[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

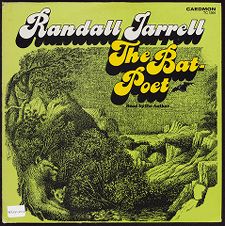

Randall Jarrell (0:04)

Once upon a time, there was a bat a little light brown bat the color of coffee with cream in it. He looked like a furry mouse with wings. When I go in and out my front door in the daytime, I'd look up over my head and see him hanging upside down from the roof of the porch. He and the others hung there in a bunch all snuggled together with their wings folded fast asleep. Sometimes one of them would wake up for a minute and get in a more comfortable position. And then the others would wriggle around in their sleep till they'd got more comfortable too; when they all moved, it looked as if a fur wave went over them. At night, they fly up and down, around and around and catch insects and eat them. On a rainy night though, they'd stay snuggled together just as though it were still day. If you point a flashlight at them, you'd see them screw up their faces to keep the light out in their eyes.

(1:11)

Toward the end of summer, all the bats except the little brown one, began sleeping in the barn. He missed them and tried to get them to come back and sleep on the porch with him. What do you want to sleep in the barn for? He asked them. We don't know. The others said, What do you want to sleep on the porch for? It's where we always sleep. He said, If I slept in the barn, I'd be homesick. Do come back and sleep with me. But they wouldn't. So he had to sleep all alone. He missed the others. They had always felt so warm and very against him. Whenever he'd wake, he'd pushed himself up into the middle of them and gone right back to sleep. Now he'd wake up and instead of snuggling against the others and going back to sleep, he would just hang there and think. Sometimes he would open his eyes a little and look out into the sunlight. It gave him a queer feeling for it to be daytime. And for him to be hanging there looking. He felt the way you would feel if you woke up and went to the window and stayed there for hours looking out into the moonlight. It was different in the daytime. The squirrels and the chipmunk that he had never seen before.

(2:38)

At night they were curled up in their nests or holes fast asleep, ate nuts and acorns and seeds and ran after each other playing. And all the birds hopped and sang and flew. At night they had always been asleep except for the mockingbird. The bat had always heard the mockingbird. The mockingbird would sit on the highest branch of a tree in the moonlight and sing half the night. The bat loved to listen to him. He could imitate all the other birds. He'd imitate even the way the squirrels chattered when they were angry, like two rocks being knocked together. And he could imitate the milk bottles being put down on the porch. And the barn door closing, a long rusty squeak. And he made up songs and words all his own that nobody else had ever said or sung. The bat told the other bats about all the things you could see and hear in the daytime. You'd love them. He said the next time you wake up in the daytime. Just keep your eyes open for a while and don't go back to sleep. The other bats were sure they wouldn't like that. We wish we didn't wake up at all. They said when you wake up in the daytime the light hurts your eyes. The thing to do is to close them and go right back to sleep. Days to sleep in. As soon as it's night we'll open our eyes. But won't you even try it? The little brown bat said just for once, try it. The bats all said no. But why not? Asked the little brown bat. The bats said. We don't know. We just don't want to. At least listen to the mockingbird. When you hear him it's just like the daytime. The other bats said. You sound so queer. If only he squeaked or twittered, but he keeps shouting in that bass voice of his. They said this because the mockingbird's voice sounded terribly loud and deep to them. They always made little high twittering sounds themselves. Once you get used to it, you'lI like it the little bat said, once you get used to it, it sounds wonderful. All right, said the others we will try. But they were just being polite, they didn't try. The little brown bat kept waking up in the daytime, and kept listening to the mockingbird.

(5:22)

Until one day he thought I could make up a song like the mockingbird's. But when he tried his high notes were all high, and his low notes were all high, and the notes in between were all high. He couldn't make a tune. So he imitated the mockingbirds words instead. And first his words didn't go together. Even the bat could see that they didn't sound a bit like the mockingbird's.

(5:53)

But after a while, some of them began to sound beautiful. So that the bat said to himself. If you get the word right, you don't need a tune. The bat went over and over his words, till he could say them off by heart. That night, he said them to the other bats. I made the words like the mockingbird's, he told them, so you can tell what it's like in the daytime. Then he said to them in a deep voice. He couldn't help imitating the mockingbird. His words about the daytime.

(6:33)

At dawn, the sun shines like a million moons. And all the shadows are as bright as moonlight the birds begin to sing with all their might. The world awakens and forgets the night. The black and gray turns green and golden blue. The squirrels begin to- but when he got this far, the other bats just couldn't keep quiet any longer. The sun hurts, said one. It hurts like getting something in your eyes. That's right said another. And shadows are black. How can a shadow be bright? Another one said, What's green and gold and blue. When you say things like that. We don't know what you mean. It's just not real. The first one said when the sun rises the world goes to sleep. But go on said one of the others. We didn't mean to interrupt, you know, we're sorry. We interrupted you all the other said, say us the rest. But when the bat tried to say them the rest. He couldn't remember a word. It was hard to say anything at all. But finally he said I-I- tomorrow, I'll say you the rest. Then he flew back to the porch. There were lots of insects flying around the light. But he didn't catch one. Instead, he flew to his rafter, hung there upside down when his wings folded. And after a while, went to sleep. But he kept on making poems like the mockingbird's. Only now he didn't say them to the bats.

(8:25)

One night, he saw a mother possum with all their little white baby possums holding tight to her eating the fallen apples under the apple tree. One night, an owl swooped down on him and came so close he'd have caught him if the bat hadn't flown into a hole in the old oak by the side of the house. And another time four squirrels spent the whole morning chasing each other up and down trees across the lawn and over the roof. He made up poems about them all. Sometimes the poem would make him think it's like the mockingbird. This time it's really like the mockingbird. But sometimes the poem would seem so bad to him that he'd get discouraged and stop in the middle. And by the next day he'd have forgotten it. When he would wake up in the daytime and hang there looking out at the colors of the world. He would say the poems over to himself. He wanted to say them to the other bats. But then he would remember what had happened when he'd said them before.

(9:37)

There was nobody for him to say the poems to. One day he thought I could say them to the mockingbird. It got to be a regular thought of his. It was a long time though before he really went to the mockingbird.

(9:54)

The mockingbird had bad days when he would try to drive everything out of the yard no matter what it was, he always had a peremptory, authoritative look as if he were more alive than anything else and wanted everything else to know it. On his bad days he'd dive on everything that came into the yard. On cats and dogs even and strike at them with his little sharp beak and sharp claws. On his good days, he didn't pay so much attention to the world but just sang. The day the bat went to him the mockingbird was perched on the highest branch of the big willow by the porch, singing with all his might. He was a clear gray, with white bars across his wings that flashed when he flew. Every part of him had a clear, quick, decided look about it. He was standing on tiptoe, singing and singing and singing. Sometimes he'd spring up into the air. This time he was singing a song about mockingbirds. The bat fluttered to the nearest branch, hung upside down from it and listened. Finally, when the mockingbird stopped for a moment, he said in his little high voice. It's beautiful. Just beautiful. You like poetry? Asked the mockingbird. You could tell from the way he said it that he was surprised. I love it. Said the bat. I listen to you every night. Every day too. I-I-. It's the last poem I've composed. Said the mockingbird. It's called to a mockingbird. It's wonderful. The bat said. Wonderful. Of all the songs I ever heard you sing. It's the best. This pleased the mockingbird. Mockingbirds love to be told that their last song is the best. I'll sing it for you again. The Mockingbird offered. Oh please do sing it again said the bat. I'd love to hear it again. Just love to only when you've finished could I-. The mockingbird had already started. He not only saying it again. He made up new parts and sang them over and over and over. They were so beautiful that the bat forgot about his own poem and just listened. When the mockingbird had finished the bat thought no, I just can't say mine. Still though. He said to the mockingbird. It's wonderful to get to hear you. I could listen to you forever.

(12:49)

It's a pleasure to sing to such a responsive audience. Said the mockingbird. Any time you'd like to hear it again, just tell me. The bat said could could. Yes? Said the mockingbird. The bat went on in a shy voice. Do you suppose that I- that I could. The mockingbird said warmly that you could hear it again? Of course you can. I'll be delighted. And he sang it all over again. This time, it was the best of all. The bat told him so, and the mockingbird looked pleased but modest. It was easy for him to look pleased but hard for him to look modest. He was so full of himself. The bat asked him do you suppose a bat could make poems like yours? A bat? The mockingbird said. But then he went on politely, well, I don't see why not. He couldn't sing them. Of course, he simply doesn't have the range. But that's no reason he couldn't make them up. Why I suppose for bats a bat's poems would be ideal. The bat said sometimes when I wake up in the daytime, I make up poems. Could I I wonder whether I could say you one of my poems. A queer look came up with the mockingbird's face. But he said cordially. I'd be delighted to hear one. Go right ahead. He settled himself on his branch with a listening expression.

(14:29)

The bat said a shadow is floating through the moonlight. Its wings don't make a sound. Its claws are long, its beak is bright. Its eyes try all the corners of the night. It calls and calls. All the air swells and heeaves and washes up and down like water. The ear that listens to the owl believes in death. The bat beneath the eaves, the mouse beside the stone are still as death. The owl's air washes them like water. The owl goes back and forth inside the night and the night holds its breath.

(15:35)

When he'd finished his poem, the bat waited for the mockingbird to say something, he didn't know it but he was holding his breath. Why, I like it said the mockingbird, technically, it's quite accomplished. The way you change the rhyme schemes particularly effective. The bat said it is? Oh yes said the mockingbird, and it was clever of you to have that last line two feet short. The bat said blankly. Two feet short? It's two feet short said the mockingbird a little impatiently. The next to the last lines iambic pentameter and the last lines iambic trimeter. The bat looked so bewildered that the mockingbird said in a kind voice. An iambic foot has one weak syllable and one strong syllable. The weak one comes first. That last line of yours has six syllables and the one before it has 10. When you shorten the last line like that, it gets the effect of the night holding its breath. I didn't know that. The bat said. I just made it like holding your breath. To be sure, to be sure said the mockingbird. I enjoyed your poem very much. When you made up some more do come around and say me another. The bat said that he would and fluttered home to his rafter. Partly he felt very good. The mockingbird had liked his poem. And partly he felt just terrible. He thought, why, I might as well have said it to the bats. What do I care how many feet it has? The owl nearly kills me, and he says he likes the rhyme scheme. He hung there upside down thinking bitterly. After a while, he said to himself. The trouble is not making poems. The trouble is finding somebody that listened to them.

(17:37)

Before he went to sleep, he said is owl poem over to himself. And it seemed to him that it was exactly like the owl. The owl would like he thought. If only I could say it to the owl. And then he thought that's it. I can't say it to the owl. I don't dare get that near him. But if I made up a poem about the chipmunk, I could say it to the chipmunk. He'd be interested. The bat got so excited his fur stood up straight and he felt warm all over. He thought. I'll go to the chipmunk and say if you give me six crickets, I'll make a poem about you. Really, I do it for nothing. But they don't respect something if they get it for nothing. I'll say for six crickets. I'll do your portrait inverse.

(18:30)

The next day at twilight, the bat flew to the chipmunks hole. The chipmunk had dozens of holes, but the bat had noticed that there was one he liked best and always slept in. Before long the chipmunk ran up his cheeks bulging. Hello, said the bat. The instant he heard the bat, the chipmunk froze. Then he dived into his hole. Wait, wait, the bat cried. But the chipmunk had disappeared. Come back. The bat called. I won't hurt you. But he didn't talk for a long time before the chipmunk came back. And even then, he just stuck the tip of his nose out of the hole. The bat hardly knew how to begin. But he timidly said to the chipmunk, who listened timidly I've thought of making this offer to to the animals of the vicinity. You're the first one I've made it to. The chipmunk didn't say anything. The bat gulped and said quickly for only six crickets. I'll do your portrait in verse. The chipmunk said, what are crickets? The bat felt discouraged. I knew I might have to tell you about poems he thought. I never thought I'd have to tell him about crickets. He explained. They're little black things you see on the porch at night, by the light. They're awfully good. But that's alright about them, instead of crickets, you could give me Well, this time. You don't have to give me anything. It's an introductory offer. The chipmunk said in a friendly voice. I don't understand. I'll make you a poem about yourself. Said the bat. One just about you. He saw from the look in the chipmunk of eyes that the chipmunk didn't understand. The bat said, I'll say you a poem about the owl. And then you'll see what it's like. He said hia poem and the chipmunk listened intently. When the poem was over the chipmunk gave a big shiver and said, it's terrible. Just terrible. Is there really something like that at night? The bat said, if it weren't for that hole in the oak, he'd have gotten me. The chipmunk asid in a determined voice. I'm going to bed earlier. Sometimes when there are lots of nuts, I stay out till it's pretty dark. But believe me, I'm never going to again. The bat said it's a pleasure to say a poem to to such a responsive audience. Do you want me to start on the poem about you? The chipmunk said thoughtfully. I don't have enough hold. It'd be awfully easy to dig some more holes. Shall I start a poem about you? Asked the bat. Alright, said the chipmunk but could you put in lots of holes. The first thing in the morning I'm going to dig myself another.

(21:50)

I'll put in a lot the bat promised. Is there anything else you'd like to have in it? The chipmunk thought for a minute and said, well, nuts and seeds, those big fat seeds they have in the feeder. Alright, said the bat. Tomorrow afternoon, I'll be back or day after tomorrow. I don't really know how long it will take. He and the chipmunk said goodbye to each other. And he fluttered home to the porch. As soon as he got comfortably settled he started to work on the poem about the chipmunk. But somehow, he kept coming back to the poem about the owl. And what the chipmunk had said and how he looked. He didn't didn't say any of that two feet short stuff. The bat thought triumphantly, he was scared. The bat hung there upside down, trying to work on his new poem. He was happy. When at last he'd finished the poem. It took him longer than he thought. He went looking for the chipmunk. It was a bright afternoon, and the sun blazed in the bats eyes, so that everything looked blurred and golden. When he met the chipmunk hurrying down the path it ran past the old stump. He thought, what a beautiful color he is. Why the fur back by his tail's rosy, almost. And it was lovely black and white stripes on his back. Hello, he said. Hello, said the chipmunk. Is it done yet? All done. Said the bat happily. I'll say it to you. It's named the chipmunk's day. The chipmunk said in a pleased voice. My day. He sat there and listened while the bat said in and out the bushes up the ivy, into the hole by the old oak stump. The chipmunk flashes up the pole. To the feeder full of seeds, he dashes stuffs his cheeks, the chickadee and titmouse scold him down he streaks. Red as the leaves. The wind blows off the maple, red as a fox striped like a skunk. The chipmunk whistles past the love seat, past the mailbox, down the path, home to his warm hole stuffed with sweet things to eat. Neat and slight and shining, his front feet curled at his breast. He sits there while the sun stripes the red west. With its last light. The chipmunk dives to his rest.

(25:00)

When he finished the bat asked, Do you like it? For a moment the chipmunk didn't say anything. Then he said in a surprised, pleased voice. Say it again. The bat said it again. When he'd finished, the Chipmunk said, oh, it's nice. It all goes in and out, doesn't it? The bat was so pleased and he didn't know what to say. Am I really as red as that? Asked the chipmunk. Oh yes, the bat said. You put in the seeds in the hole and everything exclaimed the chipmunk. I didn't think you could. I thought you'd make me more like the owl. Then he said say me the one about the owl. The bat did. The chipmunk said it makes me shiver. Why do I like it if it makes me shiver? I don't know. I see why the owl would like it. But I don't see why we like it.

(26:08)

Who are you going to do now? Asked the chipmunk. The bat said I don't know. I haven't thought about anybody but you. Maybe I could do a bird. Why don't you do the cardinal? He's red and black like me and eat seeds at the feeder like me. You'd be in practice. The bat said doubtfully. I've watched him but I don't know him. I'll ask him said the chipmunk. I'll tell him what it's like then he's sure to want to. That's awfully nice of you said the bat. I'd love to do one about him. I like to watch him feed his babies. The next day while the bat was hanging from his rafter fast asleep. The chipmunk ran up the ivy to the porch and called to the bat. He wants you to. The bat stirred a little and blinked his eyes. And the chipmunk said the cardinal wants you to do. I had a hard time telling him what a poem was like but after I did he wanted you to. Alright, said the bat sleepily. I'll start it tonight. The chipmunk said what did you say I was red as? I don't mean a fox. I remember that. As maple leaves. As leaves the wind blows off the maple. Oh, yes. I remember now. The chipmunk said he ran off contentedly.

(27:40)

When the bat woke up that night, he thought. Now I'll begin on the cardinal. He thought about how red the cardinal was and how he sang and what he ate and how he fed his big brown babies. But somehow he couldn't get started. All the next day, he watched the cardinal. The bat hung from his rafter a few feet from the feeder. And whenever the cardinal came to the feeder, he'd stare at him and hope he'd get an idea. It was clear the way the cardinal cracked the sunflower seeds. Instead of standing on them and hammering them open like a titmouse. He turned them over and over in his beak. He gave him a thoughtful look. And all at once, the seed would fall open, split in two. While the cardinal was cracking the seed, his two babies stood underneath him on tiptoe, fluttering their wings and quivering all over their mouths wide open. They were a beautiful, soft, bright brown. Even their beaks were brown. And they were already as big as their father. Really, they were old enough to feed themselves and did whenever he wasn't there. But as long as he was there, they begged and begged till the father would fly down by one and stuff the seed in its mouth while the other quivered and cheeped as if it's heart were breaking. The father was such a beautiful clear, bright red with his tall crest, the wind rippled like fur, that it didn't seem right for him to be so harried and useful and hard working. It was like seeing a general in a red uniform, washing hundreds and hundreds of dishes. The babies followed him everywhere, and kept sticking their open mouths by his mouth. They shook all over him. They begged so hard, and he never got a bite for himself. But it was no matter. It was no use. No matter how much the bat watched. He never got an idea. Finally he went to the chipmunk and said in a perplexed voice

(30:00)

I can't make up a poem about the cardinal. The chipmunk said why just say what he's like, the way you did wwith the owl and me. I would if I could, the bat said, but I can't. I don't know why I can't, but I can't. I watch him and he's just beautiful. He'd make a beautiful poem. But I can't think of anything. That's queer, the chipmunk said. The bat said in a discouraged voice. I guess I can't make portraits of the animals after all. What a shame. Oh, well, the bat said it was just so I'd have somebody to see them to. Now that I've got you. I'm alright. When I get a good idea. I'll make a poem about it. And say it to you. I'll tell the cardinal you couldn't. The chipmunk said he won't be too disappointed. He never has heard a poem. I tried to tell him what they're like, but I don't think he really understood. He went off to tell the cardinal and the bat flew home. He felt relieved. It was wonderful not to have to worry about the cardinal anymore.

(31:18)

All morning the mockingbird had been chasing everything out of the yard. He gave you the feeling that having anything else in the world was more than he could bear. Finally, he flew up to the porch, sat on the arm of a chair and began to chirp in a loud, impatient, demanding way, until the lady who lived inside brought him out some raisins. He flew up to a branch, waited impatiently, and as soon as she was gone dived down on the raisins and ate up every one. Then he flew over to the willow and began to sing with all his might. The bat clung to his rafter, listening drowsily. Sometimes he would open his eyes a little in the sunlight and the shadows and the red and yellow and orange branches waving in the wind made a kind of blurred pattern so that he would blink and let his eyelids steal together and go contentedly back to sleep. When he woke up, it was almost dark. The sunlight was gone. And the red and yellow and orange leaves are all gray. But the mockingbird was still singing. The porch light was lit and there were already dozens of insects circling around. So the bat flew toward them. He felt hungry but comfortable. Just then, the mockingbird began to imitate a jay. Not the way a jay squawks or skulls. But the way he really sings in a deep, soft voice. As he listened the bat remembered how the mockingbird driven off two jays that morning. He thought it's queer the way he drives everything off and then imitated. You wouldn't think that. And at that instant, he had an idea for a poem. The insects were still flying around and around the light. The mockingbird was still imitating the jay but the bat didn't eat and he didn't listen. He flapped slowly and thoughtfully back to his rafter and began to work on the poem. When he finally finished it, he'd worked on it on and off for two nights. He flew off to find the chipmunk. I've got a new one. He said happily. What's it about? The mockingbird. The mockingbird! The chipmunk repeated. Say it to me. He was sitting up with his paws on his chest, looking intently at the bat. It was the way he always listened.

(34:26)

The bat said. Look one way and the sun is going down. Look the other and the moon is rising. The sparrows shadow's longer than the lawn the bats squeak. Night is here. The birds cheep day is gone.

(34:55)

On the willows highest branch monopolizing day and night cheeping, squeaking, soaring, the mockingbird is imitating life. All day, the mockingbird has owned the yard as a light first woke the world. The sparrows trooped onto the seedy lawn. The mockingbird chased them off shrieking hour by hour, fighting hard to make the world his own. He swooped on thrushes, thrashers, jays and chickadees. At noon, he drove away a big black cat. Now, in the moonlight, he sits here and sings. A thrush is singing then a thrasher, then a jay. Then, all at once a cat begins meowing. A mockingbird can sound like anything. He imitates the world he drove away. So well that for a minute in the moonlight which one's the mockingbird? Which one's the world? When he had finished, the chipmunk didn't say anything. The bat said uneasily. Did you like it? For a minute the chipmunk didn't answer him. Then he said it really is like him. You know he's chased me. And can he imitate me. You wouldn't think he drive you away and imitate you. You wouldn't think he could. The bat could see that what the chipmunk said meant that he liked the poem. But he couldn't keep from saying do you like it? The chipmunk said yes, I like it. But he won't like it. You liked the one about you the bat said. Yes, the chipmunk answered. But he won't like the one about him. The bat said it is like him. A Chipmunk said, just like, why don't you go say it to him? I'll go with you.

(37:36)

When they found the mockingbird, it was one of his good days. The bat told him that he had made up a new poem. Could I say it to you? He asked. He sounded timid. Guilty almost. To be sure, to be sure answered the mockingbird and put on his listening expression. The bat said it's a poem about well, about mockingbirds. The mockingbird repeated about mockingbirds. His face had changed, so that he had to look listening all over again. Then the bat repeated to the mockingbird. His poem about the mockingbird. The mockingbird listened intently, staring at the bat. The chipmunk listening intently, staring at the mockingbird. When the bat had finished, nobody said anything. Finally the chipmunk said did it take you long to make it up? Before the bat could answer the mockingbird exclaimed angrily. You sound as if there was something wrong with imitating things! Well, no, the bat said. Well, then you sound as if there was something wrong with driving them off. It's my territory, isn't it? If you can't drive things off your own territory, what can you do? The bat didn't know what to say. After a minute and chipmunks said uneasily. He just meant its odd to drive them off and then imitate them so well too. Odd! Cried the mockingbird. Odd if I didn't, it really would be odd. Did you ever hear of a mockingbird that didn't? The bat said politely No, indeed. No. It's just what mockingbirds do do. That's really why I made up the poem about it. I admire mockingbirds so much, you know. The chipmunk said he talks about them all the time. A mockingbird's sensitive, said the mockingbird. When he said sensitive, his voice went way up and way back down. They get on my nerves. You don't understand how much they get on my nerves. Sometimes if I think I can't get rid of them if I can't get rid of them, I'll go crazy. If they didn't get on your nerves so, maybe you wouldn't be able to imitate them so well. The chipmunk said in a helpful, hopeful voice. And the way they can sing! Cried the mockingbird 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3. The same thing. The same thing always the same old thing! If only they'd just once sing something different. The bat said yes, I can see how hard on you it must be. I meant for the poem to show that but I'm afraid I must not have done it right. You just haven't any idea. The mockingbird went on, his eyes flashing and his feathers standing up. Nobody but a mockingbird has any idea. The bat and the chipmunk were looking at the mockingbird with the same impressed, uneasy look. From then on they were very careful what they said. Mostly, they just listened while the mockingbird told them what it was like to be a mockingbird.

(41:17)

Toward the end he seemed considerably calmer and more cheerful and even told the bat he had enjoyed hearing his poem. The bat looked pleased and asked the mockingbird. Did you like the way I rhymed the first two lines of the stanzas and then didn't rhyme the last two? The mockingbird said shortly. I didn't notice. The chipmunk told the mockingbird how much he always enjoyed hearing the mockingbird sing. And a little bit later, the bat and the chipmunk told the mockingbird goodbye. When they had a left, the two of them looked at each other. And the bat said you were right. Yes, said the chipmunk. And he said I'm glad I'm not a mockingbird. I would like to be because of the poems the bat said.

(42:13)

But as long as I'm not, I'm glad I'm not. He thinks that he's different from everything else, the chipmunk said. And he is. The bat said, just as if he hadn't heard the chipmunk, I wish I could make up a poem about bats. The chipmunk asked why don't you? If I had one about bats, maybe I could say it to the bats. That's right. For weeks, he wished that he had the poem. He would hunt all night, and catch and eat hundreds and hundreds of gnats and moths and crickets. And all the time he would be thinking if only I could make up a poem about bats. One day he dreamed that it was done and that he was saying it to them. But when he woke up, all he could remember was the way it ended. At sunrise, suddenly, the porch was bats. A thousand bats were hanging from the rafter. It sounded wonderful in his dream. But now it just made him wish that the bats still slept on the porch. He felt cold and lonely. Two squirrels had climbed up in the feeder and were making the same queer noise, a kind of whistling growl to scare each other away. Somewhere on the other side of the house, the mockingbird was singing, the bat shut his eyes. For some reason, he began to think of the first things he could remember. Til a bat is two weeks old he's never alone. The little naked thing. He hasn't even any fur clings to his mother wherever she goes. After that, she leaves him at night. He and the other babies hang their sleeping, til at last their mothers come home to them. Sleepily, almost dreaming, the bat began to make up a poem about a mother and her baby.

(44:36)

It was easier than the other poems, somehow all he had to do was remember what it had been like and every once in a while, put in a rhyme. But easy as it was he kept getting tired and going to sleep and would forget parts and have to make them over. When at last he finished he went to say it to the chipmunk. The trees were all bare, and the wind blew the leaves past the chipmunks hole. It was cold. When the chipmunk stuck his head out it looked fatter than the bat had ever seen it. The chipmunk said in a slow, dazed voice it's all full. My hole's all full. Then he exclaimed surprisedly to the bat, how fat you are. I? The bat asked. I'm fat? Then he realized it was so for weeks, he'd been eating and eating and eating. He said, I've done my poem about the bat. It's about a mother and her baby. Say it to me.

(45:55)

The bat said. A bat is born, naked and blind and pale. His mother makes a pocket of her tail and catches him. He clings to her long fur by his thumbs and toes and teeth. And then the mother dances through the night. Doubling and looping, soaring, somersaulting. Her baby hangs on underneath. All night in happiness, she hunts and flies. Her high, sharp cries like shining needle points of sound. Go out into the night and echoing back. Tell her what they have touched. She hears how far it is, how big it is. Which way it's going. She lives by hearing. The mother eats the moths and gnats she catches in full flight. In full flight. The mother drinks the water of the pond she skims across. Her baby hangs on tight. Her baby drinks the milk she makes him in moonlight or starlight in midair. Their single shadow printed on the moon or fluttering across the stars whirls on all night. At daybreak, the tired mother flaps home to her rafter. The others all are there. They hang themselves up by their toes. They wrap themselves in their brown wings. Bunched upside down. They sleep in air. Their sharp ears. Their sharp teeth. Their quick, sharp faces are dull, and slow and mild. All the bright day as the mother sleeps. She falls her wings about her sleeping child.

(48:27)

When the bat had finished the chipmunk said it's all really so? Why of course the bat said. And you do all that too? If you shut your eyes and make a noise, you can hear it where I am and which way I'm going? Of course. The chipmunk shook his head and said wonderingly. You bats sleep all day and fly all night and see with your ears and sleep upside down and eat while you're flying and drink while you're flying. And turn somersaults in midair with your baby hanging on and and it's really queer. The bat said. Did you like the poem? Oh, of course. Except I forgot it was a poem. I just kept thinking how queer it must be to be a bat. The bat said. No. It's not queer. It's wonderful to fly all night. And when you sleep all day with the others it feels wonderful. The chipmunk yawned. The end of it made me feel all sleepy, he said, but I was already sleepy. I'm sleepy all the time now. The bat thought why I am too. He said to the chipmunk. Yes, it's winter, it's almost winter. You ought to say the poem to the other bats, the chipmunk said. They will like it. Just the way I like the one about me. Really? I'm sure of it. When it has all the things you do, you can't help liking it. Thank you so much for letting me say it to you, the bat said. I will say it to them. I'll go say to them now. Goodbye, said the chipmunk. I'll see you soon. Just as soon as I wake up, I'll see you. Goodbye the bat said. The chipmunk went back into his hole. It was strange to have him move so heavily and to see his quick face so slow.

(50:52)

The bat flew slowly off to the barn. In the west, over the gray hills, the sun was red. In a little while, the bats would wake up and he could say them the poem. High up under the roof in the farthest corner of the barn, the bats were hanging upside down, wrapped in their brown wings. Except for one, they were fast asleep. The one the little brown bat lighted by was asleep. When he felt someone light by him, he yawned and screwed his face up and snuggled closer to the others. As soon as he wakes up, I'll say it to him the bat thought. No, I'll wait till they're all awake. On the other side of him was the bat who was awake, that one gave a big yawn, snuggled closer to the others, and went back to sleep.

(52:01)

The bat said to himself sleepily, I wish I'd said we sleep all winter. That would have been a good thing to have in. He yawned. He thought it's almost dark, as soon as it's dark they'll wake up and I'll say them the poem. The chipmunk said they'd love it. He began to say the poem over to himself. He said, in a soft, contented whisper. A bat is born naked and blind and bail. His mother makes a pocket of her tail and catches him.

(52:50)

He clings he clings. He tried to think of what came next. But he couldn't remember. It was about fur, but he couldn't remember the words that went with it.

(53:06)

He went back to the beginning. He said, a bat is born. Naked and blind. But before he could get any further, he thought. I wish I'd said we sleep all winter. His eyes were closed. He yawned and screwed his face up and snuggled closer to the others.