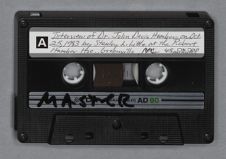

[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Dr. John Davis Humber

Narrator

with comments by Mrs. Roberta Marr Humber

Stanley L. Little

Eastern Office of the Division of Archives and History of North Carolina

Interviewer

October 25, 1983

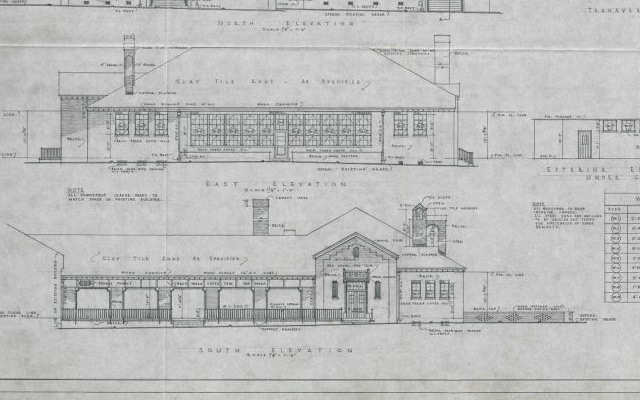

The Robert Lee Humber, Jr. House

Greenville, North Carolina

Dr. John Davis Humber - JH

Stanley L. Little - SL

Mrs. Roberta Marr Humber - RH

SL: Interview of Dr. John Davis Humber. Address: 106 Petrified Forest Road, Calistoga, California, 94515. Date of birth: December 5, 1895. Profession: Medical doctor. Place of interview: The Robert Lee Humber, Jr. House, 117 West 5th Street, Greenville, North Carolina. Interviewer: Stanley L. Little, staff member, Eastern Office the Division of Archives and History.

[Break in recording]

SL: Okay, Dr. John. Now, you were born in this house? Is that correct?

JH: Born in this house on December the 5th, 1895.

SL: Which room were you born in? (1:04)

JH: In the room that's supposedly the dining room now. It was a bedroom at that time. [unclear 01:11] It was added afterwards.

SL: Right. Okay, as you mentioned, there were many additions to the house. Can you describe it to me as you remember it as a boy, from your very youngest memories?

JH: As I remember it as a boy, [as you came in from the front porch] there was a room on the right, no rooms on the left, and the staircase came into the hall, went upstairs. On the right of the staircase was a bedroom, and then there was a small room on the left and the dining room. Going up the stairs, you came to a bedroom. There were two bedrooms at the head of the steps. No bedrooms on the right as you came up the steps; all on the left. My brother's and my bedroom was the first bedroom as you got up the steps and the other bedrooms were further out.

SL: Was there an attic in the house? (2:22)

JH: There was an attic but we never went in the attic. I never knew what the attic. My brother, Robert, as they said in this article yesterday, had to punch a hole in the roof to see what the attic was and added that afterwards. He made a library up there, which is a lovely room now.

SL: This is after he came back, after the war, came back to Greenville.

JH: Yes, after he came back from Europe.

SL: Was the kitchen wing here? Do you remember that as a boy?

JH: No. We had a little dining room and then we had a kitchen off of the porch. The kitchen was about... We came in. There was a back porch, a long porch that went at a right angle, and there was one little bedroom and bathroom here and a porch. Originally it had nothing but just the porch and, as I remember it, the kitchen was to the left here at the corner, then the dining room, and then the bedroom, and then from that was the sitting room on the first floor of the house. As you went down the steps here on this porch, as I remember as a child there was a very small walk, boardwalk, about two or three feet off the ground, that led from here over to a house which was sitting over to the right of us, and that was the old home before they built this house. My father lived in that before he was married and this house was built the year they were married. (3:59)

SL: That being 1895?

JH: 1895. They were married in the early part of 1895 and then I was born in December.

SL: Right. Whatever happened to the old home place?

JH: The old house was moved off and moved up to the right of Greenville up here called Negro Town. The old shanty was moved up there and the old Negro that stayed with us after the Civil War-old Mammy and old [unclear 04:32]-lived here in that. She lived in that old home, little house, that they moved up there, until she died. She died at a hundred and three years old. She really raised us in the family, all the children, mainly me and my brother. We called her "Mammy." A very fine old Negro woman. Her children turned out to be pretty good. My brother followed up her children and they all turned out to be pretty nice boys.

RH: They all went to college. (5:01)

SL: Every one of them?

JH: Every one of them went to college.

RH: I think there were seven.

SL: Well does the old home place still stand, or is it long demolished?

JH: Well, I tried to find it yesterday. I don't know that I could recognize the old shack or not. I think it must have gone now. I was here some years ago and went out and saw it and it was still there. There was just a regular little tiny porch going into to it and two doors, and there were two rooms to it, just two rooms in the house.

RH: As it stayed here, didn't Mammy cook out there? (5:38)

JH: They used to cook there first, before they got the kitchen going in here, and bring the food across to the dining room. Then they had this kitchen here. This was the kitchen, right here, and that was the dining room, and there was a porch right here that went to the house. Then from down here steps went down. I never will forget. One morning Mammy was standing on the porch here with a broom in her hand, and my mother or someone had ordered groceries from the grocery store and this little Negro boy brought the big bag of groceries into the yard. He came up and he started to set the groceries on the steps. Old Mammy came out and said, "Bring them there groceries in here and put them in the kitchen." He set them down on the porch and she got the broom up and she said, "You better bring them in." So he picked them up and brought them in and plunked them down on the table in the kitchen and started out and she got that broom and gave him a whack across the shoulders and said, "You get out of here," says, "You're just a plain nigger." Says, "I'm a colored person." [Laughter] (6:47)

SL: How about that? So then, this wing that contained the kitchen and dining room, was that added to the house later, or what?

JH: That was here when I first came here.

SL: Okay. This wing was built with a two-story section then.

JH: Oh, yes, that was here, and I stayed here and it was just improved and done over. I don't know whether they tore it down. I don't think they tore it down. They just redid the whole thing.

SL: Right.

JH: There used to be. There was an old basement to the house, but I was able to walk under it as a kid.

SL: So it stood pretty high off the ground.

JH: Fairly high. It was high enough for me, as a kid, to get underneath. Because, as I remember, I used to go under, and the ants used to get up under the brick pillars and eat little holes in the brick and make little brick dust, and I used to get that brick dust from the different colored brick and bring them out and put them on that porch and make little pills out of them, because I was a doctor from the beginning on. [Laughter] (7:48)

SL: That was your goal then, from childhood on, that you always wanted to be a doctor.

JH: Oh, yes.

SL: How about that? Well, one more question on the house and then we'll soon depart from that. The porch, then, ran right along the side of this kitchen and dining room, just a straight porch? Is that right?

JH: This porch-the back porch?

SL: The back porch.

JH: Straight right here.

SL: Straight through.

JH: It had a straight porch. The kitchen and the dining room and a hall came off from the porch where there was [unclear 08:16].

SL: Okay. Were there any other outbuildings here on the property-servants' quarters, or-that you can remember? (8:24)

JH: Oh, sure. My father's shop was over here, a wooden shop, over beyond that fence there. Next to the shop on the right hand side was a big wooden building called the blacksmith shop. That was his old forge there where he used to cast all of his brass castings for the moldings. I've seen him pour moldings with brass many a time. Then later on when he moved the old shop, which was about eighty feet long, he moved that down to the right and built a new brick shop, but the old wooden shop still stood there for a long, long time.

SL: The brick shop was the one that was just torn down in the last five or ten years?

JH: That's right, two-story brick shop. It was eighty feet long and about thirty feet wide, I think, as I remember, two-story.

SL: Well, how about this neighborhood, Dr. Humber? I know it's changed a tremendous amount through the years. Who were some of the folks? Like, where the Greenville City Hall is, for example. (9:22)

JH: Where the city hall is now was a lady named Mrs. Ada Cherry, and next to her, to the left behind her, was originally where the Methodist Church was built when I was a kid. Then diagonally across the street from us was the home of the Sheldons, S-h-e-l-d-o-n-s, Sheldons. Across the street from us was an old lady with an old picket fence called Mrs. Stokes.

SL: This is where Globe Hardware is today?

JH: Where the hardware is today was Mrs. Stokes. I'll never forget the day of the earthquake. We had a little earthquake here and it shook everything. My dad ran out of the house, ran out in front, and Mrs. Stokes was standing in front of the house and [unclear 10:17] and somebody came running down the street, and my dad said, "What was that?" This fellow came running by and said, "I don't know, but it went this way." [Laughter]

SL: How about that? Well, where did you and your brother, Robert, go to school at when you were growing up?(10:33)

JH: Where did we go to school?

SL: Yes, sir.

JH: We went to school at the old school grounds behind. When you cross Dickinson Avenue there was two homes, Mr. C.T. Mumford's and Mrs. Greene. Bob Greene is the boy that lived there. Then beyond them, next to them, on the other side facing Evans Street, was the old schoolhouse, which now is the new schoolhouse. The old schoolhouse was about twenty minutes' walk from here-or it took me around fifteen or twenty minutes to walk to the old schoolhouse-way up Evans Street on the left hand side of the street. An old wooden building, I think it was. I went to school there first. Then they built the new school and I went to final school here at the high school, up to the ninth grade. We had ninth grade high school. (11:29)

SL: This would be a building that stood where Sheppard Memorial Library stands now?

JH: Yes. That's the new school building. We called it the Grade School.

SL: The Greenville Grade School.

JH: Greenville Grade School, and we had everything up to the tenth or eleventh grade, I think it was, and then we had what we called high school. Mrs. Eula Cox was the principal of the high school. She taught Latin and everything else for us.

SL: What are your memories of school in those days? Was it really strict classroom-?

JH: [unclear 12:02] strict. H.G. Smith was the superintendent; a very fine man. I met him later on. I came back to Greenville later on in years and he was still principal in New Bern in a school over there. But Mr. Smith was. Mr. Ragsdale was I think one of the first men that were here, Mr. Ragsdale, a very fine fellow. I'll never forget [unclear 12:25 come by my home here] with his walking cane. I can see him now. H.G. Smith gave me. The only whipping I ever got in my life he gave me at school one day for fighting out there, which was a legitimate fight. I won't tell you the details of that but I got a licking for it, and that's the only one I ever got. [Laughter] (12:44)

SL: Well, how about growing up as a teenager here in Greenville. What type of activities? Did they have dances and that sort of thing?

JH: Very fine memory of my activities. We had some very fine associates here. I remember the Forbes boy, Percy Forbes, and his brother, and a girl down the street [unclear 13:09] and Patty Wooten. I can remember lots of others. Christine Tyson used to live up here this side of Dickinson Avenue. But we had some very fine. We had a lovely association at school. We never had any trouble; enjoyed our school. I remember we used to go across to the Mumfords. There was a big, high fence between the Mumford property and the school, and Charlie Mumford, who was Mr. Mumford's son and was a very good friend of mine, we used to sit on the top of that fence, as I remember, and watch the soldiers drill for the Spanish American War.

SL: So you remember that?

JH: Oh, yes. I remember that very distinctly. (13:52)

SL: How about that?

RH: He has a memory that goes way, way back when he was a very small child.

SL: What other type-? Did y'all have activities such as dances?

JH: No, we never had dancing. We were never allowed to go to a dance, we never had liquor in my home, and I didn't know what a pack of playing cards looked like.

SL: Well what did the young people do in those days for entertainment?

JH: We had parties. We had a birthday party. We'd have a nice party and our parents would give us a nice, lovely party, but we never had anything but just nice parties. I don't remember any other affairs we ever went to.

RH: Well, what activities did you do? Did you have ballgames?

JH: Boys played baseball, yes. We played baseball. I remember people like [unclear 14:37] Birch and [unclear 14:41] Ragsdale. I can remember the boys, [Mumford and others], we used to play baseball. We'd go to Winterville, and we went to Bethel, and we'd go around and play baseball. About the only activity we had was our baseball team. (14:55)

SL: Well now, was this part of your school activities or was this separate?

JH: School. That was a Greensville School activity.

SL: So even then y'all played different schools in the area.

JH: Yes.

SL: Right. Okay, of course you and your brother, Robert, went on from high school to continue your educations. Were your parents great supporters of education?

JH: Oh, yes, very much.

SL: They believed very strongly in it.

JH: Oh, yes. They believed in education to the nth degree, and I was prepared to go from here to Wake Forest University. When I graduated here in high school I think I was probably about seventeen years old; then I went to Wake Forest University. I graduated Wake Forest when I was twenty-one.

SL: You then continued your studies through the years. (15:44)

JH: I continued my studies from here to Wake Forest, and continued and got a Bachelor of Science degree at Wake Forest, which was preparatory for my medical. I took my first two years of medicine at Wake Forest under Dr. Wilbur Smith.

SL: Then I believe you also went to Tulane. Is that right?

JH: Well I went to Yale University from Wake Forest. I enlisted in the Navy at Yale. We were at war then. The war had started.

SL: Is this World War-?

JH: World War I. I enlisted in the Naval Reserve with the understanding that I would finish my medical degree. They let me finish one year at Yale and then they sent me to Harvard University, to Chelsea. I went there for, oh, I've forgotten how many months at the naval yard there. Then from there I took some courses at Harvard. When I went to Tulane University they transferred me to the 12th Naval District in New Orleans and I entered the junior class there. I really went back and entered the junior class at Tulane, and I graduated at Tulane in the last year of the war. When I graduated the war ended in November, I think it was, the Armistice Day, and. (17:07)

SL: Of 1919?

JH: 1920. I took my Louisiana state boards right then and passed my examinations and got my license to practice medicine first in the state of Louisiana. I was looking at my medical journal one night and I saw something about the Southern Pacific Railroad Hospital in San Francisco, and I thought to myself: My golly, if I could get a job with them I could get a pass out there and go out and see the west before I come back to Greenville to practice medicine. So I wrote to the chief surgeon of the Southern Pacific Hospital in San Francisco and asked him if there was any way I could get a job with them. In a few weeks I got an answer from Dr. [Frank A.] Ainsworth, Chief Surgeon of the Southern Pacific, stating yes, he'd give me an internship at the Southern Pacific Hospital if I'd come out. (18:11)

Well, I immediately wrote him and accepted, and then pretty quick I got an answer from him asking me where I wanted my pass sent. He was going to send me a pass. Well, that's what I wanted, a pass to get out there. So I wrote him and told him to send me my pass from Greenville. I telephoned my uncle, [unclear 18:29] he was senator then, Sen. Davis, who was a very close friend of Josephus Daniels, who was Secretary of the Navy under Roosevelt, and I said, "I wish you'd see Mr. Daniels and see if you couldn't get my discharge from the Navy before Christmas and send me a pass to Greenville," so he did. I was discharged November and he sent me a pass from discharge to Greenville, which was my final discharge, and I went to Greenville on that pass and I spent Christmas in Greenville and went from there to San Francisco with the Southern Pacific Hospital, and I stayed there until I became head of the hospital department, with Dr. [Walter B.] Coffey as chief surgeon. (19:09)

SL: So you were there for many, many years, then.

JH: Oh, yes. I was there until I retired from the hospital.

SL: When did you retire?

JH: I didn't retire, I just quit.

SL: [Laughs]

JH: I resigned and started private practice because they told me that if I stayed with them. When Dr. Coffey would retire there would be one man ahead of me, Dr. Walker, and after him I'd be chief surgeon, but I would have to give up my private practice. I said, "No, I won't give up my private practice for anybody," so I just resigned from the hospital department and started practicing medicine in San Francisco in 1920.

SL: So you've been practicing then in San Francisco-.

JH: At Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco, [900] Hyde Street, ever since 1920. I helped build that building.

RH: Came back to Louisiana and wrote a book on angina pectoris. (20:03)

JH: I should tell you that. I went back to Tulane in 1927, took a sabbatical year from the hospital, and taught anatomy. I was assistant instructor of anatomy, or instructor in anatomy, at Tulane University under Dr. Wilbur Smith, who was professor of anatomy. I was Dr. Smith's assistant at Wake Forest in anatomy when I was there. So I went back to Tulane, spent a year there as an instructor in anatomy under Dr. Smith, taught anatomy, and I wrote the book on angina pectoris, did all of the research, photographic work, and brought all of my work back to San Francisco and had it corrected, and Tulane University published our book, Dr. Coffey and myself-and Dr. Philip King Brown wrote a chapter in it-on angina pectoris. (21:02)

SL: I see here that you were involved with the Coffey-Humber treatment.

JH: Dr. Coffey and I became very close friends. I was his assistant and I became his associate and then became partners in our research work. We built a new wing to the hospital that was built under Dr. Coffey's supervision, and we built on the top of this new building a laboratory, a complete laboratory, a whole floor, for research, and we conducted our research laboratory in cancer. We were ready to read a paper on this research work, and a Hearst. What was this man's name? Lal, Mr. Lal, who was a-.

RH: Bernard Lal.

JH: Bernard Lal, who was a reporter for-.

SL: How do you spell that? (21:54)

JH: L-a-l, Lal. Bernard Lal. He was a reporter for the Hearst newspapers and he attended a staff meeting one night at the Southern Pacific Hospital and Dr. Coffey and I read our paper on our cancer research. I'd been doing the work on the bladder. We'd been doing our research on cancers of the bladder and we were making extracts from the different glands of the body, hoping that we could find one of the glands which was deficient, that was the cause of cancer, the same as insulin is the [cause of] diabetes. We discovered that by using an extract from. We made extracts from all of our different glands, but the extract we made from the suprarenal gland, which is about the size of the little finger over our kidney, when we made extracts from that we found that cancer was definitely helped. We didn't know whether it would cure it or not, but we started treating it. This man, Lal, when we read this paper, [he] got a hold of it and published it. Well, it went all over the world that Drs. Coffey and Humber had discovered a cure for cancer, which we had never claimed, but it went all over the world and within the next six months we had over two thousand cases dumped right on our laps in California. Then we established clinics in Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Bakersfield, and-.

RH: Santa Barbara. (23:33)

JH: Santa Barbara, and San Francisco, and we had over twelve thousand cases of cancer dumped on our laps from all over the world. We had men from England, from Japan, from all over the United States came out to see us. The Mayo brothers went out to see me in my home. I can name all kinds of. All of the research workers came out and we saw them. We had cases of malignancy that were. We never saw a case that we would accept in our clinic unless we had a definite letter from their doctor saying they had done all they could do for them, they were definitely diagnosed as cancer, and they couldn't help them any further. We had over twelve thousand cases in our clinic eventually, which we reported on to the medical profession, and we had some cases that lived over thirty years after they were diagnosed with cancer that were still living. So we do feel that that theory of ours is still being worked on and is going to be proven to be the real cause of cancer eventually. I hope it can be proved. (24:39)

RH: The Mayos have been out and then they went back, working with their exact extract, and that's when they called it cortisone.

JH: Yes, cortisone was discovered from our work. The Mayos came out here to work with us. We discovered that people that came to our clinic that had arthritis and cancer both, that the arthritis would clear right up as soon we gave them the extract. So they went back and they worked on it and they found out that the extract, which. We were making it from the whole gland, but when you made the cortical portion and the suprarenal portion differently they found that cortisone was made from the other part of the gland.

SL: Well, my goodness, you really have made a significant contribution to the world of medicine, Dr. Humber.

JH: So cortisone is really an outgrowth of our work, and I reckon. We never got credit for it, which we didn't want anyway.

SL: I see here that you're also a founder and member of the World Medical Association. (25:32)

JH: Yes, I'm a founding member of the World Medical Association and I'm a founding member of the American Academy of Family Physicians that was founded in San Francisco thirty-six years ago. We just had a meeting in Miami-I just came to it-our thirty-sixth. I've got my pin on now, a thirty-six-year pin. I'm a member of that.

SL: A thirty-six-year pin.

JH: Yes. And I'm a charter member and past president of the Lion's Club of San Francisco. I've got a lot of nice memories of my medical work.

SL: Indeed you should. Okay, so far as your brother Robert Lee Humber, now he was an international lawyer. Is that true?

JH: Right.

SL: Was his dream always to be a lawyer as yours was always to be a doctor? (26:22)

JH: He always planned to be a lawyer. He liked talking. He liked speeches. The other day when I was here I was up in this upper left top room here that was our bedroom. I was relating to them I can remember so clearly one Sunday afternoon. My little brother, Robert, who was two years younger than me, one Sunday afternoon he decided he wanted to do something, so he arranged three chairs in the room and a little box with a little stand, and he went out and got my mother and father and they sat down, and I sat down, and he got up on the little box and made a speech, and I'll never forget the first words he spoke. He says, "George Washington was a great man." [Laughter] That was the first time I remember him-.

RH: I think he was only about five then.

JH: About five years old then.

SL: His first major speech there. [Laughs]

JH: First major speech when he was five years old: "George Washington was a great man." (27:23)

SL: Now, he went on to continue his education at Wake Forest.

JH: Yes, he was two years behind me. He graduated after me. He went from there to.

RH: Harvard.

JH: Harvard University, but he had made his mind up he was going to be a Rhodes Scholar. He started football at Wake Forest. You had to have one athletic so he chose football to be an athlete. He played football, he went on to Harvard, he received his degree at Harvard after graduating from Wake Forest, and then he became a Rhodes Scholar. He got his Rhodes Scholarship from Harvard and went to Oxford University and spent. I've been to Oxford University, to the college that he was attending there. He graduated Harvard, and while he was at Harvard he probably won some of the highest honors there. One of them was a scholarship to make a trip around the world.

RH: That was from Oxford. You said Harvard. (28:28)

JH: While at Oxford University he won this scholarship which gave him a [trip] around the world, and he went around the world. The scholarship, the money that he received from that, didn't pay his way entirely around the world but my dad used to send him money and he went around the world. When he got to England he bicycled all over England, and the stories that he wrote my mother-page after page of typewritten stories every day or two-of his trip around the world is really a history in itself. The experiences he had in his trip around the world is worth any. I wish I had it in a book form.

SL: Well, I am sure it was a fascinating story. Now, he went on to live in Paris. How did he come to live in Paris?

JH: Well, when he was an attorney, he became associated with a man named Tom Gilchrist.

SL: Tom Gilchrist? (29:32)

JH: Gilchrist, who was interested in oil in Texas. Robert and Tom Gilchrist became very closely associated. The Gilchrist Company evidently drilled wells or something and found this oil on some property, [and] somebody bought the land from Gilchrist. I think he paid him a few thousand dollars for it. Two men came out and bought this land, which had not really been. No, they bought the land from Gilchrist and they drilled the wells and found that they. They knew that there was oil there and they drilled the wells, found the oil, and the government made them give that land back to Tom Gilchrist because he was Indian. He had Indian blood in him-over a twelfth or whatever it was-and they made them give it back, and the Gilchrists formed the Gilchrist Oil Company. My brother, being an attorney, organized and formed the Gilchrist Oil Company of Texas, and that's where the Gilchrist Oil started, which I still have stock in. He went to Europe as representative of the Gilchrist Oil Company in Europe, and he lived there for twelve years, I think it was. (30:45)

RH: Sixteen, I think.

JH: Sixteen years, or something; from twelve to sixteen years.

SL: From twelve to sixteen.

JH: He left there during [World War II]. His experience. He knew everybody in Europe. He was a man that met everybody. His experience and the people he met-.

RH: He went by bicycle. He really met people.

SL: Definitely.

JH: He met people from all over the world. He became associated with the highest men in Europe. I remember he told me about sitting down with de Gaulle and talking with him at dinner, talking with one of the head men of Russia, and I don't know whether it was. What was the name of him?

RH: He's the representative of Russia in the United Nations, I think.

SL: Andrei Gromyko? (31:27)

JH: Oh, no, before then.

RH: No, Gromyko was there [unclear 31:30] to the United Nations.

JH: He was sitting at the table talking with Gromyko and one of the-Stalin, I think it was.

RH: It wasn't Stalin, it was Gromyko. I'm sure.

JH: He asked this man, he says, "If the United States goes to war with you today, who'd win?" He said, "You'd win," but he says, "If you'll give us five years, we'll win." That's the answer he gave my brother years ago. My brother was the originator and founder of the first work for world federation and one of the presidents of the Federation of the World. He held the first meeting for world federation on Davis Island out here. They had the charter.

SL: That was the movement for world federation? (32:11)

JH: [Yes], and he was going around the United States getting each state to pass this resolution. He lacked only a few states. If he could have gotten I think one or two more states to pass it he would have gotten the resolution through Congress originating a world federation, and other countries like England and France and South America had agreed with him that if he'd get the United States in they would form the world federation. That was his aim, and of course he was the delegate to the United Nations at San Francisco when it was organized.

SL: In 1945, at the Dumbarton Oaks. Was that the Dumbarton Oaks Conference?

RH: No, that was the founding of the United Nations.

JH: The United Nations of the world, the charter was presented and adopted in San Francisco and he was a delegate there.

SL: Right. So he was very involved with world federation.

JH: Oh, yes.

SL: Did he advocate a certain type of governmental structure? (33:17)

JH: He wanted the United Nations to be the United Nations of the World, the same as the United States of America, and he said the only way that you can form a United Nations to have a world government would be a United Nations such as the United States. When they were preparing the charter for the United Nations he knew Secretary [Cordell] Hull fairly well and he went to Washington and asked Hull to let him see the charter. He knew Hull was writing the charter. Hull said, "All right." He said, "I'll let my secretary here, who's really writing that charter-I'm correcting it and telling him what to write but he's writing it for me." Robert, my brother, said he went in to talk to Hull's secretary and he talked with him for three hours about that charter, that he was not putting things in it that should be, and he came back in to Secretary Hull and he said, "Sir, you put the veto power into the charter, which will never work, and there are other factors in this United Nations which has to be patterned after the United States which will never work unless you do," and he says, "You must not have the veto power," because the veto power was for the United States, Russia, and England. Any one of them could veto anything and it would not go through. He says, "I wish you'd go back and talk to my secretary and see what you can do about that," and he went back and he talked for three hours with him, trying to get him to change that veto, and he wouldn't do it. Now, the man that wrote that charter for Sec. Hull was named [Leo] Pasvolsky, a Russian-born native. Now, there's the answer. I know that to be true. (35:04)

SL: What a coincidence indeed. [Laughs]

JH: I don't know if anybody ever told that or not, but I know that to be true.

SL: Right. Well, Dr. Humber was also very involved with the establishment of the North Carolina Museum of Art.

JH: Yes.

SL: How did he become interested in this, and how did he work to establish it?

JH: Robert was always interested in art. He was an artist from the beginning. [During his] time in Europe he knew where all the different paintings, beautiful paintings, where the artists had their finer paintings. Just as [World War II] was coming on, when France was collecting all of the metal they could get to make ammunition out of, Robert knew the man that had the original plates for the etchings of Rembrandt, and he got to that man and he bought them and paid for them so much a month, and he put them away and hid them because he knew the government would get them and they'd melt them up. He brought those etchings back to the United States and put them in the bank in- (36:22).

RH: The Chase Manhattan Bank.

JH: The Chase Manhattan Bank in New York, and kept them there, and then he brought them to North Carolina eventually when he. He then went to work to get an organization in North Carolina for art. He was a senator and he had a bill passed in the Senate for North Carolina to donate one million dollars for him to form a North Carolina Museum of Arts. When some of the men in the Senate didn't like the bill, one of them put a rider on it that he'd have to raise another million. They knew the bill was going to pass so they put a rider that he had to raise another million before he could get that million. So it passed, and he got on the train and went to New York, saw George Kress who was head of the Kress five-and-ten-cent stores, and he gave him another million immediately, and he came back and-.

RH: A million dollars in paintings, and Robert.

JH: No-.

RH: .asked to be able to choose them. (37:30)

JH: He came back here with the million dollars-the two million dollars-and established that, and George Kress, through the Kress Foundation, donated some of their art to the museum, and that's the way he started the North. He had an awful time getting that first check through. He had to even fight to get the attorney general, or whoever it was that was supposed to sign the check, to sign it, and he had to have even a court action to make him sign it. But he got it signed and there's a history of how he got that signed.

SL: So he had a tremendous struggle establishing-.

JH: Struggled all the way through, and the North Carolina Museum of Arts would never have been formed if it hadn't been for Robert.

SL: Well, the State of North Carolina can certainly be proud, because there's a wonderful collection up there.

JH: It's one of the finest museums in the world.

SL: It's a credit to Dr. Humber. It certainly is. (38:20)

JH: We have paintings in there from all over the world. There's a statue there that my wife and I donated-we donated it in memory of my former wife-of Bacchus, and it was a carved stone statue. Bobby, you'll remember what we paid for it. She says eight thousand dollars. I don't know what it was worth to start with. But anyway, they said it was worth eight thousand, so my brother said, "You can put that in and deduct that so much a year." Well, I did it, and the government wouldn't accept it, but finally the government said, "If you'll have it authenticated we'll grant it."

Robert got the best sculptor in New York State to come down and authenticate it, look at it, and he started studying it and he found out that that statue was one of three statues that were carved by the artist over-.

RH: Two thousand years before Christ. (39:18)

JH: One of the statues was in the Uffizi Museum in Europe, this one was the second one, and they didn't know where the third one was. But, on our trips around the world, we found the other one in Ethiopia and got a picture of it from the-.

RH: Carthage.

JH: In Carthage, Ethiopia, we found the other one and got a photograph of it and brought it. So they have one of the earliest carvings in the world. Whether they realize it or not, I don't know.

SL: So now the whereabouts of all three of the statues are known.

JH: [We know] where all three of them are.

SL: I've heard it told that Dr. Robert Humber was a very exacting person, particularly when it came to measurements, such as in the construction of this house. It had to be precise. Is that [true?] (40:05)

JH: He was the most meticulous man I've ever known. I can tell you another expression of it. In that front room on the right as you come in, called the library, there's a beautiful molding that goes all the way around, and that molding has thirteen-I think it's thirteen-different types of molding. Anyhow, it's a large number. It took him about seven years to get this house built like he wanted it in that particular room, and he kept telling them to change this molding, and when I was out here a couple years ago I was going through the house as they were beginning to renovate it, and I found in one of the closets a model that he made of the molding to go around, and it's about eighteen-.

SL: It's still in there to this day.

JH: I took it back out to California and I had it out there, and it was a model of the molding that goes around that hall.

SL: Okay, right. There is another sample, a smaller sample, of the molding in the library-. (41:05)

JH: You see now the molding is there, just like this model that he made.

RH: He says there's also a.

SL: There's another small piece of-.

JH: I didn't know he had another one. I had to go to the supervisor and get permission to take [the one I found] with me.

SL: [Laughs]

RH: I'm sorry, but it's getting late.

SL: That's all right. Well, I believe we have-.

JH: I'm enjoying it.

SL: Well I believe that we have pretty well covered-.

JH: Let him finish and don't interrupt him. (41:31)

SL: [Laughs]

RH: Well, that man is going to be waiting.

JH: Well, he can wait a minute.

SL: Well, I had pretty well covered the different topics that I wanted to talk with you about today. As I said I had a set list here, and I knew y'all's time is very important, and that pretty well covers everything that I have listed here. But I would like to say that it has certainly been a pleasure and I appreciate y'all taking the time to come by and talk with me about the house.

[Transcript ends at 41:54]

I'm extremely disappointed to see such racism displayed while painting this man as a reputable figure. This is a shame

We appreciate your interest in our collections. Historical records represent the opinions and actions of their creators and the society in which they were produced. Therefore, some materials may contain language and imagery that is outdated, offensive and/or harmful. The content does not reflect the opinions, values, or beliefs of ECU Libraries.