[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

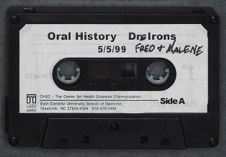

ORAL IDSTORY INTERVIEW WITH DRS. MALENE AND FRED IRONS November 19, 1998

Interviewer: Ruth Moskop

Transcribed by: Sabrina Coburn

30 Total Pages

Copyright 2000 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

RM: Today is November 19, 1998. My name is Ruth Moskop, and I'm here at 100

Hickory Street in Greenville, North Carolina to interview Dr. Malene Irons and Dr. Fred Irons. We're going to record the second in a series or oral histories with them. Dr. Fred, do I have your permission to record this interview?

FI: Indeed you do.

RM: Thank you. Dr. Malene, may we record this interview?

MI: Oh, yes. This is good.

RM: Super. I certainly do enjoy it. (Laughs) Dr. Fred, we were going to talk a little bit more about what inspired you to become a physician. Last time you said that your grandfather was a physician.

FI: That's right. And I was interested in medicine at that time, but not particularly. But when I was a freshman at Washington and Lee, the first time-1929-1 was in an automobile accident and had to be in the hospital for six weeks and the first three weeks, I don't remember anything about it because I had a severe head injury and the last three weeks I do remember, and I had decided at that time that that was it and I was going to get into premed and going to be a doctor. (1:09)

RM: The care of the nurses-you were impressed by the professional atmosphere there.

FI: Oh yes, and the doctor, too. Of course, they're dead long since.

MI: But Dr. Leach, tell her, he took you in his home after that.

FI: No, not Dr. Leach, Mr. ( ), the treasurer of Washington and Lee took me in his home to recuperate from that hospital experience and that was...

RM: Was looking out for you...

FI: That's right. Sure was.

RM: But you remember, way back, you had a respect for physicians, I think, because your grandmother told you about your granddaddy.

FI: That's right. He sure did. Absolutely.

RM: And the office. Where was that office?

FI: The office was in the front right joining the front yard. And it was just like it was when Grandfather left it. I don't remember any specific instruments that he left but Grandmother had-kept it up and the building was in good shape.

RM: That's wonderful, because it had been quite some time.

FI: Oh, yes.

RM: Almost a whole lifetime before you were old enough to visit that building.

FI: Oh, indeed. Yes, that's right. (2:14)

RM: Did it have more that one room? That little office?

FI: I can't remember. I think it was one big room.

RM: And what happened to your grandfather? I guess whenever he visited a patient, he had to go on a horse.

FI: That's right. At that time, of course, there wasn't anything else but a horse and buggy. Well, he had a horse and a buggy, and did all of his calls that way.

RM: How did he catch pneumonia?

FI: He went to see a patient that was quite ill and had to stay all night and got pneumonia himself and died.

RM: Nothing anybody could do.

FI: No.

MI: Not then. So bad.

RM: Dr. Malene, you were going to supplement a little bit of ...our last interview with some more information about your mother. (3:11)

MI: Oh, I just wanted to say,--I did say that my grandparents did everything they could do show us all the good parts of her which was a tribute to her, but that I didn't think she could do any wrong until I was thirteen or fourteen. I was so shocked that she had done things that they didn't approve of, but it was not anything serious. It was the fact that she was the child in the family-and there were five children, three boys and two girls-she was the child who was always so glad to see them and brought them things and cooked and fixed for them. Her younger sister loved the piano and went to the Julliard School of Music and didn't do any music. The oldest brother, Costen, was the one that was a Methodist preacher and went into a career with that. Uncle Isaac was the one that went and got a PhD in History. He went to Trinity College and got his undergraduate work, and got his PhD in Pennsylvania and everybody in town was so excited to see a PhD. They didn't know it was just a piece of paper. (4:24)

RM: (Laughs) That piece of paper means something.

MI: And Uncle TC- both Uncle Isaac and Uncle TC were in the first World War. I have their letters which I hope to eventually edit. Uncle TC was offered a scholarship at Oxford University and was in England for two years after the war. And he was treasurer of Greensboro College when he died. Uncle Isaac died from--, they said, it was flu that he had during the World War, but I think it must have been rheumatic fever because he had heart and kidney problems. But he was just 33. He had no children. Married. But those uncles spoiled Isa and me. They were there in the home when we were growing up and they called us their "precious hearts" and they played with us all the time which was very enjoyable for us. We had a very happy home life. Some people would call it fundamentalist Christian because they were so strict, but they were doing what the community did, so it wasn't anything. (5:35)

RM: They fit right in.

MI: They just fit right in, and they loved to work and do things in the church and in the area. And my grandfather died when we were thirteen-and-a-half and my grandmother died when we were fourteen. And they were very helpful to us. Then we went to live with our father and mother. She was our stepmother, but we had thought of her as our angel mother. She was so good to us, and she sewed for us; she was a beautiful seamstress. We enjoyed her and we went to- our father's pastorate in Wilson, and New Bern, and Rocky Mount and other places in the east. We had a little sister who was named Ruby and we spoiled her dreadfully, but we loved her. She was a cute thing. But our father could not afford to send us to Trinity College because then it was so expensive and he searched the things and talked to people and selected East Carolina because he said that was the most inexpensive good education that he could get. So he sent us to East Carolina. He had us stay out of school a year to take typing and shorthand so we could have a job while we were in school. We did do the typing and enjoyed it very much. We made poetry books over here. I threw one away the other day. (7:06)

RM: What kind of books?

MI: Children's poetry. All the people that graduated from Greenville had to have Miss Coates. Miss Coates required this poetry book, and it was about 100-150 poems that were fun and we typed them out on the pages for them.

RM: Each student had to produce a book of poetry?

MI: That was each education student. That was- I don't know whether that was primary education or intermediate education, but every student had to have these poetry books.

RM: Had to have her own poetry book?

MI: Yes, and she made it.

RM: Her own poems. And you typed them up?

MI: We typed...

RM: Isn't that fascinating!

MI: And we made all of our expenses because it just wasn't that- it was $90 a semester when we went over here to school. You couldn't have that today. But we loved school. We did have teachers of dignity-we had good teachers. The one course they required us do over; like they required physics to be done over, organic chemistry to be done over. (8:23)

RM: When you went to Duke.

MI: When we went to Duke.

RM: That's what you did over.

MI: Yeah. But they required it because that was a different focus of the thing. Our English was as good as any school.

RM: I understand. Well, where did you live when you were at East Carolina?

MI: In the dormitory.

RM: They had dorms. So the $90 included the dorm?

MI: Uh-huh.

RM: Woo! And the meals, too?

MI: Yeah! I just couldn't get over it. I just couldn't get over it.

RM: That's wonderful.

MI: And meals were helpful! But we had a lot of good friends over there and we were happy. When people would ask us in class where we were going to be or what we were going to be, we'd say, "Doctors." And they'd say, "Pshaw!" Didn't believe we could possibly. They thought we were foolish. But we loved the work at East Carolina; we were glad when we graduated. We enjoyed Duke so much because we were so busy. We were serving in the dining room and working for the professors and we had two or three professors that had taught our mother and father. See, that was 1935 and our parents had graduated in 1909, so it had been a good time back. (9:39)

RM: From Duke University?

FI: Trinity College.

RM: Oh, Trinity College.

MI: Trinity College became Duke in the early '30's.

RM: I see. I see. Well, clearly you and Dr. Fred both have always loved learning and been very avid students.

MI: Well, we wanted to.

RM: Oh yes, I understand you motivation, because it's a thrill. Learning is a thrill. You mentioned that you spent some time with your uncle. Was it Uncle Costen in Atlanta?

MI: No, that was- we were there a lot, the last years of his life. But it was an aunt and uncle in Hertford, North Carolina. We spent a whole year and our grandmother moved there with us after our grandfather died. Then, they moved to ( ).

FI: It was your mother's sister and her husband. That's who it was.

MI: The Julliard music lady. (10:27)

RM: I see. Alright. I see. Tell me some more about your uncle who became a bishop.

MI: Well, he was quite an interesting man. He was a man who-well, when he went down to Cuba and presided at the Cuban conferences of Methodism, he didn't know Spanish. So, that winter, he got him a book and he presided at the conference in Spanish. He was one of these people that just wasn't going to be put down.

RM: Picked it right up.

MI: He was going to Florida one time to preach one Sunday in Miami and the train stopped and they said they could not go any further. And it was two hours before his sermon and he was 60 miles from Miami and he went out on the roadside and put out his thumb and went. He was an interesting, daring person. He was - he wrote right many books. They're really devotional books, but the they interest us and we are very interested that Charles, that's our, that's Fred's oldest child, grandchild (Fred is the youngest boy). Charles uses these. He's leading a youth group in the Episcopal church but he's using Methodist books, but he doesn't know the difference, if there is any. He wrote thirteen or fourteen books. (12:09)

RM: And his name again was...

MI: Costen.

RM: Costen Grant.

MI: No. Costen Harrell.

RM: Costen Harrell. That's right because he was your mother's brother.

MI: Yeah. And the other interesting thing: Fred married a girl named Susan Harrell.

RM: Oh my goodness.

MI: And she comes...It's the fifth cousin. We traced it back and found it.

RM: I'm glad you figured that out. (Fred laughs)

MI: Yeah, we just couldn't stand not to know. We didn't know that we were any kin, but it seems the Harrells are most prolific. They have a lot of you open a phone book in Hertford, and in Edenton and in Elizabeth City you'll see a lot of Harrells.

RM: Well, that bodes welL You'll very likely see some great grandchildren here.

Ml: Yeah. (Laughs) But the Harrell family has had some very interesting experiences and things happen. They came with the Jordans who and the who are the others that came from - the Feltons and the Ewells came from a certain section in Kent County, England and they all came together and settled there. And they're so intermarried that you don't know who's who. (13:29)

FI: (Laughs)

MI: But it's alright because they...

RM: They get along just fine.

MI: They do.

RM: You mentioned that your Uncle Harrell knew a lot of interesting people.

MI: Well, he knew the bishops that were retired there in Atlanta, you see. Bishop Smith and ( ) they would visit the man that was the head of Emory. He taught at Emory in his retirement years. The last eight years of his life, he taught homiletics, which is preaching, if you don't know what it means. I don't.

RM: Thank you for clarifying that.

MI: But he was a thoughtful person in his speeches.

RM: Did you tell me that was his book? The Margaret Sangster book that we have. Was it his book?

MI: It was his book, but I just didn't see any need to keep on keeping it. (14:25)

RM: We appreciate having it. It's historically an important book.

MI: I know it is. And I knew that.

RM: And he appreciated her work. He was a contemporary or not...

MI: That's right.

RM: ...of Margaret Sangster.

MI: He was born in '81. My mother was born in '87 of that family.

RM: Well, shall we move on and talk a little bit, get back to medical school here. We had Fred and Malene in medical school. Fred was the expert in anatomy lab who helped keep Malene neat.

MI: (Laughs)

RM: And we had you married and living in a great big room there in Richmond. Ml: And that's where we had the turkey.

RM: And that's where you had the turkey. Were there any other special experiences from the last years of medical school that you remember?

MI: Well, you see we were out at the home for Incurables. That sounds awful to everybody. (15:27)

RM: Who was at the home for Incurables?

MI: We were. We lived there. That was our home for that whole year.

RM: You moved from your antebellum mansion to the home for the Incurables.

MI: That's right.

FI: That's exactly right.

MI: We were happy there. We ate our meals there.

FI: We had our room and board. They paid us our room and board.

MI: Had our room. And we rode the streetcar...

RM: Why did they...this was a special opportunity for medical students? At the home for Incurables?

MI: Well, they thought that that would be a way they could solve the doctor not having to come every day. And there were eighty-some patients there. They were real sweet. They paired off, they were not husband and wife, but the men and women paired off ...

RM: To keep each other company.

MI: Yeah!

FI: They legitimately paired off, yes, uh-huh. Nothing wrong with it...

RM: I understand. (Laughs) They enjoyed each other's company. What does that mean, "Incurables?" (16:35)

MI: (Laughs)

FI: The people that were there were in the end state of disorder, whatever it was.

MI: Chronic disease. We learned a lot about chronic disease there. I didn't use it as much as he did.

RM: Dr. Fred went into General Medicine so it served him well to have seen that. I'll bet it did. And there were eighty patients. And that's where you lived. I guess you had your special quarters?

MI: Oh yeah, we had two rooms. And a bath which was very nice compared to what we'd had before.

RM: But Isa was not there or was she?

MI: No. Now she wasn't there, but we would meet here at medical school every day. We got on the bus every day and went to medical school. She was very happy that year, though. A mutual friend of ours, a horse lady, got Isa interested in horses, and they were together quite a bit. Elizabeth Martin, Fred. Everybody thought we would be destroyed when we separated, and instead, we helped each other. But, through the years, we were very close together. We talked to each other every day. Between 6:30 and 7:00, and we made decisions about things we did together. She was in Health and that was because she had experience at the Sanitorium, but she looked at everything from getting them well, what you can do to make them well. And that helped us a lot. It's like this new style in medicine, but we don't think that's very good because so many people are putting so much emphasis on the wellness that they don't see the disease. The disease had got to be treated, too. But she was Health Officer n Pasquotank, Perquimmins, Dare, and Camden counties in this state and went on to the State Board of Health in the chronic disease section, and she was in charge of the (pauses) can't say the word... (19:04)

FI: Rural health? Was it rural health?

MI: She had the rural health, but she also had in chronic disease the problems of putting in new organs and kept such lists.

RM: Transplants. Donors...

MI: She would be so thrilled now. She kept the list and made the decisions, was the head of the...

RM: Donor lists.

MI: For donor list. But, now that's not the problem it was. It's still not easy but it's much, much better that it was. Now they have many more organs to use. But she...

RM: You're way ahead now, you've got us way past medical school.

MI: Well, she's there and she, and she was a real big help in the state. And did a lot of things first that any woman hadn't done. And she was the Assistant State Health Director and when she had this ovarian tumor, she was the highest woman on the state roster, but they got, the next year, the woman she recommended (Sarah, Fred) for head of all health problems. (20:26)

RM: In North Carolina. Wasn't she the medical examiner? Wasn't she?

MI: She was a medical examiner, oh yes. She was a medical examiner and she worked with Dr.... What's his name, Fred? The one that moved here and knows...

FI: Rose Hardy.

MI: Yeah, what's his name?

FI: He's retired, but he's still working.

MI: Yeah. He's working in Europe now. Anyhow, he was the one at Chapel Hill and what he did, said, "Isa, I'll do it for you, but I'll tell you about it and we'll work together." And she didn't really do many medical examinations, because he was the one who had the pathology training. She hadn't had pathology training.

RM: She was the administrator...

MI: Yeah.

RM: ...pretty much ands he helped out. Well, that's good. That worked out well. Well, how did it go when you two graduated from medical school? Did you celebrate?

FI: Yes, we did. Our families came to...

MI: Both of our families came. (21:32)

FI: We were very, very elated and then we immediately started working in the hospital. I was in a rotating internship and you were too, weren't you?

MI: Yeah.

RM: Which hospital?

MI: Our first year, I was rotating.

FI: At Memorial Hospital. ..

MI: The hospital in Richmond.

PI: Yeah. Richmond Memorial-- What was the name of that hospital? Memoria1?

MI: Yes, that's Memorial.

RM: Memorial Hospital in Richmond.

PI: That's right. Right at the medical school.

MI: And we worked together. They put a double bed in our room so we could be there together, and Fred took the night, the Emergency Room, you didn't take the night work for me then, but you took the Emergency Room work because he didn't think I belonged in there. One July the Fourth, he did 75 stitches in different people that kept coming in getting stitches. (22:39)

RM: My goodness. Now, why did you think she didn't belong in the Emergency Room?

PI: Well, now we didn't have any children at that time, honey. I think you did your own ...

MI: I know you did that July.

PI: I did?

MI: But I might, that might be in error for all the time.

RM: You were in a rotating internship so each of you rotated through departments.

MI: Yeah, you took Medicine, then you took Surgery, then you took Pediatrics.

RM: I don't want you doing all that work for her here, Dr. Fred!

PI: No, I covered the Emergency Room at the hospital here in Greenville when our children were little, because I wanted her to be home with the children.

MI: He said the truth was he didn't want to get up with them.

RM: I understand. (Laughs) The patients were quieter than the kids, in other words.

MI: Yeah.

RM: Well, after your first year of rotating internship there at Memorial Hospital, what did you do? (23:46)

PI: Uncle Sam did me. I went overseas.

RM: Which year?

MI: After the first year?

FI: After the first year.

RM: Scooped you right up.

FI: That's right. I graduated in '41...No...

MI: You graduated in '41, went to...

FI: Camp Pickett.

MI: ...Carlisle Barracks in '42 and from Carlisle Barracks to Camp Pickett.

FI: That's right and then went overseas in '43.

MI: To Fort Devens.

RM: And what was the...

MI: No, you went to Fort Jackson before you went to Fort Devens.

FI: Yeah. We were together at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina.

RM: Oh, Malene went, too?

MI: Yeah. I went to Fort Jackson. I worked with a dear lady who was a gynecologist; a nice lady and I enjoyed it and I learned how to do several important things I had never known how to do because I wasn't doing the gynecology. (24:37)

RM: Did you...well, I guess that's different than from the OB. You were just learning gynecology.

MI: Mostly, but she did OB, too. She was a real smart lady. She had a lot of patients living in South Carolina. Her name was...

FI: Guignard.

MI: Jane Guignard. And there were three of those girls. One of them was a famous artist. She didn't live with them, though. She lived by herself. And she was raising Chihuahuas and she had twenty-some. And you know, Chihuahuas are one-man dogs. Two of them liked me so I had two of them in my room with me. I had to move them sometimes for a patient to sit down. But I enjoyed here because she was so much fun. And she had a lady that worked for her. And she had...

FI: Von Recklinghausen's disease.

Nil: That's right. That's what it was. Von Recklinghausen's disease. That means you have moles--lots of them-all on your face and arms and hands. But she liked to take care of the dogs so that was good. (25:53)

RM: That kept her employed, it sounds like.

MI: That's right. It really did. The dogs loved her. Several of them particularly.

RM: So, this was in South Carolina.

FI: I was in South Carolina.

MI: In '42.

RM: Columbia, South Carolina in '42 and then Dr. Fred went overseas from there.

MI: Well, he went to Fort Devens and that was the bouncing off place. Fort Devens, we were several months. That's close to Leominster, Massachusetts. And close to Boston, right there at Boston. We had a place at Leominster where the family moved out to rent their home because the rent was so good. You know, they do that, too. But we enjoyed it in that house. It was fall. It was the first fall I had ever seen in New England and it was gorgeous.

RM: Oh, I know it must have been.

MI: I went to walk everyday just to look at the maples.

RM: Were you able to practice any medicine up there? (26:52)

MI: No. But we weren't there but a few months. Two or three, I think. Well, I can tell you how long we were there. Two months, because we went to New York in July and then you left in October-went to Devens in the last of August or the first of September.

RM: That must have been difficult for you.

MI: Very. And you know it was-you know, if they had been going just on a trip, which I tried to tell myself, well, maybe they were on a trip, it would have been better. But we knew they were going in danger.

RM: Sure.

MI: And that's one thing you ought to talk about, Fred.

RM: Tell us.

MI: The doctors were not in as much danger as the others.

RM: How ...you were part of the Medical Corps? How ...tell me the words for that. I don't know the words. How did they describe what you were when you went overseas? (28:00)

FI: General duty medical officer in the Reserve Corps. Army Reserves. Corps Army Reserve Corps.

RM: Medical Corps Army Reserve.

FI: Course, I was in the Reserves in medical school, so I knew I was going because I didn't have any choice. And so, I expected to go.

RM: So, they sent you over, and where did you land?

MI: Liverpool.

FI: We landed in Liverpool and stayed awhile there with the 56th General Hospital.

MI: He went with the 56th General Hospital.

RM: I see.

MI: Which was the Medical College unit?

FI: It was not the Medical College unit.

MI: It wasn't?

FI: No. The 45th was the Medical College unit. The 56th was...we had people from Hopkins and Cornell.

RM: All mixed up.

MI: I didn't know.

RM: And your duties there were to take care of American soldiers? Or any Allied soldiers? (29:06)

FI: That's right.

RM: Any Allied soldiers. Did you work with physicians from other countries when you got over there?

FI: Oh, yeah.

MI: And even had German patients.

FI: During the war, yes. Sure did. We were stationed at Liege, Belgium during the ...when the fighting was going on, and one Sunday, I was taking care of prisoners and we heard the buzz bomb coming so all of us got under the table. That's what everybody did and nobody at that time was hit. But during our stay there, one of our...

MI: In Liege.

FI: In Liege, one of the assistant...in the medical detachment, I was a Captain and the assistant was a Lieutenant...he was, well anyway, he was going on to a tank that had been struck by the Germans to get a man out. Of course, he got a Silver Star, which I recommended him for, of course, for doing that. We had some very interesting experiences. (30:30)

MI: Tell him about the experiences when you went toward Elbe.

FI: We were going to meet the Russians at the Elbe River. I was in the ambulance and the driver said, "Get out, Doc! Get out, Doc!" Well, I didn't know, it was just at dusk and so he heard the plane come over and we were all over there and hit the ditch.

RM: What did he say, "Get out, Doc?"

FI: Yeah. That's what he said. "Get out, get out, Doc!" He got out on his side and I got out on mine and left the door open and the projectile came down and went right through the glass-the door was open-and through the seat where...in which I had been sitting.

RM: Where you were sitting? Oh!

FI: That's the closest I ever came to the Great Beyond. (Laughs)

MI: Don't care to get any closer. (Laughs)

RM: So, I guess you took care of all sorts of wounded people.

FI: Oh, yes. Yes, we did.

MI: See, he was a surgeon ...

FI: Battalion Surgeon. (31:29)

MI: Battalion Surgeon and took care of all the medical needs...

FI: ...that we could take care of and moved them on out to places that were too much for us. I remember one case; one of our soldiers came, one of the Allied soldiers, came with his arm shot off and so, we just bandaged him up and put him in an ambulance and sent him to the field hospital and he did recover, I found out afterwards.

MI: But that's bad. Just shot his arm off.

FI: Yeah, uh-huh.

MI: That must have been a sniper.

FI: Well, it probably was The Executive Officer in the...well, that was when I was with the Fifth Army Division, though ... the Executive Officer was walking along and saw a sniper up in a tree and raised up his arm...he had a gun, of course, he could carry one...and the sniper killed him, shot him instantly. (32:35)

RM: Oh!

FI: He was from Roanoke, Virginia.

RM: Right there beside you.

FI: Yeah.

MI: He was from where?

FI: Roanoke, Virginia.

MI: Oh, my gracious.

FI: So, we had some...

RM: What did you do after that? After you saw somebody fall right beside you?

FI: Well, no, I wasn't right there where he was, no. I was in the same outfit as him.

RM: You were...you were the first, it sounds like...do I understand correctly, that you were the first line of medical care?

FI: That's right.

MI: That was. That foreign, that group...

RM: How did you feel about the equipment you had?

FI: Well, we had a minimum of equipment and most of it was putting on tourniquets for bleeding and bandages to stop bleeding and, of course, those that were hit like that had to be transferred to another area. But, we did the best we could with what we had. (33:46)

RM: Sure. You had to administer medication, too.

FI: Oh, yeah.

MI: Well, you did that, didn't you?

FI: Yeah. That's right.

MI: Because of pain.

RM: Whatever you had...

FI: That's right.

RM: And how many people worked together in the medical care there in your group?

FI: I can't remember the exact number in the medical detachment, but we had a Staff Sergeant and lesser people and Privates all the way down the line, but they had been in camp before they came, so they were well trained.

MI: They helped you.

FI: Yes, tremendously.

RM: Were you the only actual physician there in charge of the unit?

FI: Well, yes I was...of the medical detachment. I was the Captain in charge of the medical detachment. (34:42)

RM: That's a lot of responsibility.

FI: Yeah.

RM: So, you were in two different. ..you were in Belgium and then you were over at the Elbe, then.

FI: That's right.

MI: Then, he came back.

FI: While I was in Belgium I was, of course, I landed in Liege, Belgium with the 56th General Hospital and then a little later on, I got transferred to the Fifth Armored Division. I was with the Fifth Armored Division at that time when we went up to the Elbe River.

MI: But, there they saw the Russians. And they were just dancing, he said.

RM: You saw Russians?

MI: At the Elbe, you see, the Americans and the Russians met at the Elbe. And we've met several of people that were there, too. I don't know...how many thousands were there?

RM: Did the Americans celebrate, too?

FI: Oh, yeah.

RM: Well, what were you doing at home, Dr. Malene? (35:44)

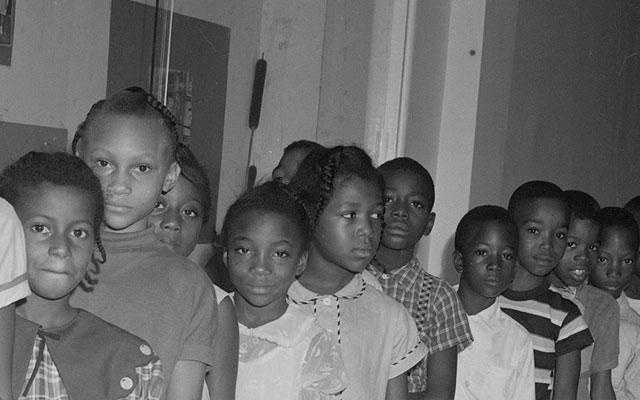

MI: I was...Isa and I were taking care of the children in Richmond. We had a job. You see, we had the whole...there were 56 beds in Medical College Hospital and there were forty-some in ...not Duley...Saint Phillips. That was the black hospital; they were separate then. But it was in that hospital there and had less people but had mighty good nurses. So, we made rounds in each of the three hospitals every day. Did all the treatments, then made the rounds again at night. And we did not have emergency rooms in those hospitals for pediatrics, but when they came in the emergency room in Medical College, they would call us. So, one of us always had to be on call for when ...

RM: When the children came. (36:50)

MI: ...when the children came. We had a little boy brought in with purple spots on him. That doesn't mean a thing to you, but it's meningococcal septicemia or some septicemia...purple spots...and we knew that meant immediate treatment. You only have a few hours to treat them. I took him upstairs to treat him and Isa called me up there and said, "His mother's here and she's got them, too." And it's never carried. You know ... you know you never have a mother and son. It was just an unusual thing. But, they got well. Sulfa is specific for that. Even more specific that some other antibiotics. And it was such a joy when that little boy went home.

RM: When did antibiotics come into use?

MI: Well, penicillin was not used much in Richmond in 1940 and '41. They had it once in awhile. When we came to Greenville, they hadn't...they had hardly any. People had sent for it. I don't know who used the first year, but we very soon used it. Did you use the first? (38:00)

FI: No. I...we didn't come back here until 1945.

MI: I know it. But it wasn't used much here. There were a lot of things we needed here, but we had good doctors and good, patient doctors and that gave us a lot of respect for them.

RM: Surely.

MI: Dr. Haar was as patient as anyone I have ever known. He was a child specialist.

He didn't come until I had been over a year. But he had been here before and come back. But, Dr. Watson had been here and he had died. And so, there wasn't any pediatrician immediately, the first year I came. So, I had some that just needed a pediatrician.

RM: Well, back in Richmond, though, you used the sulfa drugs. Now, sulfa...

MI: For that. That was meningococcemia.

RM: Help me there. Are sulfa and penicillin the same thing?

FI: No, no, no.

MI: Uh-huh. They're entirely different. Penicillin helps meningococcemia but not as much as sulfa. You know, now, we've got so many antibiotics. That's an amazing thing. We just can't even believe it. And they cost so much. Fred had to take some for his foot the other day. Thirty-one dollars for a prescription! (39:20)

RM: Well, which came first, the sulfa or the penicillin?

MI: The sulfa came first. And the sulfa was a great thing for pneumonia, at first. We had several pneumonias that never would have recovered if it hadn't been for sulfa.

RM: How far ahead of the penicillin did that come? Was that available?

MI: It would be a matter of a few years. Three or four years.

FI: Approximately, I would think

MI: '37 was the first time I used sulfa. I don't...

RM: Tell me about that. Do you remember the first time you used it?

MI: Oh, yes. Every one of these things.

RM: What did you use it for?

MI: I used it for what I thought was pneumonia and it was pneumonia and what I was doing was typing the pneumococcus. The germ you could type and use type� specific antibodies. That was in Duley. The nurse came in and said that the sulfanilamide they had then. And I said, "You bring it." And I got the folders and began to read on it. I read more on drugs that I'd given them to know about them. There was always...you wonder whether, well, what contradictions there are. (40:45)

RM: Yes, what might happen.

MI: Yeah.

RM: Yeah. So, you administered sulfanilamide in a case of pneumonia when you were in ...

MI: I was interning then. I don't know whether I was...

FI: That couldn't have been '37 because '37 was our first year in medical school, honey.

MI: Well, I was still ...it must have been before I graduated because I did a lot of volunteer work on the wards treating patients.

RM: How did you have time to volunteer?

MI: Well, that's what you learned from.

RM: Uh-huh. So, you went to school and volunteered.

MI: Well, what I did now, summer vacation we were supposed to do deliveries and did have to do them, but we had a month free and I volunteered in pediatrics then.

RM: I see.

Ml: One time then, I know. (41:50)

RM: Did Dr. Fred volunteer, too?

MI: Yes, he did.

FI: Yeah, honey. We didn't have...we didn't go out on cases our freshman year.

MI: No. We didn't. I'm wrong on that time. But it was before I graduated.

RM: I understand. And what kind of patients did you see when you volunteered? Did you choose adults or go wherever they needed you?

FI: Well, when we were on our side of OB, of course, you had women patients in all sorts of surroundings. We didn't get the charts, of course, but we'd go out to see these patients and I remember one case when bed bugs were crawling up and down the chairs.

MI: I still tremble at that one.

FI: (Laughs)

RM: So, you had to go to the home.

MI: We went to the home.

FI: Delivered the baby there. (42:47)

MI: We knew the city, I'm telling you. I learned the streets.

RM: Were you two born at home? You must have been.

MI: Oh, yes. I was.

FI: I was.

RM: That was the place to be born. So, even at that time, in the late '30's in Richmond, people would still, well for whatever reason, they were having babies at home.

MI: They were having babies at home in Richmond then.

RM: Uh-hmm.

FI: That's right.

RM: So, you're volunteering in medical school and here come antibiotics.

MI: But you were volunteering to learn.

RM: Surely. I understand.

MI: And you just wanted to see another case.

RM: You were telling me about the boy and his mother who both had the purple spots.

MI: Yeah. We gave them intravenous sulfanilamide. We had it then so he improved and the mother did, too. But, she was so shocked, Isa was, she came to the emergency room and saw the mother.

RM: Uh-huh. And so you got them both treated. And that was still while, let's see, Fred was in the service...

MI: He was in the service, and probably in France. (43:50)

RM: So, you took care of these children and I understand there was one little girl, one time, who lost her mother.

MI: Yeah. That was Isa's patient and then my patient. The father was overseas. That was an awful thing.

RM: Wait just a second. Excuse me for the interruption. The Daddy was overseas, and the little girl lost her mother to meningitis, wasn't it?

MI: Yeah. It comes, you know, and is gone in six to eight hours. You're gone. That's what Hoover, Taft's wife had. That was a sudden death that was not explained and they didn't know what it was for a while. And after her death, the found the meningococcus was rare, but that's the only case I've known in an adult in Richmond. But, there was a girl ... (45:03)

FI: Not in Richmond.

MI: I mean in Richmond...in Greenville. It's just a bad thing. So bad.

RM: It comes so suddenly and you hardly have time to realize it's there.

MI: Yeah. If you don't treat it right away you lose them. Later, some weeks later, the girl who lost her mother, her folks came and got her. But she enjoyed the hospital. She had service by the individual. She had us at a beck and call. We took her things and we played with her and we carried her down the hall. We didn't isolate her and, you know, I wonder if we should have or not because she was exposed.

RM: She just needed a roof over her head so that's why you kept her there at the hospital.

MI: That was it. But, where were they going to put her?

RM: I don't know what would happen now. I guess we'd have Social Services come in, huh?

MI: Well, we asked Social Services, but they didn't know where to put her. She wouldn't let anybody touch her.

RM: Oh, goodness...

MI: Well, you know, she was miserable. But, she loved Isa so that got it. (Laughs)

RM: What was that story about you ...you traded off, though? I've seen pictures of you and your sister and I can tell you apart easily.

MI: But, we did trade off a lot of things. In fact, we worked it in the wards that she took one one day and I did the other and we thought we did better that way because if anybody missed something...either of us missed something, the other one would pick it up.

RM: Sure.

MI: Now, Isa delivered twins one time in a house that was... had just beds and curtains in the rooms and was draped beautiful1y and the women dressed beautifully and she didn't realize what it was, even 'til she got out, but she was supposed to take the twins back to the hospital, so she brought the twins back. They were little black twins and they were named Jacob and Esau. And she was so pleased to put them to bed in the nursery. And everything was going smooth and we had to go to class. She was there at nine and we went to class...got back from the nursery...at 12:30 and we couldn't find our twins and we thought they had died and we were so upset. (Laughs) And the nurse said, "Don't you know they turned black?" I didn't know that little black babies were white when they were born. Most of them; and they tum black the first 24 hours. And she didn't know that. And we were some puzzled. But, we were so proud of those twins. But, neither one of us like Esau. Stories!

RM: So, you were in an unusual setting there where you delivered those twins. Is that what you were trying to tell me?

MI: Yes, yes. And that was probably a prostitute house and I told her that as soon as she got out. And, "No, it couldn't have been!" Then, she realized that's what it was.

RM: That's just exactly what it was. My goodness. All the situations you ended up in.

MI: But, you know, that was dangerous in medical school to take that on. There were so many venereal diseases.

RM: Yeah, surely it was. So, you got through the war years there, taking care of the children in Richmond until Dr. Fred came back.

MI: And then we needed to settle somewhere.

FI: That's right. Where did we go first, honey?

MI: Well, we went just to Greenville, but we talked to the people at Concord and they wanted us and would offer us a good salary and we checked Wilson and they didn't have a pediatrician right at that time and Kinston. But tell her about our talk in Greenville.

FI: Well, we talked to Dr. Carl Pace. We knew him, and he was on the Board of Medical Examiners and said, "Well, you can go to Concord and will probably make more money, but if you come to Greenville, you will make a living when you start." Well, that sounded good to us. And he said, "Also, there are no factions." At that time, there were not. Doctors in Wilson were at each other's throats.

MI: The doctors in Kinston were. There were two sets of doctors.

FI: And so he said, "If you come here, it will be entirely different." So, we took Dr. Pace's advice and decided to come here.

MI: And I wanted to finish out all the time I needed for a pediatric specialist, because I had had that rotating internship. So, that was October. We made plans to come the first of the year; the next year. Then, Fred began to help the hospital. They were without an anesthesiologist.

FI: And I had had a course in anesthesia and oxygen therapy while I was in the service.

MI: You also had a course of dermatology and then, he took a six week's course in allergy to help them here at this clinic.

FI: I went back to Richmond for that.

RM: I see. So, when you came to Greenville, you helped with anesthesiology, is that correct, at Pitt County Hospital?

FI: That was the old hospital.

MI: Yeah. You did that for two months.

RM: Where was that old hospital?

MI: It was...

RM: I think I can tell you. Was it on Johnston?

MI: Yeah. It was on Johnston Street.

RM: Fourth ...somewhere between Third and Fourth. It must have been Fourth Street and Johnston.

MI: Yeah.

FI: Yeah. That's right.

RM: That's where you worked. Can you remember that hospital facility at all?

FI: Oh, yes. And we had at that time.. .it was not integrated, of course, and the little black folks had to be on the first floor. Isn't that right, Malene?

MI: The terrible thing about the basement... and I just had a fit. We were walking in one to two inches of water in the basement with patients in the bed.

RM: Oh!

MI: I had a new baby down there. Fred, that was Sally May's baby.

FI: Yeah.

NIT: And I just couldn't stand that. And they couldn't move her.

RM: When you came to Greenville, that would have been 1946? I'm trying to find my...

MI: No. That was '45, wasn't it?

RM: It was '45-'46, wasn't it? Just sort of over that period. So, at that time the hospital was still in the old building there.

FI: That's right.

MI: And the water was on the floor.

RM: In the basement. Okay. I can imagine that.

MI: That just horrified me, though. For a new baby to be born. I don't know where the baby was born; they may have taken it upstairs. But the baby had sickle cell disease and it was sickle cell disease in her family. So, I had to do something about that. I don't remember now whether I gave him a transfusion that week or the next week, but I knew that he had it because he was so pale. And he's now a grown man.

RM: My goodness.

MI: Right old. In fact, he's working in Baltimore in the government housing project and checks them all.

RM: Is that still the best treatment for sickle cell, transfusion? Early on, does that...

MI: Well, that was the treatment then. Just transfusion.

RM: It's usually not effective, though, isn't that a serious...

MI: Yeah. It goes away quick. It's not usually effective. It's not good treatment, but you've got to save them. I had a lot of sickle cell cases and it's such a peculiar disease. They have ankle swellings and joint pains, you know, and abdominal pains. I think that's blocked vessels in different parts of their body.

RM: Yeah.

MI: But, it's just so miserable. Oh, my little Fred. Fred was trying to be so progressive at Carolina and he took on a black family to help them. Take them to the YWC-YMCA and all that stuff. And he had four boys and he called and wanted to know if he could bring them to the river. And we said, "Oh, yes, bring them right on." I have never been so miserable in my life.

RM: What happened?

MI: They stayed three days but one of them had pains. I didn't know it was the sickle cell. I had not seen that in sickle cell. We had a time with them. I stayed up all night long on night rubbing that little boy trying to help him. And he was so miserable. But he said, "I ain't never going to the river again." And I thought, well, I'm sure it would be hard on you.

RM: How old were these children?

MI: Oh, they were eight, ten, about six, eight and ten. They weren't big. But the biggest on is the one that finally told me what he had. I saw him later. Fred didn't know. Fred got then back up there because that was the thing to do. And he said that he had sickle cell disease.

RM: Oh, goodness. Well, did you take care of white babies then upstairs at the hospital?

MI: Oh, yeah. We had wonderful places. Two of mine were born up there, Tom and Ben. Dr. Pott was my baby doctor and he was very good at it.

RM: You mean your obstetrician.

FI: That's right, yeah.

MI: That's right.

RM: And who was the pediatrician?

MI: Oh, I asked Dr. Haar to check them each. He didn't check Fred because Earl Trevathan was here and Earl and I were the first...well, I don't know if we were the first two pediatricians, but we were pediatricians that shared each other's concerns so we checked each other's patients.

RM: Oh, good.

MI: On the ward. And if he had to be out of town, then I knew what was wrong with Lucy So-and-So and I could take care of her until he got back. He would call me if he had to be out of town and if I had to be out of town (one of the boys always wanted to be out of town) I could call him and I knew that the patient was taken care of.

RM: That's wonderful. You covered for each other.

MI: Yeah. We covered for each other and we discussed them. At the desk, always, to see if we could pick up something. You know, nobody knows it all.

RM: You helped each other that way. How long were you here before he came? Before Dr. Trevathan came?

MI: Several years. Well, a long time, I reckon. Dr. Haar was ten years older than I am. Earl Trevathan was ten years younger. And he came and thought it would be wonderful for us to be together. But, I had had a bad experience with a doctor who, when he had to make a call, wouldn't bring the money to the office. He just kept the money.

RM: You weren't ready for a business partnership.

MI: Yeah, and so I told him I thought it was better for us to share and that just suited him fine. I would love to have worked with him. He would never have done that and I knew that. But, I did not think it was the right thing to start.

RM: Yeah. Not all your patients were in the hospital.

MI: No. Listen, we made house calls. Fred can tell you about that. We learned the city. It's changed a lot. Now, we get lost in the new developments.

RM: Fred, we've been talking about pediatrics, here.

FI: Yeah.

RM: Let's go back a little bit to general medicine. Did you see patients in the basement and on the first floor at the old hospital?

FI: Oh, yeah. Sure did. Right.

RM: I guess you saw everything.

FI: Oh, yeah. Sure did. Everything.

RM: Old ones, young ones, fat ones, skinny ones...

FI: That's right.

MI: We had everything. We had Rocky Mountain Spotted fever, typhus fever, in that hospital. And I tell you on thing, the doctors there just accepted us and they'd say, "Come in and see what you think he's got." And you could to on out and give your opinion.

FI: I had one that had diabetes and she was in a coma and Dr. Winston, that was soon after we came here, said, "Well, now you take care of her." I said, "I don't think I should." Dr. Armsley wasn't here at the time. He was an internist, but he was in the service and hadn't gotten back. So, I worked on this dear old lady and she lived for many years, praise God, and she'd always call me up on Thanksgiving. I think she has died.

MI: She just died; we saw it in the paper.

FI: Yeah.

MI: I mean, this year.

RM: What could you do for diabetics back then?

FI: Well, you just check the urine and give them insulin.

MI: And regulated the insulin with the urine and then regulated the diet.

FI: Yeah.

MI: Which wasn't easy to do.

FI: Well, the good Lord cured that woman, I know that. (Laughs) It didn't cure her diabetes, but she lived a long time.

RM: Helped her recover. When did insulin come into use?

FI: Oh ...

MI: Oh, the end of the 20's.

RM: Was it? So, you learned about that in school.

MI: We had studied insulin, but the new insulin is so much more helpful.

FI: Human, that's the new insulin. You don't have the...you have so much more leeway with that than you do with the old type of pork insulin.

RM: Pork insulin! Human insulin is what we have now?

FI: That's right.

RM: Well, you've seen a lot of change. I feel as if it might be a good idea to wind up our interview for today.

FI: Alright.

RM: We've been at this for little over an hour.

MI: I think that we're going to have to do four. Because we haven't covered...these things are such important things.

RM: I know. It's wonderful to hear. I think we'll just have to leave it with the diabetic lady who recovered and take up right there next time.

MI: We have been so fortunate practicing medicine. We've had some mighty bad things to come through straight. We've lost a few, but compared to what we expected, we haven't lost many.

RM: I think your patients have had the benefit of your prayers as well.

FI: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. We started out practicing with the intention of doing everything possible.

MI: We made it. But, we didn't have any extra, and we didn't know what we going to do.

RM: I understand. Thank you very much.