"WAKE THE SLEEPING GIANT"

by

Lieutenant General Frank A. Armstrong, Jr., USAF (Ret.)

as told to William E. Hickinbotham

OLD COPY

"Some people say it is wrong to say we could be stronger. It's dangerous to say we could be more secure. But in times such as this, I say it is wrong and dangerous for any American to keep silent about our future if he is not satisfied with what is being done to preserve that future."

JOHN F. KENNEDY, Sept. 20, 1960

P R O L O G U E

THE BEGINNING OF THIS STORY is a matter of personal experience. The end is a matter of national concern. Both are important, because national problems are frequently resolved --- or left un-resolvepd -- by men whose judgment is based upon personal experience and, often without realizing it, upon experiences of others.

Upon entering military service, every American officer pledges to obey. the orders of his superiors. Also, he swears to defend his nation against all enemies. Seldom is it necessary to decide which of these pledges must be honored first.

Confronted with such a decision, I placed allegiance to my nation above obedience to my superiors. This does not necessarily mean I was right, or they wrong.

Based upon knowledge and experience gained during 32 years as a military flyer and commander, in 1959 my convictions conflicted with those of my superiors. I made every effort to convince them of the validity of my views; while many agreed, none took action to support them.

Firmly believing the national security was at stake, and with full knowledge of possible consequences, I decided to express my views to the American people.

Although this decision ultimately resulted in >my< being withdrawn from military service, I do not regret having made it. In or out of uniform, I must live with my conscience, and I view the incident without ill-will or rancor

toward those who did what they thought right.

In the Book of Proverbs it is written: "Give instruc¬tion to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser. Teach a just man, and he will increase in learning."

In relating the adventures and mis-adventures of my career, it is my earnest desire to give the generals of a day yet to come some insight into what may lie ahead for them. The conflicts noted on these pages are included in the interest of truth. The purpose of this book is to clarify, not crucify.

So it is the story begins.

P-2

CHAPTER ONE

No one is born a soldier. Those who decide to carve a career from the hard rock of military service arrive at their decisions in varied, often strange ways.

One summer morning in Texas I stood at attention in the barracks, waiting for the inspecting officer to reach my bunk, wondering why I abandoned the carefree, lucrative life of a professional baseball player to become a flying cadet. The answer was simply "Fluffy."

We first met at a house party in North Carolina. The host introduced her as Vernelle Hudson. Noting her petite beauty, I immediately named her "Fluffy." Three weeks later I returned to Sarasota, Florida, leaving behind three things --my heart, my fraternity pin and my freedom.

The inspector came to a heel-clicking halt in front of me, did a smart right-face and began looking at the display in my foot locker. I didn't move a muscle, or bat an eye. I had worked half the night to arrange my gear in perfect order. This was one inspection I intended to pass so I might be permitted to visit San Antonio that afternoon.

I had not enjoyed many liberties since arriving at Brooks Field; it was not difficult to get into trouble in

1-1

the flying training program. A thumb print on a water glass or dust on a coat hanger could mean a penalty of several demerits. To erase these "black marks", cadets had to march around a concrete area known as the "bull pen". One demerit meant thirty minutes of marching. It was the same "plebe" system employed at West Point. "Tours" in the bull pen had to be walked during the few leisure hours allowed cadets.

Apparently satisfied that my clothing and toilet articles were arranged in proper order, the inspector turned his attention to my personal appearance. Slowly he brought his eyes up, searching for lint on my uniform or an insignia which might be out of place. Finding none, he focused his gaze on my hair. A slight sadistic smile crossed his lips as he said, with obvious pleasure, "Mr. Dumb John," (as all cadet underclassmen were called) "you need a haircut. "

"Sir," I replied without thinking, "I just got a haircut yesterday."

The smile broadened into a wide grin. "That will cost you a tour in the bull pen, Mr. Dumb John. I didn't ask what you got yesterday. I said you needed a haircut, and you do. Have a nice afternoon Mr. Dumb John."

How stupid to offer an excuse where excuses were never accepted! From that point, however, I knew exactly how to handle the situation, and precisely what to say. "Yes, sir." No more was needed -- no more would help.

1-2

That afternoon as my friends boarded the bus for San Antonio I waltzed my rifle around the bull pen in the heat of the Texas sun, anxious to "walk off" the demerits so I could get another haircut.

For a boy from a small North Carolina village -- population 600 -- I had come a long way. After high school and prep school I attended Wake Forest College on a scholarship, and earned my keep during the summer playing semi-professional baseball. Graduating in 1925, I became a full-time profes¬sional with a farm club at Sarasota. Earning $300.00 per month, I was living "high on the hog" and enjoying life immensely. Then Fluffy happened along and blew my plans to high heaven. She was "not about to marry a man who wanted to do nothing more with a college education than play ball." So, I enlisted in the Air Corps as a flying cadet, and soon was up to my neck in trouble at a God-forsaken airbase in Texas. I questioned my sanity many times during those eventful days, and before assuming the status of an upperclassman I walked a total of 75 hours in the bull pen.

Flight training in 1928-29 was much different from today. The aircraft were mostly bi-planes with open cock-pits and few instruments. They were slow but relatively un¬complicated. A cadet soloed after no more than eight hours of airborne dual-flight instruction. If he was not quali¬fied to fly alone after logging eight dual hours, he was "washed out" and honorably discharged from the service.

1-3

I had never been in an airplane before flight school, but I found flying exciting, exacting and challenging. I easily met every challenge but one -- I couldn't learn to land. In fact, after 5 hours of dual-flight, I began to think I couldn't hit the ground with my hat.

Still, I wanted to graduate more than I had ever wanted anything in my life. I had to know if I was making suitable progress, so I went to Captain Claude Duncan, chief check pilot for the primary phase, and asked him to give me an evaluation ride. My instructor, Lt. Howard Engler (who had large feet and was known as "Suitcase" Engler), was unaware of my visit, but I knew if the check pilot wasn't satisfied with my flying, he could wash me out. We took off, flew two rounds of the pattern making touch-and-go landings, and on the third round Duncan ordered me to make a full stop. Completing the landing, I taxied the aircraft to the parking area and started to climb out. Duncan had already stepped onto the wing. "Sit down," he said, fastening the safety belt across the seat cushions in the front cockpit, "take it around by yourself."

I will never forget how completely alone I felt as the wheels lifted off the ground on that initial solo flight. There was no one "up front" to correct my errors now; I had to make a good landing.

On the first attempt I landed long and Duncan waved me off with a signal to go around. In the second pattern I cut the power sooner, made a fairly smooth landing and

1-4

came to a stop near where he was standing. He didn't have to walk far to reach the aircraft, so I guess he decided to let well enough alone. He apparently was happy with my flight, and I was exhuberant! I had soloed after six hours of dual instruction!

He climbed aboard and I taxied the aircraft to the parking area feeling a little like Eddie Rickenbacker. My ego was deflated, however, when Duncan informed me I would complete the full eight hours with my instructor. I had no more trouble in flight school, though, and in March of '29 received the shiny new wings of an Air Corps pilot and the shiny gold bars of a second lieutenant. The course had been difficult, but those who survived the rigorous training were the proudest men in the world that day.

I had taken my advanced training in the ATTACK section at Kelly Field, Texas, so I was disappointed to learn my first assignment would be with the Second Bomb Group at Langley Field, Virginia. Young, full of pep and bravado, I had grown to love the daredevil tactics employed by attack aircraft. Our job was to come in low over a target --sometime at tree-top level -- spray it with machine gun fire, drop small fragmentation bombs, and lay smoke screens. We were reminded constantly that we could be "early, but never late" with our attacks, or the bombers would suffer. It was exciting precision flying and the prospect of being restricted to straight and level air operations was quite unbecoming.

1-5

Four of us boarded a train in our brand new officers' uniforms replete with Sam Browne belts, skin-tight breeches and brilliantly shined cavalry boots with spurs. The boots were a problem; once we managed to get them on, it was almost impossible to get them off. Dave Graves couldn't get his off during the entire trip. Every gunman porter from Texas to Virginia tried to help him, and got a kick in the britches for their efforts. Dave was stuck.

Soon after our arrival in the east Miss Fluffy and I were married at a Washington, D. C. Presbyterian Church. Our honeymoon lasted exactly one day and two nights. Mar¬ried on Saturday afternoon, I reported for duty Monday morning.

We found a small apartment at Hampton, Virginia, and lived there during the first three months, then we were assigned quarters on the base. Within the year, I was transferred back to Kelly Field to attend flight instructor's school. We packed our belongings and set out in an ancient car. It was a rugged trip, especially for Fluffy who at that time was expecting our first child. The doctors ad¬vised her against making the trip, but she was a spirited woman and was determined to stay with her husband. I was worried about her, but I was glad she decided to go.

After completing the course I was ordered to duty as a flight instructor at March Field, California. Fluffy was then just two months away from the big day, and the doctor was adamant in demanding she return east by rail. She left for Richmond as I drove on to California, alone.

1-6

Frank Alton Armstrong III made his first appearance at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington in the spring of 1930. Fluffy asked her father to wire me the good news. In his excitement, he neglected to mention whether the baby was a boy or a girl, so I had to wait out another few hours -- and an exchange of telegrams -- before learning the secret word.

When the baby was three months old, Fluffy boarded a ship on the East Coast bound for San Francisco, via the Panama Canal. From San Francisco, she flew to Los Angeles. I met her at the airport and drove her to Riverside, where I had a furnished bungalow waiting. This was 1930 and the depression was in full swing, yet we were deleriously happy. A lieutenant's pay didn't go very far, but she managed to stretch every dollar until I thought Washington would scream. Our rations were meagre, our spirits were high, and we were reluctant to leave when I was transferred back to Texass--Randolph Field -- in Member of 1931.

While serving as a flight instructor I not only taught but learned a lot. Aviation was still primitive in the early '30s, and experimentation was the rule rather than the exception. Regulations pertaining to aircraft operation were not as numerous nor restrictive as they are now, and many things happened which, in retrospect, make me wonder how we ever survived.

For example, one of my students wanted to make a parachute jump. On a sunny afternoon we went to the practice area to do acrobatics. I was demonstrating a slow roll and, just as we had reached an inverted position, I felt

1-7

the aircraft rise suddenly. I rolled on over, glanced around to see if he had been overriding the controls, and got the surprise of my life -- the back seat was empty ! Banking the aircraft, I looked below to see the top of a parachute canopy fading toward the ground. I circled the area until he landed and signaled he was unhurt, then re-turned to the field. After landing, we discovered the seat belt, although still latched together at the buckle, had come unfastened from one side of the seat. He never changed his story -- claiming that the belt had "just come undone" --- but I'll always wonder.

Another difference in training during those days was a method I developed for relaxing tense students. Tense¬ness is coon among students, but until they learn to relax, flying is not easily mastered. Whenever I noticed one of my boys tightening on the controls, I would take him for a low-level ride, including a few passes beneath high tension wires. The results were amazing. Subjected to a few minutes of this kind of flying, students automatically relaxed when taken back upstairs.

A specific incident during my stint as a flight in¬structor has always made me wonder how many potentially great pilots never received their wings. Once, when I was a senior check pilot, a student who was having difficulty was sent toe with a note. The note suggested he was not good pilot material, and urged me to give his a cursory 20-minute chock ride, an unsatisfactory rating, and to wash him out. Once in the airplane, however, I found that

1-8

his abilities were not as bad as his billing, so I worked with him for a while and got him squared away, He even managed to graduate. Later, that young West Pointer, Lt. Joe W. Kelly, would become a Lieutenant General and the Commander of the Military Air Transport Service -- the world's biggest airline: From this and similar incidents, I learned that failure or misunderstanding is not always the fault of the one who fails or misunderstands.

In May, 1932, Lt, A. F. Hegenberger made the first blind flight without a check pilot aboard, and a few months later was awarded the Collier Trophy for this feat. The prospect of flying entirely by instruments was intriguing to several of us, so we began to practice during offer-duty hours. One pilot would occupy the front seat, his vision unobstructed, while the other sat in the rear cockpit, which we covered with a cloth hood. The pilot in front would take off, climb to a safe altitude, then give control of the aircraft to his partner. The only instruments installed in the trainer were an altimeter, for maintaining level flight; a needle-and-ball turn indicator to judge the degree of bank during turns; and a magnetic compass, for finding a heading. It wasn't much to work with, but it whetted my appetite for flying "on the gauges," and in 1933, when the Air Corps opened a blind flying school at Rockwell Field near San Diego, I attended.

Soon after reporting to the school I heard rumors that the Air Corps might be called upon to fly domestic airmail. The rumor became fact on February 19, 1934, when

1-9

a Presidential Order instituted the service. I was delighted to receive orders assigning me to Route #4, under the command of Capt. Ira Eaker. His head-quarters was at March Field, but our operations were based at Burbank. Just five years before, Capt. Eaker had earned a considerable reputation as a skilled aviator when he participated in a record-setting endurance flight. He and Major Carl "Tooey" Spaatz circled the Los Angeles area for 150 hours and 40 minutes (almost 6 days) in a Fokker C2-3. When an engine conked out and forced them to land, they had flown 11,000 miles!

I was one of three pilot officers who reported at the same time. Capt. Eaker briefed us on the mission ahead. There would be problems, not the least of which was the weather. This was the most severe winter in years, and flying in an open cockpit was like sitting on the front porch of an igloo -- cold and breezy! Several pilots suffered frost-bitten noses, ears, and cheeks. We were also advised there might be monetary problems; per diem allow¬ances were expected, but had not been authorized yet. We would live at Burbank where no government quarters were available, and we realized immediately it would be a chore trying to adjust service pay to meet the demands of a civilian existence. The officers would find it rough go¬ing, but for the enlisted men it would be almost impossible; some of them were earning only $17.00 per month

Same as original, Disregard marks< [written in the margin] Airmail Route #4 extended from Burbank to Las Vegas, Nevada, through Bryce Canyon >on<, to Milford, Utah, and on to >Las Vegs Nev. through Bryce Canyon to Milford Utah and on to Salt Lake City Utah

1-10

Salt Lake City. Another shorter run extended from Burbank to San Diego. LB-5-A light bombers were scheduled for the longer routes, while P-12 single-seater pursuit air-craft were to fly the shorter runs.

After completing the briefing, Capt. Eaker led us out-side the operations building and pointed to three P-12's parked on the ramp nearby. "I want you to take those air-craft," he instructed, "fly the route to get familiar with it, and by the time you get back, we'll be in the mail business."

I had never flown a P-12, but in those days a formal check ride in a single-seater was a luxury not often >ever< afforded. A crew chief instructed a pilot on how to start and stop the engine, and from that moment on the pilot had the bird strapped to his back, and was on his own.

The P-12 was fast and maneuverable, and we enjoyed an uneventful trip around the circuit. The next evening we returned to California, found rooms at a Burbank hotel, and got a good night's sleep before embarking on one of the greatest adventures of a lifetime.

The mail was gathered by the Post Office Department during the day, sorted, and delivered to the airport in the evening. Consequently, airmail flights usually began at night. To speed operations, Captain Eaker limited the ground time allowed pilots at various refueling stops. When a change in crew was necessary, the methods used were like the old Pony Express system. A pilot would land, taxi as quickly as possible to the operations area, jump from

1—11

the airplane as mechanics started refueling it, and usually pass the relief crew on his way into operations. Seven minutes after shutting off the engine, the refueling was completed and the next pilot was on his way.

Undoubtedly the roughest part of Airmail Route #4 was the leg through Bryce Canyon, a rocky, wild area, filled with grotesque, stone pinnacles. Unable to get up over bad weather, our only alternative was to fly through it at low altitude. This made the Bryce Canyon leg extremely perilous.

On March 10, after only three weeks of operations, nine pilots and passengers had been killed flying airmail throughout the United States. Air Corps participation was discontinued temporarily. On March 19, we resumed operations, and Capt. Eaker decided a change in methods --assigning specific pilots to regular routes -- might result in greater safety. He reasoned that by flying the same leg every night, a pilot would get to know his route better, and have a better chance for survival. I volunteered for the Milford - Las Vegas run via Bryce Canyon, and he made me Chief Pilot in that area.

Before I completed the last airmail flight in that sector on June 1, there were several times I regretted having volunteered, but the good Lord seemed to be watching over me. There were numerous close calls, but I came through without an accident.

The real heroes of the airmail service were not the pilots, but the enlisted crew chiefs who substituted for

1-12

co-pilots on most of our flights. A braver group of men I have yet to see. An example of the hazards they faced is the procedure necessary to transfer fuel from the LB-5-A, Curtiss Condor fuselage tank into its wing tanks. To accomplish this, they climbed from the cockpit, straddled the fuselage, slid aft along the turtleback until they found a zipper which exposed an opening in the fabric. Then, they opened the zipper, slid down into the fuselage, transferred the fuel with a hand pump, then remained there in that cramped space until the flight was completed because they couldn't climb forward again. It was an odd feeling to take off with someone beside you, and then land apparently alone. We eventually rigged a system of bells to warn them in case bail-out became necessary. They rarely complained, despite the dangers and the financial problems they endured, except in good humor.

The airmail days were not without some laughs. As mail couriers we carried pistols to protect our cargo. Once a pilot called Las Vegas to report he had a flat tire and was afraid he might ground loop upon touching down. An official in the tower radioed a suggestion that he use his pistol to shoot out the other tire. "Sorry," came the reply, "I can't do that. My pistol is locked in the mail compartment."

Another pilot, on one of the eastern routes, took off one night and flew some twenty miles from the field before calling back, "Somebody call the operations officer and find out where this mail is supposed to go." He had locked his manifest in the baggage compartment.

1-13

Capt. Eaker was an inspiring leader and an active pilot. He often visited his men at the various outlying stations. We found he wan't much of a talker, but none of us could deny he was a man of action. My respect for him grew continually during those difficult months; I later learned that the respect was mutual.

After flying the last delivery of mail from Las Vegas to Salt Lake City, I was sent again to Randolph Field, Texas. Within a few weeks, accompanied by Fluffy and Frank III, nicknamed "Fuz," I was off to Panama for duty with a pursuit and observation squadron at Albrook Field, Canal Zone. We enjoyed the sea voyage, and soon became accustomed to the tropical climate.

The weather was hot and humid, so there was a natural tendency to become lax, even slovenly. To prevent boredom from affecting our morale we were required to don formal white uniforms each evening before dinner, and were forbidden to go to any public place in less formal attire. The rule was effective, and morale was always high.

A particularly unusual aspect of the assignment in Panama was our training routine. We were flyers, but we participated in many ground exercises. Three afternoons each week we practiced close order drill, and often competed with ground units in marching competition. Occasionally we went on field exercises in the jungle and lived in pup tents as the infantry did.

1-14

There were exciting days to punctuate the humdrum of peacetime flying duty. Most of our missions were flown on patrol but occasionally we towed targets for the artillerymen. The targets were cloth sleeves dragged behind the aircraft at the end of long cables. I never learned to enjoy these missions. During daylight hours they were had enough, but at night they were downright uncomfortable. We flew with our position lights on, and attached small lights to the target. I recall one tow-target night flight which could have been my last. As I brought the aircraft across the range area, shells began exploding directly in front of our flight path. Both the airplane and the target were properly lighted, but apparently an artillery officer had miscalculated and was giving his gunners inaccurate firing orders. At any rate, I realized we were about to fly into a wall of steel, so I yelled to my crew chief, "Cut that damned target loose! Now!" He clipped the cable as I flipped off my position lights, banked sharply, and got the hell out of there as fast as I could.

The majority of the aircraft in our inventory were

1-15

P-12 pursuit ships and LB-5-A light bombers. We had one Douglas OA-4 Amphibian which only a few of our pilots knew how to fly. When the operations officer learned that I had checked out in the OA-4 during my stay at Rockwell Field, I was assigned the job of flying the old monster, which had been named "Goo Goo, the Duck."

Because of "Goo Goo," I was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The mission began with a flight to Quito Island, a Panamanian penal colony, located 100 miles or so from our field. I was to fly a civilian communications expert to the island, help him find a site for a radio installation, and bring him back. Lt. Jimmy Wallace, a young friend of mine, was assigned as co-pilot although he had never been checked out in the OA-4. Our crew chief was a very efficient sergeant named Tanner. The fifth person aboard was our base communications officer, a major, who was serving as assistant to the civilian on this project. The trip to the island was uneventful, but upon lowering the landing gear the crew chief experienced some difficulty. It was minor, but it worried me, so as we passed over the Mala Peninsula returning to Albrook, I decided to test the system. I told Sgt. Tanner to lower the wheels, he gave me a quizzical look, shrugged his shoulders and complied. I'm sure he thought I was mad; we were fifty miles from the base and flying over dense jungle. Even if forced to land in that area, we would have gone in with our wheels retracted to lessen the chances of flipping over upon impact.

As Tanner leaned forward to tell me the gear was down

1-16

and locked, the aircraft suddenly began to vibrate. In a few seconds the vibration was followed by an explosion. A huge crack appeared in the windshield, and the craft veered sharply to the right. The propeller on the right engine had flown off! Cutting the power on that engine, I managed to apply enough pressure on the rudder pedal to straighten us out, but realized immediately we could not stay aloft more than a few minutes. It was impossible to make it back to our home base.

The major, who had been talking on the radio when we lost the prop, did not hesitate an instant. He dropped the microphone (which was still turned on), pulled open the compartment door and bailed out without even saying goodbye.

I glanced over my shoulder and saw our civilian passenger had not moved. Apparently he was too stunned by the violence of the past few seconds, so I shouted, "Get the hell out of here!" He moved to the door and then remembered he was still wearing his glasses; he stopped to put them in a small black case he carried in his shirt pocket. I yelled again, "Dammit to hell, get out of this thing!"

Sgt. Tanner was ready to go, but the civilian standing with his feet spread wide to brace himself, blocked the door. Tanner wasted no more time. He dived out between the civilian's legs. The man finally managed to put his spectacles away, and he, too, dropped from view.

My co-pilot had unfastened his seat belt and was preparing

1-17

to leave when he realized what I already knew -- I would have to stay with the airplane. When the propeller went, it took much of the engine with it, and I could not trim "Goo Goo" so she would glide properly. If I took my hands off the controls for a moment, the old bird would likely go into a spin, or at least a spiral, making it almost impossible for me to reach the door. I had spotted a clearing in the jungle and had decided to set her down there. When Jimmy saw I wasn't going to jump he sat down again and strapped himself in. I told him to leave, but he refused to go.

I made the approach on the clearing and, precisely at the right moment, Jimmy cut the switches. We came in low over the trees, dropped down into the clearing and, after knocking the tops off a few tall bushes, made a reasonably soft landing. After braking to a halt, we just sat there in silence for at least a minute. Everything was so quiet and still, it was as if we had died. We had come awfully close.

The microphone had been on during the entire emergency and our remarks were monitored in the control tower at Albrook, and by Major Monk Hunter who was leading his pursuit squadron on a formation flight in our vicinity. Monk was a colorful character, a World War I ace. He was eager to come to our rescue. After locating the clearing, his squadron circled overhead as Monk brought his P-12 in for a landing. I must say, I have seen better ones. It had rained in the area just prior to our emergency, and the

1-18

ground was still wet. Monk's approach was hot, so when he applied the brakes, the wheels skidded along the slippery grass until they caught in a ditch; the P-12 slipped over on its back. It barely stopped moving before there was a flurry of action near the cockpit section. Monk wriggled from under his bent bird like a scared rabbit. What had started out a normal day had become one of the most exciting in the lives of six people.

One of Monk's boys radioed back to the base for assistance, and within a couple of hours an LB-5 -A touched down beside us. We climbed aboard and returned to civilization.

Of the three men who bailed out, two were rescued before sunset and the third was discovered by natives as he wandered about in the jungle. In survival training we had been instructed to remain wherever we landed, making it easier for rescue crews to find us. The major disregarded this information and tried to walk out.

His efforts eventually led to his death, in an indirect way. While in the jungle he contracted a type of tropical fungus which later caused him much pain, discomfort and swelling in his legs and ankles. He became obsessed with the false idea this was some sort of incurable disease and, while making a sea voyage back to the States some months later, he jumped overboard. The fungus which had plagued him in tropical Panama would have disappeared a few weeks after returning to a temperate climate.

Our tour of duty in the tropics ended in March, 1938.

1-19

We returned to the States and enjoyed a few weeks' leave before reporting to Barksdale Field, Louisiana. Fluffy and Fuz went directly to Richmond to see her parents; I stopped off at Hobgood, North Carolina, for a surprise visit with my Mother. My father had died while we were in Panama.

My train arrived in Hobgood just before dusk, and I experienced a warm wave of nostalgia as I stepped from the Pullman car onto the depot platform. So such of my carefree childhood had centered around that depot. As a boy, my favorite pastime had been climbing on and off moving freight trains which passed through our community regularly. The game we played was to see which boy could jump aboard and off again at the fastest speed without being thrown. It was extremely dangerous, and I shudder when I think of some close calls we had.

The weather was cool, but not uncomfortable, so I decided to walk home. I was anxious to see how much had changed since I'd gone out into the world.

As I walked along the platform toward the street, I watched the train pull out, gradually pick up speed and disappear around a curve on the outskirts of town. I liked trains. The railroad had played an important role in my early life, and once, almost ended it. My first serious job was as a driver in a log woods. My father was a superintendent of an extensive logging project, and hired me the summer I was sixteen. I was the only white driver, and the only boy in the camp. My salary was $2 for a day that began at 4:00 a.m. and ended at 7:00 p.m.

1-20

One Saturday he sent me with three colored men to accompany the payroll from the main railroad line to the camp. We were riding on a small hand car and I sat on a wooden box containing the money sack and a suit of clothes ordered by one of the drivers. As we turned a bend on the narrow gauge tracks, we met a log train coming at us head on.

One of the men yelled "Jump, Junior!" and I took off like a flying squirrel as the engine smashed into the hand car, passing over the box containing the money bag and the suit. The payroll was intact, but the suit was delivered to its disgruntled owner with the trouser legs about eight inches shorter than they should have been.

The railroad also gave me my first glimpse of a dead man. I was to see many more dead men during my lifetime, but I never forgot the first. He was a train robber who had been shot by a railroad detective, and had fallen beneath the wheels of a moving freight car. His body was chopped in two, and I watched as several men picked up the halves and placed them on a tarpaulin on the depot platform. It made me sick.

I walked from the depot along the main street of town. It seemed even smaller now, and I wondered if it had actually shrunk, or if travel had changed my sense of proportion. I decided it was the latter. I passed the Baptist Church and remembered the many Sunday School classes of years gone by. Mother was an active participant in many religious affairs. We attended the Baptist Sunday School in the morning

1-21

and the Methodist Sunday School in the afternoon. I don't think I learned very much in either one, but since most of my friends also attended, to remain away would have been worse than going. In later years, I would regret not having been more attentive to the lessons.

At last I reached our house, knocked at the door and, within moments, found myself in the midst of a warm but tearful homecoming. We had several happy days together before I left to meet Fluffy and Fuz, and report to my new base.

Eventually I assumed command of the 13th Bomb Squadron at Barksdale. I had never commanded a unit before, and the new status offered many challenges. It also taught me many things. I soon found it was one thing to be responsible for your own actions, and quite another for those of more than 100 people. The experience was rewarding, and I began to develop a sense of leadership.

On April 3, 1939, President Roosevelt signed the Expansion Bill authorizing an appropriation of $300,000,000 and the construction of 6,000 airplanes for the Air Corps. In August, I read with envy of a flight made by Majors Stanley Umstead and C. M. Cummings. Its purpose was to demonstrate the speed with which reinforcements could be rushed to Panama to protect the Canal. They had flown a B-17 -A from Miami, Florida, to the Canal Zone -- a distance of 1200 miles -- in six hours!

In October of that year, Hitler began a march against the world by invading Poland. In so doing, he set the

1-22

wheels of world justice in motion against himself. We watched the war headlines with wary eyes, and our training began to take on a new meaning. We weren't in the fire yet, but we knew we could be before too long.

In May, 1940, the President called for the production of 50,000 planes a year. Later that month, we were busy at Barksdale, participating in the first complete military maneuvers simulating European combat operations. More than 300 aircraft took part, and we all got a small idea of the type of flying we might be doing within a few short months.

In July, the Air Corps opened a training center at Maxwell Field, near Montgomery. One part of the center was the Air Corps Tactical School. I had grown more and more interested in the potential combat capabilities of the airplane, and more conscious of the ever-darkening international situation, so I submitted an application to attend the school, and it was accepted.

Near the end of the course, I went on a cross-country to Langley Field, Virginia. There I was notified I had been selected to go to England as a Combat Observer, and was scheduled to depart New York aboard the Yankee Clipper in just a few days.

I called Fluffy and asked her to get my winter uniforms out of mothballs, and have them cleaned and pressed by the next day. For security reasons, I couldn't tell her on the phone where I was going, or why I needed the winter clothing, but she later told me she felt I was heading for trouble. She was right -- as usual.

1-23

The next night I returned from Langley and packed my bags. Just before I climbed aboard the train, a hand truck bearing a coffin trundled past us. It was a spooky feeling, and we wondered whether it was a good omen or a bad one.

The Yankee Clipper flight of October 24, 1940 had eleven pilots aboard. Two were crew members, nine were American military observers. None of us had met prior to boarding the Clipper, but we had a similar mission. We were to proceed to England, inspect and learn everything possible about the operational war machinery of the RAF and the tactics employed by both the British and the Luftwaffe, and report our findings to Washington. We were assigned to the American Embassy in London.

Flying the Atlantic in those days was still an impressive feat. Perhaps that explains why I remember even small details of that flight after all these years. There was a brief ceremony as the crew boarded the huge flying boat, then the passengers embarked in single file. When the tearful goodbyes were finished at last, the hatch was closed, the engines came to life and the proud seabird taxied into take-off position. After a smooth run across the water, and the lift-off, the skyline of New York disappeared behind the Clipper; soon all traces of land were out of sight. First stop was Bermuda. The landing there was very smooth, but none of the passengers watched the touchdown. The window shades had been closed because we were nearing a combat zone. We were getting closer to war,

1-24

but we still had no idea how near the war was getting to us.

A British Airways launch took us from the Clipper to a wharf near a quiet, cool hotel. New York seemed a million miles away. We were in a new world. That night we dined English style as a negro orchestra played soft music behind a curtain of low hanging vines which seemed to ramble everywhere. It was a peaceful, beautiful night -- one of the last we would experience for several months.

The next evening we resumed our journey. As we climbed out of the harbor, we passed over the U. S. Navy light cruiser, St. Louis, then burrowed into the overcast. At 4,000 feet, our skipper, Captain Gray, went on instruments. Clear weather had been forecast 400 miles out to sea, but that was not the first time in my flying career that a weather forecast proved less than completely accurate. It wasn't the last, either. The air was rough and we had difficulty sleeping.

Quiet and beauty came with the dawn. We flew above the overcast. Below, a billowy sea of clouds stretched to meet the horizon. Occasionally we passed over small holes, through which we could see the cold blue water of the Atlantic. We were looking forward eagerly to our landing at the Azores, but as we approached the islands, the captain made contact with the ground crews and learned the sea was too rough for landing or take-off operations. One clipper had landed there the previous night and was being delayed on its journey to the States because of the high swells.

One of its passengers was Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, enroute

1-25

from London to Washington. The Atlantic has no respect for rank. The Ambassador would have to wait, and we would have to continue to our next destination -- Lisbon, Portugal. The weather deteriorated again as we flew on, but, 26 flying hours out of New York, we touched down and the Clipper was made fast to her moorings. Captain Gray was a tired man. During the long flight from Bermuda, he had brought the ship through the fringes of a hurricane, and had flown 7 continuous hours on instruments. Aviation had come a long way since Lindberg.

We spent the remainder of that day, and the next, exploring Lisbon. The contrast between beauty and filth in that city is something I shall never forget. We were awakened at 3:00 a.m. on the morning of October 28, had a cup of coffee and hired a taxi to take us to our aircraft. It ran out of gas along the way. After what seemed at the time a reasonable amount of American profanity and Portuguese disgust (neither of which did any good), we walked the last mile to the airport and boarded an Imperial Airlines plane for the last leg of our trip. Flying out to sea again, the pilot headed the aircraft north, and began darting in and out of the clouds in an endeavor to avoid contact with any German airplanes. We had been informed that two previous flights on that route had turned into games of hide-and-seek with German scout planes. Each time, the airline pilots had managed to win the game by hiding in thick weather.

At last, we turned east for a "sneak-in" approach to the airport at Poole, England. We weren't sure whether we

1-26

were about to land or be attacked. We arrived at 5:30 p.m., which we later learned was "blitz time". True to form, "Jerry" was overhead. Aboard the launch carrying us to shore we were instructed to remain inside and keep the curtains closed to prevent flying glass from cutting our faces. As we docked and climbed ashore, we felt as if we had arrived on the threshold of Hell.

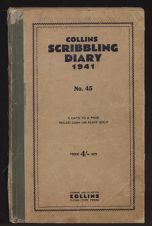

We spent the night in the Royal Bath Hotel, and got our first introduction to the English blackout. The next day, before boarding a train for London, I purchased a diary and decided to keep a record of my impressions in England. Security restrictions would prevent me from logging military information, but I wanted to note personal impressions of the war, for later use. The entries in that journal were often sketchy and ungrammatical, but they tell something of a man and a war. When I look back over them I get to know myself better.

1-27

CHAPTER TWO

OCTOBER 28th, 1940 - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

The train trip took about four hours. Once we were forced to slow down to 15 mph because of a raid some miles ahead of us. On the outskirts of London we saw bomb craters, later, bombed houses. Arrived at Waterloo. The station is intact, except for window panes. They've been blasted away.

We came to the hotel and were given a room on the top floor. (The 8th.) Am bunking with Bob Williams. He left earlier for a visit to a night bombing field. I leave to join him in a few minutes, but first want to note a memorable experience.

At 7:25, I was just climbing out of my bath. The hotel alarm sounded. I dressed as quickly as possible, but before I could finish, I heard the first bomb explode with a strange, sickening "thud" or "crunch". It "touched", as they say here, about a half a block away. I don't think I'll ever forget that sound, or the way our hotel swayed from the shock waves. I wonder if anyone can forget "the first one". A moment later, a second bomb struck in the neighborhood. I couldn't resist the temptation to watch the action, so I opened a window. As I leaned out, a battery of anti-aircraft guns fired a salvo from the street below. The blast was so loud I was sure they had hit me: I pulled my head back inside -- fast.

The all-clear has sounded. Must hurry to join Bob.

2-1

OCTOBER 29th - LINTON-ON-OUISE.

Boarded the train at Kings Cross station in London. It has suffered more than Waterloo, although heavily loaded trains continue to come and go. As they say here, "He (Jerry) can't frighten us."

Arriving at York, I was asked to have a whiskey with a young officer, one of the last to be evacuated from Dunkirk. My escort came along, and we started toward the base. I learned he flew in the last war at age seventeen. We met Vice Air Marshal Conningham, and were shown the Group's elaborate set-up.

The 58th Night Bombers were located nearby so our escort drove us there. (How these people can go from one place to another in total darkness is uncanny! I'm convinced another year will find them with "night eyes"!) We arrived in time for "Guest Night". The 58th was hosting two other squadrons. Jerry hit their field yesterday, killing nine of their fellow officers in the mess hall. I never would have guessed it from their high spirits at the party.

The Wing Commander officiated with great pomp and ceremony until the National Anthem was played. Then, we drank a toast to the King, and the fun began! It reminded me of our Mug Parties. All of the pilots were youngsters who seemed to enjoy rough games. At their request Bob and I joined in.

Everyone, including the high-rankers, took off their tunics and began with a tug-of-war. Later, we played

2-2

"alligator." It's a wild game! About twenty officers face each other, lock arms and join hands, forming a sort of long "cradle." Then, one person dives from a table into the cradle. Everyone yells "Heave!" and he's thrown for-ward. On the average, it took about four "heaves" to reach the end of the line and be tossed headlong onto a sofa or overstuffed chair. I did better than average. I made it in three pitches and landed on a large chair, which promptely collapsed. They laughed like the devil!

About midnight, scattered and torn clothes were gathered up, everyone was mussed up, and the furniture was pretty well broken up. The party was a complete success, so it broke up, too!

These English are wonderful! War or no war, tea is at five, and Guest Nights continue. I fear that Jerry will drop a bomb on the mess hall one Guest Night and account for at least a hundred of England's best night airmen. Even if that should happen (God forbid), they'll die doing what they like to do most, at work or play ... raising hell!

OCTOBER 30th - LINTON-ON-OUISE.

Today, after Bob and I made a few inspections, the Vice Air Marshal had us over for tea. We discussed air tactics and operations procedures. Marshall Conningham is not only charming, but highly intelligent. It's good that he is. The night bombing of Germany, Italy and France is his responsibility.

Later, Bob and I rode in a night bomber to watch the procedure of bringing pilots out of Germany and landing them

2-3

on the field. Navigation is poor, weather is worse. Most casualties occur on or near the airfields upon completion of the missions. The pilots are tired after ten hours of flying and being shot at. Crossing the North Sea, the Alps, and locating a blacked-out target is no easy chore. Then, there's always the long trip home. My hat is off to them!

They seem to like the Berlin missions best. The stories they bring back are fantastic, but they swear they are true. I believe them.

For example, "Penny", a 20-year old Canadian, was in the Berlin area trying to locate his target. When he sighted an airfield below, he pulled a star flare "just to see what would happen". The Germans mistook him for one of their own and gave him a green light to land. Penny squared away for his "approach" and came across the hangar line. Instead of landing, he presented them with half his bomb load. Then, to add insult to injury, he made another pass during which both he and his tail-gunner machine-gunned the field!

The Jerries retaliated by sending eighteen ships to bomb an English airdrome. They inflicted severe damage, but their revenge was less than sweet. Spitfires caught them on the way to the coast. All eighteen were shot down.

Another officer, Wing Commander "Teddy" Beare, has made 37 night trips into Germany and Italy. Returning from a particularly rough mission, he radioed a scrambled message to his home base. When unscrambled it sparked a lot of laughter. It read, "The natives appear to be hostile."

2-4

Incidentally, he has been nominated for the Distinguished Flying Cross for long, hard service. Rightfully so.

OCTOBER 31st - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

After a late dinner with Vice Air Marshal Conningham, Bob and I returned to London, made our reports and spent some time surveying the damage in our neighborhood. Many places in the area have been bombed. So far, the Embassy stands.

After dark, I went to a restaurant a few hundred feet away from our hotel. Having been here for a few days, I thought I could navigate the blackout like the natives, so didn't take a flashlight. How stupid! I collided with at least a dozen people. They seemed to come out of no-where. Before you can duck, you're nose to nose with some-one.

At the restaurant ... another surprise. Some people dressed in pajamas and carrying bedding stepped out of the elevator. By day it's a restaurant -- by night, a shelter.

The subways (or "tubes", as they say here) are also used as shelters. Women and children crowd into them, spending hours underground, sleeping within a few inches of the tracks, while the trains continue to run as usual.

The spirit here is strong. It's not uncommon to see most of a huge tenement gone, the windows in the remaining portion broken, doors knocked flat -- and a tattered Union Jack defiantly waving in the wet breeze. I ask "When will it all end?" They don't know, but they assure me they will stand on and on. "'He' can't whip England", they say. I

2-5

hope they're right.

NOVEMBER 1st - BOURNEMOUTH, ENGLAND - 12:05 P.M.

A German plane is over the town. I can see him from the window. He has buzzed the hotel twice. Soon, he's bound to locate his target and drop a "stick". The Germans have been after the docks here, but this one seems to be looking for something else --maybe a railway station or supply concentration area.

I have lost count of the days. They all seem alike ... rainy or just cloudy. Today it's raining.

He's pulling up a bit to make a turn. The people in streets are looking up, waiting for the "stick" to fall. They seem nervous. Can't blame them. I am, too.

I can hear .30 calibre machine gun fire. It's punctuated by an occasional burst from a .50 calibre. The ack-ack boys can't get on him. Too low. Where are the Spitfires?

He's making another pass! People are running for cover. The guns are going faster now. The Jerry doesn't seem to mind. It looks like a sighting run. Maybe he'll let go this time. Still no Spitfires! He's coming fast as hell! Must be doing at least 400 mph.

Passed overhead! Silence. Can't panic. People below are quiet. Can't hear the motor now. Maybe he has gone away ... Too good to be true! There he is again, coming out of the clouds! The ground guns are going all out now! How can they miss him? They do. He drops one. If we hear it --no danger. If not -- no worries.

Thank God! We hear the explosion! Building shudders.

2-6

Downstairs, plate-glass window shatters into street.

Hear a woman crying - not loud. Now a baby cries, too.

A new sound -- rapid, short bursts of eight .30's, followed by the whistle of a fast fighter. Spitfire! People cheer. Planes go out to sea. Everything is quiet again. The rain is coming down in torrents. I reach for a cigarette. My hand trembles.

LATER -

Four bombs dropped on and near concentration depots. Few casualties. One JU-88 crashed 15 miles from Poole. Crew killed. No RAF losses.

NOVEMBER 2nd - LINTON-ON-OUISE.

New DFC's for two bomber pilots. One to Wing Commander Sutton, the other to Wing Commander "Teddy" Beare.

The fighters are receiving most of the praise on the front pages. They are doing splendid work. They are old men at 25. But, these boys at the Bomber Stations are the work-horses. Four round trips to their targets equal a water flight the distance of the Atlantic. They are carrying the war to Germany and Italy at night! The misery they deal to the population of those countries should serve to let them know what London is suffering.

A special mission is in the works. Everyone wants to make it. They're matching coins to determine who will go. As an observer from an "un-involved" nation, I can't participate in the matching – damit! After all the bombing these past few days, I don't feel so "un-involved". At any rate, it promises to be a great surprise. I hope it will be a

2-7

happy one.

NOVEMBER 4th - SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND.

One crew reported lost in the North Sea. I wonder about their families. There is so much death. Been thinking a lot about Fluffy. Hope she's well. In many ways I wish she were here. I'm lonely as all hell.

NOVEMBER 6th - SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND.

1,000 bombs fell on England this day.

NOVEMBER 9th - SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND.

The Big Surprise ... The Munich Beer Hall was bombed! Such a pity Hitler was not trapped inside. It was close, but not quite close enough. We knew the opportunity was going to arise long before the raid. England also has a spy ring.

NOVEMBER 11th - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

Typical English weather today -- cold, damp and bleak. Our room is on the top floor and we have a good view of the city. London looks sad.

Barrage balloons, although firmly anchored in one spot, seem to move in and out of the low-hanging clouds. They look like huge sausages floating around in mid-air, but they're a welcome sight to all of us on the ground. They're a menace to dive-bombers.

It's almost "blitz time". In a few minutes we can expect the Me-110's to drop their bombs from somewhere around 30,000 feet. Wonder where they'll hit? We won't see the planes. They'll be above the weather. No doubt we'll hear the bombs. They always whistle when released so high. It's

2-8

a strange thing to consider, but it's all too true -- bombs fall anyplane, on anyone! Hitler will probably send many on this raid. It's Armistice Day.

NOVEMBER 12th - LONDON.

Good news! The night was quiet.

Early today 150 enemy aircraft approached the Dover coast, but were driven back or scattered. The Italians sent some planes along on the raid, but they were of "1937 vintage" -- wooden and obsolete. As the RAF Hurricanes scattered the formation, 'twas a bad day for the "I-ties".

The RAF boys have been waiting a long time for a chance like this. They seem to hate Italy worse than Germany. We heard later that some of the captured Italian bomber pilots were carrying wine, cheese, bayonets, and hand grenades. I guess they wanted to be prepared to stay a while. Most of them will -- the captured ones in prison camps, the others in the North Sea where they fell.

NOVEMBER 13th - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

By actual count 1,000 bombs were dropped on London today. How long can this city survive?

Seventy per cent of many important docks have been shot away. Mile after mile of waterfront has been damaged or destroyed. Millions of people are living underground. They bring their children out for fresh air for a short time around noon, then take them back into the "tubes" by 2:00 p.m. Two million persons have been evacuated; others are leaving at the rate of 1,000 per day.

Not many streets have escaped the fury of a bomb. Yet,

2-9

in Hyde Park, hundreds of tame pigeons pace the walkways looking for crumbs of food. With all the shortages, even they must feel the effects of war.

The only living things thriving here are the lice and mice.

NOVEMBER 14th - WARMWELL, ENGLAND.

What a day this has been! Bob Williams and I came here by train for a look at the Central Gunnery School. This time, we departed from Waterloo Station which has suffered heavily during recent night raids. While we were waiting on the platform this morning the alarm sounded. We just sat. No need to run. We've learned that no one knows where "the safe place" is.

We arrived here shortly after 4:00 this afternoon.

Bob and I were both "wounded" today! What the whole damned Luftwaffe hasn't been able to do in several weeks, a British WAAF accomplished within a minute! As we walked out of the station she greeted us with a snappy salute, re-porting for duty as our chauffeur. Returning the salute, Bob dropped his "tin hat" on his foot. I knew it must have hurt something awful, but I had to laugh. It was funny as hell! As he hobbled to the car, it struck me even funnier. What a situation! The poor girl was obviously quite embarrassed (we were the first American officers she had seen). As we settled onto the back seat, Bob was muttering some-thing under his breath and I was trying, without much success, to stop laughing. I didn't stop, until she gingerly shut the door - on my finger! Then she was really upset!

2-10

I managed to keep from crying, somehow. Bob was a good sport. Even after we reached the base dispensary where they relieved the pressure by drilling through the nail, he didn't laugh once - at least, not out loud. I may never laugh again.

Tonight we dined at the Officer's mess and learned we missed a good show this afternoon. About an hour before we arrived from Bournemouth, a JU-88 made a run on the base. A 20-year-old pilot named Marsh took his Spitfire up to stop him. I'll never understand how he survived that clash. He made a total of four passes at the Junker. On the first three he couldn't seem to get a decent shot, but the German gunner scored several hits on the fighter, inflicting serious damage. On his fourth run, Marsh and the German began firing almost simultaneously. A stream of bullets hit the windshield of the "Spit" directly in front of the youngster's face, but the bullet-proof glass held, and the slugs were deflected. The JU-88 crashed in flames, killing the entire crew.

Fighting is more luck than I thought.

Someone asked Marsh if he had heard the account of the fight on the BBC news. "I don't listen to the news," he said quietly. "I make it."

I'm impressed by these youngsters! In fact, there's only one thing about them that bothers me. They have a fetish for collecting our "U.S. "blouse buttons. They don't just take them; they always trade, fairly. One RAF button for one US button. Our uniforms are beginning to look a bit strange. I only have a couple of US buttons left. Bob

2-11

has none.

NOVEMBER 15th - WARMWELL, ENGLAND.

Had a most interesting day. England's gunners are trained here and Jerry has tried for the base many times. So far he's had little luck.

We rode along on a practice gunnery mission this morning.

Tonight we go to London via Bournemouth. London received an extremely heavy bombardment last night. I'm glad we were out of town.

NOVEMBER 16th - WARMWELL, ENGLAND.

Our plans to return to London were changed at the last moment. We were lucky. Bournemouth was hit hard at the very time we would have been there to change trains. Fifty people were killed. We seem to be one step ahead, or behind, the bombing. I hope it remains that way.

We had some "visitors" here last night, too. The Germans passed overhead, en masse. We all stood by for the attack, but it didn't come.

Coventry was bombed terribly! Jerry was trying for the airplane works. Beyond a doubt, it was one of the worst blows of the war. Civilians bore the brunt of the attack. Thousands were killed! The Germans are really pounding now. 500,000 pounds of high-explosive and incendiary bombs were literally dumped out over Coventry in a let-it-fall-where-it-may style. What next?

LATER -- SAME DATE - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

It took only five hours to get "home". After living

2-12

where there is no heat, a warm room is welcome! Our street was bombed while we were gone. As we returned this evening, we stopped for a while to watch crews dig for the dead.

I think I'll stop bathing here. Just like our first night in this room, I had just stepped from the tub this evening when the alarm went off. I threw on my robe, turned out the lights and opened the window to watch the action. Bob had gone out for the evening. I was alone.

I heard the drone of the engines approaching above the clouds. Then the ack-ack guns started blasting from all over the city. Jerry was looking for his target. I just sat and waited. The sound of the motors seemed to be the only thing that mattered. I followed it as it came closer. Listening and waiting -- there's nothing else to do. The gunfire increased as the drone deepened. I thought, "It can't be overhead." Then, the inevitable happened .., the loud whistle ... that familiar "sickening thud", and the building quivvered. I listened for the second one. It hit. I relaxed and turned on the radio to hear the news.

The RAF had bombed Hamburg again. I wondered how the people there react during raids. Probably about the same.

NOVEMBER 17th - CUMBERLAND HOTEL, LONDON.

Today is Sunday -- skies are clear and the air is brisk. In Coventry they're burying their dead and asking for revenge at the same time. Dear God! What an experience, to sit before this huge stage watching the war rage. To see the misery and death it brings is a rare, but dreadful, experience. I should feel soft, but I don't. On the contrary, I

2-13

find myself wanting vengeance. The longer I'm exposed to this life, the more I hope to see the day I can personally deliver at least partial payment to the people responsible. I've had all I want to take on the ground. I'm ready to change planes with the Hun, and do a little dealing from the sky. For what it's worth, I believe that we Americans, if allowed to fight, can end this war. The English can "take it", but they need help in "dishing it out". We can "take it" AND "dish it out" -- American-style. The Germans won't like that if they ever get a taste of it. I shall remember these days. Who could forget?

SAME DATE - SAME PLACE - 9:00 P.M.

Spent a quiet day walking around the city. What a mess! I am very lonely and think often of Fluffy. Hope she isn't too worried about me. Maybe I'll dream about her tonight.

NOVEMBER 18th - SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND.

Can't say where we are tonight. This station is so secret they have assigned an extra RAF officer to escort us. Lord Beaverbrook gave us his car for transportation. Several new aircraft are being tested here. One of them, the DB-7, is regarded as a potential answer to the German night bombing. Another plane they call the "Typhoon" is being tested. I'm certain it will make a good reputation for itself. Beautiful!

We ate an early supper in an underground restaurant. I'm not going to leave the hotel tonight. It's too dark for me to navigate.

NOVEMBER 20th - SAME PLACE.

2-14

Going to bed early tonight. Tomorrow Bob and I are off to Scotland for a peek at one of the training fields there.

NOVEMBER 21st - ENROUTE TO SCOTLAND.

We're on our way at last. For a few minutes this evening, I wasn't sure we would make it. I left for the station fifteen minutes ahead of Bob, to buy sleeper tickets. We were to meet at the ticket office located just outside the station building. Before Bob arrived, we were raided, and they moved it inside. The station has been touched several times in the past, and could have been the target for tonight. I'm sure everyone there knew it, but instead of running away they stood still and looked upward, waiting for that God-awful whistling sound. The raiders approached and passed overhead. Nothing happened. As the motor-noise faded, the travelers began to move again. At five minutes to departure time, Bob hadn't shown up. I started toward the front entrance to see if he might be waiting there. We ran into each other in the crowd and had to hurry to make the train.

NOVEMBER 22nd -- ENROUTE TO SCOTLAND.

A bit of excitement last night as Bob and I went to-ward the diner. (These trains are strange to us. Every aisle seems to be filled with luggage, and maneuvering through them is a chore. Also, there are several baggage cars, scattered without any apparent reason between the passenger cars.) The train, on its way through the Mid-lands, where Jerry has been working intensely the past

2-15

four nights, came to a sudden stop. The lights went out, and I knew we were in for it. I opened a window and saw the crew cover the engine-lights with a black cloth. Searchlights were playing about in the sky. Everything was quiet, except for the sound of motors overhead. I noticed they were out of synchronization (a trick to confuse the rangefinders). I was able to follow the raiders' course by watching the bursts of ack-ack fire and the "on and off" of the searchlights. An eerie sight!

Our fellow passengers spoke in whispers, as if afraid the sound of their voices might attract the Huns' attention, and bring down a rain of bombs. But the "rain" never came. The bombers passed over toward some distant target, and we began to move toward our destination.

Dinner was very late last night.

NOVEMBER 23rd - SOMEWHERE IN SCOTLAND.

We arrived here seven hours late. The only transportation running on time these days is operated by the Germans.

We're quite near the border of Northern Ireland. Canadian fighter squadrons are sent here to rest after completing eight weeks of duty around London. New pilots are sent to practice gunnery.

This is a beautiful place. Looking out over the hills dotted with grass-covered huts, with smoke rising peacefully from their chimneys, it's hard to realize men come here to learn the art of killing. On the other hand, all the pictures I have ever seen of Bavaria were beautiful, too.

NOVEMBER 24th - ENROUTE TO LONDON.

2-16

Our "first" anniversary! One month has passed since we left New York. How much has passed under our wings, and over our heads, in such a short time. It seems like a lifetime.

Liverpool and Southhampton have been touched again. According to news reports, the Southhampton docks were hit very hard. Fires were numerous throughout the city, some burning out of control for hours. Thirty million pounds of badly needed foodstuffs went up in smoke. The Fire Chief was discharged for so-called "inefficiency." It's probably a happy thing for him. Who could be expected to cope with so many fires, broken water mains, cluttered streets, plus German bombers? I'm sure he can use some rest.

NOVEMBER 26th - LONDON.

Bob and I have moved to a flat. The hotel was getting too crowded. The streets are crowded, too, despite an incident just two days ago, when a dive-bomber made a strafing run on some pedestrians. The people accept danger as a matter of fact, and go about their daily tasks, as best they can. Some stores don't even close during raids any more. They simply lock the street-level doors, repair to the basement, and resume business. Some display signs reading "Business As Usual". Bombed stores and offices carry "To Be Let" signs. Many streets are blocked by rubble, and detour signs appear everywhere. I haven't walked on a single London street which hasn't suffered some damage.

The people are surely a determined lot. They rebuild,

2-17

repair and re-appear after every raid. Many of the buildings are completely beyond repair. When this war is over (if it ever is) there'll be a helluva bunch of parking lots in this city that weren't here before.

NOVEMBER 29th - LONDON.

I visited around the city today with one of the London Fire Brigade Chiefs as my guide. Among the points of interest was Dick Turpin's Pub, formerly a hideout for the notorious highwayman. The building is 400 years old! Also, we toured the East End, passed the Tower of London, and crossed the Thames several times.

Early last September the Germans staged a raid, concentrating their efforts upon the waterfront. The bombing was continuous from 5:00 p.m. until dawn of the next morning. Many docks and millions of pounds of goods were destroyed. Hundreds of persons were trapped until firemen rescued some by boat. A few managed to swim to safety. Others were drowned. The docks of London are no more.

Our guide believes Hitler had the war won, had he continued such ferocious raids. But, he slacked off - and failed.

Later we visited the Main Fire Station and watched the firemen at rescue drill. They can't seem to get enough practice. When I learned that three hundred firemen have lost their lives since the September Blitz, I can understand why.

DECEMBER 7th - LONDON.

The last two nights have been quiet. Tonight there is a clear sky and a bright moon. If I have learned any-thing about German tactics, I have a feeling we're in for

2-18

some fireworks.

I'm currently reading Harry Harvey's new book, "THE DAMNED DON'T CRY". It is about Savannah, Georgia, so I'm getting a little homesick. Savannah seems so far away, yet so near. I can see Bull Street in my mind at times. Last night I dreamed of a large chocolate milkshake. We rarely get milk or butter here. Guess I had better stop dreaming.

DECEMBER 8th - LONDON - 11:00 P.M.

Hell is on the wing! The sky is dripping blood and screaming thunder! I thought I had become accustomed to the "Blitz", but up to now what I have experienced has been trivial. This is the "real McCoy"! Will write more when the bombers leave. Too much to do now.

DECEMBER 9th - LONDON.

Six-thirty was "lid off" time. Bombers came in continuous waves for 7 1/2 hours! The Germans hit London with full power. They came early and stayed late. It was an incendiary attack.

At 6:30 p.m. I stood on the hotel roof, watching the bombers jockey back and forth over the city. Off to one side, the sky lighted up. Flares were burning in groups of two. A ground battery opened fire, but failed to hit the mark. The flares continued to burn, dripping long streaks of fire as they swayed to earth.

London and its artificial lighting!!

Above the flares, the bombers wove in and out - back and forth - drone-drone-drone. Gun batteries followed the

2-19

sound, and fired incessantly. Yellow blasts went off so near they jarred the entire building. I watched the bursts pit the sky like hundreds of shooting stars.

During a raid you're convinced the bombs are about to fall soon. Where? That's the big question! No need to run. He can't see you. Wait. That's all you can do ---just wait. The droning gets louder. More batteries open fire. The whole city is shooting. Fireworks are everywhere! Finally it comes -- a long, drawn-out swish. Then, a flutter. Experience has taught you the meaning of this sound. It's a stick of incendiary bombs, loaded with fire. They hit and ignite. Men run for them. Women throw garments over them. Taxi drivers stop and kick them out. Everyone fights the incendiaries.

Last night I heard a flutter, coupled with the drawn-out swish, as the bombs crashed to the street below our building. I hurried downstairs to see them. The street was burning. Men were trying to stamp them out.

An elderly gentleman screamed that our roof was on fire. Remembering that my clothes were on the top floor, I started back upstairs. I was joined by a fire warden. At the roof door we separated, to search opposite sides of the building. "All clear on my side" I yelled, and started back downstairs. He came through the door a moment later.

Suddenly we heard a high-pitched, shrieking whistle. The warden screamed "For God's Sake, Captain, take cover!" I dived for the landing, just a few steps below. The warden and I hit the floor almost simultaneously and huddled

2-20

together, holding each other. The bomb fell like lightning. It was not an incendiary, but a high-explosive missile. It crashed across the street. We were safe. The tension relieved, we began to laugh. Then we looked up and realized that we had been crouching beneath a skylight for protection against a bomb! Funny what people do when they're excited. Instinct. Just plain damned fools.

DECEMBER 9th - LONDON.

Another day - another dollar. London continues to burn. Most fires are under control, but many still smoulder.

Bob and I walked down to Baker Street, which is almost covered by broken glass blown out of shop windows. Work squads were busy cleaning up the debris. Firemen and rescue teams were extinguishing small fires as they searched for bodies.

DECEMBER 11th - LONDON.

Have been so busy with paper work there hasn't been much time for anything else. Hope I never see the day when my flying will be confined to a desk!

Today Bob and I were forced to detour to reach the Embassy. Some buildings on Baker Street are roped off because of the possibility of collapsing. Traffic has been discontinued.

DECEMBER 12th - LONDON.

One raider came over today, touched a shopping center and killed several people. The past few days and nights have been relatively quiet. This was one of those "lest you forget" reminders that the war is not over.

2-21

Tomorrow we leave town for a few days. After all this paper work, I can use a vacation.

DECEMBER 16th - LONDON.

After being away, even for such a short time, I notice a difference in the people of London. They seem outwardly composed, but in the wake of last Sunday's big raid, there is an air of added nervousness. I feel it, too. Whenever I hear falling bombs, my stomach tightens up worse than it did at first. It's like walking down a dark alley, with numerous unseen thugs swishing out at you with clubs. You can hear them, but don't know which way to dodge.

DECEMBER 19th - LONDON.

"Home" for a day. We leave again tomorrow for another inspection. Traveling is hectic and tiring, but it beats hell out of sitting behind a desk in the Embassy. I've been writing most of my reports (except the confidential portions) on the trips back to London. I may be the first officer in the history of the Army to get a Purple Heart for writers' cramp.

Today we visited the "Holy of Holies" (that's what the RAF boys have named the Fighter Command Headquarters). It is elaborate and efficient. Twenty-six men and women work at one plotting table. About half that number stand on platforms, directing fighter operations. We watched the progress of a German raider as he circled London, unloaded his bombs and started for home. The RAF sent fighters after him, but I didn't find out if they got him. He made it out of London safely.

2-22

DECEMBER 23rd - COVENTRY, ENGLAND.

During the past two days we have seen a lot of this part of the country. The scenery is beautiful, and under less trying circumstances our journey would have been extremely pleasant. Even in these days it is easy to experience moments of fanciful enjoyment.

We passed through Banbury (of the Banbury Cross and the Cock Horse stories), Shakespeare's Stratford-on-Avon and countless other quaint little towns nestled in the hills. They all look alike, with their "fair book" thatched roofs and narrow, crooked streets.

Each village has a pub. They, too, are similar --with winding stairs, narrow halls and high, comfortable beds. The managers are almost always elderly women; the men have gone away.

We've been traveling by car. Frequently we've been forced to ask for directions. All sign posts have been removed from the roads, in case of enemy invasion.

Coventry is a wreck! In one raid, 30,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and 3,500 persons were killed. (The papers said "a few hundred".) Hell! There were 400 killed in one hotel! As fire gutted the business section, workmen dug long ditches in which to bury the dead. One of the oldest cathedrals in England was ruined.

Christmas shopping was in full swing when we arrived. Women and children were climbing over wreckage on the streets and sidewalks to buy small gifts. Several times since we left the States I've found myself wondering if God has gone away. When I see spirit such as these people

2-23

display, I know He hasn't.

P.S. My escort, Squadron Leader Tweedle, and I found a "Christmas present" this evening. We went to the third floor of a ruined equipment depot to look at the damage. I saw an object lying in a pile of debris, and asked what it was. He told me it was a "Jerry Wing Commander", issued to the officers of the RAF as part of their equipment. Actually, it's an ordinary chamber pot with gold stripes around it! I'm taking it with me to London. With the plumbing what it is these days, I may need it.

CHRISTMAS - LONDON.

No mail, no cables, no nothing. Just memories of Fluffy and Fuz. I'm alone. Bob is out of town. He fixed a few "funny" decorations before he left, but they don't seem too funny now.

I had coffee, olives, crackers and soup for lunch. This evening I walked to the Cumberland Hotel, expecting to eat dinner. When I got there I found every seat and table had already been reserved. Nearly all of the eating places were closed, so I had "Christmas Dinner" in a "dirty-spoon" cafe. Guess I'll stop writing and go to bed.

DECEMBER 26th - LONDON.

Christmas turned out better than I thought it would. Just as I was getting ready for bed, Bob came back. He had picked up a bottle of Canadian Club, so we had a few. We drank to the United States, to our friends, to our enemies, and then drank the rest of the bottle for ourselves. I'm glad there was no raid last night. We were just a wee bit tipsy.

2-24

DECEMBER 28th - SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND.

Out again. This mission is fun, in a way, but the damned paper work is beginning to irk me more and more. All day, I look, listen and take notes. At night, I write until 10:30 or 11:00 o'clock. I don't know how long my mashed finger is going to hold out. Damn that WAAF who closed the car door on it!

I've lost nearly all my blouse buttons and ornaments now. Some of them have gone a long way with their new owners. One of them is being worn by a fighter pilot who has won the DFC. A Polish fighter pilot killed in action had another.

A 19-year-old New Zealander, who has brought down eight Germans - one as we were driving to the field - has one of Bob Williams' insignia. Just to keep things even, Bob and I both have a WAAF button, although I don't like to look at mine. It reminds me of my finger, and I get mad. Women in war - umph!

DECEMBER 30th - LONDON.

I'm still one jump ahead of the Blitz! Came back this evening to learn the city was hit by another "fire-stick" attack Monday night. From all accounts, the German intended to "Coventrize" London, but foul weather moved in, and he lost the target. No doubt he will be back.

JANUARY 1st, 1941! - LONDON.

HAPPY (?) NEW YEAR!

I went to a party last night and really enjoyed it. From the way I feel today, I "enjoyed" it a little too much.

2-25