[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

=

=

oO

4

UV

Ke

n

uu

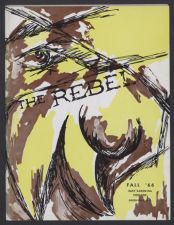

VOLUME X FALL, 1966 NUMBER 1

THE REBEL

ART PORTFOLIO 31

CONTRIBUTORST NOTES 48

DRAMA

The Fiend by Nancie Allen 4

EDITORIAL 3

ESSAY

Functions of Religious Language by Houston Craighead, Jr. 22

FEATURES

Interview with Dr. Thomas J. J. Altizer 11

Interview with Dr. John C. Bennett 14

Photographic Essay by Henry Townsend ab

FICTION

Wintertime and Not One Posy by Worth Kitson 28

The Gift by Ronald Watson 37

POETRY

Ode to Baie de Touraine by Guy le Mare 9

Rue 21 by Pam Honaker 16

Asha Yeats by Pam Honaker 26

I Became a Leaf 27

CMF Because by Pam Honaker 27

Teod by Guy le Mare 27

Protest #1 by Brenda Hines 30

Protest #2 by Brenda Hines 30

Eel Grass by Pam Honaker 40

Poems by Worth Kitson and Lola Johnson Al

REBEL REVIEW

Reviews by Dr. Henry C. Ferrell, Ronald Watson, and Pat

Wilson 44

COVER

By Cherry Parsons

THE REBEL is published by the Student Government Association

of East Carolina College. It was created by the Publitations Board

of East Carolina College as a literary magazine to be edited by stu-

dents and designed for the publication of student material.

Contributions to THE REBEL should be directed to P. O. Box 2486

E.C.C., Greenville, North Carolina. Editorial and business offices are

located at 300 Old Austin Building. Manuscripts and art work sub-

mitted by mail should be accompanied by a self-addressed envelope

and return postage. The publishers assume no responsibility for the

return of manuscripts or art work.

Copyright applied for, 1966

STAFF

EDITORIAL LAYOUT

RON WATSON, Editor MaArGo TEU, Editor

BETTIE ADAMS, Associate Editor CARYOL WRIGHT, Assistant

PAT WILSON, Assistant Editor

CAROLYN MADDREY, Book Review Editor

PEGGY TAYLOR, Poetry Editor

BILL RUFTY, Fiction Editor

SANDY THOMAS, Exchange Editor

JOANNA MUZINICH, Critic

BUSINESS

HENRY TOWNSEND, Business Manager

DAVID CROTTS, Assistant

ALAN MERRIL, Assistant

GENERAL

KATHY REECE

BETSY CHICKERING, Editor BRENDA HINES

CHERRY PARSON, Assistant PAM MCKITRICK

LisA HATCH PAM HONAKER

DIANA HOOPER BECKY BROWN

LYNN PORTER

ADVISOR

OVID PIERCE MEMBER ASSOCIATED COLLEGIATE PRESS

2 THE REBEL

EDITORIAL....

RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL

The forthcoming session of the North Carolina

General Assembly will decide the immediate fu-

ture of East Carolina. For nearly a year East

Carolina has been campaigning for independent

university status. Although opposition has been

heavy, particularly from the Piedmont and from

the Consolidated University proponents, support

has been strong from the Coastal Plains section of

the state. And the outcome may also depend upon

such diverse subjects as liquor-by-the-drink and

reapportionment.

East Carolina has been fortunate to have a uni-

fied approach to independent university status.

The students, faculty, administration, and board

of trustees have all been in relative agreement as

to our goals. One wonders, however, if all of the

above are aware of the responsibility involved in

being a university.

The administration seems to be the best prepar-

ed to accept university status. Despite the tradi-

tional cries of oinefficiency,� oultra-conservative,�

and obiased against students,� they are probably

one of the best prepared administrations in the

country for the transition from college to univer-

sity. Their main weakness is the lack of institut-

ing certain academic programs in certain areas.

East Carolina is in definite need of a full seminar

program, a reading week, and a hard-core honors

program. These programs can come only from

the administration. Hence, it is the responsibility

of the administration to institute them if the need

exists.

Our faculty may be a more serious problem.

To some persons a tendency exists to accept less

than college standards. Some students believe that

many faculty members take a legalistic, or too

rigid approach in the humanities. Others feel that

FALL, 1966

entirely too many objective tests, such as true-

false, multiple-choice, and fill-in-the-blank are be-

ing used, but it must be said that this problem is

universal. And still others feel that essay or sub-

jective tests are being graded too easily. Whether

or not any or all of these complaints are justified,

the faculty must continuously evaluate itself and

be aware of the possibility that these complaints

may be true. If academic excellence is a reality

at East Carolina College, it is the faculty that must

maintain and require it from the student.

Easily the least prepared, however, for uni-

versity status is the student. Many students at

East Carolina do nothing more than just barely

get by. We have no interest in academic communi-

ties. We do not take advantage of the cultural and

academic affairs that are present. We seem afraid

to enter into a faculty-student relationship. In

short, we are in an apathetic daze of non-entity"

afraid to see and afraid to be seen. While the

reputation of a school may depend on its faculty,

its worth depends on its students. If we are to

become a real university and not one in name only,

the students must accept the ultimate responsi-

bility.

We seek to become a university, and well we

should. The time will never be better than the

present. Many of the above faults are being elim-

inated while many others will take time to correct.

The process of becoming a university is neither

easy nor fast. But, the Consolidated University

and the Piedmont newspapers notwithstanding,

we are ready. Being ready is only the beginning,

however. If we are to be the great institution

that we seek to be, we must be ever-improving,

ever-changing, and ever-progressing. And that

we must be always.

EDITOR

THE FIEND

First Place Fiction

by

Nancie Allen

Cast: Paige, a college student/ Kelly, PaigeTs

roommate/ Angela, PaigeTs friend/ College Boys:

Van, Frank, Cory, Ted/ LadiesT Club: Eleanor,

Mamie, Grey, Lettice, Dana/ Jock, an artist/

Helena, JockTs wife/ Carwana, PaigeTs aunt/ Jan-

itor.

Time: The present, in the evening.

Place: The lobby of an art museum, shortly

before closing time.

KELLY: (Looking bored) Hey, Paige, how much

longer are we going to have to sit here?

PAIGE: Till Aunt Carwana comes.

ANGELA: Why?

PAIGE: Because she said to wait here in the

parlor until she finishes her trustee meeting.

KELLY: YouTre not going to leave your painting

up for her to see, are you?

ANGELA: She has to leave it up until the exhi-

bitionTs over.

PAIGE: Yes.

KELLY: Gee, Paige. You heard your aunt. She

told you not to exhibit. She told you to enroll in

Physics 101.

PAIGE: (Returns to sofa) I know.

KELLY: ITve got an idea. (Rises, goes toward

picture as soon as the exhibit is over) ITll grab the

painting and fly with it to our room, Paige.

ANGELA: But thereTs no need to, Kelly. It

isnTt signed. Paige, your aunt wouldnTt know it

in a million years. (Moves to other pictures.)

PAIGE: Believe me"sheTd know. Carwana has

a sixth sense.

KELLY: (Returning to her chair) Gravy. Sup-

pose the trustee meeting beats the exhibition to

the finish?

ANGELA: Kelly, youTre a worry wart. ItTll take

her aunt hours to put that speaker ban through.

KELLY: I understand. Win or no hundred-

thousand dollar gift to the college.

PAIGE: No, no. ItTs not that at all. ItTs not

CarwanaTs money. ItTs her. ItTs her force and

persuasiveness that moves people.

ANGELA: But when itTs irresistible force against

immovable objects"

PAIGE: CarwanaTs generous. Why, just last

month she donated a new wing to Lefentante Gen-

eral Hospital.

KELLY: O.K., O.K. (Angela walks to the door

and looks out.)

ANGELA: (Moving to center stage) I donTt

see anybody. Sure is quiet.

KELLY: Hey, letTs go, Paige.

PAIGE: No, ITve got to wait for her. But you

and Angela can leave. I know youTve got things

to do.

(Angela and Kelly exchange glances. Angela

returns to the chair.)

ANGELA: We'll wait. But the exhibition is

bound to be over by now. We havenTt seen any

viewers for an hour. (Begins rummaging in her

purse for a half-eaten apple.)

KELLY: This is like sitting up with a corpse.

PAIGE: Is it that bad?

KELLY: (Apologetic) ITm sorry, Paige, I did-

nTt mean it the way it sounded. ITm keeping my

fingers crossed that it will win. (Angela rises,

walks over to the painting at center, stands star-

ing at it.)

THE REBEL

FALL, 1966

ANGELA: (after a pause)

Kelly?

KELLY: oThe Fiend.T (Bends over to read in-

scription) oThe Fiend.�

ANGELA: But itTs so much more.

KELLY: Why is it called oThe Fiend?�

PAIGE: You know why, Kelly.

KELLY: Well, I know your Aunt Carwana calls

abstract art fiendish. But"

ANGELA: ThereTs a chained spirit, struggling

to be free"

KELLY: WhatTs his fright?

ANGELA: Himself, maybe. (Exchanges glances

with Paige, slowly walking to front stage center)

ItTs all the proud tyrants. ItTs the brightest angel.

And despite the false pride which seems forever

to chain man to the cloak of darkness, there is al-

ways the stirrings toward light"toward the morn-

ing star.

PAIGE: Angela.

ANGELA: Yes, Paige, I see all that in oThe

Fiend.� And what I see is beautiful. (Paige and

Angela exchange glances and both smile.)

What do you see,

ANGELA: (Looking at watch abruptly) I do

have to go. Good-bye, Kelly. (Leaves without

purse)

KELLY: Bye.

ANGELA: (Returning to get purse) Oh, Paige,

ITm proud of you. Good-bye. (Angela leaves. Paige

smiles. )

KELLY: (Rising and going to sit beside Paige

on sofa) Paige, I do want you to win. When the

judgesT decision is made, I hope it will be: oThe

Fiend,� unsigned, winner of the tuition grant.

Why, then youTd be free"free of your aunt and

you could paint your abstracts in spite of her ban.

PAIGE: (Rising to front stage center) Well,

whatever happens, I know I have to create. (Wist-

fully) At night I dream, and in the morning my

hands move over the canvas, putting my dreams

there! You do see, donTt you? (Moves across stage

to back of chair)

KELLY: Have you ever stopped to think that

maybe your aunt wouldnTt be so opposed to your

taking art if you painted scenes from nature"

trees and birds and stuff like that"art that says

something?

PAIGE: I paint asT I feel"I have to, Kelly.

ThereTs so much beyond the canvas.

KELLY: (Warningly) Sh! Guess the exhibition

isnTt over. Here come three guys.

PAIGE: Come over here to sit down. LetTs pre-

tend weTre just viewers.

KELLY: (Nodding, she moves quickly to the

other chair. Four college boys enter. One remains

silent throughout the scene, they are typically

campus types. They go to PaigeTs painting and

stare at it.)

VAN: Hey, Man! This is what I call gone. ItTs

the wildest.

FRANK: ItTs a scarecrow if you ask me.

VAN: No, Man. ItTs my Uncle Lamas. Exactly

his expression when I ask him for more cash.

Cory: Ah, fellows, you just donTt appreciate

art. (The other two boys groan.)

FRANK: Well, pal, I appreciate art that looks

like art. This thing must be a joke.

VAN: A poor joke, Man.

Cory: I see a struggle.

FRANK: Yeah, yeah. (Reads title) It says oThe

Fiend.� (Steps back.) Some fiend, isnTt it, Van?

VAN: Oh man! A fiend! How terribly horrid.

(Putting on an act) ITm so frightened.

FRANK: My gal knows it isnTt safe to be around

a fiend.

Cory: O. K., you clowns.

VAN: Oh! Frank, heTs going to sic the fiend

on us! LetTs fly.

FRANK: Yeah. (Van, Frank, Ted leave)

CoRY: Come on, you goons. A lot of people

may be in this painting, the same as me. I hope

this painting wins.

VAN: Man, old Cory is nuts"nuts! (The boys

leave)

KELLY: Ah, wise guys. (She moves slowly to

stand before oThe Fiend,� looking searchingly at

it.)

PAIGE: (Follows Kelly, observes her concentra-

tion) What now?

KELLY: ITm looking for myself.

PAIGE: Oh?

KELLY: The one called Cory saw himself.

PAIGE: He did, didnTt he?

KELLY: (Returning to face Paige) Paige, how

much does your art really mean to you?

PAIGE: ItTs my life. Oh, if you just knew what

itTs like to create colors and lines and form, to

make them speak for you"

KELLY: Your aunt says youTve got to be a doc-

tor. And sheTs paying the bills.

PAIGE: Art is my life.

KELLY: If it comes to a showdown, what about

tuition ?

PAIGE: Tuition?

KELLY: Would you wash dishes for art, wait on

tables?

PAIGE: Well, there are grants.

KELLY: (Warningly) Here come some women.

More viewers. (Paige motions for Kelly to again

be seated. Four or five women, mostly middle-

THE REBEL

aged, enter chattering.)

ELEANOR: Wonder if weTre the only club"

(Spies girls, calls out to them.) Girls, have any

other clubs attended the exhibition?

KELLY: HavenTt any idea. (The girls withdraw

among the paintings.)

GREY: (Pointing to ~The FiendT) This one,

Lettice! (Thumbing through her notes) Abstract

"abstract. (Finds it) Ah, yes. Abstraction, as

you know, can be defined as the abstract qualities

that exist in every form of art. (Consults notes)

Contemporary abstract painting is devoted to

these values. Objects and form are broken up in

this art form.

MAMIE: Grey knows so much about abstract

art.

ELEANOR: What is it called?

GREY: oThe Fiend.�

LERRICE: ItTs cute.

MAMIE: IsnTt it darling! I just love abstract

art.

ELEANOR: I do too. Look at those colors.

LETTICE: So symbolic of a friend.

GREY: ItTs oThe FiendT, Lettice. Not friend.

(Lettice shrugs and returns to realistic paintings,

takes a look at the title.)

MAMIE: This gets my vote. TCourse, ITm not a

judge.

ELEANOR: Mine, too. ItTs the only abstract I

see. ITm for abstract art!

MAMIE: Oh, I am too. (Mild pause) I want

some coffee. (Dana enters)

DANA: So here you are, girls. ITm late, I know.

But ITve had some thinking to do, and I decided to

take a quiet stroll around the campus.

MAMIE: Eleanor and I are going on for coffee.

GREY: All right.

(Two women leave. Grey continues) Now, donTt

tell me, Dana. YouTre still undecided about your

vote.

DANA: Yes, Grey. I never rush into anything.

GREY: YouTve had plenty of time. ItTs not that

much to it. We are only voting on whether to put

pansies or peonies around Benjethy CartwellTs

statue.

DANA: Every issue is important, and this one

is especially so.

LETTICE: Now, thatTs nice, Dana. ITm always

rushing into everything. I just donTt think too

much.

(Dana looks at the paintings and spies oThe >

Fiend.TT)

DANA: (Aloud) Hey"(There is a note of rec-

ognition in her voice.)

LETTICE: What?

FALL, 1966

(Dana walks closer to the painting and smiles.)

DANA: Now thatTs unusual!

GREY: You mean that abstract thing?

LETTICE: I think itTs cute.

DANA: Revealing.

GREY: It reveals what?

DANA: CanTt you see it?

LETTICE: Well, I donTt see anything.

DANA: I see a prisoner trying to escape.

GREY: I see colors .

LETTICE: Oh, dear"lItTs time to vote. Come

girls). Anyway, I donTt understand your talk"

something escaped indeed.

DANA: Although you two donTt see it, it does

make sense to me. (Three women leave.)

PAIGE: (Looking at her painting, then to Kelly)

ITm looking for something.

KELLY: Yes?

PAIGE: For myself.

KELLY: Oh. (Seeing two viewers entering at

front, Paige goes to back of sofa.)

(Jock, a young man in his late twenties, enters

with Helena, his wife, a woman impeccably groom-

ed and richly dressed. Jock is the conventional

garret-type artist, a pose he cultivates according

to HelenaTs specifications. Jock breaks away from

her and moves quickly to oThe Fiend,� and is ab-

sorbed by it.)

Jock: (After much thought, breathing out ec-

static approval) This is"This is"

HELENA: ItTs monstrous. ItTs the worst thing

ITve ever been subjected to. And youTve dragged

me around to see some pretty bad art.

Jock: Will I never be able to show you, Helena.

Things you need to know are spread right here

on this canvas. ITve got to buy this painting.

HELENA: You'll do nothing of the kind.

JocK: But ITve got to have it.

HELENA: And where would you get the money

to pay for this terror?

JOCK: ITd get it.

HELENA: I wouldnTt give you five cents to buy

the likes of this.

JocK: (Musingly) If I had looked at this often

enough"these chains"Why I might have broken

away from my lesser self.

HELENA: Come on, Jock. (She pulls him with

her.) YouTre under contract to Father, you know.

The azaleas for my solarium, and then"

JocK: (Looking back) But thatTs how I want

to paint"in symbols.

HELENA: Not with my money! If you want

money for this painting, go dig a ditch! (Exits)

Jock: (Sighing, shrugging) Back to the aza-

leas. (Exits)

KELLY: Can you beat that"heTs not even strain-

ing against the leash!

PAIGE: But starvation is very real, Kelly. It

does take money.

KELLY: He could dig ditches, couldnTt he?

(A judge walks in and pins a blue ribbon on

oFlowers�, then exits)

KELLY: You lost, Paige. ITm sorry. oFlowers�

by Harley Devaris.

PAIGE: Did I? Did I lose?

KELLY: You saw the judge.

VQICE: (Outside) Paige! Paige Reed!

PAIGE: ThatTs Aunt Carwana.

KELLY: (Rushing over to picture oThe FiendT,

starts to take it down.) ITll take it up to our room

before she sees it.

PAIGE: (Quickly) No, leave it.

KELLY: But her ban"

PAIGE: Leave it.

KELLY: O. K. (She starts for the door) ITll be

back.

(After KellyTs exit, Aunt Carwana strides in.

She is an impressive woman, well-dressed, the tail-

ored type. She heads at once for the sofa.)

CARWANA: So here you are, Paige. Ohhhh!

ITm tired. (She sits.) Paige, what a taxing day!

PAIGE: You must have read the announcement,

Aunt Carwana. I exhibited.

CARWANA: What? You didnTt!

PAIGE: Yes, I exhibited oThe Fiend.� I lost.

oFlowers� won.

CARWANA: Well, never mind. ITm going to over-

look it. I know what ITll do. ITll take you and your

roommate out to Carte Inn. How does that sound?

PAIGE: ITm sorry, Aunt Carwana, but Kelly and

I will be busy during the dinner hour.

CARWANA: Oh, JTll attend to that. You'll be

glad to know J won. The speaker ban was finally

passed, a victory for the forces of right.

PAIGE: ITm not glad, Aunt Carwana.

CARWANA: I fought so hard for this ban, and

you are against me?

PAIGE: I am not against you, Aunt Carwana.

But I am for free speech.

CARWANA: I never heard you talk like this be-

fore.

PAIGE: I havenTt been saying what I think.

Now I must. Because of oThe Fiend.�

CARWANA: What? (Paige rises, moves over to

the painting.)

PAIGE: (Pleading) Aunt Carwana, look at my

picture. And tell me what you see. (Carwana

sits undecided an instant, then rises and walks

over to the painting.)

PAIGE: Do you see me in it? Or"or yourself?

CARWANA: Heaven forbid!

PAIGE: But you do see thereTs a chained spirit,

struggling to be free?

CARWANA: (Turning back to her chair) How

absurd! I do know that ITm ashamed that it bears

the name of Reed. Now will you give up this folly,

this fiendish art, and follow the sensible plan for

your ife?

PAIGE: No.

CARWANA: (Rising and thinking) Then I will

have to withdraw all support.

PAIGE: I do appreciate the help you have given

me.

CARWANA: (Sternly) ItTs over. ITm through

with you. Do you realize what that means?

PAIGE: Yes.

CARWANA: (Changing to a softer tone) What

will you do? Starve?

PAIGE: ITll wash dishes, wait on tables" (They

look at each other. Neither flinches.)

CARWANA: (After a pause) Where is your

pride? (Pause) What of my pride. I was going

to make you the best doctor Reed Hospital ever

had! Change your mind and come with me now.

PAIGE: No.

CARWANA: (Long Pause) Please! (Paige nods

her refusal. Carwana squares her shoulders.)

Goodbye, Paige.

PAIGE: Goodbye, Aunt Carwana.

walks toward sofa, begins crying.)

(A Janitor comes on stage and sweeps floor,

moving quickly across floor. He notices Paige,

continues to sweep and then stops and curiously

stares as Paige rises.)

PAIGE: Fiend, they say we lost today. But we

won, too, and Tomorrow" (She is suddenly star-

tled as she sees tears in the FiendTs eyes.) Why,

Fiend, you are crying. There are tears in your

eyes, as though theyTre reflecting light. DonTt

weep. YouTre breaking the chains. YouTre emerg-

ing.

(As Paige stands gazing in wonder at her paint-

ing, Kelly quietly re-enters and stands near her

friend.)

KELLY: ITm here Paige. Can I help?

PAIGE: (Without looking at Kelly) Kelly, look.

The dark pride dissolving in tears . . . the eyes

turning toward the light . . . DonTt you see the

tears in those eyes?

KELLY: (Very gently) Yes.

(Kelly takes Kleexex and wipes the tears out

of PaigeTs eyes as all lights fade out except one

dim spot on the janitor, who stands puzzled for a

moment, shrugs shoulders, and then sweeps on off

stage.)

(Carwana

THE REBEL

Ode to Baie de Courane LL

The time has come for dawn at the forlorn

Entombment of civility. White sails

Announce the coming of the junks as they =

Seurry across the glistening bay. Wispy © ae

Clouds start to move in endless procession""==" :;

To the waiting sea. Light reflécts from the ~ ~~

Shrouded mountains and strikes gentle

Ripples as they traverse the war-torn bay.

The dawn brings new life to the hordes of men

That are encamped around the slopes of the

Encircling mountains. Another day

Awakes anew the cries of death, the smell

Of guns, the sense of loss. Only the bay

Remains impervious to the drama.

Oh, bay of such exuding calm, can not

You tell us your secret? Your eyes have-seen

The depths of Man; there surely must :

Exist a way to end this-foolishTstrife. -"/

Tell us what we must do beforeTs too late

To hope for naught but death, The Eternal.

Dusk closes around the bay as sun and light

Retreat beyond the ring of stone and earth

That man has called mountains. The wind bre

Still answer to his tortured question. But

Man sleeps in ignorance, not ever to

Know that the bay and earth endure al

While man is but a brief, small dot

The infinite life spectrum Nature

aT

FALL, 1966 9

THE REBEL

One of the chief topics of discussion among both

clergy and laymen alike is the current theology

which proclaims the death of God. In seminaries,

in churches, and in the colleges throughout the

country, deep discussion and debate rages over the

subject. Is God dead or is He alive? The Rebel

interviewed two of the leading men in each of these

fields: Dr. Thomas J. J. Altizer of Emory Univer-

sity, Atlanta, Georgia, who is a oGod-is-dead�T

theologian, and Dr. John C. Bennett, President,

Union Theological Seminary, New York City, a

S oGod-is-alive� theologian. Their observations and

remarks in this contrasting interview reveal very

clearly two positions of current theology. (The

boldface type indicates a member of the Rebel staff

speaking.)

GOD

The first question we have for you is exactly

what do you mean by the oDeath of God�?

Most fundamentally, I believe that the God who

is manifest and revealed in the Bible and in the

Christian faith as the transcendant Lord and the

sovereign creator has died, and that God is no

longer actual and real. In this faith today, we can

know his death as a full manifestation and incar-

D Jef D Pe nation of the sum of Christ.

wes © Does the Death of God Movement have a future

in Christianity?

Of course, because as I understand it, it is only

the Christian who truly knows the death of God,

and the death of God is a full manifestation of the

Christian faith itself, and that it is only the Chris-

tian who can truly live and rejoice in the death

of God.

Who, or what might be a better question, takes

the place of God in the new theology?

As a whole, as I see it, I would say, what is hap-

pening here decisively is that Christ is becoming

the full and only center of things and that this is

a form that understands Christ as being totally

present now, present in such a way as to appear as

a consequence of the Death of the Transcendant

Lord.

Dr. Altizer, when did God die?

FALL, 1966 11

Well, as I understand it, God died most funda-

mentally, most primarily by becoming incarnate

and by dying on the cross and that the original

death of God on the cross occurred in the individ-

ual Jesus Christ, in the original form of Christ,

and has since then slowly, but very decisively, be-

come natural, manifest, and real in history, in

consciousness, in experience, so that now, that

original death of God is manifest and real to every

man who lives in our history and in the contempo-

rary movement of our history.

Does this mean that God did this voluntarily

or was it a necessary act on His part, or just what

exactly was the motivation behind it?

Of course I couldnTt, and donTt really think any

theologian could give a motivation of God. But I

think that we can say that this act of self-dissolu-

tion and self-negation occurred to actualize the

total form of redemption and of life.

I have heard one word and seen one word con-

stantly in articles referring to the Death of God

theology. The key word is responsibility. As I

understand it, man becomes responsible for many,

many of his actions, he takes the plain and full

responsibility for what he does. If this is true, is

man capable of accepting this responsibility?

That is a very good question: is man capable of

it? But on the other hand, I think that man must

be capable of it. There is no hope unless he can

accept this responsibility. But any form of hu-

man dependence upon an outsider, or transceind-

ant, or distant other in our time is either becom-

ing impossible or repressive or self-negating. I

should say that it is only in so far as man can

assume in some sense a genuine and full and total

responsibility that he can truly be alive and live in

our generation.

Dr. Altizer, do you believe in an after-life ac-

cording to the orthodox Christian view?

No, and by the way, I donTt believe that many

theologians do; that is to say that the Christian

and common idea of personal immortality never

was a true component of Christian faith; it is in

origin and in nature fundamentally pagan and

non-Christian. I believe on the contrary that it is

only in so far as we pass through an actualized

death ourselves thatT we can undergo a union with

Christ. Now this doesnTt mean, however, that

there is no hope for the future. I think that the

hope for the future is in the triumph of the body,

the total body, the total reality of Christ in which

every form of life and energy, we trust and hope,

will appear to be real, even if it is transfigured and

non-individual and non-ego.

12

Dr. Altizer, can the Death of God theology have

a positive effect on Christianity as we know it, or

does the church fundamentally need to change its

organization, structure, and outlook?

Again, I think that the church is already funda-

metnally changing its structure, faith, and outlook.

This process is rather well-advanced, and must,

of course, continue, move ever forward in a more

comprehensive and radical direction. We can see

this in the Vatican II and the changes that are

sweeping the Roman Catholic Church. Also, I

think in many of the frontiers of Protestantism

and in everything we have traditionally known as

the Church, as worship, as witness, and as Chris-

tian life, most pass through a radical change, a

radical reformation.

Dr. Altizer, do you foresee the possibility of

yourself being called a conservative?

Yes. As a matter of fact, I already am called

a conservative by some, and, I can imagine as

time goes on, I will increasingly be so identified

unless I go further to the left than I already have.

In our talk with Dr. John C. Bennett, President

of Union Theological Seminary, he seemed to

think that the Death of God Movement, although

having very positive effects on the church and

Christianity today, is just another passing phase

of theology that has no substantial hope for any

real grounds in the future. How do you view

this?

Well, it is very difficult to predict the future.

I think that I would agree that it is certainly a

passing phase in theology. However, I believe

that all theological expressions are passing phases

in theology. There is no such thing as a form of

theology that can perpetuate itself indefinitely. To

the extent that it does, it is a sickness in theology

or in the phase of it. However, it is my belief that

the Death of God theology is the expression of a

movement that is going to transform theological

thinking. Even though it may be a minor expres-

sion, I think it is a genuine expression, certainly

in terms of theological options at hand which are

very, very few. One of the problems in the theol-

ogy of the last generation is that it has been so

dead. There has been almost nothing happening

of any substance in the theological world for a

whole generation. I mean that all the major theo-

logical work was done in the twentieth century

by men who are either dead or in their seventies.

We have been living in a theological void for the

past generation, and we are now beginning to

move out of it.

Dr. Altizer, are there many theologians or

philosophers who have influenced your theology?

THE REBEL

Oh, a great many. It seems to me that I have

tried to give witness to the major ones in my

works. Do you mean contemporary theologians,

or what do you mean?

Yes, contemporary theologians.

Yes. Well, I have certainly been influenced by

Paul Tillich, although I donTt know whether you

should call him contemporary since he is dead. I

have also been influenced by Rudolf Bultmann and,

for that matter, by Karl Barth, Heidegger, Sartre,

and by a great number of literary critics and

others.

Many theologians I have talked to feel that Bon-

hoeffer very possibly was the one who, you might

say, started this theological direction. Is this

true, and as such, has he had any influence on

you, or has it just been a passing influence?

Well, I think it is true that he does belong at

the fountainhead of this movement. It just so

happens that I, myself, was not decisively affected

by him simply because I had, in effect, reached my

position before I had read the late papers of Bon-

hoeffer. But, nonetheless, I certainly would place

him at the forefront of this movement, meaning

more particularly, his late papers and not his

earlier theological work.

Dr. Altizer, usually when we hear of the Death

of God theology, it is in relation to you and Wil-

liam Hamilton. Is this a growing movement now

in this country and are more theologians joining

with you in this approach to theology?

I think that it definitely is a growing movement

and that more theologians are publicly associating

themselves with the movement. I think that theo-

logians have been doing this kind of work for

themselves and in many cases, or in some cases,

for many years. There are a number of theolo-

gians that one can now say are publicly identified

with the Death of God movement. However, one

of the problems today is that we donTt have much

communication. There is no such thing as a

national theological society in this country. There

is no way by which we can meet under normal cir-

cumstances. Communications are not good. We

are trying to correct this to some extent. How-

ever, in terms of this Death of God Movement,

there is something for the public that is a recent

event, and I think that it is going to take a little

while before we can have any objective knowledge

of how broad a movement it is in American theol-

ogy. But I do think that there are a significant

number of theologians who, by one means or an-

other, are practicing the Death of God theology,

the radical theology, or are thinking in these terms

and working in these terms.

FALL, 1966

Dr. Altizer, does the phrase ototality of man�

have any significance in the new theology?

Well, it certainly could have, depending on what

one means, of course. I would interpret it in some

sense as meaning a particular totality of man re-

leased in this era, in our time and that man has

opened himself to total existence of the flesh and

the here and now of immediate existence. There

is a new kind of total humanity. There have been

other kinds before, of course, but I mean the

classic paradise of a totality of humanity ; the mys-

tical one when man exists totally in and as a pre-

mordial, external being. Now I think that we are

seeing the opposite of that. We are seeing a new

paradise of a totality of humanity which is exist-

ing here and now time and flesh and in the im-

mediary of GodTs great existence.

You have mentioned that you have been influ-

enced in the field of literature quite a bit. Who

are some of the figures in literature who have in-

fluenced you and why?

You mean writers primarily?

Yes sir.

Well, a great many. One is William Blake, but

I have been decisively affected, and I think most

theologians have, by Dostoevsky. Among mod-

ern writers I would include Proust (Hrothgar),

Joyce, and even to some extent by Eliot and Yeats.

Also, I have been very much affected by literary

critics. I suppose the most recent literary critic

who has decisively influenced me is Northrop

Frye.

One last question, Dr. Altizer. Henry, you have

an analogy. Would you mind mentioning that

analogy and checking its validity?

The analogy was that given the situation where

two parents have a child and, for some reason,

this child is threatened and the parents choose to

give their lives voluntarily for this child. This

puts the child in the position where the only in-

fluence the parents have over him is memory of

his teachings, what they have taught him in the

past. They have no direct, present influence,

realistically speaking. Would you say that this is

analogous to what the Death of God theology is

talking about?

In part, but only in part. I would also want to

say that, if you are willing to stretch it biologically,

if we are to stick to the analogy, in some sense

through the death, the predetermined death of the

parents, their life is present in the child in a new

form. It is not in just the teachings or even the

love which is a model for the child, but in a very

real sense, their life and energy are now present

and real inside, within, at the center of the child.

13

Seavert

Doctor Bennett, although this question has

been asked many, many times, usually on the

other side of the fence, what does the Death of

God Movement mean to you?

Well, I think that it means that a great many

people are disillusioned about Christian faith as a

reality as they have understood it, that the sym-

bols about God, the images of God, are no longer

convincing, and also that there is a very great

sense of the absence of God in the real world, a

tragic world in which there is so much evil, that

it is hard to point to the actual activity of God in

this world. Now one of the characteristics of the

Death of God movement, the most important, is

that it is a movement within the church, within the

Christian circle, quite honestly so. These people

believe that there can be a different statement of

what Christianity means, in the sense of a God

who transcends the world. And they do this by

emphasizing, very much, Jesus Christ. This means

that they seek to be a Christian group or Christian

individuals, and to a very large extent Christ

seems to take the place of God.

Well, the word oGod� is, of course, tossed about

rather freely and quite often. Attempting to de-

fine the undefinable, could you give a limited con-

cept of God?

Well, I think the concept of God that represents

the main tradition is that God is the creator, He

is independent of the world, the world depends up-

on him, and God is present as an active redeemer

as well as a creative force in the world. God, from

the Christian standpoint, is never just humanity

seen in a different light, but God transcends hu-

manity, judges humanity and also seeks to trans-

form humanity. Now it seems to me that what

the Death of God people do is to locate God, or

locate what is to them the supreme object of the

faith and obedience in Christ as a man in the first

century. I think this is so very largely so in the

case of Hamilton. With Altizer I think it is rather

different. There is some sense of the living Christ

14

and the Holy Spirit becoming a reality in the world

which is the equivalent or does duty to a consider-

able extent to what some people use the word

oGod� to describe or to designate.

Dr. Bennett, do you believe that the death of

God can have constructive results on the modern

Christian Church?

Well, I think so. I think anything that shocks

people so that they look at their thinking, look at

the things they have taken for granted, and find

new ways of expressing what they mean is to the

good. Why, there will undoubtedly be a lot of

people who will be hurt in the sense that their

faith will be shaken by it within the church and

they may give up any relationship to the Christian

faith. Actually, the Death of God theologians,

because of their very great emphasis on Jesus, are

not likely to leave the Christian faith. But many

people influenced by them only get the negative

side of this and they wonTt get the positive Chris-

tian side at all. There will be some loss at that

point but I think that by and large the churches

are better for being shaken up by this kind of

movement from time to time.

Is there any future for the Death of God Move-

ment? Will it last any longer than a couple of

years?

I think it is very unstable and likely to fall apart

myself. After all, everything changes anyway.

No theological movement stays put very long. I

have outlived several myself that were deemed to

have been very solid. And this is itself quite un-

stable, particularly because of the combination of

the denial of the reality of God the Father, and

the great stress upon Jesus without God the Fa-

ther. It seems to me the whole context of JesusT

life is denied.

Dr. Bennett, you have mentioned the effect of

the Death of God Movement upon the Christian

faith. What effect do you think there will be on

people who are not in the Christian faith?

I have no idea. Many of them will say oI told

you so, long ago.� And you have that reaction.

I think others will say, ~ooHere there is something

new going on in the church, letTs look at it.�

Do you think it will stimulate thinking?

Oh, yes. I think it will. It will depend on whom

they read. I think that if they are led into Bon-

hoeffer, for example, they would necessarily be led

into something that would open up all kinds of new

horizons to them.

Dr. Bennett, it seems to me that one of the

keystones of the Death of God Movement is its

belief that (1) Man is completely free"has com-

THE REBEL

plete freedom of action"and (2) that he has com-

plete responsibilities for his actions in the world.

Do you agree with this and how does this com-

pare with the more traditional forms of theology?

Well, I donTt agree with it, nor do I agree that

traditional forms of theology tend to oppress man

or leave man overwhelmed by divine power and

divine initiative. It seems to me that the carefully

stated traditional forms of theology have usually,

in all cases, have usually made a very important

place for human freedom, for the capacity for this

weak, finite, creature to resist the creator. This is

something which is taken into account in theology.

There are some extreme forms of Calvinism, to

be sure, that donTt really allow for this except

with some degree of inconsistency perhaps. On

the other hand, I think that to say that it is possi-

ble for any finite person whose life is within the

social web and who is conditioned by his own past

as we all are conditioned by our pasts, any such

person is absolutely free. I think the number of

alternatives may be enlarged; the freer man has

more alternatives to choose between, but they will

be limited. And the moment you take count of

manTs social responsibilities, then alternatives be-

come very much limited, limited because of the

past. Anyone who is talking about absolute free-

dom is talking about himself as an individual in

a vacuum.

One of the key words to me in the Death of God

Movement is the word responsibility. I would like

to ask you to take the other side of the fence for

a moment. One of the things that really bothers

me about the theology is the fact that in the con-

cept as it is developed now, there is no after-life.

To put it on finite terms, there is no reward, there

is no punishment. It seems to me that this in a

sense takes away a lot of the incentive of man.

Why should he accept such responsibility? It

would seem to me that some people I know of could

be completely evil in the traditional sense of the

word and be completely free with no bothering

about what they are doing, no fear, and to them

there is much more incentive to be evil than to

accept responsibility for their acts.

Here are you saying that people do accept re-

sponsibilities because of fear of future punish-

ment? Of course, this is basic.

Along these general lines, yes.

Well, I would think that it may well be that a

certain amount of social discipline has been main-

tained by that, and the absence of that will remove

the discipline to a certain extent. And this may

be a loss. On the other hand, on the terms of per-

sonal character, people who are responsible will

FALL, 1966

choose a better rather than a worse course. Be-

cause of the fear of future punishment, some are

doing the right things for the wrong reason. Now

in order to keep some kind of a tolerable situation

in the world it may be that a certain amount of

this is all right. But it is not a way in which

Christian character is developed. And I am won-

dering myself if this is not now present among

many citizens no matter with what their conscious

theology is concerned. There have been periods

when the fear of Hell was a very vivid experi-

ence. This was something too limited; it undoubt-

edly would bring this kind of discipline. But

today, is that very common? That vivid fear of

hell as though it were something we could imagine

as a great threat? Is that operated with the Death

of God theology or with fundamentalists? I donTt

know.

I guess what I am saying is that I believe that

man is basically selfish, not necessarily in the nor-

mal connotation of the word. But that all of his

drives, wants, his actions are basically motivated

by a selfish outlook. And if you take away any

incentive, to act justifiably to his fellowman, it

seems like this could increase to a tragic degree.

What is your concept of the after-life?

Well, I donTt have any concept of the after-life

that I could describe. I think the Christian teach-

ings about the after-life, or about the resurrection,

immortality, are ways in which it affirmed that

God is not defeated by death, by our death, and

that somehow there is meaning in our life in spite

of death. The faith, a positive faith in the face

of death is, I think, what Christianity must always

stand up for, and this comes more from faith in

God than from faith in survival.

One last question. Is there room, particular-

ly on the staff of the main conservative seminaries

for the so-called left-wing or radical theologians"

do they have a place in the seminary?

It all depends on what you mean by oconserva-

tive.� I think the answer is oYes.� I donTt think

that you would go out and find different Death of

God theologians to occupy your major chairs of

theology, but I think it is good to have such a per-

son on the faculty. What they did at Colgate-

Rochester where Professor Hamilton, who is Pro-

fessor of Theology and taught the major course

in theology, was to keep him on the faculty, and

he now teaches the Philisophy of Religion, the Re-

ligion of Literature, and probably the Hamiltonian

Theology. No, I believe that in many groups of

theological seminaries, the more conservative that

they are, the more they need somebody to shake

them up.

15

First Place Poetry

16

Rue 2]

Iam so longing...

Iam so long inlonging .. .

I am\so long in longing to belong . .,.

You follow? Must I explain again...

All right, Sport,

ITm leaving, this minute,

Keys in throbbing fist,

Crumpled HarperTs in shoulder bag,

Damp tissue in waste can

With all the rest of my dowdy,

Watered-down dreams.

And if anyone is the wiser"

I think ITm the wiser, Sport.

Not wiser than you;

I didnTt mean that:

You lie theré listening to the 7:55 news

Whilé.I go out to face

The glass-eye morality of the world,

The world steeped so far in the memory

Of lost words and empty poems

That it canTt remember

Its own little red pulsating body;

The.world too good to leave:

The green park strewn with

Do Not Walk On The Grass Signs

So easily-made into sailboats .. .

Can2t-you see, Sport, there,has to be red!

Violent; searing, plunging red

Makes.thé world go round

And the world is my oyster, Sport,

Lshall not want"

Oh, isnTt thata scream,

I shall die ITshall positively

¥ou shattered a lot more than my glass eye, Sport.

Mr. Vacanteyes, Mr. Softmouth.

But ITve had all the red I want

And ITm leaving

Just as soon as you unlock the door.

Unlock the door.

The door was locked?

PAM HONAKER

THE REBEL

The proverbial beauty which is found in the

eye of the beholder finds its most noticeable form

in beautiful women; probably no other single ob-

ject has given more satisfaction to man or been

so greatly expounded in art and literature than

has feminine beauty. With this idea in mind,

The Rebel presents a photographic essay on fem-

inine beauty . . . collegiate style, since in its col-

legiate aspects the appealing qualities of woman-

hood are no less the subject of ponderance, artistic

expression, and a great many admiring glances.

The following pictures, some candid, some posed,

attempt to display such beauty in its variety, in

its scope, and in its appeal.

FALL, 1966

ABOVE LEFT: Brenda Mizell displays a dis-

quieting effect as she waits for a friend at the

Roaring Twenties in Greenville. UPPER RIGHT:

Sweet, often fearful, always demure, Brenda rep-

resents the classic example of womanhood. LOW-

ER RIGHT: Anticipation and a touch of joy glow

in BrendaTs eyes as she sights something that

pleases her.

17

RIGHT: Connie and her

friend Joanna seem to be plan-

ning how they can best use

their feminine wiles on their

unsuspecting escorts.

18

LEFT: A night of wine and music are in the

offing as Connie House waits by the organ at the

Candlewick Inn for her lucky date. ABOVE:

Candlelight sets the mood for an enchanting eve-

ning...

and an enchanting look.

THE REBEL

i a} ty a

~

7. ta

al ai ra rt

ABOVE: Their planning done, Joanna and

Connie return to their dates, stopping for a last

minute survey of the situation. RIGHT: Joanna,

a woman of beauty, charm, and grace. Joanna, a

woman of depth and appeal. Joanna, a woman to

boost the morale of all men. And above all, Joanna,

a woman of true spohistication.

LEFT: An open hearth, a

fireplace, and who needs a fire

with the warmth of ConnieTs

smile to kindle the flame in

any heart. But nights of beau-

ty and enchantment must end,

and a slight look of nostalgia

crosses her face as an evening

of evenings comes to a close.

.

FALL, 1966 19

Although work on THE REBEL is often hectic

and hard, life for the staff also has its moments

of joy, as Margo Teu, copy editor, illustrates.

ABOVE: oWho, me?� asks Margo delightedly

when the phone rings. ABOVE RIGHT: Indeed,

Margo seems a bit out of focus as that important

someone asks for a dinner date. RIGHT: Margo

ponders for a moment the evening ahead as she

slowly replaces the telephone receiver.

20

THE REBEL

| ABOVE: Anne seems to contemplate some

course of action as she stops for a moment by one

of the many campus trees.

ABOVE: Beauty in its pur-

est form radiates from Anne

Young as she reclines on a

deserted outdoor table.

RIGHT: Anne pauses to ad-

mire the beauty of nature but

she herself has a beauty which

man cannot hope to equal.

FALL, 1966 21

contemporary

Cy

-O

sO

&

©

x,

4.

insight C

(eo)

)

hy,

Sho :

Mh,

god

xo :

ee images

Ss

Sn,

Gps

Co,

theologian

»

3 we

+ or

a N

i)

22

The

Functions

Of

Religious

Language

FIRST PLACE ESSAY

by

HOUSTON CRAIGHEAD, JR.

The purpose of religious language as the writer

conceives it is two-fold. The first purpose is really

not to say anything at all. That is, it is not to

describe to us any matter of fact. It tells a person

nothing about the world of science. It tells him

nothing about any ometaphysical beings.� It

doesnTt say or tell him anything whatever. Its

function is to show him something. In Wittgen-

steinTs phrase, the o~mysticalTT cannot be said, it

can only be shown. Religious language is, in this

sense, attempting to oshow� something. It is

attempting to produce within the listener an oin-

sight,� a oseeing into something.� It is not giv-

ing the listener any information. It is somewhat

analogous to contemporary art in this sense. That

is, just as contemporary art is not attempting to

paint accurate pictures of houses, trees, and

horses, religious language is not attempting to

give a description of the world of fact. Contempo-

rary art breaks up its subject matter and spreads

it about the canvas. A human figure may be brok-

en into many pieces, with a hand here, a leg here,

a face there, etc. This is not a picture of an actual

THE REBEL

man as he looks to the scientific observer. This is

an attempt to portray a feeling about man. It is

an attempt to create within the observer an o~in-

sight� as to just how the artist himself may feel

and as to how the artist feels about contemporary

man. Religious language is attempting something

similar to this. It is trying to produce within the

listener an oinsight� into how the speaker feels

about the world. It is trying to get the listener to

experience within his own being the same feeling.

The second function of religious language is

ointerpretative� in nature. That is, it provides a

person with a particular way to interpret or look

at his life. It suggests categories within which

it calls him to frame his approach to existence. It

takes the humming, buzzing complex of experience

and imposes upon it a certain interpretation. It

claims that if he will look at all of his experiences

in terms of these particular categories, then his

experiences will take on meaning and significance.

This paper will now attempt to explicate in

greater fullness what it means by these two func-

tions of religious language.

First of all one might say a word of justification

on behalf of the theologianTs use of language. If

the theologian is unusually vague and overly sym-

bolic, mythological, and even paradoxical and

poetic in his use of language, one ought not to be

surprised. For he has stated beforehand that

that toward which he is pointing is a mystery. In

attempting to bring the listener to a situation in

which he will have an oinsight,� the theologian is

dealing with something unlike any other type of

experience. Indeed, it is the belief of the theo-

logian that what is oprehended� (to use White-

headTs term) by the listener in such an insight is

God Himself, mysterious, ineffable, and wholly

other. As Hepburn has said: oWhatever our final

judgment, the theologian certainly deserves the

utmost logical tolerance in trying to make his

case.�

If the theologian is speaking of something su-

pernatural, how could he possibly say anything

literal about it with natural language? And clear-

ly, the only language he has is natural language.

In attempting to show something with theolog-

ical language, one will find himself using different

types of language in many different ways. He

may even assert direct contradictories. Ferre

makes a point by saying that even in his everyday

experience with the natural world, one sometimes

asserts contradictories in attempting to describe

the phenomena which confronts him. On a par-

ticuarly humid day one may say, oItTs raining and

itTs not raining.� ~Perhaps the English language

FALL, 1966

is not yet equipped to indicate the more-than-

drizzling but less-than-sprinkling condition of the

atmosphere.� So one may, at times, speak of God.

One cannot pin down exactly what he means,

what he points toward. One may want to say

that God loves us but that he does not love us.

He means that God loves us in a strange way

which is not like human love but is something like

it. One immediately asserts the contradictory in

order to point toward the ineffable which he is

attempting to get the listener to osee.�

The Bible does this. In scripture one finds the

combination of gross anthropomorphism and re-

pudiation of anthropomorphism. He finds images

and rejection of imagery. Contemporary theology

has the task of presenting its myths in a way that

these myths are meaningful when not taken in a

literal sense. One must hold the tension. He must

affirm but immediately negate nearly every point.

Ian Crombie, in his article oThe Possibility of

Religious Assertions,�T points out that in oneTs at-

tempt to show something, he uses language to ofix

the reference range� of his theological discourse.

He specifies the general limits of what we are talk-

ing about. This is done by the elimination of all

improper objects of reference (like finite things

or empirical events). He also suggests areas to

which theological language is akin, areas such as

ethics, the philosophy of history, etc. By so doing,

one points beyond his ordinary world. He negates

those omatter of factT ways of being and continues

to negate them, thus fixing the reference range of

his language as being outside these realms. Out-

side these realms he cannot say anything (that is,

give factual statements) but can point toward

something.

Ian Ramsey, in his book Religious Language,

gives several illustrations which are somewhat

analogous to what this paper is about. The most

impressive example is the one in which Ramsey

describes the situation of daily riding on the train

with a particular man and after a while coming

to know him fairly well in terms of his needs, his

actions, his responses, etc. But one day he says

offering his hand: oLook here"ITm Charles Mil-

ler.� ~At that moment there is a disclosure, an

individual becomes a persorf, the ice does not con-

tinue to melt, it breaks. He has discovered not

just one more fact to be added to those he has

been collecting day by day. There has been some

significant ~encounters,T which is not just a moving

of palm on palm, no mere correlation of mouth

noises, not just another nodding in some kind of

mutual harmony.�

A very interesting comparison can be made be-

23

tween what he is trying to say here and what Witt-

genstein said in his Tractatus. McPherson even

compares WittgensteinTs notion in that book to

Rudolf OttoTs Ideas of the Holy. In the Tractatus

the only questions about the world that can be

raised and answered are those about how the world

is. These sorts of questions fall within the do-

main of the sciences. However, the theologian is

asking a different kind of question. As Wittgen-

stein says: oNot how the world is, is the mystical,

but that it is.� (And strangely enough, Wittgen-

stein sounds a great deal like Heidegger at this

point.) Wittgenstein goes on to say that whereof

one cannot speak, one must be silent. However,

this writer would disagree with him here and say

that whereof one cannot say anything literal

thereof, one must not try to say anything literal.

But that does not mean that one cannot use words

to opoint toward� the omystical.� He may not

say anything but he has the possibility of showing

something. That is, oneTs language may be non-

sense, but it is extremely important non-sense.

There must, certainly, be some kind of criteria

for one to use in determining just what symbols

he shall use in attempting to opoint towardT�T the

omystical.� One criterion which he might pro-

pose is that the symbols should come out of his

own time. That is he would be erring if he

attempted to point with a symbol which had no

relation whatsoever to the contemporary man with

whom he is speaking. Some examples of this may

be seen in certain schools of Christian theology.

Many theologians continue to use, for instance,

the symbol of the slain lamb and its blood in con-

nection with some kind of interpretation of the

crucifixion of the Christ. This symbol bore deep

meaning for the early Jews who were well ac-

quainted with the full existential meaning of the

slaying of a lamb in sacrifice to the God whom

they feared. Contemporary man has little, if any,

comprehension whatsoever of this. One is at a

loss as to how we could possibly use the symbol of

the ~Lamb of God shedding his blood for our sins�

in any kind of meaningful way at all in our time.

This is not to say that there is no possibility for

such a symbol to call forth an oinsight,� but the

likelihood of its doing so is very small.

Perhaps a much better symbol in connection

with this particular event would be to speak of it

in terms of a Word spoken into oneTs existence

from the omystical�? which lies both within and

beyond oneTs existence. Granted that this symbol

says nothing literal whatsoever. Neither does the

one of the lamb. But one has more chance of

grasping an inclination of what is being shown

24

when he speaks in terms of a Word because he

lives in a world of great communication in which

one speaks to another in all types of conversation,

whether it be face to face or by long-distance

telephone. However, in the midst of all his fren-

zied talking, he seems to communicate very little

that is deeply meaningful. To say to one of the

20th century, who knows something of the inner

feeling of aloneness and darkness, that there has

been a Word spoken to him into his darkness,

which proclaims to him that there is the possibility

for him to live in this world is much more signifi-

cant than to say to him that the Lamb of God shed

his blood for his sins.

Another criterion which one might propose is

that the symbols used should be coherent with one

another. That is, to attempt to use symbols which

admit of no correlation whatever between one an-

other is a practice that will get one into great dif-

ficulty. For instance, it seems to be a mistake if

one attempts to unite the symbols of the philosophy

of history of the Eastern religions and those of the

Western religions. The Western religions (Chris-

tianity and Judaism) conceive of history as a

straight line, purposive, with a beginning and an

end. The Eastern religions conceive of history as

a cycle with no beginning and no end, much less

any purpose. To attempt to use both these sym-

bols in pointing toward the omystical� in history

would confuse more than illuminate the listener.

Of course, a final criterion might be whether or

not the symbol actually does its job. That is, does

it work? Are persons listening to discourse car-

ried on in terms of a particular set of symbols

really coming to ~o~see� what it is the symbols are

pointing toward?

This paper comes now to the second use of re-

ligious language: the interpretative.

Religious language omakes sense out of life.�

That is, in light of the oinsight�? which the reli-

gious persons claims to have been part of, and,

what is more, claims to, in some sense, continue

being a part of, life now takes on a new olight,�

a new perspective. Crombie points out that one

may learn much from the writings of Kafka and

Huxley, not in a literal way, but in a way which

makes us see life differently. o. . . what we learn

from Kafka or Huxley is not that the real world

is like the world they create; rather, having trav-

elled in imagination to a very different world,

when we come back to the real world we see it a

little differently and the difference seems to be

gain. The unlifelike element in the fictional world

is a device which makes us see things which are

present but overlooked, in ordinary experience.�

THE REBEL

ee " oe

Religious language gives a person ocategories�

or a ostance� or oposture� from which to live his

life. Frederick Ferre, speaking of the great reli-

gious symbols, says: ~They reflect a pattern or

organization of these depth experiences and if

responded to affirmatively can mould oneTs total

response to his world: implicitly embodying a

scale of values, an emphasis of outlook, a domi-

nance of drive which provides a distinctive

~stanceT or ~postureT toward the normal flow as

well as the great crises of life. Such great symbols

may be called ~organising images.T �

This is the side of religious language which one

can interpret literally. That is, a person may use

religious language in this way and actually show

to another the object of which he is speaking in

his existence. One will always want to add that

othis is not all I mean� but, within his existence

he can point to something actual, literal. Take the

statement oGod is holy,� for instance. First,

within one literal existence, what does he point to

with the term oG-o-dTT? God is, supposedly, that

which is always present, never changing, eternally

real, forever dependable. What is there within

oneTs existence which is this? Within some per-

sonTs existence everything which he touches is

transitory, passing on, changing. Whether it be

persons, things, societies, or what have you, they

are all changing and passing on. OneTs life itself

is passing away and he will someday die. Within

all this, what is there that is always present?

Nothing, except that everything is continually

passing on and is transitory. In other words,

oGod� is the linguistic symbol for the fact that

life is, more than anything else, in constant flux,

change, transitoriness, passing-away-ness. God

is this fact! What does one mean when he says

that God is holy? For something to be holy means

that one stands in awe and humbleness before it.

There is an element of fear that the full realiza-

tion that existence is completely transitory and in

no way stable creates within one a sense of awe,

fear and angst. One has the sense of being able

to cling to nothing whatever. The only thing he

has left to cling to is the fact that this is the way

things are. Thus, interpreted into his existence

literally, this is what the statement oGod is holy�

means. Some would want to say that the state-

ment means more, but the omore� can only be

shown, not said. :

Or take the statement oGod loves.� Interpreted

literally into existence one might say that when

faced with the deepest crises of life, when stand-

ing in what Karl Jaspers calls the oborder situa-

tions� of existence, when one has realized that

FALL, 1966

oGod� (as defined above) has utterly crushed him

and will always continue to do so (the Bible pro-

vides an excellent parable in the Book of Job),

when he sees that there is no hope left at all, the

Christian claims to have felt within his own being

a strange power which tells him that nevertheless

there is the possibility to live. To say that oGod

loves,� thus interpreted into existence, means that

when completely crushed by the force of existence,

one has yet found that there is the possibility for

him to live with gladness, with meaning, and with

hope. That is not all. Some mean more by the

statement ~God loves� but what that ~~moreTT is

cannot be said, only shown. The New Testament

states this mythologically by saying that Jesus,

when crushed by the Force of his Existence in

terms of a horrifying crucifixion, still found that,

even though crucifixion was the most real thing in

his existence, there was still the resurrection

through faith in God. In fact, Jesus called this

God oFather.� However, in so doing, Jesus was

not saying anything at all. He was conveying no

information. He was attempting to show some-

thing, namely a particular way in which one might

approach his existence"i.e., with the stance that

the crushing force of oneTs existence is actually

analogous to oneTs loving father. But to realize

the full impact of this, one must know the meaning

of an oinsight.� This oinsight� can only be shown,

not said.

These religious statements can become trans-

lated not only into a way in which to view oneTs

existence but also into a way of action. How

should one act toward his neighbor ?"God is love.

What shall one do with his enemy ?"~o~God was in

Christ reconciling the world... .TT As Ferre says:

oHere is meaning, volumes of the deepest mean-

ing, waiting to be translated into the fabric of

specific act and concrete life-pattern. It is because

we are here dealing with the most important sort

of meaning which any language can carry that

talk about God is incomparably vital, despite its

non-literal significance.�

Thus, one has seen the two uses of religious

language which this paper proposes. The first one

is to oshow� one something, to point him toward

the omystical,� call him to an oinsight.� The sec-

ond function, which is only really meaningful

after one has been part of the full meaning of the

first function, is to interpret the everyday goings-

on of his life. One uses his myths about miracu-

lous births, resurrections, creations, and so on, in

order to bring about an oinsight.� Then one

interprets these myths into concrete realities

which confront him in his actual existence.

25

POET'S

CORNER

Asha Yeats

I can remember that girl.

I can remember the day she died:

A long hot day in the Georgian summer,

And one that few people noticed

Save those of us who knew its significance.

A grave day, with petulant clouds suspended

In a low-slung, dusty-looking sky,

Green-hued in the west, and softly glowing

As before a storm. And there was a storm,

But not one that most of the people knew about.

I know about it, but I was closer to Asha Yeats

Than most people.

She was my mother.

She had a slack long body with thin strong arms

That could sweep you from the ground into the air

And whirl you around until you laughed and

laughed.

We had fun together, Asha and I.

She was young and vibrant and bold

(I myself was nine years old)

With thin-boned hands, and graceful and fine

The year I was nine.

And a wide mouth that laughed often.

The girl with the yearbook smile, Asha Yeats.

My mother.

We did the housework together, Asha and I,

Whistling and winking like sooty-faced chars.

But I remember the day she put down her dustcloth

And untied her tired hair

To help a little colored girl who lay

With her feet in the gutter,

Bitten by a mad dog.

Asha Yeats on her knees in the gutter

(While the neighbors watched from their win-

dows)

26

Picked up the little nigger child and

Took her to the county hospital.

ThatTs not done, said the neighbors.

In the deep South, thatTs not done.

And then things happened to us.

Dead things appeared in the front yard:

Mice, birds with torn wings, a rabid kitten,

And then one morning, a little curly-haired dog

With a torn throat.

Asha Yeats covered my eyes with her firm hands

And closed the blinds.

And we never told.

There were bad smells and a broken window,

And we never told. And a fire in the toolshed

That Asha put out with a blanket

Because the hose was missing and the spigot clog-

ged.

But we never told.

And Asha Yeats grew lonely and old.

Her pale eyes deeply set in her quaint head

Blinked in open defiance like a sullen-faced char

Until blinking was a drudge and breathing a chore

And she took sick and didnTt work anymore.

She dragged herself to my bedroom

And there she died, her weak cries

Splintering my brain and staying there,

Crumpled grotesquely on the white sheet,

My hands on her eyes,

My handkerchief over her mouth.

I was there, but she died alone,

As she did everything.

And here is where she lies, alone

Nestled in the roots of a pine tree

With so much to be proud of.

Pam Honaker

THE REBEL

J Became a Leaf

I became a leaf.

I sprang from the fingertip of a tree.

I greened and grew.

I covered a bird, nourished an insect.

I dripped of rain.

I slept on the wind.

I became vibrant with red, warm with golden.

I became tired.

I aged brown, grew weak, let go.

I dripped down and laid beside a moss, beneath a

rabbit.

I became moist and fed the earth.

Ceod

I see and feel the warmth and touch

Of eyes that pierce my depth until

I can no longer face the source

Of their disquieting power.

My mind rebels against the thought

Of alien control and though

Such alien control is all

Too inevitable, I must

Remember that obedience,

When blind, only leads me

Down to insensibility.

Were I to pause, however, and

Relax in the absorbing gaze

Of those circles of deep power,

Realizing that they seek not

Control, I would see their beauty.

GUY LE MARE

FALL, 1966

CMF Because

Two fingers following the curve of the chair-arm

Were her only proof that he was there

As the walls of the room surrounding them

Came and went with the shades of twilight.

The words were right for some purpose,

But not theirs, falling as they did on distracted

ears

Like a dream neither could remember,

Until he became more cross with himself than her

And tenderly took leave.

From the window she watched him

Cross the street, unwilling to grope for words

Worthy of being called across the distance"

This before she saw the coat, folded sleeves to-

gether

On the winey new-covered chair.

oYour coat is still here!�

She cried, her outsretched hand expressing all

That she could not, she

The no longer cherished.

PAM HONAKER

27

Second Place Fiction

Wintertime

And Not One Posy

by

Worth Kitson

It wasnTt fair to be so cold and still not snowing.

If itTs going to just be cold, well okay ... but

when itTs that cold, and it looks like itTs going to

snow, and the weatherman and your father and

even the old janitor at school all say it will, and

then it doesnTt"thatTs a pretty sneaky trick for

the sky to pull.

Miriam hated"really hated"her black wool

skirt. That skirt, with its knife-edged pleats