| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #108 | |

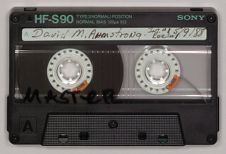

| Commander David M. Armstrong | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| May 9, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Donald R. Lennon:

Commander Armstrong, I know you entered the Naval Academy from the Washington, D.C., area. Would you give us some background on your Life where you were born, where you grew up, the nature of your early Education and we'll take it from there.

David M. Armstrong:

I was born in February of 1919 in Washington, D.C., at the Sibley Hospital. At the age of two, my parents built a small home and we moved to a little village called Cabin John Park, which is just outside of the Washington, D.C. area, just beyond the big Glen Echo Amusement Park. That's where I grew up.

I was quite precocious as a young child. I'm told that I was reading little primer books at the age of three. The local schools were not acceptable to my parents considering my precocious situation. My father, fortunately, was a civil service worker (an engineer in the Department of the Navy) in Washington and because of that the law allowed me to attend the Washington, D.C., schools. As a result, I went

to an elementary school inside Washington, D.C. It was called Reservoir School. I got way ahead of myself. I ended up being seven years old and in the fifth grade. There was no facility at that time Armstrong, for what now are called gifted children. My parents put a stop to this because socially, I was way out of my league.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were in the fifth grade when you were seven!

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. They would pass me. I would go in and do the spelling, reading, and arithmetic and they would say, "Well, you go to the 'B' class." They had it divided into the "As" and "Bs." I would do that for a month and then they would say, "You ought to be in the third grade." Off I would go to the third grade. I just kept progressing like that. Socially, I was completely out of it. I was just a little kid and all the other guys were big and strong.

I continued on in the Washington, D.C., area schools at Gordon Junior High School and then at Western Senior High School. There again, socially, I just was not a part of the activities at all. Academically, I was fine. I graduated at the age of sixteen, and for reasons unknown to me, I was beginning to think about a service academy. I think I had comprehended that a fine education was available and that it would not be unduly expensive for my parents who were not rich. I began listening to football games on the radio and I first thought about going to West Point. But my father was working with the Navy and, gradually, I was inclined to the idea of trying to go to the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

Since your father was an engineer with the Navy, did you spend much time in the Navy yard, sitting around Naval officers?

David M. Armstrong:

No. My father had a number of friends who were Naval officers. Admiral Rickover, who was then Commander Rickover, was the head of the section in which my father served as a civilian, and he and my father were great friends. Rickover used to visit us out in our home in Cabin John and we got to know him. My father also knew and liked Rollo Wilson and Ray Spruance. I had an acquaintance with them but that wasn't the major influence. I think the major influence was the glamour idea. In Washington, D.C., at that time, the Naval Academy got an awful lot of publicity. It was really considered an elite organization and institution. The papers were always full of events at the Naval Academy.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was in the mid thirties?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, the early and mid thirties. By the time I could make any serious moves toward a service academy, I had pretty much moved over to the idea that the Naval Academy in Annapolis would be better for me than West Point. Having graduated from high school at sixteen, I was too young to go with the next class. Because of my small size and young age, I was not involved in the social and athletic activities in high school or college. Therefore, I concentrated on the Boy Scouts. I became an Eagle Scout and an Assistant Scoutmaster.

My father tried valiantly with Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland

and our local congressmen to get me a congressional appointment. The best he could do was a second or third alternate which never came to pass. To pass the time and become eligible age wise, I went to American University in the Washington, D.C, area. It's located on Massachusetts Avenue in suburban Washington. I went there primarily because of Dr. Shenton, who taught freshman math and was an emeritus professor of math at the Naval Academy. Dr. Shenton knew my ambitions and plans. He gave me a little extra help and a little extra understanding. I took the straight academic freshman course: physics, chemistry, math, American history, and Spanish. (I had taken French in high school.) I completed my year there and had not yet had any luck with an appointment.

My father was, by this time, active in the Naval Reserve contingent in Washington. He had gone on some cruises and was very wrapped up in and active in the local group. He learned I guess it was not difficult to find outthat anyone who had served in the Naval Reserve for a period of a year could take a competitive examination for entrance into the Naval Academy. There were twenty five appointments available each year for the people who stood highest on these examinations. So I joined the local Naval Reserve unit at Washington Navy Yard. I had to be in a year before I could take the exam, so I think two days after my seventeenth birthday, I joined. While I was in the Reserve, I attended drills regularly and took a cruise on a destroyer, the old TARBELL, a four piper, down to Guantanamo in the summer of 1936.

Donald R. Lennon:

TARBELL was the name of it?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. It was the TARBELL. She was DD242 or something like that, a fourstacker. I went down to Guantanamo on our two week training cruise. That was my first taste of being in the Navy and at sea. I became eligible then to compete for an appointment to the Naval Academy through the Naval Reserve. All the while, I was going to American University, learning a lot, but accomplishing very little as far as getting into the Naval Academy. Had I not been in a competitive exam situation, I would have been given credit for those courses and could have gotten into the Naval Academy without taking the entrance exam. That was one of the rules. I had completed enough subjects with adequate marks I stood awfully high in everything, I was a bright kid to have gotten in, had I not needed to take a competitive examination to win an appointment.

There were several schools in the area that were excellent in preparing young men to take the competitive examination. My father prospected around and discovered that the school with the best record for that sort of thing was the Columbian Preparatory School, where a number of my classmates went. Guys like Jack Beardall, and "Stew" Daubin all went there. They were good. They were excellent. Most of the guys I knew real well were sons of military officers who were competing for Presidential appointments. There were twentyfive Presidential appointments each year to the Naval Academy, twenty five

Naval Reserve appointments, and twenty-five from the Fleet. All were on a competitive basis. So I went to Columbian and got to know all these guys who were headed in the same direction. We were deadly serious. We were deadly serious. We studied and we worked. I can remember Jack Beardall and Bill Daubin and I, once a month or maybe more often, would go out to the Army Navy Country Club and take dates. This would be on a Saturday night. We would go out there and order a pitcher of beer and set it in the center of the table. We would each have a glass with the girls. They always had a band and we would dance. But we also studied. Let me explain. While we were there, the system for learning that the prep school used was flash cards, 3" by 5" cards. You made them on your own and they were numbered for subjects like Ancient History and American History. We would have these stacks of 3" x 5" cards that were five and six inches deep. On one side would be a date or place or name and on the back would be the answer. We would go there to the Country Club to this dance on a Saturday night with dates and a pitcher of beer, and we would have our pockets full of these damned things; and we would hold them up and answer the questions. This was a learning mechanism. We were deadly serious. We were not playing around.

In the last four or five months of the course, which started in September and ran though to April when the competitive exams were held, we started taking every Saturday morning at least one, generally two, previous Naval Academy entrance exam tests. We would take them in

history, mathematics, algebra, whatever. The faculty got them from somewhere. I don't know but I presume they were perfectly legitimate. We would take them not only to get the information in our heads, but to learn the technique of how to take these exams. It was a cram school and I mean we crammed.

I can recall that the school ended about a week before we sat for the exams. I brought home every book I had and I had flash cards all over my little desk in my room at home. The first day I was home was Saturday and at eight o'clock in the morning, I got all those books out to study. I stayed in there about a half an hour, and then wandered out into the living room. My father was home and said to me, "Davy, you're supposed to be studying. What the hell are you doing in here?" I said, "Dad, I don't have to study. I know it all. I know all the answers." He believed me and didn't insist otherwise so I took the week off. I took the exams and I stood number one in the country. I averaged 3.8 and that was because I got a 3.4 in English where we had to write a composition. I got 4.0 on every other subject. I have a nice Presentation watch at home as a reward. As a result, I won an appointment with the Naval Reserve. My only real competitor at school on those exams was Frank Leighton who was a bright guy. He was number one on the Presidential appointments, but he only averaged 3.7 or something and I averaged 3.8. I beat him and I was number one.

Then it was off to the Naval Academy to enter in June. My parents

took me down. I had to take a physical. I took a pre appointment physical at the local Naval dispensary, I guess it was. They said, "Yes, he's okay." Then I had to get my final physical at the Naval Academy. I had a wicked cold that day and did not pass. I had a temperature of 102 degrees. I couldn't read the chart because I couldn't see it. I went back home brokenhearted. My parents were so upset. We got a local doctor and nurse to doctor me up and I went back in three or four days and passed with no problem. My temperature was regular and I could see the chart.

I entered about four days later than the first group that went in which included all my of prep school buddies, Jack Beardall and "Stew" Daubin. Then the regular plebe summer began. God, I was excited. I loved it. I just absolutely loved it! The discipline and the fact that we had accomplished this and were actually there and that we were sworn in as midshipmen absolutely delighted me. We had just basic indoctrination with very little academics during plebe summer. It was spent learning how to march and do elementary sailing, and playing sports. There was a good athletic program during plebe summer.

Then the academic year came along and we started in. I'm sure everyone knows pretty much how that worked. The system was that you learned from the books and from the assigned lesson prior to going to class. When you took a class, you recited what you had learned. There was no teaching process in the classroom. It was simply an examination

process. For instance, in mathematics, you walked into class and the prof, a lieutenant in the Navy, would say, "Gentlemen, draw slips and man the boards." You would go up there and draw a slip telling you what the problem was. You would get a section on the board and you would solve the problem and then you would go and sit down.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you have any thoughts about the quality of the facility? You said there was no real instruction involved. Should there have been?

David M. Armstrong:

I don't know. I'm still until this day undecided about that. There were some civilian profs there who had fine qualifications in their disciplines. They were pretty much the supervisors and the heads of their departments. The others who came in were of the rank of about lieutenant. They were just detailed there at the Naval Academy as instructors. I think they did a good job of staying one day ahead of the class. They did not teach at all, however, they simply supervised recitations.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wouldn't the Academy have been well served to have a first rate faculty all the way through?

David M. Armstrong:

I don't know. I'm still undecided on this and I've thought about this many times. We had small sections. There would be ten or twelve of us and we would go into our classrooms, which were not very big, and sit at our desks. We recited either orally, standing up, or on the blackboards, and we were each told what we had done wrong. That was the only teaching that the profs did. They'd put a big "X," and give you a

2.0 for the day. They'd say, "Well, I'm putting you down for a 2.0, Mr. Armstrong!" This led me, and I think most of us, to study in advance and go to class prepared. We learned from excellent textbooks the things we had to know. We went in for facts. It was not a liberal arts education. We did not discuss the philosophy of the French Revolution or anything of that sort. We simply noted the date it started, the major battles, and when it ended.

Donald R. Lennon:

No "why," all "what"?

David M. Armstrong:

Very little "why." I think I learned an appreciation of history and current events from the book. We studied it so that we could go in and if the man said, "When did the Battle of Austerlitz occur?" You could say, "1809, October 14." (That's probably wrong, but it's close.) This backgrounded us. It was not a liberal arts education. It was strictly a factual education.

About once a month, we would meet in the auditorium at Mahan Hall where the civilian heads of the departments, who were well qualified in their disciplines and were distinguished educators, would give a lecture. This was relaxing. We would go in there and lean back and enjoy. We would take it all in because there was a quiz at the end, but it was a relaxing time.

We studied and learned facts, particularly in subjects like navigation and mechanical and electrical engineering. Philosophies and "whys" were not stressed. Instead, there was much more interest in the

facts and formulas to prepare you for doing a job. I think it was demanding in the sense that no material was given to us by a professor who stood up and talked, and maybe three weeks later would ask us to write an essay exam on what we thought was the reason for the American Revolution. There was none of that. We put it down like we read it. For what we were doing, that seemed to me like a good way of doing it. I still haven't resolved which is the better system. Of course, at the Naval Academy we had, with rare execeptions (I say this with due modesty), fine young men who were motivated. This was Armstrong, the late thirties. The Depression was still on. To get a commission and become a Naval officer opened up the world for you. This was something you had striven for. We were motivated right from thebeginning. There were rare exceptions of classmates who for various reasons, many of them philosophical, many of them disciplinary, and thers due to lack of aptitide for the academic material, left. Ninety percent of us were highly motivated. We were all WASPS (White Anglo Saxon Protestants). We were in there swinging. We really were. We weren't fooling one bit!

Donald R. Lennon:

What about hazing and harrassment by upperclassmen?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, we had that. It would start plebe summer when we had the second class there. However, the second class was billeted in the second back wing of Bancroft Hall across from Smoke Park, and we plebes were in the fourth wing. The only thing we had to do with them was at

formation time. I don't remember if they joined us at meals or had their own mess tables. I rather think they had their own mess tables and we plebes ate at our own. When we were in contact with them they were, as they should have been, very rigid, very stern. They were as highly motivated as we and they were as anxious to teach us as we were to learn. I didn't find that onerous at all.

During plebe summer, the first class and the youngster class were on their battleship cruises. They were gone the whole summer for three months. They got back in late August and went on September leave along with the second class. We stayed at school of course. When September leave expired in late September, the academic year started and all the classes came back. We were then all mixed together by battalions--some members of all four classes in each battalion. So your next door neighbors might be second class and those across the hall or down at the end could be youngsters. Then it could become a little nasty. Some were a little sadistic and could get mean. We didn't dare complain and I don't think anybody ever even gave a second thought to making an issue of it. We just took it and maybe wept a little or cussed a little and went on.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned that some of them were kind of sadistic. What type of thing would they so?

David M. Armstrong:

I won't mention his name, but there was one first classman who had a cricket bat. He was in my company. He lived right across the hall from my first classman, Andy Olah, Class of 1938. I can't recall now what some of my infringements were, but he would bring you in there and make you bend over while he whacked you with that damned bat. That hurt. I would go home with great bruises on my bottom. I was not his only victim, there were others. But I figured that was part of the game--that sort of thing. I never had any really onerous things happen.

At the mess table, if you did something wrong, either in the manner of etiquette when serving the first classmen, or you didn't know the answer to a question, or talked out of turn, (we were not allowed to talk), they would say, "Hit the air." What that meant was that you had to push the chair back and sit with bended knees. You sat where you were but without a chair. That could go on for a long time. It wore you out. It would mess up your meal so that you couldn't eat. But nobody worried about that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did they occasionally make anyone who did not perform well "sitting on the air" get under the table?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. They would send you under the table and you would miss the complete meal in that circumstance. I had that happen to me a couple of times. It was nothing that I didn't figure was part of the game. Hell, here I was a midshipman at the United States Naval Academy and being paid to go to school! I could put up with a whole lot of that. It didn't really bother me. I don't think it really did most of us. We all understood that it was part of the game and that there were some bad apples and there were some nice guys in all classes. If you were lucky, you would have a good guy like my first classman, Andy Olah. He was the head cheerleader and one of the nicest guys that you would ever want to know. He really took me under his wing and protected me. In return, I would go around and get him ready for formation and all that kind of stuff. If you had a protector like that and a really nice guy, you generally didn't run into too much sadism or anything. It was not onerous. It could hurt like hell for a day or two, but not enough to make you quit or make you cry or make you complain. You just did not complain, that's for sure. That went on. It gradually eased up as the year wore on. The new first classmen were feeling their oats. That was all right. I don't remember now what we did when we became first classmen, but we were probably very similar. We probably did the exact same things.

Donald R. Lennon:

You participated in both soccer and boxing.

David M. Armstrong:

I was always sports minded. I was too small physically, however, to be in football or basketball, although I liked both those sports. I had played them as a kid in a rinky-dink sort of way and enjoyed them. But in the elementary schools in the Washington area, we had soccer teams. That was our varsity sport, so to speak. (Of course, when you got on later to high school, it was all football. You didn't have any soccer teams.) So I had played some soccer in elementary school and was reasonably clever and quick. When I went to the Academy I went out for soccer and played on the varsity soccer squad for three years.

I had also done a lot of boxing as a kid. Here again, my lack of size and weight was no hindrance because it was all weighted. So when I went to the Academy I got on the boxing squad. I never fought a varsity fight but I was always on the list to fight or the next one in order.

Spike Webb was our boxing coach and he was a very famous man. He had been the boxing coach and a boxer with the Expeditionary Forces in Europe in World War I. That's where he had learned his skills as a boxer. He was a tough little monkey and a funny little guy. But we loved him dearly. Some of my fondest memories about the boxing team are of working out on the big bag. It was one of those that hangs down and is full of something. I would be working with those gloves, banging

away, when all of a sudden, this little head would show up on the other side of the bag. Obviously he had been holding the bag, and watching, watching, watching every move I made. Then he would sneak up on you. I was always pleased, however, when he came up and looked at me. This little noggin would appear around that big bag and he would say, "God dammit, do so and so!" He was a delightful guy.

The fights were always on Saturday nights in those days. Intercollegiate boxing was still a sport. Everybody always came formal, the men wearing black ties and the ladies wearing gowns. There was no applause or anything like that allowed. On Thursdays or Fridays, we would have the warm-ups for the fighters that were going to fight that Saturday in the various weight classes. I was at 119, which I guess was a feather weight. Johnny Shepherd (Class of 1939) was one of our best fighters. He fought lightweight, which was 125 or something like that. He was a hell of a fighter. On the warm-up nights Spike would say to me, "Well, Armstrong, I want you to go up there and warm-up Johnny for his fight tomorrow night." I would say, "Are you sure you want that?" He would say, "Yes, he won't hurt you and I know you can't hurt him." I would go in there and go three rounds with Johnny Shepherd. I earned my keep. We trained hard. For a while there, Spike had us up before reveille at five o'clock in the morning running around the academy grounds as roadwork. That was in addition to all the rest of the stuff.

We did a lot of bag work and all that. Spike was awfully good. He knew he wasn't as articulate as he might have been for an instructor or coach, but he really knew his boxing. He taught me how to throw a left jab, it's not an arm punch. That's no good. What you do is to punch from your right toe, get that arm straight, if you can, just before you hit from your right toe and whole shoulder. I could do it to a door and the door would shudder. That's what Spike taught us.

Bill Busik, who is the executive director of the Alumni Association, was on the boxing squad. I got to know Bill that way. He also played football. Whenever I send in a contribution or anything, I always get back a little note from him, "Dave, sure do appreciate the gift you gave us. Thanks very much. Sincerely, Bill Busik." That's a kind of fun thing.

In soccer, we had Tommy Taylor as our coach. He was a little Scotsman. He was a little bit of a guy, about the same size as Spike Webb, and bald-headed. He knew the game. He played the British style of soccer, which involved much passing and movement of the ball up and down the field as units, as opposed to the Latin style, where individuals get the ball and go racing away for the break-away goal. I was not first-string, I was second-string, but I got to play in several varsity games. I was in a game against Army and we beat them. I earned

my letter and I was real delighted with that. I also earned my letter in boxing.

One of the benefits of being on a varsity squad was being assigned to the training table at mealtime and not having to go to meal formation. You wore your white work uniform, your undress uniform, and went directly from the gym or the playing field to the mess hall and filed in as a single person. Of course, you still stood at attention at your table until all the preliminaries were over and everybody was seated. Being at the training table was always a blessing because, boy, you were tired. My God, according to today's nutrition news, what we ate on the training table was terrible. Oh, my gosh! We had huge beef steaks every meal, and bread with butter, and milk. Anyway, that was fun and it was a privilege to be on the training table and not have to go to evening meal formations and so on. I was on the training table for three years, I guess, or half of three years. The soccer training table lasted until November and then the boxing season would start and I would stay on for the winter.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do much sailing in the Chesapeake Bay?

David M. Armstrong:

Not too much on my own. I did the required amount as part of our seamanship courses. I sailed the half-raters and knockabouts as part of

those courses. We all went out on the yawls a couple of times. We had the VAMARIE at that time and one other I think. I didn't do it for recreation too often. Some of the guys did. They really enjoyed it more than I did. I took a date out on a little sailing venture a couple of times but nothing as regularly as some of the guys did who really enjoyed it and got to be good sailors. Our sailing team did very well intercollegiately. It was well respected.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there anything unique about your summer cruises? Or were they just routine?

David M. Armstrong:

We went to Europe on our youngster cruise. There were three battleships that went: the NEW YORK, TEXAS, and ARKANSAS. I went on the NEW YORK. We went to Le Havre, France, and then we had four days down in Paris. From there we went to Copenhagen, Denmark, and then to Portsmouth, I guess it was, and then from there to London for four days. This was an exciting and wonderful time for me. I really enjoyed it. Many of the guys had not done that sort of thing. I had that one cruise to Guantanamo for two weeks under my belt as a young reservist. That was when I realized that I was embarking on something really exciting--that it was going to be something more than a desk job.

In Paris they turned us loose for about four days. Can you

imagine! There were about a thousand of us on the two ships. They just said, "Here's your hotel reservation. Go! We'll see you back on the ship four days from now." My God! We grew up! Boy, I can still remember those shows in Paris. We went to Trente duex Rue Blond el. It was a whorehouse. The women were all naked. You could be sitting there having champagne or a drink or something, and they were running all around naked as jaybirds. They were beautiful women.

[End of Part 1]

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| June 10, 1988 | |

| Interview #2 |

David M. Armstrong:

During the Guadalcanal operation I was still in the ZANE and by that time, I think, I had changed jobs from communications officer to gunnery officer. We went with a large convoy of amphibious shipping via Samoa and Tongatapu where ships were assembling for the operation. Also, we went briefly down to Auckland, New Zealand and escorted a couple of ships up from there. They had some Marine detachment people along and we brought them up. The amphibious task force went south of Guadalcanal and came into what is now Iron Bottom Sound from the west. We split around Savo Island and the group going to the Guadalcanal beaches went to the right and we who were in the other group went, the Florida Island group, stayed to the left. I had written up pretty well in that manuscript of mine about the battle. Should I repeat that or will that stand on its own.

Donald R. Lennon:

It will stand pretty much on its own unless you can think of aspects of it that are not included in the article.

David M. Armstrong:

The only thing about it was that in going in that night, we went through the strait between Florida Island and Savo Island at about three o'clock in the morning as I recall. I'll

never forget it. It was absolutely calm and I'll never forget the perfume of the tropical flowers that wafted out to us as we went in. We had really prepared ourselves well for this thing on the recognition of aircraft. I had built a paper mache, using torn up bits of newspaper and flour paste, a model of this little island that we were to bombard. It was called Bumgano. We had trained extensively on that because we had no fire control as such. It was all local control at the guns and we tried to fire them in salvo so we could spot them. Having set the range and deflection manually on each gun and then we could fire a salvo. They threw their firing switches on to salvo and we did it from up in fire control. That way we could spot the fall of shrapnel. I don't know, we expended several hundred rounds on that beautiful little green island there and I didn't see a thing move or whatever, but there was on little shack somewhere in a kind of little ravine that we could see from the ship so we peppered that pretty good. We figured that if there were any Japanese there, that is where they would be, right in that.

I guess it turned out that there never had been any Japanese there, ever. We did that and boy, we were really primed for that. We wanted to do that as a kind of pay back for Pearl Harbor. Man we were we ready. That went on and we did that bombardment mission--it was a real tough thing. We had some other members of our squadron and they were peppering away at Gavutu Island and that turned out to be the tough nut in there. The Marines had to land. There was one battalion, I guess it was a Marine raider battalion or something that landed there and after a long and vicious fight, they finally took it.

About that time, when the Marines were landing on Gavutu, they kept a couple of ships there to help them. We went out on a mine sweeping mission and went down to the Lengo Channel and made some passes across in front of the landing beaches at

Guadalcanal. We found no mines but that is what Admiral Turner needed to know. He needed to know that he could use all avenues of escape and entrance to the area. We made a contribution toward that. The whole thing was that there was no opposition on the Guadalcanal beaches. The thing went pretty well. I described it in my manuscript there on the Battle of Guadalcanal. The Japanese made several air attacks, one of which involved Betty torpedoes. I guess they had been converted to torpedoes because normally they were medium range bombers. We had the word from the coast watchers that they were coming so we were ready. The fighter aircraft at Guadalcanal were airborne and ready. Instead of coming straight on down the straits, they went around the Florida island to the north side of it and attacked from our flank. Florida Island was only ten miles away from our position in the middle of the strait between it and Guadalcanal. They came in low and fast, not really fast because they were slow lumbering two engine things, and boy, we knocked them down all over the place. From the ZANE we knocked more down or did the most of it.

Donald R. Lennon:

You mentioned the coast watchers, were they civilian natives, or was that naval personnel staff?

David M. Armstrong:

They were Australian military personnel, as I understand it. They were put in there because Australia had mandated control of the Solomon Islands. They had administrative control to a degree. When the war outbreak came, and it became obvious that the Japanese were coming down that way, these guys were put ashore on these islands. They had some familiarity with the native tongues and native customs and so on. They were able to establish themselves using the natives also.

Donald R. Lennon:

These were the islands that were still under the control of the Japanese, were they not?

David M. Armstrong:

They were not under the control of the Japanese, no. They were islands that were still in the wild. Virgin. They hadn't been touched by anybody. Such as up around Bouganville and several others like Vella LaVella where the Australians had put in coast watchers. They would simply scan the skies and report on on-coming raids when they were coming down. They had radios and their information was relayed to us from base stations in Australia. I don't know. We had the word in the task force that the coast watcher reported forty Betty's east of Vella LaVella at such and such a time headed southeast. That was the word so we were all ready for the. They continued to be our basic early warning system throughout the whole Solomon campaign till we pretty much wrapped it up.

Donald R. Lennon:

Where were the Japanese flying out of?

David M. Armstrong:

They were flying out of Rabaul at that time and to a limited extent Kavieng I think. But Rabaul was the main base. They may have had some people coming out of New Guinea but I'm not sure. Rabaul was fed, on the Navy side, by Truk, which was a major fleet base for the Japanese. They sent aircraft and ships down from there. That was in the battle for the Solomons. The first day that we had the famous battle of Savo Island in which the Japanese came off clear winners but they never did take advantage really. They sank a number of our cruisers and a couple of destroyers and escaped almost unharmed and they didn't take advantage of the situation really. They were wide open to the transport areas where all the troop ships and the supply ships and the screening destroyers were. We were mostly DMS's and APD's and had very little fire power. They could have come in and just really ripped up the pea patch something fierce. But they didn't. I don't know why. I think they got a little frightened at the very end and pulled out and didn't really cash in. In any event, that was the end of that.

We never did any minesweeping. We were escort ships for various echelons of supply and troop ships that came up from basically New Caledonia or Espiritu Santo. We would go back to Espiritu Santo and on the way up pick up troop and supply ships and to take them to Guadalcanal. We were just anti-submarine escorts. On that basis, the U.S. Navy was really on the run because we didn't dare stay in there over night. The ships waited at the entrance of Dispensable strait and Lengo Channel until the Japanese quit bombarding Guadalcanal in the night. That ended and then we would come in, off-load, and then beat it out before the night came on again. This is what was going on and it was a pretty sorry thing. The Marines on Guadalcanal, particularly the air effort for the Marines was being hampered quite a bit primarily because of aviation gasoline. They simply were running on a day-to-day basis. They didn't have any reserve they could use for more than three days in advance. That was the whole key to the logistic effort.

Donald R. Lennon:

The ZANE was used to transport aviation fuel in?

David M. Armstrong:

That's right. That was the final thing I did in the ZANE. We took up a load of fifty-five gallon drums, a deck load of them, of aviation gasoline. Had we been hit, we would have just gone up like a torch. On that same deal, we took up PT-boats. We took up the first PT squadron that went up. We towed them behind like water skiers. We had manila towlines and we towed these two behind us just like water skiers as we went up. We turned them lose and they later did famous things and whatever. We, again it's in my article “American History Illustrated” about the battle of Sea Lark Channel, got into an awful scrap there. We got walloped up pretty good. As it turned out, I already had my orders to leave the ship and go back to new construction.

Donald R. Lennon:

On the Battle of Sea Lark Channel, did they have any explanation for why you

didn't get beat up more than you did considering the superior force you were facing? You had only two ships there as opposed to three Japanese ships with greater firepower and greater range and everything else.

David M. Armstrong:

The only reason is that at the ranges that we were firing and they were firing at us, was in our limiting range which was thirteen thousand yards. They were firing at about fifteen thousand yards which was close too their limiting range. That means that they had to get high projectory, which a plunging pattern of projectile fall. It was plunging and when it was coming almost straight down. We in the ZANE had a beam that was only about fifteen or twenty feet. We were slim little guys. We were within their dispersion pattern. You know what a dispersion pattern is from a battery of guns. If they fire five guns, well they won't all come down at exactly the same place. We were sitting right in there all the time. The decks were wet and our rigging was cut down. The splashes would just come up over us and inundate us. It was just sheer luck.

Donald R. Lennon:

Your beam was just fifteen feet wide?

David M. Armstrong:

I don't know, maybe I exaggerated that. Maybe it was twenty feet. I don't recall the exact dimensions. Don't hold me to that. You would have to look it up in the specifications book. It was slim and long so that was the major thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

And lucky.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes and lucky. We finally did get hit and it hit us on the place where it did us the least harm structurally and that was on the chase of gun number three on the galley deckhouse. I think another reason we didn't get too beat up by that particular round that hit us was because I think it was a shore bombardment round. It was an impact explosion round so it did not dig in at all. Ii had been an armor piercing or a normal; we would have

had the damned thing go clear down into the galley and so on. But it didn't. It hit on the chase, which is the hard part of the gun that goes back through the recoil tube. It hit right on there and went all over the place. It killed a number of people; obviously, in the gun crew and it wounded a lot of them.

About the time that they were really beginning to zero in on us, we were within the pattern every time that they fired a salvo. They were firing about every ten or fifteen seconds to three different ships. We were the lead sip of the two. The TREVOR was following us. They picked us probably thinking that the officer of tactical command was in our ship. He wasn't. They were on. Their spotters must have just said, “On, on, no change. No change. No change.” The decks were wet and it was a mess. We only got hit one time, which I think was by the shore bombardment ammunition, which they brought in.

It [The Marines] had been trying to get some planes off. It had rained the night before. They finally got some dive-bombers off. We could see them. They started coming down on the Japanese ships. The Japs shifted to anti-aircraft fire instead of aiming surface fire at us. That was the thing that did it. If they had kept it us another ten minutes, the law of averages would have been against us.

Donald R. Lennon:

When they spotted you, had they been in route to bombard Henderson Field or something?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. That is what their mission was.

Donald R. Lennon:

You caused a diversion.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. Samuel Eliot Morrison, in his description of that fight, say that the two little ships, "two little boys," diverted their effort and by their efforts changed the outcome of the whole battle in a way. At the same time the Japanese carriers were coming up in the

islands, where the HORNET was sunk. It was part of a big operation. Part of that operation was to keep the aircraft from Henderson Field from getting off. That was their mission. They got sidetracked with us and I'm sure, when they first saw us coming out of Tulagi Harbor they thought we were coming out to take them on. We had to go toward them on account of the reefs and so on. We attempted to get down to Lengo Channel and turn left and go out. We had to go right for them, not directly but closing at a rapid rate. I'm sure they thought they were going to come out to take them on and fend them off. We didn't have in mind at all. We were just getting the hell out of there. That's all explained in my little thing there. I had already had my orders to go back to new construction. We got back to Espiritu Santo.

Incidentally, we went in there and there was the COOLIDGE. It was a big merchant ship converted into a troop carrier. It had sunk just in the entrance channel. Anyway, we came back to Espiritu Santo and found that our orders were to fuel and take on eight thousand more fifty-five gallon drums of gas and then go back. The Marines had to have that gasoline. They were operating on a day-to-day basis. The skipper looked at me, Pete Wirtz, and said, "Damn guns. Dave, (or whatever he called me) I'm going to let you go. I don't want to take you up there and subject you to this all over again."

He put me off and I grabbed my footlocker and my suitcase and took off. I spent the next day on the airfield of Espiritu Santo, the army airfield (it was not a Navy one), in getting a ride. The only place that they were going to was New Caledonia so I got a ride the next morning. I lived in a tent over night and then got a ride down to Noumea in New Caledonia. I got down there in a matter of hours. There was a tent village for transients down there in Noumea and I finally go passage back too the States on the LURLINE. She

was one of the Hawaiian ships.

Donald R. Lennon:

One that you hear the most of.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. By that time she had been mostly converted to a troop ship. My rank then was lieutenant jg. There were four or five, four of us I guess who were all assigned to what had been one first class stateroom. They had just taken out the regular bunks and put in double bunks and so forth. I believe there were six of us of about the same rank to go back to the State in the LURLINE.

Donald R. Lennon:

This was in the fall of 1942?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, about early November, 1942 roughly. We got back to San Francisco. We traveled alone without escorts because the LURLINE could crack up enough speed so that basically, with the submarine capabilities in those days, unless you just happened to be in the right place. . . We were going across a trackless part of the ocean from Noumea to San Francisco. Unless a submarine happened to be sitting right in front of you when we were going at twenty-eight knots or whatever, there was no way that he could ever catch you. If he wasn't right ahead of you when he saw you, he was out of the picture anyway. He never could catch you. He could never get into firing position. We went without escort and arrived. I went back to my home where my parents were living in Washington, D.C. I had ten days leave built into my orders and I went (you know, I we went into San Diego, not San Francisco) back to Washington, D.C. I had orders to go to the gun factory for gunnery school to learn how to do the five inch thirty-eight battery. That was fine because it was right there in Washington so I lived at my parent's place for a month or two and went to the gunnery school at the gun factory. While I was there I was promoted to lieutenant. That was a joyous occasion. What they did in those days was to assign you to a ship after you

had already come back to the States because they had no way of knowing in advance what your timing was going to be. When they got you back into the States and started you on the gunnery school then they knew exactly what time you were going to be ready. I was assigned to the USS TERRY (DD513). She was building in Bath, Maine and the Bath Iron Works. It was just about ready. It was due to be ready in a couple of weeks at the time I reported. She was and I went up to Bath to join her as a prospective gunnery officer. Then we were commissioned down in Boston. We went down to Guantanamo for a shakedown and the usual things, gunnery practice and so on. We finished up and then went back to Boston for post shakedown overhaul and got whatever was done, done. Then we were ready to go join the Fleet.

An interesting sidelight to my time at Bath--I met a girl up there. There were a group of girls that we young officers thought attractive. They were sort of the elite of the city. They all worked as secretaries at the Bath Iron Works. I met her and her name was Barbara Pittman. I later married her. That was one of my achievements.

On the way back to join the Fleet, we would go out to the Pacific Fleet ultimately, we were assigned to escort an echelon of troop ships and supply ships to Casablanca. It was the second or third echelon for the North African invasion which had gone in through Casablanca. We were like the second or third echelon, I don't recall now. We made the run as anti-submarine escorts for a group of transports over to Casablanca. There we just turned around and went back to Norfolk to refuel and so forth and then headed out through the canal and up to San Diego.

Donald R. Lennon:

The escort was uneventful I take it.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, nothing happened. The invasion of Casablanca and North Africa had pushed

on quite a bit. They didn't run into real trouble until they got down around El Alamein and so on. That was sort of a hundred miles from Casablanca. The original fight at Casablanca was over. They reluctantly fought and sank the big French battleship, the JEAN BART in Casablanca because she was manned by the Vichy forces that were hostile to the U.S. at that time. They reluctantly had to beat up on her to insure that they got into the port. Then we went on out and by that time we were--of course there were all these little training things at each port we went into, like San Diego, then out to Pearl and we kicked around there for a few days. Then we were sent down as a relief squadron or a participating squadron back down to the Solomons. As I recall, we escorted some supply ships or troop ships, AP's or AK's, down on the way to Guadalcanal. That was kind of fun. That was my first crossing of the line as a Shellback.

When I went across in the ZANE, a year previously, I was a Pollywog. Incidentally, that's how I got my proper Marine/Navy haircut. One of the parts of the initiation on the ZANE was that just before they dumped you into a big thing of water, you went to the Royal Barber. He had great big clippers and he went right down the center of you head from front to back and just took it clean. In self-defense, so that I wouldn't look weird, I had the rest of my hair cut really short and I've worn it this way ever since. It's been the most comfortable decision I ever made in my life. In any event, this time that I went across, I was a Shellback and we had a big celebration in King Neptune's domain there. Then we went down and by this time, the battle for Guadalcanal was essentially over. I think there were still a few Japanese remnants still kicking around.

The battles for Vella LaVella was one of them and then Bougainville was yet to come. I don't think we were on the initial assault wave at Vella LaVella. We were just a

little late. We went on the second echelon. We went up there with a group of LSTs. That's the first time, incidentally, that we got into strange panics against enemy air where somebody reported, not by radar, buy by optical means, a lookout or something. One of our ships in our division, we were in a division and I guess the whole squadron was there, the look-out over the TBS (tactical radio), “Enemy dive bomber overhead, etc. Altitude high, etc.” Everybody got there and we swung her around. Several ships opened fire.

Fortunately, well not fortunately, it wouldn't have mattered if we had fired. I was looking through the scope. The radar operator was looking and we couldn't find it, we finally realized that it was Venus. We finally settled in on it and we all just quit firing. Venus was at about thirty degrees ahead of the sun. It was mid-morning and the sun was about over here Venus was just about overhead, directly overhead. We had a lot of fun about kidding each other about that.

At about this time, the DESRON 23, Arleigh Burke's squadron was rampaging up and down the slot having these fights off and on with these Japanese destroyer elements that were coming down occasionally. The Japanese were trying to do two things at one time at that time. They were trying to evacuate or re-supply or a little of both. Their contingents were on Vella LaVella and on Bougainville and so on. I don't know, I guess they were doing a little of each. They were trying to bring some troops in and then again, they couldn't. Then they thought they had better evacuate. In any event, they would send these destroyers down to guard the small transports that they took in. These landing craft convoys that they were trying to get off during the dark of night. The DESRON 23 and Areligh Burke people had been doing this for a while so we kind of relieved them of that duty. They went from there down to Australia on a joy wave.

Donald R. Lennon:

Whose command were you part of? Which admiral?

David M. Armstrong:

I'm trying to think of our squadron commander's name at that time. I cannot recall it or the squadron number. I can remember Areligh Burke, of course he was just a captain at that time. He was the squadron commander of DESRON 23. We didn't operate under the squadron commander nearly as much as the DESRON 23 did. We operated as divisions pretty much. One division went each night up the slot while the other stayed back to refuel, re-ammunition, get some sleep, and then the next noon time, that go up the slot and we'd be in. That's the way it worked for a month or so it seems to me.

We only had one really interesting time. The Japanese had these night black cat patrol boats that came out and did reconnaissance over us and we always had those guys around us all the time when we went up the slot. We were always on alert because we never knew when they would start making a run on us. They would hang out at about twenty thousand yards or ten miles off knowing that we couldn't reach them with anything that we had. So they would just mess around there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were they small PT-sized boats or something?

David M. Armstrong:

No. These were aircraft. I think they were mostly Bettys or big Kowanish seaplanes that were twin-engine things that would just lumber around. They were going about a hundred and fifty knots circling around and obviously reporting us continually. I don't think they had radar at that time but they could look down and see your wakes and that sort of stuff but they knew what you were doing. The only real excitement we had in all that time we had alerts and false alarms and those damned scout planes operating around us all the time. I think it was just approaching Vella LaVella or the next little island below it. I can't remember the name of it now. It still had some Japanese soldiers on it. They were having a

major move of soldiers from one small island to another one about five or ten miles away. We happened upon that thing. We turned and went into them, in amongst these barges. I couldn't count them, but there were as many as a hundred, probably more, landing craft. Some of them were even as small as native canoes. Some were big landing craft like our LCVP's and they were all moving and there was behind them and out of range from us, at least one destroyer, maybe two. We got right in amongst them and it was fierce.

Actually, these guys were too close to use the main battery when we got in amongst them, the five-inch 38s, for any really good destructive work. Things were changing too fast and we couldn't. We had the main battery lobs star shells high, this was on order from division commander, it wasn't my idea. We lobbed star shells along with somebody else. We lobbed them to port and the other lobbed them starboard and that lit up. We fired them high at short range, they would burst, and the star shells would start drifting down. They silhouetted all these boats that we were in among. Then we used the forty millimeters and the twenty millimeters to do the damage. I can recall one LCVP size boats that got up close to us. It was clogged with Japanese soldiers. One of our forty-millimeter quad mounts turned down on it and finally sank it. They were all around us; it was just a question of which one you wanted to shoot at. He hit the bow. It was at a down angle like this, the thing was so close. They were up on the first deck level so they must have been fifty yards away. They just knocked the bow down with a quad forty. The stern came up and dumped all those soldiers out and they were screaming and yelling. This is what we were doing. We were right in the middle and just spraying.

Donald R. Lennon:

It was like a turkey shoot.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, we were just spraying twenty millimeter and forty millimeter as fast as we

could mow them. It was just amazing. Then we did about all the damage that we could do. I think we shot up most of those things.

Donald R. Lennon:

The destroyers didn't try to come to their rescue?

David M. Armstrong:

Well, they did. At least on radar, we thought they were coming towards us.

Donald R. Lennon:

It looks like they would have rushed right in to try to divert you at least.

David M. Armstrong:

There is some discussion now. It was never decided whether those were actually destroyers or whether they were just larger AP's transfer types. We could see them on radar. We couldn't see them visually. As I remember, we fired a couple of torpedoes over there at them because they weren't moving fast. There was no result.

Donald R. Lennon:

You didn't receive any fire from them?

David M. Armstrong:

No, no. At least not that we could tell. By that time, our time up there was running loose. Then there was a report from the coast watchers that somebody was coming down from the other end. They may have summoned somebody down from Rabaul or Bougainville when they realized what was going on. I'm not sure those were destroyers. That's why the question was pertinent and I don't think they attacked. It turned out--we were using five-inch thirty eights by then, firing them over in that direction and so forth. I had a hang fire, a miss fire, on one of the guns. At that point, we were supposed to cease firing and everything as supposed to be quiet. We were going to retreat down the slot again because apparently at the other end was coming in so we did not fire it out.

What we should have done in hindsight possibly would have been to immediately put in another cartridge and try to fire it and try and fire the thing out. But we didn't. What we did was put the hose down the barrel with cold seawater to try to keep the thing from cooking off. But it did. It cooked off and went "bam" in the barrel. It didn't hurt anybody

but it ruined the gun barrel. We had to go down to Espiritu Po. There was a destroyer tender in there by then. They put in a new liner. It seems to me that about that time, I was detached to go back.

Donald R. Lennon:

You all pretty much wiped out that contingent of troops that they were moving didn't you?

David M. Armstrong:

We think so. In one point, I don't know whether it was before or after the night we did so much damage, we had a trip down to Sidney, Australia for a week. The other ships in the squadron went ahead of us by about one day and we were held up because we were experimenting for the Bureau of Ships with somebody else, another ship not in our squadron, using infrared signal lights at night. We were testing those. I guess it was because our skipper, Squidge Lee. was the junior one in our squadron. So we were delayed a day. We sailed down alone to Sydney. By that time, the Americans in Sydney had it set up beautifully. You came in and they sent a boarding officer over and gave you everything you needed to get whiskey rations, numbers to call for places to rent a house for the time. I forget all what else.

Anyway, four of us from the TERRY (I had fleeted up to exec by then) rented a house in the suburbs of Sydney. We were going to be there a week. We bought our liquor rations and we rented a car. They even had people renting cars down on the piers for us. We went by and bought our whisky ration, took our car, and went to this house. It was like a four room house. Everybody had a bedroom. Man, what a time we had down there. It was really glorious. We went out and met girls and we would always bring them back to the house and serve them good whiskey and things like that. That was a wonderful time, a really relaxing time.

One of the things that happened just, as a little sidelight, one of the first evenings ashore, we went into a raw bar where they serve Australian beer and oysters. It was typical. That was great. It was early in our stay there, I think may be even our first night. We got to drinking Australian beer and eating oysters and they had a sing-a-long piano player there. He was playing stuff like “Waltzing Matilda” and he was singing into his microphone. As I remember, they had a little screen where they would put the words up. The four of us had played around on the ship sometimes and we had sung a little quartet. We would sing “I Had a Dream Dear” and “By the Old Mill Steam” and stuff like that. They got to doing those kind of things and the four of us were there singing in our little quartet style. Pretty soon we noticed the tables nest to us had quit singing. They were listening. This went on for maybe one song or something and finally the piano said, “How about you gentlemen from the U.S. Navy come on down here and sing a song for us.” So we went down to his microphone and huddled around his piano and sang, I think, “You Can Throw a Silver Dollar Down Upon the Ground,” they rolled. Then we sang one more that I don't remember. We got great applause and the management offered us free beer for the rest of the night. That was my one time of singing professionally. That was kind of fun.

Then we went back up to the Guadalcanal area just in time (I think this chronology is right--I wouldn't swear to it) to do the invasion of Bougainville at Cape Torokina. We went up there to do the deal. We had actually the commander of the Marine regiment that landed there. It was just a regimental landing as I recall. We were the flagship for the commander of the landing force and we shot up a lot of ammunition and stuff and put the Marines ashore.

Donald R. Lennon:

You don't remember who the Marine leader was?

David M. Armstrong:

I surely don't. I think he was either a colonel or a brigadier general. I surely don't remember his name. Anyway, we did that. Then the most exciting thing that we did was before we left the Solomons. The central Pacific operations, the Marshall Island operation, had already gone on as I remember. They were planning the Mariana's operation. We were scheduled to go up and join up with the Fifth Fleet for the Mariana's operation. Just before we left, and I really got a kick out of that, our squadron went up and bombarded Rabaul for most of the night. Rabaul was the main base and everything. It had already been attacked and beat up pretty badly by the carriers on a couple of occasions. We went up there and lobbed rounds for about three hours. We must have expended a thousand rounds a piece right over those hills and down into the harbor.

Donald R. Lennon:

You weren't getting any resistance at all from the Japanese?

David M. Armstrong:

No, not a thing. Of course, we had always been intimidated by Rabaul. That was their big base. I had, by now, two tours in the Solomons. The mere mention of the word Rabaul, why boy, you would begin to say “Wahoo!” Anyway, we met with no resistance at all and we beat it out of there and got back within our air support areas by dawn. We didn't even have any air opposition. There was no one following us in the air. We tried to hit the airstrip and so on to keep them down. I really got a kick out of that. I had worried about Rabaul and what was going on there for two years.

Then we went up to the central Pacific. We were in on the operation that started out in Saipan, then Guam, and then Tinian. We were there for all three of those. We had some interesting times. George Phelan, who at twenty-four, was our first commanding officer in the TERRY had been relieved by Squidge Lee. I think I mentioned that. Squidge Lee was now the skipper.

I was, by this time fleeted up to exec. I can't remember if I was exec under George or not. We got in on the invasions and we had some interesting things happen over there. In Saipan, we were part of the bombardment group that was getting call fire for the Marine and Army units ashore. One time we were sitting in the middle of the afternoon with no fire missions at the moment, just looking over the terrain with binoculars. The gun director was always pointed that way. It was looking up and down. There was a roadway that went from Garapan, I think was the city, up to the northern end of the island.

Donald R. Lennon:

How close in were you to the island?

David M. Armstrong:

I don't know, a couple of thousand yards. We were within a mile or so. We could see perfectly well over there. We saw a group of tanks, we assumed/knew right away that they were Japanese because we knew where our front lines were. They were back down by Garapan. We were up several miles beyond that. We saw those tanks scooting up that road. There were four or five of them. Boy what a target of opportunity. We just let loose with everything we had. I don't know if we hit any of them or not. But we came near enough that they just dispersed and then it wasn't worthwhile for us to fire on them any more.

There was another interesting things while we were down in Guam. In the Guam invasion, we would have one day off and one day on giving fire support. We would be firing for twenty-four hours. At night we were fire interdiction fires and harassment fires. We would just lob them over there randomly all night long in Japanese areas to keep them down and not let them get any sleep. We spent twenty-four hours in close by Orote Peninsula. The next day we would go out so that everybody could get a little sleep. We would either refuel or reammunition or replenish whatever we needed. Then the next day we would go back in. We did like that for about a period of a week. We were supporting--I

have forgotten now which Marine battalion it was. Each Marine battalion had a fire support/control officer of a Navy type and a Marine type that did the call fires to the ships. They would call out the ships and designate the targets and tell you where and when. They would spot for you and the whole thing.

We established quite a rapport with this particular battalion. We had been supporting them all the way. Their job was to go to the back of the Orote Peninsula. In the back of the Orote Peninsula was a big mountain. The Japanese were up there in considerable strength. That's where they kind of filtered too. Their job was to go up that mountain and beat up the Japanese. The Japanese weren't giving up. As you know, we didn't find some of them until 1950 or something out there in Guam.

Anyway, we got to know these guys and so we invited them, whenever they could, one at a time, to come out to the ship. They would come out in a boat and join the ship and watch us fire. We would give them a shower and ice cream and a mob of cigarettes and cigars and candy bars to take back. They would sleep overnight with us and we would feed them a meal and so forth. We got to be pretty friendly with them. It turned out that that was one of the things that led us to the deal where, when they got to tough going there were caves that the Japanese had dug or maybe they were natural and they had improved them or something. up near the too. This was the big thing, to get to them. Our spotters and our fire control officers from the Marine battalion would talk to us like this: They would say, "Hey now look, we are at such and such a place and if you look through your range finder, you'll see a big rock there. It's shaped like a “U.”

We would say, “Okay, we got it.”

Then they would say, “Now, were just below that. Just up and to the right about a

hundred yards from that big rock is a cave. I don't think you can see it from where you are, but if you can, that's where we want you to shoot at.” We were doing all this talking it out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Lobbing the shells?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes. We would shoot where they said they wanted us to, not by the grid thing you know and so forth. They would describe to us as soon as we got fixed in to the landmark, then we would deviate from that and find whatever it was they wanted us to shoot at. That was great because on a fire control grid map, that mountain was just a bunch of circles and the grid didn't mean much when you were trying to actually hit something, which we had to hit those damned cave entrances. We spent several days using that system as they went up there. They finally took those mountains and that was an interesting thing. It was all done by our just saying, “Hey, when you get the chance, come on out to the ship.” They would stay with us for a day, three or four different ones in a party. As I said, we would load them up with ice cream, candy bars, and cigarettes, and cigars to take back. That was interesting. We were in on the battle of the Philippine Sea, the so-called “Turkey Shoot.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Down in Guam and Tinian, was there any Japanese resistance to your firing? Or were they just concerned with defending themselves against the land forces?

David M. Armstrong:

No, no we got no counter-battery at all. Yes, right. We never got any counter-battery and I don't think any of the ships did.

Donald R. Lennon:

They had no planes left in that area?

David M. Armstrong:

They had none. They had the airfield on Rota and so forth and that had been wiped out. Before the battle of the Philippine Sea and when their carriers set off the first attack groups, they were supposed to land at Rota because they couldn't make it back to the ships. When they got there, they found that it was ours. Of course, we met them halfway.

Donald R. Lennon:

So you felt relatively safe out there without a Japanese fleet or squadron close by.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, we weren't worried about it at all. We were just enjoying ourselves. The only thing was that the noise kept us all night because we were shooting all night. As the gunnery officer, I would go for twenty-four hours without any sleep. I would have to sleep the next day. I guess I was exec by then. That was another thing that Squidge Lee and I did--he was the skipper and I was exec. We would be firing all night, so I would take his position on the bridge and conduct the firing for half the night and he would relieve me and I would sleep in his sea cabin when I was off. You couldn't get any sleep on a destroyer with those five-inch thirty-eights going off, one every thirty seconds or one every ten seconds. We worked out that little deal to where we split the night watches. I would maneuver the ship as necessary and give the firing commands when they were necessary. Always, the gunnery officer on watch would call to the bridge and say, “I am on target as required. Request permission to open fire.” They would say, “yes.” Of course they would look to see whether they were pointed right and all that. Squidge and I split that duty. That was a help to both of us. After about a week of it we were so tired we couldn't hardly think. Then when we were off, it was nice for a lot of the crew, but for us, running the ship and conning alongside for replenishment and so forth.

The thing I remember about the battle of the Philippine Sea was when our people who had been sent out on that strait and come back at night. Admiral Mitscher said, “Turn on the lights.” We all turned on the searchlights and turned them right straight up in the sky so that the guys coming back could see the Fleet. They were just about out of gas. They were landing on the wrong ships and everything but nobody minded that. The whole idea was to get them down and on the carriers. We were plane guarding a couple of carriers and

Squidge decided, I don't know why, that he would take the watch out on the wing of the bridge. He was to spot for us if he saw planes going down or anything like that. I would con. In plane guard position, you get up about three hundred yards behind the carrier and hold it. You are kind of a landmark for planes coming in. They fly right over you and also, you are right ready to pick them up of they fall into the water. I was conning the ship, flashing along, going twenty-five or twenty-eight knots or something. About then, planes started going in near us, so we deviated, with permission. The task force granted us permission to go rescue the pilots. Squidge would stay out on the wing and I would con the ship. I would con the ship up and he would tell me where he wanted me to go and I would back her down. We fished up three or four aviators that night. One of them was a guy named Kane. He had been wounded previously. I don't know if it was in aerial combat or on a ground attack run. He had his head all bandaged. We fished him out of the water. He was the air group commander on one of the carriers. We said, "What in the hell, you already have been bandaged up. What in the world can we do for you?" He was in the water and we fished him out and he had been wounded before, but he was up there, boy. His air group was up there and he wasn't about to let them go without him.

Donald R. Lennon:

The reason they were in the water was primarily because they were out of gas?

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, they were out of gas. They just couldn't quite make it to the carrier. Some of them went in outside of the screen. That's where we went. A couple of them almost made it, being only a couple of miles short. We fished out three or four. That was a worthwhile thing to do. I was so proud of being at the con. Squidge would say, “He's right over there, he about a point on the port bow.” Then I would head for him. We would get out there and we would look and I would stop the engines and back down and do all that.

Donald R. Lennon:

Trying to spot an individual in the water in the middle of the night out there wasn't the easy was it?

David M. Armstrong:

No, but their life jackets normally have a little flashlight on it. Sometimes they have lights and we could see the plane. The planes, as I remember it, had lights. They put their landing lights on when they came in and we could see a plane with landing lights splash in and we would go there.

Donald R. Lennon:

The sea was pretty calm too.

David M. Armstrong:

Yes, it wasn't bad at all. We were able to find them once they went in. I don't know that we were able to find them at all. I don't think so. I think a number of them didn't quite make it back. We went out and searched for them the next day. That was one of the better things I was involved in during the war. We really made a contribution, particularly picking up that brave air group commander that wasn't about to let his group go out and fight the Japanese fleet without him. He was all bandaged up.

We got orders in the TERRY to go back, this is when we had wrapped up the Mariana's operation, to the Naval shipyard as I recall in San Francisco for an overhaul. An interesting thing was that I got to know real well and loved George Phelan, who had been our original skipper in the TERRY. As a matter of fact, he convinced me to go to Naval intelligence school. He had been in Naval intelligence before the war. He was a roughed up old guy, thin as a rail. He had a moustache. Up on the bridge, whenever anything got tense, George would twitch has moustache and scratch his ass, I knew he was worried. I can remember with the carrier task force, just before George left us, that it was a quiet afternoon. There were no flight operations. They had gone off. We were just cruising along. I had the afternoon or the morning watch. We had some awfully good JOs to come

along. I'll name Jim Mason out of the Naval Academy. He was a crackerjack. His words would come out on the bridge from the voice tube. That is when I was still gunnery officer. He would say, “Guns, who's your JP?” I would say, “Mason, sir.” He would say, “All right, turn it over to him and come in to the sea cabin.” I would go in there and he would be ready to play Russian bank. We would sit there and play cards. I don't remember how many times I would get that call to go in and sit with the skipper and play Russian bank. We would sit there and play cards. It was ten feet from the bridge so it was no great deal. We became quite good friends because of that. I did some things on line handling for him that he thought were fine. I remember one time when we were out in the screen for a fast carrier task force somewhere some place and we were roaring along. They ran up the FOX flag and that meant for people to take their positions for launching or landing, whichever it was. Our position was plain guard for one of the three carriers. I had worked out where to go on the maneuvering board, I had taken the direct course to it. The way I was going, I was just going to come in right behind the carrier and pull up in position. Of course I notified George. He was in taking a nap. the son-of-a-gun had worked so hard and he was up most of the nights and the whole thing. We let him sleep whenever we could. I hollered in, “Captain, they've hoisted fox. I'm going to plane guard station.” He said, “Very well.” In a couple of minutes, he came wondering out on the bridge. He looks and here's the way I was going, I was headed right here and the carrier was right here. I was going, it looked to him, on a collision course. I knew it wasn't. I knew that my speed differential would enable me to come right in behind him. I had it figured and I was taking bearing all the way. He said, “All engines stop.” I said, “My God, Captain, please don't do that. You will mess us up. Belay that. Hold what you got.” They looked and looked, and he said, “Yea, that's all right.

That's all right. You're all right.” then he went over by his chair and sat there twiddling his moustache and he stretched his feet up. He was long lanky thin guy. He sat there mumbling, “that little son-of-a-bitch telling me what to do on my own bridge. . . I can't have that god-damned thing on my bridge.... my very own bridge. . . I can't have that son-of-a-bitch telling me what to do. . .” That's the way he worked off his anger. We were friends from then on. I gave you that background because it was so interesting. When we came back in the TERRY, George had gone off to be division commander of a division of destroyers, I don't know which division or anything. He heard or knew from the fox schedules and so on that the TERRY was scheduled to go back. He had requested and been assigned to the TERRY for transportation to San Francisco. He came aboard his old ship as a passenger. I got orders on the way back, they of course knew we were coming back, that I was to be detached on arrival, thirty days leave, and then new construction. George and I were detached from the ship when we arrived in San Francisco. George said to me, “Guns, let's get us a hotel room together, it would be cheaper.” I said, “Okay, that's fine, Captain.” We got a room at the St. Francis I guess it was. We had about four days to wait. We had to send a message saying that were here. BUPERS had to do all their stuff. Then we got the message back through the district personnel officer and whole process lasted about four or five days. George and I shared the room. George had in his bag, a bottle of old Tennessee bourbon. He said, “I've carried it for a long, long time. I think you and I had better have some of this.” He opened his bottle of old Tennessee bourbon. We sat there, had drinks, and told sea stories. George had a wife, I knew her before she passed away. She was a wonderful lady. She died just after the war as I recall. He said, “Now Guns, don't stay in here because of me, you get on out on the town. If you want to bring a guest up here, all

you have to do is call from the lobby and tell me you're bringing up a guest. I'll get right out of here and out of your way.” He was being so considerate. That time of telling sea stories with him and enjoying his companionship and being roommates with him was just delightful. I really got to love the guy.

Donald R. Lennon:

You were nicknamed Guns. Was that because you were the gunnery officer?

David M. Armstrong:

It was because I was gunnery officer under him. He called me Guns. I really enjoyed that. That was a charming incident. We got along famously. Then we separated and went on. Once again, my orders were to the HIGBEE under construction at the Bath Iron Works at Bath, Maine. I went back and spent my leave in Washington. Then from Washington, I had to go to Norfolk and take the pre-commissioning crew. That was it. I had to train them and then we went up to get the ship a couple of months later.