[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Note on the Cover

This yearTs cover is by Lisa Bateman. ~~Porkalina-Ode

to Katherine? is one in a series of five paintings dealing

with commercialism in a whimsical context. Lisa says,

~~Porkalina itself is dedicated to the type of person that

smokes and eats at the same time.?T

LisaTs piece placed 2nd in painting. She has shown

work in ECUTs Student Show and she also has a piece

in a traveling show of ECU student work.

Vol. 22 Number 1

COLLEEN PLYNN

SUE AYDELETTE

Associate Editor

Proofreader

The Rebel! is published annually by the Media Board of East

Carolina University. Offices are located in the Publications

Center on the ECU campus. 7he Rebe/ welcomes manu-

scripts and inquiries; however, unsolicited manuscripts unac-

companied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope will not

be returned. Address all correspondence to 7he Rebel, Men-

denhall Student Center, East Carolina University, Greenville,

NC 27834. This issue is copyrighted (c) 1980 by The Rebel.

All rights revert on publication to the individual artists and

authors, from whom permission must be obtained to

reproduce any of the materials contained in this issue.

Anheuser-Busch Poetry Award

June Sylvester

oThe CallingTT

Jeffreys Beer and Wine Prose Award

Joe Underwood

~ooStrawbossTT

Fourth Annual Attic Award

Stephen Edgerton

oHarriet McNeill McKay

The MatriarchTT

All Prize Money Provided

By The Attic and

Budweiser

ATTIC

The Rebel has been in high

standing for many years. As this

yearTs editor, it is my prayerful

hope that with the changes made

in this issue, the high standing

still remains.

| once asked Luke Whisnant,

last yearTs editor why we didnTt

have two issues of 7he Rebe/

each year and believe me, | now

know why we don't.

Putting this magazine together

has been hard work and quite a

learning experience. To have the

Opportunity to be directly in-

volved with so many student

writers and artists has been very

rewarding. | would like to thank

all those who had so much

patience with the art show,

newspaper announcements and

the like.

Two English professors whose

influence on the writing students

at ECU has been great and to

whom | wish to dedicate this

issue Of The Rebe/ are Terry

Davis and Peter Makuck. | wish

to extend my utmost thanks to

these two men who have made

such things as writing novels and

good poetry seem readily ob-

tainable to those who work hard.

Their interest in writing and con-

cern for students is very ap-

parent.

| wish to thank the staff for

working long, hard hours even

when the monetary value given

to their efforts has been so little.

Special thanks are also extended

to Robert Jones and Pete

Podeszwa_ for their helpful

suggestions. Tom Haines, Edith

Walker, and George Brett for

judging the art show. David San-

ders for judging the literature,

The Media Board, SFA office,

contributors and most of. all

thanks to the kind people at

National Printing.

CONTENTS

LITERATURE

Classroom Activities .

Untitled

Collard Centipede ...

Route 1 Appliance

Saga

Marco Polo and Other

Water Games

Untitled

Vernon

Dream Salvages

Drowning, With

Relatives

Seymour: An

Epilogue

Southern Comfort...

The Calling

| Will Not Weep

Tagged Last

Oedipus

Untitled

Shoplifter

As | Listen the Air is

Split into Layers...

Uneasy Transition...

Crossing the Linville. .

Novena

Passage

Strawboss

Fossils

What to Know About

The Fish Kill

Like This

Dangling

Survivors

Ocracoke

Lineage

Untitled

Untitled

Paradox

Teller II

A Matter of Existing

Will (in fragments) .

Plum Stone

Tim Wright

Hal Daniel

Michael Loderstedt.

Colleen Flynn

Michael Loderstedt.

Sue Aydelette ....

Karen Blansfield...

Robert Jones

Kathy Crisp

Karen Blansfield...

Sam Silva

June Sylvester....

Sam Silva

Sue Aydelette ....

Joseph Dudasik ...

Cheryl Ribino

Luke Whisnant....

Luke Whisnant....

Phillip Arrington...

Luke Whisnant... .

Robert Jones

Tim Wright

Sam Silva

June Sylvester....

Joe Underwood...

June Sylvester....

Luke Whisnant....

Tim Wright

>. Phillip Miles...

Jeffrey Joseph....

Denise Andrews...

Tim Wright

June Sylvester....

Michael Loderstedt.

Michael Loderstedt.

Ernest Marshall... .

Phillip Arrington...

Robert Jones

Sue Aydelette ....

Kempten L. Daniel .

ART

Dudobrats

Gas Mask

Southern Rail

Gallery

Seated Figure, Red ..

Seated Figure

Spectral Encounter . .

Target Treeptych....

Weather or Not

After the Sincerity...

oHarriet McNeill

McKay "

The Matriarch? ...

Phoenix

Girl With Hat & Vest .

114 E. 12th St

The Original Juvenile

Juxtaposition

_ The Blackbird Whirled

in the Autumn

Illustration

Illustration

Fish Kill

David Larson

Ed Midgett

Sid Davis

Rita Earley

Robert Daniel

Robert Daniel

Betsy Kurzinger ...

Betsy Kurzinger ..

Mark Peterson ....

Roxanne Reep....

Stephen Edgerton .

Michael Loderstedt.

Larry Shreve

Michael Loderstedt.

Ella Mallenbaum.. .

Pete Podeszwa....

Marcia Deckey....

David Norris

Judson Poole

Pete Podeszwa....

Brenda Williams...

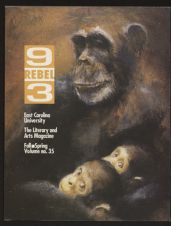

REBEL

The Literary-Art Magazine

(o} i =t- |) OF- 1 c0) [lat MOlaliY-1s118%4

4

Classroom Activities

I offer to sew.

She threatens to accept.

I read Al Dugan

to her new cat.

She disapproves.

She thinks I give her

more than she asks for.

Her cat composes beautiful

sonnets. She is tired

of knowing it rains on Tuesdays.

Her cat becomes

a villanelle, she is

angry with me, sheTs always

losing cats this way.

Tim Wright

what is wrong

with an orange peel

on the sidewalk

at 6 pm

the day after xmas.

Bob Ray

COLLARD CENTIPEDE

Trying to get this one into words is like trying to describe

the taste of chocolate, but I just saw a dew-laden strand of

emerald green collards sprout combat boots. The boots

turned groundward, tested themselves with a few good

stomps, and then proceeded to carry the entire row of col-

lards, like one huge marching green centipede right out of

the furrow and down the white line of the highway. The

collard centipede completed a oleft flank march? and strad-

dled the highway line in perfect symmetry and time, until it

was but a dot on the horizon and, then, out of sight forever.

Iwas smiling as I got out of bed to start the day of January

10, 1980.

Hal Daniel

Route 1 Appliance Saga

on top of the

refrigerator

where an onion bag

skin-filled

and loathsome

remained very content

life was easy

but short

and soon changed.

new neighbors

Impish rogues

the raisin bran clan

bickering endlessly

In their cardboard

condo

they were labeled

a cereal mismarriage.

many died in great

floods

while other envious

flakes

ran away to become

bread brothers

wrapped tight

bonded to secrets and

loaf oathes.

soon the bread grew

restless and green

mold.

and many left

their plateau estate

In pairs

each after a chance

a slice

or a toasty vacation.

Michael Loderstedt

fl

Marco Polo and Other Water Games

The bathing cap

My friendTs mother made me (at twelve) wear in the country club pool

Had rubber flowers on its sides

Big blue and pink pansy-shaped flowers

Like those on our colored maid's flip-flops.

I'd jack knife into the pool, pray my cap

Would come off, pull if it didnTt, then

Butterfly stroke a length and back.

The cap would be floating along the poolTs edge

Like a blooming lily.

Older women in pointed-boobed suits of broad flowery print

Had caps like mine.

They'd side stroke and back stroke and rest on

The side doing swift leg flutters.

A broad backed swimmer in a racing style cap yells

MARCO

| say POLO then lower

Myself, bubble-headed

And begone.

Colleen Flynn

she is napalm

poison gas around me

she watches my leaves shrivel,

fall. a

we pass in the doorway.

my eyes fixed

on a point not bending

near her.

she is bittersweet

Coyemeohiannevercattome)

-astale refrigerator,

empty. no food.

she reaches for new stems

too short to pick

the telephone rings

she pouts.

sometimes she is nice.

like now. eyes watch

- await the transition. sniffing

the gas.

Michael Loderstedt

SS

10

VERNON

by Sue Aydelette

Vernon would meet me in the carport on his

bike. We raced there, taking tight fast curves

around the carport posts. Or we looped them

slowly, finally stopping, straddling the bikes

and talking. It was cool and dim below the car-

port roof but open so that hot sunlight sur-

rounded us. It smelled good in that shade, like

ear oil.

Before I got the letter, I had forgotten Ver-

non and Mark. Now I hear that Mark is working

in this city too and I suddenly notice that this

big office is like that place, Norstad Street

where we knew each other. Vernon lived across

the street. Mark lived on the end of the same

building I lived in, Air Force Base houses, all in

one piece, all identical. We never thought of it

then, maybe because we were children, but

here, where the desks are all the same and in

rows, green blotters and heavy adding

machines on each, people mark things. They put

up Bible quotes or newspaper cartoons, they

have color animal stickers, some of them or

plastic flowers or immense rubber plants that

threaten the order of their work by throwing a

grey leafy shade across the columns of num-

bers. And these people mumble softly with the

hum of office machines and break sometimes in-

to loud laughter. They are in the ladies room,

franticly close to the mirror and in the halls

swinging their arms like children. So far, I keep

my desk clear of all but the white gridded

paper, the long yellow pencils and the old ad-

ding machine. I wonder if Mark has a desk, ina

row of similar desks somewhere in this city.

Mark was ten when I knew him on Norstad

Street; I was seven then and when I first met

Vernon he was six. Vernon was small; a clean

blond boy. His mother was German. He had a

pink bathing suit she made him wear. He never

crossed the street in it but my mother saw him

over in his yard. The suit, she said, had straps

like one of my girlTs suits but they came down

almost to his waist so they were really more like

suspenders. But it was pink. I never talked with

him about it.

Mark was much bigger than us both, and

smart, and had a broken leg. While I knew him

he went from a cast to a brace and back to a

cast. I donTt remember ever talking about that

either, but we did talk, the three of us. Since he

couldnTt run around, Mark would drag an old

straight back chair out into the field between

our building and the road. It wasnTt such a big

field, but in the center of it we had a lot of space.

And it was a field with flowers, milky dan-

delions, those small daisies and tiny round

yellow flowers you never saw until you sat

down in the thin grass. Mark sat out there

every day in the summer. Vernon and I would

wander over sit down and we'd talk; sometimes

about the cars going by or the way mushrooms

spread out in circles. Sometimes we had things,

like a chalk board, and Mark would write out

names for us: C-o-l-u-mbus, or make up codes.

Or the etch-a-sketch and Mark would turn out a

black scribble for Vernon and me to find the

beginning of. Once I found a box of gold tipped

matches. Vernon and I took the box over to

Mark. Sitting huddled, we took turns lighting

them until each match had flared up and burned

down to the finger and thumb that held it " un-

til all the matches were burnt ends, black splin-

ters that we buried in one small hole. I kept the

little sliding box, glad that Mark and Vernon

lost interest in it once it was empty.

My mother keeps up with MarkTs family.

Being good friends with Mrs. Ledbetter, she

had known all about MarkTs leg. I listened to

those details once, but I only remember that it

was something simple " like falling as he got on

the school bus " which broke MarkTs leg so

badly. Mama writes now to just mention that he

has a job in the city. Mark moved away six

months before Vernon died. A lot happened af-

ter he left. It was then that Vernon would meet

me in the carport leaving the bright field off to

the side of our houses empty.

Mark would remember much, though, and un-

derstand more. He would remember the naps;

how Vernon and I each had to go home, eat

lunch and rest. Mark never had to take naps of

course and when I ran back outside, sometimes

Vernon would be coming from across the street.

We'd race to where Mark sat, crash into him,

and knock his chair sideways into the grass. It

was the naps that started the discoveries

though, after Mark moved away. They were

proofs, both of them, proofs of natural science.

During the summer after Mark left we did

not go, usually, into the field. One day though,

after our naps, Vernon was waiting there for

me. Before I sat down next to him he asked,

~oW hatTs an axis like??

~An axis? You mean for wheels on cars? You

know what that is.? Vernon was seven by then

and he never was stupid.

oYes, but whatTs a world-axis like? You know

" with the world turning on it " is it just a

giant bar in space?

oYes,? I said, I always acted like I knew after

Mark left.

oYou ever hear it?? Vernon turned to ask it,

facing me in the center of the field.

oHear what??

oThe world turning,? he said it slow and then

in exasperation, oDo you really sleep after

lunch?

oOf course not.? I was thinking of lying on my

motherTs big bed, feeling hot, and yes .., the

roar, I heard it every day.

oVernon, you sure you didnTt read this some

place? You sure Columbus didnTt hear it?? Ver-

non was mad. I knew he had to read books in

school about children and dogs. Anything in-

teresting he had to make up himself. Nobody

told either of us anything good except Mark and

if Mark had told it, I would know.

~Vernon, you sure Mark didnTt tell you this??

When I said that Vernon ran off. I didnTt chase

him.

It was after my nap the next day that I ran

over to Vernon and he was running to meet me.

Panting into the carport, we squatted in the

cool grease smell. oVernon, you're right! I heard

it! I hear it every day " after lunch, that must

be when it turns!

~DonTt tell anybody, Reenie.?

That was the first discovery. The second one

I made, with Vernon there next to me. We were

lying on the hill behind my house, on our backs

but with our feet going up, feeling the blood

rush to our faces. Our arms crossed under our

heads. In short sleeves I remember, feeling

sharp tufts of grass against my arms. We

weren't talking. And then I noticed that I was

moving. No the clouds were moving. I wasnTt

sure. And that was the second discovery.

oVernon, are you moving!

oWhat?? His eyes were squeezed tight a-

gainst the light.

~Vernon, please open your eyes.? I acted

calm. oLook, Vernon, are the clouds moving or

are we??

He jumped straight up to his feet. He looked

big like that from where I was lying. He jumped

up and then he lay right back down and watched

and we had our second natural proof for the

rotation of the earth.

At lunch I couldnTt contain it. I just hinted

and my older sister, still chewing, said of course

clouds move. I felt sick and awful.

During my nap I lay down and listened with

my eyes closed to the world turning on its axis,

a sound so big that it was quiet. I stayed there

longer than usual. I didnTt call down once to say

" is my nap over yet? I lay there until my

mother came upstairs with a pile of my fatherTs

shirts smelling like hot, ironed cotten. Then I

went outside.

Vernon was on his bike in the sun, riding a-

round the sidewalk square across from the emp-

ty field. There was an old coffee can at one cor-

ner and each time Vernon came around the

square he rode over it, jumping his bike up into

the air. Other children watched him. I joined

the little group and he saw me, but he put all his

concentration into going over that can. I

thought it was stupid " him grinning and

squinting like it was important. As he hit the

can. Then his front tire turned and in mid air

the bike jerked out of VernonTs hands. He was

in the sky, and then down on the ground so fast

and then just lying there. He was pale and

small, his eyes closed, his hair almost white in

the sun. I could see that one of his arms was

twisted backwards and I ran for my mother.

The other children backed away and watched as

Mama brought a pillow, a blanket, and then ran

back to call a doctor. Somebody finally went

over and told VernonTs German mother so that

she came running out just as the ambulance

screamed into the carport. Vernon, unconscious

all that time, was put on a big stretcher and a

white sheet was tucked up to his white neck.

They carried him into the shade of the carport

as if he were no weight at all. When the am-

bulance left, Mama and I were alone and for a

long time, silent in the shadow.

~oWhatTs that noise, Mama??

oWhat noise, Reenie? The airplane??

And then I knew it was there, not just at

noon, but all the time, that noise from the run-

ways across the base. So before Vernon was

dead I knew there were no discoveries at all.

But Vernon never knew. He died that night.

Mark will be glad it happened that way. Vernon

died better than Columbus, who got old and

crazy. And better than me. Already I walk

down the halls at this job trying not to swing

my arms too much. Vernon would have hated it.

11

V2

Elegy

They have hewn the huge oak

that guarded my grandmotherTs grave,

LOL Out

the twisted gnarled limbs

that lent reverence to the sky

as her gnarled fingers

lent reverence to all they touched:

the rosary she beaded silently,

the arm she grasped

with fragile hand,

the twisted Irish walking cane

held limply in her lap

as she stared vacantly

into somewhere.

Once, in winter,

I stood beneath the black boughs,

fusing their form into words.

But the words were lost

before they were written.

And though I returned

in summer

and again in winter

to search,

they were found.

Now

I cannot find

my grandmotherTs grave.

Where once the dark mass

spread its aged web,

unmistakable cairn,

there is now anonymous sky.

For they have felled the ancient oak.

It was too old

to go on.

Karen Blansfield

DREAM SALVAGES

by Robert Jones

September 29, 1967. I was eleven years old

and had not seen my father since July. He was

sick with heart trouble, in the hospital with that

queer antiseptic air. HeTd had heart trouble and

had been in the hospital before, and ITd visited

him many times, but that day they wouldn't let

me see him. I went to bed, fell asleep, and began

to dream.

I dreamed it was Ash Wednesday, the

Catholic, holy day that initiates the Lenten

season " a time of preparing oneself for the ob-

servance of ChristTs passion. I stood in the cen-

ter aisle of a church, in front of the altar. All I

could see around me were tall lighted candles. I

stood there alone for what seemed like many

slow, burning hours staring at the flames to see

if I could find any blue in them. Then, a priest in

black vestments came toward me. He stopped

and asked me if I had any special prayer to say,

and I nodded that I did. I knelt quickly and

prayed, oGod, please let my daddy die. Let him

rest, let him not be in pain.? When I stood the

priest made the sign of the cross with ashes on

my forehead and said, ~Thou art dust and unto

dust thou shalt return.? I knew those ashes

were the ashes of my father.

The telephone rang waking me immediately.

Something was wrong, and I heard myself say,

oPlease God donTt let my father die today, not

today.? I sat in bed watching my older brother

and my mother walk swiftly down the hail

towards the phone. My mother answered it on

the third ring. I didnTt hear what was said, but I

knew what had happened. So I lay back in bed,

pulled the covers over my head, and let the

sound of my heart beat me back to sleep.

I dreamed again. My father was laying in a

narrow hospital bed. His head, chest, and arms

were attached to many tubes and wires that

stuck out from under the edge of an oxygen tent

and connected him to machines around the bed.

It was dark in the room except for the little red

and green lights on the instrument panels of

machine which clicked and gurgled. It was so

alien and scary, but I told myself from then on, I

would never be afraid of anything. Only when I

got right next to the bed, I realized I could see

my father plainly, as if a flourescent light was

somewhere inside the oxygen tent. His face

looked calm, but for a slight wrinkle in his

forehead. His blue eyes were closed. His face

was flushed, and his mouth was partly open "

no trace of a smile. I watched him sleep wanting

to tell him something, but I couldn't get the

words out. I could only gurgle and click like the

machines I watched his breath turn to vapor in-

side the tent. Slowly, the vapor filled the tent,

then the room: it got heavy like a cloud " a

spongy cloud that moved over my father and

gradually absorbed him until he was gone.

When I woke again the blanket and sheet

covered my face. I remembered my dream. I

knew how my father left this world. In his sleep,

in a cloud. I glanced at my bedroom clock and

saw it was 10:30. I got out of bed to eat break-

fast. There were two neighbor women in the

kitchen. One was feeding my baby sister who

was almost 2 years old. One of the women star-

ted to tell me my mother and brother had gone

to the hospital to see my father. I shook my

head and said, ~o~No, my father is dead. He died

in his sleep last night.? The women stared at

each other, and then at me. They knew,

assuredly, no person told me.

I do not recall much more of my fatherTs death

day, except I tried to tell my best friend, Ar-

mand, my father had died, but he was not at

home. So, I walked in my backyard thinking I

had the same disease as my father and would

die young too. I walked and told the pine and

willow trees to be strong, and the birds to sing

and dance under the bleached blue shroud that

was the sky.

Ss

14

Drowning, With Relatives

After a photo in the Washington Daily News

The drowning is complete.

The old black woman dressed in white

Is being guided back from the pier,

Her open hand beating her heart.

Other faces, awash with night

Hover around her like wings

As she is silenced in a flash,

Her mouth a black hollow.

The water keeps slapping the shore.

Kathy Crisp

seymour: an epilogue

you did not

walk into the sea

on that perfect day.

the day broke

over you,

a small black mass

of fur

shrouded in frost

as wave after wave

of mechanical fish

crested past you

on the black strip

of land.

Karen Blansfield

RS

16

SOUTHERN COMPORT

My palet breathes tincture of burgundy

I could drown in it

Like what changes the puddle red to green

For this is the South

Where factories grow from green hills

Where gulls fly inland

From rubber and oil inhale

The marigold

Not just wine this thing

My thing

But wine of the heart

Makes the rude smooth

Not one crack to cut my tires

Maple fires red orange

Bring the sun to earth sometimes

Why I saw roses bloom in January

One reddish winter

I remember it | ate peppers with Sylvia

Out on the veranda

Night is coming

The cars have bred

With oil shafts and rude openings

I suppose

At any rate more of them

In wild herds

With headlights glued to towns

And chasing off malingerers with words

Profane demands no hint of supplication

This night is black as good farm soil

It must lie in fallow stupor

lest it spoil

The origins of evenings

Of the planets first half motion

Lie with Sylvia, my wife

Now dead and dying even more

Each time I realize I reach the final

Element: the empty drive the pitched house

The cellar door

Sam Silva

SS

-

Ss

The Calling

I have learned to recognize the warm

Vaguely oniony scent of my motherTs hands

The essence of her calling

At twelve I was going to be an artist

I drew my mother bent over the oven

With sweat damp hair clinging to her neck

On Sundays I sat stiff on hard benches

I listened to the stories. Mary sat

At JesusT feet, but Martha was busy in her kitchen

I wander out in the evening

Mother calls to me from the kitchen window

Her face is framed, crossed, and hung through the panes

The years make Mother smaller

She looks at me and shakes her head

Says, oHoney, settle down ... good

man... Chrustian family.

My lovers say ITm distant

Or insecure, or hopeless

Inod my head, I watch their jawlines move

(see how hard they swallow)

Sometimes I raise my music up

I send my voice out

I split my own silence with song

Mother says, oHoney, turn that down a little

Your fatherTs sleeping...

You can help with supper if you will . . .?

I will I will (not my will but thine)

Mother says ITm headed down

The wrong path

She shakes her head

While the stove that heats MotherTs heaven

Consumes

And consumes.

June Sylvester

I Will Not Weep

The bails of garden mulch

Are sequined in earth borders

Between welts of flowers

There is a dead tower

In the distance

Where we played as children,

Death dare games

Hurdling multi-leveled rafters

To thin lumps of hay "

Now even this decays

Nothing

Nothing in the world

Would roar so loud at lightning

Promising paradise

Though at sixteen we returned

Drawn to glimpse the spread of alfalfa

And seeing now

At twenty-five the virile vine

The projects of youth gone

We mouth our words separately

And silently

To think we could have leapt up to the heavens

Inflate balloons with stardust

A multitude of perfect childish

nonsense

A language so complete

So different

I will not weep

But only look away.

Sam Silva

19

Tagged Last

Tagged last by my fatherTs voice,

every dayTs game was called over at dusk.

His white t-shirt floated just outside the doorway light

until I turned toward him bargaining for one more game.

He was gone

behind the slap of our screen door. I followed.

From bed, I heard children

laughing.

Dark air ran across my pale sheets

and my fatherTs silence rose up the stairs

pressing on my dreams.

I have seen it now.

Night is a dark pine made white,

using up a moon a month "

turning it

from a shy sliver toa wreathed and rounding siren

until suddenly

night lifts up a moon flat and pocked.

Still, it is some sound

of night I chase.

Pressed on by the shape of my old dreams

into the whir of cicadae, the hum of neon.

Pressed through the erratic jargon of night

to morning

Where from his bed,

my father hears my poem.

Sue Aydelette

Oedipus

At some time

the sound has to stop.

Blindness can only be so dark,

and tongues can spit

only so much cork from each swallow.

Even the scald of desert rivers

can be eased over;

and the stench of wet leather

forgotten after a month of floodings.

But the sound has to stop.

The ledge of the cliff

startles the quiet; it is not seen;

the wind is not felt;

but that groan of depth

makes the quiver that is in my knees.

The words are remembered,

and the dance of the goatsong,

and the cracking of the bottles

is what overwhelms.

The temple finch startles the air.

Hearts shake the columbine,

and hands cast bottles into the ravine.

But the sound has to stop.

It gurgles in the blood,

whispers in the head

and applauds with both hands

across the face.

It has to stop.

J oseph Dudasik

oe

Beneath the faded

shirt on the line, cherry

petals in shadows

When a branch strays

across the sun, leaves and moths

become one color

The pitcher rests on

the tree roots, last nightTs rain

within and without

As the rabbit browses

a leaf momentarily

fills his ear

Cheryl Ribino

MICA

Brittle. Thin slips

line the trail.

Some catches sun

onicely;TT worthless,too dull to see

yourself, kick it

into the creek,

fling it down the slope,

step on it. The common

kind: your pack is

TU OF It,

You want black mica.

Looks old, stained-glass

swirls, gold flecks.

Fight through laurel,

switchbacks, watch

for snakes. When

it crops up " boulder-sized

beside the trail, too huge

to carry out " what can

you do? Pick up chips.

You know you cannot

break a piece off.

Luke Whisnant

Duplex

His wife sings in the backyard hanging clothes

a faded blue shirt knotted under her breasts

his socks swing in the wind

sometimes we talk about our landlord or the weather

sometimes she asks me if |am lonely

| never answer

| live alone listening for their windchimes

their throbbing stereo her moans

his deep voice on the phone

he works downtown in an office far above the street

soon they will buy a car move to the country

leave me

me late-sleeper, day-waster

waiting for dusk talking to the radio

leave me

each evening | hear his thin wife in bed

each morning | shave while her husband is shaving

we stare at back-to-back mirrors

listening standing so close

his face almost coming through | stop breathing

he unplugs his razor

then the bedroom tangled blue sheets

his wifeTs bare shoulders she kisses him good morning

| start another day

Luke Whisnant

23

SHOPLIFTER

How can he look so much like water

In such tight clothing, and survive, in that way

sO awry, skewered on a laserTs hiss

lancing his jacket and touching,

with bright alarm, the make-up mirror,

the silver-plated comb & brush set,

and the instruction manual on

oHow To Play Bridge: Ten Steps to Mastery.?

Even locked to the stiff arm

of the officerTs early detection techniques,

aware of how much he will lose

to the prima facie of guilt "

how the mirror must have mimed

all the faces he would pull in walking out,

or how the comb had given his hair a brutal part

and the manual heTd only thumbed through

had printed the dummyTs fate deep within its appendices. . .

So that even with such witnesses as these,

he would borrow your lighter

and be flung into the squad car,

hoping you could forgive the awful memory of thieves.

Phillip Arrington

24

Robert Daniel

Robert Daniel

Betsy Kurzinger

| Betsy Kurzinger

28

Mark Peterson

30

Roxanne Reep

Stephen Edgerton

scans ates

a1

Michael Loderstedt

Oz

_s

Larry Shreve

Michael Loderstedt

3a

David Larson

Stephen Williams

34

Ella Mallenbaum

55

As I Listen the Air is Split into Layers |

by Luke Whisnant

Sheets SS :

They are deep blue, as blue as the sky looking

straight up, blue as Dutch China, blue as your

eyes when you wake. In the top sheet, on the

left-hand corner over the seam there is a half-

circle of tiny holes: a gift you left me on the first

night we slept together: teethmarks from when

you stuffed the sheet into your mouth so the

people in the next room wouldn't hear us. Every

time I look at these sheets now I think of that

night, of how cold it was and how you had

_ gooseflesh everywhere I touched you. And later

we slept curled, with my hand on your breast,

and weTve never slept any other way since.

The sheets were brand-new and clean then,

but now theyTre a little worn, slick ahd soft with

use, and on the pillowcase I can smell where

your hair lay this morning and all last night. ©

I'd like to get up. ITve been in bed for days

now, it seems like, trying to get my balance

back. My ears are ringing. ITll admit it: ma lit-

tle light-headed. Sometimes I catch myself

kissing your teethmarks in the blue sheet.

Window

Coming through the finger-smudged window

are three sunbeams, sharp-edged, blinding

shafts I watch moving against the wall.

_ Splotched, etched, three sun-shapes on the

es ce ee eae

ONE AE

floor, two of them rhomboids, light-losenges,

and the third smaller, tapered by the curtainTs

shadow. Dust notes turn and spin slowly in the

solid columns of light; dust drifts in whorls from

window to floor and as I watch, I think of how,

when I was younger, I used to try singling out

one white speck and following it down. I try it

now; I pick a bright pinpoint and watch it glide

floorward, slow and then faster, scribing half-

circles, side-slipping and the rising on an up-

draft like a tiny white gull banking and gliding

in the sun. When I lose it I pick another one. ItTs

too much: my head, spinning and swirling

already, starts to whistle a shrill song to me,

and then from a long way off I can feel myself

dropping back down to the pillow in slow

motion.

But when my head clears, I'll lift it back up,

turned toward the window. From this mattress

on the floor I canTt see cars or the street or even

phone lines against the sky " only the top

breeze-blown blossoms of the apple tree in my

front yard " but I keep watching for you. I

know you'll be here soon.

You

When you come in you're smiling and out of

breath and the first thing you ask is What did

they say at the infirmary?

" Kiss me first, I say. I canTt help being

playful with you.

You set your books and your the flute case

down, then bend over and kiss me. " Now what

did they say?

" I love your eyes. Kiss me again.

" Be serious.

" Okay. The doctor said itTs some kind of ear

infection and that itTs affecting my sense of

balance. You know, your balance center is in

your eustachian tubes.

" You mean you're getting black spots in

front of your eyes and tunnel vision and diz-

ziness and you haven't been able to stand up for

three days just because of an ear infection?

" Yep. Nosense of balance.

" Whata metaphor.

I reach out and touch your hair. " I know. A

month ago it would have fit me _ perfect,

wouldnTt it? No roots, no vision, no balance. But

this morning I wanted to tell him, ~No, Doc,

youTve got the wrong man. ITm not off-balance.

Not any more. Hell no, ITm happy and together

and in love, Doc, ITm okay. ITve regained my per-

spective.T

You roll your blue eyes and smile, and run a

hand softly down the side of my face. " Are you

hungry?

-" im himery, but | demt want to eat

anything.

ITm not sure that makes sense, because my

lightheadedness has come back.

You make pepper steak, with onions and bell

peppers and sweet-and-sour glaze. I eat a little

bit and feel better, then I finish until only a lit-

tle of the sauce is left on the plate. After a

minute ITm feeling well enough to brush my

teeth.

You sit me up against the wall, fill my tooth-

brush for me, and hold my shoulders steady.

When ITm finished I spit the toothpaste into my

iced tea glass. " Things like that make me hate

being sick.

" Hush. I have a whole ~nother week to take

care of you and ITm going to enjoy it while I can.

Your face is beautiful as you say that.

" I need to practice tonight, you say, easing

me back down gently. " ITm going to do some

dishes and then work on the Mozart.

" Okay. I'll just see if I can sleep some.

I donTt sleep, though. ItTs too early. In a little

while you'll come back in, stepping out of your

stockings and throwing your skirt across the

chair, curling tight around me until your side of

the bed warms up. Then you'll read to me, or

we'll talk about balance and metaphor, love and

levels of meaning. And then we'll sleep.

But now I lie awake listening to you run

water in the kitchen, listening to the gentle clat-

ter of dishes, pots, and silver. YouTre singing to

yourself. The water runs out down the drain;

you dry your hands on a paper towel; I wait for

the next sound: your flute case opening. You

blow a few round breaths inside, warming up, a

minor scale, then a major, and then the first few

notes of the Mozart sonata. My head clears and

I close my eyes and as I listen the air is split into

layers.

October 1978

I

Uneasy Transitions

For no reason

I move from chair to chair

turn on and then off

flourescent and incandescent

light

blow out my only candle

eat a late supper in the summerTs

dark

when I bed down

the neighborTs shepherd puppy barks

growls for hours

litters my lawn

I donTt have to tell you it is difficult to sleep.

CO

two oa? period om? period "

I pick out the echo of a train

tracking through the townTs west end

confuse it with an echo of my blood

count boxcars of hemoglobin

fol a dol me aot

in the magnolia

not far enough away from my bedroom window

a rooster

crews and caws and crows

I am not asleep yet, but | know you are.

at some dot period time dash

some dark-light time

moths drum ragas

against the bone plaster ceiling

Now,

I canTt tell you how difficult it is to awaken.

I would never lie to you.

Robert Jones

ag

40

Crossing the Linville

We are all up early in a clear-floored forest.

Everyone is rising, taking deep breaths of light.

The owls have shut down their emerald lamps.

The wind stirs only the tops of slim trees.

Now hawks are swooping to the creekTs arena.

Now our dogs are cool and lazy on the sand.

Our unborn sons are sleeping, our fathers returning

from their long morning walks.

Our mothers and brothers and sisters are bathing.

Now we burn our silent tithes in the breakfast fire.

We strap the ritual burdens of sustenance

onto each othersT backs, grip our walking sticks

and leap from rock to rock across the water.

Tim Wright

Novena

I guess the birds are gone

This morning has a very thin layer of noise

I focus on

Humming heaters.

The institution wakes

For six o'clock rituals

November toys " the t.v. set

The meter set at eighty

Roast duck stuffed and prepared

We run into the sunshine and the cold

Like little boys

When was the last novena?

I believe I was eight

Kneeling

As fragile as an acolyte

Before the kitchen candles

Democratic though

We would take turns leading

Our prayers

How strange it was

Feeling " trying to feel

The prayers; all of them

For sanity in the world

I looked beyond the candle

And saw nothing...

A drop of moonlight on the kitchen stairs.

Sam Silva

41

Passage

that morning she found him where she had laid him the night before

in a bed of crumpled sheets and muscular pillows

and she thought of eating 40% bran

or maybe eggs

the shower steamed hot water out

from all 11 holes

(the 11th being the center hole)

all of her pores opened to it

she passed a bulletin board on her way

to or from somewhere

an unevenly torn sheet pronounced

ocanoe for sale

$350.00 good condition

... What can go wrong with a canoe??

that day we made a mental list entitled

o101 things that can go wrong with a canoe?

she stopped at 31

and said who cares anyway?

ITm not buying

she entered room 301 at 1:03 and

sat for 57 minutes looking at a green blackboard

and then an earnest young man

cut the green with white lines

and began earnestly speaking

she watched him finger the air

she watched his hands roam

then meet each other

and he began to clean his nails

that evening the bugs circled in an endlessly mad, futile way

around the yellow bulb on her porch

she decided to flick the switch

and set them free

in her room she noticed the hollowed center in her bed once again

like a marble marker worn thin in the middle

she lay facing the ceiling

and thought

I should get up and turn the light off

I should go to sleep.

June Sylvester

42

STRAWBOSS

by Joe Underwood

Softly, the yellowish, afternoon sun pressed

through the only window in the packhouse and

glided to a dusty stop among the tobacco sticks

and empty boxes of rat bait scattered along the

floor. Duke laid his bandaged hand on the sill

and peered cautiously out the window at the

treeline just beyond the tobacco field. His

fingers lay numbly among the fly bodies and

putty chips as his eyes searched the trees. He

breathed heavily but with control.

oDanny,? he muttered aloud to himself. The

word bounced along strands of a dusty spider-

web and stopped abruptly as the creature

rushed out to examine its catch. oWhat the

hellTs keepinT ya??

He looked at his hand and winced at the rusty

red stain. The bandage had been torn from his

sweaty tee shirt and tied loosely with his left

hand. The salt within the bandage was working

its way into the wound, and his hand throbbed

with each heartbeat.

Duke turned from the window and crossed

wearily to a loose chair that had once sported a

wicker bottom. He raised a worn boot to the

seat and laid his hand gently, palm up on his

knee. The calloused and cracked fingers of his

left hand pulled clumsily at the bandage. The

heat pressed close around him and squeezed un-

til salty water rolled down his face and fell to

the wooden boards beneath the chair.

~oDook ... Dook itTs Danny,? came a strained

half-whisper from outside the packhouse. Duke

jerked at the sound and dropped the bandage.

He turned and faced the door as blood crept

slowly down his hand and fell silently to his

bootstrings.

43

Gis:

%

44

The hinges sang as the door opened. A bony

field negro dressed in ancestoral rags stood

silhouetted in the framed opening.

oDook??

~Yea, Danny, ITm in here. Close the door Tfore

someone sees.?

Danny stepped into the packhouse and leaned

back, closing the door behind.

~oDook, I think .. . Lawd, Dook, look at yer

han

Duke raised the angry, swollen hand so that

the blood flowed backwards and dropped from

his wrist.

oYea, he bust it up good.? He regarded the

hand for a moment and then asked, oHe dead??

~oDook, you need to get to a doctor Tfo you

lose that hanT.?

Duke looked at the aging black face with its

lean cheeks and pale yellow eyes fortressed

deep in the skull. Danny instinctively lowered

his eyes as was his custom when a white man

sought an answer there.

oBout an hour ago,? he said at length without

looking up. After a moment he spoke again.

oDook, therT ainTt no reason foT ya to run like ya

doinT. Be different if youTse a nigga, but the law.

oLaw treats trash jusT the same, Danny.?

oBut youTse a strawboss. You had mens

workinT under...?

oI was a field hanT jusT like you. ThatTs jusT a

title they gimme cause I was the onTy white

aan.?

The light softened a little, and the two men

stood facing with eyes downcast in the heat and

dust.

oStill, Dook, if youTd jusT splain to the sheriff

how he cheated ya and tried to fawce .. .? he let

the words trail away without struggle.

oT kilt a man what owns most the propTty in

this county. He pays the sheriff's wages, " not

no travTlin field hanT.?

Danny raised his eyes and studied DukeTs

face. Deep lines ran from the corners of his eyes

to his temples, and a waxy scar melted from his

hairline onto his forehead. It was a kind face,

hardened by sun and wine and drunken

disputes. The eyes had been cloudy with

thought, but they cleared and looked into the

ancient eyes of Danny.

oYou bring my things??

oEverthinT you ast for. Left Tem in a gunny

sack by the broke-over tree near the swamp.?

oThen heTp me with this hanT ~for I bleed to

death.?

Danny tore the remainder of the tee shirt into

strips and took DukeTs arm by the wrist and

studied the hand closely.

~He musta bust near evra bone in there,? he

said as he begun wrapping the strips around the

dark swollen hand. Blood stained each layer as

he worked.

~oDook? You awright??

Duke steadied himself with his good hand

against the back of the chair. He turned and sat

down, weakly, on the edge of the seat. Sweat

beaded on his forehead. When he spoke, his

voice was thin and weak. oGimmie a minute

~fore you wrap anymore. It hurts bad.?

~Sho, Dook. DidnTt mean to hurt ya none. Is it

too tight??

In the golden light, Duke held his hand in his

palm with his elbow resting on his knee and

made no reply. The bandaged hand lay loosely

in his lap. Danny stood with his hands deep in

his pockets and shook his head slowly from side

to side. At length, Duke lifted his head and

looked at the window.

oThat'll haf ta do till I get someTrs else where

folks donTt know me.?

He stood and extended his left hand to the

Negro.

oThanks for ya heTp; you took a big chance.?

DannyTs hand came out of his pocket with a

folded piece of paper which he gave to Duke.

~Keep this witcha foT good luck,? he said.

Duke moved painfully along the rows of

tobacco until he came to the edge of the woods.

He went over his plans as he walked. He would

hop the evening freight as it slowed for the old

bridge near the edge of the swamp. He'd get off

in Raleigh and get his hand looked after, then

catch another freight to Richmond.

He stopped often and rested until he came to

the broken tree and the burlap bag. There he

sat down heavily and leaned his back against

the stump and closed his eyes. The pounding in

his hand made him nauseous, and he was dizzy

from the lost blood.

He unfolded the paper Danny had given him

and held it wearily at arms length. On the front

was a picture of Jesus holding a lamb, peering

out from the creased paper with goodness and

mercy. A broad golden halo orbited his head. On

the back was printed the 23rd Psalm in bold

type, but DukeTs eyes could only focus enough

to read the title.

He lay the paper down beside him and closed

his eyes again. With his good hand he dug

around in the bag and withdrew a bottle of

cheap brown whiskey. He uncorked it, pressed

it to his lips, and heard it bubble as he

swallowed. He lowered the bottle and opened

ee eer este

[See

=

cs a

RT ee SS EL ae

his eyes. Quietly the light had slipped from gold

to magenta and crimson. The legion of trees

awaited trumpets. Jesus and the lamb stared up

at the branches where evening birds sought

shelter from the approaching darkness.

Duke took another long pull from the bottle

and attempted to stand. His head spun and he

reached for the stump with his bandaged hand.

The pain made everything black for a moment.

When he recovered, he stumbled towards the

swamp and bridge.

He could hear the train in the distance. He en-

tered the woods, descended a slight grade, and

sloshed through ankle-deep water towards the

sound. His fevered body resisted. With each

step his concentration shattered, reassembled,

and shattered again. He leaned forward against

a tree and nestled his neck and shoulder into its

trunk. They embraced with a secret love. After

a moment he withdrew and shook his head. He

was nearing delerium and knew he must get on

the train before he passed out.

oThe Lord is my shepherd,? he said thickly as

he sloshed among the cyprus knees. He could

hear the train cutting back power as it ap-

: x alan i t bee

ae ba vn

proached the bridge. His feet moved slowly and

distantly; they seemed far away and beyond his

control. He listened as the engine crossed the

bridge. It was a short train with only one engine

pulling. Through the trees he could see the

whirling light of the locomotive twisting its way

along the horizontal ladder.

oT shall not want,? he whispered as he sank to

his knees in the shallow water beneath the

bridge. He scooped a palmful of the cool dark

water to his face and shivered violently as it

dripped onto his chest.

The train clicked rhythmically across the

bridge before him. The box cars swayed gently

from side to side like a huge cradle. In the pur-

ple light, with half closed eyes he saw a precious

cargo of field hands and strawbosses and land

owners, bathed in innocence and cloaked in the

white robes of forgiveness.

His shoulders sagged; his arms hung loosely

at his sides. oHe leadeth me,? he whispered.

The psalm danced about gracefully in his mind.

He felt himself falling without fear or

hesitation. ~ooBeaneath the still waters.?

; eh 4 . oS : o

he, 6 yy,

~ . Lived

Phone mb Stared mado

sora :

Fossils

After the last rice and pulpy tomato of the afternoon was gone

| washed my dishes

and your gift " a fossil, once a whaleTs ear

(that must have banged and beat with sea sounds long ago)

sat on my table

its barnacles dry in the sifting light of my kitchen

Lifting my hands from the stained red water

| notice how they have begun to pucker and softly whiten

and this is how it goes

we are young fruit

we dry like raisins

then we are the stone

In the high keening sound of a new storm

| heard an echo from my childhood

from many childhoods ago

and before the rain drummed down

In its ancient, vicious pulse

| raced to shut my windows

keep in the warmth

stay dry

In this way we turn to bone

In this way we are

stones offered up from the sea

June Sylvester

What to Know About Hogs

Stand on the runway. Drop

slop to sows without falling off.

Know diets. Diseases they catch.

Learn to watch

the sallow piglets litter-clumped

toasting under red heat-lamps

breeding boars with balls dung-dragging

white eyes wild rolling.

Hear their shrieks. They trot sure-footed

snort and root

through kudzu snake-routes.

They toss rattlers with their long snouts,

slash them under trotters, tear

with sharp pig-teeth in mid-air.

You learn this. And: you've seen

photos: meat markets in Spain

where whole roast shoats hang at eyelevel,

sly mouths choked with apples...

Eaters of anything. Rats and slugs

snakes shit other pigs:

think this as you watch: they found him

three days later. Last year. A man

you knew well " blinded, stroke-struck

while slopping his stock,

black clot in his brain "

he tottered on the runway, fell into the pen

of hungry sows. You carry on

and pray he died on the way down.

Luke Whisnant

47

48

at aay

anew o

oA

The Fish Kill

for Ed Jones, 1958-1979

A procession of white, cylindrical bellies A flock of birds is spreading in the sky

is floating down from a night they allswaminto as though the pages of some dark novel

far upstream. Occasionally, a tail curls

have opened, letting out all its words;

slowly back and forth, shaking out its stillness. their shadows

The dead ones keep drinking, pretending to stain the creek in tracts as big as clouds,

breathe, their mouths opened into the current dimming everything, until the first fish body

in perfect fish kisses.

rounds a sharp bend back into the light,

and breaking out into the spray

over the table of a high waterfall, they

are not falling, not ever.

Tim Wright

like this

iam like this place.

sheer heights surround

depths rummaged by endless

= hooks.

=

= there is a difference

YH of course,

these granite walls are

much more real.

still

the colors mate,

red and pinks trace veins

on the babyskull sky.

i know these colors well.

i feel them as the blind

feel them,

untouched.

beneath the sheen of sunbleached

water lies a blue.

none of this is new

though iam new,

and lucky.

clutching my unspent time

like a ticket out,

iam like this place,

solid and vertical beside

flowing aquaintance,

reflected now by deep pools

where friendships glide

like fish.

S. Phillip Miles

49

Dangling

after a painting by Degas

As though her strained insides

are slowly sliding

out of her suspended body

she

dangles

above the circus crowd. To her, we're colored chips

of a kaleidoscope. Her knees are bent

to ease pressure

as the fire rages against her teeth. The rope, taut

hangs her, holds her " some hunterTs kill

creaking

she gently sways and twists.

The ceiling walls pulse red and orange second

by

second.

The thought that pain might

overcome her, that the nail-like grip

of her teeth might slip,

sends waves of whispers

through the crowd.

Jeffrey Joseph

50

Survivors

You are afraid The river is

of water but itTs never blue singing and high water

too late sweeping dreams out

for sailing away to sea

take my skin and stitch but the stars are deeper

long white sails than the river

build my bones into the wind is wiser than

the body of a boat anywhere the riverTs been |

turn my eyes into a hot white star still, rivers

your north star like lovers should

never be fully explored.

Denise Andrews

Ocracoke

On a darkening slice

of island, you came

without my calling.

The old, old scents

of salt, and pine

and driftwood burning

met you at the edge

of many voices, put you

to sleep on rocks

in the sea wind,

planted dreams

of people saying this

or that. And now,

with the tide

at the reach

of my backward feeling,

you and | yet sleep

In the night-shy heat,

lie feverish together

and feel

in the eye of our front

the tremble of soft friction,

land and wave.

Tim Wright

BZ

oo

SSE

SG

BS

EOI LT

f

j

g

|

;

#:

j

g

j

LL Ge Ye

Zo

54

Lineage

Found in 1978 by your fingers:

the curved line running from the edge

of my nose to the corner

of my mouth

| had to smile at your tracing touch

(and deepened the creases there)

That Spring we rowed out over the cypress stained water

the sun was bright and sharp as pain

| squinted into the glare and you turned and caught me

your face folded into laughter and

you said | looked like a near-sighted Chinese woman

A history is furrowed in my forehead

there - moments crossed in concentration

here - times when your annoying habits

gathered knots between my brows

and pulled them taut

These moments have taken form

and are etched in the fine lines

of my face

while other women cream and mask

and salve to smoothness their surfaces

| will wear these years you have given me

and, yes, | will wrinkle with pride.

June Sylvester

with one class

tomorrow

please marry me tonight

or just a short

honey moon pie.

blindly like nylon

bristles | crash through your

hair, new found adoration

you Say is my fault.

tongue by a fat

pebble in a stream. nose

of steel grind bright sparks.

make eyes resolve

tempestuous contours.

like a candle " singe me.

Michael Loderstedt

55

56

ink blot cat

aggie

looks at me so

close

with

reason

for the black.

and real live whiskers

too near

for

FOCWS,

| was

the space behind her ears

she liked

and the reason

for the

white.

Michael Loderstedt

PARADOX

Lilies possessed the room for nearly a week,

Suspended

In a few inches of water from the kitchen sink:

A moment's captured grace

Like a dancer stilled in movement,

A snowflake caught against the window pane.

Then as if all at once,

The way buds burst

And leaves fall

The petals blackened like banana peels,

Crumpled into an arthritic fist, and

Got thrown into the garbage.

Ernest Marshall

TELE te

The gold is tucked away

behind blue-braille numbers.

Coded, secret.

Balance achieves balance

and rocking between the right hand

side of your secrecy and the left

leaves them nothing to see

but your back, your busy fingers.

Property is again protected.

Yet those eyes,

those sliding screens.

~~One moment pleaseT and one moment

might have established a kind of fund

to be drawn from without credentials.

But the wallet folded

every world youTd been in

in two, withdrawing all deposits

you thought you owned.

Even that gets invested

in some stock response

to the yellow slips

dropping at your feet

like smaller nods,

wise to the total transaction.

Phillip Arrington

*A 24-hour banking machine at

Wachovia Trust

OY

A MATTER OF EXISTING WILL (in fragments)

You cannot inspire until you expire.

Laugh

and the angst in your throat

like grinding bones,

or the sound of salt

shaken,

echoes echoes.

Let clay re-acquaint with clay.

Dance

and your fumbling feet,

not quite ever leaving earth, will know

treasures that are here

and there-

honed and hued.

Eye the particular.

Blink

and the bright brow of sundown

blanks.

It all goes bleak to black-

hole- space

and nothing period.

Robert Jones

58

Plum Stone

You hate it when

I drop the slippery wet stone

of a plum

into the wastebasket in your study.

This wastebasket you say

is for paper,

dry stuff.

This stone I say

only stains

the poems you have

torn.

Look

This crumpled sheet

has yellow ochre rings.

Sue Aydelette

oDaddy,

Why donTt Ijust stop talking right now so I will know

my last words??

Kempten L. Daniel

LV

WRITERS

SUE AYDELETTE is a senior in the

writing program and this yearTs

Rebe/ art editor.

DENISE ANDREWS is a_ senior

writing major whose poems have

appeared in past issues of The

Rebel and Tar River Poetry.

PHILLIP ARRINGTON is a lecturer in

English at ECU. He is currently head

of the Poetry Forum and a past

editor of The Rebel.

KAREN BLANSFIELD is a graduate

student in English who has recently

completed her thesis. She has

previously published poems in The

Rebel and Tar River Poetry.

KATHY CRISP is a junior from

Washington, N.C., majoring in

creative writing. She has previously

published poems in Straight, a

Christian magazine.

HAL DANIEL is a Professor of

Speech, Language and Auditory

Pathology at ECU who has

published extensively in his field.

This is his first appearance in The

Rebel.

KEMPTEN LOVE DANIEL is_ the

prodigious seven year-old son of

Hal Daniel who attends Morehead

School in Greensboro. This is his

publication debut.

JOE DUDASIK, a long standing

member of the Poetry Forum, is

both a poet and an artist. His work

has been published in past editions

of The Rebel and Tar River Poetry.

COLLEEN FLYNN is a senior whose

poems have appeared in previous

issues Of The Rebe/ and Tar River

Poetry. Colleen is the editor of this

yearTs Rebel.

ROBERT JONES is a member of the

Poetry Forum and last year served

as associate editor of The Rebel.

JEFFREY JOSEPH is a senior writing

major from Danville, Va. He is a

member of the Poetry Forum and

has published in numerous small

magazines.

ERNEST MARSHALL is a teacher in

the Philosophy Department at ECU

who has been reading and writing

poetry intermittently for many

years. This is his first appearance in

The Rebel.

S. PHILLIP MILES, an ECU alumnus,

teaches English in Fayetteville, N.C.

He has published poems in several

past issues of The Rebel.

CHERYL RIBINO is _" currently

teaching poetry in the English

department. This is her first ap-

pearance in The Rebel.

SAM SILVA is a member of the

Poetry Forum who lives in Golds-

boro, N.C.

JUNE SYLVESTER is a senior from

Elizabeth City, N.C., majoring in

writing. Her poem ~The CallingT

won this yearTs JeffreyTs Beer and

Wine Poetry Award. This is her first

appearance in The Rebel.

JOE UNDERWOOD is a graduate

student in English who won this

yearTs prose award for his short

story ~~Strawboss.?T This is his first

publication in The Rebel.

LUKE WHISNANT is _ currently

studying creativeT writing at

Washington University in St. Louis.

He is a past editor of The Rebel.

TIM WRIGHT is a graduate student

in English at ECU and this yearTs

Rebel literary editor. This is his third

appearance in The Rebel.

ARTISTS

LISA BATEMAN is a senior painting

major at ECU. The cover piece of

this yearTs Rebe/ marks her first ap-

pearance in the magazine.

ROBERT DANIEL is a_ graduate

painting major in the ECU art de-

partment. Before coming to Green-

ville, Robert was artist-in-residence

in Harnett County.

SID DAVIS is a High Point native

working toward a BFA in com-

mercial art. He is presently a free

lance commercial artist.

RITA EARLEY is a graduate student -

MFA Ceramics. This is his first ap-

pearance in Rebel.

STEPHEN EDGERTON is a senior

seeking a BFA in painting with a

minor in drawing. He is originally

from Philadelphus, N.C. His mixed

media piece won best in show this

year.

BETSY KURZINGER is an MFA can-

didate in Communications Art. She

is currently participating in in-

ternational postal art correspon-

dence.

DAVID LARSON is a junior working

toward a BFA in painting. He has

two pieces in this issue of Jhe

Rebel.

MICHAEL LODERSTEDT is a senior in

printmaking with an interest in

collagraphs. His work has been

exhibited in Kate Lewis and Gray

galleries, and recently at the Univer-

sity of Florida.

ELLA MALLENBAUM is currently

seeking an MFA in painting. She

has previously taught art and

English in Pennsylvania public

schools.

DAVID NORRIS is a senior from

Charlotte majoring in print making.

This is his third appearance in The

Rebel.

MARK PETERSON is a sophomore

BFA painting major. He attended

Governor's School in 1974. He con-

tinually strives to express his

musical interests through his art-

work.

PETER PODESZWA is a graphic arts

major at ECU. He is an avid

photographer and currently head of

the student Photo Lab.

JUDSON POOLE was formerly an art

student at ECU. He has previously

done illustrations for The Rebel.

ROXANNE REEP is a_ graduate

student in jewelry design who has

had work purchased by R.J.

Reynolds. This is her third ap-

pearance in The Rebel.

BRENDA WILLIAMS is a senior in

Communications Art and a Student

Union artist. Last year she won first

place in the Rebe/ Art Show for a

black and white photo.

STEPHEN WILLIAMS is a graduate

student in the Dept. of English. His

photograph comes out of a collec-

tion of images from his summer trip

to England.