[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Of course the top is power-oper-

ated"no extra cost" because this

is the Rambler American ~~400?

Convertible.

You may not believe itTs Amer-

icaTs lowest-priced convertible"

but it is, with no ifs, ands or buts.

Can it move? Definitely, and with

plenty of get-up-and-go" because

this rakish Rambler sports a snappy

125-HP overhead valve engine,

with a power-to-weight ratio that

sort of puts wings to your going.

(Interesting aside: the Rambler

American holds more top honors

in major economy runs than all

1962 Rambler American °''400"' Convertible"quality-built and lowest-priced

the other compact cars combined.)

What else is wonderful about

this sunful and funful car? Just

about everything.

Double-Safety Brakes that stop

when other brakes canTt (self-

adjusting, too). More carefree and

trouble-free motoring, with 4,000

miles between normal oil changes,

more thorough rustproofing (in-

cluding RamblerTs famed up-to-

the-roof Deep-Dip), the Ceramic-

Armored muffler and tailpipe that

won't rust out.* Even the exclu-

sive K-Stick automatic-clutch trans-

mission, for only $59.50*, with

* Furful x Wonderful

the fun, control and economy of

stick shifting.

You'll find a whole host of ad-

vancements in the T62 Rambler"

and you'll find all prices really low,

starting with AmericaTs lowest.

See your Rambler dealer"now.

*If muffler or tailpipe rusts out, collision

damage excepted, either will be replaced

free by a Rambler dealer for original

owner for as many years as he owns his

Rambler. Price of E-Stick Transmission

is manufacturerTs suggested price.

AMBLER

World Standard of

Compact Car Excellence

=N VOLUME V SPRING, 1962 NUMBER 38

VR TABLE OF CONTENTS

bie | CONTRIBUTORST NOTES 35

} Ke WN |

Va 4 FEATURES

h ~ a y Interview with Frances Gray Patton ace 3

WO Ld The Poet As Teacher by Karl Shapiro. 18

LN FICTION

ry The Secret of McCravenTs Cove by Charles L. Shobe, Jr. 240

r DRAMA

I AinTt Too Yit, a monologue, by Harry C. West i:

ESSAY

John P. MarquandTs Use of Background as Satire

by Richard L. Taylor. 26

POETRY

Pagan Rites by Sarah Hansen 15

Morning by Brenda Canipe 16

Lover by G. Burgess Casteel 16

In Time: In Season by Walter N. Dixon III 16

Serenade by Milton G. Crocker 17

Poem by Sue Ellen Hunsucker 25

REBEL REVIEW 31 |

Reviews by Milton G. Crocker, Dr. James E. Poindexter, Miss a

Janice Hardison, The Reverend Richard N. Ottoway, Joyce

Evans, and Jane Teal.

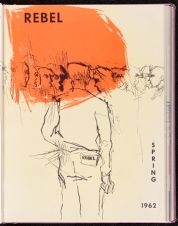

COVER by Larry Blizard.

THE REBEL is published by the Stu-

dent Government Association of East

Carolina College. It was created by the

Publications Board of East Carolina

College as a literary magazine to be

edited by students and designed for the

publication of student material.

NOTICE"Contributions to THE REB-

EL should be directed to P. O. Box 1420,

E.C.C., Greenville, North Carolina.

Editorial and business offices are locat-

ed at 30614 Austin Building. Manu-

scripts and art work submitted by mail

should be accompanied by a self-ad-

dressed envelope and return postage.

The publishers assume no responsibility

for the return of manuscripts or art

work.

oe Siig og 00 tree ae es Sane

ot Lalededesst 2S Se ee SS Ee A A ad od iE Red God gi eS eh oa Oa et nS WKS Coed eaten SE Se EO EEE SE IE PEG PG TEI Gi GPO ci BNET LGN IE Laas eee

CE EE ew Kee ES SEES ae SB ge TER FF: ~: et NE EOE NDEI FT POT NE gC eR ES

are

aaa eI I BTN IG

- eae reeves tee ay, sea _

civ Hire rea

ee ee re eee

BPS Sree ye

Ss

Ba eae sh

Pht ae In nw TR Nec SMES HIRES REVS NSAI IML Bode

OP ruth peer be i a On

ai bi a enn ed arab (

0 TE Ea ea Ti 2a tt OE OL

Frances Gray Patton began her writing career while at-

tending the University of North Carolina. Since then, Mrs.

PattonTs short stories have been published in magazines

such as HarperTs, McCallTs, Ladies Home Journal and the

New Yorker. She has written three books: two volumes of

short stories and one novel. Her first book, The Finer

Things of Life, won for her the Sir Walter Raleigh Award

for the best book of fiction written in North Carolina during

a three-year period. In 1955, she received the award again

for her best-selling novel, Good Morning, Miss Dove. Her

third book, a collection of short stories entitled A Piece of

Luck, was published in 1956.

Mrs. Patton lives in Durham, North Carolina, where her

husband is a member of the English faculty at Duke Unt-

versity.

Interview With

FRANCES GRAY PATTON

Interviewer: What do you feel about teaching

creative writing in college?

Mrs. Patton: I donTt like the word ocreative

writing.? I always feel itTs fraudulent. ItTs as

if you were telling somebody: oGo to. I will show

you how to create.T But thereTs no point in squab-

bling about words. ~Creative writing? is in the

langauge.

ITm never quite sure what I think about it. I

donTt know but what I think that the discipline of

having to write, of having to meet a deadline, of

having to turn out the words instead of just imag-

ining that youTve written them is the best thing

we do. A writer has a lot of imagination, you

know, and itTs awfully easy just to think that you

have written ten thousand words you haven't

written. I heard Mr. Howard Mumford Jones say

once that the trouble with the writing class as

SPRING, 1962

- ee

Syste | "

opposed to a class in the other arts"playing the

piano, for instance, or painting a picture"was

that people go into a class in writing expect-

ing to sell immediately. They will gain more, I

think, if they write completely for their own

pleasure and for their own progress and excel-

lence. I think that the worst mistake made by

any teacher of writing is to encourage the stu-

dents to think that their excellence will be proved

by the acceptance of a story in a magazine. I

think that the writing class is the studentTs oppor-

tunity to learn how to be himself, to tell the truth

about his particular world as he sees it. If he

begins to try to tell the truth about his particular

world as he thinks the New Yorker would like to

see it, as he thinks Playboy would like to see it,

as he thinks The Partisan Review would like to

see it, he is ruining himself. He is killing his

3

particular talent at the beginning. If he has the

nerve to try for his own style"and style is nothing

in the world but a particular way of looking at

things"then I think that he can get a good deal

out of the class.

Interviewer: Do you think that a creative writ-

ing course should be taught from the standpoint

of aiming at a particular group of readers or

Should the aim be toward the universal?

Mrs. Patton: I think that the writing class

should be aimed at the particular in the univer-

sal. I think it should be the individual writerTs

particular approach to the universal problems or

should be directed toward helping the individual

writer express his views of life or perfect his

talent for entertainment. The writing course

should not be directed to any particular group of

people. I think thatTs the quickest way to kill a

talent in the bud. It would make all our litera-

ture dull. The writer has time enough when he

begins to publish to take into consideration the

views of publishers. No matter how hard the

writer tries to keep himself pure, he always has

to remember that that mean old smart editor will

be looking at his work and thinking that some of

his philosophical observations sound naive. ItTs

very hard to struggle against that. Writing is

never quite as much fun when itTs done for

other people as when it is done for yourself

entirely.

Interviewer: Do you think that any writing is

ever done entirely for yourself?

Mrs. Patton: No, but I think there is a time

when it is done for an imaginary audience. The

imaginary audience is often one that will abso-

lutely, entirely take you at your word. It will not

bring in its own prejudices and feelings by which

to weigh the truth that you are giving. I think

that the main question I should want to ask any-

body who wanted to study creative writing, who

wanted to be a writer, is a very simple one. You

canTt ask them, as is often asked, ~~Do you have the

spark?? You canTt ask them that. What do they

mean by having the spark? If they mean genius,

of course, you canTt say. If they mean really con-

spicuous talent, you canTt say. There is one

criterion. Do you have a genuine regard for

words? You may have a genuine regard for

words and you may find out that you donTt want

to be a writer. You may discover that sitting in

a room alone with a typewriter makes you nerv-

ous. You may find that what you really like to

4

OO aia

tN

5 sp ings ganas A DE i RT AIS EE GARE aba Hi

ei ig ca win ag SN cig Yi I ag SG Sc ON i RT EI GD

Be

PPLE S FSA SLAG TA EGA BS SSS STS FEASTS TSCA PETES See ea

PE eg A nF ae ne a MP LIST as a ail -

do is read. If you do, then I say as an author,

God bless you! If you donTt have a genuine regard

for words, if you even hesitate as to whether you

really care about the texture, the subtle differences

between the meanings of words, then the world is

wide, there are many avenues to human happi-

ness, and writing is just not your cup of tea.

Turn to something else. It is almost as simple as

that.

Interviewer: Do you think there is any par-

ticular group of writers today that could be de-

fined as Southern writers?

Mrs. Patton: I donTt think there is a group of

writers, but I think there are a number of individ-

ual writers who could be called Southern writers.

I think so far Reynolds Price can; Robert Penn

Warren certainly can; I think that although she

has gone off into another field in her Light in the

Piazza, Elizabeth Spencer can; Eudora Welty can,

of course, with her wonderful sense of place. I

think that as we have become more aware of our-

selves in the South as citizens of the world, we

have become less peculiarly Southern. I donTt

think there is any group comparable to the Agra-

rians, for instance, writing in the South today.

There was a time when the world at large almost

demanded that a Southern writer be a writer of

local color, but I think that we are now allowed

to think about other things if we want to and are

not immediately considered naive every time we

express an opinion that has any bearing on some-

thing outside our own little cove.

Interviewer: What contemporary figures in

Southern writing have meant the most to you as

a writer.

Mrs. Patton: I donTt know that I have been

influenced by Southern writing in a literary way.

I know a great many Southern writers that I

admire tremendously"Eudora Welty and Kath-

erine Anne Porter, for example. I think Peter

Taylor is one of our best short story writers.

Helen Bevington, the poet, has had a great in-

fluence on me. We are great friends. When we

met, both of us had been writing all our lives, but

neither of us had ever tried to publish anything.

We talked about our work, and we both began to

publish very soon. She is a woman of a very

exquisite sense of taste and form, but I donTt be-

lieve that my writing has been influenced by her

style. I have been more influenced by the writers

of the past.

THE REBEL

eos inca a bape ee I la TS ist ara a le hse BE EBNF SS

ip aud Mas Mada. aK tay ae Sie eRe ae a ee Be Ce SS ES Wi ..

Interviewer: What do you think of Reynolds

Price?

Mrs. Patton: I think Reynolds Price is a very

remarkable writer and I think A Long and Happy

Iife is an extraordinary book. What impresses

me most about the book is that Reynolds has the

ability to create a world into which he immediate-

ly draws his reader. ThatTs something that the

Victorians used to do. That was their greatest

talent; but except for Faulkner in this generation,

I donTt know of anybody else who does it. Faulk-

nerTs world, it seems to me, is a bizarre world"

a world completely out of FaulknerTs imagination.

Reynolds PriceTs world may be bizarre and imag-

inative too, but it is a world of reality that we

are more willing to accept than FaulknerTs world.

We were discussing the influence of Faulkner, as

almost every serious Southern writer has been to

a certain extent, on Reynolds Price. I think that

Faulkner has done this thing so well that it has

almost become a part of the language and the

idiom. I think, however, that Reynolds, like

Faulkner, is his own man and that heTs not going

to remain a prisoner of any sort of style. The

Faulkner stories, ~~Turnabout? and oA Rose for

Emily?, are different in a way from his stories

like The Sound and the Fury. I think that both

Reynolds and Faulkner are independent writers.

ITve read things by Reynolds that did not follow

FaulknerTs circular style.

Reynolds has a story in a very recent issue of

Encounter about an old Negro man which I found

extremely moving. There is not a false move

made in this story. It is simply a recollection of

the past. He goes into a book store in Oxford and

buys a post ecard on which there is a picture of an

Egyptian emperor. The profile reminds him of

nothing so much as this old hanger-on, this old

Negro man, who simply wandered around and at-

tached himself to the family. It showed a great

deal of feeling and understanding.

I think Reynolds may well be one of the most

important writers that we have in this country

or even more than in this country. He is tremen-

dously admired in England. He was taken up by

Spender when he arrived in England and his

talent was recognized immediately. HeTs very

young yet. We'll have to see what urbanity does

to Reynolds as he sees the world.

He had a remarkable experience with his first

story. It was called oA Chain of LoveT and was

about Rosacoke, the heroine in A Long and Happy

Life. ITm sorry that it is not incorporated in his

novel because it really does add another dimension

SPRING, 1962

to Rosacoke. Reynolds wrote this just as he was

graduating from college, and he was to be a

Rhodes scholar the next year. He took it to New

York to an agent and the story was accepted by

Atlantic, HarperTs, and one or two other maga-

zines. Reynolds refused to shorten or change it in

any way. I think it took a lot of nerve for a

twenty-one year old writer with his first story to

do that. He went to England and it was imme-

diately printed in full in Encounter.

Interviewer: Do you think that Southern writ-

ers have a social responsibility to push integra-

tion? |

Mrs. Patton: No. Southern writers are good

as Southern writers but they must forget some-

times that they are Southern. They must recog-

nize that there are other areas of existence in the

world, particularly if they want to do something

for the Negro. What they ought to do is to start

writing about the Negroes as people, as human be-

ings, with the faults, virtues, limitations, and op-

portunities of human beings instead of as black

angels that have been downtrodden and have had

_ their wings clipped and who, if it were not for old

Southern colonels, would be flying around in the

blue ether shedding sweetness and light upon all

of us. I think it is belittling to a person to cast

him in a stock role as an angel or clown or devil.

Negroes are not any of these; theyTre human be-

ings. That is the only legitimate way in which

they can be used in literature. I think that push-

ing integration is not one of the proper duties of

a writer unless he feels that he personally wants

to push integration. Paul Green does feel that.

It is one of the great motives of his life and so itTs

fine for Paul Green. I think, however, that it is

not proper at all for someone to take on as a duty

something about which he has no strong feelings.

We can do ourselves infinite harm by allowing

ourselves to be irritated to the point of an imag-

inary paralysis by people who are militant about

the Negro problem.

Interviewer: Do you agree with Lionel Trilling

~ when he said recently that no writer can be a

mature critic unless he has an urban intellect?

Mrs. Patton: I think I would disagree with

Mr. Trilling. ItTs the old fight still going on be-

tween the city and the country, the city slicker

~and the country bumpkin. I think the city man

who does not understand that there can be great

intelligence in the thoughtful country man, par-

ticularly in the country man who leads a sort of a

5.

ioe

i Eg. UF St ees we HS est eee tog ire reas peel Ei ge z : ea ie See on a PSR PEE EIS Oi Pi OS SOE EE EE PES 2 eS EPR EIT AABN AB IE LETT AAO IE RR. GE GRO OE LIU ALA REN ng ag Cig a SP ~

5 ee EL ee {SRS EERE SWRA OE Ed A aE SOS eh eG ee RSE BTS AR SES Sh ee RES 6S SARE Mh rintine Ss AB Sg SORES SS SAE RE ESE a EE OES BO Be COREE Se OTE BEST FS SS TAS PESTS AES TEES $s TAR SES TET © 3 skew ee wseee eka.

i oe

ce

Bs Sa 2 SOR

ie

ae.

wanes

a

+). SEER

LO Bagh ph gE ina belt AALS IS AA et E AE AB AE CAE CTIA Hs

patrician, intellectual life, is missing a great deal.

As a matter of fact, I think that urban people are

likely to be more provincial than people in the

provinces simply because they do not know they

are provincial. TheyTre victims of a mass provin-

cialism and canTt see the woods for the trees.

Interviewer: Do you think that the majority of

our contemporary writers, particularly some of

our playwrites, are attempting to deal exclusive-

ly with the disaffiliates in society?

Mrs. Patton: If the Broadway plays are true

reflections of our society, I think that our society

is very sick indeed. Perhaps the wars and trou-

bles weTve had have made people suspicious of

ordinary life and have made them demand the

bizarre and distorted. Perhaps itTs a matter of

needing kicks. Then, of course, we have begun to

realize more about the individual unhappiness of

people in society. For example, you can be lonely

in a crowd.

Some of the preoccupation with disaffiliates

comes from pity, from a longing to understand

lonely people, and thatTs good. I think that to

consider them typical is a distortion of the truth

and is rather bad for society. It does an injury to

our thinking.

Interviewer: Does short story writing require

any particular aptitude as contrasted with novel

writing?

Mrs. Patton: The form of the short story is

very fluid. You can do almost anything with it.

It can be a familiar essay; it can be a straight nar-

rative; it can be a mood piece; it can even be

propaganda. The technique of the short story is

rather like a poem in that each word counts. You

aia a meee

: GAEAERD OTST SSD SLATS SSATP EE BESS US STS EELS TS PST E TFS PSS ISIS IS ESI

eG PR PES LES EIR GLP AP Sig EP ED A AEE ADA BE Ei Be RA SOA lene 5 hg POA Pm al ge ae ES

simply do not dare make a slip in a short story

because the form is brief. Everything you put in

a short story must have a meaning and a purpose;

whereas, in a longer work of fiction, you can

write several chapters that just take up space

without really interrupting the flow of the work.

I think the form used in writing a short story

is very distinct from that used in writing a novel.

In the short story, it is very difficult to have any

real character development or change simply be-

cause of the brevity of the story. It does not

cover enough time for change and development

to occur. Things so rarely happen in life that the

short story writer can reveal. The short stories

can reveal hidden qualities in a character; but,

essentially, the hero of a short story is the same

at the end of the story as he was at the beginning.

Of course, all of these rules are to be broken. I

say that some things do not happen in real life;

they do happen. We all know of cases of sudden

conversion. We all know of boys who sit down

and read a book in which they suddenly see some-

thing that changes their lives. We know of peo-

ple who go to church and suddenly find their whole

course of thinking has changed. This happens so

seldom, however, that it seems sentimental to do

itinastory. Ina novel, there is a passage of time

and various influences of life coming in on the

character. It is logical that the character can

change in the novel.

Interviewer: What do you feel is the most grati-

fying thing about being a writer?

Mrs. Patton: The most gratifying thing about

being a writer is that morning after a long dry

spell when suddenly God seems to be on your side

and your subconscious is working well and words

tingle on your fingertips.

iB Ee Pile me Nc ONO Oa i i ERE NNN BENT ETD

Siig cies SG icin Bt en alae Lee eel al PES OS a eS a as

THE REBEL

a ee

ee. |

an .

| See Apee

asi we i

oy P . a

A TE ?"?~

juste ser see Se ©

| AIN'T THOO YIT

a monologue

HARRY C. WEST

Enoch awakes with a start. He opens his eyes

wide and looks around.

Hunh? Whozzat? He sits up in bed. His eyes

come to rest on a spot in the center of the room.

Whut you want? Frightened pause. Me? Whut

you mean? You donT need me. He screws up his

courage. You got no call to come lookinT me.

You jusT well 2gT on anT git someTun else. He

swings his legs to the floor, as if to get up. Then,

thinking better of it, gets back on the bed. WonT

do no good to wait. You jusT well gT on anT lemme

~lone. He nods at the door. DereTs de doT. He

pauses, scrutinizing the visitor. You jusT gone

stan dere, shakinT you haid?

How long you figger on stayinT? TF you gone

wait foT me, you got a long wait. I got things to

do. I cainTt go wid you now.

Whut? You ainT got time to wait? Well, me

neidder. He points. DereTs de doT.

He tries another tack. I tell you whut, why

donT you jusT gT on anT leave anT come back agTin

latuh, lak nexT yeah or so? DassTll be bedduh foT

SPRING, 1962

bofe of us.

He jerks his head toward the door, listening.

Hey! You Shawty! Stop Tat bahkinT! He gone

leave in a minnit.

Hunh! You isnTt? I thought it Tuz settled. I

done tole you it best you come back some udder

time. I tell you whut, nexT yeah Tbout this time,

ITll prolly be thoo and can go wid you. Right now

I got me too many things to do. Gotta fix dis place

up foT when Mistah Ed come back.

He gets out of bed, stands, and looks out the

door. See out dere? Dat fielT on de udder side

de house"whutTs lefT 0T de house"I Tuz gone plow

it up today. Got me some seed whut wuz lefT fum

when dem mens fum de Nawf come thoo heah.

Dey neah Tbout buhned evuhthing. TCept I saved

me some seed, dough. We got to git us some cawn

plannet so we kin eat. Miss Callie fum in town

brings me some food now and agTin. She Mistah

EdTs sistuh.

Yeah, I got me too many things to do raght

now. TF I Tuz thoo, ITd go wid you in a minnit.

7

{See RSE SA a ES EGRESS Eh wed SG eS Sh oR eG a eG BTS RnR ESE eT niet Se eS SESS LASSE Sheen s nets S RES SSeS eh a eae ES BSED

eo

"

So) Sees

a 1 Oa

We

rome

ES

a SR

ony ~

GRY | Bai gi gewaikwiaad

But as it is"

He breaks off, irritated that the visitor wonTt

understand.

You whut? Whut... well... uh, siddown, den.

He motions to the rocker. You kin wait while

. while I say Tbye to ole Shawty. He shuffles

to the door.

You Shawty! CTmere. TAtta boy. He lets the

dog in, then stoops to talk to him. Shawty, dis

man here, he say I got to go wid him. I reckon

dat leaves you heah to take keer de place. Now

I want you... He realizes how ricidulous this

is, and shuffles back to the chair.

How come you think you kin come in heah anT

bust things up lak dis? Wipe dat grin off you face!

Even Mistah Ed nevah done dis. He aw-ways

axed me to do things foT him. He never busted in

anT said, oEnoch, you cominT wid me.? Nossuh.

He aw-ways say, oEnoch, ITse gone hafta go

to town. Hich up de carrich foT us anT we'll drive

in.? AnT I say, oYassuh.? JusT lak dat. AnT he

owned me. Do you own me?

He looks at the chair, then gets the idea.

Well . . . conceding I reckon you do, in a way.

Awl of us. But you got no call to come Tfore a

manTs thoo. He ruminates on this. You evah

seed two dogs togedder? Well, cainTt nothinT git

dem apaht tell dey thoo"less you thTow cole

wawtuh on Tem. Ha! Likes this idea. You de

man whut runs arounT wid a bucket oT cole wawtuh

foT evuhbody, ainTtcha? Yeah, dass whut I

thought. Ha, ha, ha!

Well, I ainT thoo. Mistah Ed ainT thoo neidder.

AnT you kin quit noddinT you haid. You think

he thoo jesT Tcause oT whut happened to de place

heah? Naw.. fah fum it. You donT know Mistah

Ed. I wuz hisTn. We growed up togedder. He Tuz

bawn jusT two yeah aftuh I wuz. Yeah, he fah

fum thoo. I Tmembers de time when de herrycane

come up de rivah. Well, it blowed de roof off de

big house and de bahn flooded neahbout to de

haylofT. You think he give up? Naw. Not Mistah

Ed. Why"

He jerks his head back at the chair, as if rude-

ly interrupted.

DonT innerupT. I ainT thoo wid what I is tellinT.

You kin wait a few moT minnits. Anyhow, he

pitched raght in wid us nigguhs anT we fixed de

place up lak hit wonT nothinT happened. Dat tree

stomp outside de doT is lefT dare to Tmind us of de

stawm. Dass de onliesT thing lefT. Mistah Ed

never would let it be took up.

Aw, siddown. You ainT got nothinT else to do.

Heah. He fumbles in his pants pocket and comes

up with some rope tobacco. Have some Tbaccer.

8

ri inca 7s cil is ip ea i ii inn a (Bi Sn Rc MORITA RT GAGES EL HOOT TN TS

Sete la Ge ee als SS RTA ER Dare aa ton ae a RR ne OE Se Sy

aie

a

"" Se ee oe Fs kao eae *Eeg, ~

SEES POLIS SD PD LSS SP SDAA Sao S eT LOS BI SESS STS EEL SES ESTAR FSIS IESE rie eG ae

No? He cuts himself some and puts it back in his

pocket. He keeps the knife in his hand toying

with tt.

Guess you ainT nevah seed ole Marse Quillum

chew Tbaccer, did you? He Tuz Mistah EdTs pa

y know. He 1s stalling for time now. Back

when I Tuz jusT a young sprat, he uster give me

money anT I'd go inta town and git Tim some. Ole

Missus, she didnT lak him to chew, so heTd come

out to de fielTs to sneak Tim a chaw. Mistah Ed,

he tuk ovah when Marse Quillum die. Spits.

Oh, you Tmembers when dat wuz, huh? I Tuz wuk-

kinT dere as Mistah EdTs pussonal nigguh den.

Mistah Ed chewed too, aftuh ole Missus die. She

allus thought it un-dig-nee-fied, low and coTse, lak

nigguhs. We did have two or thTee low anT coTse

nigguhs heah. Dey de ones whut lefT when dey

freed by Linkum. TKnow, dey say PresTdent

Linkum de greTtesT man evah live. You take Tim

too? Whut you think"you say he greT? Hah!

No greTterTn de resT of Tem, hunh? Well, dass

whut I thought. He jusT a trouble-makuh, fah as

ITse concerned. I mean, he say us nigguhs is free.

Free to do whut? he spits. Free to spit our

"*baccer anywhurr? Sho. Dass whut he say. AinT

none of it. Free to git in trouble is whut. Whut

he know? JusT sittinT up dere in WashTnon lak

God anT say, oDe nigguhs is henceforewith free.?

Hah! Whut he know "bout freedom? ManTs got

to be tied to someTn. Man widout roots some-

whurrs is bound to git in trouble. AinT dat raght?

Cain you jusT Tmagine me in Baff wid nowhurrs

to go? Who gone hire me? Who gone give me a

job? Whurr I gone live?

How kin I builT me a house? Dass whut I

wanna know. Naw, dem udders lefT, but I hadda

stick by whut I knowed. He think he God and kin

say I seen all nigguhs beinT treated lak animules.

But he ainT seed how Mistah Ed treated me anT de

resT dem nigguhs. Yeh, he jusT good to us as he

kin be. He gone come back. It gone be de same

aftuh he gits back. Quit shakinT you haid. ItTll be

de same. Ole Marse and Mistah Ed bofe knowed

I Tuz a good nigguh. | |

See why I cainT leave now? Dey been good to

me. I gots to stay TrounT heah anT keep things goinT

tell Mistah Ed come back. Miss Callie fum in

town say I got to too. She even brings me whut

food she got, too, fum time to time.

I been tryTna fix de place up besT I could, since

dem mens fum de Nawf come thoo heah and buhn

evahthing. He points to the plantation house out

the window, on the hill in the background.

See de chimbley? Dass awl standinT. De col-

yums is lyin up dere now lak dead nigguhs. I

THE REBEL

Poms Barwa wa TS Sie Se s e LSS ES SS SSS

SSS |

done cleaned up de besT I could. Mistah Ed, he

gone be home quick as he whups dem Yankees.

Hope he gits dem mens whut come thoo heah

buhninT evahthing. Dey even tuk my gal"Maud-

ieTs anT mine. Huh name Lula.

He rubs his face, as if waking from a dream.

Well, Shawty, leTs you anT me go anT hitch ole

mule up. We gone git that plowinT done. As if

taking for granted that the visior will leave.

You kin wait heah if you wants to, Suh. But I tell

you, you got a long wait. We got to git dis done,

fust. He makes as if to go out. He stops. He

looks back at the chair, listening as if in disbe-

lief.

You lie! You lie! You cainT fool me. You

tryTna fool me into goinT wid you. Dass whut you

doinT. Mistah Ed... Yeah, he gone come back.

I know he is. He told me when he lefT dat he

cominT back. I got to get things ready. HeTll be

back soon. He sits on the bed in bewilderment,

SPRING, 1962

trying to convince himself that Mister Ed will

come back.

Yeah, weTll fix de ole place up again .. . lak

it usta be, when he come. Yeah, I got me plenny

of things to do. No time now to go wid you. HeTll

*spect me to have things ready foT Tim. Who else

can do it?

CTmere, Shawty ole boy. He pets the dog, then

takes the dogTs head and speaks into his face.

Mistah Ed gone be proud of us. We'll jusT go out

anT git ole Wheemy, git her hitched up anT plant

us some cawn. Plenny oT wuk to do.

Here he begins settling back on the bed and,

by the last few sentences he is lying flat. I ainT

thoo yet, suh. Not by a long shot. You jusT well

leave now. I'll jusT lie back heah"git me some

resT foT we git out in the fielTs. He closes his

eyes. See dat he leaves, Shawty boy. You tell

him how we ainT thoo yit. ITm just gone resT mah

eyes a minnit anT

pias Not)

1 +

peer aly Z

: ae

~ See ab 7 {7 ,

Ns (((f oe Bais

ay oil ,

\ a 47 2

~ ewe

4 T Nass 7

, aye ea

sa

'

PLIST ES {Se ETRE GAG SR SEE SRE e Eee AG eS Sh oR ea ae E BSE ane SESE e COS RES OE FE ASSES gS Fay Ss DS SESSA SS SE Ss EE RES SERPS EES :

ga a

ery Ss

LOVE

Pith

incl

>

Oe

a4

U

7)

=

""

©

"

Lene!

a4

S,

lull

NM

eta

a i

_

eae

a ii: ee en

ee SA

2 ines. Se

EE

l. was on one of those hot sultry Sunday after-

noons in July of 1935 that I pulled up in front of

the rambling structure of a farm house in Provi-

dence Forge, Virginia. The sign located at the

entrance of the long dusty lane, which I had just

driven up, had said that boats could be rented

down here and thatTs exactly what I was looking

for. Yes sir, just to get out there on the Chicka-

hominy and get a couple of hours of bass fishing

in before sunset was all that I wanted. Climbing

from my car, I approached the front door to the

house. After knocking and calling several times

without receiving a response, I wandered around

to the back of the house.

oAnybody home around here?? I called, begin-

ning to become annoyed.

Still there was no answer, so I thoughtfully

turned my gaze towards the river as it lazily

moved by. I suddenly became aware of someone

standing near the corner of the old house, watch-

ing me. When I swung around, a bedraggled

figure in faded blue-denim overalls wearing a bat-

tered straw hat confronted me. Much to my

amazement it"or she"was a woman.

oWhat can I do for ya, young fella?? she in-

quired, stepping from the shadows.

oT__uh saw your sign by the lane and thought

ITd rent a boat for the afternoon.?

oSign ?"Aw ya mean that ole sign Sam put up.

Lawd knows, son, he put that up two years ago.

My SamTs dead-an-gone now, but I still got a good

boat-er two that I can rentcha. AiminT on doinT

a mite oT bass fishing ??T

oYes mam. Could you give me any tips on some

particular spots I might hit carefully?? I asked,

giving her a playful wink.

~oWell"les see,T she paused. oI habenT talked to

none a the men folks rounT here for a spell, but I

can tell ya one place to steer good anT clear of

ifin unless ya wanna getcha self shot at!?

~oWhereTs that??

oPlace down the river there Tbout two-three

miles called McCravenTs Cove.?

oWhatTs there that should keep a man away?T

oWell"lITll tell ya,? she started as if preparing

to let me in on a choice piece of information. oYa

see nobody rounT these here parts knows how it

all come to be, but bout nigh ten years ago some

awful ole man bought up Tbout five acres of land

down on the river. Seems like he moved on the

land anT built hisself a cabin anT been back there

ever since. Course he comes out ta go upta main

2 92

Providence Forge to do his tradinT.

SPRING, 1962

gue SSSA G+ St Ed.

ten ae EEL ERED LLL E LED LG ERLE EP EDD TTI PLL LE I LCE PIE LAE ITT CE cae ane eared pen te oy Hs

S = = a TRS Re _ SS RSS AE Pa ES SERENE F Se eS PE Bi DE EE Mey SF RATS DEE Se ey

oSounds like an ordinary old hermit to me,? I

broke in. oITve always been interested in such

odd characters.?

oWell, mister, he ainTt nobody to take a likinT

ta. I seed Tim up-an-down the river before anT

he ainTt nothinT but a filthy, nasty ole coot. Looks

just like a wild man"vwith his dirty long red hair

anT beard. Dresses hisself in skins anT hides"

must stink ta high heaven.?

oAre the people around here afraid of him?T

I questioned, beginning to become slightly inter-

ested.

oAfeard of Tim? No folks ainTt afeared a

McCraven, but they donTt go a snoopinT rounT his

cove or land Tcause he donTt tolerate people on his

land. George WallTl tell ya that. Old McCraven

caught Tim in his cove just lookinT rounT and he

threatened ta shoot Tim ifin he didnTt get out.

There been others too. Ole coot even took his

pack aT wild hounds after a bunch aT boys who got

on his land.?

oWild hounds??

oYeah, some say he keeps Tem penned up back

in there ta keep folks away. I tell ya, mister,

donTt go near that place. The ole foolTs crazy"

just plumb crazy!?

I finally managed to rent one of the boats from

the old lady and get started on my fishing. I was

taking it kind of easy and felt relaxed while cast-

ing around the cypress and half submerged logs

of the river. However, as I slowly made my way

down stream there was just a little feeling of

anticipation in the back of my mind. Somehow,

what the old lady had told me about this character

McCraven interested me and I found myself want-

ing to see him. Of course, I thought, she had

probably just built up a real good story about

some poor old wretch that has been seen in the

vicinity a few times. In fact, this fellow Mc-

Craven might not be anything more than a legend-

ary character, who was altogether non-existent. I

wanted to dismiss the whole thing from my mind

right then, but somehow I found it impossible to

do.

About an hour later, I crossed to the other side

of the river and I came upon the narrow entrance

of a cove, which wound back into a dark interior.

Could this be McCravenTs Cove? It seemed to fit

the old ladyTs description of the cove, so by my

calculations this had to lead to old man McCra-

venTs home back in the woods. It was only now

that I realized to what degree my curiosity had

engulfed me. I somehow had to see this barbaric

1

"

Poa oe aS

= sopeesSiGige ua»

i

*

oa icacte casper ines

~Semana ems werner nT StH

EAP RESIS UNIS ORAS

eonre se prion pein

aan RR RCAF Fm

DCE Be ROT LR Se

o Pe pise ei.

o Stale

Ta, ~Sag : 3

Py OO OO

creature for myself. If what the old lady had said

was true, I would be risking my life. However,

I decided to work my way up the cove and see

where it led. So I quietly dipped my paddle into

the murky water and guided the blunt-end skiff in-

to the cove. I made my way forward into the inte-

rior. Tall clusters of cypress trees, along with

bushes and never ending networks of creeping

vines cut off almost all of the afternoon sunlight

which tried to filter through the entanglement.

Suddenly a big long-legged crane swooped up just

ahead of me with a tremendous flapping of his

wings, breaking the haunting stillness. I rounded

the first crook in the cove just in time to see the

sinister form of a large water moccasin slide from

a log and make his way into the thick bushes.

The whole cove reeked with the scent of death.

Bloated turtle intestines clung to half-sunken logs

and trees about the area. oDamn,? I thought out

loud to myself, ~~when the old man chose this spot

back here to get away from humanity, he really

picked the ideal place.?

A few moments later I rounded the last bend in

the cove and there it was, right in plain view"

the old manTs cabin. I simply sat there with the

paddle across my knees, staring at the structure,

while drifting closer. It seemed to be compact,

made of hewn logs, which were chinked with mud.

There was a stone chimney at one end and there

seemed to be a thin wisp of smoke curling upward

from it. Abruptly my thoughts were brought to

an end by a movement in the bushes on the sloping

bank. Then I saw him. I knew immediately that

I was staring into the flashing eyes of old man

McCraven. A more barbaric creature I have

never seen. There he stood, dressed in hides taken

from animals. A shock of flaming red hair curled

from the neck line of his hide shirt. This, in turn,

was matched by an unkempt red beard, and flam-

ing natural curls which hid his ears completely

and came down thickly to the base of his neck.

Yes sir, he was exactly as the old lady had de-

scribed him to me, and as I sat there gawking at

him the boat drew closer to where he was stand-

ing. He moved another step closer and stood at

the edge of the bank, standing tall and proud with

that same look of barbaric hostility glistening in

his eyes.

oYa ainTt got no business a snoopinT rounT up

in these here parts, stranger!? he barked out, sud-

denly raising a big double-barrel shotgun to his

side and leveling it on me. oNobody got no busi-

ness back here but me! Now clear outn here anT

stay out!?

12

ae

T ? meee?

? ail Sa ee SRI E CATS TS PLES =

sg ea Ie ESSE LE EEE DEC OIE OS ee

SPADE LASSE Ie a ee rer eo ae ee

oMr. MeCraven I"

I never got a quarter of the way through with

what I had intended to tell the old man, because

he became so infuriated with me that he discharg-

ed one of his loads of shot not two feet away from

the boat. That was all the convincing I needed for

the time being. I swung my skiff around and

headed out of that cove. I glanced back only once

and then I caught only a glimpse of the lone figure.

He was standing and watching, making sure that

I left his domain.

The sun was sinking low on the horizon as I

drove slowly up the rutted lane from the old ladyTs

farm. It had been quite an afternoon with per-

haps a little more adventure than I had antici-

pated.

As the week dragged slowly by I found my

thoughts turning more and more to the strange

old manTs choice of such a sheltered existence.

Was there any ulterior reason behind his obscure

activity or was he just a loner? By the end of

the week I knew only too well that my curiosity

had gotten the best of me, so when Saturday came

I left the crowded streets of Richmond and headed

once again for Providence Forge.

With my curiosity aroused to such a peak, I

had a lot of questions that needed answering and

I planned to get those answers. I spent my entire

weekend finding out about old man McCraven,

and meeting some of the people who lived around

Providence Forge. Of all those individuals I talk-

ed with, however, the most informative was Pete

Tyree, the gray-haired proprietor of a general

store. I had been told that Tyree was the only

man in Providence Forge with whom McCraven

had ever dealt, so I went immediately to his store.

Inside it was a typical country store. The shelves

were cluttered with goods of every kind and de-

scription. Stretched out on the floor in a spot of

sun was a bony hound dog and there was one

very dirty yellow kitten playing all around the

place. I walked slowly over to the man behind the

counter, introduced myself and inquired if he

might be Mr. Tyree.

oYep,? he replied, ~oo~what can I do for ya, mis-

ter ??T

oTm looking for some information about a cer-

tain fellow around here that lives back on the

river,T I started. ~o~They call him McCraven.?

ooMcCraven in some sortaT trouble?? he asked

suspiciously.

oNo"no trouble. I just happened to be making

a study of your area here around the Chickahom-

iny and heard about him. He seems to be a pretty

THE REBEL

ee are sik i i ee tai SN a a (Bi SG Oe NAR eA

oat a fanieg Sci icine Ra ae Tianhe iho ae

LA RRR ABO OOOTIINAOIIOI OOOO EARIAAARAA RARE AE AIA PAN

~ a = ~ - a

: a a aS 5 ik Ss ne nse ee ene ne

2 = Se ee Re aS ae ee eS

a i as a ren 8 REE RO AOS piTs 2 »

FSS SI Sak EE

= aia ahs

ae ae

ac ae

~a TT ag

as ~ gf

va eee : mee siehinazntis

J * Pre

ag nd eto ee

interesting character and I thought ITd just get a

little factual information on him. You know,

you've got quite a legendary region around here

and this McCraven fellow adds to it even more.?T

My words seemed to create just the effect on

Tyree that I wanted. Immediately he seemed to

lose all of his suspicion towards me.

oWell, mister,? he said, coming around the

counter, ~o~pull up one of them chairs over there in

the corner and IT]l tell ya what little I know Tbout

ole McCraven.?T

Both of us seated, Mr. Tyree filled the beat-up

stub of a pipe and slowly placed it precariously

in the side of his mouth. Drawing a big kitchen

match across part of the little pot-bellied stove

beside him, he leisurely touched its flame to the

tobaceo. Large clouds of smoke engulfed him as

he drew the flame down into the pipe. Meanwhile,

I sat patiently waiting for him to begin.

oSo ya wannaT know Tbout ole McCraven, do ya,?

he began. oWell, guess it musta been Tbout 1925

that I first laid eyes on Tim. TTwas in the summer

as I recollect. He walked in here anT made me a

danged good offer for some land I had back on

the river. Well I solt Tim the land"five acres of

it. Also solt Tim a buncha goods in the store here.

He sure wonTt a very talkative fella"never has

been. But before he left we made a tradinT deal.

He was ta bring me some of his pelts that he got

each trappinT season anT I was ta give him certain

goods in return.?

oT see,T?T I returned, as Mr. Tyree paused. ~So

you were the first to know that McCraven planned

to live back in there on the land and trap.?

oYeah, I reckon so. Corse after folks seen Tim

up-an-down the river a few times they begun ta

talk. Then heTd show up here every three or four

months. Always come at night. But now heTs

completely changed hisself.?T

oChanged in what way?? I interrupted.

oWell for one thing heTs done growed a beard

anT let his hair grow out Ttill it partially covers

his ears. Ya couldnTt see those horrible scars and

purple stuff on his face no more.?

oScars and purple stuff??

oYeah, first time he come in here ya could see

this buncha purple birth mess all over his face

and he had a whip to his face or somethinT. He

was the most horrible lookinT thing I ever seed.

But later ya couldnTt see none a that mess cause

a the long hair anT beard heTs growed over it.

Folks rounT here said he looked just like some

sorta wild animal anT they was plumT right. When

heTd come a stalkinT in here he looked just lika

SPRING, 1962

SSSA Awe

-my carefully laid plans.

big mean ole hairy bear. AnT since he started

takinT that ole three legged deer hounT with Tim

wherever he goes, he even looks wilder.?

oSo he has a dog that goes with him,? I replied,

taking down mentally every detail that Tyree

brought out about McCraven.

oYeah, but he ainTt got but three legs, so he

couldnTt be of much use.?

Mr. Tyree had told me just about all he could

about McCraven, but the information he had given

me had been my best collection of facts so far and

so it was with a feeling of great accomplishment

that I left the store.

It was in the first week of August that I took

my vacation. I had had this one week of leisure

completely planned for a long while. So on the

Friday afternoon which marked the beginning of

my free time, I left Richmond and once more

drove to Providence Forge, where I rented a room

for the night. The following morning I was up

with the crack of dawn and after eating a hearty

breakfast, headed for the river to rent a boat.

This wasnTt to be any leisurely fishing trip, for I

was still concentrating on old man McCraven. On

this trip I wanted to satisfy my curiosity about

him once and for all. Was he simply a plain her-

mit who wanted no one meddling in his private

affairs or could there be something back in the

cove that he was hiding? In talking to different

individuals on my trip the previous month, I had

found that the majority of the people felt that

McCraven was hiding something of great value

or either hiding out himself. The people seemed

to have very vivid imaginations about the old

recluse. All of these thoughts ran through my

mind as I paddled slowly down the Chickahominy

in the cool morning air. The mist on the river

drifted lazily with me, creating an eerie effect as

I made my way towards the cove.

About an hour later I reached my destination

and paused before entering the cove. I had come

this far and had done some pretty extensive plan-

ning, so I couldnTt back out now, even though my

mission would place me in danger. No, I had

come for a purpose and I was going to carry out

So without another

moment of hesitation I guided my skiff into the

cove and silently proceeded up the winding inlet.

Upon reaching a point where the banks were of

a low level, I quietly removed my equipment from

the skiff. I wasnTt taking any chances on ap-

proaching McCravenTs cabin by boat, in plain

view, for I could not let him know of my presence

if I was to discover anything. So now, securing

13

ere aa = = te See istiniséGiateitieatece= =. Sy ate a 2 : = z : : ~

a SEG RSG SUSAR eGo niet et at thet scecsGeSeceseseesnenedcnes: a :

S ; i a es : ee

. " , Ut ERP EER RSs aa gee ATES

whe bisa oiiwssx:

ae

By

ten

ee ;

merece

aS

Pitas Sik. uate

- Sh ae on tether

BS

= ee

= Sp ee a ee er ee cE

gh iia Ba AEE LEE DEDEDE LALLA AALS,

Poa epee eS Spe EE Be Se IT

my boat, I took great pains to camouflage it. When

I was satisfied that it could not be seen by anyone

either leaving or entering the cove, I shouldered

my gear and began to make my way towards the

location of McCravenTs cabin. The sun was high

now and its hot rays made human existence in

the humid swamp almost unbearable. oMy God,?

I thought aloud, plodding through the thick under-

growth, ohow does the old man stand it!?

After a considerable length of time I edged up

to the clearing where McCravenTs cabin was lo-

cated. I crouched down quietly and relieved my-

self of the supplies which I had been carrying.

I nervously fingered the double-barrel shotgun

which rested across my knee as I watched and

waited in the brush. There did not seem to be a

sign of human life on the premises. But the old

man might be anywhere around here, I thought,

so ITd better be even more careful. Gathering up

my equipment, I proceeded to work my way to-

wards the back of the cabin, taking great care to

keep myself concealed in the underbrush that sur-

rounded the clearing. In back of the cabin stood

two smaller structures. They seemed to be stor-

age houses of some sort"or could one of these be

a pen for McCravenTs wild dogs, I thought, with

a chill oozing down my spine. I had plenty of

time to find out what was in the log structures

though, and right at this time I was more con-

cerned with finding a suitable campsite nearby for

my headquarters. Soon I came to a spot down by

the river which offered much cover, so it was here

that I decided to pitch my tent and make camp.

After eating and resting, I renewed my explora-

tion of old McCravenTs land. I moved about from

place to place watching carefully for any signs of

McCravenTs presence. But throughout the course

of the afternoon there was not a single sign that

the hermit was to be found anywhere about the

area. It was aterribly weird feeling not knowing

where the old man might be. He might be any-

where, lying half submerged in the reeking swamp

vegetation, with an ugly snarl on his red bearded

face"just watching me all the time. It scared

me even to think about it, even though I had a

shotgun loaded with buck shot. I watched and

waited patiently.

The time had droned by and when I looked at

my watch again it was four p.m. I had become

quite restless now and I decided to take a calcu-

lated risk. It would not take long to slip out into

the clearing and check the two log structures be-

hind the old manTs cabin. I had to do something.

So far the day had turned up nothing to enlighten

14

DE ee

aK : es a fe a ss igs ifs aazasin tance

ks i Us A AS TES ISS

gs"

£ERTSSO LS SEL SS

NP rer Be eh eb dl eh Ph a

"or sea SS Se Sr i ee a

Sa a Pe Fp ee en Tle comalianed :

Fe ee ek ase eh Fa Pil pe Pa POE LANG AEA ADE

me about McCraven, and perhaps by checking

these I might find a few answers. So with a firm

grip on my shotgun I advanced as quickly and

silently as possible towards the first of the two

structures. Upon reaching it I was glad to find

that the crude door was simply latched by means

of a movable wooden bar. Glancing around to see

if my presence had been detected, I quickly pulled

the bar out of position and let the door swing

open. A stench immediately struck me and I

heard vicious growling and snapping sounds! A

pack of dogs lunged out of the darkness at me,

the lead animal baring flashing white teeth, which

dripped saliva! As I jumped to the side, the

lead dogTs lunge was stopped by a heavy chain.

Quickly I slammed the door and shoved the wood-

en bar back into place. So McCraven does keep

wild dogs"why he must be crazy!

My thoughts were suddenly interrupted by a

movement off to my left. I swung around rapidly

and there he stood"old man McCraven. His firm

mouth was drawn tight and the grimness of the

situation was reflected on his weather-beaten face.

His eyes were narrowed to flashing slits and the

thick, bushy red eyebrows were furrowed as if in

some evil concentration. There was the big three-

legged deer hound that I had been told about,

standing close to his masterTs side, as if awaiting

obediently some command. All the while the wild

pack of dogs, closed in the wooden structure at

my back, were snarling and growling. Just at

this moment the back door of the cabin opened and

there appeared in the dourway a little blond hair-

ed girl. She coulnTt have been over nine years old.

I stood dumbfounded staring at her. No one had

mentioned anything about a little girl; my mind

raced. Could she have something to do with why

McCraven kept people away from his land? She

began to make her way outside in an unsure grop-

ing manner. Of course"it has to be, I reasoned,

sheTs blind"the childTs blind.

~oGranpa,? she called out suddenly. oGranpa, is

that you? I cTn hear your dogs"are ya with

"em ??

Without so much as a word the old man snapped

his fingers to his big three legged hound. Imme-

diately the dog responded by going over to the

child, mouthing her little hand gently, and leading

her over to his master.

oGranpa, did ya just get back from the river??

she asked the old man, holding her arms out to

embrace him.

oYes, Susie, my dear"but Granpa wonTt be

leavinT ya again for a long spell. No, darlinT, not

THE REBEL

Sages ee = are Se ee

ae a = fee Se oe San a >} Se ae Se BS Me BS =

SAS = = Se ee Tea REALE SS SS eS

a a a ic a ibe san aaa Sees a Ona EMI ye oa é.

Fees eS BE Sa a Rae aS Ow a TE NS

ae _"~

a P > yee ee

pind sree

for a long time, cause itTs a gettinT so a man canTt

leave his own land without folks a sneakinT in on

it. Yeah I member ya, mister,? he said, turning

his gaze once more in my direction. ~~Seems I re-

call havinT run ya offinT my land once before, but

that didnTt nary stop ya.?

McCravenTs little Susie sensed my presence

now, but she displayed no sign of disturbance.

She stood blandly by the old manTs side, who had

now risen to a standing position in order to deal

directly with me.

oYa had ta come back a pryinT inta our lives

again, but this time ya dug a liT] deeper and have

laid yourn eyes on my Susie. Lemme tell ya some-

thinT though, mister"ever since I brung Ter to

my home here at the cove, I cared for Ter good anT

proper like!? he rasped out, his eyes blazing. oShe

was like me"didnTt have nary a soul to care Tbout

"er anT she needed me like I needed her. No, I

ainTt Ter Granpa"ainTt no relation to Ter atall!

I jusT happened ta find Ter wanderingT lone in the

snow up in Providence Forge one night. Poor 1iT]

thing had been left to wander by two damned no

good parents, so I brought Ter back here with me

and give Ter a good home with lotsa love anT care.

Ya see, mister,T McCraven continued with his

mouth twisted with bitterness, oin this rotten

fancy world of yourn I was always shunned and

unwanted! People didnTt want a ugly creature

like me rounT! I been ugly since I was born! Ugly

with purple mess anT scars all over my face! Even

the younguns Td run off a hollerinT anT screaminT

when they seed me a cominT! Nobody wanted a

ugly thing like me, so after I made me some money

a trappinT I latched onta this here land and been

here since. Folks donTt need liT] Susie anT me anT

we donTt want no part athem! AnT ya lemme tell

ya somethinT else, mister,? he said, pointing a

stubby finger menacingly towards me, oifin ya

leave this place anT bring a buncha smart elecky

folks in here ta try ta take my Susie Tway from

me, ya cTn Tspect some killinT, cause ainTt a soul

gonna come Ttween this chilT anT me! Now ya git

offTn this land for the last time. I neva done kilt

a man yet anT I donTt wanna hafta start now!? I

left McCravenTs Cove that evening.

Pagan Kites

Night is falling

Soft, but heavy as a dark purple curtain.

The shades of night fall teasingly

While little boys and girls play tag

With a fervor transcending energy.

Back and forth running

In the close-cropped grass

That smells like Fourth of July melons

They run and chase

Their hearts beating wildly as pagan drums.

Refusing to go into the white houses

That stand with gaping doors

Like mouths of cool dark tombs

While the deep purple shroud covers them.

SPRING, 1962

£ gee SSS

Ke AAR SS aint awl Sint i eG eintiniad eeadieceal stated akesememencces PE a Sp ee eee gloria fae eer

"SARAH HANSEN

15

a a a ST SN Se eke w eho SSS zs :

ba

16

~" =| rr O "U0

Jn Cime: Ju Season

(3rd Prize"1962 Contest)

In time my thoughts shall tread these fields

And plant this fallow land,

In time will images advance by rows

Unique in style, but planned.

In season dews of many days

Shall presage harvest time;

In season, acres filled with dreams

Shall blossom into rhyme.

But not until I share a love

More precious than I know

Shall I, upon these fallow fields,

Go forth again to sow.

"WaALTER N. DIXON III

ne

a nate theres 4 .

5st ROWE ELST TE TEN STENER SPATE RI STSES TOTS ISOS *SSS28E tag

Morning

(1st Prize"1962 Contest)

I have known quiet moments

Like this before,

MorningTs sun-laced shadows

Sprawled across the floor,

Wind-ruffled curtains

Weaving patterns on the door:

Hushed, sparkling laughter

From the room below,

Young, chattering voices,

Footsteps, soft and slow.

The smell of wood-smoke

Drifts up from the lake,

And with a last long struggle

With forgetfulness

Iwake...

"BRENDA CANIPE

Lover

(2nd Prize"1962 Contest)

Earth-bound, dripping fingers gripping

At the lonely channel marker,

"Round its naked whiteness slipping

Robes that deepen ever darker.

Thin arms paling, weakly flailing

At the omnipresent ring,

Close embracing, holding, veiling,

Till the fog alone is king.

Lonely, dying light, the crying

Channel too is lost in gray.

Still, beneath a wet ghost lying

In a wanton disarray.

"QG. BURGESS CASTEEL

THE REBEL

o iene ish rcinovisie uk ad

oisacunremneteetia comtnetet

SO. ty A

TR

os = ied Seas

Serenade

Asking no wine

but only belief

remembering red days

in a young cocoon

white light

on a leaf

and the windTs lean fingers

stroking the dust of afternoon.

II

And the tongue of flame

out of the darkness comes

and faces rise beside the bed

ghosts who wade

through naked air to catch

the careless coins of words we shed;

and those few who rise

from the cobbled streets

above the scream of traffic horns

names and voices

in tattered coats

dying and the yet unborn.

SPRING, 1962

III

Only voices warm

with the smell of wind

and tight with sleep and snow;

deep eyes and the lanes of sleep

and the people of the shadow

who rise and go.

Dark people of the shuttered soul

who move with mellow music

go home in the dawn light, warm light;

the stars are womenTs eyes

and the dawn a paper doll

in a smudged white dress

wearing slippers of dew.

IV

And Christmas clear

and sharp and cold

when we renounced the cross

but the dolly had no tears

the puppet

no remorse"

only after"

the puppet-master cried

to see the house glow with light

the people warm inside.

" MILTON G. CROCKER

17

SN .

a

PMA Tego Tle RST PRIS SASSI CEST SE BESTS TS as PESTS PETE TA FSS SSS SL e hae = eRe, 2 *

" ?"? " ey ee Sg e

PSNR DONS et See SP aE ae pa z A oa

Karl (Jay) Shapiro was born in Baltimore, Md., and

matriculated at the University of Virginia and Johns Hop-

kins University. He was Consultant in Poetry at the Li-

brary of Congress and a member of the National Institute

of Arts and Letters, 1959.

Mr. Shapiro has been praised by both critics and fellow

poets for his contributions to American letters. In 1941,

when his first poems appeared in a New Directions Five

: Young American Poets, Louise Bogan predicted that ohis Son WN j a\

i work will become a sort of touchstone for his generation.? en? pe x KN yy AN-g \\

a Miss BoganTs predictions have been rewarded. Mr. Shapiro j, a SY :

has since that time received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in

1945; has been Consultant of Poetry at the Library of Con-

gress from 1946 to 1947; has been a member of the National

Institute of Arts and Letters, 1959; and has been editor of

Poetry: A Magazine of Verse.

Mr. Shapiro has said, oMy interest in poetry dates back

to my high school days ... Later, at the University of Vir-

ginia, I did poorly in my studies because of my greater

interests in writing verses.?

Mr. Shapiro is now an instructor in English at the Uni-

: versity of Nebraska and is editor of The Prairie Schooner.

| The following is a lecture which he gave at East Carolina

College in a program with Mark Van Doren and which Mr.

Shapiro kindly permitted THE REBEL to print.

SS

\S S

S

Y

Ree.

\) SSS

Shi esata

z

oe

Karl §. Shapiro

THE POET AS TEACHER

Bd

ar

ae

7. a

sane SE EGE EAA AAB LABEL EAL LE ELE LEE AES LEE S 5

13. are two kinds of teaching the poet does

today. The first is the conventional kind of higher

teaching"by conventional I donTt mean anything

bad but only that which we are used to. Poets

who teach literature have always been present in

universities in small numbers and some have been

famed as teachers. Mark Van Doren is probably

one of the most famous literature teachers in

America. I have heard of him in this capacity

ever since I can remember. This kind of teacher

of letters unquestionably gains in his teaching

from being a poet himself. His courses must be

greatly enriched by first-hand insights and expe-

rience which are denied the literature professor

whose training is purely scholarly. Essentially

however the poet who teaches literature follows

18

: ee 2B Seer i ig be gS aA et TR RE Seen a haze

tis iat =

the rules and customs of the scholarly profession,

and I assume that the poet always plays second

fiddle to the scholar and teacher in this situation.

A. EK. Housman maintained a complete divorce

between his scholarship and his creative life, so

much so that we tend to think of him as two sep-

arate people (as he himself did). The Latinist

and the lyric poet were never on good terms. I

cannot tell you much about the poet as literature

professor or scholar, for I am neither. It is true

that I teach a survey course to undergraduates

once in a while, but I do that out of a book. The

closest I come to literature teaching or scholar-

ship is in a course in contemporary poetry, which

I love to teach for more or less selfish reasons.

But I could never teach a operiod? course and

THE REBEL

Re Sa ES

{Fee EAE AAS SABLE PSM RES TSE MEE Rl eS eh SR REN eS BSS el a a ew Sandestin ate ate eee

nobody would expect me to. I have not the train-

ing for it. There is a distinction between the

bona fide literature man and a poet in the univer-

sity like myself, whose only qualification, at bot-

tom, is that he is a poet and doesnTt bite students.

The literature professor carries on the disci-

plines of the scholar and imparts them to a new

generation. The campus poet on the other hand

is a kind of captive specimen of the rare bird, and

something of a freak, make no mistake about it.

I fall into this category, which might be termed

oOur Poet.? There is almost never more than one

of these per campus, for reasons which are some-

what tribal and obscure. Even when there are a

dozen poets scattered throughout a faculty, Our

Poet occupies a unique position, namely, that he

teaches Creative Writing and acts in a manner be-

coming a poet. That is, he is less becoming than

other people. The average university or college can

maintain only one such personage. Even that one

may sometimes put a heavy strain on the academic

community.

There is practically an entire literature of and

about the campus poet (Our Poet) by now and I

am not going to add to it, if I can help it. Most of

this literature makes fun of Our Poet, not without

reason, and yet there are a few facts about him

which are generally accepted. For instance:

The campus poet is an American phenomenon.

We will not find his like in the European or Asiatic

university.

The campus poet is not quite in the academic

community and not quite out of it. Frequently he

feels guilty about being there at all.

He experiences two serious kinds of opposition:

one from the old guard scholars who find him a

needless accessory to the curriculum, if not a dis-

ruptive influence. More important perhaps is the

opposition from fellow writers on the outside of

the gothic wall, who consider him a paid hireling

of something or other, a wage slave and a con-

formist. This kind of criticism comes not only

from the Beat writers but from well-wishers of

all kinds who fear for the poetTs creativity in the

academic climate. And both kinds of opposition

can marshal good arguments for turning Our Poet

out into the world.

Depending on how profound we want to appear,

we can look upon Our Poet as an accidental ex-

erescence or bunion of the educational community ;

or we can see him as something deeply symptom-

atic in our culture. I tend toward the latter view.

Our educational system is extremely fluid and

SPRING, 1962

Shige ITS AS Se ee

See eee ee eed

experimental, compared with old world systems.

Ours is the first nation to try to experiment in

mass higher education, without regard to service.

I mean that the old systems trained a handful of

men for rulership; and that is still more or less

the case in England, France, India, and even Can-

ada. Russian higher education is purely for serv-

ice; literature for instance is taught there as a

function of political philosophy. Education for its

own sake is unknown under dictatorships. We,

on the other hand, take a more frivolous view"

or did before we got into the arms race with Rus-

sia. (We are now beginning to demand education

for service also, and that is a bad turn, in my

opinion.) Let me simplify what I am saying still

further. The Old World education was and is

essentially class education, because their societies

are built upon class structures, in Western Eu-

rope as well as in Russia. In our relatively one-

class society, which is a middle class society, we

go to college to prolong the incubation period of

life. Not to go to college in America is something

of a disgrace, just as illiteracy is, and in a certain

sense, it doesnTt matter much whether we send

our children to Harvard or to some remote rural

college which nobody ever heard of. Sociologic-

ally, the American college or university (and the

terms are significantly interchangeable with us)

is a lolling-around place preceding marriage or a

job. Whereas in Europe the university is the

final weeding-out place for national leaders of all

kinds. It is well known that the average high

school student in a European country can, on an

examination basis, put most of our students and

many professors to shame. This is because, ob-

viously, no European family would ever think of

sending a child on to higher education unless he

came from the privileged class or unless like D.

H. Lawrence, for instance, he showed a genius for

rising to that class.

In a sense, the Old World university is a train-

ing ground for princes. In America, everybody

goes to college. Practically anybody, with a reas-

onably white skin, can get into one, somewhere.

Now this sounds like I am writing a book, and

ITm not. I will skip over the implications of what

I have just said, and come to my point which |

hope will explain why we have the poet, the paint-

er, the composer, and every kind of artist on the

American campus. My point is that the Ameri-

can college campus is not simply a place of educa-

tion: it is also and maybe primarily our focus of

culture.

19

CS ee eS ee ee St ee RE EE eT Se See

Se

Shh Tae

Bs ig

a :

ease

=x" anti

OR Teves,

oiui grad iar Oe

Here is the difference. In the Old World (Eu-

rope, Asia, even South America, which is terribly

prematurely old)"in the Old World, culture lives

in the great old cities with their fabulous relics,

crushing tradition, etc. In every European na-

tion, for instance, all culture is magnetized to the

capital. And there is only one capital: London

draws to itself all the culture of England, Edin-

burgh that of Scotland, Paris the same; Italy has

several capitals, having been split up for centu-

ries; but it is always a particular city which

gathers up the treasure. Sometimes the treasure

is robbed, as Napoleon and Hitler robbed one

anotherTs museums"but always for the capital,

the Center.

And what about us? Well, we have no Center.

Washington, for all its museum-like beauty, is a

dead city culturally. No poet or painter or com-

poser of any consequence ever came out of there.

New York may be the closest thing we have to a

Center, yet no one really thinks of New York as

the one center of American culture. It isnTt. It

has many of the finest museums, most of the pub-

lishing houses, theatres, orchestras and the only

opera in the U. S., and yet New York is not the

Paris or the London of America. Nor is Boston,

certainly not Philadelphia or Baltimode or

Charleston or even San Francisco, with all its

sparkle.

The fact is that American culture is decen-

tralized, spread all over, and tends to show itself

in places, however tiny, where there are vital col-

leges or universities. In my city, for instance,

there is no art museum except one being built at

fabulous expense for the University. There is no

good music or for that matter, jazz, which does

not come from the University. We have the only

live theatre. The painters and their students

come from the University. And the writers also.

And the important point is that these activities

are not scholastic or parochial; they belong to the

community at large.

What I am trying to say is that the American

college is to us what the village opera in Italy

used to be"the cultural ground. We can com-

plain all we want about mass entertainment and

TV hypnosis, but the fact is that all the arts in this

country are spreading like wildfire, leaping from

cow college to cow college across the land, and

that we probably have more creative vitality to-

day than all the European countries put together.

I am not saying that we are turning out master-

pieces by the hundreds, but I am not saying we

20

ate Si iain AEG i A DS aOR ES eS

: a pa ga ea i ate na kd ard ob has

aren't. In any case, that is for our children to

judge.

Whereas in England, for example, which has

produced what is probably the greatest poetic

literature in history, there is no poetry to speak

of. English poetry today is practically non-exist-

ent. I canTt explain this and wouldnTt want to try,

but if you quickly compare the poetry of the first

half of the 19th century with the first half of the

20th, you will see what I mean.

Having said this much, I want to withdraw a

little. I do not mean that our cultural state is the

better for being spread in all directions: I am

simply stating what I take to be an important

fact. In the matter of poetry publication, for

instance, it no longer matters what part of the

U. 8S. a book of poems comes from. There are so

many good publishers of verse, probably half of

them university presses, that the name of the pub-

lisher or his city is irrelevant. Whereas if one

thinks of a new poet coming out abroad he would

think: Gallimard in Paris is practically the only

one of repute. Faber and Faber in England has

the monopoly of living poets there. This mono-

lithic business has long since gone by the board in

America.

Now let us come back to Our Poet. There he is

on the small-town campus, slightly declassed

within and without the walls, scuffling ofor

scraps of notice,? it may be, like any other artist,

within and without the walls, and mysteriously

teaching something mysteriously called Creative

Writing. Is he happy? What is he up to? And

what can he possibly teach?

This of course depends on who the poet is.

Statistics will be of no avail here. If an English

Department is in need of a Romantic scholar, a