[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

| SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION | |

| ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW #95-02 | |

| John A. Tilley | |

| June 14, 2013 |

Jonathan Dembo:

University Archives Oral History Interview conducted 14 June 2013 with Professor John A. Tilley of East Carolina University's History Department by Professor Jonathan Dembo in his office in the Joyner Library's Manuscripts & Rare Books Department. This is Interview number 1.

Jonathan Dembo:

Professor Tilley as a preface to our interview perhaps you would tell me a little bit about yourself and about your background. For instance, where were your born and when?

John A. Tilley:

I was born in Columbus, Ohio on November 2nd, 1950.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you talk a little bit about your family background and early life?

John A. Tilley:

Sure. My father was an architect. He taught architecture at Ohio State [University] for 37 years, I think it was. My mother was a traditional housewife. And I have one brother who was seven years older than I am. He recently retired after 30 years of teaching zoology at Smith College, in Massachusetts. And, I lived in Columbus my entire life up to age 30 in 1980. And what else would you like to know?

Jonathan Dembo:

Where did you go to school and tell me a little bit about your early career?

John A. Tilley:

OK. I started out at an elementary school called Thomas Edison Elementary in the Columbus suburb of Grandview. I went to Grandview High School and then I went to - for my undergraduate work - to a place called Capital University, which is a small Lutheran school on the other side of Columbus. I didn't want to go to Ohio State because it was so big. Then I went to Ohio State for grad school. I got my BA from Capitol with double major in History and Music in 1973. [I] graduated from high school in '69. I got my MA in History at Ohio State in '75 and my Ph.D. in 1980.

Jonathan Dembo:

What particularly interested you in public history?

John A. Tilley:

I got out of the Ph.D. program at Ohio State at the very bottom of the job crisis. I think I sent out probably 40 legitimate job applications, that I was legitimately qualified for, and I got two interviews: one was to be a live-in dorm supervisor-teacher at a private high school in Minnesota; and the other was a one-year, non-renewable, non-tenure-track appointment to fill-in for somebody who had come down with a brain tumor at Ball State University in the middle of the Indiana corn fields. And they wanted me to teach American history, Chinese history, Latin American history, and Historiography for one year. And I didn't get either of the jobs. So, I was getting desperate.

One of my several stupid but harmless hobbies is ship model building. And I entered one of my models in a competition that was being sponsored by the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia. And I won a medal in the contest and in the correspondence that I got into with the museum they asked me when I was going to pick the model up. 'Cause that was to be done sometime late in that summer, I guess this was summer of 1980. And I said . . . it's difficult for me to answer that question because I am about to receive one of the most useless documents that one can receive in the United States: a Ph.D. in History from Ohio State and I have no job prospects and I have idea where I am going to be or what I am going to be doing at the end of the summer, but I will get back to you. Let's see, I guess it was in August of that year. The Nautical Research Guild, of which I was a member - still am - was holding its annual convention at the Mariners' Museum and I went down there for that. And waiting for me at the entry counter was a package of the usual convention-type materials and attached to it was a little note saying "Mr. Sands, the chief curator, would like to see you." And I went to see this guy and he said "Hi, I hear you're looking for work" and I ended up as the assistant curator for collections, which meant that I was in charge of all the three-dimensional objects at the Mariners' Museum, except the full-sized small craft, which had their own curator, and that meant that, among many other things, I was in charge of ship models. So that little model started my career. [Its] still got it in the pride of place in our living room.

Jonathan Dembo:

When was that?

John A. Tilley:

That was 1980. I started in October of 1980 and the museum was a fascinating place to work. Looking back on it now I see many enjoyable aspects of it. The starting salary was $13,000 a year with a Ph.D. and even in those days that was awful. And, three years later, I was up to $14,800 and every bit of the increase had been eaten up by increases in the rent on my apartment because one thing - I guess this is way off subject but I've always found slightly, bitterly, amusing - one thing about living in an apartment in Newport News is that any time an aircraft carrier comes up the James River for a refit, you know your rent's going to go up because several thousand Navy families are going to be looking for residences to last them for a couple of years. And, the apartments all belonged to landlords who borrowed money from the FHA [Federal Housing Administration] and when this great influx of renters shows up, FHA lets them raise the rent. So, my rent went up, I think, about $2,000 a year at the same time my salary only went up about $1,800. And then -- when must it have been - in the spring of '83, the museum announced that it was having a financial crisis and freezing all staff salaries, and the following Saturday, after they made that announcement, you could hear typewriters banging in offices all over the place: people typing job applications. And I typed three: one was the Naval Academy, one was the Smithsonian, and the other was ECU [East Carolina University]. And that one panned out. That's how I came to ECU.

I should emphasize - I always tell my students this - that those three years that I spent at the Mariners' Museum were my entire career as a public historian. Now, I guess, unless they have changed it, one of the categories of public history, as identified by the NCPH [National Council on Public History], which is part of the AHA [American Historical Association].

Jonathan Dembo:

Could you spell out the [acronyms]?

John A. Tilley:

NCPH: National Council on Public History.

Jonathan Dembo:

OK?

John A. Tilley:

One of the categories is teaching public history so technically I've been a public historian ever since 1980, but I only actually worked in the trenches for three years.

Jonathan Dembo:

OK?

John A. Tilley:

Which is one of the big reasons why, when I've taught museum studies I've always put a great emphasis on field trips and getting the students in contact with people who are in the trenches.

Jonathan Dembo:

So you began at ECU in the fall of 1983?

Jonathan Dembo:

Fall of '83.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was, I mean besides the fact that there was a job advertisement, what was about ECU particularly, attracted you about writing the application?

John A. Tilley:

Well, you hit the big one. It was big enough, which was they had a vacancy. And, let's see. The Education Officer at the Mariners' Museum, Joe Gutierrez -- I don't know if you happened to meet him or not: he was a graduate of ECU and he was a friend of Bill Still, who of course was the founder and head of the ECU Maritime History Program -- and I think what happened was that Joe told me that ECU had a vacancy and that I should get in touch with Bill Still. So, I did, and Bill kind of took it from there. He decided he wanted to see me get hired and I came down for an interview and, I'll never forget it, the chair of the search committee was Charlie Cullop -- have you met him?

Jonathan Dembo:

No.

John A. Tilley:

OK. He was an Early National Period, I guess he taught some Colonial History, but at any rate, the first question out of his mouth was "I understand that you play the violin?" which made me practically fall over backwards and we got along real well and Bill [Still] was on the search committee and Fred Ragan was the chair and I have heard that I was the second choice of the Personnel Committee and the first guy turned it down, but that's just rumor. It's the kind of thing I just don't want to know about. At any rate, they hired me and I've been here ever since.

Jonathan Dembo:

Describe moving to Greenville and ECU at that time in the early '80s. What were your early impressions and where did you live? What did you find interesting or unique or different about Greenville and ECU?

John A. Tilley:

This is the kind of thing that - I don't know how this is going to go - but this might be the kind of thing that I'd want to restrict because I drove down here for the interview. I had to take money out of the credit union to buy gas for my car. And I signed the contract and all that and sometime later -- about a month later -- I made a trip down to Greenville to look for a place to live. And let it be noted that Greenville in 1980 was a lot different that it is in 2013. When I got back from that trip I went to see my boss at the Mariners' Museum, John Sands, and said "John, that place is awful. If you can arrange a $2,000 raise for me, I'll stay." [Laughing] And the board of trustees said "No." In retrospect: Thank God! But, I was not impressed. The one thing I did like - other than the fact that the salary was $20,500, which was a lot by my definition at that point - was that the rent was cheap. And, I've always said that one thing that I think makes ECU kind of a difficult place for people to leave is that there aren't very many universities of this size and caliber in places where the cost of living is so low. I don't remember how much my rent was but it was much lower than in Newport News. And I lived in a little upstairs - downstairs apartment, two bedroom, called River Bluff Apartments, which has gone to seed since then, and that's out just on 10th Street just past the corner of Greenville Boulevard. You've driven past it a million times. At that point it was next to a cornfield. And I remember thinking, 'cause I moved down there in August, I thought Oh Boy! Next summer I am going to be having corn-on-the-cob once a week and that SOB planted soy beans [Laughing]. The space across the street was all farm fields and it's just incredible how Greenville has evolved since then. Not all for the better. The crime rate, of course, has gone up and so many other things. ECU attracted me largely because remember I was coming from Ohio State, it was so small. I think at that time the student population - you can get reliable numbers on this and I don't happen to have them on my head - student population was about 13 or 14, 000, I think. What is it now, 22 or 23,000? Something like that?

Jonathan Dembo:

More. 27 [000].

John A. Tilley:

27,000. OK. Ohio State was 56 [000]. Students were treated like numbers. And in my last several years at Ohio State as a grad student I had been teaching my own sections of survey courses and in 1980 ECU just didn't do that. The Ohio State History Department consisted of 40 people with a student population of 56,000 and the ECU History Department was 30 people with a population somewhere between 10 and 15,000, I think. I liked the idea of teaching freshmen. I was still young and I liked the idea of . . . I came to teach. I did not really come to do research. I came to teach. And I've always been more interested in the teaching aspect than the research aspect. I've regarded the research as something I can do and I enjoy it but I've always thought of myself, for better or worse, as a teacher. And that was what I wanted and it looked like ECU would give it to me. Since then, of course, ECU has got so much bigger. I told several department chairs the day you prop me up in front of a classroom with 100 students in it is the day I go looking for a job. But it hasn't come to that yet. I think it may in the next few years.

Jonathan Dembo:

Uh Huh. Can you describe some of your associates in the History Department and on the faculty at that time? [Laughing]

John A. Tilley:

[Laughing] Oh Yeah!

Jonathan Dembo:

Did you become close friends with anyone?

John A. Tilley:

Yea. If I'd have known you were going to ask me that I would have looked up the roster in an old calendar.

Jonathan Dembo:

You mentioned Bill Still, Fred Ragan? Other members of [the Department]?

John A. Tilley:

Ken Wilburn, who came on the same day I did, is the only one who is still there, who was there in 1980 -- 1983, I'm sorry - and all the others are gone. Quite a few of them are dead. Bill Cobb, Mary Jo Bratton, Loren Campion, Phil Adler [?], Lala Steelman - I don't know if Joe Steelman's still where he is, I haven't seen him for a long time - a depressing number of them have passed away. All the others have retired or moved to other places. The one I had the longest relationship with was Henry Ferrell who even in those days - and I don't care if you --- he will be flattered if he hears this - he was a crusty curmudgeon in 1983. Fred Ragan was such a wonderful, classical, southern gentleman and I always trusted him. I always knew he would give the straight scoop on things. I remember Bodo Nischan. He's another one who's gone now. Walter Calhoun, who is still around - I saw him just a few months ago; Charlie Cullop, Herb Rothfeder - I guess he's still around - Tom Herndon, who was the Medieval Historian; Tony Papalas, I think Tony had come in '66 or '67 or something like that - you could find that out; and Tony is now retired; he just finished his phased retirement last year, I believe. Tony was the last person they hired before me and that's a gap - that's a demonstration of how the profession was working at that time -- a gap of 1967 to 1983 when they didn't hire anybody. That's a product of the Vietnam War and the crisis in the History Departments in universities in general. Well Dahlia Lauderes was the head secretary. In fact she was the only secretary. The History Department did not have a Xerox machine. It had one computer in the office. You had to furnish your own typewriter. We had two copiers. One of them was an awful old ditto machine that left ink on the back of the paper. The other was the even worse mimeograph that punched the holes in the sheet of flexible plastic or whatever it was. And you had to touch up your mistakes - of which I made thousands - with correction fluid that was bright red - Yech. You probably remember those things. Very few people do now, I guess. I remember when they bought the first Xerox machine and I had this second, but from a very reliable source. They had it in a room across from the office from where the secretaries sat. There were two secretaries by then. And Loren Campion went in there with something to copy and a cup of coffee in his hands. And a few minutes later he came out running for the bathroom and came back with a big bundle of paper towels and disappeared into the copier room again. He had dumped his cup of coffee into the Xerox machine. [Laughing] So they immediately had to get in a tech to fix it. Why that stuck in my memory I can't imagine, but as you probably know as you get older your long term memory is pretty dad gum good for details and your short term I might forget your name in the next ten minutes. It's an interesting experience but I know a lot of stupid, useless, little stories about the History Department like that.

Jonathan Dembo:

Now, could we switch a little to your teaching interests? What were the courses that you taught in those early years and how have the course changed over the years?

John A. Tilley:

OK. My official areas for my Ph.D. were American Military History, first, and American History from 1763 to 1815; British History from 1815 to 1918; and Modern China. There I can pass on a piece of advice to anybody who cares to listen to it. My Ph.D. advisor did not say very many profound things that I heard, but he did give me the advice to take some courses in Asian history and his line of thinking was that it would make me more marketable. Maybe it did a little bit. But I took two courses in Japanese History and two in Classical and Modern China and they were four of the most fascinating courses that I have ever taken. It was so different and the progress of Japanese and Chinese history was so different from than what I was accustomed to and one thing in my memory was that text book in Modern Chinese History was called The Rise of Modern China by I. C. Y. Hs?. H - S - U with an umlaut . And it was the most beautifully written textbook. I'm not really good at reading textbooks, frankly, most of the time, but I would start to read the assignment in that book and a couple of hours later would realize that I had read three chapters when I was supposed to read one or something just because it was so artistically written and I think that may be a commentary on the Chinese conception of scholarship. You hear - well I had a grad school professor who said most historians are not literary creatures and certainly some of the worst writing that I have ever read - I bet you have had the same experience - has been by professional historians. But the Chinese don't see that there is a difference between a literary creature and a scholar. And I've always tried to remember that. I don't claim to be the world greatest writer, but I certainly work at it. But to get to what you're asking: what I was really trained to teach, first of all, was military history, American Military History. And Conner Atkeson had a lock on the one course that ECU offered in American Military History which, at that time, was a one-semester course, covering the whole thing from the colonial period to the present. I really wanted to teach that but for the time being in the beginning everybody taught, let's see, [at that time] everybody taught it doesn't seem like it was actually 4 - 4, it was actually 4 - 3. Yea. Four in the fall; three in the spring. And in the spring I taught three sections of American History Survey. I think that's how it was. I may have been wrong. It may have been three. It was three sections of American History and 5920 the Introductory Museums Studies Course. And in the spring I taught one section of a survey course - either 1050 or 1051 - and the Museums Studies Practicum 5930; and we started offering Historic Preservation - meaning preservation of old buildings. My sort of predecessor, Herb Paschal, had put that course in the catalog but had never taught it. The idea was that it was to be team-taught by originally him and somebody in the Planning Program and then Herb died and Wes Hankins of the Planning Program and I started teaching the preservation course and thank God my father was an architect 'cause I knew absolutely nothing about preservation except what I had learned in helping Dad remodel the house we lived in in Columbus. We moved into that house in 1955 when I was five years old and when he died in 1990 he still wasn't finished remodeling it. And my brother and I are agreed that we learned a whole lot about electrical systems and carpentry and tools and just about everything else, air conditioning, vinyl floor laying. The biggest thing we learned from it can be summed up in two words: Never again! And now our house is getting kind of old and when something needs to be done to it I am happy to say: "I can hire somebody to do it." But I had to learn historic preservation pretty much from scratch. And my Dad had been a member of the German Village Historic Preservation Commission in Columbus which was one of the first in the country. So he could tell me a lot about that, actually. But I started out with those three public history courses and I've been teaching them ever since.

Jonathan Dembo:

Can you give us a brief description of the philosophy behind the public history course? What was it designed to accomplish? And how it fits into the department? And even how it allows the department to fit into the statewide UNC system?

John A. Tilley:

Maybe it would be useful if I started out by talking about the beginnings of the public history program.

Jonathan Dembo:

Sure. Sure.

John A. Tilley:

OK. Now here I am talking slightly out of turn because it got started a few years, a very few years, before I got here. Originally, and you'd have to find the date when this happened from some reliable source because it was before my time. But for many years there was no History Department; it was the Department of Social Sciences. And sometime, a few years before I got here, I don't know how many, the Department of Social Sciences got broken up into History, Psychology, Political Science, Sociology, Anthropology, Geography. I think I've listed all of them. I may have missed one. At any rate there was a big, wholesale, change in the as we then called them, the general education requirements and the enrollment in history courses started to drop precipitously, largely because, I think, very few people would argue with this: history has the reputation of being difficult, largely because we required essay exams and we still do and I hope that we always do. And, let's see, it was Sociology, I think was the first one, was the first one that came up with the idea of offering a BS degree which would differ from the BA primarily in not having a language requirement. And, when they started offering that BS in Sociology their enrollments sky-rocketed because so many kids just refused to take foreign languages, if they could possibly avoid it. And pretty soon Sociology had a lot more majors than History.

And I don't know who had the idea first in the History Department - I suspect it was Paschal, who was the chair - maybe History could do the same thing. Now they already had a BS for the preparation of teachers that led to the Teaching Certificate. But somebody thought of the idea of having a BS in Public History and the big attraction that it had was that it would not require a language. Instead it would require some professional training courses and an internship. And the Department thought that that was a great idea. Now, here's where I'm foggy about it. I do not remember when I came here in '83 was there actually a public history major in the catalog. It sticks in my mind that there wasn't. But some of the courses were there, including yours and mine. And Paschal taught History 5920 and 5930; and Don Lennon taught History 5910. [Noise in the outer office] Somebody need you?

That was how things were when I got here and I don't know exactly how it all worked. I do remember that I got made the chair of a Public History Committee whose job it was to prepare a presentation to the University Curriculum Committee for I think it was for the creation of the public history degree but it may have been just a major revision to it. I honestly don't remember. Anyway, we worked on that. The committee was Don Lennon and Bodo Nischan and at least one other person and I don't remember and me and Fred Ragan sat on it ex officio because he was department chair. And what became clear to me very clearly was that to put it quite bluntly most of the people in that department didn't really give a damn what was in that program as long as a foreign language requirement wasn't because they were looking for a way to attract majors. I am trying to remember who else was on that committee. I can't. It'll come to me. I think Todd Savitt was on it. Todd Savitt was an adjunct who taught History of Medicine. I haven't seen Todd for some years but I think he's still around. I think he may have been on that committee. Anyway, we went to the University Curriculum Committee and the Department of Foreign Languages opposed it because it didn't have a language requirement. And I remember coming up with some pleasant language to try make it look as though we were not deliberately trying to dodge foreign languages, which we were -- they were, I wasn't particularly - but at any rate it got through and that's going to be the way it looks the first time it shows up in the catalogs, which I suspect would have been if there was an '84-'85 catalog or '85-'86 or whatever. They issued them every two years in those days. Of course, they were those big, fat, printed documents. That was the official beginning of it and the public history courses were: History 5910 Archives and Manuscript Management; History 5920 and '21 the Museum Studies Course; History 5930 and '31 which was called Field and Laboratory Studies in Museum and Historic Site Development and I've always called it the "Museum Studies Practicum"; and History / Planning 5985 the Preservation Course. That was it.

And by my definition we didn't do it right. We were just plain off in the wrong direction. The public history program for a long time had three tracks. One was, I think, one was called Archives & Manuscripts Development and one was called Museums and Historic Sites and the other one was called History in the Business World. And in ECU's defense, it ought to be acknowledged that public history and a field for history departments to offer was quite new at that time. I think the first programs got started at UC Santa Barbara and University of Utah in the early '70s, I think, at the earliest. And NC State had one, by this time, and, uh, I think, everybody acknowledges that public history came into existence as a result of the job crisis of the late '70s and early '80s, uh, that historians were trying to find work, historians newly minted from grad schools were looking for work and had to find it somewhere other than universities cause the universities just weren't hiring. And, uh, one place where they did sometimes find work was in businesses. Uh, the summer after I got here - the summer of '84 - the university helped pay the money, in fact I think the university paid the whole thing, for me to go an institute on teaching public history at Arizona State for a month. And that was the only formal, face-to-face, training in public history that I have ever had, but it was good, and the people who were running it were some of the sharpest pioneers of the public history field. Uh, and one thing they talked about was how businesses hire public historians. Wells Fargo had a bunch of public historians on its staff, people with Ph.D.s in history, who uh for instance when the government proposed, the Congress was considering, a measure that had to do with the banking industry, the public historians would dig up the history of other such regulations and tell the Wells Fargo lobbyists how to lobby. And the oil companies were doing the same thing and so on. And, uh, somehow or other that sector of public history, they said it had sectors, uh, got into the heads of the ECU History Department and they decided they wanted a concentration, or whatever, in History in the Business World. And I don't think I ever managed to convince them, completely, of what public history business world sector really was. They got the notion that somebody with a public history in the business world concentration, it was just something he could use to go out and get a job doing anything, where the employer didn't care what his degree was in, and, uh, we had a little bit of friction when these people in the business world - I made a mistake earlier; I'll come back to it - would go out looking for internships and some guy would say, well, he had an internship working for a restaurant and I'd say what does that have to do with history? And, well does it have to have something to do with history? Well, yeah! And Fred Ragan didn't understand it either. Uh, and some people got kind of mad at me 'cause number one . . . . [Tape ends]

John A. Tilley:

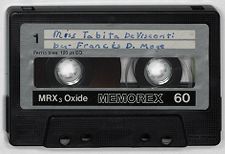

Uh, OK. Jon, you're talking to a history professor. It's hard for me to stop talking. You won't need more than one more [tape].

[Sounds of cassette being removed from recorder, new cassette being inserted.]

Uh, I let it be known that I just plain didn't like that History in the Business World track because I didn't have access to the kind of internships that would have been real history in the business world. I didn't know of anybody in North Carolina - I still don't - who hires professional historians to do history in a business context. And, uh, Mary Jo Bratton and I, at one point, got into a real knock-down drag-out [fight] about it and that's better not discussed. At any rate, I was always opposed to it and, uh, the response was always, well, I just didn't know what I was talking about or that we needed this business world thing for people who couldn't get jobs as historians. Well, I would say, that's not what public history is for and they would say I just didn't know what I was talking about. And then I really got in trouble when I suggested that public historians could use foreign languages just as well as anybody else could; that when I went to the Mariners' Museum I frequently had to correspond with people in France and in Germany - and I had a little French and a little German from college - and one time I had to take a couple of gentlemen from the Cousteau Society around the museum and they didn't speak English very well so we communicated somehow in French. Um, I thought that not having the language requirement was a mistake and over the years we tinkered with it a little but it stayed pretty much that way for quite a while.

Now, I'd like, if I may, to go back and correct a mistake that I made earlier and it was a pretty big one. I said that the three tracks in public history originally were Museums and Historic Sites, Archives, and I think I said, Oh yeah, and History in the Business World. I was wrong. There was no Archives track. The other one was Maritime History. And Bill Still was never a big fan of that because he said that there were not decent jobs in maritime history contexts for people without Masters degrees. And my response was well there aren't really decent jobs in museums and historic sites for people without Masters degrees. And, well, you just don't know what you're talking about, or whatever. Um, Bill Still never disagreed with me on that point, I will say that but a lot of other people did.

The NCPH has always taken the position that public history belongs on the graduate level. I have always maintained that in North Carolina an exception is justified because this has always been - at least up to the present time -- an excellent state for people to look around for jobs in public history institutions. And they do hire undergraduates. We've had a pretty decent record of job placement for our graduates, um, anyway, I wanted to correct that about the maritime history track.

I've been talking for too long without interruption. Jonathan [Laughing] have you got any questions or directions you like me to steer here?

Jonathan Dembo:

I certainly didn't want to interrupt the flow of your thought. Um, I have a couple of more clear points that I really would like to hit, particularly, how has the program changed over the years? And, if you can identify particular changing points that would be very helpful and the number of students to give me an idea of how many were in the program and how that's grown and changed and how your role has grown and changed and finally some assessment of its success or failure and your predictions for the future? If you lose track of any of these [questions] I'll be happy to remind you.

John A. Tilley:

I fought for years to get the foreign language requirement put back into it [the public history program] - into it, rather; it had never been there - and, um, I was always told for a long time, if it has the foreign language requirement, you might as well not have it, because people won't take it. And I always said that wasn't true. Finally, when would it have been? I don't want to get too personal here but one particular individual in the History Department dropped his opposition to it and agreed that the - No! his first move was he agreed with me that there was no point in having the History in the Business World concentration so we dropped that and I felt like that was such a victory I didn't want to push for more than I had gotten to try to get the language requirement put in at that time. So we took the Business World track out, thank God! That was an embarrassment! And, uh, the big moment in the, well, the two big moments in the development of the History -- the Public History Program -- it hasn't changed in size a whole lot over the years. Uh, it's generally ticked along at about 12 undergraduate majors and we've got a graduate concentration in public history that's - that goes back to the Mike Palmer administration which was what? 2002-2003, something like that, maybe a little earlier - and that's ticked along with five or six [graduate students]. I've always contended that public history, by definition, is a small program and it should be because the job market doesn't justify more. And the number of public history programs in the country has been going up far faster than the number of jobs has been going up. And an awful lot of people with Masters degrees in public history don't get jobs there. Uh, the big development -- the first big development -- was when we hired Gerry Prokopowicz. I had been fighting for years to get an additional public historian. We had managed to add a few more courses. Uh, LuAnn Jones, our North Carolina historian for some years, offered a course in oral history. Now, I question whether oral history is by definition public history but, at any rate, we offered that. And Larry Babits was teaching a course in living history. And it seems to me that there may have been one or two more that didn't draw . . . well, actually, one thing about the public history program is that the courses, individually, do fine given that they are on the 5000 level. Uh, they satisfy the requirements. Enrollment in the Museums Studies course had -- 5920 -- had an all-time low of 7, I think, shortly after I got here, and an all-time high of 21. That's bigger than it ought to be, frankly. Uh, it was an awkward year. But 5930, and the Preservation course, have done fine; the Archives course has done OK; um, but I wanted another public historian and we finally got approved to get one - you probably know about the case of Don Collins - who came over, his tenure got moved from the Library to the History Department shortly before he retired, and the minute he got there to the History Department I started smacking my lips and trying to lay the ground work: when he retires I want that position for public history. And it was a little bit of a fight because Tim Runyan and the Maritime History Program wanted it. But, um, I won and we hired Gerry Prokopowicz. And Gerry, of course - you know Gerry - he'd come from that Lincoln Museum in Indiana and was and continues to be intensely dedicated to public history. And he and I worked up a proposal for a revision to the Public History Program which included the language department . . . requirement.

Jonathan Dembo:

What was the time frame for this?

John A. Tilley:

Well, uh, when was that? How long has Gerry been here? That's where you're going to need to look in a reliable source. About ten years ago. Maybe a little bit longer. I'm trying to figure out the math of it. It was while [Michael] Palmer was still chair and, uh, Palmer became chair in '99 and he served three terms, 2009? -- it must have been before that - I think 2005-2006, maybe, something like that. Gerry could tell you off the top of his head, of course.

Jonathan Dembo:

Five or Six?

John A. Tilley:

Something like that, I think, yeah. Uh, I may be a little off but I think so. Uh, we revised the Public History Program - undergraduate - to its current form. Uh, including the language requirement and one of the first things that happened was that, statistically, the public history majors - although there weren't very many started having the highest GPA's in the History Department. Those were good students and they still are. They go into public history because they want to; because they are really interested in doing public history; not because they are dodging a foreign language requirement. And we had quite a few whose necks I wanted to wring before then because they had no interest, whatever, in working in museums or archives. You had some of them [in HIST 5910 Introduction to Archives]. They were just dodging foreign languages. And I remember one of them whose GPA got so low and he screwed up an internship, I think, and he said "Well, it looks like I'm just not going to be able to get the degree in Public History. I'll have to do something else." And I said "Adios, muchacho! [Farewell, friend!] You're taking a foreign language. Um, that's your problem." But, um, that, I consider a turning point: when we added the language requirement. And it didn't actually affect the number of majors significantly, as far as I can tell. We still get about a dozen in any given moment and uh when Gerry became chair - seven or eight years ago, now, something like that - uh, he has always been a stalwart supporter for public history. Um, and he's found ways every year in the budget to hire you to teach the 5910 and Scott Power to teach the History of American Architecture course - we put that in the catalog. Um, I wrote the course description package for that. Scott never saw it. Um, I told him that I would be glad to show it to him but it was utterly irrelevant because nobody else would ever look at it again. I was right. Um, and that's been a big success. Um, I regard it as a small, successful, program. The University has now decided that it's too small and has decided to do away with the major. Uh, Gerry has been trying very hard to put a bold face on it and convince us that this is actually good for the students. I am not convinced. I don't like it that the legacy that I'm going to leave to ECU is that the program that I worked on for 30 years is going to be eliminated. We'll still have the minor in Public History. Gerry and I argued until we were blue in the face that there was no point eliminating that program. That it was not going to save any money because it didn't cost a nickel. Uh, the courses were all doing fine. And, uh, we're keeping all the courses. The exceptions are that oral history course, which we haven't been able to find anybody to teach since Lu Ann Jones left, and the living history course, which Larry [Babits] only taught a couple of times and now he's retired. Um, but the University is not going to save any money by eliminating that major. It's going to have another scalp to hang on the door, that's it. And I don't care who you let hear that. It's stupid. I'm 100% opposed. Anyway, that's how things are now.

Jonathan Dembo:

Well, I thank you very much. I've kept you [over time].

John A. Tilley:

I thought you wanted me to say anything about 5910?

Jonathan Dembo:

Oh, Yes! Yes! You have mentioned 5910, but if you could spend a few minutes describing the structure of the program, the type of students who are in it, whether or not you think the program's been successful, how they and whether it's your impression that the students actually get jobs in public history afterwards?

John A. Tilley:

OK. Now when you say the "program" are you talking about the whole [public history program]?

Jonathan Dembo:

No, the class in particular?

John A. Tilley:

Don Lennon told me at one point - now this was long time ago - that every person who had taken that course and had gone looking for a job as an archivist had found it. That was a long time ago and I haven't heard you observe on that subject, but uh, I think the record's good. I think that the record's very [good].

Jonathan Dembo:

I think I can agree with Don on that point, although I couldn't say "everyone" because I don't hear from everyone, but everyone who graduates from my course I offer a recommendation and everyone's that's asked me for a recommendation for a job or another graduate appointment has gotten it, maybe not on the first try, or at the first place, but they ended up getting it.

John A. Tilley:

I've got the impression that it's got better placement record that the museum studies courses and, um, that course got started before I got here. Don was teaching it when I got here. Paschal had been teaching [coughs] - excuse me - had been teaching the museums studies courses - Don taught the archives courses - and um then Don had his tenure moved from the History Department to the Library and there was a rather bitter dispute there. I'm not confident enough of my understanding of it to talk about it, frankly. I suspect Don would be happy to [talk about it]. Uh, but, at any rate he quit teaching 5910 and I remember sending him a letter at one point - we didn't have email in those days - saying "I wish you would reconsider this, uh, because, number 1, it's a pretty important course in the Public History Program and, number 2, it has the reputation of being such a good course and we can't find anybody else with credentials to teach it." And I remember he suggested a couple of people who could be hired as adjuncts to teach it. I think one of them was, or maybe both of them, were in in Raleigh. At any rate there was a period in there when we didn't teach it. And [laughing] uh, if you've got enough tape on there, I'll tell this story. It's pretty funny. We had this undergraduate student named Elizabeth Petty. I don't think that she'd object in the least my mentioning this. She was a good student and a rather headstrong young woman and she wanted to major in public history and one of the requirements for the public history degree was 5910. Well, I was the advisor, of course, for all the students in the Public History Program and I told her we would find her a substitute. And she said that wasn't good enough. She wanted to take the archives course because that was what she wanted to do. Well, that was pretty reasonable. Roger Biles was the chair at the time. And Bill Cobb, who was the Director of Undergraduate Studies, somehow got the notion that that this girl was the daughter of Richard Petty, the stock car driver. It turned out that her father's name, indeed, was Richard. He was an investment banker in Washington [laughing]. But at any rate Bill Cobb was afraid of her and so he and I were both putting pressure on Roger: "For Christ's sake, Roger, find somebody who can teach this damn course." And that's where my memory falls apart because I remember the day he walked into my office and he said: "John, I have solved the 5910 problem." And he had found some guy - Roger was a wonderful guy; he was a real loss to ECU when he left - he found some guy in NC State, who was willing to drive over to ECU one night a week and he taught that course in the spring semester for several years and I wish I could remember his name and I can't. So that's one you really ought to look up. But I think he taught it until you came. And . . .

Jonathan Dembo:

Then 2001 is the first spring semester I taught it. Cause I arrived in July 2000.

John A. Tilley:

Uh huh. So he must have been teaching it for several years there, uh, not just one or two. At any rate, Ms. Petty graduated perfectly happy and she got to take the course and her father was not the stock car driver.

Jonathan Dembo:

[Laughing]

John A. Tilley:

And, uh, at one point, Mary Jo Bratton practically bit my head off - she was the acting chair for a while - about Elizabeth Petty. But, at any rate, that's what I know about 5910. I have never tried to get involved in how it's run. I assume you people know what you're doing and I have every reason to believe I'm right. So I've let that one tick along at its own pace.

Jonathan Dembo:

Thank you very much. I'm about to run out of tape and that was my last tape. So I thank you very much.

John A. Tilley:

Well I'm sorry I ran over so long.

Jonathan Dembo:

You took so much time as we had.

John A. Tilley:

Yeah. In early years I have my military history students do interviews with people who can remember some significant event in American military history. And one of them that I'm teaching right now -- she'd interviewed a Vietnam vet -- and she said she wanted to interview somebody who was part of the Anti-War Movement in contrast. And I said that's a good idea. And she said do you know anybody I could interview because I'm not from around here. I don't know people. And I said, well, Carl Swanson went to Canada during Vietnam and, um, for rather obvious reasons; and Don Parkerson served in 82nd Airborne [Division] but when he got out he became a member of Veterans Against the War. They'd be good subjects and I'm sure they'd be happy to talk with you but I don't know whether they're in town. And they weren't. And I said, well, I'll approve your doing something that I don't normally approve: If you want to you can get in touch with my wife. And Anne was furious with me because this coincides with the last few days of the workweek at the end of the school year and she has been absolutely swamped. But last night she did her oral history interview with this girl and I was able to say, "Well, Guess what I'm doing tomorrow, so we're even." [Laughing]

Jonathan Dembo:

[Laughing] The family that gives interviews together stays together.

END

Transcriber:

Date: