| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

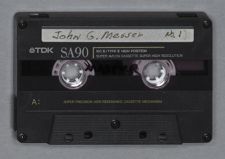

| Capt. John G. Messer, US Navy (Ret.) | |

| USNA Class of l941 | |

| February 5, l994 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, begin with your background.

John G. Messer:

I was born in a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts, on the tenth of April, l9l8. I went to public schools and then I had a marvelous opportunity to go to a private school that was called Roxbury Latin School. There's a Latin School in Boston, but that was public, my school was private. It was founded in l640 before Harvard, free to the boys that lived in Roxbury. It was a six-year course. I went through sixth grade [in public school] and then went to Roxbury and stayed there for six years. I had very private instruction, about a twenty to twenty-two [kids per] class each year.

Donald R. Lennon:

How was this financed?

John G. Messer:

By the time I went in, it was built up pretty much of endowments from the alumni. I don't know. I think it was only something like one hundred dollars. I know the Naval Academy was a hundred dollars, but Roxbury was practically nothing. I walked to school. Any smarts I have, I attribute to that school. It is still going today and it's grown probably three times as big, and it's non-discriminatory. It is all boys. There are no girls. You have to wear a coat and tie to school every day.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are there still small classes?

John G. Messer:

I imagine they're bigger now, because they probably have more subjects and the school has expanded.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did your father do?

John G. Messer:

My father was a dentist. Are you really interested in details about my parents?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

John G. Messer:

My father was a very kind gentleman. His dentist office was a five minute walk from home and he worked there seven days a week. He worked all day and came home for dinner, then went back after dinner. Men who were working couldn't get there any other time for an hour, so he went in, including Saturday. He also went in on Sunday mornings, not to make money, because we're talking about the Depression, but he was just that type of person. I hope I have a little of that myself.

I remember at one time during those days, he had about twelve thousand dollars in debts out. My mother tried to get permission to start contacting these people and he wouldn't do it. He was just that kind of person.

Donald R. Lennon:

A different world entirely than today. It really was. So, you attended this school for six years.

John G. Messer:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

At what point did you begin to think of the Naval Academy as a possible choice?

John G. Messer:

I graduated from Roxbury Latin in l936. I did good on my college boards and was accepted at Dartmouth College. I went to Dartmouth, had my room picked out and everything, and the Depression was so bad that I didn't see how my father could afford to send me there. There had been two boys in the class ahead of me at Roxbury Latin School

that had gone to the Naval Academy, so I told my Dad, "If you'll spend the money for one year at a prep school, I'll try to get into the Naval Academy."

This one year in prep school was primarily to get an appointment because the honorable somebody Tinkham from Boston gave a competitive exam for the appointment. He didn't just hand it out politically.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's unusual for appointments.

John G. Messer:

That's what he did, so I went to this prep school named Randalls School. Jerry Ball was there, Bob Long, and Ed Hines, too. At Randalls, as probably others have told you, they drilled us. The government put out an exam for the congressmen. They used five hundred questions and they selected out of that five hundred, I don't know, eighty or a hundred. So, we just went over those five hundred questions week after week, month after month, and when it came to taking the exam, it was like writing your name.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was kind of a boring year, wasn't it?

John G. Messer:

Well, it was except this Randalls who ran the school had been in the Army and he was tough. We had an honor code and if you got caught talking after hours or anything, you had to report yourself.

Donald R. Lennon:

A lot of good discipline.

John G. Messer:

Yes. It was very worthwhile. We finished up in April, I think. Then, he ran an advanced course to help you with the first year in the Naval Academy, but I had enough by then. I didn't take that.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, you completed this year before you took the competitive exam in Massachusetts?

John G. Messer:

That would have been in March or so. I also joined the White Hat and Naval Reserve. That was another way of getting in. There were so many appointments. How well you did on the entrance exam determined your appointment. I got in through the Reserves as well as through the congressman; so I went in through the Reserves and let another kid at home use the appointment from the congressman. I didn't really know much about the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Living right there in Boston, that's purely maritime.

John G. Messer:

Well, I had an uncle that was a lieutenant colonel in the Army, in Army finance, and he was all for me to go to West Point. I think they had just put that movie out "All Quiet on the Western Front," with trenches and rain and mud and everything and that didn't appeal to me at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Capt. Ball mentioned a movie that had come out about that same time with Dick Powell, "Ships Ahoy," or something like that, that gave a different view of the Navy, that influenced him.

John G. Messer:

I don't remember that one very well. Anyway, I went in with the rest of them. You know, they all go in at the same time now, whereas we went in little by little. I think I was fortunate that I wasn't called up until late July or August because by then they had turned down so many on this eye thing that when I came they said to come back for a re-exam. I called this ophthalmologist and he told me to sit on the seawall in Annapolis for three days and look out as far as I could, not to read any newspapers, and when I went to a restaurant, get someone to read the menu to me�“not” to use my eyes at all!

Donald R. Lennon:

Except for distance vision.

John G. Messer:

I don't know whether it was that. They had been turning down so many that they were afraid they weren't going to fill up their quota.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting.

John G. Messer:

Anyway, once I got in, I didn't have any problem. I could read the chart, 20/20, no problem.

Donald R. Lennon:

Having had a year at Randalls, you knew what to expect as far as Academy discipline was concerned.

John G. Messer:

That was part of his training as well as to get you acclimated to pretty strict conditions.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about after you got in? How did things go for you academically?

John G. Messer:

I did pretty well. I think probably the first couple years, I didn't do too well because I was trying to learn everything in the book rather than taking out the important things. You've probably heard from many others that we didn't have too many real professors there. We had a lot of lieutenant Naval officers teaching and they just handed out slips of paper.

Donald R. Lennon:

A matter of testing, right?

John G. Messer:

They gave you a question, you went to the blackboard and answered it. The last two years, I apparently relaxed and learned how to study, and I think I ended up either seventy-two or eighty-two in the class. I was in the top fifth, I think.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about outside activities, sports, or other extra-curricular activities?

John G. Messer:

Well, since Roxbury was a private school, of course it was small, and I was practically in all the sports. I was captain of the football team, baseball, track, hockey, tennis, and golf. I did them all. Then that year off, I wasn't really into sports at Randalls. We didn't have any time for sports. Then when I came to the Naval Academy, I went out for

football, but I only lasted about two days. I realized that I didn't have the strength or the physique.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about sailing? It was the perfect place for spending a lot of time sailing.

John G. Messer:

Yes, I did some sailing, because we all had to do some sailing.

Donald R. Lennon:

Recreational sailing up and down the Chesapeake.

John G. Messer:

We had a boat club and I joined that. We had these fifty-foot motor launches that had been made into ketches--two-masted, a forward cabin, and an after cabin. That was one way of getting away from the Academy on weekends. They let you off after noon on Saturday and you had to be back by supper time, Sunday night. That was a lot of fun.

Donald R. Lennon:

I remember someone, one time, told me about getting caught in a rain storm and being marooned on an island on the Chesapeake, and they had a problem getting back.

John G. Messer:

We had some of those. We were in a marina up the Chesapeake and we went to start the engine and the starter broke. We had to get someone to tow us out into the Chesapeake. There wasn't much wind, but that was the only way we had to get back. We were late, but we did have a radio so we could contact the Coast Guard to tell the Naval Academy we were all right, that we were just having a tough time getting back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular characters or individuals that you remember? I know that some of your classmates have talked about Uncle Beanie. Any particular incidents?

John G. Messer:

Yes, Uncle Beanie Jarrett.

Well, there was one thing along those lines. There had been a hop--a dance-- scheduled for one weekend. Girls were coming and then Swanson, Secretary of the Navy, died and they canceled the hop. So, a group of us decided we'd take the girls out over night on one of those ketches. We got one of the house mothers--you know there were houses

around Annapolis with ladies for the drags to stay--and we got one of them who was willing to come on board as a chaperon. We had separate cabins, not very fancy, but we all thought it was a great idea. We started up the line through company commander, a young officer; and then the battalion commander, Gerald “Gerry” Wright, okayed it, much to our surprise; but when it got up to the commandant of midshipmen, he put thumbs down. We tried.

I've worked for Admiral Wright since then and he's kind of one of my idols in the Navy. We all know Uncle Beanie. I was in London working for Admiral Wright when Admiral Jarrett came to call and they just passed me and he called me by name.

Donald R. Lennon:

He seemed to be fairly popular with the men.

John G. Messer:

Gerald Wright, that was another thing he did, I'm sure others have told you, he called you by name almost the first time he ever passed you in the corridors, because he had these little cards with your picture on it and your name. It was pretty clever.

Donald R. Lennon:

That is a talent, or an ability, that is much to be admired . . . to be able to put names and faces together early on when you first meet someone. Any other thoughts or recollections of incidents at the Naval Academy?

John G. Messer:

No, I was probably a pretty good boy. Mother wouldn't ever let us out of the yard. I didn't go over the wall.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't another Joe Taussig, in other words?

John G. Messer:

No, they threw the mold away with Joe I think. I can't think of anything too spectacular or interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your first assignment after graduation in the Spring of forty-one was to the. . . .

John G. Messer:

The first of March, I went on a brand new destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

And what was that?

John G. Messer:

The USS MADISON (DD-425).

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the MADISON?

John G. Messer:

I joined it at Newport, Rhode Island.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it stationed out of Newport?

John G. Messer:

Yes, we were out of Newport at that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, during the spring and summer of forty-one, you had duty primarily in the North Atlantic.

John G. Messer:

Right. To go back a little bit, when I got on this ship, she was going through her sea trials, she was brand new. One thing that was interesting to me was that they put the rudder over at full speed and that thing would heel over like a sailboat; then they'd be going ahead full and ring up emergency back and they went from something like thirty-two knots ahead to twenty-two at stern in less than a minute. The whole ship just shuddered.

Donald R. Lennon:

But that was normal.

John G. Messer:

That was fine. That was part of the sea trials. Several things happened on that ship. There was a book called Mr. Roosevelt's Navy that talked about before the war started. Of course, we were part of that. The first convoy we took was from Norfolk or Newport, I've forgotten which, but it was composed of one of our own hospital ships that had the red cross lit up on it, and four destroyers. We didn't know what we were doing. I guess they were just trying to see what the Germans would do, if they'd attack and come up to Newfoundland.

Then, I got in on the meeting of Roosevelt and Churchill, which was held in Argentia [Newfoundland]. I guess you probably heard about that one. Roosevelt went to sea on his yacht, supposedly to rest, and we were all in Nantucket in a little harbor and he steamed in there. We had a cruiser with us, I can't think of the name, but Roosevelt transferred to the cruiser and we took off for Argentia. One of our jobs, as destroyer, was to form a picket line on the entrance to Argentia, which was several miles long. We put our motor whaleboats in the water with an officer and several enlisted men and a couple of guns. We putt-putted between ships trying to make sure no one sneaked in there when the fog came in.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was going to say, even when the weather isn't particularly bad, you have a fog problem in that area, don't you?

John G. Messer:

We had it all right, and those little twenty-six foot motor whaleboats could only make about five knots. When we would hear "putt putt" coming , we couldn't catch it. It was usually a fisherman coming. We didn't have any problems.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you doing any other convoy duty other than that?

John G. Messer:

Oh yes, after that we were running convoys up to the chop line [an area where two opposing currents meet]--up around Iceland. The British escorts would meet us out there and take over, that is if there was a convoy left. Once the weather turned bad, the masters of those ships--they hated trying to stay in those lines--would disappear and come daylight, you wouldn't see a merchant ship anywhere.

Donald R. Lennon:

It wasn't so bad during the summer of forty-one, but were you there during the winter?

John G. Messer:

I was there during the winter of forty-two and the latter part of forty-one. That's when it was really bad.

Donald R. Lennon:

Describe the conditions.

John G. Messer:

Well, mountainous waves. I don't know how in feet you would describe them. I can remember steaming with one engine going faster than the other, just to try to keep the sea on the starboard or port bow. Those ships, in those days, had a gun director that was on a column above the bridge. I was assistant gunnery officer and became gunnery officer and my job was up there. If you've been sailing, you know that when you go over, you like to come back immediately. She'd get over and shudder and come back, and at the same time, we'd get ice all over the lifelines and the guns. Of course, that weight was awful dangerous. I remember coming off watch one night from the gun director. The captain was talking with the first lieutenant and the engineer and they had the stability curves out. I heard him say, "Well, we've already passed this stability."

Donald R. Lennon:

There wasn't anything you could do about it, was there?

John G. Messer:

Well, you have to take on water, take on ballast, if you can.

Donald R. Lennon:

Being a new destroyer, was it equipped with radar with bedsprings?

John G. Messer:

Yes. We also had sonar, and between the two of them, we chased submarines all over the ocean that weren't there.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that's particularly bad up there where there's so much ice, and icebergs, and things of that nature.

John G. Messer:

We didn't get in the iceberg category at all. I don't know why. We were south of Iceland. I never did see an iceberg.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have any encounters with actual submarines?

John G. Messer:

Well, we dropped lots of depth charges, but we had no positive proof.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were never any attacks on the convoy?

John G. Messer:

Not on the ones we were with. Others were attacked two hundred miles ahead of us. In one convoy, the REUBEN JAMES was sunk before the war. The KEARNY was torpedoed. She got into Iceland afterward and we came in about a week later. We took our damage-control people on board to see what could happen when you get hit.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they weren't trying to help repair things. They were just observing.

John G. Messer:

Just to know, so they would know how to shore things up if we had any problems. The bunks were made so we could strap ourselves in.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long would one of the normal cruises last on a convoy cruise like that?

John G. Messer:

Well, by the time we left port and got organized with the convoys, and by the time we got to the chop line. . . . See, this was another problem. You had to go with the slowest ship, of course, and some of them were down to eleven, twelve knots. It could last a couple of weeks.

Donald R. Lennon:

Depending on the weather, of course, among other things.

John G. Messer:

That's true, and the chop line. Then we'd all go into Iceland. We used to go up--I think it was ____fjord--a little fjord, you went up quite a ways and it opened up into a little harbor. It had some mooring buoys there that we tied up to. We used to put our anchor chain through the buoy and bring it back on board so that we could get away in a hurry and pull it in.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now you couldn't do that during the winter, now, could you? Was that open during the winter?

John G. Messer:

You know, they get Greenland and Iceland mixed up. It's Greenland that gets so much ice all the time.

When the winds started blowing and everything, we'd go around there and secure to this mooring buoy, and we would have to steam up to seven or eight knots just to keep a heading into that buoy. It was really tough.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long did you stay on the MADISON?

John G. Messer:

Let's see, I went on in March of l941 and I got off in January of l943.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other particular incidents with regard to the convoy duty on the MADISON?

John G. Messer:

Yes, there were some interesting things. We went over and worked out of Scapa Flow with some of the British Home Fleet for a while. The TRIPITZ was in the fjords of Norway and when the convoys were crossing north of Iceland and around the cape, she'd steam out and just shoot away at them. So, we had a task force with a British battleship and a U.S. battleship. Each had two or three cruisers and about eight to ten destroyers. We were quite a force, and whenever the convoys were going to pass, we would steam out of Scapa Flow between Iceland and Norway or the Shetland Islands and Norway, hoping the TRIPITZ would come out.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was in forty-two after we had actually gotten into the war.

John G. Messer:

Yes. One other interesting kind of job was when we escorted an American carrier. I've forgotten which one it was, but she took on a whole squadron of British Spitfires to go down to help relieve Malta. We rushed into the Mediterranean because the Italians had a lot of submarines down there. I guess about three hundred miles away from Malta, they launched those Spitfires, and we turned around and hauled ass, so to speak, out of there.

I was on the watch once and got the life scared out of me. I saw bubbles coming right toward the ship. I called for the captain, but I had enough training to know you turn and try to go parallel. That's the only time I saw a. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

What you thought was a torpedo heading to you.

John G. Messer:

It was kind of scary.

Donald R. Lennon:

But it didn't hit anything. It just went right on by?

John G. Messer:

Yes. Later on we went over to the Casablanca landings and were escorting a battleship and a cruiser. We didn't really get too involved. They had secured the port by the time we got there. One of the French battleships was in the port in Casablanca and couldn't get underway, so while alongside the dock, she fired her guns out to sea, trying to hit things, but she didn't hit anything.

There was another thing, as a young officer, that kind of impressed me a little bit, upset me. We went inside the harbor of Casablanca and there were U.S. merchant ships in there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, exactly when was this?

John G. Messer:

This was forty-two. I don't have that many details here.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's ok

John G. Messer:

Landed in Casablanca in forty-two. I think it must of been October or November of forty-two because I remember coming back in December of forty-two. My wife informed me that I was now a lieutenant, which of course, you didn't hear about in those days. That was the last. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Go ahead. I didn't mean to interrupt you.

John G. Messer:

Well, going into that harbor, the shooting had stopped and we were ordered to tie up alongside a merchant ship. It was about five o'clock in the afternoon. We approached the merchant ship and sent monkeys fists, [the weighted knots] that take the lines over. There were some seamen on deck and they wouldn't touch them because they were through work for the day. Here we had all these young kids, these young seamen, you know, that were making, eighty or ninety dollars a month and these merchantmen were getting all this super extra. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

This was an American ship?

John G. Messer:

Yes, and she wouldn't touch our lines. The captain had to bring the MADISON actually alongside and our men had to go over on their deck and take our lines in. I thought that was horrible. That's pretty much the end of my time on the MADISON. I got off of her in January of forty-three, right after we got back.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were assigned to the KIMBERLY?

John G. Messer:

Yes, the KIMBERLY.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was assigned to the South Pacific?

John G. Messer:

Well, I joined her at the Staten Island Bethlehem Steel Ship Building docks. She hadn't been finished and they put a skeleton crew on. I went on as gunnery officer. That was in February. Then we put her in commission and we had quite a shakedown period. It was September of forty-three when we left for the Pacific. We got to Pearl Harbor about the twenty-fifth of October. I remember this because my wife was pregnant when I left and the baby was due on the twenty-ninth of October. Then, we found out we were sailing on the tenth of November to go down on the Makin-Tarawa deal. I kept checking with the communication officer to see what the news was. We returned after Tarawa and Makin on

the twenty-fourth of December. That's where we got all our mail. The Red Cross would send word to the Pacific Coast, and from there on messages didn't come by radio, they just them in the mail sacks. We hadn't had any mail for a month and a half at least.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you involved in any engagements on that run?

John G. Messer:

Well, not particularly. What happened to us? I think we bombarded Makin a little, but when the Japanese task force would come into the islands in the daytime and at night, we would run away, circle around and come back at daylight. I saw one baby carrier get torpedoed and go up in a big ball of flames. We damaged a propeller and as a result, they sent us into what you'd call a lagoon, at Makin. We anchored in there and we got to shoot at some Japanese planes. They were more reconnaissance than anything else. They'd dive out of the clouds, but before you could get a twenty millimeter or a forty millimeter trained on them, they would be gone. We didn't get down to Tarawa at all, where the worst battles were.

Donald R. Lennon:

You went back to Pearl in December of forty-three.

John G. Messer:

That's right. I don't know why. I guess we got our propeller changed in Pearl Harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they weren't able to do it there in Makin.

John G. Messer:

No. There is nothing there. Really, those islands are isolated. There were Japanese all around.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't know whether you had a repair ship with you.

John G. Messer:

No. We had to kind of go back on one engine. Another thing happened when we did get back. We got a message from BUORD saying that other five-inch guns had been cracking in the breech block. The captain told me about it and I got the chief gunner's mate

and we looked at all the five-inch guns. Sure enough, one of ours had a hairline crack in it. So, we reported it and they sent us to San Francisco. San Francisco had never pulled one of these five-inch guns and it took them almost two weeks to figure out how to do it. We had a marvelous time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now what was your duty station? What was your primary responsibility?

John G. Messer:

Gunnery officer.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were gunnery officer the whole time.

John G. Messer:

Up until then, yes, I was the gunnery officer. Once we finished up in San Francisco, they ordered us up into the Aleutians to Adak, and we worked out of Adak. Then the exec got transferred to take command of a destroyer and I became the executive officer. This was only a matter of months now, but an interesting thing happened there when we made a night run on the Kurile Islands and bombarded them with our five-inch guns at two in the morning. They didn't know what it was all about. We were bombarding an air field and you could see the tracer bullets going up in the air. They thought they were being bombed by planes. Supposedly, it hit the headlines. Supposedly, it was the first bombardment of Japanese homeland because the Kuriles belonged to the mainland. We turned tail and went back to Attu and Adak. Nobody chased us.

Donald R. Lennon:

The duty up there could be pretty hairy at that time, couldn't it?

John G. Messer:

From the Japanese? Oh no. You see, the Japanese had already gone. They had occupied Attu, you know, but they'd been driven off.

Donald R. Lennon:

They had withdrawn at this time.

John G. Messer:

We didn't see any Japanese at all. The weather was . . . I told everybody the difference between the Atlantic and the Pacific was that in the Atlantic, you'd have six

horrible days and one nice day. In the Pacific, you had six beautiful days and one bad day, but [the one bad day was] nothing like the North Atlantic.

Donald R. Lennon:

After a year or so in the North Atlantic, this was a piece of cake.

John G. Messer:

Yes, it was. Everything about it was pretty nice duty. I got transferred off in September of forty-four back to the Naval Academy for post-graduate school.

It was an ordnance engineering course. It wasn't the greatest, I didn't think. The course involved mines and depth charges and degaussing. When we got into Navy stuff, then some of the higher math and stuff knocked me pretty cold. It didn't seem to make any sense or that it was anything you'd ever use in life. I didn't get a degree because the course I took was at the post-graduate school and they were not authorized for advanced degrees. They are now, I believe, out in California. A lot of people that were in other programs after a year or year and a half in Annapolis, went on to MIT or Cal Tech or something like that and did get degrees.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long did this last? Was this a nine-month program?

John G. Messer:

No, it was longer than that. In October of forty-four, I got there, and finished the course in June of forty-six.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, it was eighteen months.

John G. Messer:

Then I went back on destroyers again. I was executive officer on destroyer minelayer, the HARRY M. BAUER (DM-26). Then, of course, they were laying up all these ships. We stayed tied up to a dock in Charleston, South Carolina, for almost six months--probably the worst six months in my Navy career. I won't name any names, but I had a commanding officer that had come off a cruiser and he'd never been on a destroyer in his life. He and I just didn't hit it off. His wife and my wife were good friends and she told

my wife how tired this man was when he got home; he'd been working so hard. I told my wife, "I had to wake him up every afternoon and tell him that it was time to go home." Anyway, I'm not going to name him of course, but finally after six months we did get off.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was very routine duty, I would think, in Charleston in the summer and fall of forty-six. Wasn't a great deal going on?

John G. Messer:

Yes, it was horrible. I just said, it was the worst period of my Navy career--not only because of the captain, but we weren't doing anything. Morale was low. They put us out on the end of a long walkway out to a T-dock. The walkway was full of rats and trash.

They called me up with Navy investigators or something and said they'd found a whole bunch of empty beer cans down on the end of the dock and it was all our fault. My crew and I checked around and found out they'd been there for ages, but I got called up before the commanding officer. I told them it wasn't our fault. I don't know. . . . It was just the worst six months in my Navy career.

The same commanding officer, when we did get underway, I said to him, "You've never had any experience on destroyers.” In cruisers, they start about four hours ahead of time, lighting off the boilers, and stationing the watch. We were going to get underway early one morning, seven thirty or eight. It was hot down there. We were in Guantanamo Bay then--very very hot. I was executive officer and a lot of the crew were sleeping on deck. You're not allowed to use the topside speakers, so I told the officer that was going to be on watch, "You go ahead and use them, but speak very softly. Tell them to speak very softly because we're coming up to get the crew moving.” I was in the wardroom for seven a.m. coffee and the captain steamed in and blew his top at me, "You can't use the loud speakers, we've got to get underway and should have all. . . ."

I just told him, "If you'll stay off the bridge, I'll guarantee we'll be ready to go." He knew nothing about destroyers. He didn't know how to handle the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Obviously, he didn't know how to administer other men.

John G. Messer:

I don't why they ever gave him command of a destroyer. One time we were getting away from a dock and he said, "Starboard engine back one third, port ahead one third, twisting a little bit of something."

I said, "Captain, that's what the engines are doing." He blew his top.

He said, "Well why didn't someone keep me informed." From then on, he was on this side of the bridge and I was over on that side of the bridge. It was awful!

There was a fellow out of [class of] thirty-five, Johnny Cotten, who was in BUPERS. I called him up and said, "I can't take this anymore! See what you can do."

He gave me command of a high-speed destroyer transport. He said, "I thought you'd like that better than executive officer of a cruiser."

I said, "I sure would." That was funny, too. When I got my orders, the captain had let me make one landing, finally. I had a lot of experience already. Once my orders came in to command my own ship, he says, "Well, now you can practice on your own ship." Just like that. This guy was impossible. I'm not going to ever tell you who it was either. So, don't worry about that. Those are the little things that happen on destroyers. It's a different world in the destroyer world. I love it!

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, you went to the high-speed transport from there.

John G. Messer:

Yes, that was in June or July of forty-seven. They are called APDs. They are known as high-speed destroyer transports because we were responsible for either carrying the SEALs or underwater demolition teams ahead on landings. We also carried four landing

crafts. We had Marines on there most of the time. We just trained for landings and things like that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where specifically? On the East Coast?

John G. Messer:

Yes. This was in Norfolk.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you headquartered out of Norfolk.

John G. Messer:

And it came under, because it was working with landings primarily, the Amphibious Force. That's where the A came from. We had some good duty, but it was nothing.

I remember one thing. I was with an APA and an oiler in Miami. and a Marine group--I don't know whether it was the Marine Corps, retired Marines, or what--there for a reunion. One of the things the whole crowd did was that they broke out some flame throwers and chased some little young ladies with grass skirts up the beach. It was all just kid stuff. The Marines had a demonstration in the Orange Bowl, but then a hurricane was coming along and it looked like it was going to hit Miami. The port captain said the big ships would be safe alongside the dock, but the little ships, like I was, better go to sea. With Miami in a hurricane, where do you go to sea? You're right into the hurricane. If you turn north, often hurricanes go that way and if you turn south, they might go that way. So I said, "No, I'm not going to sea." They moved me from where I was, rather exposed, and put me on one of those big commercial ship's slips. The walls were practically higher than my ship and we put out a lot of extra lines. I remember listening to the radio on this approaching hurricane until about quarter of twelve at night, and it was getting closer. It wasn't the worst kind. It was something like a hundred and twenty-five miles an hour. The

next thing I knew, I woke up about eight in the morning, the sun was out and we didn't have any damage at all. Of course, they would have called if we had had any problems.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, if it had come right in there, it would seem to me that in a situation where you're tied into docks that there could be substantial damage not only to ships but the entire dock area completely destroyed, too.

John G. Messer:

I don't know whether it calmed down when it came over the Bahamas or something like that, but the only thing I was worried about was high water, the lines parting, and stuff like that. It didn't cause much damage.

Donald R. Lennon:

It must have gone into the Gulf or something.

John G. Messer:

Yes, it went over Miami. It went right across Florida. That was just a fun tour. That was just a year. I was relieved of command and I had no orders, so I called the detailer at BUPERS and said, "I'm wondering if you're thinking about me. I just was relieved this afternoon."

He said, "Oh yes, you're going to an aircraft carrier."

I said, "An aircraft carrier?"

Donald R. Lennon:

I was wondering when the aircraft carriers were coming in, because I knew you had had a couple of duties.

John G. Messer:

I said, "I've never been on anything bigger than a destroyer."

He said, "Well, you can shoot five-inch guns can't you? You'll be going on as gunnery officer." I was a lieutenant commander by then. So, I did.

Donald R. Lennon:

What aircraft carrier was it?

John G. Messer:

That was the PHILIPPINE SEA (CV-47) based in Newport.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were the gunnery officer?

John G. Messer:

I was the gunnery officer on there, yes. I was gunnery officer and assistant captain. The captain of course, is an aviator. The exec is an aviator and the operations is an aviator. They're all aviators except the engineer officer and gunnery. Whenever there were some night operations and steaming at night . . . boy. . . if the captain didn't want to be disturbed, he'd ask me to spend some time on the bridge. He had a little confidence in me, I guess. He used to call me the assistant captain.

Donald R. Lennon:

How different was duty on an aircraft carrier as opposed to your destroyer service?

John G. Messer:

Well, it's like night and day.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it difficult to adapt?

John G. Messer:

Not really. It was kind of a pleasure in a way. I had a cabin that was so large, it was unbelievable, much larger than anything that ever existed on a destroyer. We had liquor--illegal liquor. The supply officer, the first time we went to sea, asked me where I'd like my liquor and I said, "What do you mean?"

He said, "Well, the captain has authorized each department head to have two cases of whatever kind of liquor they want. It's a gift. He'll even pay for it."

I told him what I wanted, and one of his men came dragging it into the hanger deck with the mail sacks. I slipped it up in the cabin. I had a big cruise box in there so I put it in the box, shut the cabin, and left it there until six months later when we got back to the United States. In destroyers, I've never seen any drinking going on. That was kind of an eye opener. I don't blame those aviators. That's a rough life. In destroyers, I chased aviators enough as plane guard, you know, to see those night landings and ships pitching and all that. It's pretty hairy.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think the aircraft carrier would be much more substantial in the water than

the destroyer.

John G. Messer:

Oh, yes. Riding it was fine. The worst part of was I also had all the first lieutenants under me responsible for painting the ship and all those dirty jobs.

We were coming in to anchor off Cannes, and when you're getting ready to anchor, you're hidden in the bow, under the flight deck. All you can depend on are the men on the telephone and on the bridge. They had a thing for anchoring, the guy would yell out, "ready" to us and then next time “let go.” You'd take a sledgehammer and you'd break the . . . let the anchor go, all fifteen tons. Well, we were making this landing and I thought we were moving kind of fast still, and the guy yelled out, "Let go." So to the guy with the sledgehammer, I said, "Let go." On the bridge they had bypassed the standby and gone too far to let go. The minute the kid saw it, even though they pulled it back up there, he yelled "let go." The executive officer came running down, but we survived. We were able to stop it, thank goodness.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you stopped the anchor before it got down?

John G. Messer:

Yes, because we were in deep water. We anchored off Ali Kahn's home, which was a very nice home with a swimming pool in the backyard and a chute from the swimming pool into the ocean. His lady friend in those days was Rita Hayworth and I had the command duty in port. The admiral we had on board was part Indian. He invited Ali Kahn and Rita Hayworth and some of their friends on board for dinner. As the command duty officer, I had to be at the gangway and, of course, the gangway was right by the hangar deck. They came on the hangar deck and then went up to the admiral's quarters. We held up the movie because it had been dark, but there were five or six hundred sailors out there. I had the job of using the little speaker phone to announce who was coming on board. I expected them to be polite and

not to make any noise or anything. Ali Kahn had just busted a foot in a skiing accident and he was on crutches. She came on board and the admiral greeted them, and the captain and I were just standing there. They turned to go to the admiral's stateroom and she waved to the sailors. All this yelling went on and Ali Kahn, when he came by me said, "Jesus Christ, it's just like being in a fish bowl." Nobody blamed me. There wasn't much that I could do about it. I told them not to make any noise.

Donald R. Lennon:

But when she waved at them, that was the signal. I'm sure she always relished the attention that went with her stardom.

John G. Messer:

She was probably wondering, "Why don't they do something?" She just waved her hand a little bit and wow! That was just a little thing. There's not much in my career to put in the records or anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is forty-eight, forty-nine?

John G. Messer:

July of forty-eight, I'm on the PHILIPPINE SEA and I don't know if it was the winter time that we went over to the Med. That was a one-year tour. I got off in August of forty-nine.

Donald R. Lennon:

And what was your assignment after the PHILIPPINE SEA?

John G. Messer:

I was sent to the Naval Mine Depot in Yorktown, Virginia. It is now called the Naval Weapons Station. That was, of course, all because of my post-graduate thing. When you take an ordnance engineering course, when it comes to going to sea, the Bureau of Ordnance doesn't get involved. The BUPERS will send you where they want to send you. When you come ashore, the Bureau of Ordnance, because you're an ordnance post-graduate, decides where you're going to go on the shore.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had had quite a bit of sea duty by this time. You were due for some shore duty.

John G. Messer:

You always do when you're young and a junior officer, more or less. By then, of

course, I was a lieutenant commander. Yorktown was very interesting because that was the first time that carriers were carrying nuclear weapons. We were the storage for them on the East Coast at the Naval Mine Depot.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they were carrying nuclear weapons by forty-nine?

John G. Messer:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they really?

John G. Messer:

A lot of people didn't know it.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't realize it.

John G. Messer:

After that--missiles, nuclear missiles, and things--these different countries wouldn't let your ships in.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because they knew it.

John G. Messer:

It was all pretty hush-hush and they were stored in a magazine, so to speak, that was actually a shed above ground. It had double fencing around it and Marine guards out there twenty-four hours a day.

Donald R. Lennon:

Could you use the normal gunnery on a ship for a nuclear shell, or did there have to be some special type of gun for firing a nuclear shell?

John G. Messer:

Well, nuclear weapons is a wide subject. You get nuclear weapons in all different shapes. The Navy didn't use any guns. No, these were aircraft-dropped in those days. Then, during my last destroyer days, we had nuclear weapons, missiles.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they were strictly for the airplanes on the carriers.

John G. Messer:

Yes. Then destroyers started carrying them. In the area where they were kept, you had to have a special pass. It was guarded all the time. I don't think I'm telling any secrets out of school. The missiles on submarines and destroyers and everything controlled the size

of the ships. Destroyers used to be thirty-to-one in dimension -- narrow -- and you stored these missiles pointing up, on a racetrack type of thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was the way I visualized it.

John G. Messer:

They'd come up, which looks like a gun mount actually, and hook on and then swing around. Submarines are the same way. They don't go on a mount. They are fired with a different type of intercontinental ballistic missile.

Donald R. Lennon:

At this time, things were beginning to warm up in Korea, were they not?

John G. Messer:

Korea, yes. That is when Korea was pretty hot. I was in Yorktown until fifty-one. As a matter of fact, it was getting real hot, I think.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they transporting any of the nuclear weapons on to the aircraft carriers off Korea?

John G. Messer:

Not that I know of. In other words, this was brand new. We weren't in quantity production at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's why I was kind of surprised.

John G. Messer:

I had never seen a nuclear weapon. The captain, commanding officer, the executive officer, and myself, and the so-called gunnery officer of the mine depot all had a special clearance that allowed us to go in the area where these were kept. You had to read the temperature in the warehouse twice a day and there were one or two civilians that were authorized to go in just to record the high and low readings on the temperatures. One of us had to be with the civilians while they went in to read the thing. The weapons in there were all in big boxes. They were of tremendous size. It was pretty interesting--another interesting little side trip.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is the kind of detail that we want. We like all the specifics that we can get.

John G. Messer:

The WILLIAMSBURG, the presidential yacht, came in with Harry Truman on board and tied up to our dock on the York River. I was in charge of handling the lines with some sailors. I was down there and the lines were coming over and I was just checking everything and all of a sudden, I looked up and I was looking right in the face of Harry Truman. I said, “Hi, Mr. President.”

The York River was great for oysters and our piers had concrete pilings. Some of the men in special weapons, this group of sailors, were divers. They would take a GI can and go down there with hammers and just knock the oysters off the pilings. Somehow, the President heard about this and he sat down with four sailors one night, right there on the dock, shucking oysters.

Donald R. Lennon:

That doesn't surprise me. Truman was just the type that would do that very thing.

John G. Messer:

Truman liked to walk every morning. My boss, the gunnery officer, was designated to walk with him around the grounds and stuff.

I went there in August of forty-nine. I left there in October of fifty-one. That was kind of interesting. I was really enjoying it, but in those days, two years was really too long to stay any place, the way we kept moving around. So, I went to see the commanding officer and I said, "What do you think, career wise? I love it here, I love the duty, but I don't know whether I should stay on too long." By then, I had become the gunnery officer. He said an admiral from Charleston was coming through the next day. He would talk it over with him and see what he could do.

Before he got there the next day, the commanding officer called me and said, "Guess what. BUPERS just called. You're going to London." I got pretty excited about that.

I called up my wife. We had quarters on the base, which were very nice--two big homes. She was making soup or something in the kitchen and I said, "Guess what? I got my orders and I am going to London." She thought I was going alone and was really upset. Of course, I wasn't going alone.

That was October of fifty-one. I went over to London to CINCNELM staff. Actually, by the time I went to CINCNELM, it had moved down to Italy and they had what they called COMNAVEASTLANT in London, Commander of Northeast Atlantic. Gerald Wright was in there as the boss. I was there two years. It was delightful duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have to travel back and forth between London and CINCNELM headquarters in Italy?

John G. Messer:

Not to much in CINCNELM. I was in operational readiness and training. NATO was very much in being and I had to go to a lot of NATO meetings in different places: Italy, Malta, France. I got to travel quite a bit which was very enjoyable. I went to Malta once with Admiral Gerald Wright. He went on a little trip to meet Lord Louis Mountbatten and that was kind of fun. We had a private Navy plane. We were supposed to take off at four. Admiral Wright showed up with Admiral Mountbatten about quarter past four. They stood there talking outside and we were all waiting around. The admiral brought Lord Louis over and introduced each one of us to him. Things stick in your mind, little things like that. That was great duty.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would think London would be fantastic duty.

John G. Messer:

In those days, you got a hardship allowance, extra money, and we rented a house cheaper than we could possibly rent in the States. We had a British housekeeper and she said she'd stay with us for two weeks to see if we liked her and if she liked us. She put it very

bluntly. She was there two years, and so were our kids--two daughters, five and eight.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well that was really hardship duty, wasn't it?

John G. Messer:

We were getting this extra seven dollars a day for nothing. I mean, things were cheaper over there. Rationing was still on, of course. I went to get coal and coke allowances for the house. Just before me, there had been some American diplomat getting some and they took for granted that I was a diplomat, too. So, they gave me a non-restricted allowance. We could get as much coal as we wanted. The housekeeper couldn't believe that.

At the same time, we had an American commissary right in the basement of 7 N. Audley St. where the office was. Do you know London fairly well?

Donald R. Lennon:

Fairly well.

John G. Messer:

That was good duty. There wasn't an awful lot to do, unfortunately. Another classmate and I, George Brant, used to take some pretty long lunches just like the British, a couple of hours roaming around London.

I left there and got command of another destroyer in December of fifty-three, USS SOLEY (DD-707). On the fourth of January, we sailed for the Pacific. This is hard on the family, as you probably realize.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, they went back to the states?

John G. Messer:

We had gotten back to Norfolk. The ship was there and we had gotten an apartment already, so they stayed right in Norfolk. That was quite an experience. The Korean War was just about over when we were out there on the SOLEY. That is why they were sending ships from the Atlantic--to supplement the Pacific Fleet during the Korean War. We steamed out there and we were in the area for four months in different Japanese ports. We got to Hong Kong and Okinawa. They had a nice little war zone around Korea and you got extra battle pay if you were in that zone, so once a month we made sure we steamed through.

When we were coming back, the habit was to send ships from that duty back to

Singapore, Ceylon, through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean, and on to Norfolk. Somehow the Navy got an invitation from the South African Navy to have ships visit there during their bicentennial or something like that. We were chosen, the four of us; so when we left our duty in that area, we went to Hong Kong, Singapore, Ceylon, Sri Lanka, Mombasa, which was the port for Nairobi, and then down to Durban, which is the Miami of South Africa. From Durban we went down to Capetown, from Capetown across the South Atlantic to Rio, up to Trinidad, and back to Norfolk. Ten weeks and nothing to do but relax and steam and party. It was really good.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was a peacetime assignment.

John G. Messer:

The Korean War was ending up and we didn't ever get involved in it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you arrived back in Norfolk, you still were on the SOLEY though.

John G. Messer:

Yes, I was on it for two years and everything we did after that was a peacetime type of thing. Fun things mostly--training. We did get down to Cape Canaveral once to take aboard about thirty of the Secretary of the Navy's guests, to take them out and watch a submarine send up a missile. That was fun.

Then came January of fifty-six, I got orders again. The Bureau of Ordnance got a hold of me and sent me up to Newport, Rhode Island, where they had an underwater ordnance station. I was in a little division called the U.S. Navy Central Torpedo Office. This was an interesting job. During World War II, there were lots of torpedoes that hit and didn't explode. At the old torpedo station in Newport, they had good men, but a lot of the plans--the drawings--had been “written on their sleeve” or something, so they established the Central Torpedo Office. We kept the drawings of any torpedo depth charges that were manufactured. Of course, the manufacturers had them, also, but if they wanted to make a change, they had to send the changes to the U.S. Central Torpedo Office. We had about two hundred ten civilians, and there were only three other officers and myself. We had to approve any changes. We were trying to make it so that if you needed more torpedoes or anything, the drawings would all be the same and not from different people. It was a pretty important little office and quite a few G12, 13, and 14 engineers were there. I enjoyed it, but I stayed there a little too long, I think. It probably hurt my career. I did pretty much all the right things, but BUPERS kept me there from fifty-six to fifty-nine.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was a long time.

John G. Messer:

It was three and a half years and that hurt me, I found out later on. Some in our class had to be selected for retention, in other words, to go. They were thinning things out and I made that all right--you had to be selected for a major command if you were going to get one. You have to be selected for different colleges and all that stuff. I was doing fine. I wasn't selected for a major command and then I found out what happened. One admiral didn't like me and this is what hurt me a lot, plus the three years in a shore station like that. But, the next year I did get selected for a major command.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's interesting how much the right assignment and politics play into the careers.

John G. Messer:

Yes, Zumwalt, as you may have heard and probably know, changed things a lot. If you had a certain job and two captains, one of them would be promoted to the chief of staff to the Commander Destroyer Force Atlantic or Pacific Fleet. One year they would select the Atlantic Fleet to be chief of staff for admiral and the next year, they'd select the Pacific Fleet Chief of Staff. There were other jobs that if you got them, you were going to make it. Zumwalt was the first one that really kind of selected people for the job they did, whatever job they were in. They got away from this whole routine. This is when the first non-Naval Academy graduates were beginning to be selected for flag rank. As far as I'm concerned, those guys that stayed in, those ninety-day wonders before the war, did a good job. They were getting selected for admiral, too. Now-a-days, I don't think you can tell who's who anymore. Selection is much more fair.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your command in fifty-nine, you said you got assigned to a major command.

John G. Messer:

I got command of the Destroyer Division 82. That was 4 DDR's which have got the R for radar. We always worked with carriers because we had TACAN on board. Are you familiar with TACAN? That's the homing system for aircraft from a carrier. We always worked with carriers because if the carrier's TACAN went out, we were available to bring the fly boys back to the carrier. That was fun. That's when I first worked with Admiral Moorer. I'm sure you know Moorer. I'll tell you one thing about Moorer. He was extremely personnel-oriented and thoughtful and concerned. I first called on him in Mayport. We were going to go to sea with him and he said, "In lifeguarding, how about your sailors? Have they got waterproof suits?" He wanted to get right down to detail, you know, What is the procedure if you had to jump in to cover some of these sailors?

We went to the Med with Moorer and on the way back from the Med, he wouldn't allow the pilots to fly off the carrier on the way back. He thought they were too relaxed going home. We may have lost a couple on the cruise, but we didn't want that to happen on the way back crossing the ocean. He was a very personnel-oriented person. I have an awful lot of respect for Admiral Moorer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where was the Destroyer Division 82 homeported?

John G. Messer:

We were out of Newport, so I didn't have to change. I was already stationed there, but like everything else, within four months, they moved us down to Mayport. We worked out of Mayport and that is when I went with the carrier and the admiral. There again, that job only lasted a year, I think, October fifty-nine to October sixty. By that time, they were sending destroyers, particularly destroyers in for rehabilitation, putting them out of commission. My division didn't go with the other division but the squadron did. That took the squadron commander, so I had the temporary job of squadron commander for a few months. After that, I finally went to Washington. I'd shied away from it all those years, but. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

It is always a necessary part of life.

John G. Messer:

I would advise anybody, now, to go early in their career and find out how the government runs. If you go there as a fairly senior captain and you've had command and everything, you find out that you are nobody and you cannot even sign a letter by direction.

Donald R. Lennon:

This is late in sixty that you were sent to Washington?

John G. Messer:

I went in November of 1960. I went to OPNAV to work in the Undersea Warfare Research and Development division of OPNAV. I stayed there until July of 1963.

Donald R. Lennon:

And this is pretty much just routine?

John G. Messer:

I was mostly involved with the research and development in mines and depth charges and that kind of thing--degaussing. There wasn't an admiral in the Navy that had any interest in mines, mine sweeping, or anything like that. Every time, I got either a cut in money or any money I had was usually cut off. It was pretty sad. It took the Vietnam War to bring mine warfare into being. It's kind of sad, really.

Donald R. Lennon:

So between World War II and Vietnam, the mine. . . .

John G. Messer:

There was no interest in mine warfare or development of mine-sweeping type of things--magnetic, pressure mines, contact mines, and stuff. Like I say, when they start cutting money, they cut it out of there ahead of other things. The admirals just didn't know anything about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Interesting. As long as you have surface warfare, I would think that you would see the hazard of not keeping up to date on developments in mine warfare because of the potential enemies.

John G. Messer:

Well, the other thing was that after the war, the British Navy went down as did the Dutch, but the one thing they kept were mine sweepers, so they did a lot of sweeping in the English Channel and all those places. Then NATO came along and I guess the higher ups in our Navy thought, Well, let them. Let those countries handle the business of mine sweeping. We didn't pay much attention until Vietnam and then when they did start using them, we got a lot of attention.

That was kind of a nice job, and luckily, from there, I got sent to the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. That was for a year and that was just great. While I was there, I picked up an MBA to tie in my Industrial College work and with George Washington University.

From that job, I then went as chief of staff to an admiral, an aviator admiral, on a carrier. He was Commander Carrier Division 14. First we were working out of Boston on the aircraft carrier, USS WASP (CVS-18). I think she was the fifth in line of all the WASPs. There were a lot of WASP carriers in the Navy. That was some experience for a destroyer sailor, I can tell you.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you had been on a carrier before so you. . . .

John G. Messer:

Yes, but as gunnery officer, I wasn't anything as far as the aviating was concerned. But on this one, unfortunately, I happened to be just a little bit senior to the commanding officer of the carrier. That didn't make him very happy. It wasn't anything really bad, but I am sure he didn't like it very much. Anyway, that was for me, a great job. I learned a lot. I liked the admiral and we got along fine. Then again, I only had it just about a year. Just as I got off, the ship was ordered to recover one of the astronaut shots. Remember, they used to come down in the water. We had a model of the thing on board and we practiced picking it up. But, I missed the actual thing--I got off just then. Here again, it was while I was on there that I got selected for a major command. I got command of a destroyer squadron.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said your flagship.

John G. Messer:

The BELKNAP (DLG-26) . We were working out of Norfolk. It was another Mediterranean-type tour. In August of 1966, I was back to the Pentagon again. I worked in the office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Naval Operations for Anti-submarine Warfare. At that time, it was Admiral Charlie Martell. I don't know if you've ever heard of Admiral Martell.

Donald R. Lennon:

It seems like I've heard the name, but I don't know.

John G. Messer:

He is a very tough nut; a very intelligent guy. He got selected for admiral one year, and I think it was President Johnson, wanted somebody else. Martell had been selected and had already had messages of congratulations from a lot of admirals when he got bumped politically, two weeks later. He resigned from the Navy! It was a pretty dirty deal. You

know how the presidents are. When they want somebody selected, they don't tell you who they want. They just wait until the right name comes up and then they ok the list.

There comes a time in your career--as I'm sure all the officers have told you--when you have two years and you're under the gun for admiral, it's your best chance of getting in. The first year, it just so happened the admirals on the board, hardly any of them knew me. I think two out of thirteen knew me. When they are selecting, they do like congressman, they do a lot of switching: You vote for my man, I'll vote for yours.

Donald R. Lennon:

Exactly.

John G. Messer:

Then, the next year, my boss was Admiral Martell. He was the senior vice-admiral in the Washington area and he was president of the selection board. When I heard that, I came home and told my wife, "I'm going to put in my papers and retire just before I'm fifty." The idea in those days was that there was a better chance of getting a job on the outside before you were fifty years old. Whether it was true or not, I don't know. I was in this little ASW group with him. He held all the purse strings for money for ASW, over the Bureau of Ordnance, Bureau of Ships, Bureau of “everybody else.” Charlie Martell was the king. A fellow named Al Bergner was out of the class of thirty-six or thirty-seven. It was well known that he kicked a field goal that beat Army one year in football. He worked in this little group and he was a favorite of Martell. Everybody knew Martell, when he got on the board, was going to pick Al Bergner. I had four captains working under me as a captain. We had five other captains in the small ASW group. As senior as he was, there was no way he was going to get two of his own people. So, I waited until the list came out, another month or so, and I just put in for my retirement.

Donald R. Lennon:

Went on out?

John G. Messer:

Yes, I got out, right.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you do after you retired?

John G. Messer:

Well, I went to work for a systems research corporation in Washington, D.C. This was a little company, I guess you'd call them a software company. They were basically doing studies for the Navy, they dished out all these studies. I put my resumé in with the Retired Officers Association and someone from this company went over there looking for people. They called me up, so I went to work for them. I think I was number eighteen or something like that, in the company. They got enough jobs for the next couple of years. They built up to over a hundred [employees] and then all of a sudden, things stopped, like they do, and they got back down to twenty-four. Well, I got my walking papers.

Then another retired officer and I formed our own little company and we started putting photocopying machines, IBMs, around in libraries. This was a fun job although I wasn't making a lot of money. We'd pay IBM and then we would get all the profits out of the libraries. We'd go collecting the money out of the machines and clean them for the libraries. But that was just a fun thing.

Then RCA came after me again from the Retired Officers Association and I worked with them about two or two and a half years. I was working in Virginia and my wife and I moved to Virginia Beach. RCA wanted me to set up an office down there to watch contracts coming out. I went down to look for office space and the next thing I knew, RCA said, "Sorry, the lawyers said this would be a conflict of interest." My wife had died suddenly and I had remarried, and my new wife was the owner and publisher of a newspaper in Alexandria, Virginia, the Alexandria Gazette. From then on, money didn't mean much. I mean, there was plenty of money available when she sold the paper.

I tell you one more thing that most people know about. I have had a rather unusual marriage career. I was married twenty-six years to the same woman, and I was still married to her when I retired. I was working with Systems Research Corporation. I came home one night and found her unconscious in the bathroom. She died that night of a massive cerebral hemorrhage without any warning whatsoever. About a year after that, I met this lady that owned the newspaper, which didn't excite me too much, but we kind of fell in love. When you marry someone that has money, the paper and everybody thinks you're going to try to take over the paper. They wanted a pre-marital agreement. She didn't want it and I didn't want it. We were married fourteen years. She was working a crossword puzzle at the dining room table, early in the morning, when she keeled over on the floor. Seventeen minutes later she was gone. She had a pulmonary embolism that, without any knowledge, started in the leg, got through the heart, and blocked both lungs. The lady that I am married to now, I met at a cocktail party a long time ago. She is British by birth, but she is an American citizen now. The first time we went out to dinner I said, "I'm never getting married again." I didn't want to go through anymore of that, but here I am, and I am very happy. Never say never!

Donald R. Lennon:

Thank you so much. I appreciate it.

[End of Interview]