[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Student's Supply Stores

oGinst Inu Service?

On the Campus

YOUR CENTER FOR:

GREETING CARDS

COLLEGE SUPPLIES

COLLEGE BLAZERS

SOFT GOODS

PAPERBACKS

STATIONERY

Wright Building and South Dining Hall Ground Floor

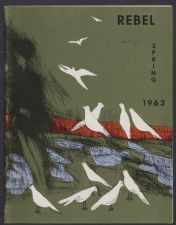

VOLUME VI SPRING, 1963 NUMBER 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RISIPORIAD © 5 2 oe ee ee 3

CONTRIBUTORS and EDITORTS NOTHS225625 2 40

FEATURE

Interview with Ralph McGill..33..34 0) ee 4

FICTION

The New River by B. Tolson. Waite: 3.5 = ee 12

James Davis and Kattie by Millard Maloney...»

HouseTof'Cards by Larry Biivatdss 3 6 ee a 24

Wisteria:by Sue-Ellen Brid@era. 2 8 Eee SS 28

Carnation for Summer by Pat: 5. Wie 82

ESSAYS

William Faulkner"His Descriptions of Nature by

Mary E. Poindextertc 20

Only the Image Reappears by Sanford Peele__...-_-_____________ 26

POETRY

Cat, by Helen Jenning#ij6> 7 3 ee 19

Into:a Pruned ParkTby:.B. Poon: Wii eas 26

En'~Marienbad by Sanford -peeie 2s se 31

REBEL REVIEWS

Reviews by Ben Bridgers, Gene Hugulet, Jim Forsyth, and Brenda

Canine a eS ea 36

COVER by Larry Blizard

PHOTOGRAPHY by Junius D. Grimes III

THE REBEL is published by the Student Government Association of East

Carolina College. It was created by the Publications Board of East Carolina

College as a literary magazine to be edited by students and designed for

the publication of student material.

NOTICE"Contributions to THE REBEL should be directed to P. O. Box

1420, E.C.C., Greenville, North Carolina. Editorial and business offices

are located at 30614 Austin Building. Manuscripts and art work submitted

by mail should be accompanied by a self-addressed envelope and return

postage. The publishers assume no responsibility for the return of manu-

scripts or art work.

STAFF

Editor

Juntus DANIEL Grimes III

Associate Editor

J. ALFRED WILLIS

Assistant to Editor

Friepa R. WHITE

Book Review Editor

Sue ELLen BRIDGERS

Business Manager

Tony BowEN

Advertising Manager

FAYE NELSON

Art Staff

LARRY BLIZARD

Durry TOLER

Louis JONES

Typists and Proofreaders

MARKY JONES

Ray RAYBOURN

WANDA DUNCAN

MILTON G. CROCKER

BRENDA CANIPE

JOYCE CROCKER

Faculty Advisor

Ovip WILLIAMS PIERCE

Circulation

Alpha Phi Omega Fraternity

National Advertising

Representatives

College Magazines, Inc.

11 West 42nd Street

New York 36, New York

Member Associated

Collegiate Press

EDITORIAL

In the interview with Ralph McGill in this issue

of the REBEL, he gives an interesting answer to

a question concerning the morals of American

youth. The question was, oDo you think that

the morals of American youth are undergoing a

transition today?? The basis for this question

was an article by Fred and Mary Heschinger in

a recent Sunday New York Times Magazine.

Their feeling was that our morals are undergoing

a definite liberalization, if indeed, they are not

becoming libertine. Their chief basis for this

is the open and frank discussion of sexual and

moral problems which they say prevails on to-

dayTs college campuses. They apparently disap-

prove, and feel that it is the responsibility of

colleges and universities to exercise in loco pa-

rentis to force adherence to traditional moral

standards where it appears that the students

themselves have not been so reared prior to col-

lege as to make such measures unnecessary.

Mr. McGillTs answer to the question was that

he believes it is not that our morals are under-

going any tremendous transformation, but rather

that the American youth of today are simply more

honest than they were in the Victorian era or

the era of the twenties. The Victorians were

hypocrites, and the twenties he calls the days of

the silver flask and bath-tub gin and the flapper,

of free-love and necking, of Greenwich Village

and ~the revolt in literature. Today, he continues,

seems comparatively mild.

We are not wholly in accord with Mr. McGill.

Bath-tub gin has simply been replaced by tax-paid

whiskey; the flapper has been replaced by great

groups gyrating some new craze called the thun-

derbird; Greenwich Village is still around and

the revolt in literature has more or less quieted

into commonplace acceptance. But the fact that

these things are more above board does not make

them necessarily quieter. It may make them

noisier.

But we do agree with Mr. McGill on one point

and disagree with the Heschingers. The open dis-

cussion and acceptance of the existence of prob-

lems of sex and morals is advantageous and should

not be perverted or controlled extensively by any-

one. If traditional moral standards are disap-

pearing, then it is not the responsibility of indi-

viduals who still wish to adhere to them to enforce

that adherence on others who do not. In fact, it

seems natural enough that with the disappearance

of the shibboleths and fears that sustained certain

moral attitudes and practices long after their

practical value had ceased to exist, the moral

values themselves should change or at least become

more honest.

As evidence of the benefits to be reaped from

wider and more open acceptance and discussion

of attitudes and practices that have existed all

along, we would point out the number of books

and movies that are accepted today that would

never have passed a board of censors ten years

ago. And these books and films are not trashy

Fabian types, but make a real contribution to con-

temporary American art. Books like MillerTs

Tropics have only in the last five years been

printed openly in the United States. Catch 22,

by Joseph Heller, which may well be regarded

as one of the great war novels of America, would

not have had a chance for open publication had

it been written ten years earlier. Certainly, it

would have had nothing like the wide public dis-

cussion it is currently receiving.

A recent movie, Hud, according to the majority

of the critics is an open and honest presentatior.

of an S.0.B. (Something they seem to think is

typical of contemporary society). It would not

have been produced five years ago. And the fail-

ure to produce such a movie, or to publish such

books would have been a failure to give to the

American public the honesty and integrity they

deserve from art. Consequently, if openness and

honesty are to be viewed by the Heschingers,

et al as indices of moral transition and decline,

we are heartily in favor of it, tradition notwith-

standing.

4

i

i

Ralph McGill was born in Tennessee and edu-

cated in the public schools of that state and at

Vanderbilt University. He came of age at a time

when the South was being changed and shaken

and as editor of the Atlanta Constitution has

championed the rights of freedom for a new and

better South. His recent book, The South and

the Southerner was winner of the Atlantic non-

fiction award.

Juterview with

RALPH McGILL

Interviewer: Has there been a failure in lead-

ership in the deep South?

Mr. McGill: Yes. I donTt think thereTs any

question but what there has been a failure of

leadership in the deep South. I donTt know that

this was a conscious failure. I believe that in re-

trospect we ought to be ashamed of this failure,

and probably are ashamed of it, because we should

have known that change was coming; and we

should have made some move to take care of it.

This we did not do. Here in Atlanta, for example,

I remember writing some months or weeks, at

least, before the nineteen fifty-four school season

that the decision was certainly coming, that it

could not be anything except what it was"a de-

segration decision, and that no one was doing any-

thing about it. The school board was not, the city

government was not, the newspapers were not, and

none of the P.T.A.Ts were discussing it. There

4

was a great silence, and yet everyone must have

known this was coming.

Now this was true all over the South. Here was

the great decision that broke the log jam. It had

been in the works a long time. Some people acted

surprised when it came, but it was not really a

surprise. We had had the previous decisions in

some years before. In fact we had already had

Negroes in Southern universities before the nine-

teen fifty-four school decision. L.S.U. had given

graduate degrees to two Negroes in nineteen

fifty-two or three. At the University of Arkansas,

there had been over a hundred graduate degrees

given to Negroes before the T54 decision. Texas

and Oklahoma had also admitted Negroes to grad-

uate schools. And yet we all sat back and waited

and waited, and did nothing . . . and acted, when

the decision came in May, T54, as if this were a

great unpleasant surprise. So there was failure,

and there has been failure since.

THE REBEL

~~

Interviewer: To what extent do you think that

this failure in the leadership has been responsible

for the problems in the South?

Mr. McGill: I think largely responsible. Not

wholly, perhaps, because I would be the last to

ignore the facts of tradition and the facts of cus-

tom, cemented by years of observance. But none

the less, I think I would have to say that failure

of this leadership to act responsibly is in the

main the reason for our troubles.

I donTt know if you remember how it was after

this decision. There was a period there of some

weeks, really about a couple of months, in which

there was a sort of silence. People said, oI donTt

like this school decision, but I guess I knew it

was coming;? or oI wish it hadnTt come; I hate

it; I donTt like the idea of my children going to

school with Negroes, but the Supreme Court has

ruled, and I guess weTll have to observe it.?T This

was pretty general. In my analysis of it, I rather

think that the fault lies chiefly in Virginia. Vir-

ginia is one of our most respected states, or was.

Virginia has a great tradition of civil rights,

human rights, the great tradition of Jefferson, and

all the other Virginians who contributed so much

to our history. At the time of this decision the

demagogues, such as our Marvin Griffin, then gov-

ernor of Georgia, and others over the South were

not being listened to very much, because they

werenTt too respected, and people would choose the

Supreme Court over them. But all the sudden,

here came Virginia, led by Senator Byrd, a re-

spected figure of conservatism, and Virginia began

talking about interposition. We may laugh about

this now, but for a time Virginia in effect threw

the cloak of her great respectability and tradition

about the backs of rascals and prejudiced de-

magogues, and all of the worst elements in the

South suddenly found that they had a respectable

leader, Virginia.

Then really the dam broke. All these people

came screaming out; the legislatures met; they

began to pass all sorts of foolish restrictive legis-

lation; and the air was filled with defiance. But

I think without any doubt, had the real business

leaders and the decent political leadership and the

clergy stepped forward, in that lull that followed

the decision, there would not have been the trav-

ail we now have.

Interviewer: Do you think that the church,

both black and white, has failed the South in the

integration crises or in the time leading up to

these crises?

Mr. McGill: Well, with certain notable excep-

SPRING, 1963

SSS

tions, I donTt think thereTs any doubt but that the

church in general has failed. I know that this is

probably the cause of more private agony on the

part of Southern ministers than any other thing

that has happened in their life time. ITve talked

to a great many. I have on my desk as we talk now

letters that have come in just in the last few days.

I have letters from ministers in Birmingham, and

these are really pathetic letters. ITve letters from

others who just sort of pour out their agony. What

can they do, they ask. The power structure of

their churches, the big givers, the men who are

the deacons, the elders, the vestry"they all along

have been on the side of the status quo. They have

joined in and supported the Bull Connors, the

Ross Barnetts, and the George Wallaces. And

the minister either makes a decision to resign or

to speak out and be fired. Over a hundred South-

ern ministers have been booted out of their

churches. Or shall they say, oWell, I will try to

stay here and hold this together, and slowly work

it out, if I can.? And I donTt criticize these men.

I criticize some of these who have gone with the

mob, and some of them have gone with the mob.

In Mississippi, some very fine young Methodist

ministers have been kicked out of their churches.

And there have been some loud voices of other

churches down there going with the mob. And ITm

an Episcopalian. WeTve had our own shameful

ministers in some of the Southern states who have

gone with the mob. The Baptists, Presbyterians,

even some of the Roman Catholics have had trou-

ble. But I think that thereTs a change, now. The

Roman Catholic church has moved strongly, the

Presbyterians recently have taken action, the

Episcopal church, Methodist, others .. . So I think

thereTs a change. But I donTt think even the

church itself would deny that it has been a failure

in these early years of this great problem.

Interviewer: Do you feel, as Tom Pettigrew of

Harvard, that integration is a function of urbani-

zation, that it will come first in the large cities and

then filter down to the rural areas?

Mr. McGill: Oh, I think this unquestionably,

and I think this would be a wise plan and policy.

I have editorially urged this from the beginning.

Rural population is declining everywhere. ItTs

moving to the cities and to the suburbs. This is

where the people are, and I think this is where the

energy and the money for legal cost should be

spent, in the cities; and then, once this is won, the

rural areas will have to fall into line. But I think

it is folly to spend a lot of time and energy in the

small town.

Interviewer: What do you feel is the real basis

for segregation? Why do you think so many

Southerners unreasoningly hate the Negroes?

Mr. McGill: Well, ITve thought about this a lot,

as obviously you and your associates have. And

it might be a good time for me to congratulate

you on this magazine you get out up there. ITve

had the pleasure of reading the copies youTve sent

me before your coming. TheyTre really tremend-

ous. I havenTt seen anything anywhere in the

university life of America thatTs better than this.

Well, I think a lot of it is fear"economic fear.

You take the poor white, and you know this prob-

lem of poverty and discrimination is not just the

Negroes. This is where we make a great mistake

in our thinking. Do you know that if you go up

in Chicago, in Pittsburg, and Philadelphia, and

New York, in all of these places, as well as in De-

troit and Seattle, and other areas, there are some

of the most pathetic people youTve ever seen. They

are referred to in these cities as ~Southern hillbil-

lies.? Now these are the poor whites who are not

skilled, who are not educated, who in the heyday of

the industrial revolution had jobs in the tire

factories and in the big automobile assembly

plants. They donTt have them now. TheyTre most-

ly all on relief. Most of them live in little en-

claves in Negro sections of these industrial cities.

They are looked down on by everybody. And what

we have got now in the great industrial cities all

over this country is what I think might be classi-

fied sociologically as a new minority"a new min-

ority of our time. This is the poor uneducated,

unskilled, white man who is on relief just as badly

as the uneducated, unskilled, unemployed Negro;

and these people make up a class which is just

about unemployable. I donTt know that theyTll

ever really be able to hold well-paying jobs in this

industrial society of ours ever again.

Now there are several million of these, and they

are pretty well distributed all over this country.

This is a phenomenon that we have not quite

6

caught on to, come aware of, rather. Now these

people"you take a fellow whose world is pretty

well crumbled around him, he isnTt getting along,

heTs unemployed, and heTs always believed that

his white skin entitled him to something better in

life, and he isnTt getting it. You get out of this

some real hatreds. You go down in the rural

areas where farm life is pinching and where

population is leaving and poverty and the great

corrosive difficulties of trying to live on a small

piece of land, stare them in the face daily and

when they see the educated Negro, and they read

about the rise of the African nations and they see

on television the French-speaking or Oxford-

English voices of Negroes from Africa, this

doesnTt set well.

I sometimes think that weTre getting some bad

reporting out of this violences of Birmingham or

Little Rock or Oxford. After all, I think you

and I"all Southerners"want to keep in mind

that historically the Southern Negro has been and

is a pretty fine, decent, amiable, kind, person. This

is historically true. And if we allow this big

picture of the American Negro, who is trying

just to be American and who wants to share in

the American promise"if we allow this big pic-

ture of a fine, decent person to be obscured by the

little picture"letTs say the photographs out of

Birmingham, showing the dogs and police club-

bing Negroes and knocking women down and

carrying them and throwing them in wagons,

their patrol wagons, or buses"in these small pic-

tures you might have had say, twenty, thirty, may-

be fifty persons. This is a very powerful picture,

but this is a little picture. There are several mil-

lions of Southern Negroes, and if we look at our

history theyTve made a remarkable contribution;

and if we lose sight of the fact that they are try-

ing just to share in this American promise. .

WhatTs wrong with the Negro, if heTs qualified,

voting? WhatTs wrong with him, if heTs skilled,

holding a job? WhatTs wrong with him, if he can

pay for it, and heTs clothed and orderly, being able

to eat in a restaurant? You donTt have to sit at

the table with him if you donTt want to. WhatTs

wrong with him going to a movie in the front door,

rather than having to go to the alley and climb

up into a balcony?

I think we in the South have got to face these

things and get the thing into perspective. After

all the skyTs not going to fall if the Negro has a

lunch and he can pay for it. He isnTt going to

come over and sit with you unless you invite him.

You donTt have to sit with him unless he invites

you and you wish to accept. We greet these great

THE REBEL

fears which are based on nothing. You get people

who actually say, oWell, the next thing, the gov-

ernmentTll be saying youTve got to invite them to

your house.? Well, this is bunk"you know that.

And they say, oWell, you going to have to marry

the Negro?? Well, I think the ordinary marriage

is tough enough; and certainly the person con-

templating any sort of omixed? marriage with a

person speaking a different language or a differ-

ent color would certainly be wise to give great

thought to it. But this is certainly a personal

thing, and not a matter of law or social obligation

or anything. We have allowed, I think, the makers

of myths and the shouters of lies to take up too

much of our time.

Interviewer: In the NegroTs wish for integra-

tion, what value do you think rioting as in Bir-

mingham has had?

Mr. McGill: Well, I think the Alabama thing

has had, and is having, a therapeutic value, just

as, I think, Little Rock did, and Oxford, and other

lesser riots; but especially these big ones, es-

pecially Birmingham, which had a longer period

of time, and which as we talk is still a hot spot.

There comes a time in a manTs thinking when heTs

got to make up his mind. Something like Birming-

ham happens, and he must at one time or another

say to himself, oIs this what I really believe? Do

Bull Connor and Governor Wallace"do they re-

present my thinking? Is this the sort of America

I want? Is this the sort of South I want? Is this

the real Southerner in action in Birmingham? Do

I want to join him?T I think he must go through

some kind of reasoning like this. Now, obviously

there are some in this thing who say, oYes, Bull

Connor is my idea of a Southerner. Governor

Wallace or Ross Barnett"theyTre my bold idea

of a Southerner.? But I think most Southerners

are not thinking that. So I think these things have

a therapeutic value. I know there must be a lot

of cities saying, oI pray to God we never have

a Birmingham here.?

Je 4) Se EF : \

Fa?

SPRING, 1963

Interviewer: Perhaps weTve just been lucky up

until recently, but why do you think North Caro-

lina has been able to handle the integration prob-

lem reasonably successfully, while some of the

other Southern states have not?

Mr. McGill: Well, I think that youTve had there

some public leaders, and you have had some news-

papers which have permitted, or rather, have in-

sisted on a discussion of this. The people in North

Carolina by and large have been made aware for

a long period of time that this issue existed, and

that some decisions had to be made. I think this is

why we were able to do pretty well in Atlanta.

This is why Nashville, Tennessee and other South-

ern cities that I could name and those in North

Carolina have been able to do better than the deep

South. LetTs turn over to Mississippi and Ala-

bama. With the exception of Hodding CarterTs pa-

per, and two weekly papers in Mississippi, the

whole press was on the side of violence and of, well

not violence; they were on the side of the extrem-

ists. This was true in the city of Jackson, Missis-

sippi, the capital of the State, and Natchez, and in

Vicksburg, and in all of the major cities of the

state. There was no other coice; there was never a

debate or, to use the new fangled word, dialogue.

There was never a dialogue. The same is true in

Alabama. It was just about four or five months

ago that the papers in Birmingham began to turn

against Bull ConnorTs ideas and methods. Just a

few months ago they were saying what a great

fellow Bull Connor was, and he was the sort of

leader they wanted as Commissioner of Police. So

the newspapers in Montgomery and Birmingham,

the two major cities, have been very critical of the

Supreme Court, of all of the decisions and talked

a lot of nonsense about federal imposition of pow-

er and all this. The people of Mississippi and

Birmingham never got an opportunity to be heard.

There are many decent people down there... in

both of these states, who donTt think this way.

But I think that in North Carolina you were

lucky in having some newspapers that spoke out,

some clergymen, some business people, some edu-

cational leaders who were willing to take a stand.

This means a great deal. This is the difference.

Some of your students also took stands.

Interviewer: How has the distribution of the

Negro and the Negro problem throughout the rest

of the country affected the viewpoint of other

areas toward the South?

Mr. McGill: I mentioned earlier this phenomen-

on, and a disturbing one of the national distribu-

tion of the product of several generations of seg-

|

regation. HereTs a region which had, like all agri-

cultural regions all over the world, a lower income

than the rest of the nation. To this day the per

capita income of the South is lower than the rest

of the industrial states. We didnTt have enough

money for one good school system"we tried to

maintain two. Until a year or two ago, there were

many rural regions, areas in the South that had no

Negro high schools whatever, and very poor white

high schools. There are still high schools in the

Southern states that do not teach any advanced

mathematics. Georgia Tech has to flunk out about

40 percent of its freshman class, coming from the

high schools largely of Georgia, because they are

not prepared to stay at Georgia Tech. I donTt know

about the University of North Carolina, or your

own college, but I would imagine you would find

some very dismaying statistics of fine young men

and women who have come from high schools

which have simply not prepared them to stay. Now

here in the South, we have grievously discrimi-

nated against generations of white and Negro

children; and now they are in Washington, D. C.

This is a dangerous situation. They, white and

colored, are in all the great industrial cities, and

they are not educated or skilled enough to hold

jobs. This is a national fact which is beginning

to, in some areas, cause people to think; in some

areas itTs causing animosity toward the South for

sending up all these illiterate, uneducated people

who drift off into crime. I think we ought to

wake up to the fact and the meaning of two statis-

tics: one is that for the first time in the history of

the United States, for the very first time in the

history of this great country of ours, the highest

percentage age-group unemployment is in the

youngest age-group, eighteen to twenty-six. For

the first time the young people coming into the

work force are increasingly unable to get jobs.

Why? Too many of them are unable to fill jobs.

Too many of them are the drop-outs, or poorly

prepared, or the failures in high schools. This

is a fact.

WhatTs the other statistic? It is that the great-

est increase in crime is in the same age group.

LetTs put two and two together. A great many

of these youngsters get married. They canTt get

work, married or unmarried. So they turn to

stealing, or to hold-ups, all forms of delinquency.

And this is two and two, makes four. We neednTt

kid ourselves. WeTve got a very bad situation

among a certain percentage of our young Ameri-

cans. And this is not good. This has never hap-

pened before. This is a development of the last

ten or fifteen years. ItTs just now beginning to

8

bear fruit, you might say; and a very ugly fruit it

is.

Interviewer: I was reading an article recently

in the New York Times Magazine on the change

in morals in American youth, discussing primarily

college students. Do you think that we are in a

transition period morally today?

Mr. McGill: Well, ITm not sure that I do think

so. Then we come back to what do we mean by

omorally ??

Interviewer: LetTs just say standard morals.

Mr. McGill: Standard morals. The Victorian

standard morals, or the twentieth century stand-

ard morals? Standard morals? Gee. ITm sixty-

five years old, just barely. I remember after the

first World War. That was when there came the

great revolt in America. And I would say that the

generation of the nineteen-sixties is fairly calm,

compared with the generation of the twenties.

These were the days of the silver flask, and the

bath tub gin, and the flapper, and of free love,

and necking, and Greenwich Village, and the re-

volt in literature. This was when Southern writ-

ers began to come along, and they were all writers

in rebellion. It was all literature of protest against

the status quo, against the old South, and against

the old Victorian confinements. These were the

days of the novelists that shocked America, and

so forth and so on.

I would say that the morals of American young

people today are more honest. I think they have

been getting more honest since the twenties than

they ever were before. I was asked out the other

night by some youngsters to go to a college dra-

matic group giving readings from John BrownTs

Body. And when it was over, they asked me to go

to one of the little sort of coffee house clubs, except

it was more beer than coffee. I was sitting around,

and they werenTt drinking any beer. They were

having coffee or soft drinks. But I looked around,

and most of them had beer at the tables, some

pitchers of beer or bottles. Some were having

coffee or soft drinks; and I thought to myself that

this was a more honest way of doing things than

in my generation in college; of course, my genera-

tion coincided with prohibition when everything

was furtive and secretive, and hidden and illegal;

I think this is better than our way. Now I donTt

know if this fits into morality. ITm not too disturb-

ed about the morals of young people today. I

think probably theyTre better than those of their

fathers.

THE REBEL

Interviewer: Do you think itTs possible to shock

America now?

Mr. McGill: Well, not in the sense, perhaps,

that they were shocked in the twenties. As I said,

or think I said, that this was a Victorian stand-

ard, against which the twenties were rebelling. So

that today youTve got a much more sophisticated

America, and youTve got a much more mature

America, I think. Certainly a younger maturity.

I can remember when I went to work on a news-

paper. We didnTt even use the word ocancer?

then. We certainly didnTt use the word osyphilis.?

We couldnTt discuss the problem of such a real

big thing then, in those days, venereal disease in a

city and how a great many innocent people were

infected with it, and so forth. We"great taboo in

those days"couldnTt use the word oleg,? couldnTt

speak of oleg.? It was just a lot of Victorian taboo,

some of it very foolish. Now today maybe we go

too far; maybe we're a little too free; but at least

it isnTt furtive, and it isnTt clandestine. It at least

has the virtue of being above board and honest,

honestly admitted, or honestly discussed. I think

you shock America today with some of the things

that come along. But I think itTs a more investi-

gative, more"America more willing to discuss

itself. This is one of the things the twenties did.

Gee, we began to look at each other.

Interviewer: Do you feel that federal pressure

behind integration will further minimize state

sovereignty?

Mr. McGill: Well, do you know, youTve just

asked a question which ITm sort of glad you asked.

Do you know there isnTt any such thing as state

sovereignty, and hasnTt been since seventeen

eighty-nine? We have all been listening to South-

ern politicians talk about the great sovereign state

of North Carolina or Georgia or Mississippi or

something. Now this is bunk. Have we got time

for me to read you something out of the Constitu-

tion? ITd like to get it out of a drawer here.

SPRING, 1963

What I have is a World Almanac with the

Constitution of the United States in it. And I

want to read something from Article Six of the

Constitution of the United States. This is not an

amendment. This has been in there from the be-

ginning, and says this under Section Two of Arti-

cle Six:

This Constitution, and the laws of the

United States which shall be made in

pursuance thereof, and all treaties made,

or which shall be made under the author-

ity of the United States, shall be the

supreme law of the land; and the judges

in every state shall be bound thereby,

anything in the Constitution or laws of

any state to the contrary, not withstand-

ing.

Then, Section Three:

The Senators and Representatives before

mentioned, and the members of the sev-

eral state legislatures and all executive

and judicial officers, both of the United

states and of the several states shall be

bound by oath or affirmation to support

the Constitution.

Now, how can you say that a state is sovereign if

it is bound by the Constitution and if it is bound

by the courts of the United States, and if the

state courts are bound by a decision of the federal

courts, and if the representatives and senators and

governors, and all executive and judicial officers

of the United States and of the several states are

bound by oath to support the Constitution"how

can you say there are sovereign states? This is

bunk.

We had a confederation, you know, after 1776;

and we had sovereign states in it, thirteen of

them, and they warred against each other. They

set up tariffs, and they worked themselves in to a

point where a couple of them were threatening

to go back to join England again as colonies. It

was a little Balkan set up, and it failed. So they

had to get busy and set up a central government,

and a constitution. And when that was adopted

in 1789, then the old sovereign state idea died.

Now the Confederate States recognized this when

they set up their constitution. They recognized

there was no sovereign state in the United States

Constitution"that they were quitting"because

they went to great pains to say that under their

constitution, that is the Confederate States, there

were sovereign states. Now if you will go to your

history teacher, American history teacher, or if

you will check any reputable historian he will tell

you that insistence on state sovereignty really

made it impossible for the Confederate States to

win the Civil War. The most grievous hurt they

had was the States Rights or State Sovereignty

complex. North Carolina was a great example of

this. Vance and all the others leading a great

-movement there were declared traitors by Jeffer-

son Davis and others and the same things hap-

pened in Georgia. Governor Brown. The States

RightTs theory of the Confederacy or the fact of it,

really made the Confederacy impotent. But there

is no such thing as a sovereign state in the United

States. This is just bunk. WeTve listened to too

many political speeches.

Interviewer: Would you say the potential con-

flict between the White and Black in part accounts

for the wealth of material that the Southern wri-

ers have had to deal with?

Mr. McGill: In part, but I donTt know that the

great flowing of Southern literature came out of a

conflict between the Negro and White. This is

something that has developed rather late and it

distresses me. I think the Southerner, the White

Southerner, knowing the real Southern Negro,

owes it to himself and his region not to let the

rascals and the violent people take over. I think

that the Southerner has developed the literature

he has because he has a great sense of history.

Probably because he had a sense of living in a

region that knew defeat, occupation by an army;

he grew up as youngsters of no other region did,

save some of those in New England, hearing his

grandfather talk about historical events. You

gentlemen missed it. But I as a youngster used to

know Civil War veterans. Both armies. I would

listen by the hour to their talk. My grandmother

talked about seeing the soldiers come. All this is a

part of the Southern heritage. Quite different be-

fore the Civil War. We had no literature before

the Civil War. We didnTt have much until really

about 1912-15 it began. We had none during the

Reconstruction period or after, but somehow it

began to come. I donTt know. We could have a

great debate on it, but I think itTs basically that

Southerners live closely with history and sociologi-

cal change, sociological pressures, such as no other

region has had.

Interviewer: What would you say is the best

contemporary fictional treatment of the South?

Mr. McGill: I donTt think you could say that

any of it could be taken as picturing the contem-

porary South because this would require great

generalities and there are many oSouths.? North

Carolina isnTt very much like Georgia. Your his-

toryTs different; your economy has been different;

your political history has been much more sound

and honorable than ours. You early went after

good roads and you early went after education,

way ahead of any other Southern state. Ken-

10

tuckyTs history is not like MississippiTs, or South

CarolinaTs is unlike Tennessee. I donTt think your

question will stand up because it implies that there

is a generality of Southern expression.

Faulkner, in my opinion our greatest, I suppose

this is an opinion pretty generally shared, reflected

a small region of Mississippi. Now many of his

characterizations had general application, but not

too much. He was writing about the area of Mis-

sissippi. Take Erskine Caldwell who, I think, in

one or two of his early books is really pretty good.

I think Tobacco Road is a good Wook. It was writ-

ten about real people. Erskine CaldwellTs father

was a Presbyterian minister, a very fine man who

devoted much of his life to the people of oTobacco

Road.? This was the real name of the region. Not

a region, an area. And Caldwell, this was his best

book, I think, because he lived it; he saw it with

his father ; he had a feeling for these people. These

were real people and he didnTt exaggerate them in

the book. But they were just a small back eddy of

people. You couldnTt apply Tobacco Road to all

of Georgia, although some people did. I donTt know

that your writers in North Carolina reflect the

whole South.

Interviewer: To what extent do you think the

image of the South in the eyes of the rest of the

country, has been created by the writings of Cald-

well, Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Flannery

OTConnor and these people?

Mr. McGill: Well, I suppose that they have, in

the minds of the average person created an image

of the South; but I donTt think, in the eyes of the

thoughtful person. No person, no thoughtful per-

son, could look at one of the tortured plays of

Tennessee Williams and really think this repre-

sented the South. His characters and their very

grievous psycho-analytical problems or natures

could be of any region. HeTs seen fit to place them

in the South, but I think Tennessee Williams re-

flects his own tortured childhood. His mother has

just written a book, or rather a book written by

THE REBEL

her has just been published. It pretty well ex-

plains Tennessee Williams, I think. Some people

are pretty well inclined to rubber stamp, to read

Faulkner and stamp the whole South by that or

Tennessee Williams. Just as some people look at

Bull Connor or Barnett and stamp the South with

Connor or Barnett or Orville Faubus in Little

Rock; but I donTt think that this is generally true.

Interviewer: Do you think that the bias of the

Negro writer has prevented him from a fair and

honest treatment of the problems between the two

races?

Mr. McGill: I think the bias of the Negro press

has certainly been harmful. I think this has been

irresponsible. Certainly some of the white press

has been equally irresponsible. But I think the

Negro press has been too much so, almost unani-

mously so. ITm talking about the newspapers, not

all of their magazines. There have been some

biased Negro writers, but I donTt think that this

is an indictment that could be drawn against them

generally.

Interviewer: Well, for example James Baldwin

or Ralph Ellison.

Mr. McGill: Well Baldwin, it might surprise

you to know is under severe criticism from a great

many Negro critics. They are saying that Bald-

win is writing too much out of his neuroses, out

of his own experiences, and he doesnTt really speak

for the Negro. I think Baldwin is a magnificent

writer. Some of his conclusions all of us in the

South would have to admit, or agree with, but

here again, I donTt know that you could say that he

is biased; or Ralph Ellison. TheyTre writing out

of a certain fury or inability any longer to accept

the fact of segregation and all that it has meant,

especially to the intellectual. Of course, the intel-

lectual tends to forget what it has meant also to

the average Negro. To the, what you might say,

the mass of Negroes most of whom have come

lately from plantations and farms into Southern

cities .. . but then thatTs too long story to get into.

Interviewer: Do you think the areas of intense

revolt, intense problematic rioting, again as in

Alabama, could have been anticipated; and if so,

could some strategy heve been conceived to avoid

mob rioting?

Mr. McGill: Well, I think so. Birmingham is a

unique sort of city; itTs not a Southern city, really,

as we think of Southern cities. This is a city thatTs

pretty new. It just got going a little ahead of the

turn of the century. It never knew anything of

magnolias or crinoline or quadrilles or lace and old

mansions or banjo and julep. It was strictly a

sweat, steel, slag, smoke town. They discovered

iron ore and coal, and limestone all together there.

This was to be the new South. Birmingham was

the new SouthTs town; it was going to be"was the

great industrial city. And itTs today the only

purely industrial city in the whole South. And it

attracted to it the people from the sharecropping

tenant farms, and it attracted the Negro, too, from

the same situation; they brought with them their

illiteracy and their fears, their economic insta-

bilities, insecurities, the prejudices. This has been

a town that has known violence a long time; dur-

ing the unionization of the miners, the steel work-

ers, there were many dynamite explosions, many.

And many people were killed ; and shootings. Well,

come on up to the present. Certainly, the people

of Birmingham knew this was coming. And up

Ttil about four or five months before it came they

were supporting the wrong people. They were

supporting the status quo, the Bull Connor atti-

tude of repression and fill up the jails. Now thatTs

no longer an answer. And, yes, I think had the

merchants who finally met, had they met a year

ago, had they asked for the support of the papers

and the clergy, had they started a program of

public education, I think they could have done

what theyTre now going to have to do"desegre-

gate some of their eating places, hire some Negroes

in their businesses; Yes, this could have been an-

ticipated.

SPRING, 1963

11

FIRST PRIZE

REBEL PROSE CONTEST

THE NEW RIVER

By

B. TOLSON WILLIS, Jr.

It had been raining every day for weeks until

the river swelled and writhed in its banks like a

full-bellied woman in labor. The soldiers on their

haunches sat close to their dome yurts, and the

steam from the rains rose from their bodies and

their black wool shelters so that a stench hung

heavy in the air. They would sit still or squat in

a circle around the fire but even then their dark

eyes rolled up toward the clouds looking for the

rain.

Yesterday, they had waited patiently, search-

ing the skies and leaving the circle only to herd

the horses back in close or to collect dung for the

night fire. But the rain never came and mum-

blings about a renewed attack on the walls hung

as heavily as the night fireTs smoke.

The dawn crept out of the gray mist and stretch-

ed its limbs, casting smeared prints on the solemn

walls of the city. The soldiers began to move about

in the heavy smoke of the morning fire. A man

hobbled out of the ring of smoke-clouded yurts,

moving slowly as if an infant on unruly legs.

Everything was beginning to move in the camp.

On a rise a little away from the yurts, a mounted

figure stood in statued form. The dew still clung

to his leather cap but had begun to trickle down

his overvest in the new heat. His shaggy steppe

pony stood stiff-legged with his head hung down,

asleep, and the manTs bowed legs clung to the

shaggy mountTs barrel on either side, his feet al-

most touching in the undergirth. His head hung

heavily on his short chest, but the eyes were sharp-

ly awake, studying the wall as though searching

for some sign of weakness. Perhaps there was a

12

crack. The wall stared back; the new sun burnish-

ed its high facings.

Among the men below there was a hoarse cry

and all eyes darted toward the north. The soldiers

grabbed their curved bows and shuffled toward

the closest of the herded ponies on the fringe of the

encampment. One rider galloped toward the rise

while the others mounted and rode toward a line

of ox-carts still toy-like in the distance. When the

rider reached the rise, he drew up beside his lead-

er. ~o~Mongi Khan, look to the north. The grain

carts are coming and the Persians come with

them.? The speakerTs yellow face was young and

smooth and as he spoke his dark eyes flashed un-

der the irregular bangs of black hair.

Mongi Khan raised his head slowly, still looking

at the wall. oIt is good that the grain comes,? he

said heavily. ~o~The menTs bellies have grown taut

as bow strings.?

The young manTs long lids knitted, then he spoke

again. oSurely our leader heard me say the Per-

sians come. Our armies rode to victory through

the armies of the North. Their heavy chariots

could not stop us, but here in the South the Chinese

hide behind their walls. The Persians bring their

wisdom to destroy the walls. Now we shall know

victory again.?

Mongi Khan spoke. ~You are young and the

dreams of victory are still sweet. I have been

fighting in this alien land for six years and it is

always the same. Only the wall is new. But you

are right. This is good news.

oBut my heart remains heavy to think that the

last message I received could not have been also

THE REBEL

good. The rain has been little where my brothers

roam the steppes and the eweTs udder has gone

dry. My son had no milk; now only his spirit

guards the herd and cries in the night. What re-

ward can another victory bring? The last brought

a return home and the birth of my son. My son is

dead now. Who is left to reap the glory of my

victory over the wall?? The two horsemen were

silent as they rode toward the yurts.

The day failed softly. A soldier hobbled out to

gather fresh dung for the cook fires. Around the

fire soldiers squatted and traded stories, their

faces flushed with thoughts of plunder. The arkhi

was passed many times around the circle until

the goatskin hung limp. Their glazed eyes glisten-

ed when they spoke of the council between their

leaders and the Persians.

In the tent the small fire cast wavering silhou-

ettes on the felt walls. The Persians sat on their

soft cushions with their plans rolled out in front

of them. The mongol khans squatted by the fire

waiting for them to begin.

oWe have surveyed the wall and found that

they are too thick for our rams and catapults. Be-

sides they are built in a series, possibly as many

as eight or ten in all.?

oHave you traveled so far from Persia to tell

us this?? The young khan exclaimed.

The Persian smiled. oThe young in conquest

must learn the patience of old rulers,? he said.

oThe walls are strong, but there is a flaw in the

cityTs defence. The ruins have worn themselves

out and soon the river will fall. This river flows

under the north wall and out under the south. We

will turn the river at the north wall. A new river

bed must be dug. When the river falls, the new

bed will be opened and the river will flow around

the walls. When the river no longer flows through

the city, the gates must be opened or they die of

thirst.?

Labor gangs were herded to build the new river

bed. The rains no longer came and the workers

fell on their hoes in the heavy heat. The stench

of the dead followed the broad trench as it snaked

around the west wall and slowly moved back to-

wards the south. New gangs were herded in by

the Mongol horsemen to replace the men that fell.

The Persians worked in shifts driving the diggers

day and night. After six months the new river

bed was completed. Only a small dike held the

river back on the northern end of the new bed.

Mongi Khan sat on the rise above the northern

wall and watched the workmen break the dikes.

The river swirled and writhed against the new

banks and then began to move toward the south

once more.

SPRING, 1963

The days grew more intense and the cooler

nights seemed to pass too quickly. The horsemen

discarded their leather over-jackets. They watch-

ed the walls day and night. Each night the defend-

ers crept to the new river and were killed.

Mongi Khan sat watching his horsemen strung

out along the new river. They suddenly moved to-

wards the wall. Mongi Khan saw scattered figures

running back toward the wall but still holding

water skins. Many fell in the first barrage of

arrows loosed by the Mongol horsemen.

Mongi Khan rode closer. Lying in the dust

were not fallen soldiers but old men and women,

their gnarled hands still clutching the punctured

skins of their water vessels. Mongi Khan reined

in beside the leader of the band. His eyes were

dark and narrow. oHai! Are you soldiers or

wolves that drag down only the old??

oIt is part of their plan to get water,? the leader

replied. oFirst they sent their soldiers and we de-

stroyed them. Then they sent their children and

we rode them into the dust. Now they send their

precious ancients. We must stop them all.?

oEnough! When the old ones come again, let

them drink. Take their water vessels but let them

drink.?

oThey will soak their clothes and try to take

water into the city in their mouths!?

oEnough!? Mongi Khan turned and rode away.

The young Khan rode towards the new river.

His eyes flashed and he screamed for the leader of

the river patrol. oOx! Stupid Ox! Why are these

allowed to drink??

oMongi Khan willed it so.?

oMongi Khan is no longer the leader. He has

swallowed dust and stones and lies dead in the

old river bed. I am the leader. Ride them down!

We must break their will before the rains come

again.?

Mongi KhanTs crooked legs lay sprawled out be-

hind him. His neck seemed broken and twisted

under his body. The hot wind swirled pools of fine

white silt around his crumpled form lying in the

old river bed.

The clouds moved slowly, piling up overhead

and the fine wisps of silt settled over Mongi Khan.

Then came the first drops, pelting the silt and

raising tiny puffs of white smoke. The puffs be-

came heavy clouds as the rain increased. Small

rivulets began to flow around the white form

lying in the river bed. They broadened and began

to rock the body, finally lifting it. Slowly the body

floated down toward the city. The new waters

flowed softly through the iron-grated opening in

the wall, leaving the body to gently bump against

the iron rods.

13

and

KATTIE

By

Millard D. Maloney

JAMES DAVIS

14 Ae THE REBEL

| had my jacket slung over my shoulder, and

I could feel the lining of it growing hot against

my back. I was kind of tired, and I reckoned that

the girl was too. WeTd walked over five miles.

When we got to a good sized tree I said, oLetTs

sit down.T?T We moved to the side of the road, and

I spread my jacket for her to sit on. She began

to cry. I eased her off my jacket a little bit so I

could get to my cigarettes in the pocket. When

I got to the pack I seen that there wasnTt but one

cigarette left. I lit it and handed it to her. She

took it, but didnTt take a good drag on it. She just

sat there, holding the cigarette with one hand and

wiping her eyés with the other. As I watched the

smoke float upwards I got to thinking about the

time we were in that nightclub in Raleigh"weTd

gone up there for the weekend to see the oMid-

nighters?"and she was holding a cigarette then,

just like she was now, in that loose way she has

so that it looks like sheTs about to drop it. That

was when it happened, I guess.

oMiz Turner said it wonTthurt much,? I said.

Even while I was saying. it I knew it wasnTt the

right thing to say; and long after ITd said it, even

after weTd gotten up and started walking again,

I could hear it: oMiz Turner said it wonTt hurt

much.? She didnTt say anything. I sat there envy-

ing her the cigarette"wishing sheTd take a drag

on it and hand it to me"and trying to think of

something pleasant to say. I carried on a conver-

sation with her in my mind: oYou know I love

you, donTt you, Kattie??

oUh-huh,? sheTd say, oI know it.?

oYou know if there was any way at all to get

out of this I wouldnTt let you go through with it,

donTt you??

oT know that, James,? sheTd say, oI know that.?

Instead I said, out loud, oWe ainTt got much fur-

ther to go.? She was still crying. I put my arm

around her and pulled her close to me. oHush,? I

said, and I kissed her on the temple. Her hair

was wet, and it smelled of tears and sweat. oHush

now,? I said. oAinTt no need of acting up like

that.? And I felt like I was her father right then.

All of a sudden, in that funny way women have

of changing their minds like their minds work on

strings, she stopped crying. oCome on James,?

she said. oWe gotta get going.? We got up, and

after I had dusted my jacket we started down the

road again. We were going to a place called

Granite Quarry. ItTs so small it ainTt even listed

on county maps, let alone North Carolina, or Unit-

ed States maps. The first thing you come to on the

road we took is a big magnolia tree. Right along

side of it is a white frame house with big columns,

SPRING, 1963

and a little way down, just after a store with a

neon Pepsi-Cola sign, is the colored section. When

we got to the magnolia tree I said, oYou want to

rest a while??

oWe almost there, ainTt we?? She asked.

oYeah? I said.

oThen come on.?

Katie wasnTt but nineteen, but I felt right then

like I was her son.

I kind of had a picture in my mind of what the

house would look like. It belongs to a woman

named Miz Thomas. Miz Turner had told us it was

the biggest house in town. I figured thereTd be a

big living room with lots of furniture, and bare

floors. And I figured thereTd be one of those signs

saying oGod Bless Our Home? or something, I

was right about everything exceptthe floors.

There was a big rug in the living room, and so

many small ones that I kept tripping on them.

There were lots of little doo-dads around too, on

the mantle piece and on the tables. On one table

there was one of those monkey things you see

everywhere: see nothing, hear nothing, say noth-

ing. \I never did like those things.

L.was wrong too about Miz Thomas. I'd always

imagined that women who did that kind of work

would be big and fat and evil-looking. But Miz

Thomas wasnTt big, she wasnTt fat, and she wasnTt

evil-looking. She was in her late thirties, ITd say,

kind of thin, with a pleasant face. In fact, she

looked just like the kind of person youTd expect

to see pushing somebodyTs baby down the street

on Sunday afternoon. When we told her that Miz

Turné? had sent us she acted like we was old

friends. After we had chit-chatted a while she

said, oWell I guess we had best get started.?

I stood up and paid her the amount that Miz

Turner had told me to, and after sheTd counted the

money she and Kattie got up.

oYou can stay out here if you want to,? she

said. oOr you can take a walk. Hither way is

okay.?

oThanks, I think ITll take a walk.?

oAlrighty, we'll see you in about half an hour.?

oA half-hour??

oMmmmm .. . better make it forty-five min-

utes.?

I left. I wanted to say something to Kattie, but

what could I say? Good Luck? The damned thing

about life is, it seemed to me then, that there ainTt

never nothing to say when life and death is in-

volved. So I just left.

I walked down the street, trying my best not

to think of anything. But it didnTt work. I found

myself picturing what was going on back there

15

at Miz ThomasTs. Then, walking by a bunch of

children playing, I seemed to hear the girl scream-

ing with pain, and Miz Thomas saying, oHush

now, it wonTt be long.?

I went into a store and bought me a bottle of

wine ... but I could still hear the sound of her

screaming and it was near Tbout driving me

crazy. I felt like snatching the top off the bottle

and drinking the wine down right there. I walked

out of the store and looked around for a shady

tree, and when I found one I sat down under it

and opened the bottle. The wine was sweet, and

the gurgling sound it made drowned out the

screaming some. I even thought of saying a pray-

er for the girl, but I figured it would be dis-

religious to pray while I was drinking, so I didnTt.

Then I got to wondering what the child might

have been, a boy or a girl, and who it would have

looked like most, the girl or me. And after

the third drink of wine I got to wondering if it

would have been a real child at all. oGod forgive

me,? I said, and I took a good long swig.

When I got up I was half-drunk, and real un-

happy. I went back to Miz ThomasTs house and

rang the doorbell. There was no answer. I rang

again. No answer. What a nice front porch I

thought, and I waited. A real nice house too. If it

wasnTt for them monkeys in there me and Kattie

could.live here real nice. It would have been a

girl Tll bet. Ugly and wrinkled at first, like most

babies are at first, then pretty once she came out

of the hospital. Still no answer. I rang the bell

again, loud and hard. Miz Thomas came to the

door. ~Hi,T she said smiling.

oHow is she?? I asked. She looked at me as if

ITd asked something outrageous.

oSheTs fine.?

oCan I see her??

oSure, come on in. SheTs in that room right

over there.?

When I got into the room the girl was lying on

the bed fully undressed. She looked tired and ex-

hausted, I thought. But if youTd seen her face

right then youTd have sworn sheTd just come from

a party. I didnTt feel happy or surprised or re-

lieved or nothing. I just stood there, leaning

against the door and looking at her. She never

looked prettier, I swear. Nice dark skin, and long

dark hair falling down around her shoulders. I

went over and kissed her, and I hated myself for

wanting her again.

oHowTd it go?? I asked. oDid it hurt much??

oTt wasnTt bad.?

oThatTs fine,? I said. ~oThatTs just fine.?

~o~WhereTd you go?? she asked.

oT took a walk.?

16

oTI know, but where??

oJust around. How do you feel, Kattie??

oT feel fine.?

oCan you walk??

oSure I can walk.?

oThen letTs get out of here.?

oT canTt go right now.?

oHow come you canTt go??

Miz Thomas said I got to lay down for a half-

hour.?

oThen will you be alright??

oT donTt know.?

oWhat do you mean you donTt know??

oTt ainTt over yet.?

oAinTt over yet??

oNo. It takes .. . donTt lets talk about it, James,?

she said. She pulled my head down and my face

was in the pillow beside her, and I could hear her

hair crackling like thunder in my ears. oTell me

everything, James.?

oT saw an old colored man,? I said, talking into

the pillow and not thinking of what I was saying,

just talking, ~~in a brown raincoat, it was kind of

strange because I never seen anybody wear a

raincoat in the summer before. I saw a bow-legged

boy rolling a hoop down the street with a stick,

and just before he got to me the hoop wavered

and fell just like a coin when it stops spinning.

I saw a cloud in the sky that looked just like a

horse, and then I saw roses and people and houses,

and when I looked at the cloud again it didnTt look

like a horse anymore, it looked like a woman with

wild hair. I sat down under a tree and there was

a huge heart carved on it with an arrow through

it and the initials MM and KN. Are you feeling

better, Kattie??

oTell me some more.?

oHow come it ainTt over yet, Kattie??

oTt takes twenty-four hours, tell me some more,

James.?

oTwenty-four hours!...

eg i

oJesus!? I said and I raised her up from the

pillow.

oYou ought not to say that,? she said. oYou

done told me plenty times not to say it.?

oHush,? I said.

oDonTt tell me to hush. You the deacon of the

church, ainTt you? You ought to...?

oHush!?

oYou ought to know better than that, and a

widowed man to boot. You really should know a

heap better, James Davis. You with a grown up

son almost my age. YouTre old enough to be my

daddy, James. Tell me, youTre supposed to know

everything ainTt you? Then why donTt you

?

THE REBEL

answer me? AinTt you got nothing to say? You

thatTs got the message of God and gives it to the

people every Sunday morning.? She grunted and

laughed. oYou gave me a message alright! Yes

sir, I got your message.?

I didnTt say anything. I was lying flat on my

back now, staring up at the ceiling with the girl

young and naked and beautiful lying beside me.

When she calmed down I said, oDo we have to stay

here all that time??

oNo. We can go in a little while. It happens

tomorrow.?

oMiz Thomas gonna be there??

oNo. She done all sheTs got to do.?

oYou sure??

oSure ITm sure. What time is it??

oFour-thirty.?

oT got to lay here about five more minutes.?

She crossed her legs and sighed. I hated myself

all over again for wanting her so much.

** * *

There was one bus from Granite Quarry to

where we lived that left at six thirty every even-

ing, so we took it. Nothing happened on the way.

We sat on the back seat and the girl slept with her

head on my shoulder most of the way. When we

got close to home I started thinking of people we

might meet, and what theyTd think and say. The

girl must have been thinking the same thing be-

cause she said, just before the bus stopped, oI

guess ITd better go on home alone.? I didnTt say

anything because I knew it wasnTt no time to

argue. When we got off the bus I took her by the

arm and started towards my place.

oJames, I reckon ITd better go on home.?

oTTm taking you over to my place.?

oYou know what folks will say James: ~His wife

ainTt been dead a month yet, and him runninT

around with that girl .. . and him a deacon of

the 4,420"

oHush,? I said. oEach one of us got his own life

to live. If you start worrying what people say and

think, youTll wind up sittinT in a corner some-

where. Come on.?

oJames, my daddyTll kill you if he ever finds

out.?

oT ainTt studying Tbout your daddy ... I ainTt

only older than him but ITm bigger too.?

When we got to my place I pulled the shades

and turned the lights on. The girl sat on the bed.

I took my jacket off and looked in the cabinet to

see how much liquor there was, because I figured

she might need it. There was almost a full bottle

of Little Brown Jug, and I was, happy about that.

I poured a drink in a small glass and handed it to

her. Then I poured myself one and said, oHereTs

SPRING, 1963

to it,?T but she had already drank hers.

oMiz Thomas said I was to walk around a lot.?

oWalk? How come??

oShe says that makes it easier.?

I thought for a while, and in spite of what I

had told her I really didnTt relish the idea of any-

body seeing us together. Then I said, ooHow about

dancing then??

oYeah,? she said.

We must have danced for over an hour, me

guiding and her following, close and warm, with

all the sins in the world spinning around in my

brain.

oWait a minute,? she said. And we stopped

dancing.

oWhatTs the matter??

oNothing. Just wait a minute.? She put her

hand to her forehead and sat on the bed. I sat

down beside her and moved her hand away and put

mine where hers had been. Her forehead was

warm, but I couldnTt tell whether she had a fever

or not. She put her hand to her stomach and made

a face. Not a painful face. The kind a woman

makes when she sees something she doesnTt like.

oT reckon ITd better call Dr. Branch.?

oDonTt be a fool, James.?

oDoes it hurt real bad??

oNuh-uh.?

oAfter youTve rested a little while I think we

ought to dance some more.?

oTI donTt feel like it, James.?

oTtTll make it easier for you. Miz Thomas knows

what sheTs talking about, so you ought to...?

oT done told you I donTt feel like it, James.

Please leave me alone.?

She lay down and turned over on her right side

facing me, with her hand resting on her stomach.

I got up and started looking around for a blanket

to throw over her, but I changed my mind. She

was sweating. I changed the radio station to some

fast music, and I turned it up loud.

oCome on,? I said. ~oLetTs dance some.? I took

her by the hand and began pulling her up from

the bed.

oDonTt, James.?

oCome on.?

oNo, donTt.?

oLetTs get with it honey. ThatTs little Benny

Harris on the sax. Little BennyTs your favorite,

ainTt he?? I snapped my fingers in time with the

music with one hand and pulled her up with the

other. She sort of half-laughed and half-cried and

got up. I held her close and we moved around in

a two-step off time.

oFeel better??

oUh-huh. A little.?

17

I kissed her cheek and held her closer. After a

while I could feel her fingernails biting into my

back, and just for a brief instant I could hear the

screaming again, like I did back in Granite

Quarry. I moved back a little.

When the song was over I turned the radio

down. Then I poured two drinks and handed her

the bigger one. She drank it down like it was

medicine and then she lay back on the bed. She

looked good lying there. Looking down at her I

thought, ~ooWhat the hell, that would be more fun

than walking or dancing.? Then I called myself

the dirtiest name I could think of. Out loud I

said, oItTs about time for you to get some sleep.?

It must have been five oTclock on the morning

when I woke up. The sun was just rising, and

through the shade, the soft light of morning made

the room look like rooms in dreams.

I raised myself on one elbow and looked at her.

I wanted to kiss her, but I was afraid it would

wake her. She woke up anyway, moaning. I

could see from the way the sheet fell over her that

she had her hand on her stomach again. Only

this time it was lower than it had been the night

before. She sighed. And she smelled like morn-

ing.

oHowTs it going, Kattie??

oNot so hot.?

oNot so hot??

oNot so hot.?

oCan I get you something??

~Nai?

oA glass of milk? An orange??

oNo, James. Nothing.?

oCan I do anything at all for you??

oYeah. You can do something for me, James.

Take me to Raleigh, right now. Chicago, New

York, any place. But right now.? She doubled up

right sudden like, with her knees up close to her

chest. She was crying. I wished right then that

I could go through what she was going through;

that I could do it for her, or either with her. But

I didnTt say it. A man canTt say a thing like that

to a woman and sound like anything but a damn

fool. So I just lay there with my arm around her,

staring up at the ceiling. ~Tell me something

funny,? she said.

oLike what??

oLike anything. Anything funny.?

oAlright. I'll tell you the story about Sam the

Man.? And I couldnTt remember the story word

for word, but I did my best.

When I had about half finished the story the

girl laughed and started beating on my chest.

Only she wasnTt laughing, I found out. She was

making the kind of sound a child makes some-

18

times, so that you have to wait a while before you

can tell whether itTs laughing or crying. So I

didnTt finish the story. I just lay there and looked

at her.

We laid there an hour or two, with her tossing

and turning and telling me it wasnTt any need to

get Dr. Branch because there was nothing he

could do noways. Then I got up and fixed break-

fast. I figured sheTd want to have hers in bed,

but she said no. She had gotten up and put some

clothes on and sat down at the table. She ate

hearty, and I was glad. She didnTt have her hand

on her stomach anymore. In fact, if you had seen

us right then you would have thought there was

nothing wrong at all.

After breakfast she took her clothes off and

got back into bed. I tried to get her to dance, or

even to walk around the room a little, but she

wouldnTt hear it. In a little while she fell asleep.

I started cleaning the place up, but I was afraid it

would wake her so I stopped. I sat in that wicker

back chair for a while. But I couldnTt stand do-

ing nothing so I got up and started cleaning again,

real soft like. When the place was clean I washed

the dishes and sat back down. The girl groaned

and I looked at her, but she was still asleep. I got

up and shined my shoes, then I put them back

under the bed and sat back down again. I went

over to the window and looked through the cur-

tains. There was nothing to see but the house

across the street, and ITd already seen it eight

million times. It needed painting; has needed it

for going on two years now. I felt like going out

there and painting it myself. ITd paint the front

porch first, just like the front part of your body is

the first part you wash, then ITd get the sides and

the back. ITd fix the back stairs where those steps

are loose, then ITd paint them too. Maybe ITd weed

out the garden and plant some collards and stuff.

I was thinking of that when the girl woke up.

oJames.?

oYes??

oT thought you was gone. What time is it??

oNear Tbout three oTclock. You want something

to eat??

oNo. I ainTt hungry.?

oHow do you feel??

oT donTt know. I donTt feel nothing at all. Noth-

ing.? She was quiet for a while and then she said,

oTI been having the craziest dream. Did you hear

me laughing??

*No,TT

oT dreamed I was in a boat with a man. A sail-

boat. But I couldnTt tell whether the man was you

or somebody else. Anyway, there we were, and

the man was rowing the boat and telling me a

THE REBEL

joke. I canTt remember what it was now, but it

was so funny that we both got to laughing and the

boat turned over and there we were in the water,

just laughing our fool heads off. You didnTt hear

me, James??

oNo, I didnTt Kattie.?

oThatTs when I woke up and felt for you and

you werenTt there. You ainTt going no place are

you James??

oT ainTt going no place, honey.?

oTf you do will you take me with you??

oSure I will, honey.?

oWhat time is it, James??

oA little after three.?

oI wish it was after three tomorrow, or next

week.?

oDo you want an orange??

oNo. You ainTt going to leave me are you,

James??

oYou know I wouldnTt do nothing like that.?

oThen what are you standing so far away from

me for??

I went over to the bed and sat down beside her.

Then I leaned over and took her in my arms.

oJames,? she said. oJames.TT She was crying, and

I could feel her fingernails biting into my back.

Around five oTclock I was sitting in the chair

reading the paper. The girl wasnTt crying or

groaning or anything, she wasnTt asleep either.

She got up real casual and went to the bathroom.

She was gone about twenty minutes I reckon be-

fore she came out, still undressed, and changed the

radio from the news to some music. Then she

started dancing by herself; not wild or anything,

just dancing. I thought that was a good thing be-

cause of what Miz Thomas had said, so I just sat

there and watched her moving her hips and snap-

ping her fingers and looking so good I could have

worshipped her.

oYou feel alright??

oSure I feel alright,? she said. ~I feel fine.?

oItTs about time.?

oYeah.?

oYou reckon Dr. Branch might...

?

oAinTt no need of no doctor. ItTs all over.?

MOVERT oe

= Gan

oDamn,? I said.

oDonTt say that,? she said and laughed. She

turned the radio up, still laughing, and she got to

dancing right wild like, kicking her legs up and

singing along with the music. When she got tired

she flopped on the bed and looked at me. She

smiled. I got up and turned the radio off and sat

down beside her. She was breathing fast.

oITm glad itTs over,? I said, and leaned over and

kissed her. I could see the tiny light reflections

dancing in her eyes. I kissed her again, soft.

oJames, James donTt. James, darling . . . please