Walter and Dorothy Auman Interview

| Interviewees: | Walter and Dorothy Auman |

| Interviewer: | Michelle A. Francis |

| Date of Interview: | February 22, 1983 |

| Location of Interview: | Seagrove, N.C. |

Michelle A. Francis:

[Today is February 22, 1983. We're talking with Dorothy] and Walter Auman in Seagrove, North Carolina. Dorothy, will you say your name?

Dorothy Auman:

Dorothy Auman

(Tape stops then starts)Michelle A. Francis:

Okay. Dorothy, we were gonna just start by talking about where you were born, and your parents and your background as a potter. And I'll just sort of let you start. Were you born here in Seagrove?

Dorothy Auman:

I was born about a half a mile down the road here, I guess.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is the place still standing? The homeplace?

Dorothy Auman:

No, the house was torn down not too long ago. My father was Charlie Cole, my mother was Ida Dunlap Cole, and they married and they had four children, three girls and a son. And I was the youngest of the family.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who were your sisters and brother?

Dorothy Auman:

My brother was Thurston Cole. My sister, oldest sister was Edith, and, then Lucy.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were your parents both potters?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, yes, they both worked in it. You know, a lot of people don't count a potter a potter unless you turn on the wheel, but, boy around here, we don't look at 'em that way. If they're out there making their living in it, they're a potter, let me tell you. (Laughter) It's just as important to grind that clay, or to sand that pot off as it is to turn it Don't you think, Walter?

Walter Auman:

Oh, yes! Because I do it, I guess. (Laughter)

Dorothy Auman:

Well, do you count Daddy any less of a potter than Thurston?

Walter Auman:

No, for he was the one that kept the shop together.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right. Uh, I think he was, uh, a greater of the two, and. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Your dad?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh, and Daddy did not get a chance to turn on the wheel.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was that by choice?

Dorothy Auman:

I don't think it was particular by choice, as it was by necessity. Just like Walter is by necessity, somebody has to look after all these other things. The turning is pure pleasure. That's like putting the icing on the cake, or, um. It's just pure pleasure. You know, it's just, the turning's not even, I don't even call it work.

Michelle A. Francis:

It's more like fun.

Dorothy Auman:

It is just pure pleasure. Now when you got to out there and get your clay, grind it up, get it ready for the potter to turn. Mm, now that's work. And then, you start in firing the kilns and putting the glaze on and. . .

Walter Auman:

. . .filling the kilns and emptying 'em. . .

Dorothy Auman:

.grinding the bottoms after it comes out. And now this is just the major headlines. You're, and then all day long you're running your legs off doing the little things that has to be done on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

So, your father ran the, sort of ran the shop, the pottery, as Walter's doing. Sort of doing those behind-the-scenes things that have to be done.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. As well as mixing the glazing and doing the firing of the kilns and this sort of thing.

Michelle A. Francis:

So who was throwing, or turning?

Dorothy Auman:

At my daddy's shop?

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum.

Dorothy Auman:

Well, my brother was the main turner there.

Michelle A. Francis:

Thurston.

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Where did he learn to turn?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, Daddy and Uncle Everett had a shop years and years ago, and, uh, Thurston really learned from that shop then.

Michelle A. Francis:

From your Uncle Everett?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah, and Daddy. See, Daddy was raised in the pottery. His daddy was a potter.

Michelle A. Francis:

Then he knew how to turn, he just didn't do it. He just wasn't turning.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah, that's right. He just, it, like, Walter can turn. It's just that he can't, uh, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

There's just not enough time to do it.

Dorothy Auman:

There's not enough hours in the day for him to get around to doing it.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did you dad and your uncle Everett have their shop? What time period are we talking about?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, at the time period that I was speaking of, when Thurston was first learning, was after Everett and Daddy' moved the shop over to New Hill. That was over on Number 1 so they could catch that north/southern traffic there. Um, and that would have been in the early '30s. On till, well, all through the '30s there.

Michelle A. Francis:

How old was Thurston when he, was he just a little boy, or a young man when he started turning?

Walter Auman:

Yes, he was a young man. He was very young.

Dorothy Auman:

I was just trying to think.

Walter Auman:

He was born in 1920, wasn't he?

Dorothy Auman:

14. Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

He was born in 1920?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh. So by the time he was 14 and 15, he was turning, is what I am trying to, trying to think of a date that he was able to turn. By the time he was 16 he was a pretty good turner. He was, you know, considered along with the other young people, oh, you take Wayman and all, you take, uh, Melvin and all them. You know, considered him a turner.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's Wayman Cole and Melvin Owens.

Dorothy Auman:

Right. Uh, he was considered a turner at that time. But Everett stayed and turned also.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was Everett's, who was your granddaddy. Who was Everett's and your father's, Charlie's father?

Dorothy Auman:

Ruffin Cole.

Michelle A. Francis:

Ruffin?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh. And his father was Evan Cole--Ibbin Cole we'd call him. And, uh, Evan is the one that had such a large pottery at one time. He had all of his family plus part of his wife's family working with him. And he had, he had really a big operation at one time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Whereabouts was that located?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, right about the county line, down here.

Michelle A. Francis:

County line? What's the road number on that? Do you know?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, it's off of 705.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is there anything still standing?

Dorothy Auman:

No, uh-huh, not a thing there. But, then, my two sisters worked what time they's at home, you know. They married and left and got out of it, but when they was at home, they worked at the shop. Everybody that was there worked. And as I grew up, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

When were you born?

Dorothy Auman:

'25, 1925.

Michelle A. Francis:

What month?

Dorothy Auman:

June.

Michelle A. Francis:

June? What day?

Dorothy Auman:

Oh, okay. (Laughter) 8th.

Michelle A. Francis:

June 8th. What did your sisters, were they in the sales shop? Did you have a sales shop like this?

Dorothy Auman:

Not like this, no. It was a completely different set up back then. Back when, you almost have to go by periods. You can't say, "Back then, they did so and so," because in a 10-year period it would change, even. Just like it is today. You can almost say every 10 years you've got almost a new history to write.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, how was it when you were born? When you were just a little, tiny girl? Course, you probably don't remember, but perhaps you remember your parents talking about it.

Dorothy Auman:

Well, see I was born during the time that they were trying to change over from making the salt glaze to the lead glazes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Why were they doing this?

Dorothy Auman:

Because this is what sold.

Michelle A. Francis:

The lead glazes were selling? And the salt glaze was no longer selling?

Walter Auman:

It got to the point that glass was much easier to obtain and much easier to handle. Your glass jars and canning jars and storage jars, things like that, were in. . . And then, times were getting a little better, particular after the Depression, and the lady of the house, she was wanting more color in her house, and art pottery and, cooking, pie dishes and things like that. I think that was really the demand. There just wasn't the demand for the salt glaze after that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was there a lot of experimentation that went on with the new lead glazes?

Walter Auman:

Oh yes, very much. They was a lot of, lot of experimenting going on.

Michelle A. Francis:

A lot of rejects?

Walter Auman:

I guess most of the potters were, and still, they do a lot of experimenting with clays as well as glazes, trying to get something to keep up with the times.

Michelle A. Francis:

What sort of glazes did you all's, did your dad's shop start out with? The lead glazes.

Dorothy Auman:

Just like all the other shops. They all started with using the red lead and putting oxides in it to make, make different colors on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were popular? What seemed to sell the most with the public?

Dorothy Auman:

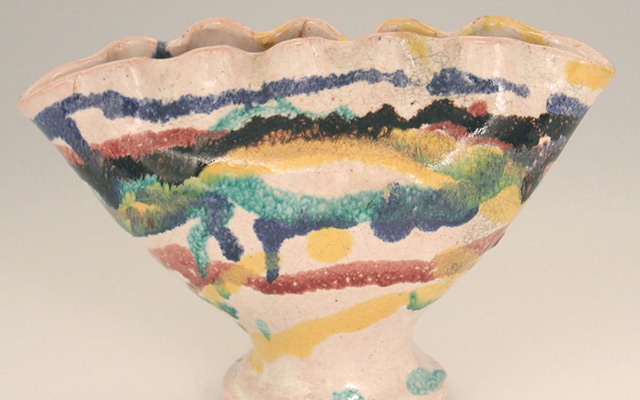

Well, the more colorful it was, the better people seemed to like it, you know. Your blues and your turquoises and your greens were your predominant colors, of course. There's always that striving for the reds, your tones of reds.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was that a difficult glaze to perfect, the red?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, it was. And the first man that ever even came, even had a hint of it, was really the, uh, Henry Cooper, down at North State. And, him and his wife started in making pottery and they hired this, uh, the Owenses. They hired Melvin and uh, what was his name down there that stayed with them?

Walter Auman:

Walter.

Dorothy Auman:

Walter Owens. To uh, to do the potting, really. And John, most of the Owens family. But anyway, they were acquainted with this chemical engineer over at State College, and he helped them get started on these glazes that was really a better quality than what the potters was experimenting on their own with.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did the Owens bring that knowledge back here to this community?

Dorothy Auman:

They certainly did! In fact, uh, one of the best glazes that he perfected down there that had this hint of red in it, it was called the Copper Red. The Busbee's picked it up and that's what has become known as the Jug Town. But it was not. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Jug Town, but it started at North State with Cooper.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right. It certainly did. And, this, yes, this knowledge did come back. Also, another family that did the same thing about the same period of time that we're speaking of--this is in the '25 to '35 period of time, nowwas Walter's people. They ran a shop just up the road up here called the Auman Potter. Charlie Auman really, the boy, was really the one that looked after that shop.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is that your brother?

Walter Auman:

No, it was just a cousin.

Michelle A. Francis:

Just a cousin.

Dorothy Auman:

He'd a been your daddy's first cousin, wouldn't it? But anyway, uh, a man from, he was from Philadelphia, wasn't he?

Walter Auman:

I believe he was.

Dorothy Auman:

He came down. Matheson. Would come down and spend about every summer with them, over there. And, they, too developed. He was a chemical engineer, and he developed some good things, and got, got people going, you know.

Michelle A. Francis:

What was Matheson's first name, do you remember, Walter?

Walter Auman:

I have no idea now. I don't even, I don't remember.

Dorothy Auman:

I can't recall it either. See, this is why we need to do homework. (Laughter) You ask a question, I can flip it over and say, "Oh, yes."

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, I can make a note of that.

Dorothy Auman:

My, uh, my memory just, my mind just simply has a lot of blank spaces on it.

Michelle A. Francis:

You're doing just fine. So, really, in the '20s and '30s when they started changing over to the lead glazes, there's a lot of experimentation that went on. Every pottery trying its own thing. But really the glazes were sort of perfected by outsiders.

Dorothy Auman:

Well, you know it had to be, anything that complicated. You just take a ordinary person, I don't care how well he had turned, or how many years he had spent in potting, he had to know chemicals and he had to know ceramic formulas. Alright, now, during this time, you understand that this wasn't just going on here at Seagrove. During this time, if you'll read back on your ceramic history, you'll find that Ohio was just going by leaps and bounds in that same direction. They were really putting in there. They were putting in art, what's known as the molded art pottery, figurines, all of this type of thing. Okay, they were large enough, this group of potters were. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

In Ohio?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, they were large enough to hire, first off, ceramic engineers. They were also large enough to support what we call chemical houses, or ceramic houses, who furnish you these materials. And they had, they had several, this is all they did, was experiment trying to figure out a glaze. When they found out something that worked, of course they put it out to the buying public, who would in turn buy their supplies from them. So, when you get right down to it, it was this industry, really, that developed your glazes. It wasn't the potters around here. You, not many people, old dodgers of a potter, out here, are just that smart up here, have that much book knowledge.

Michelle A. Francis:

Would your dad, and your family, then would they buy these glazes, lead glazes ready-made?

Walter Auman:

No, they just, they would buy the materials and mix them.

Dorothy Auman:

And they would tell them how to mix them.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay, the ceramic companies would tell them, give them formulas.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay. And then they would experiment on their own, because glazes react differently on different clays.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right. They was using your bought, washed, de-ironed clays which mold well. Whereas we were using the local, iron-filled clays, fresh-dug out of the ground. And the two comparisons was just, mm, two different avenues all together. Okay, we had to make their glaze formulas fit our bodies. And this was a constant, a constant testing and experimenting of new, of different clays, changing the formula, this sort of thing. And it's always been this way here. It's always been. Because when you're dealing with, when you go dig up your clay, you might dig a truck load or wagon load--at that time it was a wagon load--of one type of clay. And you'd dig on down six feet further in the vein and it's changed, chemical, chemical-wise. Maybe it's got less iron in it or less calcium in it or less something in it.

Michelle A. Francis:

And it's going to fire differently.

Walter Auman:

Then, too, everybody built their own kilns, and no two kilns fire the same. So that would, there was a difference in the, in the kilns' working conditions. So each one had to mix their glaze to match their clay as well as their kiln.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well then, if they were changing their glazes, they were probably changing their forms, also. Or did they keep the same, were they making the same dishes, the same pots, that they were before?

Walter Auman:

Well, when they changed from the salt glaze into the lead glazes, they did change forms, in a lot a, lot a cases. 'Course they still made their pie dishes and their cooking ware, things like that.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were some of the new shapes, new forms that your pottery, your parents' pottery?

Walter Auman:

It was your art pottery, your vases, and, uh, more decorative pieces.

Michelle A. Francis:

Uh, flower pots, was that considered, art pottery?

Walter Auman:

Yes.

Dorothy Auman:

Yes. Glazed flowerpots.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you do any sort of figurines, little animals or what have you?

Dorothy Auman:

There's always been that done.

Michelle A. Francis:

Has that always been?

Dorothy Auman:

That is called, what you were talking, called "folk art," I guess. It's not been done like in molds or anything, you just pinch out something. That's always been a fun part of this.

Walter Auman:

And used to, about every potter had a mold that they made smoking pipes. Everybody made a few, a few pipes. There wasn't, they didn't make a whole lot, but it was, everything was done by hand. But now that was before the '20, '25 to '35 period that we're talking of right now. By the '25 and '35 period, the cigarette had become the popular thing, you see. So, of course, ash trays was a new item that they made. The '25 and '35 period, uh, I think more size-wise, would have been more like we are today, isn't it. Don't you think, Walter?

Walter Auman:

Yes.[note]

Dorothy Auman:

Not any, not many pieces, now there's always exceptions to the rule. You'll find somebody would have glazed something about like a churn, you know, they would have glazed the churn. And we found them every once in a while, say a 5-gallon churn. But most of the pieces were like' larger vases, say 14-inch vases, from that range down to tiny miniatures, and along of course, with this little toy stuff that they called, toy stuff. This seemed to be what, of course, sold, you know. And of course, the bigger the piece was, the more glaze it took, and it was more expensive to make. And, if that big piece cracked, you lost so much. So, they sort of got away from that.

Michelle A. Francis:

Got away from making the larger pieces?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, like the churns, like the storage jars, like the salt glaze pieces. And went back to making, or went to making just smaller pieces.

Walter Auman:

Then in the early '40s, some of the potters picked up on the large pieces again, and started making the large pieces and they were transporting them to New York, Florida.

Dorothy Auman:

These were called "garden urns." Jardinieres, that type of thing. Thousands and thousands and thousands of huge pieces went down to Florida and were sitting, you know, outside.

Michelle A. Francis:

I understood why New York, there was a market in New York, because the Busbees were out there touting a lot of, you know, North Carolina crafts, including the pottery. But I never could, never understood why it was in Florida. Was it just the north/south vacation travel?

Dorothy Auman:

Well honey, (sigh). . .

Walter Auman:

They, they went everywhere.

Michelle A. Francis:

How did you get such a large market?

Walter Auman:

The Busbees didn't particular, uh. . .

Dorothy Auman:

. . .create a market for anybody but themselves. . .

Walter Auman:

. . .create a market. The market was already there.

Michelle A. Francis:

In New York?

Walter Auman:

Oh yes.

Dorothy Auman:

The market that the other potters were selling to was like Macy's, which, which the Busbees was doing this way on, you know, flumping their nose at it, saying, "Ha, ha!", you know. "We're selling ours to, um. . ."

Walter Auman:

Some tea room.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. Or, you know, art connoisseurs, this type of people. So, the market for them, was. .

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .totally different.

Dorothy Auman:

Entirely! It was, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

It was like two different markets in New York.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right. They were like Henry Poor and all of this type pottery, who was doing pottery at that time. It was in the art vein, there. The potters that was here potting, that was doing the bulk of the pottery, was still doing, I would still, it was utilitarian for '30s and '40s. Utilitarian for what it was for the purpose of the thing was.

Walter Auman:

Yes. Well, during that time, Coles, they were making a tremendous amount of large urns and they were transporting them to Tucson, Arizona.

Michelle A. Francis:

Tucson, Arizona?

Dorothy Auman:

Also, Chicago, to Marshall Field.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, how did they establish markets in these far-away cities? Did buyers come down here?

Walter Auman:

Yes.

Dorothy Auman:

They were looking for this type thing to go into their flower shops and their, their garden centers, that sort of thing. Okay, down here at Pinehurst is a resort where these people came, uh, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

To vacation?

Dorothy Auman:

Right. And, many of them stumbled, literally stumbled into this sort of thing. Pinehurst was saturated with pottery. They, they bought lots of pottery. They were a good market in that early period of time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Back in the '20s and '30s. Are we still talking '20s and '30s?

Dorothy Auman:

Um-hum. So, then as they, as the people becamesuch as, if Marshall Fields had something in Chicago--Macy's, let me tell you, knew exactly what they had, and they was gonna find out where it came from.

Michelle A. Francis:

So once the word got out that there was a marketable pottery in this area, then just good old competition took over.

Dorothy Auman:

Right. Uh-huh. That taken'd over then.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, who were you selling to in Florida? Who was buying in Florida?

Walter Auman:

Usually gift shops.

Michelle A. Francis:

Gift shops, like?

Dorothy Auman:

Garden centers. And at that time Florida was being developed to the extent of each home becoming an estate, you know, and having a garden that you walked through. And urns sitting around and statuary and this type of thing.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well do you remember the first pot you ever turned?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, I guess I've got the first pot that ever, that was any size, that ever came out. It's somewhere. Do you know where it's at?

Walter Auman:

No, I sure don't.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, you ought to find that.

Dorothy Auman:

(Laughter) It was a basket.

Michelle A. Francis:

A basket?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. And it was, I guess, the total thing was that tall, I guess.

Michelle A. Francis:

About 10 inches.

Dorothy Auman:

I imagine.

Michelle A. Francis:

What color was it?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh, sort of a blue-gray with a dabbling on the edges of different other colors, around the edges.

Michelle A. Francis:

How old were you?

Dorothy Auman:

I must to have been, uh, 'bout 11 or 12, I guess.

Michelle A. Francis:

Do you remember your first pot?

Walter Auman:

I remember my first sale of a pot. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

What did it look like?

Walter Auman:

It was, it was quite, quite a nice pot. I'd like to have it back. It was a lady in West Virginia bought it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was it a large piece?

Walter Auman:

It was quite a large platter, 'bout a 14-16 inch platter.

Michelle A. Francis:

How old were you?

Walter Auman:

Oh, I was, I don't know. I was in my twenties.

Michelle A. Francis:

Twenties. Did you start turning when you were very young?

Walter Auman:

No I didn't start turning until after I was up. Grown.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who taught you?

Walter Auman:

Oh, I guess I taught myself, with a little help from Dot.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you all married then?

Walter Auman:

Yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh, then you didn't learn till after you, after you'd gotten married.

Walter Auman:

No. 'Course I'd stayed around the pottery shop quite a bit, when I was, when my uncle operated the shop in Smithfield, and I stayed with them several year when I was small. And then I lived right close to Coles and I was in and out of the shop over there, so. I was familiar with the, with the pottery shop.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. You knew all the mechanics of, of pottery, then.

Walter Auman:

Oh yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Dorothy, did you teach yourself how to turn, just by watching your family, or did someone sit down with you and say, "Now this is step one."

Dorothy Auman:

Well, uh, you dabble in it and dabble in it and you're just fascinated to death. I've never seen a child that wasn't absolutely captivated with the wheel. We've got a granddaughter that's three years old and she can spend two or three hours right there standing on that chair on the, on the wheel. And that's, that's how it's always been, and that's the way it was with me. So, as I grew up, there was a thing about a potter and his wheel that was really funny, you know, back as I's growing up in the, say in the '30s there. We, today, we take our wheels I guess a little more for granted than they did theirs back then.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. They were using kick wheels then weren't they?

Dorothy Auman:

Mm-hum, yeah. And they were sitting on the precarious looking white flint stone rocks, you know, the center. . .

Walter Auman:

Shafts.

Dorothy Auman:

. . .shaft was. And if you moved that, if you stood on it, for instance, if a child would come up and stand on that big fly wheel over there, it'd scoot that thing off-center. So, for these reasons, I look back and realize why they were so snipity about letting me use their wheel. (Laughter) Well, it got to the point that I would slip out in theat noon, when they was eating dinner--man, I'd just turn as hard as I could turn, you know, on their wheel. Go back, and then Daddy had to listen to them fuss for two hours that, "Dorothy had done something to my wheel and it's not working right," you know. (Laughter) Okay, to eliminate that fuss, Daddy built me a wheel. And he built it so that the top of it, that I could stand on a sawed-off, it was a piece of wood he got out of the wood pile out there, and I could stand on it. It must have been nearly as high as this box, this stool here. I guess 10-12 inches. And he put the crank, the shaft that you peddle, up way high so that shaft had the little crook in it much higher than any other wheel did. But he made this especially for that. And, told me to stay off of their wheels.

Michelle A. Francis:

And so you had your own wheel.

Dorothy Auman:

I had my own wheel,.

Michelle A. Francis:

How old were you?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, I don't know. At that time I must have been about 10, I reckon.

Michelle A. Francis:

About 10. That must have pleased the other potters. (Laughter)

Dorothy Auman:

I didn't care whether it pleased them or not. It sure did me. (Laughter) And so, Daddy had an uncle of his, it'd been my great uncle, Uncle Wren, that had made pottery for years and years and had retired. His wife had died and he was living with a daughter, up towards Ulah up here. So, Daddy went up and talked to him and asked him would he come down and stay with me and help me get started. So he did. He came and stayed with me, and he wouldn't let me play much, you know, like I'd been doing. I was just sort of playing, you know, let it do what it wanted to do. If it wanted to flatten out and make a bowl shape. No, he says, "No, you've got to, if you make cups today now, you know, you make them all day long," you know. And that took a little of the. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Fun out of it?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah!

Michelle A. Francis:

He taught you some discipline, then.

Dorothy Auman:

That's what he was doing, yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

And then he was your own personal tutor.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. And now, he would turn, he would--Daddy fixed him a wheel and he and I were in the same room together. And then Everett and Thurston was in the old shop. But Daddy had built us sort of a shed off of the old shop there.

Michelle A. Francis:

So, when you were say, like around 12, there was you and Everett and Thurston and your uncle. . .

Dorothy Auman:

Uncle Wren.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .Uncle Wren turning.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. But, the turning was always such fun on it, but now the handling was always a chore. It taken me longer to learn to put a handle on than it did--to pull it out and the handle, you know, in production style, you know, fast, get it on, get it on out of the way there--than it did to learn to turn to body. So to me, when anybody comes here learning,

you know, I always tell 'em, that it took me a lot longer to learn the handle, so get started early, have lots of patience, and don't give up on 'em, you know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah. (Laughter)

Dorothy Auman:

I remember so well, oh, how flustrated I would get when I would put a handle on and it would crack and wouldn't know why, what I had done wrong. This sort of thing.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, were you turning pieces for sale, then? When you were in your early teens?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes! There was a big market for miniatures, and Daddy put me to turning these little miniatures about, what, a inch and a half high? Walter, how many--you've seen them being taken out of the kiln even, even then.

Walter Auman:

They were--you mean how many would come out of the kiln?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah.

Walter Auman:

Oh, we've taken out 7, 8 bushel basketfulls of 'em at the time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh my! Then there was a market for them.

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh.

Walter Auman:

Oh yes. Back in the '50s he was selling those for a dollar and a half a dozen.

Michelle A. Francis:

That seems so cheap.

Walter Auman:

A basketfull of 'em--to show you how small they were--they would run about a hundred dollars for the pottery in there, for a bushel basket full of miniatures.

Dorothy Auman:

So this was sort of what I did.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's what you started out, that was the first production requirement.

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh. And this was, as long as there was more than Thurston turning at the shop, this was what I was expected to do. Everett was in and out of the shop at various periods. He would work a while and then he didn't work a while. He's doing something else a while. During the periods that he did not turn, that he wasn't turning, then I would take over the next size, which we called the "half pound assortment size."

Michelle A. Francis:

Like a. . .

Dorothy Auman:

Mug.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .like a mug would be.

Dorothy Auman:

Um-hum. This size thing. And would help on that, but that was such a popular thing, too, until one turner couldn't keep up with that. So Thurston also turned on those, too. But I would help on those.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you go to school? Did you have time to go to school and turn, too?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, you went to school, but you went to work--came home and you went to work out, even if it wasn't but two or three hours out in the shop.

Michelle A. Francis:

So you worked every day.

Dorothy Auman:

Practically, yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Practically, even going to school.

Dorothy Auman:

Mm-hum. If you wasn't, say, when you came in and you went to the house to change your clothes, you know, if you wasn't back out there in at least 15, 20 minutes after you came in, somebody's at the house wanted to know what you's doing. (Laughter)

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, in an hour, how long would it, how many little of those miniatures could you turn in an hour? The little miniature things. Like if you came home in the afternoon and you just had an hour to work?

Dorothy Auman:

You could turn around 50.

Michelle A. Francis:

Michelle A. Francis:

You could get 50 out?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

That's, I guess that's what production pottery is all about. Being able to do it consistently and quickly at the same time.

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well then, would you also be responsible for glazing?

Dorothy Auman:

No, the turning was it. And putting the handles on, and seeing that the bottoms was trimmed.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you trim before you took off the wheel, or did you let it get leather-hard and then trim it?

Dorothy Auman:

Well both times, but a lot of times your chip will get what we call dull, and it will leave a little feather edge right around the bottom on it. Okay, the turner is supposed to take his finger and go over that. And usually you do that when you're handling it anyway. But then, as it was dried, Daddy always kept these big bowls in the shop, about this big around and about this tall, that had cracked, got chipped or something. It was bisque pottery, now. And these little miniature pieces, as they got dried, I'd just lay 'em over in these bowls and I'd keep the bowls filled of 'em.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, is that how you bisque-fired them, then? Would you just stick them in like that?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, in these bowls. Uh-huh. But then, as they came out, as Walter well knows (laughter), they were individually set, individually cleaned out. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Individually. That must take hours to load the kiln.

Walter Auman:

It does. It takes, it's really time consuming. But, you can cover several hundred pieces in a short time, after you get used to it.

Michelle A. Francis:

You can glaze. . .

Walter Auman:

Oh yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .several hundred in a short time?

Walter Auman:

Uh-huh. We glaze a kiln-full a day.

Dorothy Auman:

Now my sister Edith was as fast a glazer as you most ever saw on that sort. of stuff. She could put 'em in and take 'em out, boy, in just nothing flat.

Michelle A. Francis:

Well, would she dip 'em?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

Immerse 'em totally and then wipe the bottom off?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, uh-huh. That's right. And then you'd come along with a little brush and brush the bottoms so they wouldn't stick in the kiln.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. Brush 'em with a wax or. . .

Dorothy Auman:

No, a brush.

Michelle A. Francis:

Just a brush.

Walter Auman:

Just brush the excess glaze off.

Michelle A. Francis:

Oh. Do you set it on stilts?

Walter Auman:

We didn't then.

(Begin Side 2)Dorothy Auman:

Well, when the war came along. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

World War II, right?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah. Thurston was turning, 'course there at the house. And when he went off to war, it just left nobody but me there. Uncle Wren had died and Everett had moved to South Carolina.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did Everett set up a pottery?

Dorothy Auman:

No, not there.

Michelle A. Francis:

In South Carolina?

Dorothy Auman:

Everett got into making cement-type, yard-type things out of cement, and he was down there making, making that type of thing. But, during the war it was rough going, now, I'll tell you. We had two shops that absolutely closed up. Was, uh, Herman Cole's down at Smithfield and Royal Crowntwo large shops that just closed. Because it was so difficult to, number one, get help and number two, would be to get the ingredients that it took to make the glaze out of.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mm-hum. You were probably, what, about--you were born in '25--you were about 20. Were you about 20 when Thurston went off?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, let's see. In '42 I graduated from high school. So I was 16. It was just real hard for just, uh, me and Momma and Daddy was at home at that time, to produce enough pottery to hardly have a truckload to take it off to sell. Now all during this time, you depended on the gift shops in the resort areas, whether it was beaches or the mountains. It certainly wasn't in this area. Nobody never came to this area hunting pottery, you know. Or vacationing.

Michelle A. Francis:

You weren't getting a tourist trade then. You were shipping most of the pottery out.

Dorothy Auman:

So, it was a long time in between the times of getting it. We ended up, Daddy had some pretty good customers up around Gatlinburg that he knew, and they began coming for it. And this was the beginning, I guess the first of the times that they ever drove down to pick up the pottery themselves. And somehow or another we sort of hung on.

Michelle A. Francis:

The demand decreased some during the war years?

Dorothy Auman:

No, it didn't!

Michelle A. Francis:

No?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-uh. In fact, you see, they could not get imports of anything, so the gift shop owners were actually looking harder for local-made items. And so the demand actually increased. But there was just no way of producing it.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you dad start turning again, since it was short-handed?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh, he didn't turn. What he started doing was making little shoes as, uh, at that--you know I never hear of a shoe collector anymore? Do you Walter?

Walter Auman:

No.

Dorothy Auman:

Isn't that funny? I hadn't even thought about it. Today people, I've gone, I've known people that goes through these fads of collecting owls or bumblebees or strawberries or something, you know. But during this time, there was this craze for shoes.

Michelle A. Francis:

For shoes?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh. Little miniature shoes. Nothing anything larger than a inch and a half long.

Michelle A. Francis:

And so you dad went to making them? Hand. . .

Dorothy Auman:

He sure did. Well, he would model one out and then make him a mold and then pour, pour his liquid clay into the mold. And in some cases he'd press, he would roll his clay out very, very thin and then press it down into the mold. But, he did an awful lot of this. And, always around the shop

there was molds for various type bowls, oblong-type things. And I remember there was a dish garden dish, planter dish, that would have been 10 to 12 inches long, perhaps 4 inches deep, and it was scalloped up on the top and stood up on 4 legs, little short legs. And this was press mold. Like I was saying he rolled his clay out real thin and pressed it down in there. And he made a lot of those.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you still making miniatures?

Dorothy Auman:

No, I was making anything that I could at that time, larger pieces. I think during this time there was less miniature--I know I made less miniatures than at any other time.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is this when, had you all met yet? Had you met Walter yet?

Dorothy Auman:

No.

Walter Auman:

No.

Michelle A. Francis:

So during the war it was. . .

Walter Auman:

It wasn't till after the war, '47 I believe.

Michelle A. Francis:

'47. So during the war it was just you and your dad making things to sell, making ware, and doing the glazing and the firing of the kiln, too?

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-huh.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was your mother helping any? What was she, what was her responsibility?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, she would sand the pieces and get them ready, get 'em smooth. Oh, there are just innumerable jobs around the shop to do and she managed to keep them done.

Michelle A. Francis:

What about your sisters?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, both of them really had uh, were married and not living nearby, at the time. Later, well, I can't even think. Was it during the war? It was during the war, wasn't it, that Edith came back home, near home? It was during the war that she came back. And she began working at the shop again.

During the war things were slow, not because you couldn't sell them, but because you couldn't get them made fast enough. There's just no--Thurston would come home on furlow and spend his whole time, you know, turning, the times he'd get home. And, that would let us ride for maybe a month, you know. Then he would leave and we would have stuff.

Michelle A. Francis:

When did he come home? Did he stay for the duration of the war in the Army?

Dorothy Auman:

Yeah.

Michelle A. Francis:

After the war was over what happened?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, he came back and everything was, when I say "booming," you would have to experience this to know what I'm talking about. Everybody was on the up. You didn't find anybody that was depressed or thought business was going to be bad next year or anything. And the pottery, it was the same way, you know. So, he came back and really went to work and we began, uh. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Came back. Did he come back in '45? When did he come back?

Dorothy Auman:

Was it '44 or '45, Walter? When did you go in service?

Walter Auman:

Must have been--he came back in '45. I went in in '44 I believe it was.

Michelle A. Francis:

So when he came, he came back and started turning again?

Dorothy Auman:

Mm-hum. And by the '50s things were going pretty well, you know.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were you still using the same kind of forms, shapes?

Dorothy Auman:

Yes.

Michelle A. Francis:

And glazes? Had your glazes changed any?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, uh, during this period Daddy did a lot of testing, and yes, they had changed somewhat. That "colonial crme matt" came out during that time, that we, you know we were talking about it the other day, Walter. I think the trend toward earthy glazes was more prominent during this time than it is any other time. Pastel colors had faded away, you know, as far as the public buying.

Michelle A. Francis:

What about the brights that we were talking about, like the bright reds, turquoise, and greens?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, I think turquoise has remained a fair-sized part of the glazing all of the time. But some of the, like the pinks and the bright yellows and this type of thing, left. So, after Thurston came back, I had wanted to go to school, so I did. I went to Buncombe College and to Lenoir Rhyne.

Michelle A. Francis:

And to Lenoir Rhyne?

Dorothy Auman:

Mm-hum. And while I was at Lenoir Rhyne I worked at the Highland Porcelain plant out there. And I feel like it gave me another insight, they molded everything, they didn't turn anything. But I enjoyed that part of it. Mr. Moody was mighty nice to work under.

Michelle A. Francis:

How long did you work for them?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, it was about a year and a half.

Michelle A. Francis:

What were your responsibilities?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, various things. I was, wherever.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you learn the whole process then, of that plant?

Dorothy Auman:

Um, yes. [unintelligible] all over the place. So then, uh, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

What was your, what did you take in college, did you, what did you major in?

Dorothy Auman:

Um, art.

Michelle A. Francis:

Art.

Dorothy Auman:

Um, but we, I came back then and married Walter.

Michelle A. Francis:

In, that was when?

Walter Auman:

'49.

Dorothy Auman:

And then, then in '50, uh, 3 was it, we bought this place.

Michelle A. Francis:

What happened to your dad's shop?

Dorothy Auman:

Well, Walter went down and started working down there and,uh, . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

When was that Walter?

Dorothy Auman:

And I continued working down there all those years.

Walter Auman:

'53, that was in '53 wasn't it?

Dorothy Auman:

No, you was, you went to, was down there before that. '52 anyway.

Walter Auman:

Well, maybe it was. I can't remember any later than a week.

Dorothy Auman:

Anybody ought to keep a personal diary, hadn't they? They really had. But, your, um, we, our baby was born, our son was born, and when. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

He was born when?

Dorothy Auman:

In '50. And Walt fixed a place up at the house back where we were living at that time, for me to turn, you know, there. But then, part of the time I went down to the shop and turned and got somebody to take care of the baby left. So, then when we moved here, the idea was, it was plenty of room out here to fix a place and we started our shop. But all during this time, now, Walter was working down there all the time, I was working here turning for Daddy, selling, you know, turning for him, you see.

Michelle A. Francis:

Okay, so when you moved to this house, this property, you, you didn't open up shop, your own shop, you were just . . .

Dorothy Auman:

Yes, we did.

Michelle A. Francis:

You did.

Dorothy Auman:

I was working part of the time for myself. . .

Michelle A. Francis:

. . .and part of the time for your dad.

Dorothy Auman:

That's right.

Michelle A. Francis:

And then, Walter, you. . .

Walter Auman:

I worked, uh, I worked down there in the daytime and here at night.

Dorothy Auman:

And, we opened a salesroom here, that was almost, like, unheard of. You know, no one else but, I guess the Busbees had a salesroom at their shop. And Ben Owens had one at his shop. But, no other . . .

Walter Auman:

No, Ben didn't have one then. See, he never opened his shop up until, uh, after he left Jug Town, and had a salesroom.

Dorothy Auman:

Well, but most of the other shops were dependent on wholesales, you see. They didn't want the public to come in. So, the other shops, well, just like my daddy's. When he made pottery, they were put into like, huge barrels or bins, you know, they wasn't put on shelves.

Michelle A. Francis:

For display. Well, people were passing through and wanted to buy some pottery, would they just, go in, say what they wanted, and you would bring out a piece?

Dorothy Auman:

Honey, there was very, very, very few people. The people who did come were mainly local people, who knew that we's here, or Daddy was there, and they'd come out on a Saturday afternoon or something, to come out to buy . . .

Walter Auman:

Pick out a pie dish or something like that, or a vase to carry to cemetery. Something like that, and you would just get one or two pieces. You might have one or two sales a week, or maybe not one the next week.

Michelle A. Francis:

It was all wholesale, what you did.

Walter Auman:

Uh-huh. All wholesale.

(Tape stops then starts)Michelle A. Francis:

I'm a little bit confused on dates about this time. Walter, when did you first start working for Dorothy's. . .

Walter Auman:

We started, uh, I did, started working down at Dot's daddy's shop around either late '52, 1952, or '53, early '53. And that was the beginning of, uh, right in at the beginning of his time of making so many honey jugs for the wholesalers and the souvenir business, they would pack honey in 'em, like in the, the . . .

Dorothy Auman:

Shenandoah Candy Company.

Walter Auman:

Shenandoah Candy Company in Winchester, Virginia; the Great Smokey Mountain Industries in Knoxville, Tennessee; and places like that, were buying them. And they were packing honey in them, sealing them up with wax and selling them as souvenirs.

Michelle A. Francis:

Were these like regular jugs, or crocks?

Walter Auman:

Well, some of 'em were, and some of 'em were just a little pitcher-like thing. We had to fix it to where we could put a cork, where they could put a cork in it and seal it.

Dorothy Auman:

Not crocks.

Michelle A. Francis:

Not crocks.

Dorothy Auman:

Uh-uh, because they had to have a small mouth.

Walter Auman:

But they was all earthenware. Most of 'em were what we call variegated colors, multi-colored, bright, bright colors and, uh, pieces. And they were, we just made those things by the hundreds of thousands. He had three, three dealers that were buying them, and we were just, make a truckload at a time and we were sort of alternate, when we got the 10 thousand, that's what the truck would haul, and we'd just deliver 'em.

Michelle A. Francis:

You'd send it out. Were they signed? Was the pottery signed at this time?

Walter Auman:

No, it was, none of these were signed.

Michelle A. Francis:

Was that standard, not to sign the ware?

Walter Auman:

It was then.

Dorothy Auman:

Very few people signed their things during this time. North State signed theirs, A.R. Cole, and Jug Town.

Walter Auman:

That was just about the extent of the ones that signed.

Dorothy Auman:

Around here.

Walter Auman:

But they never did get into the production of making, uh, jugs and things like that, like Mr. Cole did. They were turning them out so fast until that was just another step, and it'd taken a lot of time and expense, too to, uh, would have amounted to an expense if you'd of signed the pots.

Michelle A. Francis:

If you would have signed each one. Is that the reason why pieces weren't signed?

Walter Auman:

Yes, mostly.

Michelle A. Francis:

Is the fact that you all were production potters not just you, but the potters, Seagrove potters, were production potters and it just took extra time to sign the pieces?

Walter Auman:

That was one way of cutting costs, just cutting that step out. And we made those on up, it was in the early '60s Mr. Cole got sick, and his health began to go quite rapidly, and, course we had just about saturated the country with the jugs (laughter) and they were, and they were looking for something else to go in, in the gift shops. And Mr. Hicks came in the late '60s to Southern Pines/Pinehurst area, and started uh, the Carolina Soap and Candle Company.

Michelle A. Francis:

What, what is Mr. Hicks' first name?

Walter Auman:

Jack. And, uh, he started in, in his garage, making candles and he came up and wanted candle holders for, to sell, to have a line of candle holders to sell. And we got started making those, uh, a dozen at a time, or 2 dozen at a time, then it, it just kept growing. And he grew, his business grew real fast. And we, at one time, Mr. Cole had 11 employees a'working, and most of them were, uh, about 4 of 'em were, 5, 4 or 5 were turners. And the rest of us was just glazing 'em and finishing 'em up, and getting 'em ready for the market.

Michelle A. Francis:

Who was turning for him them?

Walter Auman:

Uh, Virginia Shelton was turning at that time, my wife, Dot and Thurston was turning, uh, Vernon Owens, and his father Melvin was working part time--anybody we could get to turn at that time, when we was needing 'em. And we were producing, oh, 10 to 20,000 pieces a week. There were all small items, and we were firing a kiln every day, firing 5, 6 kilns every week. And, course whenever they, uh, as it went on, Mr. Cole's health got real bad in the late '60s. I mean in the early '60s his health went down quite well, and then just a year or two after he got sick, why he was just disabled to keep the shop going. That's when I started looking after the shop. And we operated the shop there on a small, he passed away in '67. Course Thurston died in '66. That was a big blow to us, to lose him as a turner. And then

Mr. Cole passing away in '67. And, course really then, Dot was our mainstay and we was, she was trying to turn enough to keep both shops a'going and I was getting anybody I could to help us produce, so we'd have things to go. And then Mr. Hicks sold out the candle shop to Lenox China, and they moved the candle shop to Wisconsin, and that was a good way to get out of it then. So we quit making candle holders and we closed the shop, his shop in, uh, in the early '70s, I don't remember exactly what . . .

Michelle A. Francis:

Mr. Cole's shop you closed?

Walter Auman:

. . .uh-huh. We closed his shop in the early '70s. By that time we had our shop going up here and there was just no way we could keep both shops going with no more potters than we had. So we just closed it up all together and Mrs. Cole was a'getting on up in years, too and her health was getting bad. So she, uh, was by herself and someone had to go and stay with her, and then she decided she'd come and move in with us. So she came up and, and, she would get up and go to the shop, just like she did at home. She enjoyed it quite well, getting back into the mainstream of it.

Michelle A. Francis:

It was probably good for her, to have . . .

Walter Auman:

It was good for her.

Michelle A. Francis:

It made her feel like she was helping.

Walter Auman:

And, feel active, at least she felt like she was needed and was of some benefit. And, uh, so we as I say, we closed the shop in the early '70s, '72 or '73, I don't remember exactly. We sort of phased it out and sometimes we'd uh, wouldn't fire but one kiln a week or one every other week, but we just sort of used what pots we had down there and 'em up and glazed 'em and sold 'em and uh, and got rid of everything that way. And then we just uh, just sort of moved part of the, most of the, a lot of the equipment up here. We sold a lot of it to the other potters and gave it away and anything. For there was nothing really of a, of a extremely value, it was only to a potter. A potter could use it, but no one else, it was just junk to them. And of course, he had, a couple of trucks and I sold one of the trucks before he passed away. Ane we kept a small truck and the car. And then after, after he died, why Mrs. Cole just gave Dot and

her oldest sister was the only ones living, so she gave Dot the truck and gave the car to the other sister. And that way she got rid of the vehicles. And then the, the rest of the things there at the shop, why she just, Edith taken part of it and sold it and so, I moved the rest of it up here that I could use. And very little of it we needed, for we had most of it already, uh, the things to operate.

Michelle A. Francis:

Did you have anybody helping you with the glazing and the firing?

Walter Auman:

Mr. Cole.

Michelle A. Francis:

Mr. Cole was helping you. Before he got sick.

Walter Auman:

What little I know about it, most of what I know about it is what I got from him and uh, back in the '50s. And after I got to, stayed around there a while, he just turned all the glaze mixing over to me, and of course if I needed to know anything, why I'd go and ask him for, and uh, particular in the early '60s, uh, late '50s, and he was glad to get rid of one of his chores, and he was getting a little older, too, and wasn't able to look after it like he had been doing. And so I got to firing the kilns, mixing the glaze, and looking after it all, really before he got disabled. When I got ready to open my shop up here full time then, why I had acquired most of my knowledge (laughter) from his.

Michelle A. Francis:

What prompted you all to open your own sales shop here when it wasn't done?

Walter Auman:

Well, I had been, uh, I had been delivering a lot of the pottery since I had been there at the shop. I's sort of taking over the sales part of it, whenever I went there.

Michelle A. Francis:

At, at Mr. Cole's?

Walter Auman:

At Mr. Cole's. And I looked after most of the selling and the, doing that part, that end of the book work. And, uh, waiting on the customers and things like that, as they'd come in. And then we would deliver to the gift shops and things. And, we realized that that's where, if we's gonna make a living at it, that's the way we was gonna have to do it. We's gonna have to do the selling, for they wasn't willing to uh, give us any more for our pots. We were selling uh, we were selling pottery for $2.50 and $2.75 a dozen, and uh, which, that amounted to uh, 20 and 22 cents a piece. When we would go to these retailers and tell 'em that

we were going up 25 centson the dozen, uh, they said, "Well we just can't pay that." And we would go into their shops and there they would have the pieces, each piece marked $1.98.

Michelle A. Francis:

So you knew that they could pay.

Walter Auman:

So we knew they were making a profit on it, or they couldn't uh, they couldn't keep a shop open in Gatlinburg, Tennessee for three and four months out of the year and go and spend the other seven months in Florida. So we knew they had to be a'making pretty good money. And course, you could see the prices that they were. So we decided we was gonna open up a retailer's shop. And, when we opened up, the things that we were wholesaling for 25 cents we got to retail them for 50 cents. And it, it'd taken us a long time. We wasn't making very much at it, but after staying in business and we got involved with one of the candidates that was running for office and uh, he would advise us how to do to bring more customers in. And that's how we did. In fact he was head of uh, travel and promotion in Raleigh. That was Skipper Boles. And he became a very good friend of ours, and he was helping us out and he told us what we needed to do was get the people to come into our area. So that's when we got to print the brochure and getting tourist to come in. And all potters have benefited by it. For they was, and we have done, we have done right well since, since then. Since we have got to, in fact all the potters have. I'm sure that uh, they would all say that it has been a big help to 'em. Of getting our brochures in the welcome centers and we had to do that by getting all the potters involved in it, and chamber of commerces and things like that, to distribute the brochures for us.

Michelle A. Francis:

It doesn't sound like there's really been a slack period.

Walter Auman:

There hadn't really been a slack period in uh, in the last 15 years. Since we got the tourists to come into our area, and not altogether tourists. It was, we let the people in Raleigh, Chapel Hill, Greensboro, Charlotte, and even Washington, Roanoke, and places like that. They were just, uh, maybe a group of women get in the car and just make a trip to visit all the potters.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah, I have friends that just come once a year and they go to all the potteries and buy things for themselves and gifts for people. He was telling me about going retail. From wholesale. to retail.

Dorothy Auman:

Then you caught up on the, on the [unintelligible] movement.

Michelle A. Francis:

Yeah.

Dorothy Auman:

So that gets it.

Michelle A. Francis:

I think so.

(End of Tape)