[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

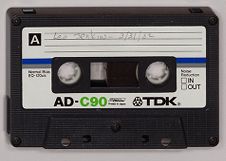

Dr. Leo Jenkins

Narrator

Dr. Mary Jo Bratton

Interviewer

March 31, 1982

Dr. Leo Jenkins home

Greenville, North Carolina

MB: This is an interview with Dr. Leo Jenkins at his home, March 31, 1982.

[interuption in interview deleted]

One of the things I wanted to ask you about, Dr. Jenkins, was some of your early background. I know you are from New Jersey, but I never heard very much about the young Leo Jenkins.

LJ: Oh well, there was nothing exciting. I went to Jefferson High School for Boys, which as a matter of fact I had very little experience with coeducation. When I went to grammar school in Elisabeth, New Jersey, the playgrounds were separated with a tall sixteen-foot fence, and if a boy got caught in a girl's playground, he was in real, real trouble. And we were just kept separated.

MB: So, you had that kind of segregation, between boys and the girls?

LJ: Oh yes. Then I went to Jefferson High School for Boys which was an unusual type of thing. For example, we had a dance, the girls high school which was about two miles away would send people over and our boys would go. But they weren't used to being with girls, so the boys would stand on one side of the gymnasium and the girls on the other. And two or three bold types would dance and we'd all watch them.

Then I went to Rutgers which was for men only when I went there. And the first time I really had a female in class to be a companion in class was at graduate school at Columbia. And it was a Catholic nun in class with me. So I don't know whether that conditioned my thinking or not, but it was a different type of education which I wouldn't want my children to have. But it did me no harm, but it was different, and I'd rather have . . .

MB: But I guess that was not all that unique for people growing up in your area, that was the standard.

LJ: Yes. Everybody who went to public schools in Elizabeth among the men went to Jefferson High School for Boys.

MB: And then they had the other for girls.

LJ: Batton High School for Girls.

MB: When did you graduate from Rutgers?

LJ: 1935. I went to Rutgers all during the Depression and it is very hard to explain the Depression for one who has not lived through it, because it is unique. I remember going to a theater, having three people in the audience and five acts of vaudeville, an orchestra, and the major picture; and there would be three people in the audience. You'd think they would cancel the show, but they had to keep it going.

Arthur Burns, the former head of Federal Reserve, was my teacher for two years at Rutgers in economics, in economic theory, business cycles, and statistics, and I remember yet, thinking back, he told us that he was a full professor and he was now makin $3000 a year. I said to myself, "If the Lord ever puts me in a position where I can make $3000 a year, I'll never ask for anything else. Never ask for anything else."

MB: It seemed so impressive!

LJ: Yes. I thought, "this is wonderful." The fellow comes here and talks to us for an hour or so and goes home and he gets $3000 for that.

My goodness, people, well, of course, the popular song was Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? and people were selling apples in New York. It's very difficult to understand how dreadful it was. Some very prominent families in our town lost everything because they bought a margin on the stock market. It wouldn't be unusual for a fellow to go to work in the morning and then come home and tell his wife everything was gone, the house, the car, everything, because he couldn't cover the margin.

Cord stock, Cord automobile was a new type of car that had a front-wheel drive, so that stock went sky-high up to four hundred and something plus, and it fell down to three or four dollars in one day. Well, men who bought a margin, they might have bought several thousand shares and maybe put a $1000 down and they owed the rest. Well, they had no money to pay the rest now. They were hoping to sell again real quick when it went up.

I remember men going by my house, WPA, they tried to create work for people. They gave them a shovel and told them to build a hill over there or over yonder. And these men would come by with dark glasses on and put their head real low because we recognized them as very prominent people, a former president of a bank, that type of prominent. Because the banks would fold and they would lose everything. They had to work to eat.

So under those conditions my college was not a Rah Rah experience. It was strictly business.

MB: Serious.

LJ: Because you say, "How lucky I am to be here." Most of my friends had to drop out or do something. Salaries were miserably low. Well, to illustrate, Prudential Insurance Company paid typists and stenographers and secretaries $12.50 a week, that was the salary. And my first teaching job, I had to pay ten percent to the agent that got it for me. I got it through a teachers' agency in Philadelphia. He got ten percent of the salary. I was paid in script, Atlantic County script, Atlantic City is there. Because they didn't have any money, so they gave you a promissory note that was negotiable in some stores, not in the chain stores, but you could go to the theater with it or you could go to a neighborhood store with it, but the chains didn't touch it. Most people would sell it to brokers.

My big salary was $1400 a year with ten percent off and then the salary, I would be lucky if I got eighty cents on the dollar. You see I had to sell my script.

MB: They discounted it?

LJ: Yeah, they discounted it. Well, men who owned property could pay their taxes at full credit with the script and such men often had children in school. So what the teachers would try to do, was try to ferret out some of the children who came from homes whose fathers needed this stuff and instead of getting eighty cents on the dollar, he might give you ninety cents or ninety-five, you see. So it was really a blackmail type of courting kids whose fathers could buy your salary.

Then in some months the rumor would start and the rumor would be true that they weren't going to pay at all this month, so you would get no pay this month or the next month. My wife, Lillian, my first wife, applied for a job and I think there were over a hundred or so candidates. And they all took a test of one type or another. She got a high score on her test and so she was one of four people out of hundreds, really, who applied and she got the glorious salary of $1000 a year. It was that type of situation.

It made me laugh when I came back to East Carolina and the GI Bill was coming along. We had, I had no spending money, once in awhile I'd pick up a half dollar or something from my folks or my sister or someone, but really you just lived without spending money. Your recreation was the library or that quarter movie I told you about, where you saw the vaudeville and everything. But it is something that is very hard to comprehend, but it did make me laugh when I came to East Carolina. Some boy came in enraged almost. He was having some trouble with his GI Bill. He said, "Do you know what it's like to go to college with only $100 a month spending money?" And I just laughed at the poor boy. He thought I was being a smart aleck and he said, "What are you laughing about?" So I sat him down and explained what the Depression was like. Why a millionaire, if you had a hundred dollars a month to spend when I was in college, they'd consider you a millionaire. The professors would be courting you.

LH: Then I graduated and I lucked up in a nationalized chemistry test. It was just one of those things. I'm not trying to be modest or anything. But it's one of those things, when one can luckily study the right thing. Sometimes there is a little footnote and you just happen to remember that and one of the questions will just happen to be that footnote. One of those things, just pure luck. I got a very high score. So my professor in chemistry at Jefferson [High School for Boys] insisted that I owed it to my society, I owed it to myself and my family and the school, to major in chemistry. So I went off to Rutgers University to major in chemistry.

It took me only about a semester to find out what a terrible mistake it was. I didn't like the labs. I didn't like the people who were majoring in chemistry. I didn't care for the professors. It just wasn't my cup of tea. So I changed over to a major in political science. And I enjoyed, always did enjoy the politicis and economics, that type of course to me were very interesting. I went to Rutgers.

Really in those days they recruited intensely. I had a letter from Lafayette to the effect that I was the type of person they would like to have which I know half my class got such a letter, because they were hungry for students. Really recruiting. As I said before, I couldn't afford the movies, so I was standing in the library one night in the stacks trying to get a book and a Rutgers football hero, the captain of the football team, no less, a real nationally known fellow at the time, came down in the stacks. He introduced himself and he said, "Is your name Leo Jenkins?" I said, "Yes." He said, "I want to talk to you about Rutgers." They had him out dragging kids in. I mean they just, they needed kids in order to pay salaries and keep the school open. They did some real fancy courting to get folks to go to college.

But they were rather strict, most of them, most to my knowledge. There were a few places that we knew were dumps, but most of them were rahter strict. A student must have, I think, at that time, sixteen Carnegie units: two in foreign languages, two in algebra, one in solid geometry, one in plane geometry, algebra, of course, four years of English. They made no exceptions generally. You had to have that to get in. You might rescue yourself sometime in summer school if you were shy a half a point or half a unit, but the Carnegie units were the thing. They didn't have SAT and that type of thing, but they did insist on the Carnegie units.

MB: Did you take some Education too?

LJ: Oh yeah.

MB: Did you plan to teach?

LJ: Yeah, I, I planned, I was planning two things, either to go into business or to make a living, to teach. It was impossible to think about going into business. I worked for Campbell Soup. I was in Rutgers. I was a window dresser. I dressed up windows on Campbell Soups and then went around to various supermarkets. Of course, they didn't have anything like they have today. There would be one in each county at the most. I'd put up a window with streamers and everything else and then go inside and put up a big display. Then I would prepare the man for a Saturday sale, which if you know what prices are now, we were featuring six cans of tomato soup for a quarter. Normally it was a nickel a can, so you were featuring it six for a quarter. Bread was genearlly the same thing, you could get five for a quarter. But now it is $.98 a loaf. It was kind of different then. And I thought, if I had gone with Campbell's Soup, Lord only knows, I might have made it or may not. You know, you don't know. But I would like to be in business, I'd like that, but I also wanted to make a living.

So I went to Philadelphia, to the agency, 'cause I found it was almost impossible to get a job without help. Every school I went to, there would be one or two jobs open and it would be a class reunion almost. I would go and meet ten or twenty of my friends that I graduated with, seriously, it was almost a class reunion. Then we'd say, "Where are you going to be next?" "Well, I'll be in Madison next" or "I'll be in Cranford next" or "Westfield." We'd go to all the towns and have a family reunion almost, class reunion, not family.

Then I got a little bit wise and went down to see the man in Philadelphia, Bryant Teachers' Agency it was called. He gave me several leads. He gave me a lead of Methodist Pennington Prep or some name of that type. But I didn't feel too comfortable there. Then I got a lead to go to Broadway. There was a club called the Seventy-Seven Steps Club. It was a club that took care of people who were lonely in New York and that type of thing and it was run by the Methodist Church. The man said this might be something of interest to me. So I was interested in it and I went over and tried to get that job, but I didn't get it. So finally, I was told that I might have a chance down in Atlantic City area. It was in Atlantic County, about five miles from Atlantic City. I went down there and they hired me. They hired me to teach senior English and Political Science. Of course, I had not majored in English, but it wasn't too hard to stay ahead, because they gave fifty-five non-academic students. They used to call them non-academic.

MB: Non-college?

LJ: Non-college, these kids could not go to college. They wouldn't be recommended because they made sure that they didn't get their Carnegie units. They were just students. And the other teachers had lesson plans and everything else and my instructions were to keep them busy. They didn't care. They were just potential trouble-makers, but in those days the teacher had complete control. If a youngster caused trouble, it would just be a question of throwing him out. No big trials or that type of thing. Not as it is today. It was rather difficult because they just couldn't possibly comprehend such things as a double negative. "You mean if I ain't got nothing, I ain't got nothing?" They would laugh like the devil, you know. So I knew after about three days that it would be impossible to teach Ivanhoe and the things that the state called for were impossible. So the principal said, it doesn't make a bit of difference to him. He said, "You just teach, just keep them quiet, just keep them busy." So I let the school textbook become Esquire and they thought that was a real treat, a wonderful thing. But the more I analyzed it, the wiser I thought it was, because number one, vocabulary. There's some very good stories in Esquire written by famous people. I'd give an assignment, find twenty words you've never seen before or do not know. Find ten words that you cannot spell. Tell me what you think of a story in there and how you would have changed it or whether you liked it or not. So they'd read it which they wouldn't read Ivanhoe . I knew that. Oh, there was another one we were suppose to have, was there one called "The Lady of the Lake?"

MB: Yes, another one of Scott's poems.

LJ: Yeah, Scott's "Lady of the Lake." They wouldn't even begin to look at that type of thing, but they did like this. They would look at the girlie pictures once in awhile and think that was real cute. But it was a way of getting them going on a thing. They would do something, just, rather than fight the thing.

MB: [says something]

LJ: Yeah, let them them fight the darn thing. It would even be good for composition. I would ask them to get up and tell me some advertisement you saw in there that you think is good, or bad or something. It got them going a little bit, which is more than I could say if I had tried to bang my head against a wall. The prinicpal didn't mind and the superintendent didn't mind. He'd drop by once in awhile.

Then I moved from there to Somerville, New Jersey. I was a teacher and doubled in brass as sophomore dean, which didn't amount to anything. It was just a title. But it meant that I had to watch the guidance of the men in that section. And that was very interesting. I taught American History there.

MB: Now these were still all men, boys?

LJ: No, no, they were coed. Down in Atlantic City was coed and Somerville was coed. Then, let's see, after that then of course, the war and the draft and I went in the Marines.

MB: So you went into the Marines when the war broke out? Were you married then?

LJ: Yes, I enlisted, believe it or not, I enlisted the day after our honeymoon. We were in the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York and then we moved up to the Hotel Taft the next day just to take a variety of hotels. By the way, a room for two in the Hotel Pennsylvania, the bridal suite then, was a terrific amount of money, $9.00 a night. I surprised Lillian quite a bit. I came back, I went to get a paper and I came back, I said, "You might not like this, what I did." She said, "What did you do?" I said, "I enlisted in the Marines." She wasn't too enthusiastic.

MB: Had the war started?

LJ: Oh yes. This was in 1942.

MB: in '42, well.

LJ: I enlisted in the Marines and they told me I would have to report whenever they sent me a notice. Unfortunately, I had to report Christmas Eve, which was rather difficult. Well, I wasn't the only one. We had a trainful of people. We arrived on December 24th at boot camp in Parris Island. It was probably the most miserable Christmas I can ever remember having in my life, because boot camp is not a pleasant situation. It is vulgar as can be and it's brutal. That's a better way of putting it. It's extremely brutal and savage, almost uncivilized. That was part of the strategy of trying to make a typical young fellow in three or four or five months, whatever it was, trying to make him feel he's Superman. That was the whole thing, you know. It started right from the beginning. I don't regret it, I'd never want to do it again. I wouldn't want my children to do it, but it didn't kill me obviously.

Now, between that time and Christmas, I had time on my hands, so I batted around as a substitute teacher. I taught elementary grades. I taught everything when a teacher didn't go to school, in many towns around there.

Then when the war was over, I came back and went again to agencies looking for jobs. I went to NYU and they sent me to Albright College, which is a denominational college in Pennsylvania. I think it was run by the Brethren. I came there and they wanted my wife to teach Sunday School and she was getting paid for nothing. But they had a list of assignments for her and they had a list of assignments for me. And I think they were going to pay me the grand sum of $2500. So I said, "Well, I don't need this after the war." So I didn't accept that position. I said, "I am going to take a job where I do the work and not tie in with the wife." So Montclair Teachers College in New Jersey was considered at that time, there was an agency that rated them, was considered America's number one teachers' college. I don't know if you have heard of it before, but it's called Montclair State Teachers College. Tuition was free to anybody in New Jersey, but he must or she must prove that they were capable of going there. So the very brightest youngsters went there seeking a free education.

MB: It was highly competetive, I guess.

LJ: Oh my goodness, yes. We had many, many more applicants than we did people that we admitted, they admitted. I taught Political Science there.

Then the State Department of Public Instruction in the capital of Trenton wanted an assistant to the Commissioner for Higher Education. So lightning struck and the gentleman who was in that department had met me at Montclair and he knew me as a high school boy, knew of me, and he recommended that I go there.

It was a time when having a Marine officer looked good. You see what I'm trying to say? It was the "in" thing to do. When I got the job, it was put in the paper rather prominently that a Marine officer is now assistant commissioner. You know, that kind of stuff. So I enjoyed it very much. And there I met Dr. Messick, who was the Dean at this school.

I went up there. The system at that time was run with a very strict central control. The Commissioner for Higher Education controlled, controlled right down to the curriculum. A school would not be able to put in a minor in French unless the commissioner said so. They would call down and ask, and it would be my job to go up and see what it was all about and discuss it and recommend back. And he'd go along with it. Or he wouldn't go along with it. It was that simple. IN doing this, I met many of the deans along with the president and if they wanted a pet thing and I saw that I could do them some good, I would do them some good. I recommended some things for Montclair that I thought were worthwhile and Messick would explain them to me because it was his job as dean to explain them to me.

My boss was a very sagacious fellow. He knew that I visited Princeton, I visited Rutgers. I sat in on a Board of Trustees meeting at Rutgers. And I went to Stevens Institute in Hoboken, which is a very distinguished engineering school. He said, "You know, one of these days some of these people are going to doubt your genius. You've never run a college before. You've never worked in one except a little bit up here." He said, "If I were you," he said, "if you can work it out, I'd take a leave of absence and go away for about a year and do something and come back." He said, "I'll hold the job for you." And it made sense, because here I was popping in on Rutgers and, you know, telling them different things.

So Messick got the job here at East Carolina and his dean fortunately, had retired, so it wasn't a question of firing anyone, taking anyone's place. It was a vacancy. He never said so, but I think that he wanted a chance to maybe to look around for awhile and I could be of. He knew my problem, because I told him that Dr. Morrison had suggested that I have some experience and, of course, anybody with any sense agreed to that. I got a letter from him which said the deanship is going to be open if you'd like to come down. So I talked to Lillian and we agreed in our own little planning to come down for a year.

MB: [laughs] For a year?

LJ: She said, "We might not like the South. They might not like you." I said, "Well, I've been down at Duke and people were nice to me when I was at Duke. There was never a problem." She said, "Well, all right, we'll take a crack at it." She came down and she cried for about a week. She had company, because Mrs. Messick cried for about a week. She didn't want to come down here, because Montclair was such a delightful city.

I mean, so many things existed there that didn't exist here. You'd go across the bridge and New York theaters, you'd go across the bridge and there'd be Sax Fifth Avenue and Macy's for shopping and all those things that you didn't have here. Even little things such as the bulldog edition of the newspaper. We could get the next day's paper the night before on the streets and everywhere.

They didn't have such things here. There were no supermarkets were here at all. The A & P would wrap up your stuff so you couldn't go and pick it yourself. You had to take it, the man would take it from the counter and bring it to the counter and then he would wrap it up in brown paper and give it to you. It was that kind of thin. No one had a supermarket. It was a dreary situation. The streets became absolutely uninhabited at 5:30 in the evening. That was the end of civilization almost, at 5:30 or so. And it was a different type of life. And we said that we would endure it for a year and then go back.

But then we began to learn there really was a genuine difference here. Except one, not unfortunate, but one humorous situation. I walked out to watch the boys practice some football. A department head, I don't want to name his name, but a department head came up to me and he said, "Are you the new dean?" I said, "Yes." He said, "You're a Yankee, aren't you?" I said, "Yes." He said, "I'll give you about six months." So I went home and I told my wife, and she said, "Is it going to be that bad?" I said, "No. He's just an exception to the rule, I'm sure." And sure enough, about four or five days later, they invited me to join the Kiwanis Club, which I did. I thought that they wouldn't be inviting me to join the Kiwanis Club if they didn't want me here. Then I was, I was voted president of the Kiwanis Club rather early, so I began to feel. Then, of course, everything was so, real nice. Where I went, people were extremely courteous.

Then I noticed a difference. I began to feel, "Is this real?" Because I never experienced that in the big city. I'd go in the store to ask for something and if he didn't have it, he would say, "Wait up, I'm going to call so-and-so and see if they have it." And he would call his competitor for me to see if he had what I was after. I said, "I've never seen anything like that in my life." Because you know, we didn't have that. You'd go in and they'd talk awhile and "Incidentally, what do you want?" It wouldn't be, "Hey, what do you want?" It wasn't the fact that they knew I worked at the university, it was just the person. They were extremely kind and courteous and that began to be a pattern almost.

Then I got the real shock. Because in New Jersey you would jokingly say, if one were to say he was going to Trenton, which is the capital, people would jokingly say, "Well, say hello to the governor." Well, that's not a joke here, because people say, "Oh! Do you want me to tell him something?" He is very accessible here. There it would be a joke, like saying to say hello to the President of the United States.

I was sitting in my office. I didn't even get up from my chair and a fellow came in, "Hello, how are you? How's everything?" I said, "Just fine." I thought it was some parent. I didn't get up or anything. I didn't say, "Can I do anything for you?" He went over and talked to the secretary for awhile and then went out and went to the next door. She said, "Do you know who that was?" I said, "No, I don't know who in the world that was." She said, "That's Governor Cherry." Geez, you know, normally, the governor comes to your office, you would jump up and shake his hand and everything. But he was so, he didn't make a fuss over the fact that he was governor, just walked around. And I went home and told my wife, "Can you believe a thing like that?" My goodness, if Governor Driscoll had walked in my office in New Jersey, you know, somebody would have been there with a horn saying, "Attention everybody!" We'd get a two hour warning that he was on his way. So that was the type of contrast that was . . .

LJ: Then I had one opportunity, real strong opportunity. Oh, by the way, the one year led into 32 years, as you know. We liked it more and more and more. Then we liked it so much that my wife didn't want to leave.

I was asked to consider coming to another state to be Assistant Chancellor for Academic Affairs. I went to see Frank Graham, who was a friend of mine, and who was also a Marine, although we never served together. But he was a Marine and I was a Marine. I could trust him. I told him, "I've been offerred this job to go to Georgia." He said, "Well, I know it's an opportunity for you and I know you're a young fellow," he says, "but if I were you, I wouldn't go." He explained the politics of the thing. He said, "You're being invited by the chancellor who is a very prominent man and a very powerful man, but if anything happened to him or if he were just to decide to retire, that would be the end of you. You'd be there at the grace of Chancellor Caldwell, it's that simple." So I decided not to do that. I've never regretted it.

Then, of course, when other things would come along, I'd ignore them unless I would discuss them with Bobby Morgan, who was chairman of our board, or whoever was chairman, I'd discuss it with him and then try to get no publicity for it. Sometimes it would leak out. But normally, I'd say, "I'm not going to do it, but I want you to know in case there's a leak.

We enjoyed very much the things that happened here. I know when they awarded me that Citizen of the Year Award about four years ago, five years ago up in Raleigh. I couldn't help but think, here were four governors here, Sanford, Hunt and Scott and Dan Moore; two senators, Bobby Morgan and Jessie Helms; Lieutenant Governor Jimmy Green; all these people were up there. Each one said about two minutes, and the only thing I could think of at the time I was there was the expression "Only in America!"

I don't know if you have ever heard that before, but I grew up in a foreign neighborhood. We were the only English family in the entire neighborhood. There were Germans, Polish, and Jewish people. Oh, we had most everything there. No Italians because they had their own community about three blocks the other direction. But in the middle was this conglomerate. The old ladies would sit out and talk and every once in awhile you'd hear "mmm, mmm, mmm" and they'd shake their heads. A story would come back about some fellow who made it big among the kids there and they would say "Only in America; only in America."

I couldn't help but think, only in America could a brazen, and I was brazen as hell when I was young, brazen Marine Yankee come down here and not only be welcomed, but to be up there. It made me think, no other place would that happen. But I just said that, "Only in America," and I sat down, because I didn't think the occasion called for a speech. But they've been delightfully good to me. There's no question about it.

Even during the hardest days of the Medical School fight, we were still able to be courteous. You see Dan Moore told several people, who in turn told me, of course, during the Medical School fight and the university status, he said, "The one man in North Carolina that I hate more than anyone else is Leo Jenkins down at East Carolina." So people would ask him to repeat it again. It wouldn't be because there was the spirit of drinking or anything, because there was none of that, too much. They would say, "Say that again, Governor." He'd say, "Yes, I'll repeat it as much as you want me to. The man I hate most in all of North Carolina is Leo Jenkins." And yet, when Lillian would meet with Janelle, the two wives would always hug each other. There was nothing between those two. When I would meet him, he would always be a complete gentleman and I'd be a gentleman to him. So it never got on the level of being ugly, you see. Even the people who opposed us in the legislature would come to the theater here. Ike Andrews is a good illustration, the congressman. He voted against East Carolina every time he had a chance. Not only voted, he made a speech every time he had a chance. Even when we had an issue won, when the vote was in our back pocket, when, you know, it wouldn't be even close and we'd run away with it, he'd have to get up and say, "You're making a mistake, please consider, they should not make a university down there. They should not have a Med. School." Everything they should not, they should not. Yet he came to the summer theater constantly. Whenever I'd have a dinner and he was invited, he'd be here and just as friendly, but, yet, difference in his attitude. So it was a very lovely and rather nice situation, although it was painful to some extent.

I think it cost me salary. I know it did. My salary was comparatively low compared to the other chancellors and I know why. We had the the second biggest school, no, third biggest school, the third biggest budget, the third largest in almost everything, and yet I'd be about the fifth, or sixth, or seventh when it came to salary.

MB: And you were one of the senior [chancellors.]

LJ: Oh, yes. I was the senior man. I was senior to everyone. Even in terms of, no matter what avenue they went. I know one fellow said, "Well, he doesn't write much." So I had [Wendell] Smiley, the librarian, make a study. And at the time that the remark was made, I had more publications than all of them, combined. Not just one guy or two guys, but all of them combined. I told Smiley, "Are you sure you did research?" He said, "I looked in Readers ," whatever they have over there, Index, Writers Index . "Every source there is, I checked." So I let that go.

Then they said, "Well, he's not a member of significant national organizations." Well, I was the member of COPA. And COPA is the accrediting agency in America, you see. They accredit the accrediting agencies. I was a member of COPA for five years. I represented all the state supported colleges and universities in America, all of them. They had one guy representing the professional, one fellow representing the private institutions, I forget, one representing the land-grant colleges. That was Sonny Body of the University of Iowa. They had the former governor of Minnesota representing the citizens. So it was a very prestigious type of committee. They knew that was rather foolish, no matter what avenue they tried, seniority, everything else, and they kept it low. I wasn't going to beg or go up there and say, "How come?" I could, many prominent people would have made an issue if I wanted to.

MB: I imagine that may have been one thing they were hoping you would do. Because it would have been [damaging.]

LJ: Then they would have said that I was selfish and that all he wants is money. So I ignored that completely. Even though people would ask me, "Let me go to bat for you." The Minges family wanted to go to bat for me. Many prominent people. I said, "No, I've got enough to live on and I'm doing all right. If I start in that direction then they're going to have another thing."

Then they used tricks, some of the papers. They knew that many of our followers were people who had not had much formal education, but were successful, self-made men and women. One paper started and another one picked it up, always attaching to my name "ubiquitous." Well, it was as innocent as could be, but there were many of my followers and friends who didn't know the meaning of the that word. And they would say, "Well, geez, I didn't know that about him. I never kew that." Others would say, "What?" You could tell by looking at them that, "I saw it in his eyes." Well, it's an old trick.

It's the trick that they pulled down in Alabama on Bankhead and other people when they said in effect, "Are you going to vote for a man who permits his daughter to go to college where men and women matriculate together?" Well, for a rural guy, you know, that sounds real bad. Then they pulled another one down there that they said, "His daughter goes to a college where the girls show their theses to the professors and the men professors at that." Well, you know, it sounds like the dickens. So I knew they were pulling that kind of stuff. Then they had a term, they used the term . . . Oh, let me show you another term, a fellow mailed it to me just yesterday. We have hundreds of these, they're old cartoons, negative. You've seen them probably.

MB: I've seen, well, there's a collection in the library.

LJ: There's a whole collection. This is my mail and this is my junk pile. A fellow called me and said, "I've got something in my files that I was going to throw away or mail to you. Do you want to have it?" I didn't even know what it was. It came yesterday.

MB: This is the Tar Heel , 1966.

LJ: yes.

MB: [Reading] The sly wall-eyed Leo Jenkins.

LJ: Yes, always some, always some adjectives.

MB: [Reading] The mighty midget Senator Robert Morgan couldn't stop at politics.

This is one of these [cartoons]. It is really remarkable that you've maintained a sense of humor over the whole situation.

LJ: I found that it helps. It absolutely helps.

MB: It's not easy sometimes.

LJ: Well, when the News & Observer , there are three papers that can help you, Greensboro Daily News , the News & Observer , the Charlotte and Asheville. If they're for you, you want to watch out, you lose friends. Really. I'd love them always to be against me, because there were many, many people who are standing out here in the middle, who are neutral as can be. They're not leaning any way. They just say, "Well, they've got a Med. School there." But they get mad, and everybody who was hurt by that gang has a kindred spirit. And they've hurt so many people through ugliness, through misrepresentation, through slanting the news, "that fellow has a companion in me." I'd had many people say, "Leo, I don't know which way this thing is gonig, but you can count on me. I don't know what this is all about, but you can count on me." They drove them to it. So I was happy because they could have killed me by embracing me.

MB: They weren't likely to, I suppose.

LJ: No, and yet, they are hard to understand. In the middle of our fight, Jonathan Daniels, you know who I'm talking about, the editor, he called me up and said that he wanted to see me. I had no idea what the fellow had in mind. He brought a photographer in. He brought the chairman of our board there, Henry Belk and he gave East Carolina his entire professional library. You see, he was, he was quite a writer and he was press secretary to Franklin D. Roosevelt and he had a good professional library collected. He is a Chapel Hill graduate and out of a clear blue sky, he gave East Carolina his whole professional library. The editor walked by who is always on my back. He looked in and he almost died. He looked in, his head went off his head twice. There was the photographer there, with Daniels with his arm around me here. The fellow really didn't know exactly what to think of it because he wasn't privileged to be told what was going on.

MB: Again, I guess, Daniels was not personally hostile to you.

LJ: No, I don't think he could care less, to tell you the truth.

MB: But their [newspaper] policies have always been . . .

LJ: Well, they always look for a problem. They also have the unrepresented generalization trick. Now Greensboro pulls that more than Raleigh.

[End of Tape 1, Side A]

LJ: And they played it down as much as they could, but they had to have some compensating news. So a fellow came down here and went back and there was a four column headline on the front page, DRUGS PREVALENT AT EAST CAROLINA UNIVERSITY. So I called the editor and I said, "Look, if this is true, I want you to share your information with me, because I'm going to call the head of the SBI. I want him to come down in strength. I don't want to cover this kind of thing up. If it is prevalent here, I want him here in strength." He says, "Well, let me, hold on a minute." I said, "What's your evidence?" He said, "We don't have any evidence. We sent Joe Blow down," or whoever he was. "He talked to a student," now, don't forget, one out of 12,000, "he talked to a student there and this student said that he thought that about half the people there were on drugs." I said, "Is that the basis for a front page, four column headline?" He said, "Well, you know." I said, "You know better than that, don't you?" I said, "You're a graduate of journalism from Chapel Hill and you know better than that. That's not a representative sampling." I said, "That's really punksterism and you know it." He said, "Well, you know, you're too sensitive." I said, "I'm not sensitive. I'm just interested in fair play. I'm thinking of the parents of these youngsters who read this nonsense which you know is not true." Then you can't win that kind of argument, but that's the trick, you see, the unrepresentative sampling.

Then he came down, another paper and they grabbed different students, "What is there about East Carolina that you do not like?" One kid would find this and this and this. If they could do that in heaven and ask "What are the things you don't like in heaven?" you know.

So I called this man and I said, "What if we send someone down there now to your paper and I went through the press room, advertising room, and business office and I were to say to all of them working there, "What is there about this paper you don't like? I'd get a list of things, wouldn't I?" I said, "Would you make a big story on that? Because I'd be happy to do it if you'll make a big story out of it." He said, "Well." It was bad journalism and he knew it. That type of thing gripes you a little bit, you know, when they pull this nonsense of the unrepresentative sampling.

They'll do that even with statistics. To illustrate a point: They'll say, East Carolina has lower scores in teacher exams than does Davidson. Well, then you look closer. There'd be six kids that took the exam at Davidson and there'd be four hundred here who took it. So I told the press, "You think that's fair?" He said, "Well, it's percentages." I said, "Let's put it this way, I'll put our first six against Davidson's first six." That's their whole gang. We would have beaten them at that, because I checked before I brought this up. I said, "Do you want to do that? Our first six against their first six." "Oh, no, we can't play it that way. We go by percentages." Well, he knew what he was talking about.

It's like the boy, the chancellor at one of the colleges told me, that there was a youngster bragging about being salutatorian. He said that it just annoyed him because the kid was just dumb. He didn't even know if the kid could write his name, he was that kind of dumb. He finally got hold of him and he said, "Look, have you been bragging about this stuff?" The kid said, "Yes, sir. I'm not lying. I was salutatorian." Well, to make a long story short, he graduated from a little mountain school that had two students. So, of course, he was salutatorian.

MB: He couldn't lose on that one.

LJ: Of course, he was. He wasn't fibbing one damn bit.

MB: Well, from your experience and observation, why do you think there has been such an attack on East Carolina over the years?

LJ: Well, it really isn't East Carolina. I think it's the region.

MB: We reflect [the region]?

LJ: We reflected a region that people considered backward. People would grow up here and then leave where opportunities were, the Piedmont. They would be successful and once in awhile come back and visit grandma or visit mama.

But the best way I can illustrate it. My very first experience in the legislature, way back, a friend of mine was my tent mate in Guam in the Marines. He had gotten in the legislature and we never knew we would ever meet each other in North Carolina. We were rather friendly. He called me aside, we had a request for $40,000 for an organ to be put in Austin . This fellow said, "Look now, you know that I'm going to vote for this thing, but tell me as buddy-buddy, you and me. What in the hell are they going to do with a damn organ down there?" He was very sincere. He was a North Carolinian. I said, "Well, Bob, you know darn right well they are going to do with it the same as you do up here. They're going to play it." I said, "I think frankly that they are going to play it better than you do up here." I said, "Because their Music School can top anything I've seen around Raleigh." He said, "Well, I'm just wondering."

They just didn't think that quality existed or anything worthwhile existed and the rumor was that they don't have shoes yet. They were emerging from a very, very bad press, if you want to. And yet, when I made speeches at Goldsboro and Winston-Salem and Charlotte, I'd always have to remind them that this is the birthplace of the nation. This is where Virginia Dare did her thing. I said, "They were writing poems here. They were writing books. They had commerce. They had military. They had transportation. They had all these things when you were a wilderness." Which is true, a real wilderness. I said, "Here you look upon them as real Tobacco Road and of course the play Tobacco Road didn't help any.

MB: No.

LJ: You know that gave the picture that things were funny. I said, "But it isn't that way anymore. They're very sincere, lovable people." I said, "In some cases, some may appear unsophisticated, because they haven't been in your circles. They don't think it's cute to do some of the things you do. They are Sunday School folks, if you want to put it that way." And a lot of them were in those days and still are. I said, "That doesn't mean they're not deserving." I said, "Also the good things of life should never depend on geography. I mean, who do you think you are? They pay taxes, they pay their dues. The people far out west pay their taxes. Shouldn't they get the same as you have? Why should it be exclusively yours?" Well, that philosophy existed so long.

Another thing, politically, the East was taken for granted. A Republican was unknown down here, except down in Sampson County, that was a nest of Republicans, Sampson County. Therefore, they knew that they didn't have to do anything but come here. If a fellow wanted a primary in the Democratic Party, he could count on here. There would be no desertion of the party. So he would promise them roads. He'd promise them everything, but not fulfill it. So now, for the first time, we were seriously asking them to fulfull the dream, their promises, that we wanted party action. Now this annoyed a lot of people.

MB: I guess also thinking that it would cut the pie in smaller pieces.

LJ: Oh yes, definitely they thought that.

MB: Do you think it's valid to suggest that East Carolina has had a tremendous impact on the structure of higher education because of pushiness and the rest of the establishments attempts to . . .

LJ: Yes, they joined in with us, but I think the big thing that we had to get over, and we still are going to have to get over with it, is the fact that our best weapon is going to be honesty. Keep hitting honesty.

To illustrate my point, and I almost had to call their bluff. They put out the word, "You have umpteen Ph.D.'s to be sure," because at that time we had a higher percentage of Ph.D.'s than any of them. You see we were up to about 50% or 51. When you take all the graduate assistants and this and that, we had more Ph.D.'s than they did. They put out the word that we had Ph.D.'s, but they really aren't Chapel Hill style Ph.D.'s. They aren't, they are ersatz Ph.D.'s not the real McCoy. So I made a study of it. I had [Robert] Holt make a study of it. We found out that we had some forty or fifty Ph.D.'s from Chapel Hill, so I called back up there. I said, "Well, I'm going to take your word for it." I said, "I'm going to ask the board at the next meeting, number one, every Ph.D. who's not tenured from Chapel Hill is going to be fired. We are going to have a constant rule, we never hire a Ph.D. [from Chapel Hill]. We like them. We think they're good. But you say they are ersatz, so therefore, I'm going to take you at your word." "Oh, hell, you can't do that." I said, "The hell I can't. You said it. I didn't say it." "Well, you know, whoever said that didn't mean it." Oh, geez, they backtracked so damn fast that they didn't know what to do.

Then Governor Hodges, who was exceedingly close to the university and didn't care too much for here, as a matter of fact, he said to his friends that he didn't care for what was happening down here. Because this part of the state didn't support the Research Triangle the way he thought they should. He put out the word that the SAT that the youngsters who enter here take is different from the SAT's they take in Chapel Hill. Well, I wasn't going to fight that battle, so I called Princeton. I said, "You fellows are selling this thing. You're getting paid for it. You're getting paid well. Our governor says that you have two varieties, one easy and one hard. If that is true, you ought to tell us that that is true. If not, you ought to defend your own product." And boy they did. They put out a story on the AP and UP and everything else that there isn't anything except one type of SAT. There isn't a hard one and a weak one and that type of thing.

Then another thing we had to fight very desperately in North Carolina. I don't know where it came from. Yes, I do know where it came from. But the people were talking in terms of the pyramid type of education. There should be, the apex should be Chapel Hill, State, maybe State. Hisotrically State wasn't in the act. Historically, State was a junior college and they had a very, very tough struglle to bring engineering over there. People didn't want it to go over there. So they said the Woman's College and Chapel Hill should, and State should be the apex. They should be at the top. They should have the most money. They should have the best instruction and the most difficult courses. In the middle would be East Carolina, Appalachian and maybe West[ern] Carolina. At the bottom of the apex should be the black colleges and the Indian college, Pembroke.

Now, I had, and many of my friends, had to fight very hard to prove the foolishness of that. We said, number one, there is no such thing as easy algebra, medium algebra and weak algebra. There is no thing as easy French, medium French and so forth. I said, secondly, they all pay taxes. They are all entitled, every last person who goes to a publicly supported school is entitled to the best, not the weakest. I said, thirdly, they all mean professional school together. So are you saying now that the man who wants to be a physician, who is at the bottom rung is going to be sort of a weaker physician? He won't really know how to take care of you when you are sick? He's going to be a weak lawyer, he's going to be a weak engineer, or an architect, and this guy is going to be a good one? I said, life isn't built that way. It doesn't work that way. They all must have the same type of education, be supported the same.

I'm willing to admit certain types of instruction is more expensive than other types. I know it's more expensive to train an engineer than it is a kindergarten teacher. We admit that. But if you're going to train engineers in three colleges, they all ought to get A - Number One instruction in the three colleges. If you're going to train public school teachers in ten colleges it ought to be the best in ten. Well, that was a tough thing to fight because per capita appropriations followed that theory. There would be many, many hundred dollars more at the apex and many, many hundred dollars less down here.

We finally got rid of that to some extent. I think most people now agree that East Carolina can hold its own in almost any discipline that I know of with any other college in North Carolina. I really do. Our doctors have proved that. They're as efficient, they get just as high a score as they do from Chapel Hill. Our nurses have proved that. Any place where there was a comparison, we have been able to prove that. The little schools are proving that. The kids from Campbell do as well as the kids from any place else. We are getting a little bit more mellow, a little bit more understanding.

MB: Do you think there is less sectional rivalry now?

LJ: Oh yes.

MB: Out of the, what, just progress and the general development or out of the consolidation?

LJ: It still lingers, there is no question about that. I think there is an element of either we are fooling ourselves or we're being dishonest when we say that education must be pulled out of politics, there is no place in politics for higher education. All one has to do is look at the Board of Governors. They are appointed politically. They get there politically. They fight for the job politically. And when they get there, if they can use it, they use it. I mean, some are lobbyists. They take care of the people they are lobbying for. We see illustrations of that constantly. That goes, that's part of life and to say that we have to remove that or that it doesn't exist, we're just not being honest. And you're not honest with the students, because they see throught this more than we think they do. Much more than we think they do.

MB: Let me back up a little bit. You've mentioned, well you graduated from Rutgers, but you also graduated from

LJ: Columbia

MB: Columbia

LJ: and NYU

MB: and NYU and you went to Duke.

LJ: and I went to Duke. It happened very interestingly. When I was teaching in Somerville [New Jersey], Doris Duke lived in Somerville where I was teaching. Some kind of deal came along where we could go to summer school at Duke at a reasonable price and so forth. I didn't know much about Duke at the time. It was formerly little Trinity. I went down there and took statistics and some other course, I just don't recall now. Oh yes, techniques of research and statistics. I enjoyed being there. It was a very fine situation.

But they were struggling then exactly the way East Carolina University was about 25 years ago, exactly. There were people who said in effect, it didn't mean much to me then, but as I look back it is so meaningful, as I look back. They said, "number one, this little Methodist dump will never amount to anything, little Trinity." They had a two year medical school or the beginning of one. And they said, "They don't even begin to train doctors like they should." So Duke retaliated. They brought in a man who was going to give them a respectful athletic program, Wallace Wade. I got to know him very well there. They brought in McDougall, the social psychologist, who was world famous at that time, they brought him in. Then they brought in Dr. Ryan for the extra sensory perception business. And they were the things that gave them academic headlines and athletic headlines.

And I watched them develop and they moved along and were doing, doing rather well, I thought. But they had the gang nagging them. They nagged them worse than they ever nagged us. Really, it was almost a pattern of previous times. That was why a lot of Duke people

MB: were very sympathetic

LJ: were very much with us, my friend, a lot of them. And gosh, the man who graduated, the first medical graduate of that institution was a fellow named Dr. Lenox Baker. He was head of orthopedics up at Duke. He was one of the biggest champions of this Med. School.

And their retired dean, wish I could remember his name now.. Anyway, their retired dean of medicine

MB: was supportive put the word out that we were doing the right thing and that we should continue this. Dean, I'll think of it in a minute. That's easy to find. But he didn't want to go public, because he was the head of a foundation that had a rule that the man in it must be out of politics and this was considered politics, you see. So he would hurt the foundation, and therefore, he had to stay out of it completely. [phone rings] But they were sympathetic. They knew what was going on. They knew the struggle we were having. Anyway, that gave an inspiration.

Now another thing that gave an inspiration, a young fellow that went to high school with me and I knew him very well. Then he went to Yale subsequently, medical school and so on, and he became the head of the Department of Medicine at Chapel Hill. He came down one Saturday morning. I hadn't seen him in 25 years. He came down one Saturday morning and I happened to be in the office. And he said, "I just stopped by and wanted to make a comment." He said, " What you're doing is right. Don't give up this fight for the Med. School. We need it. You're doing the right right thing. You're on the right track." I said, "Lou, if I could quote you, we'd be ahead. We'd be way ahead." Louis Welt, his name was, Louis Welt, W-E-L-T. He said, "No, I'm not going to get involved in this struggle. I've got my own headaches and I'm not going to be involved. But I'm telling you, and I'm going to deny I told you if you make it public, because it's personal, confidential, just you and me." Then I gave him a yearbook for his children. I said, "They might like to see the football heros and all that stuff." So I gave him a yearbook. But that made me feel that I'm not screwy. You know, here he's an internationally famous man, known all over the medical profession thoughout the world. He was well-known and very popular.

Then I got another reading that some of this so called antagonism was not really complete and it was not on the part of most people. I was invited to speak to the AAUP at Chapel Hill. People said, "Oh, they are going to tear you apart." I went up there and it was the nicest situation that I have seen in a long time. They had this reception.

More and more people began to come to the forefront. You know, people understood this thing. In the first place, when Dr. Ferguson came to my house one Sunday afternoon and I wasn't there, he gave Lillian a big lecture about [it]. He said, "The motto of this school is 'To Serve.' You're sitting in the middle of the worst medical situation in all America."

I never dreamed of that, because I had for a pediatrician, Malene Irons . I had a doctor Fred Irons and I never had any trouble. If a kid had a headache, they would come to the house, no trouble. So I didn't see what was going on. I was too blind. He said, "It's terrible," so on, on the Q.T. "You ought to do something about it." That's what he told Lillian. Then I finally got him on the phone and he told me the same damn thing.

So I got hold of Bobby Morgan and I told him. He said, "Well, why don't we look into it?" I said, "Well, let's look into it on the Q.T." So, I don't know if you know Bob Williams?

MB: Oh yes.

LJ: Well, I thought I would get a real sharp Ph.D., and I consider Bob sharp. I said, "Bob, study this thing on the Q.T. This guy says that we're this. He says that we lead the nation in infant mortality." This is Eastern North Carolina now. "We lead the nation in suicide. We have the worst doctor-patient ratio in the nation of any region. And we have the worst bed-citizen ration of anybody in the nation. He said, therefore, you'd have to say the worst region in the nation for modern medical delivery is Eastern North Carolina." I said, "Geez, I can't believe that." So I said, "Go out on the Q.T., just you know, find out." So he went out and it took him several months and he came back and he said, "Everything that guy said is true." He says, "It is not only true, it can be documented." I said, "Well if that is the case, I'm going to get a hold of Morgan."

I got hold of Bobby and I said, "What do you want me to do?" He said, "Well, let's put it to the Board." So I took it to the Board and they instructed me, pursue the establishment of the Medical School. That's it, pursue it! I said, "Well, you know the roof is going to fall in. Chapel Hill is going to scream and they have access to the editorial writers and they'll just call this one, that one, this one. There will be cartoons, editorials, the ugliness. It will be a mean, mean situation." I said, "Frankly, I don't care." You know, I'd been through the Marines and all that stuff. I didn't care for a little roughness like that. He said, "Well, if you want to do it, go ahead."

So we tried it and sure enough. The very first time I let it be known, good gosh, came the cartoons, editorials. And then they hired so-called experts who were hired to give the right answer. You could almost smell that. We said, "Well, in spite of what you do or anything else, we are going to go on and pursue the Med. School."

One interesting thing was very cute. They brought down the retired dean of Cornell School of Medicine and they had a meeting with the Board of Governors. That's right before we got the Med. School. And I went up there with [Ed] Monroe and [William] Laupus, guys who understand what they're saying. I'm not a medical trained person. So, believe it or not, they wouldn't let those two come in the meeting. They barred them, made them stay in the hall. I, alone, was allowed to come in there.

Then this guy got busy with his nomenclature. And he said in effect that Cornell is internationally famous and they could not get a chief in pathology. They could not get a chief in physiology. They could not get a chief in radiology, blah, blah, blah, blah. How do you expect to get it down there in Greenville? And he raved on and raved on.

But he forgot to mention one thing, Cornell Med. School is located in Harlem. Well, what man is going to go to a crime infested area and work when he can come here? When you consider the federal tax situation, when he can carry home about the same money here. Go out and play golf as I did this morning, no wait, just go out and play. Go fishing, saltwater or fresh water. Go to the beach. Go skiing and live among nice people such as the people out in Lyndale and Brookgreen where the doctors are living, as you know. Who wouldn't rather have that than to commute to Connecticut or to commute over to New Jersey. And be afraid to go to your car in the parking lot if it gets a little bit dusk? Who wants to live that type of life when they can live this type of life? So, I knew that we would have no trouble to compare with them. There would be ten guys here compared with one up there. And that was the case. We've had no trouble getting very famous people to come here, because lifestyle today is very important to professional people. We knocked down that argument. Every little petty road block that was thrown in our way, with the help of the legislature, with the help of our friends, we knocked it down.

MB: Tell me, in the actual mechanics of this, was it Bob Morgan who was the legislative organizer ? Or who all was involved?

LJ: It was a combination of many. It is very difficult to put your hands on any one person, including myself, because it's really a great team effort. I can think of such people as Ken Royall. And here I'm going to leave out someone sure as I tell [you].

MB: Yes, I know that.

LJ: I can't catalog them because there were so many of them that played little parts when they were needed. When these little parts were needed.

MB: Was there an overall sort of organization?

LJ: Yes, we had a Committee of Fifty. This Committee of Fifty was composed of newspaper people, some doctors, some prominent politicians, and we would meet periodically. We had, one was a doctor on the Board of Trustees at Duke, Dr. Tannenbaum. Others were people who just knew we needed this and volunteers themselves. Dr. Santee and Joe Parker, the newspaper fellow. Denning up in Henderson, a 91 year old man, would come in every time we needed him. [He] would come in with a beautiful editorial which I could photostat and use to counter some of the junk.

And this Committee of Fifty really held together. It was almost like orchestrating an orchestra. You had to constantly, it dealt with tickets to the ballgame. It dealt with tickets to the summer theater. It dealt with getting kids into college, not only here, but in other places. For example, if a person had a child who just shouldn't come here, but that person was one of our best friends, let us say. What do you do with them? Well, you can't say, "Well, you shouldn't come here." But you say, "Look, I'll get him in at X place because I think X would be much better for him." And most men would fall for that, you see.

MB: They would appreciate your interest.

LJ: They'd appreciate it. And we'd go out of our way to get them in X. But that took a lot of effort. You had to court and you had to orchestrate and you also had to develop the philosophy. People would come and say, "What do you think of this?" Negative. "What do you think of that?" I'd say, "Look, fellow, I've always made a practice not to chase every rabbit that runs across the highway. I just can't." I said, "There are too many of them running across. Furthermore, this is a democracy. A fellow has a perfect right to say that I'm no good. He has a perfect right to say that I'm evil or whatever he wants. As long as he doesn't hit me with a bat or shoot me, he has a perfect right to do that, you see." I said, "Also, it takes two to tango and I have no intention of getting that guy's name in the paper by tangoing with him. So let him say what he wants. It'll drop dead with that issue unless I keep it going."

MB: Yes.

LJ: I have no intention of keeping it going.

Now once in awhile you have to do some tricks. To illustrate my point. We had quite a bit of opposition from some of the wealthier people or let's put it, more influential people, probably, in Winston-Salem. So Gordon Hanes invited me up to speak to a service club and it was very interesting. He introduced me and I thought that I was going to get really shot down. He said, "This crazy man who is our speaker today thinks there ought to be a medical school in the East, and this crazy man thinks they ought to have a university there." And he went on and on. He said, "But, I want to tell all of you one thing." He says, "I'm behind this crazy man 100%." Well, those fellows didn't know what the hell to do, you know, because he's Mr. Big.

MB: Yes.

LJ: I didn't, frankly, I was afraid until he got to that last line. I thought, "Here I am." So I used an approach that some old fellow said. He said, "You're a sly," he called me a son of a bitch, "you're a sly son of a bitch." What I said was, "All right, let's assume that you use all your influence and you definitely convince enough people in the legislature to keep us from having a med. school. And you keep us from having a university. And you keep us from having a nursing school." I said, "then let's assume that they would want to honor you. Do you think they would have a parade where they will say, 'Here's the guy who kept East Carolina and all the people in the East from having a med. school'? Can you visualize such a parade?" Of course, they couldn't. I said, "Let's go further. If your grandson says to you when you get a little bit older, 'Grand daddy, what did you do in the history of North Carolina that you're real proud of?' Are you really going to tell him that, 'Yes, I'm proud of the fact that I kept the East from having a med. school, I kept the East from having a university'? Would you be proud?" He said, "That's a hell of a way to put it, do you know that?" I said, "Well, isn't that true? Would you be proud? Would you like to tell your grandson that?" Then he realized, of course, what were [doing].

I had another opportunity. There were some newspaper men who had been practicing punksterism for a long time and they just happened to be invited to be guests when I spoke at this service club. So I knew why they were there, just to be smart alecks. So I digressed from my speech completely. I said, "It's a shame that a beautiful state such as North Carolina has to live under punksterism." And I went on and told them what punksterism was, unrepresentative sampling and all these little tricks that had been pulled.

And one reporter called my boys when they were in the dormitory. My one son is an M.D. out of Chapel Hill as you know. My other son has two degrees out of Chapel Hill, an M.B.A. and an undergraduate. They called them in the dormitory and said, "Don't you think you've got a lot of guts going to Chapel Hill when your father is trying to destroy the university?" So the kids called home and said, "What should we do with calls like this?" I said, "Very simple. Any time you get a call like that, tell them to go to hell and hang up." So then I called, not the editor of the paper, I called the owner of the paper and I told him what happened. I said, "I'm not asking you to stop it." I said, "I'm just telling you that if it happens even one more time," I said, "I'm going to get a platform at the next meeting of the North Carolina Press Association. They like sensationalist junk. I can get such a platform without a bit of trouble and I'm going to document what your paper has been doing. And I'm going to say, 'This paper probably won prizes in the past. Is this the kind of slob you give a prize to?'" I said, "I'm going to use those terms, if you want to go along with it." And he didn't. He was very indignant, not at me. He said, "I'm glad you called." He says, "That will never happen again." So, he was a real gentleman.

Then I called Bill Friday and I said, "Bill, I don't want you to do a damn thing about it, but I want you to know," I said, "if your daughters were here and that happened," I said, "you can rest assured that I would be at that paper." I've got to give him credit. He was also indignant about it. He said, "That's a hell of a thing to do. If it happens again, you let me know."

And incidentally, he and I have been friends throughout all of this. That's the God's honest truth. We've never had a harsh word. He has never once been unkind to me. He has never once raised his voice, never once reprimanded me. And I in turn have never, ever said anything unkind about him. People tried to put words in my mouth. They would say, "Don't you think Friday's manipulating this?" I'd say, "No, I don't think that." I'd say, "I am just not going to be the judge of someone else or the referee." It has worked out very well this way and we respect each other. He has been very good. When our children graduated there, he came over to make sure that the kids got their picture with him and that stuff, you know.

MB: When you first came to Greenville back in 1947, they were just getting over the [Leon] Meadow's problem. Do you think that had much effect on East Carolina, other than the immediate impact?

LJ: No, it was very transitory. I don't want to say fortunately or not, but I'll illustrate what I'm trying to say. People were divided right down the middle on that, on the campus they were divided, in the city. I went to a church. I was the preacher at an annual homecoming and people came from all directions. They couldn't fit into the church, there was such a crowd. It was over in Johnston County. That name came up because they knew I was from ECTC, at that time. They said, "What do you think?" I said, "Honestly, I don't know the man. I haven't followed the case or anything." I just couldn't make an opinion. Then, bang, the arguments started, and I dare say half of that gang said, "Well, here is an innocent man that was railroaded." And the other side was saying, "nothing but a damn crook and he got caught." So that was right in the middle. But I don't think it had a bit of an effect. Because the effect of the G.I., the men coming here, the war, strangers coming here, and the Yankees coming here, and everybody else, that made it a new ballgame and everybody could have cared less.

MB: It changed after [the war].

LJ: I never even talked about it. Once in awhile an old timeer would come in and say, "I remember when Meadows was here." But it really had no effect at all.

Another non-entity, a fellow stayed here about a year named Cooke

MB: [Dennis] Cooke.

LJ: and didn't make any influence on anybody. I never heard anybody say they even knew him. I knew him very well. He was a pretty nice fellow. He went from here to Woman's College and became a professor of business, no, education. Then he went to High Point and he was president there until Wendell Patton took over. I think he did a pretty fair job, but he wasn't happy here. It was obvious, he wasn't part of here.

An interesting thing did happen, however. I lived a year here with the post office closing every day about 6:30. You could get mail after 6:30, and I'd rush to my office to make sure I got my night mail. I thought it was a governmental regulation. Finally, I asked one of the veterans here, "Why in the world, other college, you can get mail at eleven or twelve o'clock at night. At Duke, when I was there, I could get my mail at any time. Here it is 6:30. Is that a regulation for rural post offices?" He said, "No. Dr. Cooke closed all post offices at 6:30 because he felt that if the boys and girls go there to get their mail, they might smooch." Now isn't that something?! I said, "I'll be darned. From now on, open the thing." Now, of course, we open it. You can get it any time you want. I was only dean then and I opened the thing. [John] Messick didn't care. He said, "Why keep that thing closed with a reason that silly?"

They had so many silly rules. A girl could not wear bermuda shorts even to play tennis. She had to wear a raincoat until she got to the tennis courts, then she was allowed to take the raincoat off. Then put the raincoat back on again and go to her room.

And girls were not allowed to ride in a car with a man, a male. Believe it or not, I went to get a girl to babysit for us. We had two little boys then. And they said, "I'm sorry, but she may not ride with you." Really.

MB: With the Dean.

LJ: No. I had to go back home and get them. I said, "We don't have a babysitter. She's not allowed to ride with me."

One lady in town here was barred from the campus for life, I understand. She explained it to me. You know what terrible thing she did?

MB: No.

LJ: She brought a birthday cake to her daughter, but she forgot to sign in. She didn't sign in downstairs and she brought the cake up. And they barred her, they barred her from being here. So we went from ridiculous, almost to the crazy stuff.

MB: When you were here, then as Dean under Dr. Messick, many of these things came before, under your province to do away with a lot of these rules.

LJ: Yes. He gave great freedom. I had a great element of control there which I think is common. Frankly, that's the way it should be done. You've got to delegate and give people, they've got to be in charge. Otherwise, they are not going to do their best. And this business of a tight administration, I never did believe in it. Because, if you've got a sly person who wants to cheat, he can do it whether you watch him everyday of the week. He can do it. I've known people who pulled all kinds of tricks.

One student came to me one day and said a certain professor, "I wish you wouldn't call him to your office so much, because, honestly, we just don't get started in this. He comes in and says that he can be with us for five minutes because 'Jenkins wants me for a conference.'" He said, "That will be two or three times a week, you want him." I had never even called the fellow once. So, just by luck, a student [told me].

Then we caught another fellow. So as I say, no matter how tight you think you can have it, it's got to be based on honesty or you don't have it.

This girl came in and she said, "I want to make a correction on my records. I had appendicitis the first week of school and was out the whole semester and I got an A on this subject." So I called the fellow and I said, "Did you have a girl in your class?" whatever it was. "Oh, yes, a very good student." I said, "What did she get?" "She got an A." Then I explained, I said, "Do you realize that she wasn't even in your class?" The guy admitted it. He said, "Well, you don't blame me." He said, "What the hell?" He admitted that he did that.

Then he gave another guy, he gave everybody an A and a few B's and we soon began to suspect. Because one boy's record was all D's. This subject was English as a matter of fact. How can he get all D's, D, D, D, and an A. The guy admitted ot me after awhile. He said, "Frankly, I just threw the damn mess on the stairs and everybody, all the A's were the first eight flights and the B's were the second." All kinds of crazy things you had to deal with.

[interuption in interview deleted]

Well, a good illustration is in Art, [Edward] Reep and [Donald] Sexauer. Then we've got a man in sculpturing, I've forgot what his name is. He does it in, [Wesley] Crawley. I asked Crawley, "Why did you come here?" He came from Oregon. I said, "You make a hell of a lot of dough making these statues for the banks." He makes marble heads for children. He doesn't have to be near here. I said, "Why are you here?" He said, "I'll tell you the God's honest truth. I'm here because I'm free. You've never said anything unkind to me ever and neither has [Wellington] Bud Gray." He said, "It's fun working in an atmosphere where you don't have to fight all the time. You don't have to be in the middle of a lot of junk. I'm just a loose soul." Of course, he gave us our money's worth. He was a good man.

And all these fellows, if a person wants to write, they're going to write. You don't have to force them. And if you want, if you want, to have that publish or perish, it's so easy to beat. You know the formula. You can write an article on what you are going to do, then write an article on what you've done and then write an evaluation. You can milk it for three. And you can always get some jerky publication that needs articles, no problem with that. So it really doesn't amount to a row of beans.

LJ: But you take a guy like Ovid Pierce , no one told him to write a damn book, but he had it in his soul. He wanted to get it out.

By the way, talking about newspapers and Ovid, here is another illustrtion of how it works. Ovid won the legislative award. He had been here twelve years at the time that he won it and there was a big editorial in the Greensboro paper. The first winner was a professor of chemistry at Chapel Hill, completely identified. You know, all about where he taught and everything. Then came the philanthropist and all about her. She was from Greensboro. And then came Ovid Pierce of Greenville.

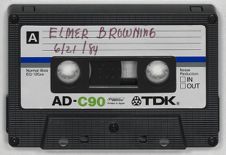

[End of Tape 1, Side 2]

Anyway, to make it even more ridiculous, the chairman of the committee that chose the recipients was the senator. So I said, "You are going to tell me now Bill that you picked a guy and gave him this great award, you had no idea where he worked? What he did?" He knew. I said, "You knew darn right well. You kne that he was a professor here for twelve years. You knew that he came from Tulane, but you weren't nice enough. You weren't man enough to give credit here, because you let hatred come in here, which isn't good. It is not a compliment to you."

I said, "You knew darn right well that we would have been proud to have Ovid Pierce identified. He's a winner and he's also a professor here. Now if he had got in trouble, some embarrassing type of trouble, you know darn right well the headline would be EAST CAROLINA PROFESSOR GETS CAUGHT ROBBING BANK, you see or somehting of that type." I said, "Now why can't it work for the good part?" He said, "Oh, you're just sensitive over nothing." I said, "No, I'm not sensitive over nothing at all."

Then sometimes you catch them in lies. They had a real unkind editorial which was based on lies. I forget the paper. I called the fellow. I said, "You know this is absolutely not true. You know it's not true." He said, "Well, that was written by a cub reporter and he probably didn't know." I said, "You're going to tell me now that you have one of the major papers and you let a cub reporter write your editorials?" I said, "You know better than that, don't you?" He started to laugh a little bit, you know.

But you've got to let them know once in awhile that they're not pulling anyting over on you, that you know your way too.