[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH DR. ANDREW BEST February 17, 1999 Interviewer: Ruth Moskop Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn 18 Total Pages Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

AB: Good morning.

RM: It's February 17, 1999 and I'm here to interview Dr. Best at his office in Greenville, North Carolina. Do I have your permission to record the interview, Dr. Best?

AB: Yes. You surely do.

RM: Thank-you.

AB: Okay.

RM: We left off last time, talking about your return to eastern North Carolina to practice medicine.

AB: Yes.

RM: And you told us how you had had a mentor who had encouraged you to come back; several in fact, encouraged you to come back.

AB: Yes. As I was getting ready to leave the service in December of 1953, I looked around at several eastern North Carolina cities for a possible location to open my practice. My hometown, as you know is Kinston, and of course, over here in Greenville, I found out that one of the minority physicians who was practicing here, the late Dr. Battle, had had a heart attack and died a month or two before I was ready to come in. The younger doctor, Dr. Harold Kelly had been drafted to do some time in the service. So that, so far as the minority physicians were concerned, kind of left this city wide open. Of course, I looked at some other places, Ahoskie and New Bern. To fit my criteria for starting practice things had to be just right. One, I wanted to be near enough to my hometown or my home community near Kinston so I could be of some assistance and look after the welfare of my mother, who was living there. The second criterion was to have hospital privileges. At that time, in those days of segregation, the hospital in my hometown of Kinston, which was owned by a group of private doctors, did not have an open staff for minorities. Their staff was closed to minorities and had not been opened at all and the minority doctors who were there were not on staff. If they had a patient go into the hospital, they had to refer this patient to one of the white physicians over in Kinston. So, to me, as a young doctor coming out and going into practice, that was a no-no. (2:34)

RM: Let me interrupt you just a second.

AB: Yeah. Sure.

RM: What did that mean to refer the patient to a white physician? Did the black physician completely give up the care giving?

AB: I heard this many times from my mentor, who was the late Dr. Joseph P. Harrison and the other minority physician who was in Kinston, Dr. John Hannibal. When they referred the patient for admission to the hospital, the white, admitting physician was totally responsible for all of the care. Now, Dr. Harrison or Dr. Hannibal could visit like any other visitor. In some instances, the physician to whom they had referred the patient may ask, "Well, if you got any comments, let me know or if you have any suggestions for treatment." But they had to always go through the white physician. They couldn't participate in the care or writing orders or anything official. The amount of the involvement they had in managing their patients actually boiled down to the personality of the physician to whom they referred the patient. So, to me, this was a no-no. The sister of my brother's wife worked with Mr. Hopkins. By that, he knew that here was a young doctor who was coming out of the Army. So he used his good influences to persuade me to come to Greenville. (4:35)

RM: Now, who was Mr. Hopkins?

AB: Mr. Hopkins was a local... Nelson Hopkins was a local community leader. He was very widely known and respected. He was really in the culinary business, because he catered for the Rotary Club and the different organizations in the community. He was very widely known for his culinary expertise. Of course, he knew the judges and the lawyers and everybody who was in a position of power and he had a lot of respect in the community and a lot of influence, too. I often remarked when I got to know him well and I'd always tell him, "Well, if I got into trouble and had to have somebody to help me, I think I'd rather have you than any lawyer in town." We, good naturedly, would laugh that one off. Now, another thing that Mr. Hopkins did, he said, "Well now, if you'll come to Greenville, we will try and find you a place for an office, and I'll give you the first six months rent free." (5:54)

RM: How wonderful

AB: So, that worked out, and he owned a lot of property. He had an apartment house, which was vacant, and we looked at that particular building. I said, "Well, okay, for a temporary thing, I can manage in getting my practice started. I don't expect to stay here forever." You know, it was a little too small, but in the initial phase of the practice I thought it was adequate. It turned out to be. To his word, the first six months that I was in practice, he refused to take any rent. Afterward, instead of collecting his rent monthly, in the fall (November, December) as I got ready to pay him, I would just go ahead and give him a check for the whole time. After that first six months, I paid him more or less on an annual basis, not on a monthly basis. All of those things were very good for me in getting started for my practice in Greenville. Now, as a little background, all of the other doctor offices in Greenville, to my knowledge, were segregated. We had white physicians who would have a so-called colored waiting room. I never went to one myself, but I'm told that the minority patients had to sit crowded in their little side of the waiting room and in some instances, if they didn't have a large waiting room, they would sit in chairs rolled up in a hall. Usually, that little hall led to the laboratory where you could have all the fecal and the urinary odors for the black folk. They had to sit there and wait until he finished with his white patients and then he would see them. This is the story that they told me. (8:02)

RM: So, they couldn't make appointments, they just had to wait.

AB: Yeah. Most of the doctors were seeing-that is the family practitioners. They had an open-door policy: first come, first serve. They had to wait until...My imagination is that if somebody was very sick like having a lot of chest pain, heart attack, that they would go ahead and be seen and sent on over to the emergency room or made medical disposition. If I, as a black patient, went in for a check-up or something that was routine, I was expected to wait until all of the white people were seen. Of course, when I opened my doors, I kind of passed the word along that I was opened to treat people and patients, and from the first few days of my practice, I had white patients, too. This was all in one...Even though the waiting room was small, everybody used that same waiting. It didn't make any difference. I didn't have any for whites only. That was the background scenario and then when I came on the block, there was a dentist in Greenville, the late Dr. C. R. Graves, who was a very good technician. He also had a big practice, in which there was just one waiting room for everybody. Of course, I'm sure that that had some good impact, because after I had been around...After the forces of integration were affected-we integrated in the early 60's. By that time we, the interracial committee, had gotten these people to desegregate. Then my understanding is that the other doctors, in their offices, started desegregation. I'm not totally sure, but I'm thinking that office desegregation came after Dr. Malene Irons and I got the hospital desegregated. Well, those early years were a little bit turbulent so far as the business of integration or desegregation is concerned. Now the hospital...(10:56)

RM: Well, tell me, before you go on. Can you tell me where that first office was? Where was your first office?

AB: My first private office was on Tyson Street in an apartment building. It was a duplex, where I had one side and there were people living on the other side. It was 613 Tyson Street. That's over here in western Greenville. Now Fourteenth Street has been extended in what was Tyson Street. That has become Fourteenth Street all the way out to Fifth Street or Martin Luther King Drive. Let me pause for just a moment.

RM: Surely. So, you set up on Tyson Street. Let's see, you had half of a duplex, so how many rooms did that give you? (11:43)

AB: Well, one of the rooms was a waiting room. The second room was an examination and treatment room, and then I had a little space in the back for a little kitchenette and a little dinette that was more or less a utility for me. At the time, I lived there. I had a little cot about 18 inches wide. I lived there for the time being and of course, later on when I got a chance in 1957, I bought a house. I moved to 1208 West Fourth Street, where I still live. It was a large, spacious two-story house, and I renovated and fixed it up before I lived in it. Of course, so far as practice was concerned, there was a Dr. Thompson, who carne to Greenville in about '55 or a little after-sometime after I carne-he had an office on Cadillac Street. He took two duplexes and knocked the wall out, so it was all in one. It was his clinic. He had some rooms that he could admit patients for short term stays. Of course, when he came to Greenville, he was under contract. He was expected to be called to the service, and he was called and assigned overseas. As he left, he and I had an agreement that I would take over the building or the clinic. (13:46)

RM: The space.

AB: The space and then I moved there in, probably in '57.

RM: Where was that building located?

AB: That building was 416 Cadillac Street. Actually, it was 414-416 Cadillac, but the duplex was 414. That was 414 A and B Cadillac. We had knocked out the middle wall and all of it was in one place. I stayed there on Cadillac until I moved here in this building in 1968.

RM: I see.

AB: Yeah. So, I had roughly about a ten-year soldiering on Cadillac Street and it was a pretty good experience in that...Now at that time, I did all my deliveries at that building, which we called the clinic. We had to have 24-hour coverage. I did all of my deliveries there except any problem delivery case or pregnancy. I would send them on to the hospital. I still saw the patients in the hospital, but I had ready consultation, and we had equipment there ...(15:20)

RM: Surely.

AB: ...if it was a problem pregnancy. Then when I got the chance to get this place, I came in and I renovated it for office work. Now this wall that you see here...See all of this space was a den and there was a bedroom back there, but I put this wall in here to cut off to give me some privacy...

RM: A private office.

AB: A private office and then all of that living room up front, we turned it into the waiting room. The counter that you see up front, I designed it. My cabinet maker and I built that counter. It's sitting right on the floor, just like another piece of furniture. At anytime, if you want to tum it back into a residence, all we have to do is go and unhook where that counter is hooked together and move it out like it was another piece of furniture. In two or three hours, you have the whole place turned back into a residence.(16:30)

RM: You kept it versatile.

AB: Yeah. Versatile. That's a run-down of the scenario for my private practice.

RM: It sounds like you delivered quite a few babies, in the early days.

AB: Yeah. In the early days, I delivered quite a few babies in my old obstetrical practice.

RM: What other kinds of patients did you see?

AB: Well, in the general medical patients, the pneumonias, the arthritides, the high blood pressures, and the colds and flus, and all of this kind of thing. Gastroileitis, yeah.(17:07)

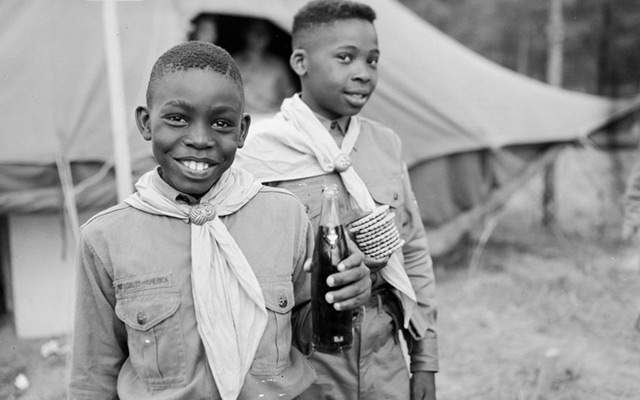

RM: Did you see children?

AB: Yeah. I saw children at that time. My pediatric practice was still very, very viable and my statement was that, "I see them. I treat them from the cradle to the grave." Usually, those babies I delivered became my pediatric patients as they developed. So, that gives you a kind of background of the practice.

RM: I know there are a number of other black physicians who have been here some time: Dr. Artis and Dr. Land...(17:50)

AB: Dr. Artis, Dr. Land...l practiced medicine here in Greenville; it was about 26 years I had been here before Dr. Land showed up. Dr. Land showed and opened up his practice in Internal Medicine. Several years, maybe four or five years, then Dr. Artis came. That put three of us...Later on, Dr. Trent came in to practice. Maybe they had gotten a little worried with me about something. A lot said that Dr. Land was going to run me out of business. Dr. Land and I both laughed because we knew there was enough work here for all of us. Dr. Artis finally joined us and that has been a real good experience. There was a white physician here, Family Practice Dr. Herbert Hadler. Dr. Hadler was always very cooperative. He covered for me. I covered for him. But with some of the other physicians, it appeared to me that-well, if I asked for coverage sometime, when I was going to have to be gone to a meeting or somewhere, a medical meeting, they would say they would cover, but I couldn't reciprocate, meaning that their white patients would reject my covering them. But now, I think that represented the prejudicial view of the man, because I never had any problems covering Dr. Hadler's white patients. Whenever he was going to be gone, he would say, "Dr. Best, my counterpart, is going to look out for you." In my practice, I was seeing white and black patients all the time. So, that kind of put a damper on my coverage and suffering through 26 years of isolated practice, where I had to pick my coverage if Dr. Hadler couldn't cover. Of course, Dr. Hadler, after both of us stop doing OB, if I was going to be out of town, I had to get somebody to cover my medical practice, and then would have to get somebody to cover my OBs. Finally, when Dr. Clement, Dayton, and Dayton... There were two obstetricians and gynecologists. I could use them as consultants for any problem cases that I had. Eventually, we worked out a deal that they would cover me for my obstetrics. Of course, if it was a patient that I had done prenatal care, they would not. They did not agree to bill the patient. If it was my patient and they delivered, they'd bill me for half my delivery price. For example, at that particular time in my billing system, I got $75 per delivery. Of course, that's skyrocketed from that now. So, if they delivered a baby for me in my absence, they'd send me a bill for $37.50. Whether I ever collected or not was not their concern, but I agreed to that. That gave me some relief so far as being away and being out is concerned. So, that kind of gives you an idea of some of the turbulence I went through in trying to practice medicine as a lone minority practitioner.(22:35)

RM: It was relentless responsibility.

AB: I never could really be gone. I was on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 30 days out of the month, except the months where there were 31 days and 31 days a month.

RM: You mentioned collecting the bills. Was that an issue for you? Was that a problem sometimes? It must have been.

AB: Well...

RM: Did you accept alternative payments?

AB: Well, now are you talking for OB, for the obstetrics?

RM: In general.

AB: In general. No. Now, in my basic coverage...Let me go back to me and Dr. Hadler. Our coverage of the patients was courtesy. If he covered the patient for me, that patient was... He'd say, "You pay Dr. Best." If I covered a patient for him, "Pay Dr. Hadler." So, it was professional and courtesy on both sides. Of course, it was only in the cases of Dr. Clement and Dayton doing deliveries for me, where their fee was half of my usual customary charges and they looked to me to pay them that fee.(23:56)

RM: I meant, in terms of with relationship with the patients, with your own patients. Did they ever come to you and say, "Well, we can't afford to pay, but we need your help." Or they'd get your help and then tell you, they couldn't afford to pay.

AB: Well, my practice always carried a very, very heavy burden of poor people who could not pay. But, I never said no to a patient, whether they had the money, whether they had no money, whether they had part of the money, I never said no. Of course, many people who could have paid, took my goodness to be a weakness and took advantage of it. See, I knew it, but I never complained about it. (24:54)

RM: Have you had help within your office? Have you had office...? How should I say it? Have you had a secretary around? Have you had nurses working with you?

AB: Yes. Well, throughout the whole time...See, at one time of my practice, I'd have as many as three to four staff people, like a nurse, a secretary. In most cases, I'd have one assistant, Doris. Well, Doris is my so-called "Girl Friday." She is multi-talented and she is a utility person. Wherever I need, if it's secretary, if it's computer, if it's on the nursing side, wherever I need her to be or to go, she has enough talents and enough ability to serve the purpose. So, it's mainly the two of us. Now, sometimes we have to have somebody come in for some special reason or for some special purpose and we get somebody for that. We handle our business in that fashion now. (26:18)

RM: Doris is a wonderful person. It's wonderful that you have her here. Now, this hospital, the hospital privileges that drew you to Greenville, what kind of hospital was this? Where was it? Which hospital was it?

AB: The county office building sitting right across the street over there was the old hospital building.

RM: So, you didn't...Let's see, I guess the hospital on Fourth and Johnston was closed.

AB: Yeah. It was closed by the time that I got here.

RM: All right.

AB: That was closed. It was the hospital that's right out here, right across Fifth Street. Of course, after I got here on the staff, they built that south wing. It was enlarged and renovated. When I applied, I got staff privileges. Now this staff in this hospital had been opened from the time and days of Dr. Battle and Dr. Kelley, my forerunners. I am told that the hospital, having being built with the assistance of federal assistance from the Hillburton Funds was open to minorities-that was the basis upon which they had membership on the staff. With the staff at the Lenoir Hospital in Kinston being closed, it was an open invitation for me to come to Greenville where hospital privileges would be available. Still for years, I was the sole minority member of the staff. At that time, the staff was roughly 36-40 physicians and specialists. Of course, at the advent of the medical school coming here and this affiliation agreement that Pitt Hospital would become the University Hospital or the hospital for the medical school, things began to pop. The expansions took place, ballooning out...If you go away on vacation and stay two weeks and come back, there would be something else growing up in one of those fields over there. (29:03)

RM: Mushrooms.

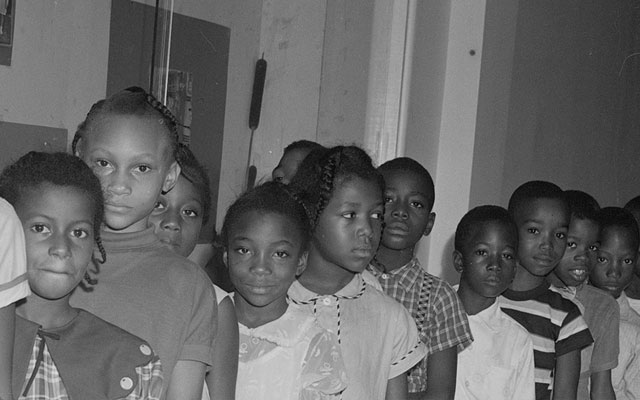

AB: Mushrooms. That's exactly correct. So, from that lowly beginning, we see where we are now. Go back to the condition at the hospital before the days of desegregation. Even though I had my privileges, there were some people on the staff who were a little bit reluctant for any good casual relationship. There were others who were very warm and helpful; Dr. Irons, Dr. Hadley, Dr. Trevathan, who was a pediatrician. There were only a few who were standoffish. Now, Dr. Ray Minges, who's the Pepsi-Cola Minges family, was a very large advocate of service. He had money from Pepsi-Cola, and he truly practiced surgery for the love of surgery. He never refused a patient and in many cases, he did surgery on a patient and didn't get any more compensation than you did or I did. That was Ray Minges for you. He was always very strong in my comer for being a lone physician and being a minority. So, I didn't have any discrimination, any overt or open discrimination with the staff or the core nexus of the support people. Now, the minority people were all crammed up on the east wing of the first floor. If you were a newborn baby, if you had pneumonia, if you were black, you were on the first floor, all crowded up together. One of the precipitating factors was the fact that they had a newborn nursery and at the time when they developed the isoi It was used in the newborn nursery for those premature babies. It was of some concern to Dr. Malene that her min rit.i babies couldn't go to the newborn nursery where they'd have use of the isolftl#. You know, respiratory conditions and this kind of thing. So, that got Dr. Malene upset and I was concerned that the hospital was segregated. Now staff, orderlies and nurses and nurse's assistants, they might be working together on the floor, but when it would come lunch time, when they went downstairs to eat, there was one dining room for colored and one dining room for white only. We working side by side, you and I, black and white, but when we got to go different directions to eat, those things bothered me. Phone rings and Dr. Best answered. The...Where was I? (33:15)

RM: You were telling me about the separate break rooms.

AB: Yeah. Yeah. For lunchroom. Okay. And that bothered me. So, Dr. Malene was concerned about the problem with her minority babies not being permitted to go into the newborn nursery. So, in the conversation between the two of us, we decided that we were going make a request of the staff that they would go ahead and desegregate the hospital. So, we developed a strategy as to how we were going to do it. Number one, we would try to get an audience...We usually would have a staff meeting every Saturday morning. I asked for privilege for some time at one of the Saturday morning staff meetings to present a problem. The chief of staff agreed to program some time in and to present a problem that concerned me and Dr. Malene. So, I made my pitch to the staff that the hospital in its present form of segregation is headed for trouble down the road. I used the fact that the this is in the early 60's now-Civil Rights activities were going on across the face of the nation and it was lot of activity that had become violent. Every time you picked up the paper, some violence had erupted in some city, somewhere across the face of the country. It was more prevalent in Alabama and Mississippi. It was really a focus on Alabama where Dr. Martin Luther King was the leader of the band down there. My plea was, in a very quiet, sincere, concerned tone, that integration or desegregation was coming, and we should do it ourselves voluntarily where we can use our own road map. We can use our own blueprint to get the job done. So, the chief of staff asked me if I had any recommendations. I said, "Yes sir, I do." "What are your recommendations?" "In the first place," I said, "With the crowded conditions on the first floor in the east wing. All of the minority people are down there, no matter what the disease process they have. It's intolerable. My recommendation is that our admissions policy be changed where we will admit patients on the basis of their disease process. If a person has an infectious disease, whether he is black or white, they are sent to the section where there are infectious diseases. If they're going to surgery, they go to the surgical floor and on down the line. If it's pediatrics, be he black or white, they go to the pediatrics floor." So, admitting patients on the basis of their disease process. The second thing that there was a concern about was the segregated eating facilities and staff things. My recommendation there was just to simply take down the signs and pass the word that people could sit in which ever dining room they wished. That would lead it up to if you and I were working together on the floor, if we went to lunch, we could sit down and eat together. Then I attacked the practice of titles. Every white person, even a little eight year old girl would have "little Ms. Susie Jones." If it was a little boy, "Master John Brown." (38:02)

RM: Written in the chart.

AB: Yeah. On the chart, just the title. With the adult white people, Mrs. Ruth Moskop and if your husband, would be Mr. So and So Moskop or Doctor or whatever his title was. But with the blacks, there were only two classes of people who could get titles. If I were a minister, it was Reverend Andrew Best, or if I were a doctor, like a dental where it would be doctor of dental or medical, be Doctor So and So. My recommendation for that...

RM: Everybody else just had first name and last name.(38:55)

AB: Yeah. Yeah. No titles. Everybody else in the black, no titles. So, my recommendation for that was to title everybody or title nobody. They saw where it would economically feasible and smart to title nobody. I said, "Okay, that's alright with me." So, those recommendations were not totally surprising, but should I say pleasantly surprising, when the staff voted to go ahead and desegregate.

RM: Wonderful. Do you remember what year that happened?

AB: That was in the early 60's. I can't pinpoint exactly when. I might could do a little research and find out exactly when. That was in the early 60's before the Civil Rights Act came aboard. My constant plea was that desegregation is coming just as surely as the night follows the day. Let us do so by evolution. That's our own pace and our own blueprint. War will be unto us if we force it by our neglect, that we force it to come by revolution. Revolution implied it's going to come with violence, and violence is what we didn't need. Because, when you get through being violent, the same problem is still there and you got to pick up, not only the pieces of the problem, but the havoc of the violence. So, it bought that. Now, the strong support for the position that I took came from people like Dr. Ray Minges, who because of his money and community standing had a strong voice. Now, before this passage or desegregation, for better than 26 years, I was never asked to be on call for the staff. They never asked me. It's kind of funny that I was here at the office and I got a call from one of the doctors who was chief of staff. He said, "Andrew." I said, "Yes." He said, "What would be your reaction to taking your tum, you know, on the staff coverage?" You see, we had two ways of doing it. We had a weekly schedule and then we had a weekend schedule. Now, the doctor who was on call...How far are we? Are we still recording? (42:15)

RM: Yes. Side 2 Begins

AB: The doctor who was on call...The responsibility was to sleep in the hospital, to be available to take care of the emergency room or whatever the necessity was. The first line for a doctor to be on site, to give direction for whatever emergency that would come across.

RM: This was before we had interns, residents, or any of those.

AB: Yeah. This was before we had the interns or the residents as emergency room coverage. This was just primarily the staff. So, it represented with the number of doctors on staff. It was about once a month that they called. You'd have to rotate for that week they'd call. About once every three months, you'd be on the weekend call, which would take care- You'd have to be in there on Saturday night and Sunday night a weekend. Well, having been the advocate for all of these other changes, I would have felt foolish to have rejected taking my fair tum. I'm agreeing that those doors ought to be open, so I've got to take the consequences of the opening doors. So, I said yes. I took my call. Whenever I was supposed to be there, I was there. The only incident that I had in the emergency room, well, the major one, on a Sunday night, the emergency room called me and said, "Dr. Best, we have a patient in." So, I went on to the emergency room, and there was a young white female, I guess twenty years old, who had been injured in an automobile accident. So, when I showed up on the scene, she looked and told the nurse, said, "I want a doctor." The nurse said, "Well, Dr. Best is on call tonight and he's the doctor." "I want somebody of my color." No, she didn't say "I wanted somebody of my color." She said, "I want somebody the color of your coat." (2:54)

RM: The color of your coat?

AB: The nurse had on a white uniform. The nurse told her, she said, "Well, I'm sorry, but Dr. Best is on call tonight and he's the one that's gotta be responsible." As luck would have it Dr. Minges walked in, who at that time was Chief of Staff. I told the nurse to discuss this problem with the Dr. Minges. She did and Dr. Minges frowned his face up and said, "Oh, no." He just walked right up there to the young lady and said, "Young lady, let me tell you something. In this hospital. .." At that minute, he pointed at me. "That is the man on call tonight and nobody does anything in this hospital unless he says so. He is the hospital rep on call. Now, I'm Dr. Minges and I'm the Chief of Staff, but I have to carry out his orders tonight because he's in charge in this facility at this time. Now, you make up your mind." It so happened that the young lady was from over somewhere near Kinston, Lenoir County. He said, "I don't know how you all handle these situations over there in Kinston, but we don't have that mess over here." So, she kind of mused about it a while. Of course, it was cuts and abrasives and superficial. So, she said, "Well, I'll just go to Kinston or somewhere." Dr. Minges said, "Well, joy go with you. Peace behind you, but it'll never happen here." That was a message to everybody. Everybody who was in the emergency room had their ears perked up. Even though they could be standing over aside somewhere, they were listening in on exactly what Dr. Minges was saying. That went on off. The only other incident that I had...Let me back up a minute. Notice the reluctance before the days that we got this integration or desegregation agreement, the assumption was that there would be a number of white people who would reject my services because I'm minority. This was the justification for not putting me on the rotation. I thought it was foolish all the while, but I finally said, "Well, now if by my not being on rotation, that means more rest for me."

RM: That's right. (6:23)

AB: So, I didn't let that bother me. Strangely enough, in the absence of that incident from Kinston and one other incident, which was not as bad of a young white female who came in on a Sunday night from...She lived over in the Fountain area, Pinetops/Fountain area and she came in. Her mother gave the history to the nurses that this young lady had eaten a hot dog and it was causing her to have some abdominal pain and she was having indigestion from it. The hot dog had upset her system. When I walked in to the room, she was in labor and she was crowning. So, we went on and finished up with the delivery and took care of the baby, cut the cord and all of this kind of stuff. It so happened that she had a very minor tear, because the baby's head came down, from the baby's head coming through. So, I looked at it and it so happened that Dr. Clement, one of my consultants, OBGYN, was in the house. He had done the delivery. I said, "Ed, I need your opinion on something. Here is a young lady who came in in labor." I laughed. I said, "Her mother said she ate a hot dog this afternoon, but that was a mighty powerful hot dog." He laughed, and he went in and he took a look. He said, "Well, Andy. I tell you. You could take a couple of sutures in there, or you could leave it alone." I said, "Well, Ed, since you're down here, why don't you just go ahead and take a couple of sutures in and be sure that she gets a good healing." So, he said, "Alright, okay." So, he went on and took a couple of sutures. Well, I did that to actually avoid any possibility of any criticism following. See, that was what I called preventive criticism and but, absent those two incidences, everything went just as smooth as the Neuse River in the springtime. Some of the predicted, horrible reactions never took place. I am told that now the doctor's offices are all open. The emergency room at the hospital is now open, and they have very efficient emergency room staff. After getting the program where we brought residents and people here as a teaching hospital, that relieves the pressure on us private practitioners. In other words, the face of the whole health care delivery system has been changed, changed for the better and for good. Now, that story within itself, to me, represents a very significant change in the attitudes and the face of hospital practice or community service. Now, the final part of this integration story happened. See now, we had gotten public accommodation, and of course, we had gone through school desegregation and I had a lot of things to do with softening up that, which I will talk about that later. But East Carolina still had not desegregated, actually. It didn't have anybody in the undergrad courses as a minority. So, I went in and talked with Dr. Jenkins. I called Dr. Jenkins, and we knew each other. He had a lot of respect for me, and I had a lot of respect for him. (11:41)

RM: Is this also in the early sixties?

AB: This is in the early sixties. So, I called him one morning and said, "Listen, what is your schedule?" He said, "Oh. About routine." I said, "You and I need to talk about a little something." He said, "What do you want to talk about?" I said, "No. I don't want to talk about it over the telephone." He said, "Okay. I'll be in the office at 9:00." So, it was like on a Wednesday and I went on over and he and I sat down. He said, "What you want? Cup of coffee?" So, he had his secretary fix me a cup of coffee and we sat there and chatted. I opened up by saying, "Leo, State is under court order for integration or desegregation. Chapel Hill is under court order. Why can't we proceed voluntarily, why can't we?" I gave him that story about if we go voluntarily, we can do it our own way. If we... (12:43)

RM: You're getting to be an expert at that.

AB: And if we wait, we will have to do it their way and their way might not be to our liking. So, he said, "Well, Andrew, I have two major concerns." I said, "Okay. I'm all ears." He said, "I would hate to admit a minority student who couldn't cut it." I am using his terminology. "And would flunk out. That would be embarrassing." I said, "Well, okay. On that score, you have heard about this evening class that I have, an enrichment class for high school seniors and I have kids coming to me every Wednesday night from as far west as Goldsboro and from as far east as Elizabeth City, about 350-400 strong. We're doing some things. The main thing is I know the students who can and who can't cut it. The person that I'm going to recommend to desegregate this institution is one that I have great confidence in who can cut it. She is a local girl, lives in the county. I've already talked with her father, who's going to buy her a car so she can commute." I'm getting a little bit ahead of my story. His next concern was that he didn't want James Meredith situation that happened down in Mississippi when they had to call out the National Guard. They had to guard him in his room, two people went with him to class, and everywhere he went. He was the lone black student down there and he had to have two of the National Guards accompany him everywhere. So, he said, "You know, I always, I don't fear unnecessarily, but I'm always concerned about the radicals of the rednecks." I said, "Okay. I've given that some thought, too." So, then I told him, I said, "My recommendation is a girl that lives here in Pitt County. Her father has agreed to buy her a car, so she can live at home and commute. So, there won't be any dormitory situations here. To buttress that up, I have given her a key to my house, where my house can be her home away from home." I didn't add, but I had in the back of my mind, if she gets tired looking at a sea of white faces and wants to get lost and wants to get herself back where she feels comfortable, she can just come around to my house. So, he said, "Well." I said, "If we do it that way, and people get used to seeing a minority face, maybe that will help us change things, bring change about peacefully." He said, "Well, I think it's worth a try." That's what he agreed on. He said, "Well, okay. Tell her to go ahead and apply." He had his secretary give me some application forms and I had this girl, Laura Marie Leary...it's in this statement in there. She applied. She was admitted. She did well and so, the next year around, see the door was open, here came some more. The following and the next three or four years, more and more until athletes starting coming in and playing football, basketball, and then we had what was once a cow path, it was a freeway. (16:46)

RM: You opened the gates.

AB: Yes. Opened the gates and the problem was solved.

RM: Well, Dr. Best, that's a wonderful story and I'm glad you shared it with us. We have just a few more minutes left today and I want to go back to the hospital with all the minority were in the east wing and... Phone rings. Do you need to answer that?

AB: No. No. Go ahead.

RM: You've been here since 1954?

AB: 1954. Yeah.

RM: So, that was what at least six years? Six, seven, eight years before that situation changed?

AB: Changed, right.

RM: Before patients were admitted to Pitt County Memorial on the basis of their diagnosis.

AB: Diagnosis, right. That's correct.

RM: So, was that..? Did the problem become worse over those years? In the beginning, I guess, you just accepted it. Was it a problem early on? Did you have any problem with access to facilities or medications? (17:43)

AB: No. I didn't have any problem with access to facilities or medications. Now, the hang-ups with me actually were the fact that all of these disease processes down there...I thought about it. See, if I delivered a baby in the delivery room, that baby had to come downstairs. It couldn't go to the newborn nursery. It had to come downstairs with the mother. It might be right next door to a person with pneumonia. See, infectious diseases...

RM: Surely. They were in separate room, hopefully, but they were right next to each other.

AB: Right next to each other. Well, in many instances, the rooms were what we call a four-patient suite with only curtains between the patients. Of course, when Dr. Malene could not admit her newborn prematures to where they could get use of the isolate that was another trigger that she was complaining about. See, that kind of threw, I guess, me and Dr. Malene together on the same channel. Now, mind you, before all of this happened, Dr. Malene was on this volunteer interracial committee, which Dick Hardaway and I formed. See, Dr. Ottaway was a young, energetic, Episcopalian minister. He and I both were concerned about racial matters and desegregation and all of this kind of stuff. He told me, "I want to talk to you." So, he came out one day and talked to me in my office on Cadillac Street. We sat down and we both expressed our concerns about discrimination and how people were treated. It was his suggestion that we see if we could have a committee, and that if we accept, we could kind of put the news around or ask people that we thought would be agreeable to participation in these matters. So we got ten black volunteers, ten white volunteers, and at that time, Dick Ottaway served as Chair. I was the Vice-Chair. The first, oh maybe, three or four months we met on a monthly schedule, just with no special agenda, just talking about community conditions. Maybe, at any given time, some news article which was obviously an expression or act of disgri tion would be the main focus of the topic for that evening. As Dick Ottaway and I saw it, that first maybe three of four months, was spent getting to know and to have confidence in each other. Originally now, I think I'm astute enough to detect and I know for my own self, the first two or three meetings that we met, I didn't feel free to open up and give them my real, complete personal analysis of a situation. I had to play the waiting game, because I didn't know who was true or who was really concerned about the issue. (22:18)

RM: You didn't know how they're going to respond.

AB: Well, I didn't know who could be trusted.

RM: Surely.

AB: The people learned to know each other. When Dick Ottaway was moved by his church, then I became the Chairperson. After about six months, Dick Hardaway was moved by his church.

RM: Which was his church; Episcopal, which ... ?

AB: Saint Paul's Episcopal Church on Fourth Street. We used the church as a meeting place. Every month, we met at Saint Paul's Church and we continued to meet there. Oh I can't think of the director's name after Dick Ottaway left, but he was very kind. He permitted us to continue meeting there. I'm not sure whether Dr. Malene and Dr. Fred belonged to that church or not. I'm not sure. They may have. Dr. Malene may have. I don't know. Maybe when you interview her, you can find out. (23:17)

RM: I think she's Methodist. I'm pretty sure because her daddy was a Methodist minister.

AB: Well, she may have been. She was evident at Saint Paul's Episcopal Church. Also, well, Dr. Fred, even though he was not one of the volunteers, he always bought Dr. Malene. She was always there. We had other people during these times we were meeting. We'd have other concerned people who were not intrical parts of the official committee, who would come and they were open. We would always conducted our meetings so that those visitors were just as free to talk as the regular members. So, all of that scenario made it very good and productive. I hope in all of that background, that I have answered your question.

RM: So, do I understand correctly that this interracial committee took as an issue the integration of the hospital in a way? (24:28)

AB: Our first thing was to get public...As an interracial committee project, our focus was to get public accommodations...

RM: We call it public houses.

AB: No. We didn't have public housing until later, because housing comes in the part of my, of some...

RM: You mean public accommodations integrated.

AB: Public accommodations integrated. The lunch counters in the dime stores, the restaurants, the lunch counters in the drug stores, the hotel/motel people. When the old Holiday Inn was being built and it was getting ready for occupancy, I took it on myself when I left the office one evening about 2 or 2:30, I went by the building and there was people in there working and there was somebody coming in the office. I spoke and I asked the gentleman if he was the manager or the coming manager over the hotel when they open up. He said, "Well, yes I am." I said, "Well." I told him who I was; "I'm Dr. Andrew Best. I am a community citizen. I was wondering if it would possible when you open this hotel or motel that you could open it up on an integrated basis." He paused for a moment and he said, "Well, over my dead body." Just like that. Just a matter of fact. I said, "Well, I tell you, you better hurry up and die because integration is coming. Whether you like it, it doesn't even matter. It is coming." I said, "So, if you don't hurry up and die, you can't accommodate the fact that integration is here." And, sure enough, as I understand it, I found out later on that this was a guy who had worked in Rocky Mount and he had been designated to manage the opening of this new facility here in Greenville. By the Interracial Committee, we were able, by continuing to work on it, to get people to sign up and agree that on a certain day they would drop the color bar. We accomplished that by what I call constant efforts along the lines of friendly persuasion and convincing people that this is the right thing to do, number one and secondly, it's something that's going to happen whether you agree with it or not. So, you best interest would be to agree with it and to facilitate it. (28:00)

RM: Well, let me try again on the hospital situation here. I guess then, it wasn't until the early 60's that minority the population, including yourself felt that there was enough support, enough to move on with integration.

AB: Yeah. Well...

RM: How did you feel all of those years in the 50's when you had to see your patients together like that?

AB: Well, I felt that I had to deal with a situation. The situation that had been there for 300 years. Here I come along as an advocate of change. I recognized full well that the change was not going to come overnight. I knew that. I was psychologically prepared for that. My attitude was; number one, I know that I'm right and number two, I am prepared to stay with it as long as necessary to get some results. So, with that kind of an attitude of philosophical base, I didn't have any problems dealing with the various, little setbacks that I may suffer or may be rebarked. Okay, I look at the man and say, "Look, why can't we integrate this situation?" Now, he doesn't enter into any kind of discussion or whatever. All he does is looks at me, and says, "Over my dead body." Then I said, "Well, you know, it's coming. It may not come today, but you better hurry up and die if it's going to be over your dead body." Little things, like right down the street there, on this side of Bojangles, there was a restaurant, which, the only thing they had in there was a kind of a lunch counter. They still didn't have any tables. It was a small place. They were right on Memorial Drive. I believe it was called The Needles. That was the only place in town that anybody could go in and sit down on a stool and order whatever you wanted to order, sandwich, cup of coffee. So, in some of our discussions with some of the other people, like the lunch counters, I pointed out that okay, the world hasn't come to an end when people of mixed racial background go into The Needle and sit down and eat. Things like that buttressed my argument or buttressed my plea that this thing is doable. (31:39)

RM: You know, you're making me think of B's Barbecue out here. How long have they been here? B's Barbecue is such a place where everybody goes.

AB: Everybody goes. I don't know when B's...B's been there a long time. I am not sure whether it came in before the desegregation efforts or whether it was there before and then, but it was one of the places. Now, you take Parker's Barbecue. Parker's served everybody. Parker's, to me, has a problem with all of those young men who served who come out to serve the public, the white. Most of the kitchen crew is black. Most of ...

RM: I have noticed that.(32:48)

AB: Most of the kitchen crew is black. Now, I haven't discussed it, but some of the other Civil Rights Advocates have discussed it with the Parker's management and they, down through the years, have not budged. My understanding is that the management at Parker's said, "Well, we're not discriminating, but this is just a policy. We got black and white employees." It's the way that they place the area that they schedule the employees to work. Now, I have been to Parker's, back in running the take-out, we have minorities doing everything from running the cash register, back there to doing everything else. I don't know why the management is just sticking to that "White Only" policy. (34:04)

RM: ''Table Waiting" policy.

AB: "Table Waiting" policy. Now, here again now, all those table waiters are male. See, so there is a male/female discrimination there.

RM: We clearly have a ways to go. Don't we?

AB: Yeah. We have a ways to go. We have a long ways to go, which is, I think I said this last statement here, I said, on page two, "We have come a long way, but we have many more miles to go, therefore, the struggle continues."

RM: It must continue.

AB: Yeah. The struggle must continue.

RM: Well, thank-you Dr. Best.

AB: Well, okay. I appreciate this.

RM: We'll get with again next week.

AB: I think we have covered a lot today. Make a note that when we come back... (35:02)