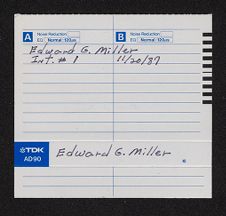

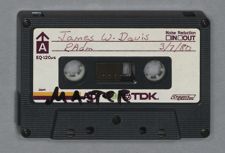

[This text is machine generated and may contain errors.]

Brigadier General Edward Lee Faulconer, Sr., N.C. National Guard

Narrator

Donald R. Lennon

Interviewer

Wrightsville Beach, N.C.

December 10, 1988

Donald R. Lennon - DL

Edward Lee Faulconer - EF

DL: East Carolina Manuscript Collection oral history interview conducted December 10, 1988, with Brig. Gen. Edward Lee Faulconer, Sr., North Carolina National Guard, at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina.

[Break in recording]

DL: If you will, give me a little bit about your background and your education before you enlisted in the-.

EF: Well, Greensboro High School is all the education that I've had. I didn't go to college.

DL: So you were a native of Greensboro.

EF: Yes, born and lived there all my life until I moved down here. I tried to go to the Mexican border in 1916, underage, but my father found out that I had enlisted so he told Capt. Myers, who organized the field hospital, that I was underage. So Dr. Myers, the next morning when I went up for drill, he told me, he said, "Ed, your father says you are not eighteen." I said, "He's correct." He said, "Well, we can't have you then. We'll have to discharge you." (1:29, Part 1)

So then a friend of mine. I wanted a little military service [Laughs] so a friend of mine told me to enlist in the National Guard there in Greensboro, which I did. I was still underage but the captain of the company there knew me and he said, "Well, you're big enough to be eighteen. I'll take you just the same." So I enlisted in the Guilford Grays in 1916.

We was called out for camp down here at Fort Caswell; stayed in camp down there for fifteen days. The captain came round and said, "Faulconer, report to the hospital." So I reported to the hospital at Fort Caswell, passed the examination, so he said, "You're okay." I said, "Okay for what?" That was a medical doctor. He said, "For the Mexican Border Service." I said, "Oh my God. I'm going down there anyway, am I?" So he said, "You will detail on recruiting service." That was in 1916, up in the mountains. (2:52, Part 1)

Well that was during the flood of 1916. So I went up in the mountains, up there at Marion, North Carolina, because we couldn't go any further because all the bridges were out. I stayed there, and they had a shooting up there one Sunday. Virgil Butt: He was from Bakersville. So I met him when we got into Bakersville up there, and his father was a doctor and we engaged him for the doctor to examine our recruits if we found any. So his son, Virgil, happened to be there. He was right out of the Army so he came round and introduced himself. He said, "Well, I'll be glad to help you, see if I can't help you get some recruits up here." I said, "Well, thank you." He said, "Do you play-?" What was it? [unclear 03:48]. No, not Setback. Durn it. What's that other game? [Laughs] I forget now what it was. I said yes so he said, "Well, I'll bring two more men with me and we'll have a game up here." (4:03, Part 1)

So he left that night right around about 11:00, and that was on Wednesday, and Saturday I saw him in Marion. He borrowed a dollar and a half from me. He said, "I have a quart of whiskey in the express office. My wife's here. I'm going to do better. I need a quart of whiskey for medicinal purposes." He said, "I have a quart down there in the post office and I need a dollar and a half to get it out." So I let him have a dollar and a half.

Well that was on a Saturday. Sunday there was a shooting in Marion, I'd say about maybe a half a mile or a mile from where we were billeting, room and board. So he came in there and he shot his wife seven times, in the kitchen, walked outside, and there was some people on the outside, you know, for the reunion they were having there, and so he started shooting up there but he was downgrade and shooting up. But he hit one man but it glanced off. It ricocheted off his forehead but didn't damage him much. (5:24, Part 1)

So then the sheriff called the governor and got him declared an outlaw. Well, he deputized us. We had a lieutenant and a sergeant and a corporal and a private, so he deputized us to hunt the outlaw. And the governor put on the bill there: "Shoot to kill." So it was reported that he was going to Bakersville to kill his father and stop at his sister's house on the way up and kill her. So they detailed me and. Well, let's see. I was in the crowd. [It was] Lt. Thorpe and Sgt. Sumner and Pvt. Faulconer to go to Greenlee up there and guard his sister's house, and also the children. So we went up there one night; got up there at night, dark. We talked to Mr. Tate up there. They detailed me to walk around the house all night long.

DL: [Laughs] (6:33, Part 1)

EF: Broad open moonlight, right on a cliff. All he had to do is walk right around that cliff there and pop me off just any time. [Laughs] He could shoot me any time he wanted to. Thorpe and Sumner. Mr. Tate had a store about a mile down the track there on the CC&O Railroad and he had some ammunition and rifles in there. So they decided to go down there and lock themselves in that store [Laughs] and guard the rifles and ammunition and leave me to walk around the house up there.

Well, about 2:00 in the morning, I saw a light coming over the mountain and I went out and stopped them. It was a couple of men and his wife and some bloodhounds. He said he was a [unclear 7:26] detective agency from Asheville and he wanted to know what was happening. I told him all I knew. So they left me and went on into Marion and left me walking around the house. So I had to take Mr. Tate's children to school the next morning [Laughs] which I did. (7:50, Part 1)

So then we came on back. No, I stayed up there for a while. Thorpe and the other detail there, he was detailed to go with the hunt. [They were going to] Linville Mountain. The dogs picked his trail up there and lost it at Linville Falls up there, the river. So they came on home [and on] Sunday we found him over on Mount Ida. As you go into Marion, Mount Ida is on the left. We found him over there dead. He had an empty rifle and a bottle of cocaine.

So then we went to Rockingham, North Carolina, on recruiting service, and from Rockingham back to Fort Oglethorpe to be mustered out of the service. Then we came on back to Greensboro. Then the war came along. That was 1917 they called in the service, and they sent us to Fort Caswell, North Carolina, right down the river here. We stayed down there for about a year. We organized trench mortar outfits and anti-aircraft outfits, and the captain of my company wouldn't let me be transferred. I wanted to go across to France. He said, "No, I'm keeping you here for a trench mortar outfit," and I first started in a trench mortar outfit. (9:32,Part 1)

DL: What was Caswell like at that time?

EF: Fort Caswell? It had two regular Army companies and it had some twelve-inch mortars. We were assigned to the twelve-inch mortars. It had a battery of eight-inch disappearing guns-I think it's two batteries-and then a small outfit of three-inch guns, and also a battery of twelve-inch mortars. We were assigned to the twelve-inch mortars, Greensboro Company was.

So then we got notice to organize a trench mortar outfit. We'd already organized two anti-aircrafts, one sixteen-inch railroad battery, and one trench mortar battalion. So finally Jim Townsend, the captain, let me. Then they were asking for a hundred and thirty-five men to go to Fort Eustis, Virginia for Battery B of the 31st eight-inch Howitzers, so I finally got transferred into that. So we went up to Fort Eustis assigned to Battery B and so forth and stayed there for a while and we were ready to sail but the Armistice was signed, so I didn't get across then. (10:59, Part 1)

So I came back, remained in the Guard. No, I didn't. No, wait a minute. Yes, I did, remained in the Guard. Then from there. No, I was discharged. Beg your pardon. I was discharged. So, I organized, went to war-I mean came back, came back from Fort Eustis. So then I got back in the service with the company there in Greensboro, and then left there during the war for Fort Caswell and stayed down there until I went to Fort Eustis, and stayed in Battery B up there until the war was over and I was discharged. So that was after the war.

So then I got back in after the war and was made a second lieutenant. I had to pass an examination. You had to go to school and pass the examination for second lieutenant, which I passed, and also was awarded the second lieutenant by Gen. [John Van Bokkelen] Metts, Adjutant General of North Carolina. So I stayed in there until World War I. (12:16, Part 1)

DL: World War-.

EF: Wait a minute. I'm ahead of myself here. That was before World War I. No. I'm ahead of myself. I came out of Battery B of the 31st Artillery after the war was over, then came back in and enlisted in the National Guard in Greensboro and remained there until World War II.

DL: What did you do in your civilian pursuits between World War I and World War II?

EF: I was with the railroad, Southern Railway Company.

DL: So from the very beginning as a young man you went with the railroad.

EF: Yes, that's right.

DL: In what capacity?

EF: As a clerk, mechanical clerk, car department. Then I went over with the Atlantic & Yadkin Railway Company as mechanical supervisor. After the old A&Y Railway. You know, part of the old CF&YV Railway that operates from Wilmington to Mt. Airy? (13:22, Part 1)

DL: Yes.

EF: So I went [as] mechanical supervisor and then went up to assistant general manager, and then general manager, and then vice president and general manager, then president of Atlantic and Yadkin Railway. The Southern Railway stepped in and bought the properties of the A&Y and I went with them as-let's see-as assistant vice president. I was sent to Macon, Georgia. So I stayed down there a little while and Southern Railway got into politics and sent me back to Greensboro. They organized the old North Carolina Railroad Association. So they wanted me to go to a little politicking for them. They organized the North Carolina Railroad Association and I was appointed chairman of the executive committee of the North Carolina Railroad Association, and Coast Line had the general. They had a man, Mr. Howell, he was chairman of the general committee. The executive committee is kind of the hatchet committee, you know.(15:08, Part 1)

So all the time that the General Assembly was in session I spent most of my time down there as a watchdog. I stayed there until. Let's see. Yes, stayed there until I retired from Southern Railway. Of course I retired from Southern Railway as assistant vice president but I was president of the A&Y before I went over to the Southern Railway.

DL: Where were you at the time that World War II came along?

EF: Came along?

DL: Yes, sir. Where were you at that point in your career?

EF: I was with-.

DL: With Atlantic & Yadkin at that time?

EF: Yes. [Pause] Of course, my promotions within the Guard, you had to take courses, you know.

DL: Yes, sir.

EF: To get promotions. (16:28, Part 1)

DL: So you were an active officer in the Guard in 1941 when the United States entered World War II.

EF: No, I was not. They called the Guard out in 1940 for twelve months. I was assistant-.

DL: What was the reason for calling it out?

EF: Oh, well, they knew they had to get in it, so they called all the National Guard into service in 1940. They called some men, you know, early. They called my outfit in early, in August of 1940, for twelve months. The president of the company told me, he said, "Okay. I'll let you go for twelve months. After twelve months I want you back here."

So, we were in for twelve months and we were still in the service. The president wrote me and told me, "It's time for you to put in your application for a discharge, for relief from service." So I wrote Carl Durham, the Congressman, and he didn't do anything about it, so I wrote the president and told him what happened. So he wrote Sen. Reynolds in Asheville and he got to work on it and he got me released. (17:58, Part 1)

But, I couldn't stay out of the service. [Laughs] So I got back in, and then Southern Railway organized the 707th Railway Grand Division. It already had one operating battalion in Africa. That was the 728th. They wanted me as executive officer of the 707th Railway Grand Division. [unclear 18:30] was commanding officer of the 707th. So we were called into service. We went to Fort Slocum, New York for basic training. I'd been through maybe six different times of basic training. So then they sent us to Fort Harahan, New Orleans. We worked with the Southern Railway then, you know, getting ready to go across. So we left Harahan in December, I think, of 1943, overseas, and we stayed in Europe there [until June of '44.]

[Pause] I came back. Let's see. When were we released? After the war sometime. Get my memory together here. I got back in 1946, I believe, from overseas. I went back with the A&Y, Atlantic & Yadkin Railway. (20:26, Part 1)

DL: When you arrived in Europe, where did you land?

EF: Well, I'm going to give you a guess. It was in December of '43. [Pause] We were sent down to. Let's see. We arrived at [unclear 21:17], England, Firth of Clyde; went across to Castlebury, I think, then from there to Newbury. We remained in Newbury until they sent us up to Kirkham on the Scottish border. We stayed up there and then were sent back to go overseas. We were at Southampton. We left from Southampton and landed in England. I think. Let's see. [unclear 22:03] in England? It's all kind of fuzzy right now. We landed in England in December of '43 and then we left Southampton in '44 to go across the Channel. I don't remember what day it was. We landed in. Left Southampton and stopped at Omaha Beach. (22:44, Part 1)

DL: So you landed there at Normandy.

EF: Normandy, yes. We went across Omaha Beach and then into Cherbourg. We moved from Cherbourg into. The first place was northern France, up there. I forget that. Then we went into. Oh, damn it. If I had my files here I could tell you exactly the dates and so forth. From Normandy to... We went from Cherbourg to Antwerp and remained in Antwerp for quite a while and then left Antwerp and went to some place over there in Germany. I don't recall.

DL: What was your specific assignment?

EF: My specific assignment?

DL: Right. What were you doing?

EF: Oh, I was executive officer of the 707th Railway Grand Division.

DL: And what specifically was the 707th doing? (24:21, Part 1)

EF: Well that was the group that was a kind of a headquarters group. See, the railroads, the Army railroads, were kind of on an organizational [unclear 24:30] as it is in the Army but there's different names to them. That was non-combat. It wasn't a combat unit. It was a headquarters unit for several railroad battalions.

DL: All within the Transportation Corps?

EF: All in the Transportation Corps, yes. So we were just supervising the operation of several railroad battalions, not on the front lines; back far from the front lines. So in the Railway Grand Division we had twenty-three officers and fifty-six enlisted men. That's headquarters.

DL: Right. Now, the armies had swept back and forth across that terrain from Cherbourg and back through in there any number of times at this point and the place had been bombed. What kind of conditions were the railroads in? (25:38, Part 1)

EF: What kind of conditions?

DL: Right.

EF: Well they were in fair condition because the engineers went in there first, you know, and filled up some of the potholes and rebuilt some of the bridges.

DL: What about the engines and the train cars? Had they been brought over from England, or were they-?

EF: They were organized over here, you see, the railroad operating battalions: the engineers and firemen and [unclear 26:03] people.

DL: But I mean the moving stock, the railroad cars and engines.

EF: Oh, they were brought over from here [and] were assembled over there in London, the freight cars. A lot of them were assembled in London. They shipped the locomotives over, not intact but some parts, you know, they had to put those together. You have a railroad shop battalion too, heavy shop, and also in your operating battalion you have a maintenance, you have a transportation-and that includes the engineers and firemen and so forth-and also a single detachment and a hospital train. In one company there you had maintenance, engineers and firemen and signal, and also heavy repair; I mean, repairs the cars and locomotives. Three companies in there. (27:08, Part 1)

DL: I didn't know whether any of the rolling stock, either the French or the German rolling stock, had survived at this point whether you could utilize it or not.

EF: Oh, yes. We utilized it. It was the same gauge railroad. See, Russia is the only railroad that's about five feet; different gauge. All the rest of the railroads over there were regular gauge, I think four feet, seven-eighths inches. So we don't-no trouble with that.

DL: Well you were operating in the headquarters there well behind the lines-

EF: Oh, yes.

DL: -but were the train cars able to go up to the front lines to deliver supplies?

EF: No, not up to. They went up as far as the dumps. The dumps were a little bit back from the front lines. So they went as far as the dumps and then the trucks went from the dumps on in, and also the trucks handled it from Cherbourg on into the dumps, right up to the front lines. (28:13, Part 1)

DL: So there's no serious problems with the Germans trying to cut the railroad lines or anything.

EF: No. They had the Germans on the run there. They didn't stop. They kept going. They weren't there long, different places. Now, Patton came through. He broke through St. Lo on May 19 and so he went on from St. Lo into Le Mans. That's the railroad center. Then from Le Mans he went on into Paris. Well he didn't go into Paris; a little bit to the right of Paris there. They wanted de Gaulle, you know, to go into Paris. That son of a bitch. [Laughs]

DL: [Laughs] [unclear 29:03] [Pause] In thinking back, in the headquarters' operations, what are some of the highlights of what you were actually doing, that the headquarters was actually doing in handling the-? I suppose you did a lot of the railway logistical movement? (29:50, Part 1)

EF: Oh, yes. We supervised the operation of the railroad operating battalions. They'd take orders from us.

DL: Were they just hauling in supplies or were they bringing POWs and personnel back?

EF: Oh, yes. We were hauling POWs and also supplies and everything.

DL: What were they doing, shipping them to Brest? Where were they shipping the POWs to?

EF: Well they had different locations for them. We had a camp there of POWs close to Cherbourg. They spread out all over Europe, the POW camps.

DL: Well I know one time they were bringing them stateside, bringing them here to the United States.

EF: Yes, but I don't-.

DL: Was it that late or was it earlier that they were doing that?

EF: That was later, and then I don't know when they started shipping them to the U.S. It was later. But we didn't handle any. We happened to be right up there where we didn't handle any of the POWs. That fell to some other railroad operating battalion. It just depends on where they were captured and where they were. (31:06, Part 1)

DL: What about specific incidents that you remember? In talking to Naval officers they call them "sea stories," and I know the Army had its own version of particular incidents that took place, that stand out in your mind.

EF: What now?

DL: Particular incidents, little episodes that happened while you were there that particularly stand out in your mind.

EF: I don't quite understand what you want. Something that happened?

DL: Anything-.

EF: I'm a little bit deaf now, you know.

DL: Any particular incidents or events that took place that were out of the ordinary that you particularly remember.(32:05, Part 1)

EF: No. Everything worked smoothly. I remember one time there we had several derailments that blocked all our trains out of Cherbourg there. We had about twenty-eight trains backed up beginning around Ville. Down at St. Lo, Ville? Ville's down there left of St. Lo. So we had about twenty-eight trains backed up on account of derailments and so forth.

DL: What caused the derailment?

EF: Well, accidents. They just split a switch just or most anything.

DL: Non-sabotage.

EF: No, no sabotage. We had those little old caboose cars that were just a two-wheeled truck, two wheels on the rear and two in front. Now over here, you know, they have four wheels, four-wheel truck. They were easy to get off, no doubt about that, off track. And then some of the potholes that were filled up, you know, with sand and so forth, they'd kind of sink down a little bit and throw one off. Most anything could happen to cause a derailment over there. (33:23, Part 1)

DL: [Pause] What was the reaction of the French people?

EF: Well now, some of them, the majority of them, they were happy to see the American forces over there [unclear 33:58]. But some of them, you know, did not. Some of them were... What you call them? Some of them went along with the Germans. Now we were allowed to occupy any of the buildings that were occupied by the Nazis before we landed in France. Some of them went along with the Nazis so they were the ones that were thrown out of their lodgings and buildings and so forth and the American forces occupied them. [Laughs] After talking to some of the girls over there, you know, we... We also hired some of the French people to work in the office to relieve the men, so they'd tell us about riding street cars over there in Antwerp and their coattails would get out of the back of the seat, you know, and they'd smoke cigarettes and they'd put that cigarette over there and burn holes in them. [Laughs] But, I don't know. It's just what you hear. You'd hear a lot of things over there that weren't true. (35:25, Part 1)

DL: Had the cities you were in been devastated very badly?

EF: Yes. Now, St. Lo. Cherbourg wasn't much. Of course it was bombed. We bombed the hell out of Cherbourg when we went in there. [Maj. Gen. J. Lawton] Collins took Cherbourg. Patton came through, broke through St. Lo and went on south to Le Mans, and Collins took Cherbourg.

DL: Gen. [Ira T.] Wyche was part of Collins' forces.

EF: He was?

DL: Yes, sir.

EF: He was with the 7th Army.

DL: He may have been.

EF: Yes, it was the 7th Army. Collins was 7th Army. He's the one that captured Cherbourg. He captured Cherbourg in the afternoon. The German general there surrendered to Collins in the afternoon on some such a date there. I don't remember. (36:35, Part 1)

DL: We've got Gen. Wyche's diaries and it gives all of that specific [unclear 36:40]-

EF: [unclear 36:40]

DL: -Yes, sir. He was part of Collins's army. Go ahead. You were talking about the destruction of the towns.

EF: Oh, yes. The 19th Infantry Division, I think, went into Cherbourg, the 19th or the 29th one. I forget which one. [Pause] The 29th in the 1st Division was over there at Omaha Beach. They spearheaded the Omaha Beach invasion.

DL: Well, you all eventually moved on into Germany proper.

EF: Oh, yes. Yes, we went. The first place was [unclear 38:02]. No, not [unclear 38:04]. We went into Holland first. We went into Belgium, Belgium through Holland, Holland over into Germany, and the first place in Germany I think was. [unclear 38:19] but it was. No, then we went from there to. The first place there was Haltern, Germany. Haltern to Herne, Herne to Wesel. We built the first railroad bridge-that was under our division, the 707th-across the Rhine from Büderich, Germany into Wesel, Germany. That was the first railroad bridge across. The other one was the Mainz bridge. It didn't take us but about twelve days, I don't think, to put that bridge across. (39:11, Part 1)

DL: A pontoon bridge?

EF: No, a railroad bridge.

DL: A regular railroad bridge.

EF: Oh, yes. [39:20 With the engineers too.]

DL: Right.

EF: The second railroad bridge was at Mainz, Germany, across the Rhine.

DL: Was there must resentment or hostility from the German people after you moved into the area?

EF: Oh, no. They were glad to see us, especially the DPs, the displaced persons, you know.

DL: Right.

EF: They really played hell over there with them. They were scared of them. They'd walk into a German house and get what they wanted. They'd kill cows over there. A German family there with a cow, they wanted something to eat, they'd go out there and kill the durn thing and cook it. We would have people there, especially at Haltern. We had people to call us to come help them out if the displaced persons were down there robbing their house and raising hell, breaking up everything they could get their hands on.(40:34, Part 1)

When we crossed the Rhine there at Wesel I picked up a little sixteen-year-old Russian boy. He'd been working in the coal mines over there. I made him my orderly. He couldn't speak one word of English so when we'd move I'd tell him, "Gehen." He knew what that was, "going." He'd get everything I had, all of my equipment and so forth, pack rolls and everything else, packed nicely and right in the Jeep. All I had to do was get in the Jeep and we'd go wherever we were going. He was quite a boy. Couldn't speak one word of English. He worked in the coal mines over there for four years. He was sixteen years old then. They brought him over when he was twelve. That's when we crossed the Rhine and there were six DPs. We put them all to work.

We brought some of the clerical force out of. The captain brought a lot of the clerical force out of Italy on down where he was. He brought his complete barbershop with him. [Laughter] You could get a haircut for ten cents. (42:04, Part 1)

[Pause] I have some pictures of old Patton. We gave him a train over there, gave him a five-car train we had. He had Güring's observation car. We found that in Munich and we sent it to the shop. So, on the observation end, he had a marble table back there with the maps up here on the ceiling. All he had to do was pull them down and then this marble table had a slot-in the table, you know? The maps would come on up there and pull them all the way and slide in the other side of the table.

He had a bathroom. I swear that tub wasn't big enough for me to get in. And he had his mistress's bedroom back at the other end of the car. And we found a baggage car for him that had an electric ramp at one end. It would take his baggage and also his car. When he wanted to stop and get out, you know, stop at a place there, he'd just open the doors of this baggage car and he had this electric ramp and he put it on this electric ramp and went on down. [Pause] That's when he lost his command, when he came over here. After the war? (43:49)

DL: Yes, sir.

EF: He was killed right close to Heidelberg. [Pause] The V-1s and V-2s were kind of a little bit of worry there in Antwerp. They were trying to knock Antwerp out-the terminals, oil terminals?

DL: That was after y'all had moved into it?

EF: Oh, yes. They sent them over there, you know. Every day you'd have the V-1s and the V-2s come in. I have a picture of one in flight there, the V-1. You could see those. It was just like a "put-put," a motor boat. Our billets for lodging were right on the milk route, we called it [Laughs] coming in from where they were coming from, right down that street. "Put-put," you could hear them, but whenever that motor cut off you better duck somewhere. [Laughs] She's falling then. Where it's going to hit you don't know. But the V-2s, that was the big ones. You never heard them until they hit. (45:12, Part 1)

DL: Well now, were they accurate enough that they did any substantial damage?

EF: What?

DL: Were they accurate?

EF: No, they weren't too accurate. The V-2s, now, they were heavy devils. They'd really knock a block down, almost. The V-1s weren't quite as destructive as the V-2s. I have a picture of a V-1 there in flight. They tried to knock Antwerp out with V-1s and V-2s. Old Haw-Haw, Lord Haw-Haw, you know, he was a turncoat. Well, he came on the air one Monday night and he said-.(45:58, Part 1)

[End tape, side one]

DL: -the destruction of Antwerp beginning at 1:00?

EF: 7:00, a Wednesday. Well, that was Monday. About 7:00 the first one hit, right on the minute. So the provost marshal there in Antwerp said a hundred and six fell on Antwerp that night. I don't think so. Of course I didn't hear but about. I heard about maybe about sixteen or eighteen or twenty go off. I had a bottle of Scotch-. [Telephone rings]

[Break in recording]

DL: Now did you go anywhere for protection, when a raid would begin like that?

EF: What?

DL: Did you go anyplace special-

EF: Oh, no.

DL: -for protection?

EF: I just stayed in my quarters. A lot of them went to the air raid shelters. They had an air raid shelter just two or three doors from where I was billeting.

DL: But you didn't bother with it?

EF: Oh, no. I didn't bother with it.(0:59, Part 2)

DL: [Laughs]

EF: If it's going to hit I knew the air raid shelter was going too, so what's the use? [Laughs]

DL: The air shelters were in the form of a bunker or something?

EF: Yes. They were downstairs in the basement of buildings and so forth. They had a lot of cots and so forth down there, you know. Each one had his own sleeping cot, bed.

DL: But you just sat back with your bottle of Scotch. [Laughs]

EF: [Laughs] Yes. I didn't drink much of that stuff but that night I did. After about the tenth bomb came over I did take a drink. [Laughs]

DL: Well, the reason for him going on the radio in advance to tell that it would be destroyed, was that to give civilians an opportunity to get out of the town? (2:04, Part 2)

EF: Well, just for propaganda purposes, like Tokyo Rose. They wanted to worry you to death.

DL: Had much of the civilian population fled those areas or-

EF: No.

DL: -were they mostly refugees [unclear 2:25]?

EF: A lot of them were killed at Antwerp. They stayed at home mostly except at night. Then they would go to the air raid shelters at night. One explosion there by a V-1 hit a theater there in Antwerp and they said about nine hundred and twenty-seven were killed, but I don't believe that. A lot of them were killed. One hit right outside our headquarters there in Antwerp. That was the railroad station, passenger station. That hit one afternoon along about 1:00 and it killed thirty-three that afternoon. That was just about maybe two hundred yards from our headquarters at the railroad station. A couple of our men got hit. Not much damage to them though but they were hit. (3:33, Part 2)

DL: What was the range of the V-1?

EF: Of a V-1?

DL: Where were they firing, or where were they coming from?

EF: Well I don't know; never did find out. [Gen. Bernard] Montgomery cracked Antwerp. He went right on through. He didn't go [by] the emplacement of those V-1s and V-2s. No, he didn't go by there. He just passed it up and went on through, went into Arnhem up there. That's where he got his tail spanked. I think thirty-five thousand airborne troops dropped there at Arnhem. Somebody said that the Dutch. [That] he failed to consult the Dutch about the tanks getting up there, coming up, and said he didn't pay any attention to it, and said he got to Arnhem or someplace up there and he got bogged down. That's the place where the Dutch told him the tanks couldn't get through there. The roads wouldn't accommodate them. Now, whether that was true or not, I couldn't say. (4:58, Part 2)

DL: [Pause] Well now, in providing the logistical support that you did, where were the supplies coming from? What depot were they coming from that you were shipping to the front?

EF: I think all of them were coming from England.

DL: But they had to come through some French or Belgian port-.

EF: No, they came direct from England into Cherbourg on the ships there.

DL: I didn't know whether they came in at Cherbourg or Brest or where.

EF: Cherbourg was the first port of entry we had and Le Havre was the second. I think the plan was to get two ports of entry there at the beginning of the war. They wanted the English, you know, Montgomery, to take Le Havre at the same time we were taking Cherbourg, and also Collins, where he landed at. What was that place? What's the name of that thing? Durn it, I. Of course [unclear 6:30] was Omaha, and Collins' entry there was. Montgomery's-the English-was [unclear 6:40] if I'm correct.

DL: [Pause] Did you say that the Vichy French caused you much trouble? (7:12, Part 2)

EF: The what?

DL: The Vichy French.

EF: Vichy French?

DL: They were the group that didn't cooperate very well.

EF: Oh, yes. I know what you're talking about now. Well, no. I don't remember any trouble. Of course we were with the railroads and they didn't cause the railroads. We were operating most of the yards there, you know, in Cherbourg. Then we turned it over to. You operated a railroad in three phases: strictly GI; then GI and civilian but all military operations would go first when we turned it over to the French; then full French operation.

DL: Where were you on V-E Day?

EF: V-E Day? I was in Herne, Germany. I think it's H-e-r-n-e. I'm not sure. Not far from Haltern. (8:40, Part 2)

DL: Then how long a transition period was there after V-E Day before you were able to turn the railroads over to the Germans?

EF: It wasn't long, just a few days. Of course the U.S. military came first. All military operations came first over the railroads but then they could do what they wanted to with [them].

DL: Well I imagine y'all were kept quite busy moving American troops out of Germany and France there for months, weren't you?

EF: Oh, yes. [Pause] Well after the war, you know, they were getting kind of short on petrol, they called it, gasoline and so forth. They said, "Is this trip necessary?" [Laughs] I remember the first convoy going through there of trucks you know, boys from the front going home. They had a big sign on the freight car: "Going home. Is this trip necessary?" [Laughs] (10:14, Part 2)

DL: [Laughs] Well of course the trains operated on coal rather than petrol. How was the coal supply?

EF: How were they supplied?

DL: Was there a good supply of coal for the trains?

EF: A good supply of what?

DL: Coal, c-o-a-l.

EF: Oh! Yes. We operated diesels too.

DL: Oh, you operated diesels by then?

EF: Oh, yes. We operated diesels too.

DL: I always assumed they were coal-burning.

EF: No. Half of ours were diesel. Of course we started with steam first and then it wasn't long after before we had the diesels operating.

DL: I always just assumed, in ignorance, thinking that the diesels came after World War II was over primarily. (11:13, Part 2)

EF: Oh, no. We had a lot of diesels over there operating. Now, when the first diesels came over I don't recall, when they were first put in operation over there.

DL: [Pause] So once the war was over and your work. You stayed until most of the American troops had been shipped back, I presume, did you not?

EF: No, I did not. It just depended on the length of service you had, [so] it wasn't long after the war was over that I was ordered back home.

DL: Was that because you were National Guard rather than regular Army?

EF: No. You had to have so many months of experience over there, so you were sent home on that basis.

DL: Did you stay with the National Guard after you came home? (12:33, Part 2)

EF: Oh, no.

DL: You got out of it completely at that point?

EF: Well I stayed in the reserve-not the National Guard but the U.S. [Army] Reserve-until 1956.

DL: There was-from not Greensboro but High Point-a wonderful gentleman who was a contemporary of yours, who wound up as Adjutant General of North Carolina during the 50s, by the name of Capus Waynick. Did you know Mr. Waynick?

EF: What's his name?

DL: Capus Waynick.

EF: Yes, I knew Capus Waynick. He was a newspaperman.

DL: Right. But he was adjutant general, head of the National Guard in North Carolina, during the Luther Hodges administration. (13:32, Part 2)

EF: Yes, I remember Capus. He was a Greensboro man. But frankly I didn't remember him being adjutant general.

DL: He was.

EF: Now, Metts was adjutant general when I was in, J. Van B. Metts.

DL: Right. [Pause] Mr. Waynick had a varied career. He was a newspaperman; he was in World War I; he got into politics and was head of the highway commission; was Democratic chairman for North Carolina; and then was ambassador to Nicaragua and Colombia during the Truman administration.

EF: I remember some of that, yes.

DL: He really got around in a variety of things.

EF: Oh, yes. He had a varied experience, didn't he? (14:54, Part 2)

DL: In your railroad career you saw quite a transition from the early days when you were with railroading as a young man, after World War I, up until the time of your retirement in recent years. Any thoughts on that?

EF: Any what?

DL: Any thoughts?

EF: Well that wasn't too much except the Southern Railway was the first major railroad to fully dieselize in the country. We fully dieselized in 1953. We weren't operating a steam locomotive after 1953 and that really paid off. Now we have. Let's see. We bought the Interstate, and we bought two or three other short lines, so we merged with the Norfolk & Western. Now it's the Norfolk Southern. We paid 1.49 points of N&W stock for one share of Southern Railway stock. That was the basis on which we merged. Of course the Norfolk & Western, you know, [unclear 16:38].

DL: Right. One of your major repair and maintenance centers was there at Spencer [Yard]. (16:51, Part 2)

EF: Yes. That was on the eastern line. Of course we had another shop out on the western line but the major shop was at Spencer.

DL: Have you been there since it's become a historic site and they've tried to restore it?

EF: No, I haven't. I'm sorry. I want to go there but they. Of course they can't get the workmen now. Hunt said he would take it over and finance it but they haven't done it.

DL: Well they've done a lot in the last few years but it's such an expensive proposition.

EF: Oh, yes.

DL: Very expensive.

EF: Yes. I've walked many a mile around those shops over there.

DL: They were hoping that the railroad would help finance that and I don't think that worked out. (17:44, Part 2)

EF: No. Now, we have a locomotive at the Smithsonian, Southern Railway, a passenger locomotive. That's a pretty thing, number 1401. We gave it to the Smithsonian. They had to build a railroad track from Southern Railway Yard, where it was stopped, on into the Smithsonian.

DL: To get it there?

EF: Yes, and they had to cut out a wall. They had to enlarge a hole in the wall to get it in there.

DL: [Laughs] Wow. So it was actually driven to the Smithsonian rather than being hauled in on a.

EF: Oh, yes. I swear, that's a pretty locomotive; one of the latest patented locomotives.

DL: Any other experiences that you can think of?

EF: No, I do not.

DL: When I asked you about incidents, I was talking about such things as the V-1 bombing of Antwerp and the story about the sixteen-year-old Russian boy that worked for you. That was the type of thing I meant. (19:15, Part 2)

EF: Right now I can't. I don't remember. [Pause] There was one time in Haltern, Germany there. We had a little old place, a shop-not a shop, a little office on the outside of one of the big buildings. I needed a glass to drink out of, so I got Nicolai up there, and I [20:04 refilled] my canteen cup and did something like this, you know, for some water, a drinking thing. So, next thing I knew, Nicolai left. He came back in. I wasn't in the office at that time. So when I got back I saw sixteen glasses all lined up on the table I had there-just a worn out table-sixteen glasses according to size [Laughter] that he went out and brought. [unclear 20:38] the German army, you know, and just went by and picked them up and brought them home. [Laughter] He had sixteen glasses according to height.

DL: Well now, at the end of the war did he go back to Russia? (20:52, Part 2)

EF: Well, we had to turn them back to Russia. I wanted to bring him over here but couldn't do it. Couldn't get them on a boat to save your life. So, he was very disappointed. I'd told him I was going to take him to the United States when the war was over. They put out an order that they had to report to a certain place there in Munich, Germany, so he had to go, but he didn't want to go. One line. They had a record of some of those, you know, that came over. I think they came over on [unclear 21:32], some of the Germans?

DL: Yes, sir.

EF: And also the Russians. So, those that they didn't want. Those that they wanted to send to a camp, a concentration camp-the Russians?-they'd go down one line and the others that were going back to Russia would go down another line. That's what I was told.

DL: Mentioning Munich, was the railroad station there in Munich destroyed completely? (22:10, Part 2)

EF: Oh, no.

DL: It didn't suffer extensively from the-?

EF: No, except for one. We had one V-2 to hit the. They came in. The passenger station, of course the lobby, you know, is up front, and back there they had glass windows up above, a glass ceiling. So one V-2 hit the I-beam-that I-beam was just about that wide-hit that I-beam and was going over the passenger-where the passenger trains would come in. Boy, [Laughs] it it had hit down a little bit further it would have done a lot of damage, but it just damaged the part of the building from that I-beam up and very little damage down.

DL: That was after the Americans had occupied Munich?

EF: Oh, yes.

DL: Now, I had thought that the bombs.

EF: No, that was Antwerp. (23:20, Part 2)

DL: Oh. You had mentioned Munich and I was thinking the railroad center there at Munich, which was a huge metro train complex, had been pretty much destroyed by the Americans in the bombing of Munich.

EF: No. No, it was not. They cut the heart out of Munich. The bombing of Munich? They cut the heart out of that but on the outside there I don't think there was any damage at all [to the] railroads.

DL: I was in Munich last April; beautiful city now.

EF: I bet it is.

DL: [Pause] You were saying that in World War I you were stationed at Fort Eustis. Was that a transportation center at that time?

EF: Oh, no.

DL: It is in recent years. It's been the Army transportation center.

EF: At Eustis? (24:38, Part 2)

DL: Yes, sir. I was stationed there for about eighteen months back in the 60s and that was the home of the Transportation Corps at that time.

EF: Oh, it was? I didn't know that. Camp Eustis, Virginia.

DL: We always called it Camp [unclear 24:55], Fort Eustis.

EF: That's where I was when World War I ended. Left Fort Caswell and went up there, a hundred and thirty-six men.

DL: [Pause] Well, I believe that's about all the questions I have. (25:36, Part 2)

EF: I didn't give you anything-.

DL: Well, you have.

[Break in recording]

EF: We would hire the German people, say in the roundhouses. When we got into Germany there were Germans waiting in the roundhouse there to go to work, believe it or not.

DL: They just assumed that they were.

EF: Why sure. They assumed that they. Of course we needed them too. We didn't have enough men there, you know, to put all those German locomotives in condition. They were waiting right there in the shop ready to go to work when we got in there.

DL: And the train yards were intact? (26:19, Part 2)

EF: Well no, not all of them. No, the Air Force bombed a lot of [them].

DL: That's what I was thinking.

EF: Yes. But those that were still up and not knocked down, you know. The American forces hired a lot of the Luxembourg men and girls as clerical workers and took them with them, gave them uniforms. Not an American uniform but the Luxembourg uniform that they wore. They traveled along with the Army. Let's see. I believe a secretary was paid twenty-two dollars a month. We hired a lot of workers there in Antwerp for the kitchen, to work in the kitchen and dining room-diamond cutters. Paid them eighteen, nineteen dollars a month.

DL: [Laughs] How did you know you weren't getting Nazis? (27:29, Part 2)

EF: Well, of course you could go to the Burgermeister in Germany. The Burgermeister had a list of them. You'd go to him first and he'd send them to you. We had one lady there in Germany. She looked after the girls. I called her "the Führer" [Laughs] because she'd say, "You want three girls? [unclear 27:54] tell the Führer to send you three girls," or three men, to do this and do that. The next morning she'd have them right there. Then when we left some of them followed us from Haltern into Herne and from Herne into Fürth. Fürth and Munich, you know, you can cross the street from Fürth right into Munich. They're right together.

DL: But you didn't have to worry there prior to the end of the war that you were getting saboteurs or-. (28:36, Part 2)

EF: Oh, no. We didn't have to worry about that. They were first-let's see-a military government, you know. They sent a lot in there, you know, so they were cleared by the military government. I had a secretary there in Munich. She was. She had married a German officer, a major in the intelligence corps, and he was in a POW camp, but the military government cleared her. She could speak English. I mean she could speak five different languages and take shorthand in five different languages. Her name was. What was her name? Olga Kern. I'd call her "Olga from the Volga." [Laughter] She was a good-size one, I'll tell you that. I believe she weighed around a hundred and ninety pounds. (29:52, Part 2)

DL: The stereotype of the big, solid Germany frau?

EF: The what?

DL: The stereotype of the big solid German früulein.

EF: Oh, yes. I'd tell her I was going to someplace there in Germany for the Third Army. She'd get in the car with me to go and [Laughs] if we saw any Germans at an entrance that we were to enter she'd say something and, hell, they'd just spread just like that. [Laughter] We had the whole door to go through. Boy, she used to. She sounded like a Nazi, SS, or something.

DL: [Pause] Well, I believe that-.(31:05)

[Audio ends at 31:06]