[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

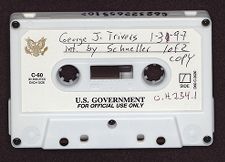

George Joseph Trivers, oral history edited by Robert J.

Schneller, based on interviews conducted on 31 January 1997 and

29 July 1997, in Room 224, Health Care Institute, 1380 Southern

Avenue SE, Washington, DC 20032. Mr. Trivers entered the U.S.

Naval Academy during the summer of 1937 with the Class of 1941,

and left after approximately three weeks. The interviews focused

on Trivers's youth and experience at the Academy. Robert J.

Schneller, Jr. conducted and transcribed the interviews and

prepared this oral history, which is a synthesis of both

transcripts, plus notes made by Mr. Trivers, and notes made by

Schneller during conversations with Mr. Trivers. Mr. Trivers

reviewed this document in its present form.

Schneller: Generally in an oral history like this, it's

traditional to begin at the beginning. So the first question I'd

like to ask you, Mr. Trivers, is where were you born and raised?

Trivers: Very good. I was born in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania.

Schneller: What was your birthday?

Trivers: April 24, 1917. At age four, my father left us,

left my mother, my sister (who was nearly two years older than

me), and me. We came from Philadelphia to Washington to start a

new life. These were days of segregation, so it was difficult to

find--I shouldn't just say work--to find a profitable way of

living. My mother had attended Miner Normal School, which was

the parent of Miner Teachers College. She did substitute

teaching in Birney Elementary School from time to time and worked

as a hotel maid, but her income was spotty, so money was a

problem with us. When I was appointed to the Naval Academy, I

was very concerned about how she and my sister would fare, since

I was the breadwinner. And that didn't help me at all, either.

But I was torn between doing something important to our group of

people, which going there and doing your part would have been. I

was torn between that and staying with mother and sister. I

finally decided one day that I had to go to Annapolis. And the

entire time I was in there, Congressman Mitchell never contacted

me to find out any of the difficulties or injustices that I was

experiencing. So that didn't help me either. I just felt he

wasn't doing what he should have. Plus, to appoint one out of

eight, and not even a second one, which would have been a

classmate, a roommate; not to have done that was something I

couldn't understand either.

Schneller: You were living in Washington when you were

appointed?

Trivers: Yes. I had attended Birney Elementary School, one

of the two elementary schools on our side of the Anacostia River.

Birney was the school for us on the south side of the Anacostia

River, the other being Garfield Elementary School. We had no

junior high or senior high with doors open to us until 1955; a

result, I think, of Brown v. Board of Education.

I graduated from elementary school and entered Dunbar High

School in 1929. I attended Dunbar High School for four years and

graduated on 8 February 1933. I was valedictorian of the

February class. (The February and June classes were separated.)

In September 1933 I matriculated at Miner Teachers College.

During my four years there I was fortunate to receive aid through

the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration's National Youth

Administration (NYA) project. I received nineteen dollars per

month. In return for this financial aid, I worked at the school.

I majored in science and mathematics. My grades were high enough

to excuse me from taking the written examination required for

entrance to the U.S. Naval Academy. I was to graduate from Miner

Teachers College in June 1937. [He did, in fact, graduate as of

that date, but was at the Academy during the graduation

ceremony . ]

Congressman Mitchell was angry at my mother because he

wanted her to have me withdraw from all courses that I was taking

that wouldn't promote my background for the Naval Academy, which

showed he didn't even know what was going on.

Schneller: Were you interested in going to the Naval

Academy?

Trivers: No.

Schneller: How did this come about, this appointment?

Trivers: I had no interest in military life. I was mixed

up enough with the life I had. But it was just an opportunity to

do something productive, I thought. Racial strife goes far back,

not only for us, but for others. Each group seemed to have their

own problems in trying to blend into mainstream society. All of

a sudden, Congressman Mitchell called for his eight appointees to

come to his office. Mitchell had selected eight of us for

appointments to West Point and Annapolis. Colonel Atwood [COL

Henry O. Atwood, U.S. Army Reserve, head of the Dunbar High

School Cadet Corps] was instrumental in contacting and assembling

the prospective appointees. Mitchell held several meeting with

us in his office. The eight appointees were formerly Dunbar

students, including James D. Fowler, who graduated from the

Military Academy in the Class of 1941.

Schneller: Had either Atwood or Mitchell approached you

earlier about an appointment to the Naval Academy?

Trivers: Before the first meeting in the Congressman's

office, neither Mitchell nor Atwood had ever talked to me about

going to the Naval Academy. The summons to the meeting, which I

received through Colonel Atwood, came like..a bolt from the blue.

None of us knew anything about who was to be chosen, or why. It

wasn't even made clear which of us were to be appointed to the

Naval Academy and which of us were to be appointed to the

Military Academy. It was a hurried meeting. We were simply told

that we would be appointed. I was never asked whether I wanted

an appointment. I didn't know anything about the Naval Academy.

In. fact, I didn't even know that rooms were equipped for two. I

had no idea of the regulations. The book of regulations--

Schneller: Yes.

Trivers: We didn't know there was such a book. We were

totally ignorant about the military life. Really, though, I

liked out of doors. I grew up in Anacostia, which was sort of

rural; tadpoles, frogs, rabbits, squirrels, opossums, chipmunks,

and so forth. And so to go to the Naval Academy and spend hours

Sailing on the Severn and rowing, the gymnasium--I had plenty of

Opportunity to think there, and there was a chance to do some

things that were interesting. But apart from the way of living

that I had been experiencing, I accepted it because I felt it was

a chance for me to do something worthwhile for my group of

people.

Schneller: Admiral Chambers [RADM Lawrence Cleveland

Chambers, USNA Class of 1952, the second African American

graduate of the Academy] had told me that after Wesley Brown

graduated, Colonel Atwood wanted to continue the momentum of

having African Americans at the Naval Academy. Do you think back

in your case, your appointment was part of.a push from within the

black community, or between Colonel Atwood and Congressman

Mitchell, to break the racial barrier at the Academy, a conscious

effort on their part to do so?

Trivers: Yes. Yes.

Schneller: Did they discuss this idea with you before you--

Trivers: No discussion. I don't remember now what we

talked about when we went to his office, but it was nothing

productive and nothing pertaining to what would be helpful for

us; for whoever would be appointed to go. They seemed more like

social gatherings. They were brief. Then, "So long. I'1l1i see

you Tuesday."

I was in favor of breaking the color barrier at Annapolis,

as with others who fought the fight versus black seats,

lavatories; versus the fact that you couldn't enter certain

schools. I was disgusted with that. So to get a chance to go to

the Naval Academy to help destroy this barrier was important to

me. I would have been selfish to refuse, yet I wasn't totally at

ease physically or mentally, because I never knew what to expect.

I learned of my appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy through the

newspaper. I was surprised since I had absolutely no information

from any other source. I had not heard from Congressman

Mitchell's office since our last meeting in his office.

Schneller: Did you ever have a conversation, before you

went, with James Lee Johnson? {Johnson was an African American

who Mitchell appointed to the Academy in 1936, and who was

dismissed during his plebe year.]

Trivers: No. James went to Dunbar ahead of me.

Schneller: He entered the Naval Academy in 1936.

Trivers: Thirty-six.

Schneller: And after he ended his first semester, he had a

grade of something like 2.4 in English, which was just below

passing, and so the academic board voted unanimously to take him

out on the basis of academic deficiency. Congressman Mitchell

investigated his case, and according to Congressman Mitchell,

found that Johnson had been railroaded out of the Academy because

he was black. From what I gather reading about Johnson, he

seemed like a mild-mannered individual.

Trivers: He was.

Schneller: But there was; he had to put up with a lot of

racially-motivated hazing. People would actually strike him at

the mess table; well, actually, one time somebody tried to shove

him out of his seat at the mess table, if I have my facts

straight, and he responded by calling that person a son of a

bitch, cause he was angry. This was used against him.

Trivers: Of course.

Schneller: It was a conduct matter that, in addition to his

academic deficiency, was used by the Naval Academy as the basis

for kicking him out.

Trivers: Yes.

Schneller: There was a hearing. And there were other

midshipmen present at the table during the event in which he got

shoved out of his seat. There was his story, and then there was

another story that said that he swore at these other midshipmen

for no reason. And it became his word against their word. The

Naval Academy went with the view of the other midshipmen, and he

had to leave.

Trivers: Naturally I was not part of this.

Schneller: Yeah, you would have come during the summer of--

Trivers: Thirty-seven.

Schneller: Thirty-seven. And he would have left just

before.

Trivers: Just before, yes.

Schneller: I was just asking whether or not you had had a

chance to talk to him before you started, just to get an idea of

what to expect.

Trivers: That's what made me angry, too. I never heard a

word of anything relating to Johnson's experiences. He was not a

Classmate, but he was at Dunbar High School when I was there.

[Johnson graduated from high school in June 1933, then spent

three years at Case School of Applied Sciences in Cleveland.] 1

pictured him as a very, very self-controlled individual. You

never know how much a person can withstand, when it comes to

torture and so forth. But he was quiet and, well, to me, always

self-controlled. I had no social contact with him, but he was at

Dunbar when I was there. So what little I saw of him showed that

he did have his behavior under control.

Schneller: In our earlier conversation, you mentioned that

the Commandant of Midshipmen asked you to resign. Was this as

soon as you got there?

Trivers: This was a few days afterwards.

Schneller: And you would have gotten there in June of '37?

Trivers: I came in in June of '37, in the middle of June.

I don't remember the dates, now, but it was before my graduation

from college, so it was the early part of June in '37.

Schneller: And a few days later the commandant asked you to

resign, he called you into his office?

Trivers: Called me into his office. I didn't have the

slightest idea of why he had done so, but he was quiet and calm

about it. No bad language, or anything. There was nothing

emotional at all. But we just disagreed. And of course, I

walked away pleased, not knowing that, not far down the line, I

was going to resign anyway, because I got disgusted with it.

Nothing was being done.

Schneller: On the part of Congressman Mitchell?

Trivers: Yes, Congressman Mitchell, yes. Congressman

Mitchell got angry with my mother for not withdrawing me from

classes at Miner Teachers College, even though I was in the

fourth year, looking forward to graduation. If he was angry with

her about that, it would make you question his other decisions

and attitudes. And, of course I was sort of an event. I went on

with the program because I felt it was something worthwhile. And

at that time, I didn't know that he wasn't going to appoint

another person. He did appoint Paul Cooke [Dr. Paul Phillips

Cooke] --that's whose name I gave you--as an alternate later.

[Mitchell had nominated Cooke in March 1936. See the Pittsburah

Courier, 28 March 1936, p. 1] But I don't know anything about

the others; that left six others. And Paul was a very, very

intelligent fellow. But when it comes to facing the Academy

exam; I don't have the slightest idea how much math he had. I

was fortunate to avoid the exam because of my grades at Miner

Teachers College.

Schneller: Let's step back a minute, back to the interview

you had with the Commandant. He told you that he wanted you to

resign, as you said earlier, because there was no place for a

black officer in the Navy, and you had said that, as he was

Speaking, you couldn't tell from his manner whether or not he

harbored any racial prejudices.

Trivers: Yes. It was an ordinary conversation. No raised

voice. Nothing to give an indication of any inner feelings. It

was like a business decision. I felt good that I didn't have to

resign, because this was the beginning of my stay, and I had

accepted the appointment because I felt it was a chance to do

something productive. So when he and I finished our meeting, I

was pleased that I was still in. But it didn't take me long to

add up the problems I was having, and the lack of action. I

don't what action should have been taken, but I do know that

there was no action at all. I was paying the price.

Schneller: What were some of these. problems?

Trivers: Oh, well, for instance, you expect to be spat on,

I guess. I shouldn't say expect to be, but when you're with

thousands--hundreds--and among them are some who hate deeply, you

don't know what to expect.

Schneller: Were you spat on?

Trivers: I was spat on. "Nigger" and other derogatory

terms were frequent.

Schneller: These were your company shipmates?

Trivers: Yes, yes, plebes.

Schneller: Did upper classmen do this kind of thing as

Trivers: The upper classmen--

Schneller: They wouldn't have been back yet--

Trivers: They were involved with other things. No. I

think the second year men were on the cruise, I believe,

initially. And from them I got the problem of cleaning the rails

under the bed, or the boards behind the drawer in the chest of

drawers, or the corner of the floor of the shower, or the dirt in

10

the ceiling light, which can be reached only by getting up on the

table and reaching down from the ceiling.

Schneller: So they were going out of their way to find

infractions for which they could give you demerits; deliberately

going out of their way to--

Trivers: Yes. Even sticking your finger in the overflow of

the wash basin. You're bound to meet something in there that is

untidy.

Schneller: Did you have a roommate or did you live alone?

Trivers: No. That was another thing. Your room was

equipped for two.

Schneller: Right.

Trivers: And when they come to examine your room, they

examine all parts of it, and they can get you. Because you're in

there by yourself, but you're responsible for the entire room.

The first day that we went to gym class, when the class was over,

the instructor threw us a basketball, so we had fun playing ball.

Next day, one cf the upper classmen was there, and called for the

ball, and announced to everybody that there'd be no more ball

games until I left. And what do I do? And that was, I thought,

=

a case where Mitchell could have come up with something. If not

then, when?

Schneller: Was this a Southern-born person that --

Trivers: I don't have the slightest idea who it was. I

wouldn't recognize him. I was so bothered, because I was pleased

that the day before, we'd played basketball, and that didn't seem

11

fitting with all that I saw. And so the second day, I'm looking

forward to some more of it. I didn't have the slightest idea

about the cause of it. There were two of them in who came in at

the time. And when they took the ball, that did it. And Smoke

Park; I don't smoke, but Smoke Park has a sentimental attachment,

I guess. And I was in there milling around like everybody else,

and upperclassmen caught me and told me I didn't belong there,

and they escorted me to the exit.

Schneller: Was this a place that plebes were prohibited to

go, or did they just do this because you were black?

Trivers: It was the second one.

Schneller: OK.

Trivers: It looked like a sort of section of the grounds

where the fellows came to relax. It appeared that way to me.

You couldn't smoke in the dorm. I really don't know now that I

watched anybody smoking, but I remember it was Smoke Park,

because of the fact that cigarettes were allowed there.

Schneller: Among midshipmen I've spoken to who attended the

Naval Academy in the 1940s, there was a rumor, and this is how

they describe it, a rumor, that one of the black midshipmen who

had entered the Academy but not graduated during the 1930s was

found tied to a bell buoy in the Chesapeake Bay. Had you ever

heard anything like that?

Trivers: No. I heard of being extended out the window in a

very uncomfortable position, as if you were doing a crawl stroke.

I never saw it, but supposed this was a hazing that they

12

administered to some of the fellows. And this attachment to the

bell buoy, that's brand new to me. It gives you an idea of the

cruelty of some people. You don't need to be told, because more

recently than that, there was a girl chained to a urinal.

Schneller: Right. That's just within the past couple

years.

Trivers: That's dirty enough. And another thing. Not that

I'm a saint, but I'm saying it's something that's so far out of

order.

Schneller: Your son Ronald mentioned to me on the phone

that some of the other midshipmen used to spit on your plate.

Trivers: Yes. I can't say I became accustomed to the

Spitting, but--

Schneller: Did this happen every day, or several times a

Trivers: No, no. The mean things were isolated incidents.

I didn't hear "nigger" every day. I don't know whether those

around me avoided certain situations in using derogatory

language, or whether it just happened that; well, first of all, I

didn't know; they were all faces. And that's all. So I really

couldn't tell the plebes from the others, except what they wore.

Schneller: Right.

Trivers: And some were saying, when you were in formation,

and the officer--I don't know whether he'd be a junior officer or

who--but when the officer would come down to see if you've

Shaved, and other things. There were some who, without telling

13

you, seemed to have a touch that brought you together. Hard to

describe, but you probably know what I'm speaking about.

Schneller: Not exactly. A touch that brought you together?

You mean lining people up in formation?

Trivers: Ohno, no. Today at two o'clock we meet at so and

so''s place and we; we're in formation. And we have inspection,

roll call. And the officers--midshipmen in charge--would come

down and face each individual and criticize him for an unkempt

face, and that sort of thing.

Schneller: Oh, OK, yes.

Trivers: And I remember once I wondered about my own

shaving because I was growing whiskers very lightly then, but

another thing that bothered me was, I could see myself going out

the door, in that the demerits were piling up for an untidy room,

and you can surely find several untidy spots in any room. If

you're going to spend time with white gloves and get the room

totally tidy, you won't have time to do other things. So I felt

that that was unjust, also.

Schneller: Did anybody ever physically haze you?

Trivers: No.

Schneller: Was there ever any paddling?

Trivers: No. No one touched me. And that's one thing that

I wondered about too, because at Miner Teachers College, we had

two fraternal organizations, and they paddled you. And you had

heard of, or knew of, certain incidents of hazing, but I didn't

experience any of that. So I don't know what happened there.

14

Schneller: Yeah. Jimmy Carter, in his memoir, mentioned

that plebes were often hit with bread pans and spoons and paddled

frequently. I guess it depended on the individual--how

frequently he was paddled. Some of the people I spoke to

regarded paddling as a great big joke, both those who were

receiving it and those who were giving it. Another one that I

spoke to, who happens to be Jewish, refused to allow himself to

be paddled. And as a result of that, as a plebe, he was forced

to run the obstacle course a lot in the morning before formation,

but he would not submit to being paddled. . And as I said, others

made it into a great big joke. So I guess it depended on the

individual, how they reacted to it, but it did certainly exist.

Trivers: Yes. It seemed to have been a social event to

some. And I was pleased to be a part of the fraternal

organization at Miner, but I was disgusted with my buddies for

beating me so. I couldn't understand that. I believe they

changed my attitude from then on. Because the same fellows that

put their arm around you and are glad to see you, when they turn

th

(D

light out on Saturday night, and you're in the dark on some

farm, and you're paddled hard, there's something wrong somewhere.

Schneller: Yeah. It. doesn't seem to make sense. Did other

midshipmen, other plebes, talk to you, socially?

Trivers: I never had a word from anybody else there, except

the Commandant.

Schneller: Do you think there was a movement deliberately

to silence you?

15

Trivers: I had no reason to think plus or minus on that. I

guess we're all familiar, vicariously, with the silent treatment,

but other than the mean things that were done, I don't have

anything to show that what a certain person thought was pointed

in a certain direction. So to me, they were just faces. And I

guess some of those who walked by silently extended their hearts

to you, anyway. But--

Schneller: Is that something you were able to sense, or is

that something you just imagine happened?

Brown: Well, I know that I had read of a minister who had a

wife and kids. I'm not sure where he lived. But some racial

problem came up, and he took the broader side, and he lost all of

his friends, if they were friends to begin with.

Schneller: Everybody deserted him because he--

Trivers: Made friends with a person of color. You spoke

about the pleasure you had in this. And I imagine one of

pleasures has been meeting people who are intelligent and broad

in their thoughts.

Schneller: It's very refreshing. Also, it can be scary,

because two of the most intelligent people I ever met were young

black midshipmen. One of them was a freshman, you know, a

college kid, in his first year of college, right out of high

school. And I would go on at length, babbling about certain

things and he would say, "Oh, you mean," and then summarize what

I had just said in one sentence. And I'd say, "Yeah." And it's

kind of intimidating to meet someone so young that's; I mean, I

16

thought that he's probably more intelligent than I am, so it's,

you know; I try to be very careful not to say or do anything

that's foolish, but then I just be myself and I find that I get

by on it.

Trivers: Yes. We have to pinpoint some criteria to enable

us to say a person's more intelligent or less intelligent, or

whatever. And when John Jones is reiterating what you have said,

and doing it better, he may not be able to do some other things

that you can do. Maybe that's the only thing he can outdistance

you in. But when we get tied up, I think sometimes we do in

cases like that, to me, that thought that you had, doesn't

belong, because we have to go down and list attributes that are

better than his.

Schneller: Right.

Trivers: I wculdn't have any fear of that.

Schneller: Thanks.

Trivers: Yes. Did we finish with Paul Cooke and the

Commandant ?

Schneller: I don't know. You had mentioned that the

Commandant had, in a very neutral way, asked you to leave because

he said that there was no place for a black officer in the Navy,

and that you couldn't tell, behind that neutral facade, what he

real feelings about race were, but other than that you didn't

elaborate,

Trivers: Right. Yes. I had no sign of any kind. He was

courteous. And there was just nothing anywhere to point to his

17

feelings or mind either, I guess. It was just a quiet; I'1l say

business. But Paul Cooke was the alternate, and a very

intelligent fellow, but with meager background in science and

mathematics.

Schneller: Now he was in the group of eight?

Trivers: No, no, he wasn't.

Schneller: He came after you did?

Trivers: I believe he came later. And I don't even

remember why.

Schneller: I've got records back in my office indicating

that between the time you left and Wesley Brown entered, several

other African Americans received nominations to the Academy, but

none actually entered, because they didn't pass the physical

exams or meet the academic requirements. And in regard to these

physical exams, I found evidence, both in the Army and in the

Navy, that sometimes lies were told about the condition of the

health of a person. It was part of an effort to prevent African

Americans from moving up in ranks, or from becoming a cadet or a

midshipman. Wesley Brown, for example, had a one examination in

which the doctor pronounced him unfit for the Navy because the

doctor said that he had flat feet and a marked malocclusion. So

he had another examination. Flat feet didn't even come up again,

and the doctor that examined him the second time didn't find any

sufficient malocclusion to prevent him from entering. Brown told

me that he suspected some shenanigans on the part of the first

doctor. And I suspect that among some of the African Americans

18

who were considering the Naval Academy between the time you left

and the time Brown entered were subjected to the same sort of

shenanigans, but I don't have any clear evidence for that.

Trivers: Yes. Of course. But you'd expect it, too.

Because it can be very subtle.

Schneller: You lived in Washington, which at the time was a

segregated city. Did you have much contact with white people

before going to the Naval Academy. Did being in the presence of

all white people make you uncomfortable, even before the nonsense

started?

Trivers: Those are very good questions. I had no idea what

to expect at the Naval Academy. I had read about what had

happened in the South; individual incidents of cruelty. While I

was taking my physical exam before entering the Academy, an upper

classman asked me, "Are you afraid?" My answer to him was "No."

I personally believe that Miner Teachers College and Dunbar High

School, did a very good job of preparing us for what was to come.

I never had anybody white in any of my classes, nor had I played

with any whites as a youngster. I can't remember any.

Schneller: You didn't have white friends growing up or

anything like that?

Trivers: No, I didn't. Anacostia was over here--the poor

part of Washington, D.C. This land was given to the slaves when

they were set free. You probably remember reading some of that.

The hills were full of fertile soil and a variety of fruit, nuts,

and wildlife. It was an ideal place for somebody who loved

19

nature and outdoors. To go to the swimming hole, you went

through the woods, and you wore a straw hat and a minimum of

clothes. And you could eat blackberries all the way down to the

swimming hole and all the way back. And there was a huckleberry

farm you could pass through. Everybody picked huckleberries on

the way to the swimming hole. While there, you probably would

have finished them off. There was a store in the neighborhood

with a Chinese or Jewish owner. Schools were absolutely

segregated in every respect. I felt comfortable at the Naval

Academy because of the background that the. schools had built.

Our schools were old buildings and the faculties were stable. I

think that was the key to the success of so many of us who had

come through the segregated school system in Washington.

Schneller: It's my understanding that Dunbar had a very

high reputation for excellence in academics, and that people

would move to Washington just so that they could put their kids

inte Dunbar. Also, from what Wesley Brown told me, a lot of the

faculty had advanced degrees, and that's because a combination of

the Depression and segregation and prejudice meant that there

were few jobs available for black people, particularly those with

education. You couldn't expect a black person to get a job

teaching at a white college. So they'd end up teaching at places

like Dunbar, which meant that Dunbar was at least on par if not

better than the best white high schools in the country.

Trivers: That's very good. And when you came home from

your first day of school at Dunbar, and mother asked you to name

20

your teachers, she knew some of the names, because that's the way

it was. I went to Birney Elementary School, and four of the

teachers on the faculty lived within two or three blocks of

school. But as a result of segregation, we often didn't come

into contact with white persons. Our neighborhoods were

segregated. Our schools were segregated. We didn't have any new

school buildings. There was a white superintendent in charge of

all schools, then there was a white assistant superintendent in

charge of white schools, and a colored assistant superintendent

in charge of colored schools, and the structure was rigid, so you

didn't find the wrong person in the wrong place. But, as I said,

I just think that getting a good background--it built confidence

that we felt we could branch out and compete with whoever was in

class.

Schneller: So then you didn't feel intimidated at all being

the only black face in a sea of whites?

Trivers: No, I didn't, because I think it was due to

success in school.

Schneller: You were a good student? Used to make a lot of

"A"s and so forth?

Trivers: I did, and I was valedictorian of my elementary

school, eighth grade, and high school, and at Miner, except for

One point; I would have had cum laude, but not that it's

important.

Schneller: It all is, actually.

Trivers: [laughs] Yes, I guess so. And so, another

21

colored face wasn't disturbing, because you felt that you had had

whatever you needed. And I liked to study. I liked reading. I

liked to do my schoolwork. And I liked school.

Schneller: While you were at the Naval Academy, was there

anybody that might have given you a friendly glance, or tried to

show support, or was it pretty much adopting a distant attitude?

Trivers: Well, because of the nature of the day, there

weren't many opportunities to look your classmate in the eye.

The second year men took charge of everything, I believe it was

the second year; certain of them were on a. cruise.

Schneller: Upperclassmen.

Trivers: Upperclassmen. So it was the sophomores who took

charge of the plebes, I guess. And in giving commands, and

standing in a military fashion, you would look in a person's eyes

only at inspection time, or something like that. Other than

that, you're going about your business, and eye to eye contact

just didn't come to pass, it seemed to me.

Schneller: Yes.

Trivers: Even in examining your room. They come in and

examine the room and back out the door, with no comment. But you

know tomorrow that you got demerits and so forth.

Schneller: Meanwhile, I imagine you'd have to be standing

braced up at attention.

Trivers: Yes, yes.

Schneller: Looking straight ahead.

Trivers: True, true. And of course, the regulations were

22

very interesting, because "all turn out" in the morning was more

complex than it sounds, and "all turn in" at bedtime was equally

complex, more so than it sounds.

So I had never touched, or even spoken to, except ina

store, a white person. In the neighborhood, there was always a

Jewish merchant. And most of the time, Chinese for laundry. And

it was a monopoly. Nobody else. No competition. And so with

the Jewish merchant, he had the whole neighborhood. And we were

segregated, and put in circles, so it's geographical, and

geometrically, it's out of line, when he has the store that rules

in the circle, the diameter or radius.

Schneller: Certain territory, so to speak.

Trivers: That's true.

Schneller: Did you have occasion to travel into Virginia or

other places where there'd be white-only drinking fountains and

so forth? Did you encounter that on a daily basis before coming

to the Naval Academy, when you were growing up?

Trivers: Because I spent most of my time in our

neighborhoods, I don't know that I even saw those signs until

later. I know I saw them in Maryland.

Schneller: Did you find that to be disturbing or upsetting?

Trivers: Well, you finally get; I shouldn't say you get

accustomed to it. You finally get to the point of accepting it.

But not from the point of it being right or wrong, but--

Schneller: That's the way it is and therefore you have to

cope with it.

23

Trivers: Yes. And it used to anger me when somebody would

ask, "Why did you walk into that street?" Well, what happened

when Dr. King [Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.] had his group in

Washington from Alabama, it was a different time, different

location, different atmosphere, than what you'd meet in

Alexandria, Virginia, when five of your buddies would create a

disturbance which would help with integration. So there are

factors that surround each incident that would make a difference.

When I was at Miner, Garfinkles would allow you to work only in a

menial fashion, but your dollars were always important. And at

Hechts or Landsburys you could help clean up. But if you got a

job as a clerk, you'd wait on the person, and once they decided

what they wanted, you would carry the commodity to the cash

regist

Dp

xr, and a white person would ring it up. And of course,

there were no milkmen of color, or bus drivers, or meter readers.

They were all white. And you couldn't ride in or drive a Yellow

cab or a Diamond cab. I admit I can't tell exactly when those

things disappeared. But I know we did a lot of picketing outside

of the drug stores.

Schneller: This was back in the thirties, before going to

the Academy that you did picketing, or did this come later?

Trivers: Before going to the Academy.

Schneller: OK.

Trivers: There were places in drug stores or five and tens

where, as you shopped, you could go to the soda fountains and get

a het dog and a soda, but you couldn't sit there and eat. You

24

had to walk around the store with your hot dog and soda in your

hands.

Schneller: There was no accommodation for seating?

Trivers: Well, I never saw a white only sign, but it was

understood. And strange. I guess it was strange.

Schneller: From my perspective it seems very strange.

Trivers: Yes. And you could stand at the end of the

counter and eat all you wanted, but not in the seats. But you

could spend your money. |

Schneller: Did you have a job when you were in high school?

Trivers: I always worked. When I was attending Dunbar High

School, on certain days in the summer, I hiked with a group of

neighbors to a farm that paid us to pick string beans. The farm

was along the banks of the Anacostia River, near Blue Plains,

south of the present site of Bolling Air Force Base. We left

in the black of early morning. I was surprised at how long it

took m� to pick

00)

bushel of string beans--almost all day. My

neighbors--ladies from North Carolina--could pick a barrel. I

was the only Washingtonian so employed. While attending Dunbar

High School and Miner Teachers College I delivered the Baltimore

Afro-American. The newspapers were trucked directly from

Baltimore on each Thursday night, arriving between 11:00 and

11:30 p.m. I found it necessary to stay up at that time. I

studied until my papers arrived, then left home about midnight.

I had approximately 200 newspapers to deliver. They were too

heavy to do all at once, so I delivered them in thirds. It took

25

all night. I returned back home at or about 6:00 a.m., having

just enough time for me to prepare for 8:00 a.m. class. I

delivered the Afro-American until my third year at Miner Teachers

College. After graduating from Dunbar High School and as a

freshman at Miner, I was employed in the registrar's office,

which provided a timely helping hand, financially. At Christmas-

time during those years, you could apply for helping with mail

delivery at the main post office. After entering Miner Teachers

College I served as an elevator operator. Running the elevator,

you made a dollar a day. A dollar a day meant every day--

Christmas, New Years, other holidays, special events. If you

worked late, you still got a dollar. When the last of the month

came and you got your pay for 31 days, you had 31 dollars. It

was small, but it was big then.

Schneller: Were you in the Cadet Corps at Dunbar?

Trivers: Yes.

Schneller: Wesley Brown told me that during World War II,

everybody entered the Cadet Corps because the war was on and they

felt a certain patriotic duty towards doing that. That extended

into the postwar years. Was that common to be in the Cadet Corps

in your time, when you were at Dunbar? Why would you have gone

into the Cadet Corps?

Trivers: Well, I don't know. You were expected to join the

Cadet Corps. I don't know what happened if you didn't join. I

never saw that side of it.

Schneller: So pretty much every male at Dunbar was in the

26

Cadet Corps?

Trivers: Yes. I feel that if he had some ailment, that a

note to the military office would suffice in excusing him, but I

felt that every male participated in drill. Of course I came out

of Dunbar in '33, and all I knew then was drill. I don't know

what the reasons were, except that when you enter, you're

expected to drill, and I don't know how you get around it. But I

guess some did.

Schneller: It wasn't something that you had even

questioned, though?

Trivers: No. Everybody was drilling. At my time at

Dunbar, there was also Armstrong, which was right around the

corner from Dunbar.

Schneller: And Cardozo also?

Trivers: Cardozo was born when I was; Cardozo was the

youngest, or was one of the youngest, high schools. They saw a

need for business, and thus, Cardozo was born, and I have a hard

time remembering the exact time.

Schneller: What do you remember about Colonel Atwood? Can

you describe his personality as best you can recollect?

Trivers: I can't say a thing about him, except that he was

involved in the gathering of the fellows that were to be

sponsored by Congressman Mitchell. On my first day at the

Academy, Colonel Atwood suddenly appeared with the $100.00 I was

to deposit. I knew nothing of the required payment before

Colonel Atwood's appearance. I caught a glimpse of him after the

27

swearing in ceremony, but didn't speak to him. I never heard

from him after he delivered the deposit. But at Dunbar, I had

known him as youngsters knew other senior citizens. I knew him

as a military man, and I don't remember anything about him.

Schneller: Nothing about his reputation or his being a fine

citizen or--

Trivers: No. During those days, it was easy to be a good

citizen. The board of education was. apparently doing what they

should have done. Despite segregated schools, the school system

was run very well, and it produced--

Schneller: Might you say that the school system, in

general, produced an attitude in which being a good citizen is

what people strove for?

Trivers: That's very, very good. Because the cruelty;

strange things that are happening now to families, or parents,

offspring, and so forth, weren't even heard of back in those

days. Segregation probably was the worst thing that happened to

us, and yet there may have been benefits in some cases. I don't

know. I'm not even sure how smart it is to say that, because

segregation seemed so wasteful.

Schneller: I think that's a very good way of putting it.

Wasteful.

Trivers: And it seemed to get nowhere. I think you alluded

to the fact that our racial problems will be solved down the

line.

Schneller: I remain hopeful. From what I've studied, it

28

seems to have gotten better. There's still a way to go, though.

Trivers: Right. The thing that scares me is that, while

things are progressing, skinheads, young nazis, fascists--

Schneller: Holocaust deniers particularly mystify me.

Trivers: Yes, yes. Arguing about it all being a farce.

Yes. So we have to keep on trying. But it does baffle. We seem

to like to hate somebody. We mistreat little animals, our pets,

our families, and so forth.

Schneller: Do you remember any other sorts of efforts that

other midshipmen while you were at the Academy made to make you

feel uncomfortable? You mentioned that people would not talk to

you socially, and that you were spat on, and so forth; do you

remember any other kinds of things that people did--name calling

and so forth?

Trivers: Name calling. "Nigger." That's such a commonly

used term. You expect it, I guess. Because it was just a

commonly used degrading term. But "nigger" and being spat on.

[interruption]

Schneller: The article in Time magazine [Time, vol. 30, 19

July 1937, p. 15] mentions that while you were at the Naval

Academy, during drill, other midshipmen stepped on your toes, and

at night, pounded on the walls of your room to prevent you Erom

Sleeping. Do you remember these things? How often did they

happen?

Trivers: No, I don't remember pounding on the wall. I just

remember that I was by myself, and I was very conscious of

29