[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

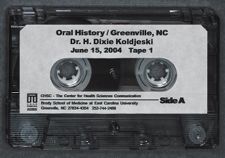

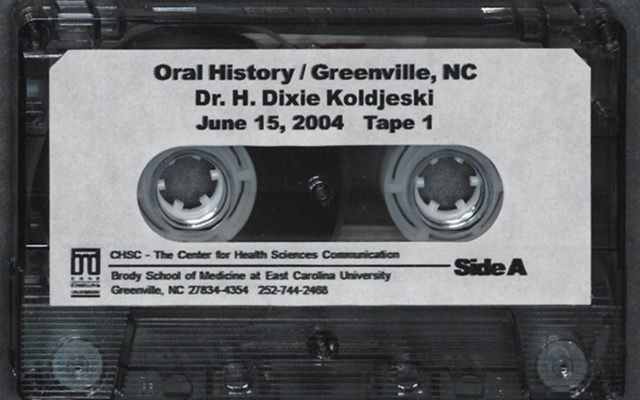

Collection Number: 3.8.5

Date: June 15, 2004

Narrator: Dr. H. Dixie Koldjeski

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop, PhD

Transcriber: Janipat Worthington

(Note: "." denotes a cassette recorder malfunction)

Copyright 2001 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

Ruth Moskop:

Today is June 15, 2004. My name is Ruth Moskop. I am here with Dr. Helen Dixie Koldjeski at Quail Ridge, 2043-G, in Greenville, North Carolina. How are you Dr. Koldjeski?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Oh, fine.

Ruth Moskop:

Good! The purpose of this interview is to learn about your career as a healthcare provider and teacher, with particular emphasis on your career in Mental Health Nursing and your role as a scholar in that area. This tape will eventually be transcribed and kept at the Health Sciences Library of East Carolina University where it will be available as an oral history resource for people interested in the history of healthcare. Dr. Koldjeski, do I have your permission to record this interview?

DK Yes, you do.

Ruth Moskop:

Thank you very much. Would it be all right with you if I ask you for a little bit of biographical background to begin?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yes.

Ruth Moskop:

Thank you. Tell us when you were born and where you were born.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I was born in Pitt County, the county that we're in right now, and I was born on a farm outside of the little town of Grifton in 1923, and I lived there on the farm until I was 16 and a half years old.

Ruth Moskop:

Could you tell us a little bit about your grade school experience?

Dixie Koldjeski:

I went to a little country - what would be called an elementary school, I guess, today, that is on what is now Highway 11 between Greenville and Kinston. It had three grades, and it was taught by a - the teachers there consisted of a lady who lived in Grifton and her two daughters, both of whom were teachers. I stayed there until I completed the third grade. Then when I went to the fourth grade, I transferred to what was called Grifton School in the town of Grifton itself, and it was there that I completed school. During the high school time, at least, I was a member of the National Honor Society. I graduated with honors from there; and believe it or not, we had a superb English teacher named Ms. Exum who lived in this area, also. She knew French, but she didn't have her accent correct; however, she certainly knew grammar and various kinds of . relating to the French language. The result was that after I graduated from Grifton High School, I went to New York to go to school . major universities. Every place, they told me I had - I would have to finish high school. I didn't look but about 12 years old, you see, and they also told me I would have to take what in those days were called placement exams because people coming out of the rural south were not known to have very good undergraduate education, and so I took their placement exams. And to their astonishment - I didn't have to speak French, bear in mind, but I was placing in it as junior-level French in college, and they told me that I would have to take - just decide on a different major for English because I did perfectly fine on grammar and such as that. I had never known what a placement exam was, so I was extremely surprised to find that I had had the astonishing quality education that I received in Grifton.

Ruth Moskop:

That's wonderful. Which school did you attend first after you left high school here in Grifton?

Dixie Koldjeski:

One of my problems was that I . in school. My parents discovered I could read when I was maybe two and a half or three, but nobody really knows how nor where I learned, so that - in those days, you had to be five and a half before you could go to first grade.

Ruth Moskop:

Yes.

Dixie Koldjeski:

There was no kindergarten then, in my era. So I had to wait, and when I got there, as you can imagine, I was already a grade or two ahead of what other people were so that I sort of would be half in a grade here and going forward in part of a grade there. So I graduated from high school when I was just barely 15 years old. Now, what do you do in the late 30's with somebody - a young girl, 15 years old - what do you do? What's open to her? And so I stayed home, and my mother and grandmother tried their best to teach me what my grandmother used to call "the womanly arts," which consisted of sewing, cooking, and cleaning house. And I can recall quoting them the Law of Gravity about cleaning a house - that I saw no need because it was just going to get dirty again. When I was 16, I got a chance to be what would be today called an au pair, but I lived with a family when I was 16, and that's when I - my parents let me go to New York to visit my mother's brother. I don't know if you know or not, but he at - at that time, he was the head librarian of the whole library system in New York City. And they had a boat, and they were going to teach me how to swim because I was a notorious non-swimmer. So I went up to - he had a daughter my age, and I went up to New York. I got on the train in Wilson - Rocky Mount, North Carolina - the Silver Meteor - by myself and my little pasteboard suitcase. I went all the way to Grand Central Station.

Ruth Moskop:

How exciting!

Dixie Koldjeski:

I got there. My brother was at that time also - my oldest brother - older brother was in New York, and he was supposed to meet me at - I'm sorry, I said Grand Central; it was Pennsylvania. I got off at the Pennsylvania Station, and he was supposed to meet me, but I didn't see him and I was delighted because as we came out of all that maze of tunnels coming into Penn. Station, I kept thinking to myself, "My gosh, I can't believe I'm here. I can't believe this place." You see, at that time, the highest building I had ever seen was Hotel Kinston in Kinston.

Ruth Moskop:

Surely.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I thought that was comparable, say, to the highest building that anybody had ever built. But I had seen - the lady on the train said, "Well, you" - she says, "You ain't seen nothing yet. Wait 'til you see the Empire State Building." By the time that train stopped, I was determined I was not going to sleep that night until I saw the Empire State Building. Since my brother wasn't there, I asked a policeman if he would help to direct me to the correct door to find out how to walk to the Empire State Building, and he said, "Let me show you where to check your bag." I knew nothing about lockers where you checked bags. This was truly an absolute novel experience, and he could see in - he looked at me and I will never forget; he says, "Little girl, are you all right?" He says, "Are you lost? Is somebody supposed to be meeting you?" And I informed him that I was a graduate of Grifton High School in North Carolina and I had come to New York to spend six weeks for the summer with . So he said, "Well, do you know how to put your suitcase in a locker so you don't have to try to drag it?" He says, "You've got quite a walk in front of you." However, I had been used to walking miles because we had no car at home, and the idea of walking didn't really bother me that much. He took me over to this enormous row of lockers, and he says, "Now, you put a nickel" - or a dime; I don't remember - "in. You put it in and spin," but he says, "Now, you remember where it is and what your locker number is. In fact," he says, "Why don't we write it down for you?" He pulled something out of his pocket and did that, and I didn't have the dime, so he put the dime in the locker for me. And he says, "Now, come on. I'm going to take you to the proper entrance and show you exactly - I'm going to head you towards the Empire State Building; and if you just walk straight on, you can't miss it." He did that so graciously.

I got out there and for the first time, I began to glimpse the streets of New York. I took off in my brown and white saddle oxfords, my pigtails, my pinafore dress that my mother had made me, which I thought was the height of fashion, and up I went to find the Empire State Building. I had my head turned up, running into people, almost stepping off curbs, but determined I went. I got there, I went in the lobby, and the man told me how much it would cost to go to the top. And I opened up my little bag of money - I had no purse; I had a money bag - paid him and he pointed me to an elevator. Well, I don't know if you've ever, even to this day, ridden in the elevators at the Empire State Building, but they are so fast that you're at the top while the rest of you is still down at the bottom. This in itself was an experience, but I got up to where the balcony way up there is. And I got out, and I walked out, and I just was so awe-stricken. All I could do was walk around and look around and look out over this thing called New York City. And my husband and everybody in our family laughs about what happened to me up there. I recall I looked towards where the Trade Centers are - down towards that end of the island. I threw my hands up and I said, "Oh, my God. New York City, here I am, and I don't plan to leave if there's a way I can ever stay here. And I got in that elevator. I went - swoosh - back down - and my brother is frantic in Pennsylvania Station, and I walked back there. And by coincidence, he had met up with the policeman who had helped me, and he kept telling him, "I headed her towards the Empire State Building, and I'm sure she's going to be back here because her bag is here." And when I showed up, my brother was ready to just about kill me.

And so began my stay for the summer. I would like to say I never learned to swim and cannot swim to this day. I never learned to manipulate the sails on a boat and decided that was for the birds. But what I did discover was the New York City Public Library where my uncle was the head honcho, and I was determined - I was slated to go in September to Duke University. They had what was called a Diploma School of Nursing in that university. Well, my uncle, who was in New York, was a graduate of Duke; my mother's brothers were all graduates, and, you know, the thought just was appalling to me: "I don't want to go up there. All those people - all my relatives are up there, and I'm going to go up there and I'll have to work myself to death to kind of stay in tune with them. I would rather go to school in New York City. They've got a lot more stuff going on here," and my brother said, "I will help you to go to some colleges." So between he and my uncle, they arranged for me to go to the colleges I mentioned, to talk to them, and I would like to say to you I got accepted at every single one of them. The trouble was I didn't have enough money to go to - because every one of them turned out to be private schools.

Ruth Moskop:

Yes.

Dixie Koldjeski:

But that really was not the reason that - that really was not the reason that I didn't go. It was that my brother, who was quite a bit older than me, he said, "I just think it would be better if you would consider something . first off." And then it so happened that I was on Long Island at a . roast, and somebody said, "Well, you like - your choices are you can be a secretary, you can be a teacher, or you can be a nurse. I don't know what else you could do."

Ruth Moskop:

That was it!

Dixie Koldjeski:

And he said, "You know that the State of New York runs this series of nursing programs. Why don't you get your brother to take you over to investigate it, and you could stay on the island, but you will also be - have to go into New York City for some of your college - for the college work." And that's what I did. Those schools were located in the big hospitals run by the State of New York for the mentally ill. So that's where I first went. I wasn't old enough to be accepted, and the lady who ran the school that I went - my brother took me to get information - she said to me, "Well, you have to be 18, and you are not near 18." And I said, "What do I have to do? There must be exceptions." That was one thing I had learned as a member of a big family; there's always exceptions to everything. She said, "Well, you'd have to get permission from what is called the Board of Regents in Albany." They were the head structure for this type of education in New York in those days. They were very powerful. So she gave me the address, and I wrote them and told them that I was now ready to go into the School of Nursing but unfortunately I just wasn't old enough and I'd like an exemption or an exception made.

I had a lovely summer on Long Island, and Labor Day was coming and I had not heard from any board. I was kind of getting antsy because Duke University had not moved from Durham; and over Labor Day, believe it or not, I got my first telegram. My brother brought it to me, and they gave me an exemption to go into a school, even though I was still months and months younger than what they usually admitted.

Ruth Moskop:

Wonderful. Now, you said - you must have been 15 and a half?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yeah. By the time the summer was over, I was 16.

Ruth Moskop:

I see.

Dixie Koldjeski:

The problem was the school was three years - it took three years, you know. And when it was time to take the State Boards, I still wasn't old enough to take the State Boards.

Ruth Moskop:

Oh, my goodness.

Dixie Koldjeski:

So we went, again, the exemption route. So part of my first work in Nursing with the mentally ill occurred at King's Park State Hospital out on the island. The State of New York at that time had massive institutions for their mentally ill, and I also got my additional work at Adelphi College; it was a college then. We had to go to Adelphi College, and I was at Queen's General Hospital in Jamaica and . which was a communicable disease hospital on Ellis Island and where communicable diseases were brought. That was my first entrance into the world of Nursing.

Ruth Moskop:

Tell me - you graduated from where again? I think the recorder stopped.

Dixie Koldjeski:

King's Park State Hospital for Nursing, but my degree - first degree was from Adelphi College. It was shortly changed to Adelphi University.

Ruth Moskop:

And is that on the island?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, I don't know. It's in . City, New York, but I guess it is still considered on . into the city, yeah.

Ruth Moskop:

So that was your first degree, and you had all sorts of experiences leading up to that degree with Mental Health Nursing.

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, part of my training was in one of the hospitals which was out at King's Park - King's Park State Hospital. They had something like 12,000 patients out there.

Ruth Moskop:

My goodness. It was huge!

Dixie Koldjeski:

But it wasn't - there were two more even larger on the island that - you see, most of the patients came from New York City and were sent to the island; hence, the large groups.

Ruth Moskop:

It motivated you to go on, then, to study more Nursing.

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, when you see my vitae, you'll find that first I finished my diploma and then got permission to take my State Boards. I passed those, and we were then getting into World War II, and college degrees and what have you were not the highest order in this country. With nurses, it was work for . I tried to join the Army Cadet Nurse Corps. You know, they had a cadet - and I thought - they considered - I was only 4'11" tall and I only weighed about 95 pounds, and they considered me - I resented the word, very much, "puny." Hadn't been sick a day in my life, but I was puny. So I stayed in the civilian work force and worked in New York City hospitals during that time. So it wasn't until after the war that I was able to complete my first baccalaureate - my baccalaureate degree. You see, the diploma school - you can get a license to practice Nursing, but it is not an academic degree.

Ruth Moskop:

I see.

Dixie Koldjeski:

So I didn't get that until after the war ended.

Ruth Moskop:

Do you remember what year that was when you did get your baccalaureate degree?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Oh, it was quite a few years before I got back to it because I got married and I had a couple of children.

Ruth Moskop:

I see.

Dixie Koldjeski:

Some time in the 50's. I graduated from the diploma school in '45, I believe - '44 or '45 - some time about then. And then, you know, the war in the Pacific still was very much on, so I didn't get back to finishing up for my college - first college degree until some time in the 50's. I don't know; it's on my vitae.

Ruth Moskop:

Which college did you -

Dixie Koldjeski:

And I went back to Adelphi. Well, I went to Adelphi; that's where I was going to get my degree, but in the meantime, my husband had returned from college. I met him in college. He was over at NYU, and we were both in - the universities at that time would - shall I say, they had classes. They'd cooperate, and the university would have a class where students from other places would come. He sat back of me in an Anatomy & Physiology class because we were lined up by alphabetical last name, and my name was Dixie Dawson - D. His was K. He sat back of me. And of course, I was so enthralled with New York City, I was practically failing the course. And we had a professor who was just intrigued, I think, with my accent, so he would call on me, and I never knew the answer. This voice from back of me would whisper, usually wrong I might say, and one day in the hall, I informed him that if he was going to tell me answers, for God's sake, please make sure they were correct. I was getting in trouble with him. So anyway, he had - after he got home out of the Army, he finished up his degree and he got a job in Indianapolis, so he . at a psychiatric research institute related to Indiana University in Indianapolis at the medical center, so that I left Adelphi still short my degree. But Indiana University took one look and said, "We're going to talk to them and if you can do X, Y, Z here, we'll go ahead and give you your degree," and that was - so that I ended up officially with a degree from I.U. And I only waited a year or two, I think, when I went ahead and got a Master's and worked several years at the Medical Center at Indiana University. Then came the whole upheaval about the status of mental health in this country prior to Jimmy Carter's presidency, and - no, I think I'm wrong. Prior - let's see - Kennedy, I know, because I helped to work on the groups that we put together - the Mental Health Act in 1962 or something.

Ruth Moskop:

The upheaval: Could you tell us a little bit more about that?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, the states have characteristically and constitutionally been responsible for the care and treatment of the mentally ill patients in those hospitals. We had expos� after expos� of the appalling situations. They got no treatment. I mean, they - that is, psychiatric treatment - and their care was just left to the ignorant people who knew absolutely nothing about mental illness - treated them, in many cases, extremely brutally. But the whole idea was if you can't cure them, then you tie them up and restrain them because you don't want them to hurt anybody, and you don't want . hurt people out there. That was the status of the mentally ill in the country. There were some states with a little more humane approaches, but the states actually would not fund the money that was needed to . That was a big part of it, but another big part of it was that in 1950, we were still very much ignorant about what else to do with the mentally ill. We did not have psychotropic drugs in those days, and we did not have leading psychiatrists leading the way, and it may be of interest to you from the mental health perspective, during World War II, as you know, the rate of young men who - during World War I, it was called they were shell shocked. During World War II, they became, I guess, stressed but to the point that they were nonfunctional on the battle lines. During World War II, as you know, the United States Public Health Corps asked for help from the most imminent psychiatric group in the country, which were the Menninger brothers out in Topeka, Kansas - three of them. And they went in the Army, and I think they thought that Psychiatry was practiced from a couch a la Freud, but they were truly shocked at what they saw, along with others. But they were the prime leaders.

Ruth Moskop:

Menninger?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Menninger.

Ruth Moskop:

How do we spell that?

Dixie Koldjeski:

M-e-n-n-i-n-g-e-r. Menninger's has been in Topeka, Kansas - this is a multi-generation of people who worked with the mentally ill. One of the Menningers just saw amazing things that did not fit with sort of the psychodynamic theories of the time related to mental illness. He saw young men who were absolute basket cases, and he saw that if you sat them down and counseled them - gave them some rest away from the guns and fear of being shot that they made amazing recoveries - some, hours and some, weeks. They were back out functioning again as soldiers. Yet, by the symptoms they illustrated, or that they were showing, these were seriously mentally ill young men. He came back from the U.S. Army, and he began almost a crusade, is the way I'd almost describe it, to say that it was - that there had to be other ways of treating the mentally ill besides . or some version of it.

Meantime, in a little lab in Switzerland, a group of researchers - a pharmacological lab - a group of researchers were playing around with trying to isolate certain kinds of compounds, and one of the ones in the test tube - somebody accidentally - they - it was ingested accidentally, and to the astonishment of the colleagues in the lab, he became very quiet and very - how shall we say - he was very pleasant, mellow, and all this, and they said, "What was that you just said you mistakenly took?" Well, it turned out that way out in India, since time immemorial, the people used an herbal remedy from what was called rauwolfia - the rauwolfia plant.

Ruth Moskop:

Rauwolfia?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Uh-huh. I don't know if I can - r-a-u-w-o-l-f-i-a - rauwolfia plant. And the compound in this lab was very close to a synthetic version of that. Well, this immediately began to stimulate just a tremendous amount of . "Wonder if this would really work on people who had mental problems?" Well, they set out to ... and that was the discovery of what was the forerunner of the synthesized psychotropic drugs, like Thorazine, for example, except that was not the first one. It was - I've forgotten the name of the first one. Thorazine was probably a second or third generation from the labs - much more refined but still very rough.

I might just say as an object in passing, I worked on the first clinical trial with Thorazine with Nathan Klein and all the group in New York City, and I'll just tell you some interesting facts about it. When we first got it, it was in a liquid form, but it was so irritating, they finally put it in . form and did what is called enteric - they put a coating on it - that it only dissolved once it was through the stomach. But the tablets that we got for the clinical trial were not that way, and we also - they were only - they were not in gradations of doses, and we had to cut tablets. Well, pretty soon, we had dermatitis on our fingers, between our fingers, our faces. We were a mess. And we started to have to wear gloves and a mask. See, the dust from trying to cut the tablets was what was doing a job, really, on our skin. That's what was happening to the nurses, but let me tell you what was happening out there to the patients. We had at that time - schizophrenia is really a - and the manifestations that schizophrenia displayed in those days - it was a terrible disease - hallucinations, delusions, violent behavior - were just, you know, common. Imagine being on a ward with 49 of those. Well, we - this was a double-blind study, and no one - the - we had to cut the Thorazine tablets, but we also had the placebos we had to treat the same way because no one knew who was getting what. It took exactly 10 days of handing out the pills before the nurses knew the patients that were on the real stuff.

Ruth Moskop:

After 10 days, the nurses knew?

Dixie Koldjeski:

The patients knew. It was almost a miracle to us to see these patients who could not - absolutely could not control the behavior I described. They could talk with you. Their relatives came and saw what was happening, and they demanded to know what were . Well, we didn't know who, you know, until we saw what a difference it was making. And as we kept on giving the drugs, the patients were identified who were getting the real McCoy. And lo and behold, we soon found there was quite a commerce going on. They would put the pill in their cheek and sell it - after we were out of the way, they would sell it to somebody who wasn't getting it, and the families were paying the one who was originally getting it - for the pill.

Ruth Moskop:

Wow!

Dixie Koldjeski:

This resulted in the fact - when we became aware that this was happening, it resulted in the fact that we had to equip ourselves with flashlights and tongue depressors, and after the swallowing took place, we had to open - ask them to open their mouths and with a tongue depressor look under their tongue, look in their cheeks with the flashlight, and make sure they swallowed those pills. And so it was with the first trial of Thorazine. It was a stunning revelation that something - up to that time, the whole world and the United States believed that mental illness was a disease of the mind. The fact that there was some kind of connection to the body was just an anathema. It just didn't fit Siggy Freud's theory. Well, that was a very interesting experience I had on that clinical trial. It was also the first time that I realized, "Hey, this research stuff is interesting. This research is really interesting, and when I get back in college, I'm going to learn more about how this stuff is done." And by golly, when I got back to finish up - start to finish up some degrees, I sure got myself involved in research.

Ruth Moskop:

Tell me again - when was the study?

Dixie Koldjeski:

The study would have been around - it was in the late 40's, I'm sure. I'd have to go back and -

Ruth Moskop:

Late 40's. And where were you?

Dixie Koldjeski:

I was at King's Park State Hospital. That's where one arm of the - they had arms, you know. They had a huge pile of patients in there and at all the state hospitals; it wasn't just us. Gosh, I can't even remember now how many thousands of patients were involved, but it certainly opened the door in two ways to a whole new era. First, it was true that no one really knew how or why Thorazine worked.

Ruth Moskop:

Let me turn the tape over, Dr. Koldjeski; excuse me. What were the two ways?

Dixie Koldjeski:

The first was that at that time, I don't think anyone - and by that, I'm talking about the researchers and Psychiatry and the people working in this whole area. They did not know why Thorazine worked, but the fact that it had the impact that it did, it was obvious that there was more to mental illness than just the aberrations of the mind involved. The second thing was we also began to see then the theoretical speculations and formulations that mental illness began to take . and started to move away from psychodynamic theory; and by that, I'm meaning basic Freudian theory with some modifications. We saw a move away from that into something more like what Harry Stack Sullivan was pioneering at the time down in Maryland - his personal theory, and that there would be different kinds of therapies that might be very useful to rehabilitate mentally . analysis. So it was an exciting time. The aftermath of that was - back in the States was the developing, brewing scandal about the plight of the mentally ill, and I do know that the prior - it was during Kennedy's administration that the Community Mental Health Centers Act was passed, and there had been a commission prior to that that tried to pull together key aspects, and that's in your library. In fact, I think I put a copy of it in some of the stuff I had - some of the key . I think it was enacted in 1964 or '65. This brought about the third piece of some of the consequences of the experiences that were slowly culminating and accumulating that the mentally ill - that really just how little we knew about mental illness. When the Community Mental Health Centers Act was enacted, it really for the first time said a lot of these so-called mentally ill can and must be handled in community services and in ways that does not put them in these gigantic state hospitals forever and just leave them - warehouse them. So it was a - it was a very exciting 10 years.

Ruth Moskop:

They got the centers going?

Dixie Koldjeski:

The law specified it would be a tripartite endeavor. The federal government would kick in money, the states would kick in a third - the feds a third, and the states a third, and the locals a third. And that was the arrangement of the original funding. There had been in the Institutes of Health, I think, a little area department or something tucked somewhere that was concerned about mental illness because the Institutes of Health is supposed to be about all illnesses in their mandate. But the National Institute of Mental Health was established. That gave mental illness a tremendous disability budget that was apart from the rest of the campus - the Institutes campus up in Bethesda - and also brought together some - you know, the very best people in the country were attracted to come there to try to move this revolution, really, along. The trouble was who in the world did we have in this country who was trained to work with the mentally ill in this way, and the answer was relatively few, so that part of the National Institute of Mental Health mandate was training money to invite institutions to come in with their idea of innovative programs to train mental health professions in new ways and all of caring for the mentally ill. And of course, they also had - an arm of that was for research. My first job in mental health in Bethesda at the Institutes of Health was working in a training - in the training programs. I was head of the Psychiatric Nursing Training Branch, and I recall one year I had 29 million dollars to spend, but it was the funniest thing. The day I got there, I said, "Let me see the mandate," and I read that. The mandate said that we should consider as our territory, so to speak, the United States and its territories.

Ruth Moskop:

Gracious!

Dixie Koldjeski:

I promptly decided every one of them needed to be visited by me.

Ruth Moskop:

What was your position?

Dixie Koldjeski:

I was Chief of the Training Branch for Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing.

Ruth Moskop:

At the Institute for -

Dixie Koldjeski:

At the National Institute of Mental Health, yes.

Ruth Moskop:

So at the National Institute of Mental Health, you were Chief of the -

Dixie Koldjeski:

Psychiatric Nursing Training Branch, yes.

Ruth Moskop:

Thank you.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I didn't get to all the territories, but let me just say I got to a fair number of places, and it really gave me almost a global perspective of what was happening to the mentally ill in various countries, particularly in our own country and our own territories and so on and so forth. I did not envision a career in the federal government because we knew in the National Institutes of Mental Health you work with the - you are in the executive branch, and so I was at the National Institutes of Mental Health in that position when Jimmy Carter - I was there when he was elected, but I'd been there before. Who was our president before Jimmy Carter? Darn if I - was it Ford? I guess he took over. No, because Nixon - I don't know. Who got elected in 1970?

Ruth Moskop:

I don't know.

Dixie Koldjeski:

It was Nixon. All I know is it was somebody who - it was - I guess it was Reagan. All I know was the person who was elected after Jimmy Carter - because Rosalynn was a great - she really carried the ball when he was in office, and that was when they had another commission, the one I worked on . we did a lot of the staff work for that one. But he lost the election, and the next president to come in - in his state, I remember, he had stripped the mental health institutions back to nothing. "If they could do better, they would." And I said, "Oh, my God . executive branch, and you can't stomach the politics of the president. You better get out." And that's exactly what I did.

Ruth Moskop:

What did you do then?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, that was - it must have been - that must have been when I came here to start the Master's program because -

Ruth Moskop:

1978 or '9?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Leo Jenkins and the dean were calling me and saying that . and so on and so forth, and I came down for an interview, and ultimately I decided that looked far more interesting than working in an executive branch of the government where the president didn't have very much -

Ruth Moskop:

Support?

Dixie Koldjeski:

- support or anything else for the mentally ill. While I was there, I had a chance to serve on the Rural Mental Health Clinic Commission. Also, the mandate in the office was that I make sure that as far as we could that we helped institutions start programs to train mental health professionals; and in my case, it was nurses. So I think I in a year would, you know, visit 60 to 75 programs - Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam - well, Guam didn't have one. However, since I was in Hawaii, I thought Guam needed to be cased because they had a request. All this was really bona fide because they watched the money up there. They had auditors on your neck. But it was a time when people saw the federal government really brimming with money to start new programs, and many times they didn't have the resources to do it and would not have the resources in my lifetime to do it. Of course, there were grants, but you would get there and find that they were practically in a tent or something, or what have you, and that you would just have to as tactfully as possible say, "Here's what it takes to start a program," and stuff like that.

Ruth Moskop:

It kept you busy.

Dixie Koldjeski:

It did; it did. But ever, ever interesting. And I met some of the most . in the country. After I left the feds, when I was at ECU, I - the National - you know, there's a National Health Service Corps that can be called up in an emergency - sort of a shadow group out there, but they can call you in and send you wherever, and I did a lot of work when I was at ECU. We were trying to get a Master's Program. I did a lot of work for the National Health Service Corps, and I would lead teams for them, and I went to a number of . no longer to set grants up but to evaluate many grants that were there, and I could see how nearly always, there was this research of some kind that I was involved in, either in trying to establish some kind of way to evaluate or else reading and interpreting what they were handing me. But always was this love of what - you can just discover so much if you will do your research and learn how to interpret all of that. One of the consequences of this love of research was -

Ruth Moskop:

Always focused on mental health care?

Dixie Koldjeski:

In research.

Ruth Moskop:

In research.

Dixie Koldjeski:

And in mental health, it was more specific; it was working with families. I did - when I was a practicing therapist, I did do some private practice stuff, you know, with individuals. My love has always been with families, probably because I come out of a large family and always had enjoyed the give and take of it and the fact that our family took in stray relatives like dogs who would come sometimes to spend the summer or to stay with us several months. Nobody thought anything about it. They just came and said they'd like a visit. But my memories of childhood were that we didn't - we were not rich; we had enough that we always could do it. And not until many, many years later did I realize that probably a great part of my life was shaped by something I had no knowledge - because my mother was a daughter, all of her brothers were sent to Duke, but girls did not go to college; but she loved reading and knowledge. My father was one of the first students that enrolled in Barton College - what is now Barton College - the old Atlantic Christian College. He and his cousin decided that's where they wanted to do. Now, I don't know, and I plan to find out - I don't know whether he ever graduated, but I do know that's where he at least went. But they had nine children; my parents had nine children, and we would come home from school and darned if we - we thought we left school behind, but as soon as supper was over and those dishes were washed and dried and the kitchen was swept, we were marched into the living room, and there my mother and father conducted another two or three hours of school. My father spoke beautiful English and language. My mother would improvise flashcards by cutting up boxes. We had spelling bees; we had contests. But by God, we learned English. We learned at home, and I think it was this great love of literature and history and all of that - somehow or another was sinking in our souls without our realizing it so that when I went into Mental Health, family was what I gravitated to, and I had a chance to study with what were considered some of the best family clinicians in the country, including a week of spending time - do you know who Bruno Bettelheim was?

Ruth Moskop:

The name is familiar.

Dixie Koldjeski:

With autistic children? He worked up at the Sonia Shankman School at the University of Chicago, and his work has later been questioned about some of his practices, but at the time, he was a . There was Greg Bateson and Virginia Satir - Nathan Ackerman in New York. These were the greats . had shots at all of them and had them as instructors.

Ruth Moskop:

That's marvelous.

Dixie Koldjeski:

So that when I decided after the Community Mental Health Centers Act passed that if that was calling for the whole new way of caring for the mentally ill in the world, did it mean in terms of somebody who was going to get a doctorate. By then, I was very much aware that I did not want to spend my life just working with this family and that; I wanted to get positioned where I would be a crackerjack researcher because one of the things all those people taught me was there very little research out there about families. So when I went to apply to get a doctorate, I just could not find any place. It was just more of the stuff that I had had in my Master's, and it was not - it was very clinically oriented, but it didn't have the research component I was interested in. And finally, since my husband had - it was his turn to choose where we were going to live and work, so he got the job in Indianapolis; and while I worked on the Indianapolis campus, I went one day down to the Bloomington campus, which is the flagship. And I had read they had what was called a Community Mental Health Program in Sociology. Well, I knew by then a lot of the theory was coming out of Sociology for mental health, so I thought, "I'll go down and see what all that's about," and I did and became extremely interested in what they were offering. The trouble was - I don't know if I should tell you this, but the trouble was that department didn't think women - they didn't think the Civil Rights Act applied to them for women, I don't think. And they wanted to know how many more babies was I going to have and so on and so forth. And although I had something like in a Master's Degree, about 65 or 70 - because I kept taking courses. I would place out - in those days, you placed out, but they didn't give you the credit. You had to take a substitute or you had to take other stuff. Hence, I kept going further - all over the place - things that interested me. But they considered all of that nothing, and they offered - they would not admit me and said I could come down and take 20 credits to see if I could even do the work and then they might . before I got a degree. And so, I kind of got nasty. Here I am up on the Indianapolis campus working, and the Bloomington campus is refusing to admit me into one of their doctoral programs. And they were very separate campuses, but there was -

Ruth Moskop:

Still an umbrella?

Dixie Koldjeski:

So I said, "Well, I'll tell you what I'll do; I'll sue you," and got a lawyer, and we - he put together a suit. They were failing to comply with the Civil Rights Act. Well, I think you know that when it hit the higher-ups who were investigating and so on and so forth, to put it bluntly, there was Holy Hell to pay. And to make a long story short, believe me, I got admitted. I thought, "Yeah, I'm here, but my life won't be worth living because this bunch of men is going to kill me. I don't have a - I don't have an undergraduate major in Sociology; I certainly don't have a Master's in Sociology. They are going to kill me. I'm not sure that even I can do the work." I went to the first class, and I didn't even - I didn't know the jargon. I didn't know the people. I didn't know - I remember racing to the bookstore and I bought 75 dollars' worth of books. I was going to become an instant fill-in, you know; and in those days, 75 dollars bought a lot of books. And I went home, and my husband came out and helped me unload, and he says, "What in the world is all this? This is not from this course." I says, "I didn't know what they were talking about." They assigned me to a - you know, my adviser - he must have been 10 or 12 years younger than me, and he told me right off the bat what he thought about me. And I told him that he could think about me any way he wanted, but if he didn't want to advise me, please tell me so because I certainly did not want to associate with anybody who felt that way, and we had quite a conversation after that. And I recall that I went out his door, which had a glass at the top, and I can't recall to this day whether I helped it slam or it slammed. All I know was the glass fell out of the door and broke.

Ruth Moskop:

Oh, gracious.

Dixie Koldjeski:

And I told him I was sorry. So we had to clean the glass up; and by the time we got the glass cleaned up, he said, "May I call you Dixie," and I said, "Yes." He says, "Come back in here. I think we need to start over." It turned out to be one of the most marvelous adviser-student relationships anybody could have. And he says, "Now, tell me straight out what are you going to need to get up to speed this first year in these courses?" I said - and I told him - I said, "I've bought all these books." He said, "Well, you know, we have a fund that - what do you think is going to give you the biggest problem?" I said, "I'm very good in languages. I'm very good in English. I can write very well. Math will be - advanced statistics is where I'm going to run into trouble." He says, "We have a fund to help students be tutored, and I'm going to get you a tutor." And by gosh, he did. I had a tutor paid for by - I don't know where the money came from, but they paid for it. And I did extremely well, of course with the tutor, in the Math.

Ruth Moskop:

Was that your first self-directed research?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, I had done research even before then, but it was - when I look back on it, I realized it was quite elementary. We had to do just theses and small projects to show we understood how to apply principles, but most of those were more - had a secondary goal of, "Can you illustrate the principles rather than for the findings themselves." But I remember being in a seminar one day, and this student said, "I am going to present my new theory on" something; I've forgotten what it was. And I said, "This person's talking about theory development? I thought only geniuses did theory development." Little did I know that theory development and research were like ham and eggs. It turned out that on the faculty was Alfred Lindesmith, who's the great social psychologist who is a graduate of the University of Chicago who wrote textbooks used by students right here at ECU for years and years. He and Ira Glazier, who wrote, "Grounded Theory" - the whole books on grounded theory who's at the University of California - they were partners. And Dr. Lindesmith came very shortly after my adviser and I got straightened out, and he said, "I understand you like Cokes and I've got two. Would you like to let's go down outside and sit on a bench? I want to talk to you." I thought he was going to tell me it would be advisable to get out of Sociology. It didn't turn out that way at all. He said, "I want you to know that I already admire somebody who has told a few of the young men around here where to go," which I had done - not very wisely, but I did do it. And he said, "I just would like for you to know that if they really start giving you a hard time academically, I want you to let me know because there are a group of older faculty here - no women have to come in here - and we are not going to permit that to happen to you." He turned out to be a marvelous friend. He was on my - he's on - if you read my dissertation, you'll see he's on it. Sheldon Striker, also from the University of Chicago, one of the top persons at the time in interaction theory - he was on my dissertation. He also had become Chair, and he was a much different Chair than the guy who gave me such a hard time. And these people all were authors of the books I was studying. The Chair of my dissertation committee was a guy out of Yale who was tops in Criminology Behavior . and I have a minor in Clinical Psychology. And over there, I met a gentleman who said he would like to be the major adviser on my minor . social ecologist at Stanford University. He opened doors to the absolute top elite of people in the country for me. So when dissertation time came, my adviser said, "What are you going to do?" . when I told him, and he just says, "Oh, my God."

Ruth Moskop:

Whose theory -

Dixie Koldjeski:

At the time, there was a guy from - I don't know - from the west coast. His name was Thomas Scheff - S-c-h-e-f-f - and he had a theory of being mentally ill that set the country on its ear. But it was still a theory, and he said, "Have you thought about how are you going to test it?" I said, "Well, the first thing I know is there's no instruments out there, so the first thing you're going to have to help me do is I'm going to have to spend an entire year just developing instruments and testing those," and I did. Now, in the process, every - all these top faculty became so involved in this that they got help for me from Harvard. I had help from Harvard. You know, the guy that writes - wrote "The Moral" - those moral stories that you're supposed to be able to measure morality; he later committed suicide because . he helped me on my - all of this, incidentally, was gratis. They all did it, and they all knew what I was doing. And finally, at last, I had the instruments. Then I had to find somebody to test my hypothesis, and I said, "Oh, I know exactly who one of my subject groups needs to be, and that's the engineers at Purdue University. I'm sure they know so little about mental illness that they would - I would like to know how they would look at any kind of aberrant behavior." And through a network of, "He knows a Philosophy professor; he knows," they opened up a whole class over at Purdue for me to go - and the engineers and . they were one of my groups on which to test the theory. Meanwhile, back out in Santa Barbara, California, where Tom Scheff was, he would call and say, "How ya coming? How ya coming?" He's kind of flaky himself. And he said, "I just can't believe what you're doing to test this theory." Of course, he was just absolutely delighted when he - the Chair sent him an abstract and told him what I had found. People - they talk about their doctorate being . I truly - despite the rocky entr�e into the program, I really and truly had one of the most enlightening periods of my entire time. But one of the things they made of me was to be a damned good researcher. I'm not talking about a researcher that just runs out and collects a little data and reports their findings; I'm saying their whole philosophy - they - you know, they used - I just used this quote this morning or - earlier when I was up writing a letter, and I used this quote in the letter, which brings it very fresh to mind: It was Palmer Corray who said, "A bunch of facts is to science what a collection of stones is to a house." If you don't do the theory and somehow make a contribution, all you've still got is a bunch of facts. I called them factoids at the CNN. And so, I wandered into family research. I have a book on Community Mental Health, trying to bring in some of the social aspects of mental illness, and what I've been working on for the last year is I had a funded project to investigate the impact of a diagnosis of ovarian cancer on selected . I came about this because there was - the head of the Gynecological/Oncology Clinic over at the Brody Medical School was a doctor named McGee or McFee - I've forgotten which. He called me one day and he said, "Dr. Koldjeski, I hear you are the family guru around here." He said, "We really don't know very much about how to help these families when they have a member diagnosed and starting to be treated with ovarian cancer. I would like to ask if you could possibly help us. [The cassette reaches the end at this point].

Ruth Moskop:

Excuse me. Dr. Koldjeski, you were telling us about the beginnings of your project here at ECU with ovarian cancer patients.

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yes. I went over and talked to Dr. McGee, and he said that they would be very willing to help me try to recruit whatever I needed - families or individuals or what have you - and if we could find - if I could establish some kind of research that might provide a little bit more specific kinds of information about what they could do to help families, because by the time he called me, the treatment of women on the extremely toxic regimes - they would come in to the hospital over there for their - for the actual administration, but the care of these people was going on in families, as has been the whole shift of healthcare. And as a result of that, I developed a grant, and I was able to get funding from the Oncology Nursing Foundation. I had a team, and we virtually lived in those - with 18 of those families for a full year, and we got data this high. We have qualitative data from the open-ended interviews when they would be asked to . live the experiences the family and the sick woman were going through, and then the targeted variables of functioning that we had, like coping, psychosocial responses to the illness - what were their needs - I don't know; we had four or five of those. They would even sit at the kitchen table. The families would convene and they would - it's not - the research does not consist of - this is virtually unique in the country. It does not consist of adding together what family A, B, C, and D said. These people got together five times a year and went over those questionnaires, and then they had their open-ended sessions of talking about their experience, and we had someone that was taking field notes on those for a full year. We never had a family leave us, and we had over 50 family members that were involved in this project.

Now, I have been asked by several of the physicians over at Brody how did we do it. How did we keep these people - you know, most of the time, it's one shot in and out. Give them a questionnaire. How did we get in there and get these people to stay with us for a full year? I think the secret on that answer was on orientation, the team came up with an approach that we would just make sure they understand we did not go into the family as clinicians, that we were not there to provide care but that if something happened - that emergencies arose - with their permission, we would certainly call 911 or call their physician, whoever was appropriate; but our real goal was to try to get information from them on research on what was happening about - with this woman in the family who was ill and what impact . that this would be something that nobody in the country has ever done this way, and we asked them to be participants in this project. I said, "You must tell them that we have no money," because our grant wouldn't give us the money or a little honorarium - we had no honoraria - and would they consider to help women who in the future will need to - we just need to know more of how to prevent this and how to treat it and how to help the families. And every single one of them signed consents, and they stuck by this thing. The result is that I was getting too old for ECU, so I have been working on getting the publications out. That's why I'm writing so much. And we already have had - I'm of the type that if you're going to spend your time and energy on research, don't go for pitty-poo magazines; go for the top ones. So the first thing has already been published about the - there's a myth out there that ovarian cancer is stealthy - that it has no symptoms; that is not true. That article has already been published; and just this past week, a researcher from Seattle, Washington, at the University of Washington in Seattle has got an article in JAMA that - she doesn't know it yet, but I'm going to call her. She was looking at them, but she didn't do it in the way - our methodology is different, but we're coming up with the same thing. So we are probably going to see some major changes.

The second article - one of the big problems in ovarian cancer is because people believe it has no early symptoms and if they have symptoms, they are not reproductive system symptoms; they are gastrointestinal system symptoms. So they misinterpret it. And what we found was 90-something percent of all the women who showed up with these symptoms were misdiagnosed. So that article has already been accepted by the leading journal called "Cancer Nursing." And boy, were we proud. I got the - it went out for its peer review, and the review came back two lines: "We have never read an article that is so well written. The only thing we would like to see is an illustration. Is it possible that the authors could provide us with an illustration of how," what they call their "reduction strategy worked," and we've done that, and I got an e-mail two days ago from the editor. The article used what is called abductive theory to see where were these delays occurring and why, and I have got it all mapped out. And the name of the article is going to be, "Unraveling the Delay Problem in Ovarian Cancer." And I have two magazines who want that - two of the top. One is an international journal that goes to 30 countries.

Ruth Moskop:

Fabulous.

Dixie Koldjeski:

So the co-investigator will be over tonight at 7:00. I've got to get - you know, everybody has to sign off permission - all that integrity and stuff, which I don't object to, but it takes time. Now, she does that since she's up here. As soon as I finish that, I have one more article that we will get published in the top journal of "Family Nursing," and then I want to go back to one of my side loves and that is to write some stuff I like to write about that's not professional. So I thought I'd write something about our family and some of the "One hears." I'm not always sure it's in a positive tone. One hears about those of us who were "depression" - that we - what do they call us? We were depression something or another's - not the Tom/Joe type of depressionists but that we somehow ended up with a world view that was penurious and all of that. That's not really true, but it's become quite - I want to write some stories - probably a couple of stories about how families endure. I don't know yet, but I've got my list of depression -

Ruth Moskop:

Topics?

Dixie Koldjeski:

No. I've got the actual books that were considered some of the - I've already done some searching on that. That's why I've got to go to the library here. I want - I thought they might be sitting over there in the Pitt County Public Library.

Ruth Moskop:

Are these books on clinical depression?

Dixie Koldjeski:

No, no.

Ruth Moskop:

Or growing up during the historical depression?

Dixie Koldjeski:

It's social depression.

Ruth Moskop:

Social depression?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yes.

Ruth Moskop:

Economic depression. Is that what you mean?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, it certainly was economic, but it was broader than that, I think. It certainly had an impact. Well, it had an impact on the Okies. I mean, we know that from the famous - but that experience is not the experience that our family had, so - anyway, that in a capsule is running, I guess, to close out my career, which has always been a great love for English, literature, and history combined; and professionally, when I discovered something called research, the idea of discovering knowledge and working on theory was just almost beyond anything I could encompass.

Ruth Moskop:

Thank you, Dr. Koldjeski. It's been a real pleasure to listen to you and have this little conversation today.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I didn't tell you about being in jail, but one day I will.

Ruth Moskop:

All right. I'll look forward to that.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I'm also quite a person who believes in one treatum.

Ruth Moskop:

That's important.

Dixie Koldjeski:

And I managed to get myself - were you - do you remember when Betty Friedan declared Woman's Liberation Day the first time?

Ruth Moskop:

No.

Dixie Koldjeski:

My darling husband has to, you know, arrange for the lawyer and get his wife out of jail.

Ruth Moskop:

Where were you in jail?

Dixie Koldjeski:

In Indianapolis.

Ruth Moskop:

In Indianapolis?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yes. We asked for a parade permit on that day, and the great fathers-to-be said we were political because we wanted to liberate women from various social inequities, and they refused to give it to us. But Betty Friedan declared that women should walk out of the kitchen and band together to show that they had some rights other than to clean house and cook. Now, that message could not have fallen on a more fertile set of ears than mine, and I called somebody I saw in the paper and she said they were going to not have a formal march but we were - Indianapolis is laid out like L'Enfant - like Washington, DC; it has a center circle and a statue with Miss Indiana sitting up on the top - and that we were just going to go down and informally march with our placards and so on and so forth around the circle. But the city fathers decreed that that was a march, and they would not give us a permit because we were political. Now, it so happened that they had given permits to Robert Kennedy, who marched and had marches all over the place around the circle when he was politicking for president. They gave permits to the Ku Klux Klan of great fame. They gave permits to anybody who asked for them, but they wouldn't give us one. And the lady who was heading this said, "Well, we're going anyway." I said, "I will be there." And we lived next door to a lawyer whose office was right on the circle. He came over that evening and informed Ted that the rumor was that if we did do that that they were going to be waiting for us and would pick us all up and put us in jail, and he just wanted us to know what I was getting myself into. And I said, "All right. Now, if I get picked up, will you represent me? Will you come get me out of jail?" So believe it or not, I followed his advice; I had dimes taped inside of my bra because that's what it cost, and they allowed you one phone call.

Ruth Moskop:

When did this happen?

Dixie Koldjeski:

It was August something - on the very first - I think it was some time around '68 or '69. It was Betty Friedan's - the first day of what she called Liberation Day. I had dimes taped in here. I had his phone numbers taped over here. Of course, I knew Ted's phone number; he was at the Psychiatric Institute that day. I had two children, one in middle school and one in high school. Off I went, and I remember I had on a red straw hat, and it was hot as blazes in Indianapolis. And we started our roam, you know, just walking. And for the first time - I had read about black moriahs, but I tell you they are black, and they had little ledges to sit on inside. We were confronted with policeman like I hadn't seen ever, except on TV, swinging clubs trying to hit our shoulders and arms and fractured the shoulder of one young woman. These women had nursing babies and children in strollers, and this was what greeted us as we tried to walk around that circle. And they herded us - since they couldn't get us all into those black vans, they marched us and pushed us over to the city/county building two blocks away where the county jail was. They put us in the lobby, and they called the judges down to start to process us. Well, it was the funniest thing going. The judge - he came down and he took one look, and he just about died. There must have been 75 or 80 of us down there. They had nowhere to put us, and he refused to process us because he wasn't sure we had done anything illegal; and, of course, that created a stir with the officers of the law. But meantime, we're sitting on the floor in the lobby of that huge, monstrous building waiting to see what our fate was. Meanwhile, the Dean of the School of Nursing with her TV on saw what had happened to us. Ted's over at the Psychiatric Institute; he knew what had happened to us. My children are in school and asked their principals what was happening and found out, and they all started to converge to get mama home.

Ruth Moskop:

Oh, goodness. What an adventure!

Dixie Koldjeski:

What a day.

Ruth Moskop:

All right. I was just asking you to tell us a little bit more about the routine course of a day or a week providing care in a mental health setting.

Dixie Koldjeski:

And I asked you before or after Thorazine.

Ruth Moskop:

Right.

Dixie Koldjeski:

I think that I should contextualize this - that my experience, before Thorazine became generally used, was in one of the large state hospitals in New York; and as I told you, the one I was in had 12,000 patients. It was a city of the sick. In fact, they had movies made of these large institutional settings and called them "cities of the sick." That is not unique to me. But to go onto the ward - first off, I'd like to say that you had a key that if you hit somebody with it, it would be very painful. It was a heavy key, about four inches long, made out of some very strong metal because the locks on the doors were very substantial. Now, you could not go on those wards unless those keys were tied around your waist with a cord - oh, I don't know how cords are measured, but the cord would be about as large in circumference as that.

Ruth Moskop:

Almost a half an inch?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, maybe a quarter an inch. All I know was the first thing we did in the morning after we had to get our uniform on was we tied those keys on under our aprons and then pulled them around and got them in a pocket. And you just were literally weighted down; your dress was weighted down. And off we would go to the wards. You got to a ward and first you rapped on the door. There usually was an aid of some type on the other side who would tell - who would call for you to enter. The reason for that was that if certain of the patients banded together and decided that they wanted to get out, when the door opened, you know, they would come at you, and there would be no way you could restrain them because they were quite strong. There was nothing physically wrong with most of these [patients]. There were some wards where they had sick ones, but most of them were healthy. They walked and exercised and went to ball games. They had the usual recreational kinds of things that most of them went to. So when you knocked on the door, you got - somebody would holler through the door, "Enter," which meant that it was safe to open the door without somebody rushing you. So you got inside, and all parties concerned made sure that door was relocked. Now, you would be easily in a ward with probably 50 to 75 mentally very disturbed - I would say mentally ill folk - all sizes, but they were separated by sex - by gender today; but they were all sizes, shapes, colors, descriptions - an absolutely incredible mix in terms of the kinds of behavior they were using and the extent of their mental illness. The first thing that we did as nurses was to go to the office and check on the status of the medications, whether or not there had been accidents or incidents overnight, and, if so, who was hurt, and that was a big factor because we did not hand out the - about the only kind of medicine we had to calm people down were barbiturates, and you could not give very many barbiturates to people before they just absolutely became foggy and almost, like, many of them, barbiturate poisoning, so that you had to let a great deal of the behavior flow as it emerged and as they felt inclined to express it. But you would ascertain whether there had been incidents or accidents and, if so, what the nature of those were.

The next thing you had to check on was who was in security. Now by that, I'm talking about physical restraints - that is, straight jackets, cuffs - whether or not they were in isolation rooms, which was a very common kind of thing. They had - the walls - many of them were padded so they couldn't bang their heads, but it lowered the stimulation from out in that huge crowd. That would just key patients up until they were almost like robots. They just simply couldn't stop acting out. And you made sure - then you picked up your entourage of aids, and you went around and made sure that everybody in restraints - you checked their hands to see if they were loose. You checked - you went in the isolation rooms and made sure they were all right. You tried to talk because you would bring them out as soon as, you know, they seemed to be calm enough that they could tolerate the noise, the interaction, and the stimuli out in the big ward unit.

Then each of the wards usually had what was called a hydration room which is where they would be in tubs - tubs with water - and they would be sitting on a sling in the tub, covered, and the water would be at some temperature. I think it was quite tepid; I don't recall the exact temp., but it was very calming to put people in there who really were out of control. I know it was very calming because one time I got myself in one of them and had the nurses fill the tub up with the water at the proper temperature and they left me in there; and for me, I was sound asleep within a very short while. You get out, and you're like a prune, I would say, but it was a very effective kind of calming thing. And we have our versions of that today in spas for entirely different reasons. But you made sure that you went around that ward and you had a sense of who seemed to be on the verge of getting ready to act out, and many times the patients would have kind of a premonitory cluster of symptoms that once you got to know them, you would know that they were getting ready to have an episode of acting out. You would try also to talk to them - to stop intervening - to not have it go any further; and many times, believe it or not, that was successful, even though it was under the most - what would today be considered the most adverse circumstances.

Ruth Moskop:

So if they did have these premonitory symptoms, what could you do? Talk to them?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Well, usually the first thing, we would try to take them and walk them back to a quiet place right in the ward - not put them in the rooms but quiet them down and sit with them and maybe hold their hand and talk to them - not trying to rationalize anything but just to say - acknowledge that they - you knew that they were having trouble - they had troubled thoughts and that they were having trouble controlling their behavior - how frightening this very often was to the patient - was there anything we could do. And many times when you would ask that, they would say, "Put me in the quiet room because I think that would help me to get myself under control." Sometimes they would absolutely be kicking and spitting and screaming at you at which time, you know, four or five people would just have to surround them and remove them and put them in one of the rooms where they could bang, bat, or kick the wall and what have you. Nevertheless, you had to keep your eye on those people and keep going in there and asking - trying to establish some link with reality because if you didn't, they just got crazier and crazier in there by themselves. If you lose what reality - their reality was a ward full of people, and if you suddenly lose that and you're in a quiet room, you can just imagine how frightening this can be. So behavior at some point also became a way of getting your attention - the attention of the nurses and the aids.

So after you got a sense of the tenor of your ward in general and so on, the game - the merry game of handing our your medications started. Now, that was an experience in itself. Everybody had to have their mouth opened with a tongue depressor and a flashlight. Many of them didn't want to take it because there are side effects to Thorazine, and oh brother - listen, we were giving doses that today they don't even give; that is, the max. that they were given, and some of the people had those - once we had Thorazine, but before that, even any pill had to be watched to make sure it went down. Then if some kind of activity was scheduled on the unit, we would try to organize them enough to sit quiet so that the activity could go forward; but some of the people always would be ready to go for a walk or to a ball game, and they would get them. Then they'd come back for lunch, and that was always a very trying period, and it was a very dangerous period. I mean, they used plates - heavy plates. Now, that's fine in a Greek taverna in Athens, but when they're coming flying around in a dining, they're deadly weapons. They did not have forks and knives, but they did have spoons, and we would make sure they ate. Anybody who didn't, we tried to coax them or find something else. But we would get them back to the ward again. They had activities of some type, either in the ward or out, or if they didn't want to do anything, they - that was whatever they were of a mind to do, and that was the way the day went. Supper, again - always you had to have extra help because with silverware and stuff like that - but it was the plates that you worried about. And then they'd come back and you'd line up - divide your ward numbers up and allow, oh, 10 maybe - 10 or 12 to go to the bathroom and get ready for bed and what have you. And by 9:00, they all were in bed. That was sort of a day in the ward.

Now, let me tell you something. The Army wouldn't have me because I was puny. I worked in a mental hospital all those years, and I never once was hit or hurt. I was even pregnant on a ward with very severely disturbed men, and those men decided to hold a shower for me, and did. They had decided from my shape that I was going to have a boy; I did. And they had a shower, and they had persuaded the nurses to get them the cake and the ice cream. And at the little party that they had in the afternoon, the men themselves - there were two or three that wanted to be rambunctious, and they took care of it. But when they realized - I think they realized I was pregnant probably before I did. And I had noticed that they were following me around, and one day I said, "Tell me, why are you always at my heel?" He said, "We want to make sure that nothing happens to that thing you're carrying." And I said, "Oh, what are you talking about?" He says, "Well, that baby you're going to have." The superintendent of the hospital actually came to the shower they gave me - the men gave me.

I never in all those years of being on the ward with severely mentally ill patients - men and women - I was never hurt nor hit. But the only thing that infuriated me to the max was on one of the wards with newly admitted women, and there's - on those wards, there's always a question, you know, "What are they going to do? What" - you never really - there was a great deal of uncertainty about what certain ones would do, but there was a lady who wanted to go home bad, and she just was cutting up - acting out. She wanted to go through the door and go home. I had asked some of them to help me to change the linens on the beds, and they always liked - there were always women who liked to come in and help you do that. I'd been standing outside, came out of one of the rooms, and I had, you know, the big, round linen hoppers in the hospitals with the canvas? This lady approached me and she tried to take my key from around me, and that was impossible. You'd have to take me to take the key, which she did. She literally picked me up bodily and put me in this enormous laundry bag, you know, with my feet up, and I was immobilized. Can you imagine? My hands and feet were up. She stopped acting out because she thought it was the most hilarious thing she had ever seen in her life. Everybody thought it was a great joke. I am furious; I'm in this thing and have no way to get out, and finally I started rocking because I thought if I could turn it over, I'd crawl out. However, some of the women came, and they laid it on the floor and said, "Here, crawl out." So they picked me up, brushed me off, straightened me up, and said, "There, you're good as new." But the big state hospitals had very large occupational therapy programs; they had recreational therapies; they had hydrotherapy; they had every kind of therapy that - you know - for mentally ill people.

Ruth Moskop:

And what difference - how did Thorazine make a difference?

Dixie Koldjeski:

Thorazine made a difference in that it quieted patients down to the point that they could tolerate relationships. You could sit down with two or three of them and actually get them to start to consider their situation. It was simply amazing, the difference. But your ward would be much quieter. You didn't have the acting-out behavior that was so common - just usual. They would tell you of things going on in the ward - that so-and-so didn't feel well but didn't want to upset the nurse. They became in many cases the human beings, I guess, that they may have been at one time. That was the difference. The level of noise decreased; the acting-out behavior decreased. And by the same token, we didn't have to be - that is, the staff and the nurses did not have to be so vigilant to try to anticipate some of this behavior. We could spend our time, for the first time, in kind of relationship therapeutics. I think that, for me, was the biggest difference I experienced. And dining - oh, the meal time - it stopped being so horrific.

Ruth Moskop:

Well, you had many daring experiences in your life and had undertaken all sorts of adventures and challenges. It's amazing.

Dixie Koldjeski:

Yes. I was in a surgical unit. This was a building in this big state hospital that was - you couldn't tell it from an honest-to-God general hospital except the patients were all mentally ill. And I had an elderly woman of German descent who was my patient, and I don't recall but she'd had some surgery. And I - my clinical instructor - I was still a student at that time, so it was during World War II, and my clinical instructor came in. They watched everything we did because in those days, nursing was like the old nursing wardens in Germany almost. She said to me, "Ms. Dawson, can you come out here; I'd like to talk to you a minute." And I thought, "Oooh, I've done something wrong," because you never got praised for anything; it was always something you did wrong. I went out, and she said this lady's son was there to visit her and he had brought ice cream, and he wanted to have some ice cream with his mother - would I take care of it. And we had a little kitchen area and so on and so forth, and I said, "Sure." And she says, "Ms. Dawson, he wants you to come in because his mother thinks you are the best nurse around here. He wants you to come in and have ice cream with them." Well, one of the absolutely forbidden things was - one, to eat with a patient and second, to take gifts from a patient. And I says, "I can't do that. You know that's against all the rules." And she says, "Well, Ms. Dawson, I have just waived the rule. I would like for you to bring a dish of this ice cream - three dishes and for you to go in the room with Amanda and have ice cream with her and her son."

Ruth Moskop:

It's time to turn the tape. So how did the ice cream social go?

Dixie Koldjeski: