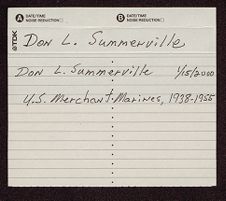

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #180 | |

| Donald R. Summerville | |

| Merchant Marines | |

| January 15, 2000 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Please begin with your background.

Donald R. Summerville:

I was born on July 30, 1920, near Richmond, Virginia, in a little town called Varina. I lived in Richmond for two or three years until my father and mother moved us to New Jersey and then to Charlotte, North Carolina, which is my father's hometown. We lived there until the beginning of the Depression. At that time, my father owned two homes, and he lost both of them. We moved to Richmond, Virginia, to live with my grandparents. They had a very small, two-bedroom house and all of us, a family of five, could not live there. Consequently, my aunt in Peoria, Illinois, asked my mother if I could move in with them. I lived in Peoria for about two years and then came back to Richmond, Virginia, in 1933. I graduated from high school in midterm in 1938. I went back to Peoria because my cousin was working for Caterpillar Tractor and he said that he could get me a job. I went there, but there were no jobs, so I hitchhiked back to Norfolk, Virginia. I don't remember where I was working, but while I was there I met a seaman. He suggested that I get my seaman's papers and ship out. I remember the day that I got my seaman's papers--it was April 18, 1938. I went down to the seaman's hall after I got my papers.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you go about getting papers then?

Donald R. Summerville:

You had to apply at the Coast Guard. They took a blood sample to see if I had any venereal diseases, and they gave me a paper that allowed me to work the lowest class duties aboard ship--washing dishes, serving tables, etc.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you did not have to take any exams or undergo any training?

Donald R. Summerville:

No. Then, after I got my papers, I went to the hiring hall and got a job on a coal collier. I was a coal passer. It was in harbor, and I worked two nights as a coal passer. I knew that was not my business, because with hauling coal up to the fireman and then shoveling it from the coal bin, I was constantly covered in black dust.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you haul it in buckets?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, it was a two-wheel wheelbarrow. It had about three quarters of a yard of coal and you dumped it into a pan where the fireman would shovel it into the boiler. I quit and went back to the hall. Three or four days later, I got a job on a fruit ship with the United Fruit Company. That was a combination passenger ship and cargo carrier. We left from Norfolk and went down to--I think that they called it British Columbia at that time. I think it is called Belize now. We got a load of bananas there and took it back up to Mobile, Alabama. In those days during the Depression, when you came in on a ship, if the ship did not have a ready cargo for you, the captain or the company would dismiss you, lay you off, except for the firemen and some essential workers aboard ship. I was laid off. I caught another ship that was loaded with vegetables and all kinds of stuff.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were these refrigerated ships?

Donald R. Summerville:

No.

Donald R. Lennon:

They didn't have them back in those days?

Donald R. Summerville:

No. For the United Fruit Company, for example, the bananas were picked as green as grass and kept in big bunches. They were brought in big boxes. They put these huge boxes in the hulls of the ship. So, I was in Mobile, Alabama, and a few weeks later I got another job on a ship as a steward, making up beds and things. I did not like that one bit.

Donald R. Lennon:

What sort of pay were you getting?

Donald R. Summerville:

If I am not mistaken, we would get seventeen fifty or nineteen fifty a month, I have forgotten which. That was big money because you would be gone for two months and come back with thirty or forty dollars.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had never been on a ship until you were on that coal collier?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes, that was the first ship I had been on in my life.

Anyway, we got back to New Orleans where I had a layover on shore for a couple of months. To pick up money, I would get jobs washing dishes or something like that. After a while, I got a passenger ship job with the Delta Line. I was in the engine room. I got a job as a wiper. A wiper's job was just cleaning up, doing various kinds of work that they could find for you. But I liked working in the engine room. We made a trip to Brazil and back up to some of the islands, to Havana, and then back to New Orleans. I stayed with them for two or three trips until they laid me off.

Shipping was not worth two cents in New Orleans, so I started hitchhiking to New York. Someone told me about Houston. During the fall of the year, Houston gets a lot of grain. So, I went down to Houston. I waited in Houston for a long time until I got a job at a feed mill. The man asked me if I had ever worked on a farm. I said yes. He asked me if I knew anything about chickens. I said, "Yes, I was raised on a chicken farm." So he took me up to Tomball, Texas. I worked there for about a year. In 1939 or 1940, I quit and

decided to go back to sea because working in the feed mill was not exciting. So, I was going to hitchhike up to New York, which is an active port. There had been a maritime strike, and the Maritime Union had taken over. It was hard to find a ship not with the union. So, when I got to Richmond I visited my parents for a while and then went down to Norfolk to get my union papers. I joined the union and waited for a long time to try to get a ship. I decided to hitchhike up to Baltimore, Maryland, to try to get a ship. I got a pretty good job at Westinghouse. I stayed with them for about a year. I was still going down to the union hall back and forth and registering. A job came open, and I got on the ship. Meanwhile, when you are a wiper, after a certain length of time, you can apply for papers for a higher position. I worked my way up to water tender and then up to deck engineer.

Donald R. Lennon:

These are all coal burning ships?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, I only worked on one coal burning ship, the first one. Anyway, a ship job came open on the Liberty GLOW, an old Hog Island ship, made in Belfast, Ireland, in 1913. It was a riveted ship and much easier in the water than a welded ship because it gave. You could hear it creaking all the time. We went to England where they had that lend-lease business and a lot of lend-lease was going over to England in the early forties. As we were crossing the ocean, we got a message that the REUBEN JAMES had been sunk. We were to look for any survivors. I think it had been sunk a couple of weeks before hand. We wound up in Liverpool, England. During that time, a lot of bombing was going on. Right across the harbor from Liverpool was Manchester, England, if I am not mistaken. We were anchored in the harbor one night when they were bombing and some bombs fell in Manchester. Then we went somewhere south of London. I don't remember the name of the

port; I think that it might have been Hull(?). We unloaded some supplies there and came on home.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was hazardous duty at that time. The Germans were taking out merchant ships, weren't they?

Donald R. Summerville:

Not at that time, not American merchant ships. A few were hit. This was in 1940. I came back and then, in the middle of 1941, I got on another ship, a coastline ship that went from Philadelphia to Boston to Bermuda to Norfolk.

Donald R. Lennon:

A passenger ship?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, it was a cargo ship. Then we came back to Norfolk, and I went home and stayed a few months. Then in the middle of 1941, I got on another ship and went to England. We made a quick turn around and started back to the States. When we were in about the middle of the Atlantic, we received a notice that Pearl Harbor had been bombed. We had to close all portholes and turn off all our running lights.

We arrived back in Boston about the middle of December. The ship came down through the Delaware Canal to Baltimore. I got off the ship on December 28. I went to the Baltimore recruiting station to join the Navy. I passed my physical and everything and I was sitting there thinking. I decided to try to get some stripes because I had been to sea before. I talked to some Navy boy there, a seaman, and he told me to go and see Lieutenant so and so. So, I went to see this lieutenant and talked to him for about ten minutes. He said, "As much as we would like to have you in the Navy, the Navy training yards are completely full in Norfolk and the Great Lakes." He said that the Merchant Marines needed me more than they did because all the older men in the Merchant Marines had gotten off and gone to work in the shipyards and ships were laying loaded with no crew in Baltimore.

So I did that, and I got on an old ship--I don't remember what type it was--but it was loaded and was going down the Atlantic Coast to Aruba. When it left the shipyard, they put an old wooden gun on the back of the ship. You could rotate it around; it looked like a big five-inch gun. I was fireman on that ship. The ship had three boilers. The gauge on the middle boiler was about five to ten pounds off from the other two boilers, which were correct. We got to Aruba, went to one of the other islands, and came back from Nuevitas, Cuba, loaded up with sugar. Then we went on to Hamilton, Bermuda. In Cuba, we had picked up a bunch of Cubans to work at the Navy base that had been started in Hamilton, Bermuda.

We went on up the coast and just as we passed the tip of Florida, a big Gulf tanker passed us. Gulf tankers had names like GULF HAWK and GULF QUEEN, but I don't remember the name of this Gulf tanker now that passed us early in the morning, about 8:00 a.m. About five in the afternoon we received an SOS that she had been hit. The old man kept our ship just as close to the shore as he possibly could.

After that news, with no time to eat, I was on the four-to-eight watch. Well, I waited and waited for my relief to come down but no one came. Everything was running perfectly. For an hour, I had not touched a thing. So, I said, "Heck, I'm going to go and get dinner and come back down here to eat it." So, I went up and got a lunch plate and as I was coming down to the engine room, the second boiler popped off. Well, I opened the water valves to the boiler and brought the steam down so the relief valve could reset. About that time the chief engineer came down. He was a Greek, and he was mad and was cussing me. I took it for a few minutes then I reared back at him. Then he realized that no one had come down to relieve me for supper and that I was the only person down there. So, then he jumped on the

rest of the engineering crew. After my watch he came to talk to me in my fo'c'sle. He was laughing. He said that when the boiler popped off, all the Cubans came out, blessing themselves. He could not get through. He was mad because he could not get down to the engine room. Well, after that trip, I . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Why didn't the relief come?

Donald R. Summerville:

They were scared to come down, I guess. I don't know. After that, I did not have any trouble.

Donald R. Lennon:

You did not try to respond to the SOS?

Donald R. Summerville:

We kept our watch, but they were so far ahead of us and we knew that other ships were there.

After that trip was over, I think that I was on the ROGER MOORE--it was the ROGER something. It was a Liberty ship and the first Liberty ship I was on. We went to the Azores and back home again. I stayed home for two trips. Then, we went again from there down south to the islands, to Trinidad, and on through there and back up again.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you carrying?

Donald R. Summerville:

Just general cargo.I was studying for my license all along to become an engineer. In the fall of 1942, I stopped off in Baltimore and sat before the Coast Guard commander to get my engineer's license. It takes about three days of sitting and writing questions and answering questions to get your license. After that I got on the . . . I don't remember the name.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you carrying on the Liberty ship?

Donald R. Summerville:

Just general cargo.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were using Liberty ships for general cargo as well?

Donald R. Summerville:

Most of the places that we were going . . . the Liberty ships were going to Army and Navy bases.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking that they were primarily used for personnel carriers or for Army supplies, such as armament, jeeps, etc.

Donald R. Summerville:

That's what we were carrying to the Azores. We went to Puerto Rico and Trinidad-- they had a base in Trinidad--and it was just general cargo for them.

Then, they had invaded North Africa by this time, and I got on a ship and we went to Casablanca and unloaded our cargo. I believe it was early 1943. Then I went back home again and got on another ship, the BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. It was a black ship, and I was second engineer. We had a black captain and black chief engineer. The chief engineer was a real nice man and was the head of something to do with the schools in Washington D.C., something to do with engineering.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was unusual to have blacks in command of any type of vessel.

Donald R. Summerville:

The ship's cargo was bombs. It was completely loaded with bombs. We went to Oran in North Africa, and then came back home again and got on another Liberty ship that went to Alexandria, Egypt. We came back . . . no we went back to Oran, loaded up supplies, and then went into Sicily, which had just been invaded.

We went to Sicily and then back again to Bizerte. We were on a run between Bizerte and Sicily. Then after the invasion of Salerno . . . we were in Salerno about four days after the invasion, unloading supplies--mostly medical supplies, mail, and troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you bringing them from?

Donald R. Summerville:

Either from Bizerte or Oran or Algiers. They were drop-off points, and we just ferried them across. Then in the early forties, 1943 or 1944, we went into Naples. We were

the first or second merchant ship to go into Naples. We were loaded down with mail and medical supplies. We could hear the shelling north of Naples. The Corps of Engineers came into Naples and was working on the docks. The Germans had put torpedoes on the water lines facing the docks. They had all kinds of booby traps, and we were told not to wander too far from the docks. We stayed pretty close to the ship. A couple of us did go into Naples. Then we went back home, if I am not mistaken. We got another load and went to Naples and then to Piombino. On the way back from Piombino, we were notified about an Italian submarine. One morning this sub came to surface right beside us, no more than a hundred yards from us, and we escorted it into Palermo. I don't know if it was a surrender or what.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was it the Italian submarine that you had been warned about?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. It cruised along with us all the way down. Starting with the ship I was on that went to Aruba, the ships that I was on carried Navy Armed Guards. They had one five-inch fifty astern, a three-inch fifty on the bow, and six twenty-millimeter guns on it.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many in an Armed Guard?

Donald R. Summerville:

About thirty. We assisted the Armed Guards in the drills. We passed the ammunition up to them. We did the heavy work.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this still on the BOOKER T. WASHINGTON?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, this was on all different ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where did the submarine come up?

Donald R. Summerville:

I don't remember what ship I was on.

Donald R. Lennon:

If they surfaced right up out of the ocean, they were liable to get picked off by a fighter or a bomber whereas if they came up close to a merchant ship, they would be . . . .

Donald R. Summerville:

Somehow the higher officers knew about this submarine and the submarine agreed-- we didn't know anything until the captain told us at the table later that morning that the submarine would appear at such and such a time.

They were doing a lot of work on Merchant Marine ships over there. They were putting these large hooks down by the waterline on both sides of the ship. They were putting up something like a king post on the side of the ship. I later learned that they would hook a barge to the side of a ship on these hooks. They would then draw the barge up to the side of the ship, lying flat, and upright. The ships were going in for the invasion of Southern France. It was hooked with pelican hooks, and they would knock the pelican hooks loose and the barge would just fall back into the water and bounce off their hooks at the bottom. They would load them up with supplies. They had big Chrysler engines on the back of the barges. I saw some of them. We left there and went back to . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there a great concern about mines? The Germans had not mined the waterways there?

Donald R. Summerville:

We had these airships on the BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Every ship had a large balloon--kind of like you see floating in the air at car dealer lots. It was fastened to a heavy wire to keep the dive-bombers from diving on the ships. They were up in the air and these balloons had long streamers of wire hanging down from them. It did not last very long because the static electricity would set the helium off or whatever they had up there. It was not helium; I guess it was hydrogen. It would explode or one would break loose and the Armed Guards would use them for target practice. That only lasted one trip. After that, I went back to Palermo and then to New York and the company transferred me back to San Francisco. I went to San Francisco and got a job as a second engineer on the CAPE

FLORIDA. From there, I went to Hawaii, to Wake, to Ulithi, on down to Port Moresby, to India, and then to Finschhafen in New Guinea.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was a period when that entire area was a pretty hot spot.

Donald R. Summerville:

Not then. Most of the fighting had moved north of the Marshall Islands. The Philippines were still controlled by the Japanese. Then I went back to San Francisco. We loaded up--these were strictly supplies for the Navy such as food, cargo foods, powdered milk for ice cream, all that stuff.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was pretty horrible stuff.

Donald R. Summerville:

I did not eat any of it. The first trip we took on the FLORIDA was in February of 1945. We hit a terrible storm off the coast of Oregon, and two of the Armed Guards went to the bow of the ship to check on an ammunition locker because the door was flapping back and forth. They went to close it. When they came back, a large wave washed over, and they were washed down the deck of the ship. They hit their heads on some iron cleats and fractured their skulls. We broke radio silence and they told us to come into San Francisco. They were immediately transferred to the Naval hospital. We dropped anchor in the bay. When we were getting ready to depart, we could not raise our anchors because it was an all-electrical ship, diesel-electric. All the winches were electric and all the motors for raising the anchor were electric. The waves that had washed over had gotten into the control room, which was a little small shack between one and two holds, and shorted out some of the circuits. We had to wait there until it was repaired. They had to change out some of the circuits and replace contacts and all that.

Donald R. Lennon:

They did not have some alternate means for over-riding the electric, for raising the anchors and things of that nature?

Donald R. Summerville:

I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

So, if it went down, you were just out of luck?

Donald R. Summerville:

I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

No manual backup?

Donald R. Summerville:

Not on that ship, they didn't. We were repaired in a day or two. This time we went into Ulithi and stayed there. One morning when I got off of watch (I was on a diesel job), I was eating by myself. A mess boy had served my plate. The radio was on and they were playing some sort of music (it was Friday 13) and a news bulletin came on that Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died. I stopped eating and went to tell my captain. My captain didn't believe me. About that time a newsflash in the harbor came over. Everyone lowered their flags half mast. I heard that Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr., was there in the harbor as commander on a supply ship, a barge. Is that right?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Donald R. Summerville:

A ship went out to his barge and took him back to shore so I imagine that he went back home.

After that, an invasion of the Philippines went on. Ulithi was loaded down with ships--supply ships, aircraft carriers, everything was there. The RANDOLPH, a carrier, was anchored behind us, within two hundred yards. They signaled to us that they would like us to come over to visit and to see a movie. A lot of us got ready to go over there. Just as we got ready to leave the ship, two kamikazes came in. One struck the RANDOLPH and one struck Marine barracks on the island. They killed nineteen men on the RANDOLPH. The RANDOLPH did not go back; they repaired the ship right there.

After that, we went into Tacloban, Philippines. As a supply ship for the Navy, we were accustomed to going to different ships in the harbor and supplying them. Some of the Armed Guard and some of the Navy crew got to be pretty good friends. They would come over to our ship to visit, trade magazines, and so forth. In Tacloban, this boy from the RANDOLPH came over. The RANDOLPH was in the harbor first, for about three or four days. He told us how the ship had bad luck. While they were anchored in Tacloban, an Army Air Force ship was doing stunts over the harbor and crashed into them. This boy wanted to get off real bad.

We left there and went to Hawaii. We loaded in Hawaii and then headed back out to sea. We got to a certain point in the sea and came to a stop and then took it slow motion ahead. There were just a few ships around and then all of a sudden we saw all kinds of Navy ships. We were to report to the WISCONSIN because we had a bunch of supplies for them. We were at the stern; another merchant ship was unloading ammunition to them at the bow. On the other side was a tanker. We were underway at about ten miles an hour.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you use cargo lifts to move the supplies in?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, just cranes. We left there and went to Guam, I think, I am not sure. Then we went back to the States. This was the latter part of 1945, and then the war was over. I was in Portland, Oregon. Some friends of mine were engineers, and they were loading up with grain and were going to take the cargo to India. They begged me to come aboard. I said, "No, I just got off this ship, and I want to go back to Los Angeles."

Well, I did not get on the ship, and it was never heard from again. They found the wooden nameplate floating on the water. They figured it was a leak and the grain swelled

and popped the ship open. I went back to Richmond. I notified my draft board. Then in early 1946, I got a notice from my draft board to report for induction into the Army.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were drafting in 1946?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes, in early 1946. So, I said “the heck with this” and I got on a merchant ship and went to Germany to take sugar and all kinds of supplies. I came back to Baltimore and then back to Los Angeles. I got a job with General Motors. I worked with them until 1951, the latter part of 1951. The Korean War had started. I was transferred out of Los Angeles to Norwood, Ohio. I was studying to be a junior engineer for the company, and they transferred me to Cleveland. They had an explosion in an acetylene plant. It blew up. I went to help there. From there I went to Grand Rapids, Michigan. I had a lousy job. They demoted me to a foreman's job, cleaning soot off of rafters. The soot was floating on the new cars. The soot was from the Nickel Plate Railroad, which ran right next to the plant. With the windows open, the soot from their steam engines would filter into the plant, and every week I had to vacuum off all these girders in the plant. I quit and went back to the Merchant Marines. I went back to San Francisco and got a job with Pacific Tankers in a Navy ship. I had the joy of being an officer aboard ship, and all officers had to join the Navy Reserves.

We went from there to Japan and then to the Persian Gulf for thirteen months.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was an oil tanker?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. A Navy oil tanker. We went to Sasebo and to Subic Bay and all sorts of ports like that. We came back and they put the ship in mothballs. I was transferred to the MISSIONSAN FRANCISCO and made one trip on that. I came back, then took a vacation, and went to Richmond to see my folks.

Donald R. Lennon:

How long would one of these trips last on a tanker that went to the Persian Gulf and then to Subic Bay?

Donald R. Summerville:

Thirteen months. The next one was just over and back. I got into Richmond and spent two weeks and then I got a phone call that they wanted me to get my clothes ready and report back to Seattle. They had a tanker that was in distress in India. When I got to San Francisco . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you get back?

Donald R. Summerville:

I flew. My brother drove me up to Washington where I caught a flight to Seattle, stopping off in Chicago. I picked up my papers and orders and everything I needed from the company in San Francisco. I flew from there to Alaska and then to Hong Kong and then to Bombay, India. What happened with this ship was that they were coming out of the Persian Gulf with a load of oil and a small spool piece from the sanitary pump to the skin of the ship ruptured. The watertight door was not closed and it filled the bilge full of water. It was a turbo electric job with a ten-thousand-horse motor. Water got into the windings of the motor and the ship was dead in the water. They fired the captain and the engineer; they fired a bunch of them. I got to Bombay and went aboard that ship. It was the SCHUYLKILL. It was one awful looking mess in the engine room. All of the insulation was hanging down from the pipes and everything was covered with fuel oil. It was in dry dock when I got there, and we got a bunch of Indians in there to wash down everything and clean up the deck and all the bulkheads. We were pulling motors out, one after the other, to have them washed clean and baked, and then tested. We were there for about two months. Meanwhile the ship was pumped out and I took it back to the Persian Gulf, loaded it with

fuel oil, and took it back to the ports. I was on the SCHUYLKILL, the CATAWBA, and some other Navy ships until 1955. Then I said "to heck with it" and I just got off.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you were basically in from the late 1930s to 1955.

Donald R. Summerville:

There were some times off in between. I did not take one ship after another. In the 1930s, I worked for a year for C & O Railroad.

Donald R. Lennon:

And then you were with General Motors.

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. For five or six years.

Donald R. Lennon:

In World War II, were you ever part of a convoy or did you sail strictly alone?

Donald R. Summerville:

We were always in convoys. When we were coming back from somewhere in North Africa, the ship had a bunch of German prisoners on board. They let the prisoners out on deck at intervals. As we were coming into Norfolk, we were about one hundred miles out of Norfolk, this convoy came by and there must have been one hundred and fifty ships. The German soldiers on deck could not believe it. The propaganda over there related that the Japanese had destroyed half of our ships on the West Coast and that the German submarines had destroyed most of them on the East Coast. Those boys could not believe it.

We brought back a lot of wounded. One of the ships I was on was a troop ship, and on the way back we would bring back the wounded. There were Army doctors, I don't know how many, and nurses on the ship. They had their quarters--I don't remember where they had quarters.

They had a saying back in 1942 and 1943 that they carried torpedo nets on the side of the ship. They had two large booms that went outside the bow and the stern. They carried that net in there. A merchant ship could only make eight or ten knots at the most. Eight knots was usually the speed of the convoy--you went as fast as the slowest ship. Well, the

nets in the water would bring down the speed to five, six, or seven knots. We despised seeing the ships with those nets on because we wanted to get back to shore. I have never heard of one of those nets saving a ship. There must have been a reason for it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, because even battleships, when they were at anchor in the ocean, would drop nets around them.

Donald R. Summerville:

I can see that, but I do not understand it in a convoy. One thing that we welcomed were the Navy blimps during the war. They would meet us two hundred miles out at sea and convoy us in and that was a blessing, because they just hovered over us.

Donald R. Lennon:

They could spot a submarine from the air.

Donald R. Summerville:

The first depth charge I ever heard was in 1942. I was in the engine room and it sounded like it was right next to us. I was on watch and I remember the engineer asked me if I was scared. I said that I was as scared as the devil. He sent the wiper up to the top. The wiper came down and we asked him where the depth charges had been. He said, "Oh, about eight or ten miles away."

Another time we were coming up the coast of New Jersey and we dropped off the squealer. German submarines supposedly had some kind of device that allowed them to pick up the noise of a ship and go toward that noise. We towed this squealer. It had a propeller on it and it made a real loud squeal, but it also shot up a rooster tail so that the ship behind us could see it in a fog. Coming up the coast we had these things out.

Donald R. Lennon:

How far were they behind you?

Donald R. Summerville:

One hundred fifty to two hundred yards. We were coming up the coast and I came off of watch at 8 a.m. I walked up on the deck and just looked down. There was a white fog out. I said to a black seaman, "Look at the porpoise over there." He said, "That's no

porpoise." Then we heard general quarters and all the whistles started blowing and we got back in formation. About that time a Navy destroyer escort shot across our bow and laid a stream of depth charges, about a quarter of a mile from us. Another went this way. By that time, we were getting into our convoy formation. When we got into our position, we were on about the second row in from the outside lane. The boys told us that they could see the oil and life preservers coming up.

Donald R. Lennon:

They got them.

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. But I will never forget that destroyer escort coming right across our bow.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you had the German prisoners of war aboard ship, did you have any problems with them?

Donald R. Summerville:

No. Not at all. In fact, we got hit over in the Mediterranean by a Swedish tanker--we were rammed. We went into a little town, I don't remember the name--it was south of Brindisi. We had some dry docks there. We had the German prisoners working on our ship. There was a German officer named Shikow(?). One day our captain walked off the ship, this Major Shikow(?) gave him a snappy salute. I was a young kid only twenty some years old and told him to give him the Heil Hitler salute. And he turned around to me and spoke to me in perfect English, and I was surprised. We begin talking and became friends . . . well, we were not really friends, but I would bring him a meal from the mess hall at lunchtime and we would talk. I asked him how he ever got mixed up in Hitler's regime. He said that he was a professor at a university there. He had been educated at Oxford. He said that although he was against the war he had to join the Army or they would have persecuted his wife and daughter. He got into this Panzer division. We talked about the American soldiers and officers. He said that the American officers were some of the dumbest people

he had ever come across, because you could not figure out what they were going to do. A German officer had years of training, but an American officer had only three months, so you could never figure out their movement in the line of battle. I asked him about the American soldiers. He said that they were the best in the world. The German soldiers were so dependent on their officers that they could not fight for themselves if their officer was not there with them. But the American soldiers could be separated from their officers and still carry on the fight. Shikow's(?) sister lived in Milwaukee.

There were some times that I would not want to live through again.

Donald R. Lennon:

Such as . . . .

Donald R. Summerville:

The bombings. We went down to Alexandria one time with two or three other ships with us, but in no formation. We were attacked by German submarines. It was difficult to see the ships go down. Another time we were coming through the Strait of Gibraltar. One of the large British passenger ships had been made into a troop carrier, and it was going out with us. All of a sudden we got a notice to stop the engine and lay dead in the water. The British came out and started dropping depth charges all over. What we heard later was that the Germans were sending submarines under the fleet of ships coming out. Things like that I don't like to remember.

Also, in Oran one time, I asked a sergeant who was driving one of the trucks that were unloading bombs off the ships where he was taking them. He said that he would show me. I jumped in the truck with him and he had small 250-pound bombs and we went out into a field and as far as you could see there was nothing but bombs.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this in North Africa?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. He opened the tailgate and all the bombs rolled right out on the ground. But they were not fused. There were men out there, stacking them up in racks.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was near an Air Force base that was bombing north into Europe?

Donald R. Summerville:

They had a big one in Tripoli. And there was a base outside of Oran.

Donald R. Lennon:

I had a good friend who was stationed in North Africa as a pilot. I cannot remember the name of the base.

Donald R. Summerville:

They had bases all up and down that place there. About eighteen miles west of Oran there was a real small port. I went sightseeing one day. I happened to be there when the MERCY, a hospital ship, was there and another hospital ship, a German hospital ship, was there and they were transferring wounded. You could not get near the ship. I saw it from the bluff, a quarter of a mile away. They were transferring back and forth. At one ship stood a German guard and at the other ship stood an American guard, three hundred yards apart.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were in a convoy like that and you were attacked, were you able to stop and help pick up survivors or did you leave that entirely to the destroyers?

Donald R. Summerville:

It was left to the destroyers. We came through Gibraltar one time and I don't know how far up we were into the Mediterranean, but we saw an American soldier's body here and an American soldier's body there and pretty soon we saw thirty floating in the water, all dead, where a troop ship or something had been hit.

In 1946, I went back to Germany. The Germans were busy taking the debris from the bombing, chipping off the mortar and stacking bricks and rebuilding. This was the first time I ever got in a fight with a Russian. We were at some bar, drinking, and there was a bar maid there. American cigarettes were a big thing, so I offered her one and she took it and

then she began paying more attention to us than to the Russian group. One of the Russians got up and said something to me. All I heard was that this was his girl. The next thing I knew they were escorting this Russian out; he had gotten too rowdy. They blew a whistle and the doormen came in and escorted him out; he had gotten quite rowdy. I was there with a couple of guys drinking a beer. The next thing I heard was a window crash. This Russian came right straight for me, grabbed me by my shirt, and pulled me around on my stool. We got in a good tussle, wrestling.

Donald R. Lennon:

You are a big man. How big was he?

Donald R. Summerville:

He was close to six feet tall. But he was loaded down with an overcoat and vest. It was not anything but a push and we both fell to the floor. A couple of guys separated us and the next thing I knew a policeman had escorted him out. I don't know if there was a punch thrown or not.

Donald R. Lennon:

After the war, when you went to tankers, was there ever a--I don't want to say crisis--but you were carrying a rather volatile commodity on those tankers. Ever any danger?

Donald R. Summerville:

Do you mean during the Korean War?

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, not necessarily due to warfare but due to the nature of your cargo. Did anything ever go wrong?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, nothing went wrong. When you are loaded down with bombs, you get a bonus. I think it was a 100 percent bonus, because the wages of a third engineer ran $136 per month. Doubling that made a very attractive salary. I remember one time we were loading in Baltimore. We were loading up in a hatch--they had built a large wooden box in that place--and putting detonators in. They would put a row of detonators, paper, then sawdust

and something else. All those detonators went in. I asked this man how many tons we were carrying. He said that it was not many tons. It was not enough to get a bonus, but it was so explosive. I remember that on top of the hold they put crossties--perhaps four feet high.

Donald R. Lennon:

To keep it from shifting?

Donald R. Summerville:

To keep it from aircraft strafing, I guess. I remember unloading it--the Army was very careful unloading it. But the bombs . . . they would put four of them in a sling and hook them together. They would just rock back and forth and be bouncing into each other.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they carry detonators and bombs on the same ships or on different ships?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, on different ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

But the load of detonators was probably more dangerous than the load of bombs?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. They put them in the number one hold always.

Donald R. Lennon:

What would go in the other holds?

Donald R. Summerville:

Just regular cargo. I guess if it blew, it would blow the bow off and not sink the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned that one of the ships you were on was a Liberty ship.

Donald R. Summerville:

Most of them were Liberty ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, okay, I was going to ask you what the size of the other ships was. We all know what a Liberty ship looks like.

Donald R. Summerville:

The last ship that I was on was a C-2. It was a version up from the Liberty ship (larger and faster). Instead of reciprocating engines, it had turbo engines. I remember going back and forth to the shuttle in the Mediterranean, going over to Malta or to Italy. We would load up in Brindisi. The Army had a sergeant who came out of the longshoremen, a big burly man. He put these tanks . . . I think they were Sherman tanks . . . he could put

those things side by side in the hold. I remember the last tank he put in; he called his men in the hold, and made them get off their butts and push the tank into a certain spot. He was really good. We took the tanks up to Naples or . . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

That was quite a load--those tanks are heavy.

Donald R. Summerville:

They always put the tanks in the number two hold because it had that heavy hook up there, a crane, and the number two hold was the largest hold on a merchant ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

Also, it is more in the center of the ship, which provides better balance.

Donald R. Summerville:

They say that when a merchant ship is loaded the only thing that keeps it afloat is the space in the engine room.

Donald R. Lennon:

The hatches in the hold . . . how large are they so that you can put an entire tank in?

Donald R. Summerville:

I think that a hatch was about seventy-one feet wide.

Donald R. Lennon:

It took up almost the entire deck?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes, there were about four or five feet on either side.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did the hatches open? Did they open up like doors or did they slide?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, they had beams going across. The hatch covers were about three by five feet. They were made of two-inch wood with cups inside so you could pick them up. When the hatch was open, steel beams stretched all the way across. We would set those hatch covers right on the steel beams and then cover them with a tarpaulin. On the side were wedges that we would drive against it to keep the tarp tight.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have anyone fall through the hatch holds?

Donald R. Summerville:

No, but when we were unloading sugar in France, one of the workers down below went out to fill the cargo net and the cargo net on top split and a bag came down and killed him.

Donald R. Lennon:

As an engineer, you were responsible only for the engines?

Donald R. Summerville:

The engines, water, and all the fuel. The galley ran off diesel fuel. We did not have any means on a Liberty ship to make water.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you had to carry with you what you would use.

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. On the tankers we had what we called a solar shell. I don't remember how many tons of water we could make in a day, but we could make water when we got about two or three hundred miles from port. We would fill our cofferdams between the engine room and the pump room. That would be good water. We would pump it to the Army base in Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

In your experiences during the 1951 to 1953 period, did the Korean War have any impact on your duty? Did you ship into Korea during the war period?

Donald R. Summerville:

We shipped into Inchon and Puson. I was in Puson while it was burning. I don't remember what year it was.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any particular recollections of that?

Donald R. Summerville:

I can remember seeing the blaze.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were aboard ship?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. I think that we were in about a thirty-eight-mile perimeter. I think that is when MacArthur invaded. I still have some propaganda that we dropped over when the Chinese were in North Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Naval Armed Guards on the ships you were on . . . what were their duties other than just being there if the ship was attacked?

Donald R. Summerville:

They stood watches in all kinds of weather. They had two in the stern, two in the bow, and one or two on the bridge.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your ships were never attacked?

Donald R. Summerville:

By airplane fire?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

Donald R. Summerville:

Only once, when I was in Oran when the Germans were still fighting in North Africa and one plane came over photographing. The harbor was quite small and to be honest I don't even remember seeing the plane.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, most of your duty was below deck anyway, which was fortunate for you.

Donald R. Summerville:

For a while, they were a menace. The Germans would swim out underwater and place magnetic charges beneath the waterline of the ship and set them off.

Donald R. Lennon:

Kind of frogmen type?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. To stop that, we had a small launch that would go around--you could not hear the launch at all--and they would drop a small depth charge. You could sit at night in the engine room, reading a book and relaxing, and all of a sudden it would go off and it sounded just like you were in the inside of a bell.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they do this routinely or at random?

Donald R. Summerville:

They did it at random.

Donald R. Lennon:

Not because they saw anyone, just at random?

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

I never heard of that before.

Donald R. Summerville:

I think that we were the only merchant ship that I can remember to escort a submarine. We escorted that submarine from up around Rome south to Palermo, which was the headquarters for General Clark.

Donald R. Lennon:

I presume by that time the Italians as a fighting force were out of the war.

Donald R. Summerville:

I don't know. I don't remember. The Italians surrendered shortly after the invasion of Sicily. One of those submarines was stuck up north and we did not want the Germans to get it.

I remember one time somewhere along the west coast of Italy I saw a group of bombers go over. I guess there were ten or fifteen of them in that group. A minute or so later, here came another all by itself and it was dropping all kinds of ammunition. You could see it coming out of its doors. It was running on one engine, going back to its base.

I made one trip over to the west side of Italy. That was on a shuttle run. We went to Barletta. It was a very small harbor. It had a sea wall and it could hold about two or three merchant ships. Well, two merchant ships were in there and the Germans came over and bombed them. One of the merchant ships was loaded down with mustard shells. Some of the seamen and Armed Guards jumped in the water and that mustard was all over the water. We brought some of them back. This one young Merchant Marine, just a young kid, would scream from the top of his lungs when they changed his bandages.

Donald R. Lennon:

It had burned off all of his skin, probably.

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes. I guess we just had it over there in case the Germans used it, we would use it too.

In the invasion of Sicily, we went in the second day or so, carrying supplies. I did not see any fighting whatsoever. I understand Germans were in command in certain areas and there was quite a bit of fighting.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, there was. There was very rough going for a while.

Donald R. Summerville:

I did not go ashore. Some of the men ferried the boat over. While they were unloading, they went ashore. They said the Italian bunkers were beautiful and did not have a shell mark on them. The Italians had deserted them.

Donald R. Lennon:

They promptly fled.

Donald R. Summerville:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any other thoughts or experiences that come to mind?

Donald R. Summerville:

Later on, we had a load of diesel fuel. I don't remember what ship I was on--it was a USNS San Gabriel ship--but it was a big tanker and we were going up to Saigon. This was while the French still had the port. We went to the port and we had two small escorts. We were told to keep our portholes closed and not be on deck. We were thirty-five or forty miles north of Saigon, at an outpost. There was a fork in the river and we picked up a French pilot in the Saigon River, which is like a snake.

Donald R. Lennon:

How large a tanker was this?

Donald R. Summerville:

Six hundred ninety feet--it was quite large. We were not completely full. We had some fuel, but after we left there we headed back to the Persian Gulf. We had this port to call on. I remember being on deck--I was not on watch--and the captain was a very peculiar captain. He wanted his ship in tiptop shape. It was very nice. Everything was spick and span. Well, this French pilot eased the ship right up on the bank, with the nose on the bank,

and used the cross current to turn the ship around. The current turned the ship around. That captain was as white as a sheet because he thought the ship was going to run aground.

We got to the port and there was a large water tower and a large coal pile there. These women coolies were loading coal and carrying it off with these yoke-type carriers. This French officer came aboard and we exchanged money and he told us that if we went ashore not to try to come back at night because we would probably get killed. So, the first night I did not go ashore. I found out the reason you would probably get killed. They had a large searchlight on top of this water tower playing across a huge rice paddy, maybe a mile across. There were machine guns posted all around. They would fire at anything that moved at night. It might be a water buffalo or it might be a man. Whatever it was, they would shoot at it.

The second night, I went ashore. I went down to Saigon. It was a night that the passenger ship, the LOUIS PASTEUR, was coming back in. I went to get a room at the Prince George Hotel. They did not have any rooms. I got a coolie to take me around on a rickshaw to find a room. He took me to someplace where there was opium burning. I did not want that so I told him to take me someplace nice. He took me down to the compound, which was nothing but a big whorehouse. It was filled with French soldiers. They were French Foreign Legionnaires. Most of them were German, but they were in the French Foreign Legion. I wanted no part of that, so I had him carry me back to the Prince George and I told the night clerk that I was going to sleep in the lobby or on the floor somewhere if he didn't find me a room. They did wind up giving me a room for the night.

[End of Interview]