| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #42 | |

| Gary Pearce | |

| Press Secretary for North Carolina Governor James B. Hunt, Jr. | |

| April 8, 1977 | |

| Interview #1 | |

| {Stephanie Bass of the Governor's press staff also participates} | |

| [Interview by Donald R. Lennon] |

Donald R. Lennon:

If you will, start with a little background on yourself, when you became involved in the campaign and how you got involved with Governor Hunt.

Gary Pearce:

I officially started with the campaign in January of last year. Before that I had been with the News and Observer for about ten years, and I was a political reporter for the last year, covering among other things the lieutenant governor's office. That's where I got to know Jim. I was tired of working on papers and was looking for something else to do. I had given them some indication that I might be interested, that it would be fun to be in the campaign. He contacted me and asked me to be his press secretary, which is the role I had in the campaign and I still have now -- press secretary, speech writer, and just generally involved.

Donald R. Lennon:

You said you were a graduate of N.C. State.

Gary Pearce:

Right, a graduate of N.C. State, native of Raleigh.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you entered the campaign in January of 1976, I'm sure that part of the background strategy had already been laid. What was the situation exactly?

Gary Pearce:

It had been pretty generally laid, and they had started to put in the top people, where they were standing basically. They had already done a poll in November of 1975, by Peter Hart and Associates out of Washington. It was basically an assessment of the mood of the electorate -- what the issues were going to be, what the people were concerned about, how to approach them, who were the key groups we were looking after. That was laid out when I came in. They had already, in a general kind of way, started to move in those areas which are obvious now: crime, education, utility rates. Those were the issues that were seen as how to do it. In the preceding year as lieutenant governor he had already started to do a lot of things like community watch programs, some utilities legislation, and developing the primary reading program. They were moving along that track. It wasn't as if all of a sudden the campaign began and we picked some issues; they had been moving and we filled it out very generally.

One of the first things I remember, about the week before I went to work, was a long talk with Paul Essex and Joe Grimsley, who were his two staff people then, going over the poll and who we were aiming at. I remember very clearly then that the groups we were looking at were the blue collars and blacks, particularly young blacks. Jim Hunt had a strong, positive image, sort of a good government image, but it was clear that what was crucial was extending that beyond the sort of liberal, progressive, moderate types who had always seen Jim Hunt and said, “Well, he's ok, and I had good feelings about him,” to the blue collar person and agricultural blacks, to give them a feeling that he was the kind of candidate who cared about them. That was obviously what was going to have to be done. Looking back on it now, I don't think we realized it quite that broadly then,

that's what was running for Carter. What people were looking for last year was someone to trust, and someone they believed cared about them and could do something about them. Carter came across as a moral, compassionate, concerned person. That's why he was elected. Even though we didn't quite realize it, we got closer and closer to it and were on the right track all along.

Donald R. Lennon:

Governor Hunt, by being lieutenant governor prior to that time, had already pretty much clearly defined his goals, had he not?

Gary Pearce:

You mean as far as running for governor? I don't think there was ever any question about it now. I've never talked to him too much about it, but I've heard indications from places that he considered running for governor in 1972, knowing that he would lose but figuring that he would build a name for himself. There were several other options. He could have run for state treasurer or labor commissioner in 1972. But they had just made the office of lieutenant governor full time, and it was very clear that it was a stepping stone. That's what he had his eye on -- was being governor. I don't know how long it was, but some people say since the sixth grade; and I wouldn't doubt that. In a general kind of way, if people get interested and say, “Governor of North Carolina -- that's how you get things done -- I'd like to do that one day,” I'm absolutely confident that Jim Hunt thought like that and planned like that. That was one of the things we were sensitive about--that Jim Hunt had used the office of lieutenant governor, that he was a politician, and that he was always running for governor. You had to watch against that. You didn't want anybody to get that impression of him, but there's nothing wrong with that. In politics people who do plan ahead do care enough to want to do it.

Donald R. Lennon:

He is the type of intense person that plans well ahead does he not?

Gary Pearce:

Intense isn't the word for him. He's beyond intensity. In the campaign we gave him the nickname of “Mr. Total Initiative.” That's why he's governor at the age of thirty-nine. If he has a minute or an hour, he'll find something to do. Joe Grimsley has known him ever since high school, and I bet Joe will tell you that he has never sat back and just jawed with Jim Hunt. You just don't do it. His work consumes his life. But it's not work, it is his life. Politics which sounds very narrow and partisan, but politics in the broadest sense of it--in doing things in almost a selfless kind of way. Obviously there's some selfishness in it, but I don't think the man wants power for power. I don't think there's any pleasure in that, there's no reward. He has something left over from his parents--a duty kind of thing, a giving to people. That's what motivates him.

Donald R. Lennon:

That's very similar to the Carter image, is it not, of total intensity?

Gary Pearce:

It's similar to it, but I think there's a real difference. Of course, I don't know Carter or exactly what he's like. I sense more of a coldness on Carter's part, a little bit of vengefulness. It's like he lost for governor and [says] “I'm never going to lose for governor again. I'm never going to lose anything else again.” I really think Jim is motivated primarily by compassion for people and an understanding of people's problems. I think the experiences that have molded him most, obviously, are his parents. He had a stable upbringing. There was nothing that scared him in there. I had the impression that there were a couple of things that really affected him a lot. When he was in school, and you can see this from talking to people or reading anything that people have dug up about him, he was the top honcho. He was always top in the class and always class president. He was an athlete in high school. He was on top of the world. Then he got out of high school and came to State and suddenly found himself behind academically, he just had to work himself to death. He had to study and strain and sweat

because he wasn't as well-prepared. That has had real effect on him. He said something about this several times--about when he got to State and found himself behind just because he'd gone to a different school. That taught him something that he had already been taught by his parents: you work hard and that's how you succeed.

After he left college and went to law school, one of the things he never talks about much is that he failed the bar exam the first time he tried it in 1963 or '64. It was one of those years where a lot of people failed it. They go along every year with eleven or twelve percent failure rate, and then one year they pop up to twenty-five percent [because] they changed the test. Well he was one of those. Right after that was when he went to Nepal. I expect that was kind of a lost time of his life. He studied the law books in Nepal. He would get up early in the morning and spend a couple of hours by candlelight or kerosene lamp or whatever going over law books. And again, that just ingrained in him that you have to work, that if you ever let up, you won't catch up.

There was another experience while he was in law school at Carolina that I think had a real effect on him. He tried to get into a law fraternity, not a social fraternity, and was blackballed, apparently because . . . . In 1963/64 segregation was a big issue, and his father had been associated with Kerr Scott and with school integration in Wilson County. He had worked with Terry Sanford, of course. Apparently he was blackballed because of that. I think that hurt him pretty deeply and gave him a sense of what it's like to be on the outs. He will tell you all about Kerr Scott paving the road in front of his family's house and how that got him started; and I'm sure that's part of it. But I feel that those experiences right at the age of eighteen, nineteen and twenty-three, right in the molding, changing period from being a boy to a man, had a tremendous impact on him.

Donald R. Lennon:

Let's get a little background on you, {Stephanie Bass} and then we'll let both of you run together on your impression of the campaign and your participation in it.

Stephanie Bass:

{What do you want to know, where do you want to start?}

Donald R. Lennon:

When you became involved in the campaign, where you came from, and how you got involved in it, just what your role was.

Stephanie Bass:

{I was a reporter. Gary and I had been friends since we worked together covering the legislature--hated the same committee meetings. I spent a lot of time hanging around the campaign office because I had never done much political coverage before, and it was all very interesting to me. I hung around a lot because Gary and a bunch of my other friends were there. I have to confess that I probably was not as objective a reporter as I should have been. During the campaign, I had very strong personal feelings about Jim Hunt and about his opponent, especially in the Primary. I felt like I belonged in the organization even though I wasn't. It was really kind of a relief to me when Gary asked me to come aboard because then I felt I could do away with all this pretense. It's been a real different change for me to make all a sudden because I had never done this kind of work before.}

Donald R. Lennon:

Did you do newspaper reporting?

Stephanie Bass:

{Radio reporting.}

Donald R. Lennon:

When you came into the campaign, in your case, Gary, in January, 1976, they had already made initial surveys and polls. They had begun to formulate the issues. What is your responsibility, what is your duty when you walk in?

Gary Pearce:

It was never real tightly defined which I think this was one of the strengths of the campaign. They never said to me, “Here you are, you are Press Secretary. Your duties for the next eleven months will be to do this, to do this, to do this.” I was given a general

charge, and basically it still is what he gave me the first time we talked. We went out to lunch one day before he hired me and he said, “What I want you to do is to explain to people what I want to do. Just get the message across. If we lose, we want them to at least reject it rationally, to say 'ok we know what you want and we know what you are trying to do, but we don't like it.' ” We didn't think we would lose that way obviously, if we could get across to people precisely what he was going to do. It was never very tightly defined. Soon I fell into speech writing, which I did throughout the campaign. I don't think that was ever intended.

Generally I saw my immediate problem was Jim's . . . not his relations with the Press Corps, because he has good relations with everybody because he works at it. He works at being friendly and nice. But he had sort of an image that we all worried about which was a “goody-goody” type of image, maybe a weakness of being everything to everybody. In some ways that was part of his image with the press. Everybody thought he was just a little bit too good, just a little bit too slick. I can very well remember that the first thing I thought in January was that that had to change. He had to be more real. I had spent just a little bit of time with him. He had stayed one night at our apartment, sleeping on the sofa. As a matter of fact we forgot to turn the heat on, and he just about froze his tail off -- it was about 20 degrees! It became clear that he wasn't quite what he seemed to be because it is consuming for him, and he doesn't let himself relax. There's not a certain time when you sit back and Jim Hunt lets his hair down and puts his feet up on the desk. I saw my job was to make him more of real person. I thought the way to do that did not require manipulation; it simply required contact. People had to see him and had to get to know him and had to get a better sense of him. He had asked me what he should do to get good press relations. My advice was basically “Be accessible.” This generally fit in with

the way he is. A lot of time during the campaign, Joe Grimsley and I had a struggle with this. Joe was the manager, a great manager, but he wanted everything very tightly controlled and tightly managed. His view was that we should win because we had everything going as long as we didn't blow it. He was really concerned about that. The accessibility can break that down. If you are going to be seeing people three or four times a day and talking to them, there's more chance for error just logically. That was the first thing we started to do, and it was my first contribution to the whole process.

There was a strategy meeting on January 15. It was the first time I had met Burt Bennett. There was Burt, Paul, Joe Grimsley, Jim, and me. I think Weldon Denny was there. David Sawyer, our tv producer, and Peter Hart were both there. We mapped out what we were going to do throughout January, February, March, April, and May. The first stage of it, up until April which we had tentatively set as our announcement time, was, to be blunt about it, was to use the office of lieutenant governor. Much of what I did was predicated on a belief that David Sawyer had in advising us on how to use television. Even though he was going to do our television commercials which obviously weren't going to start until two or three months before the primary. . . . We brought him in very early and his advice was that commercials serve only to remind people what they had seen on the free media -- television, radio, and newspaper. You have to build a foundation. That makes it a lot easier later on. You have a crime commercial, something clicks and people will say, “Yeah, I saw Jim Hunt doing something about crime.” They tend to remember, and the lines between a paid commercial and news clip tend to become blurred. That was basically what I tried to do for about six months. At that time we didn't have a lot of press conferences. As he traveled around the state some, we did. We tried to stay in Raleigh and took lieutenant gubernatorial. It was basically the same thing as Ford

running from the Oval Office. We tried to do things and to talk about things and makes speeches that were precisely what our issues were going to be -- on utilities, on crime, on education. We were laying the groundwork then, over and over. Sometime in either February, March, or April we added another issue -- economic development. It was basically added, I think, because of Ed O'Herron. The first times that they tested, the only candidates were Jim Hunt and Skipper Bowles. They had gone under the assumption that Skipper would run again. Naturally he ran strong because he had reservoir of support. This is funny, you look back on it and you forget so many things. But I remember that in January, February, March, Skipper Bowles was all we worried about. Ed O'Herron was out there somewhere, and he had a lot of money. We knew where he was coming from, but Bowles was the one we were worried about.

Donald R. Lennon:

O'Herron didn't have an image except as a wealthy drugstore owner.

Gary Pearce:

No he didn't. When we ran the first “horse races” which were about the most useless parts of the poll, Hunt would be around thirty percent, Skipper Bowles had thirty percent, and Ed O'Herron would have about two percent. Peter Hart would look at that and say, “That looks great. You're way ahead of him, but it's January. The man has millions of dollars, and he is not going to be at two percent.'' It was just like looking at Ford who was thirty points below Carter, that wasn't going to last obviously.

Stephanie Bass:

{I have something I want to say before we get too much more into the campaign and that was about the governor's choice of Gary as press secretary. He talked about how the governor has a “goody-goody” image; and the way he combs his hair and the kind of clothes he wears has a lot to do with it. Of course the members of the press, being the sort of ragged, undisciplined group they are, made a lot of jokes about it, and it was a real hoot. Gary had told me, about a month before he was ready to let everybody know, that

he was going to take the job. I was prepared for it, but when Gary told everybody else, they said, “I can't believe it. Gary is going to work for the governor. Gary was one of the most popular members of the press corps. He had very few enemies and he could get along with everybody. He was real loose and easy going. He played basketball with people. I think this was a real stroke on the governor's part because the press looked at the governor and they said, “Well if he can have a guy like Gary Pearce working for him, there has got to be something ok about him.” I think that really did a lot.}

Gary Pearce:

I'm not going to be coy about that because I think one of Hunt's great abilities is to see what he's lacking and not be afraid to go out and hire somebody who can provide it for him. He did the same thing by extension in hiring her as deputy press secretary now. It would be very easy for someone like a Jim Hunt to have a lot of Jim Hunts around. Richard Nixon had a lot of little Richard Nixons around him. I think one of Carter's great strengths is that he doesn't have a lot of Carters around him. He has people who add another dimension. Jim can do that; and it requires a lot of self assurance to be able to bring people in who don't quite understand him. I've never understood my relationship to him. I don't think he understands me, and I certainly don't understand him. He can make that bridge, and he can deal with it. He realized, “I need a bridge from me to them,” and he got it. It was a stoke. It's a good way of looking at things. I'm lost from where I was.

Donald R. Lennon:

You had just mentioned who the major competition was expected to be and financing. Governor Hunt has never had the image of being well-linked with plenty of financial support, and he was running against two millionaires. How did this picture stack up? Did it cause any great concern on the part of Governor Hunt's people, or were you assured of ample financing?

Gary Pearce:

That is something other people are better qualified to answer. I saw some of it, and I think I can give you a good idea. He did it by planning ahead. That was basically Burt Bennett's job in the campaign. He was the general strategist, but [he was] also [there] to make sure money was there. He planned it far ahead. The reason Hunt won was because it was planned. They had a plan and they worked it. They literally were planning years ahead of time. Right before I came on, for example, in November and December he was spending most of that time traveling at night around the state, putting the organization together. He was picking the chairmen, visiting with them, staying in their homes. They were also building a finance structure then. It was pretty much in place when I got there. Burt was primarily responsible. Linwood Smith was the finance chairman. I remember Joe telling me --of course Joe didn't care much for Linwood-- that one of the main reasons they had him was because he was a retired textile executive, and he could call up that kind of person and was comfortable with him. He was the man on the phone and he was great at it. He could talk on the phone about money, and they talked his language as a good ole corporate boy. Finances were always a worry, but they were always able to provide it. That is one of the most amazing things because they had to get a whole lot of people to give a lot of little money. Without a massive grass roots thing, they could not have done it. You can't raise money by people giving one or two dollars. The little giver just won't do it. You won't get that much money. You have to raise it by getting a lot of people to give a thousand dollars or two thousand dollars or five hundred dollars.

Donald R. Lennon:

Did it have an effect early on your aspect of it, the press and how you publicize your candidate?

Gary Pearce:

No, it didn't on that. As I got involved . . . of course obviously the whole operation of the campaign, you know, just to keep it going and all they did. . . . We were awfully fortunate, because you hear stories about people working in a campaign not getting paid. We were always paid, and things were always on neat little checks, and bills were taken care of. It was a beautiful bookkeeping operation. We had to worry about it primarily when we got into our paid television in the summer because it's always cash on the barrel head with political advertising. They will not give you any credit, and you have to buy ahead. To buy for the summer, we had to buy in April and May which meant they had to come up with $300,000 right then; and they did it. That's just a fantastic thing. I don't know much about how they did it. They just went out and worked it and developed a lot of people. That was the county chairmen's responsibility. They assigned a quota by county. Each county had a certain amount they had to raise by the primary. They just stayed on them and bird-dogged them about it. Eventually they all paid it. If we had gone into a runoff, we would have been hurt badly. We would have had to woken up on August 19 with a quarter of a million dollars right then, and it would have been awfully difficult to have gotten it, particularly if we had fallen short. All along Joe and Burt Bennett had said that the greatest thing Hunt had going for him was that he looked like a winner. He had never lost. He had never lost. He was ahead, and that is an awfully strong arguing point. It tends to bring in a lot of people who are undecided. They say, “Well he's a winner anyway. I want to be on the right side.”

Donald R. Lennon:

Back to the press. Could you both tell a little about how you proceeded with the campaign, as far as the press capacity was concerned, any difficulties you had with particular newspapers who were supporting other candidates?

Gary Pearce:

I think I can give you a good overview on that. First I want to talk about how I look at it. It's basically an instinctive thing. Press relations is just like the rest of politics. Personal relationships can have a big effect on it. You deal with different groups in campaigns-- black voters here, money here, the organization here, the press here. The press though never directly helps or hurts you. Their interest is not to do that. Their interest is to sell papers or to sell ads on radio and TV, to have news. They are looking at you in a more neutral way. Where you can count on one group to either vote for you or vote against you, the press kind of goes back and forth. It's an accumulation of things. You will not always look good in the press. You are going to get burned sometimes. You want to look good more than you look bad, and you want to increase that percentage as much as you can. Every tiny little thing you do, it's a matter of a percentage here, a percentage there, and playing them back and forth. My theory has always been that the best way to get a good press, is to do a lot of good things and get them all in the newspapers and on radio and TV. I think that the strongest contribution I made in the campaign was that we could never have done that without having strong specifics on issues. That is the only way to get coverage.

What disturbed me most about press coverage was that they would seize on what I thought were ridiculous issues. It's very easy to play the press that way, and George Wood did a good job of it. The Constitutional Convention and that kind of thing were the kind of issues that editors have orgasms over. Even though it doesn't mean anything, it looks good to them and they get excited about it. He got a lot of editorial support that way. That was one of the things that disappointed me. I don't know that editorials have any effect on elections except psychologically. One of the biggest psychologically factors in the election was that on the Sunday before the primary, the Charlotte Observer

endorsed us over Ed O'Herron who is from Charlotte. It did absolutely no good because we ended up with about twenty percent of the vote in Mecklenburg County and got beat badly anyway; but it was psychologically critical. I feel that it killed Ed O'Herron. If he hadn't been dead before, when he woke up on Sunday morning and his hometown paper had endorsed another candidate, it just crushed him. They were able to make it up there, but I don't think they ever got the momentum back.

Donald R. Lennon:

Could that have been the difference in a clear majority and a second primary?

Gary Pearce:

Yes, it could have been. There's an interesting thing about that. Unless we made some massive screw up which we were organized well enough not to do, we were always going to lead. I don't think there's any question that on August 17, Hunt was going to be out front.

Donald R. Lennon:

You realized that, but you were trying to avoid a second primary.

Gary Pearce:

Precisely, because if we didn't win without a runoff the winner's image would be tarnished. People would say that Hunt didn't make it, and the momentum would start to go the other way. We thought it was crucial that we win. At breakfast with the staff every Tuesday morning, Joe would say, “If we don't win on August 17, it's all over.” That may or may not have been right.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you are dealing with someone with as much money as O'Herron. . . .

Gary Pearce:

Or Wood. We honestly thought Wood would finish second then. I think Burt was the only one who didn't think he would.

Stephanie Bass:

{You were talking about money and you haven't said anything about campaign finance laws, but I remember you telling me at different times that you were worried that someone with that much money as Wood or O'Herron might pump millions of dollars

into something like advertising and blow you out of the water. What were you going to do about it?}

Donald R. Lennon:

They did pump in a consideration sum, did they not?

Gary Pearce:

They did, and for what it's worth, I don't ever believe that they didn't spend a lot more than that. I would be very surprised if Ed O'Herron didn't spend five million dollars. There were a lot of people who were paid to do a lot of things, not necessarily illegal. It's frightening what you can do with money. We put limits on it. The media limit absolutely saved it because if he had been able to spend million dollars on TV, he would have spent a million dollars on TV; and he could have beaten us. The fact that there was a limit of $363,000 on media you could buy made an enormous difference. We put all of ours in TV. There was virtually no newspaper advertising, no billboards or anything like that.

Stephanie Bass:

{You were on the radio all the time just because of press conferences, statements, and statewide radio feeds which we have continued.}

Gary Pearce:

Starting from the beginning we increased the frequency. We would call stations across the state with radio tapes. We tried to be in the news two or three times a week, from January on, doing something on one of our major issues. It had to be something substantive and specific. You couldn't get up and say that we had to do something about utilities. You had to pick out a case or proposal or do something like that. We kept increasing it until June when we had our position papers put together. We had a series of press conferences in June, one a week, and it was too much for people. One of the things I believe in, is that you work with the Raleigh press corps, trying to get things out through them; and at about the point that they are about ready to scream with frustration from having heard something, is when it is beginning to sink in on people. They are like

circuits that burn out fast because so much is going over them. It was burning them out. It was an overload, but I felt we had to do it because it gave them a sense that we were talking about issues. George Wood might have been able to kill us if he had been able to convince people that we weren't talking about issues. But we were drowning them in so much stuff that from the shear volume of it, they knew we were talking about issues. They were sick of us talking about out issues. The other thing we had to do, was to seize that ground and have the campaign run on our issues and our terms.

Donald R. Lennon:

Wood was moving so fast once he got into the campaign that had you not known this, it could have been disastrous, could it not?

Gary Pearce:

I never could have seen O'Herron winning, but I thought Wood would do a lot better than he did-- that he would finish second. He came on pretty strong. He had so many organizational and technical problems with getting his ads done that really lost him a lot of time. He got in very late, of course, after Skipper dropped out.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well he came in so late that so many people were already committed.

Gary Pearce:

He tried to do it at first without an organization. O'Herron had built somewhat of an organization; but by the time Wood got in, there was nothing there. I don't know that Wood was ever very serious about it. The point I was trying to get back to earlier was when we were talking about the difference between just leading and winning. That was crucial. What won in that campaign was a sense of pride and extra effort. As you got closer and closer to fifty percent --imagining it in the poles, where you saw yourself-- it was evident to us in the last six weeks or two months that we were going to finish somewhere above forty percent. Then it got closer--somewhere between forty-five and fifty-five percent. What was going to be the difference was how much more effort you put into every incremental little bit. The closer you got, the more effort it took. But the

thing we always did in the campaign, and I think this was due to Joe more than anyone else, was we always did the extra little something. I don't care what it was, whether it was Graham arranging the schedule somewhere or having a statement ready someplace or working to make sure we had the right spot on at the right time. All those thousands of little things you have to do which just begin after awhile to drive you crazy. We always did it--everybody--with about two hundred percent effort. We tried to think, “Was there something else you could do? Was there one more phone call you could make?” I remember being at the headquarters the last weekend of the campaign talking with John Edwards, who had been brought in to work with the blacks, because Wood was making a strong push with the younger blacks. We had pretty much of a hold, but he was making some inroads. We were worrying about that and how we were going to shore it up and we made a lot of phone calls. Joe went to Winston-Salem to visit with some of the black leaders there. It was that last effort to do something. In the summer Hunt went from five or six o'clock in the morning to midnight every day. He never loafed, he never ate lunch by himself, and the only time he ever rested was in the car. And the car was where he did writing and reading.

Stephanie Bass:

{And eating, shaving and combing his hair.}

Gary Pearce:

And spraying his mouth. His hands were destroyed too. They were like hamburger.

Stephanie Bass:

{From shaking hands so much.}

Gary Pearce:

He was amazing. He would visit with people in a county and then get in the car or plane to go somewhere else, and he had a bunch of little cards with his name on them. He would sit down right there and write a note to the people he had just seen. He would give them [the notes] to his driver Walt Williamson to be mailed at the next time stop. The

next day the person would get a card from Jim Hunt thanking them for the good visit, and how well everything was going, which just continued to build it. What made the difference between forty-nine and fifty percent? It was about ten thousand things that people did. The greatest sense of pride I have about the campaign is that we always did that something extra. I think that is why we won.

Donald R. Lennon:

Hunt was going night and day. What kind of schedule did the rest of you have?

Stephanie Bass:

{I think that was one of the things Gary was talking about, the Hunt people being willing to put in the extra effort. Being on the outside then and being more in contact then as I was with the other members of the press, I could see that the press was really impressed with the Jim Hunt campaign and the people. They would wander around downstairs and see Priscilla and see this massive get-out-the-vote thing with computers, codes, and symbols and everybody working like wildfire. And you would go down the street to Ed O'Herron headquarters, and they would be working with; but they didn't have the same zeal, the same fire. All the Hunt people were just alive; they were really caught up in it.}

Gary Pearce:

It was a very young group. I don't think there was anybody working in the headquarters--with the exception of Weldon and some of the bookkeeping people who worked nine to five. . . . I don't think there was anybody else over about thirty or thirty-five, and there was a lot of energy in it and a lot of craziness. Campaigns are crazy things. Hunter Thompson can explain better what a campaign is about than anything I have ever read. It's absolute insanity, particularly if it goes on for a long time; and it went on for us from January into November. Some of it we hadn't been able to get out of. It was six-and seven-day-weeks and twelve-hour-days all the time. You couldn't measure it just by the

time you were at the office, because it just consumed you. It was everything. You couldn't think about anything else. You never got away from it.

Donald R. Lennon:

How did you relax?

Gary Pearce:

I didn't relax. I don't know. Bunches of us would go out to eat. We did relax with each other at the office or by going out together after hours. There was a lot of support for each other. There was never much division in that campaign or fighting or backbiting. That was one of the most amazing things. There was a lot of love.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no competition among the staff?

Gary Pearce:

No, there wasn't. That is probably the most amazing thing. There was never any of that which had an effect on the campaign. People always get mad at each other. Probably the best example is a personal one. I shared an office about twice the size of this one with three other people. One was Dana Herring. Dana and I had worked together from January on, but we got to where--by about the middle of June--we couldn't speak to each other, unless it was essential for business. But we functioned somehow. If we had to tell each other something, we did. We were civil but we just got on each other's nerves. We could only do it because we built up to it slowly. If you are suddenly thrown into a situation and told to work seven days a week, sixty hours a week with a lot of pressure, you couldn't handle it. But you start into it and it builds gradually and every week work a little longer and things get a little more tense. Incrementally you don't notice it, you can get used to to it. What happens is that you can't come out of it. I think we supported each other. When you saw somebody you asked how they were doing, “Are you still alive? Are you making it?”

Donald R. Lennon:

How did the governor unwind during the campaign?

Gary Pearce:

With his family. I have made it look like he is a machine. Jim doesn't have business or professional friends. He is either working or with this family. That is how he relaxes. He has deep family feelings both for his parents and for his wife and his kids. He feels a lot better and does a lot better when he is able to spend time with them. We always left him Sundays free so he could go down to Rock Ridge and stay with them. It's his form of relaxation. He always does it by scheduling time. He just doesn't go down and be with his family. He is “Mr. Total Initiative” at home. He sets aside a certain time for every one of his kids to do something that they wanted to do. One of his little girls likes to ride horses so he goes and rides horses; his son wants to play basketball so he goes out back and plays basketball. He would spend time with that one, doing what they want. That brings him back to life.

Part of the reason I think we went so hard was Jim. Jim is the kind of guy who is great to work for because he doesn't look over your shoulder all the time. He gives you a general goal of what you supposed to do like he did for me, and just expects you to do that. He doesn't care how you do it. He wants it done right and well, but he doesn't tinker with it or demand that you work a lot. You were never punching a clock. But by example, you always think you'll get home early one night and then you think “Where is he?” He's out in Rowan County at ten o'clock at night making a speech, and it becomes hard for you to say, “To hell with it” and leave early. It drives you on.

Stephanie Bass:

{It's not so much by guilt as it is by inspiration. It's not that you feel guilty because you're not working and Jim Hunt is. It's because “My God, Jim Hunt is out and he's still going and here I am. Let's get moving.”}

Gary Pearce:

It's one of the most amazing things about him and I know it's why I work for him. I don't care how tired you were or depressed you were or how badly things were going,

just to have come to the headquarters and talk with him for a couple of minutes, he could just generate energy. He was doing that when he came to the headquarters, but he was doing it out there. That was one of the most important things he was doing. He understands grass roots politics--that people who go out and get other people to go vote win elections. He was able to go out to those counties and make every one of those people feel like he thought they were the most important people in the world. The only reason he could do it was because he felt like that. He was sincere about it. They'd get that note or he'd eyeball them for a couple of seconds. . . . There is temptation in some of these places, as happened with O'Herron, that your people pump up the visit beforehand to make it a good visit. Then you leave, and they go “Wow, that's great,” and they sit back. It went exactly the other way with him. You might feel like that and think “I'll be glad when he's gone and I can relax”; but by the time he had come in and come out, you would be so charged up that you would go out and do something else. He generated that.

Stephanie Bass:

{Returning to the statement that Hunt made people feel that they were the most important ones in the world, one of Hunt's favorite words that he always sticks in no matter what you have set up for him to say is “personally” “I personally want you to know so and so.” He puts it in all of his letters, but he really means it. He is somehow able to not just by saying it, but he communicates that to you, and it's also by eye contact. You feel like when you are talking to him, he is concentrating on you. You go out and you think “My God, Jim Hunt actually thought a lot of me. He considered my opinion.”}

Gary Pearce:

That is an amazing thing he can do. One time during the campaign in the middle of summer when it was unbelievingly hot and humid, I introduced my family to him. My mother said something about about it, that he has that ability for that one second to concentrate totally on the person he is with. He remembers your name and probably will

remember it next time. You say, “Well damn, he did pay attention to me.” It was the accumulation of all of those thousands of little things that helped us win by fifty-three percent.

Donald R. Lennon:

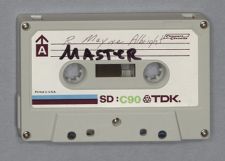

End of side one.

Gary Pearce:

Strategy is important. Plans are important. But the only thing that can really make a difference in a campaign is how well you work that plan and how well that strategy is carried out. You've got to have it, there's got to be a plan, but you have to work it. The way we worked our plan and the effort we put into it, which was basically a result of a personal feeling and drive, is what made the difference. That comes from the people at the top. They were quality people. Joe, Jim, and Burt Bennett enabled you to do it. You felt good about it and you wanted to do it.

Donald R. Lennon:

They knew what they were doing from the very beginning?

Gary Pearce:

You felt confident about that, too. The people around were good people.

Donald R. Lennon:

As the pressures built as the campaign progressed, did you ever live in fear of some disastrous slip or some statement that might come out in the press that would have been disastrous to the campaign?

Gary Pearce:

I don't know how that sort of thing happens. We did live in fear of it, but not in frozen terror every minute because we were pretty confident that we knew how to avoid it. We knew what we wanted to say. We knew, for example, how he should answer questions. We never did things without considering them. That was part of my job. A great part of press relations is how do you handle the crises and the questions that come to you. My theory is that you don't ever regret something you don't say. One of the first things I tried to teach Jim--I say “teach” as though he were ignorant--it's a difficult thing to train yourself to say “I don't know” when you don't know. That was one of the

problems that he had sometimes was to always know--he always had an answer. Some-times it was too good. You would hear people say “He's always got an answer and every issue he's got a position on it.” Well, sometimes people, I think, when you're asked a question like to hear you say, “I don't know. I never thought about that.” But try to do it. It's easy to say and hard to do. We learned to anticipate. Probably one of the more important things I did in that campaign was to learn to anticipate those questions. It's not good enough to be able to handle them once they are there. You can expect them. We could in most press conferences. Ninety percent of the time we were able to predict what the questions would be, and he was prepared. There were always things that went wrong. I would have to go back and look over that little journal I kept of the thousands of little things would pop up that would make this group mad or that group mad. You were constantly putting out little fires everywhere or a rumor that was being spread by another candidate. There wasn't that kind of mistake because we knew well enough what we wanted to do that we just weren't going to get off that; and if something got us into it, we were just going to draw back and not get hurt and think about how to deal with it first. I don't know how people get into things like Ford and the Polish thing, for example, in the debate. That's absurd. How can he get himself in that kind of position? He is an intelligent man. You don't even have to think about it, it would seem to me. Or Carter's Playboy interview--that was a colossal mistiming and poor choice of words. You can't just go into a campaign--and maybe it sounds cold and manipulative but you can't go in with the attitude of “Let's see what happens. We'll say it as it comes along, and play it as it lays.”

Donald R. Lennon:

As the pressure builds, the potential for giving a wrong response is greater.

Gary Pearce:

Sure there is more opportunity. I think what worked against that was that as the pressure built though, we were learning a lot. January, February, March, April, May we were learning to campaign. By the time it got down to June, July, and August when people were making up their minds, we were good at about everything we were doing. He was good at answering questions. We knew by then that the only thing that could kill us badly was to make a bad mistake, so we were careful. It does happen, but you can train yourself to be ready for it and work into a state of readiness.

Donald R. Lennon:

Who developed the position papers?

Gary Pearce:

Arnold Zargory (?) was the issues man in the campaign. It would follow a slow germination period. For example, the education things were a result of what Jim had been doing as lieutenant governor--a lot of his personal interests--and it was a matter of taking it, filling it out and building on it. On utilities we worked with several people. We worked with Jerry Fruitt (?) of the attorney general's office and Hugh Wells talking about it and developing some ideas throughout the winter and spring. I think my first meeting on utilities was in February. Those being our main issues. . . . Of course there are a thousand other things, but we wanted those. The issue of economic development was developed by Arnie, and it came a little later. Crime was something that Jim was on beforehand. A lot of people had a role in that, particularly Eddie Knox. They were all written in June or July, but by then it was a pulling together of things.

Donald R. Lennon:

They based them primarily on Hunt's earlier stands and feelings on these issues?

Gary Pearce:

Pretty much carrying through on what he had done in all of them. Paying a lot attention to the polls, too, but not in the sense of “What do the polls say, and what do the people want?” Polls are funny. People don't really react to issues. Late in the campaign, I think it was in September after the primary, we took a poll and asked people--those who

were voting for Jim Hunt--“Why are you voting for Jim Hunt?” One, two, three the answers were generally because “He was honest,” because “I trust people him,” or because “He looked like he would be a strong leader.” These were perceptions not issues. I think ten or twelve percent said it was because of his education program. Peter Hart said “That is amazing that twelve percent of the people voting for you can name an issue and say that was why they were voting is higher than you would imagine.” A specific issue isn't what catches people. Some people it will--special interest groups (I don't mean that in a bad way) such as a labor group or an anti-labor group. You can catch them with a certain issue. But the great run of people vote on their perception of a person, and it's an accumulation of a thousand different things. People probably vote against somebody because they don't like the way he looks. They look at him on TV and don't like him. In that sense the greatest thing we had going for us is Jim Hunt's ability to look at you and say something and make you think he means it. He could do it on TV, too, and that is what made our ads different. The campaign was as professionally done in terms of media as any in any state. Not just ours, but Ed O'Herron's and George Wood's, too. They were great. There was one big difference, and that was Hunt. O'Herron's ads never had Ed O'Herron talking to you, and Wood's ads never had George Wood talking to you. We played on that. All we did was put him in front of a camera and have him talk and then put it together from that.

Donald R. Lennon:

During that campaign I couldn't help but note that one of Wood's major TV ads showed him as a farmer with a tractor, and there was one scene with hogs that said he was a man of the soil.

Gary Pearce:

The Jimmy Carter ad.

Donald R. Lennon:

Considering that Hunt also had a similar background, I'm surprised that you didn't also have a similar ad.

Gary Pearce:

We played on the agriculture thing down east. The best description I have ever heard of what a campaign is all about was from John Sears who was Reagan's campaign manager. He said that you have to convince people that you know what their problems are and that you can do something about them. I don't think those ads were able to do it for Wood. They showed what kind of person he was. If a man can't look at you and talk to you. . . well that's not the only way to do it, but that's the best way to do it. The best way to do it is to have a man who can look at you and talk to you. Because that is the best way to judge somebody--face to face and one on one. We were able to do that through ads. It was a television thing, heavily media, but people saw him talking and believed him. That may have been the most important thing. He could feel it. When he traveled around the state, that is what he would get from people. He could feel it building. The uneasiest part of the campaign was in June before we started any television advertising. Ed O'Herron had started about three or four weeks before we did. He had to because he wasn't a well-known name. But for those three or four weeks, it hurt. You could see him growing with the TV. You could feel it out there. Once ours started, the same thing happened. We were much heavier at the end than they were.

Donald R. Lennon:

You all waited fairly late.

Gary Pearce:

Yes we did. That was the advantage you got by being lieutenant governor. That is why we never had to have billboards. Billboards are basically a way of familiarizing your name to the people. O'Herron ran a good campaign. He basically did all he could do. But anyone who ran against Jim Hunt last year basically had to depend on us to make a mistake, and we didn't. That wasn't enough to win, but it was enough to keep us above

forty-five percent. You had to do something extra to win, and we were also able to do that. We were able to save all of our money until late June and then go on very heavy and then right before the primary at saturation point. We hired Gene Dewitt(?), an advertising executive from New York who was a professional time buyer, to buy time for our spots. It is a very scientific art to know where to put the spots. If you are having trouble with certain groups, there are certain shows that you buy and there are certain ads that you put on those shows at a certain frequency. You must have a certain series of ads so they will be hit. Toward the end we planned it so that the average TV viewer was going to see Jim Hunt ad every night. You can overdo it, and that was one of the fears we had in the campaign. That is the conventional wisdom of what killed Skipper Bowles. He was on too long with too much, and people got sick of him. If people become conscious of paid TV, they can react against it. You can't overexpose on free TV. There is no such thing. People may say they are worried about overexposure, but I don't believe that because it has credibility. If you are in the news, people think that you are in the news because you ought to be in the news, and you've made news. You can't buy an ad right before or after TV news, because it blends and people start to think, “Well I've seen him on the news.” It's amazing how much that happens anyway. People will associate an ad and think they have seen you on the news. It's something that lodges in their minds, and they forget where they got it or why it's there, but they base their vote on it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Tom Stickland didn't have enough impact even down east to cause any. . . .

Gary Pearce:

He didn't have enough money or people, and he personally didn't have the ability to get enough people going for him. It was lost cause to start with. The filing deadline was either in late March or late April, and our concern then was simply who was going to be in the race. Obviously Ed O'Herron was, of course. We thought Skipper Bowles was

until he pulled out for what he said were health problems. I believe it was partly a health problem--he realized how hard he was going to have to go to win and didn't do it. He got George Wood into the race. No matter how minor a candidate would be, it could obviously have been enough to take it away. The day before the filing deadline Reginald Frazier, a black lawyer from New Bern, was all of a sudden going to get into the race. We knew he wasn't going to do much, but he was going to get some black votes, and overall he might get five percent of the total vote. We ended up with fifty-three, and he could have taken all five percent from us, and that would have put us under. We heard about it and made some calls, called _(?)_ Stallings down there and Bert in Winston Salem. Frazier was supposed to show up the next day which was the deadline and he never showed up. There were friends of his there who were expecting him to show up, and I honestly don't know why he didn't show up. That right there may have been the election. I say I don't know what happened, but we called some of our friends in that county and asked if there was anything they could do to keep him out of there. I don't know what they did, but he didn't get there.

One of the reasons for the pride we all had was that we played it clean. We went at it hard and we were hard-nosed about it, but we were honest. We kept track of every penny, and there weren't any tricks like that, and there was never an attempt to fool people. We didn't think we had to fool people. We honestly believed that if we could just get to them and show them what we were talking about and show them our candidate we had, that we could win.

Donald R. Lennon:

There was no need to attack the other candidates, either.

Gary Pearce:

Right. But that was part of the winner's image, and that was one of the things we had to learn to do. When you are riding high and a guy starts potshotting at you and

criticizing you directly, how do you react? The temptation is to blast them. That goes back to what my job was. I feel that the only thing you can do with a bad story is to get it out of the news as fast as you can. A more immediate example is this thing with the plane flight to Atlanta to the NCAA. We could make a great argument for why the governor should go, but what's the point in arguing it. That just keeps it alive. The way we dealt with every negative thing that came at us was to ignore it. This turned out to be right, not just to keep it out of the papers; but it was very frustrating to O'Herron especially because he wanted to get into a squabble with us over something. That would make them look more on the same level and get Hunt off that winning plateau. Then he sort of piggybacks on you, and all the coverage you are getting. Suddenly every Hunt story has O'Herron in it, too, if you are squabbling about something. We just ignored it, and they got more and more frustrated and would lash out a little bit more. At the end they had some ads--the puppet ad and the balloon blowing up with Jim Hunt sticker that would burst suddenly. I think those hurt, because people don't like negative campaigns. You can only win a negative campaign if you get that other guy to do the same thing back to you. Because then people say, “Look at them both calling names at each other.” As long as there is just one doing that, it takes a lot of self control because you honestly believe that what they are saying is wrong and unfair and not the kind of thing that ought to be done in a campaign. But even to say that is to focus attention on it--to get up high and mighty and say “That it's below comment.” Then they have to write the charges, and so you just have to shut up. It is hard to do. But we consistently did it. There were a couple of times we deviated from it, and we shouldn't have. It's just an absolute rule.

Donald R. Lennon:

Was there any pressure on you from the press or the public to respond?

Gary Pearce:

Yes. That was one of the jobs I had in the campaign at the end. Jim Hunt was out there to speak for himself and to explain the issues, and he was the one who had to do that. Now it is ok for me to be the spokesman for the governor's office, but then we were selling Jim Hunt. That was what people had to see. My job was to respond to the negative stuff. The best way to do it was always to treat it lightly and to make fun of it, or just say that “We don't care, that's not true.” I always handled them that way. I told him once in the campaign that I was always a smart ass but that I had never been paid to be one before, and that was what I was being paid to be. I had a lot of fun doing that, and I wish now we had the same kind of thing. You had to keep it off him and turn it back on the person who was doing it, and we were able to do that. Whenever you're a leading candidate, one of the rules of politics is that you don't get into a debate. We broke that rule, both in the primary and in the general election. We felt that it had gotten to the point that if you don't debate, people are very conscious of it. You have to debate. We didn't debate more than once. David Flaherty would have loved to debated every week, but we thought that we ought to debate him once so he couldn't accuse us of ducking him. All we wanted to do was to come out even. We wouldn't win much, but we just didn't want to lose; and we were able to do it, but it was one of the riskier things we did in a public relations sense.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well, you really didn't have much to worry about in the general election.

Gary Pearce:

No, we didn't. That was won primary night, because Hunt came out of that with so much momentum. Nobody thought we were going to get over fifty percent. The press didn't believe it. At the end they were asking us how we were going to do. We didn't want to build expectations. We didn't want to say that we were going to win because if we didn't, they would say that we had really missed it. We would generally say what we

thought was the truth, which was that, “We think we're at fifty percent, that we'll be very close to it and we might get over it.” They honestly all believed that we were just feeding them a line. I don't think Stephanie believed it. I remember telling her on primary night that I thought we were going to get over fifty percent, and we felt about that way and were pretty confident then and I think she was honestly amazed. They really thought that we were putting up a front. But when we did it. . . . I remember the cartoon in the News and Observer with the race where there was a race track and there were three guys running and the two other candidates were left. And there was just a blur and a big hole in the wall and there was something about Hunt's momentum. With Flaherty having to go into a runoff, he was just dead; and we spent the whole time campaigning for Jimmy Carter.

Donald R. Lennon:

Of course, the general reaction against the Republicans at that time too, as a result of all the problems and, too, Flaherty wasn't that dynamic.

Gary Pearce:

We realized that the biggest problem we had was overcoming overconfidence in the general election. You still had to go on TV and you still had to raise money to keep it going. That is hard to do when everybody thinks you have it made. There may have been some way he could have won, but I can't imagine it. We didn't even want it to even be close. It was important that we win enormously big. We won that one bigger than we thought, and Jimmy Carter won better than we thought. After the primary we became the Carter campaign, and we worked for him once we thought we were in pretty good shape. August 17th was a wonderful day. I have been talking about how the tension was building up, and that was the one day it all came out of us. Everyone voted that morning and then hung around the headquarters. We had a staff dinner that evening that Charlie Winbury had arranged for us out at the Women's Club or something, and Jim and his

family came up. It was after the polls had closed but before we knew any of the results, and it was very emotional kind of thing because it was so tense. The general election didn't have it because we were obviously going to win. But then there was an enormous uncertainty. Joe had conditioned us to think that if we didn't win it we were in trouble. We had gone so long and were so tired, and all we could think was that we might have to get up tomorrow and do it for four more weeks. It was so close. There was a big burst of it right there; and then we went to the Hilton once we had won, and it was just an incredible thing. None of us have been able to come down from it. We took a couple of days off then and a couple of days off after the general election, but we haven't been able to readjust. We have come back down a little and aren't going as hard, but it is difficult to get away from that pace.

Donald R. Lennon:

The adrenaline is still flowing.

Gary Pearce:

The adrenaline still flows, and you are still in a kind of campaign mind set, which is unfortunate.

Donald R. Lennon:

I noticed that at the transition headquarters.

Gary Pearce:

Very much so. Of course, we had just transferred. That was basically the headquarters for staff moved to a different place . . . just not been able to come down. I don't think it will happen abruptly. Maybe a year from now we will have.

Donald R. Lennon:

During the campaign did you stay here in Raleigh primarily at the headquarters or did you go on the road a lot?

Gary Pearce:

Most of the time I stayed here in Raleigh. I tried to travel with him a little bit. I traveled the week of the announcement--the week of April 5th. I remember because April 7, yesterday, was my birthday. I spent my birthday last year. . . . We flew from Wilmington to Asheville, a three-hour flight. It was hot and we hit the mountains and

we'd gone to two pig-pickins the night before. And I was sicker than I had ever been in my life. Most of the time I stayed here though. My contact with Jim was two, three, or four phone calls a day. Walt Williamson was his driver. As the campaign got in, we flew more and more everywhere. Peter Gilmore was his traveling aide. He kept up with his papers and his speeches and calling back to the office. I would generally check with him two or three times a day about what was coming up and what kind of questions to expect. We had a press conference somewhere about every day. We tried to say something substantive everywhere we went every day. We looked at it in terms of media markets-- Asheville, Charlotte, Greenville, Washington, and Wilmington. We wanted to hit two or three of those every week with something to say that would that would get us on TV and in the news there.

Donald R. Lennon:

Were you ever hard-pressed to really come up with something new to say?

Gary Pearce:

Yes, but because we had definite positions on the issues, we had set out a real fundamental way of looking at things. There were a lot of little parts to pull together. For example on crime, there would be a program of restitution, a career criminal program, or something to say about prisoners. We were able to keep doing it, but it was difficult. What we had to do was keep reaffirming the same general theme. That's what was important. Basically we wanted people to understand that Jim Hunt knew their problems and could do something about them. More specifically, on crime we were talking about more definite sentencing, speedier trials; and so everything you said had to kind of feed that idea. We would have a new specific with the same point. The specific would be the news. He would propose this program or talk about this, but he would come back to the same idea and keep repeating that. It was tough.

Donald R. Lennon:

When you were reaffirming a position, did the press ever look at it and say, “Well, we ran this two weeks ago.”?

Gary Pearce:

That was why you had to add a new little piece to it. For example, if you talked about the victim compensation plan, you'd say why it was important. That was how you make it. The news is victim compensation, but it would feed the same idea. You had to have something new. It wasn't enough to keep saying that crime was a problem and that we need to do something about it. Eventually that loses it. We started a lot earlier so it was a problem. We got down to end and everyone started throwing things. O'Herron's thing in the last weeks was a three-hundred-million-dollar-road-bond issue. Wood had a tax reform thing at the end. That was clearly desperate kind of stuff. One of things I found, which I guess I'll know in the next campaign, and it's a sad commentary on the way campaigns are covered. . . . It puts you in a position where you almost have to manipulate. I hesitate to say that, but I don't think that it was something that we did coldly. The stories that did us so much good at the end of the campaign, were stories about how well we were doing. For example, how we were getting all this black support here, or how we were getting enough money to go here, or how Jim Hunt's campaign seems to have momentum here. It was a self-fulfilling prophesy. They weren't looking at issues at the end. They were saying, “How well is the campaign run?” The last two or three weeks of the campaign many of the stories were on how good Jim Hunt's campaign was, not what he was saying or what he was like, but how well things were going for him. It was unfair. We benefited from it, but it is a poor way to cover a campaign. It helped us, but the press is going to have to learn because it becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy. They were making our campaign go well by saying that we were doing well. It didn't necessarily have anything to do with how well-qualified Jim Hunt was to be

governor. I don't know how you overcome that. It was covered like a horse race, and it was even worse in the presidential campaign. That was why Carter almost lost. The sensation was that he was making mistakes. . . . [They weren't paying any attention to] what his abilities were or what his qualities were, but how well his campaign was going.

The press in North Carolina didn't fall for that too badly. The Raleigh press corps is the one that will report it that way. You can go out to Greensboro or Greenville and the Raleigh press corps would make fun of this. But you'd read a story the next day about what Jim Hunt said about issues. They would look at that and say that it was old stuff or a bunch of bull, but people could get a better idea from a paper like that of what Jim Hunt was saying. It was not about how well his campaign was doing or how he was getting this support or that support. It's what he's saying. That is one of the things that is best about the press out there, and we took great advantage of it. We realized that you don't get your message across very well through the Raleigh press corps. You have to go to those cities and towns where people aren't so jaded and so caught up with the trees that they won't report the forest. We would have a press conference in Raleigh almost every week or every two weeks, but we would also have one every week or two in Greensboro or we'd have one in Greenville every couple of weeks. We would have them in every little town, because for that one day that one section of the state would focus on that issue and nothing else. That is a credit to Jim. You can't be any more successful as a press secretary than the candidate you have. The thing about accessibility . . . he was it. If a reporter wanted to fly with him or sit with him or listen to a speech or go anywhere, he was there. If they wanted an interview, he was there and he would do it. It's that effort-- making the extra effort.

Donald R. Lennon:

What was his attitude toward the public?

Gary Pearce:

It was a very open kind of thing. You can't buy that. If a guy doesn't have it . . . and that's basically what O'Herron didn't have. He couldn't make the speeches or stand up in a press conference and stay cool and make a good appearance. In a lot of ways it is unfortunate. Why is Jim Hunt anymore qualified to serve as governor because he has an ability to stand up without shaking to death and talk strongly and firmly and present himself well? Does that make him any better than Ed O'Herron who got the quakes and wasn't very articulate or George Wood whose major drawback was that he had a squeaky voice? He was born with a voice that didn't sound good on TV. He was a brilliant man and basically a good fellow, but he didn't sound good on TV. It was just a sheer physical thing.

Donald R. Lennon:

The mass media has changed politicking.

Gary Pearce:

That's right. It's a fact that you have got to be a good performer. I hate to say that, but in the debates or in any kind of interview or joint television appearance Jim would always look good because he is a good performer. He did well on the spots and he did them by himself. The way they did the spots was as a question and answer session. They would get a group of students or a group of workers, and they would ask him questions. He would talk to them about what he wanted to do. They'd be prepared a little bit about what his positions were and what areas to go to. It was basically a talk session and not a written out spot. We did write scripts so he'd have an idea of what he was trying to get to. We'd have this session and basically we'd want to come out with this spot. He'd talk with them and answer their questions and work with them. They would then have thirty or forty minutes of film that they could go back and look through and find that one place where he said it better. There was a reading ad that probably had as much impact as any ad had around here. In it he was talking to a group of parents about schools. It went

something like: “Not too long ago I talked to a mother about her fourteen-year-old son who had been to school and he hadn't learned to read.” He said, “He hadn't learned to read!” You could tell there was a real flash of genuine anger that people could tell when they saw it. We got more reaction from that ad, both pro and con. Teachers hated it because they thought it was an insult to them. Parents were taken aback by it. The strongest evidence I have of this is from one of the more objective and best reporters in the state, Ferrell Giller(?), who has now gone to Washington. He told me during the campaign that, “As much as I cover campaigns and as objective as I am, that the ad got to me.” He had a couple of kids in school, and he felt a reaction just instinctively when he heard the ad.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well obviously it was not contrived.

Gary Pearce:

Exactly. You can't contrive. It either comes or it doesn't. Of course, it is difficult to even do it with a camera on you and a microphone around your neck knowing you're trying to do a spot. As a matter of fact he once just about got electrocuted. It was on his farm in Rock Ridge, and they had the mic run up his back and under his tie so you couldn't see. They had a sound man with a wire and they were outside in one of the fields. The guy pulled the cord around and pulled it up against this electrified fence. It was one of the worst moments, but he survived. He survived a lot of things.

An August campaign is brutal. One reason Jim won is because of his youth and energy. It was hot, and to travel across the state literally getting up at five o'clock in the morning to go to a plant gate and ending at midnight, six days a week, you can't imagine the drain on you. O'Herron didn't stand up well. Right at the end he looked terrible. He was obviously dragging. Jim somehow has an ability, no matter how bad off he is. . . . He'll be in a car and for him just to be tired like that and he'd be back laying, just dead,

and he'd get there and he has the ability to pull himself together and get out with a burst of energy. Sometimes he was flat. There were a couple of press conferences where he obviously was flat, but they were rare. That was a great factor in the whole campaign. That was also part of what they wrote. One of the ways you could manipulate the media is when they travel with you. They are not used to it. They work an eight or nine hour day, maybe they work a couple hours overtime one day. When they would ask to travel with him a couple of days, you would put them on a plane at six o'clock in the morning and pick them up at midnight the next day, and they would just be dead because they hadn't built to it. It's a conditioning kind of thing that Jim had built up to. They'd come out and see him fresh and they didn't realize that that was it because they weren't used to it. It's a grind anyway. They would then write about how energetic Jim Hunt was. I should have made this point a lot stronger than I have, but in the campaign the issue was simply leadership, the idea that we had been drifting, that to get North Carolina moving again we needed strong leadership. That is what he represented. His energy contributed to it. There was a spate of stories in the summer of Jim Hunt campaigning energetically, strong, young, vigorous and it was great. O'Herron was obviously an older man, and Wood was lazy. People would travel with him and he would spend a couple of hours eating alone and not shaking hands. It hurts.

Donald R. Lennon:

The mere fact that O'Herron was a millionaire businessman really didn't do him any good.

Gary Pearce:

The greatest temptation was to do negative ads. I don't know that David ever did prepare one, but he always wanted to fix a couple to have. One of the things that we did that we realized would help us so much was in early May to release Jim's tax returns and statement of his net worth, which included everything--his cars and how much money he

had in this bank. It wasn't that much. I think he had $100,000 in assets and $40,000 in debts. His net worth was sixty some thousand dollars. Most people looked at that and thought well he has a house and a couple of cars so he's a fairly successful person. In some ways it hurt us, because one of the things in there was in 1972 when he had a law practice, and his only income was $7000. He was running for lieutenant governor, but we picked up some things, particularly from business groups, who were wondering what kind of man is it who could make only $7000 a year.

Donald R. Lennon:

I heard the same thing. Someone says, “a prominent lawyer and a farmer and he isn't worth more than $60,000, there's something wrong here.”

Gary Pearce:

We were worried a little bit about that. But I always felt that there are a lot more people in the world who are less than $60,000 than are worth more than that. I felt it could never do anything but benefit him. It put O'Herron in a position of either hiding it or releasing it. He was worth about $20,000,000 and that hurt him badly. No one can convince me that it didn't. He was really never able to sell himself as a. . . . He was a wealthy man and a businessman, but he was not able to communicate that quite as well as he might have.

Donald R. Lennon:

I imagine that until he got into his campaign he had never had to do this type of thing. As a lawyer and someone who had been in politics as long as the governor had--he grew up in it.

Gary Pearce:

Someone who went to O'Herron's first press conference said it was a disaster because he was not used to. . . . Stephanie describes them as a bunch of ragtag hippies, all under thirty, asking him a bunch of hostile questions. He was used to being in a boardroom and people saying, “Yes sir,” and being quiet. He wasn't ready for all of that hurly-burly. I drove by his house in Charlotte once, a great big white mansion on green

grounds, and I told David Sawyer about it. He had an ad right there. He was simply going to have a statement of his net worth on an overlay and start way back from the house and just come in on the house with the stuff running. It could have been devastating, but we didn't want to do negative ads.

One mistake a lot of people made, including O'Herron, was that they underestimated Jim. In some ways Jim doesn't look like a governor. He looks like a very boyish person in some ways, but he is very mature. The thing that sets him apart is that he has an incredible enthusiasm for life and a vitality. He enjoys everything. He enjoys being governor, he enjoys riding airplanes, he enjoys playing with his family, and he enjoys watching a basketball game. The excitement just does it. I think people take him as being immature. O'Herron was a businessman and a millionaire, and they looked and thought that this guy was just waiting to be beaten. They really sorely underestimated him. They expected him to make a mistake. They thought if they just put together a well- financed campaign, he would not be able to handle it. The biggest mistake you can make is to underestimate your opposition. We overestimated ours. We overestimated O'Herron's ability to sell the businessman thing. We overestimated George Wood's ability to do a lot of stuff, but overestimation is not a mistake in campaigns. I think that was the crucial mistake they made.

Donald R. Lennon:

Do you think it would have been wise for them to look back to 1972 and see how smoothly that campaign ran?

Gary Pearce:

Yes. That was a classic case of doing the same thing. I was working for the newspaper and I remember the attitude--that's a classic example of Bowles's people seemed to spend the last three or four weeks of the campaign dividing up the government, and in the end they lost it.

Donald R. Lennon:

Well I meant Hunt's campaign in 1972--the lieutenant governor campaign.

Gary Pearce: