Interview of Jack Kiser

| Interviewee: | Jack Kiser |

| Interviewer: | Michelle A. Francis |

| Date of Interview: | August 6, 1983 |

Jack Kiser:

I think the first thing I did was buy a truck for hauling.

Michelle A. Francis:

Had you saved some money when you were in China?

Jack Kiser:

Gosh, no! You don't save money in China. I'd come back to the States one trip and never went ashore, saving my money when I got back to Shanghai.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really?

Jack Kiser:

There were a lot of English people. I say a lot, I knew a half a dozen men. The [unintelligible] were big people. They called them "remittance men". The [unintelligible] hired 'em to go to Shanghai, to China and live, not in, to disgrace from that. And they'd get their check every month. They called them remittance men. We could find them, I know two or three I'd always be around by the time they got their check and they'd buy a lot of drinks in the bar when they got their checks. But there were a lot of them out there. Called them remittance men. [unintelligible] And that's the cheapest place you could live.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, you said you were in China from 1922?

Jack Kiser:

No, I didn't join the Navy until '25. I was in China in '26, '7, '8 and probably '9.

Michelle A. Francis:

'29. And when you got back to this country, you were right in the middle of the Depression.

Jack Kiser:

Got back in '29, things was boomin'. The stock market busted in '29 and '30, '31, '2, the places--yeah, I've worked here for less money than I got in the Navy.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were you doin' when you came back?

Jack Kiser:

Oh, like I said, I bought a truck to start with. I's gonna get rich truckin'. Well, I must of eat, but that's about all.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did you start doin' pottery?

Jack Kiser:

Oh, it must of been about February, '1 and '2.

Michelle A. Francis:

You were tellin' Dorothy and I that, who was the man you were workin' for?

Jack Kiser:

Walter Lineberry.

Michelle A. Francis:

Walter Lineberry, yeah. He had, um, was that North State?

Jack Kiser:

No. He never had any more pottery there. He worked the potters out of time. He'd just with Jase Cole in there and, he was an old bachelor that'd saved his money and he decided he'd build him a pottery and him and uh, Bascome King, they built the kiln. Got a wheel and built a--and I went to turnin'. [unintelligible] I went to turnin'. I don't know, made salt glaze, all they made there durin' my own time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it a wood-fired kiln?

Jack Kiser:

Well, at that time they were all. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Jack Kiser:

'Cause I had a truck, I hauled a lot of wood up there at the Cole's place.

Michelle A. Francis:

Up to Cole's?

Jack Kiser:

Mm-hum. Well, everybody in the country hauled it up there to use, cords and cords a day.

Michelle A. Francis:

I guess haulin' wood wasn't too bad an occupation. Hard work but, with all the potteries around here, you sure had. . .

Jack Kiser:

Didn't pay anything.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .didn't pay anything?

Jack Kiser:

Well, the wood only costs $3. That's what the potteries paid. That was the standard price, $3 a cord.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my.

Jack Kiser:

I'd have it cut and hauled and sold. You could take a truck and maybe make $10-$12 a day, workin' 14 hours.

Michelle A. Francis:

It's hard work.

Jack Kiser:

It's hard.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did Mr. Lineberry have a name for his pottery?

Jack Kiser:

Huh-uh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he ask you to come work for him?

Jack Kiser:

Mm-hum. Well, I knew him and seemed like I, I don't remember how I met him or what. He just started out like he thought I's gonna be his turner. I never seen any turnin'. And he worked around enough that he could show you how, but he couldn't turn.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Jack Kiser:

Well, I managed to make a few pieces.

Michelle A. Francis:

He showed you how to do it and you just did it?

Jack Kiser:

And then I got to lookin' around, seein' you know, got interested and I'd go to other potters. Gosh at the hundreds of thousands of gallons of stoneware I've turned, besides all that other stuff.

Michelle A. Francis:

You never thought anything about it either, did ya? Today people would just love to have somethin' that you did.

Jack Kiser:

I don't know why we didn't date the stuff back then.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. I guess you just didn't see, didn't have any way to know that it was gonna be valuable. Somebody would want to collect it.

Jack Kiser:

Some of those old potters like Davis [note], you know him over there on the plank road, some of them, Craven, or something?

Michelle A. Francis:

I don't know.

Jack Kiser:

I think [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they date their stuff?

Jack Kiser:

It's worth a whole lot you see.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Jack Kiser:

But it wasn't worth anything. Salt glaze was only 12, 15 cents a gallon.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did Mr. Lineberry ever do any Albany slip?

Jack Kiser:

Nothin' but salt glaze.

Michelle A. Francis:

Nothin' but salt glaze.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he ever decorate any of it, with cobalt?

Jack Kiser:

No, straight salt glaze. Churns. Pitchers, milk crock sort of thing.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Well, you made some pretty pieces. I like your handles, the way you made handles. How long'd you stay with Mr. Lineberry?

Jack Kiser:

Not too long. When I got to be a turner, somebody else offered me a lot more than I could make there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they? Who did you go with next? After him who did you work with?

Jack Kiser:

Jase Cole.

Michelle A. Francis:

Jase Cole?

Jack Kiser:

And from there to another salt glaze place, and then to Smithfield, to another Cole, and then to Sanford for a Cole.

Michelle A. Francis:

That was A.R. Cole in Sanford, wasn't it? Arthur?

Jack Kiser:

Arthur.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was it in Smithfield?

Jack Kiser:

It was a Cole, too. Uh, I used to know the man over there like, my mind's goin' and I cain't think of his name. Jase, I mean, the old man, the brother of the one's turnip' up there now.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon's?

Jack Kiser:

His brother.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was Waymon turnin' when you worked for Jase?

Jack Kiser:

Uh, Bascome King, me, Philmore, Nell, and him. That'd be five then.

Michelle A. Francis:

Waymon? Sure would. You must a'been turnin' out a lot of pottery.

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. Ours was the biggest pottery around here in them days. I took solid truck loads of it up North.

Michelle A. Francis:

Would this have been what, about 1930?

Jack Kiser:

I imagine it was in the '30s. Naw, it would have to a'been in the '30s.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where would they haul it to?

Jack Kiser:

New York. I remember Macy's in New York bought a solid load of those old--I forgot the name of it. Oh, shoot.

Michelle A. Francis:

Those garden urns?

Jack Kiser:

Huh?

Michelle A. Francis:

Were they garden urns?

Jack Kiser:

Yeah, they were about 20 inches tall.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were they some that you made?

Jack Kiser:

No, I believe Waymon turned most of them. I might a'turned some. I don't remember. There was truck loads of 'em, I know it. Think now how cheap they were, oh, tall as about like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. About 22 inches high?

Jack Kiser:

I believe he sold 'em for about, well, $2 would be the top. Seemed like it was $1.75.

Michelle A. Francis:

Isn't that somethin'? What color were they?

Jack Kiser:

All colors.

Michelle A. Francis:

All colors. Was he, I guess he was still usin' a wood furnace then, wasn't he? Wood kiln.

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. He used wood up till after the war.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did they have to put 'em in saggers?

Jack Kiser:

No. I don't reckon they ever used a sagger. If he uses 'em now.

Michelle A. Francis:

He doesn't now.

Jack Kiser:

As far as I know--Herman--that's the Cole down in Smithfield. He was the first man that ever started usin' saggers.

Michelle A. Francis:

Really.

Jack Kiser:

And, uh, I must a'went back to Jase's after that time because I made some saggers for old man Jase, and made uh, I made him a mold and he made some big jars. I made those out of the stuff you make saggers out of.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. You put a lot of sawdust in those saggers, don't ya?

Jack Kiser:

Hum-uh.

Michelle A. Francis:

No?

Jack Kiser:

They grind up old broken pottery and about half of that mixed with the clay. Now, that's the way he did it. Maybe some people use sawdust.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you getting paid by the piece?

Jack Kiser:

Hm?

Michelle A. Francis:

When you were turning for Jase Cole, did they pay you by the piece?

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. All potters paid by the piece.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were you getting paid back then?

Jack Kiser:

You mean how much did I make a week?

Michelle A. Francis:

Or how much, yeah, or how much did you make per piece?

Jack Kiser:

Well, it was according to the size. Anywhere from 10 cents up to 50 cents a piece; or 5 cents mostly.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you like making pottery better than hauling wood?

Jack Kiser:

Oh shoot, I was glad to turn pottery. It was hard work makin' big pots, and that's about all I ever made.

Michelle A. Francis:

Took a lot of strength to center that big ball of clay.

Jack Kiser:

Well, [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Jack Kiser:

Salt glaze, makin' churns and jars, it is hard work, usin' about 25 or 35 pound balls.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Waymon was sayin' that sometimes he would use up to 60 pounds. Now that would be an awful big piece of pottery.

Jack Kiser:

Must a'been two pieces. Did he say two pieces, or just one?

Michelle A. Francis:

He didn't say. He just said he would center it.

Jack Kiser:

Yeah, we made some real tall ones--make 'em in three pieces. Turn the top, set it off, and the middle, set it off, and come up [unintelligible]. That piece that was in my photographs I give you was Thelma Graves standin' beside of it. I saw that made down at Herman Cole's--Charlie Craven, he was turnin' big stuff. And I come back to Jase's and made that big piece, one. And I think that was made in three pieces.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it? Who did you see turnin' it at Herman's?

Jack Kiser:

Charlie Craven.

Michelle A. Francis:

Charlie Craven. He's in Raleigh now. He's still turnin'.

Jack Kiser:

He is?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. He takes his pots out to Jug town and they fire 'em for him. And he's still turnin'.

Jack Kiser:

Him and his boy stopped by when I was down at the store around here. And that's the one time I've seen him, one time since he quit over at Merry Oaks [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Did you work at Merry Oaks after you worked at Jase Cole's?

Jack Kiser:

Oh yeah! I built Merry Oaks.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you?

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. See, I was turnin' at Arthur's and this fella come by and just stopped to spend the time. He went on to Florida or Cuba, I forget where. And he come back up and another year down, and then he come back and he had the fever, excited [unintelligible]. So he looked around and bought a few acres up there at Merry Oaks, [unintelligible] and the highway. And, I said, "I'll build him a good one." Got this [unintelligible] contractor to build the building, and I built the kiln. He took me up to Pennsylvania to look at those oil-fired kilns. I reckon I built the first oil- fired type of kiln in North Carolina.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did ya? That must have been in the early 1940s then.

Jack Kiser:

Oh, it was before the war. Had to be, because the government froze the [unintelligible] after the war started.

Michelle A. Francis:

'Cause they needed the oil, didn't they?

Jack Kiser:

Well, I reckon the oil and then, they told 'em they could stop makin' some chemical stoneware, or somethin' like that, but [unintelligible]. They kept piles of this chemicals and stuff. [unintelligible] Cobalt, you could buy a pound or two but it's probably out of a barrel. [unintelligible] the money.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Jack Kiser:

. He was, they called a millionaire back then. A millionaire then would be same as a man worth 20 million now.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's right. Well, they shut you down when the war started, in what, '41 or '42?

Jack Kiser:

Well, I don't know. I went to the shipyards then.

Michelle A. Francis:

You did?

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. When I was out of there, they had a welding school down at State College and I went there. Thought I was a welder, but I'm not good at welding. Then I worked other places. Grafton, West Virginia, Marston [note] Chemical Stoneware. [unintelligible] Akron, Ohio. Place or two on the river. You know, work a week and move.

Michelle A. Francis:

You just were a travelin' man at heart, weren't ya?

Jack Kiser:

I think we had some nice buildin's over there. One of 'em was not too bad. We had furniture built. I think Waymon bought the furniture, it must be [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Did he? The one from Merry Oaks?

Jack Kiser:

Uh, somebody told me he did that.

Michelle A. Francis:

What'd you do after the war?

Jack Kiser:

Immediately after, in Wilmington, I think I ran a pool room and a beer joint.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you (Laughter).

Jack Kiser:

Finally got back up here. After 20 years ran a store and a service station.

Michelle A. Francis:

So you never turned any more after the war?

Jack Kiser:

That's where I was crazy. If I'd a known pottery that would get up to payin' more than 25 cents a piece, I'd a'tried to kept my little pottery.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. That's a hard way to make a livin'. Even the people that do it today, it's a lot of work. Although I talk to people, like Waymon and Dorothy Auman, and they wouldn't do anything else.

Jack Kiser:

Her father, he, he was a potter before them, his father was a potter [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you ever work for Charlie Cole?

Jack Kiser:

No. No, I've stopped by there and turned a piece or two as J.B. Showed 'em how to make a big piece. No, I never worked.

Michelle A. Francis:

When you were workin' for Jase Cole, you were just turnin' the big churns?

Jack Kiser:

No, he wasn't makin' churns.

Michelle A. Francis:

I mean, not Charlie, for Jase.

Jack Kiser:

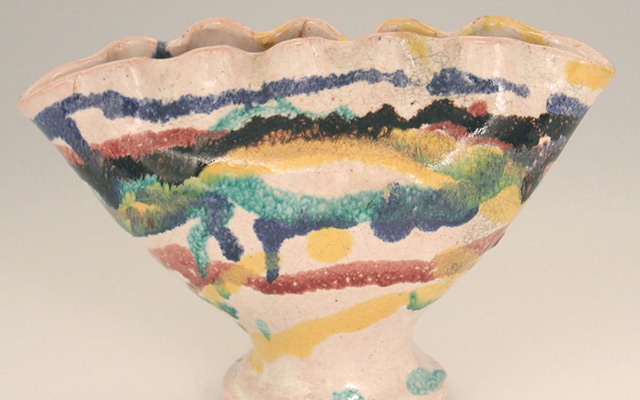

I say, Jase never made any churns. No stoneware. It's always colored, decorative ware, is all he's makin' when I was there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, when you were there, he was just doin' the glazed pottery.

Jack Kiser:

That's right, the glazed pottery. Looks like to me somebody would go in the salt glaze business, had the clay to make it salt glaze, the way you talk like it sells, that they could make more money in salt glaze than they could in this other. Nothin' to buy but a bag of salt.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Well, some of the potteries are startin' to make salt glaze again. Melvin Owens is makin' it.

Jack Kiser:

He burns oil?

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Jack Kiser:

Some lady, she must not know nothing, said you couldn't make salt glaze with anything but wood.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, it's not true.

Jack Kiser:

Not true. [unintelligible]. There're two fires to this kind of [unintelligible]. One of 'em was oxidizin' and the other was reducin'. A reducin'--anyway, she was tryin' to tell me, you know the salt glaze, always the last they throw in that light wood and the flames comin' out and the smoke, that's what made the best salt glaze. I forget if she said that was the reducin' or the oxidizin' flame.

Michelle A. Francis:

She must not a'known a whole lot, or not as much as she thought she knew.

Jack Kiser:

Well, back when she was talkin', there'd never been any fired with oil, I don't suppose.

Michelle A. Francis:

No?

Jack Kiser:

In an oil kiln, no.

Michelle A. Francis:

People tell me some of the glazes that you got from firin' in a wood kiln, you know, the glazed pottery, was really pretty. I didn't realize till recently that you could do glazes in a wood-firing kiln.

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. That's all Jase Cole used. He had about four, five kilns. Burnt one every other day, they had one they burnt every day, I believe. Yeah. He didn't know anything else. In this whole country, the only oil was [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. What was Philmore turnin' when you were workin' at Jase's?

Jack Kiser:

Got to have a different shape to turn every day, maybe, 'til the orders come in. Early in the mornin', turn that stuff.

Michelle A. Francis:

Would he tell you stories while he was turnin'?

Jack Kiser:

No, he didn't tell me the big tales, 'cause he knew I knew better. I listened to him tell it to the others. No, he didn't tell me any tales. I knew him. We went squirrel huntin' one time and he had a pistol and we both had shotguns, and saw a squirrel up there on a limb and I said, "Don't shoot it. Let me have your pistol and I'll shoot' him." We was just talkin'. I don't think I aimed or even looked at the thing. I shot it and killed it dead. You should a'heard the tales that he told people what a crack shot I was. (Laughter) I couldn't a'hit that squirrel if I'd a'shot till I got to be an old man again. It just happened. But, people have asked me, weeks later, "I hear you're one of the best shots ever." I said, "Well, I reckon I'm pretty good.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) Well, he told everything in good fun, didn't he?

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. He told some of the awfulest tales and lies that's ever been, but I've never known him to tell anything that hurt anybody in any way. Tell those Yankees big tales. They didn't know whether it was true or not. Yeah, I'll never forget that time he was tellin' about, he kept a gang of Plott hounds back up, a man kept 'em for him in Tennessee, and he went bear huntin' two, three times a year. He says, "You know, I get the biggest thrill out of life crawlin' in a cave with a flashlight in one hand and a .45 automatic in the other." Goin' in the cave after a bear.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) And people probably believed him.

Jack Kiser:

Yeah. They, there was two bear hunters from up North a'talkin' to him. I imagine they agreed he'd get quite a thrill out of that. A lady asked him, "Mr. Graves, are you originally from this town?" "Oh no, I'm from New Jersey. I was a southern manager for Standard Oil Company. And I came by one time and saw the sign, 'Stop and see it made', so I stopped and watched 'em turn and it fascinated me so I asked Mr. Cole if he'd learn me to turn. I went back up North and quit my job to come back and go to work."

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) He could tell a good one.

Jack Kiser:

But he never hurt anybody.

Michelle A. Francis:

No. That's what I hear. It was unusual to have a woman turning, wasn't it, back then? For Nell to be turning?

Jack Kiser:

Well, that's the only one I remember turnin' then. 'Course now-a-days, you know, there's Virginia King that lives over here. She works at the [unintelligible]. That was Bascome King's daughter. He was turnin' with me. He started turnin' 'bout when I did, I reckon. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

I sure do.

Jack Kiser:

I used to live in Raleigh.

Michelle A. Francis:

You've lived just about everywhere! Where were you born?

Jack Kiser:

Winston-Salem.

Michelle A. Francis:

In Winston-Salem?

Jack Kiser:

Mm-hum. My father worked for the Southern Railroad so they transferred him to Raleigh and from Raleigh to Richmond.

Michelle A. Francis:

To Richmond. How long did you live in Raleigh?

Jack Kiser:

Not long. I'd say a year.

Michelle A. Francis:

And Richmond?

Jack Kiser:

Oh, I lived up there from the time I was 8 years old until I was about 13.

Michelle A. Francis:

Thirteen? When were you born, Mr. Kiser?

Jack Kiser:

1908.

Michelle A. Francis:

1908.

Jack Kiser:

That's what I had put on the tombstone. I was born in 1900.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) You're not gonna tell me which one?

Jack Kiser:

Huh?

Michelle A. Francis:

You're not gonna tell me which is the truth?

Jack Kiser:

Hm-um. Oh, we was talkin' about somebody the other day, how sorry the mail service was. They've got to do it, the lady Thursday afternoon, I cain't hardly see, she wrote checks for the [unintelligible]. She mailed it oh, I'll say 6 o'clock Thursday afternoon up to real [unintelligible]. So one full day. This mornin' at 9 o'clock the mail brought me a receipt [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

That's pretty good.

Jack Kiser:

I don't see how they did it.

Michelle A. Francis:

You can't complain about that.

Jack Kiser:

One day. 'Course a couple of nights. One day. 'Course it'd probably take longer than that if I was to mail one down to my [unintelligible].

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Jack Kiser:

Think it has to go to Greensboro and then come back. Well, I can't imagine gettin' somethin' this morning'. Just one day. (Tape stops, then starts)

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was Jase's brother?

Jack Kiser:

. . .Yeah. [unintelligible] He must a'been married three or four years. Two or three kids. Lived in a log cabin up there with a fireplace. Wife had diapers hangin' on the line [unintelligible]. His brother come over there and just raised hell. Everything stunk and smelt like babies and you know. Jase says, "All right, you've done that two or three days. I think I'll fix it." Said, "That night I stole [unintelligible] and put the baby's stuff [unintelligible]."

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh no!

Jack Kiser:

And said, "You know, after three or four days," he said, "You just couldn't smell anything." He got used to it like I's talkin' about the hogs. (Laughter) He talked a lot. You're not puttin' that down, I hope!

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter) I did.

Jack Kiser:

Gosh! Don't do that. Oh, I wouldn't of told that.

Michelle A. Francis:

(Laughter)

(End Tape)