| Edcuational Publication No. 73 | Division of Supervision No. 17 |

| L. C. BROGDEN | Director |

| MISS HATTIE S. PARROTT | Assistant State Supervisor Rural Schools |

| JOHN J. BLAIR | State Director of Schoolhouse Planning |

| W. F. CREDLE | Assistant Director Schoolhouse Planning |

| E. E. SAMS | County Superintendent of Lenoir County |

PUBLISHED BY THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTIONRALEIGH,1924

CONTENTS

| Introduction by State Superintendent of Public Instruction | 5 | |

| Preface | 7 | |

| PART I | ||

| The Present Educational Situation in Lenoir County | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Lenoir County, Physical Characteristics, Population, Taxable Wealth and Roads | 9 |

| II. | Present Plan for Meeting Educational Needs of Rural Children of County | 13 |

| III. | Are the Rural Pupils Studying All the Important Subjects They Should? | 14 |

| IV. | Are the Rural Pupils Having Each Day as Much Time as They Should on Certain Important Subjects? | 16 |

| V. | Are the Rural Pupils Attending School as Regularly as They Should? | 22 |

| VI. | Training, Experience and Annual Salary of Rural Teachers and the Teachers of the Kinston and LaGrange Schools | 29 |

| VII. | Under Present Plan are the Rural Pupils Reading, Spelling and Working Arithmetic as Well as They Should? | 34 |

| VIII. | Under the Present Plan are the Pupils Graded and Classified in Accordance with Their Ability to Advance? | 64 |

| IX. | How Much Education are the Rural Pupils Getting Under the Present Plan? | 73 |

| X. | Are the Rural Teachers Developing in the Pupils the Powers and Habits of Mind Essential in Making a Good Citizen? | 86 |

| XI. | Are the Rural Pupils Attending School in Buildings Adequately Constructed and Equipped? | 99 |

| XII. | How Much is it Costing to Teach a Rural Pupil Under the Present Plan? | 150 |

| XIII. | Can the Rural Pupils Have Equality of Opportunity Under the Present District Plan? | 156 |

| PART II | ||

| Proposed Plan for Reorganization and Support | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| XIV. | Under What Plan Can Country Children and City Children Have Equality of Educational Opportunity? | 165 |

| XV. | The Proposed County-wide Plan for Lenoir County | 176 |

| XVI. | What This Plan Will Mean to the Children in the Various Consolidated Centers | 195 |

| XVII. | How This Proposed Plan Can Become Operative | 206 |

| XVIII. | Total Cost of Proposed Plan and Total County Tax Rate Needed | 210 |

| XIX. | Mutual Advantages to Town and Country in Joining in County-wide Plan | 217 |

| XX. | Summary of Findings and Conclusions | 227 |

INTRODUCTION

The Lenoir County Board of Education requested the State Department of Education to assist it in determining the exact condition of public education in that county and in setting up a modern, progressive program of reorganization and support.

The State Department of Education gladly accepted this invitation and undertook as comprehensive study of the conditions surrounding the public schools of the county as the time and means at its disposal would allow. Mr. L. C. Brogden, of the State Department of Education, was made director of the survey, and the following report has been submitted to the Lenoir County Board.

This bulletin sets forth in comprehensive, simple terms the results of this study. It not only presents the facts as they were found, but also undertakes to analyze them and to interpret them as a basis for a reorganization of the whole system in accordance with a county-wide plan. It advocates the following principles:

(a) That the support of public education in a county should rest on a uniform county-wide tax for a minimum school term of at least eight months for all the children of the county.

(b) That all school buildings should be constructed out of funds furnished by the county as a unit.

(c) That the scheme of reorganization should be on a county-wide basis, and should furnish standard educational opportunity to all the children in the county.

The bulletin presents most conclusive evidence that Lenoir County is financially able to support such a system of schools with a tax rate that cannot be considered burdensome. It should be worth a great deal to all the people of the State to know that such a promising scheme is within their reach if they wish to have it.

This report shows typically a complete cross-section of the condition of rural education in the greater part of North Carolina, and at the

same time shows that we are not without a remedy. For these reasons, and for many others that might be mentioned, I am causing this report to be printed in the belief that it will be of great assistance to county boards of education, to county superintendents of schools, and to all people who are interested in the education of the youth of the State for citizenship in a democracy like ours.

State Superintendent Public Instruction.

PREFACEThe specific purposes of this survey have been six-fold:

(a) To find the present plan of educating the white rural children of the county.

(b) To find the extent to which the educational needs of the children are being met under the present plan.

(c) To find the daily cost of teaching per pupil in daily attendance in these schools.

(d) On the basis of facts found, to work out a constructive county-wide plan of school consolidation anl school building.

(e) To indicate the particular advantages of the proposed county-wide plan.

(f) To find the total cost and the total county-wide tax rate needed to put this county-wide plan into successful operation.

We believe that this problem of working out a constructive county-wide plan of school consolidation and school building, providing for all the children of all the people adequate and modern elementary and Class A high schools in one unified and efficient county system of schools, is the most far-reaching problem that can engage in its solution, the thought and unified effort of the people of the whole county. We believe the successful solution of this problem constitutes the mud-sill of our fullest economic development and expansion, and the mud-sill of an intelligent, progressive, happy and efficient rural citizenship.

We have undertaken to get at first-hand all the essential facts involved in a thorough-going and reliable county-wide survey, to interpret and to discuss them in the light of common every-day experience, avoiding technicalities wherever practicable.

The scope of the survey has included visitation to every white school in the county, both rural and urban. In studying the quality of instruction being received by the white rural children, the work of every teacher, with but one exception, was observed, and a total of more than 150 recitations were carefully studied.

In the testing program, standardized tests were given to the children in every white rural school in the county, and also to the children in all the elementary grades in the Kinston and LaGrange schools. A total of 943 rural children were given tests, while a total of 1,161 in the Kinston and LaGrange schools were given tests, making a total of 2,104 children given separate tests, and a total of 6,398 different papers scored.

In studying the white rural school buildings of the county, every building was visited and scored by these experts, using standards of measurements recognized and employed by authorities throughout America.

Believing the educational problems to be solved in Lenoir County to be common to all the other counties of the State, and believing the method suggested for their solution equally applicable to every other county in the State, we have attempted to make this survey sufficiently comprehensive and intensive both in method and scope to be a helpful guide to county boards of education, county superintendents, rural school supervisors, high school principals and teachers, school committeemen and patrons throughout the State, who are engaging in the solution of these common problems.

In the absence of a complete survey of the colored schools of the county, it is not possible to determine the number and location of the schools that will be needed to accommodate the colored children. It is also impossible to determine the cost of the reorganized system of schools that is to be provided for the colored race. The county board of education has expressed its purpose of providing for the colored citizens of the county comfortable, well-built school buildings, adequate to accommodate their children.

The several colored school districts will be carefully studied, and in all probability will be regrouped with the idea of making better schools, and at the same time promote economy of administration. A reasonable amount of money for the building of the colored schools will be provided in the general plans adopted for developing the county-wide school system for both races. It will be possible to secure several thousand dollars from the Rosenwald Fund and from the colored people themselves for improving their schools. This will greatly reduce the cost to the county, and at the same time secure the new and better schools the colored people need.

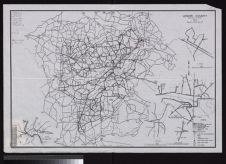

THE SURVEY STAFFThe survey staff consisted of the following members: Miss Hattie S. Parrott, Assistant State Supervisor Rural Schools, in charge of testing program in both rural and urban schools, and also aiding in scoring the rural school buildings; Mr. W. F. Credle, Assistant State Director of Schoolhouse Planning, rendering an essential service in scoring the white rural school buildings of the county; Mr. John J. Blair, State Director of Schoolhouse Planning, who made the maps presented in this report; L. C. Brogden, State Supervisor Rural Schools, who made the other investigations and studies embodied in this report, and Mr. E. E. Sams, Superintendent of Public Instruction of Lenoir County, without whose constant, untiring, and efficient coöperation in every phase of the work the survey could hardly have been made.

For helpful criticism of the survey, the survey staff is indebted to State Superintendent A. T. Allen, Dr. M. R. Trabue, of our State University; J. E. Hilman, Director of Teacher-Training; J. H. Highsmith, Supervisor of High Schools, and N. C. Newbold, Director of Negro Education.

L. C. BROGDEN,

Director of the Survey.

PART ONEThe Present Educational Situation in Lenoir County

CHAPTER I

LENOIR COUNTY

1. ITS LOCATION AND PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS.

2. POPULATION, COMPOSITION AND DISTRIBUTION.

3. TOTAL TAXABLE WEALTH.

4. ROADS.

(1) Location and Physical Characteristics. In land area the county is about an average county, containing 390 square miles.

*“It lies in the southeast section of the tidewater region of the State and on the lower course of the Neuse.

“Cotton and tobacco are the great money crops. The soil is well adapted to the cultivation of corn and all other cereals; also Irish and sweet potatoes. All the fruits of the temperate regions can be successfully grown, and the cultivation, if made a specialty, would be attended with profit. There are no lands in the entire State of North Carolina better adapted to the cultivation of bright yellow tobacco than the lands of Lenoir County. Owing to the great prosperity of the county, land is in demand. There is a high order of intelligence among the farming population, and they are well abreast with the recent improvements in farming.

“The Atlantic and North Carolina (now the Norfolk and Southern) Railroad traverses the county, giving access to all the markets; and this facility has given an impetus to truck farming, for which soil and climate are well adapted, and all the early vegetables cultivated on the shores of navigable waters are sent to markets from Lenoir with equal facility and profit. Kinston, the capital, is situated on the Neuse River, and is also the southern terminus of a branch of the Atlantic Coast Line.”

(2) Total Population and its Increase. According to the fourteenth census, the total population of the county is 29,553, in 1910 it was 22,769, while in 1900 it was 18,639. The total population of the county increased 22.2 per cent from 1900 to 1910, but from 1910-1920 it increased 29.8 per cent. The population per square mile in the county in 1920 is 75.8 per cent, while the population per square mile for the entire State is only 52.5 per cent. In population per square mile the county is far above the average for the State. There are only fifteen counties in the State with a larger population per square mile than Lenoir.

(a) Rural Population and Its Increase. In 1900 the rural population of the county was 14,553; in 1910, 15,774; while in 1920 it was 19,784. The increase in the rural population of the county from 1900 to 1910 was only 8.5 per cent, while from 1910 to 1920 the increase rose to 25.4 per cent. The rural population per square mile is 50.7 per cent, while the rural population for the entire State is 42.4 per cent. In rural population per square mile the county ranks twenty-fifth.

*North Carolina and Its Resources, State Department of Agriculture.| (b) Distribution of Rural Population by Townships. | ||||

| Name of Township | 1920 | 1910 | 1900 | Per Cent Increase, 1910-1920 |

| Contentnea Neck Township | 2,182 | 1,970 | 1,515 | 10.7 |

| Falling Creek Township | 1,666 | 1,248 | 1,148 | 33.5 |

| Institute Township | 1,416 | 1,125 | 1,123 | 25.8 |

| Kinston Township, including Kinston, etc. | 11,676 | 8,360 | 5,551 | 39.6 |

| Moseley Hall Township, including LaGrange | 3,327 | 2,737 | 2,585 | 21.6 |

| Neuse Township | 1,172 | 967 | 836 | 21 |

| Sand Hill Township | 761 | 623 | 664 | 22.2 |

| Southwest Township | 561 | 623 | 681 | * |

| Trent Township | 1,980 | 1,512 | 1,257 | 31 |

| Vance Township | 1,801 | 1,374 | 1,061 | 31 |

| Woodington Township | 1,478 | 1,090 | 1,123 | 35.6 |

From the above table it will be seen that the population in some of these strictly rural townships during the past decade has grown more rapidly than in others; that Woodington Township, with its 35.6 per cent increase since 1910, leads all the others, but with Falling Creek, with its 33.5 per cent increase, a close second. Southwest Township is the only township which has actually lost in population since the last census.

The facts indicating the growth in population in these respective townships should have careful consideration in a school building and school consolidation program.

| (c) Town Population, Its Increase and distribution. | ||||

| 1920 | 1910 | 1900 | Increase in Per Cent, 1910-1920 | |

| Kinston City | 9,771 | 6,905 | 4,106 | 41.5 |

| LaGrange | 1,390 | 1,007 | 833 | 38 |

| Pink Hill | 166 | 58 | 54 | |

| Totals | 11,327 | 7,970 | 4,939 |

From the above table it will be seen that the town of Kinston increased its population from 1910 to 1920 41.5 per cent; that LaGrange increased its population in that period 38 per cent, and Pink Hill increased its population from 1910-1920 approximately 54 per cent. And this proportionate increase in the population of these respective towns during the past decade should be also taken in consideration in a county-wide program for school consolidation and school building.

| (d) Racial Composition of Population. | ||||||||

| Total Population | Native White | Native White Foreign Born | Native White Mixed Parentage | Negro Population | Per Cent Native White | Per Cent White Foreign Born | Per Cent Negro | |

| 1920 | 29,555 | 16,384 | 80 | 40 | 13,061 | 55.4 | 0.4 | 44.8 |

| 1910 | 22,759 | 12,583 | 30 | 10,225 | 55 | 0.1 | 44.9 |

From the foregoing table it will be seen: (a) that the native white population in 1920 constituted 55.4 per cent of the total, or a gain of four-tenths of one per cent since 1910; (b) that the white foreign-born constituted in 1920 four-tenths of one per cent of the total, or a gain since 1910 of three-tenths of one per cent; (c) that the negro population in 1920 constituted 44.8 per cent of total, or a relative loss of one-tenth of one per cent since 1910. It is quite clear that education in Lenoir County is but little affected by the foreign-born element in its population.

(3) Total Taxable Wealth and Increase in its Farm Value. The total taxable wealth of county for 1923-24 is approximately $29,250,000. In taxable wealth Lenoir County stands far ahead of the average county in the State, standing 28 from the top of the list. In 1920, 189,153 acres of land were in farms in the county, which was 75 per cent of its land areas. In 1900 the total value of all farm property in the county was $2,026,515, in 1910 it had risen to $4,156,271, and in 1920 had risen to $23,509,250, a gain of approximately 100 per cent from 1900 to 1910, but a gain from 1910 to 1920 of more than 500 per cent. In its total value of all farm property, Lenoir is surpassed by nine counties only in the entire State.

The average value of all property per farm in the county in 1920 was $7,435, while the average value of all property per farm for the State as a whole was only $4,634. In this average value of property per farm Lenoir County is surpassed by three counties only: Greene, Pitt, and Wayne.

(4) Roads. A few years ago Lenoir County voted a two million dollar bond issue for roads. It now has, or soon will have, approximately 70 miles of hard-surface roads. It is quite probable that the county has more miles in hard-surface roads for its size than any county in the entire State.

− WHITE RURAL AND URBAN SCHOOLS UNDER PRESENT PLAN

WHAT IS THE PRESENT PLAN FOR MEETING THE EDU-

CATIONAL NEEDS OF THE RURAL CHILDREN OF THE

COUNTY?

Outside the city of Kinston and LaGrange, which are independent school districts, the schools of the county are under the control of the county board of education, consisting of three members. The members of this board are nominated from the county at large at the county primary, and their nominations are ratified by the State Legislature.

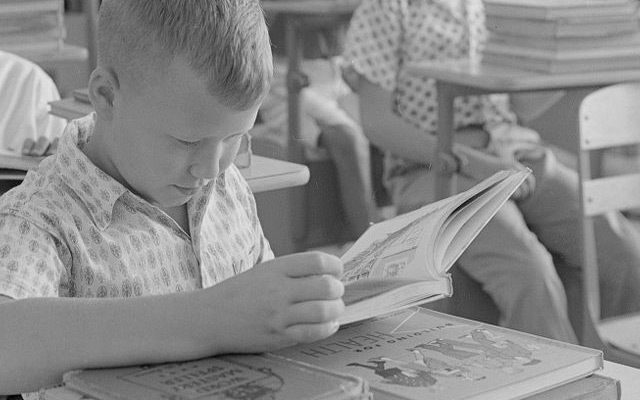

This board is now undertaking to meet the educational needs of the white rural school children through the maintenance of 42 separate schools in 42 separate school districts, embracing an area of 390 square miles. (See map on preceding page.) Each of these 42 schools has its committee of three members appointed by the county board of education.

Of these 42 school districts twenty have voted a local tax, ranging in rate from fifteen to thirty cents on each one hundred dollars assessed valuation of property. The assessed valuation of property in these 42 school districts ranges from $163,915 to $772,345. The local tax voted is used to supplement the appropriations from the county school fund in lengthening the school term or increasing the salaries of the teachers.

The length of school term in these 42 school districts averages from 6 to 8 months. In three of the districts the school term last session was seven months, in five it was eight months, while in the remaining 34 it was six months only.

Of the 42 schools, fifteen are one-teacher schools, nineteen are two-teacher, six are three-teacher, one a four-teacher, and one is the Pink Hill consolidated school, employing ten teachers. The white one-teacher schools constitute 35.7 per cent of the total number, while the one- and two-teacher schools combined constitute 80 per cent of the total number. In five of these one-teacher schools one teacher alone is having to teach all the seven grades of the elementary school; in six one teacher is having to teach six grades; while in four schools only is one teacher having to teach as few as four grades of work. In these 42 schools four teachers only are giving their entire time to high school work, and three of these are in the Pink Hill consolidated school.

The total white revised rural school census 6-21, for 1921-22 was 3,289. Of this number 2,936 were enrolled during the past session, with an average daily attendance of 1,829. This means that 89 per cent of the revised census was enrolled, that only 55.6 per cent of this census was in daily attendance, and that only 63 per cent of even the enrollment were in school every day during the past session.

CHAPTER III

ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS HAVING THE

OPPORTUNITY TO STUDY ALL THE IMPORTANT SUB-

JECTS THEY SHOULD?

| TABLE 1—Showing Per Cent of the Various Types of Rural Schools in County in Which Teacher's Daily Schedule Shows no Provision for the Teaching of the Subjects Indicated Below. | |||||

| Subject | One-Teacher, Per Cent | Two-Teacher, Per Cent | Three-Teacher, Per Cent | Moss Hill, Four-Teacher | Pink Hill, Ten-Teacher Consolidated School |

| Writing | 60 | 31.6 | |||

| Spelling | 6.7 | ||||

| Physiology, sanitation, or hygiene | 20 | 26 | |||

| History | 13 | ||||

| Civics | 73 | 42 | 50 | no provision | |

| Agriculture | 60 | 52.6 | 33⅓ | ||

| Music | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Physical education | 100 | 93.3 | 100 | no provision | |

| Cooking and sewing | 100 | 100 | 100 | no provision |

(1) Writing.—Shall the pupils in all the rural elementary schools of the county have writing lessons every day? In 60 per cent of the one-teacher schools and in 31 per cent of the two-teacher schools there is no place for writing lessons on the daily schedule of the teacher.

(2) Spelling.—Should spelling be taught every day in the rural elementary schools of the county? In 6.7 per cent of the one-teacher schools, the teacher's daily schedule shows no place for the teaching of this subject.

(3) History.—Is not this subject of sufficient importance to be taught in every rural elementary school of the county? In 13 per cent of the one-teacher schools there appears no place on the teacher's daily program for the teaching of this subject.

(4) Physical Education and Hygiene.—Is it as important for our country children to become physically as well as mentally fit? In 20 per cent of the one-teacher and in 26 per cent of the two-teacher schools no provision on the teacher's daily program for the teaching of these subjects.

(5) Agriculture.—Since a majority of the children now growing up in the rural districts are going to become farmers, is it not a matter of common sense that these children should have ample opportunity to grasp at least the elemental facts about the occupation they are going to follow? In 60 per cent of the one-teacher schools, 52.6 per cent of the two-teacher schools, and in 33⅓ per cent of the three-teacher schools there appears no provision on the teachers’ daily schedule for the teaching of this subject.

(6) Music.—Shall our rural children have a fair chance at this subject? Shall not the country school equip boys and girls to make a life as well as to make a living; shall it not equip them to enjoy the “refined pleasures of life”; to get more joy out of, and add more joy to, country life? For the whole of country life is not taken up with the actual struggle of making a

living. There come hours of freedom from toil, and of diversion of some sort. Therefore, the country school cannot escape the responsibility of equipping these boys and girls to use these hours of relaxation to the greatest advantage to themselves, and to those about them. And what one thing enables them to get more real joy out of life during these hours of relaxation than the understanding and appreciation of good music, than the ability to sing well and to play well upon a favorite instrument? What offers more genuine pleasure to the country home on the long winter evenings when the family is gathered about the glowing fireside than the singing and the playing of the children upon their favorite instruments, the songs of the old masters as the evening hours wear away, and what adds more to the life and interest of the country Sunday school and the country church than good music?

And yet in only one of the 42 rural schools of the county is there any place on the teachers’ daily program for the teaching of music, and this is in the one consolidated school in the county.

(7) Civics.—In this age when we are stressing so much good citizenship, is it important that our rural pupils have an opportunity to study in a systematic way the simple facts underlying good citizenship and good government?

In 73 per cent of the one-teacher, 42 per cent of the two-teacher, and 50 per cent of the three-teacher schools there appears no place on the teachers’ daily schedule for the teaching of this subject.

(8) Domestic Arts.—Shall the girls in our rural schools, the majority of whom will become home-makers and home-keepers, have ample opportunity to equip themselves for the profession they are going to follow?

In not one rural school in the county is there any provision on the teachers’ daily program for the teaching of this important subject.

To Sum Up: It will be seen from the above table—(1) That in 60 per cent of the one-teacher and 31.6 per cent of the two-teacher schools there appears no place on the teachers’ daily program for the teaching of Writing; (2) that in 6.7 per cent of the one-teacher schools there appears no place on the teachers’ daily program for the teaching of Spelling; (3) in 20 per cent of the one-teacher schools and 26 per cent of the two-teacher schools no place for Physiology, Hygiene, or Sanitation; (4) in 13 per cent of the one-teacher schools no place for History; (5) in 73 per cent of the one-teacher, 42 per cent of the two-teacher, 50 per cent of the three-teacher, and in 100 per cent of the four-teacher schools (only one 4-teacher school) no place for Civics; (6) in 60 per cent of the one-teacher, 52.6 per cent of the two-teacher, and 33⅓ per cent of the three-teacher schools no place for Agriculture; (7) in only one of the 42 rural schools does there appear any provision for the teaching of Music; (8) in only one of the 42 rural schools does there seem to be on the program any provision even looking in the direction of what may strictly be termed physical training; (9) in not one single rural school does there appear any place for the teaching of Domestic Arts, Home-making, and Home-keeping.

CHAPTER IV

ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

RECEIVING EACH DAY AS MUCH TIME AS THEY

SHOULD ON CERTAIN IMPORTANT SUBJECTS?

| TABLE 2—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Reading. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 20.7 | 14 | 12 | 11.5 | 12.6 | 10 | 13 |

| Two-teacher | 42 | 27 | 25 | 17 | 14.4 | 16 | 14 |

| Three-teacher | 38 | 27.5 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 16.7 | 21 |

| Four-teacher | 60 | 40 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 90 | 55 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 125 | 135 |

| LaGrange | 115 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 218 | 227 |

| Kinston | 60 | 60 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 318 | 318 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen that in the daily amount of time given to the subject of Reading, the one-teacher school is the laggard in the race; that while it devotes 20.7 minutes only to this subject each day, in the first grade, the Pink Hill consolidated school devotes on the average 90 minutes a day, or more than 400 per cent more time. If we compare the amount of time given to this subject in any one grade in the one-teacher school with the amount of time given to this subject in the same grade in the Pink Hill school the difference is quite noticeable.

(2) While the two, three, and four-teacher schools are devoting on the average from 31.3 to 47 minutes daily to this subject in each of the first three grades in an average school term of 132 days, the LaGrange school is devoting on the average 63 minutes a day, or nearly 100 per cent more time, and for a school term of 180 days.

(3) Owing to the over-crowded conditions in the Kinston school, and the necessity for a double shift, the time devoted to reading as indicated on the table may not represent it fairly.

| TABLE 3—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Writing. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Two-teacher | 11.5 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Three-teacher* | |||||||

| Four-teacher | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 10 | †30 |

| Pink Hill | 15 | 35 | 15 | 20 | †15 | †20 | †30 |

| LaGrange | 20 | 15 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kinston | 20 | 20 | 15 | ‡12 | 15 | ‡16 | 20 |

(1) To the subject of Writing in each of the first three grades the one-teacher schools devote an average of 12 minutes daily, while the Pink Hill Consolidated School devotes an average of 22 minutes daily, or nearly 100 per cent more time.

(2) Again, while the one-, two-, three-, and four-teacher schools devote on the average of from 10.5 to 12 minutes a day to this subject in each of the first three grades, the Kinston and LaGrange schools devote on an average from 18 to 22 minutes daily.

| TABLE 4—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Spelling. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 12 | 7.8 | 8 | 6.6 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Two-teacher | 17.5 | 13.8 | 14.4 | 9.6 | 10 | 8.9 | 9.4 |

| Three-teacher | 16 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 11 |

| Four-teacher | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 40 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 10 |

| LaGrange | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 15 | 45 | *18 |

| Kinston | 0 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

(1) To Spelling in each of the first three grades the one-teacher school devotes an average of 9.3 minutes, while the Pink Hill Consolidated School devotes an average of 18.3 minutes daily, or exactly 100 per cent more time.

(2) It will also be seen from this table that while the one-, two-, three-, and four-teacher schools devote an average of from 12 to 15.2 minutes daily to this subject in the first three grades, the LaGrange and Kinston schools devote an average from 20 to 22 minutes daily to this subject in these same grades.

| TABLE 5—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Arithmetic. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 15 | 14 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 14 | 15 | 15.7 |

| Two-teacher | 21.8 | 18.3 | 20 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 17.5 | 16 |

| Three-teacher | 16 | 19 | 20.8 | 20 | 21 | 23.7 | 26 |

| Four-teacher | 15 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 25 | 25 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 50 | 40 | 70 | 30 | 30 | 60 | 30 |

| LaGrange | 30 | 45 | 60 | 90 | 100 | 45 | 45 |

| Kinston | 20 | 15 | 30 | 38 | 30 | 40 | 40 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen that in the time devoted to the teaching of Arithmetic the one-teacher school is again the laggard in the race; that while it devotes on the average only 15.7 minutes daily to this subject in the seventh grade, the Pink Hill consolidated school devotes on the average 30 minutes daily, or 100 per cent more time. And if we compare the amount of time given to this subject daily in any one grade in the one-teacher school with the amount of time given daily to this subject in the same grade in the Pink Hill school, the difference in time is quite noticeable.

On the average the two-, three-, and four-teacher schools are devoting from 18.3 to 20.3 minutes each day in each of the first three grades to this subject, while the LaGrange school is devoting an average of 45 minutes daily, or an average of more than 100 per cent more time. And yet here and there are unthinking parents who really think they think that a three- or four-teacher school can accomplish for their children all that is necessary; that in these schools the teachers should be required to teach ten and eleven grades of work. When they have a three- or four-teacher school they feel that they have practically a university in their midst.

| TABLE 6—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Geography. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11.7 |

| Two-teacher | 0 | 0 | 18.6 | 17 | 16 | 14.4 | 14 |

| Three-teacher | 0 | 0 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 19 | 21.5 |

| Four-teacher | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 0 | 120 | 20 | 30 | 125 | 30 |

| LaGrange | 0 | 30 | 0 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 30 |

| Kinston | 0 | 0 | 25 | 30 | 20 | 45 | 45 |

(1) While the one-teacher school devotes on the average only 11.7 minutes daily to Geography in the seventh grade, the Pink Hill consolidated school devotes on the average 30 minutes a day, or more than 150 per cent more time.

(2) While the two-, three-, and four-teacher schools devote to this subject in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades an average of from 15.8 to 20 minutes daily, the LaGrange school devotes an average of 38.3 minutes daily, or nearly 100 per cent more time.

| TABLE 7—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to History. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 12.4 | 12 | 12.8 |

| Two-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 17 |

| Three-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 20 | 17 |

| Four-teacher | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 0 | 120 | 15 | 130 | 130 | 125 |

| LaGrange | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 45 | 40 |

| Kinston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 132 | 40 |

(1) To the subject of History in the seventh grade, the one-teacher school is devoting an average of 12.8 minutes daily only, while the Kinston and LaGrange schools are devoting on the average 40 minutes a day, or more than 300 per cent more time, and for a school term 50 per cent longer.

(2) While the two-, three-, and four-teacher schools devote on an average from 17.5 to 20 minutes daily to this subject in the fifth and sixth grades, the LaGrange school is devoting on an average of 42.5 minutes daily, or practically 100 per cent more time, and for a school term 36 per cent longer.

| TABLE 8—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Physiology, Sanitation, or Hygiene. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 12.5 |

| Two-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Three-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 16 | 16.8 | 18 |

| Four-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 130 | 130 | 0 |

| LaGrange | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kinston | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 215 | 0 |

From the above table it will be seen that the LaGrange school and the Kinston school are devoting time to this subject of Physiology or Hygiene in one grade only. The LaGrange school is teaching this subject in the fifth grade only. It is quite probable that these two schools are not giving all the time to this important subject they would like to give, or as much time as this important subject demands. Of course, it is impossible for the rural schools under their present organization to give all the time to this subject that ought to be given to it.

| TABLE 9—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Agriculture. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12.5 | 10 |

| Two-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| Three-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 16 | 0 |

| Four-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 130 |

| LaGrange | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Kinston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

When we consider the fact that Lenoir County is largely a rural county, and that the majority of the children are country children, it must appear self-evident from the above table that none of the schools of the county, whether urban or rural, is giving all the time that it should to this subject, whether we consider it from the standpoint of nature study in the primary grades or from the standpoint of agriculture in the upper grammar grades.

| TABLE 10—Showing Average Number Minutes Given Daily to Civics. | |||||||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Two-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Three-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Four-teacher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pink Hill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 125 |

| LaGrange | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 |

| Kinston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen that the Kinston school makes no provision for the teaching of Civics in any one of the elementary grades. This, however, may be due to the present over-crowded condition in the schools, and the necessity for running a double shift each day. This subject is too important to be omitted from the program of the elementary school.

(2) It will also appear quite evident from the table above that none of the schools of the county is giving to this subject the time its importance demands.

SUMMARY(1) From the foregoing tables in this chapter it must seem self-evident that from the standpoint of the amount of time devoted each day to Reading, Writing, Spelling, Arithmetic, History, and Geography, the one-teacher schools of the county are the unmistakable laggards in the race.

(2) To Reading in the first three grades the Pink Hill consolidated school is devoting nearly 100 per cent more time each day than does the one-teacher school; to Writing and to Spelling nearly 100 per cent more time.

(3) To Arithmetic in the seventh grade the Pink Hill school is devoting daily nearly 100 per cent more time than does the one-teacher school: to Geography more than 150 per cent more time; to History nearly 300 per cent more time, and for a school term 33⅓ per cent longer.

(4) To Reading in each of the first three grades the LaGrange school is devoting daily 100 per cent more time than the two-, three-, and four-teacher schools; to Writing and to Arithmetic nearly 100 per cent more time.

(5) To Geography in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades the LaGrange school is devoting daily nearly 100 per cent more time than do these two-, three-, and four-teacher schools; to History and to Arithmetic in these grades approximately 100 per cent more time, and for a school term 36 per cent longer.

We have omitted in this chapter the discussion of the relative amounts of time devoted by the various schools of the county to the teaching of Agriculture, Physiology or Hygiene, and Civics, not because these subjects are not essential to efficient citizenship, but rather because the time devoted to them in all the schools of the county is not enough to make a comparison of the relative amounts of time devoted to them especially significant. We have confined our comparisons largely to the relative amounts of time devoted to the three R's because these subjects constitute a large part of the bill of fare common to all the schools, big and little, in the county.

In the tables included in this chapter we have not included the subject of Music, because the teaching of this subject appears in the elementary school program of only three schools in the county: Kinston, LaGrange, and Pink Hill. We have not included Manual Training or Domestic Science because these subjects do not appear upon the elementary school program of a single school in the county.

CHAPTER V

ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS ATTENDING

SCHOOL AS REGULARLY AS THEY SHOULD?

| TABLE 11—Showing— | ||||||

| Revised School Sensus, 6-21 | Total School Enrollment | Average Daily Attendance | Per Cent of Revised Census Enrolled | Per Cent of Enrollment in Daily Attendance | Per Cent of Revised Census in Daily Attendance | |

| One-teacher | 644 | 503 | 307 | 78 | 61 | 47.67 |

| Two-teacher | 1,620 | 1,315 | 800 | 81.1 | 60.8 | 49.4 |

| Three-teacher | 685 | 596 | 352 | 87 | 59 | 51.39 |

| Four-teacher | 139 | 118 | 85 | 84.9 | 72 | 61.15 |

| Pink Hill | 440 | 401 | 256 | 91.1 | 63.8 | 58 |

From the above table it will be seen that the fifteen one-teacher schools enroll 78 per cent of their revised school census and keep in daily attendance only 47.67 per cent of this census. On these two points it will be seen that the one-teacher school ranks the lowest among the different types of schools in the county.

ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS OF THE COUNTY UPTO THE STATE'S STANDARD IN WHITE RURAL SCHOOL ATTEND-

ANCE?

| TABLE 12—Showing— | ||||||

| Revised School Census, 6-21 | Total School Enrollment | Average Daily Attendance | Per Cent of Revised Census Enrolled | Per Cent of Enrollment in Daily Attendance | Per Cent of Revised Census in Daily Attendance | |

| County | 3,528 | 2,933 | 1,800 | 83.1 | 61.37 | 51 |

| State | 468,761 | 398,036 | 290,573 | 84.9 | 73 | 62 |

From the above table it will be seen: (a) that while the 42 white rural schools of the county enroll 83.1 per cent of their total revised school census, the State's standard is 84.9; (b) that while the 42 rural schools of the county keep in daily attendance only 51 per cent of their revised census, the State's standard is 62 per cent; and (c) that while the rural schools of the county keep in daily attendance only 61.37 per cent of their actual enrollment, the State's standard is 73 per cent of its enrollment.

AVERAGE NUMBER OF DAYS ATTENDED BY EACH PUPIL IN THERURAL SCHOOLS, IN LAGRANGE, AND IN THE STATE FOR 1921-

1922

| TABLE 13—Showing— | |||

| Average Length of School Term | Per Cent of Enrollment in Daily Attendance | Average Number Days Attended by Each Pupil | |

| Lenoir County | 136 days | 61.37 | 83.46 |

| LaGrange | 180 days | 60.9 | 139.4 |

| State | 130.6 | 73 | 95.3 |

From the above table it will be seen: (a) that the average number of days attended by each pupil in the rural schools during the school term was 83.46; (b) that the average number of days attended by each pupil in the LaGrange school was 129.4; and (c) that the average number days attended by each rural pupil in the State was 95.3.

TOTAL NUMBER OF DAYS ATTENDED BY EACH INDIVIDUAL PUPILIN THE RURAL SCHOOLS, AND BY EACH PUPIL IN THE LA-

GRANGE SCHOOL

| TABLE 14—Showing— | ||||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent | ||

| Rural | 2,909 | 219 | 7.5 | 301 | 10.3 | 357 | 12.2 | 420 | 14.4 | |

| LaGrange | 420 | 15 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 20 | 5 | |

| 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent | 160 to 180 Days | Per Cent | |

| Rural | 582 | 20 | 769 | 26.4 | 125 | 4.4 | 146 | 5 | ||

| LaGrange | 33 | 8 | 13 | 3 | 19 | 4 | 39 | 9 | 249 | 59 |

From the above table a few striking comparisons will be observed. It will be seen: (a) that while three per cent only of the LaGrange school enrollment do not attend school beyond 20 days; 7.5 per cent of the rural school enrollment do not attend school beyond 20 days; (b) that while only four per cent of the LaGrange enrollment attends school from 20 to 40 days only, 10.3 per cent of the rural school enrollment attend school from 20 to 40 days only; (c) that while five per cent only of the total rural school enrollment attend from 140 to 160 days, 39 per cent of the LaGrange pupils attend from 140 to 160 days, and more striking still is the fact that while not a single pupil in the rural schools attended from 160 to 180 days, 249 pupils or 59 per cent of the LaGrange enrollment attended school from 160 to 180 days.

| TABLES 15-19—Showing the Enrollments, the Number and Per Cent of the Pupils Attending School for Various Numbers of Days in the Different Types of Rural Schools for 1921-1922. | ||||||||

| 15—ONE-TEACHER SCHOOLS | ||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent |

| 500 | 45 | 9 | 60 | 12 | 77 | 15.4 | 76 | 38 |

| Total Enrollment | 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent |

| 500 | 109 | 21.8 | 133 | 26.6 | ||||

| 16—TWO-TEACHER SCHOOLS | ||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent |

| 1,228 | 106 | 5.3 | 146 | 11.8 | 131 | 10.7 | 181 | 14.8 |

| Total Enrollment | 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent |

| 1,228 | 251 | 20.4 | 366 | 29 | 23 | 1.8 | 24 | 1.9 |

| 17—THREE-TEACHER SCHOOLS | ||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent |

| 575 | 51 | 8.9 | 81 | 14 | 67 | 11.7 | 86 | 15 |

| Total Enrollment | 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent |

| 575 | 121 | 21 | 141 | 24.5 | 16 | 2.8 | 12 | 2 |

| 18—FOUR-TEACHER SCHOOL (MOSS HILL) | ||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent |

| 127 | 6 | 4.7 | 6 | 4.7 | 8 | 6.3 | 16 | 12.6 |

| Total Enrollment | 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent |

| 127 | 31 | 24.4 | 38 | 30 | 22 | 18 |

| 19—PINK HILL CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL | ||||||||

| Total Enrollment | 1 to 20 Days | Per Cent | 20 to 40 Days | Per Cent | 40 to 60 Days | Per Cent | 60 to 80 Days | Per Cent |

| 391 | 21 | 5.27 | 25 | 6.4 | 55 | 14 | 47 | 12 |

| Total Enrollment | 80 to 100 Days | Per Cent | 100 to 120 Days | Per Cent | 120 to 140 Days | Per Cent | 140 to 160 Days | Per Cent |

| 391 | 36 | 9.2 | 62 | 15.8 | 51 | 13 | 94 | 24 |

The above tables do not make allowance for the 71 pupils of the county's enrollment that moved from one school to another school during the school term, but these pupils are considered in the totals in Table IV.

SUMMARYI. School Census, Enrollment and Attendance in the One-Teacher Schools

(1) There is doubtless common agreement that one important test of the efficiency of a particular school or system of schools is the per cent of its revised school census the particular school or system of schools enrolls.

(2) Of their total revised school census (6-21), of 644 pupils, the fifteen one-teacher schools enroll 78 per cent only, thereby leaving 22 per cent of their actual school population untouched, and uninfluenced in their daily process of educating and training boys and girls for future citizenship in the county. In meeting this particular test of efficiency these one-teacher schools score three points below the two-teacher schools, nine points below the three-teacher schools, practically seven points below the four-teacher (Moss Hill) school, thirteen points below the Pink Hill consolidated school, and six points below the standard for the State. Therefore on these counts it must appear conclusive that the one-teacher schools of the county stand at the foot of the ladder.

(3) A more important test still of the efficiency of a school or system of schools is the per cent of its revised school census the school or system of schools keeps in daily attendance. For it is self-evident that it is not simply getting the names of all the children on the revised school census on the school register that is going to guarantee either to the community or to the county an educated and efficient citizenship. This will be accomplished only in proportion as the school or system of schools enrolls every child on the revised school census, keeps every one of them in daily attendance, and gives them instruction that is most worth while.

(4) Of their total revised school census, these fifteen one-teacher schools keep in daily attendance less than 48 per cent, nearly 2 per cent less than the two-teacher schools, nearly 3 per cent less than the three-teacher schools, nearly 13.5 per cent less than the Pink Hill school, and 14 per cent less than the State's standard for rural schools. Therefore it must again appear plain that in meeting these two important tests of efficiency, the per cent of its revised school census enrolled, and the per cent of this revised census in daily attendance, the one-teacher schools stand at the bottom of the ladder.

(5) But not only is the inefficiency of the one-teacher schools unmistakably seen in its failure to meet the two tests indicated above, it is still further seen in the average and total number of days attended by each pupil during the session.

(6) In total number of days attended by the pupils in the one-teacher school, as will be seen from table, approximately 20 per cent of the total enrollment,

or one out of five attended school during the school term from 1 to 40 days only, whereas in the four-teacher school only about one out of every ten pupils went to school for so short a period, while in the LaGrange school only one pupil out of 14 attended for so short a time.

Therefore in meeting tests of efficiency so far as determined by the per cent of school census enrolled, school census in daily attendance, and total number of days it keeps each pupil in school, the wayfaring parent cannot rank his one-teacher school very high in the scale of efficiency.

(7) During the school term of 1921-22 there was a movement of 72 white pupils from the school they first entered to some other school in the county. In this movement 4.4 per cent of the entire enrollment in the one-teacher schools moved, and 77.3 per cent of those moving from these one-teacher communities moved into communities with more than one teacher. In this movement the one-teacher communities lost nearly twice as many as they gained. This large per cent of those moving going into communities with more than one teacher may have been merely a happen so. It is more likely, however, that it was a result of deliberate choice on the part of the parents of these children. For it is a common observation that more and more intelligent land renters, as well as those seeking to buy land, are considering quite carefully the advantages offered by the school before either renting land or buying a home in the community. Hence a good school with enough well trained teachers to give the children not only first-class advantages in the common school branches, but high school advantages as well, is proving a valuable economic asset to the community.

II. Enrollment and Attendance in the County System of Rural Schools(1) The acid tests of efficiency that apply to the individual schools apply with equal force to a system of schools.

(2) The 42 white rural schools of the county with their revised school census of 3,528 pupils enroll 83.1 per cent, and this is 1.8 per cent below the State's standard. And this means that approximately 17 children out of every one hundred are not even enrolled in the rural schools of the county.

(3) Of this total revised school census, these 42 schools are keeping in daily attendance only 51 per cent or 11 per cent below the standard for the State. This means that approximately only one pupil out of two who should be in school every day is actually in school every day, whether it be a six, seven, or eight months school.

(4) In the per cent of their total enrollment in daily attendance, the rural schools of the county score only 61.37 per cent, 11.63 per cent below the State's standard for rural schools, and 19.5 per cent below the score made by the LaGrange school.

(5) In the average number of days attended by each pupil in the Lenoir County system, the average number of days for each pupil is only 83.46, or 11.9 less than the average number of days attended by each pupil in the rural schools of the State, and 46 days less than the average number of days for each pupil in the LaGrange school.

(6) In the total number of days attended by the pupils in the rural schools of the county, as will be seen from Table XIV, approximately 17.8 per cent of their total enrollment attend school from 1 to 40 days only, while in the LaGrange school only 7 per cent of the enrollment attend school during the session for so short a time.

(7) While not a single pupil in the rural schools of the county attends school beyond 160 days, 59 per cent of the entire enrollment of the LaGrange school attends school from 160 to 180 days. Of course it may be said on behalf of the rural schools of the county that since none of them run for more than 160

days, it would therefore be impossible for the county children to attend school beyond 160 days. But this fact simply serves to emphasize still more clearly the inequality of educational opportunity offered children living in different sections of the same county.

(8) But it is quite probable that farmers too often mnimize their ability to send their children to school for an eight months term. The facts are, however, that when they have a good school and are fortunate enough to secure good teachers they will and do send their children to school for an eight months term. The Contentnea school is a clear illustration of this point. This is a two-teacher school right out in the open country, the children attending this school are the children of land renters and land owners. This school this year has two good teachers. They are interested in their work, are interested in the children and in the community. The school runs eight months or 160 days. The records show that 40 per cent of the children attend school from 140 to 160 days. A larger per cent of the children attended this school from 140 to 160 days than attended from 100 to 120 days in the other two-teacher schools of the county that run for the six months term only.

(9) Notwithstanding the commendable fact that the average length of rural school term of the county is approximately six days only less than the average for the State, yet the facts remain that when we apply to the forty-two schools in the county system the acid tests of efficiency in the per cent of school census enrolled, in the per cent of school census kept in daily attendance, in per cent of school enrollment in daily attendance, in the average number of days each pupil is being kept in school during the session, we find them failing at nearly every one of these points to measure up to the standard of the State as a whole, or to the level of the LaGrange school.

The serious consequences of irregular attendance do not end with the disorganization of classroom work, in handicapping the regular pupils in their progress through the grades, in wasting years of school life of those who attend irregularly, or even in the economic waste of having the teacher teach year after year the same thing to the same pupils. When we consider the fact that seventeen children out of every one hundred in the revised school census are not even enrolled during the school term; that about only one out of every two of this census attends school regularly, and that one out of every five enrolled does not go to school beyond forty days during the term—when we consider these facts, then it is self-evident that this enrollment and attendance of pupils in the rural schools is a matter of concern not only to the child, the teacher, and the welfare officer, but should be a matter of serious concern to the community and the county itself. For it is doubtless true that the future adult illiterates in the county will be found among these seventeen out of each one hundred on the revised school census who are not being enrolled: and in this group made up of one out of each five enrolled who are not going to school beyond forty days during the term. And it is quite natural to believe that the majority of those of the coming generation who will most stoutly oppose all progressive measures in whatever form they may come, whether local or county-wide, will be found among this seventeen per cent not being enrolled, this one out of five now not going to school beyond forty days during the term, and the forty-nine per cent that attend school irregularly.

Causes of Low Enrollment and Low Percentage of Attendance. Aside from sickness and the physical disability of the children, the question naturally arises: What is the relation between low enrollment and poor attendance and a teaching force 33 per cent of whom are without teaching experience, with only one out of ten a college graduate, with one out of every four below high school graduation, with only one per cent teaching in the same school for more than the third year, with daily classes per teacher ranging from 32

in the one-teacher schools to 15 in the Pink Hill school, with an average number of minutes for each class ranging from 11.3 minutes in the one-teacher schools to 22 minutes in the Pink Hill school, and with an average annual salary ranging from $398.76 in the one-teacher schools to $747.92 in the Pink Hill school.

To the extent to which the particular items in the above question are responsible for the percentage of school census enrolled, and kept in daily attendance, it must seem self-evident that the only permanent relief can come through a progressive, constructive, county-wide coöperative policy, through making the county the absolute unit in educational endeavor.

CHAPTER VITRAINING, EXPERIENCE AND ANNUAL SALARY OF

RURAL TEACHERS AND THE TEACHERS OF KINSTON

AND LAGRANGE SCHOOLS, 1921-1922

I. ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS BEING TAUGHT BY

WELL EDUCATED AND WELL TRAINED TEACHERS?

| TABLE 20—Showing— | ||||||||||

| Type of School | College Graduate | Three Years in College | Two Years in College | One Year in College | Graduate of High School Only | Completing 10th Grade Only | Completing 9th Grade Only | Completing 8th Grade Only | Completing 7th Grade Only | Total |

| One-teacher | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Two-teacher | 3 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 38 |

| Three-teacher | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Moss Hill | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Pink Hill | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Totals | 9 | 1 | 8 | 19 | 26 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 85 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen: (a) that of the fifteen teachers employed in the one-teacher schools of the county, not one is a college graduate; (b) that only four of the number have attended college, while six of the number, or 40 per cent, have completed a course no higher than the tenth grade.

(2) In the nineteen two-teacher schools there are three college graduates only of the 38 teachers; fourteen, or 37 per cent, are graduates of high school only, while approximately 24 per cent have completed a course not beyond the tenth grade.

(3) In the six three-teacher schools only one of the eighteen teachers is a college graduate, while 33⅓ per cent have not completed a course beyond the tenth grade.

(4) In the four-teacher school (Moss Hill) only one of the teachers is a college graduate, while three of them, or 75 per cent, have not completed a course beyond the tenth grade.

(5) Not until we reach the Pink Hill consolidated school with its ten teachers do we observe a marked change in the academic and professional training of the teachers. In the Pink Hill school 80 per cent of the teachers are either college graduates or have attended college, while not one of the ten fails high school graduation.

II. ARE THE TEACHERS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS AS WELL EDU-

CATED AND WELL TRAINED AS THE TEACHERS IN KINSTON OR

IN LAGRANGE?

| TABLE 21—Showing— | ||||||||||

| Type of School | College Graduate | Three Years in College | Two Years in College | One Year in College | Graduate of High School Only | Completing 10th Grade Only | Completing 9th Grade Only | Completing 8th Grade Only | Completing 7th Grade Only | Total |

| Rural | 9 | 1 | 8 | 19 | 26 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 85 |

| Kinston | 22 | 0 | 22 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 |

| LaGrange | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen (a) that only 9 out of the 85 white rural teachers, or less than 10.6 per cent, are college graduates; (b) that 22 out of the 54 Kinston teachers, or about 40.7 per cent, are college graduates, and that in the LaGrange school 53.8 per cent are college graduates.

(2) While the academic training of 25.9 per cent of all the rural teachers, about one out of every four is below high school graduation the academic training of all the 54 Kinston teachers is above high school graduation, and that in the LaGrange school the academic training of one teacher only does not extend beyond high school graduation.

But the question may naturally arise as to the reason for this marked difference in the education and training of those who teach in the rural schools of the county and those who teach the children in Kinston and LaGrange. The answer to this question does not lie in the unwillingness of the county board of education, the county superintendent, and the school committeemen to provide for the country children teachers equally as well trained as the teachers in Kinston and LaGrange. The reason lies rather in the very nature of the situation which they have to face.

III. ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS BEING TAUGHTBY EXPERIENCED TEACHERS?

| TABLE 22—Showing— | ||

| Years of Teaching | Number | Per Cent |

| None | 28 | 33 |

| One | 14 | 18.5 |

| Two | 13 | 15.3 |

| Three | 13 | 15.3 |

| Four or more | 17 | 20 |

| Total | 85 |

(1) From the above table it is seen (a) that 28 of the 85 rural teachers, or 33 per cent, were without teaching experience when they began the sessions work; (b) that 13 or 15.3 per cent had had two years of experience only, while 55, or approximately 65 per cent, of all the rural teachers of the county had taught for less than three years when they began the session's work.

When we recall the amount of academic and professional training possessed by the rural teachers of the county and add to this the lack of teaching experience on the part of such a large per cent, the problem of guaranteeing efficient instruction to all the rural children of the county becomes a serious one.

IV. ARE THE TEACHERS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS OF THE COUNTYAS EXPERIENCED AS THOSE TEACHING IN THE KINSTON AND

LAGRANGE SCHOOLS?

| TABLE 23—Showing— | |||||||||||

| Type of School | Number Without Teaching Experience | Per Cent | Number With One Year's Experience Only | Per Cent | Number With Two Years’ Experience Only | Per Cent | Number With Three Years’ Experience Only | Per Cent | Number With More than Three Years’ Experience | Per Cent | Total |

| Rural | 28 | 33 | 14 | 16.5 | 13 | 15.3 | 13 | 15.3 | 17 | 20 | 85 |

| Kinston | 5 | 8.8 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 10.5 | 35 | 61 | 57 |

| LaGrange | 3 | 23 | 1 | 7.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 69 | 13 |

(1) From the above table it will be seen that while 33 per cent of all rural teachers were without teaching experience at the beginning of the session, only 8.8 per cent of the Kinston teachers were without teaching experience.

(2) While only 20 per cent of the rural teachers had taught for more than three years, 61 per cent of the Kinston teachers and 69 per cent of the LaGrange teachers had taught for over three years.

(3) From the evidence here presented two facts stand out: (a) that in the rural schools of the county the percentage of inexperienced far exceed the percentage of inexperienced teachers either in LaGrange or Kinston; and (b) that the percentage of teachers in the rural schools with more than three years of teaching experience falls far below the percentage of the teachers in Kinston and LaGrange who have taught for more than three years.

It is quite possible that several of the splendid teachers now in the Kinston and LaGrange school did their practice teaching out in these rural schools, and as soon as they had time to prove their real worth as teachers Kinston and LaGrange heard about it and invited them to come up. They accept. No one can blame them.

V. ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS BEING TAUGHT BYTHE SAME TEACHERS YEAR AFTER YEAR?

| TABLE 24—Showing— | ||

| Number of Consecutive Years in Same School | Number of Teachers | Per Cent |

| Second year | 17 | 22⅔ |

| Third year | 16 | 21⅓ |

| For more than third year | 1 | 1⅓ |

(1) From the above table it will be seen (a) that of the 75 white rural teachers outside the Pink Hill consolidated school, which has but recently been formed, only 17, or 22⅔ per cent were teaching in the same school for the

second consecutive year; (b) that only 16, or 21⅓ per cent were teaching in the same school for the third consecutive year; and (c) that only one teacher out of the 75, or 1⅓ per cent, was teaching in the same school for more than the third year.

The necessity for keeping a good and growing teacher in the same school for at least several consecutive years is unquestioned.

Until the county board of education is in a position to provide for the country child the same teacher for several sessions in succession, the teacher, strong in personality, strong in the power to teach, strong in the spirit of community service, who is growing from year to year, both as a teacher of the children and worker in the community, it will be unable to build up in the county an efficient system of rural schools or render a very constructive service in the building up in the county a rural citizenship that is progressive, efficient and happy.

VI. WHAT IS THE AVERAGE ANNUAL SALARY PAID THE RURALTEACHERS AND THE TEACHERS IN THE ELEMENTARY DE-

PARTMENT OF THE KINSTON AND LAGRANGE SCHOOLS?

| TABLE 25—Showing— | ||||

| Average in Local Tax Districts | Average in Non-local Tax Districts | Total Average | Length of School Term | |

| One-teacher | $ 448.33 | $ 349.19 | $ 398.76 | 118 days |

| Two-teacher | 525.09 | 403.50 | 464.29 | 127 days |

| Three-teacher1 | 515.56 | 457.00 | 486.28 | 132 days |

| Four-teacher1 | 500.09 | 500.09 | 140 days | |

| Pink Hill | 737.92 | 737.92 | 160 days | |

| LaGrange | 859.44 | 859.44 | 180 days | |

| Kinston | 1,184.14 | 1,184.14 | 180 days |

(1) From the above table it is seen (a) that the average annual salary of all white teachers in the fifteen one-teacher schools, including both local and non-local tax districts is only $398.76 for a school term of approximately 120 days, or an average monthly salary the year around of only $33.23. For these teachers do not cease to live at the end of a school term of 120 days; they are doing their level best to live for 365 days in the year. It would be interesting to know how they do it. It is rather difficult to see how a teacher can board and clothe herself, buy the needed professional books, attend a summer school to prepare herself for better work, take a vacation of eight or ten days, pay her church dues, all out of a monthly salary of $33.23. Is it surprising that under these circumstances these teachers cease to grow as teachers and soon become afflicted with the hardening of the professional arteries? It may be that there is an inseparable relation between this average annual salary of $398.76 and the fact that there is not a college graduate among the fifteen teachers in the one-teacher schools, between this salary and the fact that only four of these fifteen teachers have ever attended college, and between this salary and the further fact that 40 per cent of the teachers in these one-teacher schools have never finished a course beyond the tenth grade.

(2) In the two teacher schools in both local and non-local tax districts the average annual salary is only $464.29 for a school term of 127 days, or a monthly salary the year round of $38.69.

(3) From the foregoing table it can be seen that the average annual salary of all teachers in the one-, two-, three- and four-teacher schools is $462.35 or a monthly salary the year round of $38.69, or only five dollars more per month the year round than the salary received by the teachers in the one-teacher schools.

(4) In the Pink Hill consolidated school the average annual salary is $737.92 for a school term of 160 days, against an average salary of $398.76 for the teachers in the one-teacher schools, and against an average salary of $462.35 for all the rural teachers outside of Pink Hill. And this salary of $737.92 paid to the Pink Hill teachers doubtless accounts in large measure for the fact that while less than 7 per cent of all rural teachers outside of Pink Hill are college graduates, in the Pink Hill school about 40 per cent are college graduates; and that while approximately 30 per cent, or nearly one out of every three teachers in all the rural schools have not completed work above the tenth grade, there is not a single teacher in the Pink Hill school whose scholarship falls below high school graduation.

(5) From the foregoing table it will also be seen that the average annual salary of the teacher in the LaGrange school is $859.44 for a school term of 180 days, and that the average annual salary of the teachers in the elementary department of the Kinston school, including that of the elementary principals is $1,184.14 for a school term of 180 days. And this average annual salary of $859.44 in the LaGrange school and the average annual salary of $1,184.44 in the Kinston school against a total average annual salary for all rural schools, including Pink Hill, of $517.47 has doubtless a great deal to do in determining the fact that while only about 10 per cent of all the rural teachers in the county are college graduates, 54 per cent in the LaGrange school, and 46.7 per cent of all the teachers in the Kinston school are college graduates; that while 26 per cent of all the rural teachers about one out of every four is below high school graduation, not a teacher in either the LaGrange or Kinston school is below high school graduation; that while 33 per cent of all rural teachers are without experience, only 23 per cent in the LaGrange school, and only 8.8 per cent in the Kinston school are without experience; and that while only 20 per cent of the rural teachers had taught for more than three years, 61 per cent of the Kinston teachers and 69 per cent of the LaGrange teachers had taught for more than three years.

Since it is quite evident from the facts presented here that there is this close relation between the education, training and teaching experience, and the amount of annual salary they receive, the conclusion seems unavoidable that the one big problem standing between the country children and efficient instruction for them is the serious problem of lengthening the school term, investing more money in the teacher and securing more efficient service as a result. But the serious question that must tax sorely the mind of the progressive school committee with their small taxable wealth, and their comparatively small school fund is the question of providing, under the present district plan, sufficient money to invest in the service of a capable and well trained teacher, even if they levy a local tax up to the limit of the law.

CHAPTER VII

ARE THE PUPILS IN THE RURAL SCHOOLS READING,

SPELLING AND WORKING ARITHMETIC AS WELL AS

THEY SHOULD?

I. FINDING THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PUPILS IN THESE

SUBJECTS

1. IMPORTANCE OF READING, SPELLING AND ARITHMETIC IN THE ELEMENTARY GRADES.

2. PURPOSE OF EDUCATIONAL TESTS.

3. SCOPE OF THE SURVEY.

4. THE SEVEN-GRADE ELEMENTARY COURSE.

5. AGE-GRADE DISTRIBUTION.

1. Importance of Reading, Spelling and Arithmetic in the Elementary Grades. A large part of the elementary school work is given to the development of the ability to read, spell and work arithmetic. This procedure is justified by the fact that these subjects are fundamental in elementary education. They are such important tools in civilized life that the success or failure of a boy or girl is to a great extent determined by his or her proficiency in these basic studies. And again, a pupil who is not well grounded in these fundamental subjects cannot make progress in the work of the higher grades. Especially is this true of the subject of reading as the progress of the pupil in all subjects depends upon his ability to read understandingly. The work of the elementary school is not a success unless it is so organized and the course of study so administered as to result in the development of the ability to read, spell and worth arithmetic and so enable the child through this achievement to develop his various powers and abilities to the extent that he may become a growing useful citizen.

(a) The results obtained in the teaching of reading is a good index to the work of the primary grades, and the degree of success attained may be approximated by the standards reached. If the pupils are taught to read with ease and fluency and understand what they read, the work of the grades is usually rated very high, while on the other hand if the pupils read poorly the work as a whole is considered a failure for the reason that reading is the most important subject taught in the primary grades. The first grades spend practically the whole of the school day, and the other primary grades spend a large per cent of the time in learning to read. This fact emphasizes the relative importance of reading when compared with other subjects taught in these grades. If the teaching of reading is a failure in the first three grades, it always makes advanced instruction very difficult.

(b) The ability to read and understand simple prose of the type found in school readers and in the text-books on informational studies such as history and geography, becomes increasingly important in the grammar grades. The pupil in these grades must have the ability to grasp quickly the thought in a paragraph, a chapter, or a book as this is one of the biggest contributing

factors to success and determines to a large extent the progress and development of the individual among his fellow men and has a great deal to do with his happiness for a lifetime. Without this essential equipment to get on in the world he is handicapped in making progress in any phase of life.

*“No single occupation rests so heavily upon the public schools as that of teaching the young people of the State to read the English language, the language of American politics and government, the language of American commerce and industry, the language of American literature and of American social ideals. No achievement in other fields will compensate for failure here, and no mere knowledge of the simple words and sentences of the primary school readers will suffice. Young people should master the words and the language structure involved in English sentences and paragraphs which are necessary to mature thought.”

The chief purpose then in the teaching of reading in the public schools is to train pupils to interpret the printed page, to train in thought-getting from books, magazines and papers.

(c) Effective communication is forever hampered unless the pupil can spell accurately ordinary words commonly used, which are at the same time the foundation words of the English language.

(d) Daily experiences of the child outside the classroom and ordinary business transactions demand that he be able at least to add, subtract, multiply and divide with speed and accuracy, and to reason out simple problems.

2. Purpose of Educational Tests. Little satisfaction, however, can be gained from the fact that pupils can read, spell and work arithmetic as the most important questions concerned with the whole of elementary education are, how well can pupils read, spell and work arithmetic, and whether or not they accomplish as much as they should in these subjects. In order to answer these questions accurately and definitely it is necessary to find out what each individual pupil has achieved in these subjects and to compare this achievement with acceptable grade standards. Educational tests are recognized as the best means for measuring pupil achievement, and they also furnish standards which should be attained by the average pupil in good schools. This report is an attempt to state the method of procedure in the use of educational tests to find out how well the boys and girls of Lenoir County read, spell and work arithmetic, and to present facts necessary to show whether or not they are accomplishing what they should in these important school subjects.

3. Scope of the Survey. The tests used were selected from among those which have been most carefully prepared and most widely used. They were given under uniform conditions and the scoring and tabulating all done by the examiner in charge or under the close personal direction of the one in charge in order to insure absolute fairness and accuracy. A battery of tests was given in all of the grades from the fourth through the seventh in the forty-two rural schools of the county and in the LaGrange and Kinston schools. In this way, giving these tests in all types of schools, the data secured are as complete and as inclusive as it is possible to secure in a testing program of this kind. Every pupil in attendance in these grades in the forty-two rural schools and in the LaGrange and Kinston schools was examined with four or more tests during the time between February 24th and April 7th, all (except a few) being tested during the four weeks of March. This was very near the