W.O. Saunders, the editor and founder of Elizabeth City’s newspaper The Independent from 1908 to 1937, was an enigmatic yet straightforward journalist who envisioned himself as a defender of the common man’s plight and as a spokesman for justice. Also deeply ingrained in Saunders’ persona was a yearning to preserve and document the rich, vibrant history of eastern North Carolina, which ultimately led to the publishing of several compilations on topics that ranged from the birth of Virgina Dare in the sixteenth century to the world’s first man-carrying powered flight in the twentieth century.

[Cover]

Two Historic Shrines the Wright Memorial On Kill Devil Hill and Fort Raleigh On Roanoke Island

Tabitha M. DeVisconti

Price 25 Cents

[Page 1]

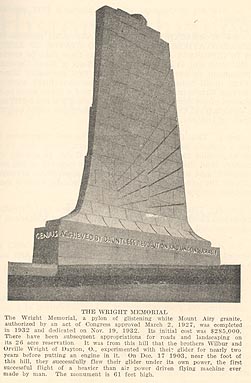

[Caption] The Wright Memorial, a pylon of glistening white Mount Airy granite, authorized by an act of Congress approved March 2, 1927, was completed in 1932 and dedicated on Nov. 19, 1932. Its initial cost was $285,000. There have been subsequent appropriations for roads and landscaping on its 26 acre reservation. It was from this hill that the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright of Dayton, O., experimented with their glider for nearly two years before putting an engine in it. On Dec. 17 1903, near the foot of this hill they successfully flew their glider under its own power, the first successful flight of a heavier than air power driven flying machine ever made by man. The monument is 61 feet high.

[Page 2]

THE ACT OF CONGRESS CREATING THE WRIGHT MEMORIAL

1. The Act of Congress, approved March 2, 1927, provides as follows:

"BE IT ENACTED BY THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN CONGRESS ASSEMBLED.-That there shall be erected on Kill Devil Hill, at Kitty Hawk, in the State of North Carolina, a monument in commemoration of the first successful human attempt in all history at power-driven airplane flight achieved by Orville Wright on December 17,1903; and a commission to be composed of the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of Commerce is hereby created to carry out the purpose of this Act.

Sec. 2. That it shall be the duty of the said commission to select a suitable location for said monument, which shall be as near as possible to the actual site of said flight; to acquire the necessary land therefor; to superintend the erection of the said monument; and to make all necessary and appropriate arrangements for the unveiling and dedication of the same when it shall have been completed.

Sec. 3. That such sum or sums as Congress may hereafter appropriate for the purpose of this Act are hereby authorized to be appropriated.

Sec. 4. The design and plans for the monument shall be subjected to the approval of the Commission of Fine Arts and the Joint Committee on the Library."

2. The Act of March 23, 1928 appropriates as follows:

"Monument on Kill Devil Hill, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina; To commence the work preliminary to the acquisition of a suitable site, surveys, preparation of designs, and all necessary expenses incident to the erection of a monument on Kill Devil Hill at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in commemoration of the first successful human attempt in all history at power-driven airplane flight, in accordance with the Act entitled "An Act providing for the erection of a monument on Kill Devil Hill, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, commemorative of the first successful human attempt in history at power-driven airplane flight" approved March 2,1927,$25,000: Provided, that not to exceed $5,000 of this sum may be expended for the purchase of plans, drawings, and specifications for the erection of this monument by open competition, under such conditions as the Commission may prescribe."

[Page 3]

Two Historic Shrines

The Wright Memorial and Fort Raleigh on Roanoke Island

EDITED BY W. O. SAUNDERS

Founder and Past President of

The Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association

Secretary of the U. S. Roanoke Colony Commission

Published by W. O. SAUNDERS, Elizabeth City, N. C.

Price 25c

[Page 4]

Copyright 1937 by W. O. Saunders

[Page 5]

The Wright Memorial

The Wright Memorial, completed in 1932 and dedicated Nov. 19th 1932 costing $285,000, is one of the most impressive and most beautiful monuments of all time, but it is more than this. The Wright Memorial is a triumph of engineering and a veritable architectural marvel. Nowhere in the world, in the opinion of informed persons, is there anything comparable to this monument.

In the first place, the location of the Wright Memorial is decidedly unique. Perched atop a 91-foot sand dune, this granite pylon gives to the eye the impression of a gigantic bird about to take off from the hilltop.

Anchoring Kill Devil Hill, which until 1929 was a 26-acre mass of drifting sand moving slowly but steadily southward under the impetus of northeast and northwest winds, was in itself an engineering feat of no small distinction. Capt. William H. Kindervater, a construction engineer of the Quartermaster's Corps of the U. S. Army, was sent to Dare County in January, 1929, with orders to place a permanent check on the steady peregrination of the mammouth [mammoth] sand dune. The manner in which Capt. Kindervater accomplished this difficult feat is a story in itself and is told elsewhere in this booklet.

Not only does the location of the monument give it an uniqueness of its own, but its architecture is decidedly different from that of any other monument in the world. The memorial is a 61-foot granite pylon, triangular in shape, with a thirty-nine-foot base and forty-nine-foot sides. These sides are ornamented with gigantic wings in bas relief, the effect of the whole being suggestive of a bird about to launch itself into space.

The monument is sixty-one feet in height and is built upon a 91foot sand hill, the combined height of hill and monument being 151 feet. The foundation of the monument is a concrete core which penetrates down into the center of the big dune for a distance of about thirty-five feet. The monument stands on a star-shaped granite base something like that upon which the Statue of Liberty stands. The walls of the base sink down into the hill to a depth of twelve feet.

To get to the monument there is a meandering ramp leading from the base of the hill by which one climbs by easy stages the eastern side of the hill. The entrance is on the back of the monument, or the base of the triangle. Of special interest are the massive stainless steel doors, the cost of which was $3,000. Each door contains four fanciful engravings representing various parts of the story of man's conquest of the air, including the mythical fellow who fastened a pair of wings to his shoulders and took off into space only to meet with disaster when the sun melted the wax which held the wings into place; the first flight of a balloon and the attempt to fly by threshing the air with a couple of paddles. The doors of the monument are a work of art and are truly interesting.

[Page 6]

ON THE FIRST FLOOR

Passing thru these doors one enters into a hectagonal [hexagonal] room. In the wall on either side is a niche. It is planned to place busts of Orville and Wilbur Wright in these niches. Directly in front of the doors there is a little alcove in which there is to be placed a model of the plane with which the Wrights made aviation history-provided some philanthropic individual will donate the model plane.

Carved in the granite of the west wall is an inscription reading:

"From a point near the base of this hill Wilbur and Orville Wright launched the first flight of a power driven airplane Dec. 17th, 1903."

On the east wall is inscribed Pindar's. "The long toil of the brave is not quenched in darkness nor hath counting the cost fretted away the zeal of their hopes. O'er the fruitful earth and athwart the sea hath passed the light of noble deeds unquenchable forever."

AN UNUSUAL MAP

Curving stairways, one on either side, lead from the first to the second floor, the two stairways connecting with the same platform or landing at the top. On the second floor there is a map of unusual interest. Prepared by Rand & McNally, well-known mapmakers, and engraved upon a slab of stainless steel almost a yard square, this is a map of the world depicting all flights from 1903 to 1928. It is titled the "First Twenty-Five Years of Aviation." Beginning with the first flight by the Wright Brothers on December 17, 1903, the legend of the map lists the flights of Farman, Bleriot, Paulhon, Curtiss, C. P. Rodgers, Garros, the N. C.-4, Alcock & Brown, Ross Smith, Sacduro & Coutinho, the U. S. Army Around the World Flight, J. Rodgers, Byrd, Lindbergh, De Pinedo, Maitland & Hengenberger, the "Bremen" and Kingsford Smith. The route of each of these epochal flights is traced out on the map.

Climbing an iron stairway to the third landing, one then climbs a spiral lighthouse stairway to the top of the monument and steps out onto a small observation platform. Words cannot describe the view from the top of the Wright Memorial. To the East, the Atlantic Ocean, to the West, Kitty Hawk woods and Kitty Hawk Bay, Colington Island, Albemarle Sound, the lower end of Currituck county; to the North a magnificent view of the woods, sand dunes, the beach highway, cottages and, on a clear day, Paul Gamiel's Hill; to the South, the Nags Head woods, the Fresh Ponds, Bodie's Island lighthouse, Roanoke Island and other interesting scenery. The view is incomparable and unequalled. It is worth traveling many miles to see.

LIGHTING IS A PROBLEM

At the very top of the monument is located the large beacon light. This light is a threeway airway light on a horizontal. It is a thousand-watt light, visible for a distance of thirty miles on a clear night. The light will be supplied by commercial current with an auxiliary or emergency power plant at the base of the hill. The beacon will be automatically lighted fifteen minutes after sunset and automatically turned off fifteen minutes after sunrise. In addition to the beacon,

[Page 7]

there is a splendid lighting system inside the monument and eleven floodlights illuminates the monument from all sides at night, making the white granite tower visible for many miles.

Many brain-sweating problems were encountered before engineers and contractors finally turned the monument over to the government. Anchoring the hill was one of the problems; getting the massive blocks of granite to the summit of the hill was another. There are five thousand tons of materials in this monument. Most of this is granite, of which there are more than 20,000 cubic feet. The story of the designing, cutting and transporting of this marble is interestingly told elsewhere in this booklet. The largest block weighed ten tons, a number of others weighed several tons each. Each block was handled about twelve times from the time it was cut until it was set in place on the monument.

Designers of the Wright Memorial were the architectural firm of Rodgers & Poor of New York, whose design won in competition with thirty-five others. The design was approved by the Commission of Fine Arts, the Secretary of War, the Secretary of Navy and the Quartermaster General. The work was done under the Construction Division of the Quartermaster Corps of the U. S. Army Engineers. Capt. John A. Gilman, Q. M. C. was constructing Quartermaster in charge of the job. The builders were the Wills Taylor & Mafera Corporation, of New York City. The first shovelful of dirt marking the beginning of excavation for the foundations of the monument was turned by John A. De Witt, the Quartermaster General, on February 4, 1932. The monument was completed on October 15th. The cost of the monument proper was a little less than the $225,000 appropriated by Congress, but the total cost of the project including the anchoring of the hill, fencing the 200-acre reservation, construction of a road leading to the hill and other incidentals, was close to $285,000. And this represents but an initial investment in a great national monument designed to ultimately cover an area of several square miles and equipped, among other things, with a model airport.

[Page 8]

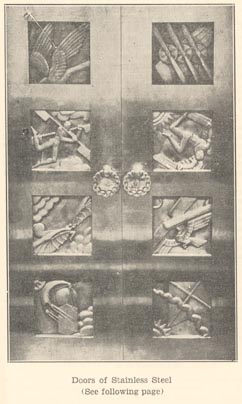

[Caption] Doors of Stainless Steel (See following page)

[Page 9]

Symbolizing Man's Attempts at Conquest of the Air

The stainless metal doors of the Wright Memorial are ornamented with eight panels symbolizing various steps in human efforts at mechanical flight. There is the kite, the balloon, the glider, the plane and the propeller. We behold Icarus of the Greek legend, who flew so near to the sun that the wax that held the feathers of his improvised wings melted and he fell to his death. And there is Besnier with the pole planes who attempted a mechanical flight in the year 1678. The legend of Icarus dates from the year 1100 B. C. Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519) experimented with mechanical flight. In the 16th century an Italian chemist attempted to fly from the walls of Stirling Castle in Galloway, Scotland, with France as his objective. He fell and broke his thigh-bone. He explained the accident by asserting that the wings he employed contained some chicken feathers which had an affinity for the dung-hill, whereas if they had been constructed entirely of eagles' feathers they would have been attracted to the air.

[Page 10]

Anchoring Kill Devil Hill

When your Uncle Sam has a difficult engineering job he turns it over to the War Department. When Congress provided for the erection of a monument to commemorate the first successful airplane flight, on the Kill Devil Hill, there arose the problem of anchoring that massive hill 95 feet high and several acres in extent. Those big sand dunes drift with the winds, moving several feet before the Northeast gales of each recurring winter.

Kill Devil Hill has drifted several hundred feet since the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright conducted their experiments there. Obviously, it would never do to put a quarter million dollar monument atop a sand hill that would in a few years move out from under and spill the monument all over the beach.

The task of anchoring Kill Devil Hill was turned over to the Quartermaster General's Office of the U. S. Army. Q. M. C. Puzzled. Here was a pretty howdy-do. How to anchor a mountain of sand? Who ever heard of such a thing?

Capt. John A. Gilman, Constructing Quartermaster, was called in. Capt. Gilman came down and looked over the job. And then he sent for Capt. William H. Kindervater, a retired Army officer, a Spanish War veteran and an engineer of unusual ability. Capt. Kindervater had cracked hard nuts before. Capt. Kindervater was employed as Superintendent of Construction for the Wright Memorial and the first task assigned him was that of anchoring Kill Devil Hill.

Skeptics scoffed; they said it couldn't be done. In the first place nothing would grow in drifting sands; the winds would blow the seed out as fast as they were planted; if the seed could be made to stick, the blistering summer suns beating down upon a dry sand hill would burn up any vegetation that got started.

Capt. Kindervater moved down to Kitty Hawk, bringing his family with him. He threw a barbed wire fence around the big hill to keep off the beach cattle, the wild ponies and hogs. Then he contracted for enough woods mold to cover the hill and enough brush to cover the woods mold. He sent to Porto Rico for crotalaria seed and to Australia for marram. In the meantime he studied and experimented with every kind of vegetation indigenous to the Carolina coast Hampered for months for lack of money, Capt. Kindervater finally got his work well under way with an appropriation made available in the summer of 1930. To-day the big Kill Devil Hill is anchored, a pallid dune of drifting sand has been translated into a mountain of luxurious verdure.

Native wire grass and bitter tanic [tannic] were the grasses found most suitable for clothing the hill and these grasses are flourishing from base to summit of the big hill to-day. The sands of Kill Devil Hill drift no more. Myrtles, Polk berries, dandelions and yopons [yaupons] are likewise flourishing on Kill Devil Hill. In an experimental tract on one side of the hill Capt Kindervater has growth pumpkins, squash, corn, beans, tomatoes and melons.

[Page 11]

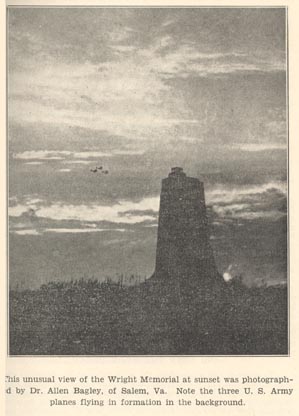

Sunset at Kill Devil Hill

[Caption] This unusual view of the Wright Memorail at sunset was photographed by Dr. Allen Bagley, of Salem, Va. Note the three U. S. Army planes flying in formation in the background.

[Page 12]

The Granite Man's Job

By JOHN P. FRANK

Two cups of feldspar, one of quartz with a sprinkling of black mica; boil and stir vigorously for a few centuries, then place under a mountain to cool. That was the recipe Mother Nature used a million-maybe a billion-years ago in making Mount Airy Granite for the Wright Memorial.

Then, so that man might find this treasure of white granite she moved the Blue Ridge Mountains back a few miles and left a little (about eighty acres) of the top showing. Mother Nature was not discouraged when pre-historic dinosauria and mammoths valued her granite only as a nice place to bask in the sun; nor when countless generations of Indians used the broad acres of stone as an assembly ground for their war councils. She knew that in due time men would set up their puny machines and with more cunning than strength begin to coax and break out great blocks from this boundless store to carve and set up in Arlington Memorial bridges and Wright Memorials. Gross arrogance alone would permit man to claim credit for the lasting beauty and strength which stands for all to see in the Wright Memorial. Man made materials at best may last a few short generations. It is granite-king of Nature's building stones-that alone can brave the fierce ravages of time and live on forever. But, man's part in building the Wright Memorial was not easy.

SHIFTING SANDS

The design and location of the Memorial are particularly appropriate, but offered serious difficulties. Anchoring the shifting sand hill on which the monument stands was a major engineering feat, but is outside the scope of this article. The star shaped base was comparatively easy to executive in granite, but the triangular monument shaft with its massive wing ornaments on two sides packed many a headache for the drafting room and granite cutters.

With a few rapid strokes of his pencil, the architect built a monument on paper. He added a line here and erased another there until he got the right proportions and effect. Then he took a little puttylike plaster of Paris and made himself a model so that he could see exactly how the finished monument was going to look. A line that required only minutes to produce with pencil or putty knife meant hours and even weeks to reproduce in massive granite.

AND THEN THE WORK BEGAN

To make a long story short, the architect sent his drawings and pint sized model to the quarrymen and granite cutters at Mount Airy, N. C., with orders to carve out great blocks of granite so that men ten thousand years from now may know that on Kill Devil Hill fledgling aviation first left its nest-a nest in which lack of imagination and genius had kept it since Icarus flew his wings off and fell in the sea near ancient Greece.

[Page 13]

The graniteman's first job was to make scale drawings showing the shape and size of every piece of stone in the Monument. This was no easy task. Weeks of geometry and trigonometry were required. The curving slope of the Monument's sides complicated by feather lines of the great wings leaves no stones with plain square faces. Almost every dimension had to be figured from imaginary lines and planes.

The draftsmen then made a diagram for each stone. These diagrams tell the granite cutter exactly how the stones must be cut. In addition to the diagram, the draftsman must furnish the cutter with zinc patterns to guide him in cutting curved and irregular lines. The peculiar shapes of stones in the Wright Memorial required four patterns for almost every stone in the job-one pattern for each end, one for the top, and another for the bottom of the stone. Many stones required the fifth pattern so that intricate lines on their faces might be accurately cut. Weeks of tedious work were required to make these diagrams and patterns. A slight inaccuracy in mathematical calculations or of pattern makers shears would result in a stone that would not fit when placed in the monument.

AT THE QUARRIES

Just as soon as the overall sizes have been figured for each stone, the quarrymen start sending stones of the right size and shape into the cutting sheds. The deposit of Mount Airy Granite is a perfectly solid mass hundreds of acres in area and thousands of feet deep. Eighty acres of this tremendous deposit are being actively quarried. By on interesting process call "lifting" (for want of a better name), great sheets of granite are formed by the quarrymen in the solid mass. Some of these sheets are several hundred feet in length and width and may be anywhere from a few inches to ten feet in thickness. Steel wedges driven in rows of holes are used in breaking out blocks of the desired size from the sheets of granite. Aerial cableways and railroad cars are used in delivering the rough blocks of granite to the cutting sheds.

In the cutting sheds, the block of granite with its diagram are turned over to the granite cutters. The first thing the granite cutter does is reduce one side of the rough block to an even and true surface. With this surface as a starting point he proceeds to finish up the other five sides of the stone in accordance with the dimensions and shapes given him on the diagram and patterns. Some of this work is done with machines of various types. Gang and carborundum saws, turning laths, sand blast machines, surfacing machines and other highly specialized equipment are extensively used at Mount Airy, but there remains a great deal of work that can be done only by the hand cutter's chisel and pneumatic tools.

After a stone is finished, it is carefully inspected to see that it u accurately and properly cut. As a further precaution against errors, stones are sometimes assembled on the plant floor.

Next the stones were carefully crated and shipped by rail to Norfolk where they were loaded on barges for delivery near the monument site.

[Page 14]

Orville Wright's Own Story

By ORVILLE WRIGHT

Monday, December 14th, (1903) was a beautiful day, but there was not enough wind to enable a start to be made from the level ground about camp. We therefore decided to attempt a flight from the side of the big Kill Devil Hill. We had arranged with the members of the Kill Devil Hill Life Saving station which was located a little over a mile from our camp, to inform them when we were ready to make the first trial of the machine. We were soon joined by J. T. Daniels, Robert Wescott, Thomas Beacham, W. S. Dough and Uncle Benny O'Neal, of the station, who helped us get the machine to the hill, a quarter of a mile away. We laid the track 150 feet up side of the hill on a 9 degree slope. With the slope of the track, the thrust of the propellors [propellers] and the machine starting directly into the wind, we did not anticipate any trouble in getting up flying speed on the 60-foot monorail track. But we did not feel certain the operator could keep the machine balanced on the track.

THE FIRST ATTEMPT

When the machine had been fastened with a wire to the track, so that it could not start until released by the operator, and the motor had been run to make sure that it was in condition, we tossed up a coin to decide who should have the first trial. Wilbur won. I took a position at one of the wings, intending to help balance the machine as it ran down the track. But when the restraining wire was slipped, the machine started off so quickly I could stay with it only a few feet, After a 35 or 40-foot run, it listed from the rap. But it was allowed to turn up too much. It climbed a few feet, stalled, and then settled to the ground near the foot of the hill, 105 feet below. My stop watch showed that it had been in the air just 3 1/2 seconds. In landing the left wing touched first. The machine swung around, dug the skids into the sand and broke one of them. Several other parts were also broken, but the damage to the machine was not serious. While the test had shown nothing as to whether the power of the motor was sufficient to keep the machine up, since the landing was made many feet below the starting point, the experiment had demonstrated that the method adopted for launching the machine was a safe and practical one. On the whole, we were much pleased.

Two days were consumed in making repairs, and the machine was not ready again till late in the afternoon of the 16th. While we had it out on the track in front of the building, making the final adjustments, a stranger came along. After looking at the machine a few seconds he inquired what it was. When we told him it was a flying machine he asked whether we intended to fly it. We said we did, as soon as we had suitable wind. He looked at it several minutes longer and then, wishing to be courteous, remarked that it looked as if it would fly, if it had a "suitable wind." We were much amused, for, no doubt, he had in mind the recent 75-mile gale when he repeated our words, "a suitable wind!"

[Page 15]

During the night of December 16th, 1903, a strong cold wind blew from the North. When we arose on the morning of the 17th, the puddles of water, which had been standing about the camp since the recent rains, were covered with ice. The wind had a velocity of 10 to 12 metres [meters] per second (22 to 27 miles an hour). We thought it would die down before long, and so remained indoors the early part of the morning. But when ten o'clock arrived, and the wind was as brisk as ever, we decided that we had better get the machine out and attempt a flight. We hung out the signal for the men of the Life Saving station. We thought that by facing the flyer into a strong wind, there ought to be no trouble in launching it from the level ground about camp. We realized the difficulties of flying in so high a wind but estimated that the added dangers in flight would be partly compensated for by the slower speed in landing.

FINAL PREPARATION

We laid the track on a smooth stretch of ground about one hundred feet north of the new building. The biting cold wind made work difficult, and we had to warm up frequently in our living room, where we had a good fire in an improvised stove made of a large carbide can. By the time all was ready, J. T. Daniels, W. S. Dough and A. D. Etheridge, members of the Kill Devil Hill Life Saving station; W. C. Brinkley of Manteo, and Johnny Moore, a boy from Nags Head, had arrived.

We had a "Richard" hand anemometer with which we measured the velocity of the wind. Measurements made just before starting the first flight showed velocities of 11 to 12 metres [meters] per second, or 24 to 27 miles per hour. Measurements made just before the last flight gave between 9 and 10 metres [meters] per second. One made just after showed a little over 8 metres [meters]. The records of the Government Weather Bureau at Kitty Hawk gave the velocity of the wind between the hours of 10:30 and 12 o'clock, Me time during which the four flights were made, as averaging 27 miles at the time of the first flight and 24 miles at the time of the last.

AUDACITY-AND CALCULATION

With all the knowledge and skill acquired in thousands of flights in the last ten years, I would hardly think today of making my first flight on a strange machine in a 27 mile wind, even if I knew that the machine had already been flown and was safe. After these years of experience I look with amazement upon our audacity in attempting flights with a new and untried machine under such circumstances. Yet faith in our calculations and the design of the first machine, based upon our tables of pressures, secured by months of careful laboratory work, and confidence in our system of control developed by three years of actual experience in balancing gliders in the air, had convinced us that the machine was capable of lifting and maintaining itself in the air, and that, with a little practice it could be safely flown.

Wilbur, having used his turn in the unsuccessful attempt on the 14th, the right to the first trial now belonged to me. After running the. motor a few minutes to heat it up, I released the wire that held

[Page 16]

the machine to the track, and the machine started forward in the wind. Wilbur ran at the side of the machine, holding the wing to balance it on the track. Unlike the start on the 14th, made in a calm, the machine, facing a 27-mile wind started very slowly. Wilbur was able to stay with it till it lifted from the track after a forty-foot run. One of the Life Saving men snapped the camera for us, taking a picture just as the machine had reached the end of the track and had risen to a height of about two feet. The slow forward speed of the machine over the ground is clearly shown in the picture by Wilbur's attitude. He stayed along beside the machine without any effort.

FLIGHT

The course of the flight up and down was exceedingly erratic, partly due to the irregularity of the air, and partly to lack of experience in handling this machine. The control of the front rudder was difficult on account of its being balanced too near the center. This gave it a tendency to turn itself when started; so that it turned too far on one side and then too far on the other. As a result the machine would rise suddenly to about ten feet, then as suddenly dart for the ground. A sudden dart when a little over a hundred feet from the end of the track, or a little over 120 feet from the point at which it rose into the air, ended the flight. As the velocity of the wind was over 35 feet per second and the speed of the machine over the ground against this wind ten feet per second, the speed of the machine relative to the au was over 45 feet per second, and the length of the flight was equivalent to a flight of 540 feet made in calm air. This flight lasted only 12 seconds, but it was nevertheless the first in the history of the world in which a machine carrying a man had raised itself by its own power into the air in full flight, had sailed forward without reduction of speed, and had finally landed at a point as high as that from which it started.

With the assistance of our visitors we carried the machine back to the track and prepared for another flight. The wind, however, had chilled us all through, so that before attempting a second flight, we all went to the building again to warm up. Johnny Moore, seeing under the table a box filled with eggs, asked one of the station men where we got so marry of them. The people of the neighborhood eke out a bare existence by catching fish during the short fishing season, and their supplies of other articles of food are limited. He had probably never seen so many eggs at one time in his whole life. The one-addressed jokingly asked him whether he hadn't noticed the small hen running about the outside of the building: "That chicken lays eight or ten eggs a day!" Moore, having just seen a piece of machinery lift itself from the ground and fly, a thing at that time considered as impossible as perpetual motion, was ready to believe nearly anything. But after going out and having a good look at the wonderful fowl, he returned with the remark, "It's only a common looking chicken!"

THE SECOND AND THIRD FLIGHTS

At twenty minutes after eleven Wilbur started on the second flight. The course of this flight was much like that of the first, very much up and down. The speed was faster than the first flight, due to

[Page 17]

the lesser wind. The duration of the flight was less than a second longer than the first, but the distance covered was about 75 feet greater.

Twenty minutes later the third flight started. This one was steadier than the first one an hour before. I was proceeding along pretty well when a sudden gust from the right lifted the machine up twelve to fifteen feet and turned it up sidewise in an alarming manner. It began a lively sidling off to the left. I warped the wings to try to recover the lateral balance and at the same time pointed the machine down to reach the ground as quickly as possible. The lateral control was more effective than I had imagined and before I reached the ground the right wing was lower than the left and struck first. The time of this flight was 15 seconds and the distance over the ground a little over 200 feet.

Wilbur started the fourth and last flight at just 12 o'clock. The first few hundred feet were up and down, as before, but by the time three hundred feet had been covered, the machine was under much better control. The course of the next four or five hundred feet had but little undulation. However, when out about eight hundred feet, the machine began pitching again, and, in one of its darts downwards, struck the ground. The distance over the ground was measured and found to be 852 feet; the time of the flight 59 seconds. The frame supporting the front rudder was badly broken, but the main part of the machine was not injured at all. We estimated that the machine could be put in condition for flight again in a day or two.

While we were standing about discussing this last flight, a sudden strong gust of wind struck the machine and began to turn it over. Everybody made a rush fur it. Wilbur, who was at one end; seized it in front, Mr. Daniels and I, who were behind, tried to stop it by holding the rear uprights. All our efforts were in vain. The machine rolled over and over. Daniels, who had retained his grip was carried along with it, and was thrown about head over heels inside of the machine. Fortunately he was not seriously injured, though badly bruised in falling about against the motor, chains, guides, etc. The ribs in the surface of the machine were broken, the motor injured and the chain guides badly bent, so that all possibility of further flights with it for that year were at an end.

[Page 18]

America's First Airplane Casualty

By W. 0. SAUNDERS

(As Published in Collier's Weekly, Sept. 17, 1927.)

I found him at the wheel of a clumsy old ferryboat plying between the towns of Morehead City and Beaufort on the North Carolina coast-a rugged, bronzed, gray-eyed, gray-haired son of Neptune, steering his craft cunningly through the tortuous channel of a harbor beset by the conflicting currents of many inland waters where they meet and mingle with the tides and currents of the open sea.

"I rather expected to find you piloting an aircraft by this time," I said to him by the way of opening conversation.

"Who, me?" replied the ferryman. "No, sir, the only way they'll ever get me in one of them airplanes again will be to put me in irons and strap me in. I reckon I'm the proudest man in the world to-day because I was the first man ever wrecked in an airplane, but I've had all the thrill I ever want in an airplane; I wouldn't take a million now for the first thrill, but you couldn't give me a million to risk another."

Captain John T. Daniels, America's first airplane casualty, figgured [figured] in the wreck of the first power-driven heavier-than-air flying machine ever flown, at Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on that epochal morning of December 17, 1903. -

John Daniels was one of a little group of natives of the North Carolina coastland who stood by at Kill Devil Hills that morning when Wilbur and Orville Wright prepared to try out' their first power-driven airplane. The brothers Wright had to have help in handling that first plane, and Captain Daniels, then a patrolman on duty attire Kill Devil Hills Coast Guard Station, volunteered as one of their helpers.

"It's just like yesterday to me," said Captain Daniels. "The Wrights got their machine out of its shed that morning, and we helped them roll it out to the foot of the big hill, on a monorail.

"That first plane had only one wheel to roll on, not like the planes now that have two wheels. It couldn't stand up without somebody supporting it at each end, and I had hold of one of the wings on one end.

"It was a sad time, I'm telling you. We'd been watching them

Wright boys from our station for three years and visiting them at their camp.

"When they first came down to Kill Devil Hills in the summer of

1900 and began to experiment with their funny-looking kites we just

thought they were a pair of crazy fools. We laughed about 'em among

[Page 19]

ourselves for a while, but we soon quit laughing and just felt sorry for 'em, because they were as nice boys as you'd ever hoped to see.

"They didn't put themselves out to get acquainted with anybody, just stuck to themselves, and we had to get acquainted with them. They were two of the workingest boys I ever saw, and when they worked THEY WORKED.

THE DAYTON GANNETS

"I never saw men so wrapped up in their work in my life. They had their whole heart and soul in what they were doing, and when they were working we could come around and stand right over them and they wouldn't pay any more attention t0 us than if we weren't there at all. After their day's work was over they were different; then they were the nicest fellows you ever saw and treated us fine.

"The Wrights came down to Kill Devil Hills, where they could find a good elevation for trying out their glider, where there were good winds almost all the time, where they would have a soft place to land almost anywhere when their glider came down, and where they wouldn't be bothered by outsiders. They didn't seem to mind us natives.

"Well, they hadn't been down there long before we just naturally learned to love 'em-such nice boys wasting their time playing with kites and watching the gulls fly. They were such smart boys-natural born mechanics-and could do anything they put their hands to. They built their own camp; they took an old carbide can and made a stove of it; they took a bicycle and geared the thing up so that they could ride it on the sand. They did their own cooking and washing; and they were good cooks too.

"But we couldn't help thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts. We'd watch them from the windows of our station. They'd stand on the beach for hours at a time just looking at the gulls flying, soaring, dipping. They seemed to be interested mostly in gannets. Gannets are big gulls with a wing spread of five or six feet. They would watch gannets for hours.

"They would watch the gannets and imitate the movements of their wings with their arms and hands. They could imitate every movement of the wings of those gannets; we thought they were crazy, but we just had to admire the way they could move their arms this way and that and bend their elbows and wrist bones up and down and every which a way, just like the gannets moved their wings.

"But they were a long way from being fools. We began to see that when they got their glider working so that they could jump off into a wind off that hill and stay in the air for several minutes, gradually gliding down to the beach almost as graceful as a gannet could have done it.

"We knew they were going to fly, but we didn't know what was going to happen when they did. We had watched them for several years and saw how they figured everything out before they attempted it.

[Page 20]

MY FIRST FLIGHT-AND LAST

"We had seen the glider fly without an engine, and when those boys put an engine in it we knew that they knew exactly what they were doing.

"Adam Etheridge, Will Dough, W. C. Brinkley, Johnny Moore and myself were there on the morning of December 17th. We were a serious lot. Nobody felt like talking.

"Wilbur and Orville walked off from us and stood close together on the beach, talking low to each other for some time. After a while they shook hands, and we couldn't help notice how they held on to each other's hand, sort o' like they hated to let go; like two folks parting who weren't sure they'd ever see each other again.

"Wilbur came over to us and told us not to look sad, but to laugh and hollo and clap our hands and try to cheer Orville up when he started.

"We tried to shout and hollo, but it was mighty week shouting, with no heart in it.

"Orville climbed into the machine, the engine was started up, and we helped steady it down the monorail until it got under way. The thing went off with a rush, and left the rail as pretty as you please, going straight out into the air maybe 120 feet when one of its wings tilted and caught in the sand, and the thing stopped.

"We got it back up on the hill again, and this time Wilbur got in. The machine got a better start this time and went off like a bird. It flew about a quarter of a mile, but was flying low and Wilbur must have miscalculated the height of a sand ridge just where he expected to turn, and the rudder hit the sand. He brought the plane down and we dragged it back to the hill again.

"They were going to fix the rudder and try another flight when I got my first-and God Help me-my last flight.

"A breeze that had been blowing about twenty-five miles an hour suddenly jumped to thirty-five miles or more, caught the wings of the plane, and swept it across the beach just like you've seen an umbrella turned inside out and loose in the wind. I had hold of an upright of one of the wings when the wind caught it, and I got tangled up in the wires that held the thing together.

"I can't tell to save my life how it happened, but I found myself caught in them wires and the machine blowing across the beach heading for the ocean, landing first on one end and then on the other, rolling over and over, and me getting more tangled up in it all the time. I tell you, I was plumb scared. When the thing did stop for half a second I nearly broke up every wire and upright getting out of it.

THEY THOUGHT IT WAS A FAKE

"I wasn't hurt much; I got a good many bruises and scratches and was so scared I couldn't walk straight for a few minutes. But the Wrights boys ran up to me, pulled my legs and arms, felt of my ribs and told me there were no bones broken. They looked scared too.

"The machine was a total wreck. The Wrights took it to pieces,

[Page 21]

packed it up in boxes and shipped it back to their home in Dayton. They gave us a few pieces for souvenirs, and I have a piece of the upright that I had hold of when it caught me up and blew away with me.

"We didn't see anything more of the Wright boys until the spring of 1908. You see they had to do a lot of work back in Dayton to fix that machine up with wings that would take advantage of shifting' winds instead o' keeling over to 'em. ,

"when they finally came back, the newspaper fellows got onto them. A man named Salley came down from Norfolk, hid out in a marsh about a mile away from the camp, and sent out the first newspaper story.

"I remember a lot of papers wouldn't print it and thought Salley was faking.

"But some of the papers printed the telegram, and then the newspaper men from up North began to flock down to Kill Devil Hills to see for themselves.

"But none of those newspaper men ever got close enough to the machine to tell the truth about it, and none of 'em talked to the Wrights. The Wrights wouldn't even take the machine out of its shed when they discovered the newspaper men around. It was funny the way those New York newspaper men hid around in the bushes, a mile or more away from the Wright's camp and wrote interviews with Wilbur and Orville. But I reckon they had to earn their money somehow."

Captain Daniels warped the Morehead City-Beaufort ferryboat into its dock at Beaufort and rested on his wheel while his eyes scanned the horizon far out on the open sea.

"The little rascal Lindbergh, who flew from New York to Paris, is telling it that running a flying machine is as safe as running an automobile and a whole lot easier. Maybe so; I'm not denying it. As for me. I want the deck of a good old boat or the solid earth under my feet. I got caught up in an airplane once, and that was enough for me 'I like to think about it now; I like to think about that first airplane the way it sailed off in the air at Kill Devil Hills that morning as pretty as any bird you ever laid your eyes on. I don't think I ever saw a prettier sight in my life. Its wings and uprights were braced with new and shiny copper piano wires. The sun was shining bright that morning, and the wires just blazed in the sunlight like gold. The machine looked like some big, graceful golden bird sailing off into the wind.

"I think it made us all feel kind o' meek and prayerful like. It might have been a circus for some folks, but it wasn't any circus for us who had lived close by those Wright boys during all the months until we were as much wrapped up in the fate of the thing as they were.

"It wasn't luck that made them fly; it was hard work and hard common sense; they put their whole heart and soul and all their energy into an idea and they had the faith. Good Lord, I'm a-wondering what all of us could do if we had faith in our ideas and put all cur heart and mind and energy into them like those Wright boys did!"

(Copyright 1927, by Collier's The National Weekly)

[Page 22]

Kill Devil Hills! Kitty Hawk!

How did the group of sand dunes known as Kill Devil Hills and the village known as Kitty Hawk come by their unusual names? Many legends supply the answer.

"The legend generally accepted in respect of Kill Devil Hills relates that it was among these sand dunes that smugglers of the eighteenth century traded rum for the salt fish, tobacco and other products of the coast and the nearby mainland. The vile quality of the rum purveyed by the smugglers was called "Kill Devil" by the natives, and the name given that rum in the long ago still clings to the hills that were once the rendezvous of smugglers.

The popularly accepted legend with respect of Kitty Hawk relates that its name is a corruption of "Killa Honk" or "Kills Honk." What is now Kitty Hawk was formerly a favorite winter feeding ground and refuge for the Canada wild goose. Just across Currituck Sound from Kitty Hawk Bay is the tip of the Currituck peninsula where an Indian village was established, the remains of which are visible to this day. Legend says that in the late fall of any year when the wild geese came down from the north and began to congregate in Kitty Hawk Bay, the Indian, borrowing the white man's vernacular. said: "Kills Honk!"; which was his terse way of saying: "I think I'll paddle my canoe across the Sound and kill a honker," meaning wild goose. And so Kitty Hawk Bay came by its name. Old deeds and other records still in existence in Currituck show that the Kitty Hawk locality has been variously designated as Kills, Honk, Killy Honk, Kitty Honk and Kitty Hawk, the latter having come to be accepted in late years.

[Page 23]

History in the Making

So able a newspaper as the New York Herald suspended a noted correspondent in 1908 because he gave them the news of the first prolonged flight made by the Wright Brothers in their heavier-than-air flying machine at Kill Devil Hills. And the Cleveland (O.) Leader refused to pay telegraph tolls on a story of that flight from a local correspondent. Alpheus W. Drinkwater, veteran telegraph operator in charge of the U. S. Weather Bureau station at Manteo on Roanoke Island recalls both incidents and more. Mr. Drinkwater says:

"The flight of the first heavier-than-air machine to leave the ground and actually fly with a pilot, on Dec. 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, N. C., lasted less than 12 seconds and covered only some over 120 feet. However it was sufficient to convince the Wright Brothers, Wilbur and Orville that they had at last perfected a machine that could actually fly, and it was on this date that they wired their sister Katherine at Dayton, Ohio, telling of their successful flight and of their returning home for Christmas.

"How this news leaked to the outside world through Harry P. Moore of the Virginian-Pilot at Norfolk, Va., has never been revealed, the man who gave him the story has never been revealed, the man who gave him the story has never been mentioned in any account of the early flight of the Wrights. I regret that I cannot now reveal his identity.

"When President Hoover visited Kill Devil hills several years ago to select a site for the Present monument he was very anxious to know how this story reached the outside world, so quickly I told him I could not tell him and referred him and Mr. Mark Sullivan to Harry Moore. I know how Moore got the story but it was his story and he can tell it if he likes, otherwise I must let people think he got his information from the barrel of oysters he saw shipped from Norfolk to the Wrights at Kitty Hawk, but he knows and I know differently.

"After this flight the Wrights immediately packed up and returned to Dayton, and the next we hear of them is when Wilbur visited Europe in 1906 with a view of interesting foreign nations in purchasing his machine after he had obtained patents in this country and had been unsuccessful in interesting this government in obtaining aid for his experiments.

"In the spring of 1908 we find the Wright Brothers again at Kitty Hawk, and on May the 6th they made their first flight in the new machine on which they had been working since 1903. D. Bruce Salley of the Norfolk Landmark had already received information of their presence at Kill Devil Hill and that they would shortly attempt to fly. Salley did not receive his information from the same source as did Mr. Moore. As the Wrights would not permit any strangers near their place it was necessary for Salley to leave Manteo before daylight and hide in the woods near Kill Devil Hill. He waited several days before they found the weather right for a flight, but on the afternoon of May 6, 1908 they made a flight of one thousand feet. Salley immediately returned to Manteo and filed a story of five or six hundred words; this

[Page 24]

story was sent to the Norfolk Landmark, W. F. Bullock, Times Building, New York; The Herald, New York; The Post Washington; The Times, New York; The World, New York; and the Sun, Baltimore. Queries sent to various papers throughout the country brought no response.

"On May 8th, 1908 they made several flights, the longest of which was one mile, but this flight was made for the purpose of testing out the steering gear. The ability of the machine to rise, soar and light was again thoroughly demonstrated. It was at all times under the perfect control of the navigator. Salley sent 600 words to the various papers.

"The next flight worthy of mention was on May 11, 1908. There were four flights on this day, the longest was two and seven-sixteenths miles as computed by the telegraph poles of the United States Weather Bureau Sea Coast Telegraph lines, the greatest speed being 46.774 miles an hour according to Salley's story. This story Salley sent to all his New York, Baltimore, Washington and Norfolk papers. He also sent the same story to the Cleveland Leader which promptly refused to pay the telegraph charges and wired Salley to cut that "Wild Cat stuff," they could not handle it. He promptly wired them he was not in the habit of filing, "Wild Cat stuff."

"On May 11th there arrived at Manteo a flock of newspaper men, among whom was Byron R. Newton, staff correspondent of the New York Herald. Newton handed Mr. Salley a letter saying he would look after the Herald's interests and that Salley must confine his stories to facts, if he expected the Herald to use them. Mr. McGowan of the London Daily Mall, William Hester of the New York American, Arthur Ruhl and Jimmie Hare of Collier's Weekly were among the reporters.

"On May the 19th all the reporters got an early start and were all set when the Wrights made their flights, which were short ones. Salley estimated their speed on this date between forty and sixty miles an hour and quotes Wilbur Wright as saying when asked if an aeroplane [airplane] could be made to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, `That is impossible with the gasoline engine as the motive power:

"It was on this day that McGowan wrote his story with a pencil while making the trip, from Kill Devil Hill to Manteo. Immediately on arrival at Manteo about five P. M. McGowan came direct to the office and gave me about eighteen hundred words to send. Before this was finished the other reporters arrived and began to file their stories at the same time. McGowan took a magazine and marked off two pages for me to send and informed the other reporters that he was the first to reach the office and that he proposed to use the wire exclusively the rest of the day, before I could explain to him that he was not in Russia or Japan from which points he had just arrived and where the reporter reaching the cable office could have preference as long as he furnished copy. Hoster of the N. Y. American immediately grabbed a chair and threatened to break it over his head. Mr. Newton and Mr. Salley soon reconciled them and I then explained to him that this was a government office and that it closed at 4 P. M., and I was doing this as a matter of accommodation and not that I was required to, and that

[Page 25]

in the future no reporter should file over five hundred words at one time and the one coming first today should be last tomorrow. From then on everything went well, until May 14, 1908, when the machine was wrecked after making eight miles, the longest flight of the experiment, this ended the Wrights experiment for the time being; they immediately packed up and went to Dayton.

"The next time we hear of them is Orville Wright at Fort Myer, Va., where aviation claims its first victim in the person of Lieut. T. E. Selfridge, U. S. A., who was killed on Sept. 17, 1908. Wilbur Wright was at Le Mans, Fance, where his demonstrations and brilliant work was acclaimed by the European authorities as the successful solution of the problem of mechanical flight.

"It might be interesting to note that although the New York Herald sent their own correspondent in the person of Byron R. Newton, who later became Secretary of the Treasury under President Wilson's administration, that they should suspend him for six weeks without pay for the story he sent in. In later years in discussing this matter with Mr. Newton he said that his `misfortune was softened and sweetened somewhat with the consciousness that I had faithfully covered the most important assignment of my life and had written the true story of perhaps the greatest achievement of my generation.'

"During the week those flights were made my office handled over 42,000 words of press. We usually started sending the London dispatches about three o'clock followed by the Norfolk papers; after that we had direct wire from Manteo to the various newspapers and often sent until 2 A. M. Mrs. Drinkwater and Mr. Salley who was an operator, often relieved me. We had only one wire on a bracket line to Norfolk via Cape Henry and it was at times almost impossible to work it, especially at night when the wires were damp, but we were very fortunate in not having a serious breakdown during the experiments I still have the original dispatches in my possession. President Hoover, when he visited my office on March 19, 1927, took them to Washington and had them mounted on Japanese linen. I have had several requests to donate them to various museums but I think they should be placed in the Wright Memorial at Kill Devil Hill. I may do this some day if I get able."

[Page 26]

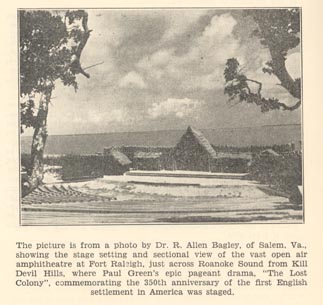

[Caption] The picture if from a photo by Dr. R. Allen Bagley, of Salem, Va., showing the stage setting and sectional view of the vast open air amphitheatre at Fort Raliegh, just across Roanoke Sound from Kill Devil Hills, where Paul Green's epic pageant drama, "The Lost Colony", commemorating the 350th anniversary of the first English settlement in America was staged.

[Page 27]

Another Historic Shrine

THE ROANOKE ISLAND SETTLEMENTS

The first English settlements in America were made on Roanoke Island in what is now Dane County, North Carolina.

An expedition headed by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe Planted the English flag on the shores of Roanoke Island in 1584. Two major efforts to establish colonies on the island were made, in 1585 and again in 1587.

It was not until 1607 that the English established a settlement at Jamestown, on the James River in what is now Virginia, and it was not until 1620 that the Pilgrim Fathers came to Plymouth Rock in what is now Massachusetts.

And yet, Jamestown and Plymouth Rock, having been given a wealth of publicity that Roanoke Island never received, are associated in the minds of most adult Americans as the first English settlements in America. Hence this chapter which attempts to reveal Roanoke Island's indisputable claim to the unique distinction of being the factual birthplace of English-speaking civilization in North America.

Actually, the first discovery of America and the first attempt at settlement on its Atlantic seaboard, of which we have historical record, was made by Leif Erickson in the year 1001 A. D. With a party of 35 the redoubtable Swede landed on the coast of what is now Massachusetts, cut down trees and built themselves houses. The settlement was short lived.

BEFORE ROANOKE ISLAND

But, before Roanoke Island and Jamestown, the Spaniards and the French had made many explorations and established many colonies. Columbus discovered America in 1492. Then came Balboa in 1513, Ponce de Leon in 1521. And in 1528 Panfilo de Narvaez landed a force of 300 men with horses and trappings at Apalache Bay, "prepared to take the country in true Spanish fashion."

Eighty years before the English camp to Jamestown, the Spaniard Vasquez de Ayllon had built houses and planned a lasting colony on Jamestown Island. He had brought up with him from Santo Domingo no fewer than 500 persons. But discord, fever and death put an end to this venture and scarcely 150 of de Ayllon's band of 500 found their way back to Santo Domingo.

And whilst the Spanish were busy in the conquest of the Florida and Gulf coasts, the French were as actively engaged in exploring and settling the farther north. The French explorer, Jacques Cartier, had penetrated the St. Lawrence River as far as the present site of Montreal in 1534-35, and in 1541 he planted a rude but upon the heights of Quebec.

Even in Florida, settlements of French Huguenots were effected in 1562-64, only to be destroyed by the Spanish who, in turn, founded St. Augustine in 1565.

[Page 28]

But let's return to the English.

Newfoundland was well known as a trading and fishing port in England as early as 1504 A. D. and as early as 1570 as many as 40 ships went annually from English ports to take part in the fishing there.

John Cabot of England had visited the coast of North America as early as 1497. But he attempted no settlement.

In 1583 Sir Humphrey Gilbert landed a fleet of five ships on the coast of New Foundland, but he attempted no settlement. Sir Humphrey lost his life when his ship went down in a tempest on the return voyage to England.

Associated with Sir Humphrey was a kinsman, Sir Walter Raleigh, an intrepid Soldier of Fortune and adventurer who stood in great favor with England's then reigning Queen, Elizabeth. Sir Walter not only had the favor and confidence of his queen, but must have enjoyed the confidence and esteem of the nobility and commercial leaders of his time as well. Undismayed by the unhappy ending of Sir Humphrey's expedition and convinced that English settlement in America should be attempted somewhere midway between Florida and New Foundland, Sir Walter obtained a patent from Queen Elizabeth and sent an expedition to America in 1584 to select the site for a colony.

THE FIRST EXPEDITION

The expedition headed by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe entered the inland waters of North Carolina through a shallow inlet about 21 miles north of Roanoke Island sometime in July, 1584 and took possession of the country for England. After some commerce with the Indians and some scouting, Amadas and Barlowe discovered Roanoke Island, were overwhelmed by the natural wealth and beauty of this island paradise and selected Roanoke Island for the site of a permanent English settlement in America.

Returning to England in the autumn of 1584, they took with them two Indians, Manteo and Wanchese, for whom the principal villages on Roanoke Island are named. They took with them, too, specimens of tobacco, sassafras, maize, pumpkins, squash and other fruits and herbs new and strange to their countrymen. Amusing tales of the efforts of Sir Walter and his Queen to acquire the tobacco habit have been handed down to us. But B they never quite acquired a taste for tobacco, they at least gave a sanction and impetus to a habit that has since spread among all nations of the earth and given rise to one of the greatest industries of modern times, the manufacture of cigars and cigarettes.

In 1585 Sir Walter Raleigh fitted out another expedition under Sir Richard Grenville to transport 108 colonists to Roanoke Island to attempt a permanent settlement on the site selected by Amadas and Barlowe. Ralph Lane was Governor of the Colony. This expedition landed on Roanoke Island on August 17, 1585. Grenville returned to England. Fort Raleigh, a crude structure of logs, was built. They built houses too. The colony encountered

[Page 29]

much trouble with the Indians and, reduced almost to starvation, returned to England in 1586 aboard the fleet of Sir Francis Drake. Two weeks after the departure of the colony, Grenville arrived with supplies and men. He left 15 men on Roanoke Island. When in 1587 another expedition equipped and financed by Sir Walter and some business associates and headed by Governor John White, came to Roanoke Island, Fort Raleigh was in ruins and the 15 men who had been left behind in 1586 were nowhere to be found.

John White and the new settlers restored the fort, built houses, attempted to reestablish friendly relations with the Indians and on August 13, 1587, the first religious sacrament in the Protestant faith ever solemnized in the New World was performed. Manteo, the friendly native, was baptized.

On August 18, 1587, Virginia Dare, the first child born of English parents in America, was born and was christened the following Sunday morning.

The 350th anniversary of that occasion was commemorated on Aug. 18, 1937, with appropriate exercises, honored by the presence of Franklin D, Roosevelt, President of the United States and other notables.

THE LOST COLONY

John White left his colony of more than one hundren [hundred] men, women and children on Roanoke Island in 1587 to return to England for additional colonists and supplies. England was at war with Spain and neither ships nor men could be spared for private expeditionary purposes at that time. It was not until 1590 that John White returned to look after the colony on Roanoke Island. Too late! The colony had perished or had been dispersed and no satisfactory trace of it has ever been found. The fate of the Lost Colony and of Virginia Dare may never be determined.

From 1587 to 1602 it is said that Sir Walter Raleigh sent five expeditions to America in quest of the Lost Colony, without success. In 1603 his devoted Queen, Elizabeth, died and Sir Walter, broken in health and purse, was thrown into prison on a charge of treason. Had Elizabeth lived, the intrepid Sir Walter would have pursued his dream of permanent settlement in America. It remained for Capt. John Smith and associates, inspired by Sir Walter and aided by ten of his associates to effect a permanent settlement on Jamestown Island in Virginia in 1607. Factually, English-speaking civilization in America was rooted at Jamestown, Va.; but it had its birth and inspiration on Roanoke Island.

FOR THE GOOD OF HUMANITY

"Fortunate, indeed, was it for America and humanity," says the historian Ashe, "that this first lodgment on our stormy coast (the Amadas and Barlowe expedition of 1584) was by a race devoted to the Protestant faith, ardently attached to freedom and personal liberty, and trained to the usages and customs of the

[Page 30]

realm of England. Different certainly the world's history would have been had Raleigh not blazed the way in English colonization, and had the dominion of the Spaniards under the papal bull of Alexander been permanently established throughout the Atlantic slope of America."

Here on the wooded bluffs of a picturesque island whose shores are washed by the waters of four North Carolina inland sounds, English civilization in America had its birth and its beginnings. Had the Raleigh settlements been attempted in Virginia, or in Massachusetts, volumes would have been written about them and they would have been exploited as the most significant facts in the history of America.

Significant enough, just across the waters of Roanoke Sound from Roanoke Island stand the Kill Devil Hills and their Wright Memorial. The beam from the beacon of the Wright Memorial sweeps the shores of Roanoke Island and old Fort Raleigh; the light of a new and resplendent civilization cleaving a darkness that has persisted for more than three and a half centuries, where the embers of the first fires of English civilization on these shores turned ashes. Here then are America's two most impressive historic shrines, to which vast throngs pay homage annually.

| Citation: | W.O. Saunders, "Two Historic Shrines," 1937. Tabitha Marie DeVisconti Papers, #480 |

| Location: | East Carolina Manuscript Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books, Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858 USA |

| Call Number: | NoCar Ref QE147 .A2 v.3 Display Finding Aid |