A Wreath from The Woods of Carolina

11 COLOUR PLATES

LITHOS BY SARONY, MAJOR & KNAPP

CHARLES R. SANDERS, JR.Americana-Southeastern States

123 Montgomery Street

Raleigh, North Carolina

Personal Address Label

THE HONEYSUCKLE. LUPINE & WILD PINKS

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

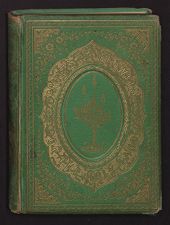

A WREATH FROM THE WOODS OF CAROLINA. ILLUSTRATED WITH Colored Engravings of Native Wild Flowers.NEW YORK:General Protestant Episcopal Sunday School Union,and Church Book Society,762 BROADWAY.1859.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1858, by the General Protestant Episcopal Sunday School Union, and Church Book Society, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York.

William Denyse, STEREOTYPER AND ELECTROTYPER, 183 William Street, N. Y.

Pudney and Russell, PRINTERS, 79 John Street, N. Y

PREFACE.The writer of these stories has always considered Flowers a most happy and charming medium through which to direct the opening minds of children to love and adoration of their great Creator. Prompted by this consideration, and hoping they will afford pleasure as well as profit to the youthful reader, she now presents them in a volume, illustrated with engravings of the beautiful Wild Flowers connected with each story.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Bessie Blue-Bell | 7 |

| May Queen | 19 |

| The Cup of Cold Water | 27 |

| The Magnolia and Violet | 41 |

| The Trumpet Flower | 52 |

| The Triumph of Truth | 64 |

| The Lily of the Valley | 81 |

| The Clematis and Woodbine | 96 |

| Rhene, or the Wild Crab Blossom | 110 |

| Forget-me-Not and Morning Glory | 143 |

| Modesty | 152 |

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

THE BLUE JESSAMINE

A WREATH FROM THE WOODS OF CAROLINA.

I. Bessie Blue Bell.

“Our Father who art in Heaven.”

On the borders of a small creek, running into the Trent River, just out of New-Bern, dwelt a blind widow, with two small children—a little girl eight years old, and a little boy just three.

This widow was a good woman, and taught her children to love God, and pray to Him, as soon as they could lisp His name.

She was quite young, and, although blind, was very lovely—her countenance being expressive of great gentleness

and benignity. Her children's names were Bessie and Edward.

Little Bessie's thoughts seemed to be centred in one untiring effort to amuse and console her sightless parent. This good girl never rested till she had learned to read, that she might beguile and sweeten the lonely hours of her blind mother, by reading to her from the Bible, and other good books, which she had so much delighted in before she lost her sight. Morning, noon, and night found this young girl on her cricket at her mother's knee reading her chapter—and, oh, what a cordial it was to that mother's heart! In the morning, as soon as Bessie was dressed, she said her prayers, read her Bible to her mother, and then tripped out into a beautiful wood near by, and culled an apronful of flowers; and returning, placed them one by one in her hand, describing the beauties of each in her simple, child-like way, while she inhaled its rich perfume; prattling all the while of the bright blue sky, the soft sweet air, the music of the birds, and the beauty and fragrance of the woods, till her blind mother really seemed to enjoy them all, as much as Bessie herself.

And now, when these precious duties were performed, she partook of the morning's repast, with that dear

mother and her little brother, while the silvery tones of her innocent voice still filled the gentle soul of her mother with the sweet music of joy and thankfulness. The repast being ended, Bessie took another kiss from her dear ones, and then tripped gleefully off to school, where she strove to make herself wiser every day, and more capable of enlivening the spirit and lighting the path of her who sat in her blindness at home, waiting for her return.

At noon, when she entered her peaceful home, the first thing she did, after kissing her dear mother, was to resume her seat at the accustomed place, and read another chapter in the Bible; while her heart swelled with glad praise and gratitude to her “Father in Heaven,” that she was thus enabled to comfort and cheer the lonely hours of that beloved mother.

Thus, day by day, did this good child verify the words of the blessed Saviour—“Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings Thou hast perfected praise.” And so did she beguile the lonely hours of the patient, pious woman, on whose knees, and from whose dear lips, this little lamb had learned to love “the Good Shepherd.”

“I wish I could see your happy face, my child,” said her mother to her one day, when Bessie was more than

usually joyous, and eloquent in her praises of the surrounding beauties of nature.

“Do but smell this Blue Bell, dear mother,” said Bessie; “just like its perfume is the face of your child, grateful and joyous.”

“Ah, yes!” said her mother, “here is your favorite—the beautiful, the fragrant blue jessamine; there surely is, in its perfume, something so like the purity and innocence of my little daughter—so enlivening, so like incense meet for Heaven—I can well imagine it an emblem of her sweet face. The Blue Bell is really and peculiarly worthy of your guileless love, my child. It is a princess among flowers. It was meet my darling should have chosen it for her favorite.”*

One morning Bessie rose very early, before her mother was awake. She seemed to sleep so very sweetly—a smile played round her placid lips, and the little child wondered if mamma was not in her sleep beholding the dear Blue Bell, and the many beautiful flowers her little daughter

*The Blue Bell.—Petals delicate white, edged with deep fringed violet, shaded gradually into the white centre. Stamens dense, high, delicate straw color. Perfume, delicious—resembling the violet, but more lively. Color, a variety of shades—some delicate blue, some deep purple—violet predominates. An annual.had placed in her hand, and described to her. And the thought, too, flashed through her guileless heaven-taught mind—

“Perhaps mamma is looking at the beautiful undying flowers of Paradise; it may be that her spirit has ascended to the regions of the blest, and she beholds her Saviour, and ‘Our Father in Heaven.’ I would not for the world wake her from the glorious view. Sleep on, dearest mother, sleep on.”

And the little child dressed herself noiselessly, said in quiet her innocent prayers, read her Bible, and then hastened out into the beautiful wood near by, intent on giving her dear mother a sweet surprise, by guiding her hand into her apron of fresh dewy flowers, just as she woke from her sleep.

Now, the cottage was on a green slope, extending to the margin of the creek, over which was a bridge, and from the bridge extended a causeway over a marsh some fifty yards, to the “Wilderness of Sweets,” as this flowery wood was called.

Little Bessie never feared to cross the bridge or marsh alone, after having said her prayers, for she said to herself, “ ‘Our Father in Heaven’ will take care of me.”

So on she went after she reached the woods, singing

merrily, plucking the choicest and most beautiful flowers of every hue, and filling her apron as fast as she could; but, alas, she found not the Blue Bell!

“Oh, dear!” sighed Bessie, “I must not return without mamma's favorite flower. She will not think she sees me, if she does not smell the dear Blue Bell.” So on and eagerly she advanced, deeper and deeper, amid the tangled vines and dark, thick foliage of the overhanging trees. “Oh,” said she, again and again, “I cannot return without the blue jessamine, just one for dear mamma.”

So, on and still on flew Bessie, her bright, quick, anxious eyes peeping into every mass of bushes, or cluster of vines or flowers, in hopes of finding her favorite. But, alas, she found it not. So intent was she on the search, she did not perceive that the sun had climbed to his meridian, and dried up all the dew, and that all the pretty flowers in her apron were withered and faded; and then, in a short time, the little child found that her tiny feet were aching and swollen, and that she was sick and faint with hunger.

All at once it occurred to her she had lost her way. She stared wildly around, and endeavored to retrace her steps; but, alas, there was no appearance of a path,

and no opening in the dense forest, the thick tangled underwood.

Bessie looked up to the bright blue sky, and thought, as she gazed on the glorious sun—

“Ah! I am not alone; yon bright sun that shines on me, shines too on the cottage of my dear mother. I am not alone; ‘Our Father who is in Heaven’ sees me, and will take care of me.” So little Bessie, being very thirsty, hastened to a clear, bubbling spring, and drank out of the hollow of her tiny hand, and then, seating herself on the grass, bathed her swollen feet. After she had rested herself awhile she arose, and searching about, found some berries, which she ate heartily; and when her hunger was gone, with an innocent, grateful heart, she seated herself to rest and think of her dear mamma and little brother.

“Alas!” said she, “my poor mamma! She will think she has lost her little girl. Perhaps she will think I am drowned in the creek, or some wild beast has devoured me, or some serpent stung me to death. Poor, dear mamma!” And Bessie wept bitterly when she thought of her grief. At length she knelt down on the grass, raised her innocent hands and weeping eyes to Heaven, and prayed earnestly to “Our Father who is in Heaven.” After this,

she became calm, confiding, and even cheerful. Again she searched the bushes for the sweet Blue Bell.

And now the sun went down, and the bright stars came twinkling at Bessie through the moving foliage. She chatted awhile with the little stars, and then, being very weary, she said her prayers, and laid her down on the soft grass, beneath a thick-leaved cedar, and slept as tranquilly as if she were in her mother's cottage.

Nor yet in her slumbers did the Good Shepherd forget this little lamb of His fold. In her dreams she was gathering flowers, and rejoicing amid their fragrance and beauty, while gentle angels, with snowy wings and radiant faces, held each a hand of the innocent child. And, indeed, it was well that Bessie had prayed to “Our Father in Heaven.” An enormous rattlesnake emerged from the thicket, and coiled himself near the sleeper—so near, that had she moved, his fatal fangs might have been fastened in her tender flesh. A sudden noise in the woods startled the terrible reptile, and he instantly darted into the bushes, giving little Bessie's arm a stroke with his tail, and she woke in time to see his fast receding form, as it vanished in the briers.

The good little girl instantly arose, and falling on her knees, before “Our Father who is in Heaven,” poured

forth her gratitude for this escape from death, in the silent night—and then calmly laid herself down again to sleep. Again, in her dreams, she sought for her home. Two gentle angels, holding each a hand of the little wanderer, led her through the thick bushes of the pathless woods, to the arms of her beloved mother.

Just as the rosy-fingered morning was unbarring the gates of light, to let forth the glorious sun, and the mocking-bird, perched on the topmost bough of the cedar, was pouring forth his rich and varied notes of praise, little Bessie awoke; and, with a blithe and trusting heart, joined with that melodious song.

“Sing on, sweet bird, I'll join with thee—Our notes shall fill the rosy sky;Before the morning star, shall weWaft our Creator's praise on high.”Then she said her prayers, but she greatly missed the beloved Bible she was wont to read each morning, though she sat down and thought over the beautiful beatitudes of the blessed Jesus, and felt a peaceful confidence in “Our Father who is in Heaven,” and a consoling belief that He would send the same bright messengers she saw in her dreams, to guide her footsteps homeward.

Bessie now went cheerfully to work, gathering berries

for her breakfast. As soon as she had eaten, she set off in search of her mother's cottage. She directed her steps toward the rising sun.

All was bright and joyous. The birds singing, the flowers blooming, the zephyrs fanning the leaves gently but cheerily—the dew-drops glittering in the sunbeams, as little Bessie glided on cautiously among the matted vines and shrubbery, hoping soon to find the woods open and see the white cottage appear.

She could not resist her old habit of gathering flowers, as usual at this delightful hour.

“Oh,” cried she, at last, “there is a beautiful Blue Bell!” She bounded forward to pluck the flower, and lo! at that moment, through an opening in the woods, the dear cottage of her mother was in sight!

Oh, how her heart leaped with joy! Her little feet seemed to have wings to them, so rapidly were the marsh, the bridge, the green slope passed over, and then, Bessie was indeed at her own door.

While she was enjoying the rapture of her fond mother's embrace, something seemed to bind her around the knees—and what do you think it was, my dear readers? It was her sweet, affectionate little brother, who was clasping his chubby arms about his darling

sister, while he shouted with joy at her safe return home.

“Let us return thanks to our Father in Heaven,” said the blind widow to her children, “for all His goodness, especially for preserving and restoring my darling little daughter to her home again.”

And then, the pious mother knelt down between her two young lambs of Christ's fold, and poured forth her gratitude to “Our Father who is in Heaven,” for his infinite mercy and goodness, while their little hands and hearts were raised in meek, innocent, and doubtless acceptable devotion to “the Good Shepherd.”

Soon after they had risen from their knees, the mother said—

“I smell the Blue Bell! surely, Bessie, you did not stop to pluck one at such a time?”

“Oh, yes, dear mother,” said Bessie, “it was the darling Blue Bell that showed me the way out of the woods. As I flew to pluck it, there was our sweet cottage just in my view.”

Little Bessie now sat down by her mother, and told her all that had befallen her since she left her side the morning before, and then read her chapter as usual, before breakfast.

“You shall be called Bessie Blue Bell,” said the widow, smiling; and ever after she went by that name, sure enough.

Bessie grew up to be a good and useful woman, and was always a comfort and delight to her blind mother, who had taught her to pray, “Our Father who art in Heaven.”

YELLOW JESSAMINE WILD ORANGE & VIRGIN BOWER

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

II. The May Queen.

“God is love.”

On the first day of this delicious month—in which the woods of our beloved Carolina are radiant with flowers and redolent of sweets—on the May-day of my happy childhood—little children used to assemble in some shady nook, and celebrate the coronation of their chosen Queen of May.

Though to me the summer is past, and the grave autumn of life has crowned my brow with the “sere and yellow leaf,” yet, when I recall the innocent and joyous spring-time of my being, amid delicious shades, and blooming flowers, and singing birds, and murmuring rills, and gentle zephyrs’ soothing whispers, my buoyant spirit is young again, and laughs and gambols through the maze of flowers, mid bees and butterflies, in despite of the gravity of age. In this story, then, my dear young readers,

I shall tell you of our May parties, and of three of our most beautiful native wild flowers—the Virgin's Bower, the Yellow Jessamine, and the Wild Orange.

The Virgin's Bower is one of the most royal-looking of all Dame Flora's sylvan favorites—being a vine of most luxuriant growth, of massy rich green foliage, over whose whole outer surface are dense clusters of purple flowers, glowing and brightening in the sunbeams—appearing like a canopy of purple velvet above the throne of royalty.

It is supposed by some that when Sir Walter Raleigh first visited Carolina, being enchanted with the splendor of these native vines, he gave them the very appropriate name of “Virgin's Bower,” in honor of his royal mistress, Elizabeth, the virgin Queen of England.

Sir Walter Raleigh was a brave knight and accomplished courtier in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. He was also commander of a fleet of ships sent by that noble sovereign across the wide Atlantic Ocean, with directions to explore this continent, and see if it would be a good and comfortable home for her subjects.

Historians say he landed on the coast of North Carolina, and thence advanced sufficiently into the country to enable him to report satisfactorily to his royal mistress

on his return to England. His account being favorable, the Queen forthwith dispatched other ships laden with emigrants to occupy our beautiful land, and establish her dominion over it.

The Yellow Jessamine, or Golden Climber of Carolina, equally beautiful and luxuriant, often extends to the topmost boughs of the stately Pine; and there, as if jealous of the sunbeams, expands her massy, golden beauties to the skies, crowning the head of her proud supporter, and thus heightening its grandeur.

It is not unusual for these magnificent vines to twine themselves amid the luscious white blossoms of the Wild Orange tree, whose bridal wreaths are often laden too with the splendor of the Virgin's Bower, thus uniting the appropriate emblems of royalty—wealth, splendor, and purity or integrity.

The Wild Orange resembles, both in appearance and odor, the bearing Orange of the tropics. The white blossoms cluster thickly around a long, slender branch, which I have seen as long as my arm, studded from one end to the other with flowers, waving in the breeze and shedding their exquisite perfume.

In one of these natural bowers, we children held the court of our May Queen. We reared a mound of earth

within the bower, and covered it with moss, which became in time like a carpet of rich green velvet. It seemed a real pity to tread upon it, though it was prepared expressly for the feet of our chosen Queen; and from there she pronounced her coronation address, after having received a chaplet of flowers on her fair and beautiful brow.

It was our custom, a few days before the first of May, to assemble in the woods near our sylvan throne, and choose our Queen. What a sweet delight it is, at this distant hour, to reflect how lovingly, how innocently, and how joyously we performed our several parts! And here let me counsel you, dear children, if you would wish in maturer years to look back with unalloyed pleasure on the spring-time of your life, to love one another; for love will protect your tender minds from all unamiable feelings towards your playmates, and infinitely enhance your own happiness. Remember, it was love which brought your gentle Saviour from the bosom of his Father in Heaven, in order to gather such precious lambs as you into his heavenly fold.

There were always two candidates for the throne of May, and we conducted the election in this wise: One little girl sat on the grass, and suggested the flower to

represent each candidate; usually yellow and purple. Each voter then threw the flower which represented her favorite into the lap of the little girl on the grass, who proceeded to count them, while the rest stood around her in a circle, holding hands, with faces beaming with delight, and ready to dance round the chosen Queen as soon as her election was announced.

“The Queen is Purple!” or, “The Queen is Yellow!” soon greeted their anxious ears, and instantly a shout of joyful approbation arose from their innocent voices; the Queen was placed in the centre of the ring, the little girl on the grass took her place, and all danced round her, singing and laughing—every now and then kissing her pretty lips with guileless love, such as the angels know.

After this, our kind mammas went to work making cakes, and other nice things, besides loading us with fruits, nuts, and sugar-plums uncountable; and when the happy day arrived, helped us to arrange our table in the woods.

Our Queen had her maids of honor, her pages and high officers of state, among whom figured most conspicuously the almoner, who bore on her arm a basket wreathed with flowers, from under whose cunning beauties she from

time to time drew forth a liberal handful of sugar-plums, and, tossing them high in the air, was the first to scramble for their possession. In this she was followed by the whole assemblage, not excepting the Queen. This, perhaps you will say, was rather unqueenly; yet I can see no reason why she should have been excluded by such useless etiquette from the participation in every enjoyment of our jubilee. Indeed, the scramble was regarded as the choice pleasure of the occasion, and was accompanied with merry peals of laughter, while every face glowed with innocent delight and good-nature. These joyous occasions were never marred by the presence of the deformed visages of discontent, ill-humor, or fretfulness.

In the May party I now recall to remembrance, a beautiful little girl, called Annie L—, was chosen for our Queen. She came dancing into the ring we had formed for her, her blue eyes sparkling, and her bright, intelligent countenance glowing with pure delight. She had lovely golden hair, falling in rich curls around her fair shoulders, which were always tempting one to kiss them. We all loved sweet Annie L—, and no one dreamed of supplanting her. It was one of our chief pleasures to caress the sweet child, whose little heart was so guileless and so lovely, even as her face was beautiful. “Of

such,” said the blessed Redeemer, “is the kingdom of Heaven.”

Clad in a pure white robe, with her chaplet of white flowers shading a countenance of exquisite loveliness and sweetness, with a glow of health and delight illumining her beauty, she was the express picture of an angel. And Annie was not only a beautiful but a good little girl, obedient to her parents, and always amiable to her dear little playmates.

We conducted our Queen to her throne, singing and strewing flowers before her, and here is our May Song.

Oh, come, let us strew with sweet flowersThe path of dear Annie our Queen,To her throne in these beauteous bowersAwaiting her, fragrant and green.The morning shines brightly; oh, come, let us lead herTo grace with her beauty their shade,And on her fair brow place the chaplet decreed her,Then hail as our Queen the dear maid.Oh, strew there bright buds of the morning,Sweet emblems of beauty and youth,Of every fair virtue adorningHer young heart of goodness and truth.Through life may her pathway be brightened with roses,As this for her feet we now strew;May morn bring her rapture—and eve as it closesBring peace, in the light falling dew.Little Annie L— grew up a charming and excellent woman, enjoying the esteem and blessing of all who knew her, even as she had been good and lovely in her childhood, possessing the love and admiration of her little playmates. Sweet, lovely Annie L—! she was a child of God—and “God is Love.”

III. The Cup of Cold Water.For whosoever shall give you a cup of water to drink in my name....he shall not lose his reward.—Mark ix. 41.

On a certain bright morning, while the Honeysuckles, Lupines, Wild Pinks, and Roses literally carpeted the forests of our dear Carolina, three little boys set out on a ramble in these flowery wilds—on the borders of the winding Trent. Their fishing-tackle was not forgotten, as they knew that the river abounded in robins and silver perch and others of the finny tribe, meat for their mother's frying-pan, and an acceptable offering to maternal care. Each little boy carried a small tin bucket, within which was his dinner, and which on his return home would contain a goodly number of Honeysuckle apples or strawberries, or at all events a bright nosegay of wild flowers for his mother or sister.

The names of these boys were Tommy Fearless, Sammy Careless, and Harry Heartless. Of course my readers will readily perceive, from the diversity of their names, that

they were not all the children of the same parents. However, they were next-door neighbors. The father of Tommy Fearless was a carpenter, that of Sammy Careless a shoemaker, and of Harry Heartless a day-laborer—all from the humbler walks of life.

Only one of these boys attended Sunday School, and this was Tommy Fearless, being ten years old at this time. Sammy and Harry were a year or two older than Tommy, having advanced thus far in the journey of life without the soul-nurturing care of a Christian mother, or even the occasional teaching of a Sunday School, though this great privilege had been repeatedly offered to them. Their parents were thoughtless, ungodly people, totally unmindful of their responsible office, as representatives of the great Parent and Governor of all, to guide their offspring in the path of duty. Having stated these melancholy facts, you will at a glance perceive what kind of boys these were; particularly as I have no doubt you all are acquainted with the worlds of the blessed Saviour, who said: “A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit!” and, “Men do not gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles.” Therefore rejoice, and be thankful, you who have Christian parents, or faithful teachers.

Well, these three boys had enjoyed their day's ramble—had angled in the river, had filled their buckets with Honeysuckle apples* and other products of the woods, and had turned their faces homeward; when suddenly they heard piercing groans, and at intervals shrieks of agony, mingled with the blithe notes of the never-silent mocking-bird. Our little travellers paused and looked at each other in consternation.

“Oh, what can that be?” said Tommy.

“What can it be?” responded Sammy.

“We must search and find the sufferer,” said Tommy; “perhaps we may give some relief.”

“I can tell you,” answered Harry; “the groans come from a poor sailor in yonder cabin. Do you not see it just beneath that large oak tree?”

“Oh, yes, we see it,” said the other boys; “but who is this sailor?”

“He is a man,” replied Harry, “who was brought from on board a vessel from the West Indies; and he has that dreadful disease, the small-pox. He is placed here to be attended to till he either dies or recovers; for if he were

* Sweet, juicy excrescences on the branches of the Honeysuckle, very cool and grateful to the taste.suffered to remain in town, a great many persons might take the disease and die. Let us run away as fast as we can, boys, or we shall have the small-pox, too.”

“Oh, how dreadfully he moans!” said Tommy.

“Poor fellow!” said Sammy, though he began to move off after Harry, who only paused a moment till the others should follow him.

“Let us go to the poor man,” said Tommy, who stood still, as if thinking if it were right to leave the sufferer without seeing that he could render him any assistance.

“Come along, boys,” urged Harry, “or we too shall take this terrible disease, and be left out here in the woods to die.”

“Let us run as fast as we can,” said Sammy; yet Tommy stood still.

“You had better come along after us,” said the two boys, “for if you get this disease, even your father and mother will not be permitted to nurse you, or even visit you, and you will surely die out here in these woods.”

“Oh, come along, come along,” urged both the boys. All this while the piteous cries continued, and the boys were near enough to hear the words which issued from the sufferer.

“Oh,” said the voice, “for one drop of cool water on this burning tongue! I shall burn up with thirst. Is there no one who, for the love of Christ, will give me one drop of cold water before I die.”

The boys listened and turned pale with horror, if not with compassion.

“I cannot go on, boys,” said Tommy Fearless; “if you are afraid, go on; I shall give this man a cup of cold water before I leave the woods; and I am sure if you had been to the Sunday School, and heard and read what I have, you could not find it in your hearts to run away from the cries of this sufferer.”

“What was it you heard?” asked the other boys, whom the earnestly compassionate countenance of Tommy had compelled to pause in their heartless flight.

“My last Sunday's Bible lesson,” continued Tommy, “contained words which will be addressed to the wicked at the great day of judgment by our Redeemer and Judge—‘I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink; I was sick, and ye visited me not’—‘Verily I say unto you, inasmuch as ye did it not unto one of the least of my brethren, ye did it not unto me.’ And there is another place where He said, ‘Whosoever shall give a cup of cold water to a disciple, to drink in my name, verily I say unto

you, he shall not lose his reward.’ I cannot deprive myself of this promised blessing, or incur the condemnation of the wicked; so I shall go to the relief of the sick man, and you can go home if you choose.” So Tommy Fearless turned resolutely towards the hut, while Harry Heartless led off Tommy Careless, laughing, and taunting Tommy as they ran.

“Now,” thought Tommy, “they say this is a very terrible and dangerous disease—I may take it and give it to my parents, and brothers and sisters, and if they die, I shall be the cause of their death. If I die myself, that is nothing, because the Good Shepherd will take me into His heavenly fold, when I obey His voice. But ought I endanger others—what ought I to do?” And now Tommy remembered that his good Sunday School teacher had told him always to pray when he needed guidance, and that God would hear him, and direct his steps aright. So Tommy kneeled down, and prayed the Good Shepherd to guide him in this hour of peril and doubt. All the while the little boy was communing with his Saviour, the shrieks of the suffering sailor were piercing his ears and heart. Tommy rose from his knees convinced that he ought to disregard his own safety, and obey the injunctions of his divine Saviour. He was walking firmly towards the

hut, when, the door being wide open, the sailor saw him approaching.

“Little boy,” he cried out, “stop! stop! where you are, and listen to me. I would not, for the world, endanger your precious life for my own relief; therefore listen, and I will tell you how you can give me all I require without danger to yourself. And may God bless and reward you for your compassion and bravery. Take your tin bucket; go to yonder rill; fill it with water; then walk in carefully, touching nothing as you come. I will hold out my mug, and do you pour the water in, and return to the woods as speedily as possible, and rub the soles of your shoes well into the fresh earth before going home. After this there is no danger, and surely you shall not lose your reward in time and eternity, my brave little boy.”

Trusting in his divine Redeemer, Tommy followed the careful directions of the sick man, and relieved his burning thirst amid the outpourings of his grateful heart, and the comfortable assurance of his Master's favor. The face of the sailor was hideous from the disease; quite enough to frighten a less pious and brave boy from a benevolent purpose; but with such motives, and under such guidance, the little Christian is as brave as a lion. So Tommy's

courage did not fail, and his heart was filled with holy joy.

The sick man informed Tommy that he was placed there by the authorities of the town, under the charge of a nurse, who had cruelly left him all day alone, and might not return at all; for he was a man fond of drink, and such are not to be depended upon.

“I will go home and ask my mother to let me return and take care of you through the night,” said Tommy. But the sailor assured him there would be no necessity for this exposure of himself to the fell disease, as it was near the hour for the usual visit of the attending physician, who would provide him another nurse immediately.

“So now,” added the sick man, “give me another draught of water, and a few of those cool Honeysuckle apples, of which I am very fond; then hasten home, lest your parents should be apprehensive of your danger; and remember, that he who gives a cup of cold water to a disciple of the blessed Jesus will surely not lose his reward.” So, with the blessing of the sick sailor, Tommy departed, taking care to follow all his directions for his safety.

Perhaps my young readers may suppose that Tommy kept this adventure from his parents; but not so: his

Sunday School teacher had instructed him to submit his conduct entirely to his parents’ judgment, and never for one moment to deceive them. For although, through their ignorance of the precepts of Christianity, they may not understand or appreciate such motives, they will excuse the action in consideration of the child's confidence and truth towards them. Besides, Tommy knew he was following the commands of his divine Master and Redeemer, who could direct the unruly wills of all sinful men.

As Tommy approached his father's house, he saw one of his little sisters standing before the door, and as soon as she perceived him, she ran in, crying, “Oh, go away! go away, Tommy! you will kill us all—Oh, go away!”

But Tommy stopped, and waving his hand to her, said, “Tell my mother to come to the door, if she pleases.”

His mother immediately made her appearance at the door, pale with affright.

“Mother,” said Tommy, “the boys have told you where I have been; do not be alarmed, mother, I have not touched the man, though I have seen him, and given him water.” So Tommy told his mother how carefully the sick man had instructed him to avoid the dreadful disease, and how cruelly the other boys had run away and left him.

Now Tommy's mother, though not a religious woman, was sensible as well as reasonable, and did not severely reprove her little son, though she could not refrain from expressing her disapprobation and fears; and when Tommy explained his motives and good Christian feelings, she not only did not condemn him, but seemed deeply moved at the sufferings of the sailor, and the truly Christian conduct of her little son.

Although matters proceeded thus far so smoothly with our little hero, there was yet a severe trial awaiting him. His father came home from his workshop that night out of humor, and being a stern as well as an impulsive man, without the grace of Christianity to control his actions, would not listen to his little son's account of himself, but yielded to his angry feelings, and gave the boy a severe chastising. Tommy endured his punishment meekly, nor did he allow any feeling of resentment to take its place in his dutiful heart, but was willing to suffer for well-doing rather than to disregard the injunctions of our Saviour, who had given His life for our salvation. These heavenly seeds had been sown in his infantile heart by the Spirit of grace, through the diligent instructions of his good Sunday School teacher.

All the neighbors, including the Careless and the

Heartless families, for some time shunned the company of Tommy Fearless, but in due time he was looked upon, as all such good boys should be, as a Christian hero. Harry and Sammy, it is true, did not confess it, but it was nevertheless very plainly to be seen that they were both ashamed of their cowardice and unkindness. There is, doubtless, great allowance to be made for the alarm under which they acted, without the possession of Christian knowledge, such as had guided their little companion on the late occasion; yet the utter absence of feeling they displayed, and selfishness, with the ridicule which they poured upon Tommy, evinced a heartlessness and carelessness of disposition at variance with the feelings of common humanity. May the good Spirit guide some faithful Sunday School teacher to the desolate homes of these boys, and draw them into the fold of peace and of heavenly knowledge, which will make them wise unto salvation.

Years passed on, and Tommy Fearless grew up to man's estate. His father died and left his mother with a large family and small means. Consequently, it became the duty of Tommy, as her eldest son, to devote his earnings to her support. This he did cheerfully, like an affectionate and dutiful son; for obedience and devotion to the great heavenly Parent will naturally lead to the same

pious course towards the earthly parent, to whose nurturing care God has confided His children. “Honor thy father and mother,” is the commandment to which our Maker has vouchsafed a promise.

Still, Tommy Fearless was not without trial to strengthen his faith in the blessing of Divine Providence. There was an attachment existing between himself and a certain pretty girl in the town, by the name of Mary Gray—yet, from his obligations to his mother and her young family, there was little prospect of a speedy arrival at the consummation of his earthly happiness—a union with Mary. This was a grievous trial, which the young man bore like the same youthful hero we have seen him before, upheld by faith and love.

On a certain bright morning, the first of May, when our beautiful woods are thronged with admirers of nature's loveliness, the holiday was seized by all the laboring classes as one of the few allowable to them throughout the year. Tommy Fearless with his pretty Mary were among the votaries of the Queen of Flowers.

Our hero had sauntered on by the side of Mary, wreathing her hair with flowers, and plucking another and another for her hand, of every hue—which she continually

pointed out and admired—till suddenly he found they were before the cabin in which he had some ten years before relieved the thirst of the suffering sailor.

He paused and directed the observation of his companion to the tottering ruin—and seating her on a log, and himself beside her, he recounted the adventure. Wholly absorbed with their own affairs, the lovers did not perceive a third person near them, till, on hearing a crackling of the leaves under foot, they looked up and espied an old man approaching them.

“Young man,” said the stranger, “while resting after my long walk, on yonder log, I accidentally heard your little story of the sick sailor and yonder hut. Can you tell me what became of that sailor?”

“Indeed I do not know, sir,” answered the young man; “I was quite a little boy at the time, and I do not remember what became of him, beyond the fact that he recovered and left in the same vessel that brought him here.”

The old man then touched his hat and moved away, while the two young people soon forgot that an old man of so ordinary appearance had ever accosted them.

On the following morning, just as Tommy Fearless was preparing to resume his labors, still trusting in the goodness of Divine Providence, and nothing doubting that in

His own good time his industry and faithfulness would be rewarded by the completion of his heart's desire—a union with his beloved Mary, a note was put in his hand. He broke the seal, and read these words:

“Whosoever shall give to drink unto one of these little ones, a cup of cold water only, in the name of a disciple, verily I say unto you, he shall in no wise lose his reward.”

A check on the State Bank for ten thousand dollars accompanied this note, and the blessing of the sick sailor of the log cabin.

Tommy Fearless was thus enabled to marry his beloved Mary, and the two were as happy as they deserved to be by their diligence and good conduct, governed by Christian faith and love.

MAGNOLIA & VIOLET

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

IV. The Magnolia and the Violet.

The rich and the poor meet together; the Lord is the Maker of them all.—Proverbs xxii. 2.

When I was a little girl, I attended a school in which the high and the low, the rich and the poor, met together, without distinction, save that of merit. Yet there were in this school some pupils who looked with envy or contempt on many of their companions.

There was a beautiful little girl, from the highest grade of society, with bright blue eyes, sunny curls, and features of faultless moulding. Her countenance beamed with innocence, benevolence, and good nature. Charity, like a gentle dove, nestled in her guileless breast. She was the admiration of the whole school, though a few naughty girls envied, and pretended to dislike her

We will call her Magnolia.

And then, in the lowest grade of little girls, there was one, quiet, modest, amiable, and lovely, who soon won the

regard of most of her schoolmates, notwithstanding her plain clothes and humble origin.

We will call her Violet.

As might be supposed, these two little magnets soon attracted each other, and became firmly attached, though occupying such extremes in society. They were in the same class, sat on the same bench, and their loving arms were ever around each other.

There was another little girl, in the same grade with Magnolia, who was very much annoyed at the union of these two little friends. Sometimes she would thrust herself between Violet and her classmate, and endeavor to supplant her in Magnolia's affections; and she has even gone so far as to threaten Magnolia, to tell her mamma of the low company she kept.

One morning, when the roll was called, at Violet's name there was no response. Magnolia quickly perceived the pause, and with glistening eyes she watched the door, with the hope of soon seeing the tardy one enter. But, alas! she was several times reproved for looking off her book, and then for crying.

“What are you crying for, Magnolia?” asked the teacher.

“Because, ma'am,” she replied, “I am sure Violet is ill, or she would not stay away from school.”

“Well, my dear,” said the teacher, “suppose she is, it will do her no good if you spend the morning in crying. It will be far wiser to mind your lessons, and when you return home at noon send and inquire after your little friend. Now wipe your eyes, and come and say your lesson.”

Magnolia did as she was bid; but in spite of her efforts, the tears would trickle down her cheek. She wiped them off quickly, for fear of offending her teacher, who liked to be obeyed by her little pupils in everything

“Do, Annie, just look at Magnolia,” said the jealous and proud little girl I have mentioned before, addressing the little girl who sat next her; “do look at that silly child, crying for a poor creature like Violet. I dare say she has no frock to come to school in, and is now making dirt cakes at home, and not caring one pin for her lady-friend who is shedding so many tears on her account. I am sure if I were Magnolia's mamma, I should wish Violet dead, to rid my child of such a poor, mean companion. Would not you, Annie?”

“No,” said Annie, “for my mamma says it is a sin to wish any one dead; and besides, I like Violet—she is a good little girl, and a pretty one, if she is poor. I do not wish her dead.”

“At any rate, I do,” said the proud and now cruel girl; for pride and jealousy are very apt to make little girls think and say cruel things of their playmates.

Magnolia hastened home at noon, and acquainted her mother with her fears for her friend. So after dinner this good lady, with her little daughter, visited Violet in her humble home.

Although rich and elevated, Magnolia's mamma was of a meek and humble spirit, and ever strove, both by precept and example, to impress her children with the truth that the poor, alike with the rich, are the creatures of a kind Providence, equally beloved and cared for; and, moreover, that the Divine Redeemer of mankind had, in an especial manner, sanctified that lowly station, by being born in its midst.

So came this good girl to disregard station in choosing her favorite friend.

Magnolia and her mamma found Violet indeed very ill; so ill as to be wholly unconscious of the presence of her friend.

Magnolia's mamma sent at once for a physician, and supplied abundant means to render the little sufferer as comfortable as possible, and to gratify every wish she might express.

Every day these benevolent visits were paid. Violet's pillow was smoothed, and her every pain soothed by the endearing attentions of her little friend. The oranges were more delicious, the lemonade more refreshing, because these delicacies were held to her fevered lips by the gentle hand of her beloved playmate.

And then, when Violet was pronounced convalescent—when the burning fever, the racking pains, the appalling delirium, were past—how delightful to little Violet were the silvery tones of her friend's voice, as she sang her restlessness into calm repose!

How pure, how heavenly was the joy of Magnolia, while thus attending the suffering couch of her humble friend! Children! beloved of the meek and lowly Jesus, go you and do likewise! Magnolia had been taught that her gentle Saviour loved young children that tried to please Him.

It chanced the next Saturday, that the proud little girl who was so jealous of Violet, came to spend the holiday with me; so we re-arranged the doll-house, dressed all the dolls, gave them a handsome entertainment of fruits, sweetmeats, nuts, and cakes, which we very obligingly ate for them, as they could not do this for themselves

Several times in the course of our feast, my little companion

spoke fretfully, unkindly, and scornfully of Magnolia, on account of her low propensities, as she called her intimacy with Violet, particularly since her frequent visits at her friend's lowly home. Nay, she again expressed the unchristian wish that Violet might die, because Magnolia loved her.

The closet in which our doll-house was arranged, opened into the chamber of my mother, and she overheard our whole conversation. After dinner my mother mentioned Violet, and asked my little visitor if she was not grieved to hear of her extreme illness.

“No, indeed, ma'am,” answered my little playmate, “I never trouble myself with such low people; and I am sure my mamma would be very angry if I were to put my foot within such a dirty hovel as Violet lives in.”

“Yet, like all good-hearted little girls,” insisted my mother, “I should think you would be sorry for your playmate.”

“She is no playmate of mine, and I am not at all sorry for her, for mamma says such people are always pretending to be sick; and besides, they are accustomed to it, and do not feel it as we do.”

“I think, my dear,” replied my mother, “there is somewhat of a contradiction in what you say; how do they get

accustomed to sickness, if they are only ‘always pretending?’ and I should be obliged to you to inform me by what means your mamma discovers that the poor pretend to sickness. Does she visit them, and witness their duplicity?”

“No, indeed!” she replied, “mamma would not for the world be seen in such a place, or allow me, either. She despises such mean, dirty people.”

“I am sure, my dear little girl,” my mother replied, “you must do your mamma injustice, and besides, I must beg you never to express such ideas and feelings in the hearing of my children. I assure you, they are not accustomed to think or feel so uncharitably. I was very sorry to hear you say, this morning in the doll-house, that you wished little Violet might die, because she was so low and mean, and Magnolia loved her.”

My playmate really did blush at this; and when my mother saw the color mount to her face, she added kindly—

“I am glad you are ashamed of it, my dear little girl, and I hope it was said thoughtlessly. You cannot have meant what you said.”

My playmate turned on her heel, and with a proud toss of her head, shaking back her curls, she stepped out

on the piazza and danced, as if utterly regardless of my mother's admonitions (though I really think it was all thoughtlessness). In the cool of the evening, my mother invited us to take a walk with her in the woods. We, and all the children, were delighted with this proposition, and with hearts and eyes dancing with joy, were soon in the midst of the “Wilderness of Sweets,” as our favorite woods were called. My mother, who always took pleasure in joining in our childish sports, assisted us in gathering flowers and twining wreaths for our hair, and at length paused beneath a superb Magnolia tree, which was then in full bloom.

Nature decreed it no easy task for such rash little hands as ours to pluck flowers from this queenly tree. We could only admire their regal splendor, which we did by clapping our hands with ecstacy, while the little birds sang with our merry hearts from out the bright, green, glossy leaves of the glorious Magnolia.

My little sister Sue did not seem to admire the Magnolia flowers as we did, or enjoy their luscious perfume, but busied herself gathering Violets from the borders of a little rill that rippled over its roots, and then ran noiselessly away among the lowly grass. “See here! mamma,” cried she, after we had all seated ourselves on a

mossy bank, near the Magnolia tree; “see what a handful of Violets I have gathered! I love them far better, and think them far sweeter, than the Magnolia, though they cannot be seen as far, and may not be as splendid.”

“They are indeed very sweet, my dear, and pretty, modest, little flowers,” replied my mother, “and lovely emblems of modest, lowly worth, not to be despised by good children who know that humility is approved, while pride is condemned, by the great Father of all. You all know, my dear children,” continued my mother, “who has created all these beautiful flowers, and scattered them around our dwellings, to fill our hearts with joy and gladness?”

“Oh, yes!” cried every one, “it is God who is so good.”

“And it is God, too,” said little Sue, “who made the birds, that sing so sweetly.”

“Surely,” said my mother, “all our blessings and delights come from God. The same gracious hand which formed this splendid Magnolia, made these modest Violets beneath it, though they are meek and lowly, while the other is lofty and glorious in her apparel. The delicate perfume of the Violet is as grateful an incense to Heaven as the luscious breathings of the Magnolia. Each, in its way, exhibits the wonder-working hand of the great Creator. His care, His love, is over all the creatures He

has formed, however exalted, however lowly; and you must remember, dear children, there is no respect of persons with God.

“And now, my dear children, see how the flowers of the forest can teach you a lesson of love and charity! See how the Creator has endowed each with peculiar beauty; the humblest, as well as the most exalted! And so it is with the human family. The rich and elevated may possess the charms of gratitude to God, humility, compassion, benevolence and amiability; the poor may be patient, contented, diligent, and obedient to their Creator, under privations, sufferings, and neglect; and, above all, in Heaven they may shine with the angels, while those who scorned them here may desire to sit at their feet.

“Many children, whose parents are wealthy, imagine that it lessens their consequence to be seen with the poor and plainly clad; but they are vastly mistaken. It is only the company of the wicked that can really produce this humbling effect, in the eyes of the virtuous and good. Why should we dread the scorn of the wicked?”

All the children listened attentively to my mother, and all readily acquiesced in the sentiments she uttered; all, save my proud little friend, who hung down her head and remained silent. It was easy to be seen that her heart

was touched. My mother had struck the right chord in that heart, naturally of fine sensibilities, yet undeveloped by careful, generous training.

On Magnolia's next visit to her sick young friend, what was her astonishment to find by her side, and reading the Bible to her, that very little girl who had wished her dead!

Violet recovered, and returned to school, amid universal rejoicings and congratulations.

My proud little friend learned a valuable lesson of love and charity. She is no longer proud and haughty, but amiable, kind, and generous—a thousand times happier than she ever was in her whole life before.

Love one another, dear children, if you would be beloved and happy. Love one another, whether rich or poor, remembering your blessed Redeemer, while on earth, had not where to lay His head.

V. The Trumpet-Flower, or Gertrude and Alice.

Obedience is better than sacrifice.—1 Samuel xv. 22.

A lady, with her two little daughters, came from her Northern home to visit her brother, who had married a Southern heiress, and resided on a beautiful estate on the Roanoke.

Mrs. Livingston was an excellent as well as an accomplished woman; a love of flowers was, with her, almost a passion. The lavish profusion of spring flowers had ceased when she came, yet numbers that were beautiful brightened, in their order of succession, the fields, the woods, and meadows; many that the strange lady and her little daughters had never seen, except it be in a greenhouse.

At the breakfast table, the very first morning after their arrival, the theme of conversation was flowers, as it might be supposed; and the lady inquired eagerly which of the lovely handmaids of Flora were out in their court attire—in actual service of their Queen, at this time.

Lith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.THE TRUMPET FLOWER

Many were named and described, though none seemed so much to excite her admiration as the gorgeous Trumpet-Flower, which she expressed an anxious desire to see.

“Oh, mamma,” cried Gertrude, “let us children take a walk out in the woods, and get you these beautiful flowers. Cousin Charles will show us the way, will you not, Cousin Charles?” looking at a handsome, intelligent boy, who sat silently watching his two pretty little cousins, in their innocent delight.

“Yes, surely I will,” the little boy answered; “so let us set out as soon as breakfast is over. I know where there are a great many Trumpet-Flowers; the hedge around the orchard is covered with them.”

“Do you not remember, my son,” said Charles's father, “that I have told you the dew on the Trumpet-Flower is poisonous? It is too early; you had better defer your walk till your aunt and cousins are sufficiently rested after their long journey, and then we will take a delightful evening stroll to the orchard-hedge, and see it in all its glory, without danger. You would not, I know, like to see the hands and faces of your dear little cousins covered with dreadful sores, and swollen till not a trace of their beauty remained? I know you would not.”

“Not for the world, sir!” the little boy exclaimed, with

enthusiasm; “not for the world, papa. We will wait, children, till evening.”

Gertrude cast down her eyes, and looked the restless picture of discontent, while the gentle little Alice readily and sweetly acquiesced.

“Cousin Charles,” whispered Gertrude, as they left the breakfast-room, “let us steal out, and fetch mamma one of those beautiful flowers.”

“Oh, no!” cried Charles, astonished, “I could not do such a thing. Besides the danger to our hands and faces, we should be disobeying, to touch the flower while the dew is on it.”

“Your father did not tell you not to touch it,” said Gertrude, “he only said we had better not go till evening.”

“It is all the same,” replied Charles; “that was what father meant, and I cannot go, because it will be wicked.”

“Well, you are a disobliging boy,” said Gertrude, as she ran up the stairs to her mother's room.

In the evening, company came just as all were preparing for the proposed walk. Ladies called to see Mrs. Livingston, accompanied by their little daughters. So the children also were obliged to defer their walk.

By sunrise the next morning Gertrude and Alice were awakened from their slumbers by the little merry singing

birds, in the trees that surrounded their uncle's dwelling. And, indeed, one daring mocking-bird perched himself on a branch close to the window, over the children's bed, and seemed to be saying to the little slumberers, as he turned one eye and then the other towards them, with saucy inquisitiveness—“Get up! get up! get up! you drowsy ones! Come out and sing with me the praises of our Maker. Get up, ye thankless ones! it's time to rise and thank Him, for His care through the night, and the return of this bright morn, this sweet, invigorating air. Up with you, up with you, lazy ones!”

And sure enough, the children awoke, and, springing out of the bed, cried with delight—

“Oh, look, mamma! look at that sweet bird; he has come to wake us!” But, alas, as the children, in their ecstasy approached the window, birdie flew off to a higher branch, and looking down defiantly with one eye turned saucily at them, chirped—

“Catch me, if you can! I have waked you, and that is all I wanted. Now make haste, and join me in the woods.”

So the little girls dressed themselves as fast as they could, and, with mamma's permission, hastened after Cousin Charles and Cousin Helen, to walk on the river bank.

As the children were about to run down stairs, Mrs. Livingston called to them—

“Now remember, my dears, not to go near those Trumpet-Flowers, if they should chance to be in your way—remember.”

The eager Gertrude was on the last step when the latest “remember” was pronounced; still it reached her ear.

“I shall remember,” answered the calm and quiet Alice, with whom her mother's word was law.

“Oh, children,” cried the impulsive Gertrude, “look how beautifully yonder boat seems to fly over the water! I wish I were in it, it would be so delightful. Oh, Cousin Charles, how I will love you if you will only call the boatman to take us in!”

Now the boat was rowed by a black man belonging to his father's plantation, but Charles knew they had no permission to enter the boat, and feared to displease his father; so, after hesitating some time through diffidence and fear of offending his little cousins, he at last was brave enough to say—

“I am sorry, dear cousin, to refuse you, but I know papa would be displeased if we should enter the boat without permission.”

“And I am sure our mamma would be displeased, Gertrude,” said Alice.

“Oh, you never wish to do anything that pleases me,” said Gertrude, impatiently, “and so now I shall not mind either you or Charley.” With this she called as loud as she could to the boatman—“Come here, Mr. Boatman, that's a good fellow! we wish to take a row up and down this river. Pray come and take us!”

But the breeze was whispering something more agreeable as well as profitable in the boatman's ear, doubtless, for he continued his steady strokes with the oars, while showers of sparkling diamonds seemed to fall from them as they rose in the light of the rising sun.

“I am very glad the man does not hear you,” said Alice, “for, Gertrude, you know mamma gave you no permission to go on the river.”

“What of that?” answered Gertrude; “we did not ask her, and cannot tell whether or not she would have consented; I dare say she would, though.”

“It is much better as it is, Gertrude,” said Alice, “and so now let us be content to walk on this pretty shore, watch the boats on the river, and listen to the birds. Come, sister, you will fall in the water.”

But Gertrude heeded her not; she had taken another

fancy, and the next thing Alice saw, she was sitting on a log, pulling off her shoes and stockings.

“What are you going to do, Gertrude?” asked Alice in alarm. “For pity's sake, take care what you do.”

“I shall take care to have a nice time of it, wading in the water, and making the print of my feet in this beautiful white sand,” replied the little wilful child.

“Oh, Gertrude, Gertrude!” beseechingly cried Alice, “pray do not. Mamma will be so much displeased with you. And are you not ashamed to take off your shoes and stockings before Cousin Charles?”

At this Gertrude blushed, for in truth she was a modest child, though sometimes so much the slave of impulse as to forget who were looking on.

“Come, put them on again,” said Alice; “see what pretty flowers are yonder on the bank! and it will soon be time to return to breakfast.” But while she was speaking, the shoes and stockings were left on the log, and Gertrude was intently watching her little white feet as they left their print in the sand.

Alice, Charley, and Helen sat on the bank, in despair of persuading the wilful child, till she was tired of walking in the water. At last she came out, and, putting on her shoes and stockings, followed the other children in

their walk. It chanced that a Trumpet-Flower was blooming by the bank, and as soon as Gertrude espied it, she cried out in ecstasy—

“Oh, there is a Trumpet-Flower! I am sure it is exactly like a trumpet. Oh, how beautiful! how beautiful! I must have it for dear mamma!” and Gertrude darted forward to seize the flower.

“Oh, Gertrude!” exclaimed Alice, in consternation; “pray do not touch the flower; you heard what uncle said, and you remember what mamma said the very last moment before you left her this morning.”

“Well, I do remember what uncle said, and I do not believe it.”

“Not believe my father?” said Charles, coloring instantly.

“Oh, I do not mean that I do not believe uncle, but I mean that I cannot believe that anything so splendid can be poisonous. It must be a mistake—these flowers are too pretty to harm any one.”

“But mamma,” said Alice, “will you disobey mamma?”

“Oh, mamma will forget that she forbade me, when she sees one of these beautiful flowers. She will never think of being angry with me for plucking it.”

“Pray do not touch it,” said Charley, addressing the rash little girl.

“I must have it,” said Gertrude, and so she climbed up to the flower, and, although she saw it wet with the poisonous dew, she did not hesitate to pluck it, while her face and hands were sprinkled all over.

“So now I have you, Master Trumpet, in spite of those cowardly children, and mamma shall not be long without the pleasure of beholding you. Come along, sister, and see how happy I shall be when mamma gives me a kiss for my pretty offering. Will you not envy me?”

“I do not at all envy you, Gertrude,” said Alice; “and as for the kiss, I think you will be far more apt to receive some punishment for disobedience. But come, we shall soon see who is the happiest girl; though to tell you the truth, I shall not be very happy to see my sister in disgrace or pain, for she is in danger of both.”

“Nonsense, I have no fear of either,” said Gertrude.

Charles and Helen walked on quietly, not feeling themselves well enough acquainted with their little cousins to speak their minds fully. As soon as they all reached home, Gertrude flew up to her mother with joy dancing in her bright eyes, and exultingly cried—

“Oh, mamma! see what a beautiful flower I have brought you. Are you not glad?”

When her mother first beheld the flower, her countenance

brightened with delight, but the very next moment it grew sad, as the reflection of her little daughter's disobedience, and consequent danger, came to her mind.

“I am sorry my little daughter so soon forgot to obey her mother,” she said; and the pleasure she might have felt on seeing this splendid blossom was entirely destroyed. “I should feel it my duty to punish you, Gertrude, were it not that I know your fault will punish itself. Already I see signs of your self-inflicted chastisement—your face and hands are covered with spots.”

“Oh, mamma, I do not mind the spots, so you are pleased with your flower—it is so beautiful! Only forgive me, dear mamma, for forgetting your command, and I shall not care how sore my hands are—forgive me and kiss me—I plucked it for you—for I love you so dearly, mamma.”

Mrs. Livingston, though deeply touched by her little daughter's affectionate ardor, was nevertheless too much displeased with her to give her either a kiss or a smile, but taking her by the hand she led her to her chamber, where she bathed her face and hands with pure water, in the hope of removing the poison; but it was too late. Gertrude's face began to swell, and her beautiful large eyes were in a short time almost closed, and, at last, her

lovely features were hideous to behold. Her fingers became double their natural size, and the pain was intolerable. Poor girl, how bitterly did she repent of her rashness and disobedience when it was too late! This was her punishment.

Mrs. Livingston did not aggravate her sufferings by reproaches while she remained ill, but as soon as she recovered she said to her—

“Now, my dear little daughter, since you have experienced such painful effects from your waywardness and disobedience, I trust you will always remember that nothing can give your mother pleasure which is obtained through your wrong-doing. The implicit and sweet obedience of your sister Alice was far more acceptable to me than that splendid flower, which was obtained at such a fearful sacrifice to yourself. ‘Obedience is better than sacrifice;’ and more acceptable to your heavenly Father, as I assure you it is to me, whom God has placed over you, for the purpose of having His divine precepts inculcated upon your tender mind.”

This was a severe lesson for poor Gertrude, but it was one she never forgot, and from that time the ardor of her disposition was directed to a better and a happier, a more innocent and excellent way of pleasing her mother by

obedience, sweet obligingness, and diligence; for Gertrude was in truth a noble-hearted little girl, erring only from thoughtlessness, and a want of control over her will.

The Trumpet-Flower became to her like a talisman; the thought of it never failed to check any rising impulse to rashness or disobedience. Whenever she saw it, almost it seemed to sound into her ear, “Obedience is better than sacrifice.”

VI. The Triumph of Truth.

Lying lips are an abomination to the Lord; but they that deal truly are his delight.—Proverbs xii. 22.

Hugh Grenville was a boy worthy to be imitated by my young readers. From his infancy he was remarkable for truth and obedience to his parents—two most estimable traits, the very best foundation for “that noblest work of God, an honest man.”

Hugh was about ten years old, when, on a calm summer evening, his father took him, and his almost baby-brother, to walk on the borders of a creek that ran through a beautiful wood, near his dwelling. There was a lovely green meadow near the creek, too, bespangled with delicate White Lilies, and many other flowers, which attracted a multitude of butterflies, whose aerial motions gave life and cheerfulness to the scene.

Mr. Grenville was a wise as well as a good man, and

PASSION FLOWER & MEADOW LILYLith. of Sarony, Major and Knapp. 449 Braodway, N. Y.

seldom suffered an occasion to pass unimproved, for the benefit of his children's minds and hearts. After leading them along the creek, to admire its sparkling waters, as they rippled among the tufts of grass and over the projecting roots of the overhanging trees; to watch the little silver perch as they timidly stole along, in the shallow water, to catch the tiny minnows that sported there in multitudes; or listened to the tapping of the crimson-tufted woodpecker, or the carols of the mocking-bird, or the shrill cry of the kingfisher, as it darted upon the little hunter perch, that had just devoured a hapless minnow; he at length seated himself upon a mossy bank, beneath the trees, while his little boys amused themselves chasing butterflies and gathering flowers.

Little Eddie came bounding up to his father, almost out of breath from running, with innocent joy sparkling in his bright blue eyes. “Look, papa! look here,” cried he, “at these beautiful flowers! will not mamma love to see them in her pretty vases? Oh, I will take them to her.”

“Yes, my darling, take them to mamma—they are beautiful indeed; but first let me look at them for awhile,” said his father. “Hugh, come here, Hugh; you are old enough to learn a lesson from these lovely Lilies. See

how pure, how delicate their texture! how wonderfully beautiful! See, too, the bright golden stamens, in the midst of these petals of exquisite purity!”

“And now tell me, papa,” said Hugh, “what lesson you can draw from these pretty White Lilies? I am sure I have not sufficient wisdom to perceive in them anything but beauty and sweetness.”

“Think again, my son,” said Mr. Grenville; “you say you can perceive beauty and sweetness; and do not these delightful qualities suggest to you some religious thought?”

“Oh, yes! papa,” said Hugh; “I now remember you have often told me that every good and perfect gift was from God; and that these pretty flowers were made to gladden the hearts of His children.”

“Right, my son,” was his father's answer; “and yet another and more special lesson may be learned from this flower—the White Meadow Lily. See these delicate petals, so easily marred by a careless or rude hand! So it is, my son, with the innocent heart of a child; a wicked companion, or an unfaithful guide, may mar and deform that innocency in which its Maker formed it; and when once that heart is contaminated by evil, only the divine grace of Christ can wash out the stain, as nothing could

restore the perfection of the injured Lily but the hand of God.”

“And now, father,” said Hugh, “tell me what these golden stamens in the centre of the Lily teach.”

“The golden stamens,” said Mr. Grenville, “convey to the thoughtful mind a lesson of wisdom also. See how these pure and delicate petals surround, and are exalted above the golden stamens! So are purity of heart, innocency of life, and holy truth exalted above the treasures of this world.”

At this moment little Eddie came flying up to his father, and with childish haste thrust into his hand a purple flower, known as the emblem of the Crucifixion.

“Ah, my children,” said Mr. Grenville, with emotion, “here is the grandest, the most awful lesson, of all that is taught by the flowers of the field! This is the Passion-Flower. See here these pale green leaves, that form the outer circle around the flower—these we will suppose the timid disciples of our Lord! Then here are the three cruel nails which pierced His blessed hands and feet, and in their centre is the ponderous hammer which dealt the agonizing blows—and underneath these are the five mortal wounds endured by the great Redeemer! See the glory surrounding the whole, and the crown of thorns!

See the crimson spots sprinkled on the leaves, memorials of His blood-shedding! And here, at the base of the stem, is attached a tendril, representing the cruel cord with which the blessed shoulders of the Redeemer were lashed, and his beneficent hands confined—those hands so untiringly active in doing good to sinful, ungrateful man!”

Even little Eddie, struck by the unusual solemnity of his father's countenance, paused at his knee, and listened with awe-struck expression to the mournful lesson of the Passion-Flower. Tears glistened in his beautiful eyes for awhile, and then he darted off again, in chase of the butterflies that led him a merry dance among the myriad flowers that brightened and perfumed the meadows.

But Hugh, the contemplative Hugh, still looked intently at the Passion-Flower, as if deeply weighing its mournful significance.

“I hope I shall never forget what you and these beautiful flowers have taught me this day, dear father,” at length he said. “I hope the White Lily will always remind me of the holy beauty of purity, innocence, and truth; and I shall always look on the Passion-Flower with reverence, as nature's memorial of the Redeemer's sufferings and death.”

By this time Eddie had filled his apron with flowers

for his dear mamma, and Mr. Grenville, still conversing with Hugh, led the children home.

On the following morning Hugh was at school punctually, and there gained the approbation of his teacher for correct deportment and industry. This excited the jealousy of his classmates, I am sorry to say, and they determined by some means or other to bring disgrace upon him.

When school was over, these wicked boys proposed to Hugh to take a walk with them, before going home. This he was permitted to do by his kind parents, whose confidence in him was unbounded. So Hugh accompanied his classmates on their walk, and they soon arrived at the little stream in which the boys were accustomed to bathe, and sometimes angle for silver perch.

“Look here, boys!” shouted Harry Reckless, “look here! a boat! a boat! Let us take it, and go over the creek and get plums and berries; and besides, there are birds’ nests in abundance in yonder wood. Let us go, boys.”

“But,” suggested Hugh Grenville, “the boat is locked fast to this post, and we cannot take it.”

“Oh, we will soon manage that matter,” said Harry;

and with this he picked up a great stone and advanced towards the boat.

“Hold!” said Hugh, “you are going to break old Joe's lock, and you know, boys, he is a poor man, and a new lock will cost him a day's fishing; and besides, it is wrong to take his boat without leave.”

“Who cares for leave?” shouted Harry—and “Who cares for leave?” responded all the boys save Hugh. And so, with a few strokes of the great stone the lock gave way, and the boat was free. All the boys were soon in the boat except Hugh, who stood hesitating on the bank.

“Come along, Hugh!” shouted the boys. “Don't stand there, grieving over old Joe's lock; you did not break it, and we can bear the blame; so come along.”

“Yes, come along!” shouted Harry Reckless, “or we shall call you coward; or perhaps you are mean enough to tell upon us.”

“Yes!” shouted another, “he means to be a tell-tale. Well, go along, tell-tale, we will have our fun, blame or no blame, tell-tale or no tell-tale.”

But the brave and honest Hugh scarcely heard their taunts, so earnestly was he arguing with himself on the propriety or impropriety of accompanying the boys. At

last he concluded to go, with the hope that he might induce them to purchase a new lock for the poor old fisherman, and take his boat back safely to its mooring, instead of letting it drift away and be lost to its owner.

Hugh stepped into the boat, and then, amid shouts of triumph and merry peals of laughter, the party were soon in the woods on the opposite shore, enjoying a pleasant ramble in the refreshing shade, amid the perfume of innumerable flowers, and the melody of birds. During the ramble, Hugh several times surprised the boys holding a consultation, which on his appearance ceased, and mysterious glances passed among them. Still the innocent boy suspected no evil to himself, but continued to converse with frankness and good-humor.

On their return, just as they approached the landing, the conspiring boys began shaking and rocking the boat from side to side, till at last it was upset, and all were thrown into the water. After they had scrambled out, Harry Reckless exclaimed, “It was you, Hugh, that upset the boat, while we were off our guard. Now you will get a good whipping, and that is a consolation.”

“I?” said Hugh, with astonishment; “why, Harry, I did not move of myself while I was in the boat. Are you not ashamed?”

“That makes no difference, Mr. Demure; we all intend to say you did it, on purpose to make us sick. We are too many for you this time. We shall be believed, and you will have the rod upon your fool's back. Ha! ha! ha!”

“So be it, boys,” said Hugh, “yet I shall tell the truth.”

“That will do you no good, as we are five against one. We shall be believed. There is no fear, boys,” said Harry.

“But what you say will be a falsehood,” returned Hugh.

“Who cares for that?” shouted this wicked boy; and “Who cares for that?” echoed all the rest, “so you get the whipping, and we escape it.”

“Do not be so sure of that,” said Hugh, calmly, “for I have never told an untruth in my life, and my father will never believe you till he himself detects me in a lie—and a lie I hope never to tell while I live. And how about the broken lock?” asked Hugh, addressing Harry.

“Of course you broke it,” said the false and daring boy.

Still calmly Hugh looked this bad boy in the face, and said, “Harry, if I were you, I should fear the thunders of heaven would strike me dead! And as to the punishment you threaten me for your offences, I would much rather

bear it for truth than for falsehood. I shall tell the truth, and be far happier with my whipping, than you will be with your guilt—though the whipping I shall never feel, if my father is to give it to me. He is too just, and knows me too well.”

“Then we will whip you ourselves,” said Harry Reckless, “will we not, boys?”

“Yes! yes!” shouted all, save one. This was Willie Kindheart, who, though accidentally thrown among bad companions, was really better disposed than they.

“I should be sorry, boys,” said Willie, “to see Hugh beaten for nothing. I cannot join you any longer. I am ashamed of what I have done.”

On the following morning Mr. Grenville was waited on by the fathers of these wicked boys, with a demand that Hugh should be punished for upsetting his playmates in the creek, and endangering their lives.

“My dear sirs,” answered Mr. Grenville, “immediately on Hugh's return home, yesterday evening, he came and told me the whole affair; and I know his account is true, for this one reason—he has never told me an untruth in his life; and if you can all declare the same of your boys, then I will take the pains to inquire into the guilt or innocence of my son. If you cannot conscientiously place them

on the same footing as Hugh, in this respect, I must of course decline whipping him, or even making further inquiry into the matter.”