[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

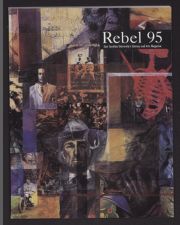

's Literary and Arts Magazine -

ly

iversi

East Carolina Un

hy 4

i

"

* &,

ART DIRECTION

Alana Solomon

David Rose

Jonathan Peedin

DESIGN ADVISOR

Craig Malmrose

ILLUSTRATION DIRECTION

Paul Rustand

LITERARY EDITOR

Randall Martoccia

LITERARY STAFF

Jahmon Reed

Stephen Randolph

COPY ASSISTANT

Valentina Kushnarenko

LITERARY JUDGES

Patsy OT Leary

Cindy Thompson-Rumple

LITERARY ADVISORS

Dr. Michael Bassman

Dr. Patricia Campbell

Julie Fay

ART JUDGES

Sheila Kilpatrick

Charlotte Beloate

Jennifer Strickland

EXHIBITION ADVISOR

Roxanne Reep

PHOTOGRAPHER

Henry Stindt

Stindt Studio

PRINTING

Morgan Printers, Inc.

Rebel Ninety-Five

/

Special Thanks:

Paul Wright

Craig Malmrose

Randall Martoccia

Dr. & Mrs. Martoccia

Ken Humphries

Mr. & Mrs. Alexander

Yvonne Moye

Janet Respess

Lynn Jobes

Luke Sanders

J. E. Boyette

Steve Randolph

Ray Elmore

Paul Hartley

Danny Stillion

Henry Stindt and his assistants

The Rebel is published for and by the

students of East Carolina University.

Offices are located in the Student

Publications Building on the campus of

ECU. This issue is volume 37, and its

contents are copyrighted © 1995 The

Rebel. All rights revert to the original

authors and artists upon publication.

Contents may not be reproduced without

written permission of the creators. The

Rebel invites all students and faculty to

voice opinions in writing.

Cover illustration:

David K. Rose and Jonathan Peedin

Literary and Arts

Special Notes:

| thank God for sending me a miracle named

David Rose and Jonathan Peedin. Without

their spirit of confidence, unselfishness,

enthusiasm, and endless dedication, this

magazine would never have been possible. 1

thank both of them from the bottom of my heart.

l also thank Craig Mal/mrose for never letting

me break, even through the most adverse

circumstances. His constant faith and endless

support will never be surpassed. Thank you

mother for your prayers and encouragement.

! love you. Thank you Paul Wright, for never

loosing faith in the Rebel Staff of 1995.

Alana Solomon

Philippians 1:3

| owe thanks to my mother and father for

bringing me into this world. I would like

to thank Ms. Wincer omom� Best, you

have had a greater impact on my life than

you will ever know. With your help, love,

and patience, my lifetime hopes and

dreams are being fulfilled. Thank you

Tony for the stress relieving chess Lames.

Thank you David and Alana for sharing

this with me. We have struggled together,

and in doing so we have enriched each

other's lives. Thank you Craig for your

confidence and trust in us. Your support

and encouragement as always, was

inspiring. And a special thank you to Miss

Tracey Fuller, the purity of your love and

faith, gave me the strength to push myself

harder, and make myself stronger than

ever before.

Jonathan Peedin

Sl would like to thank Jonathan and Alana

for sharing this experience with me. I would

like to thank Craig for always being there

when we needed him and Paul Wright for

his trust and support. Thanks to Randall

and his parents for helping us out of a bind.

And a special thanks to my family for

always having faith in me and Amanda for

her endless love and encouragement.

5s

David Rose

~Table of Contents

4

6

2(

~~

2?

,

Wh

Do

Wo

P

~1

36

Jl )

S2

90

Y6

Seeing is Believing Gregory Dickens

3rd Place Poetry / Narrative

A Pretty Good Bike Johnny Dale

Ist Place Fiction

Untitled Major 1. Hooper

3rd Place Poetry / Free Verse

Chosen Alfa Alexander

Ist Place Creative Nonfiction

She Comes Back for a Day Wayne Robbins

2nd Place Poetry / Narrative

Visitors Herman Schroeder

Honorable Mention Fiction

Incident in the Grocery Wayne Robbins

Honorable Mention Poetry / Narrative

Mamo- Toto Lion Laura McKay

2nd Place ChildrenTs Literature

About Russia from a Russian Lucy Spiryakova

EditorTs Choice Creative Nonfiction

Fran Andy Brown

2nd Place Fiction

Art Gallery

Printmaking

Photography

Metals

Wood

[Illustration

Drawing

Graphic Design

Painting

Best in Show

Sculpture

Textiles

Ceramics

My Grandmother Jo Avram Klein

3rd Place Creative Nonfiction

The Latchkey Blues Player Laura Wright

2nd Place Poetry / Free Verse

The Dinner Engagement Andy Brown

3rd Place Fiction

Johnny Cashes in on American Recordings Gregory Dickens

2nd Place Creative Nonfiction

Interview with Luke Whisnant Jon Hey/

Interview

Bob Laura Wright

2nd Place Poetry / Free Verse

Corn & Circumstance Jon Hey/

Fiction Honorable Mention

Pomegranates James Earl Casey

Ist Place Poetry / Free Verse

The Live Oak Randall Martoccia

Ist Place ChildrenTs Literature

Rebel Ninety-Five

I

. "

aie - a . a ee ee c eh Mle

a ee ARES Sab NS a oe tw a om snl 8 i ASE Vo PRB Si, REGO Sei a esos ere Se nT T - ~ . : :

oth SEM eee _ - -

' Sete:

seeing Is Believing

7. ufevers Direkews

" by Paul Rustand

| was born with eyes like babies.

If not minded, they would

wander into a corner

To sit for awhile and

release water.

Not all eyes do this.

| was told they needed

to be ocorrected� for

their instincts.

| couldn't disagree.

(They gave me distinction. | could see around corners.

ThatTs neat when you're three.)

They were invaded by metal and sewing thread.

Giants in masks played with my children.

And | woke up blind for days.

(They were frightened. They hid from their father.)

When they awoke, they were as brazen as ever,

My parents,

(The meddling grandparents that they were),

Put them in cages, many over the years.

Frames like wheelbarrows, glass like lead.

They locked my children away.

And they've been there for decades.

| wonder if what my children see is what's really there.

| love them, I'd hate to think of them lying to me.

Sore at their incarceration, blaming me

(like blaming Atlas for the weight of the world).

I'm a stymied parent,

My children are ungrateful for their corrections.

ITm atraid we'll become older, and they wonTt talk to me at all.

| won't know what they see, where they wander,

I'll be in the dark.

Abandoned by my roaming and offended children.

4 Literary and Arts

: " Ere MCRES Sea ER eT

ne hae a

PAW SAY W/E, VEOEICEELA oFW. UL VU AALILINIG Sr Wow UU. cae

, make sure 6: tu regard as; to judge 7: to call on

Be eg | Se 1: ta htave a firm: faith 2: to accept trust-

Py 2 Mase bg ers ss Band on faith 3: t0 have a firm conviction as

ee ett A eo . OF goodness of somcthine 4: to

ineliges, snany oveeae ty ' F. g00d ess of s¢ un is

ath cree A>

es hkewheptbarrows. glass,

ERE « ee 7 ale

lockéd omy children awa:

they've been there for dees

ofo consider to be true, honest

iA

seeing is believing

oStr

od

; OTIS aS Wee

eet ye

~ Pond Rae hee

; ~~� ad =

4 arom

ry a

'

, + .

; bars Sn

_ i :

ohes °

se ~ i; 3 =

ate oe = r - -

MELEE MPR ey MIRE ON Lt

ae � - ne

itt EE

ae oe a

Shi Lala sa oe

«~

yf

Ld GOOG:

TEI PS

a

path 7, ee, ae

es hs?) Be

ae

wast

o my dad died at the age of fifty-

one while cycling, and I had to

come home from New York for a while.

He lay tangled in his bike three-quarters

of the way up the big hill on Old Prairie

Road where a bus full of high school

kids found him. This was in late May,

after the college kids were home but

before the high schools were out. The

heat probably got to him more than the

hill. My dad was a good cyclist.

ttyu Good Bike

Y Dale

Glasgow

rer eres

illustrated by Grace

Rebel Ninety-Five 7

My sister picked me up at the airport,

which was a shock. ITd left home for

New York the summer after graduating

from high school, two years earlier. I'd

been eighteen and Nikki was fourteen.

At the airport, though, she was a couple

of weeks away from her own graduation

and... well, a woman.

Mom was vacuuming the house when I

came in from the garage with my purple

duffel bag in hand. I donTt quite know

what I was expecting, but that wasnTt it. I

didnTt really think that she would be

pining away on the couch, dressed in her

wedding gown, but I didnTt think sheTd

be cleaning the house either.

oMom!� I sat my duffel bag down on

the landing.

She kept vacuuming, not hearing me.

oMOM!� I yelled.

Still no answer. My sister passed me,

going downstairs to her new room, the

one that had been my old practice room

for my spinning. Loud country music

came on downstairs. I heard the dog bark-

ing outside, its loud yips floating over the

open-mouthed humming of the vacuum.

All that noise, and all I could think was:

well, ITm definitely home.

The night I saw my fatherTs bike for the

first time, I was in my room listening to a

little techno on my turntable. ~This was

four years before he died, towards the

end of my junior year of high school, and

ITd just gotten into the whole dance

music scene. I only had one turntable,

allowing me to listen only to the back-

ground track.

It was a Friday evening, and I was lying

on my bed, staring at the ceiling and

waiting for the night. My girlfriend

Margaret, some of our friends, and I were

going to a club.

Literary and Arts

My dad was packing up to go away for a

weekend of playing contra dances. Aside

from teaching folk music at Kerring

Valley Community College, he played

mandolin and banjo in a bluegrass

band called Poor Richard. It got him

out of the house.

I heard my dad come down the hall to

my room. I tensed up, as I almost always

did when my dad was around. ~The door

opened to my room; closed doors never

meant anything to my dad.

oWhat are you listening to?� he asked,

putting on a tie. Poor Richard always wore

matching suits and ties to dances. It was

their trademark, | guess. He paused for a

second and cocked his head to the side.

oITm just listening to a little music,

Dad.� I sat up in bed.

He continued with the tie. oThatTs not

music, thatTs a computer program.� He

laughed at his own joke, then turned

around to look in the mirror, straightening

his tie, checking the length.

oWhatever.� I sat up and turned off the amp.

My dad always had the appearance of

being overweight without actually being

fat. He had a round face with a thick

moustache, like a tiny cloud in front of

the moon, and meaty hands that hid their

grace until they danced across the neck

of a mandolin. His only bulk was in his

gut; he had rather firm arms and legs.

oWhere are you playing this weekend?� I

asked him as he looked at different things

on my dresser: smelling the end of my

bottle of Drakkar, balancing an extra sty-

lus on the end of thick fingertips, glancing

at a folded-up note from Margaret.

He turned, note still in hand. oThis is

the weekend of the convention.� He

turned the note over in his hand, then

laid it back on my dresser, unread.

Poor Richard had gotten one of their best

gigs to date: house band at the North

Carolina Square Dancing AssociationTs

national convention, held that year at the

Charlotte Convention Center. oIs it the

24th already?� I sat on the edge of my

bed and looked over at the Word-A-Day

desk calendar sitting on my left speaker.

Friday May 24: Verisimilitude-The

appearance of being real. oVhatTs right.

~The prom was on the seventeenth.�

oYep.� He played with his tie some

more, and ended up tucking the thin part

between the first and second buttons of

his shirt. oWhere does the rabbit go?�

oAround the tree, down the hole, back

up the other side.� Almost exactly a

week before, my dad had been trying to

show me how to put on a bow tie while

Margaret waited in her prom dress in the

living room and Poor Richard sat in suits

and ties in the driveway. oITll remember

for next time.�

oNext time you'll get a clip-on.� He

turned and grabbed the bottle of Drakkar

on my dresser. He held it up over his

back. oYou mind?�

oNo... but you said it stunk.� WeTd got-

ten into a big conversation about this

when he was standing behind me, his big

arms around me, fumbling again and

again with a bow tie.

oThatTs just because I had to spend a

half an hour around the stuff.� He

sprayed a little on each wrist. oI felt sorry

for Margaret.�

oUh-huh.� | went to my closet to look at

what I was going to wear that night. I had

to pick Margaret up in an hour.

oHey, Aaron, does my tie look okay?� He

turned around.

I smiled at it, crinkling my nose. It was

an ugly tie. oNo.�

oI mean, is it straight?�

oOh, yeah, itTs straight.� I threw a pair of

jeans on the bed.

oGood.� He turned back to the mirror.

oHey, Dad, who you trying to impress?

Ihe guys? Some aerobics teacher?�

oYouTre asking for it,� he said. He had

the highest disdain for the people that

only contra-danced because it was good

exercise. oITm just trying to look good.

ItTs a big gig for us. They'll be people

there from all over the state.�

oYou nervous?� A shirt joined the pants

on the bed.

oNot nervous, just... ready to get there,

to be on stage.� He looked at the clothes

sprawled on my bed.

A horn honked below my window. I leaned

over my bed, pulled apart my blinds. oYour

wish is granted. ~TheyTre here.�

oTheyTre here?� He looked at his watch.

oTheyTre here. Right. TheyTre here. I'm

leaving. Right.�

oGood luck,� I said. oEverything

will be fine.�

oThanks.� He pointed at me. oYou be good.�

oHey, you too. YouTre so snazzy right

now female gym teachers will just be

falling at your feet.�

He pulled his fist back, faking a punch at

me. oOne of these days,� he said, look-

ing a lot more like Ralph Kramden than

he probably intended.

Ten minutes later he was on the road,

probably out on Route 217 by that time,

and I was done changing into my clothes.

[ went into the kitchen and put on my

shoes at the kitchen table, while Nikki,

then thirteen years old, and Mom sat

across from me, looking through a catalog.

oWhat do you think of that one?� Mom

asked Nikki.

oT like that one better. ItTs prettier.� She

pointed at something on the opposite page.

oI donTt think ~prettyT is a factor in these

sorts of things.�

oIt should be.� Nikki put her elbows on

the table.

My left shoe was tied when I looked up

at them. oWhat are you two talking

about?�

oBikes.� Nikki turned the catalog around

so I could see it. The page was filled

with little pictures of bikes, all of them

looking more complex than I remem-

bered bikes being.

oThose are awful big bikes for a little girl

like you.� I was trying to get Nikki to

yell at me. She wasnTt a little girl at all.

In fact, she was more rounded than

Margaret, but it was fun to make her

mad.

oTheyTre not for me, little boy,� she said,

othey're for Dad.�

oDad?� I looked at her, then at Mom.

Mom took a sip of her coffee, and Nikki

took a sip of the water she had in a coffee

cup just like MomTs. oYes, for your father.�

oWhatTs he going to do with a bike?� I

couldnTt imagine my dad even riding a bike.

oI donTt know, I just thought that... well,

I read in WomanTs Day that biking is one

of the best sports for you. And your

father isnTt necessarily in bad shape,

but... you know...�

oSo youTre going to get Dad a bike so he

can prop it in the garage with every other

gift weTve got him.�

Lily, our little Chihuahua puppy, let out

a few yips in NikkiTs room. We watched

as Nikki sprinted away from the table.

A baby voice floated down the hall. oYou

okay, Wiwy? Did you miss Mommy? Yes

you did!�

oShe really likes that dog,� my mom said

as I finished putting on my shoes.

I straightened up. oWhatTs this about a

biker� | asked, looking through the catalog.

oWell, have you noticed that your

fatherTs been in a foul mood all winter?�

oNo more than usual.� My dad was pret-

ty much always grumpy. oNo, not really.�

oWell, I have,� she sighed. oYou just...

you just a/ways see the bad side of him,

thatTs all. | thought a bike would give

him something to do, you know, some-

thing to take his mind off everything.�

oIt'll get him out of the house.�

oWell, thereTs that.� She took the catalog

back. oBut I thought later, maybe next

spring, maybe I could get one of my own.

~hen we could both ride around together.�

I had to admit that the idea of my par-

ents riding bikes together"on a beach,

say, or during a day trip to Charlotte"

had a certain romance about it. At least ITd

know that they werenTt wasting their time.

oWhat do you think about this one?�

she asked, sliding the catalog across the

table to me.

In the middle of the page was a circled

picture of a bike. It looked nice enough,

as bikes go. Very sturdy. The price was a

lot higher than I would have thought.

oHey, bikes are expensive.�

oActually, thatTs about medium-priced.

Do you like it?�

Rebel Ninety-Five

Y

oItTs fine.� I handed the catalog back to

her. oWhatever.�

The night I got home, Mom and I stayed

up very late drinking coffee at the

kitchen table and catching up

on two years... everything I'd

done in New York, like my job

at the supermarket, my spin-

ning, my apartment. ITd sent

letters, called, but thereTs

nothing like sitting and talking

with someone in the flesh. I'd

been a bastard to stay away

that long, thinking a problem

with my father was a problem

with my whole family.

o| got a gig coming up ina

week spinning for a fashion

show during Fashion Week. Not

a big designer, just an up-and-

comer, but itTs a good deal.�

oAnd youTre just twenty-�

oYeah, but you try not to get

much older than twenty-five

in my business.�

oWell, you do have your job as

produce manager if you get

too old for spinning.�

oRight, | want to be assistant

manager of the StopTnTShop

Grocery Store in Queens for

the rest of my life.� I finished

my cup of coffee and sat it

back on the table.

oWant more?� she asked, tak-

ing my cup.

oT donTt know... it'll stunt my growth.�

Nikki was in bed and we should have

been. It felt weird to be up this late

with my mother, brewing pot after pot

of coffee and making dumb jokes. She

was doing fine, all things considered.

Literary and Arts

In fact, she was doing so well that it

almost worried me.

Mom poured out another cup of coffee

for me, and then got some for herself

before sitting down across from me. oWe

should just move the coffee maker over

here on the table.�

oNo... last cup for me.�

oMe, too.�

I looked down into the cup, at the black

liquid. oMom, Nikki was acting weird

this afternoon when she drove me back

from the airport"I mean, of course she

was"but she kept warning me about

things ITm not ready for. It was odd.�

Mom looked into her cup and said, oShe

was just worried for you,

worried that you might be a

little surprised. ~Things got

weird here after you left.�

oSo ITve heard.�

Mom looked down the hall-

way, towards her bedroom.

oWait here,� she said, then

left the table.

I was on the bottom half of

my coffee by the time she

got back. She sat back

down at the table and

handed me a thick manila

envelope.

oWhat is this?� I opened it

up.

oTheyTre part of what all the

fuss is about.�

I found in the envelope a

sheaf of legal papers. ITm no

lawyer, but I dug through

them until | understood.

oDivorce papers?� I asked her.

She nodded, eyes on the table.

oThey arenTt. He didnTt

even know I'd had them

drawn up. ITm sure he had a

pretty good idea, though. | was going to

show them to him this weekend, after | got

everything worked out with my lawyer.�

oMom...� I put the papers down. The

couple in the apartment beside mine in

New York had just gotten a divorce, so I knew

how bad things had to be.

oHe didnTt even sleep here much any

more. HeTd just come home around two,

ride until six, catch a shower, tell me he

had work to do at the college, then fall

asleep on the couch in his office around

eleven. I thought he was having an affair

for a while. but I had him followed-�

oMom!�

oI had him followed and it turns out he

was just a lazy bastard who could never

keep his eyes open past ten oTclock.�

oSo you were going to kick him out?� I

pointed at the envelope, and the papers

on the table around it.

oYou donTt understand, Aaron. You will

one day.� She reached out for my hand,

then laughed, to herself. oThat was such a

Mom line.�

We'd gone to get it on Saturday, gone all

the way across town to a bike shop that

had the model we wanted, the one Mom

had showed me the night before. | did-

nTt even know there were such things as

bike shops.

It was a good trip, the three of us spend-

ing the day together. I had just started

working at the first in a long line of gro-

cery stores, BillTs Grocery, and | was

rarely off on a Saturday, but I didnTt go

to work until five that day.

My sister ran into the living room. oHeTs

here,� she squealed, jumping on the

couch between us.

oCalm down.� I slowly laid my copy of

Spin down on the coffee table.

oMake me.� She put one of her sharp lit-

tle elbows into my ribs.

My dad came in, his tie open and carry-

ing his mandolin case the way some

would carry a briefcase. He looked at the

bike, then at us, his family lined up on

the couch and staring at him.

oWhat the hell did you go buy a bike

for?� He stared right at me.

oTI didnTt-�

oLike we donTt have enough junk in the

house.� He touched the bike, looking at

it with contempt.

oItTs not for-�

oLike youTre going to ride a bike any-

way. Like thereTs anywhere for you to

ride to.�

oDad-�

My mother and my sister didnTt say any-

thing. I think they thought this was

already out of their hands. My father said,

oHow did you pay for this thing? I thought

you were saving up for a new car.�

| jumped off the couch. oWill you listen

to me for a minute!?�

oDonTt you yell at me, boy. I'll knock

your head clean off.�

oDad, shut your big mouth for a minute!�

He made a move towards me, but |

dodged past him and went back to my

room. oEnjoy your fucking bike!� I

shrieked at him from behind my door.

oAaron!� | heard my mom yell. It was

the first time I had ever said the f- word

around my parents.

I didnTt answer, and no one bothered me.

Listening at my door, I heard my sister

go softly down the hall to her room, shut-

ting the door quietly behind her. My par-

ents talked to each other, too low for me

to understand what they were saying, but

I did hear my father take the bike down-

stairs, into the garage.

It was the morning of the funeral, and I

couldnTt find a thing to wear. I was still

in boxers and a ~T-shirt, sifting through

the clothes I brought home. All I had was

a few pairs of jeans, a bunch of T-shirts,

and a black turtleneck in case it got cold.

[ didnTt even think about the funeral

when I was packing.

Mom knocked on my door and walked

in wearing a black dress and holding a

black hat.

oWhy arenTt you dressed yet?� She

looked at what I brought home, then

back up at me. oYou didnTt bring a suit

home? For a funeral? You come home for

a funeral and you donTt bring a suit?�

oI forgot.� Wrong thing to say. oNo, I

didnTt forget, of course, I just wasnTt

thinking that way. I was just thinking

about coming home.�

She just stared at me. She wasnTt mad,

really, but what do you say to a son who

comes home for his fatherTs funeral and

doesnTt bring a suit?

oLook...put on your turtleneck and your

black jeans. Ill be right back.� She left

the room.

I was tucking my turtleneck in when she

came back, carrying a black dinner jacket.

oItTs rayon, but it'll have to do,� I looked

up at her, and she wasnTt smiling, but I

was pretty sure she was joking.

oIs it DadTs?� I put on an old black belt

of mine ITd found earlier in the bottom of

my closet.

She handed me the jacket. oIt might be

a little short in the arms, but you'll only

be wearing it for a few hours.�

I just held it for a second, looked it over.

It needed to be dry-cleaned.

oI> " 7. ane 7 =. o y �

Put it on,� she said again, oWe need to go.

I slipped the jacket on. It was a little

Rebel Ninety-Five

1]

tight in the arms, as though I were being

held in by a harness, but it at least

looked like it fit.

It smelled like Old Spice, a present my

father would get from all three of us on

his birthday. ~Three bottles of Old Spice

would last him all year. HeTd usually run

out a week before his birthday.

| looked at myself in the full-length mir-

ror on the back of my door. I was draped

in black, my bare feet sticking out the

bottom of my faded jeans.

[ turned towards my mom. oHow do I

look?�

oLike a mortician.�

I looked at myself in the mirror from

behind. oI look like a Goth-boy.� |

knew she wouldnTt get the joke, but I

said it anyway.

oYou look like an Ann Rice groupie,� she

said. I'd sent Nikki /nterview With The

Vampire for Christmas last year, and Mom

had read it, as well as the rest of the series.

[ tried the jacket buttoned, then unbut-

toned. oI look like a Beat poet.�

She laughed at this. ITd gotten into the

Beats about the same age everyone else

does: junior year of high school. And, like

everyone else, ITd gotten out of them in

my senior year.

o*I saw the best minds of my genera-

tion...T� I recited in a deep voice, trying to

get her to laugh again. ~here | was on the

day of my fatherTs funeral and ITm trying

to get my mom to laugh. ITm a bastard.

oFinish getting ready to go,� she said at

the door. oWeTre leaving in half an hour.�

I sat down on the edge of my bed and

put on a pair of white socks. Finishing

that, | twisted around to grab my combat

boots and felt something in the inside

Literary and Arts

pocket of my jacket.

It was an envelope, folded in the middle.

Just a white envelope, with oFrank L.

Page� scrawled across the front. My

fatherTs name.

I started to open it, but there was a

knock on my door and I put it back in

my jacket.

oCome in.�

Nikki was wearing a black crushed velvet

mini-dress with a big, black, floppy hat. I

guess we were both new at this.

oYou look like a Black Panther,� she

said, laughing over me.

I raised my fist in salute.

I thought the bike would just rot in the

garage, but Dad started riding it about a

week later. HeTd take the bike out for a

while, wearing a pair of sweat-pants, an

old ~T-shirt, and the grass-stained tennis

shoes he wore when he mowed the

lawn. HeTd just fool around the neigh-

borhood, staying out later and later as

the days got longer.

By the end of the summer before my

senior year of high school, he would be

gone for an hour a night, and two hours

on Saturdays. (Though we never went to

church, my father was still religious and

never rode on Sunday.)

I was changing, too. ITd saved up and

gotten my second turntable, ITd lost my

virginity, and I was shaving everyday.

~Things were looking up.

~Two Saturdays before school started, |

was in the garage, playing around on my

system when Dad rode in. He had an old

backpack on behind his ~T-shirt, as well

as a pair of jogging shorts, his helmet,

and a pair of biking gloves. He was get-

ting a little thinner, and everything

looked baggy on him.

Saturday was a big day for Dad. He

would double the milage he usually rode

and go into town for a ogoodie�, some-

thing new for his bike. It was usually

something small and relatively cheap,

like a gel seat-cover, new handle-grips, or

a pair of toe clips, but this time his back-

pack seemed heavy.

I took off my headphones, let my two

albums play. oWhadja get?�

He looked at me without saying a word

as he walked the bike behind me. oNew

seat.� He put the kickstand down.

[ turned around. oWhatTs wrong with the

one you got now?� I asked.

oToo heavy. Slows me down.� He

looked all around at my feet. oWhere are

my tools?�

oI moved ~em up on the shelf, ~cause

they were in my way.�

He took his tools down. oDonTt touch

~em,� he said, that simple.

My dad was a quick worker, throwing

himself into whatever he put his mind to.

[ went up to get a sandwich, and when |

came back down, he already had the old

seat off and sitting in the corner of the

garage, and was adjusting the screws on

the new one.

oDid you have a good ride today?� I took

the albums off the turntables.

oNo better or no worse than any other

day.� He put the gel seat-cover on the

new seat, then sat back on the bike and

glanced up at me. oThis is great.� He

sat up, then back down on his seat.

oOh, yeah.�

I looked away from him, from his enthu-

siasm. In his backpack was something

else, something red.

oHey, Dad,� I said, owhat else did you

get?�

oNothing.� He looked down at the back-

pack and picked it up by leaning over on

the bike without getting off. I had no

idea he was that flexible.

oWhat was it?� I asked as he zipped up

the backpack.

oNothing, okay?�

oDad... what did you get?�

oIf youTll shut up about it, I'll show you.

But donTt say a word to your mother or

Nikki, okay?� He watched me.

" kay.�

oPromise?�

oJeez, Dad...yeah, I promise.�

He opened the backpack and took out a

small one-piece spandex biking outfit. |

choked back a laugh.

oWhat do you think?� he asked.

oUhm...�

oRidiculous, huh?�

oIs it for you?�

oOf course itTs for me. Who else would it

be for?�

oI donTt know. I canTt imagine that it

would fit you, though.�

He looked at it, held it out to me. oIt

doesnTt fit"well, not comfortably"but

in a few months it will.�

[ took it from him. It felt springy, giving.

| wanted to have it on, oddly enough, to

feel it over my body. oWhy did you get it

so small?�

oIt'll be my goal. I'll see how fast I can

get into it without looking like an idiot.�

He took the outfit back from me, held it up

to his body. Then he looked back at me,

grinning like a kid on Christmas morning.

DadTs funeral was weird, or maybe itTs

just that all funerals are weird. It was at

Kerring Memorial Park, in their little

chapel. I applied there one summer to be

a groundsman, but they didnTt hire me.

Poor Richard finished the ceremony with

a Scottish mourning dirge that ended

remarkably cheerfully. It was this drab

little piece for about three minutes, then

it got brighter and happier until it was so

catchy my foot was tapping and I was

bobbing my head. ITd love to sample it.

When the funeral was over, I understood

that my job was to stand with Nikki and

Mom at the back of the chapel and

receive the guests. Nikki and I tried very

hard to be what we thought grieving chil-

dren looked like.

oI feel like ITm at a wedding,� Nikki

whispered to me after we get to the

back, before the guests started filing out.

Her assistant manager at Sears was married

a few months earlier, and my sister was one

of the bridesmaids, so she should know.

Then the guests were upon us, hugging,

crying, holding our hands, or just giving

silent, firm handshakes. I was very aware

of the fact that I was the most under-

dressed member of the funeral, with

Nikki a close second. I smiled at each of

them, the only real gesture I had in me,

and bowed my head slightly. oThank

you,� I wanted to say, othank you for

taking the time to come,� but that didnTt

sound quite like what they would want

to hear, so I didnTt say anything.

I was surprised at how many guests had

come. I thought the audience would be

medium, but the place was full of rela-

tives, musicians, and fellow professors.

An odd crowd, but a large one.

(There were also a large number of short,

strong, tight men in suits: members of

the local cycling club, my mother told

me in a whisper. Cyclists take care of

their own, apparently.)

Finally everyone was gone and that part

of my life was almost over; all that was

left was the burial. My mother and my

sister and | stood in the lobby after the

last person left, and we couldnTt think of

anything to say. ~he two-hour service was-

n't over quickly, but it was over suddenly.

oI guess we go out to the limousine,�

Mom said, looking around the chapel at

the few people still left. Her uncertainty

made me feel better.

oWhereTs Mr. Cottrell?� Nikki turned

around and looked up the aisle. Mr.

Cottrell was the representative for the

funeral home who helped walk us

through the whole ordeal. He was

indispensable, really, though he looked like

he was just going through the motions.

oI donTt see him,� I said. I didnTt even

look. Like I said, I liked the group

confusion, made me feel like I fit in. |

put the serviceTs bulletin in my jacket,

and rediscovered the envelope ITd found

earlier. I pulled it out.

oI guess we'll just go on out, then.� Mom

looked back and forth between us. Nikki

and I both shrugged. Mom put on her

hat, nodded, and turned. | fell in behind

Nikki, opening the envelope. I didnTt

even look at it before a strange urge

gripped me, a feeling of what I truly

wanted to do so obvious it surprised me.

I almost dropped the envelope, but

shoved it in a pocket and said, oGo on...

go on out and wait for me. I wonTt be

more than a minute.�

I half-ran up the aisle, past the few peo-

ple still milling about, past Reverend

Meadows, past the two older women car-

Rebel Ninety-Five

13

14

rying out flowers, to the coffin.

I hadnTt looked at him until then. I did-

nTt want to see his body and I had con-

vinced myself that I hadnTt cared to see

it. But he was still my father, and ITm

half of him, and we were both so alike

sometimes it scared me, truly scared me,

because I did not want to be like him.

Not at all.

He was firm, tan, and his face seemed to

have been pulled tight at the back.

Though his expression had a loose quali-

ty about it, as if he were asleep, his brow

was slightly furrowed, his jaw set.

I was crying, but not for the reason

everyone probably thought I was. ~They

thought I was crying because I had lost

my father three days earlier, and thatTs

wrong. I was crying because | had lost

my father five years before. I was crying

because he should have been a little flab-

by, and he should have been lying in

such a way that his extra chin showed. |

was crying because_his short, thin, haircut

should have been shaggy, trying to hide

his rising hairline rather than display it

with pride. I was crying because he

should have had a moustache.

I was just standing there, arms at my

side, crying over a man that only resem-

bled Dad, when I felt another hand in

mine. I thought it was Nikki, and almost

didnTt look up. But her fingers were longer,

thinner than my sisterTs, and I looked up to

see Margaret, my ex-girlfriend. I hadnTt

even seen her at the funeral.

She turned up a corner of her mouth.

oCome on, your mother and sister are

waiting,� she whispered.

I tried to stay, I tried to drop to one

knee, but she pulled me up. oCome on,�

she stumbled, oyou're... youTre the man of

the house now, I guess. Be brave.� All this

from a girl I hadnTt seen in two years.

I walked with her then, and I started to

Literary and Arts

feel as though I werenTt really a part of my

surroundings at all, as though I were watch-

ing it from behind a one-way safety mirror.

She took me to a bathroom, washed my

face. My high school girlfriend, the rela-

tionship two years dead, and there she

was wiping off my face with a Baby Wipe

while I leaned on a radiator at my

fatherTs funeral.

oHow have you been?� I finally got out.

ItTs such a dumb thing to ask, but what

else was I going to say?

She smiled, kissed me on the cheek. |

couldnTt say anything. | opened my

mouth, and nothing came out.

The door opened and Mr. Cottrell came

in, cigarette in his mouth. oWhoops,� he

said, osorry for, uh...�

Margaret pulled me up an past him, into

the hall. She tried to go back to her car,

but I made her ride with us in the limo.

Throughout my senior year, | seemed to

see Dad only in the garage. Leaving or

coming back, or adding something new to

the bike, it was as though he lived in the

garage itself. Mom said the same thing.

Over the fall and mild winter, | watched

the bike change, transform. It became

sleeker, lighter. Over a course of Satur-

days, he added an upgraded gear system,

better brakes, more aerodynamic handle-

bars, and thinner and lighter wheels.

I also watched Dad change. As his bike

became smaller, lighter, faster, so did he.

The moustache was gone from his

recently thinned face, as was any excess

weight. He looked great, if a little odd.

But other little things started to change

as well. He stopped spending time with

us"which was fine with me"and

stopped even being in the house most of

the time. Nikki started calling him othat

eM

guy who keeps his bike here.�

See, instead of releasing his tension

cycling, Dad had found one more thing

to be upset about. He got unbelievably

paranoid that either me or Nikki would

ride his bike, and started chaining it to

the boiler in the garage.

Even the garage had changed over the

three seasons Dad had owned the bike.

One corner was filled with all the stuff

he had taken off the bike and never got-

ten rid of. (oCouldnTt stand to throw

away even a piece of the best present my

family ever gave me,� heTd say, lightly

slapping his newly firm stomach and

hooking a thumb into his waistband.) My

turntables were gone as well. He had

actually cleared out his old opractice

room�"an office, really"so I could spin

there. Despite what he thought of my

music, I donTt think he liked the idea of

my even /ooking at the bike.

On the Friday before the Christmas of

my senior year, Margaret and I pulled

into the garage, framing my father in our

headlights. He had his bike up on the

bike stand, tinkering with the gears.

oHowTs it going, Dad?� I was getting out

of the car. Though we fought every time

we talked, I still tried to start a conversa-

tion with him. I missed him.

His grunt made a noise that could have

been interpreted as oOkay.�

I opened the trunk and grabbed the few

bags I had in the back: Christmas pre-

sents for Nikki and Mom, and the few

groceries ITd been asked to pick up.

DadTs present, a twenty-five dollar gift

certificate at the bike shop, was in my

back pocket. oDid you get to go out

today?� I asked, because it had rained

that morning.

oYeah.� He didnTt look up from his gears.

oGood.� I handed a bag to Margaret, pre-

sents for her family, and closed the trunk.

He didnTt say anything else, and I just

stood there, holding two Gap bags.

Margaret looked at me and I shrugged.

We left the garage.

In the house, Margaret sat at the kitchen

table and watched as I put away the gro-

ceries ITd gotten at BillTs.

oYour dad looks great,� she said. She

never really liked my dad, but was im-

pressed by his new hobby. She told me

how good he looked every time we saw

him.

oThanks,� I answered, as if I had any-

thing to do with it.

Margaret and I had met two years earlier,

when we had both been dragged to a

square dance by our fathers, both of

ox Cua yee, cass oAnndual *7 >

SR Fieariens ican 7s ee hous .Berkane

ND = 40 i0 wih * - Ay Hap

RON oy Ovezzane i cc, a Oujday 3

x " . Tau , . o* 7 T ae

Jeftadas

K CN oN

me Oe

A ** 8,

*Ghataouet

VY Tieme en

whom were in Poor Richard. She had

brought a book, and she sat on the side,

sipping a Diet Coke and reading. I tried

to talk to her, but she was distant and

polite. I started volunteering to go with

Dad every weekend, enduring the folk

music in hopes that the black-haired girl

would be there, sitting in the corner with

a novel. I finally got up the nerve to ask

her for a dance, something that had never

occurred to me before that evening, and

she accepted. Neither one of us knew

what we were doing, but it was fun. She

was there the next weekend, and every

weekend after that, without a book.

oMy dad was asking about him the other

day, wondering if he was still playing any

gigs at all.� She touched the side of her

left eye. Her contacts were probably

bothering her.

Dad had dropped out of Poor Richard

two months earlier, claiming that he

wanted a break from playing, but I sus-

pected it was because he wanted more

time for his bike.

[ think heTs only playing in class now.�

[ put up the peanut butter, then turned

towards her. oNo, wait... | heard him in

the den playing his banjo the other day,

when it was raining.�

oAnd?� she asked.

oAnd... he stunk. Actually, he wasnTt bad-�

oBut in comparison, right?�

oExactly.� | opened the fridge, put away

the milk.

oYou know,� Margaret said, omy dad said

he should take up cycling, too. Biking,

he called it.�

Or, 4

Aria oOma a

reat NZS

7 Mines .

eet EQUITIES

"" +

x

Oe is ie

RS ae AN (117 i (ae

ON le i

CUE)

BS NR NO gig ib o Gi ~i

SES NREL chip ty alae Re THE HEAD

a

Me

i A ie Ry POS (Se at Atta Or Cons ar veTIon

\ Sia ) oe SAE ge i \

oN \ ~ y 4 oy 5 mis i ,

. ~IN ~y \X

\)

o4

Rebel Ninety-Five /5

"

os

ms as

oTell him I said to get a real mid-life cri-

sis.� | threw away the bags and sat across

from her at the table.

After a while, she asked, oDoes he keep

everything he takes off the bike?�

I nodded. oEverything.�

She rubbed at the other eye, this time.

Something hit me, all of a sudden, and I

leaned forward. oDo you think that after

he replaces the last original heavy piece

of our bike-�

oa4 nut maybe, or a metal screw-�

oRight. When he replaces that for a

smaller, thinner, plastic one, will it still

be the same bike?�

oWhat do you think?�

oIT donTt know.�

oYou know what,� she said, finally, oI

donTt think it was the same bike after he

replaced the first piece.�

The night after the funeral, my sister and

I were working a jigsaw puzzle in the den.

Weird for us, but it had been a weird day. I

heard my mother upstairs, cooking.

oGrieving is not something that one is,� |

said, trying to fit two pieces together,

oitTs something that one... no, walt.

Grieving is something that one does, not

something that one... no...�

I shut up, and Nikki just looked at me.

Only eighteen and she already had an

eat-shit-and-die stare. oUh... good call,�

she said.

It was a Friday night, and it felt odd for

both of us to be home. I know itTs cus-

tomary to stick around whenever your

father dies, but this was different. Mom

had even tried earlier to convince us to go

out for a while... to a club, maybe. She said

Literary and Arts

it would clear our heads, but it didnTt seem

right. Just like it didnTt seem right to have

the television on while we worked the

puzzle, so we didnTt. It didnTt mesh with

our ideas of a house in mourning.

But we did have a tape of some of my

music on the stereo. I made it for Nikki

about six months ago, when I pulled

the graveyard shift during a rave. It was

all she had of my music, but it was old,

and I cringed at some of the stuff ITd

done: how another sample would have

worked better here, how I screwed up

the tempo there.

Lily, our dog, started barking, so I got up

to let her in. She had a little house in the

garage she stayed in during cold weather.

For no reason, Nikki followed me.

oWhere are you going?� I asked.

oWhere are you going?�

So we both let the dog in. I opened the

heavy wooden door at the back of the

garage, Nikki opened the screen door.

But the dog just stared at us.

oCome on in, Lily,� I said, but she did-

nTt budge.

oCome on, rat-dog,� my sister said. Nothing.

Finally we closed the door, but we didnTt

go back into the den. I poked through

the garage, examining our old Christmas

decorations, DadTs power tools, and

NikkiTs and my old toys. Nikki reached

behind a pile of old encyclopedias and

grabbed a pack of cigarettes. Back when

I was living at home and smoking, I used

to come out to the garage to smoke, too.

She didnTt offer me one, but laid down on

the hood of her car and stared, I guess, at

the exposed fiberglass in the ceiling.

Someone had returned his bike.

Someone had returned it, set it up on the

bike hooks, even. ~The only thing that

told me it hadnTt been hung there by

Dad himself was that his helmet wasnTt

sitting on the seat (it had cracked open

when heTd fallen off the bike) and his

red cycling outfit wasnTt on the shelf

beside the bike (they had cut it off in

the ambulance).

oWho brought it back?� I raised my hand

to touch the frame.

oDonTt touch it, DadTll kill you.� She

laughed at this, exhaling smoke. I didnTt

think it was funny, but I laughed too.

I let my hand drop though, as if Dad

might just have been able to kill me for

touching it.

oWho brought it back?� I asked again,

hand at my side.

She was quiet though. After a moment of

no talking, no moving, Nikki finally said,

oRemember when I was little and I was

scared of monsters?�

oYeah,� I lied.

| heard her inhale, then blow out, but I

didnTt turn around. I didnTt want to see

her smoking. oYou know what Mom told

me that made me finally shut up about

monsters?� ~Though she was speaking

with normal inflection, she was still start-

ing straight up at the ceiling. oShe told

me that of course there were no monsters

in the house. She said, ~Do you think your

father would let monsters in this house?�

I didnTt say anything to that. What could

I have said? My sister sat up, took one

last drag, then dropped the butt on the

floor, squashing it under a red Converse.

She picked the filter up and put it in the

back pocket of her jeans. She probably

flushed it later. ItTs what I used to do.

I left the bicycle and looked around,

coming to the pile of old bike parts in the

corner, what was left of our original gift.

After a while, Nikki followed my look to

the discarded parts. oYou know,� I mum-

bled, oif we took these leftover parts we

might be able to make a pretty good bike.�

The day I decided to move out was just

after graduation. I hadnTt applied to any

colleges, but my parents didnTt mind

since I was doing pretty well at my job at

BillTs Grocery. The produce manager,

BillTs niece, was going off to veterinari-

anTs school in August, and I was taking

her place. Plus, I was pulling in about as

much as I was making at the store by

DJing parties every weekend.

It was a Saturday evening, and it was just

like any other Saturday evening in the

summer, aside from the fact that I had

nowhere to return to in a few months,

which was nice.

I was in my ooffice,� playing around with

my system. I had recently sunk all the

money ITd made at an after-graduation

party on a nice keyboard, and I was using

it in my mixing. I had an old tape of my

fatherTs"many years ago heTd made me

a tape of him playing as part of a birthday

present"and ITd MIDITed it through my

old Macintosh. I was using it as a sample

over top of a Julee Cruise cut I was spin-

ning to. It sounded good, and I had the

volume up because Mom and Nikki

were out shopping for swimsuits and Dad

was"where else?"out riding.

I let the Julee Cruise album play and

switched over to my third turntable,

which was dutifully playing a monoto-

nous dance track, over and over.

I added in DadTs dulcimer just over a

breaking backbeat. ITd assigned the sam-

ple to one particular key, and I was play-

ing these chords behind it. It sounded

spooky, like Folk Gothic. It was one of

the best things I had ever done. ~The

money I was spending was going to a

good cause.

As I said, I had the volume up, so I did-

nTt hear my dad come in. But when he

opened the door, all spandex and wind-

breaker, my hands jumped off the keys

as if suddenly burnt, and I quickly faded

the master volume down to nil. oHi.

Dad. Did you have a good ride? Mom

and Nikki are out buying-�

Not loud, but strong enough to interrupt

me: oWhat was that?�

oJust me playing around. Just spinning.

With my new keyboard.�

He was looking over my shoulder, at my

system. oThat was me, wasnTt it? That

was me, right?�

I tried to answer, but he was already past

me. oDad, wait, I thought you...�

He was pulling wires out of the back

now, like yanking hair out of a scalp, and

spitting words.

oTL will.not.have.my.music...� I jumped to

his side, yelling. He pushed me back, a

lot stronger than I thought he could be. |

stumbled back and jumped at him again,

landing a short punch on his arm, just as

my mixer fell off the table.

Dad now pushed me down, and turned

to stare at me. He was no one I knew. I

lurched to my feet, then tripped out of the

room. We both knew where I was headed.

The bike was on the hooks heTd installed

in the far wall after we put the doghouse

in the garage. It was locked up"I knew

that without looking"so I grabbed a

shovel, the first thing I found.

| swung it over my shoulder like a base-

ball bat because the ceiling was too low

for me to use it like a sledgehammer. But

just as I was about to swing, I paused,

confused. At first I thought heTd gotten a

new bike, but then I realized heTd taken

the final step.HeTd replaced the frame. It

was a completely different bike.

The pause cost me the only chance I'd

get to hit his bike. He slammed into me

like a bullet, driving me against the wall

and making me drop the shovel.

He was a lot stronger than me, a lot

stronger than ITd imagined. I didnTt beg

or yell. HeTd caught me. We hadnTt

talked since this began, and we didnTt

start then. He choked me with the han-

dle of the shovel for a while, rubbed my

face in the spokes, kicked me with his

little cycling shoes. I couldnTt do a thing

to stop him.

My father was doing all this to me.

My father.

Finally he left me in the garage, sure that

| wouldnTt dare touch his bike. Five min-

utes later I was leaning on the boiler, let-

ting my nose bleed into a fabric softener,

and | heard the shower come on.

Before the shower was off, | was in my

Honda, purple duffel bag packed and

opened in the front seat, and pulling out

of the driveway.

Margaret lived only three miles away,

but I drove slow because my side hurt

and ITd only just called her. (oHello?T�

sheTd said. oGet ready to go, we're leav-

ing.� I'd whispered into the phone, then

hung up. SheTd know what | meant.)

We'd talked about this before, about how

nothing was stopping us from just leav-

ing, just moving on. Margaret had a good

job at Waldenbooks, and she was putting

off college for a year. We'd talked about

it, about how good it would be to just

leave, but it was just talk. We both knew

we'd never do it, and that was why we

talked about it so much.

Margaret lived in a room over the garage,

and her light was on. I threw a pebble at

the glass, something I always did. Kind

of like a joke, almost.

Her curtain fluttered once, then opened.

A Margaret shadow stood in the light.

Rebel Ninety-Five

17

_

"T ee

Come on, I motioned, waving my hand

towards me.

She shook her head.

I grabbed my duffel bag out of the pas-

senger side, showed it to her. | motioned

for her to join me.

She shook her head again, but slower.

My insides shuddered for a second, I spit

up something red. I motioned at her to

hurry up. I looked up to see her, a hand

over her mouth, slowly shaking her head.

I looked around. I wasnTt expecting this,

but I should have been. I walked around

my car, kicked a tire. Looked up. She

blew me a kiss and I gave her the finger.

I drove around town for a while, but

ended up back at my house, unpacking

my stuff. I didnTt say a word to Mom

about what happened. And a week later |

was gone, Margaret behind me, my

father behind me.

The night of my fatherTs funeral and |

was throwing pebbles at a dark window.

It was a cloudy night and there was no

moon, no stars. It would be raining later.

Literary and Arts

It took three hits before the light came

on and Margaret was standing at the win-

dow. I walked into the square of light on

the ground so she would know it was me.

She was straight above me then, dropping

a look down on me. I just spread out my

arms, palm up, and tried to catch it.

She disappeared from the window. ~The

bedroom light went off, leaving me with

my arms outstretched like a scarecrow in

the dark while she crawled back into

bed. But then the garage light came on

and Margaret padded across the cement

and unlocked the side door. I ran

around the side and stood at the door

while she opened it.

We had not talked but I was talking

then, as she leaned her long body on the

door, only a night gown between us. oI

donTt want to be brave,� I was saying, oI

donTt want to be the man of family.�

Four hours later, the sky was gray like

old asphalt and I woke up in my clothes

with MargaretTs hand slowly moving

across my face.

oWake up, sleepyhead,� she said. I kept

my eyes shut.

oWhat... what time is it?�

She kissed me on the forehead. oAbout

five-thirty. My parentsTll be up soon.�

My eyes crept open. oOn Saturday?�

oMy dad works on Saturday mornings at

the plant. Mom gets up with him.�

I rolled over, tried to go back to sleep,

but she shook me. oHey, none of that.�

Another shake. oWake up, you need to

hit the road.�

oWhy?� I asked without opening my eyes.

oBecause I may be a liberated woman of

twenty, but I donTt show up at breakfast

with my high-school sweetheart in tow.

Besides, I have to be at work by 8:00 to

open the store.�

I was awake then, and I rolled over on

my back, taking her hand in mine. oSo

you Tre manager now?�

oAssistant. But getting there.�

oWhy are you still here?�

oI moved out for a while, but came back.

You know how it goes.�

oNo, why are you still in Lewisberg?

Why are you still in North Carolina?�

ooc

And go where?� she asked. oNiew York?

You maybe. Not me.�

My chest tightened. Not so much that it

was true but that she knew it.

When are you going back to the city?�

she asked.

I didnTt answer. I tried to, but I couldn't.

I'he house was quiet for a long time, and

I looked at the sky to see if I could watch

it get brighter. I could.

owy ; e R

hatTs my dad,� Margaret said when an

alarm went off in the main house. oYou

better get going.�

[ got out of bed, found my boots. I was

still wearing the same clothes | wore to

the funeral, and I found the dinner jack-

et on a charr.

Be quiet with your car,� she said as |

tied the laces. oCoast down the driveway

before starting your engine.�

~I didnTt drive.�

You walked all the way over here?�

oDonTt worry about it.� I stood over her,

and struggled with the jacket before

finally getting it on my back. oThanks

for listening� was all I could say, but it

sounded so cliché that I wanted to grab

the words and take them back. oMaybe

tomorrow"I mean, today"we can... |

didnTt know how to finish the sentence.

She laughed. oGet out of here and give

me a call at the store after two, okay?�

Yeah, okay. Great.� I nodded and she

rolled over in bed, pulling her covers up

around her. Her hip stuck out like she

had an extra joint in it. Girls can do that.

he nightTs prophecy of rain was ful-

filled by the morning. It was a slow, casu-

al mist, but it was rain nonetheless.

Luckily, I had enough sense to park the

bike under the awning of the garage, so

it was still pretty dry. I wheeled it around,

pointed it down the driveway, and took off.

I still didnTt have a handle on the gear

system, but I had enough of it down to

get a good speed up as I raced through

the gray streets of the development. |

was quiet, fast, wind and water on my

face, legs pumping in grey morning. | felt

like a force of nature.

I was cutting towards my house like a

laser, going through yards, down alleys. |

was coming home, delighting in the

empty street and open speed.

Past Jeffrey WeaverTs old house, where

Margaret and I had gone after graduation.

Past Mrs. HaulmenTs house, where | had

learned piano as a child. Past Anthony

BuscosiTs house, where my first best friend

had lived with his family before he joined

the Air Force. Past Bill LehgmanTs house,

my first boss, on the corner of Old Prairie

and Harrison.

Faster, faster, faster.

I turned onto Old Prairie, cutting through a

corner of BillTs yard. I saw then where the

quickest path home lead me. Before I real-

~zed it. I saw that I was abandoned at the

foot of the big hill on Old Prairie Road.

| almost stopped pedalling, but didnTt, and

instead shifted to a much lower gear and

leaned forward, legs jabbing at the pedals

as my inertia ran out. Halfway up, heart

pounding, legs yelling, bike creeping,

the battle was won but I had lost. The

bike simply was not going fast enough

to stay upright.

| picked up the bike"lighter than |

and threw it to the side of the

thought

road. The dinner jacket, note still unread

in the front pocket, joined the bike a few

tired paces later. It was much too tight to

run in, and I had to keep moving. I was

coming home.

Rebel Ninetv-Five

1Y

= T

20

Literary and Arts

Pa

gs re 0 ach mnie

ane shook :

¥

ie

;

i

:

2 eho atom

"T

ute Fs MHL

iE

|

Sex.

eee aT Ra UB TSE

je oe goon�

She AS

.

iIlustrated by David Rose

heir

ay.

nd

renTt fly

[heir pale

oa

Ld

yagi :

Cc

St

nd only.t

lently, W

iven.,.

stil

e wavel

j

he

ite, 4

ind.s

face

ng. of f

st wh

o

=

-"

a

a *

eo

* "_

oo

2)

=

es were enclosed

: ff

rf,

around he

ing

asin

ure

, th

owalked

if

>

5

c ;

As

:

TA. ee

"" se

~

ee et eRe Oe mw,

Alexande -

Ae nbn pete LO ee a ee

Karena,

cla

Al

BAR AT tl TEN LORD DIMES CAEL me

24

Literary and /

They lived across the

street, the nuns did, in a

big red brick building set

at a right angle to a church

of the same red brick. Each

week day and every Sunday,

we, the children of different

color browns, left row upon

row of low, rust-brick buildings

we called home to attend school

and church across the street.

The nuns taught us that heaven

was in the sky, hell was under the

earth, and purgatory, they pointed

(The nuns knew everything, I thought.)

At nine oTclock mass, they sat in pews

behind us, their pink fingers poised over

black holy beads, ready and waiting to

dig into our small brown shoulders if and

when we gave in to the inevitable urge

to fidget during the two-hour service.

They would nudge us when it was time

ok SA AE

& -

se OS

on

z 2

ay Bk =

mY .

? a

x wee o

etal mre ies 2

Le

out, was somewhere in between the two.

moe

at 4. Wa *

oet

~ 2 a

oak.

~ . 7 +. * as ~Tw

pom are 2 ae

to kneel or make the sign-of-the-cross or

respond with the right words to Father

MichaelTs Latin chant. We sang amens

and hallelujahs in high voices, recited

the Hail Mary and ~The LordTs Prayer

(that we had to memorize at an early

age) and received the Blessed Sacrament

at the red, velvet-padded railing with

outstretched tongues and straight faces.

| was six and in the first grade when the

nuns chose me to give out diplomas to

the graduating kindergarten class of

1958. I would be outfitted for the occa-

sion, they told me, in a full nunTs habit,

black holy beads and all. After mass on

the day of the event, I was allowed for

the first time to pass through the

brass-knobbed, white double doors that

separated where the nuns taught school

from where they lived, so they could

dress me in the habit. My two older sis-

ters had entered that most private world

7

WS

SHA

si1% ~a

Sm)

+

~

3 iy

ys

(3

AL

vt

Re coe pe

- we Cae PETAL IC Ves TB) 4 Be ee eee

; . TTI TTR = _

> SIRIS Ts Ta Fe PIL AIS TALES EE RASAD EL ADL sso oF howe +

3. Saswsigiae: Sates ar ORES .

7 eae nD a oes 1286 -

before - they came there most Saturday

mornings to scrub hardwood floors, pol-

ish full sets of silverware and wash and

fold bed linen and towels. They would

return to our world of concrete and steel

and tell our mother, our younger sister

and me how high the ceilings, how shiny

the floors and how huge the ice box in

the spacious kitchen were.

I trembled as I walked through the nunsT

living quarters. | felt | was in a place that

was even more GodTs house than church,

for hadnTt the nuns told us they wore

those gold bands on the ring finger of

their left hands because they were mar-

ried to God? (Imagine - chosen by God

to be his wife for life.) Through another

set of doors, | could see the room where

the wives of God ate. There was a long

table covered with a pure white table-

cloth and set with shiny silverware and

white china plates ringed in gold.

See-through white lace curtains hung at

low, skinny windows. In a far corner, an

old nun dressed in all-white slowly pol-

ished a dark-wood china cabinet. A por-

trait of a pink Jesus with blue eyes -

exactly like the one that hung in our liv-

ing room - hung on a wallpapered

wall next to the cabinet.

ad >

~Two young nuns led me down a long

hallway of shiny floors, polished tables

and stuffed armchairs. We walked

through the big kitchen with the huge

icebox to the pantry beyond where

canned goods and boxes of food lined

the shelves. ~The nuns told me to

undress down to the new slip and

panties my mother bought me just for

that special day. ~They then covered my

braided hair in soft muslin cloth. They

enclosed my brown face in stiff white

casing. My six-year-old body was hidden

beneath folds of heavy, black robes.

They wrapped my fingers with holy

beads and told me I was a blessed child

for having been chosen and to always

keep my hands folded and held |

waist-high. Except for my brown face

and hands, I looked and moved just like

the nuns. I felt chosen, blessed. That

night after that big day, I crossed back

over to my world of different color

browns and told my mother that when |

grew up, | wanted to be pink.

me}

ne�

+

~ a ~ he

wee ee BPP

~~

Vek

~

"

ro]

>

tae? e

2

SZ,

» Be

26 Literary and

sHe comes back for A dAY

illustrated by Amanda Baer

she

comes back for a day and she

wants me fo

visit and

wants me to

wait in the lobby for hours but

| have to go and

but

she isnTt here (oh now

kelly | long for those days in the

mud

when we drove between orchards

in wavy directions)

and | dream about apples the

bulbs of october they

dance on the edges and bob in the water and

| cannot touch her or

stand in this foyer for

one minute longer

(oh

how could you go with your parents to new york

when knowing

| loved you and wanted you

here

and why am | dreaming

of apples in autumn

all red in their piles

surrounding my snoring

until | wake

(crying

for someone

that somehow through years

disappeared) ?).

Rebel Ninety-Five 27

"-

28

T= SS lll SS

ae AD ee a

illustration by Jonathan Peedin

he sound of breaking glass is fol-

lowed immediately by a hollow

thud like a ripe melon being hit with a

hammer. We focus on the major insolent-

ly standing by the windows. The double

report of high-powered rifles thunders

through the room before the majorTs limp

body slaps the floor like a wet towel. The

snipers are close, too close. O.K. and |

look at the majorTs body but donTt go any

closer. We know we canTt do anything to

help him. I almost wish I could remem-

ber his name. O.K. nudges me with his

elbow. Yeah, it is time to go to work

again, so we leave.

O.K. and I are a team, a pair, and in a way

friends. We are the manhunters for this

sector. Once we would have been called a

counter-sniper team. That was before

1D).C. was nuked. Since then things have

changed. No one knows exactly whoTs

done what and to whom, but we know

whoTs getting the slimy end of the stick

" U.S. Not just O.K. and me. I mean the

whole U.S. of A., including Canada.

Seems like whoever pushed the wrong

button on the other side had help in high

places on ours. Not one of our birds even

left its lair. ~They never will now.

As we leave the briefing room, O.K. and

I canTt help but notice that the headquar-

ters staff are spastically running around

like a freshly flushed covey of quail.

Some of them are even looking out the

windows to see what is happening. This

tells us they are wor front line troops. |

tell O.K., oSuits and guns.� He looks at

me and nods his understanding. O.K. and

I take our gear and weapons out of our

Literary and Arts

VISITORS

travel packs and get ready for work as the

stutter of gunfire continues.

oThree,� he says. I look around and see

two more bodies hanging out of the win-

dows. We need to do something fast.

People are yelling and screaming for help

all around us. It seems everybody needs

help these days. ~The whole center of the

country is hot. From Oklahoma to the

Arctic Circle, a path three hundred miles

wide, will never be the same. The mis-

siles came in waves and walked their way

north from ~Tulsa to Baker Lake. Some of

the larger craters are over two miles in

diameter, and some even overlap, ITve

been told. ~That was ten years ago, and

we still have to wear radiation counters.

Right now, O.K. and I are on the eastern

seaboard near Norfolk. We are the

advance scouts for a presidential visit to

this area. Right now, that doesnTt look

like a very good idea. WeTre trying to stay

alive and keep some other people that

way too. BIG job at the present time.

Six and a half years ago our ofriends�

from down south decided that it was a

good time to go north for a visit. I guess

they thought we were easy pickings. We

were at first. ~The west coast surrendered

without a fight. ~The military had been

decimated by Congress and our

draft-dodger president. Ineptitude and

stupidity ran rampant throughout our

government back then.

Things are run a lot differently now. We

donTt have as many people, so everyone

has to do more. ~The presidency is still a

four year job, and we elect our presidents

by popular vote. If the vote is close or

equal, we have a run-off election. The last

democracy is still working even if the pres-

ident we have now doesnTt have a lot of

the country left to work with, but she does

have great legs... and us. I point and signal

to O.K., oYou take the left and Ill take the

right. ~Tell those weenies to stay away from

the windows! Meet me back here in five

mikes ready to go.� O.K. wearily signs he

understands and disappears into the confu-

sion of the area headquarters.

The U.S.A. that ITm fighting for consists

of the old New England states and most

of the old Confederate states. We are all

on the same side this time. Most of us

are former military people, from all the

branches of service, plus anyone else who

thinks they can make a difference. |

guess we could be called freedom fight-

ers, for lack of a better term. At least that

title is repeatable in mixed company. Our

official status is outlaw, as declared by

the former friends from down south, who

also claim to represent the U.S.A. now.

Yes, we still have around some people

who refuse to learn, but they are dwin-

dling fast, just like that major. Really stu-

pid of him to stand in front of the windows

while telling us a hostile sniper team was

suspected in the area. He was right; there

is. Now itTs our job to root them out.

O.K. got his name from the fact that

ook� is just about all he says to everyone,

except me. I found him about four years

ago down in ~Texas when it still belonged to

us. His family had been killed by reavers. I

asked him if he wanted to stay with me

until we got to some place where people

Cc o = ov g &-. ° o rr�

ould take care of him. He said, oO.K.

H _ . A

eTs still with me, learning the trade.

Not that it matters much, but ITm an old

man who happened to get caught up in

something he didnTt want anything to do

with. lhe raiders came, just like the old-

me pirates used to. I didnTt get home

until after they'd left. I'd been out hunt-

ine and was bringing home.a nice buck

I'd spotted a couple of days earlier. I

havenTt gone back since I left that day.

ITve been described as an old man with

hard eyes that go all the way to his heart.

Maybe I am. The passion is gone now,

but the banked fire of my anger still

smolders deep inside. Someday itTs going

8 kill me, but I wonTt be going alone.

Somebody, I donTt remember who, once

"" that I had 134 reported kills. I

" t know. I never counted them,

oe my sleep when they come to

= hey donTt stay very long though.

ri ange kills them, as I did in life. ~They

on't count anymore. Only the ones still

out there - :

there count, but not for much.

O.K. and I leave the headquarters

"" a window near the back on the

eft side of the building. The side with

Ki cover. We figure that since the

snipers are good enough to get here and