[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. ANDREW BEST March 3, 1999 Interviewer: Ruth Moskop Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn 17 Total Pages Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: Today is March 3, 1999. I'm Ruth Moskop and I'm here to interview Dr. Andrew Best at his office on Moyewood Drive in Greenville, North Carolina. Dr. Best, do I have your permission to record this interview?

AB: Yes. You do.

RM: Wonderful. Well, we left off with our last interview talking about the integration of the hospital, Pitt County Memorial Hospital and I was hoping that we could start today with a discussion of some of the scientific, medical challenges you've faced over the course of your practice of medicine.

AB: Well, as I have alluded to in other conversations, I opened my office for practice in Greenville on January 1, 1954. As of December 31, 1998, I have completed my 45th year of the practice of medicine in Greenville, Pitt, Lenoir, Edgecombe, and surrounding counties; the whole county area. It is really unfortunate in a manner of speaking that when I came to Greenville, as the lone minority physician in a whole wide area, and I found myself serving not only Greenville and Pitt County, but I had patients from all the surrounding counties; Martin, Beaufort, Craven, Jones, Lenoir, Wayne, Edgecombe, and Wilson counties. All of these surrounding counties.

RM: Did they come to you or did you go to them?

AB: No. They came to me. People who were looking for a minority physician, mainly the black folk who had experienced some difficulties in getting treated by the white physicians in their communities or who lived where there wasn't a minority physician. I suppose to be real frank and honest about it, my name and fame went out through the surrounding communities that Best was a physician who has compassion, and he will treat you at any stage in life, from rags to riches. He will treat you money or no money and this kind of a thing went before me. So, I had a lot of people coming and saying that they had heard about me. Well, in many instances, it increased my workload, but it did little for my payroll. But, I took all of that in stride, since by nature I was a person who was service oriented. I believe very strongly that my mission in life was to serve people, and I had a little slogan that I would put patients before paper or other considerations. Now, I say that because in many instances, the surrounding paperwork associated with the medical practice goes from tremendous to horrendous. Sometimes I would have some insurance company representative or some lawyer call and say, "Well, I want a report on Ruth Moskop." I'd say, "Well, I haven't gotten that report or it's not ready yet. I've been busy." At any day, I may come in this office and I have plans to do a certain amount of paperwork. If a patient should show up acutely ill or in distress, the paperwork would have to wait. That was simple. Anecdotally, I had to tell one lawyer who decided he was going to threaten me. He called several times, one day right behind another. He'd have his secretary call and talk with my girl, then he called and asked to talk to me. I told him, "Well, now I've been just as nice as I could." "Well, when do you think you're going to get it ready?" I said, "I don't know. It all depends on what my patient load happens to be. That's something I can't determine." Because at that time, I didn't have a policy of scheduling patients for appointments. I was working on the premises that from the time we opened the door, it was a "you all come" situation, where he who came was he who got served. No matter how long it took me, I never considered leaving until the last patient had been served. So, anyway, this lawyer called me in an attempt to threaten me. He said, "Well, you know I can have a judge to subpoena your records." I said, "Well, okay. That's fine. But, after you subpoena them, what would you do with them? You couldn't interpret them. I alone can interpret my records and any interpretation that you would try to make would not serve your purposes in a suit." I said, "Look, I don't mean to be rude, but I don't have time to go into this discussion and please don't call anymore about this case. Because when it gets ready, I'll have my girl call you." So, that went on off. It so happened that the head of that law firm was in that Senate, in the state of North Carolina, in General Assembly. He came and dropped by to see me, actually on a political mission. He wanted support. After I found out what he wanted, we discussed that. I said, "Well, let's get into the complaint department here shortly." He said, "Okay, what's the matter." And I told him one of his coworkers had, I thought, harassed me a little bit unnecessarily. I said, "Now, I tell you what I can do. I have a lot of patients who have been coming to your firm. I can direct those patients to use another firm or better still, as long as they have your firm, I will not be their doctor." I said, "Now, because this sword has two edges and it will cut both ways. Now, if you all want to play the game of harassing me, the doctor, you know we can play it both ways now." He said, "Oh, no, no, no. Don't worry about that. I'll take care of that." I had a letter from his coworker asking about a claim and the letter started off, "This is about the third request and I don't see or understand why I can't get this report. It has been two months or three months", words to that effect. So, he told me, "I'll take care of that." Sure enough, he did. I didn't hear anymore harassment from that particular firm. I mentioned that to show some of the anecdotal aspects of trying to practice medicine in a setting day by day, where my attention is diverted in many instances from medicine, pure medicine. Some say with the practice of medicine, it comes to getting your paperwork back according to what the lawyers do. I reminded this particular attorney of cases where I had been harassed for a report and "Well, if the doctor just gets his report." They tell the patient, "Well, you call your doctor and you tell him that we need your report, because we can't do a thing until we get his report." A case in point, I have one lady now who's report, as well as a subsequent report, has been in a lawyer's hands about a year and a half. The case still isn't settled. So, that just goes to show you some of the intangible parts of it.

RM: Does she need Workman's Compensation? What kind of ...? What caused her to take her case to an attorney?

AB: Well, in many cases, just a... Well, most of the cases are motor vehicle accident cases, where you know there is liability insurance that's involved. If you hit me from behind, so to speak, you are in fault and your insurance has to pay.

RM: I understand.

AB: Yeah. So, those are most of the cases. Of course, now if a person gets hurt on a job, they kick in with Workman's Comp. Now Workman's Comp will maybe allow so many weeks or so many months, depending on the seriousness of the accident If a bone is broken and they have to go through rehabilitation and therapy, that's a different case all together. The run of the mill case that the lawyers would be involved in is the accident case-motor vehicle accident-and they will put their ads on television, "If you have an accident, call your lawyer." Instead of trying to determine the seriousness of the injury and get medical attention, they're saying call your lawyer. I tell all of my patients, "Look, you get a hold of your doctor. Let your doctor try to get you well and you have the option of discussing your case with the adjuster, and if the adjuster doesn't satisfy you, then you can say, well, I'm going to tum this case over to my lawyer." In other words, I would tell them that so that they don't be rushing to get to the lawyer, because the lawyer represents a doctor's secretary's nightmare.

RM: You mentioned automobile accidents. Do people come straight to you from an automobile accident?

AB: Usually, they go to the Emergency Room first and when the emergency doctor determines that it may be a sprained shoulder, or a seatbelt injury, or a chest injury where the person hit the steering wheel; injuries like that where there are no broken bones. Then, it's a case where we have to treat them medically and sometimes, we do have to send them for therapy or for exercise depending on ...especially like whiplash injuries where you're hit from behind where your neck goes back like this. You get a strain when you pull on those cervical nerves. It can be rather disabling.

RM: When people were admitted in the Emergency Room, then would they sometimes call you over?

AB: Well, usually, now in the early days before this new expanded hospital got here, they would call the attending physician over and I'd go.

RM: And sometimes that was you.

AB: Yeah. If it were my patient, I would have to go. In these latter days, latter years where we have a whole crew of emergency medicine people, the family doctor or the attending physician does not have to go out every time. The emergency doctor takes care, does the first line of evaluation and treatment. Sometimes, they would call and say, "I have one of your patients here and these are my findings." They will arrange to...they'll tell the patient to call the office tomorrow or if it's over the weekend, they'll tell the patient to call the doctor's office Monday and set up an appointment.

RM: As a follow-up?

AB: Yes. For a follow-up. That's right. That's the way they handle it now. The pressure isn't as great on the family doctor, the lone doctor out here who's a solo practitioner like I am, so far as getting up and coming out all times of the night. I'll get a patient with an injury on Friday, the patient will show up Monday in the office, having been treated in the Emergency Room.

RM: How did it work when you lived in your clinic, basically in the early days? Did people show up with all sorts of problems; lacerations and emergencies at your door?

AB: Oh, yes. See, I used to do basic...if my patient went to the Emergency Room, the Emergency Room nurse would call me unless it was really a terrible case that required a lot of surgery, I used to do all of my lacerations in the Emergency Room. See that's in the early days. I liked these latter days much better since we got. ..I mentioned before where after I had been here for 26 years a lone ranger, Dr. Land came aboard and then about three or four years later than that, Dr. Artis came aboard and then later, Dr. Trent, where I had some coverage. Now, prior to the days when another minority physician was on staff, or available, Dr. Hadley and I used to exchange services. He was a white physician, very much down to earth, a very good doctor. We had us a thing going, if I saw one of his patients, I'd say, "Pay Dr. Hadley." I'd just tell them. If he saw one of mine, he'd say, "Well, pay Dr. Best." So, we exchanged services. There was no dollar exchange in it, whatsoever.

RM: I seemed to remember that you described a time when you had a small area to work and you were very happy to have it and you had a cot there, you actually slept in your office facility.

AB: Yeah. That was when I first went into practice.

RM: Did the patients realize that you were there 24 hours a day?

AB: Yeah. Most of them did and they would call all times of the night for whatever. A lot of times, I would listen to their story. I'd say, "Look, check in at the Emergency Room." Then I would call the emergency room doctor and tell him that the patient was coming in and they had been injured. Now, in the early days, my leaving home to take care of the patient in the ER really depended on the nature of the patient's injuries as well as who the doctor was that was on calL Now, some of the doctors who were on call would not agree to go ahead and see the patient, but looking at the roll, the call roster and sometimes if I had forgotten, I would pick up the phone and checked with the nurse and say, "Who's on call tonight?" They'd say, "Well, Dr. Minges is on call or Dr. Hadley is on call." I'd say, "Let me speak to him." Then I'd just tell them what I had and they'd go ahead and take care of it and I wouldn't have to go out. In other cases before we got this expanded hospital, I would have to go out and take care of my own and that was just another layer of responsibility. Now, we were supposed to mention maybe some cases that I had had and how they went through. In my experience, if I do an overview of my experience in this particular setting, aside from the segregation battles that I had to fight and the discriminations that we experienced, I would say that my overall practice and existence here doesn't leave too much to be desired in terms of ...I think my basic experiences have been good. There were people on the staff who were very sensitive to my call and what I needed to help in terms of consultations, like Dr. Malene Irons and Dr. Earl Trevathan, who was another pediatrician; Dr. Minges and Grattis, who were surgeons; internal medicine, the late Dr. Brooks and some of the other internists. They would answer my consultation requests. I think that I faired very well and my opinions and voice were heard. Now, I call to mind a couple of cases. One case was a lady who had an ulcer on her left leg. I admitted her. It was infected and there was a lot of circulatory problems marked with it. She stayed in the hospital for 93 days. The surgical consults, the orthopedic consults were called. The orthopedic people examined her and evaluated and they recommended amputation. I said, "No. Let's keep doing what we can to see if we can get the dorsal to heal." I had one of the Internal Medicine, Dr. Artis, to see on consultation. I had an ally to say, "No, just hold the knife." After about two months or sixty days or so in the hospital, there were some signs that it looked like it might heal. So, we kept daily dressings and finally it healed to the point, that we had the plastic surgeon to see her and he decided that he thought we could get some good success for grafting the ulcer. We got the leg healed up and she went home...

RM: With two legs.

AB: ..after 93 days in the hospital with two legs. She still has two legs, fifteen to twenty years later.

RM: That's wonderful.

AB: Another case that comes to mind is young man who, that's in a later setting, when we had residents into the expanded hospital. A young man came in and I examined him. He had some pain down the right lower quadrant. He didn't have the typical signs of appendicitis. I said, "To be sure, we'll send you over." So, I sent him over to the Emergency Room and called and asked the emergency room doctor to have the surgical resident to evaluate him. So, the surgical boys went over and called me back and say, "Well, Dr. Best, we can't find anything to go upon. He doesn't have any temp and we've done some x-rays and we don't see anything going on in the abdominal and the abdominal cavity. Our examination is negative, so we just don't know. Maybe, we'll send him back home." I said, "No, no, no. Listen, why don't you let his fluid keep running." He was giving him an IV, which was standard routine because he wasn't eating and naturally, they were holding off on the food in case he went to surgery. So, I said, "Let your IV continue and when I catch up here, I'll come over and we'll talk about it." So, I went over and the young surgeon said, "Well, we just don't think that we got enough to operate." I said, "Well look, here's a person, even in the absence of fever, in the absence of any positive finding, any absence of an elevated white count, any absence of anything pointing to an infection, he still has appendicitis until we can prove it otherwise." So, that was about 2:00 in the afternoon. So, they agreed. They said, "Well, we'll observe him a while." About 6:00, I got a call from a young man who was the Lead Surgical Resident. He said, "Dr. Best, we repeated this patient's lab work and we think now that he has appendicitis and he's on his way to surgery." I said, "Okay." So, they did the surgery. Sure enough, he had appendicitis and it was just to the point it was almost ready to rupture. They got it just in time to avoid a lot of complication. So, one of the young surgeons asked me, he said, "Look, why were you so insistent? What did you know that we didn't know?" I said, "I'll tell you. Here's a man who had been on a job for about fifteen years and hadn't missed a day, hadn't taken a day off, and hadn't been sick a day. When there was enough going wrong for him to come in to contact me, whether we found it or not, this man is sick. So, going on that history of my knowledge of the type of individual that we had, he is not a guy who will cry at every little thing or exaggerate the situation. In fact, he's so stoic, he might be half-dead and still be denying the fact that he is sick." So, that case went off very well and I got a lot of commendations and compliments on sticking with the case. Even in the face of my specialist saying one thing and I'm saying, "No, no, no. Caution here."

RM: You have to be tenacious.

AB: Yeah. And it turned out to be right. We have participated in any number of other cases throughout this career from complicated cases to routine cases, but I can't recall any case where I felt that the medical service rendered was not adequate or not well, at least acceptable or commendable. Now, I did have one what I call unfortunate case. I was doing obstetrics. A mother had not had any prenatal care and she showed up to see me in her mid-eighth month of pregnancy. She had all kinds of venereal warts and vaginal discharge. She was in terrible shape. Well, I went on to treat the warts and gave her penicillin to help get the infection cleared up and we got all of that external stuff cleared out before she went into labor. We delivered the baby and she was a diabetic, too. That was a complication. During the delivery of about a twelve pound baby, there was some pulling. So, we got some tension where that nerve plexus up here in the neck, the brachial plexus, that nerve got stretched and it had some weakness in that right upper extremity. Now, the mother went on and in about eight or nine weeks postpartum, she was pregnant again. All of this treatment for the baby, delivery for baby number one, if I got a penny, that tape recorder has got a hundred dollars. The second baby came along. I delivered that baby, too. No compensation at all and the only difference was I did get a chance after having talked with her and counseled her, if you're pregnant, don't stay away to the last minute, you need some prenatal care. She did a little bit better, maybe she got in two or three visits before the time for the baby. But things went along and the family away up to New Jersey. At twelve years old, this first child was twelve years old, the deputy sheriff came by and delivers me one day, here at the office, delivered me a subpoena where I was being sued for malpractice. It involved the delivery of this baby, because now the child had grown up. At twelve, he was almost six feet tall. He had a little bit of weakness in his right upper extremity, but he played basketball and all that kind of stuff. But, yet the father was one of those guys who were always figuring a way to get something for nothing. So, I found myself faced with this suit for malpractice. Well, I had people like Dr. Malene Irons, and it so happened that I recognized the situation before we left the delivery room. I called Dr. Trevathan, who was one of the pediatricians and he came in. He was practicing neuropediatrics. He evaluated the child and the child did have some birth injury, which he felt was unavoidable when you put all of the circumstances together. The suit was for $250,000. They had a lawyer from Wilson who came over and they took dispositions. Dr. Trevathan testified for me, Dr. Malene Irons testified for me and several other people that were doctors here on staff. In the final analysis, the insurance company decided that rather than to go through the hassles of going to court and fighting it...See they made them an offer, the insurance company made the gentleman and his lawyer an offer, so they ended up paying them $10,000. With the proviso that I had done nothing wrong and no admission, it was just making it an administrative settlement in lieu of going to court. I was tempted to say, "Let's go to court and fight this out." When my lawyer here showed me the document that the other people agreed to, in my case, in legal terms, without prejudice; we will settle in the case without prejudice to me. So, we settled that. That's one of the most horrendous things that has ever happened in terms of the actual practice was concerned.

RM: I know that was traumatic.

AB: Very traumatic.

RM: What have you seen, it may have changed over the course of time, but what have you seen as the most significant threats or problems in black health care since you have been practicing here in Greenville, or some of the most?

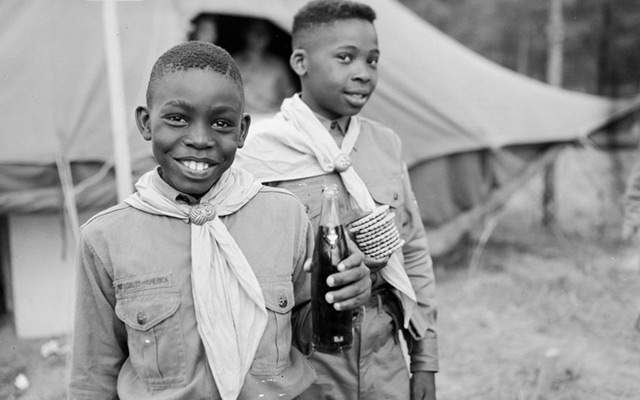

AB: Well, some of the real problems are traced back to the lack of education on the part of parents who would let their children off or would not get them in for immunizations and for preventive health care. Now, that's a part of it. It goes without saying that the usual diet in the poverty-stricken family was not as good as the more affluent family. Now, it had nothing to do actually with race except the fact that most of the total poverty-stricken people are black and their diets are deficient. By their education level not inspiring them to keep up with preventive medicine, the health department clinics, and not participating with their children to take advantage of what's available. Now to me, that's a tragedy. That's a tragedy.

RM: Has it changed at all?

AB: Well, yeah. I have seen some changes for the better. The health departments and the clinics who work in the area of preventive medicine and of course, about 15 to 20 years ago, mental health became of concern and became recognized that there may be something wrong seeing children developing. Even in adults, that is not totally physical. One of things I want to talk about at some point, in terms of supporting education, this organization that I founded, which is called the North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship, which was founded as a vehicle to work with those students that I had coming in every Wednesday night. That group was one of the first groups to promote the concept that health may be the finest physical, mental, and moral soundness, a state or well-being, freedom from disease. That is the definition of health. Now, what is the definition for disease? Now, we promoted the definition that a disease is any deviation from the normal state of health and we illustrated it by saying...See, now we found the concept out there across the nation that the word disease applied only to the infectious processes; the pneumonia's and the infections of syphilis and appendicitis, the infectious process. But you got out of the door and you stumble and break your big toe, that is a disease, a disease that comes from trauma or injury. Why is it that it fits the definition for disease? Because it is a deviation from the normal state of health for your big toe.

RM: Let's say that I go home and my husband beats me, what does that do to my health?

AB: Oh, yeah. That is a disease, too. All of those bruises and contusions are a deviation from the normal state of physical health. Now, that same illustration goes over to the mental side of it. When he abuses you to the fact that every time you leave home and come back, you go to the shopping center, you get stuck in traffic, and you're 20 minutes late getting back, and without asking any questions, he starts whipping up on you and accusing you of having had some social fling with some Joe Doe. Well, you see that goes right into the mental side of it. Your mental state has got to be impaired. It can't be normal in its function.

RM: Did you ever find yourself in the position of counseling people with that kind of difficulty?

AB: Yeah. That's where that broad definition that I have been working and promoting comes in. Even at the level of the National Medical Association in Organized Medicine where we promote that same concept that help has to be looked at in its entirety, whether its physical, mental, or moral. Of course now, we decided to leave most of the morals to the ministers and the churches. Now in my association with young people and doing a lot of counseling with special reference to preventive medicine, I tried to strike having grown up in a very religious family. I mentioned very early on that I make no apologies for my religious beliefs and my spirituality at all, but I find myself saying to and trying to impress or to counsel some of the young kids, the high school kids that there are some things that you just should not do because of your own internal behavior mechanism and this was a large part of ...In fact, see in 60...

RM: You mean your own understanding of what's right and wrong?

AB: What's right and wrong.

RM: Your own conscious?

AB: Conscious, conscious. This was very applicable when the drug problem showed up on the scene.

RM: About when was that?

AB: In the early sixties. I was one of the first people who started promoting the fact that alcohol is a drug and a drug that, if misused and abused, will result in alcoholism.

RM: Let's tum the tape over.

AB: Okay.

RM: Alright, we were talking about alcoholism.

AB: Alcoholism. See alcoholism is a disease and it's chronic. It damages the liver and you get a lot of complications from alcoholism. It affects the mental health. It affects the ability to understand the nature of things as they are. You get all kinds of blurred concepts as far as what to do and what not to do. Of course, now I think that some people will use alcohol as a crutch and as an excuse to fall back on; like going back to the fact that the husband is an alcoholic and he comes home out of the clear, blue sky and picks a fight. You call the authorities and you have him arrested and a restraining order, but then he comes back with his excuse, "Well, honey I'm so sorry." Oh, he can be the most pious person in the world. "Well, what was wrong with you. I hadn't done anything." "Oh, I had been drinking and I really didn't know what I was doing." That's the biggest bluff in the world, where people hide behind two or three drinks of alcohol. Now, the time that he beats up on you for falsely accusing you of something you hadn't thought about, and when he comes back to apologize, he wasn't drunk at all. If he hadn't been drunk, he wouldn't have been beating up on you, but he had enough for you to smell it on his breath and then you're going to be naive enough to believe his apology. "Yeah, I did smell some on his breath. He was not of himself. He didn't know what he was doing." It might take you four, five, six to ten years to get convinced that this thing is not going to work. I've heard and had enough. That's one of the things that says that I personally have associated with my medical career is in terms of counseling kids to have some manner of self-control, what I call self-discipline. This happened from all the way from high school kids to college kids. Okay, when you leave home and you're out from under the umbrella of mother or father making all of your decisions, you have got to make some decisions yourself. If you register for a course, say in college, and you're your own boss, you're your own director, you don't have to wait for mom to come by and say, "Well, study this lesson in English. Have you gotten your Chemistry lesson now? Have you gotten your Math lesson now? Are you ready for the professor?" I said, "Uh, uh. You've got to have a mechanism that is built in to guide you and to take care of you during those kinds of days." What the overall...my approach was, okay, I'm responsible primarily say for your physical health and knowing the value, learning the value somewhere along the line when mental health became a recognized entity and it being promoted. I have a function as a gatekeeper in medicine to do that, but at the same time to help a kid to save him or herself. Then, I have to envy the ministers primary field to get the total personality developed. That's what I'm trying to say and I think that doctors, well, I know the minority physician, all the way along the line from the Quiglesses, which you've heard me talk about to the Weavers to the Hannibals, to all of the leading pioneers in minority medicine. They were called on in multiple situations to be multiple disciplinary in its approach to developing the whole individual, the whole behavior pattern.

RM: I understand.

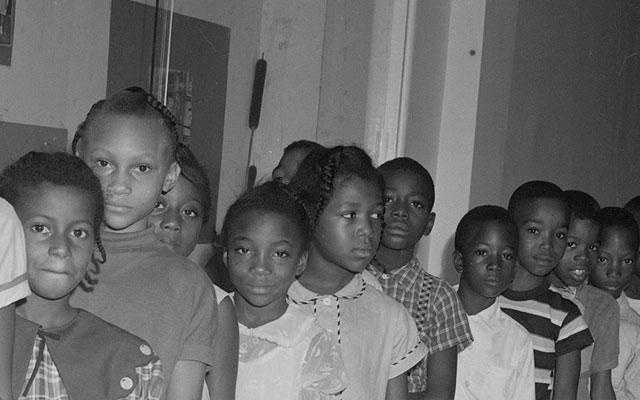

AB: Now, recognizing that in our society, the great institutions would be to start at the home in terms of influencing the behavior of the child. Then, you go from home to school, whether it is a private academy or whether it be a regular public school. And that third block up under which the society stands is the church. It went too long, far too long in the minority community and that's where the black physician has come in to try to help bridge the gap. The minority child because of the nature of the ignorance and the uneducated status of the parents, which is a part that started back at slavery and developed on up through the years. The homes are deficient in the knowledge to understand all of these dynamics of life, living, growth, and development, so the child leaves home and goes to school. The school has been expected to do everything for this child that the home didn't do, plus what the school is equipped to do. Some of these kids get lost out there between what the home has not done and they end up being drop-outs at school. So, the school can't have but so much if the child leaves. Those kids who get into bad behavior of patterns and channels and get sent to jail, you've got a situation, in many instances, that third part of the society-based church never gets that child.

RM: They fall between the cracks.

AB: Yeah. Fall between the cracks to start with.

RM: When was it that you started organizing the council?AB: That was in 1960. You see, when I started teaching...

RM: Let's talk about that. I wanted to step back before we get to when you started teaching, just really briefly. Go back and you mentioned alcoholism, were there other drugs? Did other drugs come on the scene at any particular time that caused significant health problems?

AB: Well, see now those drugs followed and the illicit drug traffic was your marijuana, crack cocaine, and heroin addicts. They followed in a later year. But when I started in February of'57 teaching what I call personal hygiene and preventive medicine they call it, that's contagious diseases, I also was interested in the social problem of illegitimate birth among minorities. The basis for many of those illegitimate births was very simple. They don't know that it is ignorance as to the fact that they go into this and they don't care. The lack of knowledge and the lack of caring, a lack of concern as it were, based on the fact that these kids don't know the consequences and of course, sex education, per say, was a no-no. No no in this school system, but I was able to be a pioneer in getting that in.

RM: So in 1957 ...

AB: Yes. It started in February of '57.

RM: How did that happen? You had this big bee in your bonnet.

AB: Yeah. Well, a news report came out and from the statistical arm of service that showed in Pitt County, it gave the number on that annual report of illegitimate births that...They published those figures from 1956 and in my own way of thinking, it was terrible. Of course, we had begun to learn some things about birth control and this kind of thing. So, I picked up the phone and I called the assistant superintendent of the Greenville City Schools, Ms. Elena Carroll. Ms. Carroll was the assistant to the superintendent, Mr. J. H. Rose, the man for whom J. H. Rose High School was named. Ms. Carroll was always a very kind and thoughtful lady and a person similar to Dr. Malene Irons in personality because you could just sit down and talk to them. I told her I wanted to talk to her and she came out to my office and we sat down and talked just like you and I are talking now. I told her that I was disturbed and she said, "Well, do you have any thoughts or any ideas that you can do?" I said, "Well, I have some thoughts that just maybe some of these things that we might be able to influence, to make a difference here somewhere." I went back to my theme that they don't know, they don't care, and they don't have. Considering the fact that the poverty status of so many of these people who are used to being in poverty, they've never had anything, so they don't know about having enjoyed a thing. They don't know its value and so it affects their behavior. They don't have and they're ignorant, and they don't know. If they don't know and they don't have, then they don't have any reason to care. They don't care. They just accept those things. Anyhow, as an outgrowth to that conversation, I told Ms. Carroll that I would agree to go into the schools and work out a schedule with the principals and she agreed that she would... That's for the city of Greenville. She agreed that this would probably be something that was good. She had so much faith and she said, "Well, I'll let you try. Who's going to do your lecturing?" I said, "I got three people, that's me, myself, and 1." We passed it off as a joke. So, I started going into the schools saying...Every Wednesday, about 2:00, from two to three, I went into the schools. I started out at Epps High School; that's the black school. It's where most of the problem was in the minority community about these illegitimate babies. From that, I was able to develop the program. The following year, I talked to Mr. Conley, who was the superintendent of the county schools. There were two different systems then, city and county. I told Mr. Conley, who was the superintendent, about the pilot project, which I had started with the city schools and I thought that it had been successful. I had used about thirteen weeks and he agreed that he thought it would be good. So, we spread out then to the county schools. In terms of looking forward to try to develop a cadre of people who would have the same message and who would go out and teach, it so happened that ECU along with my alma marta at A&T in Greensboro were able to help. I was able to get Dr. Jenkins, who I had developed a good friendship and relationship with him and Dr. Daughtie who was then the president of A&T State, where we would offer a course. See at that time, the teachers were obligated to have refresher training and they would get a certain number of points for courses taken. So, we got a seminar for teachers approved through A&T. Of course, ECU's partnership in it was Dr. Fuller, who was the counselor over at ECU. He came over, and he and I on Wednesday evenings, say from six until eight-Dr. Fuller would teach the class from six until seven. Then I would take it from seven until eight. He taught pure basic counseling and that's in the early days when the counseling concept was just developing. He gave those teachers the benefit of that and then, I got my little piece in on preventive medicine and illegitimate problem and this kind of thing.

RM: You were teaching public school teachers?

AB: Yeah. Public school teachers and of course, we sent out our little communication and I guess we had twenty teachers who were interested enough to come in and take that seminar. Some of them wanted credit for certificate renewal and this kind of thing and we got that afforded through A&T. So, we were rendering a service, but my intention was to, knowing that it would be physically impossible for me to touch all of the bases that needed to be touched...and I am trying to practice medicine for a living.

RM: You went into the schools then in the beginning just in the afternoon's one-day a week. It seems that that program expanded, too.

AB: Yeah. That program expanded. We developed from the '57, 8, and 9. By the time '60 came along, we had developed to the point that we were thinking big thoughts. We got some of these teachers trained in the seminar, and they would come in and help me in my evening class. So we sent out the word that on the evening class, I always would begin. Sometimes in the latter part of February, every Wednesday night, we would go fourteen weeks and that would put us in there the last week in April, the first week in May. We would culminate that program by having a, what we called a contest, a challenge of wits and knowledge, like the old $64,000 challenge. I don't know whether you are old enough to remember that. The $64,000 challenge where the people bid the contest and would be in a booth and they'd ask the question or make a statement and you accept it. If the statement was correct, you'd say, "Accept." If you thought it was incorrect, you'd challenge. If you'd challenged it, then you'd give the correct answer. The winner would go on from week to week. It ended up being $64,000. That was a whole lot of money back in those days. It was called the $64,000 challenge program and it would come on every week. We patterned our end of our course with what I called a contest of wits and knowledge on the material that they had been exposed to for those fourteen weeks.

RM: Was there a prize at the end?

AB: Oh, yeah. We had scholarships through the various universities. They were getting some federal monies. A&T allowed me about six $600 scholarships, Elizabeth City, about five, and then North Carolina Central, six. I had it all on my list and where all I had to do was one of my evening class students, one of the winners in the contest, had to do to get the student a letter and send it up to A&T and this is one of my scholars. We called them the Joint Council Scholars which we organized that joint council. We had our first public meeting on October 3rd in 1960.

RM: What council?

AB: The North Carolina Joint Council on Health and Citizenship. So we covered all of that part in there where we were dealing with the moral behaviors and alcoholism and all of the other parts for making the total citizen.

RM: At what point did Dr. Irons become involved in the teaching?

AB: Now, Dr. Irons never became involved in the teaching part of the program of the Joint Council. She was a member of the Volunteer Interracial Committee, and she was a pioneer in helping of integration of these various other activities like the lunch counters, public accommodations, especially with the hospital. If it hadn't been for Dr. Malene, I don't know how or when we would have gotten the hospital integrated without some violence. Of course, my association with Dr. Jenkins led me to the point of getting him to agree to integrate the university. Now, the North Carolina Joint Council came in, again these courses I was teaching were what I called "Courses in Correlative Education." That was a name that I coined and we approached it in such a way that we helped those kids from the black schools who really were suffering from not obtaining all of the information that they should have gotten in that segregated pattern. I knew that there was a gap between what the black kids had gotten and what they needed to successfully survive in this integrated school system. So, that was the basis of the council's birth. We organized it so we could be in a position as an organized group to accept scholarship money and to give assistance to those minority kids that we had helped, knew about, and could recommend. So, we did a lot to ease some of the pains of integration. The council bought and published a whole full page ad in the Daily Reflector just prior to the action implementation of the schools being integrated. The title was Our Thing. I don't know whether Doris can find us a copy of that. I think she has one somewhere, Our Thing. We talked about what Our Thing should be, that is our attitude toward the integration process and we picked out what the superintendents' attitude ought to be, what the teachers' attitude ought to be, what the parents' attitudes ought to be, and what the students' attitudes ought to be. We had some positive suggestions for what each attitude ought to be in terms of making this process work and becoming successful. Here in Pitt and surrounding counties, we made a tremendous influence. Now, case in point, in one of our meetings that we were promoting this concept that was expressing Our Thing, one parent said, "Yeah. I done told my children to not take nothing off nobody." Well, you see she was sending the kids out with a chip on the shoulders and we talked about that head on. I said, "No, no, no. That's going to get your child into trouble. If he goes out with a chip on his shoulder, and somebody says, well good morning, then your child with a chip on the shoulder looks around and says, what the hell is good about it. You are starting something. You are starting a fire that you can't put out." We worked hard. Fundamentally this group of teachers that were working here in Pitt County had been in the seminar. Now there were more from the surrounding counties; Beaufort and Craven and all, but my core group was six or eight teachers from right here in Pitt County, where I could see them every week and work with them. People from that group went out and went into the communities, PTAs, and places to influence the process of integration. We had some problems, in general, with the significant beneficial influence to the work that we were doing. Now, one other thing that the Joint Council did that's on health and citizenship was initiated as a kick-off on October 3rd, the time that we had our charter and all of that kind of stuff was 1960. Dr. Samuel Proctor, who was President of the Peace Corps, was a very able person, very articulate. Dr. Proctor died about two years ago. But any rate, he was a personal friend, and he came and kicked off that particular meeting we had in the gym over here in Epps. That meeting on that October Sunday was the first time in the city of Greenville that whites and blacks met together in an integrated situation. Now, prior to that if a public meeting was going to be held, if it were controlled or promoted by blacks, the news would go out, "Special section reserved for whites." If the white people were promoting and in control of programming, ..Special section reserved for colored." That's the only time you got a public meeting, but for the first time...

RM: Tell us that date again.

AB: That was October 3, 1960.

RM: Epps High School?

AB: Epps High School. Now, Superintendent Rose didn't think much-he had some questions about the idea. He didn't know whether people would come out on a Sunday afternoon or not. We had it at 3:00 in the afternoon. We picked 3:00 as an hour that it didn't interfere with their morning church services and we would be out in time for those who had evening church services and they would go back to church. We had Epps gym totally crammed. We had about 2,100 people...

RM: A huge crowd.

AB: ...in that gym and Mr. Rose was just so flabbergasted, he was right uneasy. Of course, Dr. Jenkins was there. Dr. Jenkins was on the program. Both Dr. Jenkins and Dr. Procter were wonderful speakers. Oh, they had Command of the King's English, and the way they could do it and put it out. So, that was a success. Well, the first anniversary, it was every October we would have this public meeting. 1963, that's before the Civil Rights Act, was the year of our crowning achievement. Minges Coliseum and the stadium had just opened up and were expanded, and in the first time in the history of the whole county, they estimated about 10,000 people out there in Ficklen Stadium. It was all programmed and controlled by people in the Joint Council, in which I happened to be the President and I was in control. The guest speaker was Anthony J. Sallabreezy, who was the Secretary in the Kennedy Cabinet. They changed the name of the secretary a little bit. He had health and...

RM: His department.

AB: Yeah, his department.

RM: Not health education and welfare, but...

AB: Yeah, HEW. Health, education, and welfare. As Sallabreezy came down, the late Congressman Bonner, who was our congressman...Now Congressman Bonner had grown up, of course he was sent to Congress a few many years ago, and the segregated thing, but Congressman Bonner was a very astute politician as he began to realize the power of the black vote. He began to transform his approach and one of his approaches; he made friends with Andrew Best. Every time that he came home, he'd come by to see me and say, "Well, I just wanted to holler at you and stay in touch." He facilitated getting Anthony Sallabreezy here in Greenville. We promoted it and we had the Governor Terry Sanford. Everybody in the political hierarchy who was somebody, the various senators from the state. We had the guy from down here in Bertie County, anyway. We had senators from throughout the state, people from Chapel Hill, people from Durham, people who...Those 10,000 people gathered in Greenville and the whole audience that you could see was black and white dispersed all around.

RM: Checkerboard.

AB: Yeah, checkerboard. That was beautiful thing to me because it was really, no worry about integration. We put those people out there, and everybody came. Everybody enjoyed it and the program was scheduled for one hour. Governor Sanford came over to where I was because people started gathering around 2 or 2:15. Governor Sanford came over and said, "Andrew." I said, "Yes sir." He said, "Do you think we're going to get these folk out of here in time? They flew the secretary on a navy plane into Kinston and they bought him over in a car." I said, "Oh, yes. Oh, yes." Because we were set for one hour. I did my famous speech, "Why are we here?" We are here to demonstrate and so forth and so on. So, I timed my remarks to five minutes after the invocation by Reverend Blake. Everything was scheduled and the governor presented Mr. Sallabreezy, the secretary. I don't know whether he or Congressman Bonner, one of them presented him. Anyway, he spoke and three minutes to four. Reverend Blake was saying the benediction.

RM: You did it.

AB: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. We pulled it off and of course, Governor Sanford was just elated. That followed up some of the things that he was doing. He established the Good Neighbor Council by Executive Order and this kind of thing. But, all of those things came together that is to promote the atmosphere of total integration and no more of this reserved section for whites or reserved for colored and all this kind of thing within the county. So in my memoirs, I would be derelict in my duty in responsibility if I did not showcase the total beneficial affect that the Joint Council had played very quietly with no fan fare in this total process of integration. In other words, we made believers out of a lot of them people out there who were waiting, worrying, and wondering.

RM: Well, Dr. Best thank-you so much. You obviously worked very conscientiously and unrelentingly on Civil Rights issues and Human Relations issues throughout your career and we appreciate that.

AB: It all goes back to promoting and trying to look after the health. That's the total health of each individual. It's all right for me to treat your pneumonia, but if I forget your mental state, it's because you have been abused, because you are abused, or permit yourself to be abused from any drug or alcohol or whatever it may be. In other words, if you're screwed up in your thinking, I have not really done my job of administering to your needs.

RM: Well that's a mighty big responsibility you take on for yourself.

AB: That's right.

RM: Let's take up there next time.

AB: Okay. All right.

RM: Thank-you.

AB: I think this has been a very good expression and a very good recording, or a discussion of some of the tangential things that go around into...but it belongs and very certainly a part of the total picture.

RM: It surely does. Thank you.

AB: You're quite welcome. Thank you.