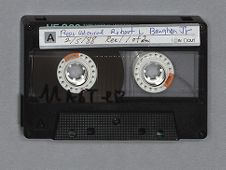

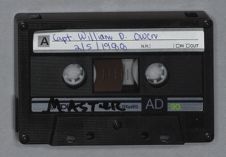

| EAST CAROLINA MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #95 | |

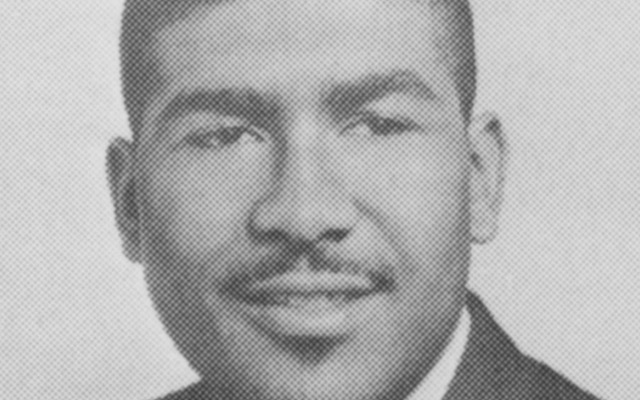

| Rear Admiral Robert L. Baughan, Jr. | |

| USNA CLASS OF 1941 | |

| February 5, 1988 | |

| Interview #1 |

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were born in West Virginia--did you spend most of your youth there?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes. I grew up in Huntington, West Virginia. I began to think about going to the Naval Academy when I was a freshman in high school. However, I was not ready to handle all the academics involved in the entrance exams, so for six months I attended Randle's Prep School in Washington, D. C. A number of us went there before the time for exams. I had initially thought I was going to be in a competitive exam status, but my dad managed to obtain for me a second alternate appointment from our local congressman. That appointment proved to be the one that finally got me into the academy.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did the other people not pass the entrance requirements?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Actually, I never did find out; but getting that type of appointment with high school transcript simplified my exams considerably, cutting them from six to three and eliminating Ancient History, which I was having an awful hard time with.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What influenced you to head for the Naval Academy?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

I think it was the Depression situation--my family could not have afforded to send

me to college otherwise. Then there were a number of young men in town who attended and came back in their uniforms and began to do a little recruiting. I got to know a couple of them.

I was anxious to go. I had never seen the ocean before I left to enter the Naval Academy. It was a new and different experience.

One thought that I'd like to interject about was that my father, who was a certified public accountant, worked terribly hard to support our family during the Depression years. I was determined that I wasn't going to go into a profession where I had to sit behind a desk all day long. Now that I look back at my naval career, I find that I probably spent more time behind a desk than I did on the bridge of a ship.

Morgan J. Barclay:

We never know, do we?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

No, we don't!

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did you arrive at the Academy in 1937?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes. June 17, 1937. We had a full plebe year to become adjusted.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Would you just share with us some of the experiences at the Academy that stand out for you?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

The plebe year was a bad scene for a lot of my classmates. I guess they happened to run into some personalities in the upper class that didn't match theirs very well. My friends at home had alerted me as to what was involved. Also, the six months at Randle's had a little bit of the same aura of regimen. The upper class that I came into contact with were good people, and I had a very pleasant experience as a plebe. I had an opportunity after I had passed the entrance exams to spend a month at Randle's doing further prepping for the plebe year courses. The only course I had any trouble with there was an English course; but

it wasn't my plebe year, it was the next year. The plebe year academics didn't snow me under at all.

I guess one event that sticks in my mind while at the Academy was becoming acquainted with the sport of lacrosse. Very interestingly, the information I received was that no previous experience was necessary. That drew my attention. Then I found out that was a sales pitch and was not very accurate. Experience was very helpful in that sport. I met a fellow who had played lacrosse in high school in Baltimore, and he began to show me the ropes. He later became one of my roommates.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did the Academy have an actual lacrosse team?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes. They were the national champions in those days, winning over schools like Johns Hopkins and Maryland. There were very few other schools which sponsored lacrosse. Later on, Virginia, North Carolina, and others got involved. Most all the eastern schools have lacrosse teams now. I never got beyond the "B" squad because of my lack of experience that "wasn't necessary!"

Morgan J. Barclay:

They were going to recruit you no matter what.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Well, I enjoyed it. It had a lot to do with my physical development, which was really just beginning to peak in those days. The workouts were very good. That was about the only sport that I got involved with.

Another one of my roommates led me into the Boat Club, which proved to be one of the outstanding "boondoggles" at the Naval Academy. There were some motor launches which had been converted into ketches with cabins equipped with bunks. Midshipmen were privileged--with proper qualification--to check these out over the weekend and sail them all around the Chesapeake Bay. That was a fine outing, particularly during the spring

and summer. Then there was also the opportunity to take the young ladies out on a one-day cruise. That was always a very interesting operation.

I was also involved in the musical club; I've forgotten now what they called it, but the midshipmen used to put on various performances. One in particular that I recall was Gilbert and Sullivan's "H. M. S. Pinafore." Those of us who had less heavy beards ended up being the "sisters and the cousins and the aunts."

Morgan J. Barclay:

You took a little harassment from that?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Oh, sure. However, the highlight of my Naval Academy career was performing well enough to be given command of one of the twelve companies during my last year. That last year, as you have found out already, was quite unusual in that it went only for half a year before we graduated. The normal routine of having one set of commanders for a third of the year, and then another set, and then, selecting from those two the third set for final graduation, did not come about. We had one set of commanders. My command was a great satisfaction to me. A month before we graduated, we went to Washington and marched in the 1941 inaugural parade of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. That was his third inauguration after being re-elected in 1940. It was cold and rainy, and we were in overcoats that became sodden; but it was something to remember, particularly with a certain young lady I had become so fond of being in the crowd and watching me.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Having the command experience was good.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

It was. The summer before--our first class summer--because of the war in Europe. We couldn't make our cruise in the eastern Atlantic. Instead, we went to the Caribbean and ended up in New York City during the World's Fair. I was appointed to command one of the midshipman companies that marched in the parade. We had maybe half a dozen

companies. I guess that experience helped me get my company command later that year. Marching in that parade was an interesting experience, too.

Morgan J. Barclay:

The class was unusual in the fact that the graduation took place in February. Was there any sense that the war was coming? What was the feeling at the Academy? Was it really strong at that point?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

I don't think that it was that strong. We were conscious of the tension with Japan but we were very confident with the U.S. Navy's capabilities. I can't say that we were eager to get out to the Fleet so much as we were eager to get out of the Naval Academy.

There is a book called On the Treadmill to Pearl Harbor. It covers the experience of Admiral James O. Richardson who was the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. He didn't get along very well with President Roosevelt, although he was very pleased with the president's shipbuilding program. He was pressing hard to get more officers and men assigned to the Navy and he kept telling the president that we were not going to have enough people to man those ships properly on a wartime footing unless he increased the allowance. The admiral finally made his point. It was interesting for me to read that it was in about May or June of 1940 that the decision was made to accelerate the officer intake program and graduate my class ahead of time. I had always wondered how that came about. There is a lot of good history in that book.

Morgan J. Barclay:

I hope we have it in the library, but I'm not sure. After graduation, where was your first assignment?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Five of us from the class went to the aircraft carrier LEXINGTON--the first LEXINGTON, CV2--which was in the Pacific. When I heard my ship assignment, I asked one of the aviators at the Naval Academy if he had served in the LEXINGTON. He looked

at me and said, "Young man, are you going to the LEXINGTON?"

I said, "Yes sir!"

He said, "Oh my! I put in three years in the LEXINGTON and three years in the SARATOGA and, without a doubt, they're the worst ships to serve in that I've ever been in." That didn't sound very exciting or encouraging.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did he say why?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes. He said, "In the summertime, they're the hottest ships in the Navy, and in the wintertime, they're the coldest; and every time they're at anchor, they try to turn over." Well, what he was referring to in the latter comment was the fact that most of the time when they anchored, it was off Long Beach (before the breakwater was built) or Waikiki Beach (before the carriers went into Pearl Harbor). These ships would moor at anchor and because of the high superstructure, they would "sail" themselves right across the swells, and then they would roll like the dickens out there in those heavy swells. To go aboard, you had to go up an accommodation ladder and into a doorway which was fairly low in the side of the ship. The poor ladies would come out in a motorboat to visit the duty officers and if they weren't careful, the ship would roll and the whole accommodation platform would go under water just as they were

stepping in or out of the boat. Many of them have memories of being wet up to their knees.

I found out what this fellow was talking about when I finally got to the ship; but by then new piers had been built at North Island in San Diego Harbor and the breakwater was going in at Long Beach. The LEXINGTON was actually one of the very first carriers to go into Pearl Harbor and moor to a pier. I never had to undergo very much of that roll experience, although occasionally we were out in a roadstead somewhere. All told, we new

ensigns had good oversight and training in that ship during the six months before the war started.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was your first duty assignment on the LEXINGTON?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

I began as a junior division officer because the senior division officers in the gunnery department were all officers of at least two years experience. Some of them, who were still ensigns, were about ready to become junior grade lieutenants. Each one of them had a number of junior ensigns as assistant division officers. As we came aboard, we were parcelled out to whoever needed some. We were fitted into the seniority among ensigns.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Which wasn't very high.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

No. It wasn't very high. I was about the fourth assistant junior division officer in the fourth division, and after several months I moved to the first division. It was just before the war began. The aide to the executive officer moved up to be assistant gunnery officer--he was a lieutenant junior grade at the time--so, I was interviewed and assigned to be the aide to the executive officer. It didn't change my gunnery battle station, but it did change my administrative routine quite a bit. We had about three thousand people on board including the aviation squadrons. Of that number, roughly twenty-seven hundred were people whose records were kept in the executive officer's office. The job included all the personnel work that went into that. I enjoyed it.

Shortly after the war started, the officer who was the ship's secretary, the aide running the captain's office, committed a serious blunder and was detached. On twenty minutes notice, I was told that I was going to take his place! That was a horse of a different color! He had custody of and was responsible for all the confidential publications--their inventory and control. We had four huge safes, about three feet on a cube, full of secret war

plans and all these confidential publications. Many of them were communication code pads. The code would change every month and the custodian had to issue those code pads out to the squadrons who then would give one to every aviator to put in his airplane to send coded messages back [to the ship] if he saw the enemy. That was a big headache.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That was a lot of administrative responsibility.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Right. After hearing I was going to be doing that in just twenty minutes, I told the executive officer, "I can't possibly inventory all of that in a proper turnover in twenty minutes!"

He said, "Well, you inventory it when you can, and we'll take care of any discrepancies thereafter." That didn't please me too much.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Shouldn't the inventory have been done before this fellow left?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Right! That would have been the normal turnover procedure. However, that proved to be of no real concern, because five months later the ship was sunk and all of the plans and pubs were in sixteen hundred fathoms of water at the bottom of the Coral Sea!

Morgan J. Barclay:

So you didn't have to worry about that.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

No.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How did you survive that situation that you were thrust into?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

I enjoyed being the ship's secretary because I had good qualified enlisted people and a warrant officer assistant. The name of the game was to check-in all the incoming and official mail and route it to the appropriate departments when action was required, we had a tickler schedule to be sure it came back answered, signed by the c.o., and logged out for mailing. That was kind of hectic during the war. The tempo of the official mail picked up considerably when we were in port. When we went to sea, we didn't get very much. That

left us time to cope with the size of the problem. But we would have twenty bags full of mail to deal with every time we got into port. One reason for this was because we were not in port very often. From Pearl Harbor down to the South Pacific, where we went on a couple of operations, we would be gone sixty days. We'd get some mail when we would refuel from a tanker, but we didn't have the airborne delivery system that the carriers have now.

The captain, Frederick C. Sherman, was a very fine example to follow. He was one of the most outstanding ship-handlers that I've ever had the pleasure to observe. He'd been in destroyers, submarines, and battleships before becoming an aviator. He would do things with that big carrier that nobody had ever thought of trying to do.

Morgan J. Barclay:

He had a real breadth of experience, didn't he?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

He had tremendous seamanship ability. It was fun to learn that sort of thing and it came in good stead later on. The gunnery officer insisted that I maintain my battle station and stand my gunnery watches, except in port when the mail load was so heavy. I was first at a topside station after and then finally at the one forward, the highest in the ship, 120 feet up from the water, where we had two gun directors controlling the five-inch guns.

We experienced our first enemy action in February of 1942, when we were attacked by eighteen Japanese twin-engine bombers down south of Rabaul. We had an opportunity to shoot back, but the fighter planes did the most damage. This was when the famous aviator from the LEXINGTON, "Butch" [Edward Henry] O'Hare became an Ace, shooting down five of those planes in one afternoon. The airport in Chicago is named for him.

Morgan J. Barclay:

While the American aviators were taking on the Japanese aviators, were you still being subjected to fire?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Oh, they were attacking us. They came in two waves of nine planes each. The main fighter opposition was against the first nine. In those days,the poor fighters pilots were having problems with machine guns that jammed, so by the time they were ready to go after the second group of nine, O'Hare was the only one who had guns that would operate. That's why he had so many opportunities.

The captain was on the wing of the bridge, watching the bombers as they approached. They weren't too high up so he could tell when the bombs were released. He would wait until they released the bombs and then he would put the ship in a tremendous wide turn. The bombs never came very close to us. Well, they fell in our wake and we could see them go off, but they were not what you would call near misses. One Japanese pilot, whose plane was damaged, tried to crash aboard. He got a lot of attention during the last part of his run. He crashed in the sea before he got to us, but he was fairly close.

The captain was so involved in turning the ship--doing figure eights and "S" turns--and watching the Japanese planes that he really wasn't conscious of what our airplanes were doing. After the first bomb drop had been evaded and he had steadied down on course, he said to the air officer, "We'll steady down so you can land some of the fighters and launch some more."

The air officer said, "Captain, we've been landing and taking off all the time!" Those were the days when the airplanes were slow enough that pilots had excellent control. They didn't require that the carrier deck be so steady into the wind, with the wind coming in at just the right angle. Also, they were motivated!

Morgan J. Barclay:

I'm going to backtrack a little bit. I remember reading that the LEXINGTON was out at sea when Pearl Harbor was attacked. Can you tell me about your reaction when you

saw the devastation at Pearl Harbor?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

We came back into port a week after the attack. It was appalling. Some of the ships were still smoking. Of course, there were all those battleships that were sitting on the bottom. I was still aide to the executive officer at that time. I had to go over to the base where they had a pool of personnel from those sunken ships. All the ships in peacetime had been operating with less than battle allowance, and I went over with our list of personnel shortages that we needed to fill to bring us up to battle allowance. We had our pick of what was available to fill our allowance. That day I didn't finish that chore until after dark. Everybody was still pretty jumpy around Pearl Harbor. There were sentries with rifles posted and challenging. I found it a very frustrating situation to be going out toward the ship moored at Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor, knowing that the sentries might challenge at any time. They were itchy enough, we were told, that if the challenge wasn't met right away and responded to, they might start shooting. There we were with the boat engine making so much noise that I was very concerned that we would never hear the challenge. The first thing we would know of one would be some bullets whizzing around us. However, we managed to get back without getting shot at. I think it was noisy enough that even the sentry realized what was out there. We went back into Pearl Harbor two or three times more during that spring of 1942 and they were still cleaning up.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When you were involved in that first conflict in February of 1942, did the LEXINGTON take any direct hits?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

None at all, no.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Maybe we can move ahead and describe the other conflicts you were involved in with the LEXINGTON.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

The Coral Sea battle occurred on May 7 and May 8, 1942. The task forces were pretty well aware of the fact that they were in proximity of each other, but neither knew where the other was. Each was looking for the other. On May 7, we had the advantage, because there was enough bad weather in our area for the admiral to keep our task force hidden. But our airplanes went out and found the Japanese. They sank a carrier and damaged another one. That was when the famous expression came back from our scouting squadron commander, Bob Dixon, "Scratch one flat top!" That got to be the rallying cry for war bond sales and things like that. We were at battle stations almost all day long.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You suspected you were going to find one another some time.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

The interesting thing was that in the milling around a group of Japanese aviators got lost. They couldn't find their carrier and they came across us. We were steaming along with the YORKTOWN and the Japanese thought we were their carriers. They attempted to land. Our captain said, "Don't do anything. Just sit tight." So, they flew by. They were trying to figure out whether or not they had clearance, I guess. Over on the YORKTOWN, they had itchy triggers, so when the planes came flying by to check them out, the crew on the YORKTOWN shot at them, causing them to vamoose.

Morgan J. Barclay:

If they had landed, you could have captured them.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

We told the YORKTOWN crowd later on, "You shouldn't have opened fire. You should have taken them aboard and bopped them on the head with a wrench."

Morgan J. Barclay:

It would have been interesting!

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

The next day, wouldn't you know it, the weather cleared off and it was beautiful. It was a typical South Sea sunshiny day. It is my recollection that it was about eleven o'clock in the morning when the Japanese came in at us. Our priority for targets was to take the

torpedo bombers first, then worry about the dive bombers. Our gunfire control systems could cope with the incoming low level torpedo bombers better. Our doctrine called for designating to the guns a target, but the planes split up wide enough so that it was difficult to do this. They made a good attack. It was very well coordinated. The dive bombers came in and got one or two small bombs on the ship itself. There were also a couple of large bomb explosives right alongside the ship. We think there were two torpedo hits. The way the ship bounced, it was obvious that we were badly damaged. But we kept moving right along and the damage control parties down in the ship were apparently coping with the damage, because they took the list off the ship. We were making twenty knots and landing aircraft, refueling them, and getting them ready to go back out. We were assessing the damage and taking care of the relatively few wounded before the fires started. The first gasoline explosion came about an hour and a half to two hours after the attack had been completed.

Before the war there had not been time to for the ship to be fitted with the fire prevention system that puts carbon dioxide on top of the gasoline in the fuel tanks when they're being emptied, which is where all the explosive mixture gathers. Apparently during the battle, the torpedo hits and near bomb misses opened the seams in the central part of the ship where the main electrical systems were. Fumes accumulated from the gasoline systems and eventually reached a point of ignition, probably being ignited by a spark from a motor generator. Once those gasoline fires started and spread in successive explosions, the damage control personnel couldn't cope with them. As the fires spread, the people down below had to leave their stations and come up topside. The smoke filled the engine room and the fire rooms. We had to shut down the boilers and, eventually, the ship came to a

halt. The pumps stopped and she heeled over to port. We had one or two destroyers come alongside to try to help with the fire fighting, but they couldn't really get hoses down into the damaged areas.

As the fires spread and began to approach the bomb magazines, it was obvious that we had lost the ship. Much against his wishes, the captain ordered the ship to be abandoned. The admiral had told him, "Get the people off the ship, Fred."

We had long since stripped the ship of all the big boats for wartime, but we had a lot of life rafts hanging all over the place. We had one destroyer alongside. The skipper of that destroyer had been one of the officers in the executive department at the Academy when we were midshipmen. You must have heard of Uncle Beanie--Uncle Beanie Jarrett? He was a favorite of our class and an honorary member.

I went to the executive officer and said, "I'm supposed to destroy all the publications and safes that are down there in the vicinity of the fire, what shall I do?"

He said, "Forget it! Go to your abandon ship station."

My abandon ship station was at the very bow of the ship. I went out there and assembled with my division. When the order finally came to abandon ship, people started going over the side. The ship was heeled over to port and the destroyer was still alongside of the starboard. The explosions were coming more and more regularly in the vicinity of the bomb magazine. To get aboard that destroyer, I would have had to have walked back, along the flight deck, over that area.

I thought, Well, if I go over the portside and the ship rolls over, that's not going to be good. So, I went down the starboard side from the bow, thinking that I would swim back to that destroyer and be picked up. We hadn't done very much in abandon-ship drills. I was

wearing a forty-five calibre pistol strapped around my waist. I had on my cap, my sunglasses, my graduation gift wrist watch (a brand new Hamilton that I was very pleased with), and a pair of seven-fifty binoculars around my neck.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were top heavy!

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Boy, was I ever! I had a life jacket, on of course, but the minute I slid down that rope and hit the water, my cap floated off, and my sunglasses disappeared. I cast loose my pistol and then I didn't have any trouble getting my behind up to swim because those binoculars were just like an albatross. I couldn't get anywhere very fast. As I went back toward the destroyer, a sudden, big explosion occurred on the LEXINGTON and the captain of the destroyer backed away and went around the stern. It looked like the nearest ship on my side of the LEXINGTON was a thousand miles away. Hearing the explosion, I decided, that the next best thing for me to do was to get some distance between me and the ship. I had attempted to save my watch from salt-water damage by putting it in my mouth. That didn't work at all! Fortunately, it had an expandable band and I was able to jam it back on and leave it to worry about in the future.

I did not make much progress. There was one other officer with me on that side of the ship and he was a better swimmer than I; however, he didn't seem to be getting any further away than I was. I realized that I was on the downwind side of the huge sail area of that big carrier, and there was just enough breeze to blow that ship after me faster than I could swim away from it. That was darn discouraging! Fortunately, a whaleboat came around the bow checking to see if there were anymore wounded to evacuate. The coxswain hauled the two of us in by the seats of our pants. We went alongside and got the last of the wounded. Then we went around the bow and found a cruiser where we embarked the

wounded on along with some of the boat crew who were getting tired.

The lieutenant, Bob Ward, took charge and we started trying to tow in the life rafts, which were floating around full of people, to the cruisers and destroyers. In the process, we got one of the tow lines wrapped around the propeller of the motor whaleboat. Lieutenant Ward went over the side with his bowie knife to cut it free and I thought he was going to drown before he succeeded. He got back in and told the engineer to "start up the engine." Well, it wouldn't start. It turned out that there had been so much evacuation that the boat had run out of fuel. By that time it was late in the afternoon; the sun was getting lower; and ships were beginning to disperse.

We started whooping and hollering and waving our arms. A boat on the way back to its own ship, the destroyer ANDERSON, after having deposited somebody in a cruiser, came by. The crew took us aboard and we ended up on the destroyer. It had almost as many survivors on board as it had crew. The captain was concerned about all that topside weight and the fact that he didn't have spaces below for all those people. We used the "hot bunk" system and also slept in the passageways for about two days.

The task force went into a port in the Tonga Islands where a couple of army transports had just arrived and discharged a load of army troops. The LEXINGTON survivors, who had been consolidated first in the cruisers, then were transferred to the transports, which went directly back to San Diego. I was in the BARNETT which was sunk later that year in the battle for Guadocanal Island.

The LEXINGTON, I don't think, would ever have sunk unless the fires had reached the main magazines and caused them to detonate. I think the fires would have burned out. The fires spread topside, setting the airplanes on fire and causing a huge pall of smoke and a

lot of flame. In order, to be sure she sank, that evening, the task force commander ordered torpedoes fired from one of our own destroyers. The ANDERSON was probably five or ten miles away when one of those torpedoes apparently hit the bomb magazine. We could feel the concussion throughout the ship.

That's where the confidential publications all ended up. My destruction report was very simple. I didn't have an inventory to refer to; I just had the transport send a message to the shore control office that said: "All publications issued to the USS LEXINGTON subsequent to (such and such a date) are hereby declared destroyed in sixteen hundred fathoms of water." I included the approximate location, but I didn't think anybody would go down there and hunt for them.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Was the LEXINGTON, during this air attack, attacked more than once?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Well, it was a rather coordinated attack on both carriers at the same time. They had the various waves arriving close enough that it seemed a simultaneous coordinated attack. I wasn't conscious of one wave after another. We looked for the next wave after they had finished, but it never came.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Weren't there very few losses relative to the volume of men? Wasn't it amazing how many survived?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

There were less than a hundred among the ship's company that were killed. We got all the wounded off, I am sure of that. I was glad that I was sure, because I had occasion a couple months later to visit the family of one of those killed. He had been from Detroit, and his mother had been told by somebody that he had been wounded and left aboard. I knew that wasn't true, because I had relayed the report of his death from our battle station down to the bridge. I don't know how much comfort that was. I hope it was some because that was a

grim thing for a mother to think about.

We were in San Diego for about two months. During that time, we were receiving orders and sending personnel to their new assignments. Primarily, I was involved in reconstituting the health records, pay records, and personnel records, of officers. I managed to get seven days leave and I phoned my bride-to-be, Eleanor Yount, in Norristown, Pennsylvania. Officers were beginning to get new assignments and some of the people in my category were being assigned to ships on the West Coast. I thought surely that's where I was going to end up; so I said to her, "If we're going to be married, you'd better come out here and we'll go to San Francisco and get married in my grandmother's church."

She got on an airplane and we had a fast engagement and an abbreviated three-day legal wait. Oakland wouldn't waive a bit of it but San Francisco would waive one day. We got back to San Diego the day of our wedding and were there just a month when I received orders to a destroyer on the East Coast.

Eleanor's father was a Lutheran pastor and her older sister had been married by their father in their church. All the sisters in that family had expected to have been able to do the same, but it was not to be for my wife. After going through several weddings, she decided that we did it the best way. Ours was very small and in a church but with little advance preparation.

In September 1942, after several schools, I reported as gunnery officer of a brand new destroyer being built in Quincy, Massachusetts. It was the USS CHAMPLIN, DD 601. We put her through shakedown that Fall and shortly after the North African invasion at Casablanca took place, we started escorting convoys across the Atlantic. The CHAMPLIN did that for most of the European war. She escorted to the British Isles, to North Africa, and

for the build-up of the invasion of Sicily. She also participated as a bombardment ship in the invasion of Sicily. Then we took our turn providing bombardment support on the west coast of Italy after the Anzio invasion. Finally, we participated in the invasion of Southern France. Periodically, we were getting back to the States as we escorted the convoys back. I was able to see my bride in Boston, New York, Massachusetts, and Norfolk. When it became obvious that most of our convoys were going to sail in and out of New York City, we found an apartment in Long Island. I never got back to the Pacific.

While I was in the Mediterranean on the CHAMPLIN, I received orders, which in those days were very cryptic, to report to the nearest Naval district for further assignment. They didn't want anyone to know where people were going. By that time I had fleeted up to being the executive officer of the CHAMPLIN. I thought, "Well, that means I'm going to go be an executive officer of a new destroyer going to the Pacific." I was much surprised when I was told that I was going to be the officer-in-charge of the five-inch gunnery school aboard the USS WYOMING, an old battleship that had been converted into a gunnery school ship. It was operating up and down the Chesapeake Bay, training the anti-aircraft gun crews for the new ships that were being built.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was this?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

This was April of 1945. Of course, that summer, the war in Europe was over but the kamikaze problem was still terrible in the Pacific. Because the WYOMING had one of every kind of gun-fire control and one of every kind of anti-aircraft gun found on Navy ships, which we could cross connect and control in different ways, we became an experimental gunnery ship. We set out to find the best combination of fire control system and gun that would handle the close-in attack of the kamikaze. That occupied us until after

the war ended. Then I was released to go to postgraduate training.

Morgan J. Barclay:

All during this time, you were basically experimenting with a combination to combat the kamikaze problem.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Right. I had become the assistant gunnery officer by then. We used radio-controlled drone aircraft as targets. They had just developed five-inch projectiles that had the VT fuse--radio-controlled fuse--to trigger them, but our target shells were sand loaded with just enough explosive to make a puff of smoke when the fuse was triggered. We could count the number of hits by the puffs of smoke without tearing the drone apart. We would put the drone out about five miles and run it in straight at the ship while shooting a hundred rounds at it with one system. Then we would try another system. We didn't have the rapid-fire three-inch battery aboard then, but besides the five-inch guns, we had twenty-millimeter and forty-millimeter guns. We fired a lot of rounds in the Chesapeake Bay.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That would have been an interesting assignment trying to come up with a combination.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

It really whetted my interest for ordnance engineering with a gunfire-control specialty. That's what I pursued in postgraduate training.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Tell me about the postgraduate training. Where was that?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

At the time, the postgraduate school was still located at the Naval Academy. It was not far from of the buildings where the midshipmen were. The Navy assigned, in that class of August 1946, a whole host of people who had been deferred because of the wartime effort to go into many different kinds of postgraduate training. The ordnance engineering group was the largest of any selected in many years. The students covered a lot of specialties, including some of the newer technologies such as guided missile guidance. The

faculty brought us up to snuff, so to speak, in basic electronics and mechanics, building on our Naval Academy curriculum, with all the new developments. After the first year most of us went off to civilian universities to complete the training.

Four other officers and I went to M.I.T. for the electrical engineering course there. We took a number of courses and did our thesis under Dr. C. Stark Draper, aeronautical engineer who was the who had developed the lead-computing sight and the gyroscopic system, which became the forerunner of the inertial guidance systems that we have in all the major missiles now. We had a very hectic two years there, trying to keep ahead of the workload. I finished in the summer of 1949.

I began to think of my next ship assignment, and I thought that surely I would be assigned as gunnery officer of a large ship--cruiser, battleship, or carrier. I was a little disappointed when I received informal notice that I was going to go back to be the exec of a destroyer again. I called the officer who made the assignments to check this out. He prevailed, saying, "With the mass exodus of officers and men after the war, the destroyers are not in a proper condition of readiness. They need experienced officers."

I accepted that and went off to be executive officer of the SHELTON DD 790, which had been built during the latter part of World War II. It was one of the newest destroyers we had at the time. I had a very interesting tour of duty aboard the SHELTON. We were in Subic Bay as part of the forward deployed force when the Korean War started in June, 1950. We were involved immediately. The squadron commander was embarked in our ship as his flagship. He was very senior, so he always became the commander in charge of the anti-submarine screen around the carrier force. Except for one or two very short instances that didn't amount to anything, we spent most of our time steaming with the

carriers up and down the east coast of Korea. We never saw the enemy at all. There were plenty of sonar contacts on schools of fish that would get us excited every once in a while.

The most exciting events that occurred were our periodic nighttime formation changes. One group of ships would be pulling out of the formation to go into port and another group would be coming in. It was pretty exciting in the dark! All the ships were darkened, all lights off. We did everything by radar. Fortunately, no collisions occurred.

The SHELTON was due back home, on a normal tour basis of six months, at Thanksgiving. However, the Navy was building up the fleet out there in the war zone and kept deferring our return. The new ships that would come out would be added to the fleet instead of relieving any of the existing ships. We were actually on our way the third time before we were allowed to keep going. Twice we started and were turned around. We didn't get home until after Christmas.

After returning in February, I received a promotion to commander and a new assignment to one of the destroyers that were being activated from the Reserve Fleet and re-commissioned, the PORTERFIELD, DD 682. That was a marvelous experience. As a new commanding officer coming right from the war zone, I knew exactly what we needed to concentrate on and prepare for. We didn't waste our time doing a lot of training that would not be of immediate use. He commissioned the PORTERFIELD in April and went back out to Korea in July for another tour.

Morgan J. Barclay:

That would have been in 1951.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes. The squadron was assigned to various kinds of operations. PORTFIELD'S endurance with the carriers wasn't as great as the SHELTON's had been, so we were assigned to do other things. Since I was next to junior captain in the division of four ships,

We received a lot of independent duty--shore bombardment on the west coast of Korea, shore bombardment on the east coast, and various odd jobs that relieved the monotony of just steaming with those carriers.

Morgan J. Barclay:

During the shore bombardment, did you take any hostile fire?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Yes, one time on the west coast. There was a swept channel that supply ships used, generally at night, to resupply some of the islands that had been captured off the west coast. They were sites for radar stations that had been set up for air warning. Our main mission was to protect those radar stations and the islands from being recaptured by North Korean forces. The mine sweepers would sweep the channel for the sampans that brought supplies. It was in the dead of winter and very cold, and the channel would ice over.

We had to go down South past one island one day to make contact with the task group commander, so I decided that enroute we would cut the ice for the mine sweepers. As we went by, we came within range of an enemy shore battery that had been quiet all the time we had been patrolling around there. They cut loose at us! This was just before we were scheduled to come home. One of their seventy-five millimeter shells hit the ship in the emergency radio room, top side, next to the number two smoke stack. Fortunately, there were just minor wounds to one person, that was all, but the shrapnel just riddled the stack. Stacks are big tubes with baffles arranged to channel the smoke out, and this shell perforated all the baffles in that stack. It had more holes in it than we could count. I didn't know whether the ship was going to be able to steam or not. However, on the way home we were able to make a full power run; but when we got to the shipyard, they looked at it and decided there was no point in trying to repair it. They took a stack from a mothballed ship and put in its place.

During the engagement we steamed out of range the shore battery and began to shoot back. They calmed down and didn't give us any more trouble. That was the only hostile action we encountered.

On another occasion we had our share of duty patrolling the Formosa Straits. In those days, the U.S. had an embargo on Red China ports, but we weren't stopping the British ships that were coming in and out because the British were participating with us in naval operations in Korea. It was a very peculiar situation. We were supposed to keep track of all those ships coming and going through the straits and identify them if possible. We were there also in case the Red Chinese decided to try to retake Formosa.

One night we saw a ship on the radar coming out of China, heading for Formosa, with no lights on. We went to investigate it and the most interesting little chitchat developed by blinker light. We queried the ship and it came back with the answer, "Friendly."

We asked, "What kind of ship?"

The answer, "Chinese. Friendly Chinese."We got in close enough to get a silhouette against the background illumination and could see that it was one of the landing ships that had been carrying supplies from Formosa to one of the Matsu Islands that they still held near the coast of China. I never found "friendly Chinese" to be a very satisfactory answer for identification purposes.

Morgan J. Barclay:

How long were you out there on your second tour in Korea?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

The first one, which kept getting extended, was nine months. The second one was seven months. We got back in February of 1952. The ship went to Hunter's Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco for overhaul and repair of the stack. I was relieved of that

command and assigned to the staff of the admiral who was in command of all the cruisers and destroyers in the Pacific Fleet. His flagship was a destroyer tender down in San Diego.

Morgan J. Barclay:

What was your assignment?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

My assignment on the staff of COMCRUDESPAC staff was that of ordnance maintenance officer. It was an excellent job. I was given quite a lot of independent decision-making authority to deal with any ordnance problems that the ships might have. I helped them with their gunnery training, but primarily in repair and maintenance, trying to solve design problems in the newer systems that were coming out.

When I had been the exec of the SHELTON, in 1950, we had received and installed two of those new gunfire-control systems. As we worked the bugs out, I had prepared reports from the ship, sent by the C.O. through the squadron commander, through the flotilla commander, to this staff to which I eventually was assigned. When I took over the staff position, I found, in some instances, those very reports still unforwarded in the pending basket that I had inherited with the job. At that point my task was to put on a recommendation and get the admiral to send them to the Bureau of Ordnance, in the Navy Department. Two years later, in the fall of 1954, I was assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance in that part of the bureau that handled those types of reports. By that time, I was in a position of having to deal with the budget, and I had to write back, "So sorry, can't do what you recommended; insufficient funds."

Morgan J. Barclay:

Your whole perspective changed after you moved up.

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

That's right. I was eager to put to some good use to the knowledge I had gained at postgraduate training, and I thought I was helping with all of this. Eventually, I discovered, when working in the Navy Department, these problems were pretty small potatoes. It was a

good learning experience and one that I've been through several times.

The duty on the staff in San Diego was very rewarding. We had, for the first time, a real family experience without having to move around very much. We bought our first home. I got reacquainted with my wife and sons. We had our third boy.

Then we went to Washington, where I started in the Bureau of Ordnance as a section head. After a year I fleeted up to being the branch head. Again, I was in that mystical world of gun- and missile-fire control, where I had a lot of independent decision-making authority, at least in those instances where the budget wasn't the controlling factor. It was a very rewarding experience there.

Also, during the time I was in the PORTERFIELD and growing through this Washington experience, I experienced a spiritual re-development.

One of my bombardment assignments in North Korea was to keep a shore-line railroad in a state of disrepair. The railroad ran through many tunnels along the coast and we could get at it in different spots. The workers hid in the tunnels and as soon as we would steam off, they would come out and fix it and get a train by it. The admiral in charge of blockade forces came by in his big cruiser, and showed me some intelligence photographs that identified a new block of housing over there. Intelligence sources had somehow found out that was where the railroad workers were housed.

He said, "I want you to shoot off the house tops over there. They can't occupy those quarters in the freezing weather if you mess them up. They can't fix the railroad if they don't have any place to stay warm."

He didn't much care if I killed all the workers either. That was the first time in my career I'd ever had a civilian target designated as a military target. It bothered me. I began

to ask myself and available chaplains questions about the meaning of this from a religious point of view. I had married this Lutheran pastor's daughter and had become active in church affairs whenever I could, and we were very much interested in bringing our kids up with a good religious background. Somebody finally steered me to a group called the Officers' Christian Union, which was made up of officers with serious Christian values and an understanding of the concept of a "Just War." Through contacts at various times with other officers of all the services, I began to have a spiritual development that went well beyond my childhood upbringing. I became even more active in church service when we moved to Washington, D.C. As this experience continued and developed, I felt that our family was really involved in the mainstream of Christianity as much as any military family could possibly be with the kind of duty I had. That, of course, was a major influence in deciding during my second career to go to a seminary and become a Lutheran pastor.

During the tour of duty in Washington, I had gotten into the frame of mind that I believed that the Lord was controlling my destiny and would determine where I would go on my next assignment. So, although I was personally acquainted with the officer who was then making the assignments, I didn't feel any need to pull strings and hedge around. Officers were required to submit an annual data card on which we filled out our preferences for next assignment to guide the "Detailer," as we called him. I wanted to go command one of a new class of destroyers. That was my first choice. My second choice was to be the executive officer of a cruiser, but I didn't think I was senior enough to be chosen for that. I was much surprised when this detail officer called me up one night--well after working hours had ended--and said, "I'm ready to dispose of your next assignment."

That didn't sound very promising! I hedged a little bit and said, "You have my

preference card there, you see my first choice."

He said, "Well, you've already had command of a destroyer!"

I said, "Oh, but that was an old one out of mothballs. It wasn't one of those brand new ones."

He said, "That's all that counts." So that was checked off.

He said, "I see your second choice. How would you like being the executive officer of a cruiser?" (That was a plum of an assignment!)

I said, "I would like that. What cruisers do you have available?" Then I thought that at that time of the night, he must have an emergency. Somebody was sick and a cruiser on the West Coast was ready to sail to Japan and he had to get somebody out there. I thought, "Lord, you're running this thing, what's it going to be?"

The ball came bouncing right back to me, "What cruiser assignment would you like?"

Wow! I had often wanted to go to the cruiser, whatever it might be, that was the flagship for the Commander of the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. At that time, that ship was home-ported in southern France and we could take our families over there to live. I said, "I may as well shoot for the moon! I'd like to be executive of the SALEM."

He said, "Okay, can you go in August?"

I said, "I sure can go in August." That was the next wonderful experience.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When was that?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

That was in August of 1957. We sailed on the SS CONSTITUTION a passenger liner, over to Nice. We had a little problem finding housing. As a matter of fact, my wife had to find it without me because there was an east Mediterranean crisis at that moment.

The ship was away from home-port and all the new arrivals were sent by air and ship to join up at sea. The ship didn't get back until Christmas time. It turned out to be not as good a family situation as was advertised, but we look back on it with fond memories.

The SALEM and her families came back in July 1958, and in the Fall of 1958, I was assigned to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (Op Nav) in Washington, D.C.. I was in a brand new billet newly promoted to captain, in a new branch that was overseeing the development of command and control systems using digital computers.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Did that involve guided missiles?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

No. For the shipboard units, those computers analyzed surface and air contact data and controlled the fighter aircraft. Primarily, it was operational control. My section had the responsibility for developing a computer system that would enable the senior shore-based commanders, in their command posts, to keep track of ships and aircraft and all manner of functions such as weather, target assignments, Antisubmarine Warfare, control of operating forces. That tour lasted three years. During the latter part of that time, I was on a special assignment as the military assistant to the new Special Assistant for Command and Control Systems to the Secretary of the Defense. Also, I was participating as a Navy representative in the development of the Joint World-Wide Command and Control System, linking all the Navy, Army, and Air Force command posts around the world. This was a big new project in the field of command and control.

The "Detailer" enticed me out of that very interesting work by offering me the command of a brand new guided missile frigate, DLG 16, USS LEAHY. It was a light cruiser-sized ship, the first of a new class with surface-to-air missile installations at both ends of the ship. It was a ship of latest design and development, and we called her "First of

the Double Enders." Having command for two years was a wonderful experience.

Morgan J. Barclay:

When did you take over the LEAHY?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

I was assigned as the prospective commanding officer and I reported into the building yard at Bath, Maine in April 1962. The ship was actually completed and commissioned in Boston in August of 1962. We spent a whole year working all the bugs out, particularly in the missile systems. The missile systems were some of the same ones that I had been responsible for purchasing back in 1954 when I was in the Bureau of Ordnance. Now they were being delivered and installed in these new ships, but by this time they had an upgraded improvement program that had to be installed with it. Of course, every new improvement had to be checked out by shooting missiles at drone targets. We spent a lot of time down on the missile range off San Juan, Puerto Rico, checking the ship out.

There were nine other ships with the same equipment. One of them was a nuclear-powered frigate, the BAINBRIDGE. Our first-ship test program went on for two years. It was important to try to keep the officers and crews together as much as possible until all the special work was done. The ship was finally home-ported the second year in Charleston.

After that tour of duty ended, I thought I was going to be assigned to the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, but another detailer said, "No, you're going to have the second half of your sea tour as a squadron commander." He was going to send me off to some other place.

I said, "Well, look. There's a squadron of ships home-ported right here in Charleston that's due for a new squadron commander. Why don't you assign me here and save the government some money?" As a result, we stayed in Charleston for another year. I

had command of Destroyer Squadron 6, which was comprised of six missile ships-two frigates and four destroyers. I went with half of them during that year for a five-month deployment to the Mediterranean.

Then I went to ICAF as a student in August of 1965, and finished in August of 1966, when I was assigned to the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon. I served in the Pacific division of the Operations Directorate, which was the outfit that was primarily involved with handling all of the build-up and strategic direction in Vietnam. As a senior captain, I was just another action officer there for the first year. Then, part of the second year, I was deputy director of that division.

After two years on the staff, I was expecting to be reassigned to the Industrial College as an instructor until I retired. Instead the selection board selected me for rear admiral, and I was due for reassignment in June of 1968. So I spent my third year on the Joint Chiefs of Staff as a frocked rear admiral, one of the admirals that are the senior duty officers directing watch teams in the National Military Command Center the command post in the Pentagon for the Joint Chiefs. That was a very unusual year. There were five generals or admirals heading up those teams. There must have been thirty-five people on each team. We were probably the highest paid watch-standers in the nation. We rotated watches, eight on, sixteen off, for six days. Then we would skip a couple of days and flip to the next duty watch, the next eight hours. It was very good duty, very informative. We were involved in some way whenever anything happened in the world, whether it was Peruvian gunboats shooting at tuna fishermen from San Diego or the Russians shooting down reconnaissance aircraft, which they did, unfortunately, rather frequently.

Morgan J. Barclay:

Were you responsible for handling crisis situations?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

We were responsible for gathering the data, presenting it with analysis to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of Defense, and anybody else concerned, and keeping the White House informed. The tour lasted one year. At the end of that year in July 1969, I went to my last sea-duty assignment: Commander, Cruiser-Destroyer Flotilla 9, home-ported in San Diego. At that time, the flotilla commanders in the States were responsible for helping to prepare and train the ships that were going out to serve in Vietnam waters in southeast Asia. The admirals themselves and their staffs would rotate, like the ships did, to Southeast Asia. In April 1970, I went out to take my turn, but I was only there for three months before my relief came along. My year of sea duty was over.

I came back to Washington to be the Vice Commander, Naval Ordnance Systems Command, which lasted about eighteen months. At the end of 1971, I was told that I would be the one to satisfy the Secretary of the Navy's desire for a flag officer to be a project manager of the major combatant shipbuilding projects. Admiral Frank Price was in OpNav, in charge of Surface Warfare programs and we worked together a lot on the shipbuilding programs.

Morgan J. Barclay:

This would be the shipbuilding for the Vietnam war?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

It wasn't specifically for the Vietnam war, but it was going on during the closing phases of that war. All of the new ships that you read about now were being designed or built then, like the STARK that was hit in the Persian Gulf or the big destroyers of the DD 963-Class that are over there now, and some of the new missile cruisers. All of those were either in the building or design stage.

Morgan J. Barclay:

You were overseeing them as they were built?

Robert L. Baughan, Jr.:

Each of the ship programs had a project officer who was a senior captain in the

Naval Sea Systems Command. At the Chief of Naval Material Command level, I was the project manager overseeing all of those and responsible to the Chief of Naval Material. I had a collateral duty as Chairman of the Shipbuilding Panel for CNM. For my last tour of duty, in 1974, I fleeted up and became the Vice Chief of Naval Material. I retired in September 1975.

Previous to retirement I had decided that I wanted to be involved with church work full-time. I thought about becoming a pastor but was encouraged to first take on a layman's position. For three and a half years, I served as the treasurer and administrative officer of the Central Pennsylvania Synod of the Lutheran Church in America, an organization like an Episcopal diocese. At the end of those three years, I was still hankering to become a pastor. I could see areas where I felt ministry needed attention and it was logical that people would expect an ordained person to do it. I asked the bishop if he would sponsor me

as a candidate for the seminary.He said, "Well, I hate to lose a treasurer, but if you find a good treasurer to replace you, I will sponsor you."

In the summer of 1979, I had to start the process by going through twelve weeks of clinical pastoral education in an institutional setting. The most readily available to my situation was at the Harrisburg State Hospital, which is a mental institution. I learned a tremendous lot about the mentally ill and about geriatric patients, whether they be mentally ill or not.

I began the seminary program in the fall of 1979 at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Gettysburg, PA. We had a lot of on-the-job training as well as academics. My second year included academics and a concurrent internship in a small parish of two

churches where there was no pastor. The overseeing pastor had a big church of his own in the same town and he said, "You go ahead and do your thing and if you have trouble, let me know." That was perfect for my situation.

In the spring of 1981, when I completed the certification requirements for ordination, that parish called me to be their pastor. I served there another three years until reaching age sixty-five. I asked the bishop then, "Shall I retire, or shall I look for another call? This place is in a growing area and it needs someone with a lot more energy than I have to devote to it."

He said, "No, you retire and we'll make use of you whenever you want to work."

Since that time, I have filled pastoral vacancies as an interim pastor five times. The process of a congregation going through self examination and calling a new pastor takes at least six months. The last one I had was for nearly two years. It's a reduced workload and a very nice continuation without having a lot of stress and strain. I have thoroughly enjoyed my second career, and I am truly enjoying my final retirement.

[End of Interview]

Reading this interview has triggered all kinds of reminiscing for me. Perhaps as unforgettable as anything was my having to inquire after a pilot for his name to be recorded in the Quartermaster's Notebook. Some ports were tricky to navigate and to be on the safe side the port authority provided 'pilots' who knew the harbors and could advise the Captain to ensure a safe berthing. A small craft would deliver the pilot to the ship and he'd be escorted to the bridge to the side of the Captain. I hated asking his name. Looking back, I'm sure I could have handled that small task better than I did: with some confidence and in a way that would have met with a more approving look from the Captain than my manner always seemed to call forth. The Captain's body language spoke volumes, as when he seemed to scold me with a facial expression for nearly missing the last boat back to the anchorage at Ocho Rios, Jamaica. His becoming a Pastor in the ELCA after retirement from the Navy doesn't surprise me a bit. So many memories for me within the few lines Rear Admiral Baughan gives to LEAHY. And the possibility all my perceptions are a matter of what seems to be the case and not what actually occurred.