[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Laura Marie Leary Elliot

Narrator

Dr. David Dennard

East Carolina University

Interviewer

October 17, 2008

Joyner Library Rare Book Room

Greenville, North Carolina

[Interview begins at 1:46]

DD: My name is David Dennard. And today I have the distinct honor of interviewing a very important person in the history of East Carolina University. This is Laura Marie Leary Elliot. The interview is taking place in the Special Collections department of the ECU Joyner Library. Specifically, we are in the rare book room. And today's date is October 17, 19. Not 1908, but 2008. And we're very happy to have Mrs. Elliott back on the East Carolina University campus. And you will learn more during the course of this interview why I've said she's a very important person in the history of East Carolina University. So this point I'd like to say, welcome back. Mrs. Elliot. We're very happy to have you on campus. (2:53)

LE: Thank you.

DD: I'd like to begin the interview by asking you, if you would, to talk about your period of matriculation at East Carolina University. When were you on the campus of East Carolina University? (3:10)

LE: Thank you, Dr. Dennard. It is a pleasure and an honor to be here this morning. I hope I can answer as succinctly and as accurately as I can remember all of your questions. I graduated from high school in 1962 and upon graduation, I was accepted at another college within the North Carolina educational system. But I was told that I would be attending East Carolina University. Not my choice, not my decision. I did that in 1962. I remember a celebration with the Ledonia Wright Cultural Center about five or six years ago and it was called the African Americans first. And at that celebration, I remember seeing my name on the program as entering East Carolina in 1963. I'd like to clear up something here and I think the reason that that happened is because my name appeared on the to the 1967 commencement exercise. And what happened was in June of 1966, without guidance or any counseling from the university, I discovered I did not have enough hours to graduate in June. And with the encouragement of my parents, and especially my mother, she thought I should make up those hours by doing student teaching. So I did student teaching in the fall of 1966. So I completed my requirements for graduation in 1966. However, at that time, we did not have, as to my knowledge, any mid-year graduation ceremonies. So then they propel me into the next class to graduate although I graduated - requirements that I needed to graduate were accomplished in 1966. Just clear that up. (5:31)

DD: Excellent. I was a little concerned about that because I think in the history, prepared by Dr. Mary Jo Bratton, East Carolina University: The Formative Years, 1907-1982. She lists your entry date at East Carolina University is 1963 and your graduation date is 1966. But you say it's 1962 is the date that you entered?

LE: That's correct.

DD: And you earned a degree.

LE: I earned a BS degree in business administration with a concentration in accounting, and also a teacher's certificate because I did my student teaching and methods courses to qualify for a certificate in teaching. (6:22)

DD: Okay, excellent. Now, if possible, and I know this is possible, will you tell us how and why you became the first African American to enroll at ECU as a full time student?

LE: As previously stated, it was not my decision. How I did it was a mystery to me. And during that time, my father and my mother were very active in civil rights and in this movement at the time, and they were also friends with the first black physician here in Greenville, who was the late Dr. Andrew A. Best and not. According to them they had met - I never knew of any of this - but anyway, they met with Dr. Leo Jenkins and asked him if it was possible. Did he think there would be any real danger? Because my father was concerned about my safety of me enrolling in East Carolina as the first full time African American student. So they got their heads together and this was on. A week before the beginning of school and my father and mother came home and told me that you will be attending East Carolina. Through tears and disappointment of not going to the college of my choice at that time, I didn't really have a choice. You know, these were my parents and my parents, you know, told all of their children what they were going to do. We had choices if they agreed with their choices and that was just the times. So I can't tell you why I did it, I believe it is because I wanted it to be an obedient daughter. That's the only good reason I can tell you that I came to East Carolina. I had no intentions of breaking any barriers or doing anything, but I was a pretty good student in high school. So they felt that because of that record, I could do it. So there we are. (8:55)

DD: Okay, excellent, you've anticipated my next question to some extent, because I would like for you, if possible, to sketch for me a portrait or profile of Laura Marie Leary in 1962. And I think you indicated that you were a popular student and you were involved in your high school activities. But if you would elaborate on that a little bit. (9:24)

LE: Yeah, I was the 10th - I have 13 brothers and sisters and I was the 10th of that crowd. My parents were farmers in Pitt County. My father owned a farm in the, I think, far eastern part of Pitt County, near Craven County, and I was. My address at the time was Vanceboro. So I'm not a native of Greenville, North Carolina, I'm a native of Vanceboro, North Carolina. Prior to enrolling at East Carolina, I was the. A most popular high school student. Matter of fact, my high school graduating class voted me "best all around," I was the valedictorian of my class, I had many friends and was very popular, I thought, with my fellow students. I was involved in the, at that time I'm not sure what it was called - I feel like I'm talking about olden days - but it was I think it was still called the Student Council Association. I was involved in that. I tried my hand at a little cheerleading. I was on the debate teams. I also was on the oratorical traveling circuit at that time, and I did win some awards in an oratorical contest in Pitt County and the state of North Carolina. So, and also involved in my community, as I said before, my parents were very involved in the civil rights movement. And my father was one of the first people in our community to make sure everybody was registering to vote. And, he sort of made sure his children were along to see the process. So we got involved that way. And I was also involved in my church, in their youth ministry. Matter of fact, when I first enrolled at East Carolina, my pastor at the time, allowed me to stay at his house for the first quarter at that time - I don't know if you have semesters now or not - but the first quarter at that time I stayed with my pastor. So I was very much involved in my community, church and my community activities and anything that came up in the community, my mother and father were sometimes the leaders and of course they the children had no choice but to be involved. (12:08)

DD: Now, where did your pastor live? Did he live in Vanceboro or Greenville?

LE: He lived in Greenville Terrace, so it was a suburb, I guess of Greenville. It was out towards Bethel.

DD: That's correct. That's correct. So is it fair to say that you were quite familiar with the civil rights movement, I mean, the activities that were taking place across the nation and '62?

LE: Yes, I was. I was familiar, as familiar as a country bumpkin could be you know, we were kind of isolated down there in the county. So I think I became more familiar with it once I left the area, because upon leaving the area - soon after leaving the area, I went to Atlanta, Georgia, so. And then I associated with... I palled around with some of the Martin Luther King family members and of course, I got to know a lot more history of the civil rights movement.

DD: So you palled around with some of the King family.

LE: Yes

DD: Members of the King family in Atlanta.

LE: Yes.

DD: And a lot of things were taking place in that part of the South. (13:30)

LE: Right.

DD: Then and Now, how well do you think, and I think you've already been alluded to this, based on the activities in school, based on the fact that you were valedictorian of your high school, that you were prepared to go to college, but as we know, in some cases, college. It requires one to make the transition from high school and a lot of times Vales and Sales do not do well in college because they don't make that transition. So I think I still need to ask you, do you think you were prepared for college - for the college experience when you arrived at East Carolina University in 1962?

LE: I think in some ways I was prepared. But in a lot of ways, I was never prepared for the experiences that I encountered - upon arriving here. I always felt loved, always felt I belonged, always felt a part of the group, always felt that I was somebody. And I think when I came here my spirit was broken - it was just broken and I think intellectually, I was prepared but emotionally I was drained of my real. The real me. And subsequently I may not have done - I know I didn't do as well as I could have done, had I not had such feeling of loneliness and fear. I was not prepared for the fear I encountered here. I was always a free spirit, I was always just out there, friendly person, but I just felt completely isolated and I was not prepared for that. (15:37)

DD: Free spirit, very outgoing person. But when you arrived on this campus, you experienced a spell of loneliness. I recall just briefly - Gwendolyn Brooks, the poet laureate State of Illinois for a period before she died. She said in one of her pieces that "I like being alone, but I don't like loneliness." And there is a difference, because I can choose to isolate myself from others for a period but I don't like to be alone. And being the first and only African American student on campus at East Carolina University, you are saying that you felt alone and that had an impact on your emotional spirit. You were prepared intellectually but not prepared emotionally for what you would encounter, okay. We'll come back to some of that a little later. Now, if you can recall I'd love for you to talk a little about your freshman experience. Your orientation, if you remember, freshman orientation. When you first arrived on the campus of East Carolina University - And we should say for the record that this was not "East Carolina University" then, it was "East Carolina Teachers College", before "East Carolina College", it was called "ECTC". But do you recall anything related to your freshman orientation? (17:38)

LE: I can recall that I had no freshman orientation as we see it today. My daughter - my children - went to college and there was a period before enrolling in a class that you had an orientation period. I did not have that. Mind you now, I was told I was going to East Carolina a week before classes started. I came here, filled out my application - and at that time I don't think I had taken the SAT test and there was one being held on. administered on the Saturday before classes started Monday. I took the test on Saturday and to this day, I don't know what I scored on the SAT. I started classes on Monday and went to the registrar's office the Saturday, paid my tuition for some reason - I think I got a schedule of classes. I never met with a counselor or anybody to project what I would be taking, I was given a list of courses to take started class Monday morning. (18:54)

DD: Gee wiz, that's a fast process. Now how did you get to this campus who brought you?

LE: My father, my parents brought me to the campus.

DD: Mother and father?

LE: Mother and father to the administration building. I walked in, asked to see the registrar, I was told by Dr. Bass or somebody to ask to see the registrar. I mean, I had very limited knowledge of. I was just like a robot. I was just going where people told me to go, you know, so I saw the registrar and he said, have you applied and I told him I thought I did, but I don't know. So I filled out another application, I remember distinctly I put on the application for race I put human because he said it had to go before somebody to review it and etc, etc. And as I talked to him, I. my dad had given me a blank check and signed his name. And he said, this will be X number of dollars for having you and I signed the check, filled it out and gave it to the registrar. And his next words to me were "you will never make it here". Real nasty. So, let me try. So I went to the registrar and I cannot to this day remember his name. He just said you will never make it here. So that was my introduction. That was my freshman orientation. (20:28)

DD: Do you recall any of the students completing the process at the time that you completed the registration or you.?

LE: Oh, no one had completed the registration at that time to. No other African American that I knew or had heard had completed an application. It could have been and they were denied, I don't know. But I was in his face like, it wasn't like I'm writing from another state or another city. My father just said just go in there. I was 17 years old. So I went. And I'm sure Dr. Jenkins and Dr. Beth may have talked to the registrar and he would had anticipated my coming. But I'm just saying, you know, there were no prerequisites, no orientation, just bail. You're here. Let's go to school. (21:28)

DD: And when you - while you're completing your paperwork at the registrar's office, you don't recall any white students being around, do you or do you?

LE: No. All I remember... I think we were in a room something similar to this, maybe not this sophisticated, but it was, you know, an isolated room, a conference room, sort of - his office maybe, I remember him at a desk. So it was not in the open or there was no access to other people at that time. And they may have thought I was just coming in to clean up his office. I don't know, you know if they saw me.

DD: So you are on the campus now, completing the registration process, and you have your classes ready and you are off to class. Okay. So let's move to your actual experience as a student was in fact, attending classes, going to the dining hall, visiting the library and doing those things that college students do. What was a typical day like for Laura Marie Leary? (22:47)

LE: I can give you like - excerpts from days. I cannot tell you one day I did x from morning to evening, but I can give you things that have happened during a day. As far as the dining hall is concerned, I think I may have gone to the dining hall during... Other than at the end of the dining hall hours of operations, maybe one or two times, because my first experience and go into the dining hall, I was in line and I saw those steps today and it brought back some memories. I was in line going up the steps, and it was crowded, students were behind me. And I was walking up and all of a sudden, I felt this jolt somebody just pushed me forward on all of the students in front of me. And of course, they in turn pushed me back. So I was just this tug of war between the front of the line and the back of the line. And that went on two or three times and I just like you know, I was in the Martin Luther King era, I said let me just try to be non violent. But after a while that just got so upset. I decided, okay, what can I do to just really just have some peace here. So what I did I turned around backwards because the initial blow came from behind and the people in front I think they were reacting to me. They thought I had done that deliberately. So I turned around and I walked backwards up the steps to the rest of the way to the dining hall. And how many have gone back one or two times before doing the crowd, but I made it my business to watch my clock to make sure I found out the very last minute that I could go in without a line at the end of the operations, wrap operational hours and get something to eat. Didn't ever eat in the cafeteria, always bought it back to the dorm. Mind you now, my first year I lived in. With my pastor the first quarter, and the second and third quarter of that freshman year I live with my aunt and uncle who lived in Greenville, off of Fifth Street. And I would not attend the dining hall at all during that time because they were my room and board so I didn't have to eat on campus. But the following year, my sophomore year, as I said, I tried that two or three times, and it was just it was really frustrating. And I was scared and you know, I just didn't know what it would erupt into. So I just decided I would come and get what I need and go back to my room. So that's what I did. And fortunately at that time, I don't know about your experience, but I had sisters and brothers in college at that time. Also, as I said, we had 13 of us, 10 of us went to college. So they were all others in college and they were telling me about if they didn't use their ticket, you know, for a certain day and a certain meal, they would lose that money. But at East Carolina, we had coupons with like money attached. So you can use it anytime, so I didn't lose any money by not going every meal or eating in the cafeteria. So I can sort of, you know, go when I wanted to, get what I wanted at any time of the day. But as I say, you know that that became such a frightening experience. So I got as much as I could and I was real skinny then too. I probably weighed about one ten, you know. So it worked, in one way. But that's my experience with the dining hall and I was coming in the library today. This is the first time I've ever been in this library. The first time. And I think I just didn't go places on campus because I was so afraid and you know, I just thought that someone was going to attack me from someplace you know, and I didn't learn until about 10 years after I graduated that you know, I had my own Secret Service entourage. I was told by. Thank you. I was told by some of the custodians here. Excuse me. That they would watch me when I moved on campus, from my dorm to all my classes, you know, they had a relay going, you know, there was one at the end of my dorm and there was another one stationed around the corner. I didn't know that at the time, so I was still afraid. But they told me afterwards they had my back. So I think a reason I didn't go to a lot of places on campus was because I was just afraid. And as far as doing things that were required from the library, I would visit the Greenville libraries and do my research and write my papers from there. I'm sorry I got a little emotional. (28:04)

DD: That's perfectly understandable. Reflecting back on an experience of this sort. [unclear] control myself. And I've read these accounts of students who enter Little Rock High School, how they talk about their experience. Charlene Hunter-Gault at the University of Georgia and, you know, in '62 what was happening at Ole Miss with James Meredith. They saw a different experience when the debate took place there a few days ago, but in '62, that was a riot - a war zone. And with Governor Wallace standing in the door of the University of Alabama saying "segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation." I mean, these were really difficult times and this was a battle zone, you know. If you were there, simply trying to be a student, there were other folk there trying to do everything they possibly could to say you're not wanted here you don't belong here. And just reflecting back on that is tough.

LE: I'm getting better, I'm getting better. (29:28)

DD: We are so proud of y'all because you all were warriors, really heroes and heroines. And I don't know if I would have had the strength to do that so I certainly appreciate you reflecting on that. And the fact that you had to navigate through that dining hall [unclear]. But not feeling comfortable enough to use the library. There's a part of the whole college experience and [unclear] you have to go off to the public library in the city. That's tough.

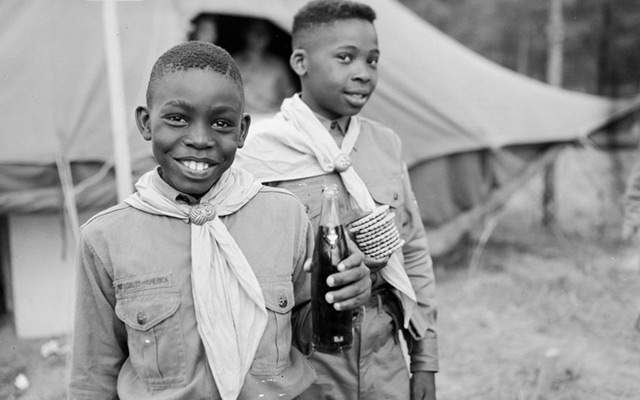

LE: Yeah, I think the reason though I didn't use the library because I felt so exposed because for a long time, I just don't think students thought I was. The other students, the white students, thought I was a student. They thought I was part of the custodial staff because I was even told one day coming out of a class. There was one custodian and they were just - I just did not know this and this is why it's just so touching that they really looked out for me. And in one of my buildings, there was one lady, Mary Taff, never shall I forget her name, would see me come into class. She was standing outside her little closet and she just made sure I got in class and one day I was coming I was probably running late because it was typical of me to always be on time or early, just didn't want to draw calls. Call any attention to myself and didn't want people staring at me when I walked in class. And she saw me one day. She and I was a little early. She called me and she said, do you have a minute and she took me in her closet. And in her closet, she had a Pepsi in her freezer that had ice in it and she gave it to me. She said every day now when you come back, come a little early and come in my closet and we can just chit chat little bit. And I just felt - I just feel so good about that, because I thought well at least there's somebody over here that you know, may like me, you know, and showing some kind of hospitality. But it was the custodial staff that helped me make it through and I just have always tried to talk about them. I don't know one person by name. I don't even know the other people by name. But she told me years later, about 10-12 years later, how all the men on campus were acting as if they were sweeping or raking or something. But they had their eye on me until I rounded the corners that I needed to get to class. And I just, I'm just so grateful to them, you know, and I just I don't know how to thank them other than to say, all of them that worked on custodial staff at that time. So that was some. That was typical in some of my days here at East Carolina. (32:36)

DD: You mentioned your pastor a few times, that you stayed with him. Is it possible you could tell us who this person was?

LE: Yes, it was a Reverend John Taylor. John Taylor, Reverend John Taylor and his wife were my host family, my first Quarter here at East Carolina

DD: When you left school on some of these days did you talk with them? Did they. Did you have any prayer sessions?

LE: We had prayer sessions every day. I mean, just about. I mean, I don't know if I shared with them. I mean, you know, at the time I didn't think I needed - I had a right to complain, you know, I couldn't complain to anybody. I remember one sister one break in between classes. We just had a jam session. We cried and cried; didn't want to come back, I didn't want to do this. And of course after we had all that was over she said, you know, Mom and Pop expect you to go back and I said I know, so I went back and just with. But that's about the only person I think I really opened up with about what was really happening. Because I didn't want it to feel that I was trying to find a reason not to go. I wanted it, I started it, and I wanted to finish it. So I didn't talk that much about the experience here. But of course, we always had prayer and I think, my faith and my real real belief that somebody was here holding me up, kept me through, helped me get through. And I believe in angels and, and those custodial workers were my angels and I just cannot say enough about how appreciative I was of that, because that was really, really afraid. I just didn't know how. I just don't know to this day. I just sometimes, and I used to do this more often than I do now. I would talk to my husband and my children. And I just cannot remember being here for 4 years. I cannot remember it. I just, I remember coming and I remember leaving, but in between is just like a - I don't know if I'm suffering from selective amnesia or what. But it's just hard for me to recall. I, you know, I sometimes think about "what did I do my sophomore year? Did I ever go to any concerts? What was my social life like?" I just cannot. I cannot remember. I mean, and to me, that should have been one of the times of my life. My sisters and brothers were talking about, you know, what a grand old time they were having at A&T and North Carolina Central, at Shaw University, in North Carolina State even at that time was a little bit better than East Carolina. And I just can't remember the glory days, I just cannot remember them and it too, sometimes. Not as much. Now of course, you can't tell that today but it just hurts me so much to know, that's a part of my life I can't even share with my children, you know, and they asked me about, what was it like when you were in college? Well, you know, and I guess and that's about all I can say, you know, but both of them had wonderful experiences. So I, my daughter, not so much, but it was better than mine. So it's just, it's just, it used to get me so bitter, so bitter, so bitter but I did not succumb to bitterness. And that was part of my upbringing. (36:36)

DD: Now, it's been a long time since that period and just wanting to know if you've had any conversations with other students who may have been pioneers in the way that you were. Persons who integrated high schools, colleges. Have you had any conversations with any of these persons?

LE: No, I have not. And you know, I have very been. I have been very reluctant to tell anybody I was the first black student to enroll at East Carolina. I don't know why I just, I just didn't feel that was something. I wasn't proud of how I was treated, I wasn't proud of my experiences. And I don't know, I just I don't know if I was that proud of myself. I just thought I was made to do something I didn't want to do. And, you know, if it had been my choice, if I was one of these Stokely Carmichael-people, you know, I'm going there and I have a right to be there, this is what I'm going to do. I think I would have felt a little bit better. But it wasn't my choice. And I don't hold it against my parents. All my parents were trying to do is get an education for their child. And that's all I wanted. You know, I didn't want the other baggage that went along with that at that time. And and the reason I think things were kept under, under, under, kept under control as much as because of my parents. And and Dr. Best, you know, there was like a secret pack. There is no gonna be no announcements. There were no newspaper coverage. No marshals, nothing. It was just if I was not here, that made me feel even more like a nobody, you know, nobody cared that I was here. That's the way I feel. You know, they're like I said, there was one black newspaper in Durham, North Carolina, and I can't remember that paper, but you may know it. It was a I'm not sure if it's still even in print now. But they carry just a snippet about a black student enrolling at East Carolina and I think my mother has the clipping someplace. I don't know where it is. But that's all I remember. There was nothing in the Daily Reflector, nothing. So, I was a nobody, you know, so. (39:07)

DD: Because we see that kind of tension devoted to.

LE: James Meredith went to Ole Miss the same year I did.

DD: '62 that's correct.

LE: And he was an upperclassman, but he was - the situation was the same. So sometimes I get resentful of that, you know, but then I didn't want all of the attention either, you know, I didn't get into the paper or something, you know, but I don't know, maybe that kept things a little quieter, a little calmer. It didn't help my fears, you know.

DD: And I read something that Leo Jenkins, President Leo Jenkins, who was president from 1960 to 1978, that he wanted to integrate East Carolina University quietly on the terms dictated by the folks here and not have outsiders involved. He didn't want that to be an experience that would be forced upon East Carolina University. So maybe that accounts for the absence of media attention.

LE: I never met him either speaking of Dr. Leo Jenkins, never met him in person a day of my life.

DD: Wow, that was one of the questions I had on my list to ask, have you ever met Leo Jenkins? And you say no.

LE: No.

DD: Did you have much interaction with Dr. Best? (40:33)

LE: Yes. Yes, Dr. Best - he was my mentor, he was my solace, he was my. He just kept me encouraged. You know, he knew how hard it was and he was - he just adopted me as his little girl, you know. If you need anything, let me know. You know. I always felt I could call on him. If I needed him.

DD: A few years ago, we had an opportunity to interview Dr. Best, along with three other African American physicians that practiced in - that practice in eastern North Carolina. Jill Weaver up in Ahoskie; Dr. [Matthew] Hannibal who practiced down in Jamaica; and Milton Quigless who practiced over in Tarboro and built a hospital. And they talked about their experiences as physicians during the period of Jim Crow segregation. Dr. Best talked a lot about you and his effort to work with Leo Jenkins and others here to integrate East Carolina University. So he's very proud of what he did. In a change in template here at East Carolina University. Now with regard to weekends - go to college, we have laundry to do, we errands to run on weekends. Maybe there's some other things. You were off campus the first year? (42:24)

LE: The first year.

DD: And after that lived on campus?

LE: Yes.

DD: So if you would try to think about those years, what was a typical weekend live for Laura Marie Leary?

LE: Most weekends my parents picked me up, took me home, fed me well, brought me back to school, washed my clothes and did all my little personal hygiene things that at home. Then the third year - I think the second year, a couple of black students came - the second year. And we may have found something to do on weekends, I can't recall. I do remember one student who was killed during his sophomore or junior year, had a car. And he would take us to like Dairy Queen or fast foods or something to pick up a hamburger and sometimes I would go - he lived in Williamston and sometimes we would go home with him - he would invite us to come to his home but there were not that many weekends like that because as I said, he was only here I guess a couple of semesters and then he was killed in an accident, so.

DD: Do you recall any other experiences, other than maybe the Dairy Queen, of visiting downtown facilities? And what was happening downtown? (45:36)

LE: The only other thing I remember is going to the "Ratskeller" its a beer place down there off of Fifth Street, I think it's called - Across from the College Corner. I don't I don't know what it's called now. But some of the black students would - we would gather there but it was just just our little group with no interaction with other students at all. It was just like, you know, we were. Things were being integrated at that time. So it was just, we were just there. I mean, and we were just so stiff. We really didn't have that much fun. We just want to say let's do it. You know, let's just do this this weekend. And we really didn't have fun.

DD: Any movie theater experiences? Was there a movie theater?

LE: Roxy, yeah, I was here. I remember going to the Roxy, not to any of the downtown theaters. If there were any, I don't know. I don't. I always did my socializing and getting around in the Black community of Greenville, if I stayed here, so it was I just never felt I was integrating anything. You know, I was going to class and trying to get an education. That's all I could remember about East Carolina.

DD: Do you recall any particular classroom experiences? Do you care to talk about any of your teachers? Did they seem to treat you as any other student in the class or did they ignore you as a student there? (45:42)

LE: I felt like I was ignored in all of my classes except perhaps one, there was one professor, Dr. Francis Adams [Department of English, 1958-1968] and I don't know when he left or. And he was an older gentleman at that time and I don't know where he is today. But he is the only professor, I can truly recall, that tried to extend a cordial hand or cordial word to me. Other professors - most of them were not that kind to most of the students, but I did see interactions with others like students that were never shown toward me. So I just say they were very cold. I think they could have helped me a little bit more I think, sometimes I may not have been judged fairly. But I took what they gave me they had the last word and I just tried to stick it out, you know. (46:46)

DD: Well, we are certainly glad you did. You have touched on this, so we can probably infer and reason from what you said that the answer to this question, but I need to ask you any way specifically. Did you get involved in campus activities or organizations?

LE: None. I may have gone to a Ray Charles concert one time. And it was because it was right across the street from my dorm, I lived in Ragsdale Hall. And I went to a concert by Ray Charles one time. And I can remember - I went to one homecoming game also and I was so humiliated at that game because. I don't know about you but like I said, my brothers and sisters went to historically black colleges, and you know, doing homecoming black colleges put on the dolls, you know, everybody's in their finest and dressed up. So I had an aunt who was a seamstress and I asked her to please make me a special suit for that day and I wore my suit I was looking fine too. Everybody else had on blue jeans t-shirts and they looked at me, you know, I could just see them snickering and I was so humiliated. I just thought that's what to do at homecoming and, you know, you get dressed up so. I did go to one and that was the only one I went to and a concert during those four years. That's all I can remember. (48:33)

DD: Okay. You have answered this question in a partial way, about. I wanted to ask you, did any teachers, students, or both make a special effort to befriend you? And you said that one did, Dr. Francis Adams seemed to take a particular interest in you as a fellow human being, not just a student. But you don't recall much of others. What about students? Your classmates?

LE: There are two students and, I mean, I can say this of all the 10,000 students, two students: one Eddie Green, I don't know if you know of him but he's a he's a lawyer now I think he may have been the mayor of Dunn, North Carolina, or he lived in that area. Eddie Greene and a young lady by the name, I can't remember her last name, Lila. I can't remember her last name. But Lila and Eddie were the only two students I can remember being cordial to me. Everybody else either ignored me, threw spitballs at me, called me names and made me afraid. That's all I can remember. (49:58)

DD: Called you names in class? Or on the way to class? Or just wherever they.

LE: Wherever. Maybe not in class, there was a little bit more control. I don't want to believe the professors would have allowed that. But on the way to classes I remember coming out of my friend, the custodian, one day and I went directly into my class and one student said, Oh, we have the maids going to class today. Or they let "n's" go to class here now. I mean, that was.

DD: N's?

LE: Yeah, I retired that word, but "n's" you know what I mean. And then thrown from afar, I don't know. I don't know. It was like, they were told, do not bother her. I mean, it's like they somebody had a meeting somewhere - Taunt her, but do not violate her or whatever. And, you know, kids want to be kids, like I say we were 17, 18, 19 year-old kids and we were going. White kids were going to be white kids at that time, I don't care who told them what to do. And so some of them were very mean to me and I'm forgetting that and I'm not trying to hold any bitterness, but that's the truth.

DD: Okay, thank you for that. Right. And that touched on the next question I wanted to ask you, which is do you have any particularly positive, negative or otherwise noteworthy memories of any of your teachers and classmates? But you've answered that, for the most part, I think we can move on. And you've also said that you didn't remember being the subject of any media coverage? (51:58)

LE: Never.

[Crosstalk at 51:51]

DD: The Rebel magazine was a..

LE: Not while I was here.

DD: Student paper, but you did say that you thought a black newspaper in Durham.

LE: Yes.

DD: Carried a little story.

LE: Right, a little snippet and I'm trying to remember if my picture was in. It may have had a little picture of a cute - picture of me.

DD: Okay.

LE: When I was 17 I was real cute.

DD: Yes, I saw this - I saw this cute picture. In fact, I'm going to show it to the class. Dr. Mary Jo Bratton, who authored this book.

LE: I've never seen it.

DD: Yes, its that cute photo of you, its very cute. There's still that resemblance. (52:46)

LE: Okay.

DD: So, do you have a copy?

LE: I do not.

DD: We will see that you get home before you leave. Because that book has a pretty generous section of African American students, the first students who came to East Carolina University, the first organizations, what they were about, why they were here. They had an organization, a formal organization was called SOULS [Society of United Liberal Students]. I'll get you a copy of it.

LE: That's what I was so proud of, you know, when we came back to the American - "African American First" celebration, I saw all the first and I was so proud because I just you know, I was a very outgoing student, I would have loved to have been involved in some things. I was just too scared. That's that and I blame myself sometimes. But then I look back to the atmosphere and my husband tries to tell me that you know, don't regret that you didn't get in things, just be proud that you came through whatever you did have to come through. But I wanted to be involved in some activities and I was so proud of the students who were like, first cheerleader, first this, and the first one to be on the paper and it was just. I was really, really proud of them. (54:23)

DD: Well, we are certainly proud of that. We don't we wouldn't wish that experience upon anyone but that's what pioneers encounter. That's what trailblazers encounter, you see. So grateful to you for that. That you've stuck it out. You didn't run away. That's a nice chapter to conclude. That your parents were interested in getting you here. And it's not your first choice. But you felt that you needed to do what they wanted you to do to some extent, and this is something that happened across the spectrum parents decided for us in the 60s, what you will wear, where you would go. And I was a part of the late 60s when we said we're going to tear down all of those restrictions that in loco parentis, you know, because when you're away from college, but college was like a surrogate parent, you have to sign in the college officials had to know where you were at all times. You get rid of some of those laws in the late 60s, student protests and all the. Chrome for God's sake, participate in the Vietnam War. Why can't we make some of these decisions? So now we're at a point where parents call me and ask me, where's my son or daughter? I don't know, they could be in Alaska on the weekend. And all I could possibly do is give you a class schedule. So they are supposed to meet me in class on this particular day, but I don't know where they are. (56:23)

LE: My daughter was the same. Yeah, this is like, she's young 2006. I mean, I had to almost trick her into getting her student ID so I can find out her grade. They didn't send the grades home.

DD: That's right and I had to make that same kind of decision with my kids. I said well if I'm going to pay the bill, even though the grade may come to you, you will need to send me a copy of that or I won't continue to pay the bill. Because the colleges say we can't send it to you as a parent, it will be sent to the kids. But I say to the kids, you are going to send that right on to me.

LE: That's right.

DD: Okay, another question here. And you've touched on this to some extent. How aware - were you aware of any other developments related to the desegregation of white colleges and universities before you entered ECU? And I don't know how much activity had taken place before because '62 was the big period with Meredith and Ole Miss and I think the University of Georgia was '63 and and all this stuff started to happen really after '62. There may have been a few isolated cases in '61, but I think it's '62 was the period. (57:58)

LE: No, I was not aware. And I think that is the reason because nothing was happening prior to that, and I think that's probably why Dr. Best and my father got all involved with someone coming to East Carolina and my dad, he was so adamant. He just could not afford it. I mean, he wanted all of his kids to go to college and he could not afford him for three or four kids in college and you know, those private, historically black schools were very expensive. So he needed some financial relief. He needed a bailout. Okay. So he tells me and for years that that's why he needed me to accept that challenge.

DD: Did you receive any financial support while you were a student?

LE: No, no, no. Take it back. I did participate in the college bound scholarship contest sponsored by the Delta Sigma Thetas. That's why I wear the pen proudly today. That gave me I think, $200 or $300. I think it was $200. And that was sponsored by, now my sorority, the Delta Sigma Thetas. And that's the only financial assistance I can remember getting. Other than the... (59:26)

DD: That was external, is that correct? Because there wasn't a chapter on campus?

LE: Oh no, not on campus. It was... Matter of fact, it was one of my favorite high school teacher's sorority, and she sponsored me in that.

DD: And so you didn't get any financial support from East Carolina University?

LE: No.

DD: Okay. And again, you've touched on some aspects of this question.

LE: Okay.

DD: I'm going to ask you anyway. Was there ever a time while attending ECU you gave serious thought to the idea of leaving, or possibly transferring to another school? (1:00:15)

LE: There was a time I gave it some serious thought to myself, but I never expressed it to my parents or to any other authoritative figure. I, like I say, my sister and I had this private session, but we knew that it was just talk. I was going back.

DD: And did your sisters and brothers and your peers from high school, think that you had fallen off the deep end, when you accepted the arrangement or the decision that your parents made for you to attend ECU - this historically white school where there were no black faculty folk, no black students. When you talk to them did they say "why did you do that"? What did they.?

LE: Like I say, my sisters and brothers didn't have anything to say. I mean, that was something my parents said was going to happen. They accepted it, you live there, but since going there, they've all been so very proud of me for sticking it out. But at the time, there were no influences from my sisters or brothers to pay, I wouldn't go there if I were you, they knew that was kind of talk was not going to be tolerated in our house. And as far as my peers, I, we sort of dispersed. You know, most people from this area of North Carolina either left the area went north, in that time, you know, went to Chicago, Washington DC, so I lost contact with a lot of my peers. So you know, they just they just left and and of course, when they came back and heard that I was there, they were very proud and encouraging, you know, so, but shaking their head to like, how do you do it? I just don't understand. You know, and especially the ones who went off to historically black college, they were having the time of their lives, you know, and they knew I wasn't. That was like them, in some ways, you know? (1:02:22)

DD: You refer to your freshman class, a number of times - graduating class, what was the size of your.?

LE: Very small. There were like 26 students, I believe in my graduating class.

DD: And you were.?

LE: 1962.

DD: You were the valedictorian,

LE: Right

DD: And voted most likely to succeed.

LE: And best all around.

DD: Best all around. Immediately after graduation in 1966

LE: Yes.

DD: What contact or interaction did you have with your fellow students and former professors at ECU?

LE: None.

DD: None? Did you obtain assistance in locating a job from any former professors or have any contact with folk in the ECU career placement office? (1:03:27)

LE: Yes, I did get my first referral from the placement office. And that was and that was an interesting referral. As I said, I completed my requirements, the first quarter of 1966. I started teaching the next week. And they were very instrumental in getting that job because they knew of an all black school that had just dismissed the teacher and they needed someone to complete the school here. And that was in Bertie County, Windsor, North Carolina. And it was interesting. I went there, that portion of the school year, I signed a contract and I come back to this school. But I had built up a good reputation because the students loved me, the faculty thought I was sensational, and the principal was just like, with manna from heaven, you know, they were just all excited, and I was an exciting person, you know, and I loved teaching and I wanted to do that I taught children in churches and places like that, and that was my calling. However, at the beginning of the next school year, I was called into the superintendent's office. He decided he was going to transfer me to the all white school in Bertie County. You know, he said, I've had all these rave reviews and you're a graduate of East Carolina College and I think this is where you should be. And I think that's when I finally stood up for myself, I told him I signed the contract for Southwest all black school, that's where I'm going. If you don't want to send me there, I am leaving Bertie county. And I went back to the Southwest High School. So that was when I felt my proudest moment. I stood up and East Carolina probably taught me that because they had been on me so much and just held me back. I thought from exerting my true self. It just came out with the superintendent of county schools. So I was ready. I say, okay, I'm on my way now. No more, never again is someone going to tell me, I can't do this or you stay back or move over; You less than. Just because I am a black person I and that's - that was a turning moment in my life, and that's why I'm sharing it with you. I just decided. No, I don't want to do that. That's not what I signed up for. You are changing the game plan. I'm out of here if I'm not going back to that school. And I went back to the school, but I decided, you know, I'm not going to fight, I'm tired of fighting, I'm moving on. So I transferred out of the school system and went to the federal government. So that's that story. (1:06:35)

DD: So that was one example of the interaction that you had with the placement office.

LE: Yes, that -

DD: Would you have any reason to contact the placement office again for any system? So any other professors, for reference letters?

LE: No, I don't even remember reference letters and you know what's - and another thing about that placement office. As I said, I went back the first quarter of 1966-67 school year to do my student teaching. Of all the schools in this area, I was assigned to an all-white high school in Havelock, North Carolina. I mean, that meant I have to have a car because I had to come back to campus to take methods classes at night. And I said, well they assigned me to an all-white high school for my student teaching, but I got a job at an all-black high school, so I couldn't figure that one out. But maybe it was bigger than me at that time so. (1:07:34)

DD: Did you have a good experience in student teaching?

LE: Oh yeah, that was the best. As I said, I was becoming myself. That year, I think it was my time, it was my turn to assert who I really was because I made the Dean's list that semester - that quarter. And I had not been doing real good in all of my classes now, to be frank with you. But I knew I could do it. I just had so much pressure, I thought of fear and intimidation, you know, and I, you know, so but that's over too.

DD: Yeah, you survived that. So you suggested earlier that before you left for ECU there were a few other African American students there.

LE: Yes.

DD: And you said I think you got to know maybe a couple or a few. (1:08:30)

LE: Yeah, I got to know about. Well, the first - the second year, there were, we had one freshman - two freshmen: Bennie Teel, I don't know if he's.

DD: I know Bennie.

LE: And a girl from Williamston, Bernice Williams. And I think that that's the same year, Ray Rogers came and a girl transferred in from "Edward Waters School" [Edward Waters College] in Florida. Geneva, I can't remember her name, but she was from Washington, DC. All of them though left before they graduated, but I understand Ray came back and graduated. But they were here for about two years or I believe two years. And one of them became my roommate because she came. But before she came, I did not have a roommate. They didn't assign a roommate to me. (1:09:35)

DD: And what was this person, your roommate?

LE: Bernice Williams.

DD: Okay, Bernice Williams.

LE: From Williamston. And then when she left I was there without a roommate again. So I never had a white roommate.

DD: Okay, have you had any contact with your roommate Bernice Williams since leaving?

LE: I think maybe one, one or two times, but that was five or ten years after we, after I graduated. I mean, I don't know what happened, you know what she did after she left or anything.

DD: Okay, okay.

LE: And I've had limited contact with Ray Rogers, you know, since I am from this area. I come back here and occasionally I see him, yeah. (1:10:25)

DD: Okay, okay. Yeah. I'm getting close. You have touched on this in some limited way. But I just want to farm it out by asking this question were any blacks on campus other than students or blacks in the larger Greenville community, who made an effort to befriend Laura Marie Leary during her student days of ECU? And you have spoken eloquently about the custodial staff, and about your pastor in the community and other folk in the larger community providing some of the nurturing and support that you needed to get through this hectic period. Is there anything else you care to say?

LE: Yeah, I just want to really emphasize my Aunt and Uncle, Uncle Aaron Leary, and my Aunt Martha Leary were just a [unclear at 1:11:25]. They were just always always supportive of me, and provided me with so much love and attention. I just, I just shall never forget them for that too. And they're, their children are like - they have two daughters and they're like my sisters until this day, you know, we just bonded because of that nurturing that was given during the time that really needed them so and they live within the city of Greenville. (1:12:05)

DD: Excellent. And that's one of the things folks are encouraged to think about. Once you get to a city or town wherever this college is located and you chose to attend, if you need to think about finding some source of support, to nurture you and that source of support is not always on the campus. It may be a local church and maybe some persons out in that community, but in order for you to be successful, you need to find that support. And I know, I went to undergraduate school at HBCU historically black school, but we still need to find those kind of support systems, the church so you don't say goodbye, gone off to college. I don't need you anymore. You know, you needed to find somebody who could be a surrogate mother, surrogate aunt, or surrogate grandmother for that support system.

LE: And I also affiliate myself with the Sycamore Hill Baptist Church here in the city too. And years later when I got married, I met I came back and got married there too. So I did try to keep. And I, and I told my daughter - my children did the same thing when they went off to school. And it's just so funny how they thought, why should I do that? I said you just need somebody every now and again, I don't care who it is - just remind you, you are somebody you are a person. You are a human being. You need some nurturing. (1:13:43)

DD: Okay, we are nearing the end now. And you touched on almost all the questions I anticipated asking. But this is what I'm going through again and you've touched on this again, at the time of your enrollment, how did you see your role as the first African American to enroll as a full time student at ECU? Did you see it as simply that of a student or as some kind of historic development that would possibly have great significance for both black and white Americans?

LE: As I said earlier, it was not my decision. And to be perfectly honest, it was just being a dutiful obedient daughter to fulfill the wishes of my parents who I felt wanted to make an impact on black and white America.

DD: So they were at that stage.

LE: Not me, that's exactly right. (1:14:53)

[Unknown]: You mentioned your parents several times, could you tell us their names?

LE: Okay, I think I did. My parents were Richard W. Leary and Mammie E. Leary. My heros.

DD: Did either of them attend college?

LE: Neither of them attended college. Neither of them graduated high school. My mother continued trying to get her GED from Pitt Community College. But my father got seriously ill and so she abandoned that idea but they're both the salt of the earth, good folk who did not have the privilege of getting in there with an education, but saw to it that that children did.

DD: The next to the last question, this if you would, please discuss briefly the relationship that you've had with ECU since you graduated in 1966 and when did you begin this relationship? Did you come back to campus immediately after 1966 or was it a 10 year lapse, 20 year lapse, or 40 year lapse? Or what? (1:16:17)

LE: It was almost a 40 year lapse. At the first time I can remember coming back to East Carolina was for an invitation that was extended to me by the Ledonia Wright Cultural Center's "First African American, First Affair" and I was, had to be talked into that. And I don't know if you know, Nell Lewis, she could talk to you into anything.

DD: That is correct.

LE: So she talked me into coming back and that was in 2002. And if I recall correctly, that was the first time I had been back to East Carolina since graduating.

DD: 2002. Had anyone contacted you during this period? (1:17:10)

LE: Yes, I had two or three contacts from - not from East Carolina, but from the Daily Reflector, during their black history month they wanted to do an interview. I think that may have happened twice. They called me I didn't come down. They didn't invite me to come in. But they called me and did an interview on the telephone. And since 2002, though I have been most affected by the interest that some of the new - some of the young students here and some of the young staff members have taken in me and I am just so grateful. I tell them all the time. I am creating new memories for East Carolina. I am really grateful to them and one such person was Catherine Adams, of course you met her. And Jason, I can't remember.

DD: West.

LE: Jason West, who was the first person to really make me feel that I had done something and he was proud of it. And he wanted other people to know about it. I will be grateful to him. And also Tony Capiano? (1:18:29)

DD: Yes.

LE: I think he's left.

DD: Right.

LE: And it was another young girl, Moni- I can't remember her last name either. But they came to DC to meet me and, and we had a wonderful time and I told them how grateful I am that they saw fit to show me that they appreciated my efforts. And also Dr. Nathan Turner, who's been very gracious then appreciate all of them. I really do. I just appreciate them helping me create new memories and I appreciate you for having this interview with me this morning too. I feel real comfortable. I tell everybody you know when I was at East Carolina I don't remember a black professional ever having any contact with me or on campus. And now that I see that there are some here I am just so grateful and I think the other students should be appreciative of the people and I just don't know how good it is to see the face that looks like you in front of a classroom. So I thank you. (1:19:46)

DD: Certainly we are indebted to you guys every day because we stand on the shoulders of you all as pioneers. We want to do our part and that's what I'm constantly telling these students you know, that you can't take for granted, you know what's happening at ECU now, without thinking about those forerunners, you know, those Laura Marie Leary's. Even in the larger society, the Civil Rights movement, the Martin Luther Kings, and all of these other folk, the Rosa Parks. One last question regarding contacts here. You don't recall getting a call or letter from Dr. Mary Jo Bratton when she was putting together this book? This book came out in 1986.

LE: No because the only real recollection I have of me having any contact with East Carolina was after I relocated from Atlanta and I came back from Atlanta in 18- 1986. So, I don't remember anyone calling me in Atlanta from East Carolina. I know there are a lot of articles and stuff I've gone online and I don't know where they're getting the information from. Evidently they are getting it from this book. So as I say, I've never seen the book I did not know it existed. (1:21:12)

DD: Okay. Then and now, in my last question, how do you regard the decision that you made 42 years ago? If you could roll back the hands time, would you make the same decision again? Then and now.

LE: I think if I could roll back the hands of time, I would not have the choice. I would make the same decision because I wanted to honor my parents who thought it was the right thing to do. I was a young person, they were old and they knew what they wanted to see for the future. And because I was instrumental in helping them realize some of that. I would - I have no regrets.

DD: Thank you, Mrs. Elliot, for your candid remarks and for being the pioneer that you are in the 100-year history of East Carolina University. We certainly are grateful to you for returning and allowing us to interview you today. Thank you very much.

LE: And thank you so much for having me. (1:22:36)