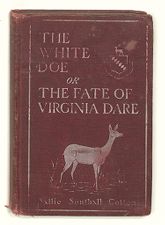

THE WHITE DOEORTHE FATE OF VIRGINIA DARE

Illustration of white doe near riverbank

Sallie Southall Cotten

Presented to, Bruce Institute By Sallie Southall Cotten, February 1908. Mrs John Denton

Compliments of Garrett & Co. Pioneer American Wine Growers Established 1835 Vineyards at Tokay, Medoc and Chockoyotte, N. C. Home Office, Norfolk, Va. Western Branch, St. Louis, Mo.

THE WHITE DOE

THE WHITE DOETHE FATE OFVIRGINIA DARE AN INDIAN LEGENDBYSALLIESOUTHALLCOTTEN

decoration acorn oak leaves branchPrinted for the AuthorBY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANYPHILADELPHIA

Copyright, 1901 BY SALLIE SOUTHALL COTTEN All rights reserved

TO The National Society of Colonial Dames of America WHOSE PATRIOTIC WORK HAS STIMULATED RESEARCH INTO AN IMPORTANT AND INTERESTING PERIOD OF THE HISTORY OF OUR BELOVED COUNTRY

FORGOTTEN FACTS AND FANCIES

OF AMERICAN HISTORY

AS civilization advances there develops in the heart of man a higher appreciation of the past, and the deeds of preceding generations come to be viewed with a calm criticism which denudes those deeds of false splendor and increases the lustre of real accomplishment. Man cannot see into the future and acquire the prescience of coming events which would make him infallible, but he can remove the veil from the past, contemplate the mistakes and successes of those who have lived before him, and who struggled with the same problems which now confront him. The results of their efforts are recorded in history, and inspired by high ideals he can study the past, and by feeding his lamp of wisdom with the oil of their experiences he secures a greater light to guide his own activities. Man remains a slave to Fate until Knowledge makes him free, and while all true knowledge comes

from experience, it need not necessarily be personal experience.

In studying the past, deeds come to be estimated more with reference to their ultimate results and as factors in universal progress, and less as personal efforts; just as more and more the personal merges into the universal in all lines of endeavor. Viewed in this light of ultimate results an imperishable and increased lustre envelops the name of Sir Walter Raleigh as the pioneer and faithful promoter of English colonization in America. The recognition of his services by the people who reap the reward of his labors has ever been too meagre. A portrait here and there, the name of the capital city in a State, a mention among other explorers on a tablet in the National Library, the name of a battleship, and a few pages in history, help to remind us of his association with this nation. Perhaps a few may recognize his personal colors—red and white—in the binding in this book, and his Coat of Arms in the heraldic device which ornaments the cover, and which are mentioned “lest we forget” one we should honor.

The present and ever increasing greatness of these United States is due to the efforts of this remarkable man, who so wondrously combined in

one personality the attributes of statesman, courtier, soldier, scientist, poet, explorer, and martyr. Isabella of Spain offered her jewels to aid Columbus, and the deed has been lauded and celebrated as of international value, yet it contained no touch of personal sacrifice. She was never deprived of her jewels, and while her generous offer proved her faith in the theories and ability of Columbus, it brought to her no suffering. On the other hand, the efforts of Sir Walter Raleigh were at his own expense, and entailed financial disaster on him in the end. That he sought to extend the power of England must be admitted by those who correctly estimate his character; yet no one will deny that he was the most important factor in the colonization of America by the English. Spain, France, and England contended long for supremacy in the New World, but France failed to gain any permanent power, and Spanish dominance, as illustrated in South America and Mexico, was followed by slow progress. It was the English race, led by Raleigh, which has become the leading power and modern strength of America. Colony after colony he sent to the new land, and desisted not, even after the death of his half-brother and coadjutor, Sir Humphrey Gilbert. Disaster could not daunt so brave

a spirit, and with unsurpassed enterprise and perseverance he continued to send expeditions year after year to what is now the coast of North Carolina, but which was then called Virginia, and recognized as Raleigh's possessions. Much money was required, and when his own fortune was exhausted he transferred to what is known as the London Company his rights to the land, and by his advice they avoided his mistakes and made the next settlement at Jamestown instead of Roanoak Island.

These facts have been temporarily obscured by the moss of neglect, but they cannot be destroyed. They will ever remain the foundation-stones of the great structure known and respected among nations as the United States of America, and were laid by Sir Walter Raleigh at Roanoak Island, on the coast of North Carolina, which was then called Virginia. The intervening years have brought great results, those early struggles have ripened into success and greatness beyond Raleigh's most sanguine dreams. A new race has arisen, yet bearing the characteristics of the race from which it sprung. Our English ancestors, our heritage of English law and custom, of religion and home life, of language and ideals, all tempered by the development of new characteristics, bind us through him to England.

Sir Walter Raleigh was not an ordinary man. He was one of the most remarkable of a coterie of remarkable men whom a remarkable queen (Elizabeth) gathered around her, and to whom she owed much of the grandeur of her remarkable reign. Elizabeth's greatest gift was a capacity for discerning and using great minds, and she had the good fortune to find many around her at that period of time. Raleigh won her favor, and received from her many benefits, among which was the honor of knighthood with its emoluments, which she conferred. In the end her favor cost him dear, because his heart had the courage to be true to itself in love. Elizabeth never forgave him for loving, marrying, and being true until death to her maid of honor, the beautiful Elizabeth Throckmorton. That vain and jealous queen permitted no rivals, and she wished to reign over the heart of this man, who, handsome, brave, gallant, intelligent, and romantic, made an ideal courtier. His life at court was brilliant but brief. Love anchored a soul attuned to loftier deeds, and after his marriage his career as a courtier was eclipsed by his later exploits as a statesman, warrior, explorer, and author. He planned and participated in many expeditions which brought benefit to his queen and added to his own fortune,

yet none of his expeditions have borne such an ever-increasing harvest of results as those he sent to America. He began that work in 1584, and continued to send expeditions in 1585-1586-1587, until the invasion of England by the Spanish Armada forced him to other activities, and even then he sent two expeditions to the relief of the colonists, which, because of the exigencies of war, failed to reach America. In fact, the attitude of Spain towards England at that time was the greatest obstacle which militated against the success of his colonies. His ships and his valor were necessary to suppress and check the insolence and ambition of Spain, who designed to conquer England and become mistress of the world. By his valor, loyalty, and wisdom Raleigh was largely instrumental in bringing about the failure of those plans and in defeating the Spanish fleet, which had been boastingly named The Invincible Armada. Again his zeal and cool daring won for England the great victory of Cadiz, which has always ranked as the most remarkable achievement in the annals of naval warfare. With only seven ships he dashed in and destroyed a large Spanish fleet (fifty-five ships) in its own harbor with a dexterity and valor not surpassed even by Dewey at Manila nor by Schley at Santiago.

Spain was always his foe because she feared him, and it seems like the Nemesis of fate that three hundred years later the death-blow of Spain as a world power was dealt in Manila Bay by the nation which Raleigh strove so hard to plant, himself all unconscious of what the years were to bring. On that famous morning when Dewey startled the world and chastised Spain for her insolence and cruelty, the ship which fired the first shot in a battle destined to change the rating of two nations, the ship which first replied to the fire of the Spanish forts, as if answering the challenge of an old-time foe,—that ship was the Raleigh, named in honor of that great man by the nation he had fostered, and in that battle Raleigh's foe was humbled, Raleigh's fame perpetuated, and Raleigh's death avenged.

After the death of Elizabeth the star of Raleigh set. He whose most valiant work had been the defense of England against the attacks of Spain was falsely charged with treasonable negotiations with Spain, and after a farce of a trial was thrown into prison, where he remained more than twelve years. The only mitigations of the horrors of prison life were the presence of his devoted wife and his books. He had always been a student, and he spent the weary

hours of his long confinement in that companionship which is known only to those who really love books, and to such minds they prove a panacea for sorrow and injustice. During that imprisonment he wrote his famous “History of the World,” marking the eventful epoch by writing a history of the Old World at the same time that he was opening the gates of the future by planting English colonies in the New World. As soon as he was released from prison his mind returned to schemes of exploration. He made a voyage to South America, where new disasters befell him, and where his oldest son was killed. Shattered by grief and misfortune he returned to England, where his enemies had planned his certain downfall. Again he was sent to prison, but not for a long time, for soon his princely head paid the penalty which true greatness has too often paid to the power of a weak king. As a subject he was loyal and valiant, as a husband faithful and devoted, as a father affectionate and inspiring, as a scholar distinguished in prose and poetry, as a soldier he won fame and fortune, as a statesman he contributed to the renown of his sovereign's realm, and as a man he lived and died guided by the highest ideals. This was the man who spent a fortune trying to establish English colonies in North America, and

who sent repeated expeditions to the island of Roanoak, situated where the waters of the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds meet, on the coast of North Carolina, but which was then called Virginia.

The island wears a cluster of historic jewels which should endear it to all patriotic Anglo-Americans. To them it should be the most sacred, the best loved spot in all the United States. There the first English settlements were made which led to English supremacy in the New World. There the first home altar was reared and the first child of English parents in the United States was born and baptized. There the blood of Englishmen first dyed the sod of North America, and there the first attempts at English agriculture were made. There was enacted the tragedy of American colonization, the disappearance of Raleigh's Lost Colony, and there the sacrament of baptism was first administered in the United States. Roanoak Island is a beautiful place, with fertile soil and wild luxuriance of vine-covered forests which are enveloped in a deep solitude which has become dignity. Restless waters ebb and flow by its side, restless winds kiss its bare sand dunes, a genial sun brings to maturity its wealth of tree and vine and shrub. Protected from the storms which ravage the ocean beyond, it sleeps in quiet

beauty, content with its heritage of fame as the first home of the English race in America.

Its isolated position, its wild beauty, its tragic associations, its dignified repose, all seem to have set it aside from the rush of modern progress that it might become a shrine for the homage of a patriotic people.

The wonderful fertility of the soil of this island seemed a marvel to the early explorers, all of whom have testified to it. Ralph Lane, governor of the colony of 1585, in writing to Raleigh of the island and the surrounding country, declared it to be “the goodliest soil under the cope of heaven,” and that “being inhabited with English no realm in Christendom were comparable to it;” every word of which is true now, provided that the English who inhabit it follow the suggestions of nature and adopt horticulture as the developing means. The surrounding country as well as Roanoak Island has a wealth of climbing vines and clustering grapes which point instinctively to grape culture. Amadas and Barlowe (1584) wrote that they found the land “so full of grapes as the very beating and surge of the sea overflowed them, of which we found such plenty, as well there as in all places else, both on the sand and on the green soil, on the hills as on the plains, as well

A Scuppernong Vineyard, Roanoak Island.as on every little shrub as also climbing towards the top of high cedars, that I think in all the world the like abundance is not to be found.”

Surely no other such natural vineyard was ever found outside the fabled Garden of the Gods!

Even in this generation an old resident of the Banks, an ante-bellum pilot on these waters, has testified that his grandfather could remember the time “when if a vessel were stranded on any of the beaches the crew could crawl to land on the grapevines hanging over where now there is only a dry sand beach.” Throughout the eastern part of that State (North Carolina) the grape riots in natural luxuriance and is luscious and fragrant. Many varieties remain wild, while others have been improved by cultivation. The three finest native American grapes, the Catawba, the Isabella, and the Scuppernong, are all indigenous to the soil of North Carolina. The Catawba, native to the banks of the river Catawba, from which it takes its name, is still found wild in North Carolina, while it has become celebrated at the North as a table-grape, and in Ohio as a wine-grape. In its adopted home it has revolutionized land values because of the money value of the product. The Isabella grape, so generally cultivated for table use, is thought to be a

hybrid between the Burgundy and the native fox-grape of the Carolinas. The tradition runs that the Burgundy was brought to South Carolina by the Huguenots, and that cuttings from this hybrid were brought to North Carolina and successfully propagated. Mrs. Isabella Gibbs, for whom this wellknown grape was named, carried a vine from North Carolina to Long Island, where it attracted attention because of its hardiness.

To the people of the South Atlantic coast the Scuppernong is by far the most important of the native grapes, for while it refuses to flourish away from its native home, yet its great possibilities as a wine-grape are beginning to be appreciated. All the early explorers gave it special mention. Hariot in his famous Narrative wrote, “There are two kinds of grapes that the soil does yield naturally, the one is small and sour, of the ordinary bigness of ours in England; the other far greater and of himself luscious sweet. When they are planted and husbanded as they ought, a principal commodity of wines by them may be raised.” (Hakluyt, 1586.) Lawson in his history (1714) describes several varieties, and dwells on the abundant supply of grapes and the great tangles of green vines. He wrote of a native white grape, which many in that day thought existed only

Old “Mother” Scuppernong Vine.in his imagination; but it was a reality and was the now well-known Scuppernong, whose fame history and tradition both perpetuate, and whose real worth, greater than its legendary fame, is now being recognized and appreciated. There are several varieties of the Scuppernong, all luscious and yielding rich juices, and when ripe they fill the air with a fragrance unknown to any other grape.

The first Scuppernong vine known to history was found on the mainland of the North Carolina coast by Amadas and Barlowe on their first voyage (1584). Tradition relates thay they transplanted this vine to Roanoak Island. On this island there still flourishes an old vine, which despite its gnarled body and evident age continues to bear fruit. It is claimed that it is the same vine Amadas and Barlowe planted. Some insist that it was planted by Sir Walter Raleigh himself, but as that famous knight did not realize his wish to visit his new possessions in North America, the honor of having planted the vine must revert to Amadas and Barlowe. It seems to be endowed with perennial youth, and the harvest from its branches is an annual certainty.

What the early explorers testified as to the abundant supply of grapes on the Carolina coast, and the propitious conditions existing for the propagation of

the vine, is equally true to-day. The manifest destiny of North Carolina as the rival of Southern France in the production of wines seems to be inevitable. The marvel is how it has been so long delayed after Hariot's special mention of such possibilities. Hariot was a close observer with a practical mind, and the presence of an indigenous supply of material to sustain an important industry suggested to him that the people coming to this grape-laden land might establish such an industry to their advantage. The delay of the development of grape-culture in its native home can only be explained on the theory that when nature boldly invites, man becomes shy. This indifference to grape-culture is peculiar to America, for in Europe all the aristocracy who are land-owners, where the climate makes it possible, are cultivators of the grape, take great pride in their wines, boast of their rare and fine vintages, and hold the making of wine as one of the fine arts.

The original Scuppernong has white skin, white pulp, white juice, and makes a white wine. Other varieties have dark purple skins and yield a reddish juice which makes a red wine. The dark varieties are said to be seedlings from the original white variety, and tradition explains the metamorphosis in this way.

In the magic spring made famous in the legend of The White Doe, after the blood of Virginia Darehad melted from the silver arrow into the water of the spring, then the water disappeared. As the legend says:

“Dry became the magic fountain,Leaving bare the silver arrow.”Then while O-kis-ko looked on in wonderment he saw

“a tiny shoot with leafletsPushing upward to the sunlight.”Tradition says that this “tiny shoot with leaflets” was a young seedling of the Scuppernong which had sprouted in the edge of the water, and it was not seen by O-kis-ko until all the water had disappeared. Then he saw it and immediately associated its appearance with the magic arrow, and so left it “reaching upward to the sunlight.” After many days he returned to the spot—drawn by an irresistible longing, and covered the fatal arrow, which had brought him so much woe, with earth and leaves to hide it from his sight. The earth and leaves furnished the necessary nourishment to the tiny vine, which reached out with strength and vigor, and finding friendly bushes upon which to climb, it soon made a

sheltering bower above the spot where had bubbled the magic spring. This tiny green bower became the favorite retreat of Virginia Dare, and marvel on the wonders of her death. Then it came to pass that when fruit came upon this vine, lo! it was purple in hue instead of white like the other grapes, and yielded a red juice. Full of superstition, and still credulous of marvels, red—it was the semblance of blood, Virginia Dare's blood, absorbed from the water (in which it had melted from the arrow) by the vine, and yet potent for good. Surely it held some unseen power, for it combined in some mystic way through the mysterious earth at his feet all the power of the magic spring, the power of the silver arrow, and the power of human blood consecrated through human love. He reverently drank the juice of this new vine, believing that it would in some way link him with the spirit of her he had loved and lost. Year after year he drank this juice and fed his soul on thoughts of love, making unconsciously a sacrament, and finding happiness in the thought that the blood of the maiden would feed his

spirit and lead him to her at last. To become good like her and to go to her became his highest hope. Aspiration had been born in his soul, and quickened by love it could not die, but led him blindly to strive to reach her, and such striving is never in vain.

Another fact that should be enshrined in the hearts and perpetuated in the memorials of the nation, is that on Roanoak Island the first Christian baptism in the United States was administered. By order of Sir Walter Raleigh, Governor White, and the following Sunday Virginia Dare, the granddaughter of Governor White, was baptized, both events being officially reported to Raleigh. In this day of religious freedom any enforced adoption of religious forms shocks our pious instincts. Yet baptism has always been considered necessary to salvation, and in the past the zeal of Christians for the salvation of their fellowmen often assumed the form of mild force. We read where the Spaniards, always religious fanatics, administered the Holy Sacrament to thousands in Central America and Mexico at the point of the sword; their zeal misleading them to force upon those less enlightened than themselves the hope of that heaven which they believed to be accessible

only through certain Christian rites. So to order the baptism of an Indian chief seems a simple, kindly thing, and most probably 1614. She was a captive at the time and held as a hostage to induce Jamestown.

Despite the fact that Virginia Dare was baptized twenty-seven years earlier than Washington as receiving the first baptism in the colonies. Buried in the annals of that time lies the fact that twenty-seven years before any colonist even came to Jamestown, Virginia Dare was born and baptized, as the sequence of Christian birth and as the child of Christian parents. Virginia Dare was not a myth. She was a living, breathing reality, a human creature of good English descent, the granddaughter of the governor of the colonies, the daughter of the assistant governor, and a sharer in the mysterious fate of Raleigh's Lost Colony. The historical facts of her life and the legend of her fate and death are contained in the pages of “The White Doe.”

Her baptism would not have been mentioned in the records if it had not been official and proper. In a new land, surrounded by dangers and difficulties, with strange environment to divert the mind to other channels, it would have been easy and natural for her baptism to have been delayed if not altogether neglected amid the stress of events. Her prompt baptism and the official report of the event to Sir Walter Raleigh is convincing testimony to the presence of a chaplain at Roanoak.

THE FIRST BAPTISM IN THE WILDS OFAmerica!

How naturally the scene rises before us. The young mother, her heart thrilling with the mysteries of love and life, and elated with the joy of motherhood, alert to the dangers of the new land, and suspicious of the strange people among whom her blue-eyed treasure must live, yet yielding cheerfully to the busy smiling English women who had crossed the ocean with her, and now with womanly intuition ministered to her needs. We can picture them making tidy the confused household, and stilling the cries of the infant as they prepare her to receive the sign of the cross. We can almost picture them deliberating over a choice from among their limited

supply of vessels of one worthy to become the receptacle of the water to be used. It was on the Sabbath-Day, and the dedication to God of the wee creature who had so newly come among them was a fitting observance of the day. The solemn words of the ritual of the English Church, never before spoken in that primeval forest, must have awakened mysterious vibrations which linger yet and give to Roanoak Island that atmosphere of perpetual repose which envelops it. There must have come to those who witnessed the scene that holy Sabbath-Day, just as it comes now to those who view it from afar, a deep realization that the God of the English and the Great Spirit of the Indian are one and the same, then, now, and evermore. The One God to whom in baptism Virginia Dare was brought and in whose name Christ.

The mist of oblivion fades before the light of Truth, and Virginia Dare will be a shining jewel in the Chaplet of Memories which some day Christian America will place upon the tomb of the Past.

PREFACEA FAMILIAR knowledge of the history of one's own country increases patriotism and stimulates valor. For this reason the study of written records called history should be supplemented by research into myths, folk-lore, and legends. While the value of history lies ever in its truth, it must yet bear the ideals of the people who participated in the events narrated. Tradition was the mother of all history, and was necessarily robed in the superstitions of the era of which the tradition tells. History writers, jealously guarding the truth, have striven to banish all traditions which seemed colored by fancy or even freighted with a moral lesson. These exiled traditions, bearing the seed-germs of truth, cannot die, but, like wandering spirits, float down the centuries enveloped in the mists of superstition, until finally, embodied in romance or song, they assume a permanent form called legend and become the heritage of a people. Legends are the satellites of history because they have their

origin in the same events, and the history of all countries is interspersed with them.

The legend of The White Doe is probably the oldest and possibly the least known of all the legends which relate to the history of the United States. It is a genuine American legend, and the facts from which it had its origin form the first chapter in the history of English colonization in North America. Those facts are found in the repeated attempts of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish an English colony in the New World. The Spaniards were in Florida, the French were in Nova Scotia, but England had gained no possessions in North America when Raleigh began his efforts. This fact assumes more importance when we remember that civilization has made the greatest progress in those parts of America where the English became dominant. In South America, dominated by the Spaniards, civilization has made no strides, while in the United States a new nation has arisen whose ultimate destiny none may limit or foretell. As the gates of a new century open and disclose almost unlimited fields for human progress, this new nation, with an enthusiasm and courage born of success, has taken her place to lead in the eternal forward search for better opportunities

and higher life for the human race. All this grand destiny, all this ripening opportunity, like a harvest from a few seeds, is traced back, event after event, to the early struggles of those who braved the dangers of sea and forest in the attempts to colonize America. Those pioneer efforts, so generously promoted by Sir Walter Raleigh, though only partially successful, were the stepping-stones which later led to the better-known settlement of Jamestown, in Virginia. A brief résumé of those stepping-stones will make them familiar to all.

In 1584 Queen Elizabeth made a grant to Raleigh for all the land from Nova Scotia to Florida, which was called Virginia, in honor of the Virgin Queen, as Elizabeth was called.

The first expedition sent out under this grant was in the same year, 1584, and was entirely at the expense of Sir Walter Raleigh, as were all of the expeditions up to 1590. It was solely for the purpose of exploration, and was under the command of Amadas and Barlowe, who, after coasting along the Atlantic shores, entered Pamlico Sound and landed on the island of Roanoak, on the coast of the present State of North Carolina. They made the acquaintance of the tribes there

resident, explored the country on the coast, and returned to England to bear enthusiastic testimony to the delightsomeness of the country. They took with them back to England two native Indian chiefs, Manteo and Wanchese, who returned to America on a subsequent voyage, as the official records tell.

The following year, 1585, a colony of one hundred and seven men landed on this same island of Roanoak. They came organized to occupy and possess the land granted to Raleigh, and to secure such benefits therefrom as in those days were deemed valuable. They remained one year, exploring the country and trying to establish relations with the Indians. They built houses, planted crops, and looked forward to the arrival of more men and food, which had been promised from England. But no ships came, provisions grew scarce, and before the crops they had planted were mature enough to harvest, Sir Francis Drake, the great sea-rover of that day, appeared off the island with a fleet of vessels.

Knowing the dangers of that coast, he did not attempt to come to the island, but sent in to learn of the welfare of the colony, and offered to supply their immediate needs. They asked, among other

things, that their sick and weak men be taken back to England, that food for those who remained be given them, and for a vessel in which they might return home if they so desired, all of which Drake granted. But a dreadful storm arose, which lasted three days and drove the promised vessel out to sea, with a goodly number of the colonists and the promised food on board. Seeing thus a part of their number and their food gone, the remaining colonists became homesick and panic-stricken and begged Drake to take them all to England, which he did. Thus ended the first attempt at English colonization in North America.

Fifteen days after their departure Sir Richard Grenville arrived with three vessels, bringing the promised supplies, but found the men gone. Wishing to hold the country for England until another colony could arrive, he left fifteen men on the island with provisions for two years, and he returned to England. Those fifteen men are supposed to have been murdered and captured by the Indians, as the next colony found only some bones, a ruined fort, and empty houses in which deer were feeding.

The leaving of those fifteen men is considered the second attempt at colonization, and is recognized

as a failure. But all success is built only by persistent repetition of effort, and so, in 1587, another colony came from England to this same island of Roanoak. Among those colonists were seventeen women and nine children, thus proving the intention of making permanent homes, and the hope of establishing family ties which should for all time unite England and North America. A few days after the arrival of this colony at Roanoak, Virginia Dare was born,—she being the first child born of English parents on the soil of North America,—and because she was the first child born in Virginia she was called Virginia. Her mother, Eleanor Dare, was the daughter of John White, the governor of the colony, and the wife of one of the assistant governors.

The Sunday following her birth she was baptized, this being another fact of official record.

By Sir Walter Raleigh's command the rite of baptism had been administered, a few days earlier, to Manteo, an Indian chief, who had visited England with a returning expedition, as previously mentioned. This baptism of the adult Indian and of the white infant were the first Christian sacraments administered in North America, and are worthy of commemoration.

The colonists soon found that to make possible and permanent their home in a new land many things were needed more than they had provided. So at their urgent request their leader, Governor White, grandfather of Virginia Dare, consented to return to England to secure the needed supplies, with which he was to return to them the following year. When White reached England he found war going on with Spain, and England threatened with an invasion by the famous Spanish Armada. His queen needed and demanded his services, and not until 1590—three years later—did he succeed in returning to America. When at last he came the colonists had disappeared, and the only clue to their fate was the word “Croatoan,” which he found carved on a tree; it having been agreed between them that if they changed their place of abode in his absence they would carve on a tree the name of the place to which they had gone.

The arrival of those colonists, the birth and baptism of Virginia Dare, the return of White to England, the disappearance of the colony, and the finding of the word Croatoan, these facts form the record of that colony, the disappearance of which is a mystery which history has not solved.

But tradition illumines many periods of the past which history leaves in darkness, and tradition tells how this colony found among friendly Indians a refuge from the dangers of Roanoak Island, and how this infant grew into fair maidenhood, and was changed by the sorcery of a rejected lover into a white doe, which roamed the lonely island and bore a charmed life, and how finally true love triumphed over magic and restored her to human form,—only to result in the death of the maiden from a silver arrow shot by a cruel chieftain.

This tradition of a white doe and a silver arrow has survived through three centuries, and not only lingers where the events occurred, but some portions of it are found wherever in our land forests abound and deer abide. From Maine to Florida lumbermen are everywhere familiar with an old superstition that to see a white doe is an evil omen. In some localities lumbermen will quit work if a white deer is seen. That such a creature as a white deer really exists is demonstrated by their capture and exhibition in menageries, and to-day the rude hunters of the Alleghany Mountains believe that only a silver arrow will kill a white deer.

The disappearance of this colony has been truly called “the tragedy of American colonization,” and around it has hung a pathetic interest which ever leads to renewed investigation, in the hope of solving the mystery. From recent search into the subject by students of history a chain of evidence has been woven from which it has come to be believed that the lost colony, hopeless of succor from England, and deprived of all other human associations, became a part of a tribe of friendly Croatoan Indians, shared their wanderings, and intermarried with them, and that their descendants are to be found to-day among the Croatoan Indians of Robeson County, North Carolina.

(Those who desire to investigate this supposed solution of the mystery can easily secure the facts and the conclusions formed by those who have made a careful study of the subject.)

Of course, it can never be known certainly whether Virginia Dare was or was not of that number, but the full tradition of her life among the Indians is embodied in the legend of The White Doe.

Much has been written about the Indian princess Pocahontas, and much sentiment has clustered

around her association with the Jamestown colony, while few have given thought to the young English girl whose birth, baptism, and mysterious disappearance link her forever with the earlier tragedies of the same era of history. It seems a strange coincidence that the Indian maiden Pocahontas, friend and companion of the White Man, having adopted his people as her own, should sleep in death on English soil, while the English maiden, Virginia Dare, friend and companion of the Red Man, having adopted his people as her own, should sleep in death on American soil,—the two maidens thus exchanging nationality, and linking in life and in death the two countries whose destinies seem most naturally to intermingle.

The scattered fragments of this legend have been carefully collected and woven into symmetry for preservation. Notes from authentic sources have been appended for the benefit of searchers into the historical basis of the poem, which is offered to the public with the hope that it may increase interest in the early history of our home land and strengthen the tie which binds England and the United States.

SALLIE SOUTHALL COTTEN.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| FORGOTTEN FACTS AND FANCIES OF AMERICN HISTORY | i |

| PREFACE | 5 |

| PROLOGUE | 19 |

| THE SEEDS OF TRUTH | 23 |

| THE LEGEND OF THE WHITE DOE | |

| I.—THE REFUGEES | 31 |

| II.—THE PALE-FACE MAIDEN | 42 |

| III.—SAVAGE SORCERY | 46 |

| IV.—THE COUNTER-CHARM | 55 |

| V.—THE HUNT | 63 |

| VI.—THE SILVER ARROW | 72 |

| APPENDIX | 81 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| 1 “While within its bright'ning dimness, With the misty halo ’round her, Stood a beautiful white maiden” | FRONTISPIECE |

| 2 A Scuppernong Vineyard, Roanoak Island | x |

| 3 Old “Mother” Scuppernong Vine | xii |

| 4 Among the Scuppernongs.—A Modern Vineyard | xiv |

| 5 A “Virginia Dare” Vineyard | xvi |

| 6 The Arrival of the Englishmen in Virginia | 23 |

| 7 “The Fierce, Brawny Red Man is King of the Wold” | 24 |

| 8 The Land-of-Wind-and-Water | 32 |

| 9 Man-te-o, a Chiefe Lorde of Roanoak | 34 |

| 10 “Then a New Canoe he fashioned” | 52 |

| 11 The Magician of Po-mou-ik | 58 |

Frontispiece from an original drawing by May Louise Barrett.

Maps and remaining illustrations reproduced from Theodore de Bry's edition of “The True Pictures and Fashions of the People in that Parte of America now called Virginia,” 1590.

PROLOGUE

IN the tomb of vanished ages sleep th’ ungarnered truths of Time,Where the pall of silence covers deeds of honor and of crime;Deeds of sacrifice and danger, which the careless earth forgets,There, in ever-deep'ning shadows, lie embalmed in mute regrets.Would-be-gleaners of the Present vainly grope amid this gloom;Flowers of Truth to be immortal must be gathered while they bloom,Else they pass into the Silence, man's neglect their only blight,And the Gleaner of the Ages stores them far from human sight.Yet a perfume, sweet and subtle, lingers where each flower grew,Rising from the shattered petals, bathed and freshened by the dew;And this perfume, in the twilight, forms a mist beneath the skies,Out of which, like airy phantoms, legends and traditions rise;For the Seeds of Truth are buried in a legend's inmost heart,To transplant them in the sunlight justifies the poet's art.

THE SEEDS OF TRUTH

The arrival of the Englishmen in Virginia

THE SEEDS OF TRUTH

ROANOK, 1587

SHIMMERING waters, aweary of tossing,Hopeful of rest, ripple on to the shore;Dimpling with light, as they waver and quiver,Echoing faintly the ocean's wild roar.Locked in the arms of the tremulous watersNestles an island, with beauty abloom,Where the warm kiss of an amorous summerFills all the air with a languid perfume.Windward, the roar of the turbulent breakersWarns of the dangers of rock and of reef;Burdened with mem'ries of sorrowful shipwreck,They break on the sands in torrents of grief.Leeward, the forest, grown giant in greenness,Shelters a land where a fervid sun shines;Wild with the beauty of riotous nature,Thick with the tangles of fruit-laden vines.*From fragrant clusters, grown purple with ripeness,Rare, spicy odors float out to the sea,†Where the gray gulls flit with restless endeavor,Skimming the waves in their frolicsome glee.* See Appendix, Note a.† See Appendix, Note b.Out from the shore stalks the stately white heron,Seeking his food from the deep without fear,Gracefully waving wide wings as he risesWhen the canoe of the Indian draws near.Through reedy brake and the tangled sea-grassesWander the stag and the timid-eyed doe*Down to the water's edge, watchful and waryFor arrows that fly from the red hunter's bow.Fearless Red Hunter! his birthright the forest,Lithe as the antelope, joyous and free.Trusting his bow for his food and his freedom,Wresting a tribute from forest and sea,No chilling forecast of doom in the futureDaunts his brave spirit, by freedom made bold.Far o'er the wildwood he roams at his pleasure,The fierce, brawny Red Man is king of the wold.* * * * * *Lo! in the offing the white sails are gleaming,Ships from afar to the land drawing nigh;Laden with men, strong and brave to meet danger,Stalwart of form, fair of skin, blue of eye.* See Appendix, Note c.Boldly they land where the white man is alien;Women are with them, with hearts true and brave;Sadly they stand where their countrymen perished,*Seeking a home where they found but a grave.Friendly red hunters greet them with kindness,Tell the sad tale how their countrymen died,†Beg for a token of friendship and safety,†Promise in love and in peace to abide.Manteo's heart glows with friendly remembrance,He greets them as brothers and offers good cheer;No thrill of welcome is felt by Wanchese,‡His heart is bitter with malice and fear.Envying men his superiors in wisdom,Fearing a race his superiors in skill;Sullen and silent he watches the strangers,Whom from the first he determines to kill.Then the sign of the Cross, on the brow of the Indian,§Seals to the savage the promise of life;Sweet symbol of sacrifice, emblem of duty,Standard of Peace, though borne amidst strife:* See Appendix, Note d.† See Appendix, Note e.‡ Pronounced Wan-chess-e.§ See Appendix, Note f.Draped with the sombre, stained banner of Conquest,Dark with the guilt of man's murder and greed,Yet bright with God's message of love and forgivenessUnto a universe welded to creed.Gently the morning breeze tosses the tree-tops,Low ebbs the tide on the outlying sand;When a tiny white babe opens eyes to the sunlight,*Heaven's sweet pledge for the weal of the land.Babe of the Wilderness! tenderly cherished!Signed with the Cross on the next Sabbath Day;Brave English Mother! through danger and sorrow,For a nation of Christians thou leadest the way.Back to the home-land, across the deep water,Goes the wise leader, their needs to abate;†Leaving with sorrow the babe and its motherIn a strange land as a hostage to Fate.* See Appendix, Note g.† See Appendix, Note h.

Many long months pass in busy home-making,Sweet English customs prevail on the isle;Anxious eyes watch for the ship in the offing,Saddened hearts droop, but the lips bravely smile.Gone are the sweet dreamy days of the summer,In from the ocean the winter winds shriek;Dangers encompass and enemies threaten,Mother and child other refuge must seek.Mother and child, as in Bethlehem story,Flee from the hate of their blood-thirsty foes;Hopeless of help from their own land and people,They seek friendly tribes to find rest from their woes.To the fair borders of Croatoan Island,Over the night-covered waters they flee;Seeking for safety with Manteo's people,Leaving the word “Croatoan” on a tree.*Name of the refuge in which they sought shelter,Only the name of a tribe, nothing more;*Sign whereby those who would seek them might followTo their new home on the Croatoan's shore.* See Appendix, Note k.Why did they leave the rude fort they had builded?Why did they seek far away a new home?O innocent babe! Roanoak's lost nestling!How shall we learn where thy footsteps did roam?’Mid the rude tribes of the primeval forest,Bearing the signet of Christ on thy brow,Wert thou the teacher and guide of the savage?Who, of thy mission, can aught tell us now?Through the dim ages comes only the perfume,Left where the flowers of Truth fell to earth;With ne'er a gleaner to treasure the blossoms,Save the sweet petals of baptism and birth.Vainly we seek on Time's shore for thy footprints,Hid in a mist of pathos is thy fate;Yet of a life under savage enchantmentQuaint Indian legends do strangely relate.

THE LEGEND OF THE WHITE DOE

I

THE REFUGEES

IN the Land-of-Wind-and-Water,Loud the sea bemoaned its sameness;Dashing shoreward with impatienceTo explore the landward mysteries.On the sand the waves spread boldly,Vainly striving to reach higher;Then abashed by vain ambition,Glided to their ordained duty.There the pine-tree, tall and stately,Whispered low the ocean's murmur;Strove to soothe the restless watersWith its lullaby of sighing.There the tall and dank sea-grasses,From the storm-tide gathered secretsOf the caverns filled with treasures,Milky pearls and tinted coral,Stores of amber and of jacinth,In the caves festooned with sea-weed,Where the Sea-King held his revelsAnd the Naiads danced in beauty.In this Land-of-Wind-and-Water,Dowered with the sunshine's splendor,Juicy grapes grew in profusion,Draping all the trees with greenness,And the maize grew hard and yellow,With the sunshine in its kernels.Through the forest roamed the black bear,And the red deer boldly herded;Through the air flew birds of flavor,And the sea was full of fishes,Till the Red Man knew no hunger,And his wigwam hung with trophies.There brave Man-te-o, the Faithful,Ruled the Cro-a-to-ans with firmness,Dwelt in peace beside the waters,Smoked his pipe beneath the pine-tree,Gazed with pride upon his bear-skinsWhich hung ready for the winter.Told his people all the marvelsOf the Land-of-the-Pale-Faces;Of the ships with wings like sea-birdsWherein he had crossed the water;*Of the Pale-Face Weroanza†* See Appendix, Note l.† Elizabeth.

The Land-of-Wind-and-Water

The Land-of-Wind-and-Water

Whom he saw in her own country;Of her robes of silken texture,Of her wisdom and her power;Told them of her warlike peopleAnd their ships which breathed the lightning.How he pledged with them a friendship,Hoping they would come to teach himHow to make his people mighty,How to make them strong in battleSo the other tribes would fear them.And the dream of future greatnessFilled the Cro-a-to-ans with courage;And their hearts grew warm and friendlyTo the race of white-faced strangers.When bold white men came among them,To the isle of Ro-a-no-ak,Man-te-o, the friendly Weroance,Faithful proved to all his pledges.Smoked with them the pipe of friendship,Took their God to be his Father;Took upon his swarthy foreheadTheir strange emblem of salvation,*Emblem of the One Great Spirit,Father of all tribes and nations.* See Appendix, Note f.Man-te-o, the friend and brother,Bade them fear the false Wan-ches-e,And the Weroance Win-gin-a,Whose hearts burned with bitter hatredFor the men they feared in combat,For the strangers who defied them.When the Pale-Face, weak and hungry,Feeble from continued labor,Shivered in the blasts of winterWhich blew cold across the water,Then Wan-ches-e planned their ruin,With Win-gin-a sought to slay them.To the isle of Ro-a-no-ak,Where the Pale-Face slept unguarded,Sped the swift canoes of Red Men,Gliding through the silent shadows.As the sky grew red with dawning,*While they dreamed of home and kindred,Suddenly with whoop of murderWily Indians swarmed around them.Skill of Pale-Face, craft of Red Man,Met in fierce, determined battle;* See Appendix, Note m.

Man-te-o, a chiefe lorde of Roanoak

While within the Fort called RaleghMany arrows fell, like raindrops.Arrows tipped with serpent's poison,Arrows tipped with blazing rosin,Winged with savage thirst for murder,Aimed with cruel skill to torture.Threatened by the blazing roof-treeThen the Pale-Face crouched in terror;Saw the folly of resistance,Feared his doom, and fled for safety.Man-te-o, alert for danger,From afar saw signs of conflict;Saw the waves of smoke ascendingHeavenward, like prayers for rescue.Swift, with boats and trusty warriors,Crossed he then to Ro-a-no-ak;Strong to help his Pale-Face brothers,Faithful to his friendly pledges.As the daylight slowly faded,Hopeless of the bloody struggle,Stealthily the Pale-Face warriorsFled with Man-te-o's brave people.Left they then the Fort called Ralegh,Left the dead within its stockade;Sought another island refuge,Hoping there to rest in safety.Man-te-o sought for the mother,*She with babe there born and nurtured’Neath the shadow of disaster,In the Land-of-Wind-and-Water.“Come,” said he, “the darkness falleth,All your people must flee henceward;Wan-ches-e will show no mercy,You must not become his captive.Take the papoose from thy bosom,Call the white chief whom thou lovest,Haste with me upon the flood-tideTo my wigwam on Wo-ko-kon.”Noiseless, she amid the conflictSought her heart's mate to flee with her;Useless all the strife and courage,Useless all the rude home-making;Shrine for worship, fort for safety,Hope of future peace and plenty,All were vain; yet life we cherish,Far above all boons we hold it:So she hastened on her missionFor the life of self and loved ones.* Eleanor Dare.

“The fierce, brawny Red Man is king of the wold”

As they neared the island border,Pale-Face husband, child, and mother,Man-te-o in silence leading,Every sense alive to danger,Suddenly the Pale-Face fatherThought him of the parting cautionGiven by their absent leader:If they fled in search of safetyOn a tree to leave a token,Whereby he might surely find them,In the land which gave them shelter,When he came again to seek them.*By his side a sturdy live-oakSpread its green, protecting branches;Quick he strove to carve the tokenWhich should speak to all who followed.C. R. O., in bold, plain letters*Cut he in the tree's firm body,When a random, poisoned arrowPierced his heart, and he fell lifeless.With a smothered cry of horror,In an agony of sorrow,* See Appendix, Note k.She would fain have lingered near him,But that Man-te-o urged onward.If discovered, flight was futile,Weakness now meant worse disaster;She must save her helpless babyThough her heart be rent with anguish.Frantic with love's desolation,Strong with thoughts of home and father,With a woman's wondrous calmnessWhen great peril calls for action,Safe she placed the sleeping infant’Cross the brawny arms of Man-te-o,While with knife drawn from his girdleCarved she on another live-oakPlain, the one word “CROATOAN”*As a sign to all her people.Trusting all to savage friendship,Cutting hope with every letter,Praying God to guide her fatherTo the haven she was seeking.Trust is woman's strongest bulwark,All true manhood yields unto it.* See Appendix, Note k.

As her sad eyes turned upon himMan-te-o was moved with pityFor the brave and tender woman,Friendless in the land without him.On the brow of Pale-Face babyFirst he made the Holy Cross-Sign;Then upon the sad-eyed motherTraced the sign her people taught him;Then again the sacred symbolOutlined on his own dark forehead;And with open hand upliftedSealed his promise of protection;Linking thus his pledge of safetyWith her faith in Unseen Power.Mute with grief, she trusted in him;In his boat they crossed the water,While the night fell like a mantleSpread in mercy to help save them.When in Cro-a-to-an they landed,There they found the few survivorsOf that day of doom to many,Glad once more to greet each other.Man-te-o within his wigwamFrom the cold wind gave them shelter,Shared with them his furry bear-skins,Made them warm, and warmth gave courageTo meet life's relentless duties.Then he summoned all the people,Called the old men and the young men,Bade the squaws to come and listen,Showed the papoose to the women.They gazed on its tender whiteness,Stroked the mother's flaxen tresses;“’Tis a snow-papoose” they whispered,“It will melt when comes the summer.”Man-te-o said to the warriors:“Ye all know these Pale-Face peopleWhom Wan-ches-e sought to murder,They have often made us welcome.Brave their hearts, but few are living,If left friendless these will perish;We have store of corn and venison,They are hungry, let us feed them;They have lightning for their arrows,Let them teach us how to shoot it.They with us shall search the forest,And our game shall be abundant;

Let them teach us their strange wisdomAnd become with us one people.”And the old men, grave in counsel,And the young men, mute with deference,While the uppowoc* was burning,Pondered on his words thus spoken,And to Man-te-o gave answer:“All your words are full of wisdom;We will share with them our venison,They shall be as our own people.”From the isle of Ro-a-no-akThus the Pale-Face fled for succor,Thus in Cro-a-to-an's fair bordersFound a home with friendly Red Men.Nevermore to see white faces,Nevermore to see their home-land,Yet to all the future agesSending proof of honest daring;Forging thus a link of effortIn the chain of human progress.* Tobacco.II

THE PALE-FACE MAIDEN

NATURE feels no throb of pity,Makes no pause for human heartbreak;Though with agony we quiver,She gives forth no sign of feeling.Waxed and waned the moon, in season,Ebbed and flowed the tides obedient;Summers filled the land with plenty,Winters chilled the summers’ ardor.No winged ships gleamed in the offing;No Pale-Faces sought their kindred;In the Land-of-Wind-and-WaterRoamed the Red Man unmolested.While the babe of Ro-a-no-akGrew in strength and wondrous beauty;Like a flower of the wildwood,Bloomed beside the Indian maidens.And Wi-no-na Skâ* they called her,She of all the maidens fairest.* Literally, “first-born white daughter.”

In the tangles of her tressesSunbeams lingered, pale and yellow;In her eyes the limpid bluenessOf the noonday sky was mirrored.And the squaws of darksome featuresSmiled upon her fair young beauty;Felt their woman hearts within themWarming to the Pale-Face maiden.And the braves, who scorned all weakness,Listened to her artless prattle,While their savage natures softened,Of the change themselves unconscious.Like the light of summer morningBeaming on a world in slumberWas the face of young Wi-no-naTo the Cro-a-to-ans who loved her.She, whose mind bore in its dawningImpress of developed races,To the rude, untutored savageSeemed divinely ’dowed with reason.She, the heir of civilization,They, the slaves of superstition,Gave to her a silent rev'rence,Growing better with such giving.Oft she told them that the Cross-Sign,Made by Man-te-o before themWhen he talked to his own nation,Was the symbol of a SpiritGreat, and good, and wise, and loving;He who kept the maize-fields fruitful,He who filled the sea with fishes,He who made the sun to warm themAnd sent game to feed His children.If, when in their games or councils,They grew quarrelsome and angry,Suddenly among them standingWas a maiden like the sunrise,Making with her taper fingerThis strange sign which they respected;And without a word of pleadingStrife and wrath would no more vex them,While the influence of her presenceLingered ’round them like enchantment.Thus the babe of Ro-a-no-akGrew to be the joy and teacherOf a tribe of native heathen

In the land which gave her shelter.And the tide of her affectionsFlowed to those who gave her friendship;Whom alone she knew as human,Whom to her became as kindred.III

SAVAGE SORCERY

MAN-TO-AC, the Mighty Father,When he filled the earth with blessings,Deep within the heart of WomanHid the burning Need-of-Loving;Which through her should warm the agesWith a flame of mutual feeling,Throbbing through her sons and daughtersWith a force beyond their power.And this law of human loving,Changeless through unending changes,Fills each living heart with yearningFor another heart to love it;And against this ceaseless cravingCreed, nor clime, nor color standeth;Heart to heart all nature criethThat the earth may thrill with gladness.So the young braves of the nation,Thrilled with love for air Wi-no-na,Made rude ornaments to please her,

Laid the red deer at her wigwam.Brought her skins of furry rabbitsSoft and white as her own skin was;Robbed the black bear and the otterThat her bed might soft and warm be.And the children of the forestWere uplifted by such lovingOf a higher type of being,Who yet throbbed with human instincts.Brave O-kis-ko loved the maidenWith a love which made him noble;With the love that self-forgettingFills the soul with higher impulse.As the sun with constant fervor,Heat and light to earth bestowing,Seeks for no return of blessing,Feels no loss for all his giving,So O-kis-ko loved Wi-no-na,Gave her all his heart's rude homage,Felt no loss for all his giving,Loved her for the joy of loving.Scorned he all fatigue and dangerWhich would bring her food or pleasure;And each day brought proof of fealty,For his deeds were more than language.For her sake he tried to fastenTo his rude canoe white pinionsLike the winged ships of the white man,That with her he might sail boldlyOut towards the rosy sunrise,Seeking for her lost grandsire*For whose coming her heart saddened.Though his red companions mocked him,His endeavor pleased the maiden,And her eyes beamed kindly on him,Though no passion stirred her pulses.For sweet maiden hopes and fanciesFilled her life with happy dreamingEre her woman's heart awakenedTo O-kis-ko's patient waiting.Waiting for her eyes to brighten’Neath the ardor of his glances;Waiting for her soul to quickenWith the answer to his longing;Finding sweet content in silence,Glad each day to see and serve her.Now old Chi-co, the Magician,Also loved the fair Wi-no-na,* Governor White, of the lost colony.

All his youth to him returningAs he gazed upon her beauty.In his wigwam pelt of gray wolf,Antlers of the deer and bison,Hung to prove his deeds of valor;And he wooed the gentle maidenWith his cunning tales of prowess.She would not rebuke his boasting,Fearful lest her words offend him;For her nature kind and lovingCould not scorn the vaunting Chi-co.When he walked among the maidens,Gay with paint and decked with feathers,She would look on him with kindnessThat the others might not scoff him:She would smile upon his weakness,Though she did not wish to wed him.Chi-co's love was fierce as fireWhich from flame yields only ashes;Which gives not for joy of giving,But demands unceasing tribute,More and more to feed its craving.He grew eager and impatient,He would share with none her favor;All for him her eyes must brighten,Else his frown would blight her pleasure.When the young men played or wrestled,If O-kis-ko came out victor;Or returning with the huntersHe it was who bore the stag home;If with eyes abrim with pleasureSweet Wi-no-na smiled upon him,Or with timid maiden shynessDrooped her eyes beneath his glances,Then old Chi-co's heart would witherWith the fire of jealous fury,Till at length in bitter angerHe determined none should win her,As from him she turned in coldness.Wrapped in silence grim and sullen,Much he wandered near the water;With his soul he took dark counsel,Seeking for devices cruelFor the torture of his rivalAnd destruction of the maiden.Though he rarely used his power,Chi-co was a great magician.

He knew all the spells of starlightAnd the link ’tween moon and water;Knew the language of lost spiritsAnd the secret of their power;Knew the magic words and symbolsWhereby man may conquer nature.Long he plotted,—much he brooded,While he gathered from the waterMussel-pearls all streaked and piedèd,*All with rays like purple halos.Such pearls are the souls of NaiadsWho have disobeyed the Sea-King,And in mussel-shells are prisonedFor this taint of human frailty.When by man released from duranceThese souls, grateful for their freedom,Are his slaves, and ever renderGood or evil at his bidding.Chi-co steeped each one he gatheredIn a bath of mystic brewing;Told each purple, piedèd pearl-drop* See Appendix, Note n.What the evil was he plotted.Never once his purpose wavered,Never once his fury lessened;Nursing vengeance as a guerdonWhile the mussel-pearls he polished.Then a new canoe he fashioned,Safe, and strong, and deep he made it;*And then sought to work his magicOn the innocent Wi-no-na;Asked the maiden to go with himIn his boat across the water.“Come,” said he, “to Ro-a-no-ak,Where the waves are white with blossoms,Where the grapes hang ripe in clusters,Come with me and drink their juices.”And the innocent Wi-no-naListened to his artful pleading;Went with him in search of pleasure,Glad to show him friendly feeling.While with idle stroke they floatedTo the fragrant lily-blossoms,* See Appendix, Note o.

He a string of pearls gave to her,Smooth and polished, pied and purple.’Round her snowy neck she placed themWith no thought of harm or cunning;And with simple, maiden speechesFilled the time as they sped onward.To each pearl had Chi-co chanted,Each had bathed in mystic water,Each held fast the same weird power,Till the time grew ripe for evil.On the waves they could not harm her,There the Sea-King ruled them ever;But when on the shore she landedThey would work their evil mission.On the shore of Ro-a-no-akChi-co sent his boat with vigor.Lithe and happy she sprang shoreward,When,—from where her foot first lightlyPressed the sand with human imprint,—On—away—towards the thicket,Sprang a White Doe, fleet and graceful.His revenge thus wrought in safety,Drifting seaward Chi-co chanted:“Go, White Doe, hide in the forest,Feed upon the sweet wild-grasses;No winged arrow e'er shall harm you,No Red Hunter e'er shall win you;Roam forever, fleet and fearless,Living free and yet in fetters.”O fair maiden! born and nurtured’Neath the shadow of disaster!Isle of Fate was Ro-a-no-ak,In the Land-of-Wind-and-Water.Nevermore to fill with gladnessThe sad heart of stricken mother;Nevermore to hear the wooingOf the brave and true O-kis-ko.Gone thy charm of youthful beauty,Gone thy sway o'er savage natures;Doomed to flee before the hunter,Doomed to roam the lonely island,Doomed to bondage e'en in freedom.Is the seal of doom eternal?Hath the mussel-pearl all power?Cannot love thy fetters loosen?

IV

THE COUNTER-CHARM

MAN-TE-O and all his warriorsLong and far sought for Wi-no-na;Sought to find the sky-eyed maidenSent by Man-to-ac, the Mighty,To the Cro-a-to-ans to bless them,And to make them wise and happy.As a being more than mortal,As a deity they held her;And when no more seen among themLamentations filled the island.Through Wo-ko-kon's sandy stretches,Through the bog-lands of Po-mou-ik,Even unto Das-a-mon-que-peu,Hunted they the missing maiden;If perchance some other nation,Envious of their peace and plenty,Had the maiden boldly captured,For themselves to win her power.Louder grew their lamentationsWhen they found no trail to follow;Wilder grew their threats of vengeance’Gainst the tribe which held her captive.While they wailed the Pale-Face Mother,She who once was brave for love's sake,Weak from hardships new and wearing,Utterly bereft of kindred,Her heart's comfort thus torn from her,Died beneath her weight of sorrow.And a pity, soft and human,Though he knew no name to call it,Thrilled the Red Man as he laid her’Neath the forest leaves to slumber.But the wary, wily Chi-coTold his secret unto no one,While he listened to the stories,Strange and true, told by the huntersOf a fleet and graceful White DoeOn the banks of Ro-a-no-ak.And the hunters said, no arrowHowsoever aimed could reach her;Said the deer herd round her gathered,And where e'er she led they followed.The old women of the nationHeard the tales about this White Doe.

Children they of superstition,With their faith firm in enchantment,Linked the going of the maidenWith the coming of the White Doe.They believed in magic powers,They knew Chi-co's hopeless passion,So they shook their heads and whispered,Looked mysterious at each other,“Ho,” they whispered to each other,“Chi-co is a great Magician,Chi-co should go hunt this White Doe;He is not too old for loving;Love keeps step with Youth and Courage;Old age should not make him tremble.Timid is a doe, and gentleLike a maiden,—like Wi-no-na.Oho! Oho!” and they chuckled,Casting dark looks at old Chi-co,“He,” said they, “has ’witched our maiden.”When O-kis-ko heard the whispersOf the garrulous old women,Glad belief he gave unto themThat the Doe on Ro-a-no-akWas in truth the Pale-Face MaidenWrung from him by cruel magic.He was not a gabbling boaster,He could think and act in silence;And alone he roamed the islandSeeking this White Doe to capture,So that he might tame and keep herNear him to assuage his sorrow.All in vain,—no hand could touch her.All in vain,—no hunter won her.Up the dunes of Ro-a-no-akStill she led the herd of wild deer.Then O-kis-ko sought We-nau-don,The Magician of Po-mou-ik.*Gave him store of skins and wampum,Promised all his greed demanded,If he would restore the maiden,Break the spell which held her spirit.In his heart We-nau-don cherishedHatred for his rival Chi-coFor some boyhood's cause of anger,For defeat in public wrestling;And because of this he welcomed* See Appendix, Note s.

The magician of Po-mou-ik

Now the time to vent his malice.So he promised from enchantmentTo release the captive maiden.In the days of pristine nature,In the dells of Ro-a-no-ak,Bubbling from the earth's dark caverns,Was a spring of magic water.There the Naiads held their revels,There in secret met their lovers;And they laid a spell upon itWhich should make true lovers happy;For to them true love was precious.He who drank of it at midnightWhen the Harvest Moon was brightest,Using as a drinking-vesselSkull-bowl of his greatest rivalKilled in open, honest combat,And by summer sunshine whitened,He gained youth perennial from itAnd the heart he wished to love him.He who bathed within its waters,Having killed a dove while moaning,And had killed no other creatureSince three crescent moons had rounded;Vowing to be kind and helpfulTo the sad and weary-hearted:He received the magic powerTo undo all spells of evilWhich divided faithful lovers.In this spring had bathed We-nau-don,And he held its secrets sacred;But a feeling ever moved himTo make glad the heavy-hearted.So he showed unto O-kis-koWhere to find the magic water;With this counter-charm, he told himHow to free the charmed Wi-no-na:“In a shark's tooth, long and narrowIn a closely wrought triangle,Set three mussel-pearls of purple,Smooth and polished with much rubbing.To an arrow of witch-hazel,New, and fashioned very slender,Set the shark's tooth, long and narrow,With its pearl-inlaid triangle.From the wing of living heron

Pluck one feather, white and trusty;With this feather wing the arrow,That it swerve not as it flyeth.Fashioned thus with care and caution,Let no mortal eye gaze on it;Tell no mortal of your purpose;Secretly at sunset place itIn the spring of magic water.Let it rest there through three sunsets,Then when sunrise gilds the tree-topsTake it dripping from the water,At the rising sun straight point it,While three times these words repeating:Mussel-pearl arrow, to her heart go;Loosen the fetters which bind the White Doe;Bring the lost maiden back to O-kis-ko.With this arrow hunt the White Doe,Have no timid fear of wounding;When her heart it enters boldlyChi-co's charm will melt before it.”Every word O-kis-ko heeded,Hope, once dead, now cheered his spirit.From the sea three pearls he gathered;From the thicket brought witch-hazelFor the making of the arrow;From the heron's wing a featherPlucked to true its speed in flying.Patiently he cut and labored,As for love's sake man will labor;Shaped the arrow, new and slender,Set the pearls into the shark's tooth,Fastened firm the heron's feather,With a faith which mastered reason.In the magic spring he steeped it,Watching lest some eye should see it;Through three sunsets steeped and watched it;Three times o'er the charm repeatedWhile the sunrise touched the tree-tops;Then prepared to test its power.

V

THE HUNT

IN the Land-of-Wind-and-WaterLong the Summer-Glory lingered,Loath to yield its ripened beautyTo the cold embrace of Winter.And the greenness of the forestGave no sign of coming treason,Till the White Frost without warningHung his banners from the tree-tops.Then a blush of brilliant colorDecked each shrub with tinted beauty;Gold, and brown, and scarlet mingledTill no color seemed triumphant;And the Summer doomed to exileFled before the chilling Autumn.While the glow of colors deepened,The proud Weroance Win-gin-a,Chief of Das-a-mon-gue-pue land,Made a feast for all his people;Called them forth with bow and arrowTo a test of skill and valor.He was weary of the mysteriesWhispered of the famous White Doe,Whose strange courage feared no hunter,For no arrow ever reached her.“Ha!” said he, “a skilful hunterIs not daunted by a white doe;Craven hearts make trembling fingers,Arrows fail when shot by cowards.I will shoot this doe so fearless,Her white skin shall be my mantle,*Her white meat shall serve for feasting,And my braves shall cease from fearing.From the fields the maize invites us,Sturgeons have been fat and plenty.We are weary of fish-eating,We will feast on meat of white deer.”Messengers of invitationSent he to the other nations,Saying, “Come and hunt the White Doe,Bring your surest, fleetest arrows;We will eat the meat of white deer,We will drink the purple grape-juice,Burn the uppowoc in pipe-bowls,While we shame the trembling hunters.”* See Appendix, Note p.

But the Cro-a-to-ans kept silence,Sent no answer to his greeting.They believed the charmèd White DoeWas Wi-no-na Skâ’s pure spirit,Who in freedom still was happy,And they would not wound or harm her,They would shoot no arrows at her,Nor help feast upon her body.Then O-kis-ko answered boldly;“I will go and hunt this White Doe,I will shoot from my own ambush,I will take my fleetest arrow.”And the men and women wondered,For they knew his former loving.But O-kis-ko kept his secret,Showed no one his new-made arrow;’Round his shoulders threw a mantleMade of skins of many sea-gulls,So that he could hide his arrow,And no mortal eye could see itTill he sent it on its missionWinged with magic, fraught with mercy.Thus he went to Ro-a-no-ak,Love, and hope, and faith impelling,Conscious of his aim unerring,Trusting in the arrow's power.From Po-mou-ik came Wan-ches-e,For the hunt and feast impatient,Boasting of his skill and valor,Saying in his loud vainglory:“I will teach the braves to shoot deer,Young men now are not great hunters,Hearts like squaws they have within them,Nothing fears them but a papoose.”Wan-ches-e had crossed the water*In the ships with wings like sea-birds,And the Pale-Face Weroanza,Whom he saw in her own country,Him to please and show her friendship,Gave an arrow-head of silverTo him as a mark of favor.This he now brought proudly with him,As of all his arrows fleetest;Bearing in its lustrous metal,As he thought, some gift of power* See Appendix, Note l.

From the mighty WeroanzaWhich would bring success unto him;And the warriors all would praise himAs around the feast they gathered,Saying as he walked among them:“There is none like brave Wan-ches-e,He can bend the bow with firmness,He has arrow-points of silver,And the White Doe falls before him.”And he polished well the arrowWhich he thought would bring him praises.Where the deer were wont to wanderAll the hunters took their stations,While the stalkers sought the forest,From its depths to start the deer-herd.Near the shore Win-gin-a lingeredThat he first might shoot his arrow,And thus have the certain gloryOf the White Doe's death upon him.By a pine-tree stood Wan-ches-eWith his silver arrow ready;While O-kis-ko, unseen, waitedNear by in his chosen ambush,Where he oft had watched the White Doe,Where he knew she always lingered.Soon the stalkers with great shoutingStarted up the frightened red deer;On they came through brake and thicket,In the front the White Doe leading,With fleet foot and head uplifted,Daring all the herd to follow.Easy seemed the task of killing,So Win-gin-a twanged his bow-string,But his arrow fell beside herAs she sprang away from danger.Through the tanglewood, still onward,Head uplifted, her feet scorningAll the wealth of bright-hued foliageWhich lay scattered in her pathway.Up the high sand-dunes she bounded,In her wake the whole herd followed,While the arrows aimed from ambushFell around her ever harmless.On she sped, towards the water,Nostrils spread to sniff the sea-breeze;

Through the air a whizzing arrowFlew, but did not touch the White Doe;But a stag beside her boundingWounded fell among the bushes,And the herd fled in confusion,Waiting now not for the leader.On again, with leaping footsteps,Tossing head turned to the sea-shore;For one fatal minute standingWhere the White Man's Fort had once stood;In her eyes came wistful gleamingsLike a lost hope's fleeting shadow.While with graceful poise she lingered,Swift, Wan-ches-e shot his arrowAimed with cruel thought to kill her;While from near and secret ambush,With unerring aim, O-kis-koForward sent his magic arrow,Aimed with thought of love and mercy.To her heart straight went both arrows,And with leap of pain she boundedFrom the earth, and then fell forward,Prone, amidst the forest splendor.O-kis-ko, with fond heart swelling,Wan-ches-e, with pride exultant,To the Doe both sprang to claim it,Each surprised to see the other.Suddenly, within the forest,Spread a gleaming mist around them,Like a dense white fog in summer,So they scarce could grope their pathway.Slowly, as if warmed by sunbeams,From one spot the soft mist melted,While within its bright'ning dimness,With the misty halo ’round her,Stood a beautiful white maiden,—Stood the gentle, lost Wi-no-na.Through her heart two arrows crosswisePierced the flesh with cruel wounding;Downward flowed the crimson blood-tide,Staining red the snow-white doe-skinWhich with grace her form enveloped,While her arms with pleading gestureTo O-kis-ko were outstretching.As they gazed upon the vision,All their souls with wonder filling;

While the white mist slowly melted,Prostrate fell the wounded maiden.Then revealed was all the myst'ry,Then they saw what had befallen.To her heart the magic arrowFirst had pierced, and lo! Wi-no-naOnce more breathed in form of maiden.But while yet the charm was passingCame the arrow of Wan-ches-e;To her heart it pierced unerring,Pierced the pearl-inlaid triangle,Struck and broke the shark's tooth narrow,Charm and counter-charm undoing;Leaving but a mortal maidenWounded past the hope of healing.Woe to love, and hope, and magic!Woe to hearts whom death divideth!While upon her bleeding bosomFatal arrows made the Cross-Sign,Wistful eyes she turned to Heaven;“O forget not your Wi-no-na,”Whispered she unto O-kis-ko,As her soul passed to the silence.VI

THE SILVER ARROW

FEAR seized on the bold Wan-ches-eWhen he saw the Pale-Face maidenStanding where had poised the White Doe,Where the White Man's Fort had once stood.He knew naught of magic arrows,Nor O-kis-ko's secret mission;He saw only his own arrowPiercing through her tender bosom,Never doubting but the wonderWhich his awe-struck eyes had witnessedHad been wrought by his own arrow,Silver arrow from a far land,Fashioned by the skill of Pale-Face,Gift of Pale-Face WeroanzaTo a race she willed to conquer.All his hatred of the Pale-Face,Fed by fear and superstition,To him made this sudden visionSeem an omen of the future,

When the Red Man, like the White Doe,Should give place unto the Pale-Face,And the Indian, like the white mist,Fade from out his native forest.All his courage seemed to weakenWith the dread of dark disaster;And with instincts strong for safetyFled he from the place in terror.Love hath not the fear of danger,And O-kis-ko's faith in magicKept him brave to meet the changesWhich had each so quickly followed.For he saw the human maidenWhere had stood the living White Doe;And he knew his hazel arrow,Charmed with all We-nau-don's magic,Had restored the lost Wi-no-naTo reward his patient loving.But the conflict of two arrows,Bringing death unto the maiden,Was a deep and darksome myst'ryWhich his ignorance could not fathom.All the cause of his undoingSaw he in the silver arrow;So with true love's tireless effort,Quick he strove to break its power.From her heart he plucked the arrow,Hastened to the magic water,Hoping to destroy the evilWhich had stilled the maiden's pulses.In the sparkling spring he laid itSo no spot was left uncovered,So the full charm of the waterMight act on the blood-stained arrow.As the blood-stains from it melted,Blood of Pale-Face shed by Red Man,Slowly, while he watched and waited,All the sparkling water vanished;Dry became the magic fountain,Leaving bare the silver arrow.Was it thus the spell would weakenWhich had wrought his love such evil?Would she be again awakenedWhen he sought her in the thicket?Must he shoot this arrow at herTo restore her throbbing pulses?

Must he seek again We-nau-donTo make warm her icy beauty?While he of himself sought guidance,Sought to know the hidden meaningOf the mysteries he witnessed;Lo! another mystic wonderMet his eyes as he sat musing.From the arrow made by Pale-Face,As th’ enchanted water left it,Sprang a tiny shoot with leafletsPushing upward to the sunlight.Did the arrow dry the fountainWith the blight of death it carried?Or in going, had the waterLeft a charm upon the arrow?Did the heart-blood of the Pale-FaceFrom the arrow in the waterCause the coming of the green shoot,Which reached upward to the sunlight?All O-kis-ko's love and courageCould not give him greater knowledge.Savage mind could not unravelAll the meaning of this marvel.Fear forbade him touch the arrowLest he should destroy the green shoot;So he left the tender leafletsReaching upward to the sunlight,Sought again the lifeless maidenFor whose love his soul had hungered;Knelt beside her in the forest,With the awe of death upon him,Which in heathen as in ChristianMoves the human soul to worship.All his faith in savage magicTurned to frenzy at his failure;And the helplessness of mortalsPressed upon him like a burden;While a mighty longing seized himFor a knowledge of the Unknown,For a light to pierce the SilenceInto which none enter living.And unconsciously his spiritRose in quest of Might Supernal,Which should rule both dead and living,Leaving naught to chance or magic;Which should seize the throbbing pulsesEbbing from a dying mortal,And create a higher being