[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

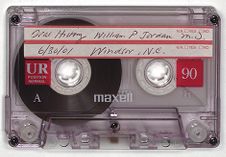

Collection Number: Date: June 30, 200 I

Narrator: William P. Jordan, MD Interviewer: David Pearsall, MD Transcriber: Janipat Worthington

Copyright 2001 by East Carolina University. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from East Carolina University.

William P. Jordan - WJ

David Pearsall - DP

DP: This is June 30, 2001. I am Dr. David Pearsall. I am interviewing Dr. William P. Jordan at his home in Windsor, North Carolina.

THE TAPE WAS INTERRUPTED HERE.

WJ: Well, I'll tell you. When I was in high school, Wake Forest College put on a field event and speech-making before trying to recruit students, you know, and they were probably all seniors, from the different high schools. And I got to go. And the preacher at the home coached me. He actually did-he carried me: on a stump, and-you miss all that stuff, you know? And I got up there, and 9/l0s ofthe students were from Charlotte, High Point, Winston-Salem, and that's when Wake Forest was at Wake Forest. And then, you sit there and talked. I stood on the stage and talked. I said, 'Look a here, this crowd don't'-the claim. I was the orator, you know, the claimer. So I ranted and carried on and all those boys, they just talked. I was clean out of it. I didn't get one thought on that one. So I feel now like I did then, even though I felt like a fool.

DP: You'll win this contest. Dr. Jordan, you were telling me you were born in the countryside near Windsor?

WJ: In where?

DP: You were born in the country near Windsor?

WJ: Well, actually, I would say it was about 18 miles from here but still in the same county now.

DP: Uh-huh. What year were you born?

WJ: I can remember-1911.

DP: Uh-huh. And that makes you how old now?

WJ: Ninety years and six months.

DP: My goodness. You look young for 90.

WJ: Ninety years old. I feel it, though. These things are giving out-getting smaller and weaker.

DP: Did you grow up on a farm?

WJ: Well, more or less. My father had a store and a farm, and part-time we lived in a little small town up that way when his farm was out.

DP: What was the name of the town?

WJ: Powellsville.

DP: Is it still there?

WJ: Powellsville's still there.

DP: My goodness. What kind of store did your father have?

WJ: Just a general store. You could buy horse collars and beef and all in between. Anything you wanted, it was a general store.

DP: Uh-huh. Did he grow up in this area as well-your father?

WJ: No. My father was born in Virginia-the Princess Anne area-and he migrated down. It got too crowded up there, and he migrated down to North Carolina.

DP: I see.

WJ: A lot of 'em left Williamsburg and the Jamestown area and came down to North Carolina, and most of 'em went around the Elizabeth City area. But they all tried it first with the Jamestown colony. They were about to give up and go back to England. They stayed over there and got lost.

DP: Well this was probably pretty much woods when your father moved down here.

WJ: Yeah.

DP: How many children were in your family?

WJ: Now you got me again... I'm the only boy. I had three sisters.

DP: And when you grew up, where did you go to school-elementary school and high school?

WJ: Right where I was living, there happened to be a school. There were one or two places probably that you had to catch a bus or private car to get back and forth. If you were late or something, you needed a car.

DP: When you were a boy, were there cars? Did your dad have a car?

WJ: Yeah, a Model T Ford. Had to crank it.

DP: Uh-huh. Did you have electricity at home when you were a child?

WJ: [Indicates no]. We studied by an Aladdin's lamp they called it. They made right good light.

DP: Uh-huh. Do you remember any snow in the wintertime when you were a child? Did it snow in this area in the winters?

WJ: Yeah, we had some.

DP: More than you do now?

WJ: No, I don't remember that it snowed any more so as in the last two or three years. We've had two or three mighty big ones.

DP: And was it as hot in the summertime as it now?

WJ: Yes sir.

DP: And no air conditioning.

WJ: Oh, no. We had a fan.

DP: What did you do when you were in high school--when you were out of school in the summer? What kind of work?

WJ: On the farm. Played a little baseball.

DP: Do you go to college right after high school?

WJ: Yes sir.

DP: Where?

WJ: Wake Forest.

DP: Okay. And that was near Raleigh at that time, wasn't it?

WJ: Yes sir.

DP: And then did you go right on to medical school?

WJ: Uh-huh. See, Wake Forest had a two-year medical school. Carolina, West Virginia, and Wake Forest were the only three two-year medical schools in the country. They all discontinued about the same time.

DP: And where did you go the last...?

WJ: University of Maryland.

DP: Okay. And when you finished medical school, where did you first practice?

WJ: You mean after the internship?

DP: That's right.

WJ: I went back to Powellsville-my hometown.

DP: Where did you intern?

WJ: At Letterman General Hospital in San Francisco. St. Joseph's Hospital was a civilian hospital, and Letterman General was an Army hospital.

DP: Did you stay in the Army? Were you a doctor in the Army?

WJ: Yes sir.

DP: Where were you stationed?

WJ: When I finished my civilian internship for two years, I came back home to Powellsville.

DP: Were you the only doctor there?

WJ: Yes sir. No, there was a Dr. Ruffin who was just about what my age is now.

DP: And how old were you when you came there?

WJ: 17. No, wait a minute-wait a minute-whoa. That couldn't have been. That's high school. I need to go back to memory school. But anyway-!was 26 or 27, somewhere along in there.

DP: Were you married at that time?

WJ: Yes sir. 'Got married in San Francisco.

DP: Was your wife from the west coast?

WJ: [Indicates yes]. -

DP: Uh-huh, and how did you meet her?

WJ: She was the daughter of the commanding officer of the hospital where I interned, and I met her at a tennis match. I'd never played tennis 'cause my high school didn't have money for all that kind of equipment. We had basketball and baseball, too, but we didn't have football. I beat her and she got upset about it, and then we started going together. In the Army, everywhere she went, there was a tennis court. Her daddy was a doctor in the hospital.

DP: I see. Was it hard for her to adjust coming to Powellsville? That was quite a change for her to come to such a small town.

WJ: [Indicates yes]. She had never lived in a town the size of Powellsville. Washington, DC, San Francisco-let's see--and one other-some overseas place. And she'd never been in towns the size of San Francisco and Washington, DC. She was kinda lost. Well, she wasn't lost, but she would like to have gotten lost. That's kind of a dumpy place, but then we had 13 stores. Now, there are none. But people live there.

DP: You were a general practitioner there? Did you deliver babies at that time?

WJ: Yes.

DP: Where was the hospital?

WJ: There was one here. It was an old hotel--upstairs.

DP: My gosh.

WJ: They did pretty good for a one-man thing, you know. When we had to really refer something that was a problem, it was to Rocky Mount and Norfolk. Norfolk got most of'em. They'd get on a train in Powellsville--we did have a train in Powellsville--and then they'd go to Norfolk.

DP: So, did you have hospital patients? Did you travel to Windsor to look after patients, or not?

WJ: I sent 'em over here 'cause the hospital I sent 'em to was managed and operated by one doctor that was in this town.

DP: Was he a general practitioner?

WJ: Yeah, but his main interest was surgery.

DP: I see. So, where did you deliver your babies?

WJ: At home.

DP: My goodness. Did you have someone to help you?

WJ: I had my nurse. I woke my office nurse up wherever she was, you know, and I'd go by and pick her up. The midwives got $25.00, and that's what I got for deliveries.

DP: Gee!

WJ: And when I quit, the Medicaid was bringing $3,000.00. I came along too early.

DP: How about the people that didn't have-that couldn't pay the $25.00?

WJ: Then I didn't get anything. And this business about paying you with chickens and ham and eggs, I never had a single one to do that-never the first one. But it's always written by some doctor that that's what he got paid with.

DP: So you either got money or nothing, is that right?

WJ: Never got a thing.

DP: Did you have a lot of black patients, too? Or did they have...?

WJ: Yeah, we had about half and half.

DP: How many years did you practice in Powellsville?

WJ: I practiced there about three months and then I came to Windsor, and that's where I've been ever since. That was in 1937.

DP: What led you to move to Windsor?

WJ: Well, it's bigger and there was something going on. There was a little hospital.

DP: Did your wife work during that time?

WJ: [Indicates no]. She didn't work.

DP: Did you have children? How long were you married before your first child came?

WJ: I've got a son in Richmond who's a dermatologist-the firstborn-Bill.

DP: Was he born after you moved to Windsor?

WJ: He was born here in 1938. In other words, when we moved over here, he was about due then.

DP: How many more children did you have?

WJ: Three. No, wait a minute-I was thinking back when you were talking about my brothers and sisters. I had five in all-four boys and one girl.

DP: Did any of the others go into Medicine for a profession? Were any of your other children doctors?

WJ: Three of'em.

DP: Oh, really! And where are the other two practicing?

WJ: Well, one's in Richmond, one's in Greenville, and one's in Alexandria, Virginia.

DP: Okay, and what kind of Medicine did the one in Alexandria practice?

WJ: Internist-internal medicine.

DP: Is Joey your youngest child?

WJ: I have another son who is younger than him. Yes, Joey is the youngest one. I got to get the Bible down to see all those dates. They've grown up so quick, I forgot he was the youngest. I got to thinking about it the other day, and I said, 'Joey, do you know how old you are?' I said,

'You're getting old enough to retire.'

DP: Not quite.

WJ: No, but Bill is 62 or 63. He's in Dermatology in Richmond. He served his residency at Walter Reed Hospital in Dermatology, and he trained with one of the dermatologists you have in Greenville now. Kendricks? Hendrix?

DP: John Hendrix. I know John very well.

WJ: Well, he and Bill were at Walter Reed at the same time when Bill was a resident. He was in the following year or... in back of Bill. He's younger than Bill a little bit.

DP: When you moved to Windsor, how long was it before you got another hospital from the one in the hotel?

WJ: From there to this one out here? That was opened in '52-this hospital-but that other hospital-I don't know when it opened, but it closed when this one opened. I wasn't living here when they changed it from a hotel to a hospital.

DP: Did you ever use the hotel or just the doctor that owned it? Could you practice there yourself?

WJ: I was there with the other doctor here in town-Dr. Castelloe. His main forte was surgery, but he [also] did general practice.

DP: Was your office in the hotel as well?

WJ: Yeah.

DP: Just the two of you?

WJ: Uh-huh.

DP: Okay. And did you get busy fairly quickly?

WJ: Pretty good. I say fast. Of course, he'd been there a lot longer than I had. He was a World War I veteran and was in the Navy, and he was there several years before I came with him. He worked it by himself, though. No, there was a Dr. Lyon in there with him who died, and that's the reason I came to Windsor-to take his place.

DP: Did you and he share call? Would you see your own patients at night, or would you take call? one of you would be on then the other would be on?

WJ: We didn't switch.

DP: You didn't? You just saw your own...

WJ: The patient would call whoever they wanted, and if you were out of place, they'd say, 'Well, where's Dr. Castelloe?' But you could get a doctor.

DP: Did you ever get time for vacation?

WJ: I thought I didn't. I didn't have any. I thought I was supposed to be here working. I never took one.

DP: Is that right?

WJ: I tell you the truth, I didn't know what a vacation was.

DP: You mean growing up?

WJ: You know, I was supposed to be working and always going, but I always felt worse when I came home after a vacation. I was: . (He laughs too much at this point to understand him).

DP: So you felt better working.

WJ: Yeah! Definitely.

DP: That's good. Well, you must have enjoyed what you were doing then.

WJ: Yeah.

DP: Did it get tiring having to get up at night often?

WJ: Once in a while it got to be too much.

DP: Did you ever just say, 'I can't see anybody for a day or so?' Did you ever have to take a short break and just say, 'I can't see patients today.'

WJ: No. That's a bad idea. But now I found it out.

DP: How do you mean a bad idea?

WJ: Well, you should get away from your work once in a while--once in a while. But, I don't know, how populated the cities and towns were, if they ever got to the point where... The Chamber of Commerce in this town started... Everybody got Wednesday afternoon off.

DP: Were the stores closed?

WJ: Yep. Everything closed but the banks and the drugstores, but the rest of 'em were closed. But Dr. Castelloe and I never took the first Wednesday afternoon off. And then, that made the druggist stay in, you know, but that was about all. You could tell it-you could go uptown and tell it. There wouldn't be anything going on. I don't know when they discontinued that, but that isn't the fact now.

DP: Now, were you busy Wednesday afternoons because people could get off work?

WJ: No. When the town closes, everything else closes-the doctor's office, the bank, and everything like that.

DP: Was Windsor a big enough town that people would come from the country to shop?

WJ: Uh-huh.

DP: So it would get fairly busy?

WJ: Saturday was the busiest day. Now it's Monday. I don't know why that it is. There were Saturdays in this town that you couldn't get uptown.

DP: From the traffic you mean?

WJ: Yeah, it was so crowded.

DP: My goodness. What part of your practice did you like the most?

WJ: Pediatrics.

DP: Oh really? Was that from the very beginning or did it evolve?

WJ: Well, when I was in medical school in Baltimore, it seemed to me like I spent more time in the Pediatric Department and going to clinics and things, you know... The boys named me after the professor, so they were about to make a pediatrician out of me before I even got through.

DP: So that was your nickname, you mean?

WJ: Yeah. So I took a year off during my life here in Windsor and went to Washington, DC, and did one year of work in nothing but Pediatrics.

DP: How long did you practice before you went back to do that?

WJ: Oh, let's see-'37 to... I started practicing in '37, so that'd be... I went back in '52. '37 to

'52.

DP: So about 15 years?

WJ: Yeah.

DP: And did you still, when you came back, continue to do General Medicine as well?

WJ: I was intending to do nothing but Pediatrics.

DP: And did that work out that way?

WJ: No. No, it didn't work out. Some of the old patients, you know, would come, and they'd say, 'Well, can't you see me?' So I got tired of that, and I went back to the old grind.

DP: How many patients would you see on a typical day?

WJ: Well, I started work [in the] mornings at about 7:00 and would quit at 9 or 8 at night and not go home during the whole day. I'd see 100 many a day.

DP: Gosh. Did you eat right there, or did you walk uptown to eat? Where did you have lunch?

WJ: My wife would bring it to me. Of course, when I was at the old hotel hospital, I ate there.

DP: At the hotel?

WJ: When I had a clinic here in town... That closed when they opened the hospital. I had a 16-bed clinic. I built that after I came home from the Army-the war.

DP: You and Dr. Castelloe?

WJ: No, he was still up there in the old hotel hospital.

DP: So you were practicing here and then you went off to the war?

WJ: Yep.

DP: Which service were you in?

WJ: The Army.

DP: And where were you stationed?

WJ: All over Europe.

DP: Really? Do you remember which countries?

WJ: I was in North Africa and Sicily, and that ended my career. I was sent home 'cause I got hurt.

DP: How many years were you in Europe?

WJ: Well, I joined the Army in '42 and got out in '46, but I spent a few months after the Army here before I was sent overseas. I spent about a year or a year-and-a-half in the Army Hospital after I was sent home.

DP: You were injured?

WJ: Uh-huh.

DP: What happened?

WJ: I was shot in the arm-shrapnel. (Shows Dr. Pearsall his injuries). All of that bone is gone? that end. And they took the end of that off so I could do this. That joint between the two in there froze, and it wouldn't turn. So I had five operations, and during that time I was doing nothing but walking around in the hospital waiting for another one. I can't bend it any more than that, and it's smaller and shorter, too.

DP: How long were you unable to practice during that time?

WJ: Well, I came home... I think about a year. I was wearing sort of a brace-like thing. I had to hold this hand up. If it would hang down too low, it looked I had a wrist drop. I was in the 82nd Airborne.

DP: Where were you when you got injured?

WJ: Italy. Malcoseno.

DP: And were you near the front line?

WJ: I was a doctor in the front line. Battalion surgeons they called 'em, you know.

DP: Where would you treat the injured? In tents?

WJ: The first hospital you would go to-used to call 'em field hospitals. Now they call 'em evacuation hospitals. And then after they'd get through with you, they'd send you to what they called the general hospital-they were at the back lines. They were way back 40-50 miles. But the evac. hospital was tents, and it was nearer to the front, and it was not as long getting treated. the aid stations-they just don't even count-that'd be out there in the road.

DP: When you were working there in Italy and Africa, were you at an aid station or a evac. hospital?

WJ: Not to work. I was there as a patient but not in Africa I was in the 38th evacuation hospital in Italy first, and that was operated by a group of doctors from Charlotte. That's the way they organized their units in those days, you know. And then, let's see, I was in the...from up north-getting way up there, too. I forgot now. And I was in the 12th: in Naples. Then I was in the hospital in Africa on the way home-just stopped off:-I don't know why we stopped. But we got off on the hospital ship there, you know, on the way home. For some reason, when you get to coming home-war or peace-they stopped at every place there is to stop for some unknown reason. They have 'ern, you know. I never questioned 'em. One time, we had to stop-the only time I ever saw that place-we stopped at Gibraltar-had to so some English admiral or commander could come aboard and decide that you were an allied soldier and not a Gennan. We'd sit out there all night long--could have been halfway home. But that Englishman would come aboard-a hospital ship...

DP: My goodness.

WJ: ...'fore they'd let you through there. And you know, even on Gibraltar. That's the only stop until we got to Charleston, South Carolina.

DP: When you were in Europe, were you doing General Medicine-practicing just taking care of wounded?

WJ: Well, we run an aid station like you'd set up a clinic downtown and everything-like being in general practice. Of course, if there were wounded and hurt, you did what you could do back then and then get 'em out of there. Get 'em down to the evac. station.

DP: Were you usually practicing alone?

WJ: No. There were two doctors to each company. They were called battalion surgeons, and the guy with me was from Indiana and he was a graduate of the University of lndiana. He and I were in this particular company, and I stayed with 'em until I got hurt. I never saw any of them anymore, except Dr. Kitchen [who] was in the same battalion but another company, and he came back and went to Duke and finished his residency in Surgery. When you do that, you get a year's credit on your time of being a resident-you get a year's credit. If you're taking a residency with four years and you were in the service, you get a credit for one year-they'd take a year off. And I could have gotten a year off on my residency in Washington, you know, on that Pediatric deal if l'da known about it. I didn't know about it, and so I didn't take but a year of Pediatrics and I would have gotten credit for the year in the Army and I'd take another year-I was eligible for the boards-and call myself a pediatrician.

DP: You still probably would have ended up doing General Medicine.

WJ: Probably.

DP: Was it hard to just stop your practice and leave for the war? -When you came back, had another doctor taken your practice?

WJ: [Indicated no]. Dr. Castelloe was still struggling by himself.

DP: Gee. Wow.

WJ: They were hard to get.

DP: Uh-huh, right. So you were gone for how long? Three years? Four years?

WJ: I left here in '42 and came back in '46-four years.

DP: I bet he was glad to see you, wasn't he?

WJ: He was ready for some help, so I went back with him.

DP: And that's when you built your clinic-when you came back from the war?

WJ: Yeah. We split up after a while because the place was a barn. It had rats and roaches in it.

DP: The hotel?

WJ: [Indicates yes]. We delivered most patients in the bed and then carried them to the delivery room. Because we didn't have what you could call a delivery room, we'd carry them in the room where we did surgery. You can deliver 'em pretty good in the bed. A lot of people had their babies in the bed, you know-that's easy. We did most of'em in the bed.

DP: What did you use for anesthesia for deliveries?

WJ: Believe it or not, we used ol' chloroform It was the quickest and the safest. Well, ether was the safest, and we used a lot of ether.

DP: How would you deliver it? Was it with a mask that you put on the patient?

WJ: Yeah.

DP: And who would administer that?

WJ: We had a trained anesthetist.

DP: All right. Was there enough surgery for the anesthetist to stay busy, or did they do other work?

WJ: Uh-huh, uh-huh. Well, yeah, the other: in that hospital were just being general : and looking after it and making the employees work.

DP: Okay.

WJ: She kept books and did all the...

DP: Administration?

WJ: Yep. That's exactly what she did. Or if we would need supplies, she... And in those early days, you used those 4 x 4s, and she was tight. She'd use those 4 x 4s-she'd take 'em and wash 'em out, sterilize 'em, and use 'em again.

DP: Oh my gosh.

WJ: And now you couldn't do that... You'd better be ready to fly to the moon if you did.

DP: What was her name? Do you remember?

WJ: She was Ms. Sophie Burden, and she trained in Anesthesiology at Norfolk General.

DP: Was she single?

WJ: No. She was married then She came down here and went to work and got married.

DP: Now when you opened your clinic, did you keep patients overnight in the clinic? Did you have beds in your clinic?

WJ: I had 16 beds.

DP: And that was before the present hospital was built?

WJ: [Indicates yes].

DP: How many employees did you have?

WJ: Well, I had four at night and four in the daytime. Nurses, that is.

DP: Most of the time, how many of those beds were taken?

WJ: Most of the time?

DP: Uh-huh.

WJ: All the time.

DP: Really!

WJ: And I had a nursery-kept bassinets in that. I'm not counting those. And I delivered nine babies down there in one day. I delivered 365 one year and 364 the next year.

DP: Gee!

WJ: I delivered babies down there-that was my main work, you know.

DP: Did you also have to sleep down there?

WJ: Yeah, I did.

DP: Was it hard for your family and your wife?

WJ: Yeah, I think it was. I think that was bad-it's bad-it's bad.

DP: When you have to work so long?

WJ: Uh-huh, uh-huh. She'd bring me food, although I had a kitchen down there and a cook that fed - the patients. I could have eaten in there. But she always liked to bring me chocolate ice cream. That's something that I liked cornbread with.

DP: Cornbread and chocolate ice cream!

WJ: Yeah, but she would cook it at the house and bring it down there, and it was still warm.

DP: Did she make the ice cream or could you buy it at the store?

WJ: It was bought.

DP: Did your children spend time with you-the ones that went into Medicine? Did they watch you work and help you out?

WJ: No. The next to the youngest-one day-now this happened: I walked in my house and the next to the youngest one-the one next to Joey-he said, 'Mama, who is that man?'

DP: You'd been gone that long!

WJ: He didn't see [ever] me. I'd be gone when he got up for school, I'd still be in the office when he went to bed at night, and I couldn't look after nothing they wanted-couldn't go fishing or... If they went off somewhere like you say taking a vacation, my wife took 'em all crowded in the car and went. They'd go to the beach or the mountains, and I'd be home by myself

DP: Did you feel like you just couldn't get away? Did you just feel that there was no choice?

WJ: Well, I reckon I could have gone-1 could have gone.

DP: You think you just enjoyed your work?

WJ: Yes. I got tired, naturally, you know, but I've seen the time that I'd deliver a baby and come home and put my foot in the bed, and the phone would ring again. So, that's how I practiced.

DP: How did your health hold up?

WJ: I didn't have any trouble.

DP: You look healthy now.

WJ: I'm getting too old to be healthy. There's something sitting back right now waiting for me. I can't figure out what's it gonna be. I've had heart surgery at Norfolk General, and I got in the ambulance at the hospital here, and the doctor- I thought he was sending me to Greenville? and got up to Suffolk and opened my eyes and could see all those lights in Suffolk. I said,

'Damn, we got to Greenville mighty quick.' They said, 'You're in Suffolk.' And Dr. Bowyer has been my doctor ever since. There's where I go when I need to see a cardiologist.

DP: Dr. AlleQ Bowyer?

WJ: Bowyer.

?

DP: In Greenville?

WJ: Yeah. You know him?

DP: Uh-huh, sure do.

WJ: Now when I started referring 'em over there when they got the department, he was chairman. But in a little while, he was out. I don't know why.

DP: You know, Greenville has grown so much, and there are so many new doctors. Do you ever go there except as a patient? Do you know any other doctors there?

WJ: Oh, yes.

DP: Has that made a big difference? Were you in practice still when the medical school came to Greenville?

WJ: Well, it didn't do it any harm-I tell you that. I'm sure it did it good. I wouldn't worry about it. I loved the idea.

DP: Did you lose patients because people wanted to go to Greenville from Windsor?

WJ: That's hard to say. I mean, you know, that's crossed my mind, but I knew to start with that anything that would happen would help everybody-the patients, the merchants, the banker, and everybody.

DP: Since you came here, has the town grown?

WJ: This town? I think a little bit-a small amount. But comparatively speaking, it wouldn't have grown as rapidly as Greenville has.

DP: Right. How many doctors practice here now, do you know?

WJ: Oh, gosh- no.

DP: Quite a few?

WJ: Yeah. You got more PAs than anything, I think. But they got three nursing homes. Greenville has a bunch of doctors that work over here [on] alternating days. There are all kinds that come over here and work. Every specialty there is is represented here-sometime during the week.

DP: Do you actually have any of your medical care here in Windsor for yourself?

WJ: No. I go to the eye man here in Windsor. He's an optometrist. And if I want to go over there for my heart or sinuses or something like that, I go right on up there.

DP: To Greenville?

WJ: The doctors would be from Greenville, and they already have a clinic for everything.

DP: Oh, right here at the hospital?

WJ: Yeah.

DP: Well good.

WJ: Yeah, everything's right over there.

DP: After you built your clinic, when the present hospital was built, did you keep your clinic as an office?

WJ: [Indicates yes]. As soon as they opened, that's when I closed it and went for Pediatrics.

DP: Oh, I see. Okay. And then came back.

WJ: That was at DC General Hospital in Washington.

DP: And then, has this hospital grown much since it was first built?

WJ: Well, until recently when a lot of changes have been made, and I'm sure East Carolina has influenced it. They got their interests in Edenton and Ahoskie as well as Windsor and maybe some more. You might say they run the place, you know, and they're building another hospital here.

DP: That's what I understand.

WJ: Greenville will run that one. I don't know what they're gonna do with this one here, but they'll probably make another nursing home. By the time that all that takes place, say 25-30 years from now, 65% of the old folks will be in a nursing home. 'Cause the daughters and daughters? in-law aren't going to have time for 'em and work, and everybody'll be working. Everybody. And there's no way you can do it unless some other things take place.

DP: Which do you think is best? Do you think it's good for so many people to be working, or do you like it the old way?

WJ: Working and housekeeping, too?

DP: Right.

WJ: Well, I would say one of'em was going lacking sometimes, and it's gonna be the house-not where the money is.

DP: When did you actually retire from practice?

WJ: '94. I put in 57 years.

DP: What led you to finally retire? Was it hard to make that decision?

WJ: No, I just decided it was time.

DP: Did you miss it at first?

WJ: I think being a doctor, even though it's far different from being a baseball player or athlete of any type, they know when the time comes, and I think a doctor-it may be up here, mentally? but I mean it begins to slip. And they know. Other things happen, too, you know, and it probably helps make your mind up.

DP: When you first retired, was there anything that you liked to do particularly?

WJ: [Indicates no].

DP: Stayed around the house?

WJ: Mostly.

DP: Were you ever a golfer, or did you keep up with your tennis?

WJ: I played some golf, but I started playing when I was 65 and I'm left handed, so I didn't have four stars. I couldn't even play good sub-par golf, but I liked it. It's a game, but it's a sport that you got to stay with. I mean! And any little fraction of a fraction of something you do wrong will make that ball go places you don't even know are there. It gets a lot of people frustrated, and they want to come back. They watch it, and it looks easy. But the guy that instructed me on my first lesson at 65-when we got through, he said, 'Well, doctor, you'll play golf, but you'll never play par golfthe rest of your life.' And I said, 'Well, damn your soul, how do you know?' And he was right. Yeahhhh! My wife can play. Dog if she can't play. She's got all those trophies-club champion...

DP: Do you enjoy reading?

WJ: Uh huh.

DP: I see you've got lots of books-anything in particular that you...?

WJ: Well, I like history-historical things-interesting.

DP: Have you traveled around the eastern part of the state much as far as the historical things in North Carolina?

WJ: Yeah. I've been most places in the east and the west, too, over the years.

DP: How about the Hope Plantation-were you involved at all with the restoration of the plantation?

WJ: Oh, yeah.

DP: It's a beautiful building.

WJ: Yeah. It certainly is. I went on a house call in that building before it was ever considered to be what it is now. There were nigger tenants in the house, and I went in the back door. The back door was a door that went down into the basement, and the basement was full of chickens.

DP: My goodness.

WJ: And all the plastering was off the lanes, you know-that was all bad. All that's been corrected. When I heard about what they were going to do, I said they could never restore that thing-it's about to fall in. And from then until they had a ball up there, I had never been in it. Then, I could see what they had done. But it was a trash pile when I went to see that sick youngun out there. And that's the last time.

DP: Did they have heat or electricity at that time-when you made the house call?

WJ: Not every time. No, I've delivered babies by lamplight in my time. The first delivery I had was a 16-year-old girl with a prolapsed cord-in a house with no lights. She was in labor and hadn't dilated, and I was just sittin' there. But I talked to her and fooled around enough, I got that baby out. Of course, the baby was dead as soon as the cord dropped out, you know. That was my first one, and I said 'Gosh, I'm going back to live on the farm. I can't put up with that.' You know you got a dead baby when that cord's hanging out. And the mama held a lamp. It was on the kitchen table that I delivered her. She lived on the side of the road in a bunch of woods out there-about seven or eight miles down that way. The house isn't even there now. Now, then you sweat. That's hard to do because the cord's out but the baby isn't nearly ready to come out. You search and no dilatation at all. But nature somehow plays a hand in that-somebody does.

DP: Did you have a lot of house calls when you were practicing?

WJ: Oh, yeah.

DP: Mostly elderly people that couldn't get out? -

WJ: Well, there were inconveniences in those days to get to a doctor, they lived in a central location, you know. They didn't have a conveyor to get there. Now, they jump in the car and can be there in a little while. You don't have to go like you used to. But there were times, you know, when we'd have emergency calls and thought that we could do some good to go. We didn't have a rescue squad at all, so we'd always call the undertaker and he would send his hearse to bring 'em in. And they did that work free of charge-they did in those days.

DP: That must have been a little frightening for the patients riding in the hearse.

WJ: I've been stuck in this county in the mud and spent the whole day out there trying to get out. One Saturday morning, I had a call to go about 12-15 miles up here right at the Roanoke River where it comes out. And I got in a ditch, and the ditch was actually a car path that had been blown out and made a ditch out of, you know-[they] dynamited and made 'em a ditch. And they decided they didn't want it and filled it up. Of course, it was full of mud, and I thought it was a road. I said, 'I can go just as fast as I want to. That's the prettiest path I ever saw,' and I was flyin'. I hit that thing, and the car went right on 'round, and I stayed out there all day. When I got back to Windsor, my main nurse in that clinic said, 'We were about to send the sheriff after you.' I said, 'Well, Ms. Letty, this is the first day in my life that I've ever been in any place practicing Medicine that I didn't see a patient from Windsor all day long.' I stayed out there all day long getting that car out. I didn't see a patient from Windsor. And Saturday was the busiest day.

DP: Mygosh.

WJ: One thing I liked about my place, I had a drinking fountain-ice, you know, in the hall as you go in the front door. And they would come to town and sit out there in the cars while their mama or daddy or somebody would be a patient, and they would go out there and they'd bring their bottles--vinegar bottles and molasses bottles-and go in there and get my old water on very hot days, and [then] we didn't have any water to drink. They'd run it all the time. They couldn't keep up with 'em, so in those days I never had any cold water. They were in and out, in and out. They'd get out and go back to the car and drink that cold water. But Ms. Letty said she was about to send the sheriff after me. It was 5:00 when I got in, and I started out early that morning. But I hit that mud path, and that car almost disappeared. The colored people on the farm helped me get out of that thing. They brought a tractor around and they got that thing stuck.

DP: That was a fiasco.

WJ: That was a new style--they put out a new way for farmers to make ditches on your plantations for drainage without so much backbreaking work. You'd take dynamite and blow it, and it'd come out shaped like a V. I don't know how they do it. And there'd be one certain merchant or hardware folks or something like that-would keep the dynamite for the farmers--and he kept it all on one of his farms. He had it in a vault out there-a cement vault. You couldn't keep it in town. So he had it locked up, and if you wanted a few sticks of dynamite, you had to go out there to the farm with him, and that's where it was easy to store it. You could take one tractor with a hoe in front and make a ditch-just like walking-didn't have to mess with dynamite. But that looked like a path in front of me, and I hit that thing with that car-it was like hitting a tree.

DP: I bet you were surprised. When you started out, did you have antibiotics available to use?

WJ: Antibiotics?

DP: Was it easy to get penicillin or sulfa?

WJ: You know what year we got really a killer that would be called an antibiotic in a way was sulfanilamide?-in 1937. There was a company in Tennessee that first made that drug, and it was called Prontosil.

DP: Oh, yeah. I remember hearing about that.

WJ: And that was in a liquid form-ampules. Nitrogill-that was the first one they made. And they got sued 100 times I reckon and went broke over reactions from the sulfa drugs.

DP: Could you see a big difference in trying to treat patients like with. strep. throat or otitis?

WJ: Well, that's what we used, and it worked. But we didn't have penicillin. The first broad?spectrum antibiotic in this country was Oramycin---a capsule that was gold-colored, so they named it Oramycin. It was a dollar apiece. I said, 'I ain't never heard of a pill that cost that much.' But initially you didn't have to [take] antibiotics 2-3 weeks and run your drug bill up to

$100.00. All it took-you could take one dose of penicillin then parenterally and do what a dozen tablets or capsules would do, and it was a lot cheaper. But Oramycin was a dollar apiece in those days. I never wrote a prescription for over seven-one a day.

DP: Did you see much rheumatic fever?

WJ: I saw a few cases that came from strep. throat.

DP: How about syphilis?

WJ: Some. The Health Department got more of those than anybody else, and they had a treatment center in North Carolina where they sent 'em-a Health Department-Tent City. It was up around Durham. I went to it when I was operating to see it.

DP: And it was Tent City? What was the name of it?

WJ: It was... I forgot now. It was just about like the polio epidemic, you know, and they had all those treatment centers. The main one was in Hickory, North Carolina.

DP: Did you see polio yourself?

WJ: Yeah. I saw some up in Washington, DC. I seen a few around here, you know, but I forgot

? what year that was. But that thing up there in Raleigh, the state Health Department sponsored that-for syphilis. Rapid Treatment Center-that was the name of it. Rapid Treatment Center-RTC.

DP: And how about tuberculosis? Did you see much?

WJ: Not as much as you used to. That didn't even stop you from working then. They'd give you that drug that they give for meningitis prevention, you know-take that and go on. But there was a hospital in the state that took 'em-specialists, like sending somebody to the blind or the deaf hospitals. McCain. And the doctor that operated it, his name was named McCain. It was close to Southern Pines--somewhere up in that area-but it's been closed for years. They don't even send 'em to a hospital now and haven't in a long time. Well, can I get you something to drink? Coca cola, orange juice. If l keep talking, I'm going to have to have something. My throat's dry.