[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

fae fale if f a oe T A | I E

MT iS) ic : ai as > mnt ~ ii ron ie ¥

a4: =

0

| i i

vi

i &

A

TF : Vi > all

m2" |e os

La

:

= -

="].

|

|

ae bg iy Dy

a. le NY 4

x

\ : fhe &

. \ : ce | p if o I a MG

. or il

eee

: « Ch, % im

Hh

wD ¢ Y

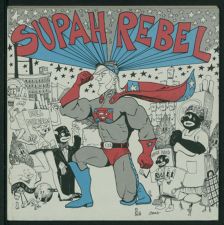

Sura Reper S97] H¥KHK The REBEL 13 A STUDENT {HoT chaT)

; ANNEX for DOSTALLY AT P0.Box 24%6, GREENVILLE, N.C. 27434) CoPYPiEHT |

Se eT

PUBLICAT/ON OF EAST CAROLIVA UNIVERS/TY. IT LivéS AT 2/5 WRIGHT

| 1971, ECU STUDENT GOVERNMENT ASSOC/ATION. THAT'S ALL. 3

nee atat

~e"e'

ie

Editorial

The Sacrifice by Nicola Glover

Beach Scene by Edwin Page Shaw

Doc Watson, Interviewed

Untitled by Regina Kear

The Flowerets by Nicola Glover

Untitled by Anita Brehm

Out of the Garden by Regina Kear

Untitled by Anita Brehm

Ferris Wheel by Robert McDowell

The Music Lesson by Thomas Jackson

Untitled by Regina Kear

Untitled by Edwin Page Shaw

Untitled by Jackie Sweeney

Against the Window by Maxim Tabory

The Wino by Regina Kear

Auction by Sharon Shaw

DELTA PHI DELTA

Annual Spring Art Show

The Meaningfulness of Art, What is

by J. Bradford McCorison

Of Silence and Slow Time

by Sharon Shaw

Untitled by David Lawson

After Grant Wood by David Lawson

In a Cabin at NagTs Head While the

Wind Assaulted by David Lawson

Mesa Verde by Frederick Sorenson

Intersection by Lawrence Cline

Deserted Barn by Thomas Jackson

A Geopolitical Revelation or, A

Sense of History by D. Lawson

Untitled by Jackie Sweeney

A ChildTs Garden of Grass, Wm. R. Day

Islands in the Stream, Fred Whittet

Be Not Content, William R. Day

Weep Not Child, Janice G. Hardison

The Dick Gibson Show, Dr. John Firth

None of the materials herein may be used or reproduced in any manner without

the written permission of THE REBEL.

\

Consider what has happened to art since the late sixties, when greed finally

outgrew itself and brought to a close the period of American life which his-

torians will conveniently pigeon-hole as ~post-war prosperity.T For the last

decade, growing numbers of people have been more or less united by a mutual

sense of intuitive existence. This general view of life has necessarily come

into conflict with systems based on the pragmatism of a society which is, to a

large degree, technologically oriented. It is impossible to say for certain, but

it would appear that the resulting political and social polarization was initiated

by an earlier aesthetic polarization. If this is the case, then the artist is indeed

on the spot.

Sometime between the '68 presidential election and the night Joe Frazier

took out Mohammed Ali, it became apparent that the old symbols would never

again be the same. The artist, who was not quite sure of his position to begin

with, was told to put up or shut up. Involvement took on new meaning and

propaganda became a poetic device. What once was regarded merely as

taste became a spiritual dichotomy which by its very nature could only be

defined in terms of one side or another.

So what? Nothing really, except that todayTs artists feel the need to com-

municate something in terms of final statement which will be considered

orelevant.? This conscious attempt to be orelevant? reflects itself in a style,

which at its best is painfully limited. This approach to art leads to a ochoosing

up sides? type of farce which either forces the artist to sell out completely or

intellectualize himself out of existence. Even if he can avoid these pitfalls, he

will be unable to communicate within a system which places only token value

on the intelligence of its leaders.

An upheaval which began because of aesthetic differences cannot be

resolved in the halls of Congress. Nor can the immediacy of art be explained

in factual relationships. The artist must maintain the honesty of his craft or

he will be blurred by his own attempts at over-extension. Whatever the

individual artist may be dealing with, he must maintain his personal honesty

without neglecting his artistic suppositions. But not until brickmasons and

abstract expressionists can understand what they both are up to individually

will art attain its proper place. To quote from an anonymous poet of the Old

School, oMany are called, but damn few are chosen.?

THE SACRIFICE

Frigid concrete

grates on the eyes of fever;

muslin, starched with virginity,

smears, and raws the flesh;

magnets of gray steel

brace the clinging fists.

The skin, taut

with bruised chicken scratches,

bumps and grinds

to life.

The pain swells, tightly,

into a consuming knot,

regressing slowly

to exhaustion.

Wailing Screams

smother the mind with terror,

sterile hands

soothe the trembling arms,

fleeting pin holes

abort the ball bearing rhythm,

stirrups

seize the legs,

leather

straps the body.

The mask!

Desperately sucked

Relief . . . one life away.

Nicola Glover

beach scene (1)

she sits

in the autumn of pregnancy

cumbersome in sun and sand

watching his athletic

ball-less forays from surf

to her bloated presence,

commanded as tribute

to his manhood.

beach scene (2)

he stands on boardwalk step

slender gulls of perfume gliding

left wrist draped by towel

right by silver chain

identifying more

than name and address

Surveying muscular bodies

calculating beside which

might be the perfect spot

to be browned

in the sun.

Edwin Page Shaw

doc watson

OCTOBER, 1970

_ Doc Watson lives in Deep Gap, North Caro-

lina. And he picks a guitar sweeter than a

nightingaleTs song. Doc picks and sings what

he calls otraditional American music,? which

is the offspring of bluegrass, country and west-

?,?rn, mountain music and Doc Watson. He has

Mastered the expression of a form of music

which sprang from the mountain people, who

were isolated from the trend of Western art.

The life of the mountain people is a gentle,

yet far-from-simple way of life. What can we,

who daily are affected by the unrelenting struc-

ture of the city, learn from a man who could

hold city audiences in his hand but prefers to

live on the side of a North Carolina mountain

In a house which he wired himself for elec-

tricity? (Doc has been blind since birth.)

What changes do you think have come about in

folk music since the early sixties?

For my love of old time music, the music itself

hasnTt changed. What people like to hear in concerts

has changed a little bit, but on the other hand,

you'll find groups all over the country that still like

the old traditional music"the oold timey? sound,

if you want to put it that way. When | play music

| have to be myself. ITm not just given to playing

the flat old time country sound; | have to put some

of my own notions into music. At our concerts now

we play quite a bit of bluegrass.

Some of the scholastic folklorists believe that

old time music as we know it now, (the type of music

that you play"real country music ) in the next 20

or 30 years will again be oral tradition music,

played for personal entertainment only. Do you feel

that this will happen?

| donTt know. | know the interest in bluegrass

music, which has been including sets by Merle and

myself at lots of the bluegrass festivals during the

summer, is growing. | donTt know how long that

will last, if the upturn will hold its own, or if it

will drop off again. If we had a big upsurge in

popularity, weTd say owell, this ainTt never gonna

quitT. ItTs anybodyTs guess, in my opinion. A lot of

people | have talked to say it will never die out,

it will have upswings and downswings. Since itTs

been brought back people have found a true and

honest interest in the music because itTs not some-

thing complicated, not something you have to sweat

over and learn how to read. If you can hear and

you're talented a little bit in music, then you can

learn it by ear. | doubt if it will ever die completely.

lTve noticed at the fiddlersT conventions at Union

Grove, Galax, Reidsville, and Beanblossom that many

people at these festivals and conventions are the

young people 25 and under. A lot of college students

seem to have found something in this type of music

which they feel they can identify with. It hadnTt been

art of their lives until being introduced to it"

ironically"when attending college.

ThatTs exactly what | was trying to get at. The

music has something to say to most people because

itTs down to earth"itTs not complicated. You know,

the modern rock sound (ITm going to say this al-

12

though | might get crucified for it) has excitement

for the young, as it would have had for me when |

was MerleTs age (21 ). But it really hasnTt much to

offer musically. ItTs just an exciting beat, a sound,

and it really doesnTt live in your mind very long.

You go on to the next fad or slight change in the

loud guitars behind the beat. And when it goes, and

it will, what are these folklorists going to lean back

on as real music? WhatTs gonna replace the good

sound of country music?

Doc, youTve played all over the country. If you

can, ITd like for you to tell us why you chose to

stay here in Deep Gap. What keeps you here when

you could be in other places of more success in

material means?

I'd like to ask you a question. YouTre young, but

maybe you could tell me why. Was there ever any-

thing that wasnTt worth much to anybody else, to

the average worldly person, the city man? Was there

ever anything in your life that there was an un-

bounding love for, that you couldnTt quite explain,

but it was there? My family and my native country,

the part of the country where | grew up, mean more

to me than anything in the world. | figured | could

do a limited number of engagements in music and

try to get enough publicity to keep myself going

for a reasonable number of years and still stay here

because | love this place and | love my family and

| donTt want to go on the road solid. | want to earn

a good enough living so | can lay a few dollars

back and some of these days build me a good warm

house, and things like that. But as to want to pile

up umpteen thousand dollars in the bank, thatTs

for the birds. A man might strive real hard and

pinch pennies and make his wife wear patched

jeans and save, but what good would it be? I'll spend

a little along and earn a little along and try to keep

things going here and keep me a little hospitaliza-

tion if | get sick.

For a long time, simply because of the geo-

graphical location of your home, the mountain

people were more or less isolated. Do you think

because of this isolation, the mountain people have

developed this closeness and a feeling for the land

that is not found so strong anywhere else?

| really donTt know why | love the mountains the

way | do. The mountains and no other part of the

country have that feel to me. If a man is raised

in the country, he puts down more roots. Maybe

it's the closeness to nature. | donTt know why we

love the country the way we do. But | can safely

say this, most of the people that youTll find up in

here like this country and wouldnTt swap it for no

where.

Merle, youTre a different generation and youTre

still here. Evidently you feel the same way about

the mountains that your father does and you were

born more or less in the age of technology, after

the 2nd World War. How do you feel about your

home?

Well, | just wouldnTt leave. | donTt think | was

born exactly in the age of technology, maybe in the

age but not in the middle of it. (Doc: What heTs

trying to get at is he was born in the country just

like | was.) In the same place in fact, | wouldnTt

give that for anything, especially the city.

Doc, you play blues as well as any white man

ITve ever listened to, but although you do blues so

well thereTs a lightness about your music. When

you think of the typical Doc Watson song, you think

~of a driving flat picking thing like oNothing to it?

or some of the old mountain songs you do such as

oSing Song Kitty? or oFroggie Went a-Courting?.

ThereTs a spirit about the songs, a happiness that

communicates through the record. How do you feel

about that?

Well, | play the way | feel. ThatTs the best way

| can answer that. If a man is singing about a fast

train, thereTs no use dragging it along.

At one of the concerts you led a standing ova-

tion for Elizabeth Cotton. Was there a time during

your development that you sought to emulate that

type of playing or did it come from somebody else?

Not really, it must have come from hearing John

Hurt playing. If my playing has been influenced by

anyone, it was John Hurt because | didnTt hear

Elizabeth Cotton until the mid-sixties.

One of the Kingston TrioTs biggest hits was oTom

Dooley?. | noticed their version was quite a bit

different from yours. Would you relate to us the true

story?

Tom Dooley was born before the Civil War started.

When they were conscripting men into the army

he was about 14 years old. He was one of those

boys that grows up right quick and passed off as

an 18 year old and got into the army. They say

during the period from the time he was 14 until

he was 20 he lived half a lifetime in experience.

Tom dated Laura Foster and Anne Melton and so

did Mr. Grayson, the sheriff who pressed the thing

against him. The Kingstons say it was a triangle,

but actually it was a quadrangle affair, with two

fellows and two gals. All the accounts that are

handed down affirmed that Anne Melton murdered

Laura Foster. Tom Dooley helped cover up the

the crime. He figured if he tried to put the crime

off on who should have took the credit for it, people

would just laugh him off anyway because Grayson

turned everybody against Tom Dooley. Dooley didnTt

try to blame the crime on Anne Melton but they

had her in jail on suspicion for a while. She bragged

and told them her neck was too pretty and white

to put a rope around. Looking with those sweet

eyes at Mr. Grayson, | guess she persuaded him

that she wasnTt guilty. Anyway he got her off the

hook and later married her.

They say that just before she died she called

her husband into the room and told the secret. She

told one of the older women who helped look after

her when she was sick that oif | knew | wouldnTt

get well ITd tell you something that happened to me

in my younger days. But | might get well so | canTt

tell you.? But before she died, she did tell her

husband"he almost lost his mind, realizing what

he had done and moved completely out of this part

of the country. He couldnTt stand to face his neigh-

bors, knowing the guilt.

You seem to have made a fantastic adjustment to

being blind. How has your life and music been

influenced by the fact that you have always been

blind? Has the music helped compensate for the

lack of sight?

Well, ITll say that the music may have helped me

in many ways. One thing it did, it gave me an

opportunity to meet an awful lot of folks and go a

lot of places that | never would have gone. So in

14

15

16

that respect, it helped me, because the more people

you meet the more insights you get into life and

into living life. | think with each new person you

meet you begin to understand people in general a

little better.

| think that if the good Lord takes one of our

senses away from us, or He allows it to be taken by

circumstance, that He endows us with just a little

bit extra on the others so we can get an understand-

ing of life and maybe we try just a little harder.

Maybe the absence of my eyes was for a purpose.

ITve thought about it this way"thereTs no telling

what kind of unruly snob | might have been if |

had been a sighted person. Maybe the good Lord

knew that and He let circumstances take my eyes

so that I'd be just a little more humble and take a

second look at things. | think that if you are minus

one of the senses, you learn to appreciate the

others a little more.

Do any of the people you know still compose bal-

lads about everyday life the way they once did?

No, people donTt do it any more hardly. The last

ballads that | know of"genuine ballads written

about things here in the state of North Carolina"

were done by Norman Woodly and the Carolina

Buddies. They did the oBallad of Otto Wood? and

the oBallad of Charlie Lawson.? TheyTre the last

two that | know about that can be authenticated.

oThe Ballad of Otto Wood? was written in the thir-

ties right after it happened.

A lot of so-called folk singers in the popular

type folk song, do the folk song as a protest song.

Without preaching to anybody, your songs contain

more social comment than any other performer ITve

listened to. What is your feeling about using the

folk song as a protest song?

| donTt think any good music that is solely from

the heart of people should be used to further some-

bodyTs political aim. The early country boys did quite

a few songs that complained a little bit about en-

vironment and the conditions they lived in. Actually

if you listen to those songs they are poking fun

about their troubles. Singing about them kind of

put them down rather than raising hell about it, if

you want to put it that way. | donTt feel led to use

politics in my music in any way and | just ainTt

gonna do it. | donTt sing protest songs as such, if

| sing old time songs like oCotton Mill ColicT it

would be for the fun of it.

Merle, what shall we pick?

17

THE FLOWERETS

The pain pricks,

and twists

deeper

with the clock stare

and the whisper

of another meeting

after the hands

have passed

slowly around.

If no others are shared

what remains

but a needling pain

which happy jTs and silly brew

only ease, never cure,

and speed the hand

around.

Pain... lonliness...

empty words

loudly spoken by those

who whisper

queer.

Nicola Glover

Dead-flower wilted flags

hang

waiting to be picked

and thrown away

by children

who only want

to drink

rainwater.

Regina Kear

The coyote howls

Down the chimney

And through

Frost-lined window sashes

Begging to come in,

While the plush tiger

Stuffed with straw,

Sits in front of

A false fireplace

Trying

To keep warm.

Anita Brehm

OUT OF THE GARDEN

A small child f

pn maia ound

Strangled in the ;

her feathers "

wet from weepi

hee eeping

her wings

broken from trying to fly

where ther.

No sky. @ was

Regina Kear

The sun turns its back on the moon

Leaving it at the mercy of the night

And the moon

No longer seen by human eye

Or instrument

Loses all existence

And becomes a legend

Anita Brehm

FERRIS WHEEL

all the drunk delirious lights

and the seasick screams

and the cotton candy no one meant to drop

all the candied apple cores

I'll give you back the

torn tickets, piece by piece"

and the laughter

and the rideTs

Slow

shaking

end...

and the smell of fear

along the ground

Robert McDowell

19

ee

@ aes

|

WS) \

ee FE a em \

bh, wer

~

AL Ja

4

J, as

'"_ 2

Thomas Jackson

Just as Robin thought he would have to give way

and let her onto the porch, Miss WoodwordTs frail hand

plucked from inside her taffeta sleeve a lavender hand-

kerchief. She fluttered it nervously about her face and

dabbed at a veined V of white flesh beneath the folds

of her neck.

oGoodness, itTs like the middle of summer today,

isnTt it, Jonathan??

Robin neither moved nor answered. Miss Woodword

was thinking hesitantly about climbing around him in-

stead of asking him to move when RobinTs mother

called through the dark screen door: oHello, Blanche.

Come on in for some lemonade. J. Robin, move off

the steps and let Miss Woodword by.?

oWhy, thank you. Robin, are we ready for our

lesson??

oITm a mechanical man,? Robin thought, and leaned

forward until he almost pitched to the sidewalk at Miss

WoodwordTs feet. Then suddenly swinging his shifting

weight upward, arms dangling, he did an awkward

about-face and marched with stiff legs across the porch,

did another about-face and fell into one end of the

squeaky swing. He drifted there, holding his legs

straight out to clear the floor. Robin imagined a spring-

driven motor running down somewhere behind his

navel. oWhirr, clickity click.? The cold muscle of blued

steel spiraled outward. Brass-toothed wheels flashed

like spinning coins.

The two women smiled and politely laughed each

other into the dimness beyond the screen door. He

listened to the squeak, squeak of the swing and heard,

o..yes, and my nasturtiums are beginning to wilt...?

as they went into the den for the weak lemonade and

cheese crackers he had had earlier. As the spring un-

coiled, Robin dripped one leg, then the other, and let

them drag the floor until the pendulum swing hung still.

Robin watched a bumblebee worry the shrubbery by

the steps and thought oshit? several times"savoring

its newly acquired wickedness"and finally said it

aloud, but low enough not to carry through the open

windows into the house. He suddenly thought how

funny it would be to empty from the porch roof buckets

of his own excretion over Miss WoodwordTs head and

watch her run dripping down the sidewalk. He had

flung the liquid net spinning outward from the roof

when his daydream was interrupted: o. .well Pauline,

it does take time, even for the talented boys.? The two

women emerged from the dark door and sat in pale

green chairs opposite the swing. His motherTs chair

creaked as she crossed her legs and tugged at the hem

of her skirt.

Robin worked hard not to hear their conversation.

He concentrated on the cracks and peeling grey paint

on the floor beneath him, remembered his dream of

slinging shit from the roof, saw his spring-wound in-

sides"but certain phrases bumped at his consciousness:

orecital,? oMore practice,? operhaps a metronome.?

RobinTs dream flinched. The clean blue spring, like

concentric circles on dark water, wavered, vanished.

As he strained to push the womenTs words away, a

bright ghost, blown by an invisible wind over the

22

lawn, flashed into the porch and out again. The large

monarch fluttered up and up, then dropped back toward

the drooping shrubs as abruptly as an awkward kite.

Robin watched.

After bright and nervous indecisions, the butterfly

selected a ragged shrub beside the steps. He touched,

sailed up, touched again and was still. The women

faded. The blue spring coiled. Robin quietly slipped to

the floor. Half-sitting, with hands and heels he awk-

wardly slid himself toward the steps, stalking quick

prey. Slowly, carefully, never taking his eyes from the

orange patch, he felt his way to the edge of the porch.

One foot had reached the top step when Miss Wood-

word noticed.

oPauline, look"a butterfly. The first one ITve seen

in I donTt know when. IsnTt he beautiful.?

Mrs. Guntz answered in a voice like thin syrup,

oAhhh. IsnTt it gorgeous.?

And Miss Woodword: oAfter what the paper said,

the spraying and all in the tobacco last year, I didnTt

really expect to see any this spring. Oh heTs absolutely

beautiful.?

And Mrs. Guntz, with thicker syrup: oOne of GodTs

own. Every time I see one I remember that Sunday

the young man came. From Tennessee I think. You

remember, the one that hadnTt been ordained. . .? They

both wandered off into the dim sanctuary of the West-

lake Baptist Church. The butterfly and Robin were

forgotten.

From where he had frozen when Miss Woodword

first spoke, Robin moved again. He was on the second

cement step, then the bottom, and finally on the walk,

the rougher cement harsh beneath his palms.

Robin unfolded above the shrubs and swiftly pinned

the MonarchTs wings together between thumb and fore-

finger.

His mother saw him: oJ. Robin Guntz, you turn that

beautiful creature loose this minute.? The butterfly

exploded upward, above the roof, and Robin felt fine

dust slick on his fingers.

oAnd come right here.?

Robin dragged his feet across the grey floor and

stood by his motherTs chair. He looked at the string

of orange beads about her neck, the silver triangle at

each corner of her glasses, the emerald perched like

a wart on her finger, and tried not to hear her. o~SheTs

a parrot,? he thought, oA green parrot talking a jungle

language and I donTt know a word of it.? But he heard

dim phrases in the jungle"gaudy fragments of the

parrotTs squawk: o. . .GodTs creatures. And they should

never be hurt . . .squawk. . .Why what would He think,

Robin? Tell me that. What would Jesus think if. . .

squawk. . .?

The purple toucan butted in: o. . .scraank . . .like

music, Jonathan, and you should never harm. . .scraank

And finally: oNow go right in for your lesson, and

pay attention to what Miss Woodword tells you. Do

you hear me??

Miss Woodword followed Robin into the dim house

and soon Mrs. Guntz, still sipping her lemonade on

the porch, heard the piano scale stumble: oC-C-D-E-

F-G-A-B-C, C-D-E-F-G-G-G-A-B-C, C-D-E-F-G-A-B-

C-, C-B-A-G-F-E-D-C. Later she hummed out of tune

with RobinTs stiff ojoyous Waltz,? and the butterfly

returned to flutter, through RobinTs music, from shrub

to shrub around the L-shaped porch. Mrs. Guntz did

not notice him.

When she was nearly asleep, and the column of ice

cubes in her glass had crumbled and fallen, the screen

door banged. Miss Woodword and Robin came out.

Miss WoodwordTs face was slightly flushed and her

lavender handkerchief fluttered around the white V.

RobinTs mouth twitched, Mrs. Guntz noticed, and she

decided he needed to blow his nose.

Robin sat on the swing, upright this time, and Mrs.

Guntz fumbled in her purse for a five dollar bill:

oBlanche, you must stay for supper.?

Miss Woodword edged, sideways and smiling, toward

the steps, fluttering her handkerchief, and said oI canTt.

I really canTt. My niece is coming over for a lesson

later this evening.? Mrs. Guntz was inside the house

before Miss WoodwordTs crepe soled shoes had sucked

out of hearing.

It was hardly four, but the sun flooded warm hints

of sunset on the lawn. Robin noticed the butterfly at

the far end of the porch near a large First-Breath-of-

Spring bush. He glanced at the door and began to

untie his tennis shoes. When both shoes and two red

socks were heaped beneath the swing, he pulled the

bright striped tee shirt over his head and left it where

he had been sitting.

The Guntz house, like many of the older ones in

Westlake, was not underpenned but rested on periodic

brick pillars high enough from the ground for a dog

to run under. Underneath, no rain ever blew. From

beside the cement steps Robin now crawled on his

knees into the powdered red dust beneath the porch.

The quiet was dim and cool about him. He paused and

spit on his right forefinger; then, touching it to the red

dirt, he smeared two pale streaks on each cheek. Then

crawled toward the horizon of light at the other end

of the porch.

As his hands reached the fringe of weeds and grass

the boy could hear the blood swish deep in his ears.

He opened his mouth: the breath in his nose was too

loud. After a frozen moment, he turned on his back

and wiggled completely from beneath the house into

the hiding lower branches of shrubbery.

Carefully, branch by branch, Robin snaked his arm

up through the First-Breath-of-Spring. He missed one

wing, but caught the other and tore it before he could

use both hands to pin the struggling bronze monarch.

He dragged his feeble prisoner down through the

branches, blinked fine wing-dust from his eyes, and

wiggled back into the dimness beneath the porch. Soon

he was near the dark center of the house. Over his

head, from the underside of the den floor, ancient

spider webs draped a cool and silver silence.

Robin tied the insect, wrapping a piece of thread

pulled from the hem of his pants around and around

until wings, body and legs were well entangled. With

his prisoner secure in a scooped-out-hole in the dust,

Robin formed a small earthen mound in which he stuck

a weathered ice cream stick. Then, careful not to crush

his prisoner, Robin tied the butterfly to the stick with

another piece of thread. He took two candy wrappers

from his pocket and arranged them.

With the forbidden matches that he always carried,

Robin lit the gathered paper. Flames singed the dark-

ness. Light tore at the spider webs. When his prisoner

blistered, clawing with one free leg at bright pain,

Robin cried aloud.

23

My year is nearly drawn

not one complete circle

of time

but broken

fragments of round

connected

by a child

making bold (but shaky )

lines

with a

bright orange crayon.

Words of two

continents

separated by

an ocean

and three thousand miles

of lines

in bold (but shaky )

bright orange crayon.

Regina Kear

no weaver, my Penelope.

she knits and purls

the yarn of me

into whatever i wish to be,

now lover

again singer

sometimes poet

and binds off fear

of night ravel.

Edwin Page Shaw

Purple pleats that

loosely bind the

bouncing boom of her,

become the girl.

Wild laughter

and soft lines puckering

the funny corners of her mouth,

become in pleated fancy

the essence of

her.

Relative descents mar

my perfect understanding.

Wandering birds? " A falsity.

only humans wander quite

so lost in their created

emptiness.

The endless hollow of a coffee cup

becomes the sea

when held close

to a human ear"

A gravel driveway

crunching under baby feet,

becomes oback homeTT".

And purple pleats

that bounce and swirl

el=1aniare|

an echo-chambered laugh

become

what once

allowed me to believe

| had a soul.

Jackie Sweeney

Against the WINDOW

| loved old Furniture as a child "

Its distilled scent of

Generations

Perfumed many tender dreams

Now | know the world

All freshness has turned stale

Noise crows silence

Out There

An intrepid world

| feel its heartbeat in mine

| grope through myself

Toward the locked window

Rust of ages seals the latch

Out There

Leaves and birds sing of

Freedom and fulfillment

Sea gulls shriek

Awakening winds gather might "

Gentle breezes and hurricanes

Time scatters what has been mine

Once precious

Today worn Antiques

Rust of ages seals the latch

My once gentle hand

Grips a vulgar brick "

As a shadow clouds the pane

No dead matter any more

Et 43: CE jen gs

Maxim Tabory

25

THE WINO

i iTaey

with ripple-red face

Elale mare ig

like rotting birch bark

staggers

into a cluster

of gently swaying

flower children

and stares

han calomel lew iamelene

blazing suns

of the rising generation

and says,

oITm just like you.?

Wide eyes

look up

and see the

shredded black remains

hanging

on the splinters

of what was, maybe,

a great man.

i at-sTam (ele) qe-ham='-lolaime)dat-1g

and laugh.

After a while

everyone gives the wino

a dime

so he will leave

but he stays

and the laughing stops.

Regina Kear

Auction

Selling is never easy

except in shops where the very rich or the poor buy

things they can or cannot afford.

But under one slight tree

too late turned green,

too little leaved, people

do not much want to buy.

The most exchange is news,

a carpet reminds, a chiffonier confuses:

othat rug was laid when Sara was a girl.

that chest"was it always in the family??

And people talk

and stare idly at the goods

they do not want

but could not wait to see

for seeing makes an escape from doing

and doing is dull inside country houses.

Selling is never easy.

It gives the auctioneer a sore throat

and the bidders guilt for aimless greed

and fills the road and drive with too many cars

Causing stray cats and tree-settled birds

too much confusion.

Selling is never easy

for any few gathered there who walked

upon the rug, or kept hairpins on the chiffonier

and see the rug now rolled,

the chest labelled and pushed to the front,

tapped and turned from some familiar thing

into some shrill-voiced bargain.

Selling isnTt easy.

It only may seem so

on those auction days

when oneTs whole life

sprawls jumbled

on some lawn

and silence

catches on the note

of some startled bird

or in the shadow

of some scattering cat.

Then the eye of that seller,

who is not paid to sell,

breaks across

the dying commerce of the day

and in a momentTs

ultimate horror

begs the bidding

to go on.

Selling isnTt easy.

Yet, we do it.

Here under the skinny tree

all the mad scruples of our age converge

to raise the dead

and set in high, uneven relief a life

only finally finished.

We let nothing go to waste.

Sharon Shaw

SE SAAS cA PT REDO A Sip ty dy CESARE LAE 29 SS EET

oe Mae eer ene Re aie

(ELTA Eat. Ee A

UWIAA SS. , ees =how

:

§

».

of

, T B {

") a T

s 2 |

!

Vv)

, :

siete

4M,

40

Zz

ZZ

474

Hy)

ry

ALAS

a

Li

Aeneratle

pnintinn -

WM AW4NG, ,

~Qh Ahab.?

Carr.

BW 00-A -

at

The Meaningfulness of Art, What is

Unless you're inclined to be president of General Motors, art is the only valid manner to while

away your 72 earthly years.

What do | mean by that! Well, for one thing | donTt mean art is drawing pictures or whatever

activities are currently considered oart? by the ocultured.? Art is, rather, a verb, a way of life, a way

of doing, which means a lapse of purpose-consciousness that unselfishly turns attention to the

method of achievement and by doing so, creates an experience satisfactory in itself, a disinterested

sense pleasure. Another happy result is that quality usually goes up when pleasurable care is taken

in the doing.

lf this feeling of art is applied to all human activities, then life is good (but, too, if you know the

definition, life will be oh-so-hard without it). On the other hand, if you want to be president of

General Motors you arenTt interested in pleasure and you'll be able to afford enough diversions so

you wonTt have to think about it"or anything if you choose. But remember, once a person asks

oWhat is it all about??, art is vital. Philosophy and religion are concerned with the purpose, the end

(unless they are done with a sense of art ) but art is what gives life to the time students of the world

spend questioning, before they donTt find the answer.

She finished the dishes, rinsed out the sink, wrung out and hung up the dish cloth, while

staring out the window. She thought, oBreakfast is over. Lunch is hours away. Here | am between

meals again. What shall | do (period. no question mark ) | may live another 50 years.

Art gives meaningfulness to your 72 years. It is unChristian. That is, it doesnTt count on heaven

for happiness. Art is the present.

Old Master: | churn the clay by hand and pack it into my brick forms here with my hands.

Young Upstart: ItTd be real easy to rig up a crank and funnel that would do it twice as fast.

Old Master: Yes, it would.

Young Upstart: Well, why donTt you do that?

Old Master: Because | like to do it with my hands. | know each brick that way.

Can the Old Master tell Young Upstart his reason? He can come close with functional, practical,

efficient words, but the communication will be complete only when Y.U. ogets it.? When he lets the

manner of the old masterTs work show him the beauty of the bricks, the beauty of living.

Some things are best said in words; others are fluid and elusive and best represented by images

45

46

or actions. Such expressions restrict the audience because they require (-intuition?- ) but they widen

the range of communication and raise the quality for the reason that they restrict the audience.

Perhaps a word about words is due here. There are two owords? as there are two oarts.? These

immediate words you are seeing here are functional. However, the words in the scenarios above

manipulate images, and are artful. Get it?

So, letTs see, where are we? It seems like ITve said"can it be true" anything can be art? Even

washing dishes? Sure. It can be an art. But just as oart? and owords? have at least two levels, so do

artful activities. Objects produced with no ulterior function but sensual pleasure are the noun form of

our previously defined verb, oart.? They are things said with visual or sensual media and they are true

only in their own realm. If philosophers or critics attempt to say oThis painting, or whatever, is --------

it may or may not be true. It translates poorly. Just as you must judge whether a written or spoken

statement is true, you must do so with art"without translating. You have to learn to think in the

language, my Spanish teacher told me.

We must learn to derive meanings from perceptions on their own level, which means we cannot

submit to laziness and accept a second-hand judgment. Is it really a wretched day? | believe, say,

that the world is round, but | know the difference between dirt and sand. | know it with my feet, my

hands, my eyes, my nose, my ears, even my mouth and tongue and teeth. And furthermore, | can tell

you what those differences are"and it will be almost like the real thing.

Of course, this means that we must also learn to trust our interpretations.

The lean adolescent, twixt undershirt and training bra, held her head carefully high and still as

she talked. ~~Mother, what is love??

oThatTs a hard question.? The scissors clicked slowly across the fringe of tawny brown hair on

the childTs forehead. Mother stepped back, discerned that the left side was higher than the right

and stretched her scissor hand forward to correct the error.

oDo you love Daddy??

oYes,? she replied, looking at her daughterTs face now, instead of her bangs.

oHow do you know?? It was an honest question.

Devoting all her maternal concentration on the problem, she said, ~You just know.?

The music was even louder than before. The room smelled of tobacco and gin. Only a dozen or

so guests remained. As | carried my empty glass back to the trough, | passed two men | recognized

from my visit to The Company, one considerably older and rounder than the other. The More

Rotund said, oYes, but is it art?? The young slender junior-executive face of the second man showed

clearly that he did not know.

Art must, by its nature as we have defined it here, have a truth. An artist knows that truth and

expresses it. The work of art becomes an energy trap for that truth. If it is understood by a perceiver

there is communication; if not, there is an expression and still a truth.

What is the meaningfulness of .. .

meaningfulness?

A Poem by its Author:

| know

that | donTt understand

of 3

categories:

You donTt understand

but you think you do

or

you think that you

donTt understand and everyone else does.

So you make riddles, not |.

But, | lie.

jbmcc

47

S. SHAW

From a distance it seemed an orderly world with neat pastures and fields of fig trees

and wheat following one another along the road and up the sides of the valley. But seen

from a closer point on the winding dirt road, the squares and rectangles of the old

farms encroached upon one another and the geometric pattern lost its fine clarity in

the gnarled confusion of ancient growth.

One piece of land was mostly pasture with fig trees in the far corner and a herd of

black goats moving in slow circles. In the center was a cone shaped white dwelling

half shaded by a grotesquely twisted olive tree. On a bench in the shade of this tree

lonnis ate methodically from a long loaf of bread and cast a watchful eye toward the

goats. Once he raised his hand to his forehead and removed the black handkerchief

he wore when he worked in the sun.

As he ate the bread slowly his eyes left the goats to trace the three blocks of land that

were his. A hundred yards away he could see Sophia moving about gathering rocks

and piling them into mounds so that tomorrow when he began to work, the plow

would not hit the stone and break.

lonnis watched the woman moving in and out of the shadow of their oldest olive tree.

Occasionally she walked far to the right to place on a special pile the small pieces of

wood she found. He remembered a day like this when a much younger Sophia had

gathered stones and firewood on this same piece of land.

oTonnis!? she had called and, turning toward her he had seen that she held a large

object in her hands. oViepete! Vlepete!, lonnis.? She had hurried to the house and

motioned him nearer.

oIt is only a clay jar,? he had said looking closely at the brown shape.

oYes,? she had answered, wiping one side of the jar with the corner of her apron.

oBut look, Ionnis, here beneath the mud are colors and here,? she wiped harder, othe

head of a man!?

oI will hold it. You get a clean cloth and water and we will wash it.?

He had held the jar while Sophia washed it. Then they filled it with fresh water from

the spring and put it on the wooden bench in the shade. After that, every summer they

left the jar on the bench and they always had cold water to drink. In the winter they

filled it with wine and left it inside on the rough wooden bench between the olive

oil and old bottles filled with rice and flour.

lonnis ate the last of the bread and reached for the jar which rested a few feet away.

After a drink he re-tied the black band around his forehead and reached for his long

stick. The goats were beginning to stray.

Past neat piles of stones arranged like small pyramids and looking like Indian grave

markers walked a tall young man in khaki trousers and a short sleeved red-checked

cotton shirt. With the back of one hand he wiped the perspiration from his forehead.

Strapped to his back he carried a knapsack from which could be seen one corner of

a blanket and the thumbworn edges of several notebooks. At his side hung a scarred

49

50

leather camera case. His only other burden was a pair of thick sunglasses which he

had removed and carried carelessly by the bows.

oKalimera,? he said to the woman piling the stones. She returned his greeting, pausing

to examine him quickly and carefully, then bent again to her work. Strinton walked on

through the field toward the white house still some distance away. The day was hotter

than any March day he had ever known at home in Michigan, despite the discomfort

caused by the weather, Strinton thought Crete even more exciting than it had seemed

to him six weeks ago when he first stepped off the boat from Piraeus.

Looking ahead as he neared the dwelling he saw with relief the shade cast by the olive

tree. Beyond the house the goats moved noiselessly. Strinton saw lonnis pause half-

way between the herd and the house, lean lightly on a tall stick and patiently await

his approach. Slowing his own pace imperceptibly, Strinton imagined for a moment

that the old man was a shepherd from the classical past. His posture against the

somber quietness of the animals so mimicked antiquity that Strinton was practically

upon the house itself and the old man had dropped his stick and moved to meet him

before the vision faded.

oKalimera,? he repeated to the man.

oKalimerasas. Ti Kanete??

Strinton was fine, but hot and eager for a drink of water. oPoli Kala. Parakalo, kirie,

thipso.?T

oNai. Nai.? lonnis nodded and motioning Strinton to a seat on the bench he walked

into the house. Returning a moment later with an empty wooden box and another

glass he sat down on the box and reached for the water jar. Strinton had dropped his

knapsack to the ground beside him and reached gratefully for the glass the old man

handed him. For some moments neither man spoke. Strinton drained his glass and

brushed his forehead with his hand, but he was perspiring less now that he could

relax in the shade. lonnis, however had shifted his box almost directly into the sun-

light and leaned forward resting both elbows on his knees.

As the men talked langurdly punctuating their conversation with long silences, the

goats grazed quietly. Sophia gathered the last remaining rocks and was stacking them

in a small pile. Propping one foot on his knapsack, Strinton gestured toward the land

about him.

oBeautiful.?

Ionnis half closed his eyes and accepted the praise with a smile. oYes, it is beautiful.

It is mine. You are American?? He moved his box to face Strinton and poured more

water into the young manTs glass.

Strinton nodded, then asked, o~Where did you get this jar? It is a fine looking thing.?

Konnis placed the empty jar on the sunlit end of the bench. oIt is broken a little and I

think very old. . . poli palyo.?T He repeated the last words watching Strinton and

s+

52

thinking how all strangers looked alike. oThe woman found it while gathering stones

in the field. Once in a museum in Iraklion I saw jars that were chipped and beautiful

like mine.?

Standing up Strinton looked at the jar for a moment then at Ionnis. After a moment

he lifted the vessel from the bench and walked back and forth before the house,

holding it carefully and looking from the jar to the fields.

oYou are like all the others,? Ionnis told him. o~All the others who come here tell

me this is a very old jar and then they look at it and at the fields as you are looking

at them now.?

Without answering, Strinton returned to the bench and placed the jar just where Ionnis

had left it. Then he backed off without taking his eyes from it. Against the white house

the jar cast a sharp clear shadow. oIt is very beautiful,? he said.

oThe sun shines brightly on the colored figures,? Ionnis remarked watching him.

Strinton nodded and moved closer to trace them with the tips of his fingers. lonnis

laughed. oIt will not break if you touch it. The pictures are old but they will not fall

off.? He laughed again at the careful way in which Strinton touched the jar, and this

time his laughter was so loud that Sophia turned from the field and waved to him

before she gathered the small pile of wood in her apron and began walking toward the

house.

Ionnis, watching Strinton would have said themberazi but he knew it was no good

saying never mind? to such young men. Instead he said, ooVases and old jars are good

for museums and good for people to see but not as good as rows of fig trees and olive

trees.?

Slowly Strinton withdrew his hand and moved a little so the sun threw his shadow

across the bench. Ionnis had stopped laughing. oYou are different from other

strangers,? he said, turning away.

Strinton stared hard at the jar. He thought of Knossos and the huge jars that stood

there behind heavy wires, and of the bronze head of Sir Arthur Evans that rested by

the entrance to the palace. He thought of the woman piling stone, the old man in a

moist black headband and the water from this jar that had tasted so cool. He turned

away from the jar and he and Ionnis stood smiling as Sophia approached.

oTi Kanete? she called across the brief expanse of land oHow do you like our jar??

oIt keeps the water very cold,? Strinton called back.

oYes, it is good.?

oThe goats are beginning to stray,? Ionnis said, moving away. ~ooWe have lamb... you

must eat with us.?

Strinton nodded and wiped the perspiration from his forehead.

SKK ISRO OX

WITH YOUR MUSKET, FIFE, AND DRUM

When he was six and tough-guy

and she had chocolate on her face,

he said, T| want to be a firemanT,

and went on climbing trees

against the sunTs dumb blazes

far in the upper leaves.

She stayed below

full of lollipop attention

and reeled off miles of hose

from the garbage can.

Then he was twenty

and she was his wife,

anxious to suffer the paradise

of plastic dishes

and cold linoleum

guarded by a sometimes Car.

And two months later

he was shuffled off

to a din of drunken hero fanfares,

to a nightmare land of funny men

and jungle death ten thousand miles away

from the toy town trees.

She made a real religion

of the coming of the mail

and answered with the sacrifice

of anxious prayers, stale cookies.

On this mute Sunday

there is no one at the station,

except the boys who do a regal two-step

around the hearse and slam the door

like so many potentates

at a clerkTs coronation,

perfunctories for the defunct who drive away

and, out of sight, light cigarettes

and talk about old ball games.

The show is cardboard.

There are no more tears

for the awful ride

to the cool old home

beneath the burning branches

when dogs were bears

and every garage was really

a den of japs.

David Lawson

53

AFTER GRANT WOOD

Now you are dead, all of you.

And with you died the body

of three generationsT tyranny,

the absolute and sphynx-like disapproval

of everything from love and whiskey

to quiet April rain.

Even your children

in the echo of your rusted chains

are now too old to change their lives.

They walk with the inarticulate

ghost of guilt

half-smothered

in monotonous meals and payment books,

the weekly rags which culminate

in a thousand restless, deathsome Sundays,

the four oTclock fear

and terrible twilight

when the scripture starts to quiver on the shelf.

You schooled them in your churchy ways

and never smiled without purpose;

every word a quote or couplet:

Timothy minus the fermentation,

Franklin without the whimsey.

You preached God's light.

But Christ!

54

In the middle of a midnight sweat

when Satan grinned

on the landing bannister,

each floor creaked with enough conviction

to make old Calvin re-consider sin.

And now secure in your martyrdom,

breathing the wispy hymn-filled air

beside your celestial, sexless fathers

in the Beulah Land

for which you lived and trudged

with downcast eyes

through eighty years of allegory

and middle-class privation,

can you know the measure of your victory?

We walk like half-believing prisoners

recently pardoned

for a crime beyond memory,

now that you are dead,

almost all of us?

David Lawson

IN A CABIN AT NAGTS HEAD WHILE THE

WIND ASSAULTED

We were by the stove

while the ocean threw a tantrum

and the wind assaulted the outside walls

to pummel itself on the rooftop.

It was a tar black night

but the coffee was strong as turpentine

and the cigarettes tasted

good enough to eat.

the cheap chianti,

un vino simpatico,

rattled our heads and we talked about

our neurotic friends all over the nation

and the trouble with civilization.

Then somebody tried to quote Yeats,

and somebody chortled.

On the shore in the morning

was a slick fat fish.

His tail had been cut clean

by a passing boat.

David Lawson

MESA VERDE

The dead boiling up

In the ground

| have been to a great cave

Where the dead lived

Dead Indians

From a long lost age

| have climbed

Their ancient now-renewed

Ladders

Peered into the places

Made to store grain

Climbed from level to level

In houses where even stocky men

Must have had to stoop

Drunk from the spring

Where they got their drinking water

Looked out

Over miles

Toward the horizon

As they must have scanned it

Searching for the enemies

Who finally overcame them

In that time

Long ago

Frederick Sorenson

55

56

INTERSECTION

BY LAWRENCE CLINE

As the traffic signal changed from green to

yellow to red a pale blue Falcon slowed routinely

to a halt. Small crowds of late evening shoppers

hurried from corner to corner seeking temporary

shelter from stinging November winds.

Inside the car Christopher Lamonde glanced

disgustedly at the small black knob on the dash-

board labelled oDEFROSTER.? With glove-covered

hand he reached to clean the driver's portion of

the foggy windshield and inadvertently sprinkled

cigarette ashes across the opening of the defroster

vent. After taking the last possible puff his cig-

arette could offer, he carefully balanced the filter

on a growing pile of butts in the ashtray. oGod, it

must be cold!? Christopher shuddered as he gazed

through his self-made window. He was delighted

to discover the flashing First Federal sign a block

down the street. Twenty-three degrees at six forty-

one. A quick look at his wristwatch left him smil-

ing. His watch was truly independent. Another

group of shoppers passed by. Smiles were absent,

not so much due to unfriendliness as to a fear of

splitting stiff chapped lips. Fingers burrowed deep-

ly into overcoat pockets, leaving the warmth re-

luctantly to aid a red runny nose. As the last of

the shoppers filed by, Christopher realized the

light was once again green. A loud horn blast from

the car behind accompanied his left foot as it

eased out the clutch. The unexpected reminder

caused the Falcon to jerk into motion. Simul-

taneously a carefully balanced filter rolled off a

pile of cigarette butts and fell to the floorboard.

oSon-of-a-bitch!? barked Christopher instinctively.

Quickly he changed from first to second gear and

smoothed out his jerky start. Looking to the rear-

view mirror, he strained to see the driver of the

impatient car. A foggy rear window restricted his

vision, and brought a wry smile to his face. He

didnTt really want to see the son-of-a-bitch anyway.

Strangers were good people to know, and Christo-

pher wanted to keep it that way.

With the time and temperature of the First

Federal sign several miles behind him, Christopher

turned into a well-lighted gas station. The double

ring of the service bell announced his arrival to the

attendant, who buttoned the top of his coveralls

and came outside. Christopher rolled down his

window in order to open the door with the outside

handle. Stepping from his car and slamming the

door shut, he heard the attendantTs greeting.

oFiller up, felluh?? The attendantTs name was

Jack unless he was wearing someone elseTs cover-

alls.

oYeah, and check the oil if you donTt mind.?

oDonTt mind at all, felluh. ThatTs what | get

paid for.? Christopher nodded in agreement and

headed for the warmth of the building. Pulling off

his gloves, he searchd his pockets for cigarette

money as he crossed the oil-stained concrete.

The search yielded only two dimes and a couple of

cold brown pennies. Unable to pay off the vending

machine until Jack returned with change, Christo-

pher looked for the restroom. Outside another car

had just pulled into the station. Jack placed the

gas pump on automatic and left the blue Falcon

to drink by itself. He obviously knew the driver of

the other car, for he went directly to the passenger

side and hopped in. The driver of the car was a

woman but Christopher could not get a clear look

at her. She must be a real beauty if Jack could

jump right into the front seat beside her. Jack

wasnTt the most handsome guy Christopher had

ever seen. Maybe she was his wife. No, Jack al-

most ran to get in the car. CouldnTt be his wife.

57

Christopher gave up on the mystery customer

to relieve his expanded bladder. Closing the rest-

room door behind him, he unzipped his pants.

Above the urinal was a hand-written sign: oOut of

Odor!? Christopher moved inside the small booth

and with careful aim began a vigorous bombard-

ment of a cigarette butt floating in the toilet.

That Jack sure had a fine sense of humor. Christo-

pher looked up and down the walls of the restroom

to check out the local graphitti. He saw nothing

he had not seen before, some time, some place.

Completing the destruction of the imaginary ship

in the yellow ocean below him, Christopher step-

ped out of the booth and up to the sink. As he

washed his hands he checked himself out in the

remaining portion of a shattered mirror. He was

tired and his eyes made the fact obvious to anyone

interested enough to notice. He looked around for

a towel of some sort. There were no towels. Christo-

pher folded his arms across his chest and dried

each hand under a warm armpit. Jack probably

enjoyed seeing people leave the restroom with wet

hands. Remembering something that he had for-

gotten to do, Christopher walked back to the toilet

and flushed it.

Jack was still sitting in the other car when

Christopher came out of the bathroom. A large wet

spot under the rear bumper told Christopher his

car was filled with gas. While waiting for Jack to

come back inside, Christopher gazed at the various

displays scattered about the stationTs interior. On

the counter beside the cash register was a display

of headache remedies. Christopher had no head-

ache, so he quickly moved to other items of inter-

est: an STP display, various brands of motor

oil, and a November calendar with a naked woman.

Gas stations were pretty much the same. Looking

overhead Christopher stared at a Budweiser clock

with the familiar horses pulling a beer wagon.

You couldnTt even see what time it was for the

damn wagon. How long had he been waiting for

58

Jack to return, anyway? Christopher began to grow

uneasy and walked outside. Taking the gas nozzle

from his car, he replaced it on the pump. He

noticed Jack was sitting in the middle of the front

seat next to the woman. Both were sitting very

low in the seat so that only their heads were

visible from the rear of the car. Christopher walked

up to the door of his car, opened it, and looked over

to see if he had gained JackTs attention. He hadn't.

Christopher was becoming quite irritated with the

service heTd received. JackTs work was worse than

his humor. He eased behind the wheel of his car.

Trying not to be too interested, he glanced over

the trash barrel between the two cars. Goddam!

Ole Jack was really going to town. This was un-

believable. So thatTs what Jack gets paid for.

ChristopherTs irritation was now mixed with a

strange sort of embarrassment. He felt weird sit-

ting at a gas station with a couple making love in

the front seat of a car five feet away. It was like

being at a drive-in movie and looking at the car

beside you, except for the gas pumps.

ChristopherTs thoughts were interrupted by

flashing headlights. A third car pulled into the gas

station. Jack must have seen the lights too, for

he quickly reached the door of his girlfriendTs car.

When he got out, his girlfriend drove away. Jack

stood there breathing heavily, trying to button the

front of his coveralls.

Christopher reached out his window, opened

the door, and got out of his car. Jack walked over

as if nothing had ever happened. oYou musta been

driving on fumes. It took almost fifteen gallons

to filler up.?? Christopher handed him a credit card

and followed him into the station. The horn on

the third car made a polite honk and Jack threw

up two fingers in recognition. oBe right with you.?

Christopher thought of asking for change in order

to buy a pack of cigarettes, but decided against

it. Jack mumbled the figures as he filled out the

credit card form. ~Fourteen eight tenths gallons

.. . thirty-six point nine...? After checking the

pump again for the total Jack turned to Christo-

pher. oThat'll be another five bucks you owe at

the end of the month.? He tore off the receipt

and handed it to Christopher. ~Thank ya, felluh,

and hurry back.?

Christopher hadnTt said a word to Jack since

he had first told him to fill up the tank. He felt

the need to say something before he left. oDidn't

you check the oil?? Jack gave him a questioning

look and then broke into his business-like smile.

oOh yeah, I'll catch it right away.?

oThat's all right.? Christopher returned the arti-

ficial smile. oYou're probably pretty tired.? As

Christopher walked out the door the third car

pulled away from the pumps and was gone. Christo-

pher stopped, turned around, and looked at Jack.

Shaking his head in disbelief he walked back to

his car, got in, and hurried to get away. He had

known Jack only forty-five minutes at the most

and already knew him too well. What a bastard.

Several miles down the road the pale blue Fal-

con slowed routinely to a halt as the traffic signal

changed from green to yellow to red. Christopher

Lamonde looked out a foggy window at the few

people still walking the streets. Christopher felt

a little more at ease. Strangers were good people

to know.

59

DESERTED BARN

Prow pointed,

Like an old grey ship,

This weathered barn

Deadheads her hollow hull:

An empty ark.

No Noah

Nor sons of Noah

Whose hand or will

Can hold the helm

Or heel the timbered decks,

She shudders

Against the waved furrows

As in a gale.

Abandoned by all but rats,

She hauls the run-out ends of ropes,

The tack and tools of dead trades;

Shipping slow ruin

Through split strakes,

She slips in timeTs slack tide,

Her wake, toward dim shores

Where hulks and relics vague

Lie quiet

As bones.

Thomas Jackson

A GEOPOLITICAL REVELATION OR,

A SENSE OF HISTORY

Ascending a hill in southern Ohio

| look back across the water

to the powdery mountains of West Virginia

and instantly grow aware

of the river | crossed:

Not long ago | was over there

far to the south of those shadowy mountains

deep in the ancient dust of

North Carolina

chasing the ghost of Lord Halifax

and his train of specteral pretenders

in their faded lace

through the feeble moonlight

and broken tea cups

of sad plantations.

And now | am climbing a cartoon hill

speckled with comic book cows

and big Dutch barns

near Pennsylvania.

| have crossed the Ohio River.

The jugular python of the Grand Republic

all times prior to sixty-five

now mothers beer cans

and a few lethargic barges.

Ascending a hill in southern Ohio

this part of the country

becomes a sandbox

full of curious,

apparently purposeless toys.

David Lawson

61

Lc ca a crams oam

~.

REVIEWS REVIEWS REVIEWS

A ChildTs Garden of Grass

By Jack S. Margolis and Richard Clorfene

Americans are notoriously addicted to guide

books and hand books and how-to-do-it books;

they crave the reinforcing opinion of some self-

appointed expert. Now, for the 20 to 40 million

regular potsmokers in the United States, there

is A ChildTs Garden of Grass: the Official Hand-

book for Marijuana Users. Sound facetious? It

is, and equally informative.

The authors begin in quite a straightforward

fashion. oOur viewpoint, without defending it

here, is simply that marijuana is not harmful

in any way. . . does not lead to the use of hard

narcotics, and should be made legal subject to

the same or similar regulations which now apply

to the use, distribution, and sale of alcohol and

tobacco.? Margolis and Clorfene are enthusias-

tic advocates of marijuana, and in this little

book they recommend it for everything from

headaches to frigidity.

Sandwiched in between the sales talks are

some valuable pearls of wisdom for the curious.

What does it feel like to get stoned? oThe first

sensation you feel will be physical; a new ting-

ling of some sort, a band of light pressure

around your temples... you will relax. . . this

relaxation almost instantly melts into a quiet

contemplative euphoria, and a soft muting of

everything.? That is a subjective but fairly

honest description.

A ChildTs Garden of Grass may be subjective

but it is never aloof. Every aspect of the weed

and its enjoyment is examined, from rolling a

joint to seducing a woman. Here the authors

make a valuable distinction between grass and

the drug it is most often compared to, alcohol.

oLiquor, of course, has been the traditional

euphoria producing tool of the seducer. Seduc-

ing a drunken woman is as satisfying and stimu-

lating as winning a philosophical argument with

a dead goldfish. . . but grass heightens your en-

joyment of your perceptions and conceptions

tremendously.? The next few paragraphs are

religiously devoted to the joys of sex and mari-

juana.

Serious consideration is given to the dangers

of marijuana: getting busted. Margolis and

Clorfene advise that you hollow out a book and

hide your pot in it, but not his one because it is

too thin. The authors shower you with a treasure

of practical and impractical tips"recipes for

those famous grass brownies, instructions for

making a water pipe, and a diagrammatic trea-

tise on the European Joint. A ChildTs Garden

of Grass has something for everyone, with the

possible exception of John Mitchell.

William R. Day

63

NT

64

Islands in the Stream

By Ernest Hemingway

Ernest HemingwayTs celebrated posthumous

novel ISLANDS IN THE STREAM provides most of

the elements that Hemingway lovers admire, which

are also the elements that his critics have grown

to deplore. The novel written in the late forties

presents Thomas Hudson, an established and tal-

ented painter, as another ~~Hemingway Hero? who

involves himself in stoical contemplation, love-

making, fighting, killing, suffering, and dying. His

adventures are as unbelievable as real life, and his

comments are often concentrated gems of human

understanding. HudsonTs developing character is

the central unifying device in an otherwise loosely

structured work which takes place in two distinct

settings of time and place. The theme is interwoven

with HudsonTs character and essentially concerns

his psychic -journey from disciplined happiness,

through tragedy, to a type of existential resolution

which ends with his mortal wounding at the end of

the novel. The time is first an unidentified date in

the thirties and later an early date in World War

Il, and the places are the Bimini Islands and Cuba.

In addition to Thomas Hudson, Hemingway has

created a group of keenly drawn minor characters

who are roughly the same local-color types that the

reader has seen in the other novels, particularly

FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS and TO HAVE AND

HAVE NOT. Collectively they seem to represent

most of the virtues of human interaction, including

bravery, trustworthiness, selflessness, and a sense

of kinship with other men. There are several

memorable ones such as Honest Lil, the prostitute

with the proverbial heart of gold; and Willie, Ara,

and Henry, three exceptionally mean and loyal

basques. Other unique characters are Hudson's

three young sons who appear only in the first sec-

tion of the work. The reader is drawn sympathetic-

ally to these figures who are presented in a

splendidly idyllic beach setting which also includes

a long fishing scene comparable to the longer one

in THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA. The beautiful

boys are unbelievably precocious, but otherwise

they serve as symbols of the innocent perfection

possible for human beings.

The scenes in the novel are like islands in a

stream, fading into a slow moving and dream-like

narrative for which Hemingway has purposely not

prepared the reader. Although it is with HudsonTs

character that the reader is primarily concerned,

it is possible to go beyond Hudson and lose your-

self in the narrative, partially because other char-

acters reveal themselves through the third person

point-of-view and partially because the settings

themselves are inviting. The reader quickly accepts

the implicit invitation to roam the beach, to swim,

fish, and drink with HudsonTs group. Hudson is

selfish only with his memories, and for the occa-

sional sex scenes the reader is forced to find his

own partner since Hudson does not share his

openly but merely mentions when he has finished.

Otherwise the sensitive reader suffers along with

the other characters and is only too happy to be

alive after the heavy firing at the end of the novel.

The only difficulty in following the narrative lies

in the fact that Hemingway dies not use the same

characters in each of the three sections; instead,

he introduces a realtively new group each time and

presents the earlier characters only as memories

in Thomas HudsonTs mind.

Although ISLANDS IN THE STREAM is a novel

centered around the war with its subsequent trage-

dies and deprivations, the themes are neither poli-

tical nor involved in polemical idealism. This lack

of social analysis will possibly alienate a number

of contemporary readers who have grown to expect

a dialectic discussion in their fiction. However,

such an approach to fiction was never HemingwayTs

forte, even in his serious political novel FOR

WHOM THE BELL TOLLS. Hemingway seemed to

prefer basing his themes in the universal aspects

of the individualTs struggle in his journey through

life. The reader can note this unique personal

struggle in all of HemingwayTs novels and in most

of his short stories. In this respect Thomas Hudson

is simply another turn of the oHemingway Hero?

who develops resolution in the face of meaningless-

ness, danger, and tragedy. It is only the names of

the oheroes? and the settings that change from

novel to novel, and the minor characters even

seem interchangeable. The reader needs only to

compare the irregulars in FOR WHOM THE BELL

TOLLS and TO HAVE AND TO HAVE NOT, or the

regulars in A FAREWELL TO ARMS to see the

similarities. But such comparisons do not make

ISLANDS IN THE STREAM a weak novel, nor does

it make Thomas Hudson any less desirable to note

that his creator made several other men in his

likeness. Hudson must be examined, as a man and

as an artist, in the context of his own struggle.

In examining Thomas Hudson, the reader must

note that Hudson has an extra dimension. He is an

artist, and he is forced to view himself as distinct

from other men, at least in the first section of the

novel. Hudson is dedicated to his painting, and he

works at it instead of leading a normal family life,

probably because his driving talent will not allow

him to follow bourgeois pattern. Ultimately, his art

becomes a duty more important than anything

else for his mental well-being. His art in effect

resolves his existential quest for meaning and

allows him to re-define himself daily. However,

HudsonTs driving passion becomes something

merely parallel with art in the last two sections of

the novel when he begins chasing submarines in

his boat. His sense of duty remains, but his urge

to create is not the predominating passion. Thus

we may view him as a universal existential hero,

as well as an artist, who must satisfy his quest for

meaning each day through the duty he has set for

himself. Clearly the duty in the last two sections

of the novel, chasing submarines, is not creative

in the same sense as painting, but it serves the

same purpose in his life.

HudsonTs existential resolution is easy to follow

through the three sections of the novel as he

accepts his tragedies and deprivations by burying

himself in his sense of duty which includes, later

in the novel, a passive desire to be finished with

such a precarious life. When we meet Hudson in

the oBimini? section, he has had two divorces and

his boys visit him only occasionally. He is alienated

from a typical family life which he seems to miss;

however, he understands that such a life and his

work are not compatible. And since he loves his

work, his life is carefully structured with a daily