his business successes, which gave him good financing, managed to put that together and run against a man . . . . Actually, Cooley, if I'm not mistaken, had been in Congress thirty-three years at that time and was chairman of the House Agricultural Committee. Gardner managed to turn his age, his charisma, his style, to his advantage, against this older man, accusing him of sort of taking things for granted and sitting at the switch. Gardner gave out the impression that there would be a new age, a new zip, a new momentum. I think he capitalized very well on that mood that John Kennedy seemed to captivate well; “Let's get things going again. Let's get things moving again. They're stale and we're not doing as well as we ought to be able to do.” Jim, of course, was running . . . . Nash County was really the far eastern part of that district, in terms of its rural. Then, as you're aware, it went on in including Wake County and Durham County and there you had this growing professional middle-class people. A lot of outsiders had come in and I think one could say it had become more urban and they could identify with this young successful businessman. He was a native North Carolinian. He'd been a former Democrat. He had changed parties, so he was socially and culturally acceptable. Coupled with his unique talents, he pulled all that together, and set himself apart from what appeared to be a rather tired old gentleman who wasn't doing very much and was taking everybody for granted. That's the image he gave of Cooley, that he was pompous, arrogant, had been sitting up there enjoying the perks of power and had forgotten the people down here in the fourth district. He had great talent for doing that and he had the financial resources to get the message

out and things had changed enough in terms of the political climate . . . that's how he pulled it off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think he would have been better to have gone back and tried for a second term rather than after one term trying to move toward the governorship?

John P. East:

Yes, except, in defense of Jim, his problem was that the State Legislature took Nash County, where he lived, away from him, and put it in the second district against L. H. Fountain. That was a hopeless task. So, he either had to leave Rocky Mount and move to Raleigh or else run against L. H. Fountain. Jim and his wife are both from Rocky Mount. She is from the Tyler family and they have deep roots there. Marie Tyler has never liked politics. She's never understood it. She is a very charming and delightful person, but would never care if she never saw another political rally or went to one. Jim was always very solicitous of her and his family and their respective families. He really was at a very crucial crossroad there. It was either give it up and do nothing or move to Wake, which was out of the question, or to stay there and fight it out with L. H. Fountain and that seemed out of the question. So, he chose to enter the governor's race and came very close in that race.

A lot of people felt he had lost of it, because of the group of us who supported Reagan over Nixon. Nixon had a lot of support in the state and he got the nomination and a lot of the Western Republicans resented that. They looked at the Reagan supporters as a lot of the more new guard Eastern conservative Republicans and they resented that. Gardner did not get the support from some of the Piedmont and Western Republicans that he should have. That could have been the margin of difference. If Jim had stayed active, unfortunately, between 1968, he was quite embittered after that campaign. He felt that he

had not gotten the support from the Piedmont and Western Republicans that he should have. He underwent some severe financial strains of his own as a result of the campaign. He did not, between 1968 and 1972, attend Republican functions, like the Republican state conventions. This irritated some people, even some of his former supporters. So then when he decided to get back in in 1972, he had allowed an erosion of his power, his strength and Holshouser just narrowly beat him. If Jim had stayed active, he would have beaten Holshouser. Of course, we don't know that the scenario would have been the same. He might have gone in and won the governorship in 1972. He should have persisted another four years and I think he might have pulled it off. I think he would have beaten Holshouser in the Republican primary and I think he might have very well beaten Skipper Bowles, too, and that was the McGovern campaign. I think Gardner would have been in a unique position to have won that year as Holshouser did. He might have even won bigger, the same year Helms won.

Donald R. Lennon:

But he dropped completely from politics after 1972.

John P. East:

Completely, completely. Everybody knew him. He was conspicuous by his absence at the state conventions, because he was still had an enormous personal following in the party.

Donald R. Lennon:

Does that point more . . . and I'm just asking this without any malice or forethought on my part. Does this point to a lack of real interest in the political process and more the image of an opportunist, who was just in the party for what he could get out of it personally?

John P. East:

No, not at all. I think what happened was, Jim had put an enormous amount of effort into that campaign. He really had been campaigning full tilt from1964, when he

first ran against Cooley and then he won two years later. He had been successful in business. He had won the Republican primary big against Jack Stickley in 1968; he got 74% of the vote then. He went down to the convention in Miami, was head of the North Carolina delegation and supported Reagan. He was one of the seconding nominating speeches for Reagan. So, there was a lot of momentum going for him and then he came back and put a tremendous amount of personal time and wealth into this campaign and did not get the support he felt that he ought to have gotten from some of the Piedmont and Western Republicans. He came out of that campaign, with that very close defeat, bitter, bitter. He had some campaign debts that he had to get paid off and there is always the enormous letdown and disillusionment of losing a political campaign. It's kind of hard to describe. I think younger men, who have not had the experience, it hits them harder. They don't quite have the perspective that defeat can come and its pangs are real. Jim had always enjoyed successes until then. He had not been a loser in business or politics. So, out of it, came a temporary period of bitterness and disenchantment.

Donald R. Lennon:

You say the Western Republicans, was this the Holshouser people who failed to support him in 1968?

John P. East:

He felt they did not support him: the Broyhills, the Holshousers, that whole entourage of Western Republicans, the more traditional, the Charlie Jonases.

Donald R. Lennon:

They looked upon him as an upstart.

John P. East:

As a prize, an upstart, that's right. They particularly resented, at least they used that as a. . . . You see, he beat their candidate Stickley. He beat him soundly and then he went down to Miami and supported Reagan when they supported Nixon. So, they looked upon him as a brash upstart and he felt, dragged their feet badly; didn't contribute to the

campaign, didn't work for them, maybe some didn't even vote for him, not that they voted for Scott. They just didn't vote. These are the kind of Republicans that would never vote for a Democrat. Disenchantment. He brooded with that until 1972, when people said, “Jim, get back in. This is a good year.” He got back in, but by then, his political opponents were able to peddle the argument that he didn't seriously help the party. It was more Jim Gardner, more opportunistic and his having sat out for four years, accounted for it. In defense of him, his motivations were bitterness, not opportunism.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looking to the 1972 gubernatorial campaign, don't you feel that in many ways, the greatest friend and ally of Holshouser in that victory was Skipper Bowles?

John P. East:

I think so. As you know, it was Nixon, McGovern and all of these things, Helms against Galifianakis, all of these things worked . . . . Republicans feel that way--that Holshouser was pulled in by the weight of the top right--and including certain deficiencies in Skipper Bowles himself.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is what I meant. Bowles mismanaged his campaign, he overspent. He left the impression that he had money to burn to do whatever needed to be done to buy the election and all that. He caused many people to vote Republican that would have voted to do it to split their ticket otherwise.

John P. East:

That's right and I think Skipper Bowles showed that television is a two-edged sword and there was overexposure, the feeling that it was a little too smooth, a little too slick, too cosmetic. Holshouser came through as somewhat the earnest underdog and a man you could trust, a moderate man of intelligence. Maybe this was the time for a little cleansing. I think he picked up an awful lot of independent Democrat votes that way, not just conservative Democrats, but what you might call more independent, moderate,

centrist Democrats, who for various reasons, thought that Bowles was not quite the man. I agree. Bowles was not a strong candidate.

[End of Part 1]

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #171 | |

| Professor John P. East | |

| Greenville, N.C. | |

| October 15, 1979 | |

| Interviewer is Donald R. Lennon | |

| Interview #2 of 2 |

John P. East:

As far as the 1976 convention goes, I first became involved in it when Senator Helms and Mr. Ellis asked if I would be interested in serving as Republican National Committeeman for North Carolina. That Mr. J. E. Broyhill, of the Broyhill Furniture Company, whose son James is a Congressman from the western part of the state. . . His [Congressman James T. Broyhill] father [Mr. J. E. Broyhill], because of age, was stepping down and he'd been National Committeeman for twenty-five years, so there was an opportunity to fill that slot. They asked me if I would be interested in doing that and I told them that I would.

They had been organizing things very carefully, because of the conflict in North Carolina between Reagan and Ford. They had won the primary, which had turned the Reagan campaign around, nationwide. Then they began to focus on our summer convention, which was held in Greensboro. So, after the primary and prior to convention, they had asked me about this National Committee post, if I would be interested. I told them that I would be delighted to do that. So, the struggle went on throughout the

counties and in the district conventions throughout the state to get delegates to go to that state convention. The Reagan/Helms people, of course, had the momentum of winning the primary and they also had the momentum of the very effective work of the Congressional Club, getting out and organizing. So, they clearly came up with delegate support at that state convention. It was overwhelmingly pro-Helms and overwhelmingly pro-Reagan. It left Governor Holshouser and the Ford forces clearly in a minority position, because, as you may recall, at the state convention, when they finally picked their delegate group, the delegates to go to the National Convention in Kansas City, the Governor was not picked, nor was Congressman James Martin, who also wanted to go. Both of them were Ford supporters. It was not any convention hostility to them as people, but it was a feeling that every vote counted and at Kansas City, it was really going to be tight and you just couldn't afford the luxury of giving up any delegate, including your own governor.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine this increased the hostility between the two camps, did it not?

John P. East:

It did, no doubt about that. Not so much in terms of Helms v. Holshouser in a public way, but in terms of the competing armies, so to speak. Of course, the media, understandably, made much of the point, suggesting that Helms was being very heavy handed and trying to dominate and control. Of course the Reagan supporters and the Helms supporters were contending that if the thing had been reversed, they would not be gratuitously lavishing the other side with delegates to the convention, two or three or four or five. It was a luxury, if we were serious about this thing, that we couldn't afford to do. So, at the convention, I was picked as National Committeeman and had no opposition. Then, I was also picked as a delegate, one of the at-large delegates. They had

been picked at the district level and then there were a few, a minority of delegates, to be picked at the state convention and I was one of the at-large delegates picked. Not long after the convention, the delegates were then to meet and select a chairman. It was clear that Ellis wanted to be chairman and would be chairman, because they had done their work and they had the organizational strength. Ellis called me several weeks before we were to meet in Greensboro at the Albert Pick Hotel. We were to meet the delegates in order to organize and pick the chairman and make appointments to various committees that would be at this national convention in Kansas City. Ellis called me and asked me if I would be willing to serve on the Platform Committee along with Betty Lou Johnson, who was the new National Committeewoman. I said that would be fine, I would be delighted to. A little while afterwards, I got a call from Attorney John Wilkerson, who is a well-known attorney down in Washington and very active in the Republican Party and a good friend of mine, a close political associate. He had called Ellis and indicated that he wanted to go and then he called me and was indicating that it might be rather difficult and tiring for me out there, in terms of getting around. I liked John. I didn't argue with him. I told him that it really made no difference to me; whatever the group wanted to do was fine with me, whatever Tom Ellis wanted to do. I called Ellis just to get his thinking on it and he was very categorical that he wanted me to do it. He did not want John to do it. He said, “I would like for you to stand firm and offer yourself to do it.” I said that was fine. So, we went through with it. I was picked to serve on the Platform Committee.

Ellis thought the Platform Committee would be important, because a lot of Republicans tended to gravitate to Ford, not so much out of principal and issue, but because he was the incumbent president. Ellis thought we could bring them up short by

showing that they were sacrificing an awful lot in the way of principle and issue in order just to back the incumbent president. They needed to tweak their conscience a little bit. After the Winston-Salem meeting at the Albert Pick, he called me one day and he said, “I would like for you to draw up some platform planks for us,” or in effect, draw the platform and work on planks for it. He asked, “Would you be willing to do this?” I said, “Well sure, but is not the Reagan staff doing that?” For example, Martin Anderson, who is still the big issues man with Reagan, who teaches Political Science at Stanford. I said, “They must be doing that, aren't they? The national staff, they aren't just leaving it to happenstance.” Ellis is a very outspoken fellow. He said, “They're not doing anything. Apparently, they just want to cakewalk through out there and soft shoe it and see what they can come up with.” Ellis is a very dedicated man on his principles and issues and he felt that was not morally defensible, and he also didn't think practically that it would make sense, that you needed to flush these people out on the issues, to show the weakness of Ford. I said that I would be glad to.I started to work on that during that summer of 1976, before the convention. Interestingly, Ellis did not say . . . . Sometimes people have the impression that Ellis is a very dictatorial fellow. He didn't say anything to me. He didn't say let's have a plank on this or a plank on that. He totally left it up to me to do whatever I wanted to do. I presume he felt, from his standpoint, I would do the right thing, I don't know. But he never gave me a catalog of anything to do and I've always had a good relationship with Ellis. He's well organized. He knows what he wants to do. He fills vacuums. He does like to coordinate, organize, but I've never found him personally offensive in the sense of telling me to do something I didn't want to do or dictating or anything of that kind.

We've had some differences of opinion on strategy and tactics and sometimes we just left them unsaid, sometimes we discussed them. But, I've never had him dictate to me that I needed to take a policy position that I didn't want to take.

All right, I told him that I would be happy to do that. A couple weeks later, I got a call from Carter Wren, from the Congressional Club, saying that they were convening a group of Southern delegates to the National Convention in Atlanta and wanted me to go down and be part of the program to talk about issues. I said, “That's fine.” They arranged for me to fly from New Bern on Piedmont down to Atlanta. We went down to one of the nice hotels there. I've forgotten the name of it. Anyway, delegates came from all over the South and the Southwest. For example, Ray Barnhardt, who was chairman of the Texas delegation, was there. A number of the Texas people were there, the Oklahoma people, the Georgia people, the Florida people, the Virginia people; the entire Southeast and a little bit of the Southwest. Also, the Reagan people sent, because they were invited to present people they wanted to, they sent Lynn Nofsinger down, who was Reagan's chief confidante. They sent David Keene, who was the southeastern regional coordinator for the Reagan campaign down. They sent one or two other fairly high level people in the Reagan staff, Nofsinger being, of course, the most important one. They attended the meeting and it was a rather heated meeting, between Ellis and Nofsinger and these Reagan people, on this question of what they were planning to do in order to really jar the Ford forces in Kansas City. How were they going to shake delegates loose? Ellis still felt very strongly on the platform, for example. He felt we needed to do something and he knew they weren't going to do anything. He felt they were conceding too much to Ford forces in other states. They weren't really playing hardball. They were playing the game

too soft and too gently and they weren't going to win it. They needed to make up their mind of what they were going to do. Ellis was very caustic in his attitude towards them. Some there at the meeting, felt he went too far, but Ellis is abrupt, as his critics would say, even abrasive.

I was in on the program and I did discuss issues, which was well-received. The Reagan people were very cordial. They didn't question anything or attempt to deter me from anything and I didn't make any effort to bait them. I didn't say, “They're not doing it. We're going to do it.” I simply said that we in North Carolina thought it would be appropriate to bring up issues and try to get them into the platform and didn't suggest anyone else was being remiss on their obligation. That went over well in terms of just talking about my own participation in it. I met Nofsinger and we had a good relationship and David Keene. I still know David and Nofsinger and corresponded with them, talked with them and it's always been a very cordial and friendly relationship.

Atlanta, then, was very tense between Ellis and the Reagan national staff.

Donald R. Lennon:

What type of thing was Ellis, in particular, disagreeing with them on?

John P. East:

He was disagreeing with them that they were . . . . It's a little difficult for me to remember all the details . . . One, on the platform. He didn't see that they were making any big push there. Then again, he had noted in Arizona, they had allowed John Rhodes to go as a delegate and he didn't see why, because Rhodes was for Ford. They said, “Well, you can't keep the Minority Leader from going.” Of course, Ellis's point would be, “Well, in North Carolina, we had to keep our governor from going. Are we trying to win this thing or are we not? What are we doing? We're behind. We need the delegates. You tell us we're out to win it and yet, we're acting as though we have things to give

away and we don't have things to give away. Either we're in it to win it or we're just playing games. What are we doing?” He thought from the very beginning, going back to New Hampshire, and this was being reflected down there, if I could maybe give a little background for it. He came to the meeting with a certain unhappiness with it to begin with. He felt they'd pulled their punches in New Hampshire; it was sort of a patsy campaign. They didn't really hit Ford on the issues. When they came to North Carolina, in effect, Ellis ignored them. He engineered that campaign in North Carolina, no question about it. You may recall that Helms hit hard on the Panama Canal issue and Reagan did. That was Ellis's idea. I know myself, at the time, when I first saw Reagan on local television in the North Carolina primary raising the Panama Canal issue, I thought, “My God, that doesn't strike me as terribly current,” but it worked. Ellis has very keen instincts on good juggler issues and this giving away, “They're going to give away the Panama Canal. Did you know that? If not, we're telling you about it. This is what is happening. You need to be alerted about it.” That was the approach that Reagan and Helms were taking. What it did, in North Carolina, I think Ellis's instincts were right, the North Carolina Republican Party is basically a conservative party, as we might define those words today. It still is and it was then. What Ellis was doing was making an appeal to those instincts. That would pull away Ford's support and it worked in North Carolina. He felt that once the North Carolina primary was over, they went back to their old ways playing patsy, patty-cake, that sort of thing. They weren't playing real hard ball. So, when he got to Atlanta, he was really fed up and was really, I think, taking out his personal frustration on these staff people, who basically just sat there and took it. They

did not confront him. They did not question him. They did not attempt to engage in public debate with him. That was somewhat of a standoff, I guess, you'd have to say.

Things just continued to fester with him. It wasn't long after that, you may recall, the word comes out that Schweiker is the choice of the Reagan people. This just sent Ellis . . . . He was infuriated with that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't that the worst possible strategy that Reagan could have used?

John P. East:

Well, from the Reagan people's standpoint, they were contending, John Sears, the head . . . and Ellis did not like Sears. Again, thought he was an opportunist and was not as dedicated on principle as he ought to be, that he was a typical professional political operative who didn't have a political principle in his body and would drift wherever the currents took you. I'm not really exaggerating Ellis's feelings on that. As I say, Tom Ellis is a man of great personal honesty and integrity, but everyone will acknowledge that he is pretty doggone specific when he talks about a given person. He is a man of strong likes and dislikes and if he likes you . . . . He's not quick to praise people. If he likes you, you can tell it, in that he isn't running you down too much. But, if he doesn't like you, he's very harsh in his appraisals and he was very harsh on Sears.

So, getting back to the Schweiker move, Ellis thought it was terrible, but Sears and the Reagan people thought it was imperative, because as they saw the vote count, they didn't have it as they were heading down the line to Kansas City. They had to do something dramatic to make an appeal to the moderate wing, the center wing, the liberal wing, or however you wish to go about this, that they needed to do something dramatic. Charlie Black, who is now very high in the Reagan hierarchy, now this year, 1979, at that time was working for the Reagan campaign. He had been, originally, with the Helms

organization in North Carolina. Supposedly Charlie Black, at least this was the rumor, put together this Schweiker thing along with Sears and a few others. They did not consult Helms; they did consult Ellis. They were presented with an accomplished fact and they were unhappy with that. They thought it was just a part of a long train of foolish moves, playing patsy, not consulting your real friends. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

It seems like Reagan would have called in a group of those major national figures that he was most closely associated, such as Senator Helms and conferred with them or at least told them in advance what he was considering doing, rather than . . . .

John P. East:

It's a good point. I don't know exactly what the answer is to that. It was my understanding that they felt it was such a bold move that the very fact of discussing it, could abort it, because you would get people who would say, “No, no, no, and if you do it, I'm going to do thus and so.” That it was better just to present everybody with an accomplished fact and then try to repair the damage. So, that, I think, was their feeling on it. Whether that was prudent or wise, I agree, one could debate it. But, it infuriated Ellis and Helms and I remember there was a large meeting not long thereafter in Raleigh, which Helms spoke and he made the point that he thought this showed that any man, even a man as fine as Ronald Reagan, was subject to mortal sin and error and that this is what had occurred. Man is always not far from failure and error.

Well, the divisions were really deep then. I went ahead and prepared the platform planks. We flew out to Kansas City. I flew out with Ellis and Carter Wren and Betty Lou Johnson and one or two or their aides--Carter and Tom's aides-- in July of 1976. I had all these platform planks I had finally gotten together and I remember on the plane, I handed them to Ellis and I said, “Here, do you want to take a look at this?” He said, “No, I'm not

worried about it.” Interestingly, he never did look at them. He never did. I thought he'd take them and go through them. I had communicated with Helms's office on one or two of them. The only time, and it was a very mild difference, was on an abortion plank. They were supporting a Right to Life amendment. I had taken a stance somewhat short of the Right to Life amendment. Anyway, we worked that out; there wasn't any problem. Interestingly, that's the only communication I had with Helms or Ellis. So, they were not directly involved in doing it. I really did it on my own. I think they probably assumed, which I guess was right, that I wouldn't make too many errors. I'm not saying I would do a perfect job, but at least I wouldn't be far off the reservation on the issues and the principles. So, I don't think they were worried about it. Of course, people get busy and they've got many other things to do.

We got to Kansas City and we met with a group of delegates that they had gotten names of. I don't know exactly how they got them, but very conservative Reagan supporters from throughout the country. We called a meeting. I was there, Helms was there, Ellis was there, Phil Crane was there, who was very active in the Reagan organization. I had known Phil Crane before, so we were on speaking terms. Among others, I talked to the group, but the main purpose was to . . . . Helms talked to the group and Crane, but the main purpose was that I could tell this group . . . because these people were on the platform committee. That was the common denominator, with a few state chairmen.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large is a Platform Committee? Did you have representatives from every state?

John P. East:

Yes, two people from every state. Of course, we had those that we felt they had done the inviting, those on the Platform Committee were Reagan people but would be with us on these things, from all over the country. I would say there were probably fifty or sixty people there. So, what we did, I talked about the issues that we thought we ought to see that would be in the platform and the response there was good and we passed out these packets on the issues. What we were agreeing was that the next day when the Platform Committee met, we would, of course, be assigned to various sub-committees, but we could take these platform planks and go to our respected sub-committees, be it on Civil Rights or be it on foreign policy, and have some ammunition. You see what happened is, the Ford people controlled the make-up of the convention, because Ford was President and the Chairman of the Republican National Committee--Mary Louise Smith-- they were in charge of organizing the convention and that meant appointing committee chairmen . . . Robert Ray, a rather moderate liberal Republican Governor of Iowa, was in charge of the Platform Committee and so it went. They, of course, had had their own staff drafting a platform, so what I was doing, the role I was really fulfilling was, was to anticipate where their platform might be weak in terms of Ford's position on issues since he'd be in and to have prepared planks to plug those gaps. So, when we went into a sub-committee, we could say, as regards to Ford and Kissinger's Rhodesia policy, we would propose as an alternative this plank. I had never been through this before and I don't mean to be self-congratulatory, but in retrospect, I was rather proud of myself in that I anticipated the weaknesses that would be in that platform. I had never been on the Platform Committee, but my instincts turned out to be fairly good. On the things that most conservative Republicans would be unhappy with Gerry Ford on, whether it was

Helsinki or the snub of Solzhenitsyn or whether it was the beginning Rhodesian policy, attitudes on Taiwan and a whole host of things that more conservative Republicans were unhappy with the Ford administration on. Kissinger was not popular with conservative Republicans. They looked upon him as being soft and weak in many areas of foreign policy. Those are old battles, but that's what we did. We prepared these platform planks.

The next day then, we went to a whole Platform Committee meeting and the press was there. Robert Ray was the Chairman—very nice, pleasant. I sat very close to Ray, because being in the chair, they put me on the first tier, so it gave me a little bit of an advantage in being able to make points if I wanted to make them. They passed out the committee assignments. I noticed that I had been assigned, which I don't know if it was intentional or not, but to a rather, what I consider a rather modest sub-committee. What I wanted to do was to get on Foreign Policy and Defense. I did raise the question that day at the meeting, before the whole group, whether changes could not be made. Rather than say no, he said, well yes, he thought that could be done. He didn't want to encourage a lot of change, but if there were individuals that felt very strongly . . . .

Betty Lou Johnson questioned Ray on something about the rules. I have forgotten the technical point, but it obviously had the flare that Reagan people were challenging the Ford people in terms of how this thing was going. The press was interested in that, because they could get the first shaking. You see, the Platform Committee met a week before the convention, so we were the first thing to start. We were the beginning salvos. Betty Lou Johnson and I both made some comments at the first meeting. We might have been really the only ones who made anything that smacked of being challenging and a little antagonistic.

That night they had a reception. I remember Catherine Mackin, who was with NBC and is now with ABC. She caught me at that meeting and asked if she could talk with me and she had gotten on this thing about the planks and the platform and then she'd heard my comment that day. She wanted to know if we planned to make a very strong struggle on the Platform Committee, the Reagan forces did. I said, “Well, I don't know about the Reagan staff generally, but we from North Carolina intend to do everything we can to see that this is a strong platform, kind of representing the points of view that we think it ought to represent.” So they began to smell a little struggle there, generally. As the thing began to unfold, the media jumped into this as much as anything, not that it was necessarily such a big thing. It was the only show in town. They were out there. They were to cover the convention. They knew there was to be a Ford-Reagan clash. This was the initial clash. So, the media gave it a lot of attention. Leslie Stahl was there from CBS, who is a well-known commentator, and she talked with me at great length on various things. Catherine Mackin was there. Herbert Kaplow was there. Tom Brokaw was there. Ford Rowan was there. They followed this quite closely.

I finally managed to get assigned to the sub-committee on Foreign Policy and Defense. The Chairman of that committee was Senator Roman Hruska from Nebraska, who was not running for re-election, so was a lame duck Senator. The other prominent members of the committee aside from Hruska were Congressman David Treen from Louisiana, who is now running for Governor of Louisiana and apparently has a pretty good chance at winning. Nelson Fenwick, who is a woman Republican Congressman from New Jersey, well known, bright, articulate woman, she was on there. And, perhaps most importantly, Senator Hugh Scott from Pennsylvania was there. These people were

all members of Congress, two Congressmen and two Senators. We had a total, on the committee, of thirteen, because then we could have tie votes and the Chairman could break it. The interesting position we Reagan people found ourselves in or if you want to go even further than that, the position we found in is pushing these platform planks, going back to Ellis. First of all you started with the Ford document and it very much reflected the Kissinger foreign policy in every area. In fact, the man who drafted it was there in the room. We had the disadvantage, one, numerically, we were about even with them, but they had the heavy artillery. They had two Congressmen and two Senators. You see, Fenwick and Treen and Hugh Scott, and Hruska were all for Ford. So, they always had their eye out for anything that was unusual. Then they had one or two other Ford supporters on there and the rest of us were Reagan people. We started then with the disadvantage of one, they had written the platform. So, in order to change it, you see, you had to amend it. Otherwise, what they had went through. So, sometimes we had tie votes, which hurt, because a tie vote--if someone wasn't there for example--meant that they prevailed. So, we had that disadvantage, plus they had the political bigwigs on there. We did manage on balance to clearly strengthen what they had presented us. They might argue that we started off as weak as we could, as much reflecting the Ford-Kissinger position as we could and we knew there was some area to give and they did give. They had to. We had the votes against them. We did toughen it up, tighten it up. We had a big hoopla over the Panama Canal issue, basically over whether sovereignty and control should be given up. Those were trigger words. They didn't like them. So, we fought over the Panama Canal issue. We fought over the Taiwan policy, very strongly. We were very defensive of Taiwan; they wanted a more flexible policy in terms of the possible

opening to Communist China. We fought over the administration's Rhodesian policy, which we felt was moving in the direction of undercutting Ian Smith and playing more and more into the hands of the more militant black groups in there. I'm just trying to think of some of the other things we disagreed on. On the Helsinki agreement. On the Solzhenitsyn question. In fact, interestingly, on Solzhenitsyn, the Platform Committee met one day, all of us, and Rockefeller spoke and addressed us. I asked him at that meeting why they had snubbed Solzhenitsyn. That was a very emotional issue with many conservative Republicans. His answer was that they just didn't properly handle it and they didn't mean to. That was the answer he gave. Anyway, we raised the Solzhenitsyn issue. The Helsinki agreement, we felt, conceding too much and getting very precious little in return. In other words, challenging the whole Ford foreign policy as too soft, too vacillating, and not sufficient for the challenge we were facing from the Soviet Union and their proxies and minions in the rest of the world.

Defense policy, we hit that hard. We needed to maintain a position of superiority. It was essential in this day and age in terms of the realities of Soviet and Chinese power and so forth. So, we had a lot of debate, some of it pretty pointed. We remained on very friendly gentlemanly terms. I remember Hugh Scott saying one time on a motion I had made, I have forgotten what the motion was, but he said, “That is very critical of our administration. Inherent in your motion is a very critical position of our administration. I don't think we ought to be doing things that embarrass our own,” as he put it. I made the point, which at least seemed to work all right with me, I pointed out that I was a college professor and worked with young people and they prized candor and forthrightness even though it might create some momentary embarrassment to a given people, group or

faction. I said that it was within that spirit that I was offering my challenge, that if it did embarrass someone then I regretted that and I was sorry about it, but I thought politics was debased if you couldn't raise a legitimate substantive point simply on the charge that you're embarrassing one of our own. It was that kind of a debate; not name-calling, vicious, or brutal, by any means. Roman Hruska is a very colorful flamboyant guy. He could always smother us with love and he frequently did that; that we needed to move on and ought not to quibble too much over this and time was precious. . . . Now and then he could cajole us into a weakening position, simply because of urgency of time. When Senators tell you, we must move on . . . . And many of us were brand new at this business. You don't sit there and argue with Senators very long. You're slightly intimidated. I don't mean he meant it that way, but he was playing his role too, to keep it moving.

It's clear that Hruska and Hugh Scott intended . . . . Their responsibility was to see that the Ford administration did not come out of there horribly embarrassed. Concede whatever you need to concede that we can live with, but don't let us look bad. Probably, they performed that role. Ellis did catch me . . . . Interestingly, I was staying at the Downtown Hotel, where all the Platform Committee was. Ellis was out with the North Carolina Delegation on the other side of town. Ellis never called me; I never talked with Ellis.

It was very hectic. We only got three or four hours sleep at night and after the meetings were over, you'd go down and get your group together and decide what you're going to do the next day. We were constantly doing that. It was like a forced march really. I suppose, never a platform maybe put in so much time, because the stakes seemed

to be high in that it was again, the first volleys of the contest and you tried to make a good showing and show up the other side. If nothing else, it was to show you had the strength, which would tend to cause mavericks to want to come your way, because they would say, “Geez, the Reagan people are winning on the Platform Committee. They must have the votes. Let's go with strength.” So, there was an awful lot at stake, so we spent an awful lot of time on it. As I said, we got very little sleep. It was like a forced march, really, and some people just wearied and really literally wearied and kind of dropped to the wayside, because you can only keep that up so long.

Ellis never called me, but of course, the national media was giving me a lot of attention. He could see me on television and he knew what I was doing, because we got quite a bit of attention on that one particular sub-committee. Apparently, he was not unhappy, at least I never heard that. He came over one day and he was very intense about how things were going generally and he wondered whether on the Platform Committee, we were not conceding too much. He felt that rather than fight them to a draw, we were accommodating ourselves to changes. His point was, “Look, you think, John, that what we want is the best possible platform we can get. What I want is a document that embarrasses them and that we can take to the convention floor to show the whole convention what it is they are pushing through on this. So if you can't get what we want, just leave in their silliness.”

I was going, in the wheelchair, from the hotel over to the big civic center down there in Kansas City, where we met, the Radisson-Muehlebach Hotel. Ellis was pushing me and arguing with me all the way over. I thought it was kind of funny. Then when he pushed me up the hill and we were going down this hill, of course, then he could get in