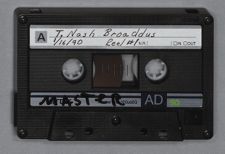

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #118 | |

| T. Nash Broaddus (DECO) | |

| January 16, 1990 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you would, start with your background and lead into your naval experiences.

T. Nash Broaddus:

I was born in Richmond, Virginia, October 18, 1918. My father was a doctor who died during the flu epidemic in 1918, two weeks before I was born. I was an only child. I was reared by my mother, who was a schoolteacher and later became supervisor and principal of a school in Richmond. She died three years ago at the tender age of ninety-five.

I went to public school in Richmond. I graduated from Thomas Jefferson, which in those days was a new high school. In 1935, I went to the University of Richmond and was in the Class of 1939. I took pre-med, but I didn't want to be a doctor; because my father had been, everybody else wanted me to become a doctor. I eventually quit school before I graduated.

Every summer of my life I spent at my mother's homeplace down on the Rappahannock River. So I was near the water and had always loved the water.

Before the war, I read Mein Kampf, Hitler's prescription for conquering the world. I believed it and felt there was a war coming and I decided to join the Navy.

Donald R. Lennon:

You actually joined before the war broke out?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. I was living at home with a friend of mine, Winston Burgess. I was working for the highway department and he was working for Glidden's Paint Company. I talked Winston into joining the V-7 program in July of 1940. At the time, the Navy had opened up a program for people who were not college graduates but had, I guess, at least two years of college.

My vision was not 20/20. I talked Winston into going to the Naval Reserve Armory to copy the eye chart. He didn't want to do it, so I went down with him, copied the eye chart, and memorized it. The eye chart had seven lines with eleven characters across. I can still remember the first line. It was "A, E, L, T, Y, P, H, E, A, L, T." These were all unconnected letters--seventy-seven of them. That's how I passed the eye exam and joined the Navy.

In July of 1940, I went on a cruise as apprentice seaman for thirty days on the USS ARKANSAS, a battlewagon built in 1912. I think there were thirty of us living in a gunroom. The gunroom on the old battlewagons had twenty five-inch surface guns, which stuck out through the sides of the ship. There were not any anti-aircraft guns.

The room was not very large. At night, there were three levels. If your hammock was spread on the deck, there were two more levels of hammocks strung above. They were the most crowded conditions I ever saw in my life.

By this time the program had been over-subscribed and many of the group were released. I managed to stay on and came back and went to Northwestern, the downtown campus in Chicago, as a midshipman. I went from December of 1940 till mid-March of 1941. It was a rigorous program.

I lived in Abbott Hall, a fairly new dormitory in those days. I believe it had been a dormitory for the medical college. I had a corner room that I thought was pretty big. However, last year I went back to Chicago and looked at it; it was really quite tiny! Four of us lived in there.

The routine was for you to make it into the "Tree." The "Tree" was published weekly and showed how you did that week in your classes. You took classes in gunnery, navigation, seamanship, and naval procedures, and then you were also graded on aptitude. Five grades were given every Friday and posted in the dormitory.

Donald R. Lennon:

That aptitude was very important, wasn't it?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Aptitude counted about fifty percent. If you made less than 2.5 on any two of the five classes in one week or if you failed the same subject two weeks in a row, you were gone by Sunday.

I had twelve roommates during the three months I attended Northwestern. I think there were about eleven or twelve hundred of us who started, but only eight hundred were commissioned. It was a pretty good weeding process.

I put in for PT boats. You could put in for what you wanted and did not have to go into active duty. This was March 1941, nine months before Pearl Harbor. I was accepted for PT boats, but during the last week, I was informed we were going to fly to Newport the day of graduation to commence training for PT boats. Since I was engaged to be married immediately after graduation, I opted out and took inactive duty. I was called to active duty right after. It was just as well I didn't get into PT boats, because I would have been part of Bulkeley [John D.] and his crew that went out to the Philippines. Robert B. Kelly, who was

with Bulkeley, had been one of my instructors at Northwestern. I was in the second class and he had been in the first class.

I ended up with orders to report to the USS MOONSTONE, which had been a yacht, 170-odd feet. A beautiful craft. She had been built in Kiel, Germany. She had Krupp diesel engines in her. She had a clipper bow, a cruiser stern, and looked as if she could go thirty knots. Wide open, she could actually do eleven and a half knots. In dry dock you could see her big potbelly, but she was a well-built ship.

I went to Jacksonville where she was being converted. She had been the yacht, LONESTAR, previously owned by a Boston banker. He had once used her as the tender for his America's Cup contenders. Are you interested in something of the yacht?

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes.

T. Nash Broaddus:

This is sort of interesting. I believe his name was Frederick H. Prince. The yacht was built in 1929 by a man named Bohr, a stockbroker, who paid a million dollars to have it built. When the stock market crash came, Mr. Prince bought the yacht for $85,000. He kept it until 1940 when he turned it over to the Navy for $85,000. She was completely equipped with the most beautiful furniture and silverware.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was the Navy making a practice at that time of looking for boats they could convert for various purposes?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, for patrol purposes, because they didn't have many patrol boats. The Navy had very few boats in those days, particularly anti-submarine or patrol craft; so they took over a lot of yachts.

Donald R. Lennon:

The LONESTAR was being converted for anti-submarine duty?

T. Nash Broaddus:

She was being converted into an anti-submarine vessel and as the flagship for Admiral Taussig, who was Commandant 5th Naval District. The LONESTAR was converted at Gibb's Gas Engine Works in Jacksonville, Florida.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was this Joe Taussig's father?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. The skipper of her was a guy named Delancey Nichol. Taussig was the one who took the first destroyers over in World War I. Delancey Nichol had been his flag lieutenant and had been a reserve officer. He was quite a yachtsman, very wealthy, lived on the south shore of Long Island, up near Oyster Bay.

I reported to the LONESTAR to help convert her into the MOONSTONE. My orders were to keep her absolutely as yacht-like as possible, but yet make it a Naval vessel. She had beautiful giant mahogany rails, a broken deck (the break on her bow was just under the pilothouse) and beautiful white teak decking. We kept all that. Everything was in super shape.

I remember when we took her out on the acceptance cruise, down the St. John's River to the ocean, and her steering operation failed. There were only two officers aboard, Delancey Nichol and myself. He was the skipper and I was everything else. We rigged the tiller, which was the emergency steering, and had half a dozen sailors with blocks and tackles going up the sides, top, port and along the rails, hauling on the lines. Delancey Nichol was on the bridge screaming through a megaphone to some guy standing on the boat deck. He yells, "Ports you're a helm!" Well, I didn't have to convert this. Delancey was quite a sailor.

The boat was brought under control and we sailed all the way up the St. John's River to Jacksonville with this jury-rigged tiller! My first voyage as a naval officer was a pretty exciting one.

We went to Charleston for outfitting. At that point in time, we had a change in duty. This was May of 1941. Delancey Nichol was relieved of command and sent to Norfolk to Com 5 to Admiral Taussig. He eventually wound up becoming commanding officer of Ernie King's yacht, the WILLIAMSBURG, which is a huge yacht based in Norfolk. Delancey wanted me to go back with him. We had become quite good friends by that time.

A regular Navy officer came aboard as commanding officer--Paul Johnston (Class of 1927). He wanted me to stay because I was the only one who knew anything about the ship. It was quite a decision, but I opted to stay. By that time, we had perhaps eight officers aboard. Bascom Jones was the exec. He had graduated with the Class of 1918, had gotten out of the Navy, then come back in.

We were sent to the Panama Canal Zone with another yacht of similar size. The other boat had been the one Douglas Fairbanks and Lady Ashley had cruised in back in the twenties--the famous "love cruise." The yacht had been bought by a man named Dr. Brinkley who was quite famous. He was barred from this country, but he went to Mexico and set up a powerful radio station where he advertised monkey glands as helping male potency! He was quite famous in those pre-World War II days. His ship was named DR. BRINKLEY. When the Navy took it over, they showed rare humor when they named it the JADE. I thought that was quite appropriate based on the history of the ship.

The JADE and the

MOONSTONE sailed to Panama together. After clearing the Canal, we headed south. This must have been in the late summer or early fall of 1941. The MOONSTONE was going to be given to Ecuador and the JADE was going to be given to Peru.

Donald R. Lennon:

They decided not to use it for Taussig?

T. Nash Broaddus:

That was decided before we went to Panama. I was communications officer at that point in time and the assistant navigator. I was given a strip of code. Are you familiar with how they used to do the codes? Our messages were on aluminum strips that you'd slide back and forth in a decrypting device to decode. Unfortunately, I was not given a decrypting device; so I had to take brads and a board and build one. It was the only encrypting/decrypting device we had.

We set sail and just about the time we got to the equator, Peru and Ecuador went to war with one another! The Navy turned us around and we ended up on patrol duty in Panama.

Donald R. Lennon:

If the United States was so short on naval vessels why were they giving them away?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I don't know. I can't answer that question. But later on, I'm sure that they were quite happy they did not give away these two because they didn't have much.

We were based in Coco Solo, on the Atlantic side, with quite a few other yachts. We patrolled the coast. Some of the most interesting duty I ever spent was just before the war in the fall of 1941, setting up outposts along the Atlantic coast of Panama--from Colombia all the way up through Central America. I guess they must have figured the war was going to come.

There was an ONI (officer of naval intelligence), named Commander Rose, based in Panama. He had been with Admiral Byrd on both polar expeditions. He was a wonderful

man. I spent a lot of time with him. We would go ashore and set up these outposts. Of course, he was also scouting for places they could put lookout posts, literally. Later, they put them into effect.

I remember one time we sailed into Chiriqui Inlet, which is in northern Panama on the Atlantic side. Inside the inlet, we anchored the ship and Commander Rose, the coxswain of the boat, the machinist's mate, another ONI man, and I (I was a first lieutenant) went ashore.

Mind you, I was just twenty-two years old then, and Rose must have been a man in his fifties, but he could walk the feet right off of me. I'd walked with him before, so I didn't bother to go with them to look at this outpost. Instead I wandered around, and I came upon a settlement of Indians that spoke neither Spanish nor English. They lived in houses on poles up off the ground, I guess to stay away from marauding animals. I walked in and didn't see a soul. There was a fire in the middle of this sort of camp.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you were by yourself.

T. Nash Broaddus:

I was by myself. I had a .45 on me. I didn't see anybody and then all of a sudden--I guess the men were off fishing or hunting or whatever it was--the women and the children appeared. A couple of the women were swinging large machetes. I made real friendly sounds, because they didn't speak English or Spanish. They were really quite primitive. I had a nail clipper in my pocket and I gave them the nail clipper, and then I indicated that I was thirsty. They sent one of the young boys scooting up a tree to get a coconut. The chief's wife, or whoever she was, held the coconut in her left hand and, with the machete, went zing, zing, zing, and chopped it right off--made a drinking cup of it and handed it to me!

They must have thought I was also hungry. [They had a black pot on this fire and they were very smart. They didn't chop wood, all they did was move the ends of the logs further in.] They gave me something that looked like a stringy sweet potato/turnip kind of thing. It tasted horrible but I ate a little.

The amazing thing was that Chiriqui Inlet was, I think, within a few miles of where Columbus, on his third expedition, went in and careened his boats to clean them. From the 1490s to the 1940s, things hadn't changed a bit. It was very astounding to me.

We went to Coco Solo and then Pearl Harbor happened. I guess everybody knows where they were when Pearl Harbor was attacked. We were on our way back from Colombia. We had been on another mission setting up outposts down there. It was a beautiful Sunday afternoon and I had the deck. The skipper was asleep in the emergency cabin, which was the chart house on the deck. The exec was asleep in his stateroom. The radioman came up and gave me the famous dispatch: "ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR!--IS NOT--repeat--NOT A DRILL."

I went down and shook the skipper--woke him up. He said, "Well, it's been expected." He turned over and went back to sleep. Then I woke the exec up to tell him. He said, "Oh Broaddus, you're pulling my leg again. Get out of here!" He didn't believe me! So that was how I spent Pearl Harbor.

We got back to Coco Solo around Monday morning. They had .30 caliber machine guns mounted on all the pickup trucks and everybody was racing around like chickens with their heads cut off!

Donald R. Lennon:

Like they were expecting a Japanese attack at any time!

T. Nash Broaddus:

Expecting it any minute, I'm sure. The skipper, the exec, and I went up to Captain Doyle's office. Captain Doyle was the senior officer present on the Atlantic side to whom we reported, operationally. He was head of the sub base at Coco Solo. At this point in time nobody knew what to do. While we were in Captain Doyle's office he got a report from the Army coastal artillery station. They had huge fourteen-inch guns mounted on each side of the entrance to the Canal. Of course, since they were only surface guns, they couldn't elevate them over fifteen degrees.

McClellan Battery reported a sighting off the entrance of the Canal. We were the only thing he had that could get underway. Captain Doyle said, "Quickly, go intercept it!"

We went racing back down. Since I could run faster than the skipper and the exec, I got to the boat first. We were yelling as we approached the quai wall to crank up the engine and get ready to sound General Quarters--which they did. We cranked up the engines and went steaming out from Coco Solo.

We got McClellan Battery on the radio and said, "Give us a position of the submarine."

"Well, he's off the breakwater--bearing such and such."

"What is your position?"

"That's confidential information."

We spent half an hour trying to find where the submarine was. They were not allowed to tell us the location of McClellan Battery. They could only tell us the bearing of the submarine. We spent an hour looking and finally came back. That was sort of how the Army and the Navy cooperated in the old days.

After Pearl Harbor, there were four forty-millimeter hand-crank guns at Panama. They were the only anti-aircraft protection that the Canal had on the Atlantic side.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was the size of your crew?

T. Nash Broaddus:

We had between fifty and sixty men and about seven or eight officers. Right after Pearl, Paul Johnston, the captain, was transferred. Mind you, he was a full lieutenant from the Class of 1927 and had never been passed over. This was in 1941. Gives you some idea of the ranks.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was a time of few promotions!

T. Nash Broaddus:

That's right. I was made exec and Bascom Jones became the skipper. Paul went on to be gunnery officer of the SOUTHDAKOTA. He was the gun boss of the famous "Battleship X." Great guy. We stayed in touch until he died back in the early sixties.

We were a patrol unit. By this time the U-boats had moved into the Caribbean. We were underway all the time. This was before they started convoying in February. While at sea, we were sent to probably eight to ten to twelve sinkings to try to pick up survivors. We never got to pick up any of them.

When we started convoying, we would take the convoys from Coco Solo to Guantanamo Bay. I remember the height of this was perhaps in June/July of the 1941 era, when the U-boats owned the Caribbean. The convoys moved at only about four or five knots. To give you an idea of how desperate we were, one convoy had one four-piper destroyer, a Navy tug, four shrimp boats--trawlers gathered from the fishing fleet off the Galapagos--and ourselves. We didn't even have sonar; we had a listening device that was all.

Donald R. Lennon:

You did this for convoy duty?

T. Nash Broaddus:

That was all we had. That was it!

Donald R. Lennon:

How were they armed? With just depth charges that they rolled over the sides?

T. Nash Broaddus:

The destroyer had a sonar-type device; we had a listening device; and the tug didn't have anything. The trawlers were just gathered up, painted gray, and the crews were assigned to the Navy. Whoever had been captain of the trawler was told, "Alright, you are now a boatswain's mate and the skipper of this thing. Off you go!"

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of armament did the trawlers have?

T. Nash Broaddus:

They had .30 caliber machine guns on them.

Donald R. Lennon:

What could you do to a submarine with .30 caliber machine guns?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Not much. The MOONSTONE had a three-inch 23. It was a three-inch gun with very short barrels that you aimed with your shoulder. You had a shoulder pad that helped you move around and you aimed through the sights. Pre-World War I. You've seen them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Right.

T. Nash Broaddus:

That was our main armament. We also had two .50 caliber machine guns mounted aft, two .30 calibers on the bridge and two stern racks with depth charges. I think we carried five depth charges in each rack with one refill, for a total of twenty depth charges. That was it. We used to sneak up the coast of Central America and then race like mad under the Caymans across to Guantanamo.

Donald R. Lennon:

You couldn't do much racing as slow as the ship was.

T. Nash Broaddus:

We'd race at four or five knots and just hope that nobody saw us!

Those days were terrible times. We were at sea from April/May till August when we broke down off Kingston. The MOONSTONE was a good ship, but when something broke, you couldn't call up Krupp in Germany and get a spare part! You had to have the

part machined back in the States and shipped to you. That was a problem. I remember we were waiting for a spare part and operating off Panama when we got word that an air shipment had come in. The skipper put me on an amphibious plane in Coco Solo to go over and pick this thing up. I went over and got these two big crates, and flew them back. We opened them up and found antifreeze for our .50 caliber guns! Air shipped from the United States to Panama!

Later I got transferred to SCTC [Sub-Chaser Training Center] and went on to be an exec of a subchaser.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was in the fall of 1942?

T. Nash Broaddus:

This was in the fall of 1942. I came back in late August of 1942 and went to Sound School at Key West and to SCTC in Miami. In September or October I went to Halesite, Long Island, to pick up a 110-foot subchaser that was being built. Tommy Whitney was the skipper and I was the exec. We finally got it commissioned and fitted out near Coney Island. Then we went to Bayonne, New Jersey, for the final fitting out. I remember they compensated our compass for this one. We didn't have a gyro. We had a magnetic compass and no radar. So we relied totally on the compass for navigating.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have sonar?

T. Nash Broaddus:

We had good sonar on the subchaser (SC) boats.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it have a name or did it just go by a number?

T. Nash Broaddus:

No, just a number. This was late December of 1942. We left Bayonne and headed up the sound for Casco Bay for the final shakedown. Casco Bay was a miserable place to shakedown anything, particularly a wooden SC boat in January. We cleared Hell Gate about dusk. I had the watch and Tommy was down below. Besides being hazy on the

surface of the water and no moon, it was a fairly clear night. Late on the first watch, around nine or ten o'clock, it looked like there was land ahead. I got the lookout and not only was there land ahead but there was also land to the port and land to the starboard! I stopped the engines and called Tommy. Everything was blacked out in those days, so we poked along and finally figured out we had sailed into Oyster Bay, but how, we didn't know. We navigated the rest of Long Island Sound and on into Boston by the stars! We found the North Star and the buoy, so we knew where we were, and we would plot a course to the next buoy. We would use the North Star and have the helmsman steer on the star. When we would get close to where we thought the buoy would be, we would get the searchlight out and find it. This was how we navigated into Boston. We found out that when the schnooks at Bayonne compensated the compass, they forgot to secure the two big iron balls. When we got in the sound and started rolling, those balls were whamming back and forth against the compass.

We had the compass recompensated and fixed in Boston, and took off for Casco Bay. By this time it was January. We hit the most horrible storm I had ever seen in my life. I came closer to dying that night than I think I have ever before or since.

The ship had a pair of GM diesel engines with the big cooling saltwater intakes on either side of the keel.When the ship ran into this blizzard, we began rolling our keel in the water and, as a result, we were getting airblocks and would have to stop the engines. Everybody got so seasick that we had over half the crew lashed in their bunks with the bunks up. The crew was losing consciousness because they were so horribly sick. This was the first time we had been to sea for several months; and a lot of those kids had never been to sea before.

I ended up that night taking the deck, because even Tommy, who was a hell of a good sailor, was sick in his bunk. The gunner's mate was lashed to the helm for about ten hours. The pilothouse was ankle-deep in water, blood, and vomit. We had the yeoman and the electrician's mate as lookouts, and one machinist's mate in the engine room. That was all of us.

Donald R. Lennon:

Everyone capable of functioning.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Able to function that evening. The lookout found a buoy off Portland, just by the grace of God. It was so cold on top of the pilothouse that the lookouts would have to come inside after five minutes so we could break the ice off of them. The bad thing was the ship began to ice up. She began rolling slower and slower, and sometimes we would have both engines out of commission because you couldn't run them without the cooling water. We would just be out there--rolling back and forth, back and forth--until we could get an engine underway. We were getting nowhere.

We came into Portland Harbor that night--during the early morning hours--over a submarine net. We never saw the submarine net. We never saw it and they never saw us. We thought we saw someone signaling us way in the harbor and we tried to answer with the searchlight, but we found out it was just someone with a welding torch. Pulling in alongside the section base, we found a converted patrol craft sinking literally at the dock. We roused up the crew and pumped the water out until the people came to work at the section base that morning. It was a terrible, terrible night. I'll never forget that night. I spent a year-and-a-half in the North Atlantic and I never went through a worse night. I did go through some bad ones, however, on the DE.

The only training we got at Casco Bay was our being used as an icebreaker. Casco froze solid and all we did was break the ice between the destroyers and the tender.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now you said the ship was wooden.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, but there was copper sheeting along her water line and we'd just use it as an icebreaker.

Donald R. Lennon:

Ram your way through it.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Just ram your way. You'd back off, run up on it, and crash in, so that the fifty-foot motorboats and the forty-foot motorboats and the whaleboats could move between the ships. That was pretty much the extent of our training.

We left for Norfolk in January and the ship ran aground off the mouth of the Cape Cod Canal. That winter of 1943 was terrible. There were chunks of ice as big as this room and they had moved the buoys. We ran aground that night and the Coast Guard came out the next morning. They helped pull us off, and took us into a yard somewhere down the sound. It was not as far down as Stamford, but I've forgotten exactly where it was now. The only damage the ship had was some banged-up propellers and a torn-up keelson; however, we were all right and continued on. We had another court of inquiry. We had just finished a court of inquiry for the Harbor Entrance Control Posts as to how we managed to get into Portland Harbor that night with nobody seeing us. It was determined our ship must have literally gone right over top of that submarine net that night. We never saw anyone. But as far as running aground, it was one of the few times anybody ever ran aground, I guess, but there were some extenuating circumstances that night.

We went to Norfolk and then Bermuda to serve on a patrol. There were about six SC boats and about four PC boats that had been converted to minesweeping. There were

also about six gasoline-powered Canadian MLs that had Hall/Scott engines in them. These boats never were able to get underway. We shared patrol duty off Bermuda. It was a very pleasant bit of war--the most pleasant bit of war I fought.

Donald R. Lennon:

Early in 1943, was the German submarine fleet quite as extensive as it had been at the beginning of the war?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I guess they were probably more extensive, but I think we had far better control. The worst time was in mid-to-late 1942 when they literally owned the East Coast and the Caribbean.

We'd be on patrol for a week and on standby for a week. On standby you would usually be at sea. This was mainly going halfway to Norfolk to leave ships and escort them back. It was during this period that we used Bermuda to stage the North African invasion. We met those ships, brought them in for the staging, and then escorted them about halfway to Africa. Then we came back to work around Bermuda.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now I know the SCs were designed to cope with submarines, but you also mentioned the Canadian vessels and other ships that had been converted. Were these vessels a match for a submarine?

T. Nash Broaddus:

They were maneuverable and good escorts because you could sit on a submarine and keep him down. This SC boat first had a three-inch 23- then a 40-millimeter as its main battery in the bow. I believe it had two 20-millimeters mounted aft and quite a few depth charges and throwers. It was quite maneuverable.

The criteria was if a submarine surfaced, you would try to bring your machine guns to bear to keep its crew away from their main battery because they had a larger gun. You would then try to ram them.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking in terms that most of the submarines had two guns mounted on them and if all they had to compete with was these small converted fishing boats.

T. Nash Broaddus:

I'll give you an example. There was a small yacht that was considerably smaller than were we--it was maybe a hundred feet long. The skipper was a good friend of mine named Vaughn Carson. He had located a surfaced submarine that had just sunk a ship off the north coast of Panama. The submarine was firing into the ship. Vaughn came in and opened fire with his three-inch 23-millimeter guns and his machine guns. The submarine didn't know what had him under fire. Then Vaughn came in and tried to ram the submarine, but it dove. He dropped a depth charge on it and found an oil slick coming up and he called for help.

We didn't have anything in the zone except a few old four-pipers and they were even worse than we were because they were not maneuverable. There was a destroyer, however, transiting the canal. It was probably a FLETCHER class carrying the big twelve-hundred-pound depth charges. It came up and saw Vaughn was sitting on top of this submarine, keeping the slick in sight, and dropping an occasional depth charge to let the guy know he was still there. The destroyer came up and made the kill.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking if I were a submarine commander and saw that the only thing facing me was a converted yacht, I wouldn't even consider diving. I would have taken him on the surface.

T. Nash Broaddus:

And you would be wise. But you have got to remember, as I told you earlier, the MOONSTONE looked like a cruiser. She looked like she could do thirty knots alongside. It was a beautiful looking craft. I guess maybe through the periscope they thought the yacht was more than it was.

The MLs were in Bermuda. I believe the designation stood for motorlaunch. They had plywood hulls and were 110 feet, about the same size as a SC boat, but they had gasoline Hall/Scott engines in them, which proved to be very undependable. The MLs were practically worthless craft.

One amusing thing we did in Bermuda was joke around with the operations officer. His name was Commander Gridley and we skippers used to change the Navy terminology to "You may fire Gridley when ready," rather than vice versa.

After SC duty, I was relieved and went to Key West to Sonar School for two weeks and then back to SCTC for another four weeks before reporting as exec of the destroyer, USS CATES DE-763. As was the custom, I met the crew in Norfolk at NOB and went through crew training with the majority of the officers, in particular the junior officers. The commanding officer, some of the higher ranks, the engineering officer, and first lieutenant were with the ship. She was built in Tampa, Florida, at the Tampa Bay Shipbuilding, I guess. It was the second DE they had put together.

We joined the ship, and had trials out of Tampa Bay in the Gulf for a week or two. We commissioned it around Christmas in 1943. Ammunition was loaded on New Year's Eve, 1943, and we headed to Key West for provisioning and then to Bermuda for our shakedown.

I'm sure you've heard about Bermuda and the rigors of Captain Hollowell and his shakedown group in Bermuda. It was marvelous training. It was wondrous how Captain McDaniel trained a bunch of civilians to train us for anti-submarine warfare in SCs, PCs, and DEs at Miami; and it was equally wondrous what Captain Hollowell did in Bermuda to make these combatant ships. The DEs did a lot, they fought a good war due, in part, to the

training forces at Bermuda that whipped them into shape. It was tough, I mean it was real tough.

We left Bermuda heading to Boston and our radar gave out. Of course, by this time we'd gotten dependent on radar. We had no star sights and no sun lines from Bermuda to Boston! We were going DR (dead reckoning) the whole way. I had learned navigation quite well in the MOONSTONE. Bascom Jones was a marvelous navigator--great at dead reckoning.

When we got on the coast off of Boston we ran into thick fog; so we went into Boston by fathometer. We set the dead reckoning tracer and kept counts of the depths on the flimsy. We could slide it back and forth and figure our line of bearing and we hit Boston Harbor right on the nose.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wow! That took skill!

T. Nash Broaddus:

It was fun doing that.

We started convoy duty. We were running what they call the TEs. They were the troop convoys. The CATES was the flagship for Commander Escort Division 35. The Commander's name was John Litchfield and he was a three-stripe who had come from command of a DE to become the commodore of the division. He was a wonderful man. We took him aboard shortly after we got to Boston.

What we normally did was form a convoy out of New York. They were fourteen-knot convoys. Ships that couldn't maintain a fourteen-knot speed couldn't travel with us. There were two convoys: the TEs and the slower convoys made up mostly of merchant ships. There were two sides to that coin. You got it done quicker if you were faster, but you took more of a beating. You could take a pretty good beating in the North Atlantic.

We'd leave New York with troop ships, pick up a contingent at sea off Boston and then go across the North Atlantic. In the early days, we'd deliver them into Londonderry, Northern Ireland. As the Irish Sea became less dangerous, we'd leave the ships in the Irish Sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were taking that extreme northern route off Iceland, Newfoundland?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, it was rough. It would get very, very rough, because we'd have fourteen/fifteen-knot convoys and we'd be patrolling ahead of them at maybe sixteen or seventeen knots. It was unbelievable.

Donald R. Lennon:

How bad was the submarine activity over there?

T. Nash Broaddus:

The submarine threat was worse when we started, but it got better as time went on. It was not as bad when I started in the North Atlantic as it had been prior to the time I got there. By that time, we had radar--pretty good radar--so the "Wolfpacks" had quit. Early on we'd get pretty good determinations on where the submarines were. We'd get a message that there were subs in our immediate area, usually specifying where they were, and then we'd try to steer around them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any particular area of the shipping lane they tended to accumulate in?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. A little better than halfway across. As you approached Great Britain, you had more there than you did near our shores, by that time.

Donald R. Lennon:

Pulled back probably because of fuel consumption.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Could be. But during this period of time, Life magazine ran a cover story on how great it was that we had radio detection finders that could locate the German submarines. They showed where the direction finders were on the perimeter of the North Atlantic, from the northern United States to Canada, Greenland, and Iceland; and described how we could

spot the U-boats when they came up every night to send a report--zero in on them and get a fix for the night. Well, as soon as the article in Life came out, the Germans quit that.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened to security?

T. Nash Broaddus:

How we let Life publish something like that, I don't know.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's what I meant.

T. Nash Broaddus:

It was a terrible breach and we immediately knew the difference; then we didn't know where they were. They changed. Before, they would come up and report in just about dusk at night.

I never sank a submarine while I was out there. I think I sank one in the English Channel later, but I didn't get credit for it. "I didn't bring home the skipper's britches!"

The prime difficulty was the weather and navigation. Litchfield, as escort commander, had the final responsibility for the convoy. The convoy commander was in charge of the ships within the convoy but the ultimate responsibility rested with the escort commander, no matter what his rank. He could outrank even admirals that sometimes were riding the convoys.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, these were DEs. Would there be DDs in the same convoy?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wasn't it unusual for the convoy commodore to be on a DE when you had a larger ship?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, it was unusual but it did occur. Early on, the first convoys typically would have one of the old four-pipe cruisers along for firepower and perhaps a small carrier.

Donald R. Lennon:

There weren't many carriers in convoys.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Occasionally--at first. Later on in the war, we had several of the small carriers transporting planes. They were used as transports to get the planes over to the European Theatre. A division of destroyers was made up of four; the division of DEs had six. Early on we'd have, perhaps, four destroyers, maybe twelve DEs. Sometimes we'd have sixty or seventy troop transports--big ships--all the old Liners.

Donald R. Lennon:

There must have been a lot of troops.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Oh, a gigantic number of troops. Later on we didn't have the destroyers. It was just the DEs. The DEs were really better at anti-submarine warfare than the destroyers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes. That's what I've heard.

T. Nash Broaddus:

They were a much rougher ride, but they were better.

Donald R. Lennon:

Because they were more maneuverable?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, more maneuverable, much less turning circle, but not as stable a platform. They were designed to come back from either 90 or 100 degrees--flat down and back up.

There were several instances when destroyers and DEs were caught in typhoons. The DEs came back, but the destroyers capsized.

I remember the fall of 1944 around September we took the first troops directly from the United States to the beaches of Normandy without having to take them to England. I want to say we had the 1st Cavalry. What was McAuliffe, the guy that said, "Nuts."

We had his group. There were sixty-odd troop transports. We came into the English Channel and the minesweepers had swept us a channel along the southern coast of England and then directly across. We went single line. If you can imagine sixty ships in a single line hugging the coast of England.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looks like you're saying that the DEs were single line rather than the convoy single line, aren't you?

T. Nash Broaddus:

The convoy was single line.

Donald R. Lennon:

Looks like the DEs--your Navy ships would need to be screening along the perimeter.

T. Nash Broaddus:

The logic was that mines, by that time, were a worse threat.

Donald R. Lennon:

Than the subs?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Than the submarines. They didn't have enough minesweepers to sweep more than a single line. We strung those ships out and we had the destroyers outboard patrolling.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the front.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Well, to the side, really.

Donald R. Lennon:

To the side? Okay.

T. Nash Broaddus:

We were in the van, leading. It was night and we were plotting as we came along the coastline, and I realized we were about to run aground. I told Captain Litchfield, "You know, you've got about three minutes and we're gonna run aground." I also told my captain and, then, went down to log out.

Captain Litchfield didn't want to take over from the convoy commodore but he finally did. The convoy commodore was about to pile us on the rocks that night. Then we had the convoy, because once you relieve the convoy commodore, you are in charge. Captain Litchfield recommended they change course, but the convoy commodore's navigator didn't agree. We did turn, however. We were so strung out, literally, by the time the lead ship reached Normandy, the rest of the ships were still coming up the coast of England. We had ships all the way across the Channel. We got everyone there and didn't

lose a single one. We had one of our radios set on the German TBS and we could hear the German torpedo boats. I think, if I'm not mistaken, I made nine crossings. During my career I went through two hurricanes in the Atlantic and two typhoons in the Pacific.

Donald R. Lennon:

The weather was a greater danger than the submarines!

T. Nash Broaddus:

For us. The North Atlantic was worse than any of those, because you knew that a typhoon or a hurricane would be over in twenty-four hours. When you were in the North Atlantic in wintertime, however, you knew that for ten days you would be out there, and it was terrible. We rolled 65 degrees one time in this diesel-electric GM-powered DE.

One evening, when it was rough as a cob, I was sitting in the wardroom on the sofa that ran on the starboard side along the outboard bulkhead. (The wardroom ran athwart ship--across the ship.) I was wedged in with my feet propped up on the beam. There were two officers sitting beside me. We were patrolling. We must have come around and just caught this swell, and those two officers were thrown, literally, like on a slingshot out of the sofa. I can still picture to this day both of them suspended in mid-air right over the middle of the wardroom table! It just flung them! They came down with all the chairs and everything, in a heap on the far side of the wardroom. One of them sprained his ankle and the other one broke a couple of ribs. It was a terrible thing. You just had to hang on all the time.

In order to sleep, we each got two mattresses. What you'd do is you'd pull them up and "V" them into your bunk and then you'd sleep down in the hollow of the mattresses. It was a very interesting experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, I suppose in that kind of weather there was only so much a submarine could do anyway. Her crew was suffering from the same problems.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Of course, they were below the surface. What you had to worry about in that kind of weather, when you were rocking and rolling, was taking in water. I've got some photographs somewhere of the DE with the whole bow buried underwater. The pictures were taken from up above in the radar tower. You can't see anything except the bridge. Everything else is underwater! The DEs were good seaboats. They were great ships.

One time, late in the war, we had a convoy again and Captain Litchfield was escort commander. We left New York with the convoy and it was rough. Early in the morning they woke me up and said that the sonar room was flooded. We had hit something that had rammed the sonar all the way up into the ship and flooded the room. We immediately turned around and went back to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to replace the sonar. While we were in for repairs, nobody could figure out what had happened because the sonar had been hit from underneath and forced up through the deck. It wasn't bent. Two days later, a huge whale was reported to have washed up on the shore near Montauk. What had happened was we had come down on top of a whale! We didn't even know it because it was so rough out there! We were very quiet because the dead whale had caused quite a stink, as you can imagine.

Donald R. Lennon:

Killed the whale. . . .

T. Nash Broaddus:

Killed the whale.

Donald R. Lennon:

And ruined your sonar.

T. Nash Broaddus:

And ruined the sonar.We then got sent to Casco [Bay] for training.

Donald R. Lennon:

I want to ask a question before we stop discussing the North Atlantic. You convoyed the ships over. Did they come back empty?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes, but they were convoyed.

Donald R. Lennon:

They were convoyed the same way back?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Absolutely.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there as great a danger?

T. Nash Broaddus:

There was equal danger of losing the ship. Of course, they would maybe have prisoners of war or wounded on the ships; they weren't full of fresh troops.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was thinking submariners would be more interested in picking off loaded ships going toward Europe than those coming back.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Sure, but if a subman sees a ship. . . .

Donald R. Lennon:

He'd take whatever he gets.

T. Nash Broaddus:

He'd take anything he could get in his sights. But logistically it would have been a more valuable kill when the ship went over than it would have been coming back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you have a layover in England before you started back?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. Depending where we were, we'd stay for maybe three to six days to get a little rest and to make minor repairs, and then we'd come back. We normally went into Brooklyn, although occasionally we would go into Boston. They would usually have to rebuild us because these ships would be torn to pieces. They would pretty well put us back together. One of the ships in our division had its entire bulkhead in front of the number one gun ripped open by the sea. It looked as if a can opener had peeled it.

I remember once when we were in dry dock; I went down to look at the bottom of my ship, and it looked like paper. I could see every rib and every beam in the ship. The

skin of the ship was indented into these things. I then went down into the bowels of the ship, because it looked like it was damaged forward of the bridge. I discovered the two main I-beams on either side of the keel had been bent up from pounding into the seas. I went and got the man in the yard and said, "Hey, this is ruined."

He said, "Nah, don't worry about it."

So we went on back to sea.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was still seaworthy, wasn't it?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, considering the amount of damage the weather and the sea were able to do in that northern shipping lane, wouldn't it have been practical to have dropped down some and have a more southerly lane?

T. Nash Broaddus:

The Great Circle route is supposed to be the shorter way.

Donald R. Lennon:

I know, but I was thinking if you were down where the weather was better you could make better time instead of being beaten and battered.

T. Nash Broaddus:

I don't think so because the big liners, the big troop transports, could maintain speed. That was the only important thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

So it didn't really slow you down that much.

T. Nash Broaddus:

No. It just beat the hell out of us.

The time we hit the whale, we didn't make the convoy. After being repaired, we went to Casco for training. That was the typical routine. We'd go to the Navy Yard and spend almost a week getting the ship put together and then go up to Casco for four or five days and "train." We would go through gunnery practice, sonar practice, anti-submarine warfare, and various and sundry training exercises, which was fine except in the dead of

winter when training in that kind of weather was difficult. I remember when we were up there having gunnery training and it was so cold that whenever we fired our three-inch .50 caliber guns, the recoils would stay open. They would freeze. We would have to rig steam hoses in order to get the guns back into the battery. That was a silly thing to have to do.

When we went up there this time, we spent close to a month. During our training, a submarine appeared off Cape Cod and sank a ship. As a result, all the DEs and destroyers in Casco Bay were gathered up and sent out as a "Hunter-Killer" group. Well, we chased that submarine. He went up off Newfoundland and sank a ship, and we all raced up there. We ran expanding searches. He ran back and forth and sank ships, but we never found him!

Donald R. Lennon:

The "Lone Wolf" tactic.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Really. Litchfield was the senior officer in charge of this thing. One time we thought we had him. We used to run what they called the "creeping attack." If a submarine was deep, you would lose contact; it was like a cone going up. The deeper he was, the farther away you would be and lose contact. That was when he would do his maneuvering. So we developed what was called the "creeping attack," whereas, a ship out to the side--maybe fifteen hundred yards away--would locate the submarine, ping on him, then con another ship in for the attack. The other ship, keeping his sonar quiet, would come in and then you'd throw a pattern. Well, the DE controlled a much bigger pattern than a destroyer. I think either thirteen or seventeen was the normal pattern. We thought we had him for sure. Two destroyers conned us in to throw this "creeping attack." We had depth charges flying all over hell and high water. They started exploding by sympathetic detonation. When one would hit the water, it would explode, and cause the next one to explode, and so forth.

The whole stern of the ship looked like it was underwater and our power was knocked out. We soon discovered we had attacked a closely packed school of red fish! There were dead fish everywhere. I mean thirty-six-inch and forty-inch red fish floating all over the ocean! There we were, sitting there with all our circuit breakers out, looking like fools. The explosion literally threw so much water we were ankle-deep on the bridge, but it didn't hurt the ship. There was no permanent damage.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of report did Litchfield make about that?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I doubt seriously we made much of a report. You know, we'd get false things frequently, but this was a very well executed attack. We were all quite proud of ourselves. We thought sure we had this fellow.

After VE Day, we came back and went to Charleston to exchange our torpedo tubes and reconfigure the armament. I guess they took off our after three-inch gun and replaced it with a quad 40-millimeter and four more twin mounts aft to make us an anti-aircraft-type vessel.

We then went to Guantanamo Bay for shakedown and the damn guns wouldn't fire. Constant breakdown. We were working twenty-four hours a day and the guns wouldn't fire. They had taken these 40-millimeters off a Coast Guard cutter and put them on us, but they had not reconditioned them. I wrote a dispatch back to ComLant saying they were not satisfactory. We were told to turn around and go back to Charleston. They convened a court of inquiry, and I'm sure they would have hung me high by the yardarms; however, while the court was meeting, about four other ships experienced the same problem.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were they doing, claiming it was your fault they wouldn't fire?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. That we had not maintained the guns properly. I was maintaining that the guns hadn't been properly reconditioned before they were put on our ship and I wasn't going to take the ship out to fight kamikazes with guns that wouldn't fire. New guns were put on and we went back out and rejoined the other ships.

We were sent to the Pacific. We transited the Canal and left out of San Diego. We had a very active transit from San Diego to Pearl.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now, were you running alone or were you with other ships?

T. Nash Broaddus:

No. We were assigned to one of the new command ships. These ships were put together to have all the electronics gear needed by the commanding officer to run any operation. They were floating CICs (Combat Information Center). They were transport-type vessels.

This command ship had more brass than I had ever seen in my life. There was an admiral--probably rear--and captains by the dozens. We did exercises all the way from San Diego. This was a new ship just going into commission. I was the sole escort for him. There was not much submarine activity.

Donald R. Lennon:

The Japanese, by this time, had pulled way back, trying to defend the island.

T. Nash Broaddus:

One day the admiral would designate me as a fleet of battleships to attack from over the horizon; the next day, we would have breeches buoy exercises, or fueling exercises. We had every exercise known to man! Actually, it was pretty fun. He designed a game where a ready gun crew could fire a star shell at anytime, twenty-four hours a day, and see how rapidly it took for another gun crew to get a shell up in the vicinity. You know, surprise attack. It was good practice for us.

The real fun started when we got off Pearl. It was late one afternoon. My God, there were so many ships trying to get into Pearl; this was late one afternoon. I said, "We're not going to get in before midnight." I thought this because you had to go into the harbor by rank of commanding officer. We were prepared to wait as all the battlewagons, cruisers, destroyers, and everybody else went in. Well, this rear admiral on this command ship hoisted the signal: Desig 763 Form 18, which meant "Come right under my stern." He took me straight through and all the cruisers had to back off and we steamed into Pearl.

Donald R. Lennon:

Just the two of you?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. He was a nice man. He came over to my ship and paid me a personal visit.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who was it?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I don't remember what his name was, but he was an admiral and was going to be a task force commander. I was his task force. We had a lot of fun on that trip.

I guess we went from there to Eniwetok. It was probably when we were in Eniwetok that Pearl had a false VJ day. Then they later had the real thing.

We went to the Philippines and visited Luzon and Manila. Then we hauled the 1st Cavalry, which were the occupying forces, into Tokyo Bay.

We were then attached to Commander Amphibious Forces Pacific Fleet--ComPhibFor--Admiral [John] Lesslie Hall. His flag lieutenant was Steve Fox, former communications officer of the CATES, and a professor of archaeology at Princeton. People used to call him "Fossil Fox, Doctor of Rocks."

We sailed into Tokyo Bay, escorting the troop ships with the 1st Cavalry, which occupied Tokyo.

Steve Fox was a pretty good arranger. He got us dock space in Yokohama. Our ship was the first U.S. naval vessel into Yokohama. We went in and tied up alongside a bunch of midget submarines. We took a look at them. I didn't dare go down into one, but the sailors went down and looked.

An Army supply ship came in just astern of us at this dock in Yokohama. I had an exec then, Ron Beaman, who'd been a car salesman in California, and was a good negotiator. He went down and traded them some stew beef and meat for a Jeep! Four of us then took off to go see Tokyo.

We got there before the 1st Cavalry did. It was really a pretty astounding place in a lot of ways. The people were very curious. I remember standing on a corner trying to decide what to do and seeing dozens of Japanese just looking at me.

I went into a department store and it didn't have anything. I think I bought a vase. That was about all they had in that department store. They was nothing to buy in Japan then. While I was negotiating to purchase this vase, I looked and saw about twenty-five Japanese standing around me, watching me.

We drove out into the suburban residential areas. There must have been a hell of a good safe salesman. The houses were made out of plaster and chicken wire, but in the middle of every house was a huge safe sitting on a cement deck. All you could see were hundreds and hundreds of safes, block after block.

The Jeep had a flat tire while we were out in the middle of nowhere. There was nobody around and we didn't have a jack. Nobody knew exactly what we were going to do. A gang of fifteen or twenty men came along dressed in parts of uniforms. We had side arms but were still somewhat concerned. They saw the problem and, my gracious, they must

have been a disbanded military group, because this one guy took charge and they went running around. They got some timbers, levered the Jeep up, and changed the tire for us. Then off we went.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you feel any apprehension going into Tokyo or even to Yokohama before the occupying force was there?

T. Nash Broaddus:

We didn't know we were the first ones. We thought the occupying forces had already gotten there.

Donald R. Lennon:

You wouldn't have been so brave.

T. Nash Broaddus:

We wouldn't have been so brave at all! The thing that interested me is how different the Japanese are from us. Had an occupying force come into this country, I wouldn't have been anywhere near as friendly. It was just curiosity. One man took us into his home. It was a combination home and a plastics business. He made little plastic bowls. He spoke English. Everyone seemed very curious.

Donald R. Lennon:

Didn't see any hostility on their (part) after being defeated?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Absolutely zero, which has always astounded me.

We got assigned the unenviable duty of escorting LSTs down to Okinawa to bring supplies back up to Tokyo. By this time I had been at sea for a long time. The Navy had a point system; you got so much for sea duty, so much for service, and so much for dependents. An old chief bosun mate and I were the only people aboard who were qualified to get out and I wanted out. I had fought all the war I wanted to fight and I wanted to get home. I put in for return to inactive duty so I could get home. Well, I got declared a military necessity, which was ridiculous. I had an exec, a full lieutenant, who I had qualified for command back when we were still in the Atlantic, and he wanted to stay in the

Navy for a while. He had been an automobile salesman in San Diego, but he didn't have anything to sell so he decided to stay in the Navy. There was also another senior officer, a full lieutenant, who was an older man--when I mean older, he seemed old as hell--around thirty-five years old. I was twenty-seven. He also wanted to make the Navy a career and had been qualified to be exec. Once a week, I'd write a letter, through the channels, and they ignored me and ignored me and ignored me.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of grounds could they use for that when, at this time, they had all this surplus of naval personnel?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I don't have the foggiest notion, but they kept declaring me a military necessity.

The Navy was coming apart. It was hugely disorganized. Hugely disorganized. I took twenty-five LSTs, you know those huge old hulking things that would go about seven knots, down to Okinawa. By that time, they hadn't been overhauled for God knows how long. We went out of Tokyo Bay in a fog and foul weather. There was a typhoon coming up the coast so we went into a bay just below Tokyo Bay and took shelter.

After the weather cleared, I took the LSTs down to Okinawa. On the eastern side of Okinawa was Buckner Bay; on the western side was an open harbor. I put the LSTs down there to the south to load their supplies, and I went around on the other side to find some fuel, because we didn't have any. I left my exec to beg or borrow some diesel fuel, which he managed to get from some of the other diesel ships. I went ashore to try to find someone to report to. In the meantime, I could not find anyone. I didn't have any orders. I was OTC--officer in tactical command--with orders to take these people down there. That was all.

I came back and found the ship. At the time, we had been plotting two typhoons. Typhoons sort of sweep over, run their course, and head north. We consulted and figured that one of those typhoons was going to hit Okinawa.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those LSTs wouldn't stand much foul weather, would they?

T. Nash Broaddus:

No. We were all still guarding the same TBS frequency, so I got on the radio and said, "I have no orders for you; you are not under my command any longer; however, we think a typhoon is going to hit here. I will escort as many of you back to Tokyo who wish to go."

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what were they supposed to do in Okinawa after you got them down there?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Pick up supplies and take them back to Tokyo. This was the supply route. You see, we had lots of supplies on Okinawa, but nothing in Japan.

Donald R. Lennon:

Had they had a chance to load any supplies by this time?

T. Nash Broaddus:

They had had a day and a half. I said that it was up to them. Eighteen of them decided to come with me. We headed north on the west coast of Okinawa during the early morning hours.

As soon as I got underway, I said, "Alright, convoy speed is ten knots.”

I got all this blinking from the LSTs: "We can't make but eight knots."

I replied, "If you can't keep up, drop back. Convoy speed is now fifteen knots." Well, no LST in the world ever made fifteen knots so I said, "Look, we think this typhoon is going to hit. Make the very best possible speed you can."

They cranked it up to flank speed--wide open--and we cleared the top of that island about the time the typhoon hit Okinawa. Do you know that typhoon sunk more ships than the whole Japanese navy sunk? We cleared the tip and headed southeast. We were trying

to get back to Tokyo, which was northwest. We put the typhoon on our bow and rode it out that day and that night and then turned around and went back to Tokyo.

Donald R. Lennon:

You tried to head out of the path?

T. Nash Broaddus:

We got searoom, so we didn't have to go through the eye of the thing. But it was rougher than a cob. If you get searoom, however, you can ride it out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Those LSTs could ride it out, too? They never looked like they were seaworthy, even in good weather.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Well, they weren't particularly. Practically all the ships in Buckner Bay got sunk. The typhoon hit sometime during late September or early October of 1945.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there no one in command at Okinawa who you could report to?

T. Nash Broaddus:

No. I couldn't find anybody. I spent all day ashore trying to find somebody to report to. Couldn't find anybody.We went back and were based at Yokosuka. Everyone went ashore and I got drunk as a coot. By this time, I was very sick and tired of being in the Navy. I mean, children that had come aboard as ensigns were going home because they had enough points. So I was letting everybody go that could go. I came back aboard ship that night and I went into the radio shack next to my cabin and sent an operational priority dispatch. You know, you only send that in wartime. That's just this side of urgent. Urgent is the most. I sent an operational priority dispatch to the chief of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Commander Pacific Fleet, Commander Destroyers Pacific Fleet, and Commander Amphibious Forces, for whom I worked, "Requesting immediate release; Lieutenant Commander Thomas N. Broaddus to inactive duty." I figured I was going to get out of the Navy one way or the

other. Either they were going to court-martial me out or they were going to let me out and send me home! You know, I got return dispatch orders.

Donald R. Lennon:

They took you seriously that time!

T. Nash Broaddus:

They took me seriously that time. I got return dispatch orders and I came on home.

I came home on a slow carrier that had fought a long hard war. It must have had marine growth on its bottom. We had a regular Navy skipper who sort of nursed the ship home, because the Navy had told him he was going to be able to take his ship to dry dock and have some R & R for his crew. It took us close to thirty days to get back across the ocean. When we got about a day out of Pearl, they were going to fly the planes in and leave those at Pearl. I bummed a ride on one of the torpedo planes. I wasn't supposed to, but my friend Steve Fox and I were going to have a party that night at Pearl. It was interesting, because I had never been on a carrier takeoff before.

Then the skipper found out he was going to have to turn right around and go back to the Pacific, so he went from Pearl to San Diego at flank speed. He didn't care anymore I don't think. He made pretty good time there.

I got out and went to Camp Pendleton, the separation center there. I had bad sinus problems. Anyway, I needed an operation and wanted to go into the Norfolk Naval Hospital.

At first they were going to put me in command of a troop train to bring a bunch of troops back across the country. I objected violently to that idea. It was a pretty bad scene. Things almost came down to fisticuffs; however, they did give me four days to report to the Naval Hospital. Transportation was impossible then, but I went out to the airport and

managed to sweet talk my way onto an airplane. An old DC-3 that hopped all the way across the southern part of the country. We must have made twenty stops.

I got back, and then I got out of the Navy. I left college to go into the Navy; I was a good navigator; I was a good skipper and exec of ships; but I didn't have any other qualifications. I had spent over five years in the Navy and now I had to go find myself a job.

Donald R. Lennon:

At a time when literally thousands and thousands of other men were looking for jobs.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Men who had already gotten back, long before I did. I got back at Thanksgiving. I went into the hospital and then took off through Christmas. Then I started job hunting. I said, "The best things I've got to help me hunt for jobs are my fitness reports." I had good fitness reports. I had been a good Naval officer. But when I tried to get them out of the Navy, they said, "No way."

A friend of my mother's had been a congressman and another good friend was the admiral who went on to become head of the Atomic Energy Commission right after the war. I can't remember his name, but anyway, he suggested to the Navy Department that it would probably be a good idea if they would provide me with my fitness reports. And they did. I guess that's the first time that they'd ever done that, but they were my records, and I didn't just want them, I needed them. I got those copies of the fitness reports and I used them as my resume to go job hunting.

I searched madly. I went to Wilmington, Delaware, to visit a former skipper and had an interview with Atlas Powder Company. The former skipper suggested I apply at the DuPont Company. He had a friend, Dr. Benger, who was head of the research end of

textiles; so I went down and talked to him. Here I was with only three-and-a-half years of college and they were hiring nothing but Ph.D.s in chemistry in those days.

Dr. Benger said, "I don't know what the hell I'll do with you." They had a development section, so he called in the assistant personnel manager and said, "Set up some interviews for this boy." The man who was the head of the development section, Roy Horsey(?), had been assigned the task of preparing a performance review form for the DuPont Company. When I showed him my fitness reports, he was fascinated. They didn't have copying machines in those days, so he said, "May I make a copy of this?" He wasn't interested in me; he was interested in the forms.

Donald R. Lennon:

In the forms!

T. Nash Broaddus:

Exactly. It was late in the afternoon by the time I got to see Roy Horsey(?), and he said, "Why don't you come back tomorrow and I'll arrange some more interviews." I had some more interviews the next day--I guess that gave him enough time to copy the fitness reports!

Well, by that time, I guess I had impressed enough people, because when I went back the second day to the personnel man, he was astounded that they had decided to offer me a job. He said, "My God, I can't believe it."

It was the only job I interviewed for that I really wanted and I ended up spending twenty years with the DuPont Company. It was very successful.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, you had to memorize the eye chart in order to get into the Navy officers' training program. Did that vision problem haunt you at any time during then?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Well, the main place it would haunt me was when I had to take a physical, which I had to take every time I got promoted. Well, every time I had to take a physical, my pulse

would go way up because I was afraid they would have a different eye chart, and I'd fail the pulse rate. I'd say, "Well, let's go on with the rest of the examination." I'd get to the eye chart and I'd say, "Well, let me rest for a few minutes." By then my pulse would come right on down.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was the same chart all the time?

T. Nash Broaddus:

The Navy never changed the chart!

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, now, you didn't wear glasses?

T. Nash Broaddus:

I wore glasses later in the war. With binoculars, I've got very good eyes. I could see as well as anybody on the ship.

Donald R. Lennon:

But I know many a well-qualified Navy man who went through four years of the Naval Academy and got washed out because of their eyes.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yeah, I know. Well, they should have memorized the chart!

When I got called back in the Korean thing, I was working in New York. By that time, I was pretty well fed-up with the Navy. They didn't even have my change of address. I had moved a couple of times with the DuPont Company. I had been in Wilmington, moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, and now I was in New York. By the time my orders finally caught up with me, I was AWOL. I should have reported to Charleston for a physical examination two weeks before I got my orders. I had just rented a big house in New York in Manhattan. We had been on vacation for two weeks and when I picked up the mail I saw the orders. We had to stop everything. I called and the man answered and said, "Well, go to Ninety Church Street."

I went there. I said, "That eye chart, you've got to get it close enough for me to feel."

The doctor said, "Don't worry, we'll give you a waiver."

I said, "I don't want a waiver."

He said, "You've got a waiver!"

So, they waived my eyes. Then I contacted the Bureau of Naval Personnel and they said, "Well, yes, you can come to Washington and plead your case." I went down to Washington to plead my case.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now is this in 1949?

T. Nash Broaddus:

No. This is in 1951.

Donald R. Lennon:

1951, that late.

T. Nash Broaddus:

As I recollect, the Korean War started about 1950 and this happened in the early summer of 1951. I figured I was home free. I went to Washington to BuPers. They said, "Well, we convene a court of inquiry everyday at 1300. If you want to appeal, go see Captain So and So. He's the judge advocate; he's your lawyer. I went down to see him. They had really picked a good one. This guy had been a lawyer, had seven children, and was just getting started back in practice. He pleaded my case. DuPont had said they would declare me a military necessity. The guy said, "Fine. They'll tell DuPont they have three months to find a replacement for you."

I went to the destroyer desk officer and he said, "There's no way you're going to get out of this." I was quite junior. When I was skipper of the DE during the war, I was only twenty-five years old. At that time, I was the youngest commanding officer of a major war vessel in the Atlantic Fleet. They used to rank the ships so you'd know what order you went into the port. The DE was the smallest major war vessel listed you know.

I was quite junior. I was a lieutenant and got a promotion because I was commanding officer of the DE. I think there were twelve of us in the whole Navy with command

experience who hadn't made commander. Everybody else had made commander. They called all of us back to send to sea as execs for regular Navy battleship sailors who were being given command of the destroyers and didn't know how to run them. It was a miserable damn experience.

I tried mightily to get out. I remember I said to the guy, "I can't see the eye chart." He said, "Don't worry, we'll waive that."

"I've got high blood pressure."

"We'll waive that."

It didn't make any difference what I had as long as I was warm and was ambulatory, I was back in.

Donald R. Lennon:

I didn't realize that there was that great a shortage of Naval officers in Korea.

T. Nash Broaddus:

There was a shortage of people who had command experience. The exec of a destroyer is a lieutenant commander's job. Well now, there were a lot of commanders, but they didn't have command experience.

I always objected with the Navy on that. I went in around June or July of 1951 and a year later they made me commander, but they made it effective as of March of 1951, which was before I had even been called back. At that point in time, I had too much rank for my job, so then they gave me three choices:

(1) I had five more months to stay in. I needed seventeen months and I had already served twelve. They said, "We'll find a commander's spot ashore.”

(2) “If you'll sign on for another year, we'll give you command of a 2200-ton destroyer;"

(3) "You can go home now."

I said, "Let me out. Let me go home." So I got out. I only served about a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what kind of duty did you have during that year?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Exec of a 2200-ton destroyer.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were you?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Well, the guy at the assignment desk in BuPers did one thing for me. He said, "You can pick your ocean." I said, "Fine, give me the Atlantic." I got lost in the Pacific trying to get home the last time and I didn't want that again. So he gave me the Atlantic. I was assigned to a destroyer that had just come back from Korea after having been all shot up. She was in the Navy Yard. It really was a worthless sort of thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you didn't have to go to Korea.

T. Nash Broaddus:

I did not go to Korea. I operated the ship off the Atlantic, working out of the Navy Yard in Norfolk in the beginning.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were ships in the Atlantic doing during the Korean War?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Actually, they did a hell of a lot. We kept the Mediterranean Fleet and then we had a small fleet on the Atlantic coast. I got out just before this ship went for the ES tour in the Mediterranean.

Donald R. Lennon:

And you were primarily along the coast?

T. Nash Broaddus:

Yes. Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Maneuvers and training and things like that.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Shakedown.

T. Nash Broaddus:

Shakedown, Guantanamo Bay and all that kind of stuff.

Let's backtrack a minute. After the war (World War II), I was in Wilmington, and my ex-skipper said, "Come on, there's going to be a meeting of male reserve officers. Come on down. We're just going to have cocktails." So we went down to, I think, the YMCA in Wilmington. There was this sharp-talking, nice guy, named Captain Dravo. He was on active duty. He had never been to sea. He was a civilian that had been made a commander in ONI. He was a smooth talker and he said, "Well come on now, we want you all to help us get the Naval Reserves started."

The Navy had done a lot for me. They made a man out of me. I went in a boy and came out a man. You become a man pretty quick when you command ships. It's a maker or breaker and I saw a lot of them break. By that time I had gotten over being mad at the Navy for not letting me pull out of the Pacific. I went down and the first thing I knew, I was executive officer of this battalion that we were forming! This was the beginning of the Naval Reserves. It was the spring of 1946. We worked very hard and we ended up commissioning the first Naval Reserve Armory in the country! Big hullabaloo and so forth. We did that, I guess, in May. Then all of sudden comes June thirtieth and a budget crunch, and Dravo and a couple of other officers who were on active duty all got sent to inactive duty. I ended up in command of the battalion! I had two Reserve divisions in Wilmington and one we had formed down in Dover, with about two hundred men per division. I had one jg regular Navy in Wilmington, maybe twenty enlisted personnel on active duty to run the armory, and another fifteen or twenty plus a chief as keepers on the PC we had tied up in the Christina River. The river wasn't as wide as the ship was long. We had to run the bow in the mud bank to turn it around.

Here I was attending two divisional meetings a week, one on Tuesday night and one on Thursday night; attending battalion meetings; working all weekend; plus trying to earn a living. Lammot DuPont was chairman of the board of the DuPont Company and one of the officers on my staff of the battalion was a Lammot DuPont, Jr., who was much older than I. I was quite young to be commander. Here I was the head of the Navy in all the state of Delaware. Of course, it's a small state.

About a year and a half later, DuPont offered me a new job, which meant a transfer to Charlotte, N.C. I loved the job I had; I didn't really want to take the new job; but it was the quickest way I could get out of this Navy thing!