| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #202 | |

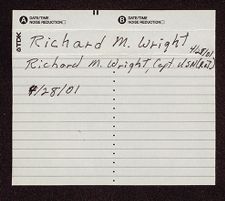

| Captain Richard M. Wright, USN(Ret) | |

| USNA Class of 1941 | |

| April 28, 2001 | |

| Interview # 1 | |

| Interview Conducted by Don Lennon |

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I was born in California and grew up in California until I left to go to the Naval Academy. I think the thing that inspired me to go to the Naval Academy was that when I was about ten years old my father took me on a Sunday down to Long Beach where the Fleet was anchored and was having a visitors' day. I got out on some battleship there at the age of ten and I saw all of those sailors. Every one of them was seven feet tall and blonde and brawny and handsome and the brass-work was bright and the paintwork was clean and the decks were holystoned. I made up my mind then that that was what I wanted to do with my life and I guess from that day on there was never anything that replaced that as my ambition. When I finished high school, I then went to what was called the Army West Point Preparatory School, because my brother had preceded me and gone to West Point. That was a school for enlisted men in preparation for those who wanted to enter West Point. My objective was Annapolis but the entrance exams and the competitive exams are rather similar. The one thing that was an exception was that for the Naval Academy it included

examinations in physics. My commanding officer at the West Point prep school allowed me to go one or two afternoons a week to a private school in San Francisco and study physics. So, I was prepared for that examination.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why had you gone to the Army's prep school rather than the Navy's prep school?

Richard M. Wright:

[note] The difference there was that in the Navy to go to the Naval Academy prep school you had to be in the Navy and if you failed to get into the Naval Academy you had to finish your tour, your term of enlistment in the Navy. For the Academy, you didn't have to be in the Army to take the exam. What most young fellows did was take the exam and if they passed it then they enlisted in the Army to go to the school. Even then at the end of that year--it was a yearlong course--if you failed to qualify and get into the Army [note], you didn't have to finish out a long term because you had only enlisted for the year of the school. There was a lot more flexibility. Given the chance to study physics on the side, I figured that was as good a preparation for Annapolis as it was for West Point. It turned out that I had an appointment for West Point also. I had the two of them. I chose the Naval Academy because that put me in line with my ambitions from childhood. That worked out fine, but I guess I expressed my interests in that sort of thing.

When I went into high school, I joined the high school ROTC and later on went to a military thing the Army runs called CMTC (Citizens' Military Training Corps), which

is a one-month thing each summer for people with the inclination to get into that. So, I had kept my aim pretty strongly for the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where in California were you?

Richard M. Wright:

Essentially, Los Angeles, but actually Hollywood. [note] I went to Fairfax High School, for any California or Los Angeles people that would make a difference to.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did your father do?

Richard M. Wright:

My father was a manufacturer. He owned a company in Los Angeles. I lived there my whole life until I joined the Army to go to that West Point prep school, which was in San Francisco. Also, I would say a little of the influence was my brother, who was two years older. I don't know what it was that led him toward West Point, but similar to my ambition as early as it was to go to the Naval Academy, he had a similar one to go to West Point. He was a real fine man and sort of a role model for me being two years older. We were both in Boy Scouts and he got to be an Eagle Scout, so I got to be an Eagle Scout. His devotion to go into West Point, I would say, influenced me a little bit in my ambition to go to the Naval Academy. That's about it for my youth.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you arrived at the Naval Academy?

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I was still in the Army when I arrived at the Naval Academy. They weren't going to let me out of one until they knew I was going to get into the other. I arrived at the Naval Academy in June of 1937. I took the physical exam, which you had to take just the day before you were sworn in, I think, and I passed that, so then I went up to Fort

Meade in Maryland and was discharged from the Army. Then I came back the next day and was sworn in as a Midshipman in the Navy. That was the mechanics of that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Once you entered the Academy, tell me something about your coursework or your relationships or your observations about life in the Academy.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I never had any doubts that I was in the right place. In other words, I never wondered if I made a bad step or not. I liked and enjoyed my four years there. I had, I suppose, the identical experience with all of my classmates. We got our tails beaten, did push-ups, went on cruise box races, and things like that during Plebe Year. I was not a gifted student. I would say I stood below the center of my class academically. But I worked hard and I managed to get by all right. As for special circumstances, I can't think of anything that would be different than any you would get from four hundred other guys.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you involved in any athletic programs or other extra-curricular activities?

Richard M. Wright:

I played Plebe football but I had an accident on the Youngster Cruise. That's the cruise that follows your first year. A mess table dropped out of its overhead rack and dropped on my head and put me in the sickbay for several days, and as a result of that I was prohibited from participating in bodily contact sports after that. That ended my football efforts. Other than that I didn't do anything significant. No, I was not a trackman or anything.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do much sailing?

Richard M. Wright:

Oh, I did that as everybody did. I dated and “dragged” a girl from New York City mostly. I suppose I attended most of the dances. Like I said, I wasn't a gifted student and I had to study pretty hard. When other guys were out playing lacrosse, I was

probably in my room studying and I suppose I passed a few nights after lights were out with a blanket over my desk lamp studying. I guess that was necessary.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your reaction to the type of instruction you received here?

Richard M. Wright:

I never had any reason to doubt that it was correct. I never challenged it in my mind. If they said it was the thing to study, I presumed that it was the thing to study. I never questioned the organization or the motives or the methods of the Naval Academy. It satisfied them and it satisfied me.

Donald R. Lennon:

Usually, you frequently hear extremes where some really love the way they taught or didn't teach and others thought there was almost no instruction involved. You just wrote, memorized and stood board.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I guess that would be very much an individual attitude on how one studied. I think I learned from all the courses I was taking. I never felt my time was being wasted intellectually. I read a lot of history. That was almost a hobby that had nothing to do with my academic courses. It was the main direction of my extra-curricular activity, I suppose.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any anecdotes, personal or otherwise, of the period? I know Joe Taussig always loves to talk about Uncle Beanie.

Richard M. Wright:

Oh, well everybody talked about Uncle Beanie [VAdm Harry Beam Jarrett, then Lieutenant]. He was a character. I wish we knew more about what happened to him afterwards. I have no idea. As we were riding around in a bus yesterday I heard somebody in the back of the bus say, “What would Uncle Beanie say about this?” I haven't thought of him for a long time but everybody knew Uncle Beanie. He was a real character. But, no I can't think of anything that's remarkable in that regard.

I suppose I was a very ordinary midshipman. I managed to be unsatisfactory at one point or another. I spent Christmas holiday in 1938 at the Naval Academy because I had an unsatisfactory grade in French at the time, but I pulled it up. I guess, speaking of academics, a certain exasperation occurred to me in that we have a classmate named Clarence Wright. Every week the grades appeared on the bulletin board and I would run out and see the name Wright. I would run over and would see 3.8. (4.0 was 100% perfect.) Well, that was always Clarence. Then I would go up a line and get my own thing, or down a line and get my own grade and it would be closer to 2.7. But, he was a star man and I was a drudge. We both got through. We both had our careers. The class standing didn't have too much to do with what you did afterwards.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've noticed that . . . really no relationship.

Richard M. Wright:

But I liked it; I liked every bit of it. There was never any question in my mind that I was in the right place for my life.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you graduated in February of 1941, you were assigned to battleships?

Richard M. Wright:

I was assigned to the TENNESSEE. The TENNESSEE was, of course, at Pearl Harbor along with seven other battleships. I had the good fortune that my ship was moored inboard of the WEST VIRGINIA and thus was not accessible to the Japanese torpedoes. The WEST VIRGINIA was hit by a number of torpedoes and sank alongside. The ARIZONA was the ship directly astern. My battle station during that attack on Pearl Harbor was as anti-aircraft battery officer. I was aboard ship. Actually, I was not an anti-aircraft battery officer. That guy was ashore and there was no other officer that was on deck. When I passed it on the way to my battle station, which was unimportant in the action, I just said to myself, “An officer is needed here and I guess I'm it.” The reason I

mention it is because that was the exposed spot from which one could see everything that was going on. It gave me a good observation point. I did see the ARIZONA blow up, and I did see the OKLAHOMA, which was next forward of us, capsize, and I did see the WEST VIRGINIA go down. It was a real good vantage point.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you up and dressed when it started?

Richard M. Wright:

No, I had got out of bed and was sitting there wondering whether I should get dressed and be about something or whether I should go back and go to bed again. This was a few minutes before eight o'clock, and the first thing that suggested the day was unusual was the sounding of the general alarm about seven fifty-five. My first reaction was, “This is a hell of a time for a drill. It is Sunday and we're supposed to not have drills on Sunday!” Anyway, about a minute after the general alarm sounded, I heard the explosion that indicated a bomb had hit and I thought 'This is no drill, this is the real thing.' I put on my trousers and jacket and ran, and it was when I was en route to what would have been my battle station under normal circumstances in the foretop that I saw an officer was needed on the anti-aircraft battery and stopped there.

Donald R. Lennon:

You really didn't have time to react other than to do . . . no time for shock, surprise?

Richard M. Wright:

You just did what seemed like the right thing to do. There was no time to analyze or to think about those dirty Japanese or anything like that. I would say that whereas we had no warning at all that this was going to happen, there was a general sense throughout the whole Fleet that a war with Japan was inevitable. That it would be on December seventh, that was just up for grabs, or that it would strike at Pearl Harbor. So we were surprised in that sense. I would say I wasn't at all surprised that it happened after I had

time to reflect on it a little bit. We knew it had to happen. I think the conduct of President Roosevelt reflected a determination in his mind that it had to be. He recognized that Japan was spreading out through eastern Asia, and I think he was determined to have a war. Even if the Japanese hadn't started it, he would have kept pushing them. So, whereas they were dishonorable in doing this without a declaration of war, I would say it wasn't uniquely their doing. I think that war was inevitable from one side or the other or both sides. It just happened the way it happened. I don't think we were surprised that we got into a war, but were surprised that we got hit that morning at that place in that way.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you able there on the anti-aircraft gun to hit any of the planes that were coming over?

Richard M. Wright:

We shot a lot and some planes came down. To say whose shot hit what airplane would be impossible. I presume we hit some. We think we hit some.

Donald R. Lennon:

No sense of panic?

Richard M. Wright:

No, I never saw any or even fear. I didn't see any fear in the eyes of any of our sailors. They were good men, did what they were trained to do. No there was no panic, no demonstrated fear, no awkwardness in performance. Everything was just fine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you all were blocked in after the attack actually ended. The TENNESSEE was blocked in by the WEST VIRGINIA.

Richard M. Wright:

We were. When the WEST VIRGINIA sank, we were moored, touching hulls, I guess. When she sank, it seemed to wedge us or drive us against the concrete pylons on Ford Island. If I remember correctly, and I'm not absolutely sure I recall things exactly, but I think the concrete piers against which we were moored, or to which we were tied actually, had to be dynamited to some extent to allow us to get free.

Donald R. Lennon:

They needed you out and operating as quickly as possible?

Richard M. Wright:

Yeah, well there were only three of us still useable out of the eight. The ARIZONA blew up, the WEST VIRGINIA was sunk, the OKLAHOMA had capsized, and the CALIFORNIA, which was three or four hundred yards ahead, sank in her berth. Oh, and the NEVADA, which was on the stern of the ARIZONA, got underway and was heading down the channel. I guess the captain figured he didn't want to take the chance of being sunk in the channel so he ran aground on what later would be called NEVADA Point, right opposite the hospital. So there were only three of the eight that were still navigable. By the time any damage we had was corrected to the point of going to sea and getting free from the mooring there, I think it was about two weeks. Could have been a little more or a little less than that. Anyway, the three of us, the PENNSYLVANIA, the MARYLAND, and the TENNESSEE sailed and went to San Francisco. Then, I think, I'm not sure, the PENNSYLVANIA remained in San Francisco and the MARYLAND and the TENNESSEE went up to Bremerton to have repairs made.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now the NEVADA did have damage to it?

Richard M. Wright:

I don't know that of my own knowledge. I don't remember having heard of her taking any hit at all. It could have been.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't Joe Taussig on the NEVADA?

Richard M. Wright:

I don't remember. It could have been the NEVADA, I don't know. At any rate, we went back to the West Coast and that was just to repair battle damage. We were in port there for a month or two. Then we came out. I mention this to you, because this is what led me to going into submarines, which was my major career in the Navy. After we got out of those repairs, the three battleships just sailed up and down, essentially between

Hawaii and the United States with now and then a run to the south of Hawaii. It was obvious we weren't going to be in the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't trying to engage any?

Richard M. Wright:

We were trying to avoid, I suppose, engagement and probably, tactically, that was the right thing to do. At any rate it looked like the war was going on and I wasn't going to be in it. Whereas nobody likes to have a war, if there's going to be one a professional wants to be in it. I applied for transfer to submarines. Unfortunately, I was in the Gunnery Department and the Gunnery Officer didn't want to change his organization at all. Each time I'd put in a request, he would forward it with a negative endorsement. Then he got transferred and I put in another request and got it. It was accepted and in early 1943, I went to Submarine School.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, nothing really took place on the TENNESSEE between Pearl Harbor and 1943 when you left?

Richard M. Wright:

It had nothing to do with the war. We were sailing around a lot but we sure never got anywhere near the war. I just wanted to be in the war.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was talking to someone yesterday who was on the MISSISSIPPI and his was basically the same thing, they just sailed around.

Richard M. Wright:

That's right. That division, the MISSISSIPPI and I don't remember the other two, wasn't at Pearl. They had gone to the Atlantic a few months earlier for something.

Donald R. Lennon:

They sent them back to the Pacific, but after they got there, they didn't do a thing but sail around.

Richard M. Wright:

That's right. Well, the battleship did play an important role when it came to bombarding islands that we were going to invade. But there was no such thing as a

battleship engagement to my knowledge ever. Even in 1945, there may have been one in the Philippines, but I don't think so. I think it was mostly just shore bombardment. It was an air war, an air war and a submarine war. I underline the point of that because of all Japanese shipping destroyed, the submarine force did more than half of it, and the force represented probably less than two or three percent of the total Navy. I think we, submarines, had a sort of a feeling of David and Goliath. We were the little guys with the slingshot and we were out to knock off the big ones in the Japanese Navy. There was a sense of accomplishment there.

Donald R. Lennon:

But weren't most American ships that were sunk, sunk by either Japanese or German submarines, torpedoed?

Richard M. Wright:

I would imagine the huge majority by German submarines. I don't think the Japanese submarines were all that. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what I was saying is the enemy's submarines were as effective to their war efforts as our submarines were to our war efforts.

Richard M. Wright:

With this exception. In the German campaign there wasn't anything, essentially, except submarines. They did have three battle cruisers. The BISMARCK, the TURPITZ battleship, and one other. But at any rate, the major part of the German Navy was composed of submarines and, of course, they did a lot of damage. In our case, the submarines, percentage wise, was a very tiny percent and yet we did more sinkings than everything else combined. So that's why we had that David and Goliath sense of accomplishment.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you left in 1943 to go to Submarine School?

Richard M. Wright:

I came out of that and my first ship was the POGY, which I joined in, I guess, September of 1943. The POGY has a story in connection with my thinking that is, in a sense, maybe we played a very decisive role in winning the Battle of Guadalcanal. What in the hell is the connection between submarines and Guadalcanal? One day on, my first, second, or third patrol that I made with the POGY, we were off the island of Palau. We saw at the pier two Japanese troop transport ships being loaded. How many troops they had aboard, I don't know. It could have been a division or two. At any rate, the water was shallow and near the island, but we laid off quite a few miles to the south. The next morning, when those two ships sailed and we were in deep water with them, we sank them both. Well, our reflection was that very possibly if that division of the Japanese Army had gotten to Guadalcanal maybe they would have won Guadalcanal instead of us. So, whereas nobody else in the world thought about it, we thought maybe we were heroes of Guadalcanal. That was our contribution there. It was a good ship and I made several successful war patrols with it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, tell us about the patrols. Other than the two troop ships, what did you accomplish?

Richard M. Wright:

Mostly it was picking off individual ships here and there. Not unlike almost all other submarine combat. I suppose one of the most exciting attacks that I was in was . . . well, let me go back an instant. One of the major advantages we had over the Japanese was that our radar was vastly better than their radar. We could be on a black night two thousand yards from them and we'd know they were there, but they wouldn't know we were there. They had radar but apparently it was ineffective. So one night, we had had daytime contact from a great distance with a group of six or seven Japanese ships plus an

escort of three destroyers. It became a dark night--there was no moon--and we sailed, on the surface inside the formation. We were halfway between their two columns. They had four ships in one column and three in the other, led by a destroyer with a destroyer on each quarter. We just sailed along with them there for half an hour to be sure we had a solution on their course and speed exact, when they would zig and when they would zag. At the right time, the captain fired eight torpedoes. Two at the lead right-hand column, two at the left-hand column, and two at each of the stern ships and he hit them all. Three of them sank immediately. One settled as though it was struck. The two trailing escorts each scattered. They weren't looking for us; they were looking to get out of there. The destroyer that was leading did a one hundred eighty degree turn and came charging back at us. When it was about fifteen hundred yards, I suppose maybe a little more than that, we fired what was called a down-the-throat shot, bow to bow, and hit her. She exploded and that was the end of that, and we sailed merrily on our way.

Donald R. Lennon:

You wiped them out!

Richard M. Wright:

We wiped them out. And boy that really felt good. That was one of the best patrols of my career.

Donald R. Lennon:

Expended all of your torpedoes there in one. . . .

Richard M. Wright:

Yeah, well darn near at least we. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, didn't they have sonar?

Richard M. Wright:

Oh they had sonar, but this is on the surface. This was totally on the surface. People always think in terms of submerged submarines, and its natural that they would, because of course today its totally submerged. But in those days a submarine had to surface every night to recharge its battery and replenish its air. Because our radar was

good and their radar was poor, we much preferred a black night without moonlight to do the whole thing on surface. Because our speed almost going downhill was seventeen knots, maybe eighteen knots, was faster than their merchant ships, we could close in on them when we wanted to and needed to. Also on the surface you had the opportunity and took advantage of it that after you had fired and destroyed your target you could sail away free on the surface and not get depth charged by the escorts. When you made a daytime attack, a submerged attack, you always got depth charged from them. I can count the depth charges as easily as I can count the sinkings, so we preferred to do it on the surface.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was your captain?

Richard M. Wright:

On that particular patrol it was Ralph Metcalf. He was a red-hot skipper. He was a very, very good skipper. High morale in the crew, they always had confidence in him.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just taking out that many ships they would have . . . someone had to be on top of it.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, yeah that's right. But that was only one example. He laid them on good. The POGY had a pretty hot record. Ralph Metcalf was also skipper at the time of the Palau incident that I mentioned where we helped win the Battle of Guadalcanal.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other special patrol or sinking?

Richard M. Wright:

No I don't remember anything. Mostly, it was just one or two isolated ships at a time.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned the depth charging when you attacked submerged. Any of those cause alarm?

Richard M. Wright:

Well, alarming, but never dangerous enough for us to think we weren't going to get home. The one thing though that did affect our patrol, as a matter of fact, after that sinking of the two transport ships at Palau we did take a rather severe depth charging. We had the misfortune that our torpedoes' gyroscope spindles were still engaged on the torpedoes that were not fired and the depth charging bent those spindles so that we couldn't extract them. In other words we weren't able to shoot any more torpedoes.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were live?

Richard M. Wright:

They were live torpedoes. Well, all torpedoes are live.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I meant they had the mechanisms ready.

Richard M. Wright:

Oh, they were ready to fire. Ready to fire and the spindles were engaged and they got bent by the depth charging so we couldn't use the torpedoe gyro spindles. We couldn't take them out of the tube. We couldn't fire them out into the water so we had to go home. That was the end of our patrol just because of the bent torpedoes. But, that was the only time of that. We had had damage; broken valves and water spurting around and things like that, but not like some of the submarines, which had terribly severe damage. Pretty damn close at times though. We thought we were in trouble but fortunately it never got that bad.

Then after the POGY I was transferred to the PARCHE. I made one patrol there. Nothing special . . . well it was a little special. We went all the way into the harbor at, I guess the city's name was Naha, in Okinawa, and found deep in the harbor--some miles we had to penetrate--a whale factory. And that was just about as big a ship as they built at that time. It wasn't like an oil tanker or anything but it was something in the neighborhood of twenty thousand tons. It was at the pier, or the wharf, and we went in

and sank that. The interesting part is that the Japanese all must have thought they had been hit by bombs from an airplane because all around us we saw anti-aircraft batteries going into action shooting up into the sky. There was no airplane there. They didn't pay any attention to us at all. We never got a depth charge. It was daytime. No destroyer came hunting for us. They devoted themselves strictly to shooting up into the air.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, what was the whale-ship being used for? Did you have any idea? Obviously, they weren't out there on a fishing expedition.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I don't know. Maybe they were still doing whaling, I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

I would have thought all of their war efforts would have been concentrated. . . .

Richard M. Wright:

Well, maybe they needed whale oil. Maybe it was food. I don't know. Do they eat whales or not? It never occurred to me to think about that. But that was a whale factory. There was no question about that and it was big. And, we were real delighted to sink that.

The next thing, there was a submarine out in Guam getting ready for special patrol when their exec had to be relieved, so I was detached from the PARCHE and sent to the SPADEFISH. I joined her in I think it was April of 1945. That was a very special patrol for this reason. Very shortly after the war had ended in Europe, we sent a patrol, or a submarine, into the Sea of Japan. They had a patrol there. The Japanese had laid very, very thick mine fields across the Tsushima Strait and also across the exit up at the north end . . . at La Perouse Strait. Extremely heavy. Because of that no submarines had been sent into the Sea of Japan. Well, that went on for three years and the Japanese sailed across that as though it was their private lake, which indeed it was. In the spring of 1945, a special sonar was developed that detected mines. That sonar was put on nine

selected submarines, which assembled at Guam in the first part of June of 1945. It was given a group name: “Hydeman's Hell Cats,” I think it was. At any rate, we sailed in three successive days of groups of three each. That's nine boats. We entered the Sea of Japan with our mine-detecting sonar. The SPADEFISH was in the first day. We were under orders not to fire anything until all nine had gotten inside the Sea of Japan and each one of the nine had time to reach a major port of significance. When we were all in position, all nine at the same time, we were allowed to start firing at sunset on that day. The toll on the Japanese was staggering to them, because all of us got something. I think the SPADEFISH sank three ships that first evening. Of the nine, eight came out. I'm not sure which ship was lost. It might have been the BONEFISH. But eight came out. We came out on the surface through the Tsushima Strait . . . no, through the La Perouse Strait four weeks later, having sunk an enormous number of Japanese ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

You spent that length of time in there?

Richard M. Wright:

Oh yes. They didn't have much anti-submarine warfare capacity left. See this is June of 1945 and they had been pretty well wiped off the sea. After that, from that time on and even a little before that, almost all of the submarine effort had, and I don't like to us the word degenerated, but it had gone down to being used mostly as a plane guard. We were picking up aviators that were lost in raids on Japan. So, that was a big patrol of the war--the last big patrol--and I felt lucky to have been in on that. My captain on that was a guy named Germerhausen. He, to me, was one of the best Naval officers with whom I have ever served. He was a great guy.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were they using that took out the BONEFISH?

Richard M. Wright:

She was lost from enemy action. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it aircraft or submarine?

Richard M. Wright:

Probably not, but I don't remember the details. I probably have heard but mind you that was fifty years ago.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you all just sailed out unscathed without taking fire from. . . .

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I don't know about the other ships. We didn't have any action by Japanese ships against us. One thing that was interesting, I guess, you could almost say that we sank the first Russian out of the Cold War. One night we detected a ship coming through our area and there was an agreement that the Russians, if going through the Sea of Japan, would be always on a particular course with their lights on and not zigzagging. Well this ship had its lights off, it wasn't on the right course, and it was zigzagging. We assumed it wasn't Russian and we sank it. It was a big one, too.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it a transport ship?

Richard M. Wright:

I have no way of knowing because it was at night. We got in as close as we could to it thinking there wouldn't be any Japanese shipping, certainly not that big in that area. We were hoping to see it before firing a torpedo but it was a black night and we couldn't see it. Finally, the captain had to make a decision to shoot it or not, and he shot it. A couple of days later there was a message to everybody saying, “Does anybody know anything about the Russian ship such-and-such?” They gave the latitude and longitude. We sent back a message saying, “We don't know anything about that ship but we sank a ship at that point at that time. Well, fortunately COMSUBPAC took a generous attitude about it and didn't reprimand the skipper at all.

Donald R. Lennon:

Why would they do that and not follow the agreement?

Richard M. Wright:

I guess they didn't have confidence that we would follow the agreement. Or maybe they thought they were defending themselves against Japanese submarines. I don't know. But they weren't doing what they were supposed to do to insure us that they weren't, Japanese so we sank them. She was a big one. I think if I remember the record, she was one of the biggest ships in the Russian Navy. Afterwards we felt that was the first ship of the next war. We didn't worry about it much. We all knew that we were going to have trouble with Russia later. Anyway, that was that.

We came back from that and got back to Pearl in July, and the war was over in August. So that was my wartime submarine career. After that we came back in September to Mare Island, California, and put the ship out of commission. My captain got transferred to be governor of Fuji or something down in those islands. That left me as commanding officer, which delighted me: But it was short lived because we were putting the ship out of commission. Most of the ships went into mothballs. We put it out of commission and then I went down to San Diego and became executive officer of the BLOWER. That lasted for a year or a little more. Then I guess in 1947 I went to the University of Southern California to be in the ROTC program. I had two good years there. I enjoyed very much the business of instructing and teaching.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any you were back home?

Richard M. Wright:

Oh, yes, I was in Los Angeles. That's right. Well, that's why I had put down my choice of schools if I were to go to ROTC as being Southern California. That was good. One of the things I enjoyed in retrospect was that years after, I would meet officers who had been my students. The thing that pleased me most was several of them said, “You know, it's been just like you said it would be.” And that made me feel good.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the ROTC programs, after the war was over, as vital as they would have been during a time when war was building up? In about 1947 you really weren't certain you were going to be in a war in Korea.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I don't know. It always gave me a good feeling that the students said, “It was just like you said it would be,” because in my mind, the Navy was marvelous for people who love it. But it could be a miserable thing for people who didn't like it. I never endorsed the idea of persuading people to be in the Navy. And that extended even to a measure of, well, I won't use the word disobedience because I never thought myself disobedient, but when I was in after the war commanding one ship or another, we were constantly getting letters from the Bureau of Personnel urging us to push re-enlistment. Push re-enlistment; get that sailor and get him to re-enlist. I declined to do it. I just wouldn't do it. My theory was if a man didn't have an enthusiasm for it enough to make him want of his on volition to be in the Navy then I just damn well didn't want him to be in the Navy. So I never subscribed to the Bureau's pressure on that. That's the same philosophy that made me pleased to have the ex-students say what they did. I enjoyed the ROTC term. It was a good learning period for me as well as for the midshipmen.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was good to have some shore duty after being at sea.

Richard M. Wright:

That's right. I had two years there and that was nice. Then that led to another assignment that was noteworthy. In July of 1949, I was ordered as executive officer to the USS COCHINO, a submarine at New London. We sailed about three or four weeks after I joined the ship. With two or three other submarines we went for a training and research mission in the Barents Sea. The Barents Sea is north of Norway and Siberia. Our Murmansk convoys during the war had gone through there to get to Murmansk. An

ostensible reason for that trip--wouldn't have been a reason all by itself, but in a sense a reason--was to test some new equipment that was being made available for submarines to see how it would work in those waters. I'm trying to think of the exact date. I think it was August twenty-fifth, but I could be off by a day or two.

There was a defective switch in the after battery compartment of the COCHINO and there was a spark. Let me put this together for you right. We were snorkeling and when you snorkel it means you have a very small part of the ship about the size of a fire hydrant above the surface of the water. It's got a valve that opens so you can take surface air down into the ship even though it's at a depth of perhaps fifty-some feet. Well, in a rough sea, that snorkel valve is going to be inundated by a passing wave or swell, and when that happens the head valve closes for a moment. Until it opens again, the diesel engines are running with air taken from inside the boat instead of air coming down through the snorkel tube. Because of that, generally, you draw a certain amount of suction throughout the whole boat. Your air pressure is less than normal. You even have an altimeter aboard to show you at what elevation you are submerged. It's a play on words. It is what elevation an airplane would be to have the same altimeter reading if it were in the airplane instead of in the submarine.

Well, we were drawing a rather high vacuum because it was a rough sea and the snorkel valve was often closed. It wouldn't have been dangerous except that we had . . . I've got to get back to the physics of the thing again. When you have a vacuum in the boat, even a slight one, the bubbles of hydrogen that form on the battery plates expand as the pressure on the surface of the battery water is diminished. The pressure inside the water is diminished and the hydrogen bubbles expand and break loose and float to the

surface, giving a concentration of hydrogen inside the boat. Well, in our case that level of hydrogen had gotten high enough that when the defective switch arced it exploded the hydrogen. So we had a hydrogen explosion when we were sixty-feet deep, and a resultant fire.

The fire was in the after battery room and that's one of the crew compartments, totally given to living, lockers, bedding, etc. So, there was plenty of material for a fire to live on. We immediately came to the surface and we fought the fire for several hours but were unable to put it out. The forward battery discharged into the after battery because they were connected as they normally are. When the explosion occurred in the after battery, it discharged the battery somewhat so the forward battery was charging the after battery and continuing to generate more hydrogen. So it was just impossible to put the fire out.

At any rate, I did try to go into that compartment and open a battery disconnect switch, which would have terminated the generation of hydrogen. But just as I got inside of the compartment, there was another explosion and it blew me out of the battery room and burned all or most of the clothes off of me. I was sitting on the deck of the after engine room. The atmosphere had caused the engine to run at an excessive speed, and that had caused a rupture of some of the fuel lines. We had a bath of fuel on the deck of the forward engine room that caught on fire and that added to burns that I had from the explosion. I did get up and walk to the next bulkhead, which was between the two engine rooms, and there was a group of guys waiting for me. They had a line around me and, I guess, were helping pull me along. They took me back to the after torpedo room. Unfortunately, all of our medication was in the after battery room because that's where

the medical locker was. There was no medicine aboard, no morphine, which was unfortunate.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you had third degree burns on part of you?

Richard M. Wright:

Yeah, I was pretty badly burned. But there was no morphine and no sterile ointment of any sort. Unfortunately, the torpedo-men--there was no hospital-man there--knowing that they should put grease on me, put torpedo grease on me. Well, that's not known for being antiseptic, so in addition to the burns, they saw to it that I was thoroughly contaminated with torpedo grease. At any rate, I spent the next fifteen months in the hospital.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did that do more harm than good, the torpedo grease?

Richard M. Wright:

Probably. Yes, I have to say that it did, because the reason I spent so long in the hospital was that the grafting wouldn't take because my skin was so infected, so impregnated with that. I don't know the consequence of it having been left undressed, but at any rate the grease did keep the grafting from taking and there were many months that they spent trying to get the skin clean.

Donald R. Lennon:

I'm amazed that you weren't in total shock because of the pain.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I probably was. I probably was in shock some of the time. This was early in the day. The explosion was around eight in the morning. Probably my episode was before nine o'clock because our first thing would be. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

I know you all escaped to a sister submarine that was there.

Richard M. Wright:

I'll tell you about that. At any rate all of our communication was lost. The submarine that we had been working with was one of the others of the group, but just the two of us were in that vicinity together. She got close enough that I guess . . . well from

here on I'm using just hearsay, because I'm down in the battery compartment, probably in shock as you said. Not the battery compartment, the after torpedo room.

At any rate the COCHINO managed to attract the attention of the TUSK. The TUSK, finding no ability to communicate by radio, came close enough to do signal flags. But the captain of the COCHINO wanted to send a boat over to the TUSK to tell the squadron, or the unit commander who was in the TUSK, what the situation was. I don't know whether it was our rubber boat or whether it was a TUSK rubber boat that was pulled over with a heaving line, but two men, one officer and one civilian sonar expert who was aboard (it might have been radio) got in the rubber boat and were hauled across to the TUSK. Unfortunately, just after they had been brought aboard a big wave came over and it wiped off all of the people who had been on the bow. There were probably about fifteen people in the water with the exception of one of the two people we sent over. So we had all these guys in the water. One of them was our guy and about fifteen TUSK guys. The next half hour was spent by the TUSK trying to recover its men. It got back half of them. I think six or seven died. Our guy the, civilian, died. They all drowned--six or seven of them--I'm not exactly sure. So that was the end of that.

I don't remember at what stage of the game it was, but in the late afternoon, probably ten hours or more after the initial explosion, the ship was settling and the captain realized that it would have to be abandoned. All of the people who had been forward of the after battery compartment early in the game had to go up to the topside because the compartment was contaminated with gas--hydrogen. So they were up there exposed to the weather for quite a few hours. The captain decided the ship was sinking and asked for the TUSK to come alongside and take off our crew. They came along,

portside to portside, bow-to-bow, and they or we (I don't know, I was still in the after torpedo room) rigged a plank across. You couldn't make its fast because the ships surged. All of our people were up on the bow waiting to cross, but nobody seemed to want to go because that plank looked pretty damn unsubstantial and untenable really.

About that time was the time the captain sent word down to get Mr. Wright up there. There was one pharmacist's mate, chief pharmacist's mate, who stayed down in the compartment with me. The other guys hadn't wanted to go. They had said, “If you are going to stay we are going to stay,” but I ordered them to go up and leave me with Eason. They did. Finally the captain said, “Get the hell up here,” so I got out of my bunk with a little help from Eason pushing, I guess, and I got up the ladder.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were able to walk? That's one thing I was wondering how you got over to the TUSK.

Richard M. Wright:

I don't know how I got over there. I just almost have a sense of levitating up that ladder. Couldn't have been. I'm not a very religious person. I don't believe God reached his hand down and pulled me up, but I did get up there. The body, I suppose, responds in self-defense to something. My muscles were enough to get me up. And as I say, probably, Eason, the hospital man, was pushing on me too. But I got up there to the bow of the ship and, hell, nobody was crossing that plank. I figured what the hell, we might as well. I guess they were afraid of falling in between the two hulls, which was a real danger because the plank wasn't made fast and was only about twelve inches wide. But I thought, Christ, we might as well fall in the sea as go down with the ship, so I crossed.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you actually walked across the plank.

Richard M. Wright:

I walked across that plank. I was the first one to walk across the plank. After I went the rest of the guys followed me.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had they wrapped you in blankets? You said you clothes were primarily burned off. I'm sure in the Barents Sea it was awfully cold.

Richard M. Wright:

No. When they were told we would have to go topside they found a pair of dungaree trousers for me.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were able to put them on? Your skin wasn't in such bad shape?

Richard M. Wright:

They pulled them up. It was pretty bad. I guess it was pretty well torn off. They got them on and I got across that way and then we all got across. And Benny Benitez, the captain, was the last to leave, in the good tradition of the sea. I don't think he was over to the TUSK more than two minutes when the COCHINO sank; it was that close. I was put to bed in the room of the captain of the TUSK and we sailed into a little town in the north of Norway, Hammerfest, the most northerly town in the world. They got the doctor of this place and he came and sat down beside me and said, “Well, how are we today?” as he cordially slapped my arm with half of the skin burned off. Oh, Jesus, I made a new hole in the overhead! Can you imagine a doctor doing that? “How are we today?” with a slap on my burned arm.

Donald R. Lennon:

Obviously, he hadn't treated burns before.

Richard M. Wright:

They had him off of that ship in about three minutes and we got underway. All of my crew as well as the TUSK crew were aboard. We went down to the city of Tromso, which was a proper town. They had a hospital. They got me off and put me in a hospital and I stayed there about five days, I suppose, gathering some strength to be flown down to London, where they had a proper little medical facility. It was not a hospital but the

headquarters had a little unit, a ward, with half a dozen beds. They kept me there for about a week and then I was flown back to some airport in Massachusetts and then driven down to New London and put in a medical facility in New London for another week, I suppose. One nice thing, they brought my wife along in the airplane that came up to Massachusetts to meet the plane that I came in on from England. So she was there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you needed a major burn center, I would think, for your treatment.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, we hear about burn centers now. I don't know if in those days they really had a burn center. But they sent me after a week in New London up to the naval hospital at Newport, Rhode Island, where we have a naval station. So I spent the next year there. But it all came out all right. I was dedicated. I really wanted to get well and get back to work, and I did.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now you received the Purple Heart for that?

Richard M. Wright:

No. The Purple Heart is only for wounds in enemy action. No, I never had a Purple Heart. There were damn few Purple Hearts in submarines.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I declare, the alumni register listed you as . . . I must have misread it.

Richard M. Wright:

No, I got a Navy and Marine Corps medal, but no Purple Heart. The Purple Heart is only for combat.

Donald R. Lennon:

How was the COCHINO?

Richard M. Wright:

The COCHINO was pretty new at that time. It was built as a snorkel boat. I don't know if the COCHINO had any war patrols or not. I rather doubt it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there something defective? What caused the pressure?

Richard M. Wright:

Oh, you mean what was wrong with it? There was a defective switch. Even submerged we were rolling some and, naturally, there was no way to reconstruct it after it

sank to the bottom of the ocean. What was wrong with the switch? I don't know, but it must have fallen open. Just how that happened I can't reconstruct, but it drew a spark. The spark was heavy enough, given that we had a high concentration of hydrogen from the fact that we were snorkeling in a rough sea, to cause the explosion.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was one of those freak accidents.

Richard M. Wright:

It was freak enough. That's right. Unfortunately, the effort to contain it was blocked by the episode of another explosion just as I went inside. If only I had had another fifteen seconds. I was within two feet of the switch and I had a tool to open that switch, the connect switch with the forward battery. If I had had time to open that thing, it would have never continued to explode. Whether the damage was already bad enough, I don't know, but I doubt it. It was early in the game and we continued to have explosions for a long time after that.

Then I went to what was called post-graduate course. It only lasted two or three weeks in New London for prospective commanding officers. Then I commanded the submarine SCABBARDFISH, home ported at Hawaii--Pearl Harbor--for about two years. I can't think of anything particularly remarkable that we did. From there, that would have been 1952, I went to the Bureau of Naval Personnel for about two and a half years. I was in the Naval Reserve Division there.

Then I decided that instead of being strictly a submarine sailor I wanted to expand, broaden my knowledge of the Navy, so I asked to be given a destroyer command and I got it. When I left the SCABBARDFISH, I went to BUPERS until 1955 and then I went back to the Pacific Fleet and had command of the destroyer, KNAPP, from 1955 until 1956. Then the KNAPP was put in the program for being decommissioned--

mothballed--and I made the point to BUPERS that I hadn't had as much as a full year. Actually, I was a half-month short of a year. I said I really didn't have a proper tour as commanding officer of the destroyer so would they give me another. They did and I got command of the SHIELDS and had that until 1957 when I went as the ASW [Antisubmarine Warfare] officer to staff of Commander First Fleet, which was based in Coronado. Actually, the headquarters was in the naval air station at North Island. I had that for about two or a little over two years.

Then in 1959, I suppose, I went back into submarines and was Commander Submarine Division 51, I think, based in San Diego. There again I can't think there was anything remarkable or unusual about that tour of duty. Very enjoyable, I enjoyed it a lot, until, June of 1961, when I got orders to go to Holland as Naval Attaché. I had a good three months in Washington in preparing for that, studying the Dutch language. Then I went to Holland and took over as Naval Attaché in 1961. I was there until September of 1964. That was a delightful tour. (You could almost turn off the machine to say this.) Part of the fun was there was a lot of real good partying and social activity. Of course, you worked at the social activity.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was part of the duty wasn't it? Public relations.

Richard M. Wright:

That was part of the duty but it was sure a nice part. Yes, actually it was a diplomatic role. The primary role of course is you are the representative of the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Navy to the Commander in Chief of the Dutch Navy. But then you also have an intelligence role. Your boss, really, is Director of Naval Intelligence and that was Admiral Lorrance. I had known him well before in submarine activity because he was a submariner. That was a lot of fun. My wife loved it. And I

made a lot of good friends and continue to go to Holland every year for a couple of weeks and see my friends that I had in those days. Of course they are getting few and far between now, all of us are.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the sixties, what kind of Naval Intelligence were you trying to commune?

Richard M. Wright:

Well, interestingly enough, I was interested in anything that would be of use to our country. That was about the time, however, that Suharto was giving a bad time to the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies. So we wanted all the information of the naval activity of the Dutch Navy and what they were doing down there. As an indication of how good our relations were with the Dutch Navy, I can remember one or two instances--more than that two or three--when the director of Dutch Naval Intelligence would call me at home, two o'clock in the morning, and say, “Dick, we've got dispatches in from Indonesia, do you want to come down and read them with me?”

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking they probably briefed you on what was going on rather than you having to do it surreptitiously.

Richard M. Wright:

That's right. He invited me to go down and read the dispatches with him. You can't get it any better than that. So that was real good. And I went to sea sometimes with the Dutch ships and observed them. They were nice ships. I enjoyed that. Where were we?

Donald R. Lennon:

We were at The Hague and you were being briefed by the Dutch on the situation in Indonesia.

Richard M. Wright:

The relations with them were always good. As a matter a fact, I became good enough friends with the Chief of Naval Operations so to speak of the Netherlands. He and his wife and I and my wife used to go weekending together. Between that and the

Director of Naval Intelligence, we were really locked as tight as you need to be. It was a marvelous duty station. Oh, I loved those three years. Those parties were elegant and nice.

My good friend, the chief of the Dutch Navy, that's what he was, called me into his office. Even though we were good friends, he wasn't friendly on that call. He said, “I understand you have been talking to so-and-so.” He said, “If you want to know about things, come and ask me. I'll see you get the information, but please don't go ferreting out.” So that was his reproach. It was very mild. It was only a slap on the wrist, but he told me, “Don't go snooping around. If you want to know something ask us and we'll tell you.” But that's the closest I ever came to having been burned. But we had good relations with the Dutch. They are fine, fine people and they are very honest, good to deal with. But I can't think of anything, other than things like that.

At any rate, in September of 1964 I came back to the States and had command of a troop transport, the MONROVIA. Nothing remarkable about that. Well, I guess a little bit. We had some employment in that it was the period when there was some sort of civil war, well I wouldn't call it a civil war, but there was some action in the Dominican Republic. Do you remember that?

Donald R. Lennon:

I do.

Richard M. Wright:

Yeah, and we carried troops down there, Marines. That was the only thing that could have been called an action activity. From that, I went to command of Submarine Squadron 2 in New London and I had that for a year. In September of 1966 I went to Washington for duty on the staff of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. That was my last. I was in

the planning division there. It was interesting but I felt that I had already left the Navy. I didn't feel Navy anymore. But that's my career.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you retired in?

Richard M. Wright:

I retired in August, on the thirty-first, 1969. I had a civilian job for three years. Then I had the misfortune of losing my wife in January of 1973. My children were both grown and out of the nest and didn't need any support from me, so I quit my civilian job and became a vagabond.

Donald R. Lennon:

I tell you, you have quite a reputation as a vagabond. I was reading all the places you have been and it's just incredible.

Richard M. Wright:

Well, I thought if just possibly the subject came up I'd show you a map that I've got of my vagabond adventures.

Donald R. Lennon:

Captain Delano sent us the account of your train trip. It's absolutely amazing all the places you have traveled, down the Mississippi from the headwaters. And you traveled primarily by yourself?

Richard M. Wright:

Well, mostly. I have had company with me on some trips.

Donald R. Lennon:

Have you ever felt in danger anywhere? Even going across the Soviet Union? It was still the Soviet Union in 1983.

Richard M. Wright:

Never felt threatened. Not one single time in my whole vagabond career. Yes, it was when I got there in 1983, I think.

Donald R. Lennon:

Across China in 1987.

Richard M. Wright:

This was all by motor home down here and up here. This trip I started in Ireland and went all the way to India and back by motor home. This one was a motor home trip.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you didn't keep diaries of all this?

Richard M. Wright:

I wrote long letters to my kids.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know that. I read a letter that your son passed down to Captain Delano of your train trip all the way from, where was it to?

Richard M. Wright:

I made the longest train trip in the world. I started in Lisbon. I was here actually, in Holland, but I thought, Why not make it the longest? So I went down to Lisbon and got on a train there and went all the way to here, Nakhodka, Siberia, by train, then by ship to here, Yokohoma, and flew home. Then to make it all the way around the world, I got on a train here, Seattle, and came across back here, New York. So except for the Atlantic and Pacific I went all the way around the world by train.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's wonderful.

[End of Interview]