[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

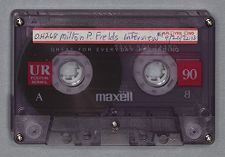

[TAPE #1; SIDE #A]

Q: University Archives Oral History Interview conducted 20 September [2013] with Milton P. Fields of Rocky Mount, North Carolina by Professor Jonathan Dembo at Joyner Library's Manuscripts & Rare Books Department in Joyner Library's Room 4014. This is Interview number 1.¹

Q: Mr. Fields could you tell us a little bit about your early life and childhood? Where were you born and when?

A: I was born in Halifax County January the 17th 1926 in a little village . called Spring Hill. The buildings have all been destroyed and there was no name on the road as there is now. The road on which I was born is now called Moonlight Road. Spring Hill is no longer in existence, really but at one time it was a thriving little community. I lived there until I was four years old. My daddy was a sharecropper. Of course, we all know what Sharecroppers were. We moved from there to a house a few miles down the road in a community called Hill's Crossroads. We lived there for a while. My daddy was still a sharecropper, but he got a job as an overseer and we moved to Palmyra.

I have some memories of the house we lived in where I was born, which are right interesting I think. The house was located across the field from the schoolhouse. It was a one-room schoolhouse. My brother started school there and my mother would let me go and visit him in the schoolhouse and the teacher tolerated this. I would sit at his desk and be with him at school with the permission of the teacher. The road drag came by. I jumped out of my seat and ran to the front door yelling "Here come the road drag! Here come the road drag!" The teacher grabbed me up and put me back in my seat and spanked my hand. That is the only spanking I ever got in school [chuckles] and I really wasn't even in school! [chuckles]

Q: What kind of crops did your father work on?

A: Tobacco was the money-making crop, but we also grew peanuts which was second to tobacco in profit and there was corn and soy beans and cotton-general crops of the area. [Coughing] And, of course, we all had a large garden with the usual crops in it: cabbage and butter beans, string beans, potatoes-both kinds- sweet potatoes and white potatoes-to some degree we were self-sufficient. We had pigs, chickens, which were for eating; but we were like most farmers, we were poor, though, we didn't realize it because everybody was poor.

Q: Did you have any contact with various government programs of the times like the Agricultural Adjustment Act [Administration]?

A: Not that I know of

Q: Did you have any chores around the house?

A: Oh, we all had chores around the house!

Q: What kind of things did you do?

A: Well, we gathered eggs, swept the yard, picked vegetables, cleaned our rooms, dried dishes- the usual household chores.

Q: Did you work in the farm at all?

A: I don't recall working on the farm in Spring Hill. I was just four years old. Like I say, daddy was a sharecropper, but he also had some people that worked the farm with him. When I got up a little larger, we had a garden that we tended, and I did all sort of chores in the garden. My mother would can vegetables in the summer and meats in the winter. We ate well.

Q: Where were you born? Was it at home or in the hospital?

A: I'm sure it was at home.

Q: When were you born?

A: 1926. January the 17th.

Q: Do you would have been five years old in about 1931 and probably started grade school soon thereafter, right?

A: Soon thereafter. I don't remember exactly the year but my birthday being in January, I would start a year later. I went to school in Scotland Neck until I was in the 4th grade.

Q: Scotland Neck?

A: We rode the school bus to Scotland Neck. (I Think that they closed the one-room school shortly after we moved away). The first school bus that I rode on had side curtains. It didn't have windows-just curtains. And it was driven by a local student. A man in the neighborhood had, I think, 15 children and the bus was almost always driven by one of his kids.

Q: How long did it take to get from your house to school?

A: I have no idea about that.

Q: Was it just one room?

A: Ah. Oh. No. This was Scotland Neck School used by the entire town plus those who came in to school by bus. While I was at Scotland Neck they consolidated the Dawson School and several others with Scotland Neck which increased the students at Scotland Neck considerably.

Q: So. Did you have brothers and sisters who went to school?

A: I had one brother who was about three-and-a-half years older.

Q: and is he still alive?

A: He's still alive. He has had his 91st birthday. He lives in St. George, Utah.

Q: Tell me a little bit about him? What kind of a career did he have?

A: He was very creative but not at school just around home. He made all sorts of toys for us to play with. He did many ingenious things, at least I thought so, and still do. Like I said, he wasn't the world's best student. When he finished school, he went over to the Norfolk area and learned plumbing and wound up as a plumber. He joined the Coast Guard [during World War II] and they put him on a landing craft. The landing craft went out and returned to Port Richmond near San Francisco, the base there needed a plumber, so they advertised on the base. He got the job and he spent the rest of the war as a plumber for the Coast Guard at Port Richmond. After the war, he was employed by the San Jose [California] school system as a plumber. He became knowledgeable about heating and cooling and worked there until he retired.

Q: Where did you go to high school?

A: I went to high school in Hobgood. I was in the fourth grade when we moved to Palmyra and I went to school in Hobgood until I graduated in 1943.

Q: What were the most interesting classes that you took in high school?

A: Oh Gee whiz. Math. English. Algebra. History. Geography and Agriculture.

Q: Do you still keep in contact with any of your classmates?

A: Occasionally. There were eight in my class that graduated. Actually, I did not graduate. I joined the Navy about a month before graduation, but they considered me a graduate. I heard from one of those last week. He had just had a birthday and he called to tell me he had finally caught up with me in birthdays.

Q: You joined the Navy in 1943. Were you drafted, or did you enlist?

A: Well I had kept up with military type things. I had been active in the Boy Scouts and I became familiar with the naval aviation projects. I wanted to get involved in that. And I talked it over with my daddy. He said if that's what you want to do you might as well do it. So we drove to Rocky Mount to a Naval Recruiting Station to enlist me in the aviation program. I could not pass the "depth vision" test and the recruiter said that he would not accept me in that. But he was top notch Recruited and said "what you ought to do is just join the Naval Reserve and I can sign you up right now". My daddy had to sign for me and again said "Well, boy, if that's what you want to do, I'll sign for you", he said. So I joined the Navy.

Q: And so you were 17?

A: Yes, I was 17 and weighed 117 pounds.

Q: so where did you go for the training?

A: [Coughing] I came home after having signed up; got my things together, said my goodbyes and caught the bus to Raleigh where we stayed at a little hotel called Hometel. We left there as a group and went to Bainbridge. (Actually went to the little village called Port Deposit, Maryland and got picked up by the bus that carried us to Bainbridge [Naval Training Center, Maryland]. Now, I did not know any of the boys. We had, shall we say, a busload of boys. There were three boys on the bus that had on coats and ties. Two were from Oxford Orphanage, I think. And I was the other one because I had always been told when you go to a place important you put on your best clothes. We arrived in Bainbridge and unloaded the bus and I looked and by chance there was a boy there that had been at school with me back at Hobgood.

We started chatting and he began telling me some of the things that I would have to put up with. Now, you will be called a blanket-blank rebel and you will be looked down upon by folks from up North, but you can call them Damn Yankees, and that was the first time I had heard that word. Anyway, we go on in and get assigned to the barracks and we went to get our shots, and uniforms and our unit stencils. And one thing I remember the man saying: "You stencil this, you stencil that, but do not stencil your soap." I don't know why I remembered that.

Q: What did the stencils say? Did it just have your name on it?

A: My initials: M.P.F. just to identify the clothes. Then we marched down between two picnic tables with Medical Corpsmen on each side. The first Medical Corpsman that you ran into had a rubber glove on with a handful of cotton that was saturated with iodine and of course, you had your shirt off. You were slapped on the shoulders, both sides you moved to the next man who had the needles. He shot you as you passed by. Some of the bigger more robust men passed out. They had cots for them to lay on. After we got our shots, we were assigned our barracks and began our boot training.

Boot training was not hard to me. I would call it a snap, but it was not hard. We were taught many things that I had already learned in Boy Scouts. I was aware of first aid. I was aware of some degree of marching, not a great deal. I could swim. I could do those sort of things.including artificial respiration. So that was not a big deal for me. Particularly the knot tying. I could tie knots as good as the instructor could. Some of the fellows had difficulties with boot training but I was not one of them. Some days we would march out on the field and semaphore. I don't think they use semaphore at all, now, and I don't know when they quit using it. I had learned semaphore in the scouts, so I was ahead of them on that. So, being a member of the Boy Scouts was a big, big help in going through boot camp.

Q: How long were you in boot camp?

A: I believe we were in boot camp about four months. 16 weeks.

Q: So that would have been May or June 1

A: April

Q: So Autumn of 1943 is when you got out? Then you must have gone to advanced training at that point?

A: Well, they took all sorts of tests and I qualified to go to the Naval Academy. They put us in a barracks at Bainbridge to hold us until the Navy Academy Program began. I went there until winter and then my eyes weakened. But coming from a school with eight in the graduating class and I was exposed to the people going to the Naval Academy prep and about half were college students and the rest of them came from schools that had more than eight in the graduating class and it was extremely difficult to keep up. And when I got to the point that I needed glasses, I didn't think I would pass the physical exam. I was having a tough time and when my advisor said I could go to any school in the Navy I wanted to, I selected photography. I left in the winter, that would be of '44 [1944] and went to Pensacola [Naval Air Station] and went to Pensacola [Naval Air Station] Florida-a good decision.

Q: So, talk a little bit about Naval Photography School?

A: I had absolutely no knowledge of photography, but I had read an article about a brave photographer who faced the enemy with his camera and guts and I felt that's what I wanted to do. In the group that I went through photography [school] with, several of them were either photographers or had it as a hobby. I knew absolutely nothing about it. We started with the very basics pouring a solution on a glass plate to use as a negative. Next came the Graflex, camera with a focal plane shutter. It used sheet film, so we learned the differences between sheet films. After that, we went to the dark room and learned about the fluids used to process the film. On various assignments we made photographs, so we could go to the dark room and practice making enlargements and that sort of stuff. Next came aerial photography: we were sent up in an SNJ from the base in Pensacola. We flew around and made photographs of various towns and things there. Then we had to come in and process the film.

We also were taught a course in motion pictures. I think the camera we used was a Bell & Howell Eyemo, which was standard at the time. They also had a camera there in the school, called a Mitchell. It was one of those large, large cameras. I was told that it cost $100,000. It was very powerful; it ran on electricity or you could operate it manually.

Q: Wat was it used for?

A: Movies. You've seen the old newsreels, the great big rolls of film: that's what it was. So, after Pensacola, I was sent to a Naval Station in Washington, DC to learn Photo-Lithography and how to make negatives for printing. I was there for some period of time. SO, photo-schooling, shall we say, took me from beginning through black & white, to movies, to aerial. I was then sent out to San Diego [California].

Q: When did you get sent from Washington to San Diego?

A: I don't remember the exact time but it was in the late spring of 44.

Q: What kind of social activities did the men in the photography school have in Washington?

A: Sightseeing primarily. And when I say sightseeing, we would go to the USO [United Service Organization] places and tour the city.

Q: How did you travel [Washington] DC to San Diego [California]?

A: Train

Q: What was that like?

A: We left the Washington area and went down South to New Orleans [Louisiana], there was a brief stopover there, not much of a stop-over, but a brief one, I knew a man who was attending the university there based on a program in the Navy and tried to look him up but couldn't find him. Didn't know where he was.

We went on from there to San Diego. We stopped in El Paso [Texas] and were held for another train to go through. We didn't get off the train, but while we were stopped in El Paso, merchants came along, outside the windows. I got my first taste of Mexican food which was not delightful, but it was my first time.

Getting back to something; back when I was in Pensacola, we used to go over to a small town nearby Mobile Alabama, for a weekend. Literally to get there, I took a trolley bus and I attended a church there. I was "adopted" by a family called Hollifield and went to their home several times and even spent the night. They had a son who was younger than I and we had some fun times together. Incidentally, I have been in touch with the Hollifields within the past ten years. But, on to San Diego where we were stationed at the Marine Barracks, whose name I can't recall. We stayed there just briefly before boarding a troopship.

Q: Camp Pendleton is outside of San Diego?

A: That's it: Camp Pendleton. We were stationed there for a while. And we had this guy in our unit who had been in litho school with me.he loved fat women. Kate Smith. You remember Kate Smith, who was a little heavy? That was his ideal. At any rate, he went down to Mexico, a little town across the border.

Q: Tijuana?

A: Tijuana. The fellow loved some of the girls down there. Changed his tastes, shall we say. Then we were loaded on a troopship headed for Hawaii. Another thing I remember about the trip was a poker game started before the ship left the dock. It did not stop until it landed in Hawaii and the people got off the ship.

Q: [Chuckling] And you can confirm that by how?

A: Hah! [Laughing] I did not play poker. I just knew that that's what they were doing. And, of course, when we left San Diego we had the usual round of seasickness. I got a little uneasy on the stomach, but I never had a problem. When we neared Honolulu [Hawaii] I was up bright and early in the morning because I expected to go ashore. It was beautiful. The water was great. And off in the distance we could see a signal light flashing and there was one from our ship and I remember that sight. Mostly, I remember disembarking there. At any rate, we pulled in at Pearl Harbor and we got off the ship there and were assigned to a holding pace, whatever they call it. We got jobs assigned to us while we were there: the usual thing. Clean up the yard. Pick up the trash. That sort of stuff. Until you got assigned to a ship. Little things I remember. We had a young boy in the group who said he was from Brooklyn [New York] and every chance he got he said he was from Brooklyn. On one of our job assignments, he was given a pitchfork and he said "Give me that mule beater. I know how to use it." And I knew then, he wasn't from Brooklyn. He was from South Carolina, somewhere.

Q: Were you still with the group from photography school?

A: There were some [who had been] in photography school.

Q: But it was mixed group?

A: It was a mixed group.

Q: About how long did you stay in Honolulu?²

A: Just a few weeks. The [USS] SARATOGA [CV-3] would come in, load up, and stay overnight. They were training pilots. And they would come in and they would go out. It was the oldest [aircraft] carrier in service at the time and I got an assignment to go on the SARATOGA with two other people, two other photographers. One was a photographer's mate, First Petty Officer; the other was a second-class mate and I was third class. We went aboard and met the people in the lab. I was assigned to a bunk in the lab. My bunk was over the drier. When I say "Drier" we used that to dry pictures. It had a gloss side to dry pictures with which gave it a gloss. The first-class Photographers mate outranked the rest of us in the lab, so He became the boss.

Q: What was the size of the crew in the lab? Just in round figures.

A: I think we had about 15 who worked in the lab. We had a striker. When I say "Striker", you know what I mean?

Q: I don't think so.

A: That's a seamen striking for ratings. We had some of those there. I think we had about six or seven that slept in the lab. We had a cot that we could use.

Q: And what were the different jobs of the men in the lab?

A: They were assigned.

Q: Were they interchangeable?

A: Interchangeable, yeah.

Q: They all had the same skills?

A: Basically, they all had the same skills. We were assigned to take pictures of things that happened on the ship. We were also on call for aerial work.

Q: Did it happen on rotation, or were you picked at random?

A: By the time that I got on the ship, they had developed automatic cameras for aerial work. Although we were on call, I don't remember any aerial assignments while I was on the ship. Our assignments were at random.

Q: Did you develop and process the film that came from these cameras?

A: Yes. We processed the film. We did the whole thing.

Q: How long would it take from the time when the camera from the plane came in before you had completed processing it and it was ready to be used?

A: I'm sorry about that. We did not do any of that during the time I was on the ship. I guess some of the crew had. I don't remember processing the cameras that were on the airplanes. But I'm sure that we did. I can remember any specific thing about that.

The head of the lab did not have a real rapport with the other photographers, but he knew me, so I got the dirty ends of his jobs and was assigned Crash Camera. Now a Crash Camera was a movie camera mounted on a tripod and placed on the catwalk right there at the flight deck. My job was to watch each plane as it was landing; if the plane got out of line and looked as if it was going to crash, you started your "crash camera", made the movie and processed it. Later, the pilot would watch it and see where he made a mistake.

I have seen many crashes. I saw so many they called me the "crash camera kid". [Chuckles] But it was a little dangerous because you were in the path of the plane as it was coming in. I don't know how familiar you are with the planes but they have a hook and the hook drops out on the deck and it's supposed to catch on a cable stretched across the deck; a cable raised 10 inches from the deck and if it [the plane] does not catch on a hook and runs forward, or the hook comes out, it [the plane] is caught by a barrier, about waist high, made of several cables, and that was to keep it from going forward and running into the planes which were parked up forward. So, when the plane came in, the flight deck crew, disconnected it [the plane from the cable] and it was taxied forward and secured at the forward part of the deck. So, we could land lanes, taxi them forward, and secure them all at the same time. And I think we could land a plane about every 15 seconds, which really took skill to do.

I only had a problem with one plane. I think that this was a SB2c which was a little difficult to land. Evidently, the chain threw, and it did not hook and it [the plane] ran through several barriers that were there. It [the plane] ran through the first barrier and broke the cables; then it veered and went over the side and to the left; and the cable went out and snapped like a whiplash. It [the cable] came back and caught my tripod and my camera and me and pinned us up against the deck. It tore the tripod and camera all to pieces, but I was fortunate that it did not hurt me. They took me down and had me examined but I didn't have any further problems from it. Though it might have been a little risky, it was really fascinating to watch the planes come in and land.

Q: So, was this a continual day by day job?

A: It was a day by day operation. Yeah. Until we went into combat. We stayed in a training situation out of Pearl Harbor there for a while.

Q: Were the planes on the SARATOGA from the time they left San Diego, I mean Honolulu?

A: I don't know.

Q: Or would they fly out?

A: They would fly out from shore, landing on the ship, and returning to base.

Q: So, after you arrived on the SARATOGA how many cruises did she make?

A: I don't remember, I can't keep up with how many times we left port. But it was decided that the SARATOGA would become a night carrier; everything was painted black and we had night landings. The flight deck crew would wear dark glasses during the day to they could be accustomed to the darkness of night. We practiced that and trained the crew for night landings.

Q: How does a photographer take pictures of landings in the dark?

A: Well, it was decided upstairs, for some reason, that they needed a photographer. They had had some crackups and they needed a photographer to make photographs of them. So, I was sent to do that. And I suppose I was using a Speed Graphic at the time with the flash. I made a couple of pictures and then I was cussed out and told "Get the Hell away from there!" because the flash blinded the flight crew. They couldn't see. So that ended the experiment.

Q: So, there were no photographs of crash landings?

A: No night crash landings because of the flash.

Q: I can understand it. That's what immediately came to my mind,

A: They put an end to that. There was one other great idea that some fellow had. Up on the bow of the ship there was a net and exactly its main purpose, I had no idea, but it was at the very bow. We launching planes all the time with a catapult and they decided that it would be a good idea to have a photographer to make pictures of the take-offs as well as the landings. Not a movie but a still picture. I was assigned that job. I used a combat-type camera for that because it would work real fast. On the second or third launch, there was a Marine flying, I think it was a Marine, flying a T40, I think it was. It was the gull-shaped plane. It was a beautiful plane, but it was hard to land. At any rate, it launched, and I heard it when the engine quit, and I started making pictures and I made pictures all the way around.

END OF TAPE #1 SIDE #A

TAPE #1 SIDE #B

Q: Just continuing. You were talking about your job photographing takeoffs and were at the point where you were discussing the second or third plane that you were photographing whose engine quit just as it launched?

A: Well we had a policy on the ship. The ship was always accompanied by destroyers. We usually had three, sometimes four, destroyers, and when the pilot crashed, the destroyers him up. Well, the destroyers bring him back alongside and there would be a big hoopallaw and it was customary for the destroyer to be awarded be enough geedunk for the entire crew³.

Q: Geedunk?

A: Geedunk. The ship had the ability to make ice cream. I mean, big as it was, it had over three thousand people on it sometimes, you know, it made ice cream and it would exchange ice cream for the rescued pilot. That was customary.

Getting back to the.they had painted the ship black and it was supposedly a night-type carrier and we were dispatched to Ulithi⁴. There some other ships along and if I am not mistaken, the [battleship USS] North Carolina [BB-55] may have been in the group. When we got to Ulithi, we could brag that as far as we could see there were ships. We had a few days there, but I don't think any of us went ashore.

Then they sent a group of carriers for a raid on Japan. The Saratoga was in that group. I assume the other ships that were there went to Iwo Jima. The job of our ship was to fly night protection. The other carriers would pull in close in the daytime and raid Japan. Then they would pull out and we would pull in close to protect the other ships.

We went from a hot climate to a cold climate and I had a problem with a nosebleed. So, the whole time, when the other carriers were bombing Tokyo, I was in the sickbay with a nosebleed. We got detached from that and sent to Iwo Jima. Just as we were coming into the Iwo Jima Theater we were attacked by kamikazes, bombs, and other items of destruction. There were two or more waves of the enemy coming in and we were badly, badly hit.

Q: This would have been February or March 1945?

A: February 22 I think⁵. And we took about 13 different hits and of those six or seven were kamikazes. The ship listed a little bit. The bow was torn up pretty badly. A lot of things were knocked out of use. They were able to get the boilers running correctly and we straightened up and we dispatched ourselves, shall we say, away from the danger zone. We headed back.

In the process of the attack we had all been assigned battle stations. My battle station was the flag bridge⁶. The ship was rigged for an admiral, if we had one, and this was an operations center. It was not occupied. So that was my battle station. I had taken my camera, my Mitchell⁷, up to the battle station and then secured it and placed the tarpaulin over it. I guess I had to climb four or flights of steps to get to it. So, when general quarters sounded off Iwo Jima, we all made for our stations and I went to my battle station. We were bombed, and it was going off all around the ship.

Q: Were you able to take pictures of the attacks?

A: I was not able to take pictures of the attacks. By the time I got to my battle station and took the tarpaulin off and got it secured and ready to run, the attack was over. The attack was just a few minutes. I was able to make some photographs of the damage, but the actual attack itself, I did not get. And that's when the tarpaulin I had used to protect the camera caught fire and it was about dark and I couldn't put the fire out. The photo officer came up and was checking on what I was doing and saw that I had a blaze going on and it was getting dark. He saw that I was stomping the flames and they were flaring up due to the wind and he started stomping. We both were stomping. And I suggested a way to put out the fire which he said, "Do it". And I did, and I put out the fire and so far as I knew that was the last flame on the deck because fires form light and are very easily seen at night on the ocean.

We secured our material the best we could, and we started cleaning up. We were all issued wartime rations or combat rations, whatever they were called. The gallery was closed and we didn't have any fresh food or that sort of thing. And it was a matter of cleanup and getting the dead ready for burial.

Q: Were there any causalities among the photographers?

A: No Causalities among the photographers. We had total causalities, deaths or missing of about 120. After we got flags for them, they were lined up and buried. I think 90 on the first day. We had the usual Navy burial ceremony. The burial device was lifted, and the body slipped off into the ocean. We had a Protestant chaplain on board and I think his name was Flowers⁸. But we buried the crew and then we had two kamikazes as best I recall, whose bodies we had to bury. We buried those last. And I remember not the prayer for the crew because was too long, but I remember the prayer he said for the kamikazes, and I think it went like this: "Dear God, give us courage to live for our country as these men had courage to die for theirs. Amen". Over the side with them

Once we got to some degree of cleanliness on the ship and the galley was working, we had a meal. And the first meal that we had that I remember after the attack was country style steak and we had pie a la mode for dessert. It was a big meal very well received.

Q: How long was it from the 22nd [21st] when the attack happened until you got pie-a-la-mode?

A: I think that was maybe two or three days. They had to get the stuff lined up. The first stop that I recall was we in to Eniwetok⁹, to get some fuel, other supplies and get further orders. Usually, when he pulled into a port, we were buzzed by all the planes. This was the first time that we saw this twin-engine Lockheed Plane¹⁰ come over and fly straight up. It was a sight to see.

Our instructions were to go from Eniwetok to Honolulu and we didn't know what was going to happen. On the way to Honolulu, we received word that the Army had lost a plane with an officer aboard and it was suggested that we do what we could to see if he could be located. So, in the middle of the night, they got an airplane ready, and they backed the ship down, to get enough into the wind, so it could fly off. We launched it off the stern and it flew around and it never found any evidence of the missing plane and officer. We went to Honolulu and tied up at a dock there. Usually when a ship came in, it was met by a band; and that was what happened. As we pulled into the dock a band was playing welcoming us in.

We stayed on the ship, getting it ready to return to a shipyard for repairs. We didn't know where we would be going for those repairs until the band started playing "California, here we come"- the crew went wild! But, we didn't go to California, we went to Bremerton, Washington. We pulled into Puget Sound near Seattle and tied up at the shipyard.

Before we even got to the shipyard thee were workers from the shore that came aboard. They cut a hole in the side of the ship big enough to drive a truck through the hanger deck where were getting ready to repair the ship. We pulled into the dry-dock there at Bremerton and there were sailors who were given liberty. They could get off the ship and go ashore to Bremerton or to Seattle, or anywhere nearby.

It just so happened that our liberty began on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, 1945. Everyone was celebrating. Our crew filled the restaurants and bars. When asked what they wanted to drink, it was milk. You go into a bar and you drink milk! We had had enough dried milk nobody liked. It was awful! Since it was going to take several weeks to repair the Saratoga, the crew was divided up, I think, into 3 groups and given leave to go home.

I got word that my brother, who was in the Coast Guard, was home. I was not in the first group to leave. So I went down to the chaplain- - you know about going to the chaplain. I went down to the chaplain and go a TS note- we won't get into what that was-at any rate, I got permission to leave, early, right then, so I left and flew home and my brother and shared a visit together. While I was home, my mother got some extra ration tickets, so we could buy meats and other foods. I brought the left-over tickets back to the ship. There was a member of the lab crew who was married, and his wife came out to stay while the ship was being repaired. They invited the crew over for supper one night and I gave her my ration tickets Se went out to use my ration tickets to buy steaks for the lab crew. I tell you that, because it came back years and years later. This fellow and his wife came from Connecticut, going to Florida, and stopped to see us. When they got to the house, I was not there. And his wife introduced herself to my wife as the first "Mrs. Fields". [Laughing] Of course, that took some explaining.

Any rate, they patched us up at Bremerton and we went on a little check-down cruise out on Puget Sound. Had a little trouble. One of the guns didn't work right and injured a gunner. And we went on down, in and out, but we stopped off in San Francisco. And while we were there at San Francisco for a few days to get supplies, my brother, who was stationed there at the Coast Guard at Port Richmond, came aboard, and he took me out to lunch. He took me out to a steakhouse where I had my first grilled steak. I had never had one before. And he ordered us some wine to go with the meal. And I had never had any wine with a meal before. We had a real good visit. I took him down to the lab and made a series of photographs-of him in his uniform.

When the ship was ready, we headed to Pearl Harbor. We were training from Pearl Harbor like we had been doing. And then we got word that the atomic bomb had been dropped¹¹. That was difficult for me to understand. Then, they dropped another one¹² and there was peace! It was a great relief. There are those who questions the use of the atomic bomb. It should have been done. It saved a lot-a lot-of lives.

We pulled back into Pearl Harbor and as quickly as they could, they converted our ship into a troop ship. We had bunks and toilets and sleeping places everywhere, places to eat, the galley ran full time. And we loaded up as the first troop ship bringing back veterans. The called it the "Magic Carpet". We loaded there at Pearl Harbor and had a big, big send off.¹³ When we pulled into San Francisco, under the Golden Gate Bridge, cars were on the bridge blowing their horns; sailboats were around blowing the horns and fireboats were shooting off their hoses. When we tied up? The bands were playing; the news people were there. It was one of the biggest events I have ever seen, ever, It was a great, great day.

We didn't stay there long before they sent up back to make the trip again. When we got back to Pearl-I was discharged from the ship-and sent over to John Rogers Field which was a naval hydrographic office. I was assigned to that office because of my knowledge of lithography, mapmaking, and that sort of stuff. And when I got there, they were in the process of closing their office. The people who were in the office hadn't been out there too long and were from the Washington area. They were to be flown back to Washington, DC. Well, since I had more points than they did, I was eligible to fly back to Washington, DC also. But since they knew more folks than I did, they flew back, and I was given the job of closing the lab. So, I closed up the lab and got the equipment stored and went on a one-man draft back to Washington. Suitland Maryland was where I lived.

Q: So when did you leave the Navy?

A: I left the Navy in April [1946]. Another little incident that may be amusing: we received our Christmas gifts while we are out at sea. Now the photo lab did not have private facilities. So, we had to go down to a shower and toilet about two decks below. To get there we had to pass through a batch of bunks that were usually occupied by other sailors. That Christmas I got a bunch of scented soap. I took my scented soap down with me and took a shower and I was smelling good. When I came back up through those dormitories, there was all sort of heads popping out of the beds, whistles, yelling. When I got back up to the lab, I threw the soap out the windows. [Laughing] I didn't use that scented soap anymore

I was stationed at Suitland, Maryland, for a while. A little side issue on that: when I came into the railroad station there at Washington, from the West Coast; I met a man that was leaving, going overseas, that had gone through boot camp with me. He had served the entire war, at Bainbridge, in the band, but since he didn't have any points, they were sending him out. And I met him at the train station. He was going out; and I was coming in. I stayed at Suitland, Maryland, until April, when I was discharged. I think I was discharged over at Bainbridge. I made negatives for maps, big maps, there at Suitland. There was a young man, who was younger than I was, who was doing the same thing, who liked to ice skate, and he taught me how to ice skate. I had a little social life there, not a great deal, but some!

Q: So, you left the Navy in April of 1946? And then I understand you went to East Carolina College at that point? What decided you to go to college?

A: Well, I don't know. I had decided to go to law school to become a lawyer. But, I had debated a long time about whether I should go to Carolina. And I was also considering going to the University of Missouri for a course in journalism, but comments that I had heard caused me to go to law school. When I got out, my daddy found me a job as a carpenter's helper. When I got a chance, I went over to Carolina to see about enrolling in the summer of 46 [1946] but it was crowded. Well I heard that East Carolina [East Carolina Teachers College] had a pre-law program, for two years. I could go to a pre-law program at East Carolina for two years, then transfer to Carolina and go three years, after two years at Carolina and get a BS, another year and get a law degree. So, I was saving on time there. I decided to go to East Carolina. And back then everybody, I won't say everybody, but a lot of people, picked up hitchhikers, and so I hitchhiked my way down to East Carolina and checked it out and enrolled and started in the summer of '46.

There were several other boys who enrolled there in the same time. That got me in ECTC as it was known at that time.

Q: Did you end up going to Carolina for law school?

A: No. No. I stayed on at ECTC. I had a professor whose name I can't remember, but He was very well liked, and he had finished at Emory and encouraged me to go there

Q: In what department was this professor?

A: He was in History, the best I can recall. Nice guy. There were three of us that were considering Emory. I planned to go to Emory after my years [at ECTC]. However, I had done some photography around school, here and there. And I got a chance to edit the annual [The Tecoan (1949)]. I thought that being the editor of the annual would look better on a resume, maybe, than some other things, so I changed and became an English major, and stayed on to edit the annual. When I finished '49 [1949], I went to Emory.

One of the students, who was in the pre-law with me became a good friend of mine. I wound up marrying his sister. So, I guess it was the right place to be at the right time.

Q: Well I'm afraid we're going to have to stop there. We're about to run out of tape.

END OF TAPE #1 SIDE #B

¹ Interview #1 by Jonathan Dembo, 20 September 2013; draft transcript 27 October 2016; transcript revised by Milton Fields, 11 January 2019; transcript re-typed by volunteer Thomas Hall, 5/20/2019; transcript revised by Jonathan Dembo, 7/8/2019.

² USS SARATOGA left San Diego on 24 September 1944 and left Honolulu for Ulithi on 29 January 1945 to form a night fighting carrier group with the USS ENTERPRISE (CV-6) for the invasion of Iwo Jima.

³ Actually, any product from the Geedunk or ship's snack bar, typically sweets or candy.

⁴ An atoll consisting of about 40 islands, in the Caroline Islands group, in the Western Pacific Ocean, about 103 nautical miles east of Yap.

⁵ The attack actually occurred 21 February 1945. 6 kamikazes struck the ship. Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/305963368404300089

⁶ The flag bridge is separate structure built above the navigation bridge of a warship, designed for the use of a naval officer higher than the rank of captain so that he can command the multiple units under his command. It is separate from and at a different level from the navigation bridge where the ship's captain was stationed.

⁷ A motion picture camera.

⁸ Lt. Jefferson McDowell Flowers (b. 1899), Chaplain aboard USS Saratoga 26 January-9 July 1945. Chaplain Flowers had been a Baptist minister in Greenville, SC prior to entering naval service. Source: The history of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Vol.3. United States Navy Chaplains 1778-1945. Complied by the chaplain activity of the bureau of navy personnel, navy department under the direction of Clifford Merrill Drury, Captain, Chaplain Corps, United States Navy Reserve, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1948. P 94.

⁹ Eniwetok is an atoll in the Marshall Islands chain which the United States had captured from the Japanese in February 1944.

¹⁰ Probably a reference to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, a twin-engine fighter-bomber that served all during the war.

¹¹ 6 August 1945 at Hiroshima, Japan.

¹² 9 August 1945 at Nagasaki, Japan.

¹³ SARATOGA left Honolulu on 9 September 1945.

---------------

------------------------------------------------------------

---------------

------------------------------------------------------------

Milton Fields Oral History Interview #1

rev. Thomas Hall, 5/20/2019; rev. Jonathan Dembo 7/8/2019 11:59 AM

fieldsm #OH 268 add 00 oral history interview #1 rev 2019 07 08