PRESENTATION OF PORTRAIT OF HONORABLE ASA BIGGS TO UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTADDRESS BY F. S. SPRUILL OF ROCKY MOUNT. N. C., BAR ACCEPTANCE BY JUDGE H. G. CONNOR AT RALEIGH. N. C., JANUARY 18, 1915

PRESENTATION OF PORTRAIT OF HONORABLE ASA BIGGS TO UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTADDRESS BY F. S. SPRUILL OF ROCKY MOUNT. N. C., BAR ACCEPTANCE BY JUDGE H. G. CONNOR AT RALEIGH. N. C., JANUARY 18, 1915RALEIGHE. M. UZZELL & CO., PRINTERS AND BINDERS1915

ADDRESS OF F. S. SPRUILL

May it Please Your Honor, and You, Ladies and Gentlemen:

I have been commissioned by the partiality of the descendants and members of the family of Hon. Asa Biggs, one time Judge of this Honorable Court, to present to the Court, to be hung upon the walls of the courtroom, the portrait of that distinguished man, and to speak a few words concerning his high career and great achievements. I have undertaken the performance of this most pleasing task with cheerful alacrity because of the richness of my theme, but with much diffidence and distrust of my ability to meet the expectations of my overpartial friends.

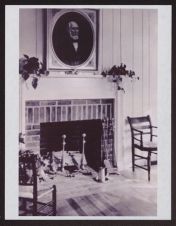

It is a custom, much to be commended, and one that seems to be growing in the State, to hang upon the walls of the buildings in which they performed their greatest deeds the portraits of the men who have made our history immortal. They serve to remind us, not of the fleeting shortness of life, but of the illimitable vastness of opportunity. They preserve in pictorial form the history and traditions of our proud old Commonwealth. They inspire us with the ambition, like their originals, to leave our footprints on the shores of time.

Occasionally, in the history of a State or people, a public man arises and passes out who is bigger in actual life than the panegyrist or biographer can make him after death. The reverse of the proposition is the general rule, but when it does so happen that the man himself is bigger than his shadow, it is either not observed at all, or, if observed, it is after the passing of many years, and when the searching eye of the historian begins to scrutinize the records in the search for truth.

There are few North Carolinians, even of her scholars, who know that the man whose portrait is about to be presented to this Court had, without solicitation on his part and with distinguished ability, before he was fifty years of age, filled nearly every office in the gift of the people of his State. There are fewer yet who know the high courage and the serene faith with which he met the many cares, responsibilities, and vicissitudes of the high offices to which he was called; and how always the

measure of his conduct was his conscience, enlightened by studious thought and by constant appeals for guidance to the fountain of all wisdom.

It is the purpose of this paper to acquaint posterity with some of the virtues, and to narrate some of the attainments, of this modest Christian gentleman.

A consideration of the traits, characteristics, ideals, standards of conduct, and even forms of expression, of the two men discovers a striking resemblance between Judge Asa Biggs and Hon. Nathaniel Macon. There was much of the Roman in them both. They had the same simplicity of manner, the same sturdy independence of thought, the same rugged honesty, the same tenacity of purpose, the same direct way of phrasing their thoughts, the same hatred of all shams and frauds, and the same stern civic righteousness. Each was a passionate lover of the State of his birth, and a believer in his heart of hearts that North Carolina skies were a little bluer, and North Carolina air a bit wholesomer, and North Carolina people a shade more patriotic, than were the skies and air and people of any other State in the Union. So when the time came that Judge Biggs regarded it as essential to his self-respect as a lawyer to leave North Carolina and begin the practice in another State, as will hereinafter be set forth, it cost him a mighty wrench to go. Hardly a year before his death, he wrote in his direct, simple way: “Nothing ever gave me more pain than my removal from North Carolina in 1869.” And then, as if unwilling to have the people, who had so signally honored and trusted him, uninformed as to why he had cast his lot in Virginia, he goes on to say: “My excuse is that the tyranny to me of ‘the powers that be’ was so humiliating, and the duty to my family to provide for them an honest livelihood was so pressing, that I could not patiently submit, and I sought a quiet and, as I hoped, a secure retreat from the turmoil.” He was referring to the conduct of the Supreme Court in attempting to disbar that distinguished roll of lawyers of the State (he being one of them) who had made their “solemn protest against judicial interference in political affairs.” Other practitioners might answer the rule served upon them and purge themselves of the alleged contempt by apologizing and paying cost, but to this old Roman, conscious

of the rectitude of his own purpose and knowing that he was well within his rights as a lawyer and as a man, it was impossible to

“Let the candied tongue lick absurd pomp.And crook the pregnant hinges of the kneeThat thrift may follow fawning.”And so he expatriated himself and kept his manhood intact. In his address to the people of North Carolina, elicited from him in December, 1873, at Norfolk, by a cruel and unfounded aspersion upon the conduct of his firm on the part of the then Chief Justice, in a few, short, manly, trenchant sentences, he tells his former fellow-citizens, and posterity, the reasons for his act in expatriating himself. Hear him: “I assumed the ground, and adhered to it, that the ‘Protest’ was right in itself; that it was a duty of the Bar to aid, if possible, in saving the Judiciary in the future from degradation and contempt; and that this was an attempt, on the part of the Court, to stifle and silence one of the great elements of public opinion, and to assume and practice judicial tyranny, that was intolerable. I positively declined to sign any paper which might be construed into an apology for an act which I believed was right and commendable, and which the Court had no power or right to treat as a ‘contempt,’ and in this manner disbar and silence in the courts the members of our noble and conservative profession.” Truly, this man was “not a pipe for fortune's finger to sound what stop she please.”

Asa Biggs was born February 4, 1811, in the little town of Williamston, on the banks of the Roanoke River, in Martin County. His father, Joseph Biggs, was a small merchant in the town, and, according to a not unusual custom of the religious denomination of which he was a member, of uniting the secular and the religious, was also a preacher of the Primitive Baptist Church. He was three times married, and Asa, the subject of this sketch, was the second child of the third marriage, there being five children of that marriage, towit, four boys and one girl. Joseph Biggs, while himself of limited learning, was a warm friend of education, and it was mainly due to his exertions and enthusiasm that the academy at Williamston was established about 1820. The son, Asa, bears testimony to the character of the father, in a document addressed to his children and written nearly one-half century later, in the following words:

“He gave to us all the elements of education to the utmost of his ability, and moral precepts and examples which have survived him, and can enable me to say with truth: ‘No better parent ever lived than your grandfather.’ ”

At this academy at Williamston, Asa received his educational advantages and attained great proficiency in the classical studies. He was a robust, vigorous boy of good mind and clean habits, and was fired with a laudable ambition to raise himself out of the ruck of the ordinary village boy. He grew rapidly and at the age of 15 was of man's stature, weighing 180 pounds. At this age the boy, who had planned for himself a commercial career, left school and began his preparation for the life and career he had at that time chosen. He entered the mercantile establishment of a Mr. Martin, a merchant in Washington, in the capacity of a clerk. The compensation is not known, but a year later, in 1826, he had evidently improved his condition, for he went to Hamilton as a clerk for a Mr. Edwards, a merchant of that place. In June, 1827, while only 17 years of age, he was engaged by Mr. Henry Williams, of Williamston, to superintend his mercantile business at that place, under a contract to receive as compensation one-third of the net profits of the business. This arrangement continued for two years. These incidents are set out in detail merely as prophecies of what the man's future contained. While yet a lad of 17, he had so impressed himself upon the people among whom he had grown up that he was intrusted with the supervision of a considerable business. He made the business succeed, and then his mental horizon widened and his vision extended. The lad was beginning to come into his own. He was fired with the ambition to be a lawyer—not a pettifogger, but a real lawyer, wise and learned, and, above all, greatly trusted. His sense of exact justice would not permit him to retain the position of superintendent of his employer's business while the main purpose of his life was something else, and he gave up this position and took a clerk's place at a much smaller compensation so that he might prosecute his studies. He had no legal instruction and his education was limited, but diligently, earnestly, and faithfully he read and studied and wrought until in July, 1831, when he was not yet 21 years old, he felt that he was equipped to stand the examination for license.

He successfully passed the examination and was granted license by Judges Henderson and Hall to practice in the County Courts.

Here, for the purpose of this paper, his career may be regarded as begun. At his first court, held a few days after he was licensed, he tells us in his autobiography that he made $50, and with refreshing candor he adds: “I regarded this a good beginning, and it gave me great encouragement.” His maiden speech was an address to the grand jury of Pitt County, in August, 1831, it being at that time the custom for the charge to the grand jury to be made by some member of the Bar, usually a young member. His early career as a lawyer does not differ greatly from that of the ordinary practitioner in the little country town, who has in him the elements of success. He says in his sketch of himself above referred to: “I commenced with a determination to succeed, if possible; attended the courts regularly, applied myself unremittingly to my studies, and gave diligent attention to any business confided to my care.”

His practice grew as his reputation for assiduous attention to his business increased. He attended regularly the courts of Martin, Pitt, Bertie, and frequently Edgecombe, Greene, and Washington. His probity was of the sternest character, and early in life he was known to have inveterate hatred for all forms of sham and deceit. Of him it can be truly written: “In his heart there was no guile and his lips could not frame a lie.” He was of simple tastes, economical in his expenditures, and temperate in his habits, and so, although the emoluments from his profession were never very great (he states they never exceeded $4,000 per year), they were ample for him to generously provide for the wants of his family and to lay by each year a little store for the storm and stress that were coming.

On June 26, 1832, he was married in Bertie County to Miss Martha Elizabeth Andrews, a daughter of Henry Andrews and his wife, Elizabeth. By her there were born to him ten children, of whom two died in infancy, the other eight reaching practical maturity. Two sons, William, the father of Hon. J. Crawford Biggs (himself a lawyer of great attainments and honor, one time Judge of our Superior Court and now the honored President of the State Bar Association, who tonight sits with us), and Henry, entered the Confederate Army while yet mere lads of

17 and 18. William became Captain of Company A, 17th Regiment, North Carolina Troops, having left the Junior Class at the University of North Carolina to join a company that left Williamston for the front on May 20, 1861, the very day the State seceded. Henry was killed at Appomattox on April 8, 1865, the day before Lee surrendered. Strange irony of fate that he should have come through the war from the time of his enlistment to the day before it ended and be reserved for the final sacrifice.

The fall of the Confederacy, in the ultimate success of which Judge Biggs had unfalteringly believed, together with the death of his son, for a period almost crushed the brave spirit of the man, and but for his fortitude and his serene and steadfast faith in God and His infinite goodness, this would have been a most critical period in his life. Even as it was, the man's heart was very sore, and, in an addendum to the sketch above referred to, bearing date July 8, 1865, he voices his great sorrow and declares his unshakable faith in the Infinite Goodness. Time and space alone prevent a transcript from that record, which, while the moan of an anguished heart, stricken to its profoundest depths, is still the utterance of a brave man, bowing in dignified submission to the Omnipotent Hand that scourged him.

Mr. Biggs was of an intensely religious nature. There is perhaps no more interesting or dramatic part of the engrossing narrative that he wrote for his children than that which deals with his conversion and his religious experiences thereafter ensuing. In words that stir and arouse, he details the tremendous upheaval of his soul when at length he became fully conscious of man's fallen condition and utter inability, without Divine aid, to be saved. This seems the more remarkable for that he was a man of excellent morals, temperate in all his habits, charitable, of unsullied integrity, and conforming in his daily walk and conversation to the best traditions of Christian manhood, and yet so profound was his conviction of sin, so intense the strivings of his sin-sick soul, that one is almost moved to tears as he reads this strong man's story of his struggles to attain the light. He was 40 years old when this crisis in his life came, and it was so realistic to him, so genuine, that it affected him physically to the

extent of actual disorder. He described the anguish and stress through which he passed during the several days he was seeking reconciliation, as “compared to an impenetrable overhanging cloud, ready to burst upon me in all its fury, and to sink me to everlasting despair and ruin; while I was anxiously looking for some ray of light, through the gloom, by which I might hope to escape the impending danger; but no glimmer could I discover. I felt, indeed, that I was a poor, miserable, and lost sinner; condemned to punishment for my iniquities; and my cry was, ‘Lord! save or I perish.’ All my moral rectitude did not avail me. I could see nothing to extricate me from this awful dilemma. My intense suffering forced me to cry out in despair, and I really concluded that I was going deranged, and frequently asked, ‘Am I losing my mind?’ During this deep distress all my sins and improprieties seemed to be brought before me, and I am reminded that I felt sincerely desirous to make friends with all those with whom I was not then on friendly terms, and felt willing to accommodate every difficulty I had ever had with my fellow-men. I was willing to obtain relief in any way, and from anybody, and readily attended the meetings with the hope of being relieved; yet my inclination was to seclude myself from observation and read and pray, and meditate in secret; and thus I was engaged the most of the time for several days. Nothing that was said or done appeared to soothe or console; I was unutterably miserable, and could find no solace or hope.” A strange experience truly for this conservative, thoughtful, quiet man!

The narrative then proceeds with his description of the return of his composure and serenity. There was no sudden deliverance from his deep distress, but a gradual transition lasting through several days, from storm, mental disturbance, and profound melancholy, to calm composure, peaceful serenity, and exuberant thanksgiving. Soon thereafter he was baptized, joined the Primitive Baptist Church, and, after a life of deep piety, he died in full fellowship in that religious denomination. I have set out this phase of the man's life somewhat at length because of the leading part he gives it in his autobiography, and further because, after its occurrence, it affected most profoundly his whole life and conduct.

The independence of thought of Mr. Biggs first manifested itself in the fixing of his political affiliations. His father, and indeed all of his forbears, were Whigs, and it would have seemed most natural for him to have entertained their views almost by heredity. Yet, when he reached manhood's estate and was called upon to choose his political creed, he carefully studied the platforms and cardinal principles of the two leading parties. The attitude of the Democratic Party, upon the great question of the Tariff as a National issue and of manhood suffrage as a State issue, appealed to him as eternally just and right; and so, in the face of family and friends, he openly proclaimed himself a Democrat. This is the more remarkable and is high proof of his sincerity for the reason that the Democratic Party was then the minority party in the State and district. This did not seem to weigh with him or influence him. His political career is picturesque and unique in that he never sought but one office, and yet he held at various times almost every office in the people's gift.

In 1835, when he was only 24 years old, he was elected by the voters of Martin County a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, being the youngest member of that dignified body. It was composed of the most learned, experienced, and talented men in the State, and young Biggs, feeling his youth and inexperience, and following the inclination of his fast ripening judgment, during that session participated in no debate, but listened attentively and carefully to the debates engaged in by the best equipped orators and debaters in the State. This experience was of untold service to him in his after life.

The colleague of Mr. Biggs in that convention was Jesse Cooper, who for many years had represented the county in the General Assembly. Many grave and important measures were proposed and discussed. The one which elicited most prolonged consideration was the proposition to amend the Constitution in respect of the right of Roman Catholics to hold office.

In 1840, again without solicitation, he was nominated and elected a member of the House of Commons and was reëlected in 1842. By this time the man had “found himself,” and, having decided convictions upon all public questions and the faculty of speaking what was in his mind in a plain, simple, and

straightforward manner, he became at once a leader of his party. He was an avowed friend of internal improvements, but the bitter, the inveterate enemy of extravagance and jobbery, no matter from whence it proceeded. In the canvass preceding the election of 1842, Mr. Biggs again showed his manly independence and his moral courage in opposition to what he believed to be a vicious custom. For many years it had been the custom of candidates seeking the suffrages of the voters to indiscriminately “treat” every one who chose to participate. The word “treat” is a colloquialism, and means to offer spirituous liquors to and to drink at your own expense with any and all persons invited. It is the term Mr. Biggs himself employed in his sketch above referred to. The custom was almost ancient and universal enough in the east to amount to common law. It was of course pernicious and debasing, but not even members of the Gospel theretofore nominated to office had been courageous enough to denounce it. In this campaign young Biggs boldly denounced the custom as injurious to the public morals, and as tending toward the destruction of civic righteousness. He unqualifiedly refused to follow the custom, and, although his friends warned him that it would defeat him, and his enemies circulated all manner of false reports concerning him, he avowed his purpose to go down to defeat with honor rather than to win victory by means which his judgment disapproved and his conscience condemned. Be it said to the credit of the people of his county, he was triumphantly elected.

In 1844 he was nominated to the State Senate and was opposed by his old friend and colleague, Mr. Jesse Cooper, and also by a prominent Whig nominee. Mr. Cooper's candidacy was independent and his platform was opposition to nominating conventions that had just come into vogue in the east. This split in the Democratie ranks, especially with Jesse Cooper leading the bolters, was a serious matter for young Biggs. He had not sought the nomination, but, having put his hand to the plow, he could not afford to look back. Without appealing in any wise to the passions of the voters, fairly and temperately, Mr. Biggs presented his views and argued his principles. Again he was triumphantly elected, obtaining a handsome majority over both opponents. Thus he was transferred to a new theater of action

as a State Senator, a body equally divided in voting strength and composed of able, experienced men and adroit politicians. Without pyrotechnics, and fearlessly, he discharged his duty with fidelity to the party of which he was a member, but always with an eye single to the best interests of the State.

And now follows the incident in the career of Mr. Biggs which proves how the plans of politicians may be utterly confounded by an underestimate of the knowledge of the voters. In 1842 the county of Martin had been attached to the Ninth Congressional District. Theretofore it had had no political relations at all with any county in the district except Bertie. The district was overwhelmingly Whig in its politics, having in the previous election given a large majority for the Whig candidate. Late in the Spring of 1845 the Democratic District Convention was held in the extreme eastern end of the district. Martin County was not represented, and Mr. Biggs, forgetful even of the date of the convention, was busy in the discharge of his professional duties. The convention, without his knowledge, nominated him as the candidate for Congress for that district and adjourned sine die, the delegates going home. Mr. Biggs’ first knowledge of the action of the convention came from the committee appointed to notify him. Against him, the Whigs had nominated Col. David Outlaw, a distinguished lawyer and a gentleman of great talent and worth, from Bertie County. In most of the counties Mr. Biggs was personally unacquainted, while Colonel Outlaw, who had theretofore represented the district in Congress, was widely and most favorably known. To accept the nomination apparently meant defeat; not to accept it meant an open exhibition of fear of that defeat. Mr. Biggs kept the matter under consideration for a week, and finally, feeling it was his duty to go where his party ordered, accepted the nomination and entered the campaign. The party issues were discussed in joint debate by the two candidates. Except for one notable instance, there has been perhaps no campaign in the State conducted with greater dignity and circumspection than was this one. While the distinguished debaters did not spare each other's political positions or arguments, yet they maintained their social intercourse and friendship unimpaired, and the personal respect and esteem of the two men for each other was increased rather than diminished.

It is not necessary to advert to the divergent views of the two men. Each stood for the best in his respective party. The burning questions of that day and time have for the most part, in regular recurring cycles, become the burning questions of other times and eras. The tariff, the currency, the distribution of public lands, the Nation's attitude to the merchant marine, engrossed the attention of the public, and furnished abundant matter for wide divergence of opinion. Mr. Biggs was an orthodox partisan of the Democratic school, and Colonel Outlaw equally orthodox of the Whig faith. Both were well equipped, of clean personal life, and both broad enough to give and take like gladiators in the battle in which they were engaged. The election was very close, and Mr. Biggs was chosen by the narrow majority of 146 votes in a district of 10,000 voters. The one incident of the campaign that marked Mr. Biggs as being a statesman and not a politician was his refusal to temporize where principle was involved. In some of the counties of the district the electors were strongly committed to certain measures not in line with the party's principles. In these counties the friends of Mr. Biggs earnestly urged him to follow the injunction of St. Paul and “be all things to all men,” but this man refused “to trim his sails to every favoring breeze,” and boldly and almost definatly proclaimed his party's creed and declared his unalterable purpose, if elected, to support that creed by speech and vote in the halls of Congress. This course may have lost him some votes in some of the counties; certainly it increased the respect for and confidence in the man who thus proved that he held principle higher than temporal advantage.

During his first term in the lower branch of the United States Congress Mr. Biggs, though only 34 years of age, so impressed himself on his colleagues, among whom were David S. Reid, afterwards Governor of the State, and Mr. Dobbin, afterwards Secretary of the Navy, that he was at once regarded as a leader. It is not perhaps generally known that he precipitated the controversy resulting in the unexpected resignation of Mr. Haywood from the United States Senate. Mr. Biggs, while a member of the Legislature, had assisted in securing the election of Mr. Haywood. The House of Representatives passed a bill to modify the tariff, for which Mr. Biggs and the entire Democratic Party had

voted. The vote was so close in the Senate that the issue was in grave doubt. As the time for taking the vote in the Senate approached, it was rumored that Mr. Haywood was opposed to and would vote against the measure. Mr. Biggs proposed to the Democratic members of the House from North Carolina that they should call upon Mr. Haywood and remonstrate with him. They declined to do it, for the reason that none of them had been in any wise responsible for his election. Mr. Biggs then sought an interview with Mr. Haywood, and an animated and exciting colloquy occurred between the two men at the door of the Senate Chamber. Shortly afterwards, during the same day, Mr. Haywood, apparently impressed with the view urged by Mr. Biggs that he had no right, while occupying a seat as a Democrat, to antagonize Democratic measures, resigned his seat in the Senate, which placed the fate of the bill in still graver doubt. Fully impressed with the sense of his public duty and feeling sensibly the tenseness of the situation, Mr. Biggs, on the next day, in the House publicly denounced Mr. Haywood's conduct. It is not improper to add that Mr. Haywood was generally condemned by his party in the State for his course and never recovered his political prestige or standing.

At the commencement of the short session in 1846 Mr. Biggs wrote to the leading men throughout his district, declining to run again and requesting that steps be taken in time to secure some other suitable candidate. There was universal dissent, and no course was left open to him but to either make the race a second time or incur the disapproval of his warmest and most valued personal friends. Again, therefore, in 1847, Colonel Outlaw was his opponent, and a joint canvass was again had between them. The Mexican War and its incidents were the only issues discussed. For the first and only time in his whole career Mr. Biggs tasted the bitterness of political defeat. Colonel Outlaw was elected by a majority of seven hundred and Mr. Biggs, to whom the defeat was not unexpected, felt that the time had come when he could honorably retire from public life and devote himself to his profession and to rearing and educating his large and growing family. He had of necessity lost his clientele and, being scrupulously honest, had come out of public office poorer than when he entered.

In 1848 he had a joint canvass as Presidential Elector with Edward Stanley.

It was during this period of his life, while he was engaged in the arduous task of rebuilding his lost practice, that he underwent the religious experience which is above set out.

In 1851, again without solicitation, he was appointed by Governor Reid, his old colleague in Congress, on a commission with Judge Saunders and Hon. B. F. Moore to revise and codify the statutes of North Carolina. This was a work eminently suited to his tastes and habits, and he undertook it with real pleasure. Almost at once Judge Saunders resigned and the whole responsibility of the work rested upon Mr. Moore and Mr. Biggs. The commission was to report to the General Assembly of 1852, but it was soon found impracticable to complete the gigantic task within that time. The General Assembly of that year continued Mr. Moore and Mr. Biggs as the committee and authorized them to proceed, without electing a successor to Judge Saunders. Their report was made to the General Assembly of 1854. The work is known as the Revised Code, and it stands as a lasting monument to the legal ability, the profound research, and the unlimited pains and care of its authors. It remained in force for nearly twenty years and until Battle's Revisal substituted it. It is perhaps the most scientifically arranged and prepared of the several codifications of the State's statutes.

In 1854 Mr. Biggs was nominated and elected to the General Assembly from the district composed of Martin and Washington counties. He was induced to accept this nomination solely because of his anxiety concerning the fate of the Code on which he and Mr. Moore had been engaged. The professional reputation of himself and his colleague was involved in obtaining the consent of the Legislature to pass the Code just as they had prepared it. Knowing how liable it was to be marred and disjointed in its sequence and continuity by amendment, he was constrained to accept the nomination that in order, if elected, he might act as guardian of this Magnum Opus of his and of his colleague's brain. In this the closest and most fiercely contested of his campaigns he was elected by only twenty-one votes majority in the district, Washington County being strongly Whig. He was successful in protecting his literary offspring from violence,

if not from assault, and it was adopted practically as it left the hands of its authors. Mr. Biggs was the recognized Democratic leader in that Legislature, and Governor Graham was the Whig leader.

The General Assembly of 1852 was the regular period for the election of one United States Senator, and the session of 1854 for the election of the other. In consequence of the nearly equal division of parties in 1852, a contest arose between Mr. Dobbin, who was the regularly nominated candidate of the Democratic Party, and Judge Saunders, who opposed him, and the session terminated without an election. The election of two Senators was therefore thrown upon the Legislature of 1854, and of course excited much feeling and interest. Many names of high prominence were canvassed in the newspapers, and among a large number Mr. Biggs’ was mentioned. He did not reach Raleigh until the night before the session was to open, and then ascertained that active canvassing had been going on for a week by aspirants for these distinguished positions, and that his name was being generally discussed. It was evidently the desire of the members to decide these elections as early as practicable, and to that end a caucus of the Democratic Party was held on Tuesday night. He did not attend, although urged by some of his friends to do so, nor would he visit the members, as customary with others, feeling that it was a position not to be attained by personal solicitation. The session of the caucus was protracted, with the result that Mr. Biggs was nominated on the second ballot for the six years term and Governor Reid (then Governor) was nominated for the short term of four years. The other names voted for were Chief Justice Ruffin, General Clingman, and Burton Craig. On Thursday the election was held by the General Assembly and Mr. Biggs and Governor Reid were elected according to the nominations, which placed Mr. Biggs as the successor of Mr. Badger. Thus unsolicited on his part, at the age of 43, he was elevated to one of the most distinguished places in the gift of the State.

His career as United States Senator was in keeping with all his former life. Conservative, without being overcautions; loyal, without being overpartisan; faithful in the discharge of his duties and heedfully attentive to the demands upon him by

his constituents, he made an acceptable and efficient Senator, meeting its high requirements, as was his wont, with simple dignity and manly bearing.

At the second session, by reason of his record made at the first session, he was put on the Finance Committee, then, as now, the most important committee in the Senate. He was also a member of the Committee on Territories, which, on account of the Slavery question, was also one of the most important committees of the Senate. The records show that he took an important, even a leading, part in the debates which were then daily growing in acrimony as the great impending struggle grew nearer and nearer. His speeches, while honest and with uncompromising clearness expressing his decided convictions as to States’ rights, are well worth perusal as models of self-restraint, and of conservative, statesmanlike expressions upon the burning questions under consideration.

In the winter of 1857-8 Judge Henry Potter, Judge of the United States District Court for North Carolina, who had been appointed by President Jefferson in May, 1801, died, and his successor was to be appointed. Judge Potter bears the unique distinction of having held judicial office for the longest consecutive period in the history of the United States. Incidentally he verified the aphorism that “few die and none resign.” President Buchanan, in May, 1858, appointed Senator Biggs as successor to Judge Potter, and the appointment was unanimously confirmed by the Senate. In this connection it should again be noted that for this office Senator Biggs made no application. It was a rule of his life, rigidly adhered to, to solicit no office, and each and every honor and office, of the various positions held by him, came to him not only without solicitation on his part, but, in the majority of cases, without even former notice to him.

Upon his appointment and confirmation as District Judge, he at once resigned his seat in the Senate, and began diligently to qualify himself for the responsible duties of the Judgeship. The District Courts were held twice a year at Edenton, New Bern, and Wilmington, and the Circuit Court once a year at Raleigh. In the latter court the presiding Judge was one of the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Judge Wayne was assigned to this circuit. Judge Potter's age and

ill-health had for many years made the United States Courts formal farces. Judge Biggs began at once the reorganization of the courts by the preparation and adoption of the necessary rules of practice and the appointment of the officers and clerks therefor. Until 1861 he held the District Courts regularly, and the business began to grow and accumulate. He also held unaided the Circuit Courts at Raleigh until that date. In November, 1860, at which time the political atmosphere was surcharged with excitement and the question of States’ rights had grown to the point that it overshadowed every other one, Judge Biggs, who was an ardent States’ rights man, had some correspondence with Judge Wayne in respect to the approaching Circuit Court at Raleigh. From that correspondence he gathered that Judge Wayne denied the right of a State to secede from the Union. Inasmuch as Mr. Lincoln had then been elected President of the United States, and the excitement in the South had greatly increased, Judge Biggs thought it was not improbable that the question might become a practical one and present itself to the Court for adjudication. He apprehended that Justice Wayne, in his charge to the grand jury, might give publicity to his views on the question of States’ rights, and, inasmuch as he differed from Judge Wayne on the question “as far as the East is from the West,” he was at great pains to prepare and set down in writing a charge to the grand jury which he intended giving in case Judge Wayne were not present, or if, being present, he should leave to him, Biggs, the duty of charging the grand jury. He also prepared another charge, in the nature of a dissenting opinion, to be delivered in case Judge Wayne, in charging the grand jury himself, should declare against States’ rights. The performance of this disagreeable duty, as it was conceived by Judge Biggs, was rendered unnecessary by the excellent taste of Mr. Justice Wayne, who did not in the remotest way allude to the question which was then rending the States asunder.

The matter has long since been settled by the arbitrament of war—the bloodiest, save the one now in progress, in the world's history. Time and space forbid my incorporating into this sketch those brave words of a brave man. Let it suffice to say that in clear, trenchant sentences, Judge Biggs set out the doctrine of States’ rights even to its logical conclusion of the right

to secede from the Union. Even at this distance of sixty-five years it seems not easy to answer his argument, and it is well that the question, no longer open to debate, is now simply a matter for speculation and polemics.

The tension increased daily and the first low mutterings of the coming storm were heard. The election of Mr. Lincoln as a sectional candidate, with his avowed principles in favor of abolition, and against the rights of the States, was to the South, already jealous to the point of hostility, almost equivalent to a declaration of war. The Gulf States had one by one seceded, and subsequently Virginia, and then North Carolina ranged themselves with their Southern sisters.

The Legislature of North Carolina, in February, 1861, first submitted the question of a State Convention to the votes of the people, with a provision that if a majority of the voters should decide in favor of a convention, it was to assemble at once. To that end delegates to such convention were elected at the same time that the vote was taken on the convention itself.

North Carolina by a small majority voted against the convention, and the State, therefore, for the time being remained in the Union. Judge Biggs, with his advanced views on States’ rights, was avowedly and openly in favor of the convention, yet he retained his office as Judge, deeming it imprudent to resign until the State should secede, or until such controlling circumstances should occur as would bring him to the conclusion that he could not longer hold the Judgeship consistently with honor or his duty to the State.

Stirring events succeeded each other with amazing rapidity. The failure of the Peace Congress to compose the disagreements was followed by the President's Proclamation of April, 1861. Immediately Judge Biggs realized that the time had come for him to act. From his home he wrote and sent to President Lincoln the following communication, which is probably unique in the annals of resignation literature:

WILLIAMSTON, N. C., April 23, 1861.

TO ABRAHAM LINCOLN,

President of United States.

SIR:—I hereby resign my office of District Judge of the United States for the District of North Carolina, being unwilling to

longer hold a commission in a Government which has degenerated into a military despotism. I subscribe myself yet a friend of constitutional liberty.

ASA BIGGS.

No phrases of “distinguished consideration,” no avowals of “obedient subserviency,” no expression of “profound respect”—plain and direct as the nature of the man who wrote it is the letter which retired to private life the man of many experiences and of varied official fortune.

Another convention was called to convene on May 20, 1861, and an election for delegates was ordered for the 13th. Almost without opposition, Judge Biggs was elected the delegate from Martin County and was one of the leaders in the convention. On May 20th, the day the convention assembled, an ordinance of secession was unanimously adopted.

On June 17, 1861, Judge Biggs was appointed by Jefferson Davis Judge of the District Court of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States for the District of North Carolina, and this appointment was confirmed by the Confederate Congress and a commission was issued and sent him on August 13, 1861. Upon the formation of the permanent Government of the Confederate States, he was again appointed Judge of the District Court by President Davis, and a commission issued and sent him on April 15, 1862. In the Winter of 1861-2 he had resigned his seat in the convention, and so he took the oath of office as District Judge of the Confederate States before Judge Heath of the State Supreme Bench on May 27, 1862. This position he held until the surrender of Lee at Appomattox and the formal fall of the Confederacy.

From this time forward, for several years, we have no record of Judge Biggs’ achievements. He began again as a practitioner at the Bar in Tarboro, N. C., and, in the troublous times succeeding upon the surrender, and the beginning of our reconstruction period, he bore his part bravely and without complaint.

In the Spring of 1869 a number of the lawyers of North Carolina, among whom were the oldest, ablest, and most conservative members of the Bar, to avert what they regarded as an improper interference in political affairs by the Judges of the Supreme Court, prepared, signed, and published a “protest.” It was able, dignified, positive without being brusque, and direct without

being offensive. Judge Biggs was one of the signers of this document, and heartily sympathized with its objects and purpose.

At the June Term of the Supreme Court following, a rule was served upon the signers to show cause why they should not be attached for contempt, or, to speak with greater accuracy, the signers of the “protest” were officially advised that they had put themselves in contempt, and that no man who had signed the “protest” could practice again in the Court until he first apologized for his conduct and paid the cost of the proceeding. Some of the lawyers who signed that history-making document are yet living. The argument in support of the answer of the respondents to the rule was worthy of the three great lawyers who made it, but the Court adhered to its purpose, and no course was left open to the respondents but to comply with the Court's requirements or to retire from the practice in the State.

Judge Biggs, who did nothing from impulse and who had weighed his act when he penned his name to that document, was not able to accommodate his conscience to the Court's requirements. Therefore, although he was nearly sixty years old and had lived his entire life among the people of North Carolina and loved his native State with a passionate intensity, he chose the hard alternative of expatriating himself rather than partake of this humiliating dish which was set before him. He moved to Norfolk, Virginia, and, with the energy of a boy and the courage for which he was distinguished, he began anew the practice of the law in that city. He formed a connection with his brother, Kader Biggs, in the commission business at Norfolk, under the firm name of Kader Biggs & Co., and about the same time he associated in the practice of law with Hon. W. N. H. Smith, afterwards Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of this State. He continued in the practice there, and likewise in the commission business, until his death, which occurred in the city of Norfolk on Wednesday, March 6, 1878. During his residence of nine years in Norfolk his heart was always turning back to his native State, to the theater of his toils and triumphs, to the home of his youthful hopes and his manhood's ambitions.

In Judge Biggs were blended the simplicity of childhood and the wisdom of age. To a tireless industry was added fine discrimination and excellent learning; but the highest quality in

his well rounded character was that without which all else would have been of no avail—he was possessed of an integrity unassailable, and his honesty was without variableness or shadow of turning. Men loved him for his guileless simplicity, they respected him for his great gifts of mind and heart, but they revered and trusted him for his sturdy honesty and his inflexible integrity.

It is meet and proper, before closing this sketch, that we note especially the rank and attainments of Judge Biggs as a lawyer. If genius be the capacity for infinite pains, then Judge Biggs had a high order of genius. He was tireless in his assiduity, relentless in his efforts to find the truth, and bold in his purpose to declare it. His professional career was as honorable as it was successful, and furnishes to us who come after him a worthy example for emulation. Patient, thorough, careful, faithful in the discharge of his professional obligations, it was but natural that his business should have increased until he was the leading lawyer in the tier of counties in which he practiced. Perhaps the most noteworthy thing in his arduous professional career was that, while he threw into his contests all the force and skill and ardor of which he was capable, he rarely if ever gave offense to his adversary. He retained to the end the affectionate regard and the unqualified respect of his brethren.

And now may it please your Honor, my pleasant task is done. In the name of the descendants of Hon. Asa Biggs, who, like himself, have met the issues of life bravely and performed its duties with high success, I am commissioned to present to this Court this excellent portrait of one of the greatest of your predecessors. It is their earnest wish that it may not only aid posterity to learn aright the history of the stirring times in which he lived and wrought, but also that it may inspire in the hearts of those who shall look upon the strong and composed features of the man there limned, a more abiding affection for the grand old State of his birth, that, even unto the end, he loved above all things else.

ACCEPTANCE BY JUDGE CONNOR.The duty which devolves upon me of accepting the portrait of Judge Asa Biggs, the first presented to this Court, is a valued privilege no less for personal than official reasons. Judge Biggs was in point of eminent service and public position the most distinguished citizen of the State called to preside over this Court. That he preferred the less distinguished place and, usually, less attractive work, of the Bench to that of the United States Senate is convincing evidence of his devotion to his profession and the administration of justice. He brought to the discharge of its duties, not only a long and large experience at the Bar, and service to the State and Nation, so admirably and eloquently told in the inspiring story of his life by Mr. Spruill, but those high mental and moral qualities—loftiness of ideals, steadiness of purpose, courage of conviction, integrity of mind and heart, love of justice, truth and equity, which are the essential attributes of the judicial office. We may well believe that when the occasion came for him to make the election, he was guided by the noble sentiment of another of North Carolina's great magistrates, when called upon to make a like decision—one with whom he had served in the Convention of 1835, and whom we are assured he admired and trusted, although of different political faith, that the faithful performance of the duties of the judicial office are as important to the public welfare as any which it is in the power of the citizen to render; that to give a wholesome exposition of the laws, to administer justice with a steady hand and an upright purpose, are among the highest of civil functions, and that there was no better way in which he could serve his country. Controlled by this lofty ideal, guided by the learning which came from patient and persevering study, sustained by that source of wisdom which no less by his walk and conversation than by experience he gave evidence of having sought and found, he gave judgment without respect of persons—heard the small as well as the great, and in righteousness rendered to all who brought their causes before him, justice and equity; and this is the office of the

Judge. To those who are honored in bearing his name, and in inheriting his virtues, who have in this appropriate manner preserved and perpetuated his memory, we express, for the Court, the Bar, and the people, our sincere thanks. The portrait of Judge Biggs will be so placed in our courtroom that we may draw inspiration from his life and be strengthened in the discharge of our duties by his example.