[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Speaker 1 [0:45]

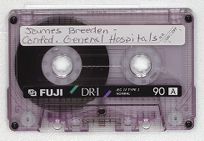

Dr. James Breeden as a member of our one of our speakers today, Dr. Breeden is professor of history at Southern Methodist University at Dallas. He's a Virginia man, and also trained at Tulane. And I don't know how he got down there in Texas and stayed there, but he's been there for a while and hasn't shown any signs of coming back up here where he belongs yet. We're very pleased to have him with us. Dr. Breeden has one of his specialtiesn one of his areas of study is Dr. Joseph Jones. And he has work organizing and assessing the state of medical practice and the Confederacy. And he's also today going to talk about the development of the hospital, the General Hospital. So we're very pleased to have Jim Breeden with us, I'd like you to welcome him this morning.

James Breeden [2:06]

Thank you. I'm in Texas because of something called a job. I came into the profession in the late 60s, when there were no jobs for liberal arts types. So I got a chance to go to Texas and there I went vowing I'd stay being a Virginia person staying on the godforsaken frontier no more than ten-twp years and be gone back to civilization. And by the time the job market got better or my research got the point I could move, kids family, you know, family house since now, I guess I'm there for the duration I am at SMU. I never bought a football player. We've gotten to the point that we can laugh about our football problems and look at some folks up this way now perhaps looks like the ACC is trying to join the southwestern conference and but our football crisis gave rise to some gallows humor. We were charged with buying players which we did. We were caused accused of giving them grades which we didn't. And then we were finally accused of of using coeds to recruit football players. And we have a, our largest major I guess it's the business school and we have a student entrepreneur came up with a marvelous idea. He made a small fortune selling T shirts that said get laid paid and a passing grade only at SMU.

James Breeden [3:55]

I am happy to be here and I mean that sincerely if you live in Texas, and have family in Virginia and have to fly inexpensively as my wife and I do. You flew Piedmont in the old days and US Air now. And you have to fly through Charlotte of course and for years I had seen that those commuter airline aircraft out there and always said you know there except for the grace of God, you know, well yesterday I got off the plane and was sent to that remind me of pterodactyl airlines or something. But actually which once you got on and got up it was actually very pleasant. So give him a white knuckle flyer again. You know, if I seem a bit ill at ease I am because my forte is the 20 to 25 undergraduates and on sort of a personal connection. I'm not a great formal lecturer but here it goes. My topic is the Confederate General Hospital. It like having Charles's papers, another state setting background sort of of study for the study for the more specific appointed papers that you will hear this afternoon. The topic is a very broad one, it lends itself to a variety of approaches. And looking at the program, what I thought might work the best for this for today, is to look at the General Hospital in two ways. First of all, an overview as to its evolution. And this is the Southern General Hospital, of course, look at its evolution and sort of an overview of it during the war. And then finally, to look at what practice what the practice in a in a in a Confederate General Hospital was like.

James Breeden [6:02]

And the heroes in my talk, are these guys here. The Confederate surgeon. If these aren't focused, you'll have to tell me because I can't see. But the the Confederate generals, the Confederate surgeon was placed in a situation of having to deal with a horrible situation that they did not that he or they did not make. So these are the true heroes and everything that we're going to be talking about today. And I like this picture because it purely a southern one in that one of these folks have brought their has brought his servant with him. At least for the picture taking. Disease, disability and death were constant companions of the Civil War soldier. Indeed, the human toll from this celebrated fratricidal conflict, is unequaled in American history. Combat claimed approximately 620,000 lives of these threatened 60,000 were union and 260,000 were Confederate additional 1000s, who died later from disease and injury incurred during the hostilities, push this figure incalculably higher. The Civil War's legacy of misery and death is especially evident in the southern experience for the Confederate medical officer not only share the shortcomings of mid 19th century medicine, but labored under the added burden of an inadequate medical staff, near crippling shortages of medicines, and medical stores, and a host of problems arising from a steadily worsening military situation. In recalling his practice, a member of the South medical service remarked as to methods I may say as a general statement, that we aim to conform to the science of the time, though the restrictions to which our ever increasing necessities subjected us often forbade the practice of it. We did not the best we would, but the best we could. The pitiful aspect of Confederate medicine a modern scholar of Civil War Medical History has written in agreement is that with all their limitations of knowledge, limitations common to the whole medical profession of the time, the army doctors could have saved so many more men, if only circumstances had not combined against them. A valuable lens for observing wartime southern medicine is the General Hospital, for it was the large fixed facility that offers the fullest picture, but the triumphs and tragedies of a Confederate practice. The organization of a hospital service was one of the most pressing problems that confront it Samuel P. Moore, the Surgeon General of the Confederacy, when he assumed his post in March 1861. And here's here's more. A particular urgency was the establishment of general hospitals to care for the sick and wounded evacuated from the camps, and battlefields. These were so named because admissions were not limited to the troops of particular units or states. Confusion dominated the early scene, the South short war mentality and the monopolizing demands of military mobilization caused the Confederate authorities to reject an extensive plan of hospital mobilization or hospital accommodations, according to more as wholly unnecessary. Predictably, the ensuing epidemics of so called Camp diseases, largely outbreaks of such childhood disorders as measles, mumps and chickenpox and the heavy casualties from the opening campaigns nearly overwhelmed the nascent Confederate medical service. Wounded from the battle of first Manassas, for example, streamed into Richmond. Within two weeks, there were 4000 patients to be cared for. There were a hospital accommodations for only a fraction of this number, forcing the medical department to scramble to find space for the rest. Warehouses, hotels, churches, courthouses, stores, barns, and private homes were converted into temporary hospitals. There was an English observer wrote hardly a gentleman and are about Richmond, who had not from from one to four patients in his house. The scene in the remote West was even more chaotic. Samuel H. Stout, later Medical Director of the Hospitals of the Army of Tennessee was greeted by a shocking situation upon his arrival at Nashville's Gordon Hospital in October 1861. When I entered the hospital to take charge of it, he later wrote, I found no organization, no register, and no books of any kind required by the regulations. But I found there lying upon the bunks and floors, he continued 650 patients, most of them suffering from measles, or the sequela there of, many of them seriously. The hospital was located in a poorly ventilated warehouse. Before Stout's appointment it was under the supervision of a committee of women hospital volunteers, which called in civilian positions to treat the sick. Ella K. Newsom, called the Florence Nightingale of the Southern Army reported similar conditions in the hospitals of Bowling Green, Kentucky. The Confederacy's hospital problem sparked a concerted effort to construct suitable facilities. The Pavilion Plan suggested by British hospital design in the Crimean War was adopted and improved upon by [Moore]. A central feature was separate buildings measuring 100 feet by 30 feet and one story in construction. Each of these huts as they were sometimes called was according to [Moore] to be a ward and separate of undress plank set upright, calculated for 32 beds, with streets running each way, say 30 feet wide. From 15 to 20 of such wards constituted a division three or more divisions making a general hospital. Subsequent hospital construction confer conformed to this plan. By the end of 1861, five of these general hospitals had been constructed in the suburbs of Richmond, each could accommodate roughly 20,000 patients at a time. Moreover, their ward concept allowed the segregation of the sick and wounded. Here's a picture of a Civil War General Hospital and this is a Union Hospital you can tell by the flag. But in general, this is sort of what the pavilion design looked at with the two rows of bunks spread the length of the building. [Moore] was pleased with these facilities and the temporary ones with the exception of the largest warehouses and factories were gradually abandoned. Sadly, however, the construction of hospitals in the Confederacy owing in large part to the Confederate bureaucracy and red tape, principally the requirement that the medical department depend upon the quartermaster and commissary departments to erect and furnish them failed to keep pace with the ever growing need. The Seven Days campaign, despite an improved picture, By the spring of 1862 underscored the persistence of earlier problems. Casualties inundated the hospitals of Richmond. Like a year earlier, every hospital was quickly filled overcapacity and the sick and wounded spilled into warehouses, hotels and homes. Matters in the West also remain confused. Casualties from the Battle of Shiloh and April, for example, severely tested the makeshift hospitals of the retreating army of Tennessee. Kate Cumming the celebrated nurse perhaps best captured the magnitude of the suffering and the insufficient means to mitigate it. The men she recorded in her diary at Corinth, Mississippi, are lying all over the house, on their blankets just as they were brought in from the battlefield. They are in the hall on the gallery and crowded into various small rooms. The foul air from this mass of human beings at first made me giddy and sick, but I soon got over it. We have to walk and when we give the men anything, kneel and blood and water, but we think nothing of it at all.

James Breeden [14:52]

But two months later, in Okolona, the continued suffering of the sick and wounded had noticeably eroded Cumming's cheerfulness. If our government cannot do better by the men who are suffering so much She asserted, I think we had better give up at once. Tragically much time was to pass before there was any significant easing of the plight of the casualties in the West. Overall Overall, however, by the winter of 1862-63, important progress was noticeable in the organization of a system of general hospitals. More and better facilities were evident. The myriad of small hospitals those with the capacity of less than 100 patients were gradually closed as these new ones came online. The War Department exhibited a growing appreciation for the medical department, hospital appropriations had grown and supported even farsighted legislation was adopted by the Confederate Congress. These advances were most noticeable in Richmond, the Chief Medical Center of the Confederacy. Under the watchful eye of [Moore], the hospitals here were impressive for their construction, capacity and overall management. In the east, a historian of Confederate medicine asserted the effort after every campaign was to get the severely wounded quickly to Richmond, if possible, where they would receive the best care and the best equipped and most permanent of the Surgeon General's organizations. The largest of Richmond's general hospitals and the most famous in the Confederacy was Chimborazo. And is Chimborazo here and you can see the hospitals are at the Pavilion construction. Name for the hikes overlooking the James that had occupied this hospital opened on October the 11th 1861. It was ideally located with an abundance of good water and an excellent drainage, the largest military hospital in American history to that time, Chimborazo constituted, consisted of 150 well ventilated pavilion tight buildings, with an 8000 bed capacity, convalescence, were assigned to pitch tents to tents pitched on the surrounding slopes. The facility was under the command of Dr. James B. McCaw. His medical staff consists of approximately 50 surgeons to apothecaries and 45 hospital matrons designated an independent Army post by the Secretary of War, Chimborazo was largely self sufficient. It had five ice houses, a Russian bathhouse, to five soup kitchens, a bakery with a data capacity of 10,000 loaves of bread, and a large brewery, hundreds of head of livestock, and large numbers of poultry were kept on a neighboring plantation and a hospital operated trading boat by the James River in the Kanawha Canal as far as Lynchburg and Lexington bartering for provisions. Chimborazo remained in continuous operation until the evacuation of Richmond in April 1865. During its three and a half year history, this hospital treated approximately 78,000 patients. Deaths numbered 7000 are slightly more than 9%, which for this time was a very good rate. Chimborazo is principal union counterpart Lincoln Hospital in Washington DC served 46,000 patients. The mainstay of the Confederate General Hospital System in the West was Samuel H. Stout. Stout it will be recalled began his Confederate medical service as a surgeon and surgeon in charge of Nashville's Gordon Hospital in the fall of 1861. The following spring, he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the hospitals in Chattanooga, and instructed to clean them up, Stout found on a larger scale, the problems that he had encountered in Nashville, and again, he demonstrated his administrative ability. Existing facilities were cleansed and reorganized and new ones were built. Stout was especially proud of his pavilion type buildings, claiming that they were far superior to those erected in Richmond. Under the Surgeon General Supervision. He claimed that his were less crowded and had better ventilation. In June 1862, Braxton Bragg was named commander of the Army of Tennessee. Bragg was so impressed with Stout's hospitals that within a month of taking command, he placed him in charge of its hospitals. Stout entered upon his new and demanding duties with a single goal to which he was undoubtably resolved. It was determined he wrote to manage the general hospitals as fully as was in my power and in the interest in care of the sick and wounded, and to so discipline every officer, soldier, detail man, matron and hireling, that each having his duty assigned him should in his position, meet the responsibilities pertaining there to in the most efficient way. So successful was Stout that his administrative organization and system of hospitals remained intact until the very end of the war. At the heart of Stout's success was his long cherished scheme of mobile, general hospitals. Endorsed by Bragg and later commanders of the Army of Tennessee, it was an administrative gym, and a godsend to Confederate casualties. One of the first things Stout did was to end the practice of special hospitals for commands and states of practice that had held on the system of the great brigade division and core hospitals, he asserted, is practicable in time of peace, but utterly impractical during an active war. So to the principle of states rights, though a good political doctrine could rationally find no apology for what's enforcement or application in the control or movement of armies in times of war, or after battles. Subsequently, the assignment of a patient to a hospital was determined by his ability to bear transportation, and the number of empty bunks at each hospital. Selecting hospital sites was one of Stout's most crucial duties, and great care went into this process. Stout instructed medical officers sent out direct order locations that the hospitals be situated and elevate, on elevated, well watered sites contiguous to a railroad, and agriculturally productive strongly pro southern areas. Moreover, at every town or locality in which hospitals were established, Stout saw to it that a post commander, quartermaster and commissary were appointed to ensure order and to provide supplies and subsistence. Finally, Stout insisted on complete loyalty and commitment from his subordinates. The good of the service as he put it, took precedence over all else because of his personal example and even handed in an administration. A generous and intelligent rivalry Stout noted with pride sprung up among the medical officers early during his tenure as to who could show the best managed hospitals and the best cared for best fed and most contented and grateful sick and wounded soldiers and in the department, he also won the unbridled praise of his medical and military superiors in the Army of Tennessee. Performance during combat was of course the measure of the effectiveness of Stout's plan. The hospital service was informed when the battle was imminent, and timely preparations were made. The hospital Stout wrote, were move forward and the rear of the army and retreated before it as exigency required. The Atlanta campaign stretching from May to September 1864 was the acid test of his hospitals. They passed, impressively. Operating under seemingly insurmountable disadvantages and obstacles, such things as Sherman's unrelenting pressure, a collapsing southern transportation system, the constant shifting of hospitals to escape the advancing Union Army, mounting numbers of sick and wounded and severe shortages of medicines in hospitals stores, Stout's organization, delivered uninterrupted and effective medical services throughout this disastrous campaign. Stout attributed this feat to the mobility of his hospitals. Ironically, Stout's moment of triumph the Atlanta campaign is considered the death nail of the Southern Confederacy. The end actually began with the opening of the military campaign of 1864 and the east the bloody battles of the wilderness, Spotsylvania courthouse and Cold Harbor within a 30 day period, put immense pressure on the general hospital system. Had the hostilities been between Lee and Grant not stalemated at Petersburg in mid June, it may have floundered, as it were the hospital emergency had passed by late July, and crowding in the Richmond hospitals eased. Subsequently, the hospital picture stabilized in East stabilized and remained relatively unchanged until the fall of the Confederate capitol.

James Breeden [24:44]

In the West, however, the situation remained highly fluid here, harried but resolute medical officers were trying valiantly to cope with a hopelessly deteriorating military situation, as Sherman moved north through the Carolinas to link up with Grant. Their devotion and resourcefulness are well captured in the experience of young Simon Baruch, a graduate of the Medical College of Virginia in 1862. Baruch had in February 1865 been reassigned from field hospital duty to General Hospital service in North Carolina. The next month while stationed at Thomasville he was instructed to prepare hospital accommodations for 280 casualties from the battle of was it at [Averasboro], I asked for the pronunciation and promptly forgot it. One of the futile attempts to slow show Sherman's to slow Sherman's march northwood, Baruch recalled, neatly set out, sit out and arm guard to bring all the men and large boys to headquarters. And press them with the fact that they must assist me in madness necessity, necessarily hasty preparations, I commandeer two wagons, but two men on each sent one together pine straw, the other together pine nuts, I commandeered a large number of girls from a female college to fill the straw sacks I had with pine straw, and lay them neatly on the floor of the buildings I had prepared. I went personally from house to house and obtained assistance from the women in baking bread, and preparing rye coffee and bacon for the expected wounded. Next I had piles of pine nuts placed in front of the buildings, which when light it illuminated the town so that when the train arrived, the wounded could be comfortably unloaded into the factories, and to churches. Two surgeons, he continued, came with the wounded in the most piteous plight, lying upon loose cotton direct from the battlefield, did not retire until every man was fed, who would eat and all were as comfortable as possible. After two hours sleep I proceeded to organize the hospital, operated all day and far into the night. On the following day, my head began to throb like a sledge hammer, dictated a telegram to medical director Hines to send someone to take my place and lapsed into unconsciousness from which did not rise for two weeks, during which time during which I read under typhoid fever. When I awoke from the prostration. I learned that during my illness, Stoneman had passed through and paroled all all Confederates and that Lee had surrendered. The crucial role of the General Hospital in the southern war effort is further underscored by an examination of Confederate hospital practice. Historically, disease has been a greater threat to armies than battlefield wounds. The Civil War was no exception. Surgeon Joseph Jones, a leading authority on medical conditions in the large Confederate armies, general hospitals and prisons asserted the victors of disease exceed tenfold bows of the sword. That was Joseph Jones. There were approximately 4 million cases of sickness reported in the Confederate army. Put another way, every southern soldier was taken sick on average of four times. Many of these cases especially those of an acute or chronic nature, were treated in the large general hospitals. At the outset of the hostilities, the principal source or source of disability was the aforementioned camp diseases that this was the case is not surprising. A large majority of the Confederate soldiers being from rural and upcountry districts Surgeon General Moore wrote, had never had the different contagious diseases to which residents of the more populous districts are exposed, especially scarlet fever and measles. Few had been vaccinated. They would therefore in all probability, contract these diseases, thus swelling the sick list, it was not uncommon for entire units to be incapacitated by outbreaks of children's diseases. When Stout reported through his first assignment with third Tennessee regiment in May 1861. He found almost half of the 1100 man command, mostly made up of use, stricken with measles. And in September 1861 Howell Cobb 16th Regiment of Georgia Infantry was so so badly ravaged by mumps and measles in its Richmond encampment that the unit was delayed for five weeks in moving to the peninsula. The most dangerous of these disorders was smallpox. The Army of Northern Virginia was especially hard hit an epidemic following up on the heels of the Antietam campaign crowded Virginia hospitals and took many lives. A second epidemic swept through the Army of Northern Virginia during the winter of 1863-64 and again, the disease exacted a heavy toll from October the first 1862 to January the 31st 1864, a period embracing both epidemics, Virginia's General Hospital's treated 2513 smallpox cases with 1020 deaths. Medical authorities tried to stem the threat of smallpox in various ways, including compulsory vaccination, the restriction of soldiers to camp and infected areas, a 15 day quarantine for sick and wounded during outbreaks of the disease, and the treatment of those stricken with smallpox in special hospitals or remote buildings and tents. As the war progressed, typhoid fever and malaria and diarrhea and dysentery became the great causes of morbidity among Confederate troops. Typhoid fever, the long standing scourge of armies struck hard during the first years of the conflict, Jones estimated that it was responsible for at least 1/4 of the Confederate fatalities between January the first 1862 and August the first 1863. During the 13 months, January 1862, to February 1863, there were over 6000 cases of this much feared killer, with 1600 deaths in the Virginia general hospitals outside of Richmond, over 40% of the 2100 cases treated at Chimborazo died. This shockingly high mortality rate is probably owing to the practice of transferring the most serious cases to the general hospitals whenever practical. Like children's diseases, typhoid usually affects an individual but once during life, and as Jones pointed out, it progressively diminished during the progress of the war, and disappeared almost entirely from the veteran armies. The history of the disorder in the Charlottesville General Hospital, one of Virginia's principal Confederate hospitals, is an instructive case in point, some 1300 cases and a little over 300 deaths during the period July 1861, to August 1863. were attributed to typhoid fever, as compared with 132 cases and 45 deaths during the month September 1863 to February 1865. Malaria long, endemic and often epidemic in the southern states was a persistent medical problem in the large Confederate armies. It accounted for one in every seven cases of disease among Confederate troops east of the Mississippi from 1861 to 1862. The Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida seemingly bore the brunt of this biological onslaught. Between October 1862 and December 1863, the 878 officers and men manning a Confederate battery below Savannah reported 3313 cases of malaria. And approximately 27% of all admissions to the Charleston hospital were listed under one of the many names given the disease. Despite its prevalence, malaria calls relatively relatively few deaths. This is probably attributable to the likelihood of some degree of immunity. The region's long history with the disease had bestowed and the use of quinine when available as a specific and prophylactic to control it. Diarrhea and dysentery were the great innervating ailments of the Civil War, chronic diarrhea and dysentery, Jones hailed were the most abundant and most difficult to cure amongst army diseases. And whilst the more fatal diseases as typhoid fever progressively diminished, chronic diarrhea and dysentery progressively increased, and not only destroyed more soldiers than gunshot wounds, but more soldiers were permanently disabled and loss from to the service from these diseases than from the disability following the accidents of battle.

James Breeden [34:19]

One knowledgeable Confederate surgeon held that nine tenths of all recruits had diarrhea, and that it was the source of considerable disability. Diarrhea and dysentery accounted for almost 1/4 of the cases of disease reported from the field and the Confederate forces east of the Mississippi during the first two years of the war. Since few of his victims were sent to the hospital, it is highly telling that diarrhea was the most common disease at Chimborazo, between October 1861 and November 1863. For example, there were 6300 admissions for this condition over a longer period. Diarrhea and dysentery were also the principal source of morbidity in the Charlottesville General Hospital, where they were responsible for approximately 10% of the total cases treated. The treatment of trauma made up much of the practice in the Confederate general hospitals. Most cases of injury were the result of combat related wounds. The nor the number of Northern wounded are said to range from roughly 275,000 to 400,000. Similar figures for the South are not available, but a conservative estimate of at least one half of the Union figures seems reasonable. The largest number the large number of battlefield casualties persistently plagued the Confederacy's hospital system. The whole country from annacis junction to Richmond in one direction and to Lynchburg and another, a Charlottesville general hospital surgeon remarked after the Battle of first Manassas was one vast hospital filled to replenish and with the second one at a border guards victorious army. A year later, another surgeon who witnessed the flood of casualties descend on Richmond from Malvern Hill, the last of the seven days battle of the peninsula campaign wrote, they came pouring into the hospitals by wagon loads. Battlefield, casualties presented a wide spectrum of injury. In general, the injuries fell into three broad categories, severe flesh wounds, broken bones, and penetration of vital organs. The authoritative manual of military surgery surgery prepared by order of the Surgeon General 1863. This is the Southern Surgeon General in 1863, provides informative statistics on the location of wounds among Confederate casualties. Chest wounds, which often prove fatal due to the probability of hemorrhage and infection accounted for 19% of battlefield casualties. Head and Neck wounds made up 12% of the total, but it was a injuries of the extremities, an estimated 65% of the wounded that dominated casualty lists. Bullets were naturally the cause of civil war casualties. Approximately 94,000 Confederates and 110,000 Federales died from gunshot wounds. The overwhelming majority of these injuries were inflicted by the Claude-Etienne Minie ball. The destructiveness of this bullet was a result of its low velocity which caused it to tumble and flatten on impact, producing a savage bursting wound on exit. The shattering splintering and splitting of a long bone by the impact of a minie ball, one surgeon graphically asserted was in many instances, both remarkable and frightening. Here, this is from the medical and surgical history of the waterbay. And here are some types of many balls. And here's what happens to them upon impact, soft lead they tend to a low velocity they tend to flatten out producing this sort of wound. This is not from real life, but a drawing from medical surgical memoirs, surgical history. And here's a long bone splintered by a minie ball. Early experience taught surgeons that amputation of the injured limb was the only means of saving life. Such empirical observation seemed to reinforce the findings of the British surgeons in the Crimean War, where it had been concluded that under existing methods of treatment, the wounding of any joint or the shattering of a long bone by gunshot usually proved fatal. Consequently, in the early days of the war amputation for both and the sooner the better, became the rule of thumb. As the war went as war war on However, further observation was to lead to a conservative reaction against primary amputation, making this question one of the conflicts most hotly debated subjects. In any case, 1000s of Civil War soldiers suffered indescribable agony and risked death from secondary infection from this practice, F. E. Daniel, who served in the General Hospital's of the army of Tennessee movingly described the ordeal of amputation. I see a strong man stretch prone on the table. I see the apron surgeons stern of visage kind and gentle of heart. I see the claim of a long knife. I see the warm life blood spurt out as it cleaves the quivering white flesh. I hear the grading of the saw as it cuts its way through the bleeding bone. I see the ghastly wound gaping gory is flabby flap weeping crimson tears, the thirstiest sponge drinks them eagerly, they are quickly dried, close stitched and a rule of bandage is turned around to stop it. Actual cases are not less gory. Such drastic practices on so larger scale move one historian of Civil War Medicine to characterize much of its surgery as resembling actual butchery. The well known shortage and at times absence of anesthetics compounded the operating table. Here's a Confederate manual of surgery Chisolm's, [J.J.] Chisolm's well known manual surgery used widely in the Confederacy. This is a two pages from Chisolm demonstrating what the amputation part of the foot. Here's a typical amputation kit for cutting down on will tell you a lot more about this afternoon. Here's a picture of that of an amputation. It's hard to see here, this is a northern slide scene.

James Breeden [41:18]

And here are the results of the surgeons art pile of amputated legs. But the horrors of amputation aside, Civil War surgery of all types is often followed by dangerous and frequently fatal secondary infections. So Civil War George W. Adams, the leading student of civil war medicine has written was fought in the very last years of the medical Middle Ages. While the guns were firing throughout the south pasture was laying the groundwork for bacteriology. And within two years after the surrender of Lee, Lister was beginning the application of his aseptic method, and the meantime the old and tragic practices continued to prevail. According to Adams, the surgeons of the day were still in a period of laudable pus. They believed that symptoms that's pardon me, they believed that supparation was a normal and necessary part of the mechanism of tissue repair, and were astonished when a few cases of wounds heal without it. They thought a bear finger was the best probe. They operated in dirty uniforms. They use the same marine sponge to swob out the wounds of countless men. They reused linen dressings, they metal with wounds and thus made bad matters worse. If a knife dropped to the floor during an operation, they would pick it up, rinse it in tap water and continue the operation. Far from being surprised at their large mortalities. Adams concluded we should marveled at a majority of their operation cases recovered. The principal surgical fevers as the secondary infections were called were as simple as anemia and gangrene. Although serious hazards and all Confederate General Hospital's their true impact is impossible to assess for two principle reasons. None of these conditions were found in the Confederate table of diseases before the middle of 1864. And in many instances when a secondary infection supervene No change was made in diagnosis. It was common, for example, for deaths from gangrene almost always supervening an origin to appear on the hospital records as due to gunshot wounds. Gangrene was the most dangerous of the supervening infections, and it became one of the Civil War's most serious medical problems. Jones found what he considered to be the Confederacy's first cases among the medical records for Stonewall Jackson's wounded, who retreated in the Charlottesville General Hospital, following the Battle of Port Republic, Virginia in June 1862. Thereafter, this disease progressively increased, although no case was officially recorded until July 1863, more than a year after its initial appearance. Here's a picture of a gangrenous leg from Jones's own research in the original This is in living color. So it loses a lot in black and white, but gives you some idea of what it looked like then. The Confederacy's lack of sufficient number of ambulances to evacuate casualties on the battlefield and it's inadequate, and as the war progress deteriorating transportation system further complicate the practice of surgeons in the general in a Confederate general hospitals. Long delays in transporting the wounded from the front and credit where railway cars drastically lessen chances of survival. Perhaps the most, perhaps the worst incident of its kind involved casualties from the battle of Chickamauga and investigating a gangrene epidemic in the fall of 1863 among the wounded from this engagement sent to Augusta for treatment. Jones found that the injured did not arrive until eight to 10 days after receiving their wounds. They were transported from the scene of the engagement in northwestern Georgia, some 300 miles away in filthy, crowded real railroad cars. Upon arrival, they had been left unattended in the railroad station for another 40 to 80 hours. Because the Augusta General Hospital in the various regimental hospitals could accommodate only a few of this large number of casualties without serious overcrowding and majority of the injuries were slight wounds of the extremities and should've pose no serious health hazard. But as a result of poor treatment on the battlefield the torturous journey to Augusta, the neglect upon arrival, and the crowding and poor sanitary conditions in the hospitals, gangrene became rampant. Only rarely did the surgeon in the Confederate General Hospital had the means necessary to perform his duties to his full professional and personal satisfaction. His problems were indeed legion, and seriously threatened his effectiveness. The most basic of these was a chronic and extreme shortage of trained physicians. Each General Hospital was authorized a surgeon in charge and one medical officer or contract that is civilian physician for every 70 or 80 patients. From the outset of the hostilities, this was seldom the case. As early as the summer of 1862, the head of a Petersburg Virginia General Hospital reported that he and a single assistant were caring for 400 patients. Contemporaneously, the director of the savannah Medical College Hospital complain the weather is hot. Physicians are scarce. There is considerable sickness and I am overworked. A major obstacle was the fiery patriotism of the South doctors, many of whom, like Joseph Jones, initially put aside their professional training for active duty. Ultimately, an estimated 3400 physician served in the Confederate medical service its Union counterpart enrolled 11,700 or approximately one doctor for every 133 Northern soldiers, and one for every three out and 24 southern ones. There was also a near crippling shortage of medical supplies of all types, medicines, instruments, and textbooks. This problem was needlessly exacerbated by the inhumane decision of the North to place medical stores on the contraband list. Even when needed items were even when needed items were were unavailable, the woefully inadequate southern transportation system and Confederate logistics the woefully inadequate southern transportation system and Confederate logistics made them virtually inaccessible. Therefore, in most cases, Southern surgeons, even those in the large general hospitals were forced to find substitutes, or do without the southern surgeons meager supply of essential medicines and instruments made him in the words of Hunter McGuire, one of the Confederacy's leading medical officers fertile in experience of every kind. He elaborated. I had seen him search field and forest for plants and flowers whose medicinal virtues he understood and could use the plient bark of a tree made for him a good tourniquet, the juice of the green persimmon a styptic. A knitting needle with its point sharp at bend of [ernakulam], a pin knife in his hand a scalpel in [inaudible]. I have seen him break off one prong of a common table fall fork, bend the point of the other prong.

James Breeden [49:08]

Bend the point of the other prong and with it elevate the bone and depress fracture the skull and save life long before he knew the use of the porcelain tip probe for finding bullets. I had seen him use a piece of soft pine wood and bring it out of the wound marked by the leaden ball. Food shortages gave rise to hospital vegetable farms worked by convalescence other edibles such as chickens, milk, butter, eggs, fruit and molasses, were either purchased with hospital funds, or bartered for. The constant shifting of hospitals in order to escape the invading Union armies and to treat the sick and wounded in each new sector posed additional problems. These moves not only necessitate the abandonment of many excellent hospitals sites as the borders of the Confederacy was steadily pushed inward, but also saw the loss of much valuable and irreplaceable equipment and quantities of medical stores. Even worse, perhaps such force moves reduced the quality of medical services and made the maintenance of hygiene and hospitals impossible. And the inevitable result was an increase in the disease rate in general, and better the to supply the sick and wounded according to the leading authority on Confederate medicine, with satisfactory hospital accommodations, this was no mean accomplishment. Indeed, all things considered. The surgeon in the General Hospital, like the Southern Medical Department in general performed his duties as another prominent student of medicine. In the war town south put it with a success seldom unequal. Thank you.