| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

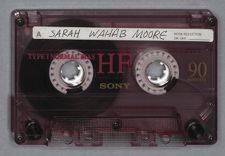

| Mrs. Sarah Wahab Moore | |

| December 16, 1995 | |

| Interview #1 |

Zara Anishanslin:

Please tell us a little about where you are from and who your parents were and that type of thing.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, I'm from Belhaven. I was born here in 1919 down the street. The most exciting things in my childhood were the Sunday school picnics. They were terrific and so was the Christmas party at the church. Believe it or not, I don't remember very much about my childhood. I remember the pleasant things. When we were in high school, every girl had to know how to dance, so we would meet at someone's house--we had a wind-up Victrola--and learn how to dance. I was a wallflower. When we had dances at the Community House, my mother would say, “Now, Howard, you take Sarah to the dance.” He did. He didn't mind. We would have a good time. Everybody danced.

That gives you my background, believe it or not. I can't tell you anything else about my childhood. Then, I decided to go to nursing school with a friend in Baltimore.

Zara Anishanslin:

Why did you decide to become a nurse?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, my mother wanted me to be a teacher, but I didn't want to be a teacher. My friend was going into nursing so I decided I wanted to go into nursing, too. I had no idea what I was getting into. We applied at Union Memorial in Baltimore and were

accepted without an interview. When we left Belhaven, she and her mother and I boarded the Old Bay Line in Norfolk. We spent the night on that line. There were three of us in a little tiny stateroom. The country was in a depression, so although we could smell the food from the dining room, we ate the lunches we had taken with us. When we got ready for bed her mother said, “Well, I'll get on the top bunk because the lower bunk is larger.” We couldn't push her up there, she was quite heavy; so she had to sleep on the lower bunk and I was on the top bunk. I'll never forget it. I wrote in here [diary] that there was one chair, a chamber pot, and a lavatory. We just laughed and laughed. We docked the next morning at 6:00 a.m. at Light Street on the waterfront of Baltimore. There were horses and carts out there. They were delivering produce and ice. It was a cobblestone street and we'd never seen anything like that. Then we went to the Emerson Hotel, which was “THE” hotel in Baltimore. Her aunt had an apartment there, so that's where we spent the night. They didn't know what to do with us, so they sent us to a movie. We saw Ella Fitzgerald on stage. She sang, “A Tisket, A Tasket,” and we thought we'd gone to heaven coming from this little town.

The next morning, we reported to the hospital and from that day on, my life became regimented. It was really a private hospital. We only had two wards, a men's ward and a women's ward. We were issued our uniforms, and assigned to a room--our own room! It was a real nice place. Before we went to duty in the morning, we had to go to chapel. I don't know whether people today have anything like that or not, but we went to chapel, then to breakfast, and then we went to work.

Zara Anishanslin:

Was it a large school? How many of you were in there?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, it was a large school. It was a three-hundred-bed private hospital. I guess there were about twenty of us in my class and all of us passed the State Boards. The day we went down to take the State Boards, after we finished, we went to a movie to see Clark Gable and Mae West in Klondike.

I mention in here that I had met Al Capone. It didn't impress me, because at my age, I really wasn't keeping up with news. He was at the hospital because there were fewer exits at Union Memorial than over at Johns Hopkins, so his doctor treated him at Union Memorial. Everyday, two trays went to his room and we just couldn't understand how people could clear a tray like those two were clean. One was for his bodyguard, I found out later. I guess that was just about the most exciting thing.

One day we took the streetcar down to North Avenue to a movie. When we came out, people were yelling, “Pearl Harbor has been bombed.” So, we were at war right then. We had just graduated from nursing school. The doctors were trying to recruit nurses, because they were joining hospital units. Honestly, they were at the door every time we went in and went out. Some of us went down to the University of Maryland Hospital, to their auditorium, and we really didn't realize what we had done, but we were sworn into the Army. My mother had said, “You don't want to join the Red Cross, because you might have to go to war.” I thought, How am I going to tell them what I have done, when I found out what I had done? They started giving us immunizations, so I knew we better get our ducks in a row. We left Baltimore in April, I think, and went by train to San Francisco. We stopped at Fort Riley where we were

issued all our equipment. All I remember about Fort Riley is that the wind blew constantly. It absolutely annoyed us.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did they give you any additional training?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It seemed like they didn't have time. The whole country wasn't organized. They only had limited equipment, really. We had no training. I don't recall any at all. I know the first night we were at Fort Riley, we were billeted in a hospital ward where there were a lot of beds. I had always said my prayers on my knees. That's the way I was brought up and that's what I had done. There were only two of us that got on our knees, however, so the second night I sat on my bed and did that from then on.

When we arrived in San Francisco, we went to hotels. We hadn't been paid. I don't think I had but a penny in my purse and another girl also had just a penny. The first morning, we ordered breakfast and there were five of us who devoured it. Luckily, they brought enough toast and everything so that it was enough for all of us. That was in the days of plenty.

Before we sailed, we went by cable car to the Presidio, an army base. We went in this building to choose our uniforms and our shoes. There was this pile of uniforms higher than this ceiling and we had to find our skirt, our jacket, our cap, and our shoes in “our size.” If you wear a narrow shoe, you know what that was like. We had a time. My skirt fell off, but they told me I had to go on and take it. I took it and we were going to pin it, but the night before we sailed, they sent me across the street to a tailor and he took a seam down the side which made the backside fan out. I thought, This is terrible! We all had a pair of slacks. The Army wasn't accustomed to that many women in the

Nurse Corps, particularly all at one time. They just didn't have enough uniforms really. They gave us a wool cape, a wool skirt, and a wool jacket, and then sent us to the tropics.

Zara Anishanslin:

I'm sure the wool cape came in handy at Fiji.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

They came in handy in New Zealand. It was winter there. We boarded the ship one morning and there were all these troops already on board. There was an officer standing there on the gangplank with a swagger stick. I didn't know the purpose of a swagger stick, so we didn't know if he was going hit us or not. We didn't know what in the world was going on. We were really stupid, but we boarded the ship anyway. It was a converted liner, the USS URUGUAY. We were lucky that time. There were only twelve to a stateroom. When we crossed the equator, they had an initiation ceremony on deck. We had boat drills, I'm almost certain, everyday. My life jacket was one that circled my waist, but it wouldn't inflate. So, when I was on deck, I just sat on it. Everybody just sat on their life jackets.

We zigzagged to Auckland, New Zealand. New Zealand had been at war the length of time that England had been. Of course, we were in the southern hemisphere and it was winter time. When we got there, they didn't have room for us, they didn't know what to do with the women, so we were billeted in private homes. Two of us were billeted in a lovely home. The owners had been around the world three times. They had oriental rugs all over their home. Their home overlooked Auckland Harbor, which is a natural harbor and a beautiful place. Well, we were both ill. I guess we caught it aboard ship. I know that I was working in the dispensary giving

immunizations for days and that's probably where I caught it. My friend was on the sun porch and I was in the bedroom and we were both sick and quite ill. In fact, my eyes wouldn't even open in the morning. I had such a terrible case of conjunctivitis that the lady of the house had to come in and compress my eyes before I could even open them. Then she would bundle me in my cape and I would go sit in the sun on her front marble steps to get warm, because they didn't have enough fuel. At 5:00 p.m., they would light a fire in the fireplace. I could hardly wait. They served wine at the same time. Of course, we weren't used to drinking wine, but it felt so good going down. In the evening we had mutton and mint jelly and cabbage--I think it was cabbage, it was some type of leaf they had--and that's all they had to give us. Before we left, we were paid and we donated our money toward a daycare center. I think maybe the money built a room. I can't remember how many women there were, sixty-five, I think, though it might have been more.

Zara Anishanslin:

So the New Zealanders really welcomed you all.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. They were at war. If the Japanese had taken the Fiji Islands, Australia and New Zealand would have been cut off from the United States. They would then have had to travel down the Atlantic, go south of Africa, and cross the Indian Ocean, so they were real happy to see us.

We went to a movie one evening in Auckland and before the movie started, they played the national anthem and everybody stood up. Of course, we didn't know that was going to happen. Live and learn. Then at intermission, they had tea.

Zara Anishanslin:

Really?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. They had tea. I guess they really know how to relax. We just go at such a fast pace. The day we boarded the ship to go from Auckland to Suva, Fiji, was a happy day, because the ship was a converted liner and had steam heat. Only one ship could dock at Suva at the time, so as many troops as the ship would hold were aboard, along with the hospital unit. It took three days to go from Auckland to Suva. Of course, we had a boat drill the next day. When I went up to my boat, they had boarded up that deck and no one could have gotten off, even with life jackets. What good would they do you? Well, anyway, the crew said, “Well, we can't lower the boat, so you might as well leave.” We left and went back to our room. We had two meals a day, breakfast and supper. Some were very seasick, but not as much as they were on the trip from San Francisco to Auckland. As soon as we could go outside aboard deck, I went.

Zara Anishanslin:

Were they preparing you at all for what was in store, or was it just basically a voyage?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We knew we were going to New Zealand, but we didn't know anything about Fiji yet. They weren't doing too much talking. There is an article in here that was written by a reporter, either for the Washington Post or the Baltimore Sun. It seems that the Battle of the Coral Sea is what interfered with the Japanese going to Fiji. So, we were lucky. When we did arrive in Fiji, they had trucks to transport us to the other side of the island where the hospital was going to be. I know the trucks had a canvas side and a seat on both sides. If I'm not mistaken, it was about 170 miles to the other side of the island. What scenery we could see while in the truck was beautiful, because Fiji was not a commercialized island. It was very natural and prettier than Hawaii.

When we arrived on the other side of the island, we were set up in a school house, a one-room school house. They had built some showers out back, so we were comfortable. We had, I think, two meals a day. We probably didn't need but one. The Fijians would summon us to a meal by taking two sticks and banging on a hollow log. I think it was called a “lolly.” That gave us something to do. We would go over to the dining hall where we were served mutton . . . and mutton . . . and mutton. We also had taro, which is the root of the elephant plant. That's their basic food.

Zara Anishanslin:

So, you didn't have army rations then?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh, no. They told us, “Don't eat the bananas.” What could they have done to a stalk of bananas?

Zara Anishanslin:

They were worried about sabotage?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Sabotage, yes. While they were setting up the tentage for the hospital, they didn't know what to do with us, so they told the sergeant to teach us to march. He took us over to the field right near the dining hall, and there were frogs everywhere. We didn't learn to march! Then they had this physical therapist give us exercise classes, and we exercised and we exercised. Finally the tents and the hospital were up.

When we arrived in New Zealand, the New Zealand band played the “Stars and Stripes Forever,” and the 37th Division band responded with “Roll Out the Barrel,” and that made us instant friends. Then we were told to line up and they yelled some commands to us, “Right Face.” I turned right. We had on our helmets and all our gear. It was very awkward. I turned right and the other one was turned facing me, so I know we were an embarrassment to the commanding officer, but we had had no training.

Zara Anishanslin:

It sounds like they didn't drill you much.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

They didn't. They did take us out once in San Francisco on a pier, but it was very foggy and they were afraid they were going to march us off, so they stopped that. They didn't have room aboard ship to teach us anything.

Zara Anishanslin:

You said that their attempts to train you in Fiji weren't all that successful, either.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No, there were too many frogs. It was frog season.

Zara Anishanslin:

How long were you in Fiji before you first started getting patients at the hospital?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It was probably about three weeks.

Zara Anishanslin:

What was your typical day like once you started having patients, did it change a lot?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

As soon as we were set up, we received patients. It was officially opened on July 11, 1942. Our new home consisted of three rows of tents for the women. One of the corpsmen gave me an orange crate, so that was our main piece of furniture. He also gave me a large lard can that had a hole in one corner for water. We only had one spigot for the whole area there. I think the men had a spigot where they were. Whoever was off duty would run down to the spigot and fill that can and run back and fill the helmets, because that's all we had at first, just a helmet for bathing. That lard can was very important. One morning, someone had taken our water. We knew who it was, but they never did it again. The latrine, which was down at the end of the row of tents, blew in one morning. Of course, they had guards guarding the whole area. This one guard was

real comical. He said he enjoyed guarding our area so much that he asked for an extra eight hours of duty. I would be out there with my cup and brushing my teeth and he would walk by. It was really weird.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you all interact much with the soldiers, beyond just the ones that guarded you?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, no, but you see, they worked in the wards. The nurses in those days didn't do all that the nurses do today. We had a lot of corpsmen that took care of patients' personal needs. We bathed them, but they took care of their personal needs. It's entirely different today, I think. We were taught to do everything with dignity. That was stressed in nursing school. When we watched our first autopsy, it was done with dignity! I'm certain when we weren't in there, it wasn't done that way.

The first group of casualties, we were told, numbered 800. I read someplace that it was actually 750, but it seemed like 8,000!

Zara Anishanslin:

There were how many of you, sixty-five?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We had 42 doctors, 65 nurses, 375 enlisted men, 2 Red Cross people, and a physical therapist.

Zara Anishanslin:

So then, 800 or so casualties was a lot of people.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, it was a lot. Most of them had wounds and all of them had malaria. The island of Fiji didn't have the anopheles mosquito so we didn't have malaria. It was the perfect climate. These casualties came to us from Guadalcanal up in the Solomon Islands.

Zara Anishanslin:

What were the typical duties of the nurses? Did you just assist the doctors?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, we made rounds with the doctors. We also gave all the medications. We didn't have a pharmacist who prepared the medicines and took them to the ward. If we had solutions to make, we made them. We were pharmacists in a sense. We didn't have antibiotics. We did have sulfa, but that was specifically just for kidney infections. We would have a long list of treatments. A lot of these soldiers from the islands had what we call “jungle rot.” They had ulcers on their legs and they were very difficult to clear up. We used compresses, but more that anything, it was just plain care that helped them. They all had malaria and we didn't have quinine, because that came from Asia. The Japanese had all that. They were treated with Atabrine. When they started the Atabrine therapy, they were more or less doing some research on the cure, so one section would get a certain amount of Atabrine and another one so much and so forth. You could always tell which patient hadn't taken his pill, because he wouldn't turn yellow. Atabrine turns you yellow.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did all the nurses pretty much do the same thing?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, we had a surgical section with surgical nurses and we had a medical section with nurses treating the cases that were medical. Even though they were medical, they still had “jungle rot.” We also had a psychiatrist. It was a general hospital and we did everything that was normally done in a general hospital.

One of the nurses became ill. She was a scrub nurse in surgery. My friend called me on duty and said, “Louise is sick, real sick.” That was about five o'clock, and by nine o'clock she was dead. She had meningococcal meningitis, which is deadly, and we didn't have any antibiotics. Fortunately, no one else had it.

Zara Anishanslin:

That's strange. That was the only case?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

One case. The funeral was so sad. It was held in a small military hospital overlooking the Pacific. Her family had her brought back to Maryland, but I think she would have liked to have been right where she was. It was so pretty over there.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you have much more sickness among the hospital staff or was that pretty much the only case?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No, we didn't have any sickness that I remember. I had pain in the right lower quadrant and it turned out that I had a supernumerary kidney. It didn't quite divide, but if it had divided, it would have been a third kidney. No, people weren't sick. But, one of the nurses did have dengue fever. The synonym for that disease is “breakbone fever.” She was really sick, but she was the only one who had that.

Zara Anishanslin:

Were most of your patients American soldiers?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I would say 90 percent were American soldiers. We also had New Zealand soldiers and Fijian soldiers. One Fijian who was being treated came up one night and said, “I want to show you something.” (Of course, they were English speaking.) He had a handful of gold teeth and I said, “You took them out of some dead soldiers?”

He said, “No, they were alive.” That's what he told me. The Fijian soldiers wore boots, because they were soldiers, but when they were up in the islands, they were good because they didn't wear the boots. They knew how to walk and creep around.

Zara Anishanslin:

They were probably used as scouts.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, I guess so. They were trained by the New Zealanders.

While we were in Fiji, Eleanor Roosevelt came through to visit the islands. She was the only dignitary to hit the islands. We didn't have Bob Hope or any of those people.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you get to speak with Eleanor Roosevelt?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No, she was accompanied by the commanding officer. She was there primarily for the patients. She didn't speak to me. She might have spoken to somebody on another section, but not on my section.

In November of 1943, we received five hundred survivors from the CAPE SAN JUAN. It was a transport that had been torpedoed early in the morning. I saw my brother. He was an engineering officer on that destroyer. They rescued him and he also pulled someone out the water from Belhaven.

Zara Anishanslin:

Really?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. He was in the Navy.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you keep in touch with him at all? Were you able to?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, I'd write to him. It might take him six months to get the letter. He found out I was there and he came in when the doctor came back. I had one can of milk that someone had given me--I know someone took it out of the dining hall. We had no stores, so where would it have come from? Somebody had cocoa, so we had chocolate milk. That's all I had to offer. The Navy usually ate very well, but during the war, they didn't. I think they were short of food. They didn't have supply ships. They would have to go into ports, say in New Zealand, to get food. We didn't have good food. I'll tell you that.

I was on night duty with this patient who claimed to be a free French fighter, a real tall stately person, who had had his gall bladder removed. We were in a building then and the surgical cases were in the surgical ward. We had about four rooms to put the real sick surgical cases. He was in a room with a New Zealand officer and I knew that the New Zealand officer's pulse was just too rapid. I had no idea what was wrong with him. I knew he was ill, but I didn't understand it. Well, this other patient went out on pass and when he came in, he was inebriated and that's taboo in a hospital during the war. We couldn't have that. Then, he pulled out a pistol and he spoke German and there we were at war with Germany. So, one of the Fijian patients was standing in the dark in back of me and he was protecting me, but I didn't know he was there. I was real blasé about everything. I went in and I said, “Well, you know you're not supposed to have a pistol in a hospital.” I went in and took the other patient's pulse again and it was just racing and I thought, Boy, I know now why it's racing! We reported it and the next morning, they whisked him away and we never heard from him again. I imagine they took care of him, don't you?

Zara Anishanslin:

So, you think the New Zealand officer knew he was German the whole time.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I think he knew it and was scared to death. Well, I didn't feel very safe; I was just real blasé.

Zara Anishanslin:

It sounds like you handled it well though.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, what could you do? There was no one there, but I didn't know that Fijian patient was back there.

Zara Anishanslin:

Were you all worried on Fiji about security? Was it fairly secure?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We weren't worried. We didn't get any war news. We really didn't know what was going on. When the commanding general who was in Australia knew that a hospital unit had landed in Fiji he nearly had a fit, because there were women. They must have known that Japan had Fiji targeted after Hawaii. In fact, we were on the ocean, sailing, when they were planning this invasion. I think in World War I, the Japanese were on the Fiji islands, and I guess they had all the maps and everything.

Zara Anishanslin:

So you all weren't scared?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We weren't scared, because we really didn't know what was going on. We really didn't. The patient said he was a French fighter with the resistance. I remember he dressed up in his French uniform one time and somebody took his picture. That was before he came in inebriated.

We had a club. We would meet at the bottom of the road if we had a date and we all walked over together. Here I was a wallflower, but there, I could have a date every night. We'd walk over to the club together, because not everybody had a flashlight. The club had a thatch roof like the natives had. The wall just went up half way and the rest was open. We would dance. In one little Navy club, somebody had a radio, and we'd wait until Tokyo Rose came on to broadcast, because after she was through with her broadcast, she'd play the most popular music from the United States and we'd dance. We waited for her whenever she was broadcasting. She came on every night with an American accent. I don't know much about Tokyo Rose. I've never read anything about her. I think there must have been more than one person, because how could they broadcast that right in that area, when she would be broadcasting in another

area. They didn't have that type of communications, so there had to be more than one Tokyo Rose, but she announced herself as Tokyo Rose.

Zara Anishanslin:

So she was pretty popular?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. We waited. Occasionally she would mention a name or something about a troop movement--that could be a little eerie, realizing that she knew about it.

Zara Anishanslin:

When you went to the club, was this with mostly the doctors or officers?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh no, they were from other units, the Air Force, Coast Artillery, engineers. Most of the doctors were married. We weren't interested in going out with anyone who was married. If we had a dance, we'd dance with them. That was the only thing you could do.

In September of 1944, our hospital was transferred to Calcutta. We sailed on the RANDALL, GENERAL GEORGE M. RANDALL, and the sister ship, the BILLYMITCHELL, accompanied us. The BILLY MITCHELL, however, had some problem and it slowed us down, but we did have a destroyer escort. One day our destroyer escort blew the alarm. I don't know whether they sighted something or not. It was either a whale or a submarine. The ship started going around in a circle. It didn't last too long, and we didn't see any oil or anything. All we did was sit on our life jackets. There wasn't anything we could do.

We were in a storm in the Tasman Sea, on our way to Calcutta, and we went right with the storm. It was terrible. I'd go out on deck in the morning and the sky would be black, the sea would be black, and, of course, the whitecaps were real white. It was really fascinating. When the rudder would come out of the water, the ship would

just shake and the light fixtures would fall off the ceiling. That was some storm. We went right with it, but we lived through it.

One night, when we were approaching the harbor of Bombay, they said, “If you look, you'll see a line of demarcation. It runs a mile from shore, because of the pollution in the water.” I don't know what it is today.

Zara Anishanslin:

Was it different from Fiji?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh, yes. I should say it was.

Zara Anishanslin:

How was your hospital in Calcutta compared to the hospital in Fiji? Was it basically the same set-up?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, it was basically the same set-up. It seems like we had more wards. We had patients that came down from Burma. One day this general came in wearing a campaign hat. It was a hat with a brim, and he wore spats. I'd never seen anybody dress like that. He came in and said he wanted to see the patients from Burma so we showed him where they were. Those patients from Burma wouldn't even talk to us.

Zara Anishanslin:

Really?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I guess it was what they called “battle fatigue” in those days. They were just worn out. He went to see all of them. In that same section, we had a Chinese patient. He had had a leg amputated. One night they couldn't find him at bed check. (We had bed check at night every so often.) He was back of the ward cooking a chicken. You know, their culture is so different from ours. Then another Chinese patient had to have a tooth extracted. He motioned to the dentist that he wanted him to pull them all out. Their thinking was entirely different. Their culture was different. He wanted a chicken

so somebody took him a chicken. Now, he had just had his leg amputated. Can you see someone in America doing that?

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you eat Indian food in India?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No. We had rations. We had our own military rations that the supply ships would bring in, but the food was terrible. We would put the food out in a dish for the children that would come up, but they wouldn't take it. If we put it in the garbage can, they would take it. So, we tried to place it in there for them. There was so much poverty and so many snakes.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you have a lot of interaction with British soldiers in India?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No.

Before we arrived, we were given a lecture about the dangers and so forth in India. They said, “Now, when you board the train, you'll pass all this twisted metal. Some soldiers were talking when they weren't supposed to and gave away information, and the ships were blown up.” They said, “Do not take or buy any soft drinks or any food from them.” They had sold Coca-Colas to some of the soldiers and had laced it with arsenic. They died a horrible death, a long drawn out death.

We left by train for Calcutta. It took us five days in this little train. We could raise the windows, but all the soot came in and you can imagine what we looked like. We had water. They had supplied us with water and we all had a canteen. One time a troop train passed us going in the opposite direction and we raised the windows and exchanged rations--we actually got some Spam. They were eating Spam, but we didn't have any. That was our first experience with Spam.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you ever feel threatened in India after you heard the stories about the arsenic-laced Coca Colas? Did you feel fairly safe in the hospital?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We were safe in the hospital. Our quarters were surrounded by a fence, but we were right next to a housing area and we had a long walk across a field to the hospital. I felt a little creepy, really. We could take a rickshaw and I did that often. We were living in the quarters that had been vacated by the British. They didn't tell us about the snakes. The wall came up to here just like the club, but then we had shutters that we could open or close. They stayed open most of the time. Every now and then, when I'd go out of my room for a shower or something, I would have to step over a snake, but I wouldn't pay too much attention to it. One day, one of the girls went into the bathroom and there was a snake coiled up. She screamed and one of the doctors came over and killed it. It was a cobra. So, they moved us out of those quarters, down on Tirinigi Road in Calcutta, not too far from the hospital, in what we call marble homes. One was yellow, one was blue, and, I think, one was pink. I didn't feel safe there at all. We were on the main thoroughfare and it was just teeming with people, walking and selling and begging. I didn't like living there. When we would go to bed, we'd put our mosquito nets in so tight because of the snakes that we could hardly get out in the morning. They got us out of that place in a hurry.

Then the patients came. Some came from Burma. We had troops in India and in China. They would fly the “Hump,” the Himalayan Mountains. They called it the "Hump." We had a lot of patients, but they seemed entirely different from those casualties we had from Guadalcanal.

Zara Anishanslin:

The wounds were different, or just the patients?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, it was all different. Not too many had malaria. Of course, they had everything in India. They had organisms there that we couldn't even read about. The day we arrived, we were taken on a tour of Calcutta by truck. I don't know why the General ordered that, but he did. One place they took us was to the burning ghat. There had been a smallpox epidemic and bodies were being cremated on the ghat, and that was the first place we were taken. That was sort of a shock.

Zara Anishanslin:

That was a nice welcome.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. Frankly, I don't remember what else we saw. They must have driven us around the city. We did go in one park that was very beautiful; it had a real dense wooded area. I learned that one sect disposed of their dead there by tying them to a limb of a tree. I guess the birds took care of them and their bones washed out to the river. That's the first time I'd ever heard of that.

Zara Anishanslin:

So India was much more of a culture shock than Fiji.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. There was an Indian wedding held across the street from our compound. It lasted five days and they played their music, which is sort of screechy. It really got on our nerves, but there wasn't anything we could do about it. A soldier accidentally killed a cow; ran into a cow and killed him. There was a great to-do over that. If it had been a Hindu person, they would have accepted it, because they believe in reincarnation. If a cow came into a building, they didn't make him get out.

Zara Anishanslin:

This is great. How did the people of Calcutta, the natives, treat you?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

They seldom smiled. They have beautiful features, but they seldom smiled. They didn't mistreat us, but we were sort of on edge. We didn't know how they were accepting us. We did go to a movie in downtown Calcutta. The first thing that was flashed on the screen was, “Secure your pocketbooks!”

Zara Anishanslin:

That will relax you for the movie.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It had captions. When we took a bus to downtown Calcutta, we passed a park and could see monkeys jumping from tree to tree. We'd think nothing of it. Our compound was next to the ammunition dock for Burma, but we didn't know that. Our compound was also right next to the jungle. The jackals would come up at night from the jungle. We thought they were dogs. They didn't bother us. They were looking for food.

Zara Anishanslin:

When you were finished in Calcutta, you returned home to the States?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, I did.

Zara Anishanslin:

You'd been away for quite a few years.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Thirty-five months. In the meantime, our country had formed the WAVES, WACS, and WRENS. We'd never seen any of them.

Zara Anishanslin:

So, you joined before all of that started.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, right after Pearl Harbor. When we returned from Calcutta, we left Dumdum Airport in a C-47. That particular plane has always had a good record, I understand. It was a two-engine plane with seats on both sides. There were quite a few of us who left at the same time and there were other personnel in the plane. I think there were some Air Force and Navy personnel on there. They even had the Navy in Calcutta.

We left Calcutta and we stopped in Karachi, which today is the capital of Pakistan, but it was in India then. We stayed there three or four days. We were actually in the desert. We could turn the water on in the shower and it was hot, it was heated by the desert. That wasn't a very interesting place to stop. Then we flew to Khartoum and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, which is where the White and the Blue Nile meet. I didn't know there was a Blue Nile, but there is, and that's where they both meet. I think the Nile is the longest river in the world. I'm not certain, but I think it is. Do you know?

Zara Anishanslin:

I think so. It sounds right.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Then we landed in Accra, on the Gold Coast of Africa. Today, the name has changed, but it was on the Gold Coast then and it was real pretty there. President Roosevelt died while we were in Accra and we were stuck there five days. I remember they had these huge lizards, iguanas. They reminded me of dinosaurs and they were big. I said, “You're going out there?” But we had to go outdoors. I didn't like those things.

Zara Anishanslin:

You had experience with all kinds of creatures; snakes and lizards . . . .

Sarah Wahab Moore:

One day we went down to the market. All the women were wearing the prettiest, brightest colors. The grass was so green, it went right down to the Atlantic Ocean. Everything was so colorful, it was a pretty sight. We stayed there five days. We had to stand at attention one day at noon and I fainted.

Zara Anishanslin:

From the heat?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Just standing has always bothered me, whether it is hot or cold or whatever. It was hot that day, however, and I just passed out. You'd think they would have had us stand attention at a different hour, wouldn't you?

Zara Anishanslin:

That doesn't seem real practical.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I think they found that out.

When we did depart, one of the engines caught on fire and so we came back into the airport. After the engine was repaired we went across the ocean and stopped at Belem, which is right on the equator in Brazil. We hadn't had anything to eat, so we went into the military dining hall and picked up a divided tin tray. We had scrambled eggs and they were green! We were used to powdered eggs, but we'd never had any green ones. We still don't know why they were green. I know we didn't eat them. I remember going in a little PX there and they had silk hose, not nylon, silk hose. They also had alligator bags and belts, but you know, it didn't appeal to any of us. We didn't want any of it.

Zara Anishanslin:

Were you just not used to it at that point?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, I don't know. It just didn't appeal to us. The alligator bags were quite something. I don't think they are very popular today, do you?

Zara Anishanslin:

No, I don't think so.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Then we flew on to Puerto Rico. Before they would let us leave the plane, they sprayed us for anything we were bringing in and I thought we were going to choke to death. They did that twice. We stayed there long enough to have a meal and then we flew on into Miami. It was so good to see lush grass and a clean looking place. Then we had to go through customs. They were rude to us. One of the girls was real proud of the orange she had brought from Africa. When they found out, they took that orange and threw it across the room. I thought they were quite rude to us. When we were in

Africa, we could buy a bottle of whiskey for something like sixty cents and the group had said, “Sarah, you should get one.” I said, “Well, what for?” I didn't want it. They said, “but you can get a bottle of Scotch for sixty cents.” So, I bought it to give to somebody who drank scotch when I got home. I had it in my bag and when the customs man came for my bag, I had a prayer book in there and it fell out and he said, “Oh, you look honest.” He closed my bag and I thought, Oh my land, that scotch is in there!

Zara Anishanslin:

Next to the prayer book.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I have no idea who I gave it to, but I gave it to somebody.

Zara Anishanslin:

So, was it nice to be back home?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It was nice to be back home. We had probably a thirty-day leave. My parents had saved a can of fruit cocktail for me. I didn't let them know it, but that was the only dessert we had in Fiji. They saved it for me.

After leave, I was sent to Ashford General Hospital in West Virginia. The rest of my friends went to Miami.

Zara Anishanslin:

You had been with the same people all through the war.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. They had a hospital in the western part of North Carolina, but they sent me to West Virginia. I had to go by train. I went to Richmond and then changed and went west. I wasn't there too long. VE Day was in June, and I was there for that. General Eisenhower came there to play golf. He came in his own railroad car. His wife was always with him. I stayed there until December when we were all discharged. I went back in the military, however. I just couldn't adjust. I was confused. I didn't know what I wanted to do.

Zara Anishanslin:

So you enjoyed the military then?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, after three years, it had become a habit. I had three years in nursing school and three years in the military. It was still a regimented life, but it was a good healthy life. I had spent thirty-five months in World War II. When I went back in, I was sent to Germany. That was the first interesting place. I was there two years. While I was there, I identified people by their feet. Our feet are narrow compared to German feet, because I guess they walked all the time, so I would look at feet as I walked along the street. There was one black nurse there and she was very unhappy because they stared at her. She was singled out and I felt sorry for her.

I was in Augsburg, which is an ancient city. There was an underground airplane factory there where they built the Messerschmitt plane. When we went to Germany, we were told that we were ambassadors. We didn't wear our uniforms. We wore civilian clothes. This was eight years after the war. We traveled in civilian clothes.

While in Germany, it was easy to drive down to Switzerland. We went down one day and I had forty American dollars that I had not converted to marks. I went into Fel Posh(?) Department store and bought two wool suits with that forty dollars. I wore those suits all over Europe. We learned to travel with a small bag because, of course, we had to carry our own luggage. We just took a change of clothes and got along fine.

Zara Anishanslin:

What kind of duties were you involved with in Germany? Were you based at a hospital there as well?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh, yes. I was in a field hospital, which is a little smaller than a general hospital. It was like any hospital; we had everything. We had dependents. We had children. We had psychiatric cases. We had surgical and medical cases.

Two German nurses worked in our section and they told me a lot of stories about the war. One of them invited me to her home during the Christmas season. The people in my unit said that I was the only American nurse that had been invited to a German home. Their home had been bombed during the war, so they lived in a small apartment. They had been quite well-to-do before the war. Her father, who had been a general, was killed. They had a pretty Christmas tree. They had real candles and they lighted all of them, which was really a fire hazard, but it was so pretty. Under the tree, they had a few gifts and a big photograph of Adolf Hitler.

Zara Anishanslin:

Really, and this was eight years after the war?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Eight years after the war. He was a friend of the family's. He did do a lot of good things with Germany, built all the autobahns, and all, but I felt so funny when I saw his picture. I felt so out of place.

Zara Anishanslin:

Were most Germans friendly towards you?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh yes. We could take a train ride to Garmisch or to Berchtesgarten for about eighty cents. Garmisch is a pretty little alpine village. They ski and it's just quaint looking and different. They have a lot of shops. They had a lot of Hummels. I think I sent everybody in the family a Hummel. I didn't even have one when it was all over. You know, they're really expensive now. A nun, I guess her name was Hummel, made the first ones.

Zara Anishanslin:

I didn't realize that.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

They really are sweet little figurines. I went down to the church where Martin Luther preached and something that he published was tacked to the door. I really don't know what it was. I think he started the ball rolling for the other Protestant religions. In the American and British sectors of Germany, the rubble had been cleaned up. But a friend wanted me to see the French sector, which is up the Ruhr towards France. That was the industrial section of Germany. We went through Darmstadt, one of the cities in that sector, and it looked like not one piece of rubble had been moved. I said, “I don't ever want to come up here again.” It really was no fun, but she wanted me to see it.

Zara Anishanslin:

Was France that way as well, when you went there? Had they cleaned up the rubble in their own country?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

They had cleared it and Paris was pretty. It was really pretty. I finally got up the nerve, when I was in Augsburg, to take the bus or street car to downtown. If there were two of us, we would wander around and go in all the churches. They were all ornate. We found the Fuggery. It's a housing project for the poor. It was constructed between 1519 and 1523 by this very wealthy Fugger family. I guess that was the first public housing development that we have any knowledge of. They were rather nice houses and fully occupied. I had never heard of it, of course. Anything in their country that was just two hundred years old, they would consider it new. It had to be pre-Rome to be old, I guess, because they had a road that was built from Rome to Augsburg.

We had a doctor who had a girlfriend and she was in the opera. So, one night we thought that we would go to the opera. We wanted to see this girlfriend. The

Germans were more cultured than we were. They didn't have the money to go to a movie, but they could afford an opera. I guess that's the music center of the world, anyway, Austria and Germany. We were so disappointed. She was a large woman in a georgette flowing costume and it looked like it would flow all over the stage. I shouldn't be laughing, but anyway, we got to see his girlfriend.

Zara Anishanslin:

But you weren't that impressed?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No, we weren't impressed at all. She had a good voice. A lot of heavy people do, I guess.

I went on a week's leave to Italy. It was a Hansel tour and we left from Munich. There were three couples who were tourists from the United States, this other nurse and I, and also a lot of the enlisted men from different units. We had a good group and we had a good tour. It was delightful. It would be nice to spend a week in Florence. It was more interesting than Rome.

Zara Anishanslin:

It's nicer too, I think.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I think so too. The most impressive thing to me in Florence was Moses. Michelangelo hit him on the knee and said, “Why don't you speak to me, I made you so perfectly.” That impressed me more than anything else in Florence, but maybe there was something wrong with me, I don't know. Of course, all of it was beautiful. Those baptistry doors--I guess they were bronze--were out of this world. I need to go back, but I'm not going. I was very disappointed in Naples. That was a dirty place. I wasn't even impressed with Vesuvius. Did you see Vesuvius?

Zara Anishanslin:

No, I didn't.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We went to Venice and that was the filthiest place. There was garbage floating. Did you go there?

Zara Anishanslin:

Yes.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

There was garbage, banana peels, and everything floating in the water and I thought, I can't believe this. I'd heard all about Venice. It was cloudy and foggy and then it rained, but the next day we were able to go out to the St. Mark's square, I think it was, where all the pigeons were. The shops were interesting, but I wasn't impressed with that place at all. I was impressed with Rome and I guess you were, too.

Zara Anishanslin:

It's grand. It's hard not to be.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We went in Saint Peter's with those four columns around the high altar. It's not a church. It's a Basilica. Well, I walked around one of those columns and it's as large as this St. James church down here. It seemed to me it was. I didn't know until we went that St. Peter's remains were under the altar. That was interesting.

Zara Anishanslin:

It sounds like you had a lot of time to explore much of Europe while you were in the military. That's nice.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, see, if you could have a week's leave every now and then, you could do this. So, that's why I bought those two suits.

Zara Anishanslin:

How long were you based in Germany?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Two years.

When we toured, I did most of my napping on the way. We were so tired every evening. When we went to Stratford-on-Avon, we went to see MacBeth with Laurence Olivier and Vivian Leigh. He had fractured a bone in his foot and he was hopping

around with a cast on. They were speaking Old English and I couldn't understand anything they said and I don't believe any of the other tourists in that building understood either. I would look down the line of seats and most of the men were asleep, so I wasn't the only one. They were really excited about Monty, however, and I thought, Who in the world is Monty? It was General Montgomery, their General; their World War II General in North Africa. He was wearing a tam as he wore in North Africa. They were more interested in him than they were in the play. I don't blame them for that.

I went to Fort Monroe from Germany. I was there three and a half years and then I went to school in Texas.

Zara Anishanslin:

Nursing school?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It was the Nurses Administration School in San Antonio. From there they sent me to Hawaii to Tripler. That was hard duty. You see, that was a hospital for the Pacific. We got the air evacs from Korea, Japan--because we had soldiers in Japan--and Guam. They all stopped there en route to San Francisco. We had so many patients. When I went there, we had Navy personnel and Army personnel at the hospital, but they pulled a lot of the Navy out, because they needed them. So, we worked together. I was there two years. I was married there at Fort Shafter.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you meet your husband there?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

I met him in this country. I was married there. We renewed the friendship by mail. He even sent the diamond through the mail in an ordinary letter. I thought the man was crazy. Don't you think?

Zara Anishanslin:

It's a little chancy.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

He put a little note on it that said, “Please hand stamp.” How about that?

Then I went to Fort Detrick[MD or VA?] from Hawaii and that was my last duty station. I was there three years. That was biological research.

Zara Anishanslin:

That must have been a change for you.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, it was a change. It was a very small place. We had a little out-patient place there. Where is it the President goes up in the mountains in Maryland? He and his family go up there for the weekend. Well, I can't think of it, but anyway, it was a weekend place where all the presidents go, and they had personnel up there and some dependents. Some of those personnel would be sent down to us instead of sending them on to Walter Reed. It was a real change, it really was. There was a lot of history there. Everybody who came to see us, wanted to go to Gettysburg. That battlefield is interesting, particularly to men or to history buffs. There's just a lot of history in Maryland and it's a beautiful state with beautiful country. Where are you from?

Zara Anishanslin:

St. Louis, but originally from Pennsylvania.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

My husband goes to pistol matches in Pennsylvania.

Zara Anishanslin:

Was he in the military as well?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes, at one time. I know we went through the place where Mother Seton's school is. I've forgotten the names of everything. Oh, Camp David is the place I was trying to think of. We used to get personnel from there in our little hospital. Biological research, however, was what the place was set up for, and it was very different from what I had done previously. It was secret work.

Zara Anishanslin:

Did you enjoy it?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Yes. I retired there.

Zara Anishanslin:

What did you do after you retired?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, for a while I didn't do anything. Then we moved down here to take care of my mother and her sister and we've been here ever since. I did that for ten years. I worked harder out of the military than I did in. I really did. Of course, I'm a widow now.

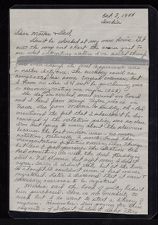

I don't feel that I've given you a real coherent thing. If I'd gone by this, it would have jarred my memory, I guess, but I didn't do that.

Zara Anishanslin:

I think you gave a lot of detail that adds nicely to what you've already written down.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

You think so? I don't know.

Zara Anishanslin:

Was there anything you felt as though we didn't cover that you wanted to?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

The commanding officer of our hospital back in Fiji was promoted and left the hospital. He had a house in Suva. He invited the chief nurse, some of us nurses, and some doctors--so many, he didn't care who--to his house one evening. We had to go, because we were told we were invited. I remember sitting by the orthopedist and being so bored, that we did a study of all the shoe laces he could find. A friend mine was roaming around the house and she came out and said, “There's a golden brown turkey in the kitchen.” I guess something was served, I don't remember what in the world it was, but he never did serve us any turkey.

When we left the party, it was raining and everybody was wearing a raincoat. We got into these vehicles that had open sides. I don't know what they're called, they had a military name. I said to my friend, “What in the world do you have under your raincoat?”

She said, “Shh!”

We got to our quarters. They had built a long barracks for us. There were two of us to a room and the wall didn't go all the way to the ceiling. We could crawl over the wall to the next room. Anyway, we were going down the three steps to our quarters when this turkey fell out.

I said, “Frances!” We picked it up, brushed it off, went in and pulled out hunks of meat and gave it to everybody. People were in bed and we carried it to them and said, “Eat it, eat it.” We couldn't go to certain rooms, because they would have reported us. Then we took the carcass out and buried it.

I said, “Do you know what they're going to do to us? They're going to send us to a leper colony.” There was one somewhere nearby, because the dermatologist had visited it and had come back and showed us all the pictures. I didn't take the turkey. My friend had a lot of courage, didn't she?

Zara Anishanslin:

That was definitely sneaky.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

So, he was missing his nice golden turkey.

Zara Anishanslin:

I bet you all were pretty sick of mutton by that point, though.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

In Fiji, we didn't have mutton. We had large canned wieners. They would be cooked in a blanket one day and boiled the next day. Dessert was fruit cocktail. That's

all I remember. We did receive eggs from New Zealand and butter, but the butter was full of kerosene. I guess the ship had been torpedoed.

Zara Anishanslin:

I don't blame her for stealing the turkey then.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

No one knew she had it, but the commanding officer was furious. He gave the chief nurse some soft shell crabs--I think they were already cooked--and she put them in the refrigerator down in our quarters. One of the girls came home, saw them in the refrigerator, and ate them. We were grown women, and you shouldn't take somebody else's food, but you know they sort of treated us like children.

I know I've left out things. I feel that I haven't had real good continuity.

Zara Anishanslin:

I think it's nice to have stories. It doesn't have to follow any particular order, necessarily.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

It was interesting to cross the equator, because it was an imaginary line. We had no air conditioning, however. I think there was one fan in a room. When we were aboard ship going from Suva to Bombay, there were twenty-four of us in a stateroom and I was always on the third tier because I was tall. As soon as daylight came and they'd let us go on deck, I went out on deck, for some air. It was very difficult. That was an experience. I think we were aboard ship twenty-one days one time and twenty-six days the other time.

Zara Anishanslin:

So you got to be quite a sailor in the Army.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Well, they didn't have enough planes to transport us. They didn't have what they have today. It's remarkable we won the war, it really is. We also had to treat

people without antibiotics. Penicillin was just being used in this country when we were ready to leave. It was killing people because they were allergic to it.

In Calcutta, I saw a neighbor who lived next door to us. He saw the pictures of us when we were leaving the train and recognized me. He came out to see me. He was a lawyer. He was intelligent, but we weren't supposed to fraternize with the enlisted men. He came in civilian clothes which was nice. We went over to the club and had a wonderful evening. That seems silly that we couldn't fraternize with enlisted men. My roommate's brother was enlisted. He came in on a destroyer and they gave her permission to go see him. She took me with her and all the officers left the area of the ship to us. You would have thought we had tuberculosis!

Zara Anishanslin:

That's strange, too, considering that it was very friendly on Fiji; that they would have a rule like that.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

But that was the Navy, that was another thing. They're different, very different. I remember the Navy hospital ship came into Suva. Some of the personnel went down and went aboard. I wasn't with them that time, but two of the doctors came back and said, “Those Navy nurses didn't even speak to us.” It rather amused me. We were so different; I don't know why they were so haughty.

Zara Anishanslin:

So you feel as though the Army was a bit more relaxed.

Sarah Wahab Moore:

We had a Marine who was a patient in Fiji and he was so well treated, that he said, “When I re-enlist, I'm going to join the Army!” So, I guess it paid off. See, normally the Marines went to Navy hospitals.

Zara Anishanslin:

So, you enjoyed your time in the Army then?

Sarah Wahab Moore:

Oh, yes. I really did. We moved every two to three and a half years and it's hard to settle down after you've been doing that. It really is.

[End of Interview]