[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

REBEL76

ee ee

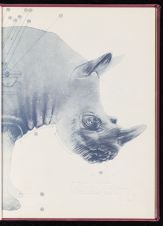

' NOTE ON THE COVER:

The cover is an intaglio print by Matt Smartt. The legend may be

found on the back cover. The print won first prize in the Rebel art contest

this year. Several other works by Smartt appear in this issue of the Rebel.

Printed by National Printing Co.

Copyright ? REBEL '76

Ag Slane

sTatt_

jeff rollins

daniel o'shea. ..

david bosnick |

ART STAFF. .

iaih hie eis published by the

students of East Carolina University.

Offices are located in the Publications

Center on the East Carolina campus.

Inquiries and contributions should be

directed to THE REBEL, Mendenhall

Sudent Center, Rast Carolina

University, Greenville, N.C. 27834.

Copyright ? 1976, East Carolina Univer-

sity Student Government Association.

None of the materials herein may be

reproduced in any form whatsoever

without written permission.

Prizes for the literary-art contest held

this Fall were partially provided by a

_. MANAG. EGITOR

harry hartofelis

douG MANGUM

grant from the North Carolina Council of

the Arts. Winners were: Susan Bittner;

first place prose for "Tyger, Tyger', and

Bob Glover; second place prose for "The

Way It Would Have Been If He Had Not

Died So Suddenly in the Fall." Helena

Woodard, Luke Whisnant, and Richard

Wayne Smith each won honors for their

poems "Ash and Cinder", "Not Crying',

and "At Just Some Gentle Moment"

respectively. Our cover is Matt Smartt's

first place winner, "Blue Print (The

Rhino That Ate Cleveland)." Second

place in art went to Betsy Kurzinger for

her untitled photograph found on page

61.

Sate

Table of CONTENTS

IMATOCUCHION, c .o.n..44 05 ns se ae a

CTALIOTY. ? pa ee i p. 40

LITERARY

The Crayon ane dle Coin... i621. Richard Wayne Simin ......6. 25. = p.4

A Collepe Sivry 02.055 Jetrayolling, b>

LiGot Nien 2 i David Besmice,. 62. ...55. 3 ee. pd

Deserted Nested . kk a eee Bob Glover. .2..4..4.5550......... p, 15

Operating Room .. 2. 6244465 6.44455 Taylor Keone ...00? yess ee Bp: 16

ASME Mien 6. Archie Gosvor, (4... 1 pels

pumcide amd Sylvia Plath. ...-......-. . Palisa Wiles. 63 p. 24

Ts PROGR e335 ii 5. PamailtfooMiies.. 2... Pp. ao

Te Apne iene a L.ME Re@seubers = ......). 33... 2... p. 26

"You area pentle man. 25 0. CeleCapnce. gc po

ey eta Per 6 DUSaMIMENCR. =. 2 p. 22

MBS 0S Thenesa@litlke ...?5 55.09) 455 ,...5 14: p. 34

The Way 4 Would Have Been........ BobGlover? =... 2 8 3 p..3d

Al BAM a David Bostick .....055555.. =. 54 p. 37

AvVGIOR 2.205 565. ee Pamela Wilkow. 0 66255 p. 38

The Climax ot Composition. ....:.. . Theresa?peistt....6.. ... .. p. 39

ame oo Richard ayme Smith... .....:.5... 3 p. 56

A Reminder To Mysell.... 4. che. Jaci SGEVOEEM Dor

The Unsung lbove Sone. :. cv... LE Wosempere 2... p. 58

Mbeny Deel oat llelena y) ootamd ?? 2s) ce poo

Ashamd Cinder.) 4216 Helewa Woodard >... p. 60

Last Unicorn... 20500 3 Thepesa Sperolt. 2...) p. 61

At JustSome Gentle Moment........ Richipa Warne Sit... 4... Pp, 62

How Te Be Oceult ....4. 3.0. Thome liane = ?. ... = ........ p. 63

NobOrvyines 403 200 Luke isan... p.65

illusTRATION

"The Rhine That Ate Cleveland' ..... blatiSmartt 2... ... .... . . Cover

A College Biory. ... ee Tem flolizeaw..4 0... p.o

ASuialitigm:. 3... 2 2 Mati emartl..-.?.6..5,...0.:., vee

Tyger; 15 @or 0 DamielO'Shea.,. ......., p. 29

Ty

Ya

She was a strikingly attractive girl,

with long, fine brown hair, wide ex-

pressive eyes, and a delicate, charming lit-

tle nose. We had just been introduced,

and, as I had sat down at her and her

friend's table, we were now getting to

know each other.

"You work with the Rebel?" she asked,

her hands folded petitly beside a saucer.

"Yes, Ido. What do you think of the

magazine?" I asked, putting down my cof-

fee cup.

"Oh," she smiled, "I never read it. It's

so intellectual!"

I laughed then, and came to find out she

was a remarkably aware girl. Later on I

thought very much about what she had

said.

Subsuming the sometimes un-

compromisable differences in each of our

staff members' esthetics, there has been

one mutually agreed upon principle: that

the Rebel should throw its pince-nez into

the fireplace in order to more clearly see

what the students, their art, and con-

sequently their magazine are all about. It

has been a principle easy to adhere to, for

not surprisingly, we have found in com-

mon voices much uncommon insight. We

have been delightfully reminded time and

again that beauty's hands are not always

clean, and that, often as not, she doesn't

know long words.

It has been said that in a college

magazine there should be opportunity for

works to be published that might be con-

sidered too avant-garde or too con-

troversial by the established magazines. It

is a point. Indeed, a college magazine, fun-

ded by a school organ and not financially

pressured by the opinion of its readership,

can be the platform from which the exotic

land of "New Literature" may be seen.

There are, however, pitfalls in this line

of thinking. Often, editors have been en-

tranced by the macabre or blinded by the

sensational, and, in seeking "something

different," as editors are wont to do, they

often pass over works of merit equal to or

greater than others, though of lesser

ostentation.

We have attempted in this Rebel to

allow the good to be our guide, rather

than the sensational. This staff feels that

'to shock" is a technique valid only in the

exceptional case. Consequently, though

you will find bountiful surprises

throughout the book, we hope they will all

be pleasant and moreover, intriguing.

Our stories spring from home soil.

You'll recognize in "A Small Man" the

land of your grandfathers, as in "A

College Story" you will see rather much of

a reflection of yourselves. The implied

drama in "Tyger, Tyger" and "The Way It

Would Have Been If He Had Not Died So

Suddenly In The Fall" merited them both

as prize winners in the contest we held

this fall, and makes them stories not

quickly forgotten.

The poems you'll find are as ostensibly

diverse as the prose-works. Nearly all are

written in so called "free verse"; treating

a variety of subjects with freshness and

immediacy. The pellucid imagery in 'Ash

and Cinder" and "Not Crying" makes for

fascinating reading, as does the extremely

well-controlled balance/tension in "At

Just Some Gentle Moment."

In nearly all of the poems we have

selected you may detect the search for

constancy, at least, if not sublimity, in our

anxious age. They are young poets, with

the optimism in their new blood in con-

stant interplay with the fear in their new

neuroses. Phillip Miles, in his poem titled

"this poem" speaks crisply of this tension;

"+. MY Words

sprout sudden sweat;

awkward new disease

of the sun.

... my cautious words

creep the hollow darkness

in awe."

These are poems that bring the elemen-

ts of inward existence into the realm of

our consciousness, with striking results.

They are evocative of the nature of our

searching as only poetry can be, giving

scent and sound and near tactile presence

to that in us which we can never know.

This Rebel offers more art for your

study and perusal than has ever been of-

fered before. This staff feels that greater

and greater emphasis should be placed on

the graphic arts in succeeding Rebels. Our

School of Art is a nationally renowned

source of talent, as well as being a

dynamic factor in the curricular life here

at East Carolina. Our cover, Matt Smar-

tt's "The Rhino That Ate Cleveland"

balances superb technique with not a little

humor, achieving, we think, fascinating

results.

The staff of Rebel 76 would like to ex-

press our sincere thanks to the students

and faculty of the School of Art, whose

time energy and talent are apparent on

every page of the magazine. To the

students who submitted stories, poetry

and art goes the appreciation of every

reader of the magazine; without you ar-

tists and writers there would be no

magazine. Rebel 76 also owes a special

debt to Mr. Ovid Pierce and Dr. Erwin

Hester, who lent their support when sup-

port was sorely needed.

Assembling Rebel 76 has been a most

rewarding endeavor for each one of us on

the staff; a project as enriching as

working in the exciting proximity of art

can be. We hope that reading the

magazine will be just as rewarding for

you; not to mention entertaining!

}

/

THE CRAYON AND THE COIN

Feeling old at twenty-six

I pose an air of wisdom

for smaller children

who look at me

as they might stare

at some rude large presence

that walks straight through

their hopscotch world

expressed in crayon

jagged waxy red

on my driveway.

But they gather no interest

in proffered words

which cannot tell them better

how to chase the waiting coin

they throw into a square;

one foot,

one foot,

bend and reach

and take the prize.

No, they will not brook me long

for, if need be,

the crayon and the coin

can be moved,

and a new domain

will be drawn,

unspoiled by those

of a foreign age

who puzzle over games

which urge one

jump,

jump,

where you must.

fHEE

The Scholars

Bald heads forgetful of their sins,

Old, learned, respectable bald heads

Edit and annotate the lines

That young men, tossing on their beds,

Rhymed out in love's despair

To flatter beauty's ignorant ear.

All shuffle there; all cough in ink;

All wear the carpet with their shoes;

All think what other people think;

All know the man their neighbour knows.

Lord, what would they say

Did their Catullus walk that way?

WB. Yeats

yy

Sa ica HERBIE 'Scripted

r (y} nal

Story

ollege

My eyes were beginning to stray from my book and

before I realized what I was doing I was simply staring out

the window, watching the headlights from passing cars

raise caravans of shadows from the roadside. The book I

was reading held few delights, with long stretches of

lifelessness enlivened by only occasional moments of

reward. I put the book down.

As usual, my thoughts went to Kathy. She was an odd

girl, I thought. Maybe -- No, why should I call her? Just so

she can tell me, in that infuriating way of hers, as if she

were talking to a stranger almost, that she just couldn't go

out with me? That she was just awfully sorry (there her

voice might tremble just a little) but that she really needed

to stay at home and work?

I went to the cabinet and poured a whiskey. I just can't

figure her out, I thought. But, then again, maybe I can.

The whiskey was a jolt. I poured another and sat down.

I remembered when I had first met her, in

Richmond, at one of those horrible parties

where the North Carolina newly rich and the

Virginia named rich get together to speak oh

so dolefully about the disappearance of the

"old Europe" and how, really there is nowhere

to go now but to South Africa.

Well, as I come from a long, distinguished

line of poor but honest school teachers and

just couldn't remember the last time that I

had been to South Africa, I had stationed

myself quietly by the piano, trying at the

same time to be as unobtrusive yet as "at

home" as possible, when she had come and

asked the pianist to play a piece by Dvorak.

She was a smallish girl, with long, rather

thick brown hair and a pure, fair skin. Light

blue veins were softly visible at the base of

her neck, as they were, I noticed later, at her

slender, nearly tiny wrists. She looked at me

with a humor that made me blush, and

smiling, asked, "Do you like Dvorak?"

"Well, yes, I rather do." was my awkward

reply.

"You do rather?" she smiled, almost

laughing at my uneasiness.

"Uh-huh" I answered, "I thank he kin shur

make up a toon!"

"So do I" she laughed, flashing her bright,

lovely eyes into mine, and then she left.

I had wanted to speak more with her af-

terwards but my friends had had to leave and

I with them. I was really impressed by her.

That was during the summer. Early on, the

next school year, I saw her leaving one of the

art buildings on campus. I was overjoyed. I

caught her attention and we went out that

night, and many nights afterwards. Things

went well for about a year. I would stay at

her apartment for a few days and then we

would move back into mine. I had the best

typewriter and she the best stereo. Funny,

maybe we were attracted to each other by our

differences. Where I was outlandish she was

sensible, where I was moody she was, it

seemed to me, ever even-tempered. I needed

her.

I rose from the chair to pour myself another

drink, a sherry this time, and sat back down.

Now, though, she will hardly speak to me, I

thought. I remember the conversation we had

had two weeks before in the restaurant. She

was wanting to see less of me and I had asked

her why.

"Because you are lying to yourself, Jess."

she had said, "I've been feeling it more

strongly than ever just lately."

"Lying?" the word was particularly un-

pleasant.

"T don't know what it is,' she twirled her

napkin, "but, Jess, it seems like you're not

really looking at things at all rationally,

like... I don't know." She looked down at the

table.

"What do you mean? Not looking at things

rationally!"

"Well, you're so hypersensitive sometimes.

I think maybe you're drinking more... much

more than you used to."

I was hot suddenly, and for some reason,

almost mad at her.

"I really don't know what you mean."

"O.K.," she put the napkin down and braced

her shoulders, "You're stagnating, Jess." It's

obvious, if for no other reason, in that you're

not writing anymore."

That hurt, and she knew it.

"Well," | said, "1 ean t write all the time. I

mean, I'm not some machine that can produce

a specified quota of words a week, you know,

and stagnating! I think that's a hell of a

statement!"

dees...

"Anyway," I said too quickly, "What would

you know about writing, you, who sit ina

studio all day and draw .. . advertisements!"

"Alright," she said firmly, "You can sneer

all you want. You can explain all you want.

That's fine,Tll believe anything you say. May

we please leave?"

I haven't seen her since I left her at her

apartment. When I call... well, I've already

told you about that.

I surveyed my room, a small room in the

second story of an older house that I was ren-

ting. What should I do now? I wondered. I

saw the record player -- no, don't want to

listen to music. My potted plants -- I can work

with them tomorrow afternoon. I could brush

up on my German, nah, my German can wait.

All this was circumlocution and I knew it. I

pulled on my "William Butler Yeats" sweater

and decided that I would spend an evening of

stimulating conversation with some of my

friends. Yes, I thought, just what I need. Once

the sweater was on I looked at myself in the

mirror, sickened at the entire euphemistic

situation and put on a street-jacket instead.

I was going to my favorite bar.

You see, I like to drink. But only around in-

telligent and sensitive people, of course. To

hear erudite conversation that is given the im-

99

Maia

petous of beverages is really a marvellous

way to spend an evening. Sometimes, though,

when the crowd at the Cairo is of the coffee-

drinking sort, I might retire to the adjacent

pool-hall for beer, but only because I feel that

the more educated of our society can benefit

immensely from exposure to people of lesser

erudition and refinement. It is interesting, I

think, that the so-called "simple people" can

hold forth some startlingly profound opinions,

and even more so, with enough beer in me to

expand my definitions, I have heard more

than one ostensibly dull slattern completely

astound me in "unpremeditated art." They are

"diamonds in the rough" so to speak, with a

marvellously naive diction.

So, with my street-jacket on, (I really can't

stand to look like an aesthete) I set out for

the good ol' Cairo. The Cairo is only a short

walk from my apartment, a pleasant little

walk, especially in the autumn when the sun-

sets are so stupendous. It is one of the few

bars in the little college town where I live

where people of intelligence go. I really enjoy

being there when, after a carafe or two, the

table is lit as by lanterns with animated faces,

all proposing or defeating some aspect of the

always polemic subject at hand. It's really

loads of fun. Students from the university

come there, as do the younger professors. The

older professors come there too, but they are

usually looking for some freshman or another

who needs to pass their course, and they are

not very interested in the repartee. The chat-

ter of these old ones reminds one of the sound

of dried and brown leaves blowing down the

street long after Fall has spent her colors.

I walked into the Cairo and surveyed the

situation. There was a table filled with people

that I knew, but they were drinking coffee. I

waved to them as noncommitally as I could

and looked around some more. There was a

booth toward the back where two

homosexuals were almost making out. They

think that they are so cute. Someone who I

had never seen before was sitting at the bar

drinking, but he didn't look too interesting.

Who is that waving? Oh, no, Carol and Joanie.

Can't escape now.

Carol and Joanie are both English majors

and philosophy minors. Both want to be

editors of progressive women's magazines,

and both are terribly boring. They were sit-

ting with three unmistakable grad students in

pedantry.

Let me tell you the oddest thing. One night

this particularly bright guy, who I haven't

seen around here for quite some time for some

reason, accused Carol of being actually afraid

to get pregnant. I thought she would die! She

looked at him with eyes for a second misty,

then cold and hot, oh, what a look she gave

him! She got so angry that she threw a glass

of rose' all over him, and then marched out,

quickly followed by Joanie. The guy begged

his pardon then and left too. Incidents like

that rarely happen here.

So there I was, sitting with Carol and

Joanie and the three grads. I was sitting

beside Joanie and I noticed the tiny glint of a

pierced ear-ring bedded in her flesh. It

irritated me. I drank a beer quickly and or-

dered another.

They were talking about administrative

problems at school, a subject that has always

bored me, so I entertained myself by looking

at the different people who had come to the

Cairo. I saw Theresa and her boy-tfriend, ex-

cuse me, room-mate, sitting at a table. I saw

Carl, who was standing at the bar ordering a

drink. I once took Logic from him and he was

awfully boring. There's Mary retelling for the

hundreth time about her year in Paris, spent

teaching at the Sorbonne. "I had the only

broom-closet with a bath in Paris!" Doug,

english, english, english, was talking with that

guy at the bar who I hadn't seen before. I

took a long drink of my beer.

A tired night at the Cairo, I was afraid. But

it is early yet, I consoled myself, tasting the

bitter, eudsy dregs of my beer. I decided on a

grosser and viler stimulant, a whisky-sour,

and sent the waitress scurrying. Carol and

Joanie and the three wisemen were talking

now about India. Carol said that she thought

that India was a''wonderful, and lovely, and

foolish" country, though she had never been

there, Joanie agreed. I was pressed for an

opinion. Well, I'll confess, I've never done any

extensive thinking on India but I said that I

thought that the Indians were probably

basically happy with their country or else

they would change it. The wise-man who

hadn't drunk hardly any wine at all said that

he agreed with me, and exclaimed "Ecce

homo!" enthusiastically. He had been saying

that all night.

I took a long, stinging swallow and decided

to explore. Good-bye, Carol and Joanie, good-

bye, Thomas, Richard and Harold. Ah, alone

with my whisky-sour, my only comfort in

these the worst of times. I thought at first to

sit at Theresa and her room-mate's table but

then, on noticing the frightening aridity of my

glass I decided that I would speak with Doug,

immenent poet, writer, reviewer and reader,

who graces each English classroom with his

profound and thought-provoking insights into

the geniuses of Shakespeare and Milton,

Dryden and Bacon. He was also a good friend

of Kathy's. I didn't know if I was up to a talk

with him or not, but I couldn't get another

drink without a least saying something to him.

He was still talking with that stranger.

'Hi, Doug," said I, "How are you?"

"Working a lot." he answered. He really

does work hard, which is boring but com-

mendable.

"I don't think I know your friend." I said,

laying the groundwork for an easy and

masterfally camoflauged extrication from the

company of these two gentlemen.

"Oh, I'm sorry, Jess, this is Bob, Bob this is

Jess. Jess is one of our most promising

writers. But I must say, Jess, I haven't seen

any of your things out lately."

I almost bit blood from my lip. "Things!" He

should call my work "things?"

"Well, right now, Doug, I'm working on a

longish short story that just may develop into

a novella, but I am yet unsure on how many

sub-plots to entwine." I didn't care how I

sounded, I was enraged. "I am toying with the

idea of coalescing my plots into, into...a

fugue! Yes! A novel worked out into fugal

form!"

"Oh... that sounds fascinating." blandly

mouthed the damned teacher's pet.

Let me tell you. I am really quite proud of

my ability to hold my liquor. I do not get

irrational. I don't curse more often or more

loudly than I usually do, and I don't let petty

things place me in a bad humor, at least for

long. I decided that right then my con-

versation with Doug was not what I needed if

I wanted to enjoy the rest of the evening. He

thinks that I'm drunk, I thought. Well, I'm

not, perhaps I sound a little bibulous, but that

is perfectly in order, and if his delicate sense

of propriety is disturbed by that then we are

speaking of his narrowness, not of mine.

Having convinced myself that I was in the

right I tried to think of some way to enter

back into the conversation with dignity

preserved, and was steeling myself for the

coldest of civility when Doug solved my

problem for me.

"Look!" he said, "There are Carol and

Joanie! I really must speak with them. Excuse

me, will you?" and with that he was off,

carrying his Budweiser that surely must be

warm enough to evaporate by now. I was left

alone with, what was his name?, oh yes, Bob.

"T don't think I've ever seen you here

before, have I, Bob?"

"No. I just arrived from Atlanta where I am

working on my thesis."

"What brings you to our small but lovely

town?"

"Well, 'm doing some research on Thomas

Wolfe. I'm trying to account for some of the

seemingly senseless nuances in his books, at-

tempting to link them with southern life and

perception."

I took an immediate liking to him. Thomas

Wolfe is my literary father. I think of myself

as a reincarnation of Wolfe, of sorts.

Bob was extremely slender, with black hair

of a nondescript length and an uncombed

black beard. He had on utilitarian wire-

rimmed glasses that were safely hooked to

almost ludicrously large ears. I noticed he was

smoking Luckies, and had begun to drink a

martini. With vices like those I knew he was

trustworthy.

"I once knew someone who had spoken with

Wolfe's older brother." I offered. "They said

that his brother wasn't very enlightening.

They said that he thought his brother was the

greatest writer in the whole world but that he

hadn't even read a single book by Wolfe."

"Yes, ve spoken with him myself. "Bob ad-

mitted softly, looking down at the bar. "I

thought he was extremely illuminating,

though. Not in the explicit way that most

people want him to be, but in a subtler and

more truthful way."

Well, the conversation made easy progress

through the night. I slowed down on my

whiskey sours; with stimulating company who

needs to drink? This guy was a scholar in the

real sense of the word, so much so, in fact,

that I was surprised that he drank at all. He

was an immensely interesting person to talk

with; a nice respite from the artistic types

that are too much trouble to talk with for

what they're worth.

It was later on in the night, after a few

more drinks, that Bob began to color his

speech a bit differently. He moved a bit too

easily from the "passion of Wolfe's style" to

''our own passion, like his, nearly in-

containable because of our volatile Southern

blood." he spoke less and less of the ex-

citement of Wolfe's art and increasingly of a

more immediate excitement. He mumbled

something about "tonight" and looked at me

conspiratorily, then moved his eyes back to

home-base, his glass. I decided that I had bet-

ter sober up with a glass of burgundy. Then I

thought, what the heck, I've told fags to get

lost before, and if he isn't a fag then I don't

have anything to worry about, so I ordered

another drink.

Things began to get a little better. He

began to speak about women in exculpatingly

licentious tones, and, after mentioning that

Wolfe was quite a regular with prostitutes, he

wondered aloud about the possibility of fin-

ding one, or a couple, he smiled.

Well, I admit, I had had too much to drink.

I had been drinking orange juice like Florida

was about to roll under the sea and I was

about ready for anything. I had never gone to

a prostitute before, although I had spoken

with many. The idea had always sort of

repulsed me, to tell you the truth. But now,

the more I thought about the idea, the more I

liked it. What if I didn't go? Tomorrow mor-

ning would just be another morning with a

hang-over, with me feeling like I had spoken

too much and had acted like a fool the night

before. It really is sort of a paradox. Here I

am playing the part of a latter-day Byron (I

mean, how else can I make my drinking look

acceptable to all the Dougs at school, all those

bright, industrious people who can write

brilliant theses but for all their brains couldn't

write a decent poem for anything, those

neuroses-less sheep who walk straight down

composition paper lines never wondering if

there might be other ways to go,) and yet

really it is a shame. If they knew the real ex-

tent of my experience then they would know

the extent of my drunkness, and (I winced at

this thought) the real extent of my talent.

"Yes!" I said bravely. "There is a pool-hall

very near here where we are sure to find

some women, or rather someone who can lead

us to some."

"Good, let's go." answered Bob, " 'and

passion, with it's bloody beak, tore at his

heart.

Doug met us at the door, "You're leaving

too?" he asked. "I think I've about had enough

of this place for one night."

"Yes," I said, "we're leaving."

"I guess its home for me," he almost spoke

into his coat, "Ive some reading I need to

finish." He hesitated, "But what the heck,

why don't you two come over for a while? It's

been some time since I've had a chance to

speak with you, Jess. Kathy has asked about

you." Our eyes never met.

Bob was standing at the door, ready to

leave. I felt pulled in two directions. I needed

a drink.

"Thank you anyway,' I replied more coldly

than I wanted. "But we do have other plans."

And that something which made both us ner-

vous quickly disappeared into civility. I had

lost a chance.

"Well, hope you two have a fine old time.

See you later." And he was gone.

It was a short walk to the pool-hall, during

which I fought with all my energies the horrid

moments of licidity that welled up before me.

I'll get some beer at the pool-hall, I promised

myself. It's hard for me to believe that some

people really have sex stone cold sober, but;

I've heard of it being done.

We did finally get there. The pool-hall is

just a short distance from the Cairo, but ina

completely different hemisphere. There were

eight tables, in rows of four, above each hung

low table lamps that were shining a heavy

yellow light on the green felt. Only three of

the tables were being used. Lanky, loose-

jointed blacks were playing around one table

and their thick, mellifluous speech rolled slow

and ignoble into the air. The other two tables

were being used by whites in black cowboy

boots and shirts with the sleeves cut off at the

shoulder. Their's was a speech with less

rhythm; twangy and hard. I bought a beer

and Bob stayed near the door. I went to the

table where the blacks were loosely huddled

and started to talk to one of them that I

knew, then I stopped. He was taking a shot.

Don't disturb him, I told myself. He shot ac-

curately, confidently and the ball went into

the pocket as if it were snapped there by an

invisible rubber-band. Then he made a semi-

circle around the table and bent low over the

green. All his thought went first into angles,

then his concentration shifted to that one spot

where he wanted to make wood hit wood. He

shot, missed, the ball banked awkwardly back

into the middle of the table, he cursed, then

looked up at me.

"Tey, Cliff." | said, "What's going on?

'Not much, not much." He said, adroitly

chalking his cue-stick. "What are you all doin'

tonight?"

"Getting drunk."

"Oh Yeah? that sounds good."

"Cliff," I said, lowering my voice in a way

that must have seemed comical to the other

blacks, '"'a friend and I were kind of looking

for some women and we just don't know

where to find any this late at night, you

know?"

"Yeah," he smiled slightly, and regarding

me with a nearly imperceptable con-

descention, said "I know what you mean. You

need some help?"

I nodded.

"Wait till I finish this game and I'1l take

you on down there."

"O.1K,, good. Thanks; Chik." With that |

went back over to the door and told Bob

what had just transpired. We sat on some

wooden chairs pushed against the battleship

grey walls.

"You're sure you don't want another beer?"

I asked Bob.

"Oh, no, no. I've had enough to drink."

Well, I certainly hadn't had enough. Enough

would make me gently pass out. I wish I was

at home now, I thought, sleeping in my bed.

All this is just too much. Wait a minute!

That's Doug-talk. I'm out here to find

something. It may not be pleasant but its

something that Doug will never see. What

does Doug know about the "sultry streets of

dark desire?" His blood is made of ink. There

is much to learn from these people, I thought,

looking around the pool-hall. I smiled, Kathy

would be aghast. I was about to tell Bob my

views on the subject when a loud stream of in-

vective startled me. Someone had just missed

a shot. I swilled enough to make my head

Swim.

"You ready to go now?" asked Cliff. He was

standing in front of me, tapping the side of his

leg with a barely subdued impatience.

"Yea, let's go."

The moon was out, nearly full, and it shone

quietly, resplendently over the deserted

streets. The darkened store-fronts gave

vacant witness as our three reflections slid

over the windows. In front of us were two

blinking yellow lights, meaning we had two

blocks to walk before we would be out of the

downtown area. All was quiet but for the low

buzz of an occasional neon light and the scuf-

fling of our shoes against the sidewalk.

Cliff walked on purposelessly, taking

naturally long steps in an unconcerned way,

where Bob, who was tall also, took meaningful

direct strides. I was slightly shorter than the

others so I had to walk faster than they to

11

keep up with them. I was on the building side

of the sidewalk and had to concentrate my at-

tention to keep from bumping into the cinder

block and brick walls of the stores.

We left the edge of town and walked into

an area where there were no street lights or

neon signs. The sidewalk was narrow here

and cracked. At places the grass had grown

through the cement enough almost to trip me.

We were in a poorer section of town, one that

I was unfamiliar with, and evidently one that

was mainly populated by blacks, as a car

would pass us, now and then, with an afroed

head in the drivers window.

We passed a church, with it's grass-cracked

pediments, and in the shadows it looked as if

the roof were sagging. For a second I

imagined sweaty, round, black faces with

mouths full of white teeth singing un-

controlled and effusory praises to Jesus, per-

spiration trickling down their necks, slightly

dampening the collars of Sunday night pink

dresses. A breeze moved through the trees,

and high up, the leaves chatted oblivious to

us. We passed a darkened service-station

guarded by two staunch sentinel gas-pumps.

It seemed extremely dark. I didn't know

where we were, but I felt as if I had been

taken too far. I felt as if I had always been

taken too far and would never be able to know

why.

'Hey, Cliff, how much farther are we

going?"

"Not dar. Not far."

We turned onto a street that was bordered

on either side by closely spaced older houses.

There was room between each house only for

its gravel driveway. It wasn't the worst neigh-

borhood that I had seen. Probably, long ago,

this was once a white neighborhood. We

passed a house, nearly invisible in the watery

darkness, with a delicate wood arbor in the

front yard being choked and smothered by

thick, viney weeds.

The houses were without exception unlit, as

though the tenants had gone to bed long ago.

The feeling that many people were sleeping

overwhelmed me, and somehow the breezes

rushing through the trees made the houses all

the quieter and less approachable. We stopped

in front of one of the houses. It was com-

pletely dark. It was the kind of house that one

sees in lower class sections around any small,

southern town. There were steps leading up

from the sidewalk to a porch that ran the

length of the front of the house. The porch

had a wooden floor and a porch-swing hanging

on one side.

"This ts tt. Ulllt Said.

'But it doesn't look like anybody is up." I

looked at the house.

"You think they goin' to wait up all night

for customers?"

I didn't say anything.

We walked up onto the porch. The sound of

our feet on wood seemed terribly loud. A dog

began to bark several houses down. Cliff

knocked on the door. No answer. He knocked

again, more loudly, and we waited.

'"Nobody's at home." I panted, "let's get out

of here." I looked at Bob. He was staring

down at the paint-needy floor of the porch and

didn't utter a word.

"Don't worry," said Cliff, "theyre coming'."

The door opened slightly and from the

crack I could barely discern a dark face. A

whisper of nightgown floated out onto the air.

"Hey, baby," said Cliff, "What you all doin'

tonight?"

"Yaw'l'l want in?" asked a tired voice.

"Yes, maam, we sure do." answered Cliff.

The door closed and through a front win-

dow we could see the soft light of a lamp

shine through a curtain out onto the lawn.

The woman came back to the door and let us

in. She was a black woman, wearing a full-

length yellow sleeping gown. The living room

was like any other, with a small television set

in one corner and pictures of people in

graduation attire and wedding-gowns ador-

ning each surface. There was a mirror sitting

above a bricked-in fire-place where my own

face hovered in my disbelief.

There was a smell of worn carpet and dusty

curtains all through the room.

"They's only two of us here." said the thir-

ty-ish woman. "One of yal's goin' to have to

wait." Bob sat down on the old couch.

'My stomach is bothering me." he said to

Cliff and me, "Guess I've had a little too

much.

The woman led me down a short hallway

and stopped in front of a closed door.

'"She's in there. You just wake her up and

tell her what you want."

'But, but she's asleep?"

"Yea, you just go on in and tell her what

you want." And she walked back down the

hall, pulling her gown tightly around her.

I stood in front of the closed door. Oh, God,

I couldn't. No, I just couldn't. I grabbed the

cold doorknob, turned it, and opened the door

as quietly as possible. With the little bit of

light from the lamp down the hall I could

make out a dark form sleeping on the bed.

The room was soft with sleep. I walked in and

closed the door behind me. The moon was

shining grey through the window. And I could

hear breathing. The room was softly alive

with her breathing. This was too much. I just

couldn't do it.

I walked over to the side of the bed. The

girl smelled sweetly of lilac. She was sleeping

soundly with her mouth slightly open. A tiny

trickle of saliva glinted on her cheek and ran

down into a moist spot on the pillow. I put my

hand lightly on her arm. Her eyes opened sud-

denly, then closed again with a force, then

opened again and looked at me as if I were a

naughty child, or an unpleasant responsibility.

"That woman,' I said, "She told me to come

in here and... 1 shuv up.

The girl rose in the bed, swinging her feet

to the floor.

"O.K." she said,, and motioned me to a

chair.

I sat down in the chair and she began to

take off my shoes.

"What's your name, boy?"

"Jess." She was younger than me.

I looked out the window where the

moonlight was a steady silver, oh sweet moon,

beautiful, calm, holy moon. The girl reached

for my belt and all questions were over-

whelmed, guilt, for the moment, was deluged

in sensation.

Afterwards I put my clothes on and placed

her money on the beareau. I looked at her as

if to say something, but she whispered, "You

get gone now, O.K.?" A glove of moonlight lay

on her shoulder. I left quickly.

I walked blindly through the hallway and

den, crying as I hadn't since I was a child. Bob

was gone. I went out the door and started

towards town going home. Shame came down

over my face in hot washes. A little way down

the street I saw Bob walking. When he heard

my foot-steps he stopped and waited for me.

"I decided that I'd just forget it." he said.

"How was it?"

I loathed him. "You go to hell," I screamed,

"You go to hell you son of a bitch." and I

walked away nearly choking with shame.

A few days afterwards I went to see Doug.

He and I are working together on a book now,

working pretty hard, too. I think Kathy is

going to do the illustrations.

12

Scns REET POT A TTT PE = rae siiiamameeainiammnemmmans aaa - ; A eS LS SS nN cee nEneeNENS :7 aS RSTRNT UREN EERE eRTaEA a ARRAS ORE .

. y : i Gutiad vee Pee Addn OMS EDR Cre oer Fe ey roe eRe eT ener TNC al aa a ' sda nic asad Nan i i Nee gee AE eae ORES MON erate See CeO eRe eS Saas Aes ees sid se cS i delle DUA A SE Sank Cea eR ego stad 7 7

a por RARE '

i

fy

L

eH Cpe le tes

mes es parks gi

Pee ee ae

B Laat irra

arr

=

a

|

|

Listen:

Julie Andrews came into my room last

night. She was wearing some faded jeans

and an old peasant blouse. She had peeked

through the door to see that I was alone

and had knocked twice, but I hadn't

heard.

Since my room is nothing but two beds,

a dresser and two desks, she lay down,

elbow bent to keep her sitting up, and

watched me quietly as I finished writing

and sat down next to her.

She is still very beautiful. Her hair is

that soft auburn of Fall and her skin is

clear, without a hint of wrinkles. I told

her that I had loved her as a child and had

thought that she was the most beautiful

woman in the world when she played

Mary Poppins.

She told me that they had made her

wear a padded bra for Mary Poppins.

Something about being more attractive to

the little kids. They were huge, she said,

cupping her two small hands together,

styrofoam, and hot as hell. She still had

them though, in a drawer somewhere.

She laughed when I spoke of my one

theatrical success in the third grade when

I played the Tin Woodman in "The Wizard

of Oz." I wore chains under my oak-tag

armor that I might clink when I walked. I

told her what a smash I was.

As we talked, reclining on the bed, I

asked, and she sang some songs for me,

very soitly, as if she were frightened or

far away. I could only hear the strains. I

wanted desperately to reach out and

stroke her hair. It seemed so soft, almost

shimmering in the one small light from my

desk.

So I did.

She looked at me a very long time as I

moved my hand from her head and asked

me if I, too, were tired.

Last night _

Julie Andrews doesn't make much noise

when she makes love. She holds you

tightly, whispers your name, and mewls

slightly at the end. She is a wonderful,

considerate, exciting lover. She keeps her

eyes closed all the time and sleeps curled

up, her hands, as if in prayer, pushed

under the pillow.

She left this morning, a little before my

ten o'clock class. I was up and about, but

very sleepy. I don't remember her kissing

me goodbye or leaving.

It wasn't until I came back from class,

while making the bed that I found this

small note near the pillow where we'd

been sleeping.

mary poppins loves the tin woodman...

There was a small drawing of an

umbrella and an oil can in the lower left

hand corner. I folded the note and put it

with the books I'd never read.

Someday I would like to look out a

window and see a face so beautiful it

would force me to live.

Tomorrow will be too late.

I will write four notes. Each will start

differently, each will say something

different.

The first to begin, "Nothing is ever

truly serious..."

The second will begin, "Between the

fingertips and tongue lie the only true

answers..."

The third, "There is really no way toa

woman's heart..."

And the fourth and final note will be

the shortest. It will say goodbye and it

will start like this;

Listen:

Julie Andrews came into my room last

mich...

14

_ Dewey Hobson spent most of his younger

years overworking some rocky hill land he

ealled an apple farm. Now, he passes roughly

half of his work-day sitting at the warm end

of a discarded church pew, talking. He talks

to anyone who is willing to sit at the cold end

of the pew or in one of the ragged, rush- -

bottomed straight chairs he owns, and he

talks on any subject. Occasionally, he rises

from his end of the pew, the end nearest the

big oil heater, and ambles to an obsolete _

mechanical cash register, where he receives

compensation from a customer who has ,

removed goods from his shelves or pays off a

salesman who has placed fresh merchandise

neatly on his shelves. Sometimes, if he is en-

thusiastically animating a lengthy bit of local

legend, he keeps his seat and sends the buyer

or seller out the door with a snap of his wrist

and the words, "You can pay me next time,"

or "T'll pay you next time."

rwise unexceptional life. It was to sell _

alf of his no-profit apple farm to an adjoining

apple grower and invest the money in an

unused Woodmen of the World meeting hall;

which he painted, shelved, and stocked with

general merchandise. The emporium enjoys a

healthy profit whether he sweeps the floor or

not, so most of the day is spent in "come on

in's" and '"'see you later's" and whatever

comes to mind in between. - ,

There are several relics of leaner years

around Dewey' s place, and Dewey is always

willing to tell about their uniqueness or local

historical value. The sociable man has found

room enough around the walls to display the

first plow to break land in the valley, a circus

poster dated 1882, old medicine bottles with

directions for curing forgotten diseases, a con-

traption for coring and peeling apples that

Dewey claims his father invented, and a giant

La

an become mildly per-

2s for the intriguing

pair of peate ; aked, cowboy-style

children's boots. He puts it something like

this: "Uh, nope, uh, rather you didn't mess

with them old boots. Guess you couldn't hurt

them none, but I've always been scared they

might get gone out of here sometime or get

put around here where I couldn't find them

and get throwed out. Them boots belonged to

a real man, a real man. Fella name of Shorty

Briley, little bit of a fella, owned them boots.

Was wearing them just before he died. Yessir,

little bit of a fella, but a real man, Shorty. Got

eat alive by a bobcat one night right herein .

the valley. Had them boots on not ten minutes

before he died. Only trace of him we found.

'Course a bobcat ain't none too big, but they

something mean; mean, and this Shorty was

just a runt of a fella. Did you ever hear that

Slory avout Shorty? ... Didnt, huh?... Well

one night there come a big snowstorm. This

valley was sealed off tighter'n a nickel in an

old maid's handkerchief, and out of nowhere

come a bobcat as big as... big as... big as

that oil stove there. Tearing up people's

screens, trying to get in the house to drag off

children, killing farm animals; it was a terror.

So this big cat got tore open and bleeding

somehow. Near as we could figure, a mama

Black Bear must have swatted it to keep it

away from her cubs. So this big cat climbs a

Live Oak right out here beside my store;

going up in there to die. I got out of bed and

come on down here, and this little fella I was

telling you about name of Shorty Briley,

Ne...

Shorty Briley rolled over in the darkness.

He had put out the lamps at 9:00, his regular

bedtime during trapping season, but as the

fires burned down to gray ash and the cabin

grew cold, he lay sleepless; his eyes on the

window. He had thought there would be no

moon, that the night would be as black as a

bear's cave, and he was right, but the dense

fog that came down from Brookshire's Ridge,

the fog that hung up there almost every

night but dipped into the valley only one or

two nights a week, came as a surprise, a help-

ful surprise.

Somewhere in the valley, an animal was

wailing. On a clearer night, the shrill sounds

would have seemed nearer as they echoed

about the hollow, and the screeching would

have shaken the bed and penetrated the soul

of every apple farmer, mill worker, housewife,

and school child in the valley; for these sounds,

these laments from hell, were those of a bob-

cat, the nearest relative of the devil these hill

people could name. Although the sounds were

muffled by the absorbent fog on this night,

they had a certain clarity that would keep a

valley man sleepless with awe.

Shorty knew the cry of a bobcat, and he

also knew the sound of Sheriff Tate's pickup

truck. Later than he had expected it to hap-

pen, he heard the two sounds blend together,

and he saw the truck-lights come misting

through the back room window. A minute or

19

so passed before the truck-door slammed. He

figured the sheriff must be driving slowly

because of the fog.

The engine continued its whine as Shorty

waited for the knock on the oak-plank door.

When it came, it was rough and demanding,

as though the sheriff were using the butt of

his .38 instead of his fist.

Shorty waited until the sheriff knocked a

second time, then he laid back the three

frayed patchwork quilts and lowered his feet

slowly to the floor. It was colder than he

thought it would be. Unhurried by the poun-

ding, he felt around on the chest of drawers

for the matches. The clock in the front room

struck 11:30. He lit the lamp.

As the small man entered the other room of

the rented, two-room shack, the sheriff was

knocking a third time. "Uuuh, uuh," Shorty

bellowed and bent to pick up his boots.

"Shorty, it's Sheriff Tate," the man outside

called back.

"Uuuh," Shorty answered, while pulling the

weather-faded boots onto his small feet. He

knew who it was. He knew who always came

to get him when there was some excitement,

but he wondered why the fat sheriff had

waited so long.

The man outside said no more until Shorty

opened the cumbersome door and held the

lamp out from his chest. "It's Sheriff Tate,"

repeated the fat giant of a man. I thought I

better come out here and get you up. You

been hearin' 'at bobcat squillin over to Ben

Macon's, ain't you?"

Shorty used his free hand to rub his face, as

though he had been asleep for hours. ' 'Eah,"

he answered.

"Sounds like a big one, Shorty. Been scared

up a tree; maybe hurt someways. Anyways,

he's treed. Figured you'd want to be there to

watch us, if we get a shot at him."

Leaving the door three or four feet ajar, an

invitation to the sheriff to come in if he liked,

the small man turned back into the cabin. The

fat man chose to return to the warmth of his

truck-cab. He preferred the odor of a newly lit

cagar and six-month-old plastic upholstery to

that of the musty cabin.

Shorty set the lamp on the mantel. He but-

toned the top three buttons of the long-limbed

underwear suit he wore to bed, put ona

heavy green cotton shirt, and worked his

boots through the legs of small faded

coveralls. He was the only man in the valley

who bought boy's-sized coveralls at Dewey

Hobson's Store, and the men who sat around

the place and told stories usually made jokes

about it when he came in for a new pair.

As the sheriff sounded two long blasts of

the truck's horn the small man put his father's

railroad watch in an upper pocket of the

coveralls. He counted the $820.00 he had

saved from trapping so far that season, cram-

med the billfold into a front thigh pocket; held

a tintype photograph of two of his great-

grandparents up to the light for a moment,

then slid it into the other thigh pocket; wrap-

ped himself in a tattered wool overcoat that

hung nearly to the floor, took a handful of

matches from a box above the black stove,

blew out the lamp, and found his way to the

door by the truck's lights.

As soon as the small man seated himself in

the truck, the fat man asked, '""'How come 'at

old dog of yours ain't howling tonight?

Thought she always got stirred up when there

was a bobcat around."

Shorty took a long look in the direction of

the woodshed and answered bitterly, "Pret-

tygirl run off."

The sheriff jammed the truck in reverse

and dug up the yard as the turned around.

"Hell, 'at old dog never was any good

anyway, the big man said. "So she run off,

huh? Well you better off without her. Get you

a good coon dog now. 'At young bitch of mine

going to throw pups soon. I'll sell you one of

them. A good coon dog got to come out of a

good bitch, if it's going to be any good." The

small man showed no sign of hearing the

words.

As the two men bounced with the holes and

bumps of the old asphalt road, the sheriff

thought of another question. "You going to go

over there with me Sunday to Kileboro to

watch 'em blow up 'at old Chase Hotel?" he

asked.

Shorty hesitated so long that the fat man

looked over at him for an answer. Finally, he

said, " Fah, | reckon so, ui its all right."

The big man looked back at the road and

said, "Ought to really be something to see.

They talk like it'll be heard all over the coun-

ty' miles and miles." He let out a short

mocking laugh, as he continued with, "But I

don't want you to get over there now and

start looking for some little old boomer gal

and go following her off home. If I take you

off, I got to bring you back. Don't want people

saying I got you in trouble." The fat face held

a bold smile as it turned toward Shorty again.

The small man showed no sign of hearing the

words.

Near the sight of the high-pitched cries,

several cars and trucks were parked along the

roadside. Most of them had the two left

wheels on the pavement, making the narrow

road look more like a path. The sheriff parked

his truck in the middle of the pavement,

beside the other vehicles. Now if a car were

to come along at this hour of the night, the

driver would know the sheriff of Kile County

was on important business.

The fat man slammed his door with

authority to announce his arrival. For the

second time that night, he reached under a

canvas in the truck-bed and removed three

large, battery-powered lights and three 12

gauge shotguns. He had not trusted the other

men to watch after these while he went for

Shorty. "County property, boys," he had said.

As the two men approached the crowd of

onlookers, factory men mostly, employees of

the new textile plant that came to Kileboro,

ten miles west, and brought work and

development to the area, the spectators

turned their flashlights and lanterns toward

Shorty and the enormous sheriff. The dogs

stopped their whooping and cocked their ears

to identify the newcomers.

"Don't shoot now, boys. It's me and old

Shorty," the big man called, as he shined a

more powertul light back through the fog and

into their faces. "Any of y'all had a shot at

him yet?" he asked, knowing he would have

heard a shot anywhere in the valley had there

been one.

"Naw," they all answered in unison, and one

man added, "Not yet."

"We going to kill 'at rascal, if we got to

send Shorty running up 'at tree with a sawed

off 12 gauge," joked the sheriff, as he and the

short man neared the group.

The fat man's words brought a roar of

laughter and a couple of "hell yeah" 's from

the crowd, and one young man, a sportily-

dressed example, of the new prosperity coming

to the valley, slapped shorty on the back as a

teasing gesture.

Shorty looked around him at the faces

illuminated by the battery, oil, and gas-

powered lights. Most of them were there, he

figured. Eddie Kile was there, and Melvin

Strayhorn, C.D. Spills, Jason Spills, and Er-

20

nest Tate (the sheriff's fat brother) were

there. Most of them were there; the teasers;

''fun-pokers" and good-time boys who kept

him at Dewey Hobson's Store until 10:00 one

night three weeks ago. Oh, they did not keep

him there by force, but they teased him about

women, his small stature, his tree-climbing

abilities, and never having too much to say,

and a man does not walk away when he is

being teased; not a hill man anyway. That

would be like not going to your traps one day,

just because it was raining or snowing.

In one of his more talkative moments, Shor-

ty put it this way: "It don't matter if a man

gets joked at and teased at' just some dern

fools running their mouths. As long as a man's

got something to be proud of, something like

the best damn hunting dog in an entire coun-

ty, or being real good at his work, make no

difference what they work be, he don't need

to pay no attention to what others say or

think. You take a man being small; now if a

man was a trapper and had to walk ten, fil-

teen mile a day, uphill and down, that man

don't need to be no tall, heavy man; be huf-

fing till bedtime. And as for skinning up a

tree, well what man wouldn't want to climb a

tree, if he was able. And as for being quiet,

well if the other end of being quiet is telling

all them big tales and letting everybody know

what a dern fool you are, well then quiet is

best. At least a man that's being quiet is

using his brains some of the time."

Shorty believed a man could "take most

anything, as long as he had something to be

proud of', but when he came home that night,

that night they "kept" him too long at

Dewey's, and found his dog dead, he felt a

change in his world.

In the yard, under a bright moon, he had

sat beside the dead animal, the "best damn

coon dog in Kile County", and he wished the

bobcat had chewed him instead of his friend. At

least he would have had sense enough to run

away and probably would have come out alive.

Sitting there, he blamed himself and not the

cat. He should not have left the carcasses of

muskrats hanging on the side of the house

~where he skinned them. He should have come

home before dark. He should have locked

Prettygirl in the woodshed at dusk, as he

usually did. And he had said to himself,

"Damn old dog never could leave a bobcat

alone; always smelling around where one had

been, like it was an overgrowed coon."

He had buried the dog that night, and he

o1

had decided not to tell anyone about his loss,

his punishment for hanging around Dewey's

till all hours. He had made up his mind about

something else too; he had decided his world

no longer a fitting place to live and the time

had come for him to do something about it.

Shorty sat for awhile on the cold ground, on

the padding of brown crackling leaves, and

waited to see if any more of them would come.

There was no hurry. When you leave for

good, you are gone a long time. He wanted all

of them to be witnesses, so that when the

story was told around Dewey's on cold nights

like this, there would be many versions and

all of them different. He could wait. One thing

a man who earns his money by trapping

learns is to wait.

While Shorty sat quietly, the dogs barked

themselves into hoarseness, and the bigger

men talked and laughed of other days. It was

time for tale swapping, time away from the

womenfolk, time to tell about other cats that

had enjoyed legend so long that they had

grown to the size of bears, time to tell about

what granddaddy told about, and time to

speculate as to the stories that would come, if

this cat sung his guts out till sunup and got

ripped open by a 12 guage shell."

Finally Shorty was ready. Will Huntley had

'showed up." He had been at Dewey's that

night. He was the one that said he bet Shorty

kept a woman in his cabin, but she was so

ugly he wouldn't let her out of the house.

Shorty was sorry Dewey wasn't there. Dewey

could stretch a story "all different ways."

The small man picked up one of the sheriff's

powerful lights and walked to the base of the

tree. He beamed it among the branches of the

tall White-Oak, but the fog held back the light

to a few yards. The other men stopped talking

to watch him.

After he figured he had studied the

situation over as well as any good valley man

would, Shorty stood in one spot and gazed in-

to the tree. He appeared to be absorbed in

thought.

"What you thinking 'bout doing, Shorty,"

one of the men asked, "going up in there after

'at hell-yun?"

There was no laughter; there was no fun, as

Shorty removed the small, but heavy, worn-

out boots. The other men gathered around

him reverently and tried to quiet their dogs.

They began half-hearted protests of what he

ae The cat's wail rose in both pitch Edits

- volume, as every nerve tuned itself for

the bounce... | oo

was about to do, but Shorty knew not a "man-

jack" among them would hold him back.

"Shorty, you ain't going up 'at tree now, are

you?" asked the sheriff, having sense enough

to realize a man would not take off his boots

to wiggle his toes in the cold dead leaves.

"Shorty, I ain't going to let you go up 'at tree

now, he continued. "Shorty ... Shorty," the

fat man called, as though his voice were

having difficulty penetrating the fog. "Shorty,

I ain't going to let you do 'at."

The small man knew how they really felt,

that not a one of them would trade this new

excitement, not even for his father's railroad

watch. He knew what the sheriff's words

were; just talk, so that if anything happened

to him up there, the bloated hog could say a

thousand times or more, "I tried to stop him. I

tried ever way in the world."

Shorty turned to Jason spills. "Give me 'at

knife in your belt," he said, and Jason looked

down at his stomach, as the small man pulled

the knife from inside the belt and tore away

the leather sheath. Shorty put the blade bet-

ween his teeth.

"Now you ain't going up there, Shorty,"

said the sheriff one more time to be sure

everyone there would have no doubt he was

doing his duty.

Shorty dug his fingers into the rough bark

and brought his legs up to a frog position. His

toes gripped almost as strongly as his small

fingers. He paused for a moment and took in

some deep breaths that were exhaled as soft

erunts, then he began to scale the White-Oak

with the ferocity and power of the animal he

was going after.

When he reached the first limb, he sat on it,

took the blade from between his teeth, and

called in a loud whisper to the men below,

"Turn out t'em lights." The flashlights and

Janterns popped out one by one, like a string

of Christmas lights after one has failed. "Dern

fools,' Shorty said under his breath. He put

the blade back in his teeth and reached for

the next limb. He felt for each branch at just

the right spot, as though he knew where the

next rung in the random ladder would be. The

ground below was quiet, as each man kept a

firm grip on his dog.

Finally, his hand rested on it, the source of

the unending cries. He rubbed the scaly bark

sides of the homemade cage almost as though

he wished to comfort the spotted, reddish-

oe

brown wild thing inside. He made certain,

however, that his hand did not come too near

the steel-wire door in the end. Slowly, he un-

tied the brown hemp rope that secured the

cage to a limb. There was no hurry. If they

wanted the best story of their lives, they

could wait for it.

When the rope was free, he tugged on it to

make certain it was still firmly attached at the

other end. He was a small man, but never-

theless, he wanted it affirmed that the rope

would hold his weight. He was satisfied.

Sitting on the same limb as the cage, Shor-

ty felt for the handle attached to the butt end

of the hollow-log box. He gripped it firmly.

His right hand twisted a short piece of broom

stick that was serving to lock the sliding door

in position.

As he tilted the cage over the limb, he felt

the weight of the animal shift wholely to the

front end. The cage slid a few inches, but his

left arm held it in position. He bent his head

down as near as he dare come to the wire

door and whispered, "Here you go, you red

devil." His right hand gripped a knob on the

top of the door frame. The hand was cold and

the muscles were tight, and when a single

claw curled through a hole in the wire and en-

tered his flesh, the pain was hardly more than

a thorn scratch. As though it were a reflex

from the scratch, his hand yanked the door up

in one smooth motion. Foot after foot of

screaming cat poured from a box too small to

hold it.

The cat's wail rose in both pitch and

volume, as every nerve tuned itself for the

bounce; when it hit, the bones of its legs

tried to tear through the heavy fat layer of its

back, yet its belly only lightly brushed the

ground. No man could hold a dog, and the

bounce was hardly over before the furious cat

cooled its head, decided not to take a stand

against the odds, and vanished as though it

had changed itself into one of the dogs around

it,

Shorty opened his small eyes wide and did

not blink. He wanted at least one faint image

to carry with him, but all he would have to

remember this night by were the sounds.

23

There was one flash of light, but it gave no

image, no picture of the action. It came

seconds after he pulled up to the door, about

the time the cat hit. A single powerful light

came on and was pitched skyward with the

first human cry, but it hit the ground far

away and flashed out. Shorty thought he

knew who was the first to cry out.

Hurriedly, he pulled the cage up to his side,

threw the knife into it, and shoved the door

into position. He lifted the cage by a handle

attached to the top, then grasped the rope

with all the power of his right arm. He

checked the tension again, aimed himself for a

second or two, then swung blindly into the

black air amid the howls of both dogs and men.

He pulled his short legs up to his chest to

correct any error in calculation, and as the

rope swung back the second time, he dropped

his feet onto solid earth. He was standing un-

der a huge Sycamore tree, a good distance

from the disturbance beneath the White-Oak.

Feeling safer now, he paused and listened

again. He knew the cat would be gone, but he

also knew the boys were not as familiar with

the ways of wild things as he, and he smiled

as he heard the "gran' time" they were

having, feeling dogs or other men brush

around their legs, sensations each of them

could later claim for certain was the creature

from hell.

Satisfied, he dropped the cage, felt around

the trunk of the Sycamore until he found a

thin rope tied there, and untied it. He pulled,

jerked, and put his weight on it, until

somewhere up in the Sycamore, the knot in

the other rope, the thick hemp rope, gave

way. The two ropes came down around him.

He groped around the base of the Sycamore

again; this time until his hands touched the

cold leather of a brand new pair of boots. He

worked them on, rolled up his ropes, picked

up his cage, and as lights began appearing un-

der the massive White-Oak and the men

began calling his name, the trapper was off in-

to the woods, the territory he knew so well.

There was only one thing he regreted, as he

found his way in the darkness; he wished

Dewey Hobson had been there. Dewey could

stretch a story "all different ways."

suicide and sylvia plath

we suffer daylight and

summer green,

a smug knowledge

that darkness hides

a cool and welcome release.

the day, a river of light

that blinds,

and trailing like a tear

the sun stumbles,

is guided like a witless child

to the crib of china.

gas last.

deeper breath

and tepid rushes.

death: welcome

the wild western winds.

our dreams once

hissed to us

as snakes.

24

26

en ae

you are a gentle man

of sorts

1 plotted the points of your past

in a series of post cards

pointillism

microdot

needlepoint

breaking point

black star

white orifice

1remember this

from an old tune

that plays tome

in the rhythym of air conditioning

late at night

in a bourgeois neighborhood

with the pages turning

sweat dripping

heart pumping--

breaking

28

PO seStietcenurectredtndntetetetirs

AEP SETHE pene tral AEE AETMETPLEPLEPSETTSETL

Pay 4

ee

Jeff's fingers trembled slightly as he turned

the key to Ellen's apartment. He had entered

this way so many times before, but this time

he felt like an intruder. With a nervous glance

over his shoulder, he pushed the door open

and felt inside for the light switch.

Everything looked the same as he had

remembered, and yet it somehow echoed of

emptiness. "Ellen!" Jeff yelled, surveying the

rooms. "Ellen, are you here?"

He called out again, knowing that he would

get no answer. Ellen was gone. She had left

about four days ago without giving him even

the slightest notice. That wasn't like Ellen at

all, Jeff had kept telling himself. Something

must have gone wrong, but what? Jeff racked

his brain for clues, but his mind was blank.

He had been calling day and night for the

past several days, hoping that during one of

his attempts, she would pick up the receiver

and explain away his fears with one of her

soft, reassuring laughs. Jeff had let the phone

ring and ring, but his efforts were wasted.

There was no Ellen to comfort him.

"TI should have come sooner," Jeff muttered

to himself, angry and perplexed. He glared

around the living room and noticed with a lit-

tle surprise that half-filled glasses still stood

on the coffee table, that the couch pillows

were still lying on the floor, that the ashtrays

were full of stale cigar and cigarette butts.

Nothing had changed since he had left late

Sunday night.

30

"That's not like her," Jeff thought as he

became increasingly aware of the room's

disorder. "She would never leave with this

place in such a mess." He walked quickly over

to the bedroom and looked in.

From the appearance of the crumpled and

entangled sheets, it looked as if someone had

just crawled out from a night of restless sleep.

Jeff's eye took in the half-opened drawers, the

stocking strewn along the carpet, and the spilt

container of bath powder. Kneeling down in-

stinctively, Jeff began to scrape up what he

could. The carpet being a thick shag, his ef-

forts met with little success. "Oh, what the

hell,' he muttered, wiping his hands on his

trousers.

He rose and noticed something very

strange. Jeff walked over to her vanity and

stood in wonder. He looked into the circular

mirror, but only a cracked, shattered image

stared back.

"Now what do you suppose made her do a

thing like that?" He ran his fingers over the

broken glass. He stared and pondered, won-

dering which was the more fragmented -- his

thoughts or the reflection in the mirror.

The phone rang. Jeff jumped and stumbled

in excitement as he ran to the bedstand.

"Ellen!', he shouted into the receiver. '"'Where

have you been? I've been trying to get hold of

you for the past..."

The receiver clicked in his ear. "Ellen!" he

shouted again. The dial tone buzzed harshly.

He slammed the phone down with disgust,

and for the first time felt a twinge of true

fear.

Where was she? This time the question sur-

faced a little more urgently. Jeff thrust his

hand in his pockets and paced back and forth

across the room. Memories of her flowing

blonde hair, her full-moon eyes, her low, soft

laugh violently rushed back and haunted him.

He winced and walked more determinedly

through her four-room apartment. The

miniature grandfather clock marked off thirty

minute intervals, but Jeff was oblivious. He

paced and stalked, feeling out the limits of his

memory and imagination.

Jeff found himself standing in front of her

bookcase. The shelves were filled and over-

flowing with novels, short story anthologies,

and volumes of poetry. Jeff recalled how she

would recline and hide behind those paper-

back covers while he would pore over those

accounts from the office. She would curl up

and read for hours, never moving more than

the fingers necessary to flip through the

3]

pages. He looked now over his shoulder to her

den recliner, half-expecting to see her slight

figure snuggled into the chair's deep cushions.

Letting out a troubled sigh, he turned and

his eye fell on a small leatherbound book

laying on her desk. Jeff picked up the little

volume and noticed that a few pieces of

notebook paper were folded up and stuffed in-

to the middle of the book. The Poems of

Wilham Blake, Jeff read half-aloud as he

examined the book. With some curiosity he

opened the book to the pages harboring the

folded sheets of paper. A short, illustrated

poem caught his attention and he hurriedly

scanned the first stanza's rhythmic lines: