[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

STAFF

EDITOR__. Roy Martin

BUSINESS MANAGER David Smith

ASSISTANTS TO EDITOR J. Alfred Willis

Junius D. Grimes III

BOOK REVIEW EDITOR _Pat Farmer

ASST. BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Denyse Draper

EXCHANGE EDITOR Carolista Fletcher

ASST. EXCHANGE EDITOR Sue Ellen Hunsucker

ART STAPF. Al Dunkle

Bob Schmitz

Mike Miller

Larry Blizard

ADVERTISING MANAGER B. Tolson Willis, Jr.

EY PIST: Sallie Carden

FACULTY ADVISOR Ovid Williams Pierce

NATIONAL ADVERTISING

REPRESENTATIVES __-- College Magazines Inc.

405 Lexington Ave.

New York 17, New York

Member Associated Collegiate Press

EDITORIAL

REBEL YELL ...

FEATURE

Interview With Jonathan Daniels_

FICTION

Son of Silver by S. Pat Reynolds. Soe eae a

Where Is Harry Stewart? by R. Elfreth ce. aS

ESSAYS

The Character of Jazz by Jan Wurst = ee

William Faulkner and the South by Junius D. Grisiee! I 24

Sir John Suckling by Sherry Maske iets ite eae

POETRY

The School Marm by Kay McLawhon : ween |

The Sound by Jim Stingley, Jr. ~ . aoe Rae eee

Chance by Sarah Hansen See oe aD 16

Sonnet I by Sarah Hansen : Be a ee

Sea Lonely by Sarah Hansen ces Bei

Distance by Sanford Peele : ay Rie tec

Seer by Sanford Peele... ee aa = San

Green Rhythm by Sanford Peele uae ae a oes

The Journey by Carl Yorks. Ce 2 ee ; 88

mews Dy. Sue men Munsueken fee eG

Spring by Denyse Draper. co) Bs ee

ART

Jazz Series by Larry Blizard_. pee

Ceramics by Bob Schmitz and Bob Butler __.20-23

REBEL REVIEW - ee 87-41

Reviews by Tom Seating Daxtell Surat. an. Ellen Sanna.

Pat Harvey, B. Tolson Willis, Jr., Denyse Draper,

John Quinn, and Staff.

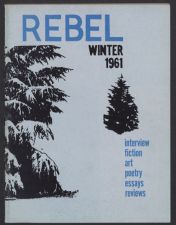

COVER by Mike Miller and Bob Harper.

THE REBEL is published by the Student Government As-

sociation of East Carolina College. Created by the Publica-

tions Board of East Carolina College as a literary magazine

to be edited by students and designed for the publication of

student material.

NOTICE"Contributions to THE REBEL should be diréct-

ed to P. O. Box 1420, E. C. C. Editorial and business offices

are located at 30914 Austin Building. Manuscripts and art

work submitted by mail should be accompanied by a self-

addressed envelope and return postage. The publishers

assume no responsibility for the return of manuscripts or

art work.

f,

A

hes

Ne

=

T RN

THE REBEL

"dAssociated Press

Interviewer: Define the role you think East

Carolina College should play in the state educa-

tional system.

Mr. Daniels: It seems to me perfectly clear

that the very growth of East Carolina is the best

evidence that it has and must play a large place

in the educational system of North Carolina with

its location in eastern North Carolina. There is

a demand for that school and it has grown and

shown vitality. One of the things that worries

me sometimes is that East Carolina has not yet

decided exactly what it wants to be. Some years

ago you decided, with wisdom I thought, to take

the word oteachers� out of the name of East Caro-

lina Teachers College. That meant that you were

not merely going to be a normal school, but the

college meant to be a school in which the liberal

arts and a liberal education could be secured by

the wide circle"a wide area"in eastern North

Carolina and beyond. Now the question which

arises is where do we go from here? Obviously

East Carolina cannot grow and be what it should

be if it is merely dominated by the school of edu-

cation or by people who are merely interested in

producing teachers. Frankly, I think more col-

leges are stunted by over-emphasis on courses in

WINTER, 1961

Interview With

JONATHAN DANIELS

teaching methodology than by any other thing. I

think all scholars today realize that the least vital

schools in all our colleges and universities are the

schools of education. We have too much about

the business of teaching people how to teach,

rather than teaching them something to teach.

But I donTt think that East Carolina should en-

deavor to go forward to be a university. What I

think we need in North Carolina, and I think

East Carolina must play a very important part

in this, are liberal arts colleges. By liberal arts

colleges, I mean colleges in which, perhaps, the

B. S. as well as the B. A. Degree should be given.

And beyond them, a few (two at least, State

College and the University) places where gradu-

ate work and graduate degrees are given. I think

that East Carolina has shown a vitality that has

lifted it high above the normal school, and I

think it would dissipate its energies if it tried to

go on and be a university.

Interviewer: What significant developments

do you see in the South since you wrote A South-

ener Discovers the South?

Mr. Daniels: ThereTs a lot more paint. I see

some dissipation of degrading poverty. But I see

3

a lot of people leaving the South. They are par-

ticularly leaving the area around East Carolina

College. That comes, of course, from the mechan-

ization of our farms; it comes from the lack of

jobs in the towns. I see much that is encouraging.

We are cleaner, richer, better fed; but I think

sometimes we are apt to mistake the apparent

advance at home from an advance which is com-

parable with the advances in the rest of the coun-

try. That is to say, we go forward, but the areas

with which we compare ourselves go forward too.

I have a hope sometimes that we are getting away

from the stereotype of a south that was always

lamenting its poverty and, at the same time, al-

ways singing of its magnolias. I think weTve got

to realize that if we advance at all, it must be

in terms of a world advance, certainly a national

advance. I think we have made great progress

in the twenty years since I wrote A Southerner

Discovers The South. But sometimes I think we

kid ourselves, because if we look at the statistics

the relative relationships donTt change as much

as the picture we see out of the window.

Interviewer: Do you regard North Carolina

as one of the forward-looking states of the South?

Mr. Daniels: Well, of course I do. ItTs a strange

thing about this state. Somebody once said that

it was a state that had less to forget than the

great plantation states. And so we werenTt caught

so much in the ante-bellum stereotypes and pic-

tures. We were a state of small farms. Yet the

whole history of North Carolina before the Civil

War was a story of stagnation. They called us

the oOld Rip� among the states. Some people

said that we stayed asleep while other states stir-

red. There was just beginning to be an awakening

in North Carolina when the Civil War came and

thwarted it. Then there were long years of

poverty, stagnation, a sort of a stubborn liking

for old ways"no taxes, poor schools that lasted

all the way up to the Aycock administration.

There was an awakening then. I hope that there

is an awakening now. But, you come from East

Carolina College. I went to the University. I

have had my doubts in recent years as to whether

or not the University quite deserves, as not so

long ago it did, to be called the oCapital of the

Southern Mind.� I donTt find the books coming

out of the University of North Carolina Press. I

donTt see personalities like Odom, Greenlaw, and

Graham. I find a certain routinism in the Uni-

versity. ITm not sure thatTs not true of all colleges

4

and this college generation. We made Communism

so repulsive, and McCarthyism intimidated us so

much that there doesnTt seem to be any radicalism

for young people to turn to, any freshness of

thought. So sometimes (I hope not at East Caro-

lina) in some places where the young congregate,

what used to be creative radicalism has turned

into a sort of beatnik stagnation. So I think North

Carolina is a forward-looking state. Once again,

we used to say that we were a vale of humility

between two mountains of conceit. Sometimes it

seems to me that in recent years we have been

a little more boastful about our intellectual prog-

ress than was justified. We are a forward-looking

state, but there is a long way forward for us to

look.

Interviewer: Do you feel that the resources

of the eastern part of the state have remained

untapped ?

Mr. Daniels: I donTt feel that they have re-

mained untapped. I think that we are too apt to

think of Eastern Carolina as a sort of separate

area different from other sections. If you go into

the old agricultural regions of any state in the

South, where mechanization is in progress, crop

controls are in force, the change is different. We

like to live easily in Eastern North Carolina. We

like fishing; the June German brings young peo-

ple hundreds of miles to dance; the Piedmont

grows rich, and sometimes we stay happy with-

out enough. There is a spirit there"of complac-

ency, I think"and one of the most destructive

forces is the fact that too many of the small towns

have been too bitterly competitive. I know there

was one industry that was about to come to East-

ern North Carolina. They went to Rocky Mount,

and were told all the disadvantages of Wilson.

They went to Wilson and were told all the dis-

advantages of Rocky Mount; so they decided to

go to some other state. The resources of Eastern

North Carolina, like the resources of every sec-

tion, are the people. There are no finer people

on earth than the people of Eastern North Caro-

lina. But sometimes, they have been too content.

There hasnTt been enough effervescence. We like

the old ways, as all agrarian civilizations do. Now

we are caught in the pinch. We canTt support the

people on the land. We havenTt got the jobs in

the towns. And I think Eastern North Carolina

has got to develop its resources. You remember

the story in Uncle Remus, when Old Uncle Remus

was telling the little boy about the fox chasing

THE REBEL

the rabbit, and the rabbit climbed a tree. The

little boy said, oUh, oh, Uncle Remus. Rabbits

donTt climb trees!T and he said this rabbit was

*bliged to climb. I think Eastern North Carolina is

*bliged to climb and I have the hope that a part of

the vitality that weTve got to have in that area is

going to come from such an institution as East

Carolina.

Interviewer: Do you see any signs that it will

shortly make its contributions to the state?

Mr. Daniels: Well, itTs always made contri-

butions to the state. It is true that at this moment

we donTt seem to be getting as much intellectual

vitality, political vitality, from the East as from

the Piedmont, and the Piedmont present from

Raleigh to Charlotte. But you must remember

that our heroes"they come, all of them"I sup-

pose McKeever is right on the border, old man

J. Y. Joyner"you go down a list"Jarvis, who I

believe established East Carolina"have got to

come again. Things move in cycles. I donTt think

that the fact that our greatest men in the past are

not equaled by North Carolinians now is the sign

of any sort of decadence or slipping back in our

people. Things move in cycles and I believe there

will come from Eastern Carolina in its turn, and

in its necessity, contributions to North Carolina

which will both serve that section and serve the

state. And in that relationship I would like to

say this: we are not going to serve North Carolina

by insisting that Eastern North Carolina continue

to have a larger representation in our legislature

than in proportion to its population. WeTve got to

be willing for the state to grow as it grows, and

if we try to put any curbs on the democracy of

other people weTll put them on ourselves as well.

Interviewer: Do you feel that by its restraint

North Carolina has set up a pattern for integra-

tion.

Mr. Daniels: Well, I think that North Caro-

lina has had great good sense and great good

luck. We adopted, as you remember, the Pearsall

Plan overwhelmingly. I was against it, but it

was adopted. Yet since it was adopted nobody

has mentioned it; we havenTt used it. When some

Indians tried to use it, why we pushed them away.

The Pearsall Plan today is a complete dodo. There

is nothing you can do with it. School assignment

law, however, is a sound law if it is approached

WINTER, 1961

with good will. Now, all of us recognize the diffi-

culties and the dangers involved in this situation.

But obviously, the law is there. WeTre not forever

going to be able to, well, shall we say, avoid it.

ThereTs going to be more integration. I think

that it can be accomplished if our people"our

best people"dominate, without too much damage

to our customs and our happiness. But I think,

and this leads me to the next question, that we

all have to realize the fact that we are not different

from people elsewhere. We could have an explos-

ion and we could possibly let the least intelligent

whites and the most vociferous colored people lead

us in the difficulty. But I hope and pray, and I

believe, that this state will avoid any situation

comparable to Little Rock or New Orleans. But

your generation has got to take the lead in the

intelligent solution of a problem which, by no

means, is one in Eastern North Carolina. It is not

a problem in North Carolina alone"or the South.

We have to realize increasingly that we white

people are the minority in the world, and that

what we do in Pitt County is soon known and

discussed and has its effect in Pakistan. We donTt

live in Eastern North Carolina. Unfortunately, in

our age, with the communications and the collis-

ions, all of us have to realize that we live in the

world.

Interviewer: Do you feel that KennedyTs elec-

tion was indicative of lessening religious discrimi-

nation?

Mr. Daniels: I think that thatTs a very com-

plex question. I hope so. I do not, however, be-

lieve that the people of North Carolina have

changed their notions about the separation of

church and state. I think thereTs belief that Mr.

Kennedy was candid and honest when he expressed

his faith in separation of church and state. You

boys are too young, however, to make a real

comparison between the campaign of 1928 and

the campaign of 1960, in each of which a Catholic

was a candidate for presidency. In 1928 we not

merely had Catholicism, we had a Catholic, who

in his personality represented the differences be-

tween a certain type of city man that seems

strange to us. WeTve been taught for years that

Tammany Hall to which he belonged was a danger

to the country and the Democratic Party. And

itTs difficult for people today to believe how great

was the emotionalism that surrounded the issue

of prohibition. The churches in 1928 were not

merely concerned about the fact that Mr. Smith

was a Catholic. The Methodists and other protes-

tant churches were also much concerned about

the fact that he was a Catholic who wished to

abolish the Prohibition Amendment. So that

campaign was very much more complex in terms

of its emotions, its prejudices, country against

city, Protestants against Catholics, than the one

just passed. John Kennedy, after knowing another

Harvard man named Roosevelt, didnTt seem a

stranger to us as Al Smith and his brown derby

did in 1928.

Interviewer: Would you care to comment about

the alleged machine-controlled politics in the state?

Mr. Daniels: I donTt think there is any such

thing as a machine in North Carolina. Undoubted-

ly there are little county cliques; there.are class

groups; there are conservatives versus liberals.

But I donTt believe that any man within the last

decade has made any progress at creating any-

thing that would compare, for instance, with the

Simmons Machine which existed thirty years ago.

Undoubtedly courthouse rings, conservative and

liberal organizations, try to exert pressure and

often do. But I donTt see how anybody could think

that there was a machine control when in the last

primary we had four candidates for Governor, no

one of whom could exert crushing power or cer-

tainty of election. We are a good oscrapping�

people in North Carolina, and weTre not going to

let any single machine or power dominate us.

What weTve got to have is vitality in the people,

thoughtfulness; and the one thing we donTt need

in Eastern North Carolina, or anywhere else in

this state, is docility. And the one thing that I

think that we need most in boys like you at East

Carolina and other colleges, and in the young men

growing up around them, is the determination that

docility is not going to be the mark of your gener-

ation. LetTs get going. DonTt be afraid of ideas.

And to go back to the beginning, the one thing

that can be most important at East Carolina is

that it be a center of ideas, and welcome for ideas,

in the region it serves. I like to see North Caro-

lina when itTs stirred up. When itTs sitting on

its seat and just looking over the end of the fishing

pole, weTre in a bad way. When people are de-

bating and discussing and disagreeing, North Car-

olina is in a healthy state. I wish East Carolina,

I wish Eastern North Carolina plenty of contro-

versy. Keep them stirred up, because when peo-

ple are stirred up theyTre alive ; when they sit down

and stop talking and stop doing, theyTre dead.

THE REBEL

A Word Said... -

Under the direction of President Leo Jenkins

and a committee of local people, plans are being

discussed which are directed towards making this

college the cultural center of Eastern North Caro-

lina. This is a natural action. With its position of

influence in this section of the state, East Caro-

lina should be recognized as a focal point of cul-

tural activity.

However, the principal obstacle to this move

will be the school itself. Is East Carolina ready to

accept such a distinction as this? Are we ready

to take in hand the responsibility it embraces?

At the present time, these questions draw a

negative answer. We are not prepared. Once

again the attitude of a great percentage of stu-

dents and faculty here can be described as apa-

thetic. Steps must be taken to alleviate this situa-

tion, else the plans underway will be useless.

Perhaps the first step to remedy this situation

is through a process of conditioning. By this we

mean, conditioning which will lead to the emer-

gence of an atmosphere which will accept the re-

sponsibilities involved with being the cultural

center of this section.

How can this atmosphere be evolved? It is the

feeling of several connected with this move that

the first step would be to begin a movement here

on this campus which would bring about an

awareness of the past"the heritage of Eastern

North Carolina. We share this feeling.

Eastern North Carolina has a great heritage.

The beginnings were with the Roanoke Island

settlement, 1584-1587. Then in 16638, Charles II

granted to the eight Lords Proprietors the Caro-

lina Charter. It is to these men, Edward Hyde,

Earl of Clarendon; George Monck, Duke of Albe-

marle; William Lord Craven; John Lord Berkely ;

Anthony Ashley Cooper, Ear] of Shaftesbury; Sir

George Carteret; Sir William Berkely; and Sir

John Colleton that we owe our beginnings.

In addition to these individuals, North Carolina,

and specifically the Eastern section, has produced

WINTER, 1961

many notable figures. For example, James Iredell,

Nathaniel Macon, Willie Jones, and in our own

century Charles B. Aycock, the great oeducation

governor,� came from Eastern Carolina environ-

ments.

There are other aspects of our heritage from

which we could draw. Perhaps with some of these

elements forming the basis, a program could be

inaugurated here, recognizing our past, and sub-

sequently an atmosphere capable of accepting the

responsibility of being this sectionTs cultural

center could be created.

To clarify the preceding statement, this pro-

gram could possibly take in the establishment of

a Hall of History which could house documents

and relics of our past. Also, perhaps statues and

other memorials could be erected honoring the

individuals who have been prominent in our his-

tory.

But this entire movement is not solely our re-

sponsibility. Although the college will be expected

to play the dominant role, it is also the respon-

sibility of the people of Eastern North Carolina.

This area could take the initiative set forth by

the leaders of this plan by aiding in the establish-

ment of these symbols of the past. For example,

the counties which are named for people such as

Iredell, Jones, and the Lords Proprietors could

honor their namesakes by means of some type of

memorial to be placed here at the college. Event-

ually, we believe, this action would result in an

enlarged sense of history and a deepened per-

spective of our past and heritage.

The significance of this entire movement is

enormous. It is one of the most important awak-

enings which could take place in the life of this

college. Too, it is a rightful move, for East Caro-

lina College deserves to be the center of Eastern

North Carolina, not only culturally, but also in-

tellectually. The potentialities which lie in this

college are innumerable.

"MARTIN

The Rebel Yelk

In addition to the regular work involved with

the publication of the Winter Issue of The Rebel,

one of the principal projects during the winter

quarter has been the writing contest.

This yearTs contest, to date, can be considered

as very successful. This is evident in view of the

number of manuscripts which have been submit-

ted since the first notice of the contest was circu-

lated.

The current contest was scheduled on February

25th, the final day of the Winter quarter. How-

ever, one development has caused the editors to

extend the deadline date until April 1, 1961. The

change is due to the donation by Sigma Sigma

Sigma Sorority of $25 to be used for awards. This

brings the total prizes offered to $30.

This action by Sigma Sigma Sigma is a signifi-

cant mark for both The Rebel and the sorority.

For the magazine it is a sign of support offered

by the student body members, and for the sorority

is displays a mature sense of values which are

vital to the growth of this college. To the women

of Sigma Sigma Sigma, the editors extend their

gratitude for the support they have shown for

the magazine and for its purposes.

In this issue many strides forward have been

made. It has been the objective of the staff to

present to the student body a magazine which re-

flects growth from issue to issue. This growth to

which we refer embraces the size of the magazine

(number of pages), and the number of fiction,

non-fiction, and feature articles contained. Growth

also refers to the quality of the material used.

In all of these instances, we believe that the maga-

zine has progressed with this issue.

In this issue there have been many changes

made in design. This is due primarily to the

efforts of the new art staff composed of Mike

Miller, Larry Blizard, Al Dunkle, and Bob

Schmitz. These four from the art department

have assembled the art work for this issue and

have played prominent roles in the task of design-

ing. The editors extend their commendation for

a job well done.

Also in the realm of art, the staff owes thanks

to Bob Harper who furnished the cover photo-

graph. The surrounding design for the cover was

done by Mike Miller.

The feature article for this issue is an inter-

view with Jonathan Daniels. Mr. Daniels, North

Carolina author, is prominent in many facets of

the life of the state, and is perhaps best known as

editor of the Raleigh News and Observer.

Other works appearing in this issue include

essays written by June Grimes from Washington,

N. C., and Sherry Maske, from Rockingham. The

other non-fiction contribution is an essay on Jazz

by Jan Wurst.

In the field of fiction, S. Pat Reynolds, a grad-

uate assistant in the English Department, and

Elfreth Alexander, graduate student and last

yearTs contest winner, present oSon of Silver�

and oWhere is Harry Stewart?� as short story

contributions.

The poetry section for this issue contains selec-

tions by Sarah Hansen, Sanford Peele, Carl Yorks,

Jim Stingley, Jr., Sue Ellen Hunsucker, and Kay

McLawhon.

Book reviews for this issue wehe done by Tom

Jackson, Darrell Hurst, Sue Ellen Hunsucker, B.

Tolson Willis, Jr., Pat Farmer, Denyse Draper,

John Quinn, and Pat Harvey.

Harry Golden, busily completing his new book,

Carl Sandburg, and also preparing for his trip to

Israel to cover the Eichmann trial for Life, was

unable to complete the second installment of the

Fall IssueTs interview. Thus, it will not appear.

THE REBEL

SON OF SILVER

By S. PAT REYNOLDS

The street urchinsT moved-back and forth to

and from the grocery store on the corner, going

with empty Pepsi bottles and nickels clinking

against the glass and*coming back. drinking. ~They

walked or rode bicyclés. oThey walked with their

heads up,: looking around; or with, their heads

down searching the dusty sidewalks for treasure.

Or they rode their bicycles with great curves, in

and around the parked/ cars, sometimes running

up on the sidewalks ~where. they left corduroy

prints in-the dust. And they yelled at ¢ach other,

stopping to examineT themselves-together. or.they

waved to their images on the other side of the

street.

oHey you, Mickey, I got a knife. My daddy

give me a knife.� The red-headed oné sat on his

front steps, and Mickey crossed thé street over

to him. Mickey didnTt believe the other boy, and

he held his Pepsi-high, swilling-it-in and smacking

his lips loudly in his doubt.

The red head,..to.convince Mi¢key, said, oDid

you know my daddy give me a pocket knife?�

oNaw. WhereTs that knife?� Mickey asked,

holding his Pepsi by the bottleneck.

oTn the house on the mantel piece. We could play

mumbly-peg.�T Red head looked at MickeyTs Pepsi.

It was nearly half gone and the brown foam

floated sweetly on top.

oYou ainTt got no knife.� Mickey caught him

in the wide brown eye and then raised the bottle

to his lips again.

oT have, too. My daddy give it to me. He found

it on the street. Me and SammyTs going to play.

mumbly-peg.�

oCan I play?� Still a little doubtful, Mickey

WINTER, 1961

was almost-finished with his Pepsi.

oNaw.�

oGet the knife and let me play. oYou want

the rest.of this Pepsi?�

Frances liked to watch thems She often sat

on her front porch and watched them. They had

something that.she didnTt. have, and she couldnTt

quite call it by name. They had the street diplom-

acy of giving. and taking away with one fine

sweep. They seemed freer than herself and not

free but-bound-by laws she did not know.

In-her own days her running had-been stopped

at.the-six foot fence that walled the backyard

which Papa had put up oto keep her in and the

trash out� is*what he said. She had felt little of

what. was going on outside that fence; but-that

little she felt shyly and intensely, peeping through

the slits in the fence and feeling the ridges of

the wood in her fingertips.

Still, there had \been a few things that the

fence didnTt keep out, things.that came back

swiftly to her as she watched Mickey and Red-

head in their barteroacross the street. These

things were those that she had-done-holding onto

MamaTs hand. But they were good, not adventur-

ous good but there they were, waiting to wink

at you-when you remembered them.

She-had-entered a new place, although she had

entered it every-Saturday morning; but it was

fresh each time, and as she-walked with Mama

through the aisles of the city market,-stepping

over the puddles-of water that stood on the cement

floors, she could see the colored lady with her head

tied-up in a blue scarf, shelling beans and throwing

the hulls on-a-piece of newspaper at her feet. She

9

went there with Mama and held onto MamaTs

dress because once she had not held on, and some-

how had moved away to look at the zinnias in

tin cans and then had come back and taken

hold of a dress and looked up, but when the lady

looked down, it wasnTt even Mama. Oh, she had

been scared then, and there had been something

in her throat she could not swallow, but she had

held onto the ladyTs dress, looking up with the

lady looking down, until Mama called her from

across the aisle where she had been buying coun-

try butter. Then she had run to Mama, embar-

rassed because she could feel the lady still look-

ing at her.

The smells and sounds in the city market were

tingling and serious. She had never smelled them

or heard them anywhere else. They were new

and wonderful and always different, taking her

unaware because it seemed that she never ex-

pected them, even when she walked through the

arched door and saw the colored lady who always

sat in the entrance of the old stucco building. She

knew her by face just as she could recognize the

city market when she passed it"but they never

spoke to her nor did she speak to them. She

just passed them every Saturday morning.

Live, caged chickens squawked and complained

about their cages, and once she touched one

through the wicker cages and it pecked her finger.

She pulled her hand out quickly before Mama

could see her, before Mama could shake her head,

the silent signal that she was doing wrong. Dom-

inick, White Leghorn, Rhode Island Red, they all

watched her with beady eyes, blinking every now

and then, while Mama picked and made choices,

and she felt sorrow for them secretly and worried

about them and wondered how they felt about be-

ing eaten. And she felt ashamed that she would

eat the one Mama was buying.

Smoked meat curtained the stalls, and a man,

a country man who had blood on his apron, looked

over the counter at her and teased her with ice

chips in his long, hairy hand. But she would back

behind Mama so he couldnTt reach her. He drip-

ped liver, thumped great chunks of red meat; he

cut off pork chops for Mama, just right so she

would buy them, and he must have been very

strong because he could hold a big ham up high;

he could: hold it with one hand and point with

the other. And Mama chose, carefully, and she

took her time, and then she crammed the brown

bags down into her shopping bag and went on

over to the vegetables.

Frances remembered that the city market was

wide and somehow ripe with the people who sold

10

there and with the people who bought there. They

intermingled, yet remained distinct and separate

and would go their own ways. Calm and dignity

in overalls and print dresses waited before her,

behind the stalls, and she stood before them look-

ing. They did not hawk their goods and were

ready to show them when the buyers came, and

they would not press the buyers to select. A

country girl with an apron around her waist, with

pigtails and barefoot, would return FrancesT stare,

and Frances secretly wanted to be the country

girl; then Mama sedately exchanged her money

for fresh grown peas, and the factions would part,

but the country girl would remain for almost the

whole week with Frances. Saturday morning be-

came afternoon, and on their way from up town

she and Mama would pass the city market again,

but then it would be silent and empty and a bean

would be left lying, a few dried vegetables, a

sucked-out grape hull. And the wall of a fence

could not keep this out, and she could take it

with her and the back steps would become her

market and she could see the buyers who came

for her chinaberry beans.

But once she found a way outside the six foot

fence that kept the trash out. But then she had

not realized that the little boy who lived in back

of her was trash, that his daddy was a drunk

who painted houses when he was sober, that his

mother had big fights with his daddy. And when

his motherTs eye had been sore, looking like

FrancesT knee when she had fallen down the steps,

she was sure that his motherTs eye hurt and want-

ed to ask her about it until she heard Mama telling

Papa that the Blands had been fighting again and

that old Jim Bland had hit his wife in the eye.

When Mama told Papa that, Frances couldnTt

hear anything that made her believe that Mama

was sorry about Mrs. BlandTs eye and maybe it

was wrong for Frances to be sorry and maybe she

shouldnTt want to play with Jimmy Bland. But it

would be good to play with Jimmy if Papa ever

left the gate unlocked. Jimmy had a wonderful

horse fixed up on his banister and a string tied

on it and a pillow to sit on it and her picture

book horses werenTt like that and not as good

because you couldnTt ride them, only play like

you rode them, and that wasnTt good when Jimmy

whose daddy hit his motherTs eye had a real horse

or almost a real horse and Mama why canTt I

play with Jimmy and ride his horse? Because you

canTt and that ends it and you know your Mama

wonTt change her mind because she never did no

matter how long you sat and pouted and how

much paper you chewed up pretending you were

THE REBEL

a goat. Anyway, you were too ashamed to cry

because Papa always pointed at you and said,

look what a fix her face is in. And you looked

in the mirror one day and there it was red and

splotched up and screwed up like on Halloween

when you wore a mask and jumped at Papa from

behind the door. But you still wanted to play

with Jimmy and ride his horse and you knew you

would if you ever got the chance and maybe Papa

was at work and Mama sitting on the front porch

crocheting. And then the day came that you

stood on the apple crate and tip-toed until you

reached the latch and the gate swung wide open,

and there you stood on the apple crate, scared but

a good feeling scared, because there was the alley

right there and just a few steps away Jimmy

sat on his horse and rode all the way to Texas

and back. Jimmy watched you but did not say

anything. And you walked up his steps without

even looking at Jimmy but you knew he had stop-

ped riding and was back from Texas and was

looking at you straight and waiting. Then you

walked up to the horse. CouldnTt you almost

feel him shaking beneath Jimmy? You moved

your hand down slowly feeling the horseTs neck

and it was soft and warm to you. Jimmy got down

off his horse and all he said was oHe wonTt hurt

you. HeTs real tame. HeTs the son of Silver.� The

Son of Silver. You wondered if you would ride

the Son of Silver. The name just came right out

of your mouth as if you had been saying it for-

ever, the Son of Silver. The riding was wonder-

ful, and the Son of Silver was tame but he carried

you far away and did not bump you. And you

knew you were moving because you closed your

eyes and the alley was gone and the ground

under you moved and the trees around you whiz-

zed by like riding on a Sunday afternoon with

Papa driving. But then the Son of Silver brought

you back. He must have brought you back be-

cause something jerked and there was Mama

pulling you off the horse and taking you back

into the yard and closing the gate and switching

your legs until they burned like fire. And maybe

you cried but not loud because Jimmy was watch-

ing you, and not because the stinging hurt, al-

though it did hurt you because the Son of Silver

brought you back. And then you hated the Son

of Silver and you hated Jimmy and before Mama

dragged you in the house you screamed at Jimmy

who still watched, standing beside the Son of

Silver. You yelled at Jimmy, oYour daddy hit

your mama in the eye and I hate you and I hate

the Son of Silver.�T Next day the latch was on

the outside of the gate and only Mama and Papa

could open it.

Che School Marm

The school marm kneads my bisquit dough brain

Confines me to a pan of conventional shape

Pops me into preheated oven to bake

Where sweating shriveling i burn on the rack

Lump-crusting flanking charcoaling to black.

Freedom regained i emerge from the dungeon

Unleavened unyeasted cooked through and

through.

Devoid of all thought complacently tame

Safely i rest in the marmTs hall of fame.

Unfit for manTs bread the world is my claim

And i like the school marm win the worldTs praise

With navy blue gabardine slick-seated cliches.

WINTER, 1961

"Kay MCLAWHON -

1a

MAniz |

J

~i "a! )

DF " i nag y) EN |

He ag ANN ae

034

>

RENE NRT) RU

Re oh N NES tH

SARE Age

NB NY

l,

Ri oy

( Vly ir WW yr """""

pia Yi)! WY 4 (7

eo 4] Adder Oe

ee a Vrs (ny i

J \\ HH % (4 > ¢ Vie ! 4

my Aah 7

NM aN Lisi Ne Oh

Wh, iM

*

i! 3

it

1

67] > yn M :

4

>, 2 ae

, e

ae

4 »° LUiifs t\ j

THE REBEL

Jazz, they say, came up out of the cotton fields, out of the

sweat-drenched soul of man himself"man the individual, who

said about life what he himself had to say. It made its way to

Chicago, New York and other places and ended up finally in

smoke-filled bars on shabby, half-lighted back streets. It exists

there today, for all to see, as but one more symbol of a decaying

institution: the individuality of man.

"tLarry Blizard

WINTER, 1961

13

Music

THE CHARACTER OF JAZZ

By JAN WURST

Jazz is AmericaTs one true art form. From its

humble beginning among the Negro slaves in the

South, jazz has risen to its present place as

AmericaTs one original contribution to music, and

has taken its rightful place as a great part of our

American culture.

Many people, however, still do not accept jazz

simply because they do not understand it. If one

knew a little about the characteristics and origin

of jazz, he might understand it, and thus be able

to enjoy it. Woody Woodward, in his book Jazz

Americana, gives this excellent definition of jazz:

oJAZZ (jas) n. a native American music, a popu-

lar art form, begun by the negro, originally in-

fluenced by African and Caribbean rhythms and

popular musics available to the negro around the

turn of the century. A product of the instantan-

eous rather than the premeditated, characterized

from the beginning to the present by three basic

elements: improvisation, a unique time concep-

tion, and a range of sounds distinguished by their

individuality.�

The very earliest jazz musicians were mostly

Negroes who could not read music. It was neces-

sary, therefore, for them to improvise as they

played. Improvisation, then, is the ability to

make up tunes or to add variations on a given

melody without previous arrangement. Usually

a chordal sequence is made up in advance to give

the music some form, but this is merely a guide

for the soloing artist and does not limit his free-

dom to express himself completely. Occasionally,

two or more musicians may improvise at the same

time, producing counterpoint, in which the second

and third melody lines complement the first.

14

Improvisation is probably the most important

characteristic of jazz because it makes every per-

formance unique. No matter how many times

the same group of musicians perform the same

song, each rendition will be entirely different from

the other.

The time concept in jazz is more unusual than

in that of other music. There is always a constant,

driving four beat rhythm, which is usually played

by the string bass and drums. Normally, accents

would fall on the first and third beats of every

measure, while the second and fourth would be

relatively weak. In jazz, however, the musicians

play unexpected accents with great freedom on

any beat in an irregular manner. The piano and

guitar further syncopate the rhythm by adding

chordal effects on the off beats. The soloist then

adds his rhythm and may either play slightly be-

fore the beat, on the beat, or slightly behind it.

All of these rhythms together produce a rhythm-

ical counterpoint which is a direct result of the

Afro-American influence.

The sounds of jazz are another very unusual

feature. Almost any sound that a musician can

make on his instrument is acceptable in jazz. It

may be a dark, strident sound, or it may be a light

pure tone with no vibrato. Each sound reflects

something of the personality of the individual

performer.

Jazz was born in New Orleans nearly one hun-

dred years ago. The Negro slaves took the cur-

rent popular hymns and added to them the

rhythms of their African tribal chants. These

became the Negro spirituals that we know and

love today.

THE REBEL

W. C. Handy, a famous Negro composer, is

largely responsible for the popularity of the

oblues,� which is based on the work songs and

osinful� songs as they were called.

The blues are characterized by the flatted third

and seventh degrees of the diatonic scale, which

give it the mournful sound. The blues reflected

the melancholy of the Negro and his lamentable

fate.

Early in the 1930Ts some fine artists, Benny

Goodman and Count Basie, for example, started

a new movement called oSwing�. This style

has a comparatively strict form but still

has plenty of free rhythm. This was the era of

the big band in which the full band played rhyth-

mic and melodic patterns simultaneously or al-

ternated between the brass and saxophone sec-

tions with an occasional inprovised solo. It was

at this time that the guitar really came into its

own and replaced the banjo. oSweet swing� was

similar to ohot swing� except that it was mainly

for dancing. It was a compromise between real

jazz and the kind of music that was acceptable by

osociety�. Among the many bands who played this

sweet swing were the Glenn Miller and Tommy

Dorsey bands.

In the early T40Ts came a new bouncy type of

jazz called oBoogie Woogie,� which has a distinc-

tive, choppy dotted eighth and sixteenth note

rhythm in the left hand bass line of the piano.

With the coming of World War II, the big bands

were forced to disband for various reasons, and

the small combo of three to five men became pop-

ular.

After the war was over, the teenagers needed

something with a real beat so that they could

dance to it. oBebop� was born. It had a good,

steady beat just right for dancing. Bebop was

one of the first forms in which the drums broke

away from the strict rhythmic patterns and start-

ed on its own syncopated phrases while only the

bass and guitar continued with the basic four

beat pattern. Charles Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

were the two men who did the most toward estab-

lishing bebop.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast another move-

ment started which became known as the ocool�

or progressive jazz. This type of jazz, while still

using the basic beat, is more subdued and relax-

ing, and appeals more to the intellect rather than

the feet. The musicians were striving for a dif-

ferent sound and the use of many new instru-

ments heretofore unheard of in jazz became popu-

lar"among them the flute, oboe, baritone sax and

mellophone.

What the future holds for jazz only time will

tell. But surely it will increase in quantity and

quality, in styles and concepts as it continues to

be explored. As Woody Woodward says, oFor the

first time in the history of jazz, it is being accepted

for what it is"a medium of emotional and intel-

lectual communication; AmericaTs native art form.

Jazz is being listened to, finally"unfettered by

fads and dance crazes. This is the Jazz Age!�

Che Sound

The sun rises

over the sound

revealing marshwater and boats

moving to the sea.

Rays cover

wiregrass and earth

full of holes

sand-fiddlers and fleas

blends rainbows

in the salt-spray

WINTER, 1961

turns grass

brownish green.

Skeletons of

men, boats, crabs

bleach

deathly white.

Water and boats

return

the sun goes down

it is night.

"JIM STINGLEY, JR.

15

Poetry

by

Chance

The cat, known as a sly and secretive animal

Has a rival here. A minute spider,

Tiny, but fat with intensely bent legs.

Secretively he darts and dances

From twig to twig

intently spinning his intricate web.

Such a forlorn and unlikely place

To weave a web"Beside the sea

With only sand and sea shrubs for his foundation.

Yet on and on quickly, quietly

Back and forth spinning silver threads

Fragile enough to catch sea spray.

Fragile, yes, but subtly so

This is no web to catch sea spray

It is strong enough to withstand the night wind.

For after the tide of night

Dead fish float in and are left drying near the web

And then come flies.

16

SARAH HANSEN

Sonnet 7

Through AutumnTs mist serenely did you come

Holding, it seemed, her beauty in your eyes.

Her calmness dwelt with you as if her home

Were there among the wind, your gentle sighs.

And like the gentle murmur of a stream

You spoke, and then a portion of her heart

Came unto me, a golden sunlit gleam

That filled my soul and warmed the deepest part.

So calm, serene, yet stately as a Queen,

I watched you pass, in beautyTs splendid robe

Against a backdrop"AutumnTs painted screen

And in my heart you found a lifeTs abode.

So there you live, yet never will you know

I feel you breathe when leaves of Autumn

blow.

THE REBEL

pe Nee 2 ache Fie Pg

a: ed. 2. ORV ae - 2 2. pee? 3*

os + ys be MRED

gig PERS oe

Sea Lonely

This ache I feel is my sea ache

It comes to me often, this longing for the sea;

Today it came when I saw a thousand trees

on a distant mountain

Blowing in the wind with a blue mist over all.

I thought of the sea and I ached.

Yesterday it came when I lay on a rock.

It was a large, flat, gray rock

With the sun shining on it and the water

running around it.

I closed my eyes and what I heard was

the song of the sea.

And I thought of the sea once more and ached.

One day it came when I walked down a

lonely path.

It was raining"a mountain kind of rain,

misty and caressing.

I tasted salt on my face and what I felt

was not a tear, but the kiss of the sea.

~ And I thought of the sea once more and ached.

The ache comes often; I cannot stop it.

In my fingertips, my arms, my legs, and

heart I feel the ache.

It is there and has become a part of me

Because the sea is a part of me, and is away

The ache has come into the place of the sea.

WINTER, 1961

POEMS

Distance

Within the light your single presence

draws down refracted dust

as bright creation through

the blazing leaves a red rib

plays upon.

How might the touch dissolve

beneath the wonder of a gaze

that webs the distance with thunder.

A bell of longing

can draw one from the stream

where nightly bobbed

a shrivelled moon,

an ancient walnut next the eye.

18

by

SANFORD PEE

Seer

The years of dry grass

have reached the sea, burning.

I am no fisherman

nor carpenter of dreams

to tread on green unsinking,

nor build a crucifix of sand.

It is the slim meridian unsolid,

the equinox of is between the shafts

There is no wise dispenser

of bread, nor end written on the sea,

but only Cassandra

the tool of gods

serenely plaiting her hair

before AgamemnonTs red doors.

She smiles an absent smile

for the elders

who tread the burnt plain, expectant.

LE

of seem.

THE REBEL

Green Rhythm

We began with spring,

and chartered our Autumn Love

with the rampant growth of green.

We were old with bright memories

of yellow afternoons shot through

with bare perception of twigs.

Ours was a green rhythm,

growing in the hazy aftermath

of solitude.

And the days wound themselves

about our simple source,

drawing the fine blunt threads

of early loom into a

grace singularity.

A red gull,

the devotee of foam,

winged inland

from her island source

to announce with

savage wing

her sea-locked

admiration of all green.

And from a brilliant vision

that once possessed a tree

she spoke of green eternal

heaving with the quest for foam.

That green delineation of our form

has not withstood the measure

of the sun nor has it survived

as epitaph for mourning.

But it, thwarted by a season sure,

it has endured in subtle

folds of green the

promised harmony of Eternal Spring.

WINTER, 1961 19

ART DEPT

PHOTOGRAPHED BY JIM KIRKLAND

Torso constructed of thrown shapes with black gloss glaze.

(27� high) Schmitz

THE REBEL

Stoneware pot with freely poured earth color-

ed matt glazes allowing clay body to show

through.

(6� high) Butler

Stoneware bottle with wax-resist

and sgraffito slip decoration

showing through a matt glaze.

(15� high) Schmitz

WINTER, 1961 21

Vase with charistic throwing

rings producing a strong rhythm

on the surface beneath green

glaze.

(13� high) Schmitz

Stoney matt glaze over assembled thrown

shapes.

(11� high) Schmitz

22 THE REBEL

Multiple ashtray and wing jug

slip decorated with pale blue

matt glaze.

(6� high) Schmitz

=

Slip decorated vase with gloss

glaze.

(10� high) Butler

WINTER, 1961 23

William Faulkner

and The South

By Junius D. GRIMEs III

The novelist sometimes comes closer to discover-

ing and transmitting the essence of historical

truth than does the professional historian. oFaulk-

ner,� said the muse, olook in thy heart and write,�

and Faulkner wrote. He gave us oa picture of

the South .. . tossed at us apparently haphazard,

yet more complete because more stimulating to

our imagination, than in many volumes of detailed

family chronicles.� He has captured on paper the

traditionalism of the old planter aristocracy and

the turbulent reality of their downfall in the more

recent generations. He has successfully painted

for us the portrait of the southern patriarchal

family and has pitted their increasing inadequacy

vividly against the ruthless cunning of the rising

poor whites. Under his pen we see the decay of

the traditional South. We watch this disintegra-

tion take radically different forms in the families

of Sartoris, McCaslin, and Compson. Additionally

we see their downfall speeded by the driving thirst

for power of the Bundrens and MacCallums and

Snopeses. Here is the battle between southern

traditionalism and contemporary naturalism and

exploitation.

But in FaulknerTs portrayal of these families

he does not succumb to all the old romantic south-

ern legends. He does not transplant an aristo-

cracy en masse from England. His aristocracy,

the Sartorises and Compsons and McCaslins, is

such by virtue of hard work and qualities of

physical energy and dogged determination. The

ancestors of this group came to the South when

24

it was still virtually a frontier; immigrants, in-

dentured servants, they were all of common origin.

As W. J. Cash says, oFrom the foundations care-

fully built up by his father and grandfather, [a

~Sartoris, a McCaslin, a CompsonT] . . . began to

tower decisively above the ruck of farmers, pyra-

mided his holdings in land and slaves, squeezed out

his smaller neighbors and relegated them to the

remote Shenandoah, abandoned his story-and-a-

half house for his new ~hall,T sent his sons to

William and Mary and afterward to the English

universities. . . . These sons brought back the

manners of the Georges and more developed and

subtle notions of class. And the sons of these in

turn began to think of themselves as true aristo-

crats and to be accepted as such by those about

them"to set themselves consciously to the elabo-

ration and propagation of a tradition.� The aris-

tocratic families in Faulkner have passed this

point where they wrested the land from the wild-

erness. But Faulkner implies this background

of common origins and the rise of the planters

in Sartoris when he says that old Colonel Sar-

toris could watch from his veranda-the two trains

a day that ran over the railroad he had built,

seeing them oemerge from the hills and cross the

valley into the hills, with a noisy simulation of

speed.� The Sartoris legend dominates the book,

even though its founder has been dead for years.

Of Colonel John Sartoris, he says, ofreed as he was

of time and flesh he was a far more palpable

presence than...� many of his living descendants.

THE REBEL

Here was one of the southerners who had laid

such stress on the inviolability of personal whim,

full of ochip-on-the-shoulder swagger� and puerile

brag, and generally ready to oknock hell� out of

anyone who dared to cross him. Faulkner de-

scribes him as such a man. In Sartoris, old man

Falls, an aged contemporary of the Colonel, re-

lates the incident concerning the Colonel and two

carpet-baggers who brought negroes to vote. The

Colonel just sat calmly in the door of the polling

house and looked. The two men quailed and ran to

their boarding house and the Colonel said, oAll

right, niggers, you wanted to vote, vote!� The ne-

groes scattered. Then the Colonel picked up his

derringer and walked with dignity down the street

to the boarding house and up the stairs and shot

the two yankees. He came out and apologized to the

landlady and said he hoped she would have the

mess cleaned up and send him the bill. This is

the description of a man of violence, but this

violence was not unnecessary brutality. It was a

product of the period, fixed by social example.

For such men this action was the only really

correct and decent relief for wounded honor.

Further, what would today appear as useless

risk of life was part of the established tradition of

the time. Even in the vices of men like John

Sartoris, there was brilliance and magnificence.

One observer, Judge Baldwin, says of such a man,

oAttachment to his friends was a passion. It was

part of the loyalty to the honorable and the chival-

ric. ... He never deserted a friend. .. . Starting

to fight a duel, he laid down his hand at poker,

to resume it with a smile when he returned, and

went on the field laughing with his friends, as to

a picnic.� Thus in the opening pages of Sartoris,

Aunt Jenny, a last remnant of that brilliant gener-

ation, relates the story of her husband Bayard

Sartoris. He was a captain under Jeb Stuart and

on a foraging party behind enemy lines, he heard

a captured major say, o~At least General Stuart did

not capture our anchovies. Perhaps he will send

Lee for them in person.�

o ~Anchovies,T repeated Bayard Sartoris, who

galloped nearby, and he whirled his horse. Stuart

shouted at him but Sartoris lifted his reckless

stubbon hand and flashed on; and as the General

would have turned to follow, a yankee picket fired

his piece from the roadside . . . and behind them,

in the direction of the invisible knoll a volley

crashed. A third officer spurred up and caught

StuartTs bridle.

o Sir, sir!T he exclaimed. ~What would you do?T

WINTER, 1961

oStuart held his mount rearing . . . and the

noise to the right swelled nearer. ~Let go, Alan,T

Stuart said, ~he is my friend.T

o~Think of Lee, for GodTs sake, General!T the

aide implored. ~Forward!T he shouted to the troop,

spurring his own horse and dragging the General

onward....

o*And so,T Aunt Jenny finished .. . ~Bayard rode

back after those anchovies, with all PopeTs army

shooting at him. He rode... right up the knoll

and jumped his horse over the breakfast table

and rode it into the wrecked commissary tent and

a cook who was hidden under the mess stuck his

arm out and shot Bayard in the back with a der-

ringerT.�

Further, the first Colonel John Sartoris had been

conscious of a deep sense of moral obligation to

his less fortunate neighbors. He must set them

examples of conduct too impecable to be question-

ed; he must advise them correctly and guide them

away from trouble; there is no place in his ethnic

ideology for bland mistreatment of any man, white

or black. He must act according to tradition and

honor, but these traditions as yet are not inflex-

ible. In short he must be a patriarch. At any rate

the poorer classes did not look upon him with

hatred or even envy. They saw in him the father

image, and so old man Falls could say to the

ColonelTs grandson when he returned a pipe given

him by the Colonel many years before, oI reckon

ITve kept it as long as Cunnel aimed for me to.

A poT house ainTt no fitten place for anything of

hisTn, Bayard. And ITm gwine on ninety-fo year

old.�

In John Sartoris the reader sees gentility and

a figure of respect. This is also evident in the

fragile figure of Aunt Jenny Sartoris, and to some

degree in old Bayard Sartoris, the banker of a

later generation. But the majority of the charac-

ters in Faulkner are the sons and grandsons of

these soldiers and builders. They have lost, to a

large degree, that knowledge of common back-

ground with the lower class southern whites. They

have developed a striking self-consciousness and

have grown more complex. TheirTs was not the

burden of weary hours in the field that their an-

cestors had known. These sons and grandsons

have gone to the best schools in the country and

have grown scornful of the common man. They

are haughty, with the pride of possession and

birth completely over-riding that gentility and

kindliness that had for so long perpetuated their

system. As Cash suggests, even at the peak of

25

their power, the southern aristocrats could not

endow their subconscious with the calm certainty

bred of the artistocratic experience. Within their

inmost confines they carried nearly always the

uneasy sensation of inadequacy for their role.

The result, especially in the later, less vital gener-

ations, was a marring of the true loveliness of the

aristocratic manner, a too heavy condescension,

the too obvious desire to impress with their rank

and value. And if this was inoffensive or at least

ignored at home in the presence of neighbors, it

appeared overbearing and brutal away from home.

Especially was this characteristic evident in the

presence of anyone suspected of doubting or not

being sufficiently impressed by these claims. Thus

the younger generations of Sartorises and Comp-

sons have reached that inevitable point in the de-

generation of their class, where upon contact with

outsiders, or non-sympathetic, even antagonistic

neighbors, the sense of inadequacy is all consum-

ing. Their responses to this modern situation are

varied. What Faulkner represents as reckless self-

destruction in the Sartorises is a slower but more

extreme and tragic disentegration in the Comp-

sons. When Jason Compson turns from clan loyal-

ty to class awareness and false pride in The

Sound and the Fury, he repudiates not merely

his inheritance, but a way of life. Of all this young

generation only in The Bear, when Isaac Mc-

Caslin decides to forego his heritage and expiate

the evils of the past, is there any intimation of

any resolve.

But if these later generations of the aristocracy

were degenerating from the inside, they also

were being pushed by an outside force. This ex-

terior force was the ruthless and amoral drive

to power of the poor whites. This group is intro-

duced in Sartoris. They were members of a

oseemingly inexhaustible family which for the

last ten years had been moving to town in driblets

from a small village known as FrenchmanTs Bend.

Flem, the first Snopes, had appeared unheralded

one day behind the counter of a small restaurant.

.. . With this foothold and like Abraham of old,

he brought his blood and legal kin household by

household, individual by individual, into town and

established them where they could gain money.

Three years ago, to old BayardTs profane astonish-

ment and unconcealed annoyance, he became vice

president of the Sartoris bank. . . .�

These Snopeses were, as much as the planter,

a product of the soil and even more of their era.

With the incipience of the Civil War they had

26

come into their own. They had, with cunning,

hoggery, callousness, brutal unscrupulousness and

downright scoundrelism, waged their own private

war upon both sides, turning everything to their

own profit. Among its members this family could

list idiots, thieves, murderers and numerous other

types of unsavory characters. Faulkner has been

accused of sensationalism in their treatment, but

this is not altogether fair. While he does indulge

in quite vivid descriptions concerning the more

degenerate members of the tribe, he does so for

a purpose. For example, his picture of the idiot,

Icky Mope Snopes, in The Hamlet, is carried to

the extreme; but his treatment is at least partially

sympathetic and arouses a certain pathos. He

illustrates the complete ruthlessness and lack of

any ethical conscience in the Snopeses when they

turn the boyTs weakness into a sideshow for per-

sonal profit.

Of course all of FaulknerTs poor whites are not

of such calibre. In Sartoris, the family visited

by young Bayard upon his grandfatherTs death

is aptly described by Cash. A certain softening

of the backwoods heritage takes place and the

members of this group otook on, under their

slouch a sort of unkempt politeness and ease of

port, which rendered them definitely superior, in

respect of manners, to their peers in the rest of

the country.� Here is a poor family that, even

so, had a okindly courtesy, an easy quietness, and

level-headed pride� that is identifiable at times

with the best manners of the old aristocracy.

But for the most part this is not the case. The

majority of FaulknerTs poor whites are true de-

scendants of Ab Snopes. Ab had a compulsion.

He not only felt spite and envy for the planters,

he was consumed by hatred for them. For some

inexplicable reason he had an extraordinarily vivid

sense of being brutally and intolerably wronged.

Possibly this was because he lived at a time when

the old frontier individualism was dying out and

the social structure was becoming fairly rigid. If

there had ever been any opportunity he had not

availed himself of it; but in the story Barnburning

he, as the patriarch of the clan, breaks the way

for the family invasion by threatening to burn

the barn of any landowner who opposes him.

Thus in The Hamlet his son Flem is hired as a

clerk in a store in FrenchmanTs Bend in the hope

that he will keep his father from burning the

storekeeperTs barn. From hence he eventually

takes over the entire village, and from there he

goes to the town of Jefferson and vitiates the

THE REBEL

surrounding country-side like the oflow from a

poisoned stream.� These were the people into

whose all-engulfing lust for power the Sartorises

and Compsons and McCaslins were drawn.

To thoroughly understand why these families

fell victim to the Snopeses it is first necessary to

understand the complete repugnance of the plant-

ers (after the class had attained true develop-

ment) to anything that hinted at deception or

chicanery. And these elements were the life blood

of the SnopesTs rise to power. The planter aris-

tocrary had already been described as members

of oa dying class who cling to their self-loving

myths of the past, glorifying themselves with the

gaudy legends of their ancestors until the sound

of their own names becomes to them like ~silver

pennons downrushing at sunsetT.� The old tradi-

tionalism had solidified until it emboidied princi-

ples which almost precluded any action in the

world of the Snopeses. Here is the essence of what

OTDonnel calls the conflict between traditionism

and the anti-traditional modern world in which

it is immersed. The Sartorises must act tradition-

ally, or with an oethically responsible will,� but

the Snopeses acknowledge absolutely no ethical

responsibility. Thus the quandary.

The whole body of FaulknerTs work presents, in

various social conditions, an elaborate series of

moral contrasts that comprise the responses to

modern life illustrating the various moral courses

open to the South. For example Quentin Compson

in The Sound and the Fury is the only identi-

fiable figure from the Sartoris world. But his re-

action has been to oformalize� or lose the ac-

curate sense of the tradition and substitute a

romanticized version. He ultimately realizes that

he is totally ineffectual in the Snopes world and

with this realization of his failure he kills him-

self. Jason Compson, QuentinTs brother, survives

and holds his own against the Snopeses, but only

by becoming a sort of glorified Snopes himself;

and FaulknerTs image of Jason is by far the most

unpleasant and degrading one of any of his char-

acters. Faulkner obviously has no use for the

Snopeses, but he has even less use for the apostate

traditionalist.

Also in The Sound and the Fury Candace

Compson feels her sense of quality has been vio-

lated by a Snopes and hence stems her conflict.

She is faced with either the outrage of some

quality for which Aunt Jenny DuPre Sartoris

ostands as a symbol as in Sanctuary (or Sar-

toris), or the acceptance of a role which means

WINTER, 1961

a subjective sense of exclusion from her world.�

Aunt Jenny is the shining example of old southern

womanhood"oher delicate features and white

hair, her heroic past, including her dance with

Jeb Stuart and the times she dominated carpet-

baggers and confederate skulkers by her com-

manding presence.� And when her niece-in-law

confesses in a later story that she has been black-

mailed by a Snopes, Aunt Jenny dies in her chair.

This was the final indignity to the Sartoris stand-

ard, destroying her will to live.

For a good contrast between the Sartoris ideal

and the Snopes reality there is Horace Benbow

as he appears in Sanctuary. He must make the

Sartoris values prevail in the Snopes world. The

opening scene presents the contrast between the

traditional and the naturalistic, exploitive atti-

tudes by placing them in juxtaposition. Benbow

is afraid of Popeye, the killer and sadist from

the Snopes clan, who has him at gunpoint near a

small spring. But even under these circumstances

when Benbow hears a Carolina wren sing he trys

to recall its local name. He says to Popeye, oAnd

of course you donTt know the name of it. I donTt

suppose youTd know a bird at all without it was

singing in a cage in a hotel lounge, or cost four

dollars on a plate.� Popeye has no feeling for

nature, but on the other hand he is a definite part

of nature. While Benbow may have some aesthe-

tic appreciation that Popeye does not feel, he is

still on the outside looking in. Popeye is, in the

story, the incarnation of those bestial qualities

that exploit nature, but at the same time are an

intricate part of it. Because it is his world Popeye

eventually conquers, and Benbow, for all his ap-

preciation, becomes merely another ineffectual

anachronism.

This is William Faulkner. He presents on one

side the people who represent or accept the Sar-

toris standards"the DeSpains, the Sutpens, the

Compsons, the Benbows, the Griersons, the planta-

tion aristocrats and civil war heroes. On the other

side are the Snopeses, Ab Snopes, the barn burner ;

Montgomery Ward Snopes, the draft dodger; Mink

Snopes, the murderer in the Hamlet. Here are

clowns, pimps, blackmailers, perverts, sadists,

idiots, and so on, operating through othat technic-

ally unassailable opportunism which passes among

country folks"and city folks too"for honest

shrewdness.� And all of these become as palpable

under the genius-guided pen-of William Faulkner

as the ghost of Colonel John in the opening scene

of Sartoris. s

27

WHERE IS HARRY STEWART?

By R. ELFRETH ALEXANDER

It was a nightmare come true. Incredibly, I

can still remember every fantastic detail. It was

a warm evening in August, 1943. The birds,

hundreds: of martins, it seemed, were dipping

and swirling about the yard, creating dark streaks

against the lavender and pink sky. The cedars

were lacy and the pear trees thick and green

and heavy with their fruit. Frogs croaked mourn-

fully, uncannily rhythmic. The waves of the Albe-

marle Sound lapped the shore quietly, and tall,

matchstick-like pines swayed gently. The Scarlet

Letter lay open and unread in my lap, and I would

have been asleep but for the hard, uncomfortable

wooden corners of the chair continually prodding

me back into consciousness.

The slow, stealthy movement at the end of the

porch touched off an alarm in my brain. It went

off slowly and cautiously, and I recall fixing my

eyes on the pear tree before turning my head

sharp and quick. My heart shut off my breath,

and my eyes flew open wider and fixed themselves

unblinkingly on four figures at the end of the

porch. There were a swarthy blonde, stocky, with

thick muscular forearms extending from the odd,

colorful shirts, which hung loose about their

waists. I sensed a strangeness about them, and,

paralyzed, I gazed somehow at once into three

pairs of pale, blue, opaque eyes. The fourth person,

who had been obscured by the porch railing, was

bending now and sliding his feet cautiously on

the porch. He was light, too, and dressed in a

28

white T-shirt and khaki trousers such as the ma-

rines wore at the base nearby. All the figures

began moving, and I saw them as if they were

reflections in water and moving in liquid, melting

motions. The figures came along the porch on

their bellies, under the window, and to my chair.

One of the men held a carbine or gun of some sort,

and as the shirts fell away from the bodies of the

other two, I saw leather gun holsters. I sat in a

state of lethargy, my whole body as uncontrolled

as if a streak of electricity had flown through it,

dismembering nerves, and leaving them twanging

like a popped elastic band. Then, the serviceman

crouched by my chair. Instinctively, I drew away

from him, and tried to raise my body. Fright had

left me helpless, and as I sat, dumb and uncompre-

hending, my eyes staring hypnotically into his,

he motioned with his head toward the house, and

asked, o~Is anyone home?�

The question went into my brain and stayed.

I was unable to form an answer. oIs there any-

one inside?� he asked again, and the urgency, the

demand in his voice made me say, sounding

strange and hollow, oThere is no one here but me.�

I saw and felt the relief in the men and the

marine, and as they rose to their feet, I could

see in their faces also their satisfaction of my

youth, of my femininity.

They never doubted for a moment that I had

not told the truth, and no longer bothered to shield

themselves from anyone inside the house, but

THE REBEL

peered cautiously toward the field and the dirt

road that ran a mile to the highway, obscured by

tall corn.

oGermans,� the marineTs voice thudded, and

the word pounded into me like molten fire, deaden-

ing and burning, spreading in engulfing waves,

digging scorching hollows of terror and pain.

oWe need a motor for our boat,� the tallest one

with the carbine said in a soft, steel-core, British-

accented voice, his whole confident manner in-

congruent with the situation.

oGet them a motor, honey, and weTll be all

right,� the marine said. His voice was taut, but

controlled, and the pronouns othem� and owe�

told me that he was not a willing member of this

alien group"that he was a compatriot.

I rose and led the way off the porch to the

shed. I flung open the door and stepped back, in-