| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

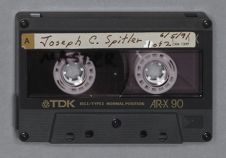

| Captain Joseph C. Spitler | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| June 5, 1991 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Captain Spitler, would you begin by giving us a little of your background? Where you are from originally, where you grew up, and what led you to the Naval Academy?

Joseph C. Spitler:

I was born in Lufkin, Texas, which is over in east Texas. I lived there until I was about four, when I moved to Jacksonville, Florida. I lived there for about six years, then back to Texas--to Houston originally, then back up to Lufkin.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your father doing to cause you to move back and forth like that?

Joseph C. Spitler:

He was in sales. Originally, he was with the Lufkin Foundry and Machine Company, which he had started with around 1905. When we went to Florida, he was with Manhattan Ray Bestus(?) Manufacturing. Then came the crash of 1929; everything folded up over in Florida and that's when we moved to Houston and, I think, he worked with the Houston Belting Co. Around 1932, we moved back to Lufkin and back with the Lufkin Foundry and Machine Company. I was in high school by that time.

When I was a junior, a fellow named Truette Cook and I were walking home from school one afternoon down Ragae Avenue. I was at a complete loss as to what I was going

to do, except that I knew that I wanted to go to college. I had no money and no idea which college. I asked Truette what he was going to do. He said, "Well, I'm going to Annapolis."

I said, "Bye-golly, that seems like a good idea!" I had seen all the movies where the girls are chasing after the midshipmen. That was my great naval orientation, if you will. I got home and told my mother, who was standing in the kitchen, that I was going to go to the Naval Academy. She said, "Oh, no, I'm not raising any soldiers or sailors." My dad had different ideas. So I went to work on it.

I was told by my high school principal, Mr. Grisson(?), that if I wanted to get into the Naval Academy, there was only one person to see, and that was a Mr. J. J. Collins. He was a prominent attorney in Lufkin, with rather strong political connections, specifically with Martin Dies, a congressman from the second district of Texas. He was on the famous Dies Committee during the thirties. Congressman Dies came to Lufkin and I met with him and Mr. Collins. He said, "Now, of course, I can't promise you anything, but if you will go to college for a year, we will take care of this."

I had taken the competitive exam when I was a junior and did so horribly, they didn't even want to tell me my grade. I did as Mr. Dies suggested. I went to college and at the end of the year, I got my grades off to the Naval Academy. Everything was fine and I qualified to get in without anymore exams. Low and behold, I got a letter from Congressman Dies' office that said be prepared to take the competitive exam. I went down to see Mr. Collins. He called his secretary in and said, "Take a telegram to Mr. Dies saying, `Dear Martin, It was our understanding that young Spitler was going to get an appointment to the Naval Academy.'" Before I got home, I had a telegram from Martin Dies, saying that I had the principal appointment to the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

You got in without taking the entrance exam!

Joseph C. Spitler:

Our class was the first to have to take the preliminary physical exam before we reported to the Naval Academy. I went to Houston to take my exam and I just barely squeaked by on the eye exam. The doctor said, "You're going to have a tough time passing the exam, but if you do pass it you will be in good shape for the rest of your career."

My mother and dad put me on the train in Beaumont in June, 1937. On the way up, I decided that I would get out on the rear platform and view the scenery. I caught a cinder in my eye, which didn't help the eye situation. I got to the Naval Academy and I flunked the exam throughout that week. Finally, I was taken to the head of the medical department by Dr. Ball(?), the doctor who had given me the exam. He asked me, "What kind of chart did you take the exam with?"

And I said, "One of those big ones that starts with a Z, then gets smaller. The other ones I had been taking had just a strip of light with letters on it."

So he told Dr. Ball(?) to take me in and give me the exam on that. I would say, "It's an N." Dr. Ball(?) would say, "If it's not an N, what is it?" I'd say, "M." He'd say, "That's right." I'd say, "O.""If it's not an O, what is it?""C." So I finally passed the exam after a week of trying.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's a completely different story of eye exams for other members of the class. Some of them had a really tough time.

Joseph C. Spitler:

My story, throughout my career, if you will, is a story of close shaves. That was the first one . . . a close shave getting in.

Donald R. Lennon:

What happened to your friend, Truette?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, he got in. He was in the Class of 1940, a year ahead of me. He resigned at the

end of his second class year. He went off to the University of Texas and became a lawyer. When the war came along, he joined the Army. His family didn't like that because they were big rooters for the two of us. Our families had known one another for many, many years. To say that they were disappointed is an understatement, because his oldest brother, Cecil Cook, a very prominent attorney in Houston, had helped him, or kind of arranged for him, to get that appointment. So it didn't set very well with him.

Anyhow, I got in. I was sworn in in the commandant's office with a couple of others who had also been late. Then we were turned over to a second classman, who took us down to the midshipmen's store with many laundry bags to be filled, then, with stenciling equipment in hand, back to our rooms to write laundry numbers on our belongings. It was the middle of the summer with no air conditioning, and I was breathing the fumes from the stencil ink and all of a sudden, I said, "My God what am I doing here?!" That transition was such a shock that to this day, I can't get my laundry number out of my mind--number 697.

I remember the first midshipmen cruise on the USS TEXAS, named for my home state. We went to France and England. We went into Portsmouth, England and then on up to London, when we were invited to a reception at the ambassador to the Court of King James. This reception was one of the highlights of the cruise. The ambassador happened to be Joseph Kennedy; so we met all of the Kennedy tribe. Although at the time I did not know exactly who they were or who they were going to become. Lady Astor was another well known person that was there.

Backing up to plebe summer . . . we were in the math class, learning to work the slide rule. I was a little careless and wound up as the anchor man of the class that first week in math; so the next week, I got up on the front row. The professor, an older gentleman,

kind of hobbled in with a runny nose and blurry eyes. He said, "Gentlemen, what is the most valuable thing in our lives?"

I took one look at him and thought, This guy has got to wish he had good health, so I said, "Health."

He said, "That's right. What's your name?" From then on, I did okay in math.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about the academics? What was your impression of the instruction that you received at the academy?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, it was good and it was valuable. Some might say that it wasn't really instruction, because we were given our assignments and we studied it, and if we didn't get it, then we had a real problem. It was tough. I spent Christmas leave, my youngster year, at the Academy. I made a very low grade on the first math exam. The rule was we had to make daily marks for the second bi-monthly period, so that we could make the same mark on the next exam to still be "sat." It took some rather high grades.

The professor didn't understand. I went to him just before the time was up and I said, "Am I going to make it?" He said, "I can't believe that you even have a problem." I said, "Yeah, I busted the exam." He said, "Well, you can go see Commander Dees, who is head of the third class math department and maybe he can help you."

I went in to see Commander Dees. I shall never forget. He said, "Oh, yes. Mr. Spitler." I said, "Is there anything I can do?"He said, "Yes, you can go over to your room in Bancroft Hall and kick yourself in the behind for not making better grades. I hope you enjoy your leave here at the academy."

It was tough, but it was good, I thought. It certainly tested one, and I, in a sense, sweated it out all the way through.

Donald R. Lennon:

A person had to be self motivated, did he not?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. As I look back on it, I think it was the stubborn Dutchman in me. The goal setting was obviously what got me into the Naval Academy. I wasn't one of those born and raised in the tradition of the naval service, who "every since I was a toddler knew I wanted to be a naval officer" sort of thing. So I got in there and I set a goal: To graduate from the Naval Academy. For whatever else I can attribute it to, setting those goals and being a stubborn Dutchman enabled me to hang in there until I did it. It was a great day!

When we were plebes in our English class, our English professor said, "Gentlemen, for those of you who make it the four years, when that final graduation day comes, if you don't have a tear in your eye and a lump in you throat as you leave the main gate, then there is something wrong with you."

When our graduation came Frank J. Knox, Secretary of the Navy, was the speaker. After the ceremony, we went to our rooms to get our bags and headed for the main gate. It was pouring down rain. As I was nearing the gate, they sounded attention to render honors to Secretary Knox as he was leaving. As I stood there in the rain, I reflected back on that English professor's statement, but I thought, "Yes, there is water running down my face but it is not tears." With the passage of years, however, I can say that those times and the years that followed were the greatest things in my life and the most meaningful.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've heard some naval officers talk about their experiences at the academy in which they were harassed by the upper classmen to a certain extent. Did you experience that or were you protected by your sponsor?

Joseph C. Spitler:

My first classman, if that is who you mean by sponsor, . . . was Daniel Ermentrout Henry, Class of 1938, was a great guy, but no, I wasn't protected. I think I suffered as much

as the rest. To me that was part of the deal.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any particular incidents that you recall?

Joseph C. Spitler:

The incident I recall was one in which the hazing was turned around the other way. It occurred on "Hundredth Night"--the hundredth night before graduation--when it was the plebes turn to haze the first classmen. We took out after the Class of 1938 like you wouldn't believe. It was an organized mayhem, maybe not even very well organized, just plain mayhem. The thing that struck me about it was the way the Class of '38 took it.

Donald R. Lennon:

I've never heard anyone talk about that before.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, it was one of those traditions.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did you do to them and how did they react?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, it was beating tail. Making them bend over and assume the angle and giving them a good paddling. It was our turn to get at them. They took it like real good sports.

On reflection, I remember when we had our chance to work on the new plebes. I recall trying to put one of the top tennis players in the nation, a guy named Joe Hunt, I think, in the shower. My classmates and I discovered what strong legs a tennis player has because we had a lot of trouble getting him in there. The hazing was part of the game. Maybe it didn't make sense, but that's alright; you learn to do things that don't necessarily make sense but you do them anyhow.

These were the highlights of my years at the academy. It was tough, but rewarding. The camaraderie, and the sense of belonging, the common goals, and the close relationships that we made that have lasted through the years are things that are hard to match in our society, especially in this day and age.

Donald R. Lennon:

After graduation, what was your assignment?

Joseph C. Spitler:

The USS OKLAHOMA at Pearl Harbor. I had a little leave in Lufkin and then proceeded on out to San Francisco, where I boarded a transport to Pearl. It was to be the first of many sailings under the Golden Gate Bridge. Of course, being one of the lower men in the class, I was down in the hold, which wasn't too pleasant when the ship started pitching and rolling. I reported to my ship assignment out in Pearl in March.

Donald R. Lennon:

A good portion of the class went directly to Pearl, did they not?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. I don't know how many were on that transport with me, but it was a large number. I reported to the OKLAHOMA and after operating in the islands for some months, we were ordered back to the States for leave, liberty, and recreation. We were supposed to go back to Long Beach, but on the way, the OKLAHOMA parted a propeller shaft and we were diverted to Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco. That visit turned out to be my larger introduction to that fine city. We were there about six weeks. It also gave all of us a chance to go home. This was November of '41.

While I was at home on leave I bought my dad a new set of golf clubs. It was a combination birthday Christmas gift. When I left, I took his old set back to the OKLAHOMA with me. When I went back to the OKLAHOMA, after it was sunk, the only thing in my stateroom was one of those golf clubs. My dad almost killed me when I told him that it was all rusty and everything so I just tossed it aside. He would have liked to have had that as a trophy of the war.

We left San Francisco and headed back out to Pearl. We got there in time for the "big show."

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there anything about the attack that personally impacted on you?

Joseph C. Spitler:

First, I would like to say that we were under orders to attack any unidentified

submarine, which suggests that somebody knew something. On Saturday, December 6, I went ashore. As we were heading in in the officers' motorboat, I was quite impressed that for the first time all the battleships were there. It was quite an impressive sight.

I came back to the ship on Saturday evening because I had duty on Sunday. As I recall, it seems to me there was a movie by Orson Welles, "Hold Back The Dawn." I've been trying to check for years to make sure I didn't make that up or that it was just an erroneous recollection. At any rate, I had the four to eight watch, the morning of December 7, along with Bill Ingram (Class of '38)--the famous football player. We were relieved at a quarter of eight. I went to do what one would normally do after being on his feet and drinking all of that coffee. I went by my stateroom, took my white jacket off and hung it up and put my wallet on the desk. Then I went up to the head and that's where I was when I got the word that the Japs were bombing Ford Island.

The word was passed by the officer of the deck, who was Herb Rommel(?), my division officer. I was in the fourth division, number four turret. He did it in a rather colorful manner. In these kinds of publications I wouldn't want to use the words he used, but he left no doubt in our minds that it was not a drill.

My normal station was in the handling room, so I started running aft after hearing about the attack. As I went through the junior officers quarters, they were calling "General Quarters. Man your battlestations." Being Sunday morning, there were a lot of junior officers up there still asleep. By the time I ran about half or maybe a third the length of the ship, the torpedoes started hitting the OKLAHOMA. They were hitting in the forward part because that was the only part of the ship that was exposed to the channel the torpedoes had to be launched in. I'm sure that caused a lot of the casualties in the junior officers' quarters.

If I hadn't had that four to eight watch, that's probably where I would have been that morning.

Donald R. Lennon:

Quite a jolt when they hit, wasn't it?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, you could feel the ship, jump up a bit. There wasn't any question but what something was going on.

Donald R. Lennon:

I gather the alarm was sounded verbally rather than an actual alarm.

Joseph C. Spitler:

No, it was over the public address system by the officer of the deck himself. Normally, the bosun's (boatswain) mate has the job to pass the word, but in this case, the officer of the deck himself jumped on the public address system. As we ran through the ship, the idea was to pass the word in addition, in case they had missed it.

When I got to the lower handling room, I was told that there was no turret officer because he was the officer of the deck. I went up to the turret officer's booth, but by the time I got up there the word was passed, "Abandon Ship." The ship was already starting to list. We got out through the overhang of the turret.

By the time we got out on the overhang, the water level was already up to the middle of the deck. The ship was in about a 30 degree angle or so. I recall taking my nice white shoes off so I wouldn't mess them up, putting them on the deck, and then watching them slide into the oily water. By that time, the ship was almost on beam-ends and still rolling. I told all of those around me, "Let's abandon ship and swim clear." So we started swimming. By that time there was quite a coating of oil on the water. I looked over my shoulder and there was a huge brow tittering right over our heads. It must have weighed a couple of tons. It connected the OKLAHOMA to the battleship that was inboard. I thought, Well if that doesn't get us, the ship will, because by then the ship was rolling over

towards us. Fortunately, I cleared it by maybe ten or fifteen feet. Then I looked up and saw high level bombers coming right down Battleship Row. I thought, If those bombs fall in the water, the concussion is going to really tear us up. So I began swimming like mad toward a launch near by. No bombs dropped and I got to the launch. I learned later from reports that the Japanese gave us that they had lost their point of aim. That was another close call in my career that I got by.

We finally reached the receiving station, then the Japs started strafing us there. Finally, everything kind of settled down, and I was able to go back out to the OKLAHOMA. Of course, it had rolled over and we could get up on the bottom. The chief engineer was there along with some of the other officers. We could hear people tapping in the hull. We started getting some shipyard workers out there to try to help get the trapped people out of the ship, but they couldn't use cutting torches because of the danger of setting off the oil in the tanks they were working around. Instead, they had to use pneumatic cutting tools. Finally, we got back into one of the last compartments, back in the shaft alley. We could still hear people tapping back there. We had a big Hawaiian who was working on it. There was an article in Reader's Digest about him not so long ago. How he should have gotten a medal and finally did. He certainly deserved it for the work he did rescuing those people that would have been trapped there.

We got down to that bulkhead and he started cutting around--cutting a square hole--but he had to be very careful that he didn't puncture the skin at any point, because the water inside would come up and drown the men before we could get that opening out. He went all around until he decided that he could knock it out with a sledge hammer. It must have weighed three hundred pounds. He hauled off and hit that plate and out it went. Five guys

came popping out of the shaft alley where they had been trapped. That was Wednesday afternoon. They were surprised to find that it was Wednesday not Sunday afternoon. They had lost all track of time due to the horror of what they had been through.

Donald R. Lennon:

How many men did you rescue in all?

Joseph C. Spitler:

I think there were about thirty.

Then I was assigned to the emergency pool. As the ships came in and needed men to fill up their compliment, we would be sent with them. We did that until we ran out of men. I was hoping someone would rescue me and send me back to a new battleship under construction. Instead, I wound up going aboard the destroyer WORDEN. We were in DesRon 1. A classmate of mine, Lonnie Klingaman, enticed me to join him aboard the ship and we had a pretty tough skipper. For many years thereafter, he always apologized to me for getting me into that situation, but laughingly so.

Donald R. Lennon:

Competent tough or just tough?

Joseph C. Spitler:

He was competent, but I think it fair to say that he went a little beyond that. He was not much for the reserve officers; he made it particularly tough for them. I recall an ensign who got his orders to flight school before we left Pearl Harbor; however, the skipper didn't let him have them until we had cleared the Harbor. He made him go all the way down to Noumea with us. So there was not much love lost there. Little things like that did not make him one of the more popular skippers.

We went down and operated in the South Pacific. Eventually, we participated in the Coral Sea operations. Then we were ordered back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Anything on the operation here. That would have been early in '42.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. We were with the tankers so we really didn't get to see the kind of action that

was involved with the carriers. However, we rejoined the carrier task forces and were ordered back to Pearl at maximum speed, without zigzagging. They had broken the Japanese code and knew the Japanese were going to hit Midway. We weren't told what was going on, but we knew it was something strange because we always zigzagged when we were out operating that way. But this time, we made a straight run at maximum speed, got into Pearl, replenished with ammo and supplies, and headed for Midway. I was in the detached group with the HORNET.

It was at this time that I experienced another close shave. The Japanese had sent a scout plane out; they had found two of the carrier groups and were looking for the third. From the stories I've heard, the Japanese scouting plane's transmitter went out. He could hear his task force commander asking if he had spotted the carrier, and he had, but he couldn't report back. We escaped that action.

Let's backtrack a minute to the attack at Pearl Harbor. You've probably heard this story. It was in some Japanese reports after the war. Apparently, the Japanese had sent a scouting plane to determine whether or not the carriers were in Pearl. His orders were if the carriers were in to fire one Very pistol, if they were not, fire two Very pistols. If the carriers were not in, they would hit the battleships first. Well, he fired the two Very pistols, but one of them went into a cloud, and the attacking squadron only saw one Very pistol; so they hit Ford Island where the carriers were normally berthed. That did give the battleships some warning. It gave me time to "get up off of my seat" and head for my battlestation and get out of that area where the torpedoes hit. Otherwise, the first I would have known about the attack would have been when the torpedoes started hitting.

During the battle of Midway the WORDEN had a little incident that was interesting.

Once the Japanese were pretty well knocked out of action and their ships were retreating, we chased them to get as many as we could. Suddenly, someone realized that the WORDEN was running out of fuel, so they sent us back to rendezvous with the tanker. We got alongside the tanker, but as we did, we lost all suction because we were out of fuel. The ship was completely dead in the water and we were starting to drift back on the big hawser. In those days, the tanker sent a hawser over to the ship that was being fueled. So we had to cut the hawser and it was a brand new hawser. I'll never forget the skipper of the tanker saying, "You're crazy. Quit cutting my brand new hawser."

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, what choice did you have?

Joseph C. Spitler:

We didn't have any choice really. I have to give credit to the engineering gang. I don't know how they got us going again. We got up enough steam to get alongside the tanker again.

After that, the WORDEN was sent up to the Aleutians. We were to put a scouting party ashore. The Alaskan Scouts were going into Amchitca in the Aleutian Islands. They were the advance party before the main amphibious body came in. The first day we went, the skipper decided it was entirely too rough to land. We waited until the next day. We went in at night and off-loaded these Alaskan Scouts in their rubber boats to reconnoiter the island. The charts were very poor and as we were heading out, we hit a reef and the ship became impaled on it. The seas were very heavy and they began to break the ship in two. We had to abandon ship. This was in the Aleutians, in January of 1943. Needless to say, it was a bit cool.

Donald R. Lennon:

The survival time in the water at that time of year would just be a couple of minutes, would it not?

Joseph C. Spitler:

That's what they say. I was a first lieutenant by then. We were up in the fo'c's'le and were the last ones off. We got into this balsa raft. We had our winter clothing on, our foul-weather clothing. From the waist up we were out of the water, but from the waist down we were strictly frozen, we were stiff. Our legs were absolutely stiff. If we had been immersed in that water, our whole bodies would have been stiff.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there enough raft space for everyone?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, there was enough space. There were, however, about fourteen men killed due to panicking. They dashed up and down on the deck and were afraid to get in the water. The waves hit the ship and knocked these men against the bulkheads. I think that's where most of them were lost.

Fortunately, the amphibious force had just come in and after they off-loaded their troops, they sent their landing craft over to pick us up. We had gotten off on the landside in case no one had come and we had had to go ashore. As we got close to the beach, however, we found that there were jagged rocks with waves breaking over them. That didn't look like a good idea; so we started backing down, paddling with a piece of broken metal. There were five of us, and we ended up in this little cove, trapped in there. One of the rescue ships was the DEWEY and a classmate of mine, Johnny Kirk, was on her. He was famous for rescuing people. He had done a lot of rescuing in the Coral Sea. He came around to the bow of our raft and said, "I'm going to throw this line to you crazies once, and if you don't get it, I'm not coming back!"

It came right across the raft. I grabbed it, but my hands were frozen and full of oil. I finally got the line around my elbow and it started to jerk me off the raft. I thought, If I'm saved and they're left behind, these boys are going to find some way to kill me. But my feet

were frozen and they hooked in the latticework down in the bottom of the raft and away we went.

We got out in open water and they started hoisting the guys up out of the raft into the boat. When it came my turn as senior officer, lieutenant junior grade, or whatever I was, they got me half way up into the boat and then the raft proceeded to drift away. They lost their grip on me and down I went into the water. Finally, I got hauled up on the deck of the DEWEY. They thought I was fine, but when they turned me loose, I couldn't move my legs because they were frozen, I fell over on my face.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did any of the men suffer damage from the freezing elements?

Joseph C. Spitler:

No. The men were either in rafts or they hung onto the ship until the landing crafts got to them.

Donald R. Lennon:

But, I mean even in your situation. Being on board the raft, did you not suffer from frost bite or damaged extremities?

Joseph C. Spitler:

No, but there was one rather funny thing that happened. One sailor pulled another one aboard a raft and discovered he was asleep. I learned in my Boy Scout days that when you are freezing to death you go to sleep. So I was massaging him and hitting him and trying to get him awake. Finally, the sailor says, "Mr. Spitler, there is nothing wrong with him. He broke his leg yesterday, and just before we hit the reef, the doctor gave him a shot of morphine."

Donald R. Lennon:

Well now, were balsa rafts standard on those destroyers?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

As a life raft?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. We had balsa rafts on the OKLAHOMA. They were firmly lashed to the

turrets and the barbettes. After the war, that was changed to quick release gear. If the water came up, the floatation would release them.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was anyone held accountable for the accident?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Good question. The skipper was pretty smart. Before we went on the operation, he said, "I don't consider the charts adequate enough to go in there at night, discharge these Alaskan Scouts, and get out without undue risk." That saved him probably from some dire consequences.

Donald R. Lennon:

So they accepted that?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. I was then sent back to the States to new construction. I went to some gunnery and radar schools, and then went to the HALL, putting her in commission up in Boston Naval Shipyard. We escorted one of the battleships with President Roosevelt aboard. It may have been the MISSOURI. He was on his way, I think, to Iran. We escorted him in the middle leg of his Atlantic voyage. It was another "high speed direct." We had three sets of destroyers escorting him. We broke off and headed down to North Africa and went in for a little liberty and recreation. We had Humphrey Bogart aboard.

Donald R. Lennon:

When was this time-wise?

Joseph C. Spitler:

That would have been in the summer or fall of 1943.

After that experience, we headed to the Pacific, participating in operations in the Marshalls, the Marianas, and the Philippines. One interesting episode occurred while we were in Manus, in the Admiralty Islands. We got sealed orders that said: "Do Not Open These Orders Until You Are At Sea." They were very, very highly classified. When we got out to sea, the captain opened up the orders. They were from Admiral Halsey, who was commander of the Third Fleet. We were told to proceed at best speed to Truk, an island

still being held by the Japanese. Halsey had evidence that hospital ships were moving Japanese troops in and out of Truk. Our orders were to go up and board one of those hospital ships. We are talking about one destroyer, all by itself, going up there.

The captain called me up and said, "Well Joe, guess who's going to be the boarding officer?" I said, "Don't tell me." He said, "Yep. Go down and study your `rules of war' manual," or whatever it was called. I was to find out what a boarding officer was supposed to do. Needless to say, I didn't get much sleep that night. But with the dawn, low and behold, came an operational immediate top-secret from CinCPac Fleet headquarters in Pearl. "Reference your orders from Commander Third Fleet, regarding boarding hospital ships in Truk. Cancel. Repeat. Cancel. Return to Manus." It was signed, Chester W. Nimitz. So I was saved by a fellow Texan.

Donald R. Lennon:

Any idea why they cancelled it?

Joseph C. Spitler:

I think Admiral Nimitz figured it was dumb. I don't know how many other judgements I had that paralleled his, but as far as I was concerned it was dumb. I'm sure if there had been any Japanese casualties, they would have been dying from laughing.

Donald R. Lennon:

One single destroyer sailing in there.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Maybe I'm all wrong there, but I think Admiral Nimitz figured it was something we could do without.

Donald R. Lennon:

What were you supposed to do if you discovered they were using these ships for troop carriers?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, that's a good question.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you to start attacking hospital ships?

Joseph C. Spitler:

No. I would have told them to "cease and desist," to off-load any troops they were

carrying to the island. You see, they were transporting troops in and out. I guess the idea was if there were any further operations of this sort, further action would be taken. I don't know. I was so relieved to get off that I did not question the reasons.

We went from there down to Hollandia and escorted some amphibious- type ships to the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. We got there after the battle of Leyte Gulf, but they were still having operations in and around the islands. They were sending destroyers around Ormoc Bay, down around the peninsula in Leyte, to fire shore bombardment. It was just like a suicide mission. Every destroyer that went down there was either sunk or very, very badly damaged. We were in line to be next when they decided the operation was too costly. They cancelled our orders.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was hitting them?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Shore bombardments and kamikazes. In fact, I was with a friend last night who was in the Class of '42, Rufus "Ruff" Porter, who was on one of the ships down there that was sunk. We'd see those that did survive, that didn't sink and they'd look like junk heaps, they were so badly damaged.

Donald R. Lennon:

There were no carriers close by that could soften up the shore batteries?

Joseph C. Spitler:

No, Halsey had all the carriers up north because there were reports of Japanese carriers coming down and of battleships coming through the Surigao Strait. History has indicated . . . and there are some opinions . . . that that was a mistake on his part. But be that as it may, it was decided that the operation was too costly.

We went to Mindoro and got in a night engagement up there. We discovered we had a rather important personage, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., as a skipper on one of the ships. We could hear him asking if he should be the one to stand-by, and so on.

My World War II action came to an end at Iwo Jima. We went up to provide close fire-support for the initial landing forces. We were up there throughout that. In fact, I saw the raising of that flag on Mount Suribachi.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you actually saw it.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. We were sailing around the end of the island and saw the flag go up. We didn't realize how important an event in history it was going to be. Then it came down--the first one came down--and then we saw it go back up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Symbolically.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. Our mission at Iwo Jima was to cover the UDTs, the underwater demolition teams, that went in before the main body. We were right up there, the first "guests," and the welcoming fire from the Japanese would greet us. From Iwo Jima we were to go to Okinawa to do the same thing. I thought, Hey, I think maybe this is enough of this. Before going to Okinawa; however, we went back to Ulithi, and received new orders. I had gone over to the tender on business when I saw this guy, who obviously was fresh from the States. I could tell because of his uniform. I said, "You don't happen to be so and so?" (I forget the name of my relief) He said, "Yes." I said, "I can take care of this business later. Let's go."

I flew back to the States and that was my last participation in the action in the Pacific in World War II.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you flown back for new construction?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. I went to Norfolk to train the crew for the ORLECK, a new destroyer being built in Orange, Texas. I had a great time in Norfolk. That's where I met my future wife. She was an ensign in the WAVES.

When we had VE Day, everyone started talking about the number of points they had. When VJ Day happened, the backbone of my crew had enough points to get out. They were hammering and clammering to "get out of this outfit."

I went to the commandant of the district and he said, "You take that crew and put them on that train to Orange, Texas. Whenever that train stops, you put your shore patrol at every door. Make sure that nobody forgets to get back aboard that train." It was a tough time, I couldn't blame them. They were not career people and they wanted to get out.

We went down to Orange and got the ship off to Guantanamo and went through our training. Then I got new orders. By this time, I, too, am thinking, Enough of this is enough. As they said in Mr. Roberts, " . . . after steaming from boredom to tedium and back again," you start to think, There's got to be a better way to enjoy life. I was getting tempted to find another career.

Then I got orders to command a destroyer escort that was being put out of commission in Long Beach. I thought, Well, this isn't too bad. I bought a car and started tooling around and having a little fun. Then I got orders to proceed immediately to Seattle to take command of the FIEBERLING, another destroyer escort. I reported to the commandant of the district there. He said, "Don't put your bags down; I've got a car waiting for you. It'll take you down to the pier." At the pier there was a boat waiting. It took me out to the ship and I reported aboard.

The executive officer said, "The ship's ready in all respects. We're getting underway." The skipper had gotten his points and the ship was scheduled to go down to San Diego for refresher training.

Donald R. Lennon:

Most of those wartime DE skippers were reserve officers.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. When they had their points, it was "bye-bye birdie."

I went up to the bridge and I said, "I can have a cup of coffee, can't I?" He said, "Yes, I'll bring you a cup of coffee to the bridge."

We went and did our training. It was a good ship. It had just come out of the overhaul and it had career people aboard.

We were ordered to Shanghai, China, where it became the flagship of the Amphibious Forces Seventh Fleet. I had a captain by the name of Ridout, a commodore who was the head of that unit. We anchored in the Whanpoo River, which was very treacherous, with very strong currents. I found Shanghai to be a very interesting city.

My next assignment was also interesting. I was assigned to do survey work for the Bureau of Ships for the SOFAR Project, (Sound Fixing And Ranging). We operated out of such exotic places as Monterey Bay, California, Kaneobe Bay in Hawaii, and Hilo, Hawaii. I was practically my own operational boss because we were really under the Bureau of Ships. I had assignments from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in San Diego and I worked with a Dr. Holsmark(?).

I was on that assignment, operating off the California coast. A big storm came up, causing a Chinese freighter to sink. We went out and rescued the crew and took them to Los Angeles; so I was a big hero. That was around Christmas-time. We got them off-loaded and then headed down to San Diego for our Christmas leave.

Later, we were sent to rescue two destroyers. They were being towed up to San Francisco to the Reserve fleet, when they ran into a storm and broke loose from the tug that was towing them. We were to take the destroyer in tow to keep it from going up on the beach. There were about five men on the destroyer. It was in the wee hours of the morning

when we got alongside with our tow line. The tow line was practically like a G-string. It didn't have any catner(?) in it--any spring--to keep it from snapping, but we held it in place. We couldn't go ahead until a tug came along and picked it up to take it to San Francisco. As a result of a few of those things, I was invited by Admiral Francis S. "Froggy" Low, who was then Commander Destroyers Pacific, to be his aide and flag secretary at Pearl Harbor. I had just gotten married and that seemed like a pretty good place to be.

Donald R. Lennon:

That was the first shore assignment you had had since 1941, wasn't it? You had been at sea the whole time.

Joseph C. Spitler:

That's right. Except for a couple of weeks at radar school and a couple of weeks at gunnery school.

Donald R. Lennon:

As far as duty assignments, that was your first.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Exactly. That assignment was very nice.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were due for some time.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, and we got a set of quarters with it. I was a lieutenant commander.

Donald R. Lennon:

Up until that point, you had served aboard battleships, destroyers, and DE's. Which did you prefer?

Joseph C. Spitler:

The destroyers. I went through the rest of my career in destroyer quarters.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were the DE's a little small for you?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, and that FIEBERLING couldn't have been a more uncomfortable ride. It was a very stable ship but it had a very quick snap to it. When it rolled over, you had to be braced when that baby came back! A destroyer is a little more reasonable. It's rough, but they're larger, and they do more things.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sheldon Kinney, from your class, thinks that the DE's were the greatest ship.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, it was a good ship. It was a turbo electric. You could really maneuver it--all backfull to all aheadfull--a lot easier than the regular steam turbine types. I enjoyed them both, but I'd say the destroyers are more comfortable.

I spent two years in Hawaii as aide and flag secretary under Admiral Low.

Donald R. Lennon:

Things were fairly quiet out there at that time, were they not?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, it was nice. One of the big things they were trying to do was shut down all the war materiel out in the Pacific--get rid of it one way or another. The pace was a lot slower and very enjoyable. I remember Saturday evenings at the submarine base officers club: the white tuxedos, Hawaiian bands, and the atmosphere of the islands. It was very nice.

Then I received orders to the executive department of the Naval Academy and I was there a year. I was selected to be the exchange officer to the Military Academy at West Point. They had just started a program where West Point would send an officer to the Naval Academy and the Naval Academy would send one to West Point. That was nice because they wanted to make certain when I went back to make my report to the Naval Academy, I had nothing but glowing reports about the Military Academy. They were a bunch of fine people. It just seemed a little strange for a Naval officer be standing watch out at their training grounds in the mountains, with the moon shining down through the trees.

I went on the duty status with the Corps of Cadets to Philadelphia to attend the Army/Navy game. It was the year in which it was impossible for Navy statistically to win the game. That, of course, doesn't mean anything in Army/Navy games. Sure enough, we beat the Black Knights on the Hudson, fourteen to two. I still have the little card from Cadet Vandenberg, of the famous Vandenberg family (General Vandenberg and Senator Vandenberg). It says, "Congratulations! Navy 14, Army 2," and has a little picture of the

football going between the goal posts and a cadet over in the corner crying.

I arrived at West Point on the twenty-fifth of June 1950, which is the day the North Koreans moved into South Korea. Matters got quite serious at West Point, because all those young fellows were soon to be faced with combat duty in Korea.

From there I got command of the HYMAN, a destroyer, in the destroyer division 122. We headed for Korea, via the Panama, San Diego, out through Midway to Japan, and on up to Korea.

Donald R. Lennon:

Is this during 1950 or 1951?

Joseph C. Spitler:

This is the summer of 1951. I had just spent one year at West Point. We arrived in Korea fall of 1951. Our most interesting operation there was operating in Wonsan Harbor, which was held by the North Koreans for a period of about six weeks. It wasn't too bad, we knew how to operate and maneuver the ship to where we could do our fire missions and stay out of range of their shore batteries.

Donald R. Lennon:

What about planes?

Joseph C. Spitler:

We didn't have any problem with planes because our carrier was operating in there and our planes kept them busy. I call it our air superiority. We got an order from one admiral that said, "Under no circumstances will you proceed up in the inner channel." This was called "Ulcer Gulch", because if you ever got up in there you came directly under their shore batteries. Then I received an order from another admiral, to knock out a railroad tunnel. The only way I could reach the railroad tunnel, was to go up "Ulcer Gulch." The danger was there was no room to maneuver at the end of the channel. You had to just twist the ship in its own water. Each time we went up I'd say, "All unnecessary personnel below decks, topside people man your guns."

Donald R. Lennon:

So you did proceed up the channel?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. I had a commodore aboard, the division commander, Captain Groverman, and he said, "Well, Joe, you've got an interesting decision. If you go up there and you get damaged and somebody gets killed, they will court-martial you for disobeying one admiral's order. If you don't go up there, you won't carry out your mission; so, we will have to take some action for you not carrying out your mission. It's your decision."

I said, "Thanks, commodore."

When we went up there the first time, we had all personnel below deck, wearing life jackets and helmets, with the guns manned. Nothing happened! We twisted the ship at the end and came out. We went up six times and fired at the tunnel, knocked the railroad out to prevent the train from running. Then we started up for the seventh time. My executive officer was quite rotund, especially with his Mae West life jacket on, and he was squeezed in between the compass and my chair on the bridge. We were talking business when "shhhheeeewwww, swish!" We were straddled up on the bow of the ship by shore battery fire. I don't know how the exec got out from behind that compass, but he was gone, and we started firing back. We started twisting the ship in its own water. Starboard engine ahead flank, port engine back emergency full, left full rudder. The engine gang gave it all they had. A funny thing, as we twisted around, the gun barrels on the forward mounts were now down alongside the bridge. Everytime they fired, the officer of the deck's helmet flew up about a foot above his head, practically choking him to death with the strap. We got hundreds of shrapnel bursts in the super structure; we got one direct hit; and not a man was scratched. The commodore said, "Well, I guess I promised you a medal."

We didn't silence them but we disrupted their firing.

An interesting thing happened just before we went up. I called the commodore and said, "Well, commodore, we are going up to `Ulcer Gulch' again."

He said, "Okay, fine. I was just about to take a shower." We had done this six times and nothing had happened. The seventh time was the charm. It took the side of the shower off and there he was standing in the altogetherness. It didn't hurt him. He dashed into the combat information center in something less than a full uniform.

I had just received my uniform. When we graduated from the Naval Academy, they cancelled our orders to get full-dress uniforms because World War II was coming on. A tailor by the name of Lowe(?), on Maryland Ave., was making mine up. He said, "Well, I guess you want to cancel yours." I said, "No, just put it up. I'll be back some day and get it." It had been cut but it hadn't been sewn together. So, when I went back to the Naval Academy for duty, he measured me again so he could fit it. Just before this happened, in Korea, that full dress came aboard. I said, "I'll bet anything when I get down there, I will find that full dress blown full of holes." It wasn't, it survived, and the commodore survived; we all survived.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was that the direct hit that took the side of the shower off?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, and it's interesting that it only damaged the shower and didn't hurt him.

Our division, after our turn was up in Korea, was ordered back to the States. We went back via "around the world." We went from Korea to Hong Kong, down to Singapore, to the Indian Ocean, and stopped in Ceylon, which is now Sri Lanka. Then we went up into the Persian Gulf. The flagship went to Ras Tanura (Ra's at Tannurah), which is right near Bahrain. We met with some of the dignitaries like Emir Turki, one of the sheiks, and we visited with the ARAMCO people--Arabian American Oil Company. Then we went

around to the Red Sea, Suez Canal, Mediterranean Sea, Gibraltar, and then back to Newport. We took the ship around the world, which was an interesting experience.

From there I was ordered to the Armed Forces Staff College as a student and then on the faculty. Then I continued on to CincWesLant staff, which was a part of CincLant Fleet, but was the NATO part. I was a war plans officer for CincWesLant.

My next assignment was a good break for me, but kind of a tough break for the skipper of the DUPONT. He broke his leg while they were down in "Gitmo," (Guantanamo) on shakedown. So, I was ordered down to take command of the USS DUPONT DD-941, which was one of the newest destroyers. I took her to the Mediterranean. While we were over there the secretary of defense came aboard, he was touring the Mediterranean. I had an interesting visit with him.

Donald R. Lennon:

Now was there anything going on in the Mediterranean at that time? I know during the 1950's things heated up on a fairly regular basis there.

Joseph C. Spitler:

No, not really. When I had the HYMAN over there, we were sent down to Tunis to celebrate the tenth anniversary of its liberation. Marshal [Alphonse Pierre] Juin, British General [Harold R.L.G., Earl Alexander of Tunis] Alexander, and United States' General [Alfred Maximilian) Gruenther, who was on Eisenhower's staff, came down. That was an interesting experience. When we went over there with the DUPONT, nothing special really happened. Admiral ("Cat") Brown was the admiral of the Sixth Fleet; he kept things interesting.

Donald R. Lennon:

I understand that he was an interesting individual.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. It was a very interesting tour. The DUPONT was very maneuverable. You could maneuver it almost like those DEs where you didn't have to worry about the super

heaters. The other destroyers wanted you to do a Mediterranean approach to the tankers, none of this business of the slow approach. You came up at 25 knots and then said, "All back full." That was "Cat" Brown's idea of a smart way to go alongside a tanker. The older destroyers, however, had those super heaters, which caused problems. The engineers had to get the super heaters off to do the backing. With the DUPONT you didn't have to worry about that. It was very maneuverable and a lot of fun, a beautiful ship. The most interesting operation with the DUPONT was when I was part of the Operation Inland Seas, the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway. A cruiser and several destroyers were sent for the official opening of the locks, opening the Saint Lawrence all the way down to Chicago from the Atlantic Ocean. President Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II were aboard the royal yacht BRITANNIA. It was almost like a cruise liner, about 400 feet, a beautiful ship. The DUPONT was assigned, along with a Canadian ship, to be the official escort of the BRITANNIA during the opening of the locks. The trip was very exciting and the countryside was beautiful. We wound up in Chicago, where I had a big thrill, if you will, for as long as it lasted. I got a message saying that I was ordered to the BRITANNIA for an audience with her majesty, Queen Elizabeth II. So, I put on sword and full dress and proceeded over there. I got up on the quarter-deck of the BRITANNIA and the admiral met me. He said, "We are very sorry, but her majesty had an impacted wisdom tooth this morning and had to go over to have that fixed." So, I visited with him and got an autographed picture of her majesty and Prince Philip, which I understand is worth a bit now. I guess my closest claim to fame, in that regard, was when I went to a Rotary luncheon later and met the dentist that worked on her, so all was not lost.

That was a great tour. It ended in a little port at Oswego, New York. The water was

so shallow that they said, "Do Not Use Your Propellers!"

Donald R. Lennon:

I was getting ready to say, I didn't think Oswego was big enough for a destroyer.

Joseph C. Spitler:

It wasn't really, so they had a tug meet us and pull us in there. If we had turned the propellers over, we could have done some damage.

I went to the Naval War College for a year and then to the staff of Joint Chiefs in Washington. While we were there, General [Nathan Farragut] Twining was the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. He insisted all officers leave the Pentagon exactly at 4:00, no night work was to be done. I thought this was fine, but I didn't know what to do with myself. I was used to working all day and all night. I decided to get my masters degree in international relations from America University. That was during the Kennedy years.

There was one project I worked on that made an exception to that 4:00 rule. Our boss, who was an Air Force general, came in one day and said to those of us in our section, which at that time were an Army Colonel, an Air Force Colonel and myself, "Go get something to eat."

Donald R. Lennon:

What was your rank at the time?

Joseph C. Spitler:

I was captain then. I made captain in 1960 while I was at the War College. He told us to get something to eat and meet him back there because we had a project to work on for [Robert S.] McNamara. When we came back John Connally, [Jr.], was sitting at my desk. He was secretary of the Navy then, so he was our project officer. This was on a Thursday and McNamara wanted it to be Monday. There were forty-nine questions, and we were grappling with contingencies that might occur anywhere in the world. That was a big order.

We were apparently not heading in the right direction, according to the preliminary reports that Connally was giving to Secretary McNamara. Therefore, we were called up

Saturday morning in McNamara's office. All the service chiefs, the service secretaries, and we colonels and captains were around the table.

Donald R. Lennon:

They didn't tell you what kind of contingency you were working on?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, that's right. It was an unreasonable sort of thing. It's like that old saying, "If you want it bad, that was the way you would get it." Connally defended us and what was interesting was the way McNamara handled that meeting. He treated everyone as if they were nobodies. That was an interesting experience.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, was it just a general exercise or was there some real reason?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, McNamara was that kind of guy. He knew what answers he wanted. If you weren't solving the problem to prove his answers right, then you went back and resolved it. You worked on it until you got the answers he was looking for, right or wrong.

I went from there to be War Plans officer on the Commander Second Fleet. This was also Joint Task Force 5. The flagship was the cruiser, the NEWPORT NEWS. I joined the cruiser over in Kiel, Germany. We did a little NATO exercise there. While we were over there, the admiral and the staff, including myself, were ordered to fly back. We went into Greenland, caught a flight back to Norfolk, and started planning the operations for the Cuban Blockade.

Donald R. Lennon:

I was wondering whether that exercise you were involved in earlier was background planning for how to deal with that, given the situation.

Joseph C. Spitler:

There was a relieving of command. Admiral "Corky" [Alfred Gustave] Ward took over before the operation took off. We were the last ship to clear Norfolk. We were told not to say anything about what was happening. After the relieving of the command ceremony, Admiral Ward called us into the flag mess. He said that President Kennedy was

going to issue an ultimatum to Khrushchev, to get the missiles out of Cuba. We would be prepared to sail Sunday evening, directly after that announcement on television. Well, we had the wives come down to the club, and after the announcement, we said, "Bye-Bye" and got aboard the NEWPORT NEWS. There wasn't a ship left in Norfolk, which was a strange sight, because they had all been deployed.

There was a funny thing that happened during this time. A ship was finally coming through with missiles on it. They were going to test the blockade. It was the MARCULA. It was going to come through the blockade where one of our destroyers was located. I have forgotten the name of that destroyer, but it was decided that the USS KENNEDY should be shifted over to that position so that the USS KENNEDY would be the one to intercept. There was some public relations going on there. On top of that, they had a people-to-people program where they handed out balloons and buttons and other things to people on the MARCULA when they went over.

I was then ordered to command the USS TIDEWATER, a destroyer tender. The most interesting facet of that tour was when we were ordered to be the station ship in Naples. We had the motor pool and the boat pool. To keep ourselves from going mad with things to do, every Sunday we would take a trip out to Ischia or Capri. To the people who entertained us ashore, we would return the favor by taking them out there with us.

My final assignment was at the University of Illinois, as a professor of Naval Science. I stayed there for two years, from 1965-68. Then I retired, and I went into the insurance business.

I started to get into the educational business. I was invited to be the Associate Dean of Students for the University of Illinois. The University Senate, made up of the heads of

departments and deans of the colleges, as well as the chancellor approved it. The president approved it, but it was vetoed by the president of the student body. This was during the Vietnam Era, when military were definitely persona non grata on campuses and she decided that she was going to have no part of my being assigned as Associate Dean of Students.

Donald R. Lennon:

She had veto rights?

Joseph C. Spitler:

She had veto rights. They didn't dare do otherwise. I decided if that was the way they ran that kind of railroad, I would do anything else, even sell insurance. So, I've had a career in the insurance business, with Equitable since 1968, doing mostly estate planning, and business insurance planning and retirement planning.

Donald R. Lennon:

It's probably more rewarding than higher education, anyway.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. It's a tough career, but it offers a lot of independence. I got my Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) degree back in 1975. That's kind of like a CPA and it's been very rewarding. I have made a lot of fine associations. As a matter of fact, I'm still working in it. The folks I've taken care of through the years say, "You're not going anywhere. We want you here when we need you."

Donald R. Lennon:

Is the insurance industry as shaky as some of what we read right now?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, it's had its blows, there is no question about that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Equitable is the one that has had some blows.

Joseph C. Spitler:

That's right. What the buying public demanded was that the insurance industry develop more products with a greater reward, a greater return on the premium dollars they are putting into it. Well, it is a basic rule in the financial world--the greater the reward, the greater the risk. Back in the 1970s when there were high interest rates, people were demanding that we get products that reflected those high interest rates. All of a sudden,

those rates plummeted and we had obligations called guaranteed interest contracts that involved millions and millions of dollars. We met those obligations, but it was reflected adversely.

Another problem is all of these beautiful office buildings that are vacant. We see this in Washington, D.C., and all around the country. Well, guess who financed those? The public demanded that the financial giants, the insurance companies, finance those, take mortgages on them, etc. Now they are left holding them. They'll come back we hope. That's what we would all like to think. When they do, that will put the ratio of capital assets back in good position. Unfortunately, there is an overwhelming urge in the media towards sensationalism. If they can find something that will really sell a newspaper, I don't care if its the Wall Street Journal, the El Paso Times, or the Annapolis or Washington papers, they start doing articles. What they've done is singled out factors where there are junk bonds on real estate investments. However, if you read the analysis by the Fellows of the American Society of Actuaries and look at the whole picture, they are not all that bad. Unfortunately, as a result of that scenario, it's given the press some sensationalism that has sold newspapers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Thinking back over your career with the Navy, are there any other anecdotes or what we normally refer to as "sea stories" that are lurking?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes. There is one that I've been debating whether I should get into, but since I won't mention any names, I guess it will be all right.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, on this type of thing the names are frequently used.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, I'm sure you have heard of the Caine Mutiny.

Donald R. Lennon:

Oh, yes.

Joseph C. Spitler:

I was in the middle of the developments that resulted in the material that was used for that novel. I was in a destroyer, and we had a squadron commander who was tough and incompetent. Now, maybe it was not entirely due to his fault. The assignments he had prior to that time were not appropriate for him to be a destroyer squadron commander in the Pacific during those operations. There were things that happened on the ship, and we had an ensign aboard who considered himself an author--he was a friend of Herman Wouk, the author--and he would fire this material back.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kinds of incidences?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, like the cupcakes. In the Caine Mutiny, it was the strawberries that were stolen.

Donald R. Lennon:

Yes, strawberries.

Joseph C. Spitler:

In our case it was cupcakes. We had all gone to general quarters. This was before the turkey shoot in the Marianas. Japs were everywhere. I was an executive officer in my battle station combat information center. The commodore's stewards mate came into CIC, white as a sheet. (That was not his natural color.) He said, "Mr. Spitler. Mr. Spitler." He kept stammering. I said, "Spit it out." His name was Williams, and these things were so traumatic to him. He said, "Somebody done stole the commodore's cupcakes."

Well, pretty soon the commodore is in the CIC and he had a very distinctive way of getting into these subjects. He didn't roll a steel ball, but he licked his fingers and then rubbed them. He said, "Well, God damnit, what's going on here, what's going on here?" I said, "Well, I know something is wrong." Well, anyhow, he said as a result of that he took his steward's mate, his cook, his orderly, and his messengers off of their battle stations to guard his food whenever we were in general quarters.

That's just one of many stories. Throughout those months, there were things that

happened that were parallel to that. On one occasion at Mindoro he froze. He was the squadron commander, but when the action started and the ships were in, he just froze. A squadron operations officer and the skipper had to take over. That's when FDR, Jr., called up and said, "What's going on here?" in that distinctive Rooseveltian tone. "Why isn't somebody ordering somebody to stand by these heavies that have been hit?"

The first evidence was when we came into Ulithi. We were getting the mail and the New Yorker magazine came aboard. The beginning of some of these tales were being told in the New Yorker. This incident went back to New York after the war was over and was apparently collaborated. I left the ship after the Iwo Jima operation, before the Okinawa operation. Before I left, the skipper told me, "You know, Joe, I don't know what I am going to do. I've got a real problem here." Later on I heard that he and the operations officer went over to Halsey's flagship, after the Okinawa operation, to report this and they got cold feet. They returned to the ship and sent a message. The operations officer had a close friend on Admiral Nimitz's staff and he sent his friend a letter explaining this, telling him what they had in mind. They got an operation message back from this guy saying, "In reference to your letter, do nothing. Repeat, nothing. There is an event that is about to occur that will bring all this thing to an end. Just keep yourself out of trouble." That's where the real life scenario ended. Of course, in the novel they went on to the trial and everything.

Donald R. Lennon:

What did actually happen?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, the war ended and they never did anything about it.

Donald R. Lennon:

I thought maybe he was going to be removed.

Joseph C. Spitler:

No, you see that's a big problem in the service. When you've got someone who you feel is absolutely incompetent and should be removed, if you are a junior officer, you really

have a bear by the tail.

Donald R. Lennon:

Exactly.

Joseph C. Spitler:

I debated whether that would be the sort of thing we ought to get into. When that book came out, I picked it up and started reading it. I said, "This book is not fiction."

Donald R. Lennon:

You recognized it immediately.

Joseph C. Spitler:

I reflected back to those articles that appeared in the New Yorker while we were out there. That told me that I wasn't reading fiction. Later, I confirmed with this operations officer that it was the whole story. That's probably the biggest anecdote that I can recall. There are a lot of little things here and there, but that was probably the most significant one. It went on for so many months and then to have it accounted in that novel.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said they got cold feet when they went over to report it. I presume they had an appointment with the admiral.

Joseph C. Spitler:

It's my understanding that they didn't have an appointment. They went to the flagship and they were going to see the chief of staff and tell him why they wanted to meet with the admiral. They hadn't made a commitment of an appointment. To my understanding, they went over to the flagship with the idea that they would see if they could meet with him. Then the operations officer thought, Maybe we had better test this with my friend.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did a situation like that impact on the rest of you officers?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Well, it was tough. At the time we were in Leyte Gulf, the commodore put out an order saying that no one was allowed to have beards on the ship, because it was a fire hazard. I was the executive officer. The skipper said to me, "Joe, this is one of the things that these guys have to do in the form of amusement. Here's what you do. Arrange a watch

list so that anyone who is around the commodore is clean shaven." This included the people on the bridge, in the radio shack, and his boat crew. I said, "Aye, aye, Sir."

Well, we were in Leyte Gulf one morning and the commodore had an appointment over on the flagship. Just before he was supposed to go we had a red alert. Enemy aircraft had been sighted and were closing. We were at general quarters. The commodore said, "Where is my boat? I've got an appointment with the admiral." Now here we were in the middle of red alert!

We were anchored, which makes you more vulnerable in Leyte Gulf and we had Japanese aircraft closing. It didn't make any difference, because he had an appointment with the admiral. He was going to go. The admiral probably would have said, "What in the world are you doing over here?" So, as luck would have it, we had to get the standby boat coxswain because the regular boat coxswain had a more important battle station. I bet I don't need to tell you what the standby boat coxswain was wearing.

Donald R. Lennon:

A beard.

Joseph C. Spitler:

A great big handsome beard. Once the commander spotted that he came to me. He licked his fingers and said, "Well, XO." (From that day on I never called any of my executive officers, XO.) "Well, XO; well, XO; God dammit, what are you trying to do? What are you trying to do?"

I said, "Uh, oh, what have we done now?" And he told me about the beard. Here we are, I am the officer in charge of the combat information center and we got these bogies closing and I run into this. I had read in novels where someone was so mad that his eyeballs were spinning in his head and he was seeing red. I thought that was something some literary genius made up. Not so. I had the strangest sensation of my eyeballs just spinning

in their sockets and I picked my helmet up. I didn't know whether I was going to hit him with it or not. I jammed my helmet back on my head so hard I almost knocked myself out.

When the captain got word of what had happened he said, "Okay Joe, pass the word over all circuits, `Everybody with a beard or mustache, off with it.'" So we passed that out. Immediately our doctor came out of the wardroom. His battle station was in the ward room, where he would do any operating if necessary. He had grown the most handsome, waxed handle-bar mustache you ever saw. It must have been two or three inches on both sides. He came out with his eyes flashing and that mustache was twitching like a fan. I said, "Off with it surgeon, and get out of my way."

We pulled into Ulithi, I guess it was. We had been firing an awful lot and we had a lot of empty brass from the five inch 38s. They were stacked up on the boat deck. Well, he came in again with his routine. He said, "What are you trying to do here? Kill us all?"

I said, "What do you mean, commodore?"

"Well, you have all this brass up here, topside," he said. "What if we get attacked?"

I said, "We were going to off load it on the ammo ship tomorrow." He said, "Well, suppose we get attacked tonight? Get rid of it!"

I said, "Aye, aye, sir." I had the crew go up there that night and toss all of them over the side. Maybe I don't need to tell you, but when we woke up the next morning they were all floating. The bay was full of these empty cartridges. Little things like that kept us on our toes.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you respond to the commodore on the beard business?

Joseph C. Spitler:

After knocking myself in the head, I said, "We'll correct it. Whatever that regular coxswain has, get him off his battle station." We just hoped the Japs picked somebody else.

When we were in Manus, some of our troops got into a problem over at the beach. Of course, when those things happen, the skipper gets relieved. If the skipper gets relieved, the executive officer gets relieved. We were threatened with that. I give this commodore credit; he stepped in and defended us against Commanders Destroyers Pacific who flew out to Manus.

Donald R. Lennon:

What kind of incident?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Our people were over on the beach longer than they were supposed to be. They had a little altercation. One of them stabbed the other, good friends. I don't know, you can't explain these things. Unfortunately, this skipper of ours, who was a real battler, was agitating these folks at the shore base CPO club. He was a heckler. The fact that he was there, and got involved in it, got ComDesPac's attention. When the skipper left the CPO club, he went down to the piers making the Marine guards think that there was some one down there stealing the goods on the pier. It could have got him shot. He was just that kind of guy. He loved to fight.

Donald R. Lennon:

He was sober during all this, I take it.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, he was always sober. He might have had a ton to drink but he was always sober. The beer and liquor were kept locked in the hold, but after a big operation, we were allowed to take it ashore. We would go over to the beach and he would drink you under the palm trees. The next morning, I'd think, He will be out and I'll get some work done. It never failed, at the crack of dawn he was up saying, "Hey Joe!" He was a very confident fighter. He said the shore people had an hour longer leave than the ship's personnel. My skipper said to me, "Joe, you make our liberty expire the same time theirs does."

I said, "Aye, aye, sir. You're the boss."

He said, "My people have the right to just as much liberty as any." It was a combination of things that unfortunately got ComDesPac's attention. This commodore stepped in, so I'll give him credit for that. He gave us a lot of hell, but he sure did save our hides.

About every other day, the commodore would line up all the stewards' mates and pick another one. Each guy would last a day or two and the commodore would throw him out for some reason. We would line them all up and he'd pick out another one. Well, we didn't have that many stewards' mates. Finally, one kid kept sticking. The skipper and I were laughing in the boardroom one day and we started talking to this kid. His name was Williams, he's the one that told me about the commodore's stolen cupcakes. The captain asked him, "How come you and the commodore get along so well? He's been choosing you and keeping you longer than any other."

He answered, "I don't know, skipper. The only thing I can think of is he's a country boy and I'm a country boy." That was the most on-going event that had an impact on our lives.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine the pressure though was constant.

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes.

Donald R. Lennon:

Some people could not deal with the responsibility of command.

Joseph C. Spitler:

As the war was winding down, we would have twelve or sixteen carriers and Halsey would get them all in one unit, just to flaunt our power at the Japanese. We would have all of the battleships, the cruisers, and hundreds of destroyers in this huge screen and refueling operation, plus the tankers.

Donald R. Lennon:

Sitting ducks, if the Japanese had had capability of doing something about it.

Joseph C. Spitler:

As far as the operational commanders were concerned, like this guy, the screen commander, that was a big job. He had to keep the antisubmarine screen intact, while sending destroyers back to the position behind the tanker as guards. That was in case anybody fell overboard. Moving up alongside and keeping that thing going from dawn to the wee hours of the night, that's pressure. Never mind the combat aspect of it. Junior officers like this young ensign, you could laugh at him all you wanted to. He was a reserve officer. He felt that the regular officers were a bunch of dummies, in a sense. That didn't happen very often. I might say that the relationship between the regulars and the reserves, by and large, was super. Like this reserve operations officer from the squadron, you couldn't find a better one anywhere. One day we were somewhere in the South Pacific after one of these battles. Our motor whaleboat had been abandoned from one of the ships that had been sunk. We wanted to get rid of those floating objects, for a lot of reasons. We were ordered to sink this thing. They were unsinkable. They had these airtight tanks made of heavy metal. These gunners mates were firing at this thing. This ensign said, "A bunch of dumb regulars, they don't know what they are doing."

The captain said, "If you think you can do it, go up on the fo'c's'le and take care of it. I'll be happy for you to do it." He got up and as he is pulling his forty-five out of the holster it went off, shooting him in the leg. This proved the regulars weren't the only ones that could pull a dumb one.

That is about the sum and substance of my naval career, which had been great. Now, I have gotten a second retirement--retirement from the Navy and retirement from my company.

Donald R. Lennon:

Are you ready to enjoy it?

Joseph C. Spitler:

Yes, but I'm still working.

[End of Interview]